|

Early in March

1918 a highly contagious strain of flu appeared at a

large army camp in Kansas, USA. By the end of the month of the

troops stationed there 1,100 had been hospitalised of which 38 died

after developing bronchial pneumonia, a hallmark of the disease.

As U.S. troops joined the war effort they brought the virus with

them which spread quickly throughout Western Europe and beyond.

However, despite its high contagion this strain of the virus wasn’t

particularly dangerous. Its symptoms generally passed after

several days, and mortality rates were similar to those of seasonal

flu.

It was at this time that the disease was named “Spanish Flu”, a

misnomer that stemmed from wartime censorship. In the

interests of maintaining public morale, the press was initially

prevented from reporting the flu outbreak that was spreading through

the armed forces. Spain, on the other hand, was neutral.

It didn’t impose wartime censorship and so it appeared from Spanish

news reports that the flu epidemic was confined to that country,

hence its name.

During the summer of 1918 cases of Spanish flu diminished leading to

the belief that the virus had run its course — it had not.

Somewhere in Europe a mutated strain of the virus emerged that had

the power to kill a perfectly healthy young man or woman within 24

hours of showing the first signs of infection:

“THE

EPIDEMIC. ― There is genuine alarm on every hand in London at the

remarkable spread of the so-called ‘influenza epidemic.’ One

hears the most extraordinary stories of people suddenly stricken

down — some in the open streets — with this mysterious malady, and

many dying within a few hours of their seizure. Doubtless some

of these stories are exaggerated, but there is no gainsaying the

fact that the disease, whatever it is, is still rampant. It

would appear that there are not enough doctors to cope with the

extraordinary demands which are being made upon them, and in the

peculiar circumstances the Minister of National Service has

certainly done the right thing in issuing an official notice

cancelling all calling-up notices for medical examination of

recruits, thus freeing a large number of medical men for service

among the general public.”

Bucks Herald, 2nd

November 1918

Daily Mirror, 14th

November 1918

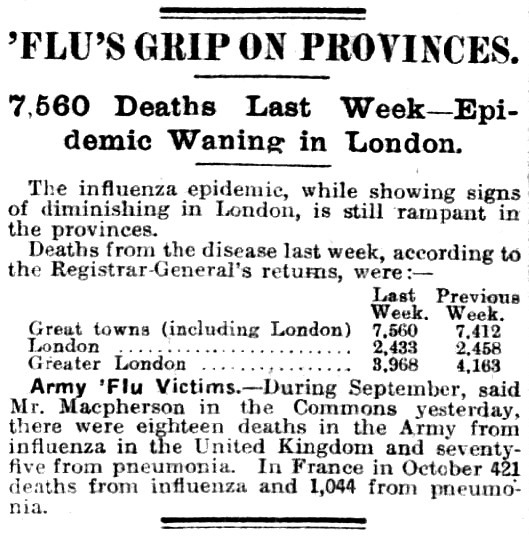

The second wave of the global pandemic had begun. What surprised the

medical authorities was not the high mortality among the very young

and old, but the high mortality rate among those in their prime of life:

AYLESBURY:

HEALTH OF THE DISTRICT.—The Medical Officer’s quarterly report

showed that there had been 53 births and 215 deaths, 104 of which

were non-native, thus reducing the actual mortality for the district

to 111. Deaths from influenza alone numbered 80. Having

observed every epidemic of influenza since 1889, he was much

impressed by the liability of the present influenza to attack

children and young adults. During the quarter there had been

several hundreds of cases, and only one of those was over 50 years

of age; in fact, most of them had been well under 40 years of age.

In the 1889 epidemic old age was the factor which determined life or

death in the broncho-pneumonia complications, but in the recent

epidemic the reverse was the case.

