|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH WATER.

THE IDEA TAKES HOLD

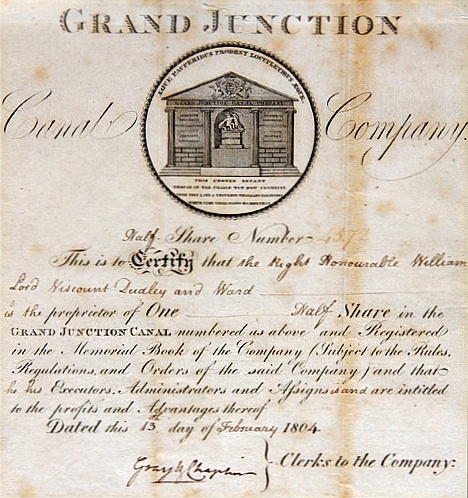

THE COMPANY OF PROPRIETORS OF THE GRAND JUNCTION

CANAL

“This chosen infant though in the cradle yet now promises

upon this land a thousand thousand blessings which in time shall

bring ripeness.”

These words (arranged from Shakespeare) engraved on the corporate seal, summed

up the hopes and aspirations of the Company of Proprietors of the

Grand Junction Canal when their great civil engineering project

commenced in 1793.

The opening of the Oxford Canal in 1790 provided the first major

link for the conveyance of heavy goods between London and the Midlands. Although that canal

prospered, the link that it provided with the Metropolis was, at 154

miles, over long and at times unreliable due to the vagaries of the rivers Cherwell and Thames,

both of which it shares

for part of its length. In addition to its long

and sinuous course, in its upper

reaches the Thames suffered from shallows (shoals) in dry weather and

flooding in times of heavy rainfall. Thus, to satisfy the needs of

commerce, a shorter and more reliable waterway was necessary.

Around 1790, a proposal was made for a more direct route running from Braunston on the Oxford Canal in Northamptonshire to

Brentford on the Thames. This scheme promised to reduce the

journey by 64 miles, while the elimination of the difficult

navigational conditions posed by the Cherwell and the upper Thames added

considerably to its benefits.

In the spring of 1792, the Marquis of Buckingham commissioned James

Barnes of Banbury to undertake a survey. Considering what had to

be done and the state of transport at that time, Barnes performed

the work quickly, for on July 1st, 1792, the Marquis of Buckingham

was able to convene and chair a public meeting at Stony Stratford

Parish Church:

“Yesterday [July 1st, 1792] a meeting was held at

Stony-Stratford, pursuant to public advertisement, to take into

consideration the expediency of forming a Canal from Braunston to

London, & the measures proper to be adopted preparatory to an

application to parliament for that purpose. ― The Meeting, which

was the most numerous ever known upon a like occasion, was held in

the parish-church, as the only place sufficient to accommodate so

large a company. ― The business was opened by the Marquis of

Buckingham (at whose sole expense the survey had been made) and his

Lordship declared, that the active part he had taken in the business

arose from the most disinterested motives, and solely for the

benefit of the tract of country through and near which the proposed

Navigation was intended to pass. ― The question for an application

to Parliament was carried with very little opposition: and the

eagerness with which the subscription was filled, sufficiently

showed the favourable opinion which the country entertained of the

success of the scheme.”

Northampton Mercury,

21st July 1792

Although the Mercury informs us that the Marquis’s motive for floating the scheme

was not solely that of financial gain, in this era of canal mania, with

investors flocking to subscribe to almost every canal scheme then

being put forward, his Lordship probably entertained an expectation

of a handsome return on his investment.

A further meeting was held on 20th July, 1792. According to

the Northampton Mercury it was a “very numerous,

respectable Meeting of Noblemen, Gentleman, Clergy, Tradesmen,

Manufacturers, and Others, holden at the Bull Inn, Stoney Stratford”

under the chairmanship of the astute London banker and Member of

Parliament, William Praed. Among the decisions taken were to apply for an Act of Parliament; to appoint

Messrs Gray (Buckingham) and Acton Chaplin (Aylesbury) as solicitors

and clerks (their names appear on many Company notices in the

following years); appoint Philip Box Treasurer; appoint a Committee;

raise capital of £350,000 in £100 shares, with an immediate call of

£1 per share (to help pay the expense of further surveying and to

apply for an Act of Parliament); and to agree that the Company be incorporated as “The Company of Proprietors of the Grand

Junction Canal”.

