|

[Back

to Chapter 1.]

CHAPTER TWO

CO-OPERATION AND

REPUBLICANISM

1850—1853 |

|

Men of all countries are brothers, and

the people of each ought to yield one another mutual aid, according to

their ability, like citizens of the same state.

(Robespierre) |

|

|

THE principles of the first Working

Tailors' Association were founded on a resolution which stated that

'individual selfishness, as embodied in the competitive system, lies at

the root of the evils under which English industry now suffers: the

remedy for the evils of competition lies in the brotherly and Christian

principle of Co-operation — that is, of joint work, with shared or

common profits.[1] At the commencement of the venture

everything went smoothly. Workrooms on the top floor, with offices and a

shop on the lower floors were fitted out, and the building opened for

business with twelve employees on 11 February 1850. Wages for the

workers soon compared favourably with those of other trades, averaging

24s per week. That month, Maurice published the first of a series of

eight Tracts on Christian Socialism which announced the term 'Christian

Socialism' to the public in which he presented, so he thought, his own

clear convictions on the subject. But his aims as interpreted by the

working class were misunderstood. In general, Christian Socialism was

taken to mean a restructuring of labour based on co-operation, joint

ownership and with increased power to the working class. Maurice's

ultimate intention, however, was through using these means, to

Christianise socialism by opposing the unsocial Christians and the

unchristian socialists.[2]

The early success of the Working Tailors' Association quickly prompted

workers in other trades to make application for membership. In the

following month Massey wrote to Leno suggesting that he should, at his

recommendation, move to London to take charge of a Working Printers'

Association, soon to be formed. Leno, following an interview with the

proposers, agreed, but preferred to remain as an operative rather than

be taken on as manager. His printing press was moved from Uxbridge and,

during the three years he was with this Association, Leno found that he

was able to provide them with much valuable service, as well as maintain

his active Chartist interests.[3]

|

|

|

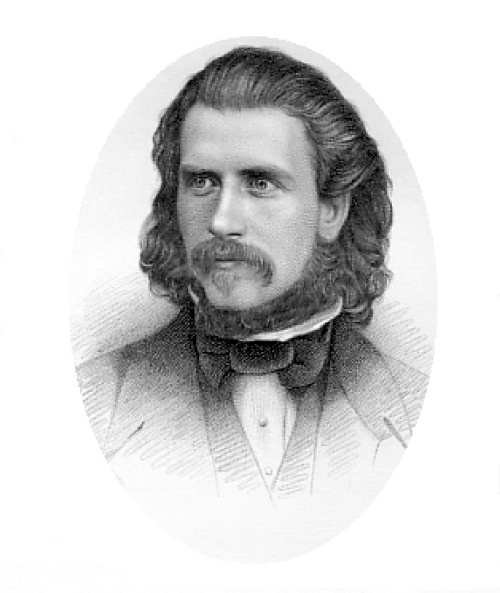

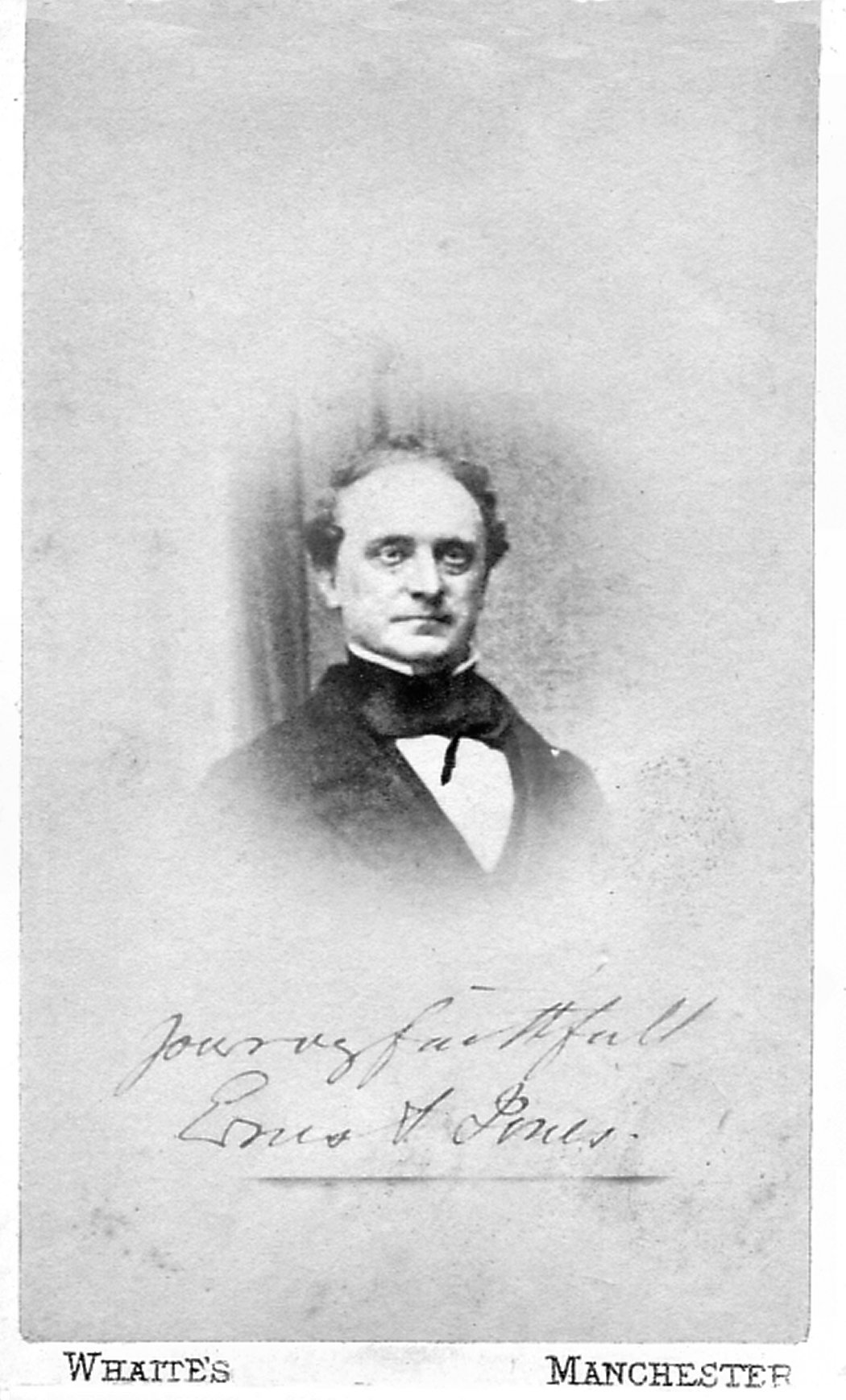

John Bedford Leno 1826—1894. (The

Commonwealth, 6 October 1866)

Leno had supported George Julian Harney and his

Internationalism during the last stage of the Chartist

movement. He then involved himself with the Reform

League, becoming a member of the Executive Council. He

wrote prose and poetry, his published poems with social and

labour themes being highly regarded. Although

emotionally descriptive, he was not subject to over emotive

idealism that featured in many of Gerald Massey's poems.

See for example, his Herne's Oak (1853), Drury

Lane Lyrics (1868) and The Aftermath (1892). |

Despite much general approval for their venture from working class

journals, the Christian Socialists received a sharp attack from the

Daily News. Maurice and the new movement were criticised:

The case of the working tailors ... is ... to some extent, a remedial

one; provided, however, the sufferers do not allow themselves to fall

into the hands of persons who seek to turn their case into an

illustration that humanity and political economy are irreconcilable, and

to erect on their unfortunate workshops of Christian Socialism, as Mr

Maurice, of King's College, in the Strand, is pleased to term his

hostility to the principle of commercial competition, about which he

seems to know as much as it is to be presumed he does of single stitch.

Already there are attempts to connect the working tailors' case with the

teaching of the Communist doctrine . . .[4]

The promoters of the Christian Socialists with their high clerical

connections received visits from many upper class persons of distinction

who were desirous of seeing at first hand the practical work being

achieved by the associations. One day a messenger hastily entered the

Castle Street workshop informing the workers that the Bishop of Oxford

was downstairs, and intended to visit the operatives before he left.[5] This caused a great deal of excitement. Hasty preparations were made and

a guard was placed on the landing to inform the men of his lordship's

arrival. As the bishop started to climb the stairs to the workshops, the

warning was given. Walter Cooper entered the room followed by the

bishop, with Gerald Massey close behind. The workers heralded the

bishop's entrance with a hymn to the tune of 'Old Hundredth', although

the words, which differed considerably, fortunately escaped the Bishop's

notice:

|

Old Grimes, he's dead, the good old man,

We ne'er shall see him more;

He used to wear an old grey coat,

All buttoned down before. |

The Bishop beamed jovially at the earnest workers and said to Walter

Cooper, 'Well, now, Mr Cooper, this is really delightful, to see a

number of men while engaged at their work singing praises to the glory

of God. I am delighted at this spectacle!'[6]

|

|

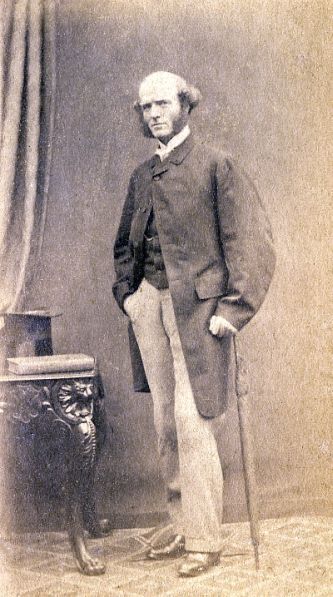

Samuel Wilberforce, Bishop of Oxford. From a

Carte de Visite. |

From the time Massey left Uxbridge he had not ceased writing poetry,

some pieces continuing to be accepted by the Northern Star.

