|

INTRODUCTION

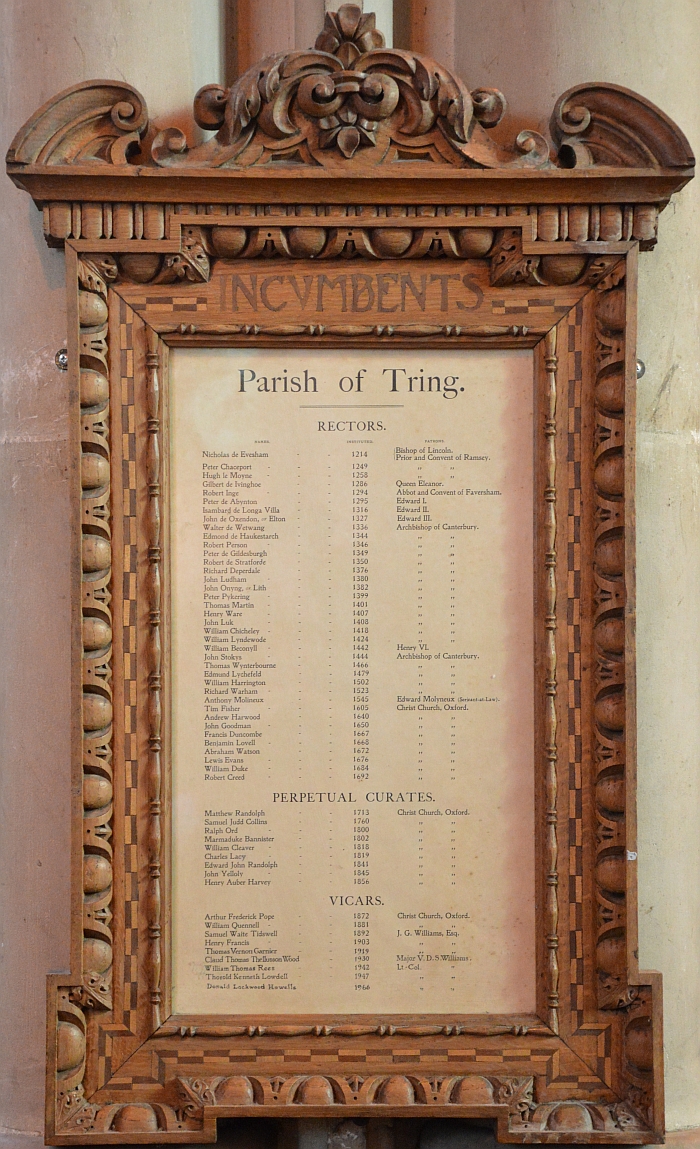

Whilst browsing some old editions of the Tring Parish

Magazine, three articles (dating from June and September 1939,

and August 1941) caught my eye. They related to the ornately carved wooden frame that hangs from a column beside the book table in the

Parish Church, and each drew attention to some interesting aspect of

local history. The frame in question contains a list of the previous Incumbents

dating back to the year 1214, when Nicholas

de Evesham was appointed Rector of Tring. His name is followed by a

further 54 clergyman down to the year 1966, when space became exhausted – later incumbents are recorded in a less

impressive frame suspended on the opposite side of the column.

The first two articles told of the incumbent who

had held

the post of Rector for the greatest length of time, this being

Anthony Molyneaux who was Rector between 1545 and 1605.

Whether he spent much of that time if, indeed, any, at Tring, is

open to question, for Rectors often hired a substitute to perform

their pastoral functions in the parish. The third article identified the

(perhaps) most prominent incumbent, for William Lyndwood,

besides being Rector of Tring, served as a diplomat, was an authoritative writer on

canon law, and ended his days as Bishop of Saint David’s.

Less impressive, to

modern eyes at least, was Lyndwood’s heavy involvement in proceedings

against the heretical Lollards (forerunners of Protestantism); in

that age it seems that even a man of learning did not shrink from burning those of his

fellow-men who publically espoused unorthodox views on religion.

The author of the article on Lyndwood was, I suspect, Sir Harry

Bevir Vaisey (1877–1965), a senior judge in the Chancery Division of

the High Court and a member of the distinguished Vaisey family of Tring.

This from the Tring Parish Magazine for February 1939:

Mr. H. B.

Vaisey, K.C., D.C.L.

