|

Tring’s Lost Settlements

by

Sue Gordon

A formal study of abandoned settlements began in the early 1950s and

in 1971 Deserted Medieval Villages by Maurice

Beresford and John Hurst of the University of Hull was published,

which contained a list of over 2,200 deserted sites throughout

Britain.

Three from the area north west of Tring were listed: Tiscot, Betlow

and Pendley. A later publication, The Deserted Medieval

Villages of Hertfordshire by K. Rutherford Davis, added Bure,

Gubblecote and Miswell.

More recently the

Hertfordshire Heritage Environment Record has

classified Aldwick as a deserted settlement and Puttenham as a

contracted village.

Of these eight small hamlets, six were mentioned in the

Domesday

survey of 1086. Miswell was the largest with nineteen

households and woodland for 500 pigs. Bure was very small with

just four households. For comparison, Tring was recorded as

having sixty-two households and woodland for 1000 pigs.

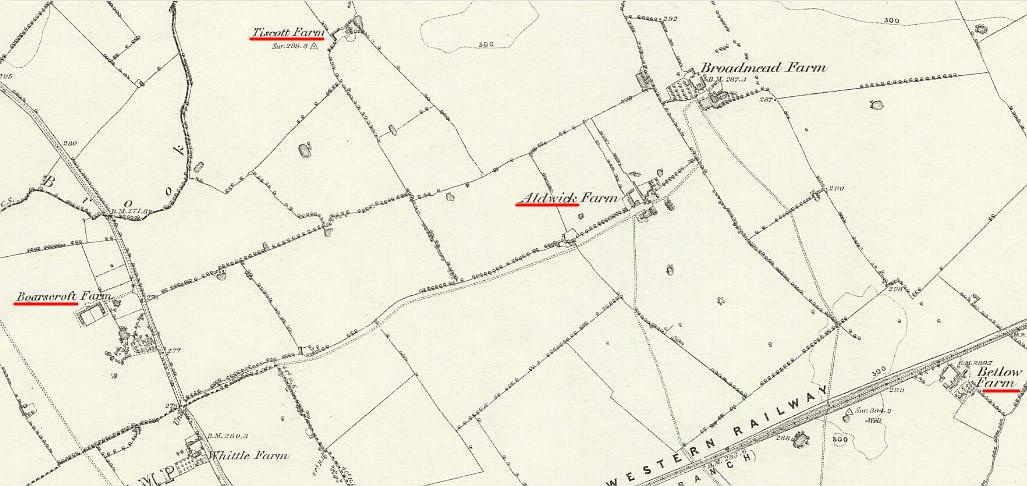

Bure, Tiscot, Betlow and Aldwick were close to the present-day

border with Buckinghamshire in the Boarscroft Vale (geologically

part of the Aylesbury Vale). |

Above and below: settlement sites, from left to right: Boarscroft; Tiscott;

Aldwick; Betlow.

Both maps reproduced with the kind permission of the

National Library of Scotland

Bure, in the vicinity of today’s Boarscroft Farm, was probably never

more than a smallholding, although it is surrounded by ridge and

furrow. ‘Ridge and furrow’ is the term used for the regular

pattern of gently curving ridges that can still be seen in some

fields and which are the remnants of medieval ploughing.

Bure was occupied by Andrew atte Boure in the early 14th century,

but by the mid 16th century had acquired the name Bowrscrofte

meaning a smallholding attached to a bower.

Tiscot was larger than Bure in 1086, with twelve households and a

mill. A 1334 tax assessment indicates that Tiscot was probably

in decline even before the Black Death arrived in 1348. The

settlement was occupied in the mid 16th century but was still

declining. A chapel existed for a further century but was then

demolished. By the 19th century all that remained was a single

farmhouse which disappeared in the early years of the 20th century.

House platforms and a possible road can still be seen from the air

and the site is a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

Although Betlow is not mentioned in the Domesday Book it was

probably occupied in the Saxon period. The name may

mean Beta’s (burial) mound or hill and there is a possible Saxon

burial mound north of Betlow Farm. Betlow farmhouse was built

in the 15th century, but may not have been the original manor house.

Aldwick was called Aldwwyke, meaning old dairy farm, in the 13th

century. Aerial photographs show a sunken way surrounded by

house platforms south of the present Aldwick Farm and adjacent to an

area of ridge and furrow.

Closer to Tring is Miswell which had nineteen households in 1086.

This equates to a population of around 100 adults and yet there is

nothing identifiable on the ground. All that can be seen from

the air are what are probably field boundaries and a pond.

This was once thought to be a moat but is now believed to be a

wildfowl ‘flight-pond’ associated with a post medieval farmstead.

The lists of Deserted Medieval Villages also include Puttenham,

which had twelve households and two mills in 1086, and Gubblecote,

five households and a mill, although neither of these settlements

was abandoned completely. Both had a manor house that no

longer exists.

St Mary’s

parish church, Puttenham.

Puttenham’s St Mary’s parish church dates in part to the early 14th

century or earlier. Earthworks north of the church were

surveyed in the 1980s and revealed two probable house platforms.

