|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH

WATER.

THE ROUTE

III. UXBRIDGE TO BRENTFORD,

AND

THE

PADDINGTON ARM

“UXBRIDGE, a market town in

Middlesex, 15 miles W. from London, in the road to Oxford, is

situated on the river Coln and Grand Junction Canal, over each of

which it has a bridge . . . . This town, which is governed by two

bailiffs, two constables, and four headboroughs, is principally

noted for its very great corn market, and for its opulent mealmen,

who are chiefly Quakers, and are supposed to influence the price of

corn in the London market: on the river are many powerful flour

mills, and a vast deal of malt is made in the neighbourhood.

During the summer season, a passage-boat constantly plies to and

from London, which is highly advantageous to the inhabitants.”

A Pocket Companion for the tour of London and its

Environs (1811)

|

|

|

|

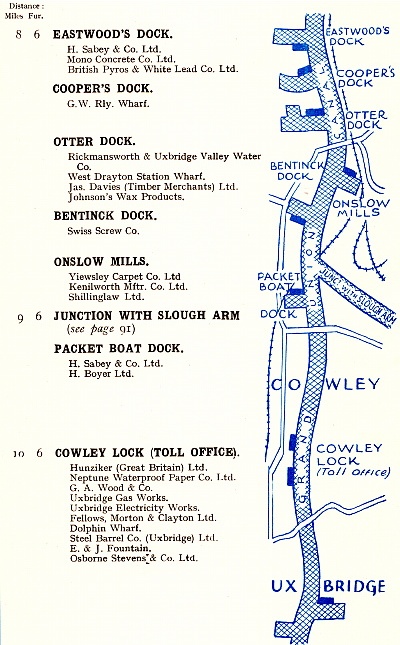

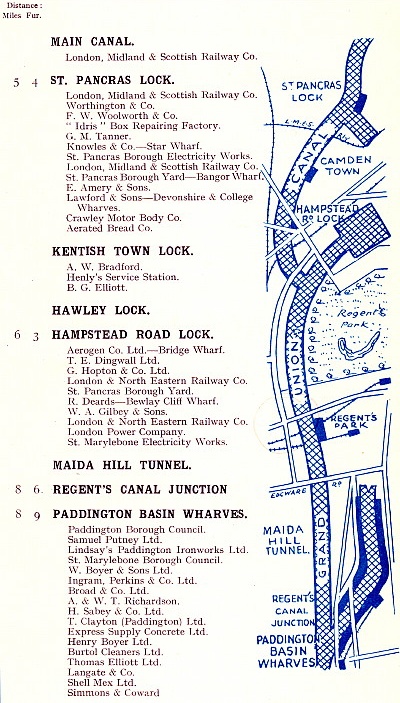

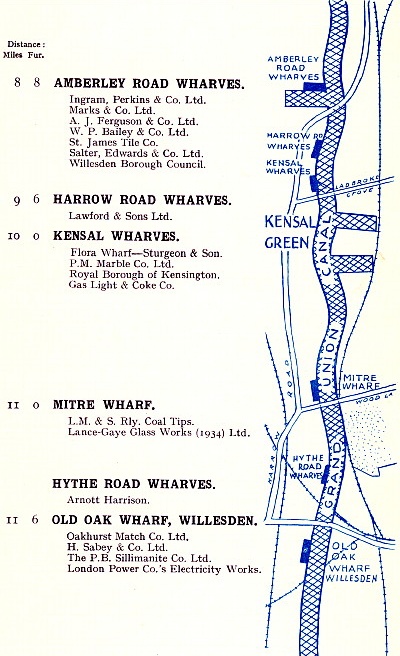

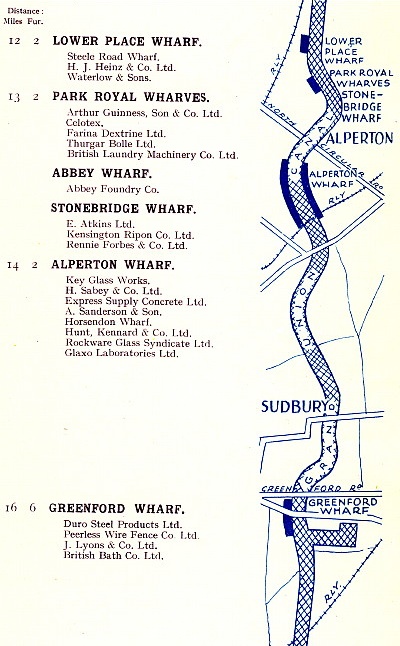

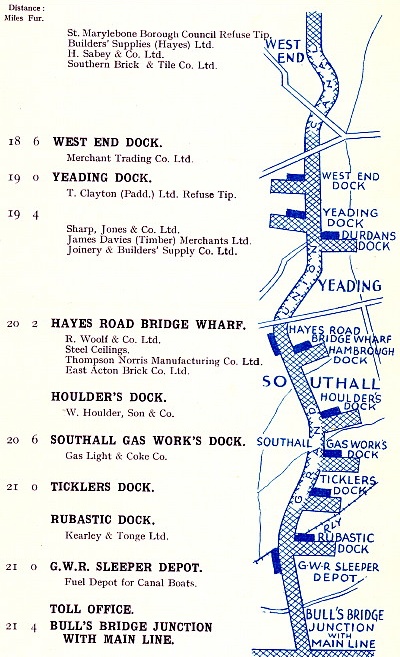

Grand Union Canal Company

route map c.1938, showing the wharves and docks that

lay between

Uxbridge and Brentford. |

At

Uxbridge, the Canal forms the borough’s western boundary. Following

its opening in 1794, waterborne commerce soon sprang

up accompanied by extensive wharves:

“The Grand Junction Canal, for the making of which an act of

parliament was obtained in 1793, passes by this town. It was begun

by cutting on Uxbridge Moor the first of May of that year. The

principal articles of commerce on that canal are flour, grain and

coals. . . . The following is an accurate statement of the

quantities [tons] of the different articles conveyed from the

Thames at Brentford to Uxbridge, and from Uxbridge to the Thames, in

the year 1799 (obligingly communicated by Benjamin Way, Esq). . . .”

|

Flour |

4,612 |

Lime |

14 |

|

Grain |

4,968 |

Manure |

164 |

|

Coals |

6,650 |

Coke |

68 |

|

Ashes |

1,318 |

Loam |

49 |

|

Stone |

108 |

Timber |

18 |

| Tiles & brick |

131 |

Sundries |

1,821 |

An historical account of those parishes in the

county of Middlesex,

Rev. Daniel Lysons M.A. (1800)

The writer does not distinguish between imports and exports, but

grain and coal are likely to have been among the former,

and flour the latter. Although flour milling has now ceased,

Uxbridge was once a long established flour milling centre

covering a wide area, and for some two centuries it produced most of London’s flour. The

town’s last mill, the ‘William King Flourmill’, stood on the

canal bank just above Town Lock and a large proportion of its wheat

was delivered there by narrow boats direct from Limehouse or

Brentford. The mill’s engine room, equipped with a magnificent 80hp Robey horizontal tandem compound condensing engine, was apparently a

sight to behold, while the nearby boiler house sported two

spotlessly clean Lancashire boilers. A 50hp Gilkes water turbine

supplied stand-by power using the 7ft head across the Town

Lock where there is no shortage of water, for this stretch of the

Canal is amply supplied by the River Colne. Although William King’s

Mill ceased working in 2001, its name lives on in the popular Kingsmill brand of bread.

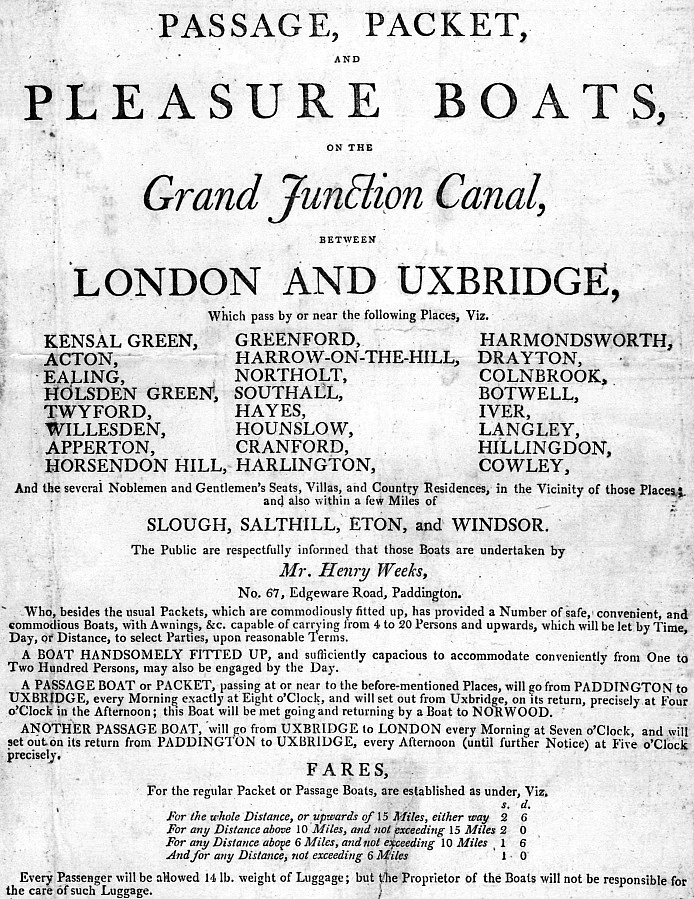

Following the opening of the Paddington Arm in 1801, a passenger

service commenced between Uxbridge and the Metropolis. Initially run

by the Company, the service was later franchised to Thomas Homer for

£750 per year. The ‘packet boat’, whose crews were noted for

their smart blue uniforms with yellow capes and yellow buttons,

seems to have been well used at first, but the journey time was too

long and the service was discontinued after several years.