We would like to congratulate Mr. Vaisey upon the Degree of Doctor

of Civil Law which was conferred upon him by the Archbishop of

Canterbury at Lambeth Palace on the 31st January for his services to

the Church.

The privilege of conferring this Degree was formerly a prerogative

of the Pope, but in the reign of King Henry VIII this was

transferred to the Archbishop of Canterbury, under an Act of

Parliament. The recipient is entitled to wear the hood and

gown of the corresponding degree in the University of which the

Archbishop is himself a member. Very few D.C.L. Degrees are

conferred by the Archbishop, and we believe that there are only two

other living persons who now hold it, and it ranks in precedence of

all other Degrees of Doctor “in the faculty of Laws.”

Mr Vaisey is Vicar General of the Province of York, Chancellor of

the Dioceses of York, Carlisle, Derby and Wakefield. He was a Member

of the Archbishop’s Commission on Church and State, and is at

present serving upon the new Church House Building Committee and

other Church Committees, and he is a Member of the Council of Keble

College, Oxford.

C.T.T.W.

Below, I have reproduced the Parish Magazine articles

I refer to

together with other information that expands on Lyndwood’s life and

work.

Ian Petticrew

February 2018

――――♦――――

SIXTY YEARS THE RECTOR OF TRING

Arriving early for service at mattins recently and occupying the

last pew on the inner south aisle just under the list of Rectors,

Perpetual Curates and Vicars of Tring, which hangs from the pillar

near the church table, I was struck with a feeling of curiosity as

to what might be the average stay of our spiritual pastors, and as

to who might have stayed longest at the head of the Parish. In

a few moments I had gleaned some interesting facts. Over a

period of 664 years from 1266 to 1930, the year of our present

Vicar's induction, there have been 51 ministers. At first they

were called Rectors, then Perpetual Curates, and then towards the

end of last century they were given the title of Vicar. The

average length of ministry is the unfortunate one of thirteen years,

but only one minister stayed exactly thirteen. Five ministers

stayed only one year, and five stayed eleven years. Three

stayed over forty years, and one, Anthony Molyneaux – 1545 to 1605 –

stayed the record period of 60 years. I should think the

Parish must have celebrated his Diamond Jubilee in great style, if

they had such things as Jubilees in those days.

G.B.

From the June 1939 edition of the Tring Parish

Magazine.

IN re ANTHONY MOLINEUX

“And this is law that I’ll maintain,

Until my dying day, sir.”

The reference in our June Magazine to the long ministry of Anthony

Molineux, rector of Tring for 60 years, invites a comparison between

his incumbency and that of the famous Vicar of Bray, who “got

preferment” as the song says in “Good King Charles’s golden days“

and held it through the the reigns of Charles II, James II, William

and Mary, Anne, until his dying day which must have taken place,

judging from the last verse of the song, some little time after the

accession of George l, probably between 60 and 70 years in all.

Our old rector, Anthony Molineux, began his incumbency towards the

end of Henry VIII’s reign and retained it, presumably until death,

during the many changes that followed the accessions of Edward Vl,

Mary, Good Queen Bess’s golden days and into the reign of James l.

These years included the introduction of the two Prayer Books of

Edward Vl, the Marian persecution, the Prayer Book of Queen

Elizabeth, the changes introduced therein in the reign of James I,

and all that these events involved. Mr. Molineux, like the

Vicar of Bray, must have passed through stormy times and to have

retained his position through them all may have been due primarily

to concern for the cure of the souls committed to his charge rather

than to complacency in his attitude towards the Authorities, and

possibly this might be said also for the Vicar of Bray a century

later.

(Unsigned) from the September 1939 edition of the Tring Parish

Magazine.

――――♦――――

Previous Incumbents of Tring Parish Church,

1214-1966.

WILLIAM LINDWOOD

Fastened to a pillar near the South door of the Church is a carved

frame containing a list of the “Incumbents” of Tring from the year

1214 to the present time. This frame was made by the men and

boys of a wood-work class at Wigginton, organised by the late Mr.

Burrell when he was Vicar there; it was presented to the Church by

the writer of these notes more than 30 years ago.

The list is interesting, and there are many points in it to which

attention might be drawn. Here is one. The name of

“William Lyndwood“ who appears as Rector of Tring between the years

1424 and 1442 is almost certainly that of one of the greatest

statesmen of the 15th Century; William Lyndwode, or Lyndewode, or

Lindwood, — for, of course, the spelling of surnames in those days

was much more a matter of taste and fancy than it is today! — who

became Bishop of St. David’s, and died on the 21st October, 1446.

