|

WHILE

the Tories, the Whigs, the Peelites—in fact, all the parties we have

hitherto commented upon—belong more or less to the past, the Free Traders

(the men of the Manchester School, the Parliamentary and financial

reformers) are the official representatives of modern English society,

the representatives of that England which rules the market of the world.

They represent the party of the self-conscious bourgeoisie, of industrial

capital striving to make available its social power as a political power

as well, and to eradicate the last arrogant remnants of feudal society.

This party is led on by the most active and most energetic portion of the

English bourgeoisie—the manufacturers.

|

|

|

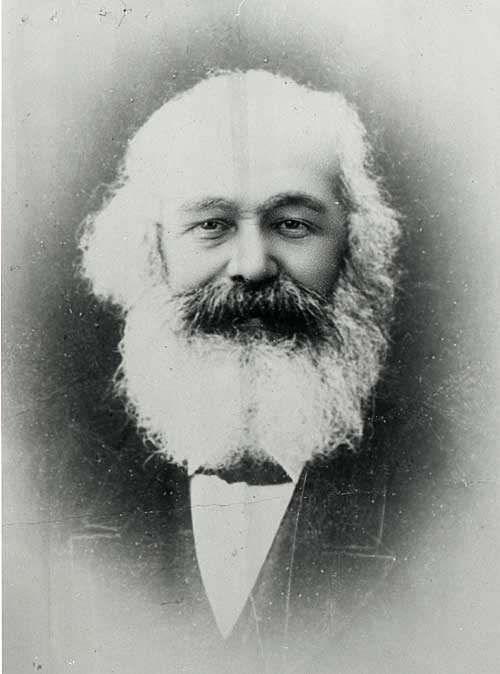

Karl Marx

(1818-63) |

What they demand is the complete and undisguised ascendancy

of the bourgeoisie, the open, official subjection of society at large

under the laws of modern bourgeois production, and under the rule of those

men who are the directors of that production. By Free Trade they

mean the unfettered movement of capital, freed from all political,

national and religious shackles. The soil is to be a marketable

commodity, and the exploitation of the soil is to be carried on according

to the common commercial laws. There are to be manufactures of food

as well as manufactures of twist and cottons, but no longer any lords of

the land.

There are, in short, not to be tolerated any political or

social restrictions, regulations or monopolies, unless they proceed from

"the eternal laws of political economy," that is, from the conditions

under which capital produces and distributes. The struggle of this

party against the old English institutions, products of a superannuated,

an evanescent stage of social development, is resumed in the watchword:

Produce as cheap as you can, and do away with all the faux frais of

production (with all superfluous, unnecessary expenses in production).

And this watchword is addressed not only to the private individual, but to

the nation at large principally.

Royalty, with its "barbarous splendours," its court, its

Civil List and its flunkeys—what else does it belong to but to the

faux frais of production? The nation can produce and exchange

without royalty; away with the crown. The sinecures of the nobility,

the House of Lords? faux frais of production. The large

standing army? faux frais of production. The Colonies?

faux frais of production. The State church, with its riches, the

spoils of plunder or of mendicity? faux frais of production.

Let parsons compete freely with each other, and everyone pay them

according to his own wants. The whole circumstantial routine of

English law, with its Court of Chancery? faux frais of production.

National wars? faux frais of production. England can exploit

foreign nations more cheaply while at peace with them.

You see, to these champions of the British bourgeoisie, to

the men of the Manchester School, every institution of old England appears

in the light of a piece of machinery as costly as it is useless,

and which fulfils no other purpose but to prevent the nation from

producing the greatest possible quantity at the least possible expense and

to exchange its products in freedom. Necessarily their last word is

the bourgeois republic, in which free competition rules supreme in

all spheres of life; in which there remains altogether that minimum

only of government which is indispensable for the administration,

internally and externally, of the common class-interest and business of

the bourgeoisie, and where this minimum of government is as

soberly, as economically, organised as possible. Such a party in

other countries would be called democratic. But it is

necessarily revolutionary, and the complete annihilation of Old England as

an aristocratic country is the end which it follows up with more or less

consciousness. Its nearest object, however, is the attainment of a

Parliamentary reform which should transfer to its hands the legislative

power necessary for such a revolution.

