|

The Great Berkhamstead Gas Light and Coke Company

by

Tony Statham,

reproduced by kind permission of the author.

We are all familiar with the phrase “fossil fuels” applied to oil,

gas and coal and know that most of our utility needs are met from

these commodities. Recent price rises in all these items have

been very much in the news over the past year and even with the

subsequent fall in the oil price, remain a topic of everyday

conversation. Most of us probably take fossil fuels for

granted and I am sure few people consider the origins of their

electricity when they flick a switch to power up a computer,

electric kettle or all their other domestic appliances. Gas is

perhaps a little more “hands on” as the user has to ignite the

material unless it is used in a heating boiler where this is

typically done automatically. However, most gas customers

again assume that the pipe laid to their house or premises somehow

arrives by magic without too much concern for its origin.

While coal, per se, has been known as a fuel for thousands of years,

as early as the 17th

century, scientists were discovering that a “wild spirit” escaped

from wood or coal if these were heated. The Flemish scientist,

Jan Baptista van Helmont (1577-1644) thought this substance

“differed little from the chaos of the ancients” and named it gas in

his Origins of Medicine (c. 1609). Several others

experimented with the “Spirit of the Coal” and in England, William

Murdoch (later Murdock) (1754-1839) and a partner of James Watt, is

reputed to have heated coal in his mother’s teapot to produce gas.

He developed new ways of making, purifying and storing gas and by

1792 had installed gas lighting in his house at Redruth.

Further installations followed in various premises and other

demonstrations and installations were established in France and the

United States. It is however generally recognised that the

first commercial gas works was that built by the London and

Westminster Gas Light and Coke Company in Great Peter Street in 1812

laying wooden pipes to illuminate Westminster Bridge the following

year. The all too familiar practice of digging up streets to

lay gas piping required legislation and to some extent this hindered

the development of street lighting and gas for domestic use.

Nevertheless, by the 1850s every small to medium sized town and city

had a gas plant to provide for street lighting. In the 1860s

(and the remainder of the 19th century) several other advances were

made in the production and use of gas. Perhaps one of the most

important was the introduction of the gas mantle, a somewhat fragile

impregnated mesh, which allowed the gaslight to burn with a much

brighter and more even flame. An ordinary gas flame is similar

in illumination to a single candle whereas the application of a

mantle produces something akin to a 100-watt electric light bulb.

This development naturally had a dramatic effect on industry and

domestic life enabling night-shift work to expand, encourage more

people to read and write and render public streets and spaces safer

after dark. Towards the end of 19th century, the invention of

the gas meter played an important role in selling “town gas” to

domestic and commercial customers for lighting and subsequently

heating and cooking appliances.

The Great Berkhamstead Gas Light and Coke Company built the first

gas works in Berkhamsted in 1849 at the lower end of The Wilderness,

effectively where the Water Lane car park extends behind Tesco; the

manager of the works lived in Adelbert House, which remains today on

the corner of Mill Street. At this time the Parish Vestry

oversaw the development of public health, relief for the poor and

other services in the town. However, the funds to build the

gas works were raised by public subscription and the company started

with a capital of £2000 comprising 400 shares of £5 each. This

was sufficient to establish the works (£1800), the initial service

pipes (£3-13-1ld) and install street lighting. The Vestry

consequently only had to pay for the gas itself and any maintenance

came from the rates.

The first Trustees of the company were R. A. Smith Dorrien (of

Haresfoot) and Mr T. P. Halsey MP (of Berkhamsted Hall). The

first chairman was the Hon. Col. J. Finch (of Berkhamsted Place) and

the directors included J. E. Lane of Lane’s Nurseries. The

first year of operations yielded an income of £242-12-2d from the

sale of gas while by-products such as coke and tar yielded

£35-19-10d. The company’s records show that the cost of coal

in the first year was £67-0-6d and that a surplus in excess of £150

allowed a dividend of 5% to be paid. It is recorded with a

note of disappointment that the Town Inspectors failed to pay their

first gas bill (£74-5-0d) for public lighting. However the

directors were sufficiently optimistic to reduce the price of gas

after the first year from 8/4d to 7/6d per 1000 cu. ft. This

level of generosity proved so popular in increasing the customer

base that the price ultimately fell to just 4/9d per 1000 cu. ft. by

1882. Ultimately, the persistent increase in coal prices put a

stop to this practice and the company records suggest that the gas

price stabilised at around 5/- per 1000 cu. ft.

