|

NOTES AND EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

CHAPTER 4

THE PRELIMINARIES:

CHOOSING THE ROUTE, OBTAINING THE ACT

BACKGROUND

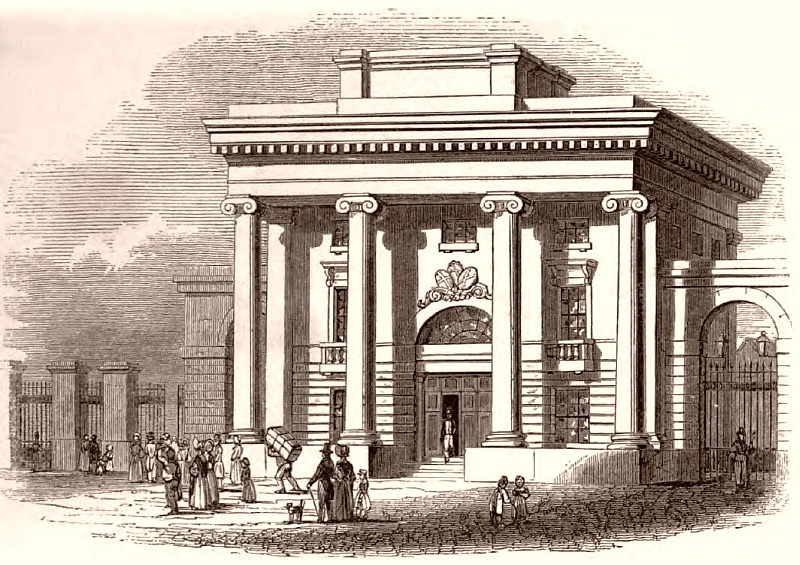

Curzon Street Station, Birmingham, the original

London and Birmingham Railway terminus.

“Robert Stