|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH WATER.

PART IV. ― THE

COMING OF THE

RAILWAYS

THE RAILWAY ONSLAUGHT

“With the advance of railways the waterways lost the monopoly of

inland goods traffic which they had previously enjoyed, and their

position began to deteriorate. As railway competition

developed, many were reduced to a precarious position. Efforts

by Parliament to improve the competitive position of the canal

companies by enabling them to vary their tolls, to become carriers

of goods and to make working arrangements proved unsuccessful, and

ultimately, in many cases at the instance of the canal companies

themselves, about one third of the total mileage then existing

passed to the control of the railways. This occasioned much

disquiet, and during the second half of the nineteenth century

several public enquiries took place, but without any tangible

result.” [1]

Canals and Waterways,

The British Transport Commission (1955)

CANALS – THEIR WEAKNESSES

By the 1840s, the era of steam-hauled public railways had begun in

earnest and with it the inexorable decline of the canal network, with

significant parts falling into neglect or being abandoned.

It is worth considering the factors that led to this outcome.

In several ways the rot was already established within

our canal network by the beginning of the railway era. It stemmed from the

parochial outlook of the canal owners and from a lack of standardisation in

canal

construction, both being defects that the new railway companies were

not to exhibit in any material way, as events quickly proved:

“Canals in their day reached a far greater pitch of prosperity

than the railways have ever attained to, but they suffered fatally,

and do so now, from the want of any serious movement towards their

becoming a united system of communication. Each navigation was

constructed purely as a local concern, and the gauge of locks and

depth of water was generally decided by local circumstances or the

fancy of the constructors without any regard to uniformity.

The same ideas of exclusiveness seem to have been perpetuated in the

system of canal management; there is no Canal Clearing House, and

with few exceptions every boat owner has to deal separately with the

management of every navigation over which he trades.”

Bradshaw’s Canals and Navigable Rivers,

Henry Rodolph de Salis (1904)

Some of these weaknesses might have been

addressed with foresight and determination, but others

are inherent in the canal concept.

Other than the comparatively small amount required to raise steam,

the new railways did not depend on a sufficiency of water to support

their operations; in this

respect they were easier to construct and maintain than a canal, and

more

versatile in the locations that they could serve. A crew of three

could operate a freight train hauling a load of 500 tons or more; the same workforce manning a pair of narrow boats could move

around 50 tons. Quicker transit time was another advantage in

the

railways’ favour. Even in their earliest days, steam trains

ran at a far higher speed than their waterborne

counterparts.

Although the railways generally had transit time on their side, this was not

always so. Where a journey was short and the supplier and

consumer both had canal wharfs ― often the case on the Birmingham

canal network ― the speed advantage could lie with the canal, and

canals in this category quickly became targets for their voracious

new competitors. Efficient management could also make a

considerable difference to transit times, and here it is

interesting to note a passage from the Rusholme report, the

writer referring to government control of canals during WWI . .

. .

“The Committee [2] sought to organise

traffic on these canals with a view to relieving the congestion on

the railways, and the result of their efforts was a considerable

increase in the amount of traffic carried and an improvement in the

speed of conveyance, until it compared on the whole not unfavourably

with that of heavy traffic on the railways.”

Canals and Waterways, The British Transport

Commission (1955)

. . . . and this despite a backlog of repair and maintenance work

that had built up during the war years, which suggests that

transit times might have been improved with more efficient

management and better co-ordination between canal companies, requirements

that were generally lacking. But little could be done to manage

the weather. Steam-hauled railways rarely suffered from

delays due to drought and were less affected by freezing conditions, but

each could bring canal traffic to a standstill, sometimes for long

periods despite the construction of reservoirs and bore holes, and the

operation of ice-breaking.

But lack of speed alone did not bring about the decline of canal

carrying. The failure of canal companies to develop

inter-working ― let alone to amalgamate ― was a significant

drawback, and one in which government might have intervened by

forcing mergers similar to those that they eventually imposed on the

railway companies in 1921 (the ‘grouping’). Various inquiries

and commissions on canals and transport over the years came to much

the same conclusion as that arrived at as recently as 1928:

“. . . . we are of the opinion that certain canals still possess

considerable value as a means of transport, and that, properly

rationalized and developed, they can be made to render much useful

service to the community in the future. We are satisfied that

a process of amalgamation is a necessary preliminary to any

developmental programme.”

The Royal Commission on Transport,

Sir Arthur Griffith Boscawen (1928)

Together with investment, company amalgamations might, over time,

have ironed out another significant difficulty, the lack of

standardization.