The generation of “coal gas” as it was sometimes known, naturally

depended on a regular supply of coal and at the inception of the

works, this fuel was brought by canal boat although the railway had

reached Berkhamsted by 1837. However it was not long before

rail freight became a more viable alternative and soon coal was

being delivered by rail with the return wagons taking tar and other

by-products from the gasworks, back to London.

The annual reports and minutes of company meetings from 1849 to

1905, which are held in the Museum Store, provide detailed accounts

of the various maintenance and expansion works that were deemed

appropriate as the supply of gas extended to the boundaries of the

town. The original three iron retorts were expanded to five in

1852 and then replaced by brick ovens in 1855. This year also

witnessed the cancellation of supply contracts to the town

inspectors and the station in favour of meters being installed.

This apparently allowed the town to reduce street lighting by some

25%. In 1856, additional land was purchased for a second

gasholder and in 1857 the height of the chimney to the “furnace” was

raised “to carry off the vapour from the purifiers and thereby

remove a nuisance which was threatening the very existence of the

works”. A new six-inch main was laid to the High Street in

1858 (replacing a three-inch one) and new pipes were laid to Manor

Street and Ravens Lane. By 1860, over one million cubic feet

of gas were being generated and in 1861, Thomas Curtis took over the

chairmanship of the company.

Throughout this period the financial profile of the company grew

substantially, new shares were issued, profits were raised and the

dividends were increased. The new capital and higher levels of

income allowed continued expansion of the works and the network of

service pipes, and in 1868 a second site in Water Lane was acquired

to erect another gasholder. In 1873 it was decided to change

the company’s bankers who had been Messrs Butcher and Co. in Tring

to the more convenient London and County Bank in Berkhamsted High

Street.

In 1886 additional land between the works and the River Bulbourne

(owned by Earl Brownlow) was earmarked for future expansion. However

in 1892 the Sanitary Authority had instituted proceedings for an

“alleged nuisance” from the works and by 1903 the governors of the

neighbouring Grammar School expressed a strong desire for the

removal of the works altogether. This is perhaps not so surprising

given the relatively anti-social environment of a gas producing

plant in the centre of a market town. Apart from the disadvantages

of coal-dust and the manufacturing plant itself, various waste

products inevitably would have contaminated the site. To be fair,

the area around the Wilderness at the end of 19th century was not

especially salubrious but the gasworks would certainly have been an

added blight on the town centre. Lord Brownlow again provided a

solution by offering a totally new site off Billet Lane.

