|

――――♦――――

Aylesbury Basin, the Waterside Theatre in the

background.

BACKGROUND

“Within the last few days Baron Nathaniel de Rothschild has died

in Paris. In his young days the Baron was a most fearless

rider, and not to be stopped by any fence so long as his horse could

go. The Vale of Aylesbury was then a rough country indeed, and

was not gated as at present, nor was there a bridge over every

brook. But Baron Nathaniel cared nothing for falls, and twice

in one season he swam the canal between Tring and Aylesbury.”

Bailey’s Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Vol. 18 (1870).

IT is likely that

the Baron retains the world record for completing that particular

swim in whatever time he took ― whether he got out at the locks

or was locked through by the family retainers is unrecorded.

|

|

|

Narrow boats in Aylesbury Basin.

The former power station is in the background. |

In 1792, the canal engineer James Barnes [1]

surveyed a route for a canal that was

to connect Braunston on the Oxford Canal in Northamptonshire, to

Brentford on the Thames. With little change the route

he surveyed is that followed by the Grand Junction Canal (GJC) today

(since 1929, the southern section of the Grand Union Canal).

Following

completion of the survey and its publication, investors flocked to

sink their money into the project, for this was the age of

“canal

mania” and it was perceived that there were big profits to be made

from any new canal scheme; in the case of the

Grand Junction Canal Company (GJCC) this was so, until the

coming of the railways in the 1840s, when this new and quicker form

of transport captured much of its business.

A general committee was quickly formed from among the

scheme’s subscribers under the chairmanship of the banker, William Praed

(1747–1833). Having obtained an Act of

Parliament authorising them to build the Canal,

“The Company of Proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal”

(as the Act described them) pressed

ahead with its construction together with surveys for a number

of branch canals that were intended to connect the main line with

important towns that lay in its vicinity. In later years the

Company obtained Acts of Parliament

to build some of these branch canals, but

the schemes only proceeded after much debate, or not at all, for what appeared at first

sight to be an attractive business proposition looked much less so when the

water requirement and its supply had been investigated, the scheme’s

opponents had made their objections known, and a

cost-benefit analysis had been weighed against the GJCC’s burgeoning

financial commitments elsewhere. [2]

|

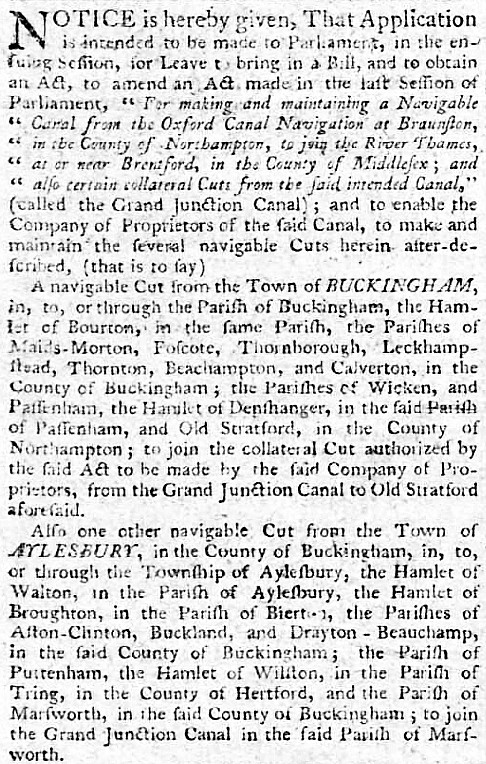

The statutory notice announcing the

GJCC’s intention to apply for an Act to build the

Aylesbury Arm ― the advertisement also dealt with the

Wendover and Buckingham branches and the proposed

branches to Dunstable and St Albans.

Northampton Mercury, 14th

September 1793. |

As early as 1793, a branch canal to Aylesbury had been surveyed and the

land owners that were to be affected by the proposed scheme approached to establish whether

they would be prepared to accept the Company’s offer to purchase. Evidence later

given by William Jessop (the GJC project’s Chief Engineer) and Acton Chaplin (the GJCC’s Clerk) before a

parliamentary committee suggests that the Company was, at that time,

intent on building several branches, including that to Aylesbury:

“William Jessop, Esquire, being examined, said, That the

Petitioners are now proceeding to make the said Canal, agreeable to

the Powers vested in them by the said Act. That by Levels and

Surveys, lately made, it appears practicable to make certain

Navigable Cuts from the several Towns of Buckingham, Aylesbury, and

Wendover, in the County of Buckingham, and also from the Town of

Saint Alban, in the County of Hertford, to join and communicate with

the said Grand Junction Canal and Collateral Cuts, or some of them.