Homer, who had been Superintendent to the Grand Junction Canal

Company, went on to be the instigator

of the Regent’s Canal and was employed as Company Secretary, but in 1815

he was convicted of embezzling £4,000 and sentenced to

seven years’ transportation.

As well as supporting existing industry the Canal’s impact on

Uxbridge ― as with many other places ― was to open up new

industrial development. By 1814 a mill had been built for the

manufacture of plate-glass, and other industrial

premises that were later set up near the Canal included a gas-works, parchment works and

mills for processing oil, mustard

and flour. Indeed, the waterway continued to provide the town

with an important trading link well into the 20th Century:

“At Uxbridge are situated large gas and electricity undertakings,

both of which receive their supplies of coal by canal. Messrs

Fellows, Morton and Clayton Ltd. have another depot at this point

and a repair dock for their boats. There are also a number of

wharves in this locality for handling large quantities of grain and

timber.”

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material, c.

1938

The Uxbridge Boat Centre, just to the south of Bridge 186

(Rockingham Road), was once the boatyard of Fellows, Morton and

Clayton Ltd., one of the largest carrying companies on the Canal, which

ran the yard until they ceased trading in 1948. FMC

built many of their own boats, their yard at Saltney in Birmingham

specialising in metal and wood composite construction while

that at Uxbridge built wooden boats (their last new boat, the Clent,

was built in 1947). Wooden boats were cheaper to

build, the expectation being that they would be worn out long before

the rot of old age set in.

|

|

|

Frays, one of a

pair of new barges designed to transport

building

aggregates on the Uxbridge section of the Canal. |

Despite the general demise of canal carrying, the Uxbridge section

of the canal recently experienced a modest return to commercial

use. Canal transportation remains suitable for bulk cargoes that are

not required quickly, and it brings with it the added advantages of

keeping heavy traffic off congested roads and minimising the

carrier’s carbon footprint:

Of the four principal transport modes, water is by far the least

damaging to the environment. A 12 barge train operating on the

Grand Union Paddington Arm in the 1950s, for example, could carry

over 700 tonnes of freight whilst producing less than 3% of the carbon

emissions of the 30+ road vehicles it replaced. Even a single

70 tonne capacity barge produces less than 25% of the equivalent

road vehicle emissions when carrying heavy loads such as aggregates

and less than 15% when carrying low density loads such as waste.

British Waterways: seventh report of session

2006-07, Vol. 2.

An example was the freight contract

between British Waterways and two aggregates companies ― Hanson and

Harleyford ― to transport

450,000 tonnes of sand and gravel by barge from a gravel pit at

Denham, through Uxbridge to a canal-side concrete mixing plant near

West Drayton. Although the two sites are only five miles

apart, it was envisaged that the material would be transported by

road on the highly congested western sections of the M40, M25 and

M4. By using the canal, it is estimated that 46,000 road journeys

were saved by the end of the contract.

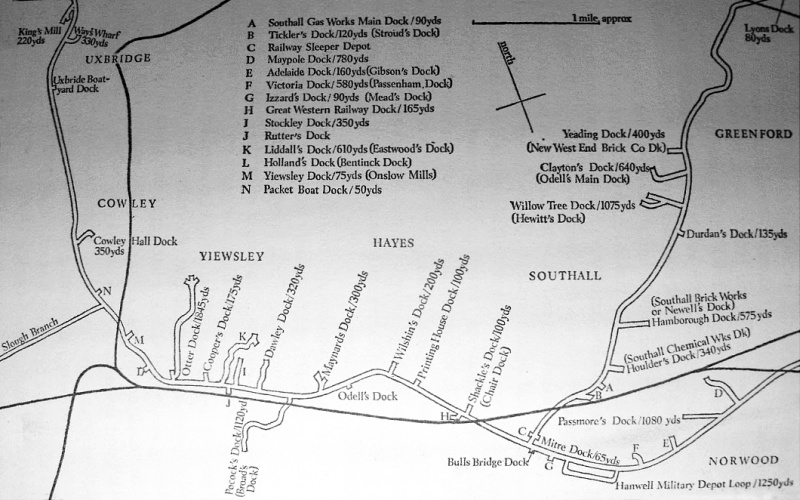

Canal docks and cuts, Uxbridge to Norwood.

Some

2½ miles south of Uxbridge the canal reaches Cowley lock (No. 89).

Here commences the last extended pound [1] on the main line before it commences its final descent from Norwood

to the Thames. North of Uxbridge the canal flowed mostly through

rural landscape, but from Uxbridge southwards the surroundings become

increasingly industrialized, although there is some parkland nearing

Brentford.

At Cowley Peachey Junction, the Slough Arm branches off to the west.

It was to become an early example of the type of public reaction against officialdom

portrayed in the Ealing Comedy ‘The Titfield Thunderbolt’, although

here applied to the preservation of a branch canal rather than a railway. By the 1960s, the

brickfields and the sand and gravel pits that the Arm

had been built to serve were worked out and the waterway had become

redundant. In keeping with the fashion of the time, Slough

Council planned to convert part of it into a road. Protest followed,

‘The Slough Canal Group’ was formed, and

following a vigorous campaign supported by the local newspaper (the

Slough Observer) the

Arm was reprieved to re-open as a cruising waterway in 1975.

But for some visitors to Slough,

Betjeman’s unflattering judgment remains apt, leaving one to surmise that

a boater’s only motive in navigating this aquatic cul-de-sac is to

seek moorings.

The entrance to Shackle’s Dock.

Old maps of the Canal ― such as the route maps at the head of this

chapter and those below ― show that many docks and cuts once left

the canal banks, particularly along the main line to the south of Cowley

and the Paddington Arm. Most

have long since been filled in leaving little or no trace of the

waterborne commerce they once supported, which in the Hillingdon

area was mainly brick-making.

Apart from milling, there was no appreciable industry in rural

Hillingdon before the Canal made available the means to transport

deadweight cargoes over distance. This stimulated the exploitation of the area’s brickearth deposits and

during the 19th Century brick-making grew into a major industry.

Eventually some five million bricks a year were moulded and fired in the local

brickfields, and transported by canal from the numerous docks and cuts created to

serve the industry ― such as Otter, Pocock’s, Wilshin’s, Printing

House, Shackle’s, and Yeading docks ― to a distribution yard at Paddington

Basin’s South Wharf. A good deal of Victorian West

London was built from bricks burnt in clamps in the locality, the

bricks containing household ash brought by barge from the refuse

wharves at Paddington to be mixed with the local clay.

――――♦――――

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

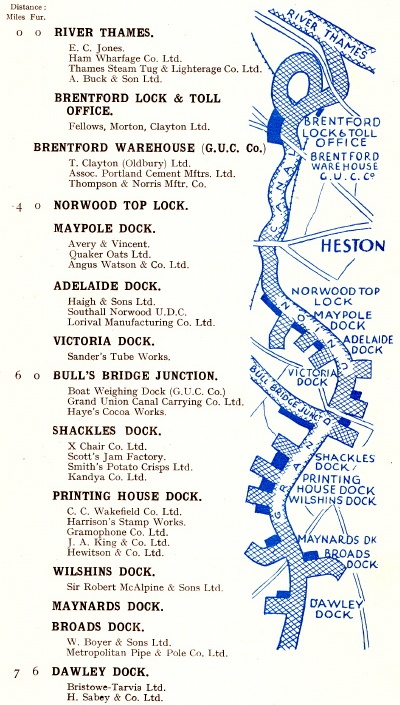

Grand Union Canal route map (c.1938) showing

the wharves and docks that

lay between

St. Pancras, on the Regent’s Canal, and Bulls Bridge. |

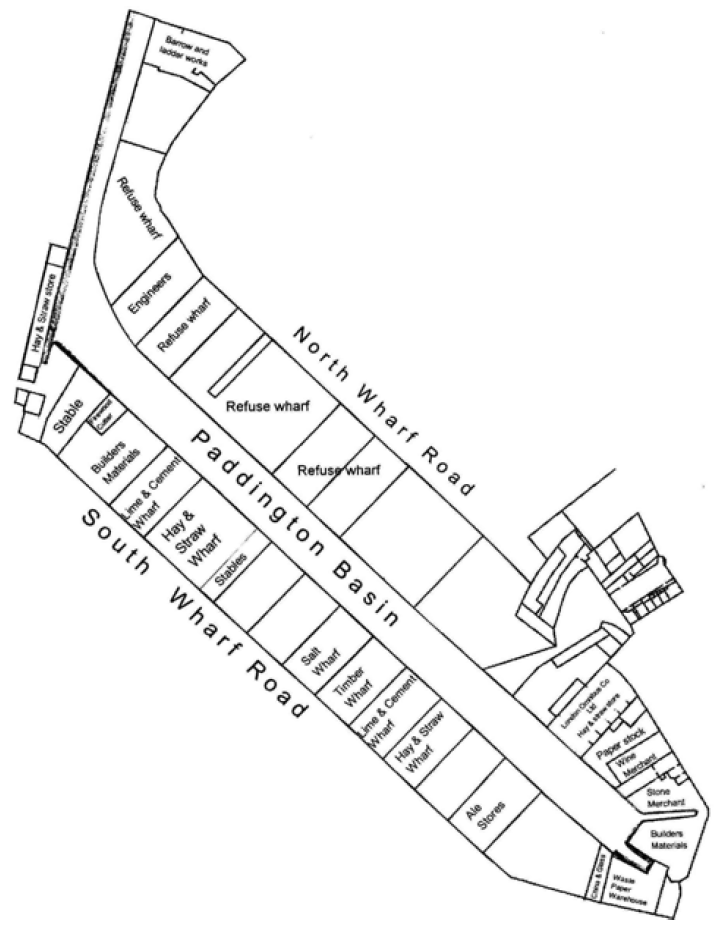

Paddington Basin today ― and in

the 1930s.

