|

THE LONDON & BIRMINGHAM CANAL

While the London & Birmingham Railway was under construction the

Grand Junction Canal Company found itself facing another potential

competitor, and from an unexpected quarter ― a competing canal.

But before touching on this potential interloper it is worth

mentioning a slightly earlier scheme that appears to have grown out

of a general dissatisfaction with both the charges (including

‘compensation charges’) and the transit time between Birmingham and

the terminus of the Grand Junction Canal at Braunston. This

was the ‘London & Birmingham Junction Canal’:

“At a meeting of the Coal and Iron Masters held at the Hotel in

Dudley, on Monday, the 11th day of February, 1828, on the subject of

the proposed London and Birmingham Junction Canal . . . . that the

present tonnages on the iron and coal, navigated upon the canals

between Staffordshire and London, and intermediate places, are

higher than they reasonably ought to be, and the rates exacted from

the public under the plea of compensations, merely for passing out

of one canal into another, are unjust and oppressive.

Resolved. That this Meeting . . . . consider the making of

such a canal to be a measure entitled to their cordial support,

inasmuch as it will be of important benefit to the iron and coal

trades of this district, by affording a much more expeditious and

direct conveyance to London, at a considerable reduction of freight,

and by relieving the public from the exactions to which they have

been so long subjected. . . . . after a comparison of Parliamentary

and other charges on existing lines, it is calculated that a saving

of 2s 6d per ton will be effected in the freight of coals carried

from Staffordshire to the line of the Grand Junction Canal, and a

saving of 5s per ton in the freight of iron, grain, general

merchandize passing between Braunston and Birmingham.”

The Times, 21st February

1828

Surveyed by Telford, the proposed canal was to commence at a point

on the Stratford-on-Avon Canal about ten miles from Birmingham,

then, following a 20-mile pound, form a junction with the Oxford

canal near Braunston. The promoters claimed the scheme would

reduce the number of locks between Braunston and Birmingham by 57

and shorten the Birmingham to Coventry journey by 18 miles (and 36

locks). But the scheme failed when it was discovered that its

subscription list had been fraudulently inflated to make it appear

there were more subscribers than was the case. It does,

however, serve to illustrate the dissatisfaction in terms of cost

and delay with the Braunston to Birmingham route ― when later faced

with railway competition, the canal companies on that section needed

to reduce their charges significantly (between 2s 6d and 5s per ton)

in order to retain trade.

While the London & Birmingham Junction Canal did not pose a commercial

threat to the Grand Junction Canal Company, the next canal scheme

to appear did, for the ‘London & Birmingham Canal’

was intended to bypass the Grand Junction Canal altogether and, by

taking advantage of the latest developments in canal engineering,

halve the journey time from Birmingham to London. This

canal was to start at Lapworth, on the Stratford-upon-Avon Canal,

then following a line via Banbury, Brackley and St. Albans, terminate on the Regent’s Canal. The scheme’s proprietors

claimed that this would reduce the number of locks between

Birmingham and London by 120, which implies that much of the route

was planned to be on the level and would therefore require

considerable engineering in the form of embankments, cuttings and

tunnels, much in keeping with what would later be expected of a railway:

“The proposed Navigation will possess all the improvements of the

best modern canals; where tunnelling is necessary, two tunnels, with

a towing path under each, will be made; the sides of the Canal will

be walled, and the greatest of all modern improvements, the double

towing path, will be carried throughout the whole line. . . . By the

proposed route, goods will be delivered in London in 32 hours,

instead of 70 by the existing route. The saving in freight 20s per

ton.”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

26th March, 1836

By this date construction of the London & Birmingham Railway was

well advanced and there was insufficient interest to finance a new

waterway, particularly on such a grand scale. The original

proposal was then pared down. The line from Birmingham would

“terminate at or near the south end of a certain Tunnel called

the Blisworth Tunnel” (nicely understated), thereby “avoiding

the enormous lockage, and the imperfect structure of the Warwick and

Birmingham, and Warwick and Napton Canals, and the unjust

compensation tolls now paid to the Oxford Canal Company at Napton.”

The amended scheme also came to nothing, leaving the Grand Junction to face the impending onslaught from the London & Birmingham

Railway.

――――♦――――

RAILWAY COMPETITION

The Grand Junction Canal Company had a reasonably firm business

foundation. Besides forming part of a direct transport link

between the Midlands and the Capital ― the only canal to do so ―

much canal-side business was developing along the Uxbridge to

Norwood section and on the Paddington Arm, while the adjoining Regent’s

Canal provided an important link with the City and the London Docks. Unlike many other canals, the

Grand Junction did not depend heavily on one

particular local trade, such as coal, but carried a variety of goods

ranging from short distance loads of agricultural produce ― especially hay and straw to sustain the Capital’s horse-powered

traffic ― to long distance consignments of coal, salt, pottery, glass

and other manufactured goods. London was expanding at this time and

in need of stone, timber, lime and bricks (many brickfields sprang

up in the Hillingdon area to meet this demand) together with sand and

gravel from the pits along the line. And when the brickfields and

sand pits were worked out they were in-filled with barge loads of the

city’s refuse. Return cargoes from London included manure, ashes

(used in brick manufacture) and imported goods from the London

docks. A summary of trade on the Canal was given during the

House of Lords committee stage of the London & Birmingham Railway

Bill in June 1832, during which one canal trader predicted that the

waterway would loose all the quick (fly-boat) trade to the Railway

together with revenue of some £97,000 p.a. (see

Appendix).

In 1836, the Company earned its peak annual revenue of £198,086,

undoubtedly boosted by the construction materials it was then

transporting to create its new neighbour, with whom a freight price

war was soon to begin. Following the opening of the Railway in

1838, the Company reduced its tolls; tonnage

rose in response, but the increase was insufficient to compensate

for the price reduction and the Company’s fortunes fell into decline. Data submitted to the Select Committee on

Railways and Canals Amalgamation in 1846 shows the extent of the

reductions, per ton, between London and Langley Mill in Derbyshire,

a route for which the Company had been able to reach tariff

agreements with the other canal companies along the line:

|

STATEMENT

of Reduced TONNAGE of Canals from London

to Derbyshire, showing the advantages which the Public

have derived by Competition between Railroads and canals.

Tonnage on the

under-mentioned Line of canals. |

|

|

Rates which they were entitled to under their Acts to

Charge, & which they did charge. |

Reduced

since 1836 to: |

|

|

GJC, 97 miles: |

|

|

N.B.—No general and scarcely any partial reduction

could be brought about until competition was established between the

railways and canals. |

|

On Sundries |

16s 3¾d |

2s 0¼d |

|

On Coal |

9s 1d |

2s 0¼d |

|

|

|

|

|

Grand Union, 24 miles:

|

|

|

|

On Sundries |

6s 0d |

5½d |

|

On Coal |

2s 11d |

5½d |

|

|

|

|

|

Old Union, 19 miles:

|

|

|

|

|

On

Sundries |

4s 9d |

5½d |

|

|

On

Coal |

2s 1d |

5½d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Leicester Nav., 16 miles:

|

|

|

|

|

On Sundries |

2s 6d |

4d |

|

|

On Coal |

1s 2d |

4d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Loughboro’, 10 miles:

|

|

|

|

|

On Sundries |

2s 6d |

4d |

|

|

On Coal |

1s 2d |

4d |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Erewash, 11 miles:

|

|

|

|

|

On Sundries |

1s 0d |

4d |

|

|

On Coal |

1s 0d |

4d |

|

In

presenting these figures to the Select Committee, the Company’s

Chairman, Sir Francis Bond Head, made some observations on the price

advantage to be had in canal amalgamation, where this could be

achieved:

Q – Do those canals of which you have now given a list, with the

prices, form one chain of navigation?