Acton Chaplin, Esquire, One of the principal Agents to the said

Grand Junction Company, being examined, said, That the said Company

are willing, at their own Expense, to make and maintain the said

several Navigable Cuts.”

Journal of the House of Commons, Vol. 40, (1794).

The Aylesbury Arm did eventually come into being, but only after a

long and difficult gestation and then without the significance of

being the first section of a grand plan to link the GJC main line at

Marsworth and the Wilts & Berks canal at Abingdon (and then onwards to

the Somerset coalfields). The Arm was to remain a cul-de-sac,

but one that

did enjoy some prosperity in its early days. However, in 1838 work began on

building the Aylesbury to Cheddington branch railway (some of the

sleepers for which were shipped by canal to Cheddington and Broughton

wharves), which

ran more-or-less parallel to the canal to make a connection with the London & North Western Railway’s main

line. Following its completion in 1839, the Cheddington Branch gradually drew away much of the canal’s traffic.

But, ironically, it was the railway that was to

disappear in 1964,

a victim of the Beeching Axe, while the Aylesbury Arm managed to

struggle on into the age of leisure boating and survival. In 2007,

British Waterways sold the canal basin to Aylesbury Vale District Council,

and today it forms the focus of a multi-million pound waterside

redevelopment; Aylesbury High Street Station, terminus of the

Arm’s erstwhile competitor, now lies beneath shops.

――――♦――――

Marsworth staircase locks. Unlike the main line, the locks

on the Arm are narrow

(i.e. 7ft compared with 14ft).

One of a number of English Heritage ‘listed’ structures of the

Aylesbury Arm . . . .

Locks 1 and 2 Grand Union Canal Aylesbury Arm

GRADE II

Date Listed: 15 October 1984

English Heritage Building ID: 42091

|

“Narrow

double lock at entrance to Aylesbury arm. 1811-14. Brick retaining

walls, the lower lock with brick coping, the upper lock with stone

coping. 2 flights of brick steps on N. side. E. end of upper lock

has single gate with sluice, winding gear and quoins dated 1878. 2

other pairs of narrow gates with sluices, the centre gates with quoints dated 18?6. 5 cast iron bollards.” |

|

Sales

by Auction

――――

BUCKS

A Capital and Commodious

FREEHOLD WHARF, IN FULL TRADE,

Immediately adjoining the Grand Junction Canal and the

High Road at Marsworth, in the county of Bucks.

By GLENISTER and

KNIGHT.

At the ROSE and CROWN

INN, Tring, Herts, on Wednesday

the 19th September, at Three o’clock in the afternoon,

comprising

AN excellent DWELLING

-HOUSE, and Grocer’s

Shop, Warehouse, Stabling for 18 horses, and other

convenient Buildings, brick-built and slated and in sub-

stantial repair. The whole Let at an annual Rent

of £60

and possession of which will be given at Michaelmas

next.

Particulars may be had at Griffin’s, Green Man and

Still,

Oxford-street, London; at the Inns in the neighbouring

towns; of Mr. Giles Willis, solicitor; and of the AUC-

TIONEERS, Tring; also of Mr.

Gregory, Marsworth, who

will show the premises. |

The Bucks Chronicle, 8th September, 1821.

――――♦――――

WATER

SUPPLY AND CONSTRUCTION

CONSTRUCTION

of the Aylesbury Arm was authorised under the second GJC Act (1794), but

because the main line had yet to reach the planned junction at

Marsworth, nothing further was done. When, in 1800, the main line

did reach Marsworth, the GJCC declined to commence work on the Arm.

There was probably two reasons for the Company’s reluctance. First, the cost of building the

main line was running well over budget and the Company was having problems

enough raising sufficient capital to complete it without the added

expense of a branch canal. Second, there was difficulty in

providing this section of the main line with sufficient water

without adding a branch that would increase demand on the limited

supplies (the fall from

Marsworth Junction to Aylesbury Basin is almost 95 feet). But

regardless of the GJCC’s problems, the

citizens of Aylesbury continued to press for a canal to compete

with nearby Wendover, where a

branch had been open for trade since

c. 1799.

To placate the townspeople, the GJCC offered them an alternative to

a canal and by September, 1800, their Clerk was at work on a notice

inviting subscriptions to a £5,000 loan with which to commence “the

immediate prosecution of the works for making an Iron Rail-Road from

the said canal to the Town of Aylesbury”. The rate of interest

on the loan was

to be 5%, with £20 per cent to be paid on acceptance.

