|

"Now the labourer's task is o'er!" I did not find Mr. Gerald Massey singing those words, but I did find him a happy

man—the Happy Warrior who had accomplished his task. He might say that he has been working against time for eternity, because now a book into which he has been putting his head and heart is finished, and is about to appear through Mr. Fisher Unwin.

It was this circumstance which took me to see Mr. Massey at his little home in Norwood, where he has lived the simple life of a recluse for many years.

He will be eighty in May, which is old as age goes with men, but Mr. Massey is not as others.

He is frail, weary and worn in body, but his mind is fresh and buoyant as a boy's, and his eyes, which are the windows of a soul, shine bright and sparkle mirth.

"I shall," he said, "be talking and laughing five minutes before I hop off."

"If it were not," he added, a little later, "that there has been guidance in my life, I might just as well hop off tomorrow."

What a romance has Mr. Massey's life been! He was born among the canal people of

England—at Tring in Herts—and he worked and sang himself upward until in the Fifties and Sixties he was one of the voices of England.

Some of his verse went round the world like the tap of the British drum, but to a very different note.

Then he ceased to sing and gave himself to what he thought a greater work; in the words of the sub-title of one of his second-self books, "To recover and reconstitute the lost

origins of the myths and mysteries, types and symbols of religion and language, with Egypt for a mouthpiece and Africa as a birthplace."

He ceased being a poet to become a searcher for the Light of the World, and the last thirty years of his life and more have been unceasingly given to that quest.

His gleanings were described in "A Book of the Beginnings" which appeared in 1881, and in "The Natural Genesis" which came out two years later, and to-day the series is being completed with a third work in two volumes, "Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World."

"I have written other books," says Mr. Massey in his preface, "but this I look on as the exceptional labour which has made my life worth living.

Comparatively speaking 'A Book of Beginnings' was written in the dark, 'The Natural Genesis' was written in the twilight, whereas 'Ancient Egypt' has been written in the light of day."

Well, that makes it clear why we should, at this moment, desire to talk with Mr. Gerald Massey, and we shall take him first as the

ex-poet—a term at which he laughed but which he would not repudiate—and then as the prophet digging backward in order to illuminate the future.

I.

I asked Mr. Massey if he did not sometimes shed a tear over the verse which he has been so content to bury away, because, strange as it may seem, there really is not an edition of his poetical works on the market.

His daughter, who inherits so many of her father's fine qualities, looked up at this question and nodded assent to it.

But the veteran himself was not to be moved to tears over such a small affair as poetry, although he has the tenderest heart of all the Grand Old Men of the world.

"I once thought I might be a poet," he said, "but I have come to this, that I would be more content with an ant-heap in Central Africa than with a seat on the classical Mount of Parnassus.

The ant-heap, as you will know, was the first form of a building, the suggester and originator of the conical hut of Africa.

Verse passes like a tide, but I must admit that the writing of mine taught me to write prose.

There is no school, no mental discipline, like the composition of verse.

I will tell you a curious thing in that connection. I used to suffer from a pain in my side, and two or three

doctors—without charging me anything, I think—gave it as heart trouble.

I never wrote a stanza of poetry without feeling that pain, whereas it did not bother me when I was writing prose.

The explanation, I suppose, was that the writing of verse meant a greater demand on me, the concentration of some nerve-centre to a special degree.

There can be no doubt that while it lasts the writing of poetry is a more acute, more exhausting action of the mind than the composition of prose.

I have sometimes spent a night getting a stanza: I do not do so now."

There was a meaning in these last words, and I looked at Mr. Massey and repeated them, waiting for his answer to the implied question.

His answer was a merry twinkle of the eyes, a quiet laugh, a step half across the room and then a story, not a new story, but one which put and illustrated what was in his mind.

"You have heard," he said, "of Jamie Thomson, a lazy

fellow—even though a Scotsman!—who, being found in bed one afternoon at four o'clock and asked why he did not get up, replied 'I hae nae motive.'

I have no motive to write poetry, nor have I had for ever so long.

In England the shoemaker is always expected to stick to his last. People won't allow a man to move from one mental task to another.

You are supposed to stick to what you began with. But that is absurd. I gather that many of Thomas Hardy's admirers are grumbling because he is writing verse instead of continuing his novels.

Why should they? Perhaps Hardy could say of his 'Dynasts,' as I can say of this laborious new book of mine, that I have put more poetry, more of the real spirit of poetry, into it than I wrote in all my verse.