Canals were generally built to serve the needs of local

industries, which fostered a parochial attitude to their

construction and management. Their dimensions were influenced

by the type of trade they were designed to serve, by local

conventions, [3] by the amount of capital

available for their construction, by water supply and other

topographical limitations:

“The locks and waterways of canals are altogether wanting in

uniformity. One of the great difficulties of canal traffic in

Great Britain, in England and Wales especially, has been that

scarcely two canals have a continuous gauge. We find even upon

one canal two or three different gauges of locks. In some

instances the canals forming a continuous line are approximately of

the same size, but the gauge of the locks is entirely different.

Either their locks are considerably shorter, or are considerably

narrower, or the water-way is considerably shallower. There is

nothing like a common uniform gauge of canal throughout the whole

distance.”

E. J. Lloyd, Engineer to the Warwick canals, giving

evidence to the

Select Committee on Canals (1883)

Even the dimensions of the ubiquitous ‘narrow boat’ varied:

“’Narrow boats’ or ‘monkey’ boats are by far the most numerous

class of vessel engaged in inland navigation. They are from

70ft to 72ft long by 6ft 9ins to 7ft 2ins beam, and draw from 8ins

to 11ins of water when empty, loading afterwards to about 1ins to 1

ton.” [4]

Bradshaw’s Canals & Navigable Rivers,

H. R. de Salis (1904)

Because government took no interest,

statutory standards designed to facilitate inter-working between

different canal systems were not imposed, and waterways continued to vary in the

maximum size and loading of craft they could accommodate. The

Grand Junction Canal main line is an example; it can accommodate

craft 72ft long by 14ft 3ins beam and 3ft 8ins draught, [5]

but the locks on the adjoining systems at Gayton and Norton

restrict craft to 7ft beam, although they in turn lead to broad waterways.

In the 1930s, the Grand Union Canal Company widened the line from Braunston to Birmingham via Napton Junction,

which includes a short section of the adjoining Oxford Canal, but

with that exception the Oxford Canal is narrow:

“As almost all the through routes between important centres at

the present time contain links to narrow canal, the effect of these

diversities of gauge is to confine any long distance through traffic

to narrow boats. Nothing but a narrow boat can navigate

between London and Northampton, London and Leicester, London and

Nottingham or Manchester, and nothing but a narrow boat can get into

or out of Birmingham from anywhere. If we attempt to take our

narrow boat from London to Leeds we shall fail altogether, as we

shall be stopped at either Wigan, Sowerby Bridge, or Cooper Bridge,

by the locks on the Leeds and Liverpool Canal, or Calder and Hebble

Navigation, which, although twice the width required by the narrow

boat, are 10 feet too short.”

H. R. de Salis (Vice Chairman Fellow, Morton &

Clayton) giving evidence to

the Royal Commission (1906).

Narrow locks also slowed traffic, due to pairs of narrow boats

having to lock through individually rather than abreast.

Even within the otherwise broad Grand Junction Canal, the Blisworth

and Braunston tunnels were too narrow to allow wide boats to pass,

while river barges (14ft beam) could only be accepted without

restrictions on its more heavily worked southern section below

Berkhamsted. [6]

Coupled with the physical limitations on through working, craft

traversing different companies’ systems faced a chaotic pricing

structure that subjected them to varying charges at toll offices

along their route. And where a craft briefly entered another

canal company’s system in order to reach its destination,

disproportionately high ‘compensation tolls’ [7]

were often imposed. An example was the Oxford Canal, which

was authorised to impose a compensation toll of 2s 9d a ton on coal

and 4s 4d on all other items at the junction of the Warwick & Napton

Canal, and in this way received a quarter of a million pounds over

twenty years. [8] All this meant that

‘through charges’ could not be determined accurately in advance; craft

were gauged and the captains paid in cash at each toll office they

passed on their journey, or if working for a carrying company with an account, then

the company was billed. Chaos would have ensued had the same

charging system operated on the railways.

By comparison, from the Liverpool & Manchester Railway onwards, the

4ft 8½ins gauge applied to most of our mainline railway network, [9]

thereby permitting traffic to move from one company’s system to

another. Railway company mergers also took place resulting in

longer routes under single managements. [10]

Where passengers and freight passed through the domains of different

companies to reach their destination, arrangements were negotiated

for through working and end-to-end charging ― set up in 1842, the Railways Clearing

House allocated the revenue received in proportion

to the resources that each had provided. [11]

Overall, railway companies had a much wider vision of their business

and how it might be developed than did their blinkered waterway

competitors of their own assets. Boyle summed the position up

succinctly:

“The canal, on the contrary, is not calculated to deceive

anybody. Beside the railway it appears the embodiment of

quiet, plodding, undisguised sluggishness; and if this is not

actually the case, it must be admitted the erroneous impression is

not altogether without foundation. There is certainly nothing

fast about a canal. It seldom changes or improves; and when it

does so, it is only by imperceptible degrees. It is apparently

the same yesterday, today, and for ever; ― perpetuating its

primitive arrangements to all time and under all circumstances.