The railway, had it been built, would have been

horse-drawn. Such a line was already in use between Stoke

Bruerne and Blisworth, where it bridged the

gap in the canal caused by the excavation of the Blisworth

Tunnel having to be abandoned through severe flooding. It seems that the appeal

was successful, the Marquis of Buckingham and the GJCC Clerk, Acton

Chaplin, being among the subscribers. On 15th December 1802,

Barnes (the GJCC’s Resident Engineer) wrote to Chaplin to apologise

for missing an appointment; he then went on to say that he intended

to visit shortly “and determine to the best of my

knowledge, whether it will be best to have a Canal or Rail Road to

Aylesbury.” The decision taken was to build the “Rail Road”,

which was cheaper to construct and offered the

advantage of not drawing water from the main line, at the

time in comparatively short supply. Although the rails were

bought, they were used instead to assist in

building the canal embankment across the Great Ouse at Wolverton.

In June 1803, at a meeting chaired by William Praed, Barnes, Holland

and Barker (the latter two being surveyors) were instructed to

provide the Committee with a plan and estimate for “the intended

navigable cut from Marsworth to Aylesbury”. Nothing constructive

appears to have been done, for by October 1805 the subscribers to the rail road loan

were seeking legal advice on obtaining a writ of mandamus against

the GJCC. The opinion they received from counsel was that this strategy would

be difficult to achieve, and so a different approach for

obtaining a remedy was adopted, that of applying for an Act of Parliament

(the scheme for a railway seems, by now, to have been abandoned). The

following notice then appeared in the official newspaper of record:

“NOTICE is hereby given, that Application

is intended to be made to Parliament in the next Session for Leave

to bring in a Bill, and to obtain an Act, to require and compel the

Company of Proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal to take such

Steps as shall be necessary and proper for beginning, carrying on,

and completing a Collateral Cut from the Town of Aylesbury, in the

County of Buckingham, to join the Grand Junction Canal in the Parish

of Marsworth, in the said County, under and according to the

Provisions and Powers of the Act of Parliament, made and passed in

the Thirty-fourth Year of the Reign of His present Majesty . . . .”

London Gazette, 2nd September 1806.

The bill also required the GJCC to cease paying dividends until they

had set aside the sum they

had agreed to expend on the Arm, this being £20,256. This

tactic

must also have failed,

for nothing further is heard of it.

In 1810, yet a further approach to obtaining a remedy emerged, that

of petitioning Parliament:

“The want of water has hitherto prevented the Grand Junction from

completing a cut to Aylesbury, and occasioned a petition from the

Marquis of Buckingham, which was presented to the House of Commons,

on the first of March last, requesting no further extensions might

be granted to the Grand Junction, till that Company shall have

fulfilled their engagements with Parliament, by making a collateral

cut to Aylesbury.”

Two Reports of the Commissioners of the Thames Navigation, 29th

December, 1810.

However, by then progress on the Aylesbury Arm had become of keen

interest to others beyond the town, including the above-mentioned

Commissioners of the Thames Navigation. Their interest stemmed from

the completion in that year of the Wilts & Berks Canal, which linked

the Kennet and Avon Canal near Melksham to the River Thames at

Abingdon. In order

to reach London, traffic from the Wilts & Berks needed to use the

Thames, a river in which navigation was difficult in the upper

reaches while its sinuous path provided a lengthy route to the

capital. And so an alternative waterway was planned, to be named the

Western Junction Canal. This was to extend from Abington to

Aylesbury (36 miles) where it would connect with the planned

Aylesbury Arm to provide a link to the GJC main line at Marsworth.

By this means, so the canal’s advocates claimed, the journey from

Abingdon to Brentford would be shortened by 14 miles and made over a more

reliable waterway.

“It is notorious to all of you that the Navigation of the Thames,

from Lechlade to Oxford, is not only tedious at all times, and very

expensive, but, frequently impassable for months together; in Summer

for want of Water, and in Winter from Floods, in consequence of

which, and the enormous expense of its navigation, your supply of

Coal, Stone, and other articles cannot be brought to you nearly upon

such easy and cheap terms as they would be if Canal Communications

were effected . . . . In respect of the proposed WESTERN

JUNCTION CANAL, there

can be no possible doubt of its great PUBLIC UTILITY

and the advantages that will result from it to you,―for should it

take place the COALS brought up the WILTS

and BERKS CANAL will go as far as THAME

at least, which will operate as a useful check on the Oxford Canal

Company, and keep down the price for your benefit, and which,

without competition, will be increased upon you, without any means

on your part to prevent it . . . .”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

26th January, 1811.

An extract from one of the many advertisements

supporting the proposed Western Junction Canal. Probably just

as many opposed it.

|

.jpg) |

|

Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 6th

September, 1828.