I do not suppose other people will agree with that, not just yet, but may be in a hundred years these pages will begin to have a message, at least I hope so.

It is nearly half a century since I published my study, 'The Secret Drama of Shakespeare's

Sonnets'—a study with a far deeper origin than I could explain in words but that volume is only just beginning, so I judge, to have any effect on men's minds."

Here Mr. Massey travelled into a striking comparison between the poet as such and the man of action.

He was inclined to think that the latter, if he happened also to be a thinker, had the richer nature, for one reason because he was so constantly in touch with humanity.

He instanced Sir George Grey, our greatest Pro-Consul in the higher range of governorship, as being fuller in the human sense than even master poets like Browning or Tennyson could be.

The poet felt a thing vitally and gave it forth in words and there it was, but the rich-natured man of action was constantly feeling, constantly in touch with the throb of life.

It was a very beautiful comparison that Mr. Massey made in subtle, musical language which you needed to hear before you could understand its full meaning.

The end of it was some special words of reminiscence about Tennyson whom he met once, only once, and in London.

"Tennyson," he said, "was one of the first to write me a kindly word about my poetry, and of the lectures which I was wont to deliver on various subjects he wrote, 'If I were in, or near, London, I would come to hear you myself.'

It got to be understood that I was to visit him at his home in the Isle of Wight, but somehow I never did so, and it was not until one occasion when Tennyson came to London to consult his doctor that we did actually meet.

He was not in very good health, the result, in part anyhow, of too much scribbling, and he was in bed when I called.

We had a long talk, among other things on Spiritualism, the essence of which is surely expressed in Tennyson's 'In Memoriam.'

My poem, 'The Tale of Eternity,' is a mere inventory of Spiritualism compared with his 'In Memoriam,' and he certainly spoke as one having no doubt that Spiritualistic phenomena were a reality.

His most striking experience in the course of such 'sittings' as he had tried was the cold wave that he frequently felt pass over his hands.

My talk with Tennyson was very interesting altogether, and I well remember the frank bluntness, almost roughness, of his personality, which did not seem to agree with the Italian suavity of his poetry.

His 'Northern Farmer,' however, was a striking exception to this, for there was a lot of Tennyson, the man, in

it—he had let himself go.

"Oh, yes," Mr. Massey, went on, being himself amused at his reminiscences of those old poetic days, "oh, yes, I suppose I might even have been a poet of society if I had cared.

I might have been supping with duchesses instead of living apart and writing books about the origins of civilisation.

I might have been supping," he repeated, and fell into the nursery jingle:

|

"To bed! To bed!" says Sleepy Head,

"Tarry a while," says Slow;

"Let's have some nuts," says Greedy Guts,

"And sup before we go." |

A man who did his best to help Mr. Massey to sup when he was writing poetry in the middle Victorian days he remembers

gratefully—Mr. Alexander Strahan, the founder of Good Words, who is still happily with us, although the English book-world no longer knows his activities.

"He was," said Mr. Massey, "always willing to help the lame bird, and I was a pretty lame bird at times.

He knew poetry, he liked poetry, and he paid well for poetry. For instance, he gave me £50 for my poem 'The Orphan Family's Christmas.' 'Will you,' he had requested me in so many words, 'write some things for

Good Words? 'I replied that I was getting ten guineas a poem from Charles Dickens and ten guineas a lyric from Cassell's people, to which he immediately replied, 'And we'll pay you ten guineas.'

My first poem in Good Words was one entitled 'Garibaldi,' from which you can gather that it was contributed when that name was taking possession of people's imagination.

I am not sure whether it was to the old Morning Herald or to the

Standard that I once sent a poem which brought me an editorial letter to this effect: 'We like your piece very much, but will you do us something milder on the same lines?'

I am afraid I did not do them anything milder on the same lines."

No; he has never done anything to order—never could,

and never will; for which salutations!

II

It will be seen from the foregoing "unconsidered trifles," as Mr. Massey would call

them—if we could fancy him using so hackneyed a phrase—what a world he turned his back on when he sounded his last post as a poet and took up the studious career of

Egyptologist—Egyptology on a little oatmeal, all leading to the heart of Africa as the cradle of creation.

