|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH WATER.

THE CONSTRUCTION PROJECT

BACKGROUND

“The canals which intersect Middlesex are the Grand Junction

Canal, and the Paddington Canal. The former striking off from

the Thames at Old Brentford, passes the grounds at Sion Hill and

Osterley; and, running through a rich corn district near Hanwell,

Norwood, Harlington, West Drayton, Cowley, Uxbridge, and Harefield,

leaves this county near Rickmansworth. This canal, which is

navigable for vessels of sixty or seventy tons burthen, has fourteen

locks to Harefield Moor, where the level is 114 feet two inches

above that of the river Thames. From its numerous cuts, side

branches, and collateral streams, it is, beyond doubt, the most

important inland navigation in the kingdom, as it affords a direct

water communication to all the various manufacturing towns of

Warwickshire, Staffordshire, Lancashire, Derbyshire, and several

other counties. The general breadth of this canal is thirty

feet, but at the bridges it is contracted to fifteen. The

Paddington Canal branches off from it near Cranford, and is

continued on a level from thence to the dock at Paddington, the

sides of which are occupied with yards and warehouses, for the

reception and security of merchandise. The advantages derived

to the metropolis and the country at large from this canal are

likewise various and important. A third canal, called the

Regent’s Canal, stretching from the Thames, west of London, to join

that river near Limehouse, has been lately projected, and is now

carrying into execution.”

Encyclopaedia Londinensis,

Vol. XV. John Wilkes (1817)

Today, it is difficult to image the areas of Hanwell, Norwood and

Harlington, etc., being rich corn districts, or for that matter Paddington

Basin being occupied by yards and warehouses ― one warehouse

survives, although put to a different use ― but such was the landscape

through which the new canal passed and which it served.

Completed in 1805, until surpassed in 1887 by the Manchester Ship

Canal the Grand Junction was Britain’s most

expensive canal project. Originally estimated at £400,000, its eventual cost was in the region of £1,500,000. [1]

Cost overruns are not unusual in complex construction projects.

In our own age the

British Library, the Millennium Dome, the Scottish Parliament, the

Edinburgh Tramway and the Channel Tunnel are examples of

construction projects

that have significantly exceeded budget. Even the Manchester

Ship Canal, at £15,000,000, was almost three times over budget and

two years late in opening. Each of these projects attracted

much concern among its investors, as did the

Grand Junction Canal.

This chapter draws mainly on contemporary sources to provide

a feel for the financial and engineering difficulties that beset

this 18th Century ― to use today’s terminology ― ‘transport

infrastructure project’.

――――♦――――

1792 ― QUESTIONS STILL TO RESOLVE

“It was in the year 1792 that this undertaking first had its

origin. In the beginning of that year the Marquis of

Buckingham instructed Mr. Barnes, the eminent engineer, to make a

survey of the country between Braunston, in Northamptonshire, the

place where the Oxford Canal has its junction with the present

canal, and the Thames near London, in order to mark out a line of

canal, whereby the circuitous course of the Thames Navigation from

Oxford might be avoided, and the transit of goods to the metropolis

accelerated.”

Navigable Rivers and Canals,

Joseph Priestley (1831)

When Barnes completed his survey in 1792, questions still to resolve were the line

that the Canal should follow south

of Two Waters (Hemel Hempstead) and the location of water sufficient

to supply the Tring summit. Some

of the Grand Junction Canal Company’s earliest published circulars

address theses issues.

One of the first recorded shareholder meetings, [2]

convened by the Earls of Essex and Clarendon, took place at the

Essex Arms, Watford, on 20th October, 1792. The main business

of the

meeting was to consider the plan of the Canal and decide whether it

should reach Southall through Watford and Harrow, or take a longer but more favourable line along the Gade and Colne

valleys through Rickmansworth and Uxbridge. Having inspected both

routes, Jessop favoured the

latter and supported by Barnes recommended accordingly. The

Rickmansworth route being accepted, the meeting went on to vote in

favour of a short branch to link Watford to the main line, which, on

account of their first decision, now

bypassed the town. On the following day the Rickmansworth route was

again approved, this time at a meeting chaired by William Praed and held at the County Hall,

Northampton. Jessop

reported to the Committee that there were many reasons for

preferring the Rickmansworth route. These are unrecorded, but it is

likely that a sufficiency of water was prominent among them.

Although water supply was an issue that affected the entire Canal,

supplying the Tring summit was to prove particularly challenging. Writing in

1805, the civil engineer Thomas Telford, who had recently inspected the

Canal, referred to water supply in the

introduction to his report:

“. . . . the Line of Canal has unavoidably been carried over a

country, in many points of view unfavourable for Canal operations.

The line of the canal passes over and skirts along some of the

highest ground in the central parts of England . . . . this

circumstance has subjected the canal to the inconvenience of two

summits, and has rendered the supplies of water more difficult to be

procured than when canals are carried upon lower levels, or are

connected with more mountainous countries. . . .”

Supplying the Tring summit with water appears not to have been

investigated thoroughly at the outset, suggesting that the level of

traffic that built up following the Canal’s opening was

greater than anticipated. In his report to the Committee of 24th October

1792, Jessop expressed the opinion that the flow from Bulbourne

Spring together with that from the “Tale at New Mill” (Tring Brook)

would, between them, supply 30 lockfuls a day and that any

deficiency could be made up by steam pumping from a reservoir,

although none had then been planned; some

ten years were to elapse before the first of the Tring Reservoirs

was opened at Wilstone. [3] Another important water resource is the Wendover Stream; diverting its

abundant supply to the Tring summit appears not to have been

contemplated at this stage, for Jessop makes no mention of it and

neither is the supply channel (later to become the 6¾-mile Wendover

Arm) shown in the deposited plans.

In retrospect, Jessop’s opinion that “the

practicality of getting water sufficient is beyond doubt” proved over-optimistic,

for despite the resources that have been applied down the years to

flooding the Tring summit, water shortage has continued to pose a

problem. At the time of writing, the Tring summit was last

closed through water shortage in February and March 2012 ― this was inconvenient,

but during the Canal’s commercial heyday drought could seriously hinder the

passage of trade (and canal families’ piecework income):

“Between Marsworth and Boxmoor, on the important canal which

connects London with Braunston and Leicester, there are 50 pairs of

barges waiting for water to float them through the locks. This

block is the worst effect of the drought in Hertfordshire and

Buckinghamshire. It is causing serious delays in the London

supply of all kinds of merchandise — coal and ironware from the

Midlands, new corn from some of the arable counties, condensed milk

from Aylesbury — and in the Midlands supply of sugar, tea and other

commodities in bulk from London. Heroic exertions on the part

of the Grand Junction company’s engineers and servants do not enable

more than 80 to 90 barges a week to pass over Tring Summit, whereas

in times of plentiful water 130 pass.”

Bucks Herald, 11th October, 1902.

Telford also identified in his survey a number of sections where the water

that had been procured was being wasted through leakage. One example

that he gave was to the south of the Tring summit:

“it will be chiefly in the upper part of the line in this

district, that is, between Cow Roast and Box Moor, that much

attention and expense will be required, in order to prevent

leakage.”

In fact it was along the section of the Canal to the south of Boxmoor where leakage was later to bring the Company into conflict

with the local water millers, a conflict in which Telford was to

become involved.

――――♦――――

1793 – WORK COMMENCES

Following the passage of the first Grand Junction Canal Act (30th

April, 1793), construction began promptly. By December of that

year the Committee was able to report that “the works on the

Grand Junction Canal are proceeding with an astonishing rapidity,

and the number of men now daily employed amounts to 3,500”. However, their report goes on to say that expenditure was greater

than anticipated and it reminded subscribers to settle promptly the

calls on their partly paid shares. This was an early indication of

the cost overruns that were to affect the project and that required

recourse to Parliament on several occasions for authority to raise

additional capital. Jessop had already informed the Committee that

his construction estimate included an allowance for the inflationary

pressure on wages from competing canal projects (this was the period

of canal mania):

“I have thought it necessary to make very large allowances for

the increase and increasing price of labour, in consequence of the

numerous works of this kind now in agitation, and I have full

confidence that the expense will not exceed the estimate.”

