|

THE MANOR OF DUNSLEY

by

Wendy Austin

The Domesday Book informs us that prior to 1066 when King Edward was

on the throne a priest, Engelric, held the Manor of Tring, but by

the time of the Domesday survey twenty years later, it had been

granted to a Norman nobleman, Count Eustace, Earl of Boulogne. [1]

Like most manors in the country its value had declined due to the

depredations of the Norman invasion; in Tring’s case from £25 to

£20. [2]

The Domesday survey of 1086 informs us that Dunsley [3]

had become a separate manor in the Tring hundred, when seven hides [4]

had been granted to Count Robert of Mortain (half-brother of William

I). Various spellings of the name exist in old records – e.g.

Danesiai or Danesley – probably derived from Dane Law [that part of

England where the laws of the Danes held sway]. The value of

the land was always 12d. A small portion of this land (i.e.

half a part of one third of a hide) was sub-let to a widow, and on

it she kept one ox. A further third was granted to ‘Mainou the

Breton’.

Dunsley was annexed to the Manor of Pendley in the 15th century.

From then onwards its history becomes vague although its name lived

on, for a 1719 survey of the old medieval field system showed both a

Great and Little Dunsley Field.

Some old records state there was a manor house, possibly on or near

the site of the present Dunsley Farm. [5] At

that time, the main highway from Berkhamsted to Aylesbury passed

through the area of Lower Dunsley, resulting in a small community

evolving together with some modest industrial concerns.

――――♦――――

NELL (Eleanor or Elinor)

GWYNN

Mistress of King Charles II – was she ever in Tring? Yes or

no?

Nell Gwynn by Peter Lely c.1675

Local tradition has it that she was here either when she was

pregnant by the king, or at the time typhus was raging in London,

when Charles sent her to Tring under the protection of his finance

minister, Henry Guy, to whom he had granted the Manor of Tring.

Some accounts say she was housed in a property commonly known as

Elinors in the Lower Dunsley area. What we do know is that

the first Lord Rothschild tried very hard when he first acquired the

Tring Park Estate to establish Nell actually did live in the town

for a while, presumably to add to the historic interest of his

newly-acquired property. He employed the best researchers of

the time but they were unable to say categorically that she was.

Nell Gwynn’s Monument, Tring Park

The obelisk in Tring Park known as ‘Nell Gwynn’s monument’ was

erected a hundred years or so after Nell had departed this life.

――――♦――――

THE ROAD THROUGH LOWER DUNSLEY

The original line of the approach road to Tring, from both the

easterly and westerly directions, as well as the actual route

through the town, saw many changes over the centuries.

Consequently, it is confusing and difficult to follow, especially as

some traces of the old sections of road have disappeared.

A glance at a modern-day Ordnance Survey map shows that the most

direct route from Cow Roast to Tring is the line of the age-old

livestock droving road to and from London – now the A42511 – until

the former Rothschild gatehouse, London Lodge, is reached.

At this point the original road continued straight on, entering

Tring Park and passing immediately to the south the Mansion.

On emerging from the Park it continued along Park Street and Park

Road to form a junction with Aylesbury Road at the former

Britannia public house. The road then continued along its

present route past Tring Cemetery and following a straight course to

Aylesbury.

The Britannia at the junction

of Park and Western Roads

The year 1711 saw a major change to this age-old route, one that

meant greatly increased prosperity for the town until, arguably, the

end of World War II, when the tremendous growth of road transport

rendered the narrowness of the High Street inconvenient and unsafe

for large volumes of traffic.

In 1702, the Tring Park estate was acquired by Sir William Gore,

one-time Lord Mayor of London and wealthy banker. On his

death, the estate was inherited by his eldest son, William junior,

who petitioned that the main road be moved from the south to the

north side of his mansion, the story being that he disliked coaches

and wagons rumbling past his dining room windows. Given the

influence of the gentry at that time, it was probably a mere

formality that his application for the change was approved.

Tring Vestry Minutes record:

1710, 11th January. At the house of William Axtell, Rose & Crown,

Tring, an inquisition was held relating to the enclosure by William

Gore, esquire of Tring, of part of the highway from Berkhamsted to

Aylesbury known as Pestle Ditch Way [now Park Road], which

lies on the south part of his garden from Dunsley Lane to a place

called Maidenhead [an old pub]. In substitution he will

provide a road from Dunsley Lane across Tring Market Street [now

Lower High Street] and New Lane to a place in his land called

Gore Gap [now Langdon Street].