Lindwood was born at a village called Linwood in Lincolnshire;

educated at Cambridge, where he became a Fellow of Pembroke College

(then Pembroke Hall), and later went to Oxford, where he obtained

the degree of Doctor of Laws. It was to the study of the law

that he devoted his life, and the public employments to which that

study led. He held a great many ecclesiastical preferments,

but it must not be supposed that he was personally much engaged in

performing the duties of them. Tring, for example, was

probably in charge of a Vicar or curate, to whom some portion of the

emoluments of the benefice would be assigned. But we may

safely assume that the great man visited, on occasions, this and

every other place from which his revenues were drawn, and that the

people of Tring were proud that their Rector should be one whose

name was so highly honoured throughout the whole Christian world.

In 1414 he was appointed Official, that is, Chief Judge or

Chancellor, of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and in 1417 he was

licensed to preach “both in Latin and English.” In the same

year he was twice sent to France to negotiate treaties for the King,

Henry V, and he afterwards went to Portugal on a similar mission.

Between the years 1423 and 1430 Lindwood was engaged in the writing

of the monumental work upon which his fame chiefly rests, his “Provinciale”,

a book which is the foundation of the English system of

Ecclesiastical Law [Ed. – which I take to be synonymous with

Canon Law], and is still referred to as an authority in our

law courts. It evidently attracted the interest and admiration

of his contemporaries, for from the date of its completion down to

the time of his death we find that he was constantly employed in the

highest affairs of State. Thus, he was sent to conclude a

treaty with Spain (1430); was the King’s representative at the

Council of Basil (1433); and became Lord Privy Seal, and in effect a

Cabinet Minister. He was concerned as an Ambassador in almost

all the dealings between England and continental countries, while

his eminence at home was shown by many appointments of dignity and

and importance, such, for example, as being chosen to open

Parliament in place of a Lord Chancellor who was ill.

Blameless in life, sound in judgment, a loyal Englishman no less

than a loyal Churchman, he was without doubt one of the most

outstanding figures of his generation.

Rectories, Prebendaries, Archdeaconries, and other lucrative offices

were showered upon him, and ultimately he was given the Bishopric of

St. David’s, to which he was consecrated in St. Stephen’s Chapel at

Westminster, where also, in accordance with his Will, he was buried.

There, too, in 1852, his embalmed body was found, with his episcopal

crozier beside it, in a tomb constructed in the wall of the chapel.

In Volume XXXIV. of “Archaeologia” at pages 406 to 430 a somewhat

gruesome description of the discovery, with illustrations to show

the condition of the remains, will be found, together with a

considerable amount of information about Lindwood’s career, the

contents of his Will, etc. There is no mention of Tring, but

Cussans’ History of Hertfordshire states that his successor here,

John Stokys (or Stokes), was instituted to the Rectory of Tring in

1435, “on the promotion of William Lindwood to the See of St.

David’s”, though there is something wrong there, for such promotion

did not take place until 1442. Well, it was a long time ago,

and we must on no account relinquish our claim to have the honour of

William Lindwood’s association with our parish. The best

Edition of the “Provinciale” is the one published at Oxford in 1679,

and the writer of these notes will be glad to hear of any copy for

sale at a reasonable price!

H.B.V.

(From the August 1941 edition of the Tring Parish

Magazine.)

――――♦――――

CANON LAW

From an article by Lawrence Hibbs first published in the 1998

Annual Bulletin of La Société Jersiaise

IN GENERAL

This body of law grew up very gradually. Its beginnings are to

be traced to the practice in the early and universal church (before

the great Schism of 1054, the final separation of the Western and

Eastern Churches) of convening general councils to settle matters of

uncertainty or dispute regarding the practice and discipline of the

church, and to the issuing from time to time of ad hoc

pronouncements for the guidance of the faithful. Side by side

with councils, the decrees of influential bishops were another

source of ecclesiastical legislation and special attention was paid

to Papal decrees. In the middle ages a decisive stage was

reached when Gratian issued his Decretum in 1140. This

collection of decrees became the basis of Roman Catholic Canon Law

and, with supplementary legislation, enjoyed authority in that

church until the present century.

IN ENGLAND

As far as the Church of England was concerned, generally speaking,

until the reform of the 16th century, Roman Canon Law was as binding

in England as it was on the Continent, and it was supplemented by

the local provincial decrees of Canterbury. These were issued

in 1433 as the synodical constitutions of the province in William

Lyndwood’s “Provinciale”.

