|

Six hundred pages of eloquent prose about the Sonnets make a pretty large addition to the Shakspeare library.

Mr. Massey's excuse for writing so big a book is that he has a new theory to propose, new facts to adduce, a new arrangement to make, a new reading to evolve.

He has certainly entered into the personal and political history of Shakspeare's time with a good deal of pains; and if his theory should turn out to be less novel than he fancies, his reading less conclusive than he believes, the praise of working on a safe line and of throwing out some excellent suggestions may still be due to him.

It is something to have made a happy guess in explanation of the darkest enigma of our poetical literature.

Mr. Massey's theory is, that the Sonnets may be divided, mainly, into two

series,—1, The Southampton Sonnets; and, 2, The Herbert Sonnets.

The Southampton series, he finds, are beyond comparison the more important, both as to number and quality.

They tell him a real story of men and women—of passion, jealousy,

revenge—that had an actual existence on the earth, and in which Southampton, Elizabeth Vernon and Lady Rich had each a living part, as lover, mistress, rival; and in which Shakspeare had also his part, as dramatist, versifier, friend.

|

|

|

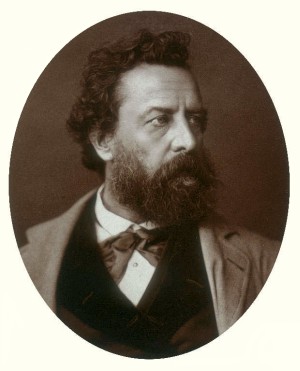

William Hepworth Dixon

(1821-59)

The Athenæum's Editor and author of this review. |

Some part of this set of propositions we hold to be true beyond all cavil.

If Southampton is not the male friend addressed by Shakspeare in the earlier portion of these poems, evidence counts for nothing.

Why, he is indicated in general and in particular—as regards his class and his

person—by the most certain marks. The friend addressed by the poet is young (S. i), of gracious presence (x), noble of birth (xxxvii), rich in money and land (xlviii), a town gallant (xcv), a man vain and exacting (ciii).

Those general characteristics, though vague and impersonal, exclude a good many pretenders to the office of Shakspeare's friend.

They exclude the whole class of actors, playwrights and managers; the whole tribe of Shakspeare's kinsmen and townsmen; all the imaginary Hugheses, Hathaways, and Hartes.

They confine our field of choice to men of the rank and character of Essex, Rutland, Pembroke, and Southampton; men about whom we have a good deal of information from other sources, whose fortunes we can follow, and whose characters we call read, by many distinct and independent lines.

Having found that our hero is young, rich, noble, profligate, we may go a little further, for particular marks, and shall assuredly find them.

Indeed, the poet's friend is described in full; discriminated from all his fellows by a number of special marks, some of which appear to have escaped Mr. Massey's critical eye.

1. His mother was living when the Sonnets were

written.—S. iii.

2. He was still a single man.—S. iv. '

3. His mother was a widow.—S. ix.

4. He had had some previous poetical connexion with Shakspeare.—Ss. xvi, xvii, xxvi.

5. He had publicly honoured the poet.—S. xxxvi.

6. He was absent from London.—Ss. xxviii, xxxix, xliv.

7. He was away in "slight air and purging fire''—on a naval

expedition.—S. xlv.

8. Messengers had come to England bringing news of his health.—S. xlv.

9. This absence from England was in summer and autumn.—S. xcvii.

10. Shakspeare had, at this time of his absence, known him just three

years.—S. civ.

11. Shakspeare had previously dedicated poetry to him.—Ss. lxxxii, cii.

12. He was a man who could be described as "all the world" to

Shakspeare.—S. cxii.

Now all these twelve criteria (which admit of being tested in a few minutes) mark the man Southampton with unerring truth.

Passing in review the noblemen who were then young, rich, wealthy, and profligate, we find one, and only one, to whom the twelve criteria will apply.

Essex was not single. Rutland had no previous connexion with the poet, and had never publicly honoured him.

Pembroke was a more boy, to whom Shakspeare had not dedicated a book.

In 1595, Pembroke, then William Herbert, was 'only fifteen years old, and

his mother was not a widow. Every point in these twelve criteria; meet in Southampton.

So far Mr. Massey treads on safe, historical ground, over which we can follow him with the utmost confidence.

Then he goes on to say 'that the poet was employed by Southampton to put a series of real incidents into verse; to write a number of sonnets expressing Southampton's passion for his mistress, Elizabeth

Vernon,—others expressing Elizabeth Vernon's jealousy of Lady Rich.