Enlightened enterprise appears to have shunned it as an ungenial

sphere for all its operations, and the world in its march of

improvements seems to have left it behind hopelessly on the road.”

Hope for the Canals,

Thomas Boyle (1848)

In Britain, the need for large-scale modernisation of the

canal system was an issue in which the state took no part,

for transport was seen as a matter for individual companies. Some

of our early canals ― especially those built before the French Wars

drove up construction costs ― paid large dividends rather than

investing their revenue in straightening, widening and deepening

their waterways, and in providing bank protection when steam-power became feasible

― some systems would not at first accept

powered craft. In France, Belgium and Germany,

where the introduction of railways also had a damaging impact on inland

waterways, the state intervened. The outcome was that

waterways were modernised and steam haulage introduced, while protective legislation regulated

canal and railway tariffs. Not until nationalisation in 1947

did the British government take a material interest in inland waterways,

but by then it was too late. The development of road transport

and of the motorway network made canal modernisation along

northern European lines wholly uneconomic.

――――♦――――

THE ONSLAUGHT BEGINS

The success of the Bridgewater Canal proved the viability of canal

transport, and within a few years of its opening an

embryonic national canal network came into being with the

construction of canals such as the Trent & Mersey and the Oxford.

The early 1790s saw the period known as ‘canal mania’, when huge

sums were invested in new canal schemes, often with little serious

consideration of their viability. Partly as a result, the

canal network grew to over 4,000 miles, becoming both cause and

effect of the rapid industrialisation of the Midlands and the North

of England. The period between the 1770s and the 1830s is

often referred to as the ‘Golden Age’ of British canals, an age in

which canal companies faced no serious competition and the

complacency of the monopoly operator became established.

If any single date marks the beginning of the decline of our canal

network, the 15th September 1830 must be a serious

contender, for on that day the world’s first mechanically-operated

inter-city public transport link, the Liverpool & Manchester

Railway, commenced business:

“Although the advantages of a railway for the conveyance of

passengers and goods are very superior to any other mode, even when

horses are employed as the moving power; yet, these advantages are

vastly increased by the substitution of Locomotive Steam Engines . .

. . The fare between these towns [Liverpool and Manchester]

for inside passengers by the railway is five shillings; before the

opening of the railway it was twelve and fourteen shillings by the

ordinary coaches. The distance between the towns is run on the

railway in two hours: by the turnpike road it occupies four and a

half or five hours. . . . Goods shipped at Liverpool by water

conveyance to Manchester, are thirty-six hours on the passage; but

by the railway they are delivered in about five hours . . . . And in

winter, the canal part is frequently frozen for many weeks, so as to

obstruct all passage; and goods have to be transferred from the

canal to land carriage, suffering loss of time, increase in expense,

and risk of damage in the transfer.”

Observations on Railways: particularly on the

proposed London & Birmingham Railway, Anon

(1831).

Although the march of technology would have delivered the

steam-hauled public railway, the Liverpool & Manchester Railway grew

out of a commercial need, to combat the high charges and poor

service provided by the Bridgewater Canal and the Mersey & Irwell

Navigation in transporting goods between Liverpool and

Manchester (it was said that goods could take longer passing

between the two cities than in crossing the Atlantic). The irony

was that the Bridgewater Canal had been built seventy years earlier

to address the very same problem, the expensive and poor service

then provided by the Mersey & Irwell Navigation.

The waterways did what they could to oppose the Liverpool &

Manchester Railway, even to the extent of threatening physical

violence to the railway surveyors. The first Bill laid before

Parliament failed, but at the second attempt the railway company

succeeded [12]

in obtaining the necessary private Act, and construction commenced.

Faced with a fait accompli, the waterways attempted to retain

their trade by reducing tolls and improving services; the Irwell

Navigation straightened sections of its line and improved its water

supply; the Bridegwater Canal Company built new docks and

warehouses, improved access to the River Mersey at Runcorn and linked their docks to the Weaver Navigation.

In 1844, the Bridgewater bought the Mersey & Irwell Navigation and

eventually reached a trading agreement with its new competitor, the

London & North Western Railway.

