|

ROADS, AND THOSE IN TRING.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ENGLISH ROADS:

THE TWENTIETH CENTURY.

There were only 8,000 cars in the whole of Britain at the start of

the 20th century.

By the end of the century, the car population had soared to 21 million.

MOTOR TRAFFIC AND ROAD IMPROVEMENT

The motor vehicle: road dust and safety issues

The first decade of the new century was marked by a growing number of

motor vehicles. They were being driven on macadamised highways,

the gravelly surfaces of which were formed from imperfectly consolidated

broken stone. While ideal for horses’ hooves, which could find a

firm foothold in both dry and wet conditions, this form of unsealed surface

caused faster moving motor vehicles to throw up clouds of dust in dry

weather, while in wet weather, horse dropping mixed with urine and rain formed

mud, which was scattered by motor traffic. Towns usually opted for

roads surfaced with stone sets or cobbles. These were hard wearing

and did not pose the dust problem, but they were slippery in wet

weather, a problem made worse by the liberal deposits of horse manure

and urine piled upon them. Horses often came to grief, and

steam and motor powered vehicles could all too easily slide off the side

of the road.

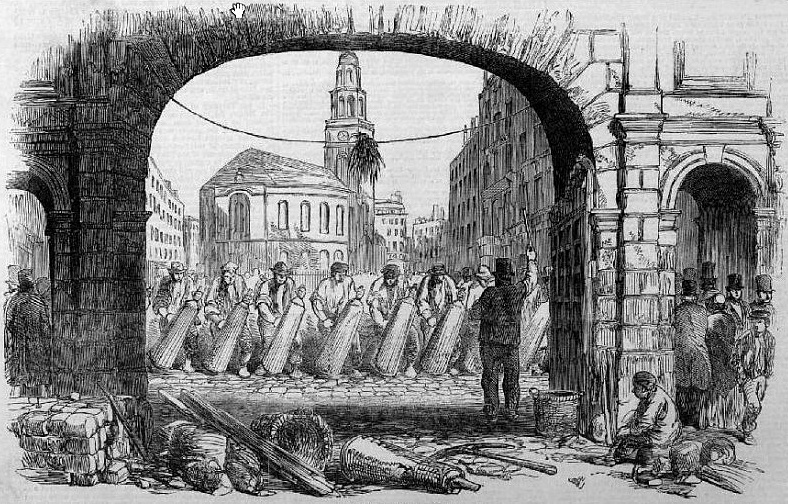

Compacting stone sets ― note the foreman

beating time.

Illustrated London News, 1851.

In an age that had yet to come to terms with the internal combustion

engine, other road safety issues arose, not least among which were

accidents resulting from the higher speeds now being attained, and the

noise from this new form of traffic causing horses — still the

predominant form of traction — to panic.

The solution to the problems of dust and mud was solved in 1902 by Edgar

Hooley, County Surveyor for Nottinghamshire. Hooley patented an

all-weather road surfacing material made from mixing tar with ironstone

slag, which he called ‘tarmac’. When laid, tarmac acted as a

sealant, suppressing both dust and loose matter, but a considerable

number of years were to elapse before most roads had been ‘tarmacadamised’.

To some extent road safety issues were addressed by the 1903 Motor

Car Act. [1] This introduced the crime of

reckless driving and imposed penalties. Road vehicles were to be

registered and licensed, with number plates showing their registration

numbers, and a national speed limit of 20 mph was imposed with local

limits imposed by county councils as necessary. Vehicle drivers

had also to be licensed, the minimum qualifying age being 17 years, but

a compulsory driving test was not introduced until 1934 with the passage

of that year’s Road Traffic Act.