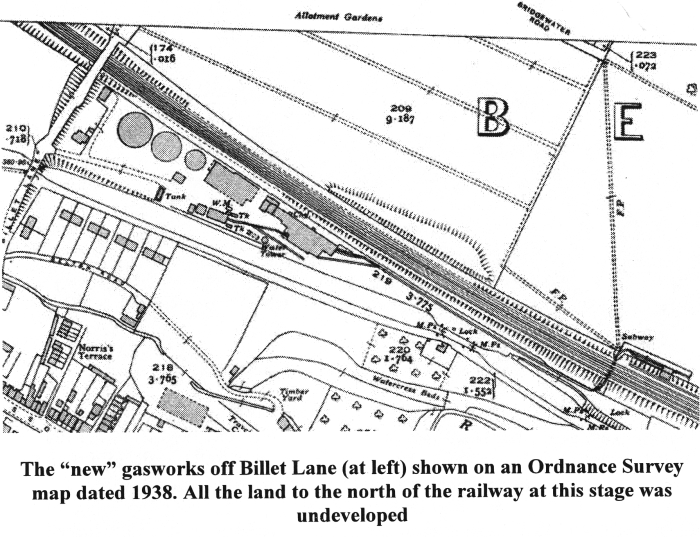

The new site lay between the canal and the railway and is now the

River Park Industrial Estate (see map). This offered the advantage

of being able to deliver coal by either canal barge (the adjacent

canal lock, no. 51, still boasts a sign “Gas 1”) or by railway

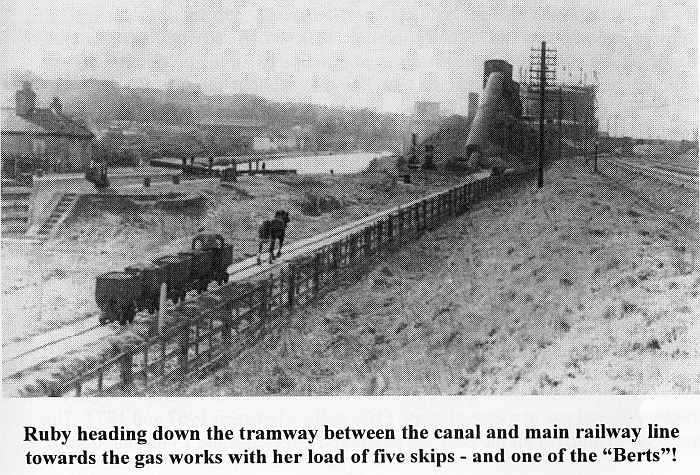

wagon. However, as it was presumably impractical to off-load coal

directly at the gasworks, a dedicated feeder line (a horse-drawn

tramway) was built

at the end of the railway goods yard, to the west of today’s station

car park. As this lay to the north of the main railway line (at that

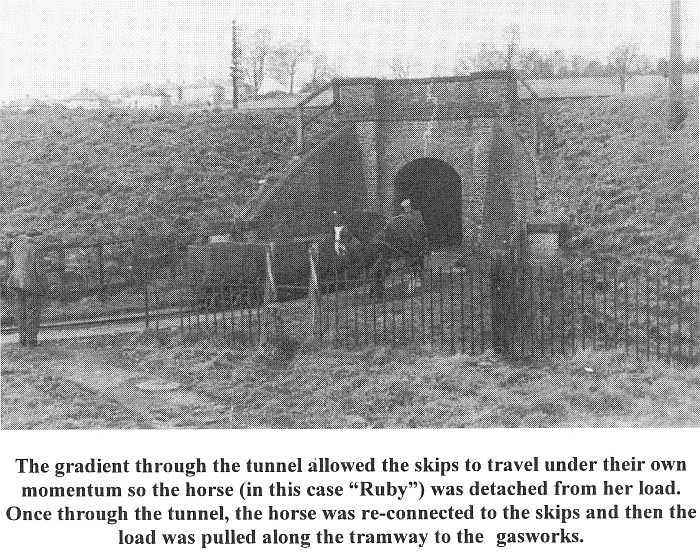

stage The London Midland and Scottish Railway), the tramway utilised

an existing pedestrian subway tunnel to reach the gasworks on the

south side, a total distance of approximately 400 yards. The tunnel

still exists today but is sealed with a metal gate.

Coal was unloaded from the main railway wagons into a small bunker

and thence into the skips on the tramway, which had a gauge of 18½ inches. According to

Contact magazine (date unknown, but probably early 1950s),

the German engineering firm Krupps of Essen

made the tramway rails. The skips apparently held about six

hundredweight of coal (approximately 305 kilos) and in the earlier

years, a load consisted of four skips.

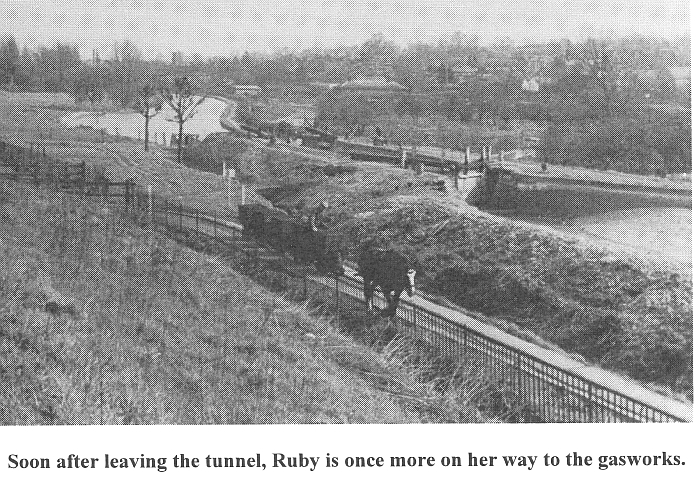

A letter written to H. C. Casserley by the Eastern Gas Board in 1955

confirmed “Horse traction has always been employed. ‘Kitty’

a fine

mare, did the job for many years, then came Billy and following him

our present mare ‘Ruby’. While in 1906 ‘Kitty’ handled a maximum

coal requirement of 10 tons, ‘Ruby’ now deals with a maximum of 50

tons”. Apparently this was a daily figure and Ruby was

able to pull five

skips, thus about 1½ tons per journey. H. C. Casserley’s article in

the Railway Bylines magazine of April 2005 stated that by “the 1930s

more than 5000 tons of coal was conveyed by the tramway each year”.