In these respects the

Bridgewater Canal is unusual. Faced with the railway onslaught,

the company responded with vigour and continued to trade profitably

until acquired by the Manchester Ship Canal Company in 1885.

But compared with many other canal companies the Bridgewater had

the advantage of a

strong business foundation. At one end of its line lay Manchester, a major manufacturing city,

and at the other end lay the Runcorn docks and a river link to a major seaport, Liverpool.

In addition, there was a healthy coal trade that lasted into the 1970s.

When faced with railway competition, canal companies in less

fortunate circumstances followed the Bridgewater example by reducing their

charges, generally by between 30% and 50% of their former level, [13]

but although this slowed their commercial decline it did not halt

it. Tonnage often increased in response to the cheaper toll

rates, but total revenue fell, resulting in reductions in manpower

levels and waterway maintenance, and in the sale of company assets.

The new railways quickly acquired business where transit time was

important, such as with perishables, packages and passengers.

Passenger traffic was never a staple source of revenue for canals, although in the north-west of England and in Scotland it did

make a contribution on some systems. [14]

Most of the railways’ passenger traffic was either entirely new, or

was taken from the stagecoach operators on routes where they

competed (such as Liverpool to Manchester), the stagecoach operators

going out of business (or becoming feeders) almost as soon as a

competing railway commenced business. Having established a

profitable line in passenger traffic, the railways then began to

capture freight where another significant,

although less obvious advantage of speed, lies in swifter logistics.

This allows manufacturers and retailers to reduce their stocks of raw

materials and finished goods, thereby saving on financing charges

and/or releasing some of their capital for other

purposes.

――――♦――――

SOME CASE STUDIES

Faced with a losing battle, some canals ― mostly the less successful

― soon sold out to the competing railways, sometimes even offering

themselves for sale. By purchase, amalgamation or lease, [15]

the railway companies gradually acquired a substantial interest in

the canal network to

the extent that by 1865, about one third of canal mileage in

England and Scotland was under some form of railway control. [16] On occasions a canal fitted the railway’s business, acting as a

feeder or giving freight access to areas of the country served by a

competing railway company, but generally a railway company’s

acquisition permitted it to remove waterway competition by a

combination of increased tolls and declining maintenance:

“The cases in which railway companies have a more or less strong

or less strong positive interest in pushing the trade on the canals

belonging to them are exceptions to the rule.”

Report of the Royal Commission on Canals,

pub. 1909.

One company stifled by railway ownership was the Kennet & Avon Canal, which

links Reading on the Thames with Bristol. This

waterway comprises sections of the rivers Kennet and Avon, which between Newbury and Bath

are linked by a 57-mile ‘broad’

canal. Engineered by John Rennie Snr. and opened throughout in 1810,

the Kennet & Avon was successful in its early years ― mainly carrying coal and

stone ― although its dividends never exceeded a modest 3¾% (1840)

due mainly to its heavy construction costs. The opening of the Great

Western Railway in 1841, followed by the Berks & Hants Railway in

1847, diverted most of the Kennet and Avon’s trade to rail despite

the canal company having lowered its tolls. When taken over by the

Great Western Railway in 1852 for a

fraction of its construction cost, its tolls were increased and

its trade, unsurprisingly, declined still further. By 1868, the

canal’s annual tonnage

had fallen from 360,610 in 1848 to 210,567, and the canal ceased to

make any profit after 1876. [17] Following WWI,

when more trade was lost to road transport, the Great Western Railway

Company attempted to close

the canal but were prevented from doing so:

“The local authorities in Wiltshire, Berkshire, and Somerset,

through whose area the Kennet and Avon Canal runs, are still a

little anxious as to the fate that awaits this old waterway. The

Great Western railway, which originally proposed to apply for powers

to abandon the canal altogether, has now, in consequence of

widespread opposition, promised to modify its application so that,

though the canal will be closed to traffic, the company will remain

liable to carry out its present obligations ‘except those which have

been necessary for traffic purposes.’

In that qualifying phrase a great many fears which the railway

company has sought to answer have been revived. The one specific

promise given is that the company will maintain the pumping station

at Crofton and so ensure a flow of water into the canal. The local

bodies are asking if the locks and their gates will be kept in

proper repair; whether the channel will be allowed to become choked

with weeds and silted up; and whether ultimately there may be

stretches of virtually stagnant water in and near the towns once

served by this waterway that joins the eastern and western seas. . .

.”

The Times, 19th January,

1927

By 1950 most of the Kennet & Avon was disused and impassable, an

outcome shared by much of the railway controlled canal system.