Report to the Committee,

24th October, 1792 – William Jessop

But what Jessop could not have allowed for was the additional

inflationary pressure of the French Wars (1793-1815) together with the

cost of function creep [4] that so often affects major

projects. He did, however, inform the Committee that even if

the project was completed at twice his estimated cost, it would

still be worth doing.

――――♦――――

1794 – WORK PROGRESSES

By May 1794, Jessop was able to report good overall progress.

The canal from Brentford to Uxbridge was almost complete and he

expected it to open by late September, although shortage of

labourers [5] during harvest-time was a problem, which probably

accounts for this section being opened (with the usual celebrations)

rather later than Jessop had estimated:

“That part of the Grand Junction Canal from the river Thames,

near Brentford, to the town of Uxbridge, was opened on the 3rd

instant, for coals, and all sorts of merchandize to be navigated

thereon; comprising upwards of twelve miles of this great

undertaking. The opening of this part of the Canal was

celebrated by a variety of mercantile persons of Brentford,

Uxbridge, and Rickmansworth, and their vicinities, forming a large

party, attended by a band of music, with flags and streamers, and

several pieces of cannon, in a pleasure-boat belonging to the

Corporation of the city of London, preceding several Barges laden

with Timber, Coals, and other merchandize, to Uxbridge. After

which the party dined at the White Horse Inn.”

Northampton Mercury,

15th November, 1794

Work was also progressing on the northerly of the Canal’s two

summits at Braunston. The Braunston summit was one of the early

points of attack, work commencing there in May of the previous year:

“One part of the Braunston canal, which is to form the Grand

Junction, was begun last week with great spirit. Three hundred

and seventy men were paid on Saturday night, and more hands are

arriving every day. Another part will shortly be set about by

Mr. Clifton, with his new machine for saving three fourths of manual

labour, in cutting and removing earth, &c.”

Northampton Mercury, 25th May, 1793

It is doubtful if Mr. Clifton’s “new machine” was a success,

for there is no further mention of it.

The summit level is just over 3 miles long (comparable to that at

Tring), 2,042 yards of which passes through the Braunston tunnel, which

Telford later described as “being in a tolerably straight direction”,

a reference to the slight S-bend in its alignment. Because the

ground in the vicinity was impervious clay rather than absorbent chalk, water supply

was not to be the challenge that it was at the Tring summit.

The 1793 Act also authorised the construction of a 1½-mile branch

from the summit to Daventry. Jessop estimated that it would require eight locks to cope

with the 52 feet difference in levels and cost £6,000 to build, but

he could offer no opinion as to the branch’s commercial viability.

Because of its falling gradient from the town, the Daventry branch

would have supplied the summit with water,

but although its position is shown in the Canal’s deposited plans it

was not

built. [6] Instead, the Braunston summit is supplied

with water by what Telford later described as “small

rills on the Braunston side of the summit” and by a

feeder channel from Watford Park, which joins the summit near Welton. These feeders worked in

conjunction with a small reservoir (which no longer exists) near the northern end of

Braunston Tunnel and the much larger

Drayton Reservoir, opened in

1796, which lies to the north west of Daventry.

In his report, Jessop expressed reservations about the quality of

the bricks being made for Braunston Tunnel [7] and

the quantity; “as is commonly the case at the outset of

brick-making, they [the brick-makers] want flogging to their

duty”. A section of canal to the east of the tunnel had been flooded and

was being used to transport bricks. Work on the cuttings was

progressing well, as were the high embankments at Weedon, Heyford

and Bugbrook (the great embankment between Wolverton and Cosgrove was a late addition

to the original plan). Work had also begun on the Blisworth Tunnel, but

too little had been done to give any indication of the setbacks yet

to come. The Wendover Arm was by now seven-eights complete (so

was probably complete by the end of 1794); here, Jessop

draws attention to the “very leaky” terrain over which it was

being built, a portent for the future.

Jessop also refers to progress on the Tring cutting (“The Deep

Cutting at Marsworth”), where the ground along the line had been cut

to an average depth of five feet, sufficient to make Jessop hopeful

“that this heavy piece of work will be executed at an expense

considerable less than was first expected” ― it was not to be.

|

|

Tring Cutting,

looking north from Marshcroft Lane bridge (No. 134).

|

――――♦――――

1795 – PROJECT CONCERNS

By August, 1795, the Committee was becoming concerned about escalating

costs. To date, the value of work on the Canal amounted to £296,000

and Jessop estimated that a further £312,000 was needed to complete

construction, of which monies owing and assets in hand amounted to

£177,000, leaving a deficit of £135,000.

In explaining the position to their shareholders, the Committee

pointed to a number of unforeseen expenses, some of which had been

imposed by Parliament, such as a change in the method by which the

canal banks were formed (£17,000) and an additional duty on bricks

(£7,200). Other items included the purchase of water mills (to

obtain their water rights, £10,500), construction of reservoirs

(£7,000) and an alteration to the line of the Canal to pass through Cassiobury and Grove Parks (£9,000),

this being offset by Parliament authorising an additional levy of

two-pence per ton “for and in

consideration of the more constant, speedy, and safe communication

proposed by the said deviation”. [8] The

Cassiobury/Grove Park deviation brought the Canal closer to Watford

― to which a branch was then planned ― and despite the high cost of

the land, it probably cost little more to build than

the original route, which would have required an aqueduct across the

Bulbourne and a tunnel at Langleybury.

In addition to the financial impacts of changes and additions to

specification and the inflationary pressures of the age, land was

also proving more expensive than anticipated:

“The price of materials, the expense of carriage and provender

for horses, have been much enhanced; and the dearness of provisions

has greatly enhanced the price of labour. And the price which hath

been paid for the land purchased (in general) much higher than the

same had been calculated upon. Before beginning the work, Mr Jessop

found it advisable to make the locks something larger than they were

first intended, and to make the tunnels something wider and higher;

the canal has also been made five feet in depth, instead of four

feet six inches, as computed in the original estimate.”

GJCC

Statement of Expenditure, 6th August, 1795

A further expense to find its way into the report was “the

payment of interest to Proprietors out of capital stock”.

During this stage of the Canal’s construction, shareholder received

5% p.a. interest

payable on the nominal value of their shareholding, with interest

payments being funded mostly from capital due to the Canal’s very

limited earnings at this stage. The Company projected that between midsummer 1794 and March 1798,

interest payments to subscribers, if continued, would account for

£75,000 and that suspending them was “a measure highly expedient”. In the event, the Committee decided to credit subscribers’ accounts

with the interest owing, but to suspend payment until directed by a

future General Meeting.

And so began the process of finding ways and means of financing the

Canal’s construction, which were to continue for the remainder of

the project. This involved containing costs ― even Jessop’s role as Chief

Engineer was eventually dispensed with (ostensibly) as a cost-cutting measure

― increasing tolls, raising further capital by selling shares, and

raising loans, much of which required the authority of further Acts

of Parliament. These measures commenced later that year with an

application to Parliament to raise a further £225,000 of share

capital. [9]

――――♦――――

1797 – ESCALATING COSTS

|

|

|

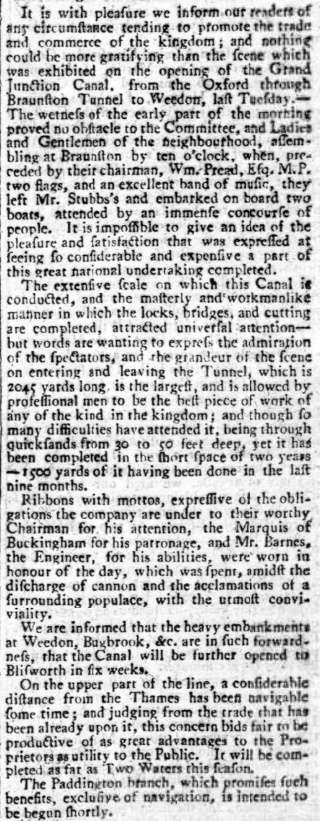

Northampton Mercury, 5th June, 1796. |

Every major construction project has its critics and that

to build the Grand Junction Canal was no exception. In 1797, a long pamphlet appeared

entitled “Observations on the present state of the Grand Junction

Canal, submitted to the Attention and Consideration of the

Proprietors”. In it, numerous allegations were laid against the

Committee implying mismanagement and incompetence. The author cited,

as evidence, the heavy overspend on budget, money wasted on wharfs

and tunnels (most notably on the Blisworth Tunnel, which was by then in limbo) and the heavy expense of building the Tring

cutting. Overall, the pamphleteer considered the Committee to be “inert

and inexperienced”, pointing to declining investor confidence

and the fall in share price from a £90 premium to £30 to support

that view. To make the best of a bad job, the writer recommended

that the Canal’s “upper [southern] end ought to stop, and the lower end

prosecuted as far as the inland coal trade would extend”.

The pamphleteer’s allegations probably contained sufficient germs of

truth to encourage the Committee to mount a vigorous defence. At the

General Assembly held on 7th November 1797, it was resolved to

publish a rebuttal of the main allegations, preceding which the

Committee assured their shareholders that they had “conducted the

affairs of this Company with the strictest zeal and integrity”. In their response, the Committee gave credence to the charge that

costs were continuing to exceed budget. Again, they were at pains to

attribute overruns to additions to their original plan (some of

which had been heard before), such as the need for the Aldenham

Reservoir, [10] for aqueducts across the Colne and

a change in the line at Harlington, while other unexpected costs

stemmed from additional linings for the Canal, clearing the

Braunston Tunnel workings of quicksand “which from the borings

there was no reason to expect”, and “widening and deepening

the canal beyond the original design, and the consequent increase of

expense in the width of every bridge”. [11]

The inflationary pressures of the French Wars were also

beginning to bite, with military needs competing for scarce manpower

and manufacturing resources. As the Company explained, procurement was

being affected by “the difference of the War price for all labour

and materials, when compared with the sums estimated for them in

profound peace”. But on the bright side, the Committee

report

that work on the Tring cutting and on short sections to the north

and south of it were nearing completion, and that even in its

unfinished state the Canal would soon generate revenue estimated at

£20,000 p.a.

A section of the Committee’s response also provides an interesting

explanation of the sequence in which the various sections of the

Canal were built. In addition to the commercial considerations ―

i.e. what sections were likely to generate the most

revenue soonest ― there was the perennial problem of water

supply to contend with, for an insufficiently flooded canal is near

to, or completely useless. In explaining why work on the section

south of Blisworth tunnel should not yet go ahead, the Committee

pointed out that not only were twelve locks required to take the

Canal down to Cosgrove, but until the Blisworth tunnel was completed

there would be insufficient water to flood them. A section near

Stony Stratford, about five miles in length, could have been

completed but there was no commercial sense in so doing, while the section from Cosgrove up to Fenny Stratford

could not be flooded until it had been reached by the Canal

bringing water down from Tring.

――――♦――――

BARNES REPORTS ON PROGRESS

The Committee supplemented their rebuttal of the mischievous

pamphlet with a report [12]

from Barnes on the present state of construction. This is

revealing. To the south, the Canal was

now open to Kings Langley and would shortly reach Two Waters (Hemel

Hempstead), but Barnes then moves on to reflect on “the great

difficulties, delays and impediments” to construction being caused

by “the immense quantity of water springing from the earth at the

locks”, while the porous ground over which the Canal was being

built in the vicinity of the Nash and Apsley paper mills required

it to be lined. In later years, leakage along this section was

to result not only in the Company paying heavy damages

to the paper manufacturer John Dickinson, whose water mills had suffered

in consequence, but in an alteration to the route followed by the

main line. North of Two Waters, work had begun cutting the

section up to the Tring summit and much building material (bricks

and timber) had been deposited along the route in readiness. Barnes

was optimistic that the ground over which this section was to pass

would prove favourable.

Work had commenced at the outset on the Tring summit due to the

heavy excavation required, about half of its 3-mile length being

in a cutting some 30ft deep in places. Although the Wendover Arm

seems not to have featured in the original planning (1792), its

importance in diverting the Wendover Stream 6¾-miles along the 394ft

contour to the Tring summit must soon have been recognised. The

Arm was probably complete by the end of 1794, but in any event well before the

southern section of the Canal reached the Tring summit

early in 1799.

In his report, Barnes informed the Committee that work excavating

the Tring cutting was progressing well, but two problems had been

encountered. A section of about 500yds was found to be extremely

waterlogged, causing slippages in the adjacent walls of the cutting. These required drainage headings to be driven into the banks behind

the slips to lead off what Barnes describes as “a great quantity

of water”. Further south along the summit, a section of the

Canal passed over ground that was found to contain gravel and was

porous. This Barnes planned to deal with using the earth from the

slips, which was found to be suitable for lining and which, he says,

“I intend taking away with barges”, implying that by this

date part of the summit was already flooded.

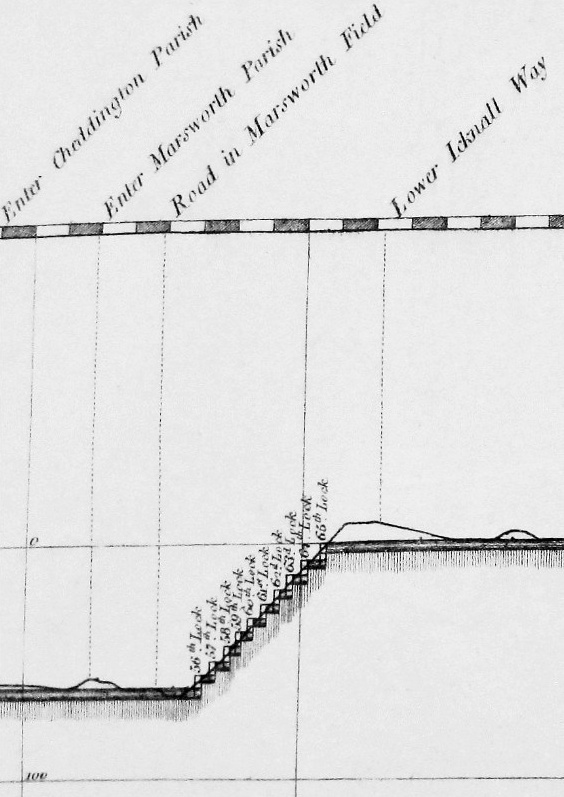

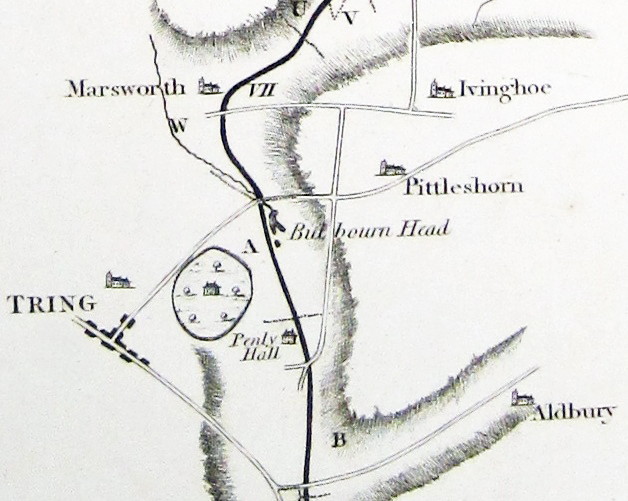

At the northern end of the summit, the deposited plans show a

rather different route was intended from that eventually taken. The

Canal plan and section show the summit pound continuing

northwards along the contour from a location in the vicinity of Marsworth top

lock (No. 45) to a point about ¼-mile to the north of Lower Icknield

Way. From here, the Canal was to descend via a closely spaced flight

of ten locks [13] to the east of Marsworth Parish

Church to join the present route. However, the Canal as constructed follows a

line to the west of Marsworth Parish Church, descending the incline

from Bulbourne along the course of the northern outflow of Bulbourne

Head (or Bulbourne Water) via the flight of seven locks

seen today. The

Tring summit pound is thus about ½-mile shorter than originally

planned, but why this change was made is unknown.

|

Section and plan showing the

variation in the course of the Tring summit at its northern end.