That had come to the attention of Maurice who wrote to Charles Kingsley

in February, 'Has Ludlow told you of our Chartist poet on Castle Street? He is not quite a Locke, but he has I think some real stuff in him. I

hope he will not be spoiled.'[7] It is probably this

remark which suggested to commentators of Alton Locke that Massey was

one of the main prototypes that formed Kingsley's model for this

character.[8] Although similarities have been noted

(see the letter from Massey to Samuel Smiles, Chapter 3), other

proposals for this role were made for Thomas Cooper, the most likely

candidate, or Walter Cooper, both of whom share early experiences

similar to Alton Locke. Although Alton Locke was not published until

August 1850, the book had been completed the previous spring, and there

is no evidence that Massey had made personal acquaintance with Kingsley

prior to commencing at Castle Street.

In the London radical literary sector, Massey and his paper had gained a

favourable reputation. The last issue of The Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom

contained an article by Massey in which he stated his views on the

middle class reformers. He considered that it was time to question the

Chartist leaders as to the direction they were heading, as he doubted

there were more than two of these who knew how they would apply

political reform to aid the poor:

It was the middle class reformers who obtained the Reform Bill, who

then became respectable monopolists and enemies of the unenfranchised. Had there been no Reform Bill, the workers might have had a government

built on Universal Suffrage, and it should be realised that a middle

class despotism is worse than the tyranny of feudalism. Whilst the

middle classes will precede us to power, they will not solve the problem

of labour. Even if we were on political equality, our interests would be

at issue immediately, for while they seek a political change in order

that they may prevent the coming social revolution, we work for a

political revolution, thereby to consummate the social one, which must

follow. If leaders stand in the way, they must be sacrificed at the

shrine of principles.[9]

Editors of more powerful radical papers were taking stock of Massey's

developing literary talent, in particular George Julian Harney of the

Northern Star and the Democratic Review. Harney was an excellent

journalist and a passionate supporter of internationalism. His

Democratic Review welcomed the opinions of, and articles by, foreign

revolutionaries such as Louis Blanc, Giuseppe Mazzini and Ledru Rollin.

Thomas Cooper, imprisoned in Stafford for two years

in 1843 for sedition and conspiracy, during which time he composed his

epic poem The Purgatory of Suicides, had commenced in January 1850 his most noted

contribution to radical journalism. Cooper's Journal: or, Unfettered

Thinker and Plain Speaker for Truth, Freedom, and Progress was published

weekly with a short break, until the following October. As well as being

a focus for Cooper's own series on a critical exegesis of Gospel history

following the Strauss mythical system, the journal included articles by

Thomas Shorter on education and association, and Samuel Kydd, a

prominent Chartist who dealt with industrial matters. In common with

journals of the time, space was given for original working-class poetry. Massey's first poem to be published in London following his arrival,

appeared in the second issue. ‘'Twas Christmas Eve!' contrasted the day

celebrated at a palace with that at a poor man's hovel, and was

characteristic of his socio-political stance:

|

'Twas Christmas Eve! In the palace, where Knavery

Crowns all the treasures the fair world can render;

Where spirits grow rusted in silkenest slavery,

And life is out—panted in golden—garbed splendour ...

Love—kisses sobbed out 'twixt the rollick and rout,

And Hope went forth reaping her long-promised treasure:

What matter, tho' hearts may be breaking without?

Their groans are unheard in the palace of Pleasure! ...

'Twas Christmas Eve; but the poor ones heard

No neighbourly welcome — no kind voice of kin!

They looked at each other, but spoke not a word,

While through cranny and crevice the sleet drifted in.

In a desolate corner, one, hunger-killed, lies!

And a mother's hot tears are the bosom-babe's food! ...

False Priests, dare ye say 'tis the will of your God,

(And veil Jesu's message in dark sophistry),

That these millions of paupers should bow to the sod! … |

Cooper's Journal published fourteen of Massey's social protest

but less overtly martial poems during its run, a notable exception being

the 'Song of the Red Republican':

|

Ay, tyrants, build your bulwarks! forge your fetters!

link your chains!

As brims your guilt-cup fuller, ours of grief runs to the

drains:

Still, as on Christ's brow, crowns of thorns for Freedom's

martyrs twine,

Still batten on live hearts, and madden o'er the hot

blood-wine!

Murder men sleeping; or awake — torture them dumb with pain,

And tear with hands all bloody-red Mind's jewels from the

brain!

Your feet are on us, tyrants: strike, and hush Earth's wail

of sorrow!

Your sword of power, so red today, shall kiss the dust

to-morrow ... [10] |

'The Cry of the Unemployed' demonstrates another typically more socially

directed example:

|

There's honeyed fruit for bee and bird, with bloom laughs

out the tree:

There's food for all God's happy things; but none gives food

to me!

Earth decked with Plenty's garland-crown, smiles on my

aching eye:

The purse-proud, swathed in luxury, disdainful pass me by:

I've eager hands — I've earnest heart — but may not work for

bread:

God of the wretched, hear my prayer! I would that I were

dead! ... [11] |

Massey contributed only one article to Cooper's Journal. ‘Signs of

Progress' exhibited a style that he had developed during this early

period and illustrated so often in his poetry; a proselytising optimism

directed at the working class. At that time there were strong hopes of a

Chartist revival, and the radical papers kept up relentless pressure on

their readers to prepare them for that advent, as Massey demonstrated:

For it is in the dense ignorance which covers the people like a sea

of darkness, that Tyranny lets drop its anchors. Remove this, and its

mainstay is gone; and the King-craft, the Priest-craft, and the

State-craft shall be swept away by the rushing waves of Progress ... It

needs a high heart and never-tiring faith to bear up; but, let not your

hearts die within you, ye who toil on thro' nights of suffering and days

of pain, watering the bread of penury with the tears of misery … For

even as God said, ‘Let there be light'' and there was light; so let the

people say, ‘Let there be Freedom!' and there shall be Freedom. [12]

Prior to and following the 1848 revolutions in Europe, Harney had

supported the Hungarian, French, Italian and German refugees, and had

provided space for their opinions in his Democratic Review. In January

1850, to give further assistance to the cause of foreign democratic and

social progress, he enlarged the scope of his Society of Fraternal

Democrats that he had founded in 1845. The objects of this new

association were for the fraternity of nations, the abolition of stamp

duty on newspapers and the political emancipation of the working classes

through the Charter. The ‘diffusion of political and social knowledge

for the purpose of deliverance from the oppression of irresponsible

Capital and usurping Feudalism', would be promoted by meetings and

continued through Harney's Democratic Review.[13] This produced an immediate response from Massey's idealism, and he

joined with Harney, who was secretary to the association, to serve on

the committee for twelve months.

Soon after the association had been formed, the committee decided to

celebrate the ninety-second anniversary of the birth of Maximilian

Robespierre, the ‘Incorruptible'. A democratic social reformist and

revolutionary leader of the Jacobins in the French National Convention,

he had been guillotined in 1794. A special supper was arranged at the

John Street Institute on the 6 April 1850, to which members and friends

of the Fraternal Democrats were invited to attend. Many organisations

held that pattern of social event that provided the advantage of a large

meal with convivial companionship, during which they solidified their

members by declarations of future intent. Some seventy persons attended

the commemoration with Harney presiding, and many toasts and speeches

were given following the meal. Harney proposed ‘To the Sovereignty of

the People, and the Fraternity of all Nations', responded to by Citizen

G. W. M. Reynolds. Citizen Gerald Massey sang the English version of the

‘Marseillaise Hymn', and Citizens Reed and Massey responded to a speech

by a German exile. Massey concluded this with ‘To persecution and

martyrdom in the glorious cause of freedom'. Other toasts and responses

were made by Chartists Bronterre O'Brien (the health and prosperity of

the chairman, George Julian Harney), J. B. Leno (the memories of Paine

and Washington), and John Arnott, general secretary of the National

Charter Association (Prosperity to the Society of Fraternal Democrats,

and the Democratic Press).[14]

Very early that year in 1850, following his move to London, Massey had

been invited to a demonstration of clairvoyance which, together with

mesmerism and more physical phenomena, were attracting quite wide

interest since the publicity of the Fox sisters in America in 1848. This

young clairvoyant had the apparent ability to read while blindfolded,

and was able also to perceive the cause of some persons' illnesses, the

body appearing to her as translucent during that time. She visited

hospitals and, using her powers, assisted some doctors in their

diagnoses.[15] It was reported that she had

manifested this ability from the age of nine, following a head injury,

and had given demonstrations to the Earl of Carlyle, the Duke of Argyle,

Sir David Brewster and Charles Sumner, then Bishop of Winchester.[16]

|

|

Gerald Massey, Chartist, mid 1850's.