The final attempt to ‘float’ the

WESTERN

JUNCTION CANAL. |

During 1810 and the early part of 1811, a flurry of notices appeared

in the press in which the proposed Western Junction’s advocates and

detractors pleaded their cases, potential investors were canvassed

and public meetings were announced. At the head of the opposition

were the Thames Commissioners, who saw the Western Junction

diverting trade, and hence their revenue, away from the Thames

between Abingdon and London. The opposing forces were finely

balanced, but when the Bill went before Parliament in 1811, the

detractors prevailed and it was defeated by a majority of ten. [3]

But by then the prospects of the Marquis of Buckingham’s

petition forestalling the GJCC’s ambitions elsewhere succeeded in bringing

about a settlement, with the Company finally agreeing to build the

Aylesbury Arm. The solution to the water supply problem was resolved by a

proposal to construct new reservoir capacity, this being provided

for in a further Act of Parliament:

“The Company to make a reservoir of at least 15 million cubic

feet of water at or near the summit level, for supplying water which

formerly flowed into the Thame, from Wendover etc. within three

years of the Act, and to send down 15 million cubic feet between May

10th and October 30th each year into the Thame. Reservoir may

be discharged into the Aylesbury Arm and supply the Thame through

it. A superintendant to be appointed to see that the water is

not used for any other purpose. If the regular passage of

boats along the Aylesbury Arm provides the requisite flow of 600,000

cubic feet per week, the duties of the Superintendant may cease.”

52 Geo. III, C.140: Royal Assent 9th June, 1812.

Work commenced on Tringford Reservoir in 1814, followed by Startops

(pronounced “Starrups”) End Reservoir at Marsworth a year later.

They were completed by 1817, both taking surplus water from the

Tring Summit (supplied mainly from the Wendover Stream). In

the meantime, Henry Provis Snr. was appointed the scheme’s Engineer

and in August, 1811, work commenced on the new canal at Aylesbury and at

Marsworth. Two years later, Provis was able to report that some two

thirds of the distance had been cut, eleven of the locks and ten of

the bridges had been completed and work was progressing

elsewhere.

In July, 1813, a sale by auction was advertised of “improvable land

contiguous to and at the termination of the collateral cut from the

Grand Junction Canal to Aylesbury . . . . extremely desirable for

the erection of wharfs, warehouses and buildings.” The ground

plan that accompanied the advertisement shows the canal terminating

in Aylesbury at Walton Street, but without any indication of the layout of what

would later become Aylesbury Basin. Potential buyers were

alerted that “These lots are sold subject to the power of the GRAND JUNCTION

CANAL COMPANY to purchase sufficient

Ground for the forming of

Wharfs, &c. in case the Owner or Owners shall neglect to do so on

Twelve Months Notice. . . .” which suggests that Aylesbury Basin,

with its once extensive wharfs and warehouses was probably not built

until some time after the Arm had opened. When exactly the opening

took place is unclear; some sources give 1815, but local historian

and onetime Editor of the Bucks Advertiser, Robert Gibbs, states

that:

“The Aylesbury Branch canal was finished in the spring of 1814,

and opened in the month of March in that year, a year noted for its

intense and prolonged frost. . . . The construction of the canal was

an event of great importance to Aylesbury; its opening was the

occasion of a general half-holiday amongst the townsfolk. This

branch not only connects the town by a waterway with other towns in

the district, but by the Grand Junction forms a link with London and

with other canals in the North. By this new source Aylesbury

obtained what it never before possessed, viz., means for the

transport of heavy merchandise to and from all parts of the

country.”

Buckinghamshire: A History of Aylesbury, Robert Gibbs (1885).

And so the Aylesbury Arm was completed, but at an unexpected cost to

the GJCC shareholders who, for the half year ending 31st March,

1816, received no dividend:

“. . . . for the following reasons, viz. . . . . to complete Two

Reservoirs forming on the Tring Summit . . . . and also to discharge

bills for completing the Canals to Aylesbury and Northampton . . .

.”

Circular to GJCC shareholders, 13th June 1816.

Much to his chagrin, Henry Provis’s work on the Arm was

criticised and he was forced to ask the Company to have the canal

inspected by a competent but independent person to exonerate his

professional reputation. The “inspector”

turned out to be none less than Thomas Telford, who in his report

stated that “. . . . upon the whole this

branch of Canal is at present in a very perfect state and will, he

had no doubt, answer its intended purpose. . . .” It might be

coincidence, but Telford was later to employ Provis’s sons John and

William [4] on some of his major projects, including the Holyhead trunk

road.