The Canal, as built, passes to

the west of

Marsworth Parish Church,

not to the east as shown, commencing its descent from the summit

well to the south of Lower Icknield Way. |

North of the Tring summit, Barnes

believed the ground to be “upon trial, exceedingly favourable”

stating that he expected the cost of the Canal per mile would be

comparable to that of the section between Uxbridge and Two Waters. Work had already begun in the vicinity of Marsworth and Cheddington,

where Barnes reported finding plenty of

good clay for brick-making, and he was optimistic that the section

to Fenny Stratford would be completed at the same time as the Tring

summit was reached from the south. He then moves on to report

progress on the problematic Blisworth Tunnel.

The Blisworth tunnel was recognised to be one of Grand Junction

Canal’s three major engineering challenges, [14]

construction having commenced in 1793. Trial boring along the line

of the tunnel from the hill above failed to reveal that the strata

through which the tunnel was to pass dipped in the centre. The

effect of this was to cause the horizontal tunnel to move out of a

layer of impermeable clay and into one of porous, unstable rock

which, together with the layer of impermeable clay beneath it,

formed a subterranean reservoir.

By the end of 1795 the tunnel had moved into this water-bearing

stratum, resulting in such severe flooding in the workings

that excavation came to a virtual standstill. The Committee was then

faced with the decision of whether to restart the tunnel on a

different alignment, the option favoured by Barnes, or take the

Canal over Blisworth Hill using a system of locks, reservoirs and steam

pumping, the solution favoured by Jessop. Faced with their

professional advisors’ conflicting views, the

eminent civil engineers John Rennie Snr. and Robert Whitworth were

engaged to

assess the situation and give an opinion. Following inspection and

deliberation the pair decided in favour of the tunnel and the

Committee ruled accordingly, placing Barnes ― who must already have

been carrying a considerable burden of other responsibilities ― in

direct control of the works.

In an age when large-scale tunnelling was in its infancy, Jessop’s

recommendation was undoubtedly the safer, although it would have

brought its own costs and problems. Locking over Blisworth Hill

would have caused a significant delay to traffic added to which

would be difficulty in

ensuring a sufficient water supply at the summit; there was also the cost of

operating and maintaining the locks and pumping system. On the other hand the tunnel has been much

affected down the years by distortions caused by movement in the

interface between the clay and oolite layers, which has led on

several occasions (most recently in the late 1970s and early 1980s)

to closure while expensive repairs and rebuilding was carried out.

By November 1797, the tunnel’s workforce had been deployed to more important

construction

further south, work being continued, at Barnes’s insistence, by a

skeleton team who

continued to drive headings into the hill to carry off the large

amount of subterranean water (a pilot heading later became the

standard tunnelling technique). Barnes

reports that this essential work was proceeding, and he recommends

that full-scale activities recommence by the following spring in

order that the tunnel “may be completed without loss of any time”.

――――♦――――

1798 – FURTHER PROBLEMS AT THE TRING SUMMIT

By June 1798, the advancing Canal had reached Berkhamsted from where

Barnes submitted a further report. In it he informed the

General Assembly that by the end of September he expected the Canal

to be navigable from Brentford to Wendover. He then returned to a

problem described in his previous report, “that the deep cutting

at Tring summit hath occasioned a great additional expense, by the

various slips that have unfortunately happened” and he goes on

to describe “the bottom of the Canal is in many instances so

soft, that a staff may be run down eight or ten feet perpendicular

below the bottom level of the canal with great ease”. The

condition of the ground through which the cutting was being driven

was probably due, in part, to it passing along the course (as it

then was) of the River Bulbourne, and partly to cutting into the

aquifer from which rose some of the springs in the locality, the

Bulbourne Springs and Clarke’s Spring being close to the line of the

Canal.

When Barnes undertook his survey of the Braunston to Brentford

route, he was faced with the problem of how best to take the Canal

over the barrier imposed by the Chiltern Hills. This 47-mile chalk

escarpment extends north-eastward from the Wiltshire Downs and the

River Thames towards the Dunstable Downs and Luton; skirting around

it was not an option. Of the slight depressions in the ridge, Barnes chose

to take the Canal through the Tring Gap. The problem was then to obtain sufficient water to

supply the summit level and the declining gradients to the north and

south.

The water resources in the immediate vicinity of Tring

comprised, principally, four springs, at Miswell, Frogmore, Dundale

and Bulbourne Head. The outflows from Miswell and Frogmore powered a

watermill at Gamnel, which the Company bought,

diverting its millstream (the Tring Brook) into the Wendover Arm. It

is unclear how the Dundale outflow was treated, but today it flows

underneath the Wendover Arm into Tringford Reservoir. As for

Bulbourne Head:

“About two miles from Ivinghoe is a place called Bulbourne,

belonging to John Sear, Esq. of Tring Grove. Here is said to

be the original source of the river Thames: there are two springs,

which divide within ten yards of each other, one running due east

and the other west. [15] Mr. Sear has

made a fine canal for a pleasure-boat, one mile in length.”

Topography of Great Britain,

George Alexander Cooke (pub. 1817)

At this date, the two springs ― known together as Bulbourne Head or Bulbourne

Water ― formed a considerable lake and the source of the River

Bulbourne, which today rises several miles to the south in the

vicinity of Dudswell. The deposited plans show “Bulbourne Water,

purchased of Mrs Mary Seare” [16] to lie along

the Canal’s summit route near the present day hamlet of Bulbourne. The 1793 Act gave the

Company authority to purchase part of Mary Sear’s

“plantation”, [17] providing that the

Company built a dam, fitted with a sluice, which the lady could use

to discharge water into the Canal or hold it back, which suggests

that she made use of the “Bulbourne Water”, perhaps as Cooke

seems to think, for leisure purposes. A further provision in the Act

also forbade the Company “to erect any lock

within the distance of One Mile on either side of the Bulbourne Head

aforesaid, without the consent of Mary Sear . . .” but the

reason for this provision (and others like it elsewhere in the

Grand Junction Canal Acts) are lost in time. It might,

however, explain why the original plan was to descend from the

northern end of the summit from a point on Lower Icknield Way to the

east of Marsworth Parish Church, rather than from Bulbourne

Junction.

Today, the dried-out depression once occupied by Bulbourne Water is

plainly visible in satellite mapping, with the Canal crossing its

western end. The reason that Bulbourne Water is now dry

stems from the draining effect of the Canal cutting on one side, and

of the London & Birmingham Railway cutting (constructed some 40

years later) on the other. It appears that during the construction of the railway

cutting, it was anticipated that the feed to Bulbourne Water would

be intercepted . . . .

“The

excavation for the London and Birmingham Railway, through

Tring-hill, is proceeding rapidly. Mr Townsend the contractor

has upwards of 500 men employed besides a great number of horses.

It is expected they will intercept the

‘Bulbourne

springs’

when they get deeper. These springs at present come directly

into the Grand Junction Canal. There is only one fault to be

found with the work in this neighbourhood, and that is the steepness

of the banks, they being only, for the excavations, in the ratio of

nine inches horizontal to one foot perpendicular. In the event

of a sharp frost, this ground, which is a sort of chalk rag, will

slake down like lime, and will consequently be a great nuisance

after the road is finished. The banks of the Grand Junction

Canal, in the deep cuttings collateral with the railroad, are more

than one to one, yet the slips which have occurred after a sharp

frost have been prodigious.”