From Samuel Smiles' Brief Biographies, 1876. (Library

of Congress)

A faded carte de visite shows a similar picture, probably

from the same original source. |

|

|

|

Thomas Hughes (1822-96), English lawyer and

author. |

Massey at that time was handsome and eligible. Although short in stature

at five feet four inches, his brown hair worn long and brushed back,

with beard and moustache, a Grecian nose and blue eyes gave him a very

distinguished appearance. This chance acquaintance blossomed into love,

and on the 8 July, 1850, Rosina Jane Knowles, aged nineteen, was married

to Gerald Massey at All Souls' Church, St Marylebone, witnessed

by Walter Cooper and Thomas Hughes. Hughes was a valued member of the

Christian Socialists, and later the author of Tom Brown's Schooldays.

Rosina came originally from Bolton, Lancashire, where her father was a

boot and shoe maker in Independent Street, and the family had moved some

years earlier to 21 New Church Street, Marylebone. Although short-lived,

Rosina transformed the whole of Massey's philosophical conceptions which

he expressed so often in his lyric verse and, less fortunately,

re-orientated his mundane lifestyle for the next fifteen years. There is

no description of her physical appearance, but from indirect references

it may be assumed she was rather taller than her husband, of firm build,

with dark brown hair, brown eyes and a pale complexion.

Immediately following her marriage, Rosina moved in with her husband at

55 Wells Street, off Oxford Street, where he shared lodgings with

Jeremire Jerome, a master tailor and his family. Jerome may have been

employed at the Castle Street workshops, or have been connected with

Thomas Jerome who kept a tailor's shop in Oxford Market, sited at that

time in a small area between Castle Street, Castle Street East, and

Great Titchfield Street.

The 1851 census return for 34 Castle Street

(the headquarters and workshops of the Working Tailors' Association)

shows that Walter Cooper, then aged 38, born in Aberdeen, was residing

there with his wife, Ann, aged 43 years. He is listed as ‘Manager of

Tailors' Association.' They had two sons and three daughters. Also

residing there was Massey's brother, Frederick, listed as a ‘Porter.' It

is likely that he left home to find work in London, and was staying

temporarily at Castle Street prior to finding his later occupation as a

ladies hatter. He married in 1854.

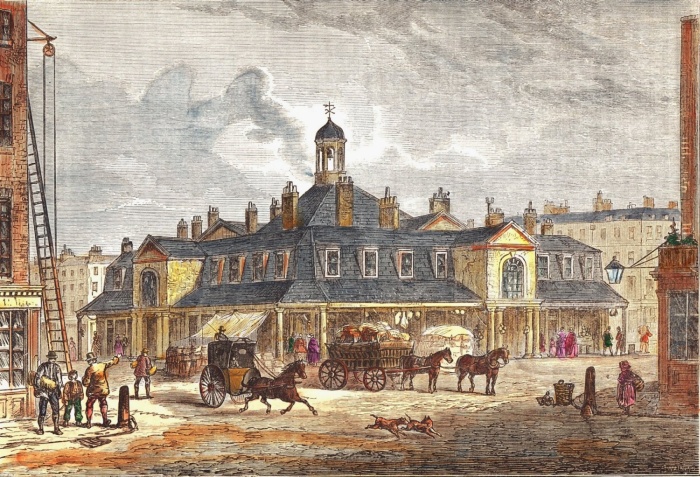

Oxford Market c. 1870.

Marriage did not decrease Massey's political activity, nor his

idealistic enthusiasm for co-operation. Indeed, he became more involved

with the events that were shaping themselves as the last breaths of

active Chartist protest. His first advertised but unreported public

lecture had been delivered on 21 April 1850 at the Institution, Golden

Lane, Barbican, on ‘The Poetry of Freedom and Progress'.[17] At the same time he was forming a closer association with Harney whose

developing socio-political plans most nearly approached his own ideals. Since 1848 there had been increasing ideological disharmony between

Harney and O'Connor. O'Connor was attempting to unite the Chartists with

the middle-class radicals to form a new National Charter League, to

which Harney became increasingly opposed. In order to force a decision,

Harney resigned from the provisional executive of the National Charter

Association and, following elections, won the day. Members of Harney's

Fraternal Democrats now dominated the executive, which decided to

reconstitute the Metropolitan District Council. At a meeting of the

provisional committee on the 19 March, following a speech by Harney,

Massey confirmed Harney's objectives concisely:

The Charter was very good, but we wanted something

with it — our social rights. The capitalists were the great bane and

curse of the nation. In 1848, kings and priests were kicking about, but

the capitalist could buy up both kings and priests. The remedy was

co-operation, Chartism and Socialism united. (Loud cheers.) They had

already established a tailors, a printers, a shoemakers, and a provision

store. (Loud cheers.)

Mr Massey concluded a highly poetical speech which elicited

hearty applause.[18]

Harney had only recently expanded his ideas that would, he hoped,

provide a new impetus in revitalising a flagging interest in active

Chartism. His call for ‘The Charter, and Something More' was first

announced in the Democratic Review in rather vague terms as meaning ‘The

Charter, the Land, and the organisation of Labour', the Land belonging

to all the people which, being the natural right of all, should be made

national property.[19] This call for ‘Something more'

was echoed continuously at subsequent Chartist meetings.

At the French elections of March and April 1850, six Red Republicans had

been returned at the Saône et Loire district with a great majority. To

celebrate their victory, the National Charter Association relinquished

their usual meeting at the John Street Institution in order to hold a

special gathering. To a large assembly Harney, Bronterre O'Brien, Walter

Cooper and others spoke in praise of the democrats of France. Massey

moved the first resolution that appealed to the French people to defend

their natural and constitutional rights by any and every means, and

continued:

The first French revolution had been a glorious work; it broke up the

feudal power of the aristocracy, and it had brought the people upon the

stage, to play, for the first time, an important part in the area of

history; they mounted the platform, and crowns fell down before them

like old Dagon before the ark. (Cheers.) ... There was suffering enough

in this country to make ten revolutions. Might made the right to

liberty, if they would but struggle and contend for it. (Prolonged

cheering.)[20] |

|

|

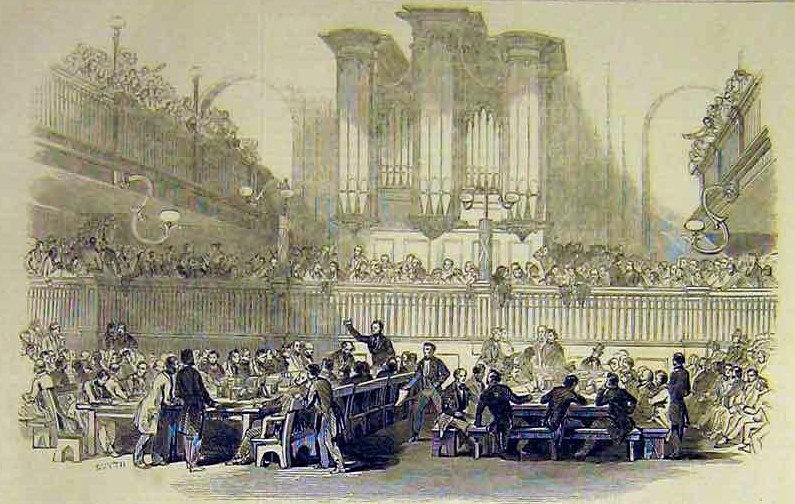

The Literary and Scientific Institution, 23 John

St., Fitzroy Square

(Illustrated London News 15 April 1848). |

|

The release of a number of

Chartists from prison that year was another occasion used

profitably to promote the Chartist cause. A meeting was

immediately convened by the provisional committee of the

National Charter Association, and was held at the John Street

Institution on 23 April 1850. Thirteen of the released Chartists

mounted the platform, and spirited addresses were made by

committee members, including Bronterre O'Brien and Harney. John James Bezer, one of the

late prisoners was introduced, and addressed the packed hall

amid loud cheering. Massey responded to an address by Walter

Cooper, and said in conclusion that:

Ernest Jones, a true poet of labour, had thought that

Englishmen would have been prepared for the revolution, but

misery and degradation had done their work. The people had

fallen a prey to priests, who preached of gods of wrath, and of

hells of torture as though they were the devil's own

salamanders. But the day would come when thrones and

aristocracies would no longer hang as millstones round their

necks. (Loud cheers.)[21]

John Arnott, general

secretary, then moved a resolution that punishment for the

expression of political sentiment was a gross violation of one

of the rights of the people, and that the people should labour

unceasingly for the liberation of their friends and for the

abrogation of those laws which denied the right of free public

discussion. Harney followed by reading a memorial addressed to

Sir George Grey, Queen Victoria's Home Secretary, appealing for

the release of the other Chartists imprisoned for expressing

their political beliefs. It was probably fortunate for the

future release of those Chartists that Queen Victoria's

ministers were unlikely to be reading Harney's Democratic

Review. In the July issue Harney referred to the birth of Prince

Arthur on 1 May, as ‘a royal burden' from which the Queen ‘had

condescendingly allowed herself, in her magnanimous deference to

a natural law, to be relieved.' The prince's christening on the

22 June, for which Prince Albert had composed a 'chorale',

suggested a new five verse rendering to Harney:

|

… O! who would grudge to squander gold

On such a glorious babe as this?