Unlike its lockless and meandering neighbour, the

Wendover Arm, the

Aylesbury Arm follows a

fairly straight and declining path to its destination. Commencing at Marsworth

Junction, 45ft below the Tring

summit, the Arm falls 94ft 8ins during its 6¼-mile journey, negotiates 16

narrow (7ft wide) locks ― the first two at Marsworth forming the

only staircase on the original GJC system [5]

― and passes 20 bridges, all but

one still being in their original condition. There is only one winding hole,

which is located to the

west of College Road Bridge (No. 9).

The Arm is supplied with water from three sources:

-

(principally) the Marsworth Pound via lock No. 1, over the head

gate weirs;

-

Wilstone Reservoir, via the sluice on Gudgeon Brook; and

-

Draytonmead Brook.

Much of this water is from Wendover via the Tring Summit and

Wilstone Reservoir. The three outflows from the Arm are over:

-

a weir into Draytonmead Brook near Merrymead Farm;

-

the offside (opposite the towpath) bank of the canal in the two

mile pound

between College Road and Broughton Lane, and

-

a weir into California Brook at Aylesbury Basin . . . .

. . . . all water eventually entering the River Thame.

――――♦――――

Black Jack’s lock (No. 4).

――――♦――――

THE COMMERCIAL CANAL.

“Among the general improvements which have rapidly followed each

other in modern days, the conveyance of goods and merchandise, by a

branch of the Grand Junction Canal from the principal trunk at

Marsworth to Walton, and the more recent completion of the line of

railway communication, are said to have materially contributed to

advance the benefits of all classes here, and effected a highly

favourable change in the manners and habits of the people.”

The History and Antiquities of Buckingham, George Lipscomb (1847).

FOLLOWING its opening, the Arm became well used. Although there were

wharfs along it, trade

centred on Aylesbury Basin where (in common with other towns on or

near a canal) coal prices fell dramatically, from 2s.6d. to 1s.3d.

per cwt. Other commodities discharged in the early years included

the usual timber and building materials, while exports were

predominantly agricultural. Barge-loads of emigrants destined for

the Americas via Liverpool, and soldiers and convicts being

transported to the coast from Aylesbury also used the canal; this

particular trade was later taken over by the Cheddington branch

railway and, so far as paupers for the colonies was concerned, with

the enthusiastic support of workhouse superintendents it flourished.

It is unclear how many wharfs lay along the Arm. Until 1917 at

least, there

was a coal wharf at Wilstone operated by W. F. Jeffery, but it was

not secured and local folklore has it that pilferage led to its

abandonment. There is also evidence of wharfs at “Red House”,

servicing Aston Clinton (until the late 19th century, also served by Buckland Wharf on the

Wendover Arm) and at Broughton. In addition to established wharfs,

agricultural produce, such as hay and straw, was probably loaded

into barges from accommodation bridges while manure, lime and “sweepings” were discharged between barge and canal bank over planks.

Looking west from Bridge No. 6.

During the nineteenth century, the population of Aylesbury began to

grow in line with the general drift from countryside to town. Indeed,

better transport communications helped attract businesses to the

town, a number of which made use of the canal. The book printer

Hazel, Watson and Viney moved to Aylesbury in 1867, and a decade

later was employing 200 people. The company used the canal to transport

straw board. The Aylesbury Condensed Milk Company (later

the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company and Nestlés) established a

canal-side factory in 1870. They started with a workforce of twenty

and a decade later were employing fifty, mainly young women involved

in filling, sealing, labelling and packing tins of condensed milk:

“The filled tins are now transferred to the packing-room, where

they are neatly labelled and wrapped in paper. Boxes, all

exactly of the same size, are prepared on the premises, and in them

the tins are packed, ready for delivery; these packages are passed

down a shoot from the upper part of the premises to the Company’s

wharf, and quickly conveyed to the barge lying in the canal to

receive them.”

Buckinghamshire: A History of Aylesbury, Robert Gibbs (1885).

In 1891, the old Walton water mill on the Bear Brook was bought by

flour millers Hills and Partridge, who erected new buildings on the

site. The firm had their own wharf and much of their raw materials

and produce arrived and departed by canal. Canal transport was also

the reason for siting the town’s electricity works, timber yard and

the all-important coal yard at the canal basin. However, more sustained

railway competition came in 1892 with the Metropolitan and, in 1899,

with the Great Central railways. Activity on the Arm diminished

still further after WWI with the growth of road transport, which by

then was also making inroads into railway

business.

AYLESBURY ARM

At Marsworth junction is a branch of the canal connecting the main

line with the town of Aylesbury, the distance from the junction to

the town being 6¾ miles. At Aylesbury are to be found numerous

firms taking advantage of canal transport. Coal is taken to

the Electricity Works, as well as to other premises and, in

addition, timber, grain, wire, building materials, and straw board

are dealt with. Mr. A. Harvey Taylor, canal carrier, has his

wharf at this point.