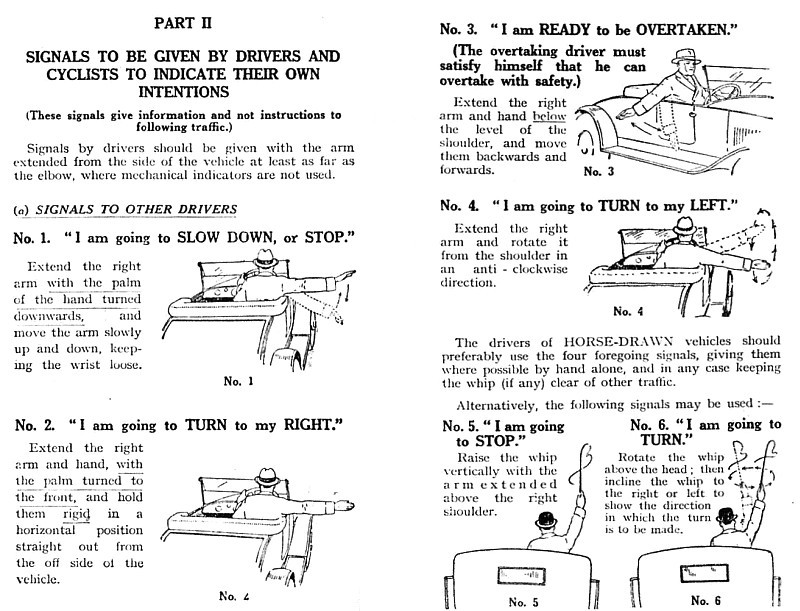

An extract from the 1935 edition of the

Highway Code.

Funding road improvements

The perennial question now arose of ways and means; how were the funds

to be raised to improve roads to meet the new demands of motor traffic?

It was generally agreed that road users should bear at least a portion

of the cost, but no one wanted to return to toll-gates as a means of

raising revenue. The solution adopted by the Chancellor, David

Lloyd-George, was, first, to introduce a graduated tax on cars,

commencing at £2. 2s for a 6½ h.p. engine rising to £32 for an engine in

the range 40 to 60 h.p; second, to add 3d. per gallon duty on petrol.

The proceeds, expected to be £1M annually, were to be paid into a ‘Road

Improvement Fund’, which was to be administered by a newly created ‘Road

Board’. The Board’s role was not to administer road maintenance,

this task being in the hands of local authorities, but to use the Fund

to subsidise new road construction projects, to improve existing roads,

and to put in place measures to suppress road dust. [2]

Although the Road Improvement Fund was ring-fenced and controlled by the

Road Board, any grants made from it had first to be sanctioned by the

Treasury. The Treasury has long believed that all forms of

government revenue should be paid into a common pot, the Consolidated

Fund, from which ministries would compete for funding; to them, the existence

of a ring-fenced fund was anathema. Perhaps for that reason, the Road

Board did not, during its short existence, bring about any great improvements

in the national road network. It initiated a mere handful of road

schemes — these being the Great West Road, a new road between Leicester

and Newark (along the Fosse Way), and the Croydon Bypass — with over 90%

of its grants being for improvements in road surfacing to

suppress dust.

The Road Fund

Under the 1920 Roads Act, the Road Improvement Fund’s assets were

transferred to a ‘Road Fund’ to be administered by the newly created

‘Ministry of Transport’, while that year’s Finance Act removed the duty

on imported motor spirit but introduced increased duties on motor

vehicles. Private cars were to be taxed on cylinder bore,

passenger vehicles on seating capacity, and other commercial vehicles on

unladen weight.

High unemployment after the end of World War I led the government to

provide county councils with grants for road improvements, particularly

where labour was to be recruited from the most affected areas.

There were two unemployment relief programmes, the first from 1920 to

1925 and the second from 1929 to 1930. Grants were limited to

trunk roads and bridges, with the money coming from the Road Fund.

By 1935, some 500 miles of bypasses had been built, including the Derby

Ring Road and the Oxford Northern Bypass, together with the UK’s first

inter-urban highway, the East Lancashire Road (A580, Liverpool to

Salford), constructed between 1929 and 1934 at a cost £8

million.