A further attempt at closure in the 1950s having failed, sufficient

of the Canal survived into the preservation era, since when, with unstinting volunteer effort and Lottery

grant support, it has been transformed into what the 1968

Transport Act classifies as a ‘cruising waterway’. [18]

Another, and in some ways more damaging strategy adopted by railway

companies to stifle canal trade, was to gain control of a short

section of a much longer through route. The toll for that section

could then be increased to the highest permissible level, thereby

imposing a disproportionately high increase to the overall through

charge.

An example was the through toll on iron goods from South

Staffordshire to London, of 4s 6d per ton. The sum charged over the

10-mile Birmingham section, controlled by the London & North Western

Railway Company, amounted to 1s 6d, while the independent canals received 3s

for the remaining 146 miles. Had the Birmingham section being

charged at the same rate as the remainder, the through toll would

have been reduced by a quarter. [19] However, it

must be said that the railway companies were merely adopting a

strategy already operated by some canal companies in the same

circumstances:

“One great impediment has been found to exist, in the present

disjointed state of the Canal interests and the varying systems

under which they carry on their operations. Some of the existing

Companies, possessing lines of Canal which form central links in a

great chain, take advantage of their peculiar position, and

establish a rate of charges so high as to secure to themselves a

large return for their capital, even upon a small amount of traffic. This practice, while it obliges the other Companies, not so

advantageously situated, to reduce their rates to such an extent

that they are unable to conduct their business with a profit, at the

same time prevents such a reduction in the general charges of the

line as would enable the several Companies, as a body, to maintain a

fair competition with the Railways.”

Second Report from the Select Committee on

railways and Canals Amalgamation (1846)

Following WWI., the canals were faced with increasing road

competition and difficulties in recruiting boat crews (many who had

joined the forces or found better-paid employment in factories

engaged on munitions work, never returned) while the railways were

by then being subsidized by the State:

“The main difficulty with regard to the extension of the use of

canals lies in the freight charges. The railways, subsidized by the

State, have been able to keep their charges down, while on canals

increased expenses have forced freight charges up. In 1913 the canal

charges were lower than those on the railways; to-day they are

considerably higher.”

The Times, 10th October,

1919

But aggressive railway competition was not the sole reason that

canal companies went to the wall. Other causes of failure lay in

their original business case being unsound (e.g. under-estimated

construction costs, over-estimated traffic receipts) [20]

or in the local industry(s) on which they relied

disappearing under changed circumstances, such as coal mines

becoming worked out, canal-side iron works closing in favour of

large steel mills, or grain mills moving to the ports to be more

economically placed to mill cheap imported grain. The Basingstoke

Canal (also known as the London and Hampshire Canal) in part fell

victim to London increasingly receiving its agricultural produce

from the midlands and north of England via the Grand Junction Canal, and later the

railways, and importing cheaper foodstuffs through the London

docks.

The Basingstoke Canal linked that town with the Thames at Weybridge, via the River

Wey Navigation [21] ― several plans to continue it

to the South Coast never materialised. Engineered by William Jessop

and built as a broad canal, it was opened throughout in 1794. Unlike

the canals in the midlands and the north of England, which served

mainly industrial needs, the Basingstoke Canal was intended to

stimulate agricultural development in central Hampshire by

transporting timber, flour, malt and agricultural produce to

London, with return cargoes of coal, manure and groceries.

Construction costs were much higher than anticipated added to which the

traffic projections proved over-optimistic By 1796 the Company was on the brink of bankruptcy. To stave off failure bonds were

sold, but servicing the interest absorbed the profits resulting in the Company’s

shareholders failing to receive a dividend at any time in the

Canal’s

history. By the 1820s, improved roads in the area led road transport presenting serious

competition, with a faster door-to-door service at comparable

charges.

Ironically, trade revived briefly during the 1830s with the construction of the

South Western Railway, the canal being used to

transport railway construction materials; but once the railway had

been opened, canal trade slumped. Price-cutting by both companies

continued throughout the 1840s, the railway having the advantage of

being able to cross-subsidise reduced freight rates from its passenger

receipts (by then a common practice):

“Another consideration which must not be overlooked is, that

although it has been stated that with proper management Canals might

maintain a successful competition with railways in the carriage of

heavy goods, still such competition has hitherto been carried on

under great disadvantage, owing to the large profits made by Railway

Companies on passenger traffic, which enables them to submit in some

instances even to a loss on the carriage of merchandize with a view

to withdraw traffic from Canals.”