Yes, it is time to speak of his new book, and how can that be better done than in a short poem, a sonnet it happens to be in form, which he has written in proclamation of its meaning and intention, and as motto for the title-page:

|

It may have been a Million years ago

The light was kindled in the Old Dark Land

With which the illumined Scrolls are all aglow,

That Egypt gave us with her mummied hand:

This was the secret of that subtle smile

Inscrutable upon the Sphinx's face,

Now told from sea to sea, from isle to isle;

The revelation of the Old Dark Race;

Theirs was the wisdom of the Bee and Bird,

Ant, Tortoise, Beaver, working human-wise;

The ancient darkness spake with Egypt's Word;

Hers was the primal message of the skies:

The Heavens are telling nightly of her glory,

And for all time Earth echoes her great story. |

How did the author of that sonnet, which shows how richly the lyric gift remains in him, even if he will not use it; how did he turn from poetry to prose in as grave and serious a form as it could take?

"I was," he said, "seized with evolution, and I began to apply it to the originals in sign language. Ignorance of the primitive sign languages is the source of the greatest errors in theology. The Christian doctrines are a literal misinterpretation of ancient wisdom, and until you get a real knowledge of the sources of things, you are left in error and misapprehension.

You must get down to the rootage, to the primal meanings, and that is what I have been trying to do in what will now be six large volumes from my

pen—volumes in the publication of which I have spent all that I could not spare.

Five-and-twenty years ago a German Egyptologist, Herr Pietschman, wrote

very intelligently and well about my line of inquiry as it had then been

indicated in 'The Book of the Beginning.'" Mr. Massey looked up

that reference because he thought it as illuminating as anything he

could say, and here it is:

"This work belongs to the most advanced reconstruction researches by which it is intended to reduce all language, religion and thought to one definite historical origin; a kind of literature which thrives in Germany, in a manner calling for no such apology as would be necessary in America or England.

The author differs, however, from all similar writers in that he is an evolutionist, holding that he who is not, has not yet begun to think, for lack of a starting point; that black is older than white, whence the black race is first.

It follows that the first is in Africa, and Egypt the birthplace of the original language and

civilisation—the parent home which swarmed from time to time like a beehive.

This view, of which modern theology has not yet dreamed, has not hitherto had any Egyptian research brought to its support.

This the author saw, and saw also that not only must one be an Egyptologist but also an Evolutionist and of the newer theology."

So much for a German welcome for Mr. Gerald Massey, Egyptologist, twenty-five years ago; and that led him to speak to me of the prospects of his coming final volume.

"I think," he said, "I care most about how it will he received in Germany, in Japan and in India, where, I hope, there are many people who will understand.

We are far behind; we have a perverted idea of these things, while the Japanese and the Chinese, say, understand thoroughly.

The Japanese, I take it, are the wisest set of fellows on the earth's surface.

They probably perceive that the existing perversion of theology keeps nations asunder, that it is a stumbling-block to the uniting of the races of the world, and that its doctrines have really much to do with the prevalence of war.

Some Chinese mandarin, who had studied my 'Natural Genesis,' sent me this cap of honour, as I suppose it to

be"—and with that Mr. Massey went and found for my inspection a Chinese biretta, as one might call it, of black cloth with a red topknot.

He popped it on to his head, whose fine shape it showed in clear-cut lines, and then as playfully he took it off and set it down on the table beside him, saying, "I value this tribute, and I suppose the red topknot makes me a notable of some kind."

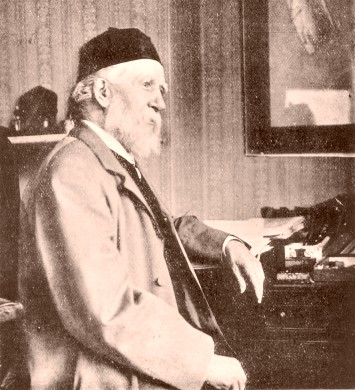

That was the moment to say he must be photographed in it, and he consented, as see our portrait of him.

Yes, it is in Mr. Massey's mind that his new book may be appraised at home in proportion as it comes back piecemeal from

abroad—from Germany or from France, or from Japan. He is content to commend to the ages the truth, as he holds, which waits for recognition in its pages, and he does so again in poetry, his old love, from which all his struggles cannot quite get him away:

|

|

Truth is all-potent with its silent

power

If only whispered, never heard aloud,

But working secretly, almost unseen,

Save in some excommunicated Book;

'Tis as the lightning with its errand

done

Before you hear the thunder. |

|