The Mechanics' Magazine, Volume 23, 1835

. . . . and such was the case. Robert Stephenson, the railway’s civil engineer,

was later to report:

“. . . . The Tring cutting on the L and B R/Way presents another

forcible example of the constant and rapid absorption of water by

the chalk. In the execution of that cutting a very large

quantity of water was encountered, notwithstanding the situation was

on the summit of the chalk ridge, forming the actual brim of the

basin, where it could not be supplied with any water but such as

fell upon the immediate neighbourhood, yet it yielded upwards of one

millions gallons per day, and continues to yield an extraordinary

quantity up to this hour, without any sensible diminution.”

Minutes of proceedings of the Institution of Civil

Engineers: Volume 90, Part 4

Like Barnes before him, Stephenson had cut into the aquifer that fed the

Bulbourne Springs. The

“large quantity of water” to which he refers is now channelled

from the railway cutting through a heading to enter the canal

summit to the south of Marshcroft Lane Bridge. During the drought of

1934, Edward Bell, the Company’s section

inspector, reported that he was able to walk through the dried out

heading, but not wishing

to retrace his steps he emerged into the railway cutting. In his

memoir he mentions, as he climbed up the steep embankment, “feeling

very scared as an express train thundered along below”.

And so the Tring cutting was driven through waterlogged ground, with

its walls slipping in places. In his report, Barnes again explains

the technique of driving headings into the cutting walls to carry

off the water, but he now describes a further technique, that of

“piling, stretching and campshooting” (sic.) with the canal bed

being “planked very close”. Following World War I, the banks

along Tring summit were strengthened to protect against erosion. In

his memoir, Edward Bell recalls that:

“. . . . considerable difficulty was experienced in the Tring

Summit because halved tree trunks had been laid in the bed of the

canal across the waterway at intervals with timber piles at each end

of the tree to prevent the toe of the high offside bank from

encroaching into the waterway.”

Memoirs of a British Waterways Canal Engineer,

Edward Bell

No doubt Bell had encountered Barnes’s piling, stretching,

campshooting and planking.

――――♦――――

1798 – WORK PROGRESSING, COSTS ESCALATING

By June 1798, between two and three miles of canal had been

completed north of the Tring summit, about one million bricks had

been made and a team of nine moulders were at work making more. Barnes recommended to the Committee that the cutting northward

should proceed swiftly to meet with “the Great Chester Road”

at Fenny Stratford, thereby capturing the road transport to London and

increasing the Company’s toll revenue accordingly. This would then

free up manpower resources to enable “a strict attendance to the

execution of the [Blisworth] tunnel”, which Barnes

believed could be completed in two years “or thereabouts; then,

if the tunnel should not be early proceeded upon, the want thereof

will be so great an impediment to the navigation, that the delay

will hereafter be very much lamented”; in that assessment he was

undoubtedly correct, although the impediment would be mitigated to

an extent by Jessop and Outram’s horse-drawn railway over Blisworth

Hill.

Barnes’s report (2nd June, 1798) was accompanied by a summary of the

Company’s cash account at 1st May, 1798:

| Receipts |

… … … … … … … … … … … |

|

£620,687 |

|

| Payments: |

|

|

|

|

| |

Purchase of land, salaries, etc |

£143,458 |

|

|

| |

Payment of interest to subscribers |

£40,061 |

|

|

| |

Building cost of 47 miles of Canal |

|

|

|

| |

Reservoirs, Feeders, etc. + WIP |

£429,687 |

£613,206 |

|

|

|

Balance |

|

|

£7,481 |

| |

Monies owing |

|

|

£43,226 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Funds available |

|

|

£50,707 |

That only half of the 93½-miles of canal had been opened by this

date was a clear indication that the funds then available were

insufficient to complete the project and that further capital was

needed. And so the Committee announced their intention to raise

£150,000 of 5% loan stock, convertible to shares by 25th March, 1803

(most of it was). But the under-estimation of construction

costs continued, the

outcome being that in later years the Committee were to return to

their shareholders for further capital in one form or another until

by June, 1804, the Company’s capital account exceeded £1.3M. Against

this background, it becomes easier to understand why the construction

of some of the planned branch canals were delayed or not proceeded

with.

In the meantime, the continual haemorrhaging of capital through the

5% p.a. interest payments on subscribers’ shareholdings, ceased.

This decision was taken at the General Meeting held on 6th November 1798,

by which time the cumulative interest already paid exceeded £40,000. At this

meeting it was decided to convert the interest due for the 12 months

ending midsummer 1798 into “a Mortgage or Assignment of the tolls

of the said Navigation”, at 5% p.a. interest (a further loan),

and that following midsummer 1798, shareholders would instead

receive dividends to be paid out of toll revenue after deductions

had been made to cover operating expenses.

Since the first sections of the Canal had been opened for business,

[18] toll revenue had been rising gradually,

assisted by Parliament’s approval of additions and increases to the

toll rates laid down in the 1793 Act. The Act of 1805 [19]

granted the Company further relief by lifting another provision of

the 1793 Act, that which permitted toll-free use of the Canal by the

armed forces. Before the coming of public railways, there are

numerous newspaper reports of the Grand Junction Canal being used

for military transportation, undoubtedly added to by the needs of

the French Wars. Lifting this exemption would have provided a

useful boost to revenue.

――――♦――――

1799 – THE OUSE VALLEY AND BLISWORTH HILL

By June 1799, the Committee was able to report that they had

inspected 64 miles of completed Canal, which despite the severe

winter just passed they found to be in satisfactory condition. Barnes was also able to report (probably in May 1799) that work on

the section between the Tring summit and Fenny Stratford was

progressing “very rapidly” and he remained optimistic that

the terrain onwards to the temporary terminus to be set up to the

south of Stoke Bruerne “appears so very favourable for execution”. Furthermore, the problem of water supply would there be met by the

drainage water issuing from the Blisworth Tunnel workings, which

together with other sources was judged ample “to supply the locks

equal to any trade that can be expected to arise”.

The major obstacle between Fenny Stratford and Cosgrove was the

valley of the Great Ouse, which lies across the line of the Canal

and is the lowest point between the summits at Tring and Braunston.

The Canal was originally planned to descend into the river

valley via a flight of four locks and to ascend the opposite side by

a further four lock flight. Locking into and out of the river valley would

have delayed traffic added to which, because the river was to be

crossed on the level, there was the potential for serious disruption

when it was in flood, which occurred from time-to-time. The locks on

the southern side of the valley would also have increased the demand

for water from the Tring summit where it was often at a

premium, this lockage water being lost into the Great Ouse.

|

An artist’s impression of the

Cosgrove

Embankment under construction, showing Jessop’s aqueduct and

the original scheme for crossing the valley. |

In 1799, Barnes suggested to the Committee that, as an alternative,

the Ouse valley might be crossed by a high embankment in which a

section would contain an aqueduct to carry the Canal over the river. This would avoid the problems inherent in the planned system of

locks, but such a substantial earthwork ― approaching a mile in

length ― would take about two years to build. The Committee decided

in favour of the embankment and aqueduct, but to avoid delay to the

opening of the final section of canal (Fenny Stratford to Stoke

Bruerne) while they were being built, they decided to press ahead

with the construction of the two planned flights of locks, but to

build them as temporary structures. [20] They were

completed in September, 1800.

The progress now being made towards Cosgrove laid bare the obstacle

of Blisworth Hill. Other than excavating the drainage headings,

work on the tunnel had been dormant since March 1797 when the

original alignment had been abandoned. It was now apparent that the

new tunnel would not be complete in time to meet the main section

of the canal then advancing rapidly from the south. Writing in 1797,

William Pitt described the problem that the Committee faced:

“The trade of this canal makes a stop at Blisworth at present;

very considerable difficulties having arisen in the execution of a

tunnel, or excavation, of about two miles in length, under the high

ground at Blisworth: the difficulties arise from the under stratum,

on a line of the tunnel, which consists of a calcareous [21]

blue marl, extremely friable on exposure to air or moisture; and,

the springs being powerful, the water, on coming in contact,

converts this marl into liquid mud, which has occasioned the blowing

of the shafts and sheeting of the tunnel; and some time must elapse

before it can be finished and rendered navigable.”

The

Agriculture of the County of Northampton,

William Pitt (1797)

As arrangements currently stood, it was realised that Blisworth Hill

would impose an increasing barrier to commerce, particularly in shipping

the southbound cargoes of coal that were building up at the

‘port’ of Blisworth:

“Pit-coal from the Staffordshire collieries, is now brought

plentifully to Blisworth, by the Grand Junction canal . . . . At

Blisworth are erected extensive wharfage and warehouses for goods,

two new inns on the canal banks, and there are five or six thousand

tons of coal in stacks on the wharfs; a large number of canal boats

and trading boats in the port, and two new ones on the stocks,

building. A considerable hurry and bustle of business is created

here by this canal.”

The Agriculture of the County of Northampton,

William Pitt (1797)

Apart from coal, toll records show that among the other bulk

commodities that were now being shipped by canal were stone, timber,

pig-iron, salt, bricks and slate ― indeed, in the years that

followed the Canal’s opening, traditional

thatched roof coverings in its locality were gradually replaced with slate. The

build-up of goods at the transhipment wharfs on either side of

Blisworth Hill was such that the

existing road [22] between them was considered

inadequate to cope with the increasingly heavy flow of traffic. To

this end, Jessop investigated the feasibility and economics of

constructing a double-track horse-tramway. In his

report of April,

1799 (counter-signed by Barnes), he submitted a detailed argument in

favour of a rail link to run from Blisworth “to the crossing of

the Towcester River”, [23] a distance of some

3¼-miles at an estimated cost of £24,000. The Committee

endorsed the plan, informing the shareholders that compared with

road transport the facility of an “iron road” was “beyond

calculation”. [24]

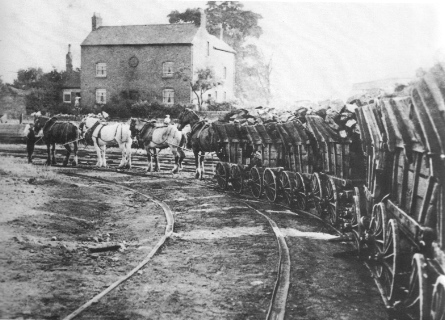

|

|

|

The Little Eaton

Gangway, an example of a

horse-drawn

tramway. |

Benjamin Outram (1764-1805), canal engineer and the leading

practitioner of early railways, [25] was

contracted to construct the line. The form of track that he used was

L-shaped cast iron plates fastened to stone sleepers with oak

pegs, the sleepers being laid on a bed of gravel and small stones. No record of the line’s gauge has survived, but it is thought to

have been 4ft 2ins, a gauge favoured by Outram for other of his

railway projects. The rail wagons were fitted with flat rather than

the flanged tyres used by later rail vehicles; these were guided by

the uprights of the L-shaped plates, the plates’ horizontal sections

supporting the wagon’s weight. Flat tyres also permitted the wagons

to be run off the rails at either end of the line and hauled across

the wharfs where ― at least in the cases of coal for nearby

Buckingham ― they were hoisted into a narrow boat. The tramway appears to have been in operation by June of

1800, for Company advertising of that date refers to “. . . . a

temporary cast-iron rail road has been adopted, until the tunnel and

locks could be completed . . . .”

Earlier that year, the Canal had reached Fenny Stratford where the

usual ceremonial opening took place to mark the occasion:

“The Grand Junction Canal was on Wednesday opened for barges from

the Thames at Brentford, to Fenny Stratford, in Buckinghamshire, and

early in the morning a number of boats departed from Tring, in

Hertfordshire, at which place the canal has been completed these two

years past; about one o’clock they passed through Leighton, in

Bedfordshire; and a short distance before they reached Fenny

Stratford the Marquis of Buckingham, accompanied by a number of

friends and principal proprietors, attended by the band and a party

of the Buckinghamshire Militia, met them. — They then went in grand

procession to Fenny Stratford, where they were received with firing

of canon belonging to the town and other demonstrations of joy. The

Marquis and the proprietors retired to the Bell Inn to dinner”.

Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

31st May, 1800

――――♦――――

1800 – BLISWORTH TUNNEL

Work had now commenced cutting from the River Tove

towards Cosgrove to meet the Canal advancing from the south. When

exactly the two sections met is unclear; the respected canal writer

John Priestly gives only the year, 1800, [26] but

other known dates suggest that, if this was so, it was late in the

year. By the following June, the Company was

advertising the canal to be complete from Brentford to Braunston,

with conveyance over Blisworth Hill by way of an “iron railway”.

It is unclear whether this advertising was purely to drum up trade, or an

indication that the Canal did not open for business immediately.

During the summer of 1800, advertisements appeared in the press

inviting the public to subscribe to a £100,000 5% convertible loan,

its principal stated purpose being to fund completion of the

Blisworth tunnel. [27] Since work on the tunnel

had been abandoned in March 1797, the only activity had been to

drive a narrow brick-lined heading beneath the alignment of the

future tunnel to drain the water that had led to the original

workings being abandoned. With the Canal now complete in other

respects, attention was turned to the tunnel’s excavation.

Plans for the tunnel [28] were drawn up by Jessop

and the work put out to tender. The successful bidder was a

consortium, whose rate was £15 13s. per yard, payments to be made

against completion certificates authorised by Barnes. Twenty-one

shafts (pits) are known to have been sunk along the tunnel’s

alignment down to the level of the Canal, and from the base of each, excavations

commenced in each direction to provide (including the two

tunnel ends) forty-four working faces. There is visible evidence

that the debris hoisted up the shafts by winding engines (horse gins) was

spread over the adjacent ground.

Excavation progressed well, but it became apparent that cost was

exceeding budget and that the consortium would be unable to complete

the contract for their stated price ― the eventual cost per yard was

twice that originally estimated. The contract was therefore

liquidated, and in March 1804 Barnes again took over direct

supervision of the work, Caleb Maulin being appointed site engineer. Maulin did not survive long in the role, being dismissed after

shortcomings appeared in his accounting; he was replaced by the

highly competent Henry Provis, who also supervised construction of

the flight of locks linking the Blisworth and Cosgrove pounds.

Surprisingly, the rate of fatal accidents on the Blisworth tunnel

project appears to have been low. So far as can be ascertained, only

two coroner’s inquests (three deaths) were recorded in the press of

the time, although the first of these reports refers to another

fatality for which no report has been discovered; and there may have

been others.

The first fatality was due to suffocation caused by ‘damp’. Gases

(other than air) in coal mines in England were collectively known as

‘damps’, a name thought to be derived from the German dampf

meaning vapour. If so, the term was probably introduced into England

by German miners who were brought here in the 17th century to help

develop deep mining:

“ACCIDENTS.—On Wednesday last an inquest

was taken on the Plain, in the parish of Blisworth, on view of the

body of Benjamin Ludlow, a young man employed on the Grand Junction

Canal works, who having occasion to go down a sinking pit

[one

of the working shafts] on the Plain, before he had got to the

depth of ten yards called to be drawn up, but the damp had so great

an effect on him that he was instantly suffocated, and fell to the

bottom of the pit; when David Williams, a miner, attempted to go

down to his assistance, but had nearly lost his life in the attempt,

as before he had descended fifteen yards he was under the necessity

of making a signal to be drawn up, and was nearly suffocated when

taken out. The damp was so strong that it was necessary to

throw a large quantity of water into the pit, and it was an hour and

a half before any person would venture to fetch up the body of the

unfortunate youth. The Jury brought in the verdict Accidental

Death. The deceased had a brother who lost his life about two

years since, by falling down a pit, on the Plain, more than thirty

yards deep.”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

8th November, 1800

The second coroner’s report investigated two further fatalities,

also at one of the tunnel’s pits:

“. . . As they were drawing two of the workmen up from one of the

shafts, by a sudden jirk (sic) of the horse, the basket in which the

men stood slipped off the hook affixed to the rope, by which

accident they were both precipitated to the bottom (a depth of sixty

yards); one of then was killed on the spot and the other survived

but a few hours.”

