|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH

WATER.

PART V. ―

POSTSCRIPT

THE GRAND UNION CANAL COMPANY

“I cannot repeat too often that transport today is an indivisible

commodity and that there is little hope for the survival of canals

unless the canal industry provides not merely a transport track, but

a transport service that is equal to the service provided by the

other forms of transport. Such a service can be provided by

the canal industry, but only through the constant exercise of

commercial initiative and enterprise.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, May 1945

INTRODUCTION

On 1st January 1929 the Grand Junction Canal Company ceased to

exist.

In several ways the 18 years following the formation of

the Grand

Union Canal Company are the most interesting in the waterway’s history,

for until then it had led a fairly mundane existence. Under

new ownership

the waterway entered a period of significant change and although much of

it

failed to achieve its aims, those aspects that did succeed leave a

tantalising picture of what might have been had not the cold hands

of the State stifled the business.

|

|

|

R. F. de Salis. |

Apart from

its unsuccessful venture into canal carrying, the Grand

Junction Canal Company had throughout its life operated along the

lines of a turnpike trust, deriving its revenue mainly from the

passive collection of tolls and from rental income (which by end of

its life formed a substantial part of its revenue).

But this moribund style of management was to change abruptly.

On 1st January 1929 the amalgamation of the Grand Junction Canal Company, the Regent’s

Canal and Dock Company and the Warwick canals to

form the Grand Union Canal Company took effect. There followed a radical

change in management outlook, first as the new board extended and

modernised its main line in a forlorn attempt to resuscitate

long-distance canal carrying; then, following a radical management

shake-up, as their successors set about building a sustainable business by

diversifying into related areas of transport activity. But

WWII. intervened before these strategies could take real effect and

the Company was again to experience ― as de Salis had described the

Grand Junction Canal Company’s experience during WWI. ― being

“very unfairly treated” under the regime of wartime government

control.

The War years did see one important, albeit short-lived,

development. The Grand Union Canal Act 1943 repealed many of

the clauses in the archaic canal Acts inherited by the new Company

from its constituents. It also extended the

Company’s borrowing powers, enabling it to diversify its business ―

and here it took full advantage ― and, overall, gave to it the

attributes of a modern business enterprise. In the immediate

post-war years the benefits of diversification were beginning to

show when, on 1st January 1948 the Company’s assets were acquired by

the State together with those of many other transport

undertakings to form the British Transport Commission.

――――♦――――

THE NEW COMPANY

|

|

|

Wilfrid H. Curtis.

First Chairman of the Grand Union Canal Company. |

On 1st January 1929, two Acts of Parliament [1]

took effect under which the Regent’s Canal and Dock Company

acquired, via a merger, the canal assets of the Grand Junction Canal

Company and at the same time purchased the three Warwick canals,

which form the shortest route from Braunston to Birmingham.

The company so created, the Grand Union Canal Company, [2]

took its name from the former Leicester Line canal, which has since

been known as the ‘old’ Grand Union Canal.

The negotiations that led to this amalgamation came to public

attention in May 1927, but they had commenced some years previously.

Recognising that the two companies had much commonality of purpose,

de Salis approached W. H. Curtis, a Grand Junction Canal Company

director and Chairman of the Regent’s Canal and Dock Company, with a

proposal that they examine the possibility of a merger, a tactic

that would avoid one company having to raise the large cash sum

necessary to buy the other. [3] Informal

discussions then progressed, the companies’ auditors and solicitors

became involved and negotiations eventually reached fruition early

in 1928, soon to be followed by extraordinary general meetings

at which the terms of the amalgamation were approved by the

respective shareholders. Because the companies had been

created under the archaic ‘joint stock company’ system, each having

been formed by a private Act of Parliament, further Acts were

necessary to sanction both the merger and the purchase of the

similarly constituted Warwick canals. The new company took the

form of a ‘limited liability company’, [4] its

board comprising six directors ― three each from the Grand Junction

Canal Company and the Regent’s Canal and Dock Company ― under the

chairmanship of W. H. Curtis. [5]

The terms of the grouping were, that:

-

the holder of each £100 share in the Grand Junction Canal

Company received Grand Union Canal Company stock to the nominal

value of £67 6s ― a later capital adjustment (£40,906 2s 6d)

increased this to £70 18s 6d; [6]

-

the three Warwick canals were bought outright by the Regent’s

Canal and Dock Company, which paid £62,258 15s. 0d. for the

Warwick & Birmingham Canal and £8,641 for the Warwick & Napton

Canal [7] (the Birmingham & Warwick Junction

Canal being owned jointly by the other two);

-

the Grand Union Canal Company became responsible for the upkeep

of the section of the Oxford Canal between Braunston Junction

and Napton Junction;

-

a new limited liability company, ‘The Grand Junction Company’, [8]

was formed to acquire that part of the Grand Junction Canal

Company’s property portfolio at Paddington, which was not

included in the merger, together with certain Grand Junction

Canal Company pension obligations, and to carry on the business

of an estates and financial company. The Grand Junction

Canal Company’s existing 4% debenture stock (£150,000) and 6%

preference shares (£93,700) were to be serviced by the Grand

Junction Company, which received rental income from its property

portfolio and the interest on 5½% Grand Union Canal Company

debenture stock to the value of £285,709.

To

some extent the formation of the Grand Union Canal Company

implemented a recommendation of the 1906 Royal Commission, that

canal company mergers were desirable to achieve control over longer

routes (which railway mergers had achieved many years earlier), both

in terms of setting ‘through tolls’ and standardising waterway

dimensions; failure to achieve each had greatly hindered the

development of inland waterway transport in the UK. The

formation of the new Company gave its Board control over the entire

route from London (Brentford and Regent’s Dock) to Birmingham. [9]

In 1931, the Company also obtained control over the entire route

from London to the River Trent with the purchase of the Leicester

Navigation (Leicester to Loughborough) and the Loughborough

Navigation (Loughborough to the River Trent); the purchase of

the Erewash Canal further extended Company’s domain from the Trent to Langley Mill on the

border of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire. At an extraordinary

general meeting convened to seek shareholder approval for this

scheme, Curtis described his vision for the extended waterway:

“. . . . the linking up of these undertakings with the Grand

Union would provide a fine barge canal from London to the Trent, and

Nottinghamshire, when certain larger locks had been built at Foxton

and Watford. As this last improvement was a very costly one,

amounting to £150,000, they [the Company] had made an

application to the Government under the Development (Loans

Guarantees and Grants) Act, 1929, to carry them over while the work

was being executed and until the traffic began to move.”

The Times, 29th May,

1931

Acquisition of the north Leicestershire canals required an enabling Act [10]

which, when it came into force on 1st January 1932, added a further

40 miles of canal to the 240 miles existing. In announcing the

takeover, The Times report went on to say that dredging would

commence “without delay”, which suggests that the

newly-acquired waterway was in poor shape.

The Board then returned to a scheme last tried in the 1890s, of widening the locks at Foxton and

Watford to take larger craft, their view being that this would

increase the canal trade between the

Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire coalfields, the Leicestershire

granite quarries (chippings for road construction) and markets in

the Home Counties. It would also provide better access to the

ironworks of the Erewash Valley and to the electrical engineering

works around Loughborough. How the restriction on the passage

of wide craft in the confines of the Blisworth Tunnel was to be

dealt with appears to have been glossed over. But the Board had been unduly optimistic

in extending their waterway before the Government had agreed to

provide the financial assistance necessary to fund the cost of

rebuilding the Watford and Foxton locks, which they declined to do. Without government help,

the scheme was unaffordable, for by then the cost of

modernising the London to Birmingham route had left the Company’s

finances over-stretched. Thus, Curtis’s vision of a barge

canal from London to the Trent evaporated and the narrow staircase

locks at Watford and Foxton continued to restrict the through route

to narrow boats and impose a bottleneck on the passage of trade.

|

56 YEARS IN THE SAME OFFICE!

Undated clip from the Evening News.