A – We have, as regards tolls, practically speaking, amalgamated

with those canals, and the result has been very extraordinary.

Q – Do you think that those canals were able to make those great

reductions in their charges in consequence of their coming to an

amalgamation?

A – They have made those reductions, and other lines of canal with

which we are connected have declined to join us, and the consequence

has been that on the distance from London to Leicester, which is 139

miles, the whole tonnage is 2s 10¾d per ton, while the whole tonnage

from London to Birmingham, which is 144 miles, amounts to nearly

7s., showing the difference between the prices on the amalgamated

and non-amalgamated lines of canal . . . . from the cheap

amalgamated line our tonnages in money have increased from £6,000 to

£15,000 and £17,000 a year; whereas from the non-amalgamated lines,

which have kept up the high tonnages, our receipts have diminished

from £80,000 to £41,000. [1]

Second Report from the Select Committee on Railways

and Canals Amalgamation (1846)

And so the Company faced railway competition with the added

impediment that, by keeping up their charges, other canal companies

on the Braunston to Birmingham line (the Oxford and the Warwick canals)

were reducing the competitiveness of long haul canal transport over

the entire route. By comparison, the London & Birmingham

Railway Company’s domain extended between those two cities, leaving its

directors free to determine their freight charges, which could be

cross-subsidized from their passenger account if necessary.

By 1844, Grand Junction Canal Company shares had fallen from their

peak of £350 in 1824, to £155; dividends from 13% in 1832 to 5% in

1849, after which they remained around the 4% mark until the

formation of the Grand Union Canal Company in 1929.

Spurred on by the impending railway competition, the Company also

embarked on a programme of service and engineering improvements.

Restrictions on night traffic were lifted, and in 1835 the Stoke

Bruerne flight of locks was duplicated to relieve congestion.

In 1836, the locks between Stoke Hammond and Marsworth Top Lock (the

Tring summit) were

also duplicated by the addition of narrow locks, the aim

being to quicken the progress of narrow boats travelling singly

which, when water was in short supply, were obliged to await a

partner in order to fill a broad lock. Water supply to the

Tring summit was also improved in 1839, when the largest of the

Tring Reservoirs, Wilstone No. 3, was opened. A further

improvement to water supply was made shortly after with the opening

of a line of back-pumping stations between Fenny Stratford and

Marsworth.

In 1846, the London & Birmingham Railway amalgamated with the Grand Junction Railway and

the Manchester & Birmingham Railway to form the London & North

Western Railway Company, the largest joint stock company in the

United Kingdom. There followed mounting concern that the

increasing railway dominance of the canal network was acting

contrary to the public interest. The Grand Junction’s then Chairman,

Thomas Grahame, summarized the position:

“This competition which commenced in 1831 (when the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway was opened), was, till the year 1845, carried on

under great disadvantage by Canal Companies. While Parliament

conferred on Railway Companies full power to act as carriers on

their own and adjacent lines of Railway to vary their charges in

order ‘to accommodate them to circumstances;’ and while Railway

Companies obtained the most ample powers to enter into permanent

agreements as to working and traffic on connecting lines of rail

fixing for a term of years or leasing to each other the tolls

exigible on their respective lines, these privileges were absolutely

denied to Canal Companies. This unjust and one sided system of

legislation has proved most prejudicial to the interests of the

public. Deprived of power to combine for self protection many

Canal Companies entered into contracts with competing Railways

sacrificing for a fixed dividend not only the just rights of

connecting navigations but the interests of the public by conceding

a monopoly of transit to the contracting Railways.”

Correspondence between the Board of Trade and T.

Grahame, Esq. Published London, 1852.

――――♦――――

THE CARRYING ESTABLISHMENT

Prior to 1845, canals were not subject to general legislation but

were regulated by the provisions of their individual private Acts.

The Canal Carriers Act (1845) was the first general canal

legislation, its aim being to place the independent (i.e. not

railway controlled) canal companies on a more equal business footing

with the railways. But the Act was both too late and flawed, for a railway company that had already acquired an interest

in a canal could redefine itself as a ‘railway and canal company’

and by this means take advantage of provisions in the legislation

that had been intended to operate against railway dominance.

But the Act did contain one provision that was to affect the

Company’s business. Although it was not specifically precluded

from acting as a common carrier, its right to do so (and that of

many other canal companies) was unclear in law. The 1845 Act

removed any doubt about canal companies being able to act in this

way [2] and to offer complementary services . . .

.

“. . . . for the better enabling them so to do, to purchase,

hire, and construct, and to use and employ, any number of boats,

barges, vessels, rafts, carts, waggons, carriages, and other

conveniences, and also to establish and furnish such haulage,

trackage, or other means of drawing or propelling the same, either

by steam, animal, or other power, or for the purpose of collecting,

carrying, conveying, warehousing, and delivering such goods, wares,

merchandise, articles, matters, and things, as to any such company

or undertakers shall seem fit . . . .”

This change to the law was followed in 1847 by Messrs. Pickford &

Co. withdrawing from long-distance canal carrying. This firm,

whose roots extend back to the 17th century (making it one of

Britain’s oldest companies), came to specialize in transporting

goods between Manchester and London by road. By the end of the

18th century it had also become an established canal carrier, and as

the canal network grew, so did the extent of its operations.

The completion of the Coventry and then of the Grand Junction canals

saw the firm’s carrying service reach Paddington Basin, and a service to

Leicester commenced in 1814 with the completion of the (old) Grand

Union Canal. The Regent’s Canal, opened in 1820, provided

Pickfords with a terminus ― the City Road Basin ― much nearer

to the

heart of the Metropolis, and here the firm established its

headquarters.

In 1817, Joseph Baxendale joined the firm, which during the depression

following the Napoleonic Wars had reached the verge of bankruptcy.

He brought with him two partners and the capital needed to develop

Pickfords into a carrier operating on a national scale. Baxendale was endowed with much drive and determination, as well as

being a skilled manager and accountant:

“. . . . when he began his career as a carrier, the highways of

the country were to a great extent little better prepared for

traffic than the worst of our cross-roads are now. To conduct

the business thoroughly relays of horses for the fly vans were as

necessary as for the ordinary coaching traffic of the time, and

equally so for the fly boats which traversed the canals: to this a

large staff of energetic, well-paid agents had to be added, and to

these the working labouring body, a small army of itself.

Hours on hours were withal occupied on the transit of goods which is

now effected by rail in a fraction of the time.

In the conduct of the business his energy and judgment were equal to

the necessity. Night after night he traversed the roads in his

special travelling carriage, on the look-out to see that none of his

employees slackened in their duty, as often as not passing by

by-roads so as to double back on the drivers, who in consequence

never knew whether he was before or behind them; so, general

vigilance thus became the rule of all.”

The Times, 6th January,

1873

Baxendale foresaw the impact that the railways would have on the

freight business, and in 1847 moved the firm away from long-distance

canal carrying to concentrate on rail freight. [3]

The firm retained its premises at City Road Basin and continued to

handle some lightered goods between the docks, City Road, and their

Camden Depot, but its use of canal transport was greatly reduced.

In that year Thomas Grahame replaced Sir Francis Bond Head as

Company Chairman, a change that was probably brought about by

differing boardroom opinions over whether the Company should enter the

canal carrying trade as permitted by the 1845

Act. Under the new leadership a wholly-owned subsidiary, the Carrying Establishment, was

created, the Board regarding the Company’s

entry into canal carrying as “an act of self preservation”.

To fund this development further capital was raised by the sale of

£104,550 of 6% preference shares, part paid, the first call raising £26,137.

Bryan Pagett Gregson was

appointed General Manager of both the Carrying Establishment and the Canal.