But the British bourgeois are not excitable Frenchmen. When

they intend to carry a Parliamentary reform they will not make a

Revolution of February. On the contrary. Having obtained, in 1846, a grand

victory over the landed aristocracy by the repeal of the Corn Laws, they

were satisfied with following up the material advantages of this victory,

while they neglected to draw the necessary political and economical

conclusions from it, and thus enabled the Whigs to reinstate themselves

into their hereditary monopoly of government.

During all the time from 1846 to 1852, they exposed

themselves to ridicule by their battle-cry—broad principles and practical

(read small) measures. And why all this? Because in

every violent movement they are obliged to appeal to the working class. And if the aristocracy is their vanishing opponent, the working class is

their arising enemy. They prefer to compromise with their vanishing

opponent rather than to strengthen the arising enemy, to whom the future

belongs, by concessions of more than apparent importance. Therefore, they

strive to avoid every forcible collision with the aristocracy; but

historical necessity and the Tories press them onwards. They cannot avoid

fulfilling their mission, battering to pieces Old England, the England of

the past, and the very moment when they will have conquered exclusive

political dominion, when political dominion and economical supremacy will

be united in the same hands, when, therefore, the struggle against capital

will no longer be distinct from the struggle against the existing

government—from that very moment will date the social revolution of

England.

We now come to the Chartists, the politically active portion of the

British working class. The six points of the Charter which they contend

for contain nothing but the demand of universal suffrage and of the conditions without which universal suffrage would be illusory

for the working class: such as the ballot, payment of members, annual

general elections. But universal suffrage is the equivalent for political

power for the working class of England, where the proletariat form the

large majority of the population, where, in a long, though underground

civil war, it has gained a clear consciousness of its position as a class,

and where even the rural districts know no longer any peasants, but

landlords, industrial capitalists (farmers) and hired labourers. The

carrying

of universal suffrage in England would, therefore, be a far more

socialistic measure than anything which has been honoured with that name

on the Continent.

Its inevitable result here, is the political supremacy of the working

class.

I shall report, on another occasion, on the revival and reorganisation of

the Chartist Party. For the present I have only to treat of the recent

election.

To be a voter for the British Parliament, a man must occupy, in the

Boroughs, a house rated at £10 to the poor's rate, and, in the counties he

must be a freeholder to the annual amount of 40 shillings or a leaseholder

to the amount of £50. From this statement alone it follows that the

Chartists could take, officially, but little part in the electoral battle

just concluded. In order to explain the actual part they took in it, I

must recall to mind a peculiarity of the British electoral system:

Nomination day and Declaration day! Show of hands and Poll!

When the candidates have made their appearance on the day of election, and

have publicly harangued the people, they are elected, in the first

instance, by the show of hands, and every hand has the

right to be raised, the hand of the non-elector as well as that of the

elector. For whomsoever the majority of the hands are raised, that person

is declared by the returning officer to be (provisionally) elected by show

of hands. But now the medal shows its reverse.

The election by show of hands was a mere ceremony, an act of formal

politeness toward the "sovereign people," and the politeness ceases as

soon as privilege is menaced. For if the show of hands does not return the

candidates of the privileged electors, these candidates demand a poll;

only the privileged electors can take part in the poll, and whosoever has

there the majority of votes is declared duly elected. The first election,

by show of hands, is a show satisfaction allowed, for a moment, to public

opinion, in order to convince it, the next moment, the more strikingly of

its impotency.