The layout

diagram

further down this page shows that the

left-hand wharf was once used for refuse

disposal.

|

|

|

Map showing

Paddington, c.1790. The Westbourne

(in blue)

flows into Hyde Park's Serpentine lake.

|

Bull’s Bridge Junction is at Hayes, some two and a half miles south of Cowley

Peachy. Here commences the Paddington Arm, which

initially heads off in a northerly-easterly direction before

describing a clockwise arc to its destination adjacent to the former

Great Western Railway headquarters at Paddington. Station and canal basin are linked by a walkway that extends across

the station platforms, and also by Praed Street, so named to

commemorate the first Chairman of the Grand Junction Canal Company; and it was at St. Mary’s

Hospital in Praed Street where, in 1928, Alexander Fleming

discovered penicillin, a breakthrough that revolutionised medicine

and earned him a Nobel Prize.

“Although Paddington is now contiguous to the Metropolis, there

are many rural spots in the Parish, which appear as retired as if at

a distance of many miles. From this place a canal has been

made, which joins the Grand Junction Canal at or near Hayes.

It is now finished, and there are noble wharfs for Staffordshire

coal, &c. At the Basin, a passage boat to Greenford Green, and

Uxbridge, sets off daily during the summer months at eight o’clock

in the morning: a breakfast is provided on board, and other

refreshments may be obtained. The terms are reasonable, viz.

five miles for a shilling, ten miles for eighteen pence, and the

extent of this still voyage to Uxbridge may be enjoyed for

half a crown . . . . about three miles west from the Basin, is the

Mitre tavern, situate on the bank of the canal, opposite to a spot,

once of pugilistic note, called Wormwood Common, or more generally

Wormwood Scrubs . . . . A pleasure boat is established by the civil

and attentive landlord of the Mitre, which leaves the Basin of the

canal early in the afternoon, and returns at a reasonable hour in

the evening: in this rural place of accommodation, the refreshments

are excellent.”

A Pocket Companion for the tour of London and its

Environs (1811) |

Looking back at the success of the Paddington Arm, it is surprising

that a branch canal into London was not considered an essential part

of the original scheme, but no such application was included in the

canal Bill placed before Parliament in 1793. It was not until the

following year that Jessop and Barnes surveyed a route. Paddington was probably selected as the terminus due to its

location on the

outskirts of the expanding Metropolis, with good access to the City via

the ‘New Road’, [2] while the line from Bull’s

Bridge was free from the need for locks or substantial engineering.

Indeed, the only challenges were to cross the River Brent near

Alperton and the Westbourne near Paddington, both requiring

significant embankments

across the respective river valleys, the rivers being bridged by

short aqueducts. [3] Maps of the period show Paddington as a village

on the edge of the approaching city, while to its west the Westbourne

(also known as the Westbrook and the Serpentine) meanders into

the Serpentine lake in Hyde Park. When Belgravia, Chelsea and

Paddington were developed, it became necessary to divert this river

into culverts in order to build over it, work that was completed in the

1850s. Since then, the Westbourne has become one of London’s lost

rivers ― in fact, part of its sewage system.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extract from the

Preamble to the Act

authorising

the Paddington Arm

(35 Geo.

III. C. 43 1795). |

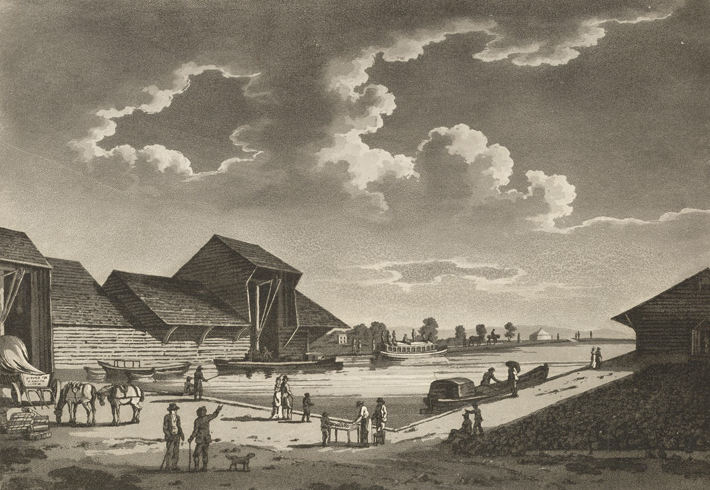

The Company obtained the necessary Act in 1795, but

shortage of funds and a prolonged dispute with the Bishop of

London over the acquisition of land delayed completion of the Paddington Arm until the 10th July 1801, when it opened to

the public

rejoicing that usually accompanied such events (Appendix II). At that time, the Arm crossed open

countryside, passing only an occasional village, such as Harlesden. Its terminus at Paddington was described thus:

“At Paddington a spacious basin or straight cut, 400 yards long

and 30 wide, has been formed with wharfs at its head, and others are

daily extending westwards along its sides; behind this, on the north

side, is a spacious yard for a vegetable and a hay and straw market,

with large sheds, under which loads of those articles can stand in

the dry when it rains; and on the fourth side pens are erected and

provision made for a large cattle market. The number of wharfs

erected on this extensive line and its branches by individuals is

too great for them to be particularized . . . . The market at

Paddington, after an ineffectual opposition from the City of London,

was opened in May 1803 for the sale of fat cattle, hay, straw, corn,

vegetables, &c. . . . In June 1801, packet boats were established,

that continue to pass regularly at stated hours during great part of

the year, for the conveyance of passengers and parcels between

London and Uxbridge; and for some time after the opening of the

Buckingham branch, a boat went regularly between Paddington and that

town; but the number of passengers and parcels was found inadequate

to support the expense. . . . Mr Pickford has a great number of

boats, which proceed as regularly day and night upon this canal, and

the other canals north of it, as the mail coaches do on the roads,

although with less expedition. A common trading boat has been

known to arrive at Paddington in 63 hours from Coventry.”

The Political State of the British Empire (Vol 3),

John Adolphus (1818)

Much of the traffic in those early years consisted of inbound

cargoes of hay, straw and

agricultural produce, with outbound cargoes of manure and other

city waste (used as a crude agricultural fertiliser), but bricks,

sand, gravel and other building materials were to become one the

Arm’s staple cargoes during the years when London was expanding. Sand

and gravel pits, and brick kilns ― fired by coal shipped by canal

from the Midlands ― proliferated at Hayes, West Drayton, Iver and

Langley.

An artist’s impression of

Paddington Basin as built.

――――♦――――

|

The Regent’s Canal at Camden ― the

London and North Western Railway Interchange Warehouse.

The warehouse has a canal basin

beneath it, its entrance being spanned by a fine cast iron towing

path bridge (J. Deeley & Co Iron Founders Newport Mon) dating from

c.1846 ― the warehouse (Grade II Listed) dates from c.1896. Of

four storeys topped by handsome chimneys, its multi-coloured stock

brick walls with blue engineering brick dressings, cast-iron windows

with small panes and a modular pattern of repeating window bays,

combine to give the building a strong period industrial character. |

When the Regent’s Canal was finally completed in 1820 ― it

opened in two

stages due to its construction costs being seriously underestimated

― it extended the Paddington Arm around the City

to the Port of

London. As a consequence, Paddington Basin lost much of its business to

new wharves and docks that were better

placed for the delivery of goods to customers’ premises:

“At its first opening, passenger boats went about five times a

week from Paddington to Uxbridge; and the wharves at Paddington

presented for some years a most animated and busy appearance, on

account of the quantity of goods warehoused there for transit to and

from the metropolis, causing the growth of an industrious population

around them. But this was only a brief gleam of prosperity, for when

the Regent’s Canal was opened, the goods were conveyed by barges

straight to the north and eastern suburbs, and the wharfage-ground

at Paddington suffered a great deterioration in consequence.”

Old and New London: Volume 5 (1878)

In particular, much of Paddington Basin’s prosperity was captured by

the new basin at City Road:

“At the wharf of Messrs. Pickford and Co., in the City Road, can

be witnessed, on a larger scale than at any other part of the

kingdom, the general operations connected with canal traffic. This

large establishment nearly surrounds the southern extremity of the

City Road Basin. From the coach-road we can see little of the

premises; but on passing to a street in the rear we come to a pair

of large folding gates opening into an area or court, and we cannot

remain here many minutes, especially in the morning and evening,

without witnessing a scene of astonishing activity. From about five

or six o’clock in the evening waggons are pouring in from various

parts of town, laden with goods intended to be sent into the country

per canal. In the morning, on the other hand, laden waggons are

leaving the establishment, conveying to different parts of the

Metropolis goods which have arrived per canal during the night.”

From

The Penny Magazine (1842)

Barges being towed

through Regent’s

Park during the 1930s

― the first two carry coal, the third appears to be timber.

The tug Brent ― built by

Bushell Brothers at Tring in 1928 ― undergoing trails on the

Regent’s

Canal hauling three 90-ton barges.

Photos courtesy of Miss Catherine

Bushell.