Grand Union Canal Company advertising material, c.

1938.

By WWII, trade on the Arm had become sporadic,

although the hostilities provided a brief revival ― aluminium ingots were carried by canal from London to International

Alloys for casting into billets before being sent by canal to Birmingham for use in the manufacture of aero-engine cylinder blocks.

Following WWII, canal traffic in general fell into serious decline. Little money was spent on maintenance and in tune with this the Arm

deteriorated rapidly. Data published in the Rusholme Report [6]

illustrates the extent to which trade had declined by the early

1950s; none is recorded as having originated on the

Arm in any of the three years analysed in the Report, while income

and expenditure were recorded as follows:

|

ANALYSIS OF INCOME 1951, 1952 & 1953 |

|

YEAR |

Tolls

& dues

£ |

Water

rents

£ |

Other

rents

£ |

Misc.

£ |

TOTAL

RECEIPTS

£ |

|

1951 |

50 |

43 |

867 |

5 |

965 |

|

1952 |

22 |

43 |

859 |

4 |

928 |

|

1953 |

11 |

43 |

848 |

4 |

906 |

|

ANALYSIS

OF EXPENDITURE

1951, 1952 & 1953 |

|

YEAR |

Locks &

Lock gates

£ |

Canal &

river banks

£ |

Bridges &

tunnels

£ |

Buildings

let to

tenants

£ |

Other

buildings

£ |

Motor

vehicles

£ |

Plant &

machinery

£ |

Misc.

£ |

Engineering

admin.

£ |

TOTAL

EXPENDITURE

£ |

|

1951 |

131 |

532 |

15 |

4 |

48 |

1 |

- |

1 |

274 |

1,006 |

|

1952 |

16 |

919 |

16 |

25 |

2 |

11 |

1 |

61 |

218 |

1,269 |

|

1953 |

24 |

793 |

65 |

15 |

- |

1 |

1 |

70 |

231 |

1,200 |

. . . . in other words, canal carrying was earning next to nothing,

and overall the Arm was losing money. Against this background

― and that of numerous other waterways that shared the Arm’s

loss-making capacity ― it is unsurprising that Rusholme recommended

[7] that:

(iii) the [British

Transport] Commission concentrate on those

waterway activities which are of real value as part of the transport

system and to be relieved of the remainder, which are placing a

heavy burden on the waterways administration and finances;

(iv) certain defined waterways are to be developed, others are

to be retained for navigation and the remainder are to be regarded

as having insufficient commercial prospects to justify retention for

that purpose.

In 1959, the Arm gained a reprieve from permanent closure

when a new boat hire company set up business in Aylesbury

Basin. A brief diversification into coal and timber carrying resulted in a

limited amount of dredging, but overall it was a losing battle.

――――♦――――

The sole remaining

business on the Arm is

Jem

Bates’ boatyard at Puttenham.

Following nationalisation in 1948, control of inland waterways was

vested in the gargantuan and lethargic British Transport Commission.

Under the Transport Act, 1962, the Commission was replaced by five

successor bodies of which the British Waterways Board (BW)

took over the management of the inland waterways. An early

task for the Commission was to reshape national waterways policy,

particularly as it affected canals, which were making a considerable

loss,[8] some

being in derelict condition. Thus, BW set about a comprehensive

review of their estate to establish the facts.

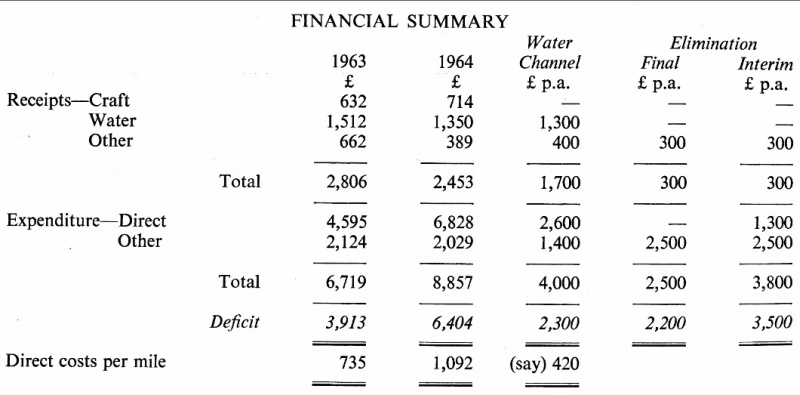

The figures that appeared in the section of their published report [9]

dealing with the Aylesbury Arm [App.]

reveal that in the decade following Rusholme (see above), receipts had grown substantially but so had

expenditure, resulting in a higher annual deficit: £3,913 for 1963

(£2,930 at 1953 values based on the RPI), and £6,404 for 1964

(£4,800 at 1954 values based on the RPI). Perhaps more

interesting is the value that BW placed on converting the Arm to a

water channel [10]

― about £2,300 p.a. ― and of eliminating the waterway

entirely [11]

― £3,500 p.a. reducing to £2,200 p.a.