According to this idea, the Southampton Sonnets may be divided into two

classes—Personal and Dramatic; those which spring out of Shakspeare's personal feeling's towards the Earl, his friend, and those which, at the Earl's suggestion, he devotes, dramatically, to an illustration of the little comedy on between lover and mistress.

These two divisions would exhaust the Southampton series. By curious transposition, the Sonnets, it is evident, may be thrown into a number of tolerably consistent groups.

Do they acquire new meaning by this arrangement? Mr. Massey is confident they do; and whether he is right or wrong in his interpretation, we think his suggestion that

some actual facts underlie the poetical structure excellent, and one that merits further study by Shakspeare scholars.

Of course, when we are told that the Sonnets contain a true history of human

passion,—that the people who address each other were once alive on

earth,—it becomes necessary to inquire where the critic learns all this secret history.

Is there any reason to believe that Southampton, Mistress Vernon, and Lady Rich underwent, in actual life, any of the love, jealousy and reconciliation now assumed?

Here, the hard fact runs against the convenient fancy. We know nothing of the kind.

That Southampton was in love with Elizabeth Vernon, and that he married her, we know.

Of his faithlessness to her at any time, either before or after marriage, there is no hint.

Of any jealousy on her part against Lady Rich there is no suspicion.

We cannot believe either that Lord Southampton was ever in love with Lady Rich, or that Elizabeth Vernon could have thought such a passion possible in her lover.

Penelope Rich was no saint; she had been in love with Sydney in her youth; she had been basely sold to Lord Rich, a man whom she did not love; she was, in her middle-life, attached most truly to Montjoy.

But, even if she had been the Lascivious Grace which Mr. Massey assumes, Southampton was, of all men on earth, the one who never could have approached her with any speech of love.

She was almost old enough to be his mother. She was Essex's sister.

From the moment of Sydney's death, she had been the consolation of Montjoy, Southampton's friend and patron.

She had not absolutely and finally left her husband's roof; but her relations to Montjoy were open; her children bore his name, and they were publicly owned as his.

In everything but the name she was his wife, as she became a few years later even in name.

Remembering all that Montjoy was to Southampton, can any man believe that the young noble, however flighty, would have gone to Lady Rich with an avowal of guilty love, so openly as to have caused a family and public

scandal, wringing the heart of his own beautiful and adoring mistress with the passionate misery found in the Sonnets? We see no issue out of such a difficulty.

Again, in order to accept Mr. Massey's theory, we must imagine not only that all these loves and jealousies were true, but that either while they were in progress, or when they were happily past, the parties who had been so miserable under them desired to have a comedy made of their own innermost feelings, and actually engaged the poet to put their sufferings into verse.

Is that a likely course for happy lovers to pursue? Obstacles meet us on every side.

If Southampton had given his lady cause of offence, can we imagine him asking Shakspeare to endow his sin with poetic life?

If Elizabeth Vernon had been truly in a rage against her cousin, Lady

Rich, would she have liked her husband's friend to make a play of her

agony and remorse?

We will not say that such a thing was impossible.

Knowing the strange history of the love-poems written by Sydney of Lady Rich, we hesitate to affirm with confidence that such and such a course must have been taken by the Elizabethans, because we feel what would be done, under like circumstances, by the Victorians.

But we think it so far unlikely that Shakspeare could have been employed to illustrate a passage which was no credit to his patron that, in the face of Mr. Massey's eloquent and ingenious pleading, we must still hesitate to build a theory of interpretation upon it.

Mr. Massey does not feel our difficulties, and he pronounces on the subject with an enviable confidence.

The Herbert Sonnets—some of which Mr. Massey thinks that Herbert himself

wrote—are also connected with Lady Rich. Indeed, the 'Lascivious Grace' appears to exercise a kind of fascination over the critic, some of whose finest passages are devoted to a description of her charms.

This picture of her beauty is good and true:—

"It has been assumed that the lady of these sonnets was the black-eyed, black-haired beauty, with a complexion

of the swarthiest hue. This must result from her black eyes having unduly influenced the reader's imagination.

In the old age, says the first of these sonnets, 'black was not counted fair.'

But the Poet is not speaking of women whose faces are black; when he says that black is now your only true beauty, he does not mean

'Blacks.' It is the lady's eyes, not her complexion, that is black.

Her character may be black, but her countenance is not: she is neither a blackamoor nor a 'black beauty.'