The inquisition was conducted before the Sheriff for Hertford, with

seven esquires, three gentlemen, and eight commoners forming the

jury. The verdict was, unsurprisingly, that there would be no

damage to the Queen or to others by the diversion of the highway for

a distance of 92 perches (506 yards).

This new route of the main highway as it reached Tring from the

Berkhamsted direction, still did not follow a line that would be

recognisable today. From the map below, it is possible to

discern that at London Lodge it made its way to the south of

Lower Dunsley – which was located near the site of today’s

Dunsley Place, then a hamlet in its own right – where it passed

between the houses, canvas factory and brewery to emerge opposite

the Robin Hood public house. From then on the route

corresponded with the present High Street until the ‘Gore Gap’ was

reached. Here the road turned up Langdon Street, then along

Pleasant Lane [now King Street] to join Park Road, and then down to

the Aylesbury Road.

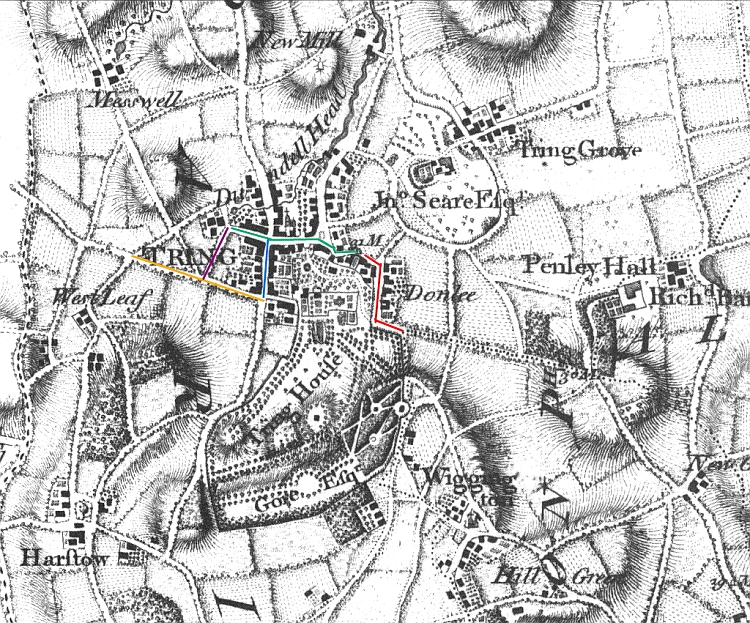

Andrews and Dury’s map of Tring,

1766 (Dunsley is spelled ‘Donlee’).

Shown in Red, the main

road through Dunsley; Green,

Tring High St; Blue,

Akeman St.;

Purple, Langdon St. (the

Gore Gap); Orange, Park

Rd.

At some time during the early-1820s, at the instigation of the

Sparrows Herne turnpike trust, [6] a new section

of road was also built between London Lodge and Lower Dunsley, the

work being undertaken by James Bull of Tring. [7]

This necessitated some road widening, the demolition of dwellings

and payment of compensation. William Kay, then Lord of the

Manor, was awarded £248.15.0d. compensation compared with the £4

17s.0d. to the four cottagers who were obliged to quit their homes.

From an OS map of 1879, showing the new route of the

main road highlighted in red, and the

truncated remains of the former road through Dunsley

in blue.

From the following entries in Tring Vestry Minutes and the Bucks

Herald it seems that the remaining section of old road through

Dunsley hamlet was not closed finally until 1883, a date that

roughly corresponds to that when Lord Rothschild decided to

incorporate the whole area into his private gardens.

“1883. The old road at a point on the south side of the High

Street, adjoining the Manor Brewery, and the Canvas Factory, is to

be closed. This refers to Lower Dunsley.

“1883, 25th August – Notice has been issued

notifying the intended closing in the usual way of the now useless

road at the southern end of Tring . . . . “

Eventually all the buildings in the hamlet of Lower Dunsley were

demolished, and those displaced by the stopping up of the old road

and the landscaping of his lordship’s new gardens were found

replacement housing. (It is likely that the cottagers affected by

these changes were found improved accommodation, for it was always

Rothschild’s policy to treat tenants or, in fact, any townsfolk

unfairly.)