During the 1920s and 30s, the ring fence around the Road Fund was

gradually removed. Justified by one excuse or another,

sums were transferred from the Road Fund into the Consolidated Fund,

until, following the 1936 Finance Act, the proceeds from road vehicle

duties were paid directly into the Consolidated Fund together with other

taxes. Although not wound up until 1955, the

Road Fund now ceased to exist in practical terms, road transport then

becoming a convenient

source of tax revenues that were easily collectable, and relatively

inelastic and predictable. That situation remained until July

2015, when the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced in his budget speech that taxes paid

on cars will, from 2020-21, by paid into a new Road Fund, the proceeds of which would

be used to pay for road improvement.

――――♦――――

STATE CONTROL AND MODERN ROADS

The Ministry of Transport

World War I. had presented significant problems of transport

co-ordination and this, together with the increasing role of the State,

led in 1919 to the disbanding of the Road Board and the creation of the

Ministry of Transport. [3]

The new ministry took over all central government roles in respect of

roads, bridges and the traffic thereon. It introduced a system of

grants for local authorities to spend on the upkeep and development of

their roads, changed the road taxation system and, among other

initiatives . . . .

|

• carried out the

first national road traffic census in 1922;

• introduced

Traffic Commissioners to control licensing and regulation of

heavy goods vehicle, bus and coach operators, and the

registration of local bus services. Road Traffic Act 1930 (20 &

21 Geo. 5, c. 43);

• made compulsory

third party motor insurance (1930);

• introduced the

Highway Code (1931, enlarged in 1934);

• set up the Road

Research Laboratory to investigate matters of road construction,

design and safety (1933);

• introduced a

national system of road signage (Maybury Report, 1933);

• introduced

guidance and standards for a range of highway design and

management topics (including street lighting, traffic signals

and road safety);

• developed a

national system of speed limits. The Road Traffic Act 1934 (24 &

25 Geo. 5, c. 50) introduced a speed limit of 30 mph in built-up

areas for cars and motorcycles (speedometers were not made

compulsory for new cars until 1937);

• introduced

compulsory driving tests (Road Traffic Act 1934);

• took direct control

of our core road network (centrally managed for the first time

since the Roman occupation) through the Trunk Roads Act 1936 (1

Edw. 8. & 1 Geo. 6, c. 5). This Act placed 4,505 miles of main

roads outside large towns under the control of the Ministry of

Transport, and laid out a blueprint for national roads

development. |

By the mid 1930s the financial crisis of the Depression years was mostly

over. The Ministry of Transport drew up a new five year programme

(1935-1940) for schemes costing £73m, with grants being made to local

highway authorities of between 33% and 85%, depending on the type of

road involved. While some of these schemes were built, the programme was

curtailed by the onset of World War II.

Motorways

Despite the spate of spending on unemployment relief programmes, by the

1930s the

UK’s road infrastructure lagged far behind that of its economic rivals.

By 1939, Germany, Italy and the United States each had extensive

motorway networks (i.e. networks of fast roads reserved for motor vehicles).

Italy led the way with the opening the Milano-Laghi dual highway (Milan

to Varese) between 1924 and 1926. Almost 3,000 miles

of autobahn had been completed in Germany by 1939, and a further 1,000 miles was

under construction, a total exceeding that of the UK’s network 60 years

later!

In Britain, some interest was shown in the development of trunk

routes as motorways. In 1936 the Institution of Highway Engineers

published a plan for a motorway network of some 2,800 miles. This

was followed two years later by a plan put forward by the County

Surveyors’ Society for 1,000 miles of motorway running between London

and Glasgow; London and Newcastle; London and Swansea; London and

Southampton/Portsmouth; Manchester and Hull; Penrith and Scotch Corner;

and Sheffield and Bristol. But war intervened before anything

further could be done.

Even before the War ended, the Ministry of Transport realised that it

would not be long before the country needed motorways, and soon after

the cessation of hostilities, a delegation of road engineers was sent to

Germany to study German practice in building their autobahns.