Despite Barnes’s successful completion of the Oxford Canal and of his

preliminary survey for the Grand Junction Canal, the scheme’s

investors appears

to have had little confidence in his ability as a canal engineer.

It was decided that he should proceed to the detailed

survey, but the Committee were instructed to obtain the services of an “able

engineer”:

“That Mr. Barnes do immediately prepare a Plan and Section of the

proposed Canal, to be laid before the Committee hereinafter

appointed; and that the said Committee do forthwith engage Mr.

Jessop, or (if he should decline it) some other able Engineer, to

examine and verify the said Plan and Section.”

Northampton Mercury,

28th July, 1792

. . . . and Company papers later reflect the view that:

“. . . the opinion of Mr Barnes was not deemed of sufficient

weight for the company to proceed upon, it was unanimously agreed to

call in Mr. Jessop, who from his experience and abilities was looked

upon as the first Engineer in the kingdom . . .”

Report to the General Assembly, 7th November,

1797

Shares in the fledgling company were soon trading at a considerable

premium . . . .

“At a sale of canal shares in October, 1792, ten shares in the

Grand Junction Canal, of which not a sod was dug, sold for 355

guineas premium; a single share in the same canal for 29 guineas

premium.”

History of the Commerce and Town of Liverpool,

Baines (1852)

――――♦――――

WILLIAM JESSOP’S INITIAL REPORT

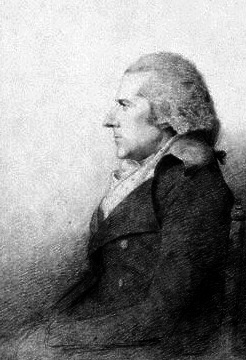

Although weighed down with other work, Jessop accepted the

appointment of Chief Engineer. His first task was to re-survey the route

proposed by Barnes, from which he concluded that:

“I have reason for thinking that MR. BARNES

has explored the Country with much assiduity, and has chosen the

ground with much judgement; in the whole line there are only two

places where I would recommend a deviation, and those are but of

little importance . . . .”

To the Committee of the Subscribers of the Grand

Junction Canal: William Jessop, 14th January 1792

In his report, Jessop addressed three main

questions:

-

the general practicability of the canal;

-

whether the line chosen was the most eligible;

-

whether parts requiring expensive engineering could be avoided.

Overall, he felt that the scheme was practicable, that both the

terminus with the Oxford Canal at Braunston and with the Thames at

Brentford had been judiciously fixed, while the line between these

points was favourable and as free from obstacles as the difficult

nature of the country would permit. The unavoidable

difficulties that did exist and that would require the

construction of either tunnels or deep cuttings lay at Braunston,

Blisworth, Langleybury and Tring.

On the supply of water to the Canal’s two summits at Braunston and

at Tring, Jessop doubted that the natural streams in these

localities would provide sufficient water for any more than “thirty

locks full per day”, sufficient for nothing more than a “moderate

trade”, and if more was required, reservoirs and steam pumping

engines would be needed.

Jessop estimated that the cost of the Canal, together with branches

to Northampton and Daventry, would total some

£400,000. However, he also warned of the risk of wage inflation, for in

that age of ‘canal mania‘, labour was in heavy demand and wage rates

were likely to rise. If they did, even to the extent of

doubling his estimate, Jessop considered that the Canal would

continue to be an “eligible project”.

At the time of Jessop’s report (Appendix) it appears to have been decided

that, unlike ‘narrow’ canals designed to accept

72ft by 7ft narrow boats of 30 tons capacity, the Grand Junction

would be built as a ‘broad canal’ capable of accepting barges with a

14½ft beam and a capacity of 50-70 tons, able to “navigate with

safety on the Thames”. Although the plan to use barges extensively came to nothing, [1] the wide

locks that had been built to accommodate them did ease congestion in

the Canal’s commercial heyday, for they could accommodate a pair of

narrow boats abreast, as would its two tunnels. This advantage

continues to the present day in handling the Canal’s increasing

weight of leisure traffic.