――――♦――――

INDUSTRY IN LOWER DUNSLEY

–

CANVAS WEAVING

Canvas, a durable plain-woven cloth, was traditionally made from

hemp (cannabis sativa) an undemanding plant with a long

fibrous stem and six times as strong as cotton. The fibres,

from 3ft. to 15ft. in length, commonly called bast, grow on

the outside of the woody interior of the plant’s stalk, and under

the outermost part of the bark.

There does not appear to be a tradition of hemp growing in the Tring

area, [8] and no one can say exactly why

canvas weaving started as a small industry in various locations in

the town. Writing in the 1890s, Tring local historian Arthur

Macdonald states that:

“The canvas industry is said to have been introduced [to

Tring] by a colony of Flemings who settled here. Some of their

names remain, as Delderfield or Delderfeldt (‘Darofel’), and Wilkins

(‘Wilquin’)”.

Those Calvanists who migrated to England from the Continent to

escape persecution on account of their faith brought with them many

craft skills. They were often master weavers or journeymen

specializing in various branches of the textile industry, mainly

silk, although some Huguenots practiced the craft of canvas

sail-making in England long before then. However, no firm

records have been discovered of their descendants arriving in Tring.

The first documented evidence of canvas weaving in Tring comes from

entries in the Militia Lists from the middle to the end of the 18th

century, which record men working as rope-makers, as well as one

flax man and one hemp dresser. Pigot’s trade

directories from 1825 to 1839 list four proprietors of weaving

shops, and Arthur Macdonald describes the first of these as follows:

“Entering the town from the east, the first building on the left

is the pretty pair of cottages [Lower Dunsley Cottages] built

by Lord Rothschild on the site of an old canvas weaving shop, then

owned and occupied by Mr John Burgess, and before him by Daniel and

Harding Olney. The Olneys were a family of some position in

the town, being the principal canvas manufacturers and possessing

several properties. William Olney had weaving shops in Akeman

St., which he converted into the Akeman Brewery.”

By ‘some position in the town’ Arthur Macdonald presumably refers to

the Olney family’s high standing at the New Mill Baptist chapel, at

a time when Non-Conformity was at its height. Daniel Olney

senior was Deacon at that church, and his brother, Thomas, also had

a high profile in the Baptist movement.

John Burgess, advertising his trade as “canvas manufacturer of

open canvas for ladies needlework, gunpowder canvas, cheese cloths

etc.” carried on weaving in the premises at Dunsley until it was

shut down in 1883. It was demolished two years later, along

with other nearby properties, to make way for the erection of the

attractive Lower Dunsley Cottages (now Grade II Listed) opposite the

Robin Hood pub.

An account in the Bucks Herald of 26th December 1885 states:

“At Dunsley, where formerly was a lot of houses and a canvas

manufactory, with the residence of Mr Burgess, a great change has

been effected by Lord Rothschild.

The whole valley has been filled up with earth brought from Albert

Street and Western Road, where the foundation of a new General

Baptist Chapel is being dug. Instead of the familiar factory

before-mentioned, a handsome and substantial house [sic]

meets the eye, on the top being an exalted vane and six or eight

twisted chimneys in which Norris’s ornamental bricks are used.

This improvement has afforded employment to a large number of

people.”

Four of the eight ‘twisted

chimneys’ atop Dunsley Cottages.

As far as can be ascertained, the development above always comprised

two separate cottages, so in his description the Bucks Herald’s

reporter was in error. In any case, it appears that during the

1880s substantial changes were being made to the general townscape

of Tring, many of which remain and are familiar to us today.

――――♦――――

INDUSTRY IN LOWER DUNSLEY

–

THE MANOR BREWERY

At sometime before the mid-1800s, Seabrook Liddington leased land

from the Tring Park Estate on which he built the Manor Brewery and a

maltings sited in New Mill. The premises consisted of the

brewery with a side entrance to an off-licence known as ‘The Hole in

the Wall’ (said to be older than the brewery). When Seabrook

retired he built a new house at New Mill and continued his business

of malting. A highly respected member of the community,

Seabrook became Tring’s oldest inhabitant, dying at the age of 94,

having been born in Tring in 1808.

James Liddington, a distant relative and former landlord of The

Victoria public house in Frogmore Street, took over the Manor

Brewery. He was succeeded by Mrs. Rebecca Liddington.