What though our babes are starved and cold,

They

have no claims to earthly bliss.

Ours are no mongrel German breed,

But English born and English bred;

Then let them live and die in need,

While the plump Coburg thing is fed …[22] |

The Christian Socialists at that time did not rely solely on

workshops to promote their ideas. Lectures were given by

members, particularly by Walter Cooper, and public meetings were

held to ensure that their principles became known to the

majority of the working-class. One such meeting was held at the

National Hall, Holborn, under the auspices of the Working Men's

Association, on 31 July 1850, when there was a large attendance

composed mainly of operative tailors.[23] Vansittart Neale, a resolute supporter of co-operation took the

chair and, with Ernest Jones

released from prison on 9 July,

together with Samuel Kydd, Walter Cooper and Gerald Massey as

speakers, it was shown the evils that were resulting from the

competitive system of society, and how these could be remedied

by association. Ernest Jones pointed out that despite increasing

mechanisation over the last eighty years and extending markets,

pauperism, crime and emigration had increased. Poor rates had

risen from one to eight millions and labour was shifting from

the shoulders of male adults to the shoulders of women and

children. This state of things, he said, resulted from the

mechanical power of the country being in the hands of

capitalists, who employed it for their own profit. The effort of

the people should be directed to the formation of

associative-working societies. He moved that competition be one

of the principal causes of the existing distress, and

recommended association to be the best remedy. Massey seconded,

and said that:

If the working classes of England had helped themselves

before, instead of trusting to the legislation of hereditary

imbeciles, they would not now occupy their wretched position.

(Hear, hear.) ... they ought no longer to be content to weave

splendid robes for titled lords and garb their own hearts in the

shrouds of misery. (Hear, hear.)

Walter Cooper called upon the working-classes to assist the

associations by becoming their customers, since co-operation

tended to increase the security and value of capital. As manager

of the Working Tailors' Association, Cooper was particularly

well suited to debate, lecture and write upon the conditions of

working tailors. Poverty stricken in childhood, he had

experienced the slop and sweating systems during his trade as a

tailor. When his first child was born, he had no bed,

bedclothes, food or fire in the room, and was working on a pair

of trousers for which he would receive seven-pence.[24] The condition of the journeyman tailors, male and female, had

received attention also at a meeting of master tailors at the

Freemasons' Tavern on 4 March when extreme cases of poverty and

social degradation were cited. A woman who worked in a slop shop

stated that she received sometimes only 4d for making a

waistcoat; a married man with three children was making a coat

which would take him twenty-six hours to complete and earn him

two shillings. Although he had another coat in hand to make,

this would take him two days, for which he would receive 3s 6d. Yet another worker and his daughter had a room nine feet by

eleven which had also to accommodate two young men and one young

woman, and serve as workroom and bedroom for them all.[25] An up to date statement of the Working Tailors' Association was

provided by Massey for the Leader, in October, when he announced

also that the terms of ‘master' and ‘employed' had been

abolished, and the workman was no longer a hireling. He

applauded the Daily News for working against them, as by doing

so they had helped by advertising their existence, thereby

increasing custom.[26]

On 22 June Harney, finally breaking with O'Connor over policy,

and having completed his notice of resignation from the Northern

Star, commenced his most famous radical unstamped paper, the

Red

Republican. Through this new journal he aimed to provide a

strong political perspective and revive support for Chartism by

elaborating on his earlier ambition to obtain ‘The Charter and

Something More'. Due to falling sales he discontinued his

Democratic Review the following September, but sustained

publicity and aid for the European Democrats in the Red

Republican. The appropriately named title of Harney's new paper,

together with its contents and the fact that it was sold

unstamped, caused misgivings on the part of newsvendors. So much

that at the weekly meeting of the National Charter Association

on 6 August, it was commented that a ‘contemptible conspiracy'

existed among the newsvendors for the purpose of ‘burking' the

Red Republican. Also they opposed it because it was

calculated to bring royalty into contempt (hear, hear, and

laughter.) Bronterre O'Brien informed the meeting that he

was about to visit Manchester in order to agitate the doctrines

of the National Reform League in connection with Chartism.

Playing down the precept that kings and queens were denounced as

being the cause of the people's suffering, he asserted that the

upper and middle classes were the real cause, through their

monopoly of land and profits. (Hear, hear.)

Referring to a recent election at Lambeth where a Chartist was

returned, he pointed out that this person was returned by the

middle class, as he was a financial reformer and upholder of the

rights of capital. What was required was extensive

organisation to endeavour to secure a large number of Chartist

representatives at the next general election. Massey

responded and said that, as he had passed along the streets, he

had heard the drunken song of ‘Britons never will be slaves!'

Why, the working-class of this country were bought and sold

like slaves in the market, and yet seemed inclined to worship

and bow down to those who trampled them underfoot. (Hear, hear.) Britons were the veriest slaves in existence; they were the

slaves of a royalty which spent annually as much as would keep

10,000 families in comfort (hear, hear.); the slaves of a church

which took from them £12,000,000 a year; the slaves of everyone

who had nine-pence to buy them with — and, worse than all, the

slaves of drunkenness . . . I long to see a real and effective

union of all classes of democracy, that the power of those

oppressors might be broken. He was no true friend of the people

who would oppose such a union, when, without it, no successful

effort could be made for the redemption of the people.

After dwelling upon the advantages to be derived from associated

labour, Massey resumed his seat amid the applause of the

gathering.[27]

Massey had been attracted to, and aligned himself increasingly

with, Harney's more fully developed ideas of ‘something more',

i.e. to make the Charter more attractive to the working class by

defining their societal rights as an impetus to political

reform. Harney elaborated on this theme of social regeneration

in a series of articles throughout most issues of the Red

Republican under his well known pen-name ‘L'Ami du Peuple.'

Massey supported Harney and solidified their friendship by

writing poems and articles for Harney throughout the days of the

Red Republican, continuing when it was renamed the Friend of the

People. He also acted initially as secretary to the Red

Republican's committee, and made two stirring contributions to

their first issue on 22 June, 1850; an article 'Cossack or

Republican' and a poem 'The Red Banner':

Let us then fling ourselves into the glorious work; let

Chartists, Communists, and Republicans unite in one common bond

— forget all our idle feuds; and come what may — let us be found

ever in the front rank, ever at the outposts, in fighting the

battles of Freedom ...

|

Fling out the Red Banner! o'er mountain and

valley,

Let earth feel the tread of the Free, once again;

Now, Soldiers of Freedom, for love of God, rally —

Old earth yearns to know that her children are men;

We are served by a million wrongs; burning and

bleeding,

Bold thoughts leap to birth, but the bold deeds must come,

And wherever humanity's yearning and pleading,

One battle for liberty strike ye heart home! ... |

Although the Christian Socialists were actively sympathetic with

the sufferings of the working class, they were far from happy

with the extreme radical activities of some of the Chartist

leaders. Harney, O'Connor and some others were referred to as

'that smoke of the pit', and it was thought that the workmen

were tired of idols, and were just waiting and yearning for the

Church and the Gospel which the Christian Socialists were

willing and able to provide.[28] Kingsley

told the Chartists that instead of pinning their faith on the

Chartist leaders, they should turn to the Bible as the true

Radical Reformer's Guide.[29]

It was understandable therefore, that Gerald Massey, a member of

the Christian Socialists working for the Red Republican, annoyed

Ludlow, who denounced anything of an extreme radical or

irreligious nature. He had regularly to 'blow up' Massey:

for having publicly connected himself with a thing called the

Red Republican, patently treasonable. He was bullied out of it,

by my offering him the choice between association and the ‘Red'

and in the note in which he consented to withdraw, he had told

me that if I for instance had set up an organ of Christian

Socialism he should have been quite willing to write in it.[30]

It was due in part to this episode and the fact that Ludlow

recognised other literary talent among the co-operative workmen

‘either lying idle, or forcing its way through wrong channels',

that induced him to commence the Christian Socialist the

following November, 1850.