――――♦――――

COMPETING SCHEMES

The prospective Grand Junction Canal stood to make a serious inroad

into the Oxford Canal Company’s revenue. In recognising that

their route from the Midlands to London via the Thames was likely to

be bypassed, the Oxford Canal Company put forward a competing

scheme.

In 1792, Samuel Simcock and Samuel Weston surveyed a route from

Hampton Gay on the Oxford Canal (six miles north of Oxford) to Long Crendon and Aylesbury, then crossing the Chilterns through the

Wendover Gap to reach Amersham, Uxbridge and a terminus at

Marylebone. Also included was a branch from Uxbridge to the

Thames at Isleworth. The proposed scheme, for what was to be

called the ‘London and Western Canal’ ― usually referred to as the

‘Hampton Gay Canal’ ― was announced in the official newspaper [2]

together with a second proposal, which appears to have been designed

as a compromise. This scheme was for a canal starting in the

parish of St. Giles in Oxford, then following a line via Long

Crendon, Aylesbury and Aston Clinton to Marsworth . . . .

“. . . . in order to meet and form a junction there with a canal

now in Contemplation and intended to be made from and out of the

Oxford Canal within the Parish or Township of Braunston . . . . unto

or near the Town of Brentford . . . .”

The London Gazette, 15th

September, 1792

The intention was that each company would build its own connection

to Marsworth, from where the remainder of the route to Brantford

would be over a jointly-owned canal. But the Grand Junction

promoters had powerful allies among the nobility and saw no reason

to accept a compromise. The St. Giles scheme then disappears

but the Hampton Gay project did go before Parliament in 1793, its

engineer, Samuel Simcock, giving evidence on its behalf. But

the scheme failed leaving the field clear for the promoters of the

Grand Junction Canal. In passing, it is worth mentioning that

Aylesbury was to be bypassed by several canal schemes during the

next thirty-five years, the Aylesbury Arm being all that was

achieved of a grander scheme to build a 36½ mile canal linking the

Grand Junction Canal at Marsworth, via Thame, to the Wilts & Berks

Canal at Abingdon, the River Thames being crossed on an aqueduct.

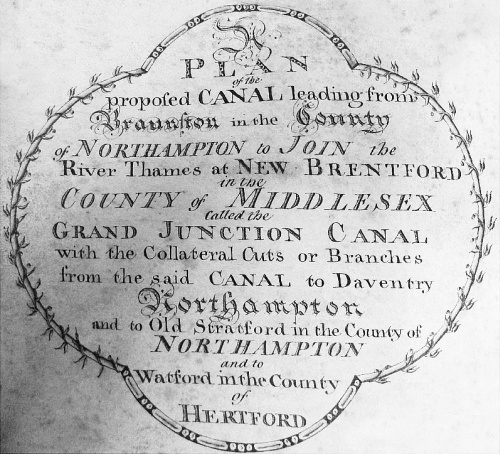

Title on the deposited plan of the route.