He set up a formidable carrying organisation, taking over the

canal businesses of Messrs Pickford & Co. and Wheatcroft & Co. among

others, thereby providing the new Carrying Establishment with depots

in Birmingham, Dudley and Wolverhampton on the Birmingham Canal

Navigations. The Company entered the carrying trade on 1st

December 1847, having made arrangements to facilitate ‘through traffic’ at mutually advantageous rates

of toll with the Oxford ― for once being co-operative ― Coventry,

Warwick & Napton, Warwick & Birmingham, Grand Union and the

Leicestershire & Northamptonshire Union canals. The new firm’s advertising proclaimed daily fly-boat services from

Paddington to Leicester, Loughborough, Derby, Burton and Nottingham,

the carriage charges including collection, delivery and reasonable

warehousing. It was also planned to recommence daily fly-boat

services to Manchester and Liverpool in the New Year, routes on

which traffic had ceased following Pickford’s withdrawal from the

trade.

Although the Carrying Establishment undoubtedly stemmed the haemorrhage

in revenue caused by Pickford’s withdrawal from the business, it never produced the expected

returns. During its first six months of operation carrying

commenced between London and Manchester, and between London and

Derby, Leicester and Nottingham. According to the half-yearly

report, trading results were no more than “satisfactory”.

In the case of Manchester, “a considerable portion of the trade

had been restored”, while on the second route “there was steady

progress”; no mention is made of the planned Liverpool service.

Carrying had so far been confined to Manchester and to the midland

counties, and the Company’s efforts to gain new business carrying coal

and other heavy traffic appears to have alarmed at least one London

& North Western Railway Company shareholder, whose correspondence

with the Chairman of the newly formed railway company was

subsequently published:

“. . . . a rival [to the LNWR] started into existence

where none had been calculated. The Canal Companies having had

a foretaste of what was in store for them, applied to and obtained

permission from Parliament to become Carriers on their own account ―

a privilege which up to that time they had not possessed. The

result has been that the Grand Junction Canal Company, to preserve

itself from destruction, is competing for the Goods traffic between

London and the North, at rates so low that the Railway Company

cannot venture to touch them, much less to drive the Canal Company

as competitors from the field. When this unseemly strife will

end no man can foresee. Life and death are in the balance so

far as the Canal Company is concerned; excessive loss in character

and fortune in as far as the Railway Company is affected. . . . The

London and North Western Railway Company as you are aware is at the

present time carrying goods from London to Manchester at 40s per

ton! The Grand Junction Canal Company are doing the like by

Canal at 30s per ton! As both undertake to collect and deliver

without extra charge the real fact is that the Railway charge is 30s

per ton the Canal 20s per ton the difference 10s being the cost of

collection and delivery.”

Letter to George Carr Glyn Esq. MP, Chairman of the

L&NWR Company,

from John Whitehead (London, 15th November). Published London, 1848

[4]

By June 1849, the Company was able to report that canal trade was

improving and that carrying was increasing ― for the six months

ending in December, 1848, 521,783 tons of merchandise were

transported generating revenue of £41,095 ― but that after meeting

operating expenses, further setting up charges and the 6% dividend

due on the preference stock, canal carrying turned in a loss.

The Chairman’s report does not dwell on its extent, but warns

shareholders that the outturn from carrying did not represent new

business, but retained business that might otherwise have been lost:

“Nothing short of the company taking the conveyance of goods into

their own hands could have prevented a large portion of that revenue

from being abstracted from the Canal; because private carriers, by

whom the trade was formerly conducted, have neither the means of

meeting the competition of powerful railway companies, nor

sufficient permanent interest in the canal to induce them to make

the sacrifices necessary to do so with effect.”

But on another important front, aggressive railway competition had

subsided ― for the time being:

“The committee are happy to say that competition between the

North-Western Railway Company and the canal has, by recent

arrangement, been confined within legitimate bounds; and they have

reason to hope that it will not be renewed in a hostile spirit or

form.”

Address to the half-yearly General Meeting of the

GJCC, June, 1849.

By the end of the year the shareholders were being advised that the

carrying business continued to extend, and that coal and other heavy

traffic . . . .

“. . . . has recently exhibited indications of revival.

Great savings in the carriage of coal by water have been affected by

the company; and the fact is beginning to be known that many of the

inland coals are no whit inferior in quality to the seaborne, while

they possess some peculiar advantages, besides being considerably

cheaper in price. The demand upon the committee for the means

of bringing these coals to the London market have lately being more

than they have been able to comply with . . . .” [5]

Address to the half-yearly General Meeting of the

GJCC, December, 1849.

The half-yearly report goes on to explain that some reorganisation

of the carrying department was necessary to separate it from the

management of the canal and its works, and that Gregson had agreed

to continue as Canal Manager at a reduced salary. A

replacement would be found to manage the carrying operation “at

an expense smaller than the proportion of salary relinquished by Mr.

Gregson”. Gregson appears to have left the Company’s

service in 1850 [6] to return to the Lancaster

Canal, where he completed his long canal career in the role of

Secretary.

――――♦――――

RAILWAY PRICE WARS

In 1846, the Birmingham Canal Navigations allied themselves to the

London & Birmingham Railway [7] and, following the

railway merger in that year, with the newly formed London & North

Western Railway. The Act authorising this alliance specified

that the London & North Western would rent the Birmingham canal

system in exchange for a guaranteed 4% p.a. dividend, which the the

Railway would make up from its own resources if necessary.

Subsequently, under railway control, canal tolls were increased on

this section of the through route to the north.

An outcome of this canal/railway alliance appears to have been

that by 1852, the “arrangement” that had existed

between the Grand Junction Canal and London & North Western

Railway companies had lapsed, and hostilities had recommenced. In

referring to the Railway’s control of the Birmingham canals, the

Grand Junction‘s Chairman, Thomas Grahame, had much to complain

about:

“From a link in the chain of water communication connecting the

important district of Birmingham and its vicinity, Staffordshire,

Worcestershire, and the North, with London and the South, the

Birmingham Canal has been converted into a barrier to that

communication. The tolls exacted on that navigation are

imposed in the view of extinguishing traffic, not of obtaining

revenue. Were the tolls on the other Canals forming the water

route from the Birmingham district and beyond to London and the

South, the same as on the Birmingham Canal, all transit by the water

route must be at an end . . . . The tolls which they thereby

obtained power to perpetuate on the lines of the Birmingham Canal

are in many cases double and treble the entire freight chargeable on

the rival and parallel Railway route.”

Correspondence between T. Grahame Esq. and the Board

of Trade, London, 2nd April, pub. 1852

By August, 1853, the Morning Post was able to report that

“the Grand Junction Canal, notwithstanding the rivalry of two lines

of railway between Birmingham and London [i.e. the London &

North Western and the Great Western railways], was seldom or ever

so fully employed as at the present moment”. The

smouldering price war was soon to reignite, probably at the

instigation of the Grand Junction, which was attempting to attract

the South Staffordshire coal trade. At the February meeting of

London & North Western shareholders, a complaint was raised that the

railway company’s directors were pursuing every means of increasing

their traffic regardless of whether it resulted in profit. In

particular, that their rivalry with the Grand Junction was such that

each was carrying goods at such reduced rates that neither could

make money:

“The Grand Junction Canal Company have announced that from the

8th of this month the rates on all class of goods to and from London

and Birmingham will be 20s. per ton. The rates charged by both

railway companies to London have hitherto been 27s. 6d. per ton, and

to Liverpool 20s.; by the Grand Junction Canal to London 25s. 10d.

An old competition, which it was expected was mutually abandoned,

has thus been revived.”