When on Tuesday two of London’s best-known canal

companies, the Grand Junction Canal and the Regent’s

Canal, cease to exist as separate bodies and become the

Grand Union Canal, it may be the beginning of a new era

in English canal history, but it will be the end of a

very interesting personal record.

Mr. J. W. Bliss, whose office as general manager to the

Grand Junction Canal will come to an end, has been for

51½ years the same room at the foot of Surry-street,

Strand. Not many men in London could beat that

record. “During the whole of that time,” said Mr. Bliss

to the Evening News today, “I have only been absent from

work four days owing to an attack of lumbago.

“I came from Northamptonshire when I was 16. I had

had a fine open-air life, riding almost as soon as I

could walk, and hunting with the Pytchley as often as I

could. Perhaps it was partly to this that I owe my

good health. I started off as a junior clerk with a

salary of £50 a year, and worked up, step-by-step, till

I became clerk to the company in 1905 and general

manager in 1916.

“My life has been a pleasure all the way through, and it

will be a bit of a wrench to give up the old work, the

old routine, and the old office. One thing I am

most pleased with is that we have never had any labour

troubles among our staff of 300 or so. Even during

the general strike our relations continued friendly, and

everyone remained at work.

“It has been part of my duty to make each year a tour of

our whole system, a hundred miles or so. I made

the tour latterly in a motor boat, and I suppose I have

done it for the last thirty years. The result is

that I have got intimately the whole system and many of

the men who work on it. When the new company takes

over I shall be an advisory director, and well as being

manager of the Grand Junction Canal estates at

Paddington, and it will be a great pleasure if I am

invited to make the annual tour of the system again.”

Mr. Bliss believes that the outlook for the canals of

the country has never since the introduction of railways

been so bright as it is now. Road transport, he

says, which in some places is a competitor, is in others

an ally. “The outlook is brighter,” he declared,

“because, with common management over a group of canals

through journeys are made more easy and it is possible

to have a higher standard of maintenance. Time is the

essence of the matter in transport competition and the

common management of canals between London and

Birmingham will probably lead to a reduction in the time

spent on the journey. The replacing of the horse by the

motor has also been a big factor in the improved

outlook.”

Mr. Bliss has a high opinion of the people who work on

the canal boats and barges. “They are good-hearted

people,” he said. “I have known a case where, when

the parents on one boat died their children were adopted

by the man and wife on another boat.” |

――――♦――――

MODERNISING THE MAINLINE

The Grand Union Canal Company got off to an unfavourable start.

The winter of 1928-29 was severe, resulting in six inches of ice in

places; this was followed by a period of drought. Other than

reducing that year’s dividend and providing the Board with

a recognition that better ice-clearing methods were needed, other

items for them to address included dredging and the need for more protection

against bank erosion caused by turbulence from the growing number of

motor boats then entering use. It was therefore proposed to

invest £50,000 to £60,000 on further concrete walling and piling,

which would achieve the additional benefit of increasing the bottom

width of the waterway, thereby reducing drag and speeding up

traffic. But this modest engineering programme was soon to be

overshadowed by another, which would have far-reaching consequences

for the Company’s fortunes.

In 1929, Herbert Morrison, then Minister of Transport, announced

that the Labour government favoured canal development as a means of

helping industry, and that the ‘Development (Loan, Guarantees, and

Grants) Bill’ then passing through Parliament might provide

financial assistance to help develop waterways serving important

industrial areas.

Long-distance traffic on the Canal had been declining for many

years, a state of affairs that in 1920 had caused de Salis to state

that “we shall hope to carry out desirable improvements on the

paying portion of our canal, but on the non-paying portion we shall

merely carry out our obligations. . .” the paying portion of the

canal being that to the south of Berkhamsted. Despite this

pronouncement, the new Board

must have seen sufficient potential in the face of existing rail and

growing road competition to revive their long-distance traffic sufficiently to justify the heavy

investment needed to upgrade the entire London to Birmingham route,

and they set about planning a programme of improvements the likes of

which had not been seen since the waterway was built. Their

aim was to transform the Company into a transport business that, for

deadweight cargoes at least, could compete with road and rail

transport on equal terms. They believed that this could be

achieved by upgrading the waterway to handle bigger and faster craft

and by offering modern cargo-handling, storage and distribution

facilities at its principal wharfs. When complete, it was

envisaged that the London to Birmingham service would be operated by

pairs of wide boats (12ft 6ins beam) loaded to 137 tons compared

with 55 tons for a pair of narrow boats, and that they would complete the

journey in 48 hours compared with the 60 hours existing.

Furthermore, the use of craft of sufficient size to navigate the

Thames would avoid the cost and delay involved in transhipping cargo

at Brentford between Thames barges and lighters, and narrow boats.

In response to the Government’s grants scheme, the Company submitted

a three-year development programme designed to transform the

existing London to Birmingham waterway into a barge canal

throughout. It included bridge widening; concrete walling,

piling and dredging; and widening the narrow locks on the former

Warwick canals to accommodate craft of 12ft 6ins (and

ultimately14ft) beam. The programme’s estimated cost was

£881,000, but the answers to some questions about it are not evident.

Based on past experience of using wide boats north of Berkhamsted, [11]

the intended service improvement would have required the section of the

main line from Berkhamsted to Braunston to be dredged and widened;

there is also the question of the passage of wide boats in the confines of

the tunnels; and the

Board’s ultimate aim of using river barges (14ft beam) on the

Birmingham route would have required further extensive bridge widening.

In November 1930, a notice appeared in the London Gazette

informing the public of the Company’s intention to introduce a Bill

into Parliament seeking powers to undertake the proposed engineering

work. This was to include, inter alia, obtaining land

by compulsory purchase; building new locks and flights of locks

between Napton and Birmingham; fixing tolls; obtaining a running

agreement over the Braunston to Napton Junction section of the

Oxford Canal; and raising additional capital and loans to finance

the scheme.

The public announcement was followed by an extraordinary general

meeting at which Curtis described the aim of the plan. He

informed the meeting that, despite significant industrial growth,

traffic between London and Birmingham had remained practically

static at around 100,000 tons p.a. during the previous 20 years.

The situation required “enterprise” and that by opening up

the route to larger and faster craft the Company would acquire more

business. But Curtis’s belief departs from another important point

stated by de Salis a decade earlier. When addressing the

decline in the Grand Junction Canal Company’s long distance

business, de Salis had explained to his shareholders that an

increased share of the London to Birmingham trade could only be

gained at the expense of the railways. As he understood the

position:

“We divide our traffic roughly into two classes: — Through, or

traffic between London, Braunston (for Birmingham), Leicester and

Northampton; and Local (all other traffic). Generally, the

through traffic is in competition with rail; the local traffic is

not . . . . . Three men are needed to move 50 tons, say, from London

to Birmingham on canal, and the same number can move 500 tons by

rail. This is a factor which has come to stay, and I do not

think we can look for anything but a dwindling long-distance

traffic.”