――――♦――――

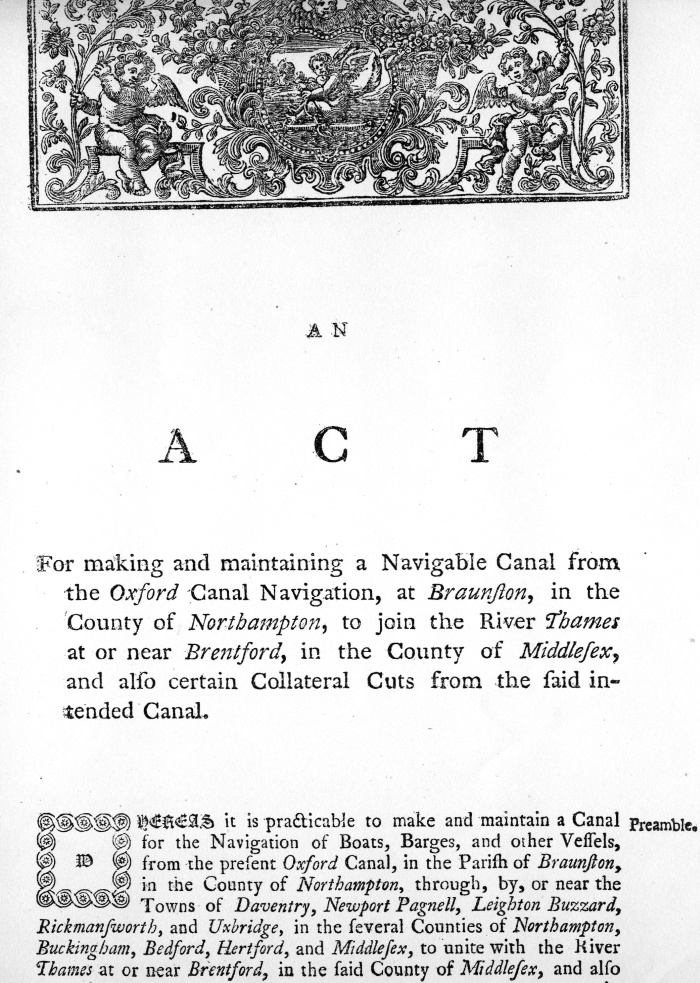

THE 1793 ACT OF PARLIAMENT

At the meeting held at Stony Stratford on 20th July 1792, a

decision was taken to apply for a canal Act as soon as possible. The

principal sponsors of the Bill that was laid before Parliament

included a number of eminent aristocrats. . . .

Francis Egerton, Duke of Bridgewater

George Grenville Nugent, Marquis of Buckingham

Rt. Hon, Philip Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield

Rt. Hon.William Ann Holles Capel, Earl of Essex

Rt. Hon. George Fermor, Earl of Pomfret

Rt. Hon. Thomas Villiers, Earl of Clarendon |

This weight of blue-blooded support eased the Bill’s passage through

Parliament, and the first Grand Junction Canal Act received the

Royal Assent on 30th April 1793:

Title page of the Grand Junction Canal Act, 1793.

The Act authorised the “Company of Proprietors of the Grand

Junction Canal” to raise capital of up to £600,000 to fund construction of

the main line of the Canal from a point where the eastern branch of the River

Brent enters the Thames at Syon House near Brentford, to the Oxford

Canal at Braunston. It also authorised branches to Daventry,

the River Nene at Northampton, to the turnpike road (now the A5) at

Old Stratford, and to Watford: the branches to Daventry and Watford

were not built, although at the time of writing (2012) that to Daventry might.

Some of the caveats in the Act are interesting in that they

illustrate objections on which the Proprietors were

obliged to concede during the committee

stage of their Bill:

-

the tow path was to be on the far bank of certain estates

including Osterley Park by which the canal passed (presumably to

prevent boatmen entering the pleasure grounds of their owners)

and it was not to take water from those domains;

-

to ensure supplies to the owners of watermills, reservoirs were

to be built to maintain the levels of the Rivers Bulbourne, Gade,

Colne and Brent (the first two were never built, which later led

to expensive litigation with the paper manufacturer, John

Dickinson);

-

that certain wharf and warehouse owners from the Thames to Bax’s

Mill were to be given toll-free use of the canal;

-

and that a stated minimum level of revenue was to be guaranteed

by the Grand Junction Canal Company to the Oxford Canal Company

as compensation for their loss of trade to the new canal. [3]

The

Government also received toll-free use of the canal for certain

purposes including the movement of troops and military equipment;

indeed, in the era preceding the railways, the newspapers of the

time frequently report on bodies of troops being moved in this way.

Thus the Act stated that:

“Officers and Soldiers on march, their Horses, Arms and Baggage,

Timber for his Majesty’s Service, and the Persons having Care

thereof; Stores for ditto, on Production of Certificate for the Navy

Board or Ordnance. Also Gravel, Sand, and other Materials for

making or repairing any Public Roads, and Manure for Land, if the

same do not pass any Lock.”