The Times, 14th

September 1857

But the price war extended beyond these two competitors. The

London & North Western was also in hot competition with the Great

Western Railway for the Birmingham freight trade, their Goods

Manager informing the press that he had been instructed to offer

reduced rates comparable to those of the Great Western “however

low these rates may be”. By the beginning of 1858, the

damaging terms on which each party was doing business were such that

normality had to be restored:

“One source of competition, however, in the South Staffordshire

districts, which arose from the Grand Junction Canal Company having

lowered their rates and diverted a large portion of the trade to

water conveyance, while the two railway companies were charging

agreed higher rates of freight, has been already terminated.

The rates between South Staffordshire and London have been again

raised to a scale which will admit of moderate profit to the

companies without impeding the full course of the traffic . . . . No

efforts will be spared to mature and give effect to those

arrangements, as well as to carry forward in a liberal spirit other

negotiations tending to secure traffic at remunerative rates,

without hostile competition.”

The Times, 11th February

1858

――――♦――――

THE BRENTFORD DOCK RAILWAY

In 1859, the Company lost a useful source of revenue with the opening

of the 4½-mile branch railway between Southall and Brentford Docks.

The problems that the Great Western Railway needed to overcome

typifies the drawbacks of canal transportation ― slowness, drought,

and ice, added to which in this particular case were the

costs of railway to canal transhipment and canal tolls:

“Hitherto all the heavy traffic upon the Great Western Railway

destined for the Port of London has left the main line at

Bull’s-bridge, whence it has been taken down the Grand Junction

Canal to Brentford. For a long time past the means of transit

thus afforded have proved quite inadequate for the greatly increased

traffic which the opening up of the Welsh coalfields and the

connexion of the Great Western line with Birmingham . . . . and

other places have brought upon it. Between Bulls-bridge and

Brentford there are upon the canal no fewer than 11 locks, and the

delay which these occasioned was enhanced in winter by frosts and in

summer by droughts. The tonnage dues also were heavy, and all

these circumstances affected very prejudicially the goods and

mineral traffic upon the trunk line. These considerations led

to the construction of the new railway and dock, which were

yesterday opened for public traffic.”

The Times, 16th July

1859

――――♦――――

OTHER LINES OF BUSINESS

While the railways were slowly but inexorably soaking up the

Company’s established business, new opportunities did open up from

time to time, one being leisure. Boat excursions on the Grand

Junction Canal were not new, and sketches from the Canal’s early

days show parties setting out from Paddington Basin. Whether

these trips were regular summer offerings and whether they had any

material impact on Company revenue is not known, but they did on

occasions attract the attention of contemporary commentators:

“The adaption last summer of one or two of the barges for

pleasure boats to take parties for excursions on the Paddington

(Grand Junction) Canal was found to be so palatable to the larger

body of the respectable working classes who patronized the

speculation, that this summer the number of such pleasure boats has

been increased, and, aided by the material advantage of genial

weather, the canal . . . . has become quite a pleasure stream, and

the scene which presents itself at Paddington . . . . by the arrival

and departure of parties of these pleasure trips down the canal, is

of the most lively and cheering character. The barges are

entirely devoted to the purpose, and furnished with seats covered

and ornamented, and being gaily decorated are not unsuitable

vehicles for the enjoyment of the parties, who include hosts of

respectable women and children, who, with their provisions and other

adjuncts, avail themselves of the novel means of making water

excursions several miles from the metropolis.”

The Times, 11th July

1849

A leisure

cruise leaving Little Venice, Paddington, 1840

Another writer, who could not help but observe that canals were a

thing of the past, added an interesting social perspective to his

view of this piece of commercial acumen:

“The glory of the first public Company which shed its influence

over Paddington has in a great measure departed; the shares of the

Grand Junction Canal Company are below par, though the traffic on

this silent highway to Paddington is still considerable; and the

cheap trips into the country offered by its means, during the summer

months, are beginning to be highly appreciated by the people, who

are pent in close lanes and alleys; and I have no doubt the

shareholders’ dividends would not be diminished by a more liberal

attention to this want.”

Paddington Past and Present,

William Robins (1853)

An entirely new source of revenue to appear at this time ― and one

that continues to the present day ― was that of leasing wayleave to

telecommunications companies to erect their telegraph circuits along

the towing paths.

A form of electric telegraph developed by Cooke and Wheatstone

received its first public demonstration in 1837 using a line set up

between Euston and Camden stations, the test being witnessed by none

other than the railway’s Chief Engineer, Robert Stephenson. By

1846, The Electric Telegraph Company had set up in business to

provide overland telegraph services and it was soon followed by

competing companies among which was The United Kingdom Telegraph

Company. Formed in 1860, this company attracted business

through its flat-rate charge of 1s., irrespective of distance, for a

twenty-word message. It soon acquired the sobriquet ‘The

Shilling Telegraph’, although this was misleading, for message

collection and delivery charges could more than double the 1s.

transmission charge:

“The construction of new lines of telegraph proposed by the

United Kingdom Telegraph Company was commenced yesterday at Acton.

The first sod was cut, and the first pole erected, by the directors

of the company. This company proposed to adopt the system of

uniform charges, on the principle of the penny postage; messages of

not more than twenty-five words are to be sent between all the

principal towns and cities in the United Kingdom at the uniform

tariff of one shilling. From Acton, the telegraph lines will

be carried along the road to Oxford; thence the wires will be

carried on posts along the canals, the proprietors of which have

given the requisite permission for setting up the poles on their

land. The principal towns to be provided for by the new

telegraph company will be, in the first instance, Oxford,

Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, Leeds, and Hull,

including, of course, some of the smaller towns which lie between

the more important places of business on the route, the line

followed being principally that of the existing canals. The

telegraph will be aerial, and not subterranean, experience having

proved that wires supported on posts can be more generally relied

upon for efficiency than those which are laid underground; where

convenient to do so, the wires will be carried on the house-tops.”

Morning Chronicle, 20th

November, 1860

Following a challenge in the courts from its competitors, the

‘Shilling Telegraph’ was prevented from laying its trunk cables

beneath public highways and had to resort to conveying them along canal towing paths.

In later years, lines of telegraph poles disappearing into the

distance were to become a common

feature in canal-side photographs.

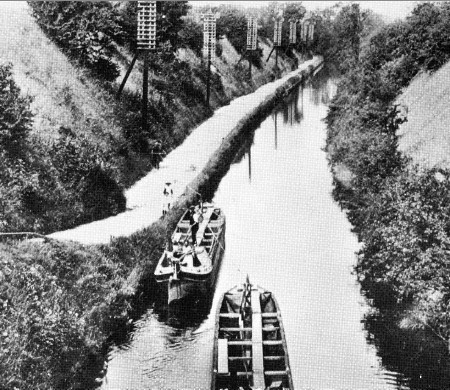

|

|

|

Telegraph poles

stretching off into the distance in Tring cutting.

A fibre

optic cable now lies beneath the towpath. |

During its first year of operation (1861), the telegraph company installed

circuits between Liverpool and Manchester, and London and

Birmingham. Their line between London and Birmingham followed

the Grand Junction Canal from Brentford to Braunston, with circuits

to Leicester and Northampton following the towing paths of those

waterways. From Braunston, the line followed the Oxford and

Warwick canals, and the Birmingham Canal Navigations. The

circuits to Manchester and Liverpool departed along the Birmingham

Canal Navigations to join the Trent & Mersey Canal, and then

followed the Bridgwater and the Leeds & Liverpool canals, the tails

into the city centres extending from the canals’ terminal basins.

Circuits were also laid into the London docks along the Paddington

Branch and the Regent’s Canal.

However, the public became increasingly discontent with the

limited accessibility, frequent delays, poor transmission quality

and high charges of the privately run telegraph networks generally,

and the government decided to act. Under the Telegraph Acts of

1868 & 69, the overland telegraph companies were nationalized, the

Postmaster General taking (monopoly) control on 28th January, 1870.