Chairman’s address to the GJCC General Assembly,

December 1920

The modernisation plan obtained Parliamentary approval in the Grand

Union Canal Act 1931, which authorised the Company to finance the

work by the issue of redeemable (in 1953) debenture stock up to the

value of £500,000. The stock, designated the ‘Grand Union

Canal Development Loan No. 1’, carried a 4% coupon and by way of

government assistance the Company was awarded a grant of the

interest on £500,000 for 10 years at 5% p.a., and 2½% p.a. for a

further five years. A further £400,000 of 6% preference stock

was issued at the same time.

At the Company’s general meeting in March 1932, Curtis was able to

report that work on the scheme was making substantial progress.

Extensive dredging had been carried out with the aim of deepening to

5ft 6ins the section of canal from Brentford and throughout the Long

Level to permit the passage of 100 ton capacity barges, much

concrete walling and piling had been carried out, and a tender had

been accepted for widening the Warwick canals’ locks to accommodate

wide boats:

“When the works contemplated by the new capital schemes are

finished, the Company will be in possession of a waterway linking

the chief midland towns and coalfields to the metropolis, providing

a means of transport at a cost which will be much less than by any

other method. When one realizes the importance of low

transport cost to the export trades it is not surprising to learn

that the facilities that the Company will have to offer to the

Midland manufacturers are likely to be taken advantage of to a very

large extent. . . . . With our costs so low new traffic is bound to

come to us and when trade gets over its troubles [i.e.

the Great Depression] we can confidently expect increased

business.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1932

|

|

|

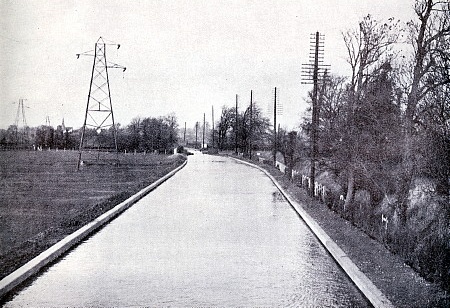

A section of the

Canal before modernisation . . . . |

By the following year, modernisation of the Warwick canals was

proceeding. A £350,000 contract employing nearly 1,000 men ―

about three quarters from the local dole queues ― had been placed

with L. J. Speight Ltd, a firm of civil engineering contractors

working under the supervision of the eminent civil engineer, Sir

Robert Elliott-Cooper. Construction work was planned carefully

to permit it to proceed without the need to suspend canal traffic:

“. . . . for miles the canal banks have been transformed from

rough jagged boundaries to concrete walls presenting all the

symmetry of an up-to-date swimming bath. . . . many parts of the

canal are being improved by men directly employed by the Company;

indeed, activity is general almost throughout the length of the

waterway.”

The Times, 20th June,

1933

|

|

|

. . . . and

afterwards. |

Work on the Warwick canals included converting the existing 52

narrow locks into weirs, replacing them with 51 wide locks (on the

Knowle flight, six locks were replaced by five) of a modern design:

“The reconstruction gave the opportunity for several new

features. Adjustment of the water level in the lock chamber

was hastened by the construction of large sluices of a spiral type

with bevel gearing specially designed; and the sluice culverts were

carried along the side walls and provided with three lateral

openings through which the water finds an exit. These large

sluiceways ensure the rapid filling or emptying of the lock, and the

average time for craft passing through does not exceed four minutes

for the complete operation.”

Transport and the Public,

J. A. Dunnage (1935)

|

|

|

New locks under

construction at Knowle, Warwickshire in 1932.

The old narrow locks are on the left of the picture. |

Extensive dredging deepened the Braunston to Birmingham section to

5ft 6ins, while walling increased the waterway’s bottom width to

27ft, a profile that had been derived from experiments undertaken by

the Company, from which it was learned that:

“. . . . for a 14 feet horse-drawn barge, where the ratio of

canal area to boat immersed area was increased by passing from an

undredged to a dredged section by 56.6 per cent, the speed was

increased by 66.8 per cent; for a 7 foot motor-driven boat passing

similarly into a dredged section where the area ratio was increased

by 77.7 per cent the speed was increased by 59 per cent or from 2.73

to 4.62 m.p.h. The results of these tests was that the

standard to be aimed at was, for 14 feet beam craft, a minimum

bottom width of canal of 32 feet by 5 feet 6 inches minimum depth,

and for 12 feet 6 inches craft a minimum bottom width of canal of 27

feet.”

Transport and the Public,

J. A. Dunnage (1935)

By October 1934, most of this re-engineering had been completed and

the Duke of Kent was invited to open the new locks between

Napton and Birmingham. He boarded the new wide boat

Progress at Hatton Station canal bridge from where he travelled

to perform the opening ceremony.

Progress was to be the precursor of a fleet of larger craft

that were to form an important element of the Board’s long distance

carrying strategy. Her specification was a significant

departure from the wide boats then in operation on the Canal:

“The motor vessel ‘Progress’ is a new type of canal wide boat and

was built at Messrs. Bushell Bros. Dock Yard, at Tring. It

will be the first motor canal boat of its size to go and load in the

Thames ex-ship and carry goods to Birmingham, thus saving

transhipment. Up to the present barges large enough to load

ex-ship have only been able to travel as far as Berkhamsted and are

horse drawn.

The motor vessel ‘Progress’ has an overall length of 75 feet, a beam

of 12 feet 6 inches, and a depth of 5 feet, and will be capable of

carrying 68 tons. It is fitted with a British-Junkers

30-B.H.P. three-cylinder unit engine and runs at 1,200 r.p.m.

It carries seven river lamps, a bell, fog horn and has wheel

steering and living accommodation.”

Unidentified press cutting in the collection of Miss Catherine

Bushell

Progress moored on the Wendover

Arm following construction and fitting out for the Royal ceremony at

Bushell Brothers’ boatyard.

Progress, conveying the Duke of

Kent at the opening ceremony at Hatton Locks, October 1934.

But wide boat carrying was not to be ― by 1937 the development money had

run out, leaving sections of the main line south of Braunston unable

to accommodate them. Thus Progress became the sole

example of a class of canal craft that might have been. The

Board’s wide boat strategy was laid quietly to one side and

the Company’s long distance carrying fleet continued to comprise

narrow boats, a position that continued until the trade finally petered out

with the closure of Boxmoor Wharf in

1981:

“The narrow locks on the Warwick section of the main line were

rebuilt before the last war and a pair of narrow boats can now be

locked through to Birmingham in one operation. The Grand Union

Canal Company spent about £1 million on this scheme and on dredging

and bank protection, but failed to secure sufficient money to

complete their programme within the time allowed by the Grants

Committee. The London-Birmingham route beyond Berkhamsted

continued to be operated by narrow boats. It is inadvisable to

use narrow boats on the Thames, and goods destined for destinations

beyond Berkhamsted are discharged into lighters and transhipped at

Regent’s Canal Dock or Brentford.”

Canals and Inland Waterways:

Report of the Board of Survey (Rusholme Report), BTC, 1955

|

|

|

The GUCCC butty

Tiverton (No. 376) at Tysley Wharf.

The cranes had just been supplied by Stother & Pitt. |

Although the Company continued to invest in improvements to its

warehousing facilities at Brentford and Birmingham (Sampson Road and

Tyseley), by 1937 it had become apparent that modernisation was

failing to produce the desired returns, nor did it seem likely to.