Other Acts were obtained in the following years for various purposes

including, in 1794, authorisation to construct the branches from

Marsworth to Aylesbury, from Old Stratford to Buckingham, and from

Bulbourne to Wendover (the latter replacing the planned water supply

channel with a navigable canal); in 1795, to improve

the Canal’s route in the vicinity of Abbot’s Langley; also in 1795,

to construct a branch from Norwood to Paddington; and in 1801 and

1804 to raise further capital.

On 3rd June 1793, William Jessop was appointed Chief Engineer, at a

fee of 7 guineas a day, to take overall charge of construction,

while James Barnes was appointed Resident Engineer at a rate of two

guineas per day plus half a guinea expenses.

The private Act having been obtained, work was begun almost

immediately from both ends and on the problem areas, these being the

tunnels at Braunston and Blisworth and the long cutting at Tring ―

the long embankment and aqueduct across the Valley of the Great Ouse

(between Wolverton and Cosgrove) was a later addition to the

original plan.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

To the Committee of the Subscribers to the

Grand Junction Canal

GENTLEMEN,

I HAVE apprehended that the intention of the

Survey which I have lately made, in consequence of your doing me the

honour of asking my opinion, comprehends the following heads of

enquiry.

FIRST, The general Practicability?

SECONDLY, Whether the Line that

has been chosen is in general the most eligible?

THIRDLY, Whether such parts as

will be particularly expensive could be avoided? |

On the first head, I have no hesitation in saying that I can have no

doubt of the practicability.

On the second head, two leading objects are kept in view. FIRST,

that the points of commencement and termination should be such as

best suit the intention of good communication, between extensive

Inland Navigation in the North and the Port of London.

AND SECONDLY,

that the line of communication should be as direct as it might

conveniently be made.

If the Country were favourable to a junction with the Oxford Canal

at any more southerly point than Braunston, it would be

objectionable on account of the circuity of that Canal, and the

consequent increase in distance; and I believe that it would not be

practicable to have a more northerly junction.

For the same reason it would be unadvisable to join the Thames at

any higher point of that River than New Brentford; and to fall lower

into the Thames, would, if practicable, be at least very difficult

and expensive.

The terminating points being this fixed, I had little expectation of

discovering a shorter line between these points than the line

pointed out by MR. BARNES;

indeed I was rather astonished at finding in passing through so

great an extent of country, intersected in various directions by

Hills and Valleys, and where there was every appearance (if a line

could be found) that at least it would be unusually circuitous) that

is not more than 15 Miles longer than the distance by road.

The only obstacles which materially enhance the expense are the high

grounds at Braunston, Blisworth, Langley Bury, and Tring; and I

believe those are unavoidable from the enquiries which I have made,

where other passes seemed to invite attention: I have reason for

thinking that Mr. BARNES has explored the Country with much

assiduity, and has chosen his ground with much judgement; in the

whole line there are only two places where I could recommend a

deviation, and those are but of little importance; one is, the

cutting off a bend near Leighton Buzzard, if entering the County of

Bedford is not an objection, and the notices have comprehended it;

the other is, that the Entrance into the Thames should be at a point

where the River Brent now discharges itself, instead of the point

where the Plan now describes the junction higher up the River.

I have estimated the expense on the supposition that the width of

the Canal should be 28 feet at the bottom, 42 feet at the water’s

surface, and the depth of water 4 f. 6 in.

The Locks I have supposed to be 14 f. 6 in. in width, and 80 feet in

length in the Chambers;—those will admit Boats that will carry from

50 to 70 Tons, and such as will navigate with safety on the Thames,

on the Trent if the communication should take place with the

navigation at Leicester, and on the Mersey if the present Canals

should hereafter be widened, which is not improbable.

The Tunnels I should propose to be 16 feet in width, 18 feet in

height, and to have at least 6 feet depth of water.

Locks of the above width will contain two of the boats which now use

the narrow Canals, and those boats may now pass each other in the

Tunnels.

Respecting the supplies of water, it is to be observed that, as

there must be two summits, the quantity consumed will be more than

one would require, but not so much more as some might suppose: the

loss by exhalation and absorption cannot be at all increased by this

circumstance, they are only such Vessels as pass both Summits that

will require a double quantity of water; the lower levels may be

amply supplied, it is the supply for the Summit only that is

questionable.