It might appear that this election by show of hands, this dangerous

formality, had been invented in order to ridicule universal suffrage, and

to enjoy some little aristocratic fun at the

expense of the "rabble" (expression of Major Beresford, Secretary

of War). But this would be a delusion, and the old usage, common

originally to all Teutonic nations, could drag itself traditionally down

to the nineteenth century, because it gave to the British class Parliament,

cheaply and without danger, an appearance of popularity.

The ruling classes drew from this usage the satisfaction that the mass of

the people took part, with more or less passion, in their sectional

interests as its national interests. And it was only since the

bourgeoisie took an independent station at the side of the two official

parties, the Whigs and the Tories, that the working masses stood up, on

the nomination days in their own name. But in no former year has the

contrast of show of hands and poll, of Nomination day and Declaration day,

been so serious, so well-defined by opposed principles, so threatening, so

general, upon the whole surface of the country as in this last election of

18 52.

And what a contrast! It was sufficient to be named by show of hands in

order to be beaten at the poll. It was sufficient to have had the majority

at a poll, in order to be saluted, by the people, with rotten apples and

brick-bats.

The duly elected members of Parliament, before all, had a great deal to

do, in order to keep their own parliamentary bodily-selves in safety. On

one side the majority of the people, on the other the

twelfth-part of the whole population, and the fifth-part of the sum total

of the male adult inhabitants of the country. On one side enthusiasm, on

the other side bribery. On one side parties disowning their own

distinctive signs, Liberals pleading the conservatism, Conservatives

proclaiming the liberalism of their views; on the other, the people,

proclaiming their presence and pleading their own cause. On one side a

warn-out engine which, turning incessantly in its vicious circle, is never

able to move a single step forward, and the impotent process of friction

by which all the official parties gradually grind each other into dust;

on the other, the advancing mass of the nation, threatening to blow up the

vicious circle and to destroy the official engine.

I shall not follow up, over all the surface of the country, this contrast

between nomination and poll, of the threatening electoral demonstration of

the working class, and the timid electioneering manœvures of the ruling

classes. I take one borough from the mass,

where the contrast is concentrated in a focus: the Halifax Election. Here

the opposing candidates were: Edwards (Tory), Sir Charles Wood (late Whig

Chancellor of the Exchequer, brother-in-law to Earl Grey), Frank Crossley

(Manchester man), and finally Ernest Jones, the most talented, consistent

and energetic representative of Chartism.

Halifax being a manufacturing town, the Tory had little chance. The

Manchester man, Crossley, was leagued with the Whigs. The serious

struggle, then, lay only between Wood and Jones; between the Whig and the

Chartist.

Sir Charles Wood made a speech about half-an-hour, perfectly inaudible at

the commencement, and during its latter half, to the disapprobation of the

immense multitude. His speech,

as reported by the reporter, who sat close to him, was merely a

recapitulation of the Free Trade measures passed, and an attack on Lord

Derby's government, and a laudation of "the unexampled prosperity of the

country and the people"! ("Hear, hear.") He did not propound one single

new measure of reform, and but faintly, in very few words, hinted at Lord

John Russell's bill for the franchise.

I give a more extensive abstract of Ernest Jones's

speech, as you will not find it in any of the great London ruling-class

papers. Ernest Jones, who was received with immense enthusiasm, then

spoke as follows:—

"Electors and non-electors, you have met upon a great and solemn

festival. To-day the Constitution recognises universal suffrage in theory

that it may, perhaps, deny it in practice on the

morrow. To-day the representatives of two systems stand before you, and

you have to decide beneath which you shall be ruled for seven years. Seven

years—a little life! I summon you to pause upon the threshold of those

seven years; to-day they shall pass slowly and calmly in review before

you; to-day decide, you 20,000 men! that perhaps five hundred may undo

your will to-morrow. ("Hear, hear.")

"I say the representatives of two systems stand before you. Whig, Tory

and moneymongers are on my left, it is true; but they are all as one. The moneymonger says, buy cheap and sell dear. The

Tory says, buy dear, sell dearer. Both are the same for labour.