Appearing outwardly penitent following Ludlow's reprimand,

Massey was not so easily discouraged and had no intention of

severing his literary relationship with the Red Republican. As

soon as the second issue was published, Massey ran into the

Castle Street workshop with a copy of the paper, which he placed

in front of fellow worker Robert Crowe saying, ‘Crowe, we have a

new poet in the field!' Crowe immediately recognised the style

of Massey in ‘A Call to the People', signed with the name ‘Bandiera'.[31]

Massey had taken this name from the brothers Attilio and Emilio

Bandiera, Italian officers in the Austro-Italian navy who, in

1844 had planned an unsuccessful Italian insurrection. The poem

had been published previously in Cooper's Journal, but Massey

had extended and revised it to a more republican stance. Some

weeks later, with the ninth issue of the Red Republican in his

hand, Massey again informed Crowe that yet another new poetic

star had appeared in the literary firmament, this time in the

name of 'Armand Carrel', introducing himself with ‘A Red

Republican Lyric'.[32] This was a name that

Massey had used originally in the Uxbridge Spirit of Freedom,

for a letter to the ‘editor' headed ‘Struggles for Freedom'. Whether he thought it was too strongly worded to sign with his

own name, or he felt that had already provided sufficient signed

material for that issue is not known:

Peoples of Europe, you have looked on and calmly seen a noble

nation [Hungary] murdered — its blood be upon your heads! Englishmen, you are slaves, blind, plague-stricken slaves! you

see the brave struggling for life and liberty, and will not lend

the helping hand; no, you dare not help yourselves to right and

freedom! all the world know this! they know that the heart of

England hath become the prey of vipers! ...

To end the letter, Massey had quoted some lines from ‘The

Jacobin of Paris', a poem by the Hon. George Sidney Smythe MP in

praise of Jean Paul Marat, a leader in the French Revolution:

|

Ho! St Antoine! ho! St Antoine! thou quarter of

the poor,

Arise! with all thy households, and pour them from

their door —

Rouse thy attics, and thy garrets, — rouse cellar,

cell, and cave,

Rouse over-taxed, and over-worked — the starving and

the slave ...

Justice shall sheathe her sword heart-home; thrones,

crowns

be swept away

And brothers, gallant brothers, We'll be with you on

that day... |

Massey used to recite this dramatically at Chartist meetings

with an effect on the audience which was described as ‘magical',

and it was probably he who suggested that Harney print the poem

in extenso in the fourth issue of the Red Republican, and again

in the twenty-fifth issue of the Friend of the People.[33] The pseudonym ‘Armand Carrel' caused some puzzlement to one

‘Nameless' reader of the Red Republican, who wrote to Harney

asking if an article under that name was really written by the

French patriot. If not, why was a forgery foisted upon the

readers? Although the writer found no fault with the name ‘Bandiera',

he wondered why it was used. Harney had to explain that ‘Armand

Carrel' died fifteen years previously, and that writers with

good reason to withhold their own names selected their

favourites. But he hoped that correspondents would exercise

discretion, having received that week letters signed ‘Marat' and

‘Robespierre'![34]

During that time at the Castle Street Tailors' Association,

steady progress had being maintained until in September Walter

Cooper went on a lecturing tour to the north of England. While

he was away, the accounts of the association were found to be in

some confusion and were examined by the Council of

Administration. Called to return on a suspicion of embezzlement,

Cooper was investigated by the Council of the Society, and was

found to have been careless and too trusting, having had no

previous accounting experience. There was no evidence of

dishonesty. The association was dissolved, and a new association

elected by ballot.

Some eleven of the original workers were not readmitted and

formed themselves into a rival association, The London

Association of Working Tailors. Although that organisation

lasted only until the following summer, it caused a considerable

amount of acrimony while it existed. The affair was not helped

by Ernest Jones, who denounced the entire system of local

co-operation in his Notes to the People in 1851, and entered

into some sharp correspondence with Gerald Massey in 1852.[35] Jones complained of ‘a tissue of virulent abuse or most fulsome

adoration. The abuse is my share, who exposes profit-mongering;

the adulation is for the wealthy gentlemen, who have advanced

money for the Castle-street shop, and enabled it to

profit—monger.' Massey retorted, referring to Jones' ‘strange,

unwarranted, and artificial opposition to the co-operative

Movement', and of his ‘vile, contemptible and infamous

statements'. Although initially supportive of

associative-working societies as a primary step to the relief of

distress at that time, Jones considered that social co-operation

should be applied on a national basis, which could not be

achieved without first having obtained political power through

the Charter. Small individual co-operative associations would

only divert attention from, and weaken efforts towards full

democratic political achievement. That unfortunate episode of

the Working Tailors' Association was related by Massey in a

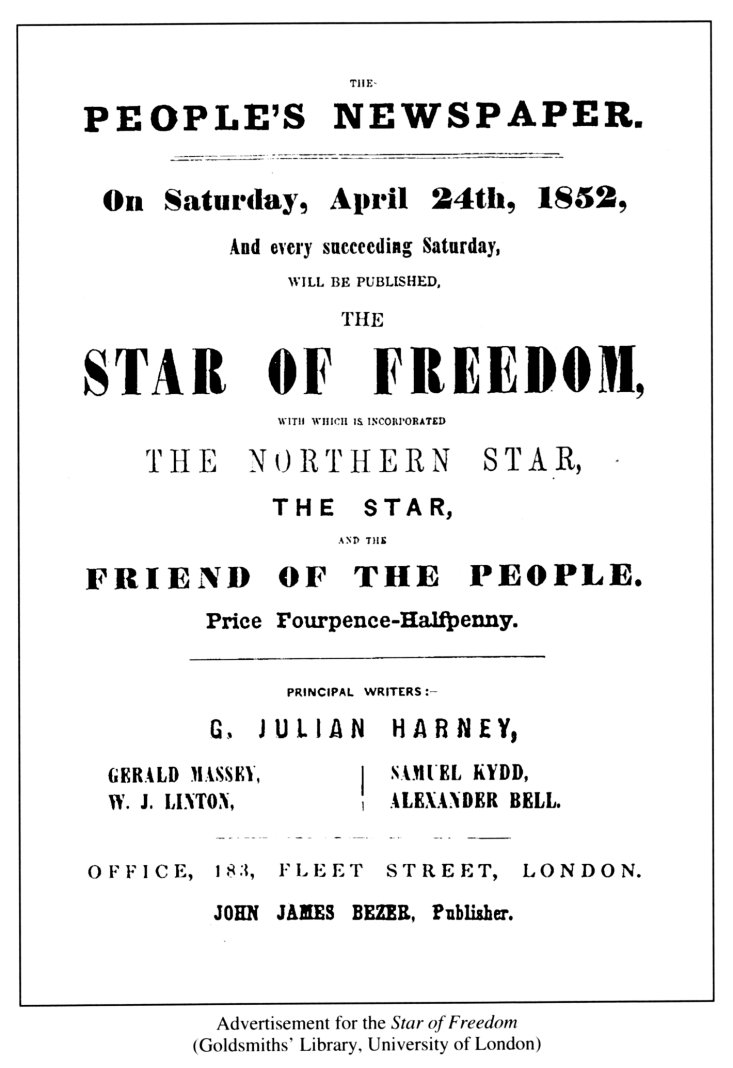

trenchant series of articles for the Star of Freedom, in 1852.[36]

There was, however, one fortunate outcome as a result of that

affair. Had any legal action been attempted against the

association through Walter Cooper as manager, there would have

been even more difficulties, as no Act then in force gave the

association full protection. At the instigation of Ludlow,

Robert Slaney M.P. was persuaded to establish a Commission of

Enquiry to look into the position of liability in the Working

Tailors' and other associative branches. Ludlow, Walter Cooper,

Vansittart Neale and the economist John Stuart Mill were among

those who gave evidence. In June 1852, Slaney's Act was passed

as the Industrial and Provident Societies Act, thereby giving

legal recognition to the co-operative movement.[37]

As a result of Massey's comment to Ludlow, the first issue of

the Christian Socialist appeared on the 2 November 1850, and

Massey's first poetical contribution, in rather fulsome praise

of F.D. Maurice, was published in the second issue as ‘To a

Worker and Sufferer for Humanity':

God bless you, Brave One, in our dearth,

Your life shall leave a trailing glory;

And round the poor Man's homely hearth

We'll proudly tell your suffering story... |

During 1851, J. M. Ludlow had been undertaking a ‘co-operative

tour' through Lancashire and Yorkshire, and in an open letter to

F. J. Furnivall (Christian Socialist II, 49, 4 Oct. 1851) made

reference to the Salford Working Hatter's Association. Furnivall

considered that the current eleven members making some two dozen

hats per week were successful due chiefly to ideas promoted in

the Christian Socialist. Part of their trade was, of course,

competitive. Ludlow however decried the fact that they were mean

enough to charge £10 per cent commission to all other

co-operatives who chose to sell their hats when a small

compensation of £1 per cent might be reasonable. With the

exception of the Manchester Working Tailors who refused to

accept commission, all the co-operative bodies have very quickly

pocketed this enormous bonus in their dealings with the Working

Hatters.

Ludlow then continued with a reference to the Oxford Street

Tailors saying, "Even a certain flourishing establishment near

Oxford Street, — and which shall be nameless, in the hope that

it will mend its manners, and also because its manager, who is

now in the north, professes to know nothing about the matter, —

is stated to have given way to the money-grubbing spirit so far

as to accept it."

Massey quickly responded with a letter in the following issue to

the Christian Socialist:

The Manchester Hatters and the Working Tailors' Association.

Dear Sir, In your last number, Mr. Ludlow assumes that our

Association, among other co-operative bodies, has been selling

the hats of the above Company with enormous profit, — permit me

to explain. The Manchester Hatters sent us specimens of their

admirable workmanship, with the (wholesale prices) attached,

giving 10 per cent discount for ready money. We entered upon no

stipulation — made no conditions of sale, — but simply took the

hats, and exerted ourselves to sell them; and not only did we

not add any profit to the wholesale price, which the

manufacturers assured us would bear 25 per cent — but we gave

each customer the advantage of that 10 per cent discount to the

utmost farthing, and in our own unsophisticated method of doing

business — so far from having nurtured the spirit of

money-grubbing, we have entirely forgotten to charge the

customers for the hat-box, for which, upon referring to the

invoice, I find we are charged at the rate of 3s. per dozen. So

you see our profit has been of the same species as that of two

Yankees, who swapped two jack-knives till each had gained 5s. by

the transaction. In conclusion, allow me to add, that with our

peculiar mode of dealing, I think that the portion of the

community so frequently appealed to as "Smart Young Men who want

a Cheap Hat," cannot do better than apply to us for the same at

34 Castle-street East.

Gerald

Massey, Oct. 2nd. 1851. Secretary.

Two extended articles on Tennyson's poetry ("Tennyson's

Princess" and "Tennyson and his Poetry") completed Massey's

contribution to the second volume of the Christian Socialist,

which ceased publication at the end of 1851 due to high

production costs. Both Massey's articles were over aesthetically

appreciative rather than critical, and he fell into the trap of

the time by quoting large passages of the poems concerned in

order to illustrate facets of his commentary. Nevertheless, he

demonstrated a growing feeling for descriptive romanticism,

often to excess, in marked contrast to his realistic

socio-political verse. In an article ‘Tennyson's Princess', he

embraces the theme of women's rights, inherent in the poem, and

made more self-evident since his marriage:

...We do not want Women to be crammed with dead language and

mummified learning ... but let them be educated up to the

noblest offices and holiest duties of life, which they are not

now . . . the hallowing wretchedness of this inequality is often

a very hell in its torments, — the clasping ring remains, a

mocking symbol!

Despite his plea for the education of women ‘as far as possible

in accordance with her nature', the added proviso that ‘all

attempts to train her into manhood are ... false and unnatural',

deny total emancipation and equate more with the current

Victorian mode of thought and unthinkable rule of society by

matriarchy. Later he was to mellow even his liberal statement

and press for full equality. However, even at that time women's

rights campaigners were pressing those issues. The Woman's

Elevation League, together with individuals such as Mary Howitt,

was actively campaigning for their recognition in social, moral

and professional status. This included pecuniary and political

elevation, together with full franchise.

Within the broader aspects of Chartism, Harney was attempting by

means of a Democratic Conference to unite various democratic

associations into one solid body, into the principles of which

would be incorporated his proposals for greater social reform.

These associates, in addition to the National Charter

Association, would include the Fraternal Democrats, the National

Reform League, and the Social Reform League, and be united under

the title of the ‘National Charter and Social Reform Union'. The

proposition received considerable opposition, and Harney was

forced to concede that Feargus O'Connor, Bronterre O'Brien and

Ernest Jones were against them, and that the Trades'

Associations could not be relied upon for support. On account of

this, it was decided to draw up an address to the people of the

country, and the executive committee resigned for re-elections.[38]

Nominations from localities for the new committee included most

of the old members, represented by Reynolds, Harney, Jones,

O'Connor, Thornton Hunt (editor of the Leader), Holyoake,

O'Brien and Gerald Massey. But just prior to the elections

because of differences over policy, Massey, Walter Cooper,

Thomas Cooper and some others declined to stand. Appropriately,

Massey's articles and poetry in the Red Republican during this

period were appeals for unity, in which he complained that:

We, the democracy of England, are disunited and fragmentary;

we are broken up into sects and parties ... we are even at war

amongst ourselves, and well may the tyrants and oppressors laugh

us to scorn ... they know there is little cause for disquiet so

long as we are disunited. . . We can accomplish little or

nothing, going on as we are—at present. What will the new

organisation of the Chartists effect — singly? ... or any other

body of reformers by themselves? ... Some unity policy must be

adopted, or I am bound to say, that we shall be no nearer the

realisation of our hopes in 1860 than we are in 1850... We are

all democrats! ... Let us then unite Red Republicans,

Communists, Socialists, Chartists, and Reformers. . . It is

unity which is the great want of the time; and if the egotism of

men, calling themselves ‘Leaders' should stand in the way of

this federation, let the party behind each leader push on...

At a Conference of Delegates for effecting a union between

different classes of reformers, at the John Street Institute, in

October, Massey spoke again — as he had cause to, on many

occasions — on the need for greater unity:

‘The Chartist agitation had hitherto proved a failure; it had

never been at so low an ebb as at the present time; even the

Chartists themselves had acknowledged that the bulk of their

body were not Chartists in time of plenty, but sat as easy and

contented as even the middle classes. Seeing this apathy among

their own body, their leaders wished to extend their basis, and

asked other bodies to join them; but they could not expect their

co-operation, unless they admitted the claim of those parties

which the committee had inserted in the programme; he believed

that no party could singly obtain their objects, and that no

programme could satisfy the claims of every party, but they

could agree on some leading principles. He belonged to the

Tailors' Association. They were aware that they would not

struggle successfully with competition without some governmental

change; if they did not agree to adopt the law of Partnership,

or some of their principles, they would lose aid from Christian

Socialism and the young Republican party.'[39]

At a further meeting of the Democratic Conference, it was

realised that its break-up would lead to the Manchester Council

middle-class supporters taking greater hold. Accordingly,

Holyoake with Arnott, Reynolds, Massey and others were appointed

as a Committee of Observation to deal with business and

correspondence regarding possible amalgamation with other

democratic associations.

Nevertheless, despite much effort, it became increasingly

obvious that individual antagonisms together with policy

differences would negate all hope of a universal union. A

Manchester conference held in January 1851 had little positive

outcome, but was notable for O'Connor slandering Harney, which

was refuted at a meeting of the National Charter Association on

the 25 February. At this meeting, Harney was received with a

rapturous welcome and Massey, in an eloquent speech which

excited enthusiastic applause, contrasted the consistency and

manly conduct of Harney with the baseness and villainy of his

slanderers.[40] Despite the negative

conference, a Chartist convention held in London the following

March and April 1852 made more firm agreement on future Chartist

and social agitation. During these activities, there was found

time to organise the annual anniversary social evening in memory

of the birth of Robespierre, held as usual at the John Street

Institution, on 8 April. Harney presided, and a number of

speeches were given by Samuel Kydd, Gerald Massey, Bronterre

O'Brien and others to ‘the sovereignty of the people, the

fraternity of nations, and the social regeneration of society'.

Since joining the Red Republican which Harney had renamed the

Friend of the People in December 1850 to make it sound more

appealing to the working class and acceptable to newsvendors,

Massey had been compiling his published poems with a view to

producing them in book format. Finally completed with some new

material, Voices of Freedom and Lyrics of Love by T. Gerald

Massey, Working Man, was published on the 21 March 1851 priced

one shilling, dedicated to his friend Walter Cooper:

As the toiler-teacher you have won your diploma in the school

of our suffering, and can well appreciate the difficulties which

the self-educated working man has to encounter ... Who can see

the masses ruthlessly robbed of all the fruits of their industry

... and not strive to arouse them to a sense of their

degradation, and urge them to end the bitter bondage and the

murderous martyrdom of Toil? ... But do not think me a mere railer against the classes which oppress our own, I know too

well the evils that are self-inflicted, I know that our greatest

curse is in being our own Tyrants...

Reviews that appeared in the radical press and smaller journals

were distinctly appreciative of his gentler love lyrics and,

surprisingly, more critical of his political poems. The Friend

of the People confirmed the force and fire of his partisan

political poems which were, it considered, lessened by

‘ruggedness', and compared them with the elegance of his love

lyrics.[41] A very valid comment was made

when the reviewer complained of a ‘painful striving for effect

by means of big words and monstrous fantasies. "God", "Christ",

"Hell", etc. are terms used far, far too often'. But these

particular words among others, together with excessive

capitalisation remained an expressive feature of Massey's

poetry. Despite these obvious faults the Pioneer appreciated the

'rich fullness' in the lyrics.[42] The

Northern Star referred to ‘great force of perception,

accompanied by an equal power of delineation . . .' admiring the

‘force, fervour and nervous diction', but preferred also his

Lyrics of Love.[43] Eliza Cooke's Journal

published a biographical sketch and appreciation of Massey

written by Dr Samuel Smiles, the self-help advocate, which has

since formed the basis for most early biographical details.[44]

The Leader, quoting from this sketch and referring to his

martial poems, stated that Vehemence is not Force, while his

lyrics would benefit from the laborious study of versification.[45] Once all the reviews were published, Massey was able to edit

them, and quote the most favourable extracts in an advertisement

printed in the 21st June issue of the Friend of the People.

Both preceding and following the review of Massey's book, Ernest

Jones' journal Notes to the People, which contained Jones' own

poems written while he was in prison, received an equally

honourable mention. It may have been due to these reviews that

at a casual meeting between Jones and Massey in Fleet Street,

Jones grasped Massey's arm, and was reported to have exclaimed,

‘Massey, you and I are the two greatest poets in England!'[46]

Despite Harney having changed the name of his paper it was

steadily losing circulation, and to save it he was trying to

persuade Ernest Jones to join with him in producing a new Friend

of the People. But his advertisements of the proposed format for

the paper were premature; Harney's paper was unstamped, and fear

of prosecution together with greater concern for his own Notes

to the People made Jones decide against the proposition. Harney

therefore was forced to discontinue the Friend of the People at

the end of July 1851. Having now no effective mouthpiece, he was

obliged to rely on accounts of his meetings being reported

principally in O'Connor's Northern Star and Reynolds's Weekly

Newspaper which, despite policy differences particularly in the

former, were by comparison, accurately reported.

Ernest Jones: a

carte de visite.

The Fraternal Democrats and foreign refugees during this period

continued to receive Harney's attention, which culminated in the

arrival in England of the Hungarian leader and patriot Louis

Kossuth on 20 October 1851. Massey wrote a special poem for the

occasion, ‘A Song of Welcome to Kossuth':

|

... Ring out, exult, and clap your hands

Free Men and Women brave—

Shout Britain! shake the startled lands

With ‘Freedom for the Slave!'

Come forth, make merry in the sun

And give him welcome due;

Heroic hearts have crown'd him one

Of Earth's Immortal few! ... |

Published first as a broadsheet, it was seen by the deaf John

Plummer in a Chartist bookshop near the corner of Fleet Street

and Fetter Lane.[47] This would have been

John Bezer's shop, at 183 Fleet Street, the headquarters of The

Society for Promoting Working Men's Associations. Plummer was

living then in Whitechapel, working as an errand boy for his

mother, a needlewoman, and had taught himself the rudiments of

reading by studying the London street names and advertising

placards. It was principally Massey's poem that induced him to

continue with self-education. He eventually became a writer and

earned the praise of John Stuart Mill and Lord Brougham. Later,

he said that he had ‘passed through the same fiery ordeal of

poverty, neglect and suffering ... as Gerald Massey', and that

he deemed ‘the poetry of Gerald Massey to be the most in accord

with the general tone of opinion entertained by the majority of

working men of the present day'.[48]

Massey's first child, Christabel, was born the following day, on

the 22 October 1851 at 50 College Place, Camden Town, where the

family had moved earlier that year. At that time Massey was

obtaining material in order to extend his range of lectures, and

had been writing to Charles Kingsley, asking for some

suggestions. In a letter dated Christmas Day 1851, Kingsley

replied:

My dear Mr. Massey,

Being in your debt three or four moderate letters, I condense

them all into one enormously long one. You must not think,

however, that want of interest in you has kept me silent; not

that, but business, daily & hourly & unwillingness to write to

you at all, without writing carefully & at length. Now this Xmas

night I seem to have time to put on paper the many thoughts

about you, which your letter etc. this morning, re-woke in my

mind; and I begin by wishing you & your wife & child all the

blessings of this most blessed of seasons, for the sake of the

Baby of Bethlehem.

Next, the reviews which I promised you. I have (to my shame) not

yet sent. Nevertheless next week you shall have a parcel

containing 1 or 2 nos. of Frazer, and one no. of the North

British. The Review of Poetry in each of them being mine ...

Also, in the same parcel, the only 2 books about the

commonwealth which I have which can help you, Milton's Prose

works, and Carlyle's letters & speeches of Cromwell ... &

lastly, a sermon which I preached today, which I wish you would

read, as a sample of the way in which to my mind, the great

doctrines of Xtianity have to do with these poor country clods

of mine ... The man to ask about books is Ludlow. I am very ill

read in original authorities of that period. Mr. Maurice also

would give you information ... [49]

The ensuing twelve months were to be virtually the last of any

form of Chartist organisation and Massey's involvement with its

media propaganda came to an end. At a meeting of the National

Charter Association Massey was one of thirty — later reduced to

twenty two — persons proposed to act on the executive committee. The South Lancashire delegate meeting referred to Massey and

some others as those ‘in whom the greatest amount of confidence

can be placed ... '[50] It was decided also

at that time to reconstitute the Metropolitan Delegate Council,

two persons from each locality to be nominated to serve. More

schisms developed within the executive when the Northern Star

was purchased from O'Connor by its editor and printer, and the

tone of the paper became more allied to the middle-class

reformers. Massey, together with Bronterre O'Brien and another

member, then declined to serve on the committee. Additionally,

Harney was away in Scotland, and Ernest Jones resigned when

Holyoake, a supporter of the middle-class reformers was elected. W. J. Linton also declined to serve unless the movement joined

the middle class, believing that it was impossible to

resuscitate the Chartist movement. Furthermore, the association

was in debt, and had to relinquish its offices at 14,

Southampton Street, Strand, and John Arnott, their general

secretary, refused to continue voluntarily, without payment. The

association complained that it, and Chartism, had been abandoned

by Harney and Jones, who had represented that body in public

estimation.

Harney, away in Scotland and aware of the censure he was

receiving, could exert little influence without his own paper. Immediately following his return from Scotland in January, he

started a new Friend of the People on 7 February 1852. Massey

had been waiting for an opportunity of leaving the Tailors'

Association for some time since the Christian Socialist had

changed its name to the Journal of Association, and had ceased

publication in June 1852. Additionally, there was no outlet for

his writing when the first Friend of the People ended in the

following July through lack of support, so he was anxious to

obtain a position which would provide him with greater

opportunity. Since his marriage, Massey had been experimenting

with mesmerism. To supplement his finances he and his wife

started to demonstrate the phenomenon, but initially only on a

private basis. Now that Harney was back in London, Massey wrote

to him, regarding his new venture:

It's now a settled thing that I leave the Tailors'

Association. They intend advertising at once for a Cutter who

will also keep the books. Therefore, I am at liberty to

make further arrangements with you if agreeable, with regard to

the Friend of the People ... do not think I have any

utopian idea of living out of it! ... I can make as much money

in 2 hours by Mesmerism as I get here in a week. What I

have to propose is that I become Conductor and that name,

influence and writing be all directed to extend the circulation

of the Friend with this object in view ... With regard to

remuneration for the present I waive that till you get something

for yourself. My object is if possible to be building

something up for the future ...[51]

Although not referred to as ‘co-conductor', Massey did assist

Harney by writing a considerable number of articles and reviews.

At a meeting of the Chartist Executive Committee on 24 March, it

was obvious that Massey's earlier pleas for unity had been

disregarded. They were forced to admit officially, that it was

‘The Executive of a society almost without members, and without

means — members reduced by unwise antagonism without, and

influence reduced by repeated resignations within …

'[52]

The Northern Star had been equally affected by the Chartist

movement's decline, its weekly sales decreasing to less than two

thousand. The owner therefore decided to put it up for sale. Harney immediately commenced negotiations to purchase it, the

finance being provided by Robert Le Blond, a Chartist supporter

and head of Benetfink, ironmongers of 81 Cheapside. It was first

renamed the Star, then the Star of Freedom from 24 April 1852. That caused Ernest Jones a considerable amount of annoyance, as

he had also wished to acquire it. In an article in the Star of

Freedom Massey commented on reports by Jones regarding the

purchase of the Northern Star:

It has been stated — and the statement has been assiduously

circulated to our prejudice and injury — that this Paper was

purchased by Mr Le Blond, with Middle Class gold, for the

purpose of advocating the Middle Class interest as opposed to

that of the Working Classes. Now, Mr Le Blond has distinctly

denied this in a communication to Mr Ernest Jones (the author of

the said statement), at the same time reminding him, that he has

been the recipient of Middle Class gold! This was forwarded to

him for publication, but Mr Ernest Jones has burked it in

accordance with his usual policy regarding truth …[53]