Even though trade on the Regent’s Canal had begun to decline by the late 1930s, City

Road Basin continued to do a substantial amount of business . . . .

“There is much activity at City Road basin, which adjoins the

City Road, where there are numerous wharves at which are handled

timber of all classes, harvesting machinery, coal, waste paper and

chemicals. A feature of the Basin is the depot belonging to

Messrs. Fellows, Morton and Clayton Ltd., from which a daily service

of motor-driven barges operate.”

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material, c.

1938

. . . . and the Canal in general remained busy, although closure of

the small power stations it serviced following Battersea A coming on

stream during the mid-1930s resulted in a considerable reduction in

its coal traffic:

“Traffic on the Regent’s Section can be divided into two

categories. First there are canal boats which receive their

cargoes from steamers in the Regent’s Canal Dock and other

London docks, and proceed up the Grand Union Canal to the Midlands.

Secondly, there is the barge traffic which comes in from the River

Thames, or receives cargoes from ships in the Dock destined for

wharves in the London area. Hundreds of thousands of tons of

merchandise pass along this section of the Canal, comprised chiefly

of coal, timber, straw-boards, iron, building materials and oils.”

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material, c.

1938

|

An interesting view of the Regent's Canal showing the

construction of the London & Birmingham Railway in progress in May, 1837.

This view shows the bowstring bridge ― probably designed by Charles

Fox (later Sir) ― on the Euston extension.

The drawing is one of the series of the railway under construction,

by John Cooke Bourne. |

――――♦――――

|

Layout of Paddington Basin in 1891

― the Hay & Straw Store survives as offices. Large amounts of

refuse were shipped from the refuse wharves, much of it being used

to fill worked out pits and redundant docks. An account of

this unsavoury business is given at

Appendix III. |

Considering the damaging impact that railways were to have on the

canal system, it is ironic that the opening of Brunel’s Great Western

Railway terminus at Paddington in 1838 led to Paddington Basin

regaining some of its former importance as a transport interchange.

By the late 1930s, Paddington Basin still had seventeen tenants,

including Shell Mex and wharves for the borough councils of

Paddington and St. Marylebone, from which:

“Large quantities of parish refuse, collected from the

neighbouring districts, are loaded onto craft in Paddington Basin,

and disposed of at various points on the Long Level. Sand from

Leighton Buzzard, and building materials from other points on the

Canal, are brought by canal boat into Paddington Basin for

distribution by lorries to all parts of London. Timber and

iron from steamers in the River Thames is also dealt with in the

Basin.”

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material, c.

1938

The

Paddington Arm had been a catalyst for the development of

north-west London, with many businesses realising its transport

potential, including the inevitable gas works (at Southwell and

Kensal) ― large consumers of coal and exporters of coke and tar ―

and businesses dealing in timber, glass, cement and tiles. At

Kensal Green:

“. . . . is situated another of the Gas, Light and Coke Company’s

stations, coal for which is brought by canal barge from steamers

discharging in the Regent’s Canal Dock. In addition,

large quantities of coal are brought from the London, Midland and

Scottish Railway, whose tips are at Mitre Wharf . . . . Another

electricity station of the London Power Company is situated at

Willsden, and is supplied with coal conveyed by canal boats from the

several Warwickshire collieries.”

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material, c.

1938

|

|

|

The Heinz wharf at

Harlsden |

In its

later years, household names such Heinz, J. Lyons, Glaxo, Rockware

Glass and Guinness built factories and wharfs on its banks.

Built in 1925, the Heinz factory was located at Harlsden on a

20-acre site, but owing to the demand for its tomato soup, baked

beans (which had previously been shipped from North America) and a

range of other food products, the site eventually more than doubled

in size. Its long canal frontage permitted loading bays to be built

to handle the raw beans and tomato puree that arrived by barge from

the London docks, and to export finished goods by the same route.

The firm ceased using canal transport in 1967. Despite major

investment in the factory, the growth of supermarket own-brand

products and the harsh economic climate of the 1980s led to a

decline in business, and the Harlsden plant closed in 2000.

The Guinness brewery at Park Royal was situated on the Paddington

Branch southeast of Alperton, a canal-side location that enabled

the firm to manufacture its product close to market, while being

able to obtain a large brewery site at relatively low cost. Guinness

relied on the Canal for transporting its barrels of stout into

Paddington for distribution to its London outlets, also further

afield to the Grand Union Canal Company’s distribution centre at Sampson Road

wharf in Birmingham. Empty barrels were carried in

return. To maintain the Birmingham run’s tight schedule, the

boats were four-handed to allow the crews to complete the round trip

in a week. But the exceptionally heavy winter of 1946-47 froze

the Canal, bringing traffic to a standstill for many weeks, and

Guinness transferred their distribution to road transport.

At Greenford, a glass works was opened by W. A. Bailey in 1900 to

exploit the Canal’s location. Not only did the Canal provide

transport for the bulk materials needed for glass making, it also

provided smooth transport for the fragile goods produced. The

company was later incorporated within the Rockware Glass which, in

1919, also redeveloped the site of an adjacent white lead works, the

Purex Lead Company, which had been used for munitions production

during the WWI. Rockware’s Greenford factory stood on the

south side of the Canal and remained in production until 1973.

|

|

|

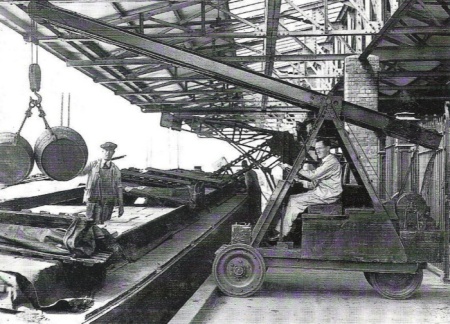

The dock of J.

Lyons at Greenford. |

J. Lyons Ltd. had their factory at Greenford. Opened in 1921, at its

peak the factory employed 300 people. Lyons equipped their canal

dock with the latest cargo-handling facilities enabling several

barges to be discharged simultaneously. Their consignments were stored under excise control before

being released for use in tea blends, coffee, confectionery and

grocery lines (tomato sauce, salad cream, jellies, custard powder

and mixes). So proud was the firm of their dock and warehouse that

they were proudly shown to the King and Queen during a royal visit in

1923.

Hayes Bridge Wharf and the yard of James

Davies (Timber) Merchants Ltd.

Some of the barge names and

owners are listed at Appendix IV.

|

|

|

The Nestlé factory

at Hayes. |

Many factories such as these were built close to the Canal because

they ran heat-dependant processes, such as brewing, malting, food

preparation, brick, tile and glass making. In an age before

oil, gas and electricity became economic alternatives for heating, their

boilers were fired with coal, which was transported cheaply by canal from the

Midland collieries. One

such customer was the Nestlé factory at Hayes, known to boatman as the ‘Hayes Cocoa’ after

its former owner, the Sandow Cocoa Company. For many years the

factory received regular consignments of coal by canal until

eventually it converted to oil fired boilers, and the last load of

coal was delivered from Cannock in 1959. Visually, the

factory’s canal frontage has nothing to recommend it, but its main

entrance ― facing away from the Canal ― is an attractive piece of Art Deco. A Wallis

Gilbert creation, it is framed with trees and set back behind lawns

with massive railings and gates imported from the company’s main

works in Switzerland. Wallis, Gilbert and Partners were responsible

for the design of many buildings in the Art Deco style during the

inter-war years, their best known creations being the Hoover Factory

on Western Avenue, Perivale (1931-1938), and the Victoria Coach

Station (1931-32).

Another regular customer for canal-delivered coal was the firm of

Kearley & Tonge, later to become International Stores and one of the

first modern supermarket chains. Known as the ‘Jam Ole’ to boatmen,

the factory’s coal shipments were landed at Rubastic Dock (now

filled in) on the Paddington Arm from collieries around Atherstone

on the Coventry Canal. International Stores (since absorbed

into the Somerfields empire) was immortalised together with two other

long-forgotten grocers in a verse from John Betjeman’s poem Myfanwy:

|

“Smooth down the Avenue glitters the bicycle,

Black-stockinged legs under navy blue serge,

Home and Colonial, Star, International,

Balancing bicycle leant on the verge.” |

Kearley & Tonge opened their jam and marmalade factory at Southall

in 1913, later extending their business into a wide range of food

products. The Jam Ole Run ― some 246 miles and 194 locks ― could,

under the most favourable conditions, be completed in seven days. Time was

important, for the crews were paid by tonnage and the quicker they

arrived to unloaded, the quicker they could return for another load. But by the late 1960s the Jam Ole was struggling and the last cargo

of coal, from Baddesley Colliery at Atherstone, was delivered in

1970, [4] so ending nearly two centuries of carrying coal to London by

canal:

“I had a real nice stone jam jar from the Jam-’Ole. You went

right in and under the bridge to deliver coals at the Jam-’Ole. It

had its own big basin, tooked two pairs of boats and two big barges. All gone now, just cars were the water used to be. They used to be everso perticler at that jam factory, one little chip in a jar, out

it were throwed on their roobish ’eap. We used to ask if we could

have it, specially if it were one of them deep-blue and some stone

ones. Crammed with flowers on yer cabin top you never noticed no

chips. Lovely!”