Legislation was passed in 1949 authorising the construction of ‘special

roads’ — later to be known as ‘motorways’ — to be restricted to specific

types of vehicles, but the continuation of wartime austerity into the post

war years prevented the commencement of motorway building. It was

not until 1955 that orders to build the first two ‘special road schemes’

were made under the 1949 Act, these being the Preston and Lancaster

bypasses, which opened in 1958 and 1960 respectively, later forming

sections of the M6 (finally completed in December 2008 with the opening

of the Cumberland Gap). In 1959, the first major inter-urban

motorway to be opened in Britain was the 74-mile section of the M1

between Junction 5 (Watford) and Junction 18 (Crick/Rugby).

Road administration in England today

The Department for Transport (formerly the Ministry of Transport) is now

the government department responsible for the English transport network

(Transport Scotland manages roads in Scotland and the Welsh Assembly

manages roads in Wales). Among the Department’s roles is to plan

and invest in transport infrastructure, including roads.

The Department is supported by 20 agencies and public bodies, among

which is the Highways Agency, the agency responsible for managing the

core road network, i.e. major motorways and trunk roads of

approximately 4,300 miles in length, routes that account for 34% of all

road travel and 67% of lorry freight travel — approximately four million

vehicles use the network every day. The Agency is also responsible

for the maintenance of 9,000 bridges, 9,000 other structures and 34,000

drainage assets along the network.

Local authorities maintain minor roads, and while the most important

elements of the network are a central government responsibility, the

Highways Agency may ask local authorities to undertake road repairs for

them on an agency basis.

Some important Acts of Parliament relating to roads and their use are

listed in the Appendix.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

SOME IMPORTANT ACTS OF PARLIAMENT

RELATING TO ROADS AND ROAD USE

The Highways Act 1555 (2 & 3 Ph. & Mary c.8): required parishes

to maintain roads in their area, appoint surveyors and introduced the

obligation of statute labour.

Ordinance for the better amending and keeping in repair the Common

Highways within the Nation 1654: provided parishes with powers to levy

rates on landowners in their area for the upkeep of public highways.

Repair of Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire Highway Act

1663 (15 Car. II. c.1): reputedly the first Turnpike Act.

The General Turnpike Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c.84): incorporated into

one law the provisions applicable to all turnpike roads, leaving only

the special provisions applicable to a particular road to be inserted

into its Act. The Act also placed the appointed trustees under the

direction of the county justices. However, the Act did nothing to

remedy the weaknesses of the system. It made no requirement for

trust accounts to be audited on both a financial and a value-for-money

basis, thus leaving some trusts ineffective. Indeed, many became

overwhelmed by the interest due on the mortgages they had raised to the

extent that, by the early 1800s, many were earning only enough revenue

to service interest payments, leaving nothing for road maintenance.

This, and other similar Acts, made no requirements for trusts along the

course of long-distance routes to consolidate ― on average, each trust

had control of 20 to 30 miles of road.

Highway Act 1835 (5 & 6 Will 4 c.50): placed a duty on parish surveyors to maintain

roads in the parish and pay from a rate levied on local landowners. The

Act abolished statute labour in favour of highway rates and encouraged

commercial stationers to produce pro-forma highway account books and

rate books. It

also introduced rules of conduct, including keeping to left when

passing, and fines for breaching these.

Locomotive Act 1861 (24 & 25 Vict c.70): first regulated the weights (12 tons maximum)

and speeds of mechanised road vehicles. Speeds were limited to 5mph in

town and 10 mph in the country.

Locomotives Act 1865 (28 & 29 Vict c.83): sometimes know as the ‘Red Flag Act’ this

reduced speed limits to 2 mph in town and 4 mph in the country and

mechanised vehicles had to be preceded by a person carrying a red flag.

Highways and Locomotives (Amendment) Act 1878 (41 & 42 Vict c.77): transferred the

responsibility for roads maintenance, along with rate levy rights, from

parishes to districts.

Highways Rate Assessment and Expenditure Act 1882 (45 & 46 Vict c.27): introduced

central government grants towards roads expenditure.

The Local Government Act 1888 (51 & 52 Vict c.41): established county councils and county

borough councils in England and Wales and made them responsible for the

repair of county roads and bridges, along with rating powers; and any

other roads they deemed to be ‘main’.