The

approach to Tring from Station Road, c.before 1896 –

The Manor

Brewery with chimney is dimly discernible on the left

In the Tring Park Estate auction sale particulars of 1872, the

brewery was offered for sale freehold and comprised:

“a substantial brick building of three storeys, with a

brick-built and slated four-bedroomed house, two parlours, two-stall

stable, several piggeries, wash-house, office, and two adjoining

cottages”.

The rental was £48 per annum. When the Manor Brewery fell into

disuse it, together with other premises in the Lower High Street

including The Green Man public house, was finally demolished

in 1896, and the high curved wall we know today was erected around

what is now the area of the Memorial Garden.

――――♦――――

TRING PARK GARDENS –

THE ROTHSCHILDS

Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild,

1st Baron Rothschild (1840-1915)

Unlike many of his relatives, the first Lord Rothschild [9] was not a

passionate gardener, and practical matters relating to farming and

agriculture held far more appeal for him.

However, in the 1880s when Tring Park mansion was remodelled,

substantial alterations to the gardens were also undertaken.

As the new landscape design matured, Nathaniel Rothschild did become

interested and he became knowledgeable about the names and qualities

of shrubs. His wife is known not to have favoured too much

formal planting and at the south front of the house, except for a

few flowerbeds (sometimes displaying the Rothschild racing colours

of blue and gold), the landscaping remained soft. The lawn was

extended and a new ha-ha constructed to allow an uninterrupted view

to the wooded escarpment on the far side of the park.

Tring Park Mansion following

the Rothschild alterations

The area known as ‘the pleasure gardens’ to the west and north of

the house was extensively remodelled and replanted. A

description written at the time records that they featured a summer

house and an Italian garden and fountain. A sunken path, lined

with flint, led to an under-pass which still survives. This

ran beneath the drive leading to the stables, and gave access to a

winter tennis court; a topiary garden clipped into the shapes of

tables, chairs, and chess pieces; a Dutch garden; an Elizabethan

garden; and a number of other areas.

An account in the gardening press at the time says:

“Each of these little gardens is complete in itself; once

entered, the whole comes under the eye in an instant, but nothing is

seen of the gardens beyond, for each of these separate designs is

encircled by an irregular bank, planted with rare Conifers and

shrubs, faced with flowering plants, Lilies, and Roses, and in all

cases with as many annual or perennial sweet-scented plants as

possible”.

The account reads on to wax lyrical about all the chosen bedding,

including purple Clematis, Begonias, Violas mixed with silver

Pelargoniums, Cannas, Marguerites, white Nicotiana, and Sweet-peas.

That same year, a correspondent from The Gardeners’ Chronicle

visited Tring Park, and in his article he comments with

surprise on the modest entrance and approach to the estate.

But once beyond the stables area, matters obviously lived up to his

expectation of a home appropriate for the richest man in the British

Empire. The following extracts give a good description of the

gardens at that date:

“A broad new carriage drive leads to where a grand entrance to

the house is evidently meditated, and on the right of this approach

is a bank of evergreens. It was planted only eighteen months

since with large shrubs of Yew, Bay, Box, and Aucuba japonica

. . . . Passing round the house you will find a lawn, much

enlarged recently, and clipped about by a very unlevel park,

beautifully planted with clumps of Limes, animated by deer and

shorthorns, and enclosed by masses of encircling Beech woods on the

high ground which bounds the view.

. . . . Among the proofs of outlay, as well as of excellent

taste, are the numerous costly shrubs around the house, including

the bushes of Golden Yews grown from cuttings, as well as the much

rarer seedlings. I dare say thousands have been expended in

shrubs lately . . . . Numbers give only a mechanical idea of works of

planting like those which Mr Hill (the head gardener) with his men

and long hose has brought to such a successful issue; but it may

please nurserymen, and make their mouths water, to repeat that 500

Golden Yews, costing a great sum, have been planted here, and 10,000

bulbs of Gladioli set in the shrubberies to enliven them. . . . . I can only say that it (the garden) is filled with costly “things”,

and in standing before the largest Japanese specimen, which is many

times repeated in smaller sizes, one cannot help counting the cost.

It is the beautiful Retinospora obtusa nana aurea and is

worth seven guineas. The double Spanish Gorse is used as an

edging of this grand clump of shrubs, and I observed several

specimens of weeping Yew on stems one foot or more high, and then

spreading horizontally. . . .