Following upon the Reformation and the break from Rome, a book of

Canons for the Church of England was passed by the Convocation of

Canterbury in 1604, and by the Convocation of York in 1606.

This is the principal body of canonical legislation enacted by the

Church of England since the Reformation until the present century.

Among the many subjects with which they deal are the conduct of

divine service, the administration of the sacraments, the duties of

the clergy and the care of the churches.

In 1939 the Archbishops, of Canterbury, Cosmo Gordon Lang, and of

York, William Temple, appointed a Canon Law Commission under the

chairmanship of the Bishop of Winchester, Cyril Garbett, to

“consider the present status of Canon Law in England”. This

was undertaken, one suspects, because the Canons were more honoured

in the breach than in the observance; or were simply ignored.

This work of revision, initially delayed by the outbreak of war,

continued through the middle years of the present century and was

largely carried through due to the drive and energy of Geoffrey

Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury, 1945-61.

Eventually, the Canons of the Church of England were promulgated

(authorised for use) by the Convocations of Canterbury and York in

1964 and 1969, respectively, (at which time I was a member of the

Convocation of Canterbury representing the clergy of the diocese of

Winchester). Responsibility for the Canons thereafter fell

upon the General Synod which was formed in 1970. These are the

Canons in force in the Church of England at the present time and are

amended or added to as circumstances demand.

――――♦――――

WILLIAM LYNDWOOD

from Wikipedia

William Lyndwood (c. 1375 – 21/22 October 1446) was an English

bishop of St. David’s, diplomat and canonist, most notable for the

publication of the Provinciale.

CONTENTS

1. Early life

2. Career

3. The

Provinciale

4. Notes

5. Bibliography

EARLY LIFE

Lyndwood was born in Linwood, Lincolnshire, one of seven children.

His parents were John Lyndwood (died 1419), a prosperous wool

merchant, and his wife Alice. There is a monumental brass to

John Lyndwood in the local parish church in which an infant William

is portrayed decked in the robes of a doctor of laws. [1]

Lyndwood was educated at Gonville Hall, Cambridge though few details

are known. [2] He is thought to have become a

fellow of Pembroke College, Cambridge though later he moved to

Oxford where he became DCL “probably rather by incorporation than

constant education”. He took Holy Orders and was ordained

deacon in 1404 and priest in 1407. [1]

CAREER

Lyndwood had a distinguished ecclesiastical career. In 1408,

Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury appointed Lyndwood to his

consistory court. [1] Then, in 1414, Lyndwood

was appointed “Official” of the Archbishop of Canterbury (i.e.

his principal adviser and representative in matters of

ecclesiastical law) in 1414, and Dean of the Arches in 1426, while

holding at the same time several important benefices and prebends.

In 1433 he was collated Archdeacon of Stow in the Diocese of

Lincoln, and in 1442, after an earnest recommendation from King

Henry VI, he was promoted by Pope Eugene IV to the vacant See of St.

David’s. During these years Lyndwood’s attention was occupied

by many other matters besides the study of canon law. He had

been closely associated with Archbishop Henry Chichele in his

proceedings against the Lollards. He had also acted several

times as the chosen representative of the English clergy in their

discussions with the Crown over subsidies, but more especially he

had repeatedly been sent abroad on diplomatic missions, for example

to Portugal, France and the Netherlands, besides acting as the

King’s Proctor at the Council of Basle in 1433 and taking a

prominent part as negotiator in arranging political and commercial

treaties. [3]

He was also Keeper of the Privy Seal from 1432 to 1443. [4]

Despite the fact that so much of Lyndwood’s energies were spent upon

purely secular concerns nothing seems ever to have been said against

his moral or religious character. [3] He was

buried in St Mary Undercroft, the crypt of St Stephen’s Chapel,

where his body was found in 1852, wrapped in a ceremonial cloth and

allegedly “almost without signs of corruption”. [3]

THE PROVINCIALE

Lyndwood, however, is chiefly remembered for his great commentary

upon the ecclesiastical decrees enacted in English provincial

councils under the presidency of the Archbishops of Canterbury.