However, the wayleave agreement with the Grand Junction Canal

Company remained in force:

“On such Acquisition as aforesaid the existing Agreements between

the Company of Proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal and the

United Kingdom Telegraph Company (Limited) shall determine, and the

Postmaster General shall have a perpetual Right of Way for his

Poles, Wires, and Telegraphic Apparatus over the whole of the Canal

Company’s System of Navigation as it now exists, or may hereafter be

altered or converted, but so that such Poles, Wires, and Apparatus

shall not interfere in any way with the Convenience and working of

the Canal or its Alteration from Time to Time, or Conversion in

whole or in part into a Railway, or obstruct the working of the

Traffic thereon, and in consideration thereof he shall pay to the

Canal Company such Sum by way of yearly Rent as shall be determined

by Agreement . . . . and the Postmaster General shall also transmit

to their respective Destinations all Messages of the said Canal

Company bond fide relating to the Business of that Company between

any Places in the United Kingdom free of Charge.”

Extract from the Telegraph Act (1868)

The clause “or Conversion in whole or in part into a Railway”

provides an interesting insight into the prevailing view of the

future of canals.

Canals continue to carry telecommunications circuits. During

the 1990s, British Waterways entered into new telecommunication

wayleave agreements, the outcome being that many hundreds of miles

of inter-city fibre-optic circuits now lay buried beneath Britain’s

canal towpaths.

――――♦――――

STEAM PROPULSION

Another hoped-for boost to revenue adopted by the Company during the

1860s, was the use of steam power to move greater loads more

quickly, thus improving

competitiveness with the railways.

The use of steam power on canals dates back to the early years of

the nineteenth century, when a stern-wheel paddle tug, the

Charlotte Dundas, designed by William Symington, was

demonstrated on the Forth and Clyde Canal. At the time, canal

banks were not protected by walls or sheet piling, and fears that

the wash from powered craft would cause bank erosion ended the

trial; indeed, this remained an obstacle to the use of powered craft

on canals for many years. But trials continued nevertheless.

On 29th September, 1826, the Tring Vestry Minutes record that

“The first steam boat passed down the Grand Junction Canal”.

Elsewhere, experiments with steam propulsion took place, which

despite its apparent advantages met with the usual civil engineering

objection, bank erosion. However, in 1838 a notable experiment

took place that departed from the impracticable ‘paddle wheel’

propulsion, utilising instead an early application of the ‘screw

propeller’ to a design by John Ericsson. [8]

Twin screw propellers were fitted to an ordinary canal boat, the

Novelty, which, on 28th June 1838 set off from London along the canals to

Manchester, later returning by way of Oxford

and the Thames:

“We have already stated that the Novelty is the hull of an

old canal boat. Her form, to those unacquainted with the build

of those boats, will be better understood when we state that her

length is about seventy-four feet, with seven feet six inch beam,

she is heavily constructed, and when loaded draws about two feet of

water. We noticed that her engine is high pressure, and of

four horses’ power, supplied with steam from a small locomotive

boiler. The boat is fitted with a species of paddles, already

described, but perhaps better known as Ericsson’s propellers, in

substitution of the side paddles of the old steamers — which are

constructed so as to propel without raising a surge injurious to

canal banks, and so as to pass through the narrow locks with ease

and safety — objects hitherto unattained, and deemed impracticable .

. . . During the trip no injurious ripple was produced by the

propellers; but where the water was shallow, a ripple, caused by the

displacement of water by the boat, followed midway, and considerably

impeded her progress. With deeper water her speed accelerated,

and on the Thames she is said to have achieved a rate varying from

eight to nine, and even up to and exceeding ten miles per hour. . .

. It is perhaps premature to speculate on the great revolution which

the success of this experiment, and the consequent adoption of steam

power on canals would occasion . . . . are of course contingent on

the success of the mechanical invention, in its application to

canals, and on the degree of cordiality with which canal proprietors

approve of a change which some of them may imagine (whether justly

or not we do not affirm) will cause greater wear and tear to their

property than to which the ordinary mode of horse towing at present

subjects them.”

Manchester Guardian,

18th July 1838

Although nothing came of the experiment, it served to demonstrate

the considerable advantages in practicality and efficiency of screw

propulsion over paddle wheels. [9]

The Guardian’s report is also interesting for describing the

effects of shallow water on speed. Hydrodynamics is a branch

of physics that was only then becoming understood. To the

early canal engineers, determining the dimensions of a new canal was

simply a matter of providing sufficient depth for full loading and

sufficient width to permit a pair of barges to pass. But a

barge that moves with little clearance above the canal bed, and/or

about its sides, is unduly affected by hydraulic drag. Its

movement creates a reverse flow of water that must take place in the

confined space between the barge and the canal bed and banks, which

increases the resistance to motion. Hence, for a given motive

power, a barge in the confines of a narrow and shallow canal moves

more slowly than it would in a wide and deep canal. Drag is

particularly affected by anything that serves to reduce a canal’s

depth, such as shoals (i.e. the need for dredging), drought

and leakage. Thus, when depth is reduced by a comparatively

small amount, for example from 4.0 to 3.9 feet, the corresponding

drag on a barge drawing 3.5 feet is increased by about 25 percent.

The next notable steam propulsion trial on the Grand Junction Canal

took place in December 1851. Recognising that higher speeds would increase the drag inherent in a narrow channel ―

and would also increase bank erosion ― an alternative strategy was

to harness the steam engine’s ability to sustain tractive effort by

hauling much heavier loads, but at the usual horse-dawn speeds of 2

to 2½ mph. And so a further experiment was carried out on the

lockless section of the Canal between Bull’s Bridge and Paddington

by a steam-powered tug hauling a train of eight barges laden with

bricks. The outcome was that a speed of 2¼ mph was attained

“without exciting the slightest wave or perceptible disturbance in

the water”. When repeated the following day, the test met

with equal success, the Times correspondent reporting that

“it was universally admitted that much benefit to canals must result

from the adoption of this economical motive power; from it the heavy

traffic, now seriously menaced by railway competition, must equally

derive great and immediate advantage”. Despite this

apparent success, the Company’s adoption of steam power was anything

but immediate and further tests took place during the 1850s, but

without a decision being reached.

|

From a slightly later era to that

being discussed, the Steam tug Buffalo at Bushell

Brother’s boatyard at Tring.

The

Buffalo is known to have been owned by William Mead & Co., a

family that leased wharves at Paddington

and owned interests in the

brickfields at Iver, so she may have been used for hauling barge

loads of bricks on the Long Level to Paddington’s South Wharf. In his

autobiography, John Mead refers to her purchase ― “We heard that

the Birmingham Carrying Company had 2 tugs for sale, the Antelope

and the Buffalo. The Canal

foreman was against having these, but

the price was low and we bought them, and they were a success.” Mead

is vague on the date of this transaction, but it appears to have been around 1898. |

Towards the end of 1859, the Company’s Chairman and Surveyor visited

the Leeds & Liverpool and the Forth & Clyde canals to examine their

use of steam tugs. They gained a favourable impression in

consequence of which the Company decided to fit an existing canal

barge with a 6hp steam engine. On trial, the Pioneer

proved capable of towing six barges of total weight 300 tons.

It was claimed that she and her butty could travel from London to

Birmingham and half way back on a full bunker of coal (2½ tons), and

at a cost 25% below that of towing by horse. So satisfied was

the Board, that in December 1860 they placed an order for “three

new iron boats, three new wooden boats with iron sterns and three

new wooden boats with iron sheets at the stern all fitted with steam

engines and screws similar to those in Pioneer . . . . that there be

built two iron tug boats of greater power for the purpose of

conveying the trade on the Canal to and from Paddington and Cowley

Lock” [10] ― the differing hull designs

probably resulted from there being no precursor on which to base a

reliable design, which had to be derived by trial and error.