Second Report from the Select Committee on

railways and Canals Amalgamation (1846)

Another short boost to trade occurred in 1854, when the Canal was

used to transport materials for the construction of Aldershot Camp,

after which business again declined. In June 1866, the proprietors

resolved to go into liquidation. By this time, other canals in the

south ― notably the Wey and Arun, the Thames and Severn, and

the Wilts and Berks ― had already expired, but the Basingstoke was

not abandoned. There followed a succession of owners, one

attempting to sell in 1904:

“The canal was purchased in 1896 by its present proprietors, who

have expended a considerable amount of money on its restoration and

improvement, but apparently without success, as at the present time

(1904) the navigation is again for sale. Of late the towing path has

become much overgrown in places, thereby causing horse towing to be

very difficult.”

Bradshaw’s Canals & Navigable Rivers,

H. R. de Salis (1904)

Despite the auctioneer’s encouraging sales pitch [Appendix]

there were no takers. WWI brought a further brief revival of trade, with Government stores

and munitions being carried to Aldershot Camp with return

cargoes of manure and timber. In 1923, the Canal was bought by

Alexander Harmsworth, who ran a successful business until his death

in 1947, but only on the section below Woking, the upper reaches

having by then become a picturesque backwater:

“Long stretches of this waterway are among the quietest and

least-frequented places in the country. Rich vegetation abounds on

its banks. In places the trees meet above it, forming in summer long

tunnels in which the light is tinged a greenish shade, giving to

whoever may pass through them, in a boat hardly propelled through

the weed-thick water, a ghostly and baleful air. Here and there a

broken bridge crosses the water, here and there an empty boat-house

stands mournfully on the bank”.

The Times, 28th August,

1929

The Canal was not taken into the nationalisation programme in 1947,

and by the 1960s it was derelict. But as with the Kennet & Avon,

sufficient of it survived for restoration. Today, after years of

effort by members of the Surrey & Hampshire Canal Society in

partnership with local authorities, 32 miles of the Basingstoke

Canal are again open to navigation, albeit restricted at times due

to water shortage.

Some waterways did manage to hold their own against the railway

onslaught, but these tended to be the river navigations, which

required comparatively few locks, had a dependable water supply and

could more readily be widened and deepened. An example is the Aire &

Calder Navigation in West Yorkshire, which runs for 34 miles from

Leeds to Goole, with a 7½ mile branch from Wakefield (where it

connects with the Calder & Hebble Navigation) to Castleford. During

its life the Navigation has been widened and deepened, its locks

have been lengthened, and canal cuts have been constructed to

straighten sections of the route.

During the 1840s, the Aire & Calder’s trade was reduced by about a

third following the arrival of the railways, but the Navigation was

fortunate in having two innovative engineers, Thomas Bartholomew

and, following his death in 1852, his equally talented son, William. Thomas was an early advocate of steam

propulsion and by the time of

his death two-thirds of the traffic on the Navigation was hauled by

steam tug. Besides carrying out many improvements to the waterway,

William Bartholomew developed a sectional barge system. Known as

‘Tom Puddings’, each comprised six separate compartments with a bow

and stern section, which, under the control of four men, could move 800

tons of coal. On arrival at Goole the contents of each

compartment (‘tub’) could then be emptied mechanically into a

collier by means of dockside hydraulic hoists. By 1913, there were 18 tugs,

1,010 compartments and 1,560,006 tons of coal was being carried

annually. [22] The compartments were still

carrying around half a million tons of coal until the late 1960s,

long after most British canals had ceased to be used for commercial

traffic, but the gradual demise of the coal industry led to

compartment traffic ceasing in 1986.

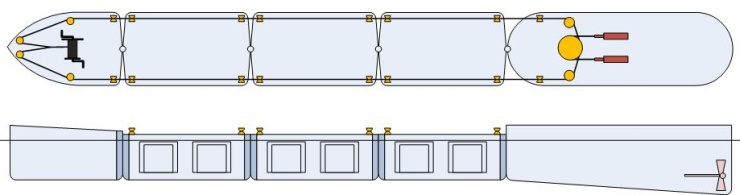

A

‘Tom

Puddin’

― Bartholomew’s sectional boat.

In addition to investing in the Navigation’s development, its

success can also be attributed to a firm business base in

the shape of the large Yorkshire coalfields that it serviced and on

the company’s development of Goole Docks, from which coal and other

goods were exported in quantity and into which pit props for the

mining industry were landed:

“. . . . the collector of customs at Goole, said that there were

large warehouses there belonging to the Aire and Calder Navigation

Company. He produced a mass of reports made to the Board of Customs,

from which it appeared that cotton-twist, fustians, woollen goods,

coals, and iron were exported thence.”