The kitchen gardens are on the roadside near the town, and will soon

be entirely shut in by walls, and enlarged from three to six acres.

The glasshouses are numerous, and the management unsurpassed.

Five houses are devoted to Orchids, and two entirely to Carnations,

one of them to the favourite Malmaison. The foliage

plants, Crotons, Caladiums, Alocasias, Dracænas and others were

superb, and the varieties of Begonia and Coleus looked charmingly

bright. I believe that a London firm decorates the London

house so far as pot plants are concerned; but the cut flowers are

sent from Tring, and two houses of Adiantum ceneatum are

required for the growth of Fern foliage by the bushel.

There are five vineries where the Muscat of Alexandria Grapes, of

five years’ growth, are as good as can be, and the adjoining Black

Hamburgs too having this year the largest berries yet produced here.

In the Fig-house the first crop was just over, and the second coming

in. . . . The Orchard-house is simple and comparatively

inexpensive. It consists of 135 yards of wall, enclosed by

glass, having hot-water pipes to keep the temperature above

freezing, and making all the wall fruit – Apricots, Peaches, Pears,

and Plums – perfectly secure.”

The article goes on at great length in the same vein, and also makes

mention of ‘the cottage’, the home of the unmarried gardeners.

This was replaced in 1905 by The Bothy, a fine new building

where the boys were well-cared for by a housekeeper. (The Bothy

later became the premises of Williaam [sic] Cox, a firm

manufacturing plastic sheeting, until finally demolished in the

1990s to make way for Tesco’s supermarket.)

Death duties and the effect of two devastating world wars had taken

their toll, and by the time of Lord Rothschild’s grandson, matters

had begun to change. A description written by Bob Poland,

recently appointed as Greenhouse Foreman at Tring Park, gives

some idea of how things were.

The Bothy c.1910, now the site

of a Tesco supermarket

Arriving at his new job one Saturday evening in November 1934, he

was stunned when the head gardener called for him at The Bothy

at

9 a.m. the next morning. He was instructed to start cutting

fresh flowers ready to be sent to the Rothschild houses in London

and Cambridge. On enquiring when they were wanted, he was told

to leave them in water overnight, but to be up at 3 a.m. the

following day “as the van calls at 6.20 a.m.” and only two

men would be available to help.

Bob Poland’s new empire was larger than anything he had experienced

before, and he describes the glasshouses with 18 miles of piping and

boilers consuming 30 tons of coke each week, all shovelled by hand.

These glasshouses were not as they had been in their heyday, and Bob

recounts they “were in an awful state with every known greenhouse

pest - thrips, mealy bug, red spider, and millions of ants”.

In an attempt to rid the gardens of pests, he persuaded the head

gardener to pay the men so much each for the tails of rats, mice,

moles, and for Queen wasps.

Once the major problems had been dealt with, Bob came to enjoy his

job for his duties were varied. When the family was in

residence, his responsibilities included supplying and arranging all

the floral decorations in the house. Busying himself in the

flower room on the ground floor of the mansion, Bob provided the

sumptuous arrangements that were changed twice a week, and those in

the dining room once a day, or sometimes twice. At the festive

season a huge 30 ft. Christmas tree stood in the centre of the

staircase well, and hundreds of flowering pot plants were used to

decorate wherever space permitted.

Not much time or effort could be spared for gardening during WWII

and the grounds of Tring Park became neglected and overgrown.

During the conflict the staff from the Rothschild bank in the City

of London moved into the house, and the stables were used by the

Home Guard, the ARP, and the Red Cross. Shortly before the

war, the 3rd Lord Rothschild had offered Tring Park house, grounds,

park, and woodlands as a gift to the British Museum of Natural

History. The committee appointed to consider this did not

accept it. The mansion then became the Arts Educational

School; part of the ‘pleasure gardens’ was later dedicated as the

Memorial Garden; The Bothy was used to house engineering

staff from the Royal Mint Refinery in Brook Street; and later the

route of the A41 by-pass sliced through the park. Like many

similar estates all over the country, the golden days were over and

nothing was ever the same again.

The remaining areas of the kitchen gardens fronting the main road

were developed as two separate closes of modern houses, the one

nearest the town named Dunsley Place, the original high walls having

been preserved are now listed. A back gate from Dunsley Place

leads through the Memorial Garden making a pleasant short-cut into

the centre of the town.