Bucks Herald,

18th January 1919

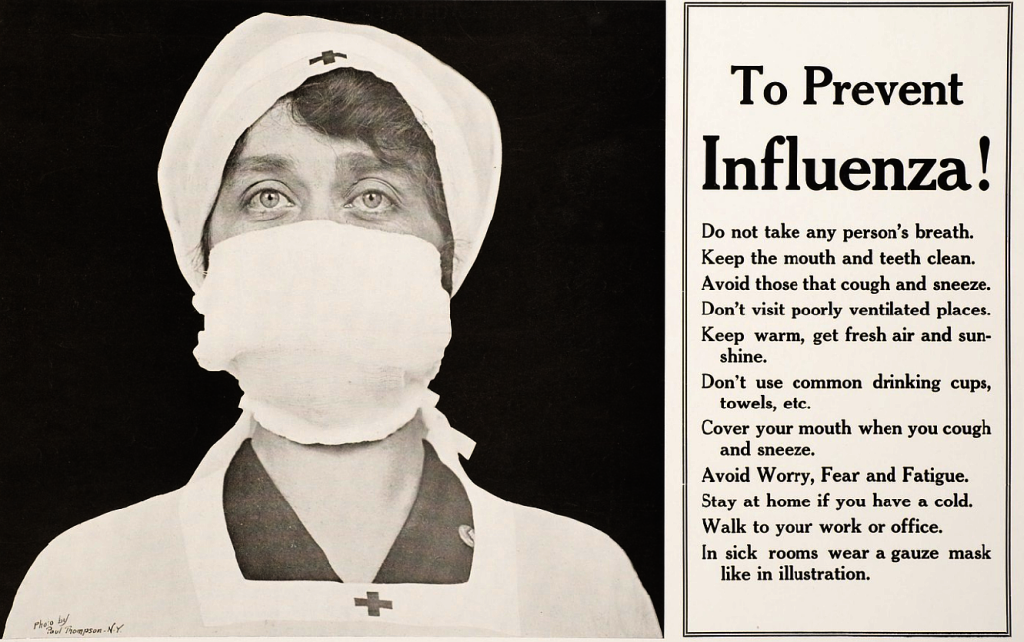

In young, healthy adults, this virulent strain of flu virus triggered an immune

overreaction that led to severe inflammation and a fatal build-up of

fluid in the lungs, causing sufferers to drown in their own body

fluid. This was in an age in which there was no influenza vaccine [1]

nor were antibiotics available to treat pneumonia. [2] The

only treatment available was a combination of fresh air, sunlight,

scrupulous standards of hygiene, and reusable face masks; there is evidence

that this did reduce

deaths among some patients and the spread of infections among

medical staff. There were, of course, plenty of advertisements

for preparations, which, like the “carbolic smoke ball” of an

earlier age, [3]

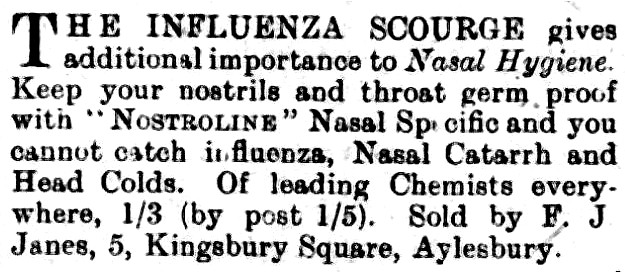

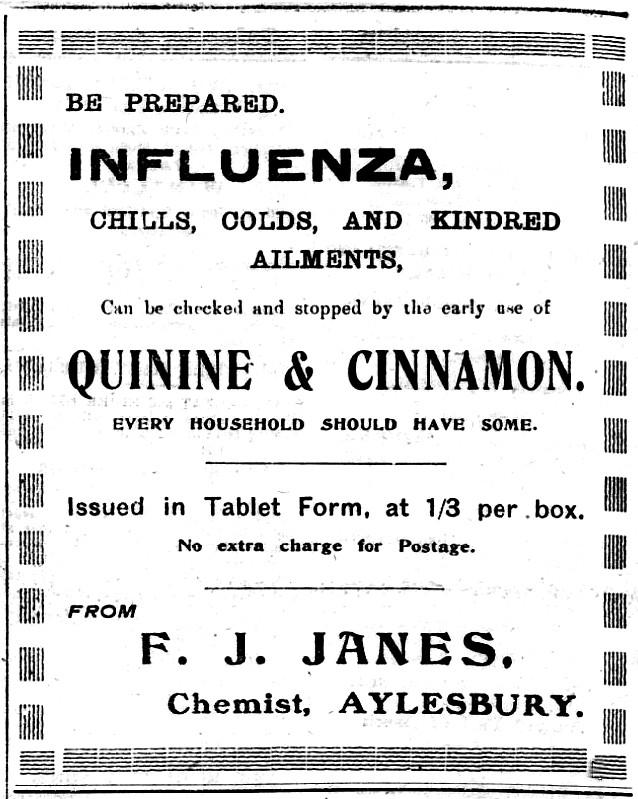

were of highly doubtful efficacy in combating influenza:

Advertisements

from the Bucks Herald,

11th January (above) and 15th February (below), 1919.