Lady Rich did appear in one of the Court masques called the 'Masque of Blackness,' as an Ethiop beauty, with her hands, arms, and face blackened to the required tint, whilst her naked white feet dazzled the eyes as they dallied with a running stream; but this cannot be the complexion celebrated.

Nor did it need Shakspeare to tell us that the negro complexion was not wont to be admired in the antique time.

The subject touches in a most particular way the old poetic quarrel respecting the rival charms of black eyes and blue.

In the old time the frank eye of bonny English blue or good honest grey, bore away the palm as the favourite of our Poets.

Black eyes were alien to the Northern ideal of beauty. But here is such a triumph of this colour that black is Beauty's only wear.

Black eyes and black eyebrows, not a black face nor a dark complexion!

It is the eyes alone that have put on mourning, and become 'pretty mourners.'

Now, the eyes would not have put on mourning if the face had been very swarthy; the hair

black; and it is the eyes alone that are 'so suited' in mourning hue.

There are two distinct excuses why the eyes should have assumed this mourning and

put on this black; neither of which would have had a starting-point if the lady had been altogether dark; then it would have been her beauty that was dressed in the mourning-robe, not her eyes and brows alone.

It will be seen that there is something very special about these black eyes

—in opposition to which something fair is required and implied, or where is the motive?— and when we have lifted the veil of mystery through which they have

glittered, and behind which the face has been so long concealed, we shall, I think, find the supposed

dark lady of Shakspeare's Sonnets is the famous golden-haired and black-eyed beauty Penelope Rich, the first love of Philip Sidney, the cousin of Elizabeth Vernon, the sister of Essex, the Helen of the Elizabethan poets.

She was 'a most triumphant lady, if report be square to her,' whose lively blood ran blush-full of the summer in her in her veins.

As wonderful a piece of work as ever Nature cunningly compounded, and her beauty was of the rarest kind known in the North.

Sidney, who proclaimed his love for her and his joy therein, 'tho nations might count it shame' and in the heavens set her starry name, has left vivid Venetian paintings of her as the 'Stella' of his Sonnets, the 'Philoclea' of his Areadia— whereby the lady glows in the mind, warm with life once more.

She had hair of tawny gold, with tresses lustrous as those of the Greek day-god.

Sidney described them as 'beams of gold caught in a net. In complexion of face she was nearly a brunette.

Her Poet has exactly marked the colour of her cheek as a 'kindly

claret,' which is definite as the tint described by Dante as being 'less then that of the rose, but more than that of the

violets'; it is the ripe red that has the purple of peach-bloom in its dye, and is only seen in the deep

complexion—hardly ever found with golden hair.

|

Of all complexions the culled sovereignty

Did meet as at a fair in her fair cheek. |

And her eyes were

black—'black stars,' Sidney calls them. Elsewhere they are twin-children of the Sun, begotten black in the fervour of his affection.

So black were the eyes that those who have attempted to depict them seem to have felt, as they say of their very dark women in

Angoulème, they were 'born when coal was in blossom.' Sidney calls them eyes 'of touch,' that is, of black marble.

This opposition of blonde and brunette was striking striking as is the rich gold and the gorgeous black of the humble-bee.

Thus her beauty had the utmost contrast and chiaroscuro with which Nature paints the human face.

Day, with its golden lights, may be said to have dwelt in her hair: Night and starlight, in her eyes.

The light above and the dark below—the fair hair with its Northern frankness of smile and the black burning eyes of the South glittering deadly-brilliant under black velvet eyebrows, with what Keats might have called their

ebon diamonding, gave that piquancy of character to her appearance on which the poets loved to dwell."

To explain the main enigma of the

Sonnets—the dark lady, the forsworn wife, the treacherous friend—Mr. Massey supposes that Pembroke fell into love with Penelope Rich, into a passion not only guilty but degrading; and that he employed Shakspeare to write the story of this abominable love.

But here, again, we cannot follow him from his premises to his conclusions.

Penelope was double Pembroke's age; she had half-a-dozen children grown up.

She was Montjoy's mistress-wife, and Montjoy to Herbert a friend, almost a father.

Nothing in the letters of that time suggests the idea of a guilty passion between this

middle-aged woman and this tender youth.

If this passion were genuine, it would be one of the strangest aberrations of the heart on record.

But the existence of such a madness on the part of Pembroke is only part of the difficulty.

Before accepting it as a key to the Sonnets, we must convince ourselves that Shakspeare could have lent himself to its glorification; not in his youth and in the time of his poverty, but in his ripest years after he had become a gentleman at Stratford.

We cannot credit such a thing. |