――――♦――――

DUNSLEY FARM

When the Rothschilds acquired the Tring Park Estate at auction in

1872, it included Dunsley Farm. At an auction of the Estate in

1820, the farm then comprised 240 acres (part in Wigginton Parish).

Held by various tenants since, the present farmhouse building was

erected in 1881, at a cost of £300.

Plaque

on Dunsley farmhouse depicting a section of the Rothschild

coat-of-arms

and motto

– Industria, Integritas, Concordia

In 1919 the Hon. Charles Rothschild of Tring Park,

anxious to help returning servicemen to settle on the land, sold 180

acres of Dunsley Farm to Herts County Council for use under the

Government ‘Homes for Heroes’ scheme. This included a 2-acre

area of farmland in Cow Lane for lease as a small farm, and also an

orchard where a wooden bungalow was erected. Later, further

acreage belonging to the farm was sold, providing 10 building plots

in Station Road and Cow Lane. Nowadays, the area immediately

around the farmhouse includes a farm shop, a café, the operating

premises of Tring Brewery, and a duck pond.

――――♦――――

TRING PARK - HEAD

GARDENERS

For many years the Garden House, a pretty Regency house with

Gothic-style windows, was the home of successive head gardeners on

the Tring Park estate. It enjoyed an open aspect and

was not shielded from the London Road until much later, when high

brick walls were built to enclose the entire kitchen garden.

During the early Victorian period the various occupants included

William Brown, William Ivory, and James Smith, who also ran a seed

merchant’s shop in the High Street. The privilege of living in

the Garden House did not come easily as, on any large country

estate, the head gardener was a figure of immense importance, whose

knowledge of gardening matters, control of men, and organisational

skills were expected to be all-embracing. But in 1877 this did

not prevent the Rothschild family appointing to the post a youthful

27-year old Gloucestershire man, Edwin Hill.

The garden House, Dunsley,

c.1910

For the next 27 years Edwin re-organised and maintained the grounds

around the Mansion. As his experience grew, he became a

well-respected member of his profession and was recognised as such

by being elected to the committee of the Royal Horticultural

Society. He also laid out the gardens of the newly-built

Louisa Cottages in Park Road, and those of the Isolation

Hospital on the road to Little Tring. He acted as Secretary of

the Cottage Garden Society, an organisation close to Lady

Rothschild’s heart, and was expected to arrange the athletic sports

on show day. Edwin died at the early age of 54 and his

obituary appeared in the Gardeners’ Chronicle.

Louisa Cottages

Edwin was succeeded by his assistant of eight years, Arthur Dye, who

came to Tring Park with the very best credentials. Born

in Norfolk, he started his career in the Royal Gardens at

Sandringham, later moving to the Royal Lodge at Windsor.

When he arrived to take up his position at Tring, Arthur and his

wife were tenants in one of the Louisa Cottages, but

following Edwin Hill’s untimely death they moved to the Garden

House within the walls of the kitchen garden. Living in

this splendid house had, at times, certain disadvantages. On

spring nights when the apple-blossom was in flower, a bell sometimes

sounded a warning that the outside temperature had fallen below

freezing point: Arthur then had to leave his warm bed to ensure that

fires were lit in the orchards. (Propped up in his bedroom was

a shotgun, which he used to dispatch any unwelcome Glis Glis who

trespassed into the loft space.)

Arthur Dye and family in the

garden of the Garden House

His new responsibilities included the welfare of the unmarried

gardeners living at The Bothy. Liaison with other

senior staff members such as the chef and butler were also part of

the job. One very special task each year was a visit to

Buckingham Palace, bearing Lord Rothschild’s gift of flowers to

decorate Queen Mary’s breakfast table. Arthur remained head

gardener for forty years, and on his retirement moved to a

Rothschild property, Woodlands, in Chesham Road, Wigginton.

There he enjoyed 25 years tending his own large garden where he

waged a constant war against Wigginton’s rabbit population.

In the summer months it was the practice for owners of large houses

to open their gardens to the less privileged local folk of the

district. These events were greeted with mixed feelings by

head gardeners. Their natural pride and pleasure in

compliments were weighed against possible hazards to their precious

plants. At Tring Park during the annual Agricultural

and Flower Shows, ‘Freedom of the Park Day’ meant all could wander

around the grounds and gardens, but some very necessary preparatory

work had to be done. The park was home to a variety of exotic

creatures belonging to Walter, eccentric zoologist son of Lord

Rothschild. Throughout the year kangaroos, emus, and other

animals roamed freely, but of course had to be kept under control on

the great day. Beforehand, an army of gardeners’ boys were

deployed to clean up the park, in a thoughtful attempt to preserve

the Sunday-best boots and shoes of the visitors.