Ramlin Rose by

Sheila Stewart, Oxford University Press (1994)

――――♦――――

Before leaving Bulls Bridge Junction, a

further once-important canal tenant needs to be mentioned. This was the Grand Union Canal

Carrying Company, which following nationalisation in 1948

was absorbed into British Waterways’ carrying fleet. [5]

The Grand Union Canal Company’s carrying subsidiary was formed in 1934, and Bulls Bridge Junction became the location

of its slipways, repair yard and traffic control office. [6] A

recess in the canal bank of a couple of hundred yards in length,

was built as a lay-by where boats awaiting instructions could tie up, end-on, without

obstructing the channel. Photographs of the period show the lay-by

tightly packed with empty narrow boats moored by their sterns to

iron rings set into the concrete wharf, the boatpeople occupied with

polishing their brassware, hanging out their washing, refuelling or

just relaxing over a pipe of tobacco while their children played on

the wharf.

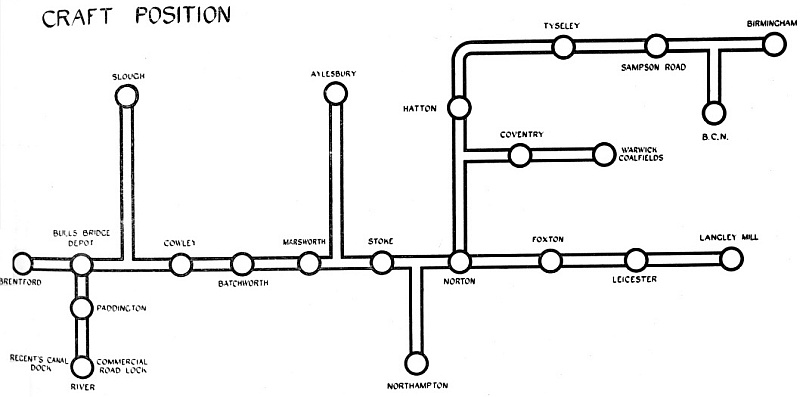

The role of the traffic control office was to accept orders and

allocate shipping instructions to boat crews. It also kept track of

the location of each boat and its activity by means of positioning

coloured discs on a large wall-mounted network diagram (Appendix

V). By repositioning the discs

on receipt of telephoned daily updates, it was

possible to identify slow-moving and stationary boats, as well as

estimate what carrying capacity would be available at any loading

point, and when. In this way the fleet was managed, no mean

achievement in the days before cell phones.

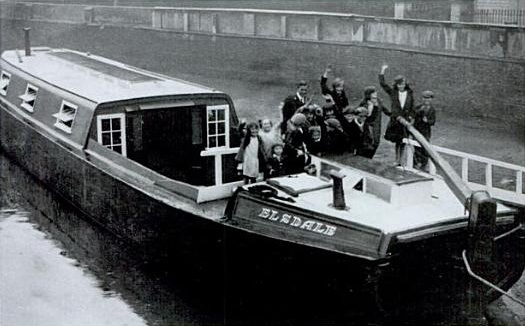

|

|

School barge Elsdale. |

Bulls Bridge depot also hosted a five-bed maternity unit [7] and a

school. The school was opened at Rickmansworth in 1930 for the

benefit of boatmen’s children, but later moved to West Drayton and

finally to Bulls Bridge. Housed on a barge provided by the

Company, the

Elsdale could take about 40 children who were provided with

brief periods of education while their parents were awaiting orders. By 1939 the Elsdale had become unsound and was hoisted onto

the canal bank where schooling continued alongside the depot

buildings until the 1950s.

By the end of WWII., canal carrying was in terminal decline. Although some independent carriers soldiered on until the 1970s, the

business’s financial losses coupled the harsh winter of 1962-3, when

the canal system was iced over for many weeks, caused British

Waterways to cease its carrying operations. Today, the Bulls Bridge

depot hosts a Tesco supermarket and car park, but one of the

Carrying Company’s

dry docks has been retained as a memento of a bygone trade while

the lay-by is now home to an estate of strikingly odd-looking house

boats.

――――♦――――

South of Bulls Bridge the Canal continues through an industrialised

area, but very few of the

many wharves, cuts and docks from the Canal’s commercial era survive, for having

fallen into disuse they were filled in with London’s refuse,

shipped, ironically, by canal from Paddington.

The Ordnance Deport at Weedon Bec was not the only gunpowder

magazine to be served by the Canal. In 1811, the government decided to

replace the old powder hulks [8] moored in river estuaries with

permanent storage facilities. Four new magazines were built, one

being on a 47 acre site on the Canal at North Hyde. Acquired in 1813,

the site was originally planned to connect to the Canal

via a branch that would also form a defensive loop, in contrast toWeedon Bec,

which was surrounded by a high wall with sentry posts. For

some reason the plan for a moat was abandoned, and what resulted was an

extensive branch canal, most of which ran parallel to the main line,

and from which six docks extended at right angles. A barracks

building was erected that could accommodate three officers and 50

other ranks, and mounds were built on the site to deflect the blast

should there be an explosion. Gunpowder was shipped in

government-owned barges that entered the site through a 14ft wide

stop-lock.

The North Hyde Ordnance Depot had a short life, being sold by

auction in 1832. A contemporary newspaper advertisement stated that it

comprised:

“. . . . an entire frontage of about 2,500ft to the Grand

Junction Canal with which the Ordnance canal on this land has direct

communications. The extensive and valuable magazines, mixing houses,

cooperages, boat houses, watch houses and other buildings standing

upon this lot . . .”

The Times, 5th March,

1832

Also put up for sale were the barracks, parade ground, a “capital

dwelling house” (formerly occupied by the Ordnance Storekeeper)

and “ten cottages, with a garden to each, occupied by the foreman

and labourers”. Following the sales, the barracks building became an orphanage

and the branch canal a wharf to a brick works ― in which

the working conditions of the children it employed were grim. A police

officer stationed at North Hyde stated that those who worked there

were:

“. . . . very rough in manner and coarse in language, and

terribly given to drink, but I have always found them honest and

reasonable to deal with; . . . . I often wonder that the children

can stand the work as they do, but nothing seems to hurt them; they

are as hardy as ground toads, as the saying is; yet I have seen them

so tired at the end of the day’s work that the men have had to take

them up in their arms to carry them home.”

Children’s Employment Commission – Brickfields,

1866

――――♦――――

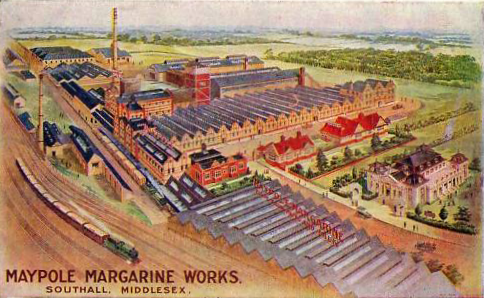

By

the 1930s all trace of the military depot and its canal had been

obliterated, but a nearby private canal branch that has managed to

survive is the Maypole Dock. Described by its current owners as a

“community of moorings with gardens”, in its heyday it served

one of the largest margarine factories in Europe.

In 1869, the French Emperor, Napoleon III, offered a prize to anyone

who could make a satisfactory substitute for butter, suitable for

use by the armed forces and the lower classes. The French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès invented a substance he named

‘oleomargarine’, which quickly became shortened to ‘margarine.’ In

1894, Otto Monsted, a Danish margarine manufacturer, built a large

factory at Southall to manufacture this ‘poor man’s butter’.

Named the Maypole Dairy, it eventually became one of the largest

margarine manufacturing plants in the world, occupying a 68 acre

site that included its own covered canal dock. The Maypole

Dairy Company (later acquired by Unilever) closed in 1925,

apparently due the prohibitive cost of altering production from

barrels to pre-packaged

cartons. [9] Much of the site was sold off, one later tenant being

Quaker Oats who opened its works in 1936 to produce cereals, pig,

and poultry foods, the grain being shipped from the docks mainly by

canal. Jack Gaster, a Thames boatman, recalls taking cargoes to

Maypole Dock shortly after the outbreak of WWII:

“. . . . the job I liked most was being Wharf Bosun up on the

Grand Union Canal at Southall where I was responsible for delivering

canal barges to Messrs. Poulton & Noel [10] laden with Navy beans to be

turned into baked beans. I used to collect the craft from Brentford

Dock and tow them up to Southall behind a horse; there were a number

of locks to negotiate including the Hanwell Flight. This was a

series of seven locks one after the other and needed a little skill

in controlling the barge in order to prevent damage to the lock

gates. Once these had been negotiated and the craft were safely in

the Maypole Dock, it was a matter of uncovering and removing the

hatches and leaving the work force to remove the beans. The dock was

roofed over so that there was no need for my presence until it was

time to bring the barge away and return it down to Brentford Dock

for return to the river.”

WWII People’s War, BBC

――――♦――――

|

|

|

Turner’s post mill

at Southall. |

A

short distance from Maypole Dock the Canal reaches Norwood top lock

(No. 90), which marks the beginning of the its final descent to

Brentford and the River Thames. In this section the canal enjoys a brief respite

from the industrial landscapes of Uxbridge and Hounslow as it skirts

the perimeter of Osterley Park before completing its journey at

Brentford, once a busy river port, which was also served by a

competing branch of the Great Western Railway.