The Northampton Mercury,

22nd October, 1803

――――♦――――

1805 – COMPLETION

By March 1805, work on the tunnel was complete and the final section

of the Canal

was flooded. On 25th March, an opening ceremony took place with great

jubilation (and the customary dinner for the Company’s big wigs):

“That grand line of communication between the metropolis and the

most distant parts of the kingdom which the Grand Junction Canal was

to effect, was completed on Monday last, when an amazingly large

concourse of people assembled, some of them from considerable

distances, to view the stupendous works at Blisworth Tunnel, and to

see the grand procession in honour of the opening of it. One of the

Paddington packet-boats, called the Marquis of Buckingham, was the

first that went through the Tunnel. This was early in the morning,

in order to join the other boats assembled at the north end of the

Tunnel, at Blisworth, to form the grand procession. About eleven

o’clock the Committee of the Canal company (who had superintended

this great work), Messrs. Praed, Mansell, Unwin, Parkinson, Smith,

and a great number of others of the principal proprietors, entered

the boats, attended by Messrs Telford, Bevan and other of the

engineers employed on the Canal, and by a band of music, and

proceeded into the Tunnel amidst the loudest acclamations of the

spectators. The pitchy darkness of the Tunnel was shortly relieved

by a number of flambeaux and lights, but the company in general

seemed lost in contemplating the stupendous efforts by which this

amazing arch of brickwork (about eighteen inches thick in general,

fifteen feet wide and nineteen in height, withinside, being of an

elliptical form, 3080 yards in length) had been completed between

the 10th August 1793, and the 26th February 1805. The height of the

hill, above the Tunnel, being, for a considerable way, full sixty

feet, for drawing up the clay and soil which were excavated, and

letting down the materials to different parts of the works, nineteen

shafts, or Wells, were sunk on different parts of the line, and a

heading, or small arch, was run or formed the whole length, below

the present Tunnel, with numerous cross branches to draw off the

springs of water, which would otherwise have impeded the work.

In an hour and two minutes the boats with their company arrived at

the south end of the Tunnel, and were greeted by the loud huzzas of

at least five thousand persons, who were assembled, and who

accompanied the boats with continual cheers as they proceeded down

the locks to Stoke, and from thence to Old Stratford.

The principal company retired to the Bull Inn, at Stony Stratford,

and about six o’clock, 120 proprietors and friends of this grand

undertaking sat down to an excellent dinner, Mr. Praed in the chair. The utmost harmony and conviviality prevailed among the company till

near twelve o’clock, when they broke up. All the other inns in Stony

Stratford were filled with company, and many of the parties did not

separate till a late hour.”

Northampton Mercury,

30th March, 1805

Telford inspected the Blisworth tunnel a few months later:

“This Tunnel, which was opened on the 25th day of March last, has

been laid out in a perfectly straight direction; the materials and

workmanship seem good of their several kinds, and as headings have

been driven so as to collect and conduct the water of the adjacent

grounds into directions proper for protecting the Brickwork, and

preventing injury being suffered by the goods in passing, I have no

doubt but that, with due regulation and attention in future, this

difficult and expensive work will fully answer the purposes of the

Navigation.”

The General State of the Grand Junction Canal,

Thomas Telford (1805)

The Cosgrove embankment and aqueduct were completed shortly after

the Blisworth Tunnel. Curiously, in his report Telford makes no

comment on the standard of the work, except to say that it is in the

hands of “respectable and responsible contractors . . . . and as

I have, from good authority, their assurance that every part shall

be left in a perfect state, it is unnecessary, at this time, to

enter particulars . . . .” which suggests that the great civil

engineer’s opinion was, naively as events were to prove, based on

hearsay rather than on personal inspection. One wonders whether the

Committee were satisfied with what they read. So far as the local

press was concerned:

“Grand Junction Canal.—We are happy to announce the completion of

nearly all the great works which were going on upon this important

and extensive line of inland navigation, rendered peculiarly

interesting to Englishmen by forming an immediate connection with

the British capital, and the numerous canals which intersect and

cross each other in all directions between our great manufacturing

towns and works. On Monday morning last, the stupendous embankment

between Wolverton and Cosgrove, near Stony Stratford, was opened for

the use of trade. Boats navigating the Grand Junction Canal will now

avoid the delay, labour, and danger, of passing eight locks.”

The Northampton Mercury,

31st August 1805

――――♦――――

THE FINAL BILL

In the introduction to his inspection report of 1805, Thomas Telford

felt obliged to include a few words in justification of the Canal’s

much inflated construction cost:

“The number and magnitude of the obstacles to be overcome, united

with the rapid increase which has taken place in the value of labour

during the time the works have been under execution, must also, in a

great measure, satisfy the minds of subscribers why additional sums

have been required beyond those originally provided for the purpose

of the undertaking.”

Although the Grand Junction Canal now formed a continuous waterway

from Braunston to Brentford, with the important Paddington Arm also

in operation, its investors did not at first receive the handsome

returns that their investment was to produce in later years: [29]

“In 1806, I find the Blisworth tunnel completed, and a very

masterly and surprising work of art; the whole main line of this

canal is also completed, and some of its collateral branches; but

the communication with Northampton is by a railway: on this great

concern, (the Grand Junction Canal) £1,500,000 have been

expended; shares at present under prime cost, and dividends small,

owing to improvements still making, and paid for from the tonnage;

but hopes are entertained of its coming to pay a good interest upon

the expenditure. Reservoirs of water and other improvements

are in hand or in contemplation.”

The Agriculture of the County of Northampton,

William Pitt (1806)

. . . . and this letter dated 10th July, 1806, published in the much

respected periodical, The Gentlemen’s Magazine: [30]

“Much has of late been said in the public papers, and perhaps

with truth, of the excellence and utility of the Grand Junction

Canal; but many of your readers who have seen their puffing

paragraphs, will be surprised to hear that the benefit, if any, has

hitherto, with the exception of a few individuals, been to the

publick alone; and the original proprietors have as yet received no

advantage whatever from the concern. It is now 17 or 18 years since

the undertaking was begun; new schemes have been successively

proposed and executed, but the proprietors are still in vain

expecting their golden dreams to be realized. To the original

speculators, this may be no more than the just reward of their

views, if avarice, as it probably was with some, not the public

good, was their motive for subscribing. But so long a time has now

elapsed since the commencement of the undertaking, that many of the

first subscribers have been long dead, and their representatives are

now suffering the consequences of ill-judged speculation.

From the pressure of the times, many widows and young ladies, whose

fortunes, with the hopes of extraordinary interest, were vested by

their friends in the stock of this Company, have either been obliged

to sell their shares at a very great disadvantage and loss, or to

struggle with difficulties which could not have been foreseen or

expected . . . .”

The various applications to Parliament over the years to 1803 had

authorised the Company to raise capital far in excess of Jessop’s

initial estimate (£400,000):

|

Act 33 Geo. III |

1793 |

£600,000 |

|

36 |

1795 |

225,000 |

|

38 |

1798 |

150,000 |

|

41 |

1801 |

150,000 |

|

43 |

1803 |

400,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

£1,525,000 |

Of this, £1,404,000 was raised, but later developments were funded

from revenue that inflated the final bill to over £1,500,000, for there

was much that remained to be done to complete the full extent of the

project. The important Paddington Arm had opened in 1801, although

contemporary reports suggest that, initially at least, the

facilities available to support trade at Paddington Basin needed

much development. [31] Following the opening of

the Blisworth Tunnel, the iron rails from the Blisworth Hill

plateway were reused to connect Northampton with the Canal at Gayton; but a decade was to pass before Northampton ― and

Aylesbury also ― received branch connections to the main line. By

1806, the Cosgrove embankment was showing signs of failure; repairs

were made, but two years later the Cosgrove aqueduct failed,

severing the canal and leading, in 1811, to Benjamin Bevan’s iron trunk

aqueduct that stands today. In places side ponds were built to

conserve water and more reservoirs and pumping stations were built, particularly at Tring.