The Times, 15th July,

1845

The decline of the coal industry and of heavy manufacturing

generally saw commercial traffic on the Navigation dwindle, but not disappear. As recently as 2007 the Navigation is reported to

have carried 300,000 tons, mostly of petroleum and building aggregates. During the 1960s, the navigation underwent further modernisation, in

which the locks from Goole to Leeds were upgraded and enlarged to

accommodate vessels conforming to the 700-tonne Euro-barge standard. The Navigation also provides important leisure cruising links to,

among other waterways, the Leeds & Liverpool Canal and, via the

Calder & Hebble Navigation, to the Huddersfield Broad and Narrow

canals and the Rochdale Canal (the latter two being restored to

use).

But overall, the Aire & Calder’s success was untypical of British

inland waterways, which went from a position in the 1840s in which

they carried more freight than the railways, to one at the end of the

nineteenth century when their share of the market had slumped to

about a tenth; or put another way, overall growth in canal carrying

during the period remained almost static whilst the corresponding

rail freight business burgeoned.

――――♦――――

THE LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

“In 1825 the tract of country lying between London and Birmingham

was surveyed by Messrs John and Edward Grantham, for the purposes of

ascertaining the practicability of forming a railroad between the

metropolis and the town of Birmingham. Sir J. Rennie,

likewise, surveyed a tract of country for the same purpose carrying

the route of line along the valley of the Thames to Oxford and

thence to Birmingham. This, however, was abandoned on account

of the tunnelling necessary at Oxford, and the periodical floods to

which the Thames is subjected. Various portions of country

were also surveyed and diversions made in all directions until the

most eligible, and that which presented least, difficulties, was

evident. In 1828, the first public intimation appeared of the

formation of ‘A Company for making a Railway from London to

Birmingham,’ with the name of Mr Stephenson, of the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway, subjoined as its engineer.”

The London and Birmingham Railway Guide:

Joseph W. Wyld (1838)

The seeds of the London & Birmingham Railway were sewn as early as 1825.

Sir John Rennie proposed a London to Birmingham railway passing through

Qianton

and Banbury, but nothing came of the scheme or of a later proposal by

Francis Giles for a line passing through the Watford Gap, Rugby and

Coventry. However, both schemes caused considerable alarm

among canal companies, turnpike trusts, stagecoach operators and the

proprietors of coaching inns and stables. Each group could be depended on

to oppose with vigour any railway bill that eventually came ―

they did not

have long to wait.

In 1829, two schemes were published in which lines were proposed

along the routes put forward by Rennie and by Giles. Rather than

compete with each other ― in addition to numerous opposing

commercial and landed interests ― the schemes’ proprietors sensibly

combined forces, employing George and Robert Stephenson to review

their plans and recommend which to adopt. The Stephensons having

chosen the eastern route, a detailed survey was then undertaken by

Robert Stephenson and Thomas Gooch, [23] which formed the basis of a Bill

submitted to Parliament in 1832. This Bill passed the Commons but was

rejected by the Lords, the dissenting landowners being in the

majority of 59 to 53. The original route was then altered to avoid

the estates of most of the opposition,

while the remaining dissenters along the line were made financial offers they

found difficult to refuse. The outcome was that on the second attempt the

London & Birmingham Railway Bill passed both houses and received the

Royal Assent on 6th May, 1833.

Construction then proceeded swiftly. Boxmoor was reached in July,

1837; Tring in January 1838; Denbigh Hall in April; and the line was

opened throughout in September of that year. The 112½-mile railway

had taken five years to complete; the 131½ miles of the Grand

Junction Canal

(including its pre-1805 branches) had taken twelve.

The route chosen by Robert Stephenson keeps close company with the Canal

for many miles. From Cassiobury Park, Railway and Canal ascend the valleys of the Gade and the Bulbourne before crossing

the Tring Gap in deep cuttings. There then follows a long descent to Milton Keynes where

Canal and Railway briefly part company, the Canal weaving a sinuous

path around the modern town while the Railway takes a more direct route to

Wolverton. Both then cross

the valley of the Great Ouse, the Canal on a substantial

earth embankment,

the Railway on a brick viaduct. At Roade, rather than following

Barnes’s example of tunnelling the ridge, Stephenson took the

Railway through in a deep cutting. At Buckby, Railway and Canal finally

diverge, the Canal heading west towards its nearby rendezvous with the

Oxford Canal, the Railway departing in a north-westerly direction

towards the Watford Gap and the notorious Kilsby Tunnel. Here

Stephenson met his Nemesis in the form of the quicksand

deposits and severe flooding that had been encountered by the canal tunnelers at Blisworth

― in neither case did the trial borings reveal the problem.