In explaining to shareholders why their Ordinary dividend had been

passed over for the third successive year, Curtis had this to say:

“What, then, are the reasons for passing an Ordinary dividend for

three years in succession? The main reason is that the revenue

from tonnage carried has not left sufficient margin after paying the

prior charges incurred in performing our part of the arrangement

entered into with the Treasury, which was a condition for receiving

from them the grant of interest. These prior charges amount in

all to nearly £30,000. This slow expansion of the tonnage

revenue has been largely due to the fierce competition by rail and

road.

The railways entered into an agreement with the Canal Association,

of which we are ourselves members, which purported to benefit both

parties. So far as we are concerned it resulted in the loss of

a very large tonnage in one particular trade where the railways were

fighting coastwise shipping. The cut rate might have stopped

coastwise shipping, but it certainly killed our trade. We have

protested that this sort of thing was not provided for, and we are

letting the Canal Association know that we are of this opinion.

The railway attitude is that they will not give a canal such as ours

a place in the sun.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, April 1937

|

|

|

Col. E. J. Woolley

MC |

Thus de Salis’s policy of concentrating on short-haul freight

carried to canal-side locations ― thereby avoiding railway

competition (road transport having become an additional competitor)

― appears to have been vindicated. Indeed, when the British

Transport Commission reviewed the operation of their canals in 1954,

they reached the same conclusion, that only the section of the Canal

south of Berkhamsted was worthy of further investment, and that the

remainder was “to be retained”. [12]

|

.JPG) |

|

.JPG) |

|

The GUCC warehouse

at Sampson Road c.1938. |

Perhaps failure to meet its strategic objectives led to the Board

being restructured, with two directors resigning to make way for

“younger men”. Three new directors ― John Miller, E. J.

Woolley and J. M. Whittington ― were appointed, and formed a

committee tasked with making economies and reorganising the Company.

At the 1937 General Meeting, Curtis was reappointed to the Board for

a further term, but shortly afterwards a brief press statement

announced his resignation, E. J. Woolley being appointed to succeed

him. At the following year’s General Meeting there is no

mention of Curtis receiving a vote of thanks for his years of

service to the Company, and to the Regent’s Canal and Dock Company

before it. Speaking at the Company’s final General Meeting

over a decade later, the presiding Chairman, John Miller, on looking

back as his directorship, referred to a reconstruction of the Board

towards the end of 1936 “when the Company was undoubtedly in a

very precarious condition”. It is of course a matter of

conjecture, but circumstances suggest that Curtis’s resignation was

encouraged.

Modernisation continued under the chairmanship of E. J. Woolley.

September 1938 saw the opening of the Company’s new warehousing

facility at Sampson Road, Birmingham. Built at a cost of over

£34,000, it offered 30,000 square feet of floor space. Boats

could enter its internal wharfs to be worked by the latest

electrically operated gantry cranes capable of moving goods to any

part of the building. The press described the depot as being

“in every sense an inland dock”. In addition,

warehousing at Brentford was extended, that at Leicester and

Northampton improved, new cranes were purchased for use at Tysley

and at the Regent’s Dock, and motor vehicles were acquired to

improve the collection and delivery of goods in the Birmingham area:

“In keeping with the Company’s policy of bringing the whole of

their system into line with modern conditions, and making it capable

virtually of handling an almost unlimited quantity of traffic, was

their decision to provide new terminal facilities, or improve those

already in existence at every point where present or prospective

trade justified such a step. Thus, they have spent a large

amount of money in modernising the Regent’s Canal Dock and in

providing large warehouses in Birmingham, Brentford and other places

which have been important centres of canal activity . . . . It is

now scarcely necessary to recall that shortly after carrying the

ambitious amalgamation scheme into effect, the Company, in part with

the aid of the Government, and for the rest out of their own

resources, spent over £1,000,000 in improving the waterway along its

main route between London and Birmingham.”

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material c.

1938

By 1942, the Board was already beginning to take a view on the

post-war position of the Company. The indications at that time

suggest that they recognised that the future lay in providing a

broader-based transport service ― warehousing, shipping and road

haulage ― to replace their core activity of long-distance canal

carrying, which would eventually and inevitably disappear.

――――♦――――

COMMERCIAL EXPANSION

Besides extending the network to gain end-to-end control of their

main routes, the Board also acquired or created a number of

subsidiary companies, their aim being to transform the Company into

an integrated transport business that could compete favourably with

its competitors. The Board’s business strategy was summed up

by John Miller (by then Company Chairman) towards the end of the

WWII.:

“Stockholders will recall that payment of the dividend on the

Preference stock was last made in respect of the year 1936. In

the course of that year and of the next year considerable changes

were made in the Board, and the whole organisation of the Company

was drastically altered. It is clear that the Company was not

earning its Preference dividend and that the serious decline in

revenue since the amalgamation in 1929 would continue at a

progressive pace, unless drastic steps were taken to arrest the

decline and open up new fields of revenue, by broadening the basis

of the Company’s business, expanding its activities, and

transforming it from a mere passive toll-taking owner of a canal

track and dock into a comprehensive transport organisation.

It is to this end that we have laboured since 1936. That is

why we acquired our own shipping company and our own stevedoring

company at the Regent’s Canal Dock, that is why we have acquired a

road haulage subsidiary and formed our own road transport

department, why we organised a modern warehousing department, why we

acquired new warehouses, improved existing warehouses, and installed

at all our terminals and depots and at the Dock new and improved

handling installations and equipment. Quick results were not

to be expected, but before the outbreak of war there were signs that

we had already turned the corner.

The effect of the war was to interrupt the commercial progress of

the Company. The continental and most of the other overseas

traffic which we had been building up was soon lost, and the

Government control of railways tended to divert traffic from the

canal. Moreover there was a continuous rise in wages and other

costs effecting maintenance and operation of the canal which has

only recently reached what I hope is its peak.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, December

1944

Broadening the business base began modestly. In 1930, the

Company entered into canal transport with the acquisition of a small

carrying fleet, Associated Canal Carriers Ltd. [13]

This was followed by further acquisitions; in 1934, of the Erewash

Canal Carrying Company, another small company that operated mainly

along the Loughborough and Erewash lines, and in 1936, of Thomas

Clayton (Paddington) Ltd, a firm that specialised in rubbish

disposal and which was to become a reliable earner for the Company.

For many years Claytons had contracted with the Borough of

Paddington to dispose of some 40,000 tons p.a. of household rubbish,

and in 1939 they obtained a similar contract from the Borough of St.

Marylebone.

In parallel with their entry into canal carrying, the Board made a

determined effort to develop the leisure side of their business.

The “picturesque reservoirs” at Ruislip and Aldenham offered

potential for bathing, boating, and fishing and, overall, a source

of income that would help compensate for the increased cost (which

could be considerable) of pumping canal reservoirs during long dry

summers. In 1933, the Company commenced the development of a

lido at Ruislip Reservoir, spending some £12,000 on what Curtis

described as “a lido quite on the lines of summer seaside

resorts” from which he expected “a good return”.