The wetness of the season would have made any actual Admeasurements

of mine useless, in ascertaining the supply for dry Seasons; but in

examining Mr. BARNES’S

admeasurements I have very little doubt of the natural Streams, that

may easily be brought to the Summits, affording a sufficient supply

for a modest trade; his admeasurements were not taken in a very dry

season, but I found he had made a considerable allowance for this

circumstance, and with this allowance he found that 30 locks full

per day would flow into the Summit at Braunston, and if this should

not hereafter be found sufficient, a considerable addition might be

made by the means of a Reservoir for collecting and preserving Flood

Waters.

|

|

|

William Jessop,

civil engineer. |

To the Summit at Tring he found that from Bulbourne Spring and the

Tail at New Mill 30 locks full per day might be obtained, ― some

might be collected by a Reservoir in this case also, but not much to

be depended on: In Clay Soil such as at Braunston, the extremes of

wet and dry Seasons differ as much as One Thousand to One: In Chalky

and Gravelly Soils the difference is seldom more than Four to One,

for in the former case heavy rains produce great floods, and little

is absorbed; — in the latter case there are seldom any floods, for

almost the whole is absorbed, and it only operates for a while to

increase the supply by the Springs, which may be considered as the

discharges of natural Reservoirs, dispensing frugally for many

Months what would be washed from the surface of Clayey Soil in a few

days.

But if the supply that may be brought into this Summit should

hereafter be found to be insufficient, and particularly if the

proposed Canal to Oxford should demand much additional supply, any

quantity may be got from Streams at a lower level by means of a

Steam Engine, so that in any case I considered that the

practicability of getting Water sufficient is beyond a doubt.

In estimating the expense in making the Canal, I have thought it

necessary to make very large allowances for the increased and

increasing price of Labour, in consequence of the numerous works of

this kind now in agitation, and I have full confidence that the

expense will not exceed the estimate. While I say so, I am of

opinion, that if the expense were to be doubled it would be an

eligible project, and productive of more public benefit than any

thing of the kind that has yet been done in this kingdom: without

enumerating particulars, it is sufficient to say, that the three

great circumstances, viz. making a direct communication with the

Great Northern Manufactories and the Port of London;—the supplying

Coal at a cheap rate to the Inland Counties where that article is

extremely expensive; and the carrying provisions of all kinds to the

Metropolis, where the consumption is almost unbounded, must banish

all doubt (if any there should be) from the minds of those who have

had an opportunity of observing the effect produced by Canals

already existing; in situations where the objects are much more

limited.

As it has been a question, whether from the point called Two Waters

the course of the Canal would be the most advisable by Watford or by

Uxbridge, I viewed both the lines, and found there were many reasons

for preferring the latter direction. As the Committee are

already in possession of circumstances sufficient to determine their

opinion, it is unnecessary for me to state them.

Four branches, if found eligible, may be adopted and made and made

part of the present Plan; One from Daventry,—One from Northampton to

join the line at Gayton,—One from Stoney Stratford, and One from

Watford; and I have little doubt but that many hereafter will

contribute to expand its benefits. As the Surveys of the two

last-mentioned Branches are not yet complete, I cannot particularly

describe them nor specify the Expense:—I can say that they are

practicable, and I think very advisable.

The Branch at Daventry will be near a Mile and an half in length,

and must have about eight Locks, as the fall is 52 feet—The Costs of

it will be at least £6,000. As Daventry is about three Miles

from Braunston, if such branch could not be made, no Coal could pass

on the main Canal to Daventry. Whether the trade of Daventry

will be such as to pay for the expense of this Branch, either its

quantity, or from its being able to bear a high Tonnage, I am unable

to judge.

The Branch from Gayton to Northampton will be 4½ Miles in length,

and the fall will be 117 feet—the expense of it will be £18,785.

It might be doubtful whether as a Branch to Northampton only, the

trade on it would answer this expense, but as the proposed

communication with Leicestershire will probably bring a very

considerable trade through it, I would submit to the Committee that

they may with propriety adopt it.

W. JESSOP

Northampton, October

24th, 1792. |