By this time censorship could no longer keep the lid on the pot and

news reports began to appear, although compared with the national

press and that covering the Eastern side of the county, Tring’s

paper, the Bucks

Herald, has

surprisingly little to say on the subject. The following

represent some of its reports:

TRING: ROLL OF

HONOUR

It is our

sad duty this week to chronicle the death of the only son of Mr. and

Mrs. Henry Fenner, of Pendley Lodge, who died in Bramshott Hospital

on October 12 from pneumonia following an attack of influenza.

Lawrence Henry Fenner, who was 29 years of age, emigrated to Canada

some ten years ago. Early in 1916 he joined the Saskatchewan

Regiment, and after training proceeded to France, where in the great

battle of Paschendale in November last he was badly gassed. He

was sent home to England, where for a long time he suffered from the

effects of the gas.

Being attached to the Bramshott Depot for orderly room duties, he

there earned the highest esteem of all, both officers and men.

Seized with illness he was taken to hospital, and passed away on

Saturday, his father and mother being with him.

19th October 1918

DEATH OF ALFRED CLARENCE SAUNDERS.

. . . . eldest

son of Mr. and Mrs. A. T. Saunders, of [Tring]

High-street, after a very short illness . . . . Quite early in

October Mr. Saunders had an attack of influenza, and pneumonia

supervening he passed away . . . . Deceased was an architect, and

held an important position in the well-known firm of Robinson and

Roods . . . . having previously trained with Mr. Wm. Huckvale [Architect]

of Tring.

26th October 1918

TRING: INFLUENZA EPIDEMIC.

There are a number of cases in the town, and the medical men are

kept remarkably busy. Fortunately, there have not been many serious

cases, and recovery is generally made with good nursing. A portion

of the elementary schools, which were recently in the occupation of

the military authorities as a hospital, have again been fitted up by

local residents for the purpose of nursing influenza patients. The

schools in the town have been closed during the past week, owing

chiefly to illness amongst the teaching staff.

2nd November 1918

WIGGINTON: THE WAR TOLL.

We regret to have

to record the death of another Wigginton man, Pte. Arthur Kingham (The Buffs), youngest son of Mr. Fred Kingham. Previous to

being called up he worked for Mr. George Rowe, builder, etc. After

training he was drafted to France, and had only been there a short

time when he was attacked by influenza followed by bronchial

pneumonia and died Oct. 19.

2nd November 1918

TRING: PRIVATE JAMES EDWARD AYRES

James Edward Ayres, of Akeman-street, who is well known in the

district, having for many years acted as porter at local auction

sales, and waiter at many public functions, and also newsagent for

Sunday papers, joined the army less than a month ago. On

Wednesday last week his wife was sent for to Woolwich, where Ayres

was in hospital with influenza which was followed by pneumonia, and

soon after her arrival he passed away. The deepest sympathy is

extended to the wife and daughter in their bereavement.

2nd November 1918

WIGGINTON: THE INFLUENZA.

There are so many cases of the prevailing epidemic in the village

that the Day and Sunday Schools have been closed by the medical

authorities. It was the cause of death on Thursday, Oct. 31, of Mr.

W. Gurney. He leaves a widow and ten children, five of whom are

under fourteen. Much sympathy is felt for the family.

9th November 1918

CHESHAM: INFLUENZA.

The number of deaths of young people from influenza in this locality

is alarming, and week by week there is a heavy obituary list. It is

noticeable that many of the deceased were particularly strong young

people.

7th December 1918

TRING:

PRIVATE ARTHUR FRANK WELLS.

Frank Wells of Albert Street, was carried off after an

attack of influenza somewhat suddenly at a hospital in France . . .

. He was 41 years of age, and before joining the Army Ordnance Corps

some three years ago was a tailor in business for himself. He leaves

a widow and three children . . . . he was buried in Blargies

Cemetery on the day following his decease.

1st March 1919

FARR:

IN MEMORIAM.