The Lido, which was opened by the Earl of Howe in 1936, centred on

an art-deco style building fronted by a swimming area flanked on

either side by piers in a horseshoe shape. The main building

contained a cafeteria while those on either side housed the

turnstile and ticket area, and changing rooms. The Lido was

successful in its heyday, offering swimming, boating, a children’s

playground, a beach and later a miniature railway. [14]

During 1937, the Company expanded its freight handling capabilities

by acquiring interests in a stevedoring and wharfage company ― which

became the Grand Union (Stevedoring and Wharfage) Company Limited ―

and in a short-sea shipping business. This firm,

Grand Union (Shipping) Ltd., operated the Regent’s Line, which using

a small coastal steamer, the Marsworth, opened a twice-weekly

service between the Regent’s Canal Dock and Antwerp. The

following year the Marsworth was joined by the Blisworth

and the service extended to Rotterdam. At the other end of the

line the Company acquired an interest in a Belgian shipping agency

registered in Antwerp, Grand Union Belge de Transports Societe

Anonyme, to handle its Continental business. This firm

owned its own barge fleet and was able to provide quotations for and

handle through traffic from UK towns served by the Canal to

the principal European cities:

“We are thus able to carry goods from Birmingham to Basle and

other Continental towns in our own craft by the all-water route.

This achievement, I believe, is unique in the history of British

transport . . . . You may wonder where the money has come from to

pay for the new companies and other heavy expenditure we have had to

incur. We have, however, been able to sell a considerable

amount of land which was of no use for canal purposes and produced

no revenue. You will, I am sure, agree that we have pursued

the right policy in converting it into something which will produce

revenue. As opportunity offers we intend to sell more such

land.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1938

In addition to running its own shipping operation, Grand Union

(Shipping) also acquired the UK agencies for several Continental

transport businesses including the Dutch ‘Oranje Line’. Using

four ships, this company opened up a fortnightly service between the

Regent’s Canal Dock, Canada and the USA during the open season ―

which extended from the end of March to about the middle of October

― and landed fruit from Spain and Palestine during the winter

months.

By March 1939, the Company’s progress into shipping and the

development of their terminal facilities appears to have been

sufficiently encouraging to lead the Chairman to report to that

year’s General Meeting that during the year 1,690 ships had passed

through the Dock and that shipping “is producing business both

for the Stevedoring and Wharfage Company, the canal, our Birmingham

warehouse, and the Dock”. Meanwhile, the Company was

publicising its Regent’s Dock facilities:

“There is a regular service of steamers between the Dock and

Bergen, Stavanger, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Danzig, Hamburg, Bremen,

Delfzijl, Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp, Ghent, etc. During

the season, considerable quantities of timber are discharged

overside from steamers into canal craft for delivery to the numerous

wharves situated at various points on the canal. [15]

Cargoes of all descriptions can be conveniently discharged overside

into canal boats for conveyance to the many towns served by the

Grand Union route to the Midlands.

There is a 250ft coal jetty in the Dock equipped with two powerful

grabs, each capable of lifting six tons and these enable steamers

coming from the coalfields of the N.E. coast to discharge their

cargoes within about ten hours of arrival. Unloading can be

carried out either by day or night, and it is quite usual for a ship

to enter the Dock on one tide, discharge its cargo, and leave for

the return journey on the next tide. Large quantities of coal are

discharged at this jetty and then conveyed to the gas and

electricity stations situated on the canal side in the London area.”

Grand Union Canal Company publicity material ca. 1938

However, established shipping interests were unwilling to accept

further competition and commenced an action against the Company for

ultra vires [16] claiming that it had no

lawful authority to run a shipping business. The action

lingered on until powers obtained under the Grand Union Canal Act

1943 ― the Chamber of Shipping contesting the Bill’s passage through

both houses ― enabled the Company to extend its business lawfully

into related areas. The Board quickly took advantage of these

powers to create new sources of revenue which, they believed, would

lay the foundations for a sustainable post-war future. In

December 1943 they acquired a road transport subsidiary, Cartwright

& Paddock, to operate in the Birmingham area, and formed four new

subsidiary companies:

-

Grand Union Transport Limited, to take over and expand the

Company’s road transport activities;

-

Grand Union Warehousing Company Limited, ditto

warehousing activities;

-

Grand Union Estates Limited, ditto the Company’s estates;

and

-

Grandion, ditto sports and recreational activities and

interests.

With

the commencement of hostilities in 1939, the Government quickly

moved shipping away from the Thames to west-coast ports that were

more distant from enemy action. As a result, earnings declined

to the extent that the Company was unable to pay its Preference

share dividend and had difficulty meeting debenture interest.

But warehousing continued to turn in good results, with the new

warehouse at Brentford, opened in January 1940, quickly being filled

to capacity. By the end of 1943, the Chairman was able to

report that the Company’s wharfage and warehousing business was

profitable and continuing to expand and that it “was showing

considerable promise for the future”. The prolonged period

of drought that occurred during 1944 reduced the canal’s earnings,

but overall the year compared favourably with 1943 due mainly to

warehousing, wharfage, shipping and the rubbish removal (Thomas

Clayton) subsidiaries turning in good results.

By the end of the war it was becoming evident that the Company’s

post-war future would centre increasingly on its developing

subsidiary businesses, with a gradual move away from its former core

canal business, which was reporting an increasing loss. As the

post war years were to prove, narrow boat carrying was now in

terminal decline:

“All the Company’s subsidiaries in actual operation ― other than

our two carrying companies ― have achieved satisfactory results;

they have all made profits in the period under review, and the

aggregate present value of their assets exceeds the original capital

investment by this Company. Grand Union (Stevedoring and

Wharfage) Company, Limited, in particular, despite the decline in

traffic at the dock arising out of war conditions, has greatly

improved results during the financial period of 19 months ending on

December 31 last.

I should like to make special mention of Grand Union (Shipping)

Limited. This important subsidiary, whose pathway was cleared

by our 1943 Act, has an established position in the short-sea

continental trades. So that it may give in post-war years that

service which its clients expect, orders have been placed for two

new Diesel-engined ships, each 1,100 tons deadweight, to be built to

the most modern specification.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, May 1945

But on 1st January 1948, the Company was sucked into the black hole

of the British Transport Commission. Cartwright & Paddock went

eventually to the Road Haulage Executive and the rest of the Company

to the Docks and Inland Waterways Executive. The profitable

shipping subsidiary was quickly sold off to be followed in 1951 by

Ruislip Reservoir and Lido.

――――♦――――

CANAL CARRYING

Shortly before the amalgamation, the Regent’s Canal and Dock Company

placed an order for a pair of steel narrow boats. Built by the

Steel Barrel Company of Uxbridge, the George (motor) and the

Mary (butty) were of a new design, with deeper holds that

gave a higher freeboard than usual, a feature intended to enable the

pair to navigate safely on the Thames. They could also load to

70 tons compared to 55 tons for a standard pair. [17]

On trial it was found that the hold was too deep for convenient

manual cargo handling, and when loaded to capacity the drag

created when passing over shallow stretches of the waterway slowed

progress dramatically. Despite these drawbacks the pair were

taken over by Associated Canal Carriers who found them sufficiently

successful to justify an order for a further six pairs; these formed

the ‘Royalty class’. Rapid expansion of

the carrying fleet then followed, with two further narrow boat

designs [18] being constructed by various

builders:

“Our subsidiary company, Associated Canal Carriers, Limited

[renamed the Grand Union Carrying Company Ltd. in 1934], is

teaching us many things that can be used to our benefit. For

instance, if we are to secure the increased traffic we are hoping

for this can only be done ― as far as our long-distance traffic is

concerned ― by the building of 100 or more pairs of boats of the

improved type now undergoing trial. When you come to realise

that each half a dozen pairs of boats put on the water, and each

getting normal freights, according to the present average, give us,

say £1,200 to £1,400 a year in tolls, you will see how urgent it is

that some carrying company should initiate a programme of boat

construction. As six pairs of boats cost only £7,500, this

capital outlay, if required to be financed by the Grand Union Canal

Company, would show an excellent return.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1932

The reason for the Company’s heavy investment in canal carrying

stemmed from a belief that there existed good potential for reviving

the long-distance carrying trade based on a modernised

infrastructure, and under those conditions the business would be

there, providing that the Company was able to carry it. As

Curtis put it:

“With regard to the future, I cannot feel anything but very

optimistic. We have been deluged with inquiries from all

directions, but, owing to a shortage of canal boats for long

distance traffic, we have had to turn down trade.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1935

By September, 1936, the new carrying fleet stood at 186 pairs.