Locomotives on Highways Act 1896 (59 & 60 Vict c.36): introduced classification of

mechanical road vehicles defining a class of ‘light locomotives’ and

increased speed limits to 12 mph. Required vehicles to carry

lights (between one hour after sunset and one hour before sunrise) and

be provided with an audible alarm, such as a bell. The speed limit was

raised from 4 mph to 14 mph.

The Motor Car Act 1903 (3 Edw.7, c. 36): introduced the registration of motor vehicles,

the licensing of drivers and the offence of reckless driving. The Act

raised the speed limit to 20 mph and introduced regulations regarding

the minimum braking ability of vehicles.

The Development and Roads Improvement Funds Act 1909

(9 Edw.

7. c. 47): introduced a horsepower and a (3d) petrol tax, the

net proceeds of which were paid into the Road Improvement Fund, later

known as the Road Fund, which was managed by the Road Board created by

the Act. The Road Board did not undertake construction or maintenance of

roads, but controlled grants to local authorities to maintain them. It

was stated that the Treasury would not gain from the new duties and that

all the revenue raised would be spent on the roads ― this ideal was

short lived.

Ministry of Transport Act 1919 (10 Geo. 5 c.50): created the Ministry of Transport

and abolished to Road Board.

Finance Act 1920 (10 & 11 Geo. 5 c. 18): provided for grants to local authorities for the

upkeep and improvement of their roads.

Roads Act 1920 (10 & 11 Geo. 5 c.72): provided for grants to local authorities for the

upkeep and improvement of their roads.

Road Traffic Act 1930 (20 & 21 Geo. 5 c.43): removed all speed

limits for motor cars, but introduced the 30 mph speed limit for buses

and coaches. It introduced a highway

code and compulsory third party motor insurance. On the licensing of

drivers, it including provisional licences and driving tests for

disabled drivers.

The Road Traffic Act 1934 (24 & 25 Geo. 5. c. 50): reintroduced a

speed limit for cars of 30 mph in built-up areas and made the driving

test compulsory for all new drivers. The Belisha beacon (named after the

Transport Minister) was introduced to clearly identify pedestrian

crossings.

Finance Act 1936 (26 Geo. 5 & 1 Edw. 8 c.34): abolished the special arrangement for motor taxes

which were thenceforth to be paid into the consolidated fund.

Trunk Roads Act 1936 (26 Geo. 5 & 1 Edw. 8 c.5): gave the Ministry of Transport direct

responsibility for a network of trunk roads (initially 4,460 miles in

length) in the United Kingdom but excluding Northern Ireland. Thirty

major roads were classed as trunk roads and the minister of transport

took direct control of them and the bridges across them.

Trunk Road Act 1946 (9 & 10 Geo. 6. c. 30): extended the trunk road

network to

8,190 miles.

Transport Act 1947 (10 &

11 Geo. 6. c. 49): nationalised the railways, long-distance road

haulage and various other types of transport and ancillary activities

and created the British Transport Commission to oversee their

activities.

Special Roads Act 1949 (12 & 13 Geo. 6. c.32.): allowed the construction of roads

restricted to specific types of vehicles and restricted access by the

utilities ― in practice Motorways.

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES

1. Motor Car Act, 1903 (3 Edward VII. c. 36).

2. Development and Road Improvement Funds Act 1909 (9 Edward VII, c.

47). Section 8 (5) of Part II of the Act reads:

“For the purposes of

this Part of this Act the expression ‘improvement of roads’ includes the

widening of any road, the cutting off the corners of any road where land

is required to be purchased for that purpose, the levelling of roads,

the treatment of a road for mitigating the nuisance of dust, and the

doing of any other work in respect of roads beyond ordinary repairs

essential to placing a road in a proper state of repair; and the

expression ‘roads’ includes bridges, viaducts, and subways.”

3. Ministry of Transport Act 1919 (9 & 10 Geo. 5, c. 50).

――――♦――――

[Next Page] |