Because the Carrying Establishment’s cash resources were unlikely to

cover the cost of construction, arrangements were made with Praed &

Co., the Company’s bankers, to advance up to £4,000 for the purpose.

By June, 1863, the Chairman was able to report that the Carrying

Establishment had twenty-four steamers and three tugs at work, and

it was hoped to increase the number to “enable them to dispense

with the use of horses on the Grand Junction Canal, as well as to

convey its traffic on the River Thames with greater despatch and

economy”.

|

|

|

The eventual

development of the steam narrow boat.

‘President’ was built in 1909 by Fellows Morton and

Clayton at their dock at Saltley, Birmingham.

The boiler and bunker took up space, and the plant

required the attention of an engineer. |

Although steam power soon became established, the Carrying

Establishment remained a substantial owner of horses. At the

beginning of 1870 they owned 140, which the half-yearly report

claimed where being fed according to a plan devised by the General

Omnibus Company, which resulted in a saving in provender of £4 per

horse per annum and that “the Company’s horses were in much

better condition than previously”. Economies were also

being made in the way boatmen were paid, which changed from a per

trip basis to one based on the tonnage carried. This, it was

hoped, would encourage them to pick up “all the traffic they

could along the canal”.

――――♦――――

THE END OF THE CARRYING ESTABLISHMENT

On 2nd October, 1874, a disaster occurred that brought the Company’s

carrying business to a sudden end. In the early hours of the

morning a train of six barges left the Company’s wharf in City Road

Basin on the Regent’s Canal drawn by the steam tug Ready.

Third in the line was the barge Tilbury, carrying among other

items a quantity of petroleum and some five tons of gunpowder, most

of it being in barrels but some was contained in a box. When

passing under the Macclesfield Bridge the Tilbury blew up killing

her crew of three and causing extensive damage to nearby property,

fortunately mitigated by the blast being deflected by the small

cutting in which the explosion occurred. It was thought that

an oil lamp might have ignited petrol vapour that had gathered in

the hold.

Initially the Company decided to contest liability for the

damage, but having lost a court case it was resolved that “the

damage done to property be admitted and that parties claiming

compensation be called upon to send in particulars for investigation

with a view to settlement”. Claims amounting to £80,000

were made, which were settled with the aid of a £40,000 loan from

Praeds, the Company’s bankers.

|

Macclesfield Bridge ― known as ‘Blow-up Bridge’ ― on the Regent’s Canal,

the site of the great explosion on 2nd October, 1874.

The great Doric iron columns are the originals. |

If the Regent’s Canal explosion was not sufficient, on 21st

September 1875, the boiler of the steam tug Pincher, moored

at Yardley Wharf near Stony Stratford, blew up killing both

engineers, badly injuring the master and wrecking the steamer, which

sank. The Pincher, on her way from

London to Birmingham laden with 13 tons of potash and towing a train

of five boats, had stopped at Yardley Wharf to discharge grain. She had been lying there for about an hour when the

explosion

occurred ― its cause was never established.

In March 1876, the Company resolved to discontinue its carrying

trade, which ceased from 1st July. The Carrying

Establishment’s assets were sold to, among others, The London and

Staffordshire Carrying Company, the proceeds of this sale (£2,352)

probably going towards paying off the £5,000 outstanding to Praeds,

whose account was settled in October, 1877. And so the Company

withdrew from a business that they could not turn into a success,

but which others did.

The London and Staffordshire Carrying Company was later absorbed into Fellows, Morton & Clayton (often referred to as

FMC), which became England’s largest and best-known canal carrier.

FMC’s roots go back to 1837, when James Fellows, then an agent for a

canal carrier, set up in business on his own account.

Following Fellow’s death in 1854, his widow continued the business

until her son Joshua was old enough to become a partner. By

1855 the firm was transporting 13,000 tons of iron castings

annually between London and Birmingham, and by the early 1860s the

fleet numbered some 50 boats. In 1876, Joshua Fellows was joined by

Frederick Morton who brought with him the capital necessary to

expand the business, the company then becoming Fellows Morton & Co.

In 1889, Thomas Clayton joined the firm, which then became Fellows,

Morton & Clayton Ltd. As part of the deal, Clayton’s general

cargo fleet [11] was taken over by FMC, whose

fleet now numbered some 11 steamers and 112 butties. The firm

had their own dockyards at Saltney, Birmingham, where their steamers

were built, and at Uxbridge, which specialised in wooden

construction.

By 1920, the FMC fleet had grown to 21 steamers (then

being phased out), 25 diesel-powered narrow boats and 162 other

craft. Following WWII, canal business declined sharply due to

road and rail competition. In 1947 the firm experienced their

first ever trading loss, and in the following year the directors

decided to place the firm into voluntary liquidation, [12]

its assets being sold to the newly formed Docks and Inland Waterways

Executive of the British Transport Commission.

――――♦――――

CANAL LEGISLATION

The Canal Carriers Act (1845) had cleared the way for canal

companies to become common carriers. More legislation was to

follow during the latter part of the nineteenth century aimed at

preventing the railway companies exploiting their increasingly

monopolistic position as freight carriers. In an attempt to

curtail the railway companies’ ability to damage their canal

counterparts, thereby strengthening their virtual monopoly, several

Acts included provisions designed to remove the obstacles to ‘through

working’ across a number of different canal systems.

The Railway and Canals Traffic Act (1854) addressed mainly

railway-related problems, but so far as canal carrying was

concerned it aimed to check the railways’ gradual stifling of canals by placing an obligation on canal companies “to afford all

reasonable facilities for the receiving and forwarding, and

delivering of traffic” without delay, to and from their canals.

This provision sought to end the practice whereby a monopoly

operator could deal unfairly with some customers. It applied

particularly to canal companies that were either owned or controlled

by a railway company, and which owned short sections of much longer

through routes over which they could charge unreasonably high tolls.

But as “reasonable” was open to interpretation, the provision

was easy to avoid, thus rendering the Act (within this context) of

little consequence.

The 1854 Act was followed four years later by further legislation

aimed at preventing, without legislative sanction, the virtual

amalgamation of canals with railways. It addressed the

situation whereby a railway company ― that was also a ‘canal company’

by virtue of having previously purchased a canal ― from acquiring

control of an independent canal company under a lease, rather than

by outright purchase.

In 1873 a further Railway and Canal Traffic Act created the ‘Court

of the Railway and Canal Commission’ whose role was to enforce the

1854 Act, and it set out the duties of the Commissioners. This

Act gave to either party in a dispute between a railway and a canal

company the right to refer the dispute to the Commissioners for a

decision, and provided explanations for determining what

constituted ‘reasonable’ action. It also prohibited railway

companies from making agreements with canal companies for the

purpose of controlling tolls, rates or traffic on any part of a

canal and, with regard to railway-controlled canals:

“Every railway company owning or having the management of any

canal or part of a canal shall at all times keep and maintain such

canal or part, and all the reservoirs, works, and conveniences

thereto belonging, thoroughly repaired and dredged and in good

working condition, and shall preserve the supplies of water to the

same, so that the whole of such canal or part may be at all times

kept open and navigable for the use of all persons desirous to use

and navigate the same without any unnecessary hindrance,

interruption, or delay.”

Although very late in coming, this potentially onerous requirement

was one that canal-owning railway companies had not anticipated when

they entered the canal business.

The year 1894 saw yet a further Railway and Canal Traffic Act.