‘Freedom of the Park Day,

c.1910’

――――♦――――

TRING MEMORIAL GARDEN

(on the site of Lower Dunsley)

|

|

|

Tring Memorial Garden |

The area covered by the present garden had been created in the

1890s when several properties in the Lower High Street were

demolished. These included Rose Cottage, once the

home of a Tring solicitor, and the Green Man, an

early-Victorian public house erected by the proprietor of Tring

Brewery. A large irregular-shaped lake was dug out and planted

with different species of water-lily, and the whole surrounded by

abundant picturesque planting. The entire garden was hidden

from view from the main road by a high brick wall and a thick screen

of trees and shrubs.

In March 1947 a questionnaire was

circulated in the town to canvass opinion about how best to honour

Tring’s war dead. The outcome was 107 votes for a sports

centre, 67 for improvements to the Victoria Hall, and 180 for a

public garden with a paddling pool. Possibly the absence of a

definite project led to a disappointing and rather shameful response

to the accompanying appeal for funds. The Council decided that

the paltry sum collected of £20 6s.2d. could only finance the

addition of names of the fallen to be added to the existing

memorial in front of the parish church.

Disquiet over

this outcome led Tring to wake up, and three months later a public

meeting was held and a committee of twelve members elected to launch

a firm appeal with the target of raising £5,000. The stated

objective of the scheme was to provide a fitting memorial (other

than a monument) to those who had fallen in World War II, as well as

a thanksgiving for those who had returned home safely.

The Green Man

Considerable interest was taken in this new appeal fund, and a

well-known Tring shopkeeper came up with a novel idea to start the

ball rolling. He suggested that businessmen should give £1 for

every year they had been trading in the town. On this basis,

his own welcome contribution amounted to £25, and others soon

followed his example. The committee again invited suggestions

as to the form the memorial should take. Among the ideas put

forward was a swimming pool, but the Council considered the running

costs would be too great.

Eventually, and after much debate, it was decided to create a

Garden of Remembrance in the old water garden of the Tring Park

estate. In the years after World War II the lake and its

surroundings presented a sorry sight. For years, the area had

suffered almost total neglect and had become overgrown, dark, and

depressing. Any idea that the water garden could revert to its

former glory was clearly impossible, as it was realised that the

number of gardeners required for its maintenance would never again

be available in the modern world. Instead it was thought that

clearance of the area, resurfacing the lake bed, and some simple

replanting would offer an acceptable and pleasing aspect as a public

open space.

Even so, nothing happened quickly. Three

years passed before the legal process of transferring the site to

Council ownership was settled, and thereafter work proceeded slowly.

It was another three years - in June 1953 - before the garden was

formally opened, an event planned to coincide with the Coronation of

Elizabeth II. Over 200 people were present at the unveiling

ceremony, the dedication service being conducted by the Reverend

Lowdell, Vicar of Tring.

The garden was enjoyed for some

years before it fell victim to mindless vandalism, but when Mrs

Westron, widow of Tring nurseryman Frank Westron, died in 1971 she

bequeathed £50 to be spent on the Memorial Garden. The Council

then decided to use this sum towards repairing the damage.

Today the lake (fed by natural springs rising in Tring Park)

looks very different from how it was in the time of the Rothschilds.

All the vegetation surrounding the perimeter has been cleared,

allowing an uninterrupted view of the magnificent Wellingtonia

that towers over the northern end. In recent years some

alterations have taken place, following criticism that the approach

to the gardens was dark and uninviting.

The Council then

organised contractors to thin trees and shrubs bordering the

entrance pathway, allowing more daylight to provide a welcoming

aspect. In 2001 the lake had to be drained and the fish

evacuated when it was necessary to investigate the cause of serious

water seepage. A bad crack in the concrete base was

discovered, repaired, and four carp returned to the water following

their sojourn at a nearby fish farm.

Members of the Tring branch of the British Legion attended

a reopening ceremony, and presented a plaque listing the names of

those men from the town killed in World War II. This is

mounted on the brick gate-pillar at the entrance. Later, in

2018 in a ceremony to commemorate the end of WWI, a second plaque

was mounted on the other side of the gate to remember all those from

the town who served in that conflict.