Fortunately, BW took no immediate action to implement the thrust of

their findings, for the Board recognised that new and wider

implications had by now to be taken into account before any decision

about a waterway’s future could be reached:

“As far as the wider aspects of waterways problems are concerned,

it has been impressed upon us that there is a steady and rapid

growth of interest in (and perhaps anxiety about) the use of

leisure, out-door recreation and the future of the countryside.

Moreover, as will be seen, our studies have led us ― regretfully ―

to judge that there is no hope of many of the waterways balancing

income and expenditure ― at any rate for many years to come.

Clearly, therefore, the question of the future is not one that can

be resolved simply on commercial grounds; it brings in broad social

questions as well. As far as the broader questions are

concerned we realise that we form only part ― we think a unique part

― of a bigger subject, the subject of general future policy towards

recreation.

So we think we ought to make the facts generally available for

consideration by all concerned.”

The Facts About the Waterways, British

Waterways Board, London, 1965.

The 1960s proved to be the low-water mark in the Arm’s fortunes. Commercial traffic ended in 1964 with the last regular delivery of

coal, the boat hire company ceased trading and wharf-side buildings

and warehouses were demolished. Aylesbury Council expressed an

ambition to fill in the basin and, for good measure, sought to have

the entire Arm abandoned.

In 1961 the Inland Waterways Association held their National Rally

at Aylesbury Basin. It was a great success, for by then

leisure boating was beginning to become a popular pastime.

But the real change came in 1968, when Barbara Castle’s Transport

Act gave the first government recognition to the recreational value

of waterways, with a new remit for BW to develop their leisure

potential. Due to long-term underfunding, little could be done

to stem the canals’ decline and it was the work of enlightened

enthusiasts that became central

to saving and restoring many miles of the waterway network. By the

early 1980s, the number of leisure craft topped 20,000 as canals

became increasingly used for leisure purposes.

After much effort by

the Aylesbury Canal Society and other amenity bodies,

the Arm was saved, with leisure boating providing its sustaining force together with walking and fishing.

British Waterways, working with the Local Authority and countryside

bodies, have improved the waterway and its infrastructure to provide a

pleasant back door route into Aylesbury, while much redevelopment

has greatly enhanced Aylesbury Basin’s surroundings.

――――♦――――

Sunday school outing in a pair of Harvey-Taylor

narrow boats, 1931.

Reproduced by kind permission of Miss Catherine Bushell.

――――♦――――

AYLESBURY-BASED CANAL CARRIERS:

THE LANDONS AND A. HARVEY-TAYLOR

THE Aylesbury firm of John Landon & Co. were coal merchants who also

ran a small fleet of horse-drawn narrow boats from the Basin;

according to a trade directory for 1852, they even operated a weekly

“fly-boat” service to London. Taken at face value, this suggests

there remained – after the railway had creamed off most of it –

sufficient high-value trade to justify an express canal service:

“CONVEYANCE BY WATER: To LONDON, William and John Landon’s Fly

Boats, from Aylesbury wharf, Walton St, every Saturday.”

Slater’s Directory, 1852.

By 1869, the Landon’s non-stop fly-boat service had been replaced by

still faster “canal

steamboats” operated by the Grand Junction Canal Carrying

Establishment, John Landon now being their agent:

“WATER CONVEYANCE. London, Birmingham, & all parts of the

kingdom, by canal steamboats; Grand Junction Canal Company; John

Landon, agent. Goods delivered in London at the ‘White Horse,’ Cripplegate,

& at 30 Wharf, City Road basin.”

Kelly’s Directory, 1869.

In 1876, the Grand Junction Carrying Establishment ceased trading. Landons

continued in the business, although no more offering a service to “Birmingham & all

parts of the kingdom”; the firm’s advertisement in Bradshaw’s Canals

and Navigable Rivers (1904) offered merely a service “between London

and Aylesbury and towns en route”. Incoming cargoes would have

supplied the various businesses around the Basin, but other than

condensed milk, the return journey would probably have depended on

anything that could be collected along the way, such as animal feed

and straw from along the Arm and perhaps building aggregates from

the

many pits below Rickmansworth.