This legislation further constrained railway dominance over the

canal trade by making it difficult for freight charges to be

increased once they had been lowered. In effect, the Act

removed a strategy employed by railway companies, which was to

exploit their ability to cross-subsidize freight charges from

passenger revenue and hence to undercut canal charges artificially

until such time as the lower charges had destroyed a competing canal

company. The railway company could then restore rates to the

previous levels. But the Act was too late in coming, for the

railways’ damage to the independent canal system was by then

complete:

“No traffic can get out of the centre of England without

encountering railway-owned or controlled canals, e.g. South

Staffordshire Iron Traffic arises on the Birmingham Canal, and if

destined for Liverpool, must pass by the Shropshire Union or Trent

and Mersey Canal, whilst the Cannock Coalfield has no means of water

transit but the Birmingham Canal, the North Staffordshire Pottery

District and Burton-on-Trent have only the Trent and Mersey Canal,

whilst traffic from the Warwickshire Coalfield is hemmed in, except

to London, by the Birmingham and Trent and Mersey Canals, all

railway owned or controlled.”

Digest of the Report and Recommendations of the Royal

Commission on Canals (1913)

The canal companies’ attempts to attract long-distance trade can be

illustrated by comparing the tolls charged by the Grand Junction and

associated canals on the London to Birmingham route, as authorised

in their Acts, with the amounts actually charged, which show the

significant reductions in toll that the independent canal companies

had made in order to attract through trade:

|

Grand Junction

Canal (101 miles) – toll per ton: |

|

|

Authorised: |

Actually charged: |

|

Bricks: |

8s

4½d |

7d |

|

Timber: |

14s 9½d |

7d |

|

Grain: |

16s 10¾d |

2s 6d |

| Iron: |

14s 4¾d |

1s 8d |

|

Oxford Canal (7

miles) – toll per ton: |

|

|

Authorised: |

Actually charged: |

|

Bricks: |

4s

4d |

3d |

|

Timber: |

4s 4d |

3d |

|

Grain: |

4s 4d |

3d |

| Iron: |

4s 4d |

3d |

|

Warwick & Napton

Canal (15 miles) – toll per ton: |

|

|

Authorised: |

Actually charged: |

|

Bricks: |

1s

10½d |

7½d |

|

Timber: |

1s 10½d |

1s 3d |

|

Grain: |

1s 10½d |

1s |

| Iron: |

1s 10½d |

7½d |

|

Warwick &

Birmingham Canal (22 miles) – toll per ton: |

|

|

Authorised: |

Actually charged: |

|

Bricks: |

2s

9d |

7½d |

|

Timber: |

2s 9d |

1s 3d |

|

Grain: |

2s 9d |

1s |

| Iron: |

2s 9d |

7½d |

|

Birmingham Canal

– railway controlled - (allowance for 10 miles) – toll per

ton: |

|

|

Authorised: |

Actually charged: |

|

Bricks: |

1s

2d |

1s

2d |

|

Timber: |

1s 2d |

1s 2d |

|

Grain: |

1s 2d |

1s 2d |

| Iron: |

1s 6d |

1s 6d |

|

Report

of the Parliamentary Select Committee on Canals (1883) – Appendix 14 |

By

comparison, the figures for the Birmingham Canal illustrate the

stifling effect that this railway controlled canal was having on

London-bound traffic ― indeed, on all traffic passing through

Birmingham ― its tolls being significantly higher in pence per mile

that those of the independent canals along the route.

Another measure of the decline of long distance traffic on the Grand

Junction Canal was the amount of coal shipped into London from the

Midlands and North of England by canal and railway respectively.

The tonnages for the period between 1852 and 1882 show that the

Grand Junction’s share of this trade fell dramatically, which is

especially significant, for coal originally comprised a large

percentage of all canal traffic:

|

|

1852 |

1882 |

|

By canal |

33,000 tons |

7,900 tons |

|

By railway |

317,000 tons |

6,546,000 tons |

|

From the Report of the Parliamentary

Select Committee on Canals (1883) |

When the Royal Commission on Canals sat in 1906, the figures

they were presented with for the weight of coal being shipped

into London were, by rail 7,137,473 tons (45.6%); by sea

8,494,234 tons (54.3%); by canal 18,681 tons (0.119%); and

overall for the period 1880 to 1905, 0.1% of the coal shipped to

London came by canal (rail and sea sharing almost equal

proportions of the balance).

――――♦――――

GEORGE SMITH AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS

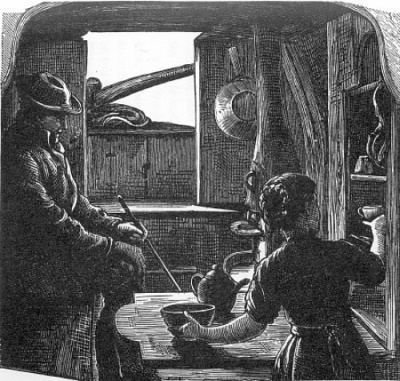

|

|

|

Interior of a narrow boat’s cabin,

from the door. |

In 1878 and in 1884, legislation appeared aimed not at regulating

the commercial aspects of the canal carrying trade, as had earlier

Acts, but the lives of those who manned the boats and for whom they

were their home. The person whose name is linked indelibly

with the Canal Boats Acts is the Wesleyan social reformer George

Smith.

“During the whole of my enquiries among the boaters I

only remember in one instance being subjected to anything

like an insult from the boaters themselves, and that was at

Moira one Saturday, some three years since, by a woman who

was almost big enough to fill the cabin herself;

notwithstanding this, she managed to pack somehow and

somewhere a big husband, a poor little cripple and three

other children in the cabin, so as to be able to dine at a

small cupboard door 2 feet 6 inches by 2 feet, and to sleep

in a place not large enough for a cottager’s hen-roost.

She found fault with me for saying that they were dirty, and

wore dirty linen and washed in and drank out of the dirty

‘cut.’ It was then four o’clock, and raining very

heavily, and she was washing the clothing for the Sunday,

and the children partly dressed camping round a fire on the

path. I asked her how she was going to dry the clothes.

Her answer was, that she was ‘going to light a fire in the

middle of the hut to dry some of them, and the rest I shall

hang before the cabin fire, to dry while we are asleep.’

I pointed out to her what the colour of the clothes would be

after they had been ‘smoked,’ and the danger she was running

with reference to their health by drying the clothes in the

cabin while they were asleep in bed. Hinting these and

a few other things to her in a kindly spirit, and a few

pence given to the children, easily made us friends, and we

have been friends ever since.”

Our Canal Population,

George Smith (1875)

|

|

|

Interior of a narrow boat’s cabin,

from the bed. |

Smith was born Tunstall, Staffordshire, on 16th February 1831.

The son of a brick-maker, it was while working as a child labourer in the

appalling conditions of the brickyards that fired Smith’s social

conscience. Self-educated, he campaigned tirelessly for

conditions to be improved, eventually succeeding in 1871 with the

passage in the Factories and Workshops Act, [13]

which required brickyards to be inspected and which regulated the

employment of juvenile and female labour. By then Smith had

risen to the position of colliery manager, but his refusal to

relinquish social campaigning cost him his job, and years of poverty

were to follow.

Despite this misfortune, Smith next turned his attention to living

conditions on canal boats. Families had lived on the canals

from their earliest years, particularly on the larger boats and

where trade involved journeys that usually took many days to

complete, but the pay was good and boatmen’s families mostly lived

ashore. Living afloat became more common following the

Napoleonic Wars and the advent of the railways, both events leading

to a fall in earnings. Economies could be made if the family

moved into the narrow boat’s rear cabin (10 ft. long by 6 ft. 10

ins. wide) and helped to run it. And so entire families came

to exist in the inadequate confines of a canal boat cabin, with

limited toilet and washing facilities, and with a nomadic lifestyle

cut off from the developing influences of the outside world,

particularly those of health and education:

“Some of the canal cabins are models of neatness and a man and

two youths might pass a few nights in such very comfortably.