The Contact magazine article also identifies the two staff operating

the tramway at that time who were nicknamed “Old Bert” and “Young

Bert”. Old Bert in reality was Herbert Alfred Hartup, originally a

cowhand who became a stoker. Married with five children, his name

persisted in one son following his footsteps by helping out at the

Watford gasworks. Young Bert was Bertram Hannel and was not related

to Old Bert.

Ultimately “horse traction” was overtaken by mechanised transport.

The gasworks ceased production in 1955 and was finally closed in

August 1959. The two gasholders (or gasometers) continued to be used

for storage for some years and the tramway tracks were mostly

removed in the 1970s; a short section still lies in the subway

tunnel.

So, what happened next? To start with, coal gas continued to

be supplied to Berkhamsted but from the gasworks at Boxmoor where

the gasholders still persist. The composition of gas varies

according to the type of coal used and the temperature at which the

heating process or carbonisation takes place. A typical

breakdown might be: Hydrogen 50%, Methane 35%, Carbon Monoxide 10%

and Ethylene 5%; only the latter produces a luminous flame but as explained above, this can

be greatly enhanced with the use of a mantle. Depending on the

quality of coal used, the process of making gas generated

by-products such as coke, coal tar, ammonia and sulphur all of which

had their own end-uses. Coke provides a smokeless fuel but can also

be used to generate other types of gas and in metallurgical

manufacturing where a higher temperature is required. Coal tar can

be distilled to produce tar for road surfaces, benzene (a solvent or

motor fuel), creosote (wood preservative) and phenol/carbolic acid

(used in the manufacture of plastics and disinfectants); sulphur is

used principally for the production of sulphuric acid and ammonia is

the foundation for various fertilisers.

The Gas and Coal Act of 1948 created a nationalised industry

throughout the UK and in the 1960s, natural gas was discovered under

the bed of the North Sea and a new national distribution network of

some 3000 miles was established. Apart from being a readily

available supply of indigenous energy, natural gas has the

advantages of being non-toxic and requires little processing. Town

gas contained

extremely poisonous carbon monoxide and both accidental poisoning

and suicide by gas were commonplace. Poisoning from natural gas is

possible if incomplete combustion occurs and carbon dioxide

accidentally leaks into living accommodation. Both town and natural

gas are odourless and thus a foul-smelling substance (mercaptan) is

added to allow detection if gas leaks occur.

All gas equipment in the whole of the UK was converted to burn

natural gas instead of town or coal gas at a cost of some £100

million between 1967 and 1977. This included writing off all the

coal gas plants and affected some 13 million domestic customers,

400, 000 commercial users and 60,000 industrial customers. The town

gas industry died in 1987 when the last plant was closed in Northern

Ireland. It is interesting to speculate that with natural gas now

being a world commodity and subject to the vagaries of international

trade, supplies may be subject to disruption or even disconnection. The possibility of supplies also being depleted might suggest the

possibility of a return to the manufacture of coal gas in the future

especially where substantial reserves of coal remain available.

――――♦――――

References:

The minutes and accounts for The Great Berkhamsted Gas Light and

Coke company 1849 to 1905 — held for the Berkhamsted Local History

and Museum Society in the Dacorum Heritage Museum Store

Wikipedia

Encyclopaedia Britannica - DVD2000

A Short History of Berkhamsted — P. C. Birtchnell

Contact magazine

Railway Bylines magazine (April 2005) H. C. Casserley

Photographs — R. M. Casserley and H. C. Casserley

Britishgasacademy.co.uk

The London Encyclopaedia — edited by Ben Weinreb and Christopher

Hibbert (1983 revised 1992)

――――♦――――

First published by the Berkhamsted Local History and Museum

Society in

The Chronicle Vol.VI. March 2009

――――♦―――― |