Landon’s business was taken over in 1923 by Arthur Harvey-Taylor,

who enlarged the all-wooden fleet by having craft constructed at local boat building

yards (Costins at Berkhamsted, and Bushell Bros. at Gamnel). The

firm dominated the carrying trade on the Aylesbury Arm for some 30

years. Coal was their major business, the firm supplying amongst

other concerns Nestlé’s, the Aylesbury power station, the Aylesbury

Steam Laundry and, further afield, John Dickenson’s various

canal-side factories and that of A. Wander & Co. (makers of

Ovaltine) at Kings Langley, as well as domestic consumers. Large

customers for other goods included Mead’s Flour Mill at Gamnel Wharf

and Garside’s sand quarry at Leighton Buzzard.

|

A pair of

Harvey-Taylor narrow boats in Tring Cutting. Note

the telegraph poles ― selling wayleave to

telecommunications companies provided a useful source of

revenue to canal companies from the 1860s onward.

On this section, a fibre optic highway was installed

during the 1990s. |

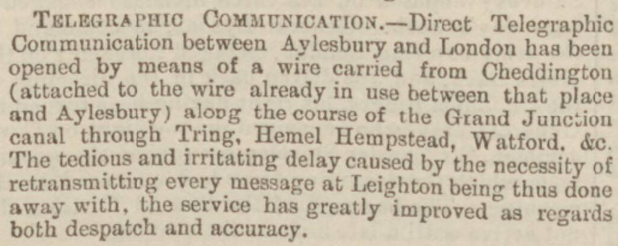

The opening of the direct Aylesbury-London telegraph service, via the GJC.

The

Bucks Herald, 23rd September, 1871.

By the beginning of WWII, the fleet had reached its greatest size,

consisting of nine pairs of boats and two spare butties. A severe

water shortage led to the closure of the Arm in 1942, and it did not

reopen fully until 1947; the closure affected Harvey-Taylor’s

regular traffic into

Aylesbury with road and rail providing alternatives. Some

compensation came from the firm’s long distance carriage of coal

from the Warwickshire coal fields to customers on the main line, such as John

Dickenson and Wander Foods, and others in the London area. But

business tailed off, the fleet gradually dispersed and the firm

ceased trading in 1955.

“Canals, as the predecessors of railways, did good service in

their day. They created internal trade, facilitated the

introduction of foreign merchandise into, and the exportation of

produce from, the interior parts of the country. To

agriculturists they were, and indeed still are, a great boon.

Manure, marl, lime, and all other bulky articles which cannot

possibly bear the great expense of cartage are by them transported

from one district to another at a very light cost; thus poor lands

are enriched, and barren lands brought into cultivation, whilst hay,

corn, and other produce can be carried to distant places at a

comparatively nominal charge.”

Buckinghamshire: A History of Aylesbury, Robert Gibbs (1885).

――――♦――――

In the bleak mid winter - at Lock No. 11 (Puttenham), looking towards Wilston.

The same location in summertime - Puttenham Bridge (Lock No. 11)

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

GRAND UNION CANAL — AYLESBURY ARM.

The Facts About the Waterways,

British Waterways Board, London, 1964.

(App. 5, p.74)

1. The Aylesbury Arm of the Grand Union Canal

descends through 16 narrow locks in its 6¼

miles from Marsworth Junction to its terminus at Aylesbury Basin.

Water supplies derive from the Tring summit supplies on the main

line, of which a large proportion have first to be pumped from the

Tring group of reservoirs into the Tring summit. There are a

number of water sales in Aylesbury. Commercial traffic is

negligible but there is a fair use by pleasure craft. The Arm

is expensive to operate and maintain — not least in terms of lockage

water — and incurs a heavy deficit in relation to its length.

2. In 1964, gross receipts were £2,453, including

£1,350 from water sales and £713 from pleasure craft. Direct

costs totalled £6,828 (£1,092 per mile). The deficit was

£6,404.

3. If the Arm were to be converted to a water

channel, direct costs would fall substantially to about £2,600 (£420

per mile) per annum, and the deficit to about £2,300 per

annum.

4. If the Arm were to be eliminated, the deficit

would be about £2,200 per annum, with an increase to about

£3,500 per annum during the interim period.

5. Clearly the present high level of deficit on this heavily-locked

short length would be greatly reduced by conversion to a water

channel. Moreover, as water sent down the Arm is lost to the

system the balance of advantage might well be in elimination on

general water conservation grounds, even though the interim period

figure is higher than the water channel one. However, a

decision between these alternatives would require careful study of

the alternatives available to the present Aylesbury users.

――――♦――――

|