Until railway competition changed the picture, the Grand Junction

Canal Company had taken

full advantage of its monopoly status as a transporter of

goods:

“As a special instance of a canal taking advantage of its

position to raise its rates, we may mention the Grand Junction

Canal, which extends from Paddington to Braunston where it joins the

Oxford Canal. The Grand Junction Canal was an important link between

London and the great mining and manufacturing sections of

Warwickshire, Cheshire, Staffordshire, etc. It was a monopoly

without competitor; its exactions, excessive rates, discriminatory

rates, and its supercilious conduct caused loud and general

complaints even as late as 1836.”

Remarks on the tonnage rates and drawbacks of the

Grand Junction Canal, Mercator (1836)

No sooner had the new railway company commenced operations, than it

too began to exploit the monopolistic position that it had won from the

stagecoach operators:

“THE LONDON AND BIRMINGHAM

RAILWAY: No system appears to us to

require more vigilant scrutiny, nor the conduct of any body of

persons to be more jealously watched, than railway companies and

railway directors. The moment that all means of opposition ceases an

attempt is made to impose on the public the most exorbitant and

unjustifiable charges for goods and passengers. We last week

expressed our opinion on the subject of the increase of price for

the carriage of parcels from 1d to 1½d per pound, and we believe we

may now congratulate the public on its abandonment, and the

immediate reduction to the old prices. But there are other ways that

these great monopolies are made to press hardly on public

convenience; among others, we beg this week to direct the attention

of our readers to the sudden increase in the price of conveyance

that has taken place to all the intermediate stages since the

opening of the railway throughout to London, and the consequent

removal of the stage-coaches from that line of road.”

The Times, 29th

September, 1838

The London & Birmingham Railway’s tussle with the Grand Junction

Canal Company over their respective shares of the

freight traffic between London and the Midlands was slow to start, for the

Canal was not affected by the Railway’s prime interest at that time

― passengers. But as the railway moved into freight

carrying, a price-cutting war began that was to last off and on

until nationalisation eventually brought railways and canals under a

single owner, the State.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

(The Times, 28th October, 1904)

THE BASINGSTOKE CANAL.—By

order of the High Court of Chancery, the Woking, Aldershot, and

Basingstoke Canal was offered for sale by auction at the Mart

yesterday, by Mr. B. I’Anson Breach, of the firm of Messrs. Farebrothers, Ellis, Egerton, Breach, and Co.

In giving particulars of the property the auctioneer remarked that

the occasion presented a unique opportunity for speculators. The

canal, which was constructed under two Acts of Parliament passed in

the reign on George III., was built at a cost of between £150,000

and £200,000, and it was opened in 1794. It started in the town of

Basingstoke, and, passing through some of the most picturesque and

beautiful residential neighbourhoods of Hampshire and Surrey, it

ended at the junction of the river Wey, by means of which a direct

line of navigation was opened to London, a distance of nearly 70

miles. The canal was about 37 miles long, and there were 29 locks. The traffic at the outset was very remunerative, but when the

South-Western railway was constructed it seemed gradually to “swamp”

the Canal. There were 13 wharves conveniently placed at important

military and trading centres; and along the canal were a number of

lockkeepers’ dwellings, warehouses, &c., principally let. The

property embraced a total land and water area of about 366 acres. There were low rentals now coming in amounting to £500 a year, and

the revenue — the general trading of the company — was £5,000. He

saw no reason why the Canal should not be carried on to Southampton;

and a splendid opportunity was afforded to the War Office of

connecting their waterways with the camp at Aldershot. Replying to

questions, the auctioneer stated that the lack of water in the canal

about a month ago near Woking arose from the fact that the receiver

had been putting in a new lock gate.

Under the existing Act it was clearly defined that the Canal was to

be used for the purposes of a canal; but he knew no difficulty which

would prevent a purchaser from obtaining a short Act of Parliament

to enable him to convert it into a motor track if he wished to do

so. Adjoining property owners, under section 101 of the Act, had the

right of pre-emption on terms which would have been settled by

Commissioners. He then invited bids for the property.

To his suggestion that they should begin at £50,000 there was no

response, upon which he invited offers of £40,000 and £30,000 with

the same result. He was, he remarked, in the hands of intended

buyers; but he was acting under sealed instructions, and could

therefore give no hint as to prices. Subsequently he invited bids of

£25,000 and £20,000, adding that he could not go below the

last-mentioned amount. No offer, however, was made for the property,

which was accordingly withdrawn. |