This elaborate work, commonly known as the Provinciale,

follows the arrangement of the titles of the Decretals of Gregory IX

in the Corpus Juris, and copies of much of the medieval

English legislation enacted, in view of special needs and local

conditions, to supplement the jus commune. Lyndwood’s

gloss gives an account of the views accepted among the English

clergy of his day upon all sorts of subjects. [3]

It should be read together with John of Acton’s gloss, composed

circa 1333-1335, on the Legatine Constitutions of the thirteenth

century papal legates, Cardinals Otto and Ottobuono for England,

which was published with the Provinciale by Wynkyn de Worde.

The Provinciale was published as Constituciones prouinciales

ecclesie anglica[n]e by Wynkyn de Worde in London in 1496).

The work was frequently reprinted in the early years of the

sixteenth century, but the edition produced at Oxford in 1679 is

sometimes seen as the best. [3]

The

Catholic Encyclopaedia [3] saw the work as

important in the controversy over the attitude of the Ecclesia

Anglicana towards the jurisdiction of the pope. Frederic

William Maitland controversially appealed to Lyndwood’s authority

against the view that the “Canon Law of Rome, though always regarded

as of great authority in England, was not held to be binding on the

English ecclesiastical courts”. [5] The

Catholic Encyclopaedia also contends that Maitland’s arguments

had found broader acceptance in English law:

In pre-Reformation times no dignitary of the Church, no archbishop,

or bishop could repeal or vary the Papal decrees [and, after quoting

Lyndwood’s explicit statement to this effect, the account continues]

Much of the Canon Law set forth in archiepiscopal constitutions is

merely a repetition of the Papal canons, and passed for the purpose

of making them better known in remote localities; part was ultra

vires, and the rest consisted of local regulations which were

only valid in so far as they did not contravene the jus commune,

i.e. the Roman Canon Law.

— Halsbury’s Laws of England (1910) vol. 11, p. 377.

However, Maitland’s view of Lyndwood’s authority was attacked by

Ogle. [6]

__________

NOTES

1.

Helmholz (2006)

2.

“Lyndwood,

William (LNDT375W)”. A Cambridge Alumni Database.

University of Cambridge.

3.

Thurston (1913)

4.

Powicke Handbook of British Chronology p. 92

5. English Historical Review 1896, p. 446.

6.

Ogle [1912]

__________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public

domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913).

Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton.

Baker, J. H. (1992). “Famous English canon lawyers: IV William

Lyndwood, LL.D. (†1446) bishop of St David’s”. Ecclesiastical Law

Journal. 2: 268–72.

— (1998). Monuments of Endlesse Labours: English Canonists and

Their Work, 1300–1900. London and Rio Grande: The Hambledon

Press with the Ecclesiastical Law Society. ISBN 1-85285-167-8.

Cheney, C. R. (1973). “William Lyndwood’s Provinciale”.

Medieval Texts and Studies: 158–84.

Ferme, B.E. (1996). Canon Law in Late Medieval England: A Study

of William Lyndwood’s ‘Provinciale’ with Particular Reference to

Testamentary Law. Rome: LAS. ISBN 88-213-0329-2.

Helmholz, R. H. (2006) “Lyndwood, William (c.1375–1446)”,

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University

Press, online edn, accessed 8 Sept 2007 (subscription or UK public

library membership required)

Hunter, J. (1852). “A few notices respecting William Lynwode, judge

of the arches, keeper of the privy seal, and bishop of St. David’s”.

Archaeologia. 34: 403–5. doi:10.1017/s0261340900001193.

Maitland, F. W. (1898). Roman Canon Law in the Church of England.

London: Methuen & Co.

Ogle, A. (2000) [1912]. The Canon Law in Mediaeval England: An

Examination of William Lyndwood’s “Provinciale,” in

Reply to the Late Professor F. W. Maitland. Lawbook Exchange

Ltd. ISBN 1-58477-026-0.

Powicke, F.

Maurice and E. B. Fryde Handbook of British Chronology

2nd. ed. London: Royal Historical Society 1961

Reeves, A. C. (1989) “The careers of William Lyndwood”, in J. S.

Hamilton and P. J. Bradley (eds) Documenting the Past: Essays in

Medieval History Presented to George Peddy Cuttino, pp197–216,

Woodbridge: Boydell Press, ISBN 0-85115-515-4

Thurston, H. (1913) “William

Lyndwood”,

Catholic Encyclopaedia

Lyndwood’s Provinciale: The Text of the Canons Therein Contained,

Reprinted from the Translation Made in 1534, ed. J. V. Bullard

and H. Chalmer Bell (London: Faith Press, 1929). |