But the former system is in the ascendant, and pauperism rankles at its

root. That system is based on foreign competition. Now, I assert, that

under the buy cheap and sell dear principle, brought to bear on foreign

competition, the ruin of the working and small trading classes must go on. Why? Labour is the creator of all wealth. A man must work before a grain

is grown, or a yard is woven. But there is no self-employment for the

working man in this country. Labour is a hired commodity—labour is a

thing in the market that is bought and sold; consequently, as labour

creates all wealth, labour is the first thing bought—'Buy cheap, buy

cheap! Labour is bought in the cheapest market. But now comes the next: 'Sell dear, sell dear!' Sell what? Labour's produce. To whom?—to

the foreigner—aye! and to the labourer himself—for labour, not being

self-employed, the labourer is NOT the partaker of the first-fruits of his

toil.

"'Buy cheap, sell dear.' How do you like it? 'Buy cheap, sell dear.'

Buy the working man's labour cheaply and sell back to that very working

man the produce of his own labour dear!

The principle of inherent loss is in the bargain. The employer buys the

labour cheap—he sells, and on the sale he must make a profit; he sells

to the working man himself—and thus every bargain between employer and

the employed is a deliberate cheat on the part of the employer. Thus

labour has to sink through eternal loss, that capital may rise through

lasting fraud.

"But the system stops not here. This is brought to bear on foreign

competition—which means, we must ruin the trade of other countries, as we

have ruined the labour of our own. How does it work?

The high-taxed country has to undersell the low-taxed. Competition abroad

is constantly increasing—consequently cheapness

must increase constantly also. Therefore, wages in England must keep

constantly falling. And how do they effect the fall? By surplus labour. And how do they obtain the surplus labour? By monopoly of

the land which drives more hands than are wanted into the factory. By

monopoly of machinery which drives those hands into the street—by woman

labour which drives the man from the shuttle—by child labour which drives

the women from the loom. Then planting their foot upon that living base of

surplus they press its aching heart beneath their heel and cry—'Starvation.

Who will work? A half-loaf is better than no bread at all'—and the

writhing mass grasps greedily at their terms. (Loud cries of "Hear,

hear.")

"Such is the system for the working man. But, electors! how does it

operate on you? How does it affect home trade, the

shopkeeper, poor's rate and taxation? For every increase of competition

abroad, there must be an increase of cheapness at home. Every increase of

cheapness in labour is based on increase of labour surplus, and this

surplus is obtained by an increase of machinery. I repeat, how does this

operate on you? The Manchester Liberal on my left establishes a new

patent and throws three hundred men as a surplus in the streets. Shopkeepers! Three hundred

customers less. Ratepayers! Three hundred paupers more! (Loud cheers.)

"But, mark me. The evil stops not there. These three hundred men operate

first to bring down the wages of those who remain at work in their own

trade. The employer says: 'Now I reduce

your wages.' The men demur. Then he adds: 'Do you see these three hundred

men who have just walked out you may change places if you like, they are

sighing to come in on any terms, for they are starving.' The men feel it,

and are crushed. Oh! you Manchester Liberal! Pharisee of politics! Those men are listening—have I got you now?

"But the evil stops not yet. Those men, driven from their own trade, seek

employment in others when they swell the surplus and bring wages down. The

low-paid trades of to-day were the high

paid once—and the high-paid of to-day will be the low-paid soon. Thus the

purchasing power of the working classes is diminished every day, and with

it dies home trade. Mark it, shopkeepers, your customers grow poorer and

your profits less, while your paupers grow more numerous and your poor's

rates and your taxes rise. Your receipts are smaller, your expenditure is

more large. You get less and pay more. How do you like the system? On you

the rich manufacturer and landlord throws the weight of

poor's rate and taxation. Men of the middle class! You are the

tax-paying machine of the rich. They create the poverty that creates

their riches, and they make you pay for the poverty they have created.

The landlord escapes it by privilege, the manufacturer by repaying himself

out of the wages of his men, and that reacts on you. How do you like

the system?