Despite the many calls on the Company’s exchequer during its early

years, the Canal was coming of age and starting to flourish (Appendix

II. gives a brief view of the waterway in 1813). In 1810, annual

receipts amounted to £168,390 12s; in 1815, £155,000; [32] and by 1819:

“. . . . the annual gross revenue of the canal amounted to the sum

of £170,000; it possess 1,400 proprietors; and its shares of £100

have recently sold at from £240 to £250 each. Many of the first

capitalists in the kingdom are its proprietors, and its usual

routine of business is so conducted as to give satisfaction to all

who are connected wit it.”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell.

Share prices peaked at almost £350 (for a £100 share) in 1824,

whilst dividends peaked at 13%, a level that was maintained for

seven years until 1832, when it fell to 12%. Following the coming of

the public railways, the Company’s share price

declined to around par and the dividend to 4%, at which levels both

remained stable for a long period. [33] By

comparison, the Oxford Canal was built before the inflationary

pressures of the French Wars, resulting in a lower construction

cost and a higher return to its investors; in 1833, that company was

paying a dividend of 32% on its £100 shares, which at the time had a

market value of £595. [34]

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

THE GRAND JUNCTION WATERWORKS COMPANY

1811-1904

The Grand Junction Waterworks Company was established in 1811 to

exercise the water supply rights vested in the Grand Junction Canal

Company by their Act of 1798. [35]

The Company extracted their supply from the Paddington Arm;

unsurprisingly, this water was found to be of poor quality. In 1820,

supply was switched to the Thames near the northern end of the

present Chelsea Bridge, opposite the Ranelagh sewer and Westbourne

Brook. When this became known it caused a public outcry:

“. . . . that the water now taken from the Thames at Chelsea by

the Grand Junction Canal Company, and supplied to more than seven

thousand families, was charged with the contents of the great common

sewers, the drainings from dunghills and laystalls, the refuse of

hospitals, slaughter-houses, colour, lead, and soap-works,

drug-mills, and decomposed animal and vegetable substances; and that

the most eminent professions men had pronounced it to be a filthy

fluid, destructive of health . . . .”

The

Hull Packet, 24th April, 1827

A campaign led by Sir Francis Burdett, M.P. for Westminster,

resulted in the appointment of the first Royal Commission to inquire

into the quality of the water to be supplied by the metropolitan

water companies. However, it was not until 1835 that powers were

granted to open a new intake at Brentford. This resulted in the

magnificent Kew Bridge pumping station. Opened in 1838, it was

equipped with a Maudslay beam engine that pumped water along a

thirty inch main for five and a half miles to Paddington. This was

the first long trunk main to be laid by any of the metropolitan

water companies.

In the 1850s the quality of drinking water was again of public

concern. Charles Dickens took an interest in the topic and in

carrying out research visited the Kew Bridge Pumping Station in

March 1850. He recorded details of his visit in his campaigning

journal Household Words, in an article published in April 1850

entitled “The Troubled Water Question”. The epidemiologist

John Snow reported on an outbreak of cholera, pinpointing a

workhouse in Soho that had escaped the contagion because it was

supplied by the Grand Junction rather than the other local supply.

Following the passage of the Metropolis Water Act (1852) – under

which it became unlawful for any water company to extract water for

domestic use from the tidal reaches of the Thames ― the Grand

Junction Waterworks Company again moved their intake, this time to

Hampton (Sunbury Lock) where deposit reservoirs and a pumping

station were completed in 1855.

Additions were made to the Hampton works during the remainder of the

century and in 1882 the Company began to filter part of the supply

there, thus relieving the Kew Bridge works. A large open reservoir

for filtered water was inaugurated on Hanger Hill, Ealing, in 1888. Acts of 1852, 1861 and 1878 enlarged the area of supply and by the

turn of the century the company’s boundary stretched from Mayfair to

Sunbury.

Following the Metropolis Water Act (1902), the functions of the

Grand Junction Water Works Company were assumed in 1904 by the

Metropolitan Water Board and the company ceased to exist.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL:

From:

An Historical and Topographical Account of Fulham,

T. Faulkner (1813).

THROUGH the

northern extremity of this parish runs the Paddington Canal, for

which an Act was obtained in the year 1795, communicating with the

Grand Junction Canal at Norwood. This latter canal was

executed under a Bill obtained in the year 1793, and begins at

Braunston in Northamptonshire, where it joins the Oxford Canal, and

ends at the Thames near Brentford. By this inland navigation

the metropolis is connected with all the different canals which have

been made in the midland and north western parts of England; thereby

affording a cheap and easy conveyance of all the various articles of

manufacture, and the produce of the counties through which the line

of canals passes, comprehending the great and commercial port of

Liverpool, the considerable manufacturing towns of Manchester,

Sheffield, Birmingham, Nottingham, &c. the salt mines of Cheshire,

the potteries, the coals and iron of Staffordshire and

Worcestershire, besides the great advantages resulting to the

agricultural interests of the country by the transport of lime and

various sorts of manure. Great quantities of timber for his

Majesty’s dockyards at Deptford, and for the use of ship builders in

general, are conveyed by the same channel; also government stores

and ammunition to the depot, which upon the completion of this

canal, was established on an extensive scale at Weedon. The

length of the Grand Junction Canal, with all its collateral branches

is 140 miles. The canal was not completed till March 1805,

when the Blisworth Tunnel was opened. The long interval from

its commencement until its final completion, may be attributed to

the very considerable difficulties which the undertakers had to

encounter, during the progress of the works, independent of the

excavating such a vast length of canal, which is 36 feet wide, at

the top level, 24 feet at the bottom, and 4 feet 6 inches in depth.

It required the erection of upwards of 200 bridges, the construction

of 110 locks of 86 feet in length and 15 feet in clear width, and an

average rise of 7 feet in each, requiring 9,030 cubic feet, or 250

tons of water; the forming of two tunnels, one at Blisworth and the

other at Braunston; the former of 3,080 yards in length, 15 feet

wide and 19 feet high, and the latter 2,045 yards in length and of

the same dimensions as the former.

The great range of chalk hills, near Tring, are passed by a deep

cutting, extending 3 miles in length, and the greatest depth 30

feet. In several other parts of the canal, there are likewise

deep cuttings, of considerable magnitude. The canal is carried

over the valley of the river Ouse, between Wolverton and Cosgrove,

by an embankment of 40 feet in height, and an aqueduct, which is now

constructed of iron, the former brick one, of three arches, having

fallen in in the year 1808. There are likewise embankments of

almost equal magnitude at Weedon, and at Bugbrook, besides numerous

lesser embankments and aqueducts in different places; there are

seven large reservoirs, from which, and other resources, the canal

is at all times most abundantly supplied with water. The trade

upon the canal, which is now very extensive, has been uniformly

increasing. Articles of commerce, including those of every

description, conveyed along the line in the last year, mounted to

527,767 tons. This trade, great as it now is, must soon

receive a very considerable addition from other lines of

communication, which are now forming, particularly from the Grand

Union Canal; the works of which are now in a state of such

forwardness, that they are expected to be completed by the latter

end of next year. This canal will join the Grand Junction

Canal at Long Buckby, in Northamptonshire, and the Old Union Canal

at Market Harborough; a direct inland navigation will then be formed

from the metropolis to the north eastern parts of the kingdom.

A canal is likewise now making from the Grand Junction Canal at

Marsworth to the town of Aylesbury. Another collateral branch

from the Grand Junction Canal is likewise about to be made to the

town of Northampton to join the river Nene. And in the late

sessions of parliament, a bill was obtained for extending the canal

at Paddington to the Docks at Limehouse, by which the goods brought

up by the Grand Junction Canal will be forwarded in the same boats

directly to the place of their destination, instead of being

deposited in warehouses at Paddington, and afterwards carried from

thence into the city, and to the Docks.

We have thought it necessary to draw the attention of our readers to

a work of such considerable importance as that of the Grand Junction

Canal, embracing as it does so many objects worthy the consideration

of a commercial people, and affording so many advantages to the

merchant, the manufacturer, and the agriculturist. |