Others are the most filthy holes imaginable, what with bugs and

other vermin creeping up the sides, stinking mud finding its way

through the leaky joints at the end to the bottom of the cabin and

being heated by a hot stove, stenches arise therefrom to make a dog

sick. In these cabins fathers, mothers, sisters and brothers

sleep in the same bed at the same time. In these places girls

of 17 give birth to children, fathers of which are members of their

own family.”

Our Canal Population,

George Smith (1875)

Bearing in mind the nature of some of the cargoes carried ― such as

manure, night soil [14] and council rubbish ―

vermin infestation was hardly surprising. Such conditions

alone led to disease, added to which boat people washed in, cooked

with and often drank canal water polluted with excrement dumped from

the boats and other sources. Smith, motivated by his strong

Methodist ideals, wanted children ― boys under 13, girls under 18 —

removed from the over-crowded and sometimes insanitary canal boat

cabins. He also wanted each canal boat to be registered for

the number, age and gender of the occupants it could accommodate

and for children to reach a certain standard of education before

being allowed to enter the canal carrying trade. His

persistent campaigning eventually bore fruit, and on 1st January

1878, the first Canal Boats Act [15] became law.

The Act required every canal boat that was to be used as a dwelling

to be registered “with some registration authority having a

district abutting on the canal on which the boat is accustomed or

intended to ply”. The registration certificates issued

under the Act contained various details about the boat, how it

should be marked as being registered, and “the number, age

and sex of the persons allowed to dwell in the boat”. In

determining the latter, account was taken of “the cubic space,

ventilation, provision for the separation of the sexes, general

healthiness, and convenience of accommodation of the boat”.

And so the Act attempted to address moral issues as well as those

concerning hygiene and the spread of infectious disease:

“During the past four weeks two registered canal boats have been

conveying smallpox to different parts of the country. In one

case a boatwoman with two children were left at Leighton suffering

from this terrible disease, and the boatman continued his course to

this district, when another child, suffering from the same malady,

was ‘put off’ and sent to Leicester. A few days later the

doctor pronounced another child that was in the cabin ill of the

same complaint, but the boat moved on. In the case of the

other boat, two children were left at Berkhamsted ill of small-pox,

and the boat, with two children in the cabin, moved forward to

Staffordshire. If the time should ever come when the Canal

Boat Act Amendment Bill I am humbly promoting, and which has been

before Parliament during the last two sessions, becomes law, such

cases as the above will be impossible; and the 60,000 canals and

gipsy children of school age growing up in black midnight ignorance

will have been put upon a step that leads from darkness to light,

and from hell to heaven, with but little cost or inconvenience to

either boatmen or boat owners. Shall it be so?”

George Smith, of Coalville, 28th March 1883

The Act also attempted to ensure some degree of education by

bringing children under the provisions of the various Education Acts

then in force, but as canal families were a nomadic population its

educational aspirations could not be implemented effectively in

practice. The Act was flawed in other ways. It contained

nothing to regulate the use of child labour and its implementation

was left to local authorities who did so with varying degrees of

enthusiasm.

Teatime

In 1884, an amendment Act passed into law that attempted to address

these problems. It provided for canal boats to be inspected by

sanitary authorities under a centrally appointed Chief Canal Boat

Inspector, allowed for penalties to be imposed for violations of the

Act, and gave regulation-making powers to the Education Department.

The Local Government Board accepted responsibility for the Canal

Boat Acts, but with extreme reluctance.

While failing to satisfy Smith’s objectives, the Acts went some way

to reducing overcrowding and setting a minimum standard of

accommodation and sanitation that was enforced by fairly regular

inspection. It undoubtedly resulted in some improvement in the

social condition of canal boat families, although at the expense of

breaking up larger family groups, for to bring the number of

occupants on a boat within registration limits, ‘surplus’ children

had to be farmed out to other canal boat families who had spare

living space.

Three establishments were set up on the Grand Junction Canal where

some education was provided. The first was set up at Brentford

in 1904 by a religious organisation, the London City Mission:

“For many water families, the Boatmen‘s Institute on the Grand

Union Canal‘s west London terminus at Brentford was a beacon, where

the children could be left for weeks at a time to get the rudiments

of an education as the parents took loads to Birmingham and back.

The place even had lying-in rooms where women could give birth in

relative dignity. For one old boatman, it was ‘the happiest, blessedest place in Brentford’.”

The Independent, 12th

May, 2004

The Mission also administered a further school

at Paddington . . . .

“A scheme for the extension of the existing facilities for the

education of canal-boat children, who come to London by barge from

many parts of the country, has this week been finally approved by

the committee responsible for the conduct of the Boatman‘s

Institute. For the past nine years a school has been carried

on at the Institute in South Wharf-road, Paddington, but the

building is now to be demolished to make room for a new medical

school in connection with St. Mary‘s Hospital. Suitable and

more commodious premises have been secured for the purpose in Irongate Wharf-road. There are 90 children at present on the

school‘s roll, but when the new accommodation is available it is

expected that that number will be quadrupled.

The problem of the education of barge children is of long standing.

The conditions of barge life have made the children the despair of

the attendance officer. The progress made by children

attending the present school has, however, been remarkable.

When it was first opened it was rare to find a child, or even a

grown-up person, the canal community who could read or write.

Now, especially among the older children, illiteracy is rarely

found.”

The Times, 20th

December, 1929

To these were added the barge-based school, the

Elsdale, at Bull’s

Bridge.

But isolation ― perhaps alleviated to some extent by the later arrival of

wireless ― and a high incidence of illiteracy among canal families

only disappeared with the end of canal carrying.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX.

Evidence given before a committee of the House of

Lords

sitting on the first London and Birmingham Railway Bill,

June 1832.

Appendix to Railway Practice, by S. C. Brees (1839)

MR. WILLIAM

PARTRIDGE,

Canal Carrier of Thirty four Years Experience.

“I have been engaged 20 years in trading between Birmingham

and London, (and from Birmingham, Worcester, Shrewsbury, and

Bristol).

There are three Routes by Canal to London, one by Worcester and

Birmingham, one by Stratford and Worcester, and another round by

Coventry. The Fly Boats go the shortest route, and are three days

and nights on the journey; the Slow Boats are six or seven days, and

they seldom travel at night.

The shortest route to London is taking the whole line of the

Worcester and Birmingham Canal, which goes into the Warwick and

Knapton, and only seven miles on the Oxford; the Heavy Boats

generally go by the Fazeley, which is the longest route, as the

Birmingham Canal Company allow them to pass on to Fazeley, to a

certain place where the Oxford Canal charges the same for going 40

miles as the others do for going seven, which makes it cheap.

The number of Fly Boats which start from Birmingham every week is

25, and the average tonnage of each boat is about 15 tons up and 8

tons down; they sometimes carry from 18 to 19 tons. The number of

Slow Boats that start from Birmingham weekly is about 30, an the

average number of tons conveyed by them is 23 up and 5 down.

The Cargoes conveyed to London, consist of all the Manufactured

Goods of the neighbourhood, as Nails, Vices, Anvils, Chains,

Agricultural Implements. These are charged 40s. a Ton which is a

lower Rate of Tonnage and Freight than the other part of the Cargo,

which consists of Locks, Coach Pins, Screws, Sadlery, Ironmonger's

and Drysaltery Goods, Copper Furniture and Nails, Wire, and Wire

manufactured Goods, Iron and Paper Trays, Fenders, Fire Irons, Guns,

Swords, and Army Stores, Glass Lamps, Bronze Goods, Steel and other

Ornaments, Ivory and Bone Toys, Plated Goods, Carpets, &c. The

Freight of these light Goods is 55s. The heavy goods are put at the

bottom of the Boat, and the light goods on the top.