"Well, that is the system upheld by the gentlemen on my left. What then

do I propose? I have shown the wrong. That is something. But I do more. I

stand here to show the right, and prove it so." (Loud cheers.)

Ernest Jones then went

on to expose his own views on political and economical reform, and

continued as follows:—

"Electors and non-electors! I have now brought before you some of the

social and political measures, the immediate adoption of which I advocate

now, as I did in 1847. But, because I tried to extend

YOUR liberties,

MINE

were curtailed. ('Hear, hear:') Because I tried to rear the temple of

freedom for you all, I was thrown into the cell of a felon's jail; and

there, on my left, sits one of my chief jailers. (Loud and continued

groans, directed towards the left.) Because I tried to give voice to

truth, I was condemned to silence. For two years and one week he cast me

into a prison in solitary confinement on the silent system, without pen,

ink or paper, but oakum picking as a substitute. Ah! (turning to Sir

Charles Wood), it was your turn for two years and one week; it is mine

this day. I summon the angel of retribution from the heart of every

Englishman here present. (An immense burst of applause.) Hark! You feel

the fanning of his wings in the breath of this vast multitude. (Renewed

cheering, long continued.) You may say this is not a public question. But

it is. ("Hear, hear.") It is a public question, for the man who cannot

feel for the wife of the prisoner, will not feel for the wife of the

working man. He who will not feel for the children of the captive, will

not feel for the children of the labour

slave. ("Hear, hear," and cheers.) His past life proves it, his

promise of to-day does not contradict it. Who voted for Irish coercion,

the gagging bill and tampering with the Irish Press?

The Whig—there he sits; turn him out! Who voted fifteen

times against Hume's motion for the franchise; Locke King's on the

counties; Ewart's for short Parliaments; and

Berkeley's for the ballot? The Whig—there he sits; turn him out! Who

voted against the release of Frost, Williams and Jones? The Whig—there

he sits; turn him out! Who voted against reducing the Duke of

Cambridge's salary of £12,000, against all

reductions in the army and navy; against the repeal of the window tax, and

forty-eight times against every other reduction of taxation, his own

salary included? The Whig—there he sits; turn him out! Who voted

against the repeal of the paper duty, the advertisement duty, and the

taxes on knowledge? The Whig—there he sits; turn him out! Who voted for the batches of new bishops,

vicar rare, the Maynooth grant, against its reduction and against

absolving dissenters from paying Church rates? The Whig—there he sits;

turn him out! Who voted against all inquiry into the adulteration of food? The Whig—there he sits; turn him out! Who voted against lowering the

duty on sugar, and repealing the tax on malt? The Whig—there he sits;

turn him out! Who voted against shortening the nightwork of bakers,

against inquiry into the condition of frame-work knitters, against medical

inspectors of workhouses, against preventing little children from working

before six in the morning, against parish relief for pregnant women

of the poor and against the Ten Hours Bill? The Whig—there he sits;

turn him out! Turn him out in the name of humanity and of God! Men of

Halifax! Men of England! The two systems are before you. Now judge and

choose!"

It is impossible to describe the enthusiasm kindled by this speech, and

especially at the close; the voice of the vast multitude, held in

breathless suspense during each paragraph, came at each pause like the

thunder of a returning wave, in execration of the representative of

Whiggery and class-rule. Altogether it was a scene that will long be

unforgotten. On the show of hands being taken, very few and those chiefly

of the hired or intimidated, were held up for Sir C. Wood; but almost

everyone present raised both hands for Ernest Jones, amidst cheering and

enthusiasm it would be impossible to describe.

The Mayor declared Mr. Ernest Jones and Mr. Henry Edwards to be elected by

show of hands. Sir. C. Wood and Mr. Crossley then demanded a poll.

What Jones had predicted took place; he was nominated by 20,000 votes;

but the Whig (Sir Charles Wood) and the Manchester man (Crossley) were

elected by 500 votes. |