Ditches enclose the area which is now a Scheduled Ancient Monument.

An L-shaped pond in the grounds of the Rectory may be the remains of

a moat.

Puttenham and Gubblecote.

Gubblecote was called Bublecote or Cobbelcote and means ‘Cubbel’s

cottages.’ Cropmarks indicate possible house plots lining a

trackway which runs towards a moated site. The moat was

investigated in the 1970s and is perhaps the site of the manor

house.

Why were these sites abandoned or reduced in size? The seeds

of their failure were probably sown many centuries before the Black

Death arrived in 1348.

In Hertfordshire during the Saxon period the population grew and

woodlands were felled for agriculture. In Europe and Britain,

rising population and falling grain yields in the early 13th century

resulted in land available for cultivation becoming scarce: old

fields were exhausted and pasture was ploughed up for grain crops.

This had the knock-on effect of a shortage of manure, which in turn

reduced grain yields still further. Prices rose and there was

widespread starvation.

In the years from 1272 to 1320 there were unusual storms and floods.

But there was also reduced rainfall until 1300 followed by

persistently wet weather and bad harvests. The increase in

rainfall would have adversely affected the small settlements in the

Boarscroft Vale where the soil is impermeable and causes winter

flooding. As farming became uneconomic the inhabitants would

have migrated to nearby larger communities.

By the middle of the 18th century, and most probably long before,

the hamlets of Bure, Tiscot, Betlow and Aldwick had disappeared and

there remained only a single farm in the vicinity of each. |

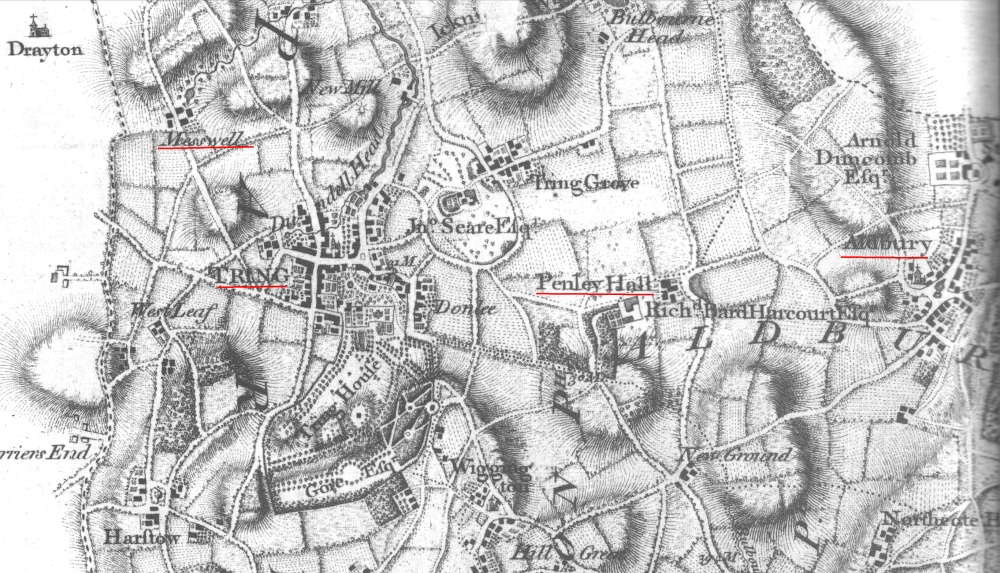

Dury & Andrew’s map of Tring (1766). Miswell top left;

Pendley, centre.

The possible reasons for Miswell’s abandonment are not so clear.

Unlike the settlements further north, Miswell is not on the wet

marshy ground of the Boarscroft Vale although it does have a

plentiful supply of water in the form of a spring.

Given its larger size in 1086 and its proximity to the Ickneild way

you would have expected Miswell to have survived. Perhaps it

was too close to the successful town of Tring and when times got

tough its inhabitants moved to the larger community with its market.

|

|

|

Pendley Manor |

The disappearance of the village

of Pendley had other causes. In 1086 Pendley had seven

households – so it was not large. By the early 15th century

the settlement appears to have grown and was part in the parish of

Tring and part in Albury. In 1440 the Lord of the Manor of

Pendley, Sir Robert Whittingham, was granted hunting rights by Henry

VI. The grant allowed the enclosure of 200 acres as a park.

In the process cottages and hedgerows were removed and arable fields

turned over to pasture resulting in the loss of common grazing

rights.

A later commentator, writing in 1506, stated that before the

emparkment, Pendley was ‘a great town’ supporting ‘more than

thirteen ploughs and handicraft men such as tailors, shoemakers and

cardmakers’. Allowing for exaggeration, Pendley was probably a

sizable village at the time of its destruction.

Whittingham’s family sold the manor in the early 17th century and

the medieval park is not shown on a map of 1676. The manor

house that Whittingham built, probably in the 16th century, was at

the west end of Pendley village. Today only slight earthworks,

which could possibly be signs of the village, are visible to the

east of Pendley Manor. |

――――♦――――

|