Massey left the Working Tailors' Association about May 1852,

when the family moved from Camden Town and took up rooms at 56

Upper Charlotte Street, Brunswick Square. There he continued

writing for both Harney's Friend of the People, and the

Star of

Freedom. A preliminary notice by Harney in the Friend of the

People had informed its readers that for the Star of Freedom ‘my

able and enthusiastic friend, Gerald Massey, is engaged as

literary editor, and will, in addition to the Review department,

superintend that portion of the paper devoted to subjects coming

under the general denomination of Social Reform.' Ernest Jones,

determined not to deviate from his principle of priority for the

Charter, and to publicise his programme of reform without

joining the middle class reformers, commenced his new People's

Paper in May. |

|

Massey's prose writing in the later editions of the

Friend of

the People showed continuing development. Articles on John

Milton and Tennyson's poems, reviews of Wordsworth's and Poe's

poems demonstrated, among others, a greater positive critical

appraisal of his subject matter. A portrait of Béranger, in

which he compared unfavourably the poems of Thomas Moore with

those of his subject received a sharp response from Austin

Holyoake, and a corresponding retort from Massey.[54] Writing to Harney at that time, he suggested writing portraits

of Kingsley, Howitt and Carlyle — which was not taken up — and

he complained that ‘ … you don't use what I do send …'[55] In an article on co-operation to which he had become firmly

aligned, he emphasised his stance regarding Chartist policy, and

the solution to social inequities. These views owed no little

affinity to the cause of the Christian Socialists, and the

ultimate higher aim of Ludlow—but lacked the orthodoxy of

organised religion:

[the parsons] have gone on preaching and teaching, announcing

the redeemer not yet come, and the redemption that is scarcely

yet begun ... yet we have little more of true and practical

Christianity welded into our life ... this it appears to me

because they have merely gone on preaching and teaching, praying

and talking, and have not set about any practical realisation of

the redemption they prophesied. They have always sought to

inculcate Christianity instead of so arranging the social

machinery and so moulding humanity, that Christianity should

have been developed as the outcome of a natural growth ... the

advocates of the Charter have pursued the same course of talking

everlastingly, talk, talk, nothing but talk these past twenty

years, save countless martyrdoms and endless sufferings; and

never was Chartism at so low an ebb as at present; never did we

appear farther from obtaining the Charter than now … We have to

reconstitute society on such principles as shall render the

fruit of a man's labour the natural reward for his toil; and

this I maintain, can only be done on the principle of

co-operation …[56]

Harney's support for the democratic refugees continued despite

his being relegated from the National Charter Executive. A

meeting of leading democrats was convened on the 9 May 1852 at

the John Street Institution to discuss the possibility of giving

aid to a large number of the refugees who were living in

squalor, unable to obtain employment. Harney, Thornton Hunt and

Massey were appointed to act as a sub-committee to draw up a

public address to the people. They decided to make a direct

public appeal for funds, and to hold a soirée at the John Street

Institution on 8 June in honour of the Star of Freedom.

Among those present were Louis

Blanc and Colonel Karl Stolzman, and

speeches were given by Harney, Walter Cooper, Louis Blanc and

others, amid general approval. Massey gave an eloquent and

lengthy address which called forth the enthusiastic applause of

the assembly.

The Star of Freedom, meanwhile, was receiving opposition from

some members of the Metropolitan Delegate Council who considered

that Jones' new People's Paper should receive the support of the

council. The dissension continued throughout subsequent council

meetings. At a reorganisation of the John Street locality on 25

May, James Grassby, formerly on the executive committee, and

Massey were elected as representatives to the Metropolitan

Delegate Council. An address was then moved condemning some

despotic members of the executive. The following week's meeting

resulted in a ‘disgraceful uproar', with policies being attacked

and Jones' People's Paper accused of gross misrepresentation. These schisms were partly responsible for Massey ending his

active association with the Chartist movement. But he continued

to write for the Star of Freedom until it ceased publication in

November, due to Ernest Jones' more successful People's Paper. Unsigned items recognised as Massey's include reviews of

Longfellow's Poetical Works, William Whitmore's Firstlings,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Casa Guidi Windows and an article

‘A Visit to the Royal Academy'. This latter show an effect that

is demonstrated in much of his poetry; a colourful chiaroscuro

of aesthetic description, in some parts extremely effusive:

Frith's ‘Pope makes love to Lady Mary Wortley Montague' is a

most masterly composition. The colouring is very white, but it

is of the complexion of the eighteenth century. And what an

antithesis is made out! God and the devil—hell and heaven—were scarcely greater. Pope has had the temerity to declare his

love for that brilliant beautiful woman, and she has burst into

a fit of laughter. And such laughter—rich, ringing,

spontaneous laughter, it swims like glory in her sweetly-drunken

eyes, dimples and bickers on her cheek, flashes from her pearly

teeth, so real and genuine you forget its tragic cruelty, until

you see the writhing victim sit there crushed into ghastly,

livid despondency, bitter mortification, and implacable hatred

of himself, her— everything! …[57]

About August of that year, John James Bezer, active Chartist and

publisher, had been given money by Lord Goderich, the Christian

Socialist supporter, in aid of the Star of Freedom. Harney, not

having received the money, made enquiries via Goderich, who

found that Bezer had fled to Australia in an emigration ship,

leaving his family in England.[58] It was

stated also, by Ludlow, that he had run off with another man's

wife! In further research I have shown that Bezer, an

interesting minor Chartist activist (1816—1888) made a bigamous

marriage in Australia. There he raised a large family and

continued with some literary and political activities.[59] Emigration to Australia had received a sharp impetus following

the discovery of gold in that country in 1851. Massey was

disgusted at this behaviour from a previously valued upholder of

Chartist and co-operative principles, and sent a five verse poem

with his opinions on the subject to Harney for publication in

the Star of Freedom:

|

Another gone back, when our battle went sorest!

Another soul sunk, like a star from the night!

Another hope quencht, when our progress was poorest!

Another barque wreckt, with the haven in sight!

Our Brother once — Traitor now: nay, we'll not curse

him,

O Freedom forgive him, he knew not the cost! ... |

Titled ‘The Deserter from Democracy' it was not published by

Harney, but was included much amended as ‘The Deserter from the

Cause' in Massey's later poetical works.[60]

Probably due to the knowledge that all was not well with the

Star of Freedom and that he could soon become jobless, Massey

decided to increase the scope of his lecture subjects. He

therefore arranged to give a special series of three at the John

Street Institution commencing on 1 October 1852, during which he

would be assisted by his wife. On the occasion that he had first

witnessed Rosina hypnotised, prior to his marriage, he was

indignant at the treatment to which she was subjected in order

to satisfy people's curiosity. They then restricted such

demonstrations to small private gatherings. Unfortunately their

financial state now determined the contrary, so under the broad

heading of ‘Mesmerism and Clairvoyance' Massey advertised the

subject matter to include:

The truth of Phrenology illustrated by Phreno—Mesmerism . . .

Catalepsy induced by means of Mesmeric passes and Readings of

Books, Papers, etc., by means of Inner Vision, the ordinary

visual means being suspended by way of the audience, closing and

holding the eyes of the Clairvoyante with their own hands. The Clairvoyante, Mrs. Gerald Massey, long known as the ‘Somnambule

Jane', has manifested the peculiar power of Clairvoyance or

Second Sight, for a period of eleven years, during which time

she has been satisfactorily tested by numerous persons ...

Admission to the Hall, 3d.; gallery, 4d.; Reserved seats on the

Platform, 6d.[61]

A Star of Freedom reporter recorded that there were good

attendances, the last lecture being very well received as Mrs

Massey was in better health than previously, and the

demonstrations therefore more successful. At the last lecture

her husband:

... attempted to explain the phenomenon of Clairvoyance, and

show how it was produced, which was very startling and

interesting, and to judge from the audience, received with

satisfaction. There were some medical sceptics, well known in

the scientific world, present, who came to doubt and expose the

‘humbug', and it was very interesting to watch their change from

doubt to wonder, from wonder to belief, and as the experiments

went on, to hear them assert their full and perfect conviction

to the audience.[62]

The success of these demonstrations encouraged Massey to give

repeat lectures on 18 October, 25 October and again on 22

November (just to give the sceptics another chance), with an

intervening lecture on ‘Rienzi and Mazzini — an historical

parallel' on the 14 November. He also announced his availability

to deliver a programme of forty-four lectures on tour the

following spring. A wide range of subjects included Cromwell and

the Commonwealth, six lectures on English Literature, six

lectures on living poets, the poetry of Wordsworth and its

influence on the age, Thomas Carlyle and his writings, the song

literature of Hungary and Germany, as well as lectures on

Shakespeare, Chaucer, Tennyson, and American literature. Also on

offer were his lectures on Mesmerism and Clairvoyance. Massey

had been wise in making his plans at that time as, due to

decreasing circulation, Harney was forced to discontinue the

Star of Freedom from 27 November. One month prior to this,

Harney had reasserted his previous declaration, now so obviously