The construction of the Great Western and Brentford Railway

Company’s branch line gave birth to ‘Three Bridges’ ― or ‘Windmill

Bridge’ as it is referred to locally ― a rare example of a triple

crossing in which a road (Windmill Lane) crosses a canal aqueduct

which crosses a railway, all at the one point. Brentford Dock and

its branch railway are generally considered to be Isambard Kingdom

Brunel’s last significant engineering project, being completed

shortly after the great engineer’s death in 1859. The construction

of a branch line southward from Southall to Brentford Dock required

the Canal to be crossed at a point where it was already crossed by

Windmill Lane. Brunel’s solution was to drive a cutting for his

broad gauge railway beneath the canal, which he placed in a cast

iron trough, while a new cast iron bridge was built to carry

Windmill Lane over both.

|

|

|

Three Bridges,

Hanwell ― the Canal crosses the railway

in an 8 ft-wide

cast-iron trough

aqueduct. |

As the name of the lane suggests, this engineering oddity stands

near the spot where a windmill once stood and which attracted the

attention of a local Brentford artist, Joseph Mallard William

Turner. Turner exhibited ‘Grand Junction Canal at Southall Mill,

Windmill and Lock’ in 1810, his painting depicting a post mill, its

sails at rest and a pair of millstones leaning against its

roundhouse wall. In the foreground a narrow boat is locking up, two

men pushing hard against the balance beams of the lock gates while

canal horses graze idly on the canal bank in this idyllic scene. The

lock is thought to be Hanwell top lock (No. 92), the bridge in the

background being that which carried Windmill Lane across the Canal.

The Great Western Railway branch line through Three Bridges once

terminated at

Brentford Dock, [11] which lies adjacent to and slightly upstream of the

point at which the canalised River Brent enters Brentford Creek to

join the Thames.

Brentford Dock was constructed between 1855 and 1859 to a plan by

Brunel. The dock, which was served by a large railway marshalling

yard, warehouses, workshops and goods sheds, was designed as a

transhipment terminal for traffic carried by barges and lighters

from the London docks, the Great Western Railway and the Grand

Junction Canal. Through most of its

existence it was a commercial success, the traffic it handled

including coal, steel, timber, wood pulp, flour, animal feedstuffs,

cork and general merchandise. But by the 1960s, the development of

the motorway network and its greatly increased use for road haulage

took traffic away from the Thames, and Brentford Dock gradually fell

into disuse. The dock closed in 1964 and the site has since been

redeveloped with housing and a marina.

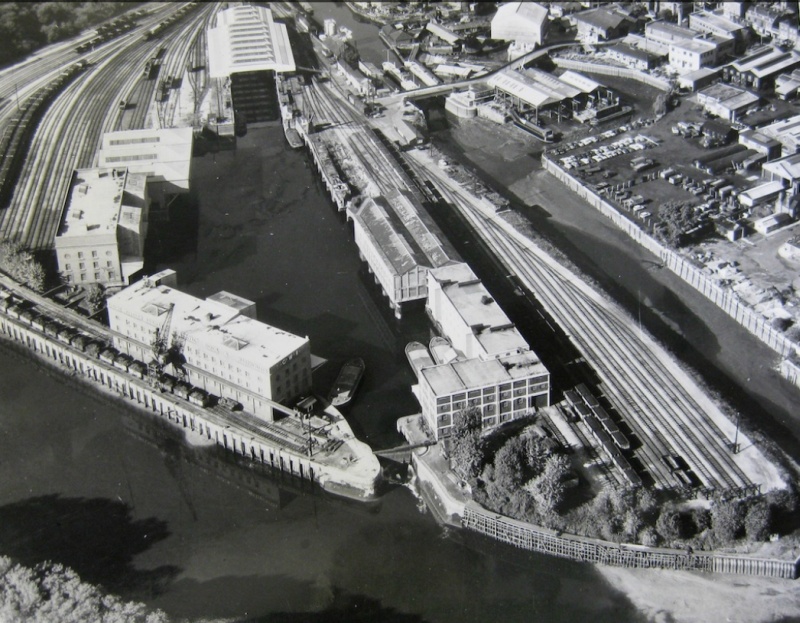

Brentford Dock. Brentford Creek,

leading up to Thames Lock and the start of the

Grand Junction Canal, is on the right of the picture.

――――♦――――

Just

to the east of Three Bridges commences the Hanwell flight of six locks

that lower the canal by just over 53 feet within a third of a mile.

Along this section runs a high brick wall behind which were

the extensive grounds of what was once the County Asylum, now

Ealing Hospital. A bricked-up entrance shows where boats once passed

into what the boatmen called ‘Asylum Dock’ to deliver coal for the

boilers and take away fruit, vegetable and animal produce

cultivated by the inmates in the Asylum’s large market gardens. For

its time, the medical regime took an enlightened attitude to the

care of their patients by encouraging the use of their skills and trades. This

‘therapy of employment’ benefitted both the Asylum and the patients,

and was a precursor to what we know as ‘occupational therapy’.

|

|

The Company’s steam

inspection launch ‘Swift’ descending the Hanwell flight. |

An

old enemy of canal transport, ice. These pictures are of the Canal at Hanwell during the winter of 1962-63.

.JPG)

The former County Asylum lay behind the imposing wall

on the towing path bank.

.JPG)

.JPG)

At Hanwell bottom lock (No. 97), the

Canal flows into the River Brent:

|

“Gentle Brent, I used to know you

Wandering Wembley-wards at will,

Now what change your waters show you

In the meadowlands you fill!

Recollect the elm-trees misty

And the footpaths climbing twisty

Under cedar-shaded palings,

Low laburnum-leaned-on railings

Out of Northolt on and upward to the

heights of Harrow hill.” |

The Canal flows into the River Brent at

Hanwell bottom lock, which becomes a canalised river.

So wrote the late Poet Laureate, Sir John Betjeman, of the River

Brent as it

flowed towards Brentford and the Thames. Much of the river

north of this point has since been driven underground by the

suburban growth of London or corseted in concrete as a flood

protection measure. The risk of flooding here is real, and it

came to pass in 1841.

Some

6 miles to the north of Brentford lies the Brent Reservoir. Built by

the Regent’s Canal Company in 1835 to address a water shortage on

the Paddington Arm and the Regent’s Canal, the reservoir straddles

the boundary between the London boroughs of Brent and Barnet. Early

in the morning of the 17th January 1841, a sudden thaw following

freezing weather caused the reservoir to burst its earth wall. A

disastrous flood then swept down the Brent into the Canal to descend

on Brentford, ripping barges from their moorings and leaving much

destruction in its wake . . . .

“. . . . a few minutes before four o’clock a loud noise was heard

to the north of the town, which momentarily approached nearer and

nearer; and it was soon ascertained that the narrow stream of the

Brent had swollen into a mighty river, and overflowing its banks,

was pouring itself into the already increased waters of the canal.

Numbers of boats, barges, and lighters, were instantly torn from

their moorings, and driven with great force through the bridge,

towards the Thames. At the same instant, also, the accumulated

waters having overflowed all the premises north of the high road,

burst with frightful force through two avenues by the houses . . . .

It is impossible to describe the scene at that moment. Men, women,

and children, many of them in their night clothes, were running in

all directions for places of shelter, while the roaring of the

water, added to the screams of the terrified inhabitants of the

boats, and of the individuals inhabiting the numerous cottages

running south of the town down to the water side, were most

appalling. In a very short time, all the houses at that portion of

the town were flooded . . . . five large barges were driven by the

force of the water against the wharf of Mr. Fowler, an extensive wharfinger at Brentford-end, and swamped, some lying over others. .

. . but it was nearer to the mouth of the outlet of the Thames that

the greatest damage was done, and a scene of shipwreck unparalleled

so far inland presented itself. The spot in question is at the

bottom of the Boar’s Head yard, a turning leading from the high

road, nearly opposite to the market-place, down to the canal. Off

this spot the canal passes through some meadows, and there is a foot

bridge across it, and near that bridge were piled up craft of

various descriptions to the number it is said of fifteen. There

would no doubt have been more, had not the pressure of the water

forced down a large portion of the wall of the grounds of the duke

of Northumberland, by which the pent-up water obtained an outlet,

carrying with it four or five barges. Some of these vessels were

topsy-turvy, others were on their sides, and portions of five could

he distinctly seen above the water, piled on the top of each other.”

The Annual Register,

1841

Despite the scene of destruction painted by the press reports of the

time, the loss of life was surprisingly small, with two deaths

reported.

――――♦――――

This bypass weir at Osterley Lock is one of

a number that

regulate the depth of the

canalised River Brent.

The

River Brent with its weirs and mills was probably unnavigable until

work started on the Canal in 1793, which, apart from

its wider bends, canalised the River along the south-western

boundary of New Brentford. Here, the scenery returns briefly to parkland as the Canal skirts the estate of

Osterley House, an elegant eighteenth

century neo-classical mansion by Robert Adam, now in the care of the

National Trust. The scenery is somewhat blighted by the M4, which

the Canal passes beneath before reaching Clitheroes Lock (No. 99),

[12] the last conventional lock on the canal; the two that remain are

electrically operated and are twinned, Thames Lock (No. 101) also

being tidal and in the care of a lock keeper. Clitheroes Lock is but

a short distance to Brentford Basin, at the southern end of which is

Brentford Gauging Lock (No. 100). This was the first (or last) lock

on the Canal when it was first opened, and it continues to act as the

demarcation point between the Thames, administered by the Port of

London Authority, and the River Brent/Grand Union Canal,

administered by the Canal and River Trust. The section of Canal between

these two locks is semi-tidal due to high tides causing the Thames

to overflow Thames Lock weir back into the Canal.

Brentford Basin was once ringed with wharves and warehouses, and a

hive of commercial activity. [13] Here the transhipment of cargoes

between lighters, river barges and smaller canal craft took place. Tolls were paid at the Brentford Toll Office based on the weight and

type of cargo, the toll clerk measuring how high a loaded boat was

‘sitting’ out of the water using a gauging rod to measure the ‘dry

inches’ on the side of the boat. From this could be calculated the

toll based on the charge per mile for each cargo. Although much of

this industrial landscape disappeared after the Canal’s commercial

life ended in the 1970s, and is currently the subject of various

regeneration plans, the Basin is not deserted, for many leisure

craft now pass through it. It is ironic to reflect on British

Waterways’ view, published in their house magazine in 1958, that the

development of pleasure boating “will not mean greatly increased

earning in the kitty and our main efforts must always be directed

towards getting commercial traffic”. It was to be another decade

before Barbara Castle’s 1968 Transport Act finally gave official

recognition to the recreational value of our inland waterways and a

remit for British Waterways to develop their leisure potential.