In ever-loving memory of my dear little DAVID, who died of

chronic bronchial pneumonia, following influenza and measles, on

July 10th, 1919, aged 2 years and 8 months.

In my thoughts day and night,

darling, as long as life lasts.

C.F.

10th July 1919

TRING: EX-OFFICER’S

SAD DEATH

Mr. Albert T. Grace, who

after a long and painful illness contracted on active service,

passed away at Kennington Hospital for Officers . . . . He took part

in the heavy fighting of the opening phases of the German offensive

in 1918 around Kemmel and Ypres . . . . With his health undermined

by his service in the East . . . . he was invalided to England . . .

. He appeared to be making good progress and hopes were entertained

for his recovery, but influenza and pneumonia supervened, and his

death resulted before any of his relatives could be summoned.

31st January 1920

In the early 1970s, British historian Richard Collier placed adverts

in newspapers around the world asking for memories of the 1918

Spanish influenza pandemic. He received over 1,700 replies, which he used

to provide material for his book The Plague of the Spanish Lady (Macmillan, 1974). Elsie

Phillips Cole writing from Tring had this to say of her experience:

“My husband was in France ... I had 3 children under 4 years, boys.

I remember one night in particular, I slept between the cots of my

two eldest and we all had high temperatures from flu – but I was

nursing my baby just the same – there was no time to wean him. The

boys were restless and tossed and muttered – but the baby slept on,

unusually, till I was dressed and when I took him from his cot he was

practically unconscious and limp.

“I had read in The Daily Mail that the French treated the flu

successfully by taking nothing but brandy for 3 days. By the

grace of God I had about 1oz. of brandy left and I began to wet the baby’s

lips with it and got a little down him till he became fully

conscious. I looked out of the window for help and saw the empty car

of the one doctor left in Tring. I raced downstairs and got in the car

till he came out of his client’s house and got him to see my baby

and in no time he had the very efficient District Nurse in to help

me. My daily help had not been able to come, as her brother was on

leave from France and he was down with the flu and my sister and

parents, who lived near also and their staff had it.

“There were

isolated Cottages where all the inhabitants lay dead and unattended

(3 to be exact close to Tring) and the National School was turned

into a Hospital, but with 3 trained Nurses in charge. But the 3

nurses caught it, 1 died and 2 ended up in a mental home. My aunt

volunteered but gave up when she had it.”

A third and dangerous wave of Spanish Flu emerged in 1919, and with infection being

spread by troops returning home the mortality rate was as high as

in the second wave.

The end of the war eventually removed the crowded

munitions factories and the cramped and insanitary living conditions

of the troops that had combined to allow the disease to spread so far and so

quickly. It is now believed that no other pandemic in history

killed so many in such a short time as Spanish Flu. [4]

In view of its high mortality, sad to say there is no public memorial in the UK to the victims of the Spanish

Flu pandemic and to the medics and others that strove to help them, but this reflects international practice with

New Zealand

providing one exception.

By 1920 the Spanish Flu virus had become much less deadly with its

effect eventually diminishing to that of ordinary seasonal flu.

Ian Petticrew

January 2022

――――♦――――

Footnotes

1. Viruses were demonstrated to be particles, rather than a fluid,

by Wendell Meredith Stanley, and the invention of the electron

microscope in 1931 first allowed their complex structures to be

studied. During the Second World War the US military developed

the first approved inactivated influenza vaccines (these vaccine

used fertilised chicken eggs, a method that is still used to produce

most flu vaccines). At the same time mechanical ventilators

became available, which allowed the breathing of patients suffering

respiratory complications to be supported.

2. M&B 693 was one of the early generation of sulphonamide

antibiotics (aka sulpha drugs). Originally produced by the British

firm May & Baker Ltd in 1938, it was the first chemical cure for

pneumonia. Penicillin did not become available for civilian use in

the UK until 1946.

3. The Carbolic Smoke Ball Company made a product called the

“smoke

ball”

filled with carbolic acid, which, it claimed, was a cure for

influenza and a number of other diseases. This bogus claim

resulted in the leading case in English contract law of

Carlill v

the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company (1893, 1 QB 256 Court of Appeal).

4. It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third

of the world’s population became infected with this virus. The

number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide

with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.

Centre for

Disease Control and Prevention |