But Curtis’s over-optimism had again prevailed, for at the following

year’s General Meeting he was hinting at over-capacity; “Their

craft [the Carrying Company’s] have not been fully occupied

all the time for the reason that it is not an economic proposition

to man boats for which there is not good loading”. In

other words, new boats were lying idle, a wasting asset attracting

capital costs.

|

|

|

John Miller, last GUCC

Chairman. |

In 1936, John Miller joined the

Board and was appointed Managing Director of the Carrying Company,

which he set about reorganising while drumming up new business.

But despite his endeavours, its earnings remained insufficient to

cover the interest and depreciation charges on its new fleet.

In respect of the 1937 financial year, the directors were obliged to

place £11,000 ― substantially the whole of the parent company’s net

revenue ― into reserve against the losses sustained by carrying.

Despite having moved an additional 25,564 tons of cargo in the year,

the Carrying Company was facing fierce competition from road haulage

as well as from rail, both of which were engaged in their own

pricing war, as was rail with coastal shipping. The result was

that reduced rail freight rates (up to 65% on grain) were attracting

business away from the canal. And yet a further problem to

have a telling effect on canal carrying was a shortage of boat

crews:

“. . . . a considerable portion of the fleet is not earning

anything. We are seriously handicapped by the difficulty in

finding captains and mates, and it is becoming increasingly

difficult to obtain them. The problem of manning the boats is

one of the most serious with which we are having to grapple.

In 1937 we had to refuse 40,000 tons of traffic ― a particularly

galling experience, because we had 50 pairs of boats waiting for

crews.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1938

Shortage of boat crews ― a problem encountered during WWI., which

was to hinder canal carrying for the remainder of its days ― does

not appear to have entered into the Board’s calculations when

planning to increase the size of their carrying fleet. The

fact was that boatmen were by now exchanging their demanding

itinerant canal life for land-based employment that paid regular

wages and provided a more comfortable home, with schooling and

welfare services for their families close to hand. When the

Ministry of War Transport took control of the principal canals in

1942, the position had deteriorated to the extent that it was even

referred to in a wartime propaganda booklet:

“In a generation the population of boatmen has become very small.

Think of the life on the boats. The hours are long ― a 12-hour

day is inevitable ― the men may frequently have to load and unload

their own boats at wharves without cranes, for which they receive

extra pay. To hump 50 tons of coal onto the wharf after a

12-hour day is not an attractive prospect. Living conditions

are primitive.

Wages are on the low side. It is true that during these long

hours a man may not be working hard; he may merely be standing at

the tiller. But the life is lonely; the industry has been

largely recruited from those born and bred on the boats; and the

younger generation saw that if they wanted the amenities, the higher

wages, the entertainments of modern life, and better opportunities

for education for themselves and their children, the best thing they

could do was to leave the water.

The earnings on a pair of boats average £7 a week. This looks

well, if the whole of that £7 a week is going into one family; but

not all boats by any means are one-family boats. Usually each

pair of boats has a captain, a mate and a boy, which means that the

captain gets £3.10.0 per week, the mate £2.10.0 and the boy £1.”

Transport Goes to War:

Ministry of Information, 1942

The Company’s publicity material for canal carrying from 1938 (see

Appendix)

gives no hint of their Carrying Company’s manning difficulties,

which resulted in overall losses for that year amounting to £26,863.

[19] Although there had been an increase of 28,111

tons booked, this extra business had to be sub-contracted to

independent carriers due to shortage of boat crews, only about a

half of the fleet being available:

“ . . . . we have felt acutely the shortage of boatmen, and at

the present time we are still obliged to employ outside carriers to

move cargoes for us. There is no doubt that the old canal

boatman is a dying race, and in addition is somewhat of a nomad,

changing his employment from time to time. I have no doubt

that the crisis period

caused a number to move away from areas they expected to be most

affected, and many of them have not yet returned.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1939

In addition to the manning problem, freight carriage in general was

by now being affected adversely by the political situation on the

Continent. Hitler’s annexation of Austria damaged business

confidence, resulting in reduced imports of timber and steel, both

of which were staple canal cargoes from the Thames. The

opening of the London Power Company’s new power station at Battersea

and the growth of the National Grid, gradually caused the small

municipal power stations along the Regent’s Canal to reduce output

and to close, and with them went a useful source of revenue

delivering their coal. In 1929, the Company carried 190,374 tons of

power station coal, earning revenue of £12,429; over the following

decade, this gradually diminished to 11,925 tons in 1938, earning

£993, a decline that was also felt in a loss of dues at Regent’s

Dock.

Following the outbreak of war, the Carrying Company was engaged by

the Government to move foodstuffs from London to the provinces, but

they were again hit by crew shortages. During 1939, 45,915

tons of goods had to be sub-contracted to other carriers while a

large proportion of the Carrying Company’s fleet lay idle. A

further problem to emerge following the commencement of hostilities

was that the volume of cargo arriving by sea at Regent’s Dock

quickly fell away. [20] Trade with Germany (on

average four steamers a week) ceased, while much traffic was

diverted from the Thames to west coast ports. Much of the

coastal coal delivered into Regent’s Dock ― from where it was

shipped by canal to factories and gas works in the West London area

― was transferred to rail, and the extensive Scandinavian timber

trade also diminished. The result was a loss of dock dues and

stevedoring charges, and also in tolls due to reduced shipments

along the Canal. By now the Carrying Company had accumulated

losses of £134,000, largely attributable to depreciation and

debenture interest.

Other than the fall in sea-borne trade into Regent’s Dock, other

wartime events were to have a damaging impact on the Company’s

carrying activities. Because in peacetime the railways had

over capacity, at the outbreak of hostilities the Government

was confident that the railways could handle the nation’s war-time transport

needs supported by road transport and coastal shipping. No

importance was attached to the contribution that could be made by

the independent canals, [21] which were by now

regarded as an anachronism:

“The canals are the poor relation of the railways and the roads ―

a member of the transport family fallen on evil days, who

nevertheless appears to scratch some sort of living together in a

mysterious way.”

Transport Goes to War:

Ministry of Information, 1942

The independent canals were thus left outside government control.

Their boatmen ― already in short supply ― together with other canal

and boatyard workers were recruited into the armed forces, or

departed for better-paid work in munitions factories.

The Government had learned nothing from the previous conflict;

indeed, the situation became a re-run of that which the canals had experienced during WWI.

By the beginning of 1942, it was evident that the railways could not

accommodate the hugely increased level of war-time traffic. In

response to the crisis, Frank Pick, former Chief Executive of the

London Passenger Transport Board and a distinguished transport

administrator, was commissioned to review the situation. Among

his recommendations to the Ministry of War Transport was that the

Government should assume tighter control over transport, including

inland waterways. Thus, on 1st July 1942, the Minister of War

Transport (Lord Leathers) took control of the principal canals and

canal carrying companies.

As in WWI., the business relationship between the Company and

the Ministry of War Transport was not to be a happy one.

Although matters of everyday management did not present a problem ―

these remained in the Company’s hands, subject to the Minister’s

overriding directions ― the financial arrangements did. From

the date when government control was imposed, all companies so

affected lost the carrying subsidy that had until then been in

force, and payment for government work ― which needed to take

account of any losses incurred in meeting the Minister’s directions

― became the subject of negotiation between each canal company and

the Ministry. The offer accepted by the canal industry in

general was that during the period of control, companies would

receive a sum equivalent to their average earnings during the period

1st January 1936 to 31st December 1938, but any earnings exceeding

this figure while under government control had to be surrendered to

the Ministry. In other words, the controlled companies were

made an offer of an assured sum ― no more, no less ― which they

could accept or, if they so wished, decline and take a chance on

their wartime earnings exceeding what the Ministry had offered.

The Board believed that this formula, when applied to them, was

impractical because it failed to take account of the changes that

the Company had been undergoing during the baseline period, and its

acceptance would result in certain loss. Having failed to

persuade the Ministry to improve their offer, the Company decided to

take their chance on outperforming it.

Added to the unresolved problem of carrying charges, the Company had

not been permitted to increase its tolls. In 1940, it had been

permitted an increase of up to 50% ― the average implemented was 33⅓%

― but this should judged against the previous authorised increase,

which dated from 1894; indeed, some rates had remained below the

statutory figures. As happens during prolonged periods of

conflict, inflation increased and with it the cost of canal

maintenance, which, as the war progressed, began to exceed the

Company’s toll receipts, about a quarter of which came from the

Carrying Company’s activities. As the Chairman (John Miller) explained to

the 1945 General Meeting, “this company’s receipts from tolls are

at present insufficient to pay the cost of even a moderate programme

of repairs and renewals”:

|

Year |

Tonnage

Receipts

(Tolls, &c.) |

Maintenance

and Traffic

Expenses |

Net revenue

from Ware-housing and terminal services |

Gross

Revenue

Balance |

|

1938 |

125,748 |

103,613 |

(91) |

68,285 |

|

1939 |

120,991 |

97,058 |

11,269 |

79,524 |

|

1940 |

113,466 |

98,413 |

21,727 |

79,808 |

|

1941 |

143,953 |

108,003 |

42,505 |

125,142 |

|

1942 |

138,618 |

*132,579 |

60,948 |

*114,060 |

|

1943 |

162,925 |

172,725 |

75,764 |

107,312 |

|

1944 |

148,001 |

175,708 |

76,293 |

98,007 |

|

*

Before making a special

provision of £25,000 for dredging Regent’s Canal Dock.

Chairman’s address to the General

Meeting, May 1945 |

Revenue from warehousing and wharfage together with that earned by

the other subsidiaries was by now cross-subsidising the Canal; as the

Chairman went on to explain, “I have no doubt that

our position would be precarious indeed if we had not adopted a

policy of commercial expansion”.

Although the period of government control probably slowed the

decline in canal transport, as it had

during WWI., by 1946 the national network was carrying less

(10 million tons) than in 1938 (13 million tons), a year in which

carrying had been depressed by the political situation in Europe. At the peak of war-time activity in

1944, the canals carried slightly less than 5% of the nation’s total

traffic. [22]

The final years of the Carrying Company saw it suffer the damaging

impact of the old enemy of canal transport to which it, to a greater

extent than its road and rail competitors, was vulnerable ― the

weather. Throughout its life, the mainline had been subject to

the vagaries of ice, drought and flooding (sometimes resulting in

burst banks). The years 1933 and 1934 saw the worst drought

for more than a generation. In June, 1934, the South Leicester

section had to be closed and its water used as a reserve for the

main line, but between July and December the low water level led

to a restriction being placed on the draught of boats, resulting in lost revenue. At the 1935 General

Meeting, the Chairman explained that the Board’s decision not to pay

a dividend on the capital stock for the previous year was due to the

increased cost of pumping, which had added £20,000 to the annual

maintenance bill (£171,000):

“The whole of the year under review has been overshadowed by the

anxieties caused by the abnormal drought. Canals generally

have had no such experience of deficiency in rainfall for two years

consecutively, and as their records go back over 100 years, we must

realise that we are not likely to be again faced with such a

condition of affairs.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, March 1935

But Curtis was, as usual, over-optimistic, for prolonged drought did

indeed recur.

Freezing could be even more damaging to trade. The winter of

1939-40 was the coldest for 45 years, and for six weeks the canal

was frozen over between Birmingham and London. And inclement

weather was to continue during the Canal’s final years:

“Exceptionally dry weather, dating back to the latter part of

1942, culminated in 1944 in one of the most serious droughts, from

the Company’s point of view, in its history. There were grave

fears that the main line of the canal from London to Birmingham

might have to be closed. But we have for several years been

modernizing and increasing our pumping plant and we had the

foresight to close our South Leicester Section as far back as

December 1943, in order to preserve a supply of water for the more

important Braunston Summit. For these reasons and through the

splendid work of our engineer, Mr. C. A. Wilson, and his staff, we

were able to keep the main line open. For a considerable

period, however, the draught of boats had to be restricted and there

was an inevitable decrease in tolls and a substantial increase in

the cost of pumping.”

Chairman’s address to the General Meeting, May 1945

The winter of 1946-47 experienced the longest spell of continuous

frost for 106 years, and canal carrying suffered as a result:

“The year 1947 was full of major problems. Costs and

general expenses rose and increased revenue was hard to obtain.

The severity of the winter, when our main waterway was frozen over

for four weeks and we were further inconvenienced by subsequent

floods, caused great expense and loss of revenue.”

Chairman’s address to the (final) General Meeting,

October 1949

But the weather soon ceased to be of consequence to the Company’s

profit and loss account.

On 1st January 1948 its carrying subsidiaries were

taken into State ownership and, as commercial entities, they ceased to exist.

Ironically, the under-employed carrying fleet ― 126 motors

and 130 butties, of which about 70 pairs were in commercial use ―

was soon to be increased, for having incurred a trading loss

during the first six months of 1948, the large private canal

carrier, Fellows, Morton & Clayton Ltd., went into voluntary

liquidation and their assets were acquired by the British Transport

Commission. As from 1st January 1949, their South-eastern

Division’s already bloated carrying fleet received a further boost

of 100

pairs of FMC boats. Thus, State-owned canal carrying on the

Grand Union Canal began life with what was probably the largest

fleet of canal boats ever assembled under a single management.

――――♦――――

DID AMALGAMATION PROVE SUCCESSFUL?

Over the years various government-sponsored committees of inquiry

had reached the conclusion that canal carrying could only operate

successfully through of programme of mergers, such as those that had

led to much of the success of the railway companies. Canal

company mergers had the potential to eradicate the chaotic charging

structure and make possible the removal of that blight of canal

operation, the lack of standard measurements in their construction

(again achieved by the railways early on). The question

therefore arises as to the extent to which the formation of the

Grand Union Canal Company resulted in any material benefit along

these lines. Here, the indications are that canal carrying had

had its day and that no amount of modernisation of the Grand Union

network would have led to a different outcome. That

said, there are clear indications that the Company would have

survived, but as an integrated transport operation that relied less

and less on its canal operations. What would have become of

the waterway under these circumstances is a matter of conjecture ―

nationalisation did at least have the effect of preserving it.

The Atlee Government’s nationalisation programme could not have been

foreseen in 1929. Had it ranked among the risks then facing the

Company, it is likely that the investment programmes of the 1930s

would not have received shareholder endorsement. The new Board undoubtedly based their

business strategy on

a vision of an unfettered future. That said, some of the assumptions underlying their investment

appraisal calculations appear questionable, not least the

sufficiency of the capital required to complete the modernisation

plan and the extent of the financial return necessary to make it

pay ― a matter of costs and benefits. And regardless of

whether there was reasonable expectation of sufficient cargo to fill

the boats, the existing shortage of boat crews alone brings into

question the decision to invest in a large carrying fleet on which

capital charges had to be paid. Following

the top management shakeup in 1936, it is easier to understand the

new Board’s strategy to diversify further, for by then it must have

been apparent that the long-distance carrying trade could not compete favourably with road and rail.

During the Company’s 18-year life, canal transportation continued

its long-established decline, being superseded increasingly by road

transport as well as by rail. This aspect of the

Company’s business reflects the national trend, where tonnage fell

from 22 million tons in 1919, to 15.5 million tons by 1927, to 13

million tons by 1938, to 10 million tons in 1946. There then

followed a slight recovery to 11.3 million tons in 1949, after which

canal carrying gradually died. The narrow canals suffered the

most, and for most of its length the Grand Union was a

narrow canal for commercial purposes.

The Company’s published tonnage figures, where they exist, provide

one indication of commercial activity, but only that, for the data

gives no hint of freight rates and ton-miles. But with that

caveat, and assuming that the data was gathered in a consistent

manner, it demonstrates a downward trend. Tons carried were,

for 1931 1,870,718; 1932, 1,638,443; 1933, 1,685,487; and for 1934,

1,726, 344. There is then a gap in the publically available

figures until 1938-39, a period undoubtedly affected by the adverse

political situation in Europe, by which time tonnage had declined to

around 1.2 million tons. Thus, although it may well have

slowed the rate of falling canal revenue, the cost of modernising

and extending the waterway does not appear to have delivered any

material benefit. By the end of the WWII., in the words of the

Chairman, net toll receipts were “insufficient to pay the cost of

even a moderate programme of repairs and renewals”.

Another indicator of commercial success ― albeit including other

activities ― is the rate of dividend paid on the Company’s stock.

For the first complete year of trading (1929-30), the capital stock

fell to 1⅜% compared with the 4% usually paid by the Grand Junction

and the 2% by the Regent’s Canal. There then followed a

downwards drift to ⅞% in 1933 after which the dividend was suspended

until 1945, when distribution resumed at 1%. Dividend

increased to 2% in the following year and ― despite experiencing a

dreadful winter during 1947-48, when the waterway was frozen over

for thirteen weeks ― to 2.8% for the Company’s final year of

trading, the Government having blocked an attempt by the Board to

pay 5.8%. The 6% Preference shareholders fared rather better.

Their dividend was suspended between 1937 and 1941, to be restored

in full in 1944, when 3% was also paid retrospectively for 1942 and

1943. Regarding share price, we have been unable to establish

the market value of the capital stock at nationalisation, but by the

end of the war a £100 share was trading at around £22; judging from

the Chairman’s address to the closing meeting in 1949, share price

remained below par at nationalisation. The indications are

that the Company was a poor investment from both the Capital and

Preference shareholders’ points of view.

Although the Company’s performance should be judged in the

context of the ‘Great Depression’ and of WWII., the Board’s unrealistic assessment of the potential for

reviving long distance canal transport and the costs which that

would entail must have been the

dominant factor in its declining income. There was insufficient

capital to bring about the necessary transformation; to turn the London to Birmingham and

the River Trent routes

into barge canals on which much larger loads could be carried by

pairs of wide boats of the Progress class and to use such

craft to eradicate the transhipment costs and delays that resulted

from narrow boats being unable to load directly from ships in the

Thames and the London Docks. Lock widening on the Warwick

canals did improve traffic flow, but for most of their length the main routes

remained ‘narrow’ so far as through traffic was concerned ― the job

was left half done:

“The Grand Union Canal throughout its length presents special

features . . . . As far as the length from Uxbridge to Birmingham is

concerned, the question has often been debated whether it is or is

not a ‘narrow’ canal. The facts are these. The canal was

constructed for use by wide boats as far as Braunston. A

substantial scheme on converting the waterways as a whole into a

wide canal was put in hand by the former owners between the wars and

all the locks can accommodate craft 14ft x 70ft. [23]

But the scheme was never completed and substantial amounts of

ancillary supporting work (estimated several years ago to cost

several million pounds) would be necessary to enable wide craft to

use the waterway in a fully effective way (to pass each other

practically wherever they happened to meet, for instance).

From the point of view of commercial carrying, therefore, the Grand

Union system must be treated as within the group of narrow canals .

. . .”

The

Facts About the Waterways, British

Waterways Board, London, 1965

The heavy investment in extending and modernising the waterway

having failed to earn a sufficient return left the Company’s small

carrying and toll margins highly vulnerable to such ailments as

shortage of boat crews and the vagaries of the weather. But

had the capital been available to achieve the full extent of

modernisation ― including widening the Watford and Foxton locks ―

would canal traffic have increased sufficiently to repay the higher

capital costs and provide a reasonable return? The growth of

road transport coupled with the lowering of freight rates as the

canal’s competitors (road, rail and coastal shipping) fought each

other for market share, suggest that even if a significant increase

in trade had been won it would have been at unattractive rates and

unlikely to have delivered material benefit. During the 1930s,

some waterways did gain traffic and remained commercially viable

into the post-war years. But these were waterways ― such as

the Aire & Calder, the Sheffield & South Yorkshire, and the Trent

systems ― that had been improved considerably (widened, deepened,

straightened) to enable them to handle craft of well over 100 tons

capacity. They were also the carriers of heavy local trades in

coal and bulk liquids.

But on other side of the business there were encouraging signs of

progress. By the end of WWII., through its subsidiaries the

Company had evolved into an integrated and sustainable transport

operation with interests in stevedoring, warehousing, shipping, road

haulage, property and even leisure. Here the future looked

reasonably bright. Had the Company not succumbed to

nationalisation, one is left to wonder how the business might have

developed; whether it would have moved increasingly into shipping,

warehousing and road haulage; whether its leisure subsidiary might

have recognised the waterway’s potential for leisure cruising long before

the State; and how the change to containerisation and the closure of

the Port of London would have been dealt with.

At the Company’s final General Meeting in October 1949, John Miller had this

to say:

“I hope that as this is our final meeting, you will permit me to

refer to the achievements of your Board, which you will remember was

reconstructed towards the end of the year 1936, when the Company was

undoubtedly in a very precarious condition, and it may be admitted

that the policy introduced of broadening the business and the

introduction of a better all-round transport service to our clients

met with the success which we had hoped. . . .

It is regrettable that the nationalisation of transport had to be,

for I had reasonable hope that before long our capital stock would

have reached par value, which would have afforded your Board great

satisfaction. . . .

There is no satisfactory substitute for private enterprise in the

business of transport, whether by sea, land or air, and this simple

fact will be discovered as time goes on . . . .”

. . . . and such proved to be the case.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

(Grand Union Canal Company publicity material c.

1938)

THE GRAND UNION CANAL CARRYING COMPANY LIMITED . . .

.

. . . . owns the

largest fleet of mechanically-propelled canal craft in the country,

consisting of 185 pairs of Diesel-engined canal boats of a type

evolved after six years’ experiment in design. The high-speed

Diesel engines give a loaded speed of six knots, and whereas the old