.JPG)

.JPG)

|

Pictures of Brentford Basin during

the dreadful winter of 1962-63:

the timber being worked (above and below) was

destined for James Davies

(Timber) Merchants Ltd. at Hayes Bridge on the Paddington Arm. |

.JPG)

Brentford Gauging Lock (No.

100) in the background.

.JPG)

The narrow boat Nutfield playing

tug to a lighter

load of timber - the Nutfield is still around.

――――♦――――

|

|

|

Boatmen’s

Institute, Brentford. |

Before leaving the area of Brentford Basin, a further point of

interest is the former Boatmen’s Institute. Canal boatmen had a hard

and poorly paid existence, the railways having creamed off their

most profitable trade leaving mostly coal and

other low-value deadweight cargoes. Bringing up families in tiny narrow

boat cabins was a struggle and it is unsurprising, considering the

dangerous nature of the trade, that there was a high rate of

mortality, particularly among children. Few boat people could

swim and drowning was not uncommon. Many canal families were illiterate, their itinerant lifestyle

denying them regular schooling, while access to medical help and to

religion were difficult. Thus, for many the Brentford

Boatmen’s Institute was a beacon where children could be left for

weeks at a time to receive a rudimentary education while their

parents carried loads to Birmingham and elsewhere on the network. The Institute even had

lying-in rooms where women could give birth in dignity. For

one old boatman, the Institute was “the happiest, blessedest place in

Brentford”.

The Institute was designed by local architect Nowell Parr in

1904 for

the London City Mission, which had many much larger premises devoted

to sailors in the East End docks. This charming building is in a

redbrick Queen Anne style, with white, rough-cast upper floors and

wide, flat buttresses. For 50 years tea and

compassion were dispensed to the canal community within its walls, but when

canal traffic faded

away so did its role in life. The building became redundant

and, at the time of writing, is now a private dwelling.

――――♦――――

Thames Lock (No. 101) at

Brentford.

The double Thames Lock

forms the boundary between the Thames, administered by the Port of

London Authority,

and the River

Brent/Grand Union Canal, administered by the Canal & River Trust.

A view in the opposite direction

to that above ― the tidal Brent Creek, with the River Thames in the

distance.

South of Brentford Lock (no. 100), boats had at first to navigate the tidal

Brentford Creek because local millers frustrated its use to build another lock to enable canal traffic to continue

further on its way. But in 1802, some years after this section of

the Canal had opened, the Company succeeded in building the first

Thames Lock [14] to provide improved access with the Thames.

Today, the town of Brentford is no longer an important trading

route. Its dock has been redeveloped as a marina surrounded by

flats, maisonettes and houses, while the western side of the canal

basin is currently the subject of planning applications for

redevelopment. Large commercial developments dominate the Great West

Road. But in the eighteenth century, it would appear,

Brentford was an unappealing place; and despite the Turnpike Trust, the state of the road was extremely bad:

“Though this is called the county town, it is a miserable dirty

place, without a town hall, or any building of that nature . . . .

The road from Hyde Park corner through Brentford and Hounslow is

equally deep in filth, as the road from Tyburn through Uxbridge. The

only passable track of which, during the whole of the winter of

1797-8, was eight inches deep in fluid sludge, the rest of the road

being from one foot to eighteen inches deep in adhesive mud.

Notwithstanding His Majesty travels the road several times every

week there are not many exertions made towards keeping it clean in

winter.”

View of the Agriculture of Middlesex,

John Middleton (1807)

The great lexicographer, Doctor Johnson, took an equally

jaundiced view of the town. So let the last word on this journey

from Braunston to Brentford ― and a judgment that must rank with

Betjeman’s on Slough ― rest with the Doctor:

“I once reminded him [Johnson] that when Dr Adam Smith was

expatiating on the beauty of Glasgow he had cut him short by saying,

‘Pray, Sir, have you ever seen Brentford?’ and I took the liberty to

add, ‘My dear Sir, surely that was shocking.’ ‘Why then Sir,’ he

replied, ‘YOU have never seen Brentford.’”

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D,

James Boswell (1791)

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

THE KILBURN AQUEDUCT AND EMBANKMENT

“About the year 1798, the proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal

made the Paddington branch of their navigation; its approach to

London rendered two very great and elevated embankments necessary,

one over the River Brent, the other over the valley of the

Serpentine River [a.k.a. the Westbourne], near Westbourn Green. The first of these

embankments was effected by making a brick aqueduct, of large

capacity, under which the Brent passes generally without much

impediment, and which is too far removed from London to be much

dilated upon here; but the latter embankment essentially interferes

with that great object of consideration, the sewage of the western

part of the metropolis. It is formed over the valley to an elevation

of 30 feet above the natural surface of the ground; a brick aqueduct

here, as at the River Brent, being made for the conveyance of the

canal over the Serpentine River or Westbrook. This brook receives

all the waters flowing from the western side of Hampstead Hill, the

south side of Shootup Hill and Bransbury, Kensal Green, in part, and

thence from the eastern side of the Harrow Road to the bridge at

Westbourn Green. This district being all strong clay, floods, which

were frequent before the embankment, have increased since its

formation; no doubt owing to the limited size of the culvert, the

opening being but a little larger than the old bridge was on the

Harrow Road, which has since been rebuilt on account of want of

dimensions. What evil might arise from the effects of a very sudden

thaw cannot easily be foreseen; because, if the embankment were to

be ruptured so as to let out the waters of the canal, which is for

18 miles without a lock, they could not be stopped, although there

are stop-gates at the bridges, for they could not be made to act if

there were any great thickness of ice in the canal.”

Some account of the proposed improvements of the western part of

London (1814) – pp.60-61.

The author of this piece may have been aware of the problems

experienced with the Cosgrove embankment and aqueduct.

The aqueduct referred to here is the Kilburn Aqueduct. Sited where

the Canal crosses the Westbourne Valley, the aqueduct still

exists ― approximately where the footbridge west of Little Venice

crosses the Canal today ― but lies buried beneath London’s later development

(and at any rate who would want to live next door to an open

sewer?). In

appearance, the aqueduct was probably not dissimilar to that which Jessop

designed to support the massive embankment across

the Great Ouse at Wolverton, but in this case of a single arch.

Today the aqueduct still conveys the Serpentine, now

generally known as the Ranelagh sewer.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

OPENING THE PADDINGTON ARM

reported in The Morning Post, 11th July,

1801.

“The canal to Paddington was opened yesterday morning for trade, with

a grand procession along the Paddington Line to Bull’s Bridge at

Uxbridge. Exactly at nine o’clock the Committee, with their friends,

in two pleasure boats, set sail, with colours and streamers flying,

each vessel being towed by two horses. At twelve o’clock the company

were met at Bull’s Bridge by the city shallop (having on board the

Sub-committee of the Thames navigation), and several pleasure boats,

with large parties of Ladies. ― On meeting, a salute was fired, and

then the procession returned in the following order:

1. The Committee and their friends, in two barges, with the

Buckinghamshire band of music.

2. The city shallop.

3. Seven pleasure boats.

At half after five o’clock, the cavalcade reached the Great Dock.

This was announced by the firing of cannon, on Westbourn-green-bridge,

and a volley of musquerry (sic) from the town. After three huzzas,

the company landed, and walked in procession to the Yorkshire Stinge,

preceded by the Buckinghamshire band, playing ‘God save the King’.

At half past six, the company sat down to an excellent dinner, and

spent the evening with conviviality.

Blue and purple ribbands were worn by the ladies, gentlemen, and men

employed in the concern, on which were written, “The Marquis of

Buckingham, and success to the Grand Union Canal.”

Great praise is due to the Committee for the expedition which they

have used since last spring in completing the canal. A long range of

warehouses are nearly finished for the reception of goods. Yesterday

not less than eight laden barges arrived. A public road, 100 feet

wide, was finished on Monday last to the quay, which is but a few

paces from the Edgware-road.

The day proved as propitious as the undertaking is likely to prove a

prosperous one. The number of persons present could not be less than

20,000; for several miles the banks of the Canal were lined with

people; several stages were erected for accommodation, and a long

string of carriages appeared on the public walk.”

――――♦――――

APPENDIX III.

FILTHY LUCRE

from

GOOD WORDS (Volume 20, 1879)

by

CHARLES CAMDEN.

I HAVE chosen my

title with reference to the nature of the materials from which the

gain of which I have to speak is extracted — very fertile “farms of

two acres,” some of our dingy dust yards prove — not with the

slightest to the character of the extractors. Through the courtesy

of Messrs. W. Mead and Co, I have been allowed to pay a visit or two

to a “contractor’s yard,” which claims to be the largest, at any

rate to do the largest business, in London. It is one of

several bordering the Paddington Basin, which from that circumstance

might be called, by a trade pun, a “slop” basin.

Most of the London dust-yards are at the water-side, for the

sake of the water carriage which the canal or river gives them for

their dust and cinders to the country brick makers.