It is pleasing to record that Tring’s Memorial Garden is well

used every day of the week and in most weathers, thus repaying the

work of volunteers (Friends of Tring Memorial Garden) as well as the

maintenance and planting services provided by Dacorum Council.

Folk of all ages enjoy this space, whether just sitting on a seat in

the sunshine or, in the case of children, dashing round the

footpaths on scooters. Dog walkers are also in evidence, and

most are considerate in clearing up the inevitable mess. In

recent years, small notice boards have been sited at intervals

around the lake offering brief explanations of various aspects of

the two wars, or commemorating individuals who fell.

――――♦――――

NOTES

1. THE MANOR OF TRING:

Matilda, daughter of Count

Eustace of Boulogne, inherited the manor from her father. She

later married Stephen of Blois, a grandson of William the Conqueror

who later became King Stephen of England. In 1148 King Stephen

and Queen Matilda founded the Cluniac order of St Saviour at

Faversham in Kent, and they presented the Manor of Tring to the

abbey. It was later exchanged for other properties with the

Archbishop of Canterbury. When Henry VIII dissolved the

monasteries during the 1530s, the manor was confiscated and became

Crown property remaining in Royal hands until the reign of Charles

I. In 1650 Charles I arranged to have the manor transferred to

his wife, Queen Henrietta Maria, only for it to be confiscated by

Parliamentary Forces during the English Civil War. In 1660 the

manor returned to royal ownership under Charles II who, in 1680,

gave it to his finance minister Sir Henry Guy. It is believed

that Guy used his position to subsidise the construction of a new

manor house – but not that existing today – to a design by Sir

Christopher Wren.

2. Domesday valuations present a problem - exactly what

value were they? Do they represent the manor’s capital value

(what it might fetch at sale)? Or are they annual rents paid

to the lord by his tenants? Or are they the total income

including the sale of produce of the lord from his manor? Or

are they the tax levied on the lord of the manor? It seems

most likely that they were annual payments, probably the annual

rents paid to the lord by his tenants.

3. Tring once possessed four hamlets: Little Tring

(the location of the Grand Union Canal pumping station); Dunsley,

which bordered the Tring Park Estate; Hastoe, to the south; and

Tring Grove, to the east. Little Tring and Hastoe survive as

satellites of the town, while Dunsley and Tring Grove have been

absorbed into it.

4. Hide – a land-holding that was

considered sufficient to support a family.

5. In referring to the hamlet of Dunsley, Volume 2

of A History of the County of Hertford (1908) states that “The

manor house has quite gone, and was replaced by a farmhouse about

thirty years ago.” The farmhouse referred to was built in

1881.

6. The

Sparrows Herne Turnpike Road from London to Aylesbury was an

18th-century English toll road. Its route was approximately that of

the Edgware Road, then through Watford, Kings Langley, Apsley, the

Boxmoor area of Hemel Hempstead, Berkhamsted and Tring to Aylesbury,

much of which is now covered by the A4251. North of Aylesbury

it linked in with other turnpikes forming a route to Birmingham.

7. In his notes on the Town’s history, former

local historian Arthur MacDonald left a brief mention of James Bull.

Besides building the turnpike bypass around Dunsley, Bull

superintended other of the Town’s road construction projects:

“Bank Alley [off Tring High Street] . . . . was formerly

the emporium of Mr Bull, saddler, a leading man in the place and

very wise in road making. He superintended the formation of

the cutting embankment at Beggar Bush Hill [now Tring Hill]

on the Aylesbury Road, also the making of the new Station Road in

1838, when he and Mr William Brown were Highway Surveyors. He

held the post of Parish Constable at the same time, with great

effect upon unruly railway navvies.”

8. At New Ground on the A4251, a ‘Hemp Lane’

connects the main road to Wigginton village.

9. Nathaniel Mayer Rothschild, 1st Baron

Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild, GCVO, PC (8th November 1840–31st

March 1915) was a British Jewish banker and politician from the

wealthy international Rothschild family. Rothschild worked as

a partner in the London branch of the family bank, N M Rothschild &

Sons, and became head of the bank after his father's death in 1879.

During his tenure, he also maintained its pre-eminent position in

private venture finance and in issuing loans to the governments of

the US, Russia and Austria.

――――♦―――― |