In Messrs. Mead and Co.’s yard, the electric light is used

after dusk in winter, to enable the men to go on with the loading of

the barges. Wandering along the muddy North Wharf Road, with

its dozens of empty tumbrils resting with their shafts up in the

air, or crossing the canal and railway bridges in Bishop’s Road, you

catch sight of an aurora in the sky, and on entering the yard you

see a big meteor star, pulsing white and bluish white, suspended in

solitary brightness over the black heaps from which the weary

sifters have gone home to rest, weirdly lighting up the men plying

pick and shovel down by the canal, and making part of the sluggish

water seem to be phosphorescently afire. As far at the

influence of the light extends, the separate stones can be

distinguished on the gravel wharf, and within that circle the

lamp-posts and the buildings of the yard stand out clear as by

daylight, or rather clearer, since the mysterious brilliance seems

to purge them of their grime. But all gas-jets are turned into

mere faint bilious blotches and outside the magic circle the

darkness, both on land and water, is intensified into ebon gloom.

And now for the daylight aspect of the yard, or rather yards.

An apology for untidiness on a contractor’s premises has a somewhat

droll sound, but one is made for the “muddle” in which the

“slop-yard” is found. The slop is just thawing after long

frost. A wide mass of dark, very unappetising batter-pudding

is pent up on the wharf, waiting for a barge to come alongside; when

a trap will be opened and the unsavoury mess cascade in a mudfall.

This accumulation of scavenging is indiscriminately called slop, but

formerly street dirt dirt used to be divided into mud and “mac,” the

latter being the product of traffic friction on macadamised roads,

and the more valuable for builders purposes because freer from

manure than mud. When I asked my obliging guide at what rate

the yard sold its slop, I was astonished to hear, “We get nothing,

give it away to brick-makers fifteen or sixteen miles down the

canal. Yes, the cost of the carriage falls on us too. We

own twenty barges, with two men and a horse apiece, and we hire as

well. The brick-makers know that we must get rid of the slop,

and so they won’t give us anything for it. If” he added, “the

yard were close to a country district, so that farmers could come

with their carts, they would be glad enough to pay us for it, it

makes excellent manure.”

Separate from the slop wharf by the gravel wharf, which, from

its contrast to its neighbours on both sides looks strangely clean

and almost goldenly bright, is the dust-yard. Outside the

gates empty dust and mud carts, so thickly furred with mud and dust

that the owners’ names are often almost illegible, are congregated

in the manner I have described. Other carts are rolling out

empty and rolling in full. One of them unfortunately goes over

a poor follow, who is taken up tenderly by two brother dusties and

lifted with care into a cab, backed into the yard to receive him,

and in this he is carried off to hospital in charge of a clerk.

The firm owns a hundred and twenty horses, manifestly well

fed, and they are well housed also. In their stables under the

granary which contains their hay, straw, chaff, and crushed oats,

hot as well as cold water is laid on for use at night. Their

drivers look as if they would be all the better for similar

accommodation. The dust that thickly covers the tracks in the

yard is much like that one flounders through in iron-works.

Here the foot sinks over the ankle in dry, black powder, and there

sticks fast in viscous, blacking-like mud. Even on a winter

afternoon, with the mercury dropping to freezing point, the perfumes

floating, or, rather brooding in the atmosphere are not those of Araby the Blest. On a sweltering summer day, after a shower,

what must be the odours steaming up from such a conglomeration of

ashes, egg-shells, oyster-shells, herring-heads, greasy rags and

bones, old boots and shoes, and miscellaneous rubbish! And yet

the people employed in the yard, both men and women — so far as

their flesh can be made out through the dirt with which they have

peppered and besmeared it — look healthy, some quite plump and

ruddy; and the same may be said of the men who go out with the dust

carts and the scavengers.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX IV.

BARGES USED BY JAMES DAVIES (TIMBER) MERCHANTS

LTD.

Colin Davies kindly provided the following information about barges

used by his family's firm of timber importers:

Names of some canal barges on Grand

Union Canal during 1950s and 1960s.

These barges could fit into the 14 locks between Brentford and Hayes

or West Drayton. Each could carry about 20 standards of timber

weighing about 50 tons.

The two principal lighterage companies were General Lighterage

Limited, which was known as “General”, and

The Thames Steam Tug and Lighterage Limited, which was

known as “Limited”. General usually took

the timber from The Surrey Docks via Brentford to Hayes, and

Limited usually took it to West Drayton.

|

GENERAL’S

BARGES |

|

Bullford

Cowford

Mayford

Westford

Uxford

Boxford

Norford |

Southford

Southall

Snar

Scaddle

Irvine

Isla

Gunner |

Trooper

Breech

Bore

Jemadar

Rissaldar

Sirdar

Pathan |

|

LIMITED’S

BARGES |

|

Hayesoak

Hayesbirch

Hayeswood

Hayesboard

Hayesroot

Hayes-etc. |

A few barges were a bit too wide to fit in the

locks via Brentford, and had to come the longer way round via

Regents Park. Some of these were called: Pam, Ripon,

Trunkfish, Brentbird, Brentwren.

I made a list like this while I was working with the forwarding

company in London (W. Hall) who organised the barges to come from

The Surry Docks to our wharves. We were having problem getting

enough canal barges to cope with our imports of timber, and I tried

to remember all the names of the barges that had ever come our way.

That way, I could make a guess at how many barges that were small

enough to get through the locks actually existed .

“General’s” barges had either names ending in Ford,

or names of places like Southall, or military names like

Gunner, Bore, Jemadar, or odd names like Isla,

Irvine, Scaddle, Snar.

“Limited’s” barges with names like Hayesroot, Hayeswood,

Hayesbirch were, according to my father, originally given

those names because they were specially built in the 1930s to carry

timber to the new JDT yard at Hayes. However, by the time I got to

work at Hayes in 1954, they were almost always carrying timber to

Yewsley/West Drayton for our other Co. called Davies Brothers (West

Drayton ) Ltd. That yard was alongside the canal by West Drayton

station. It was between the canal and the railway, and could take

cargoes delivered by rail as well as canal.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX V.

CONTROLLING CANAL CRAFT

(Grand Union Canal Company c. 1938)

Tell-tale Chart Shows Movement of Boats.

CHARTS of one

kind or another are to-day used in many industries as well as in

Government and Police Departments. While it might not be true to say

that the growth of the use of charts and maps owes its origin to the

planning on an intensive scale that took place during the War, it is

certain that since that world disturbance the use of charts and

plans has increased to an enormous extent. Scotland Yard, for

example, uses flags and maps to indicate districts in which crime

and road accidents are more serious than in others, and the Ministry

of Transport makes extensive use of maps and charts in its campaign

to reduce casualties on the roads. The London Passenger Transport

Board controls a vast organisation in which for many years the

control of traffic has been exercised by means of mechanism which

may not inaptly be called vitalised charts.

The Bulls Bridge control board,

Grand Union Canal Carrying Company.

Checking Movements of Craft.

In the early days of the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company Limited

it became apparent that some method whereby the movements of boats

could be checked and controlled was absolutely essential and the

necessity resulted in the adaptation of the chart idea to canal

craft.

Imagine then a line of boats five miles long and that will give some

idea of the size of the fleet of canal craft now controlled from the

Company’s Head Office in London. This fleet, which at the time of

writing consists of 380 boats, operates over three hundred miles of

waterway between such points as London, Northampton, Warwick,

Birmingham, Leicester, Nottingham, Loughborough, Rugby, Coventry,

and the coal producing areas of Warwickshire, Leicestershire, and

Nottinghamshire.

It will be realised that to control craft passing over such a large

area is no small task, but the difficulties involved have been

overcome so that the Company’s Traffic Department is now able to

ascertain almost at any moment the position of any unit of the

fleet.

Eliminating Empty Running.

Behind the scheme there is also the important consideration that the

aim should be to obtain the “best possible use” from all craft and

empty running eliminated as far as possible. The whole scheme of

control is carried out by the Staff as part of the normal working of

the Traffic Department, being entrusted to one officer.

The actual apparatus by which control is exercised is relatively

simple. A map about 11 ft. long and 4 ft. deep is stretched on one

of the walls of the office, and on it various important points on

the canal are shown in much the same way as stations appear on the

familiar maps so frequently issued in connection with the

underground railways of London. The map covers the whole area over

which the Company’s boats travel, and on it appear twenty-four

coloured circles representing Reporting Offices, from each of which

every morning the Head Office receives a report. Thus, at 9 o’clock

each morning in the Company’s Traffic Department the clerk in charge

of boat control, having obtained all the reports, spreads them out

in front of him on the long desk underneath the map. On his left

hand on the wall is the London area, with its reporting points at

Regent’s Canal Dock, Paddington, Bull’s Bridge, Brentford, and

Cowley. On his right hand are the Birmingham, Leicester and Coventry

areas, while in front of him are the intermediate points and the

rack containing numbered ivorine discs which represent boats, red

for loaded boats and green for empty boats.

The reports from the various terminals and observation points are

sorted and then begins the task of moving the “boats”. The terminal

reports show which boats are discharging and loading and alternately

those awaiting orders. The requisite discs are selected from the

rack or from the position previously reported and transferred to the

appropriate point. Boats in transit are moved from one position to

another in accordance with the information shown on the reports and

are always kept on the right-hand side of the route.

In addition to providing a quick means of reference to the position

of all craft, the map also enables slow moving boats to be traced as

the points are so selected that a boat should pass at least one

office during the day, and its failure to do so is at once apparent,

for when the rest of the boats are moved from the previous point the

laggard will still remain.

Not the least useful function served by the chart is that it

indicates the number of boats which will be arriving at any one

point and thus requirements at loading points can be met by moving

empty craft accordingly.

――――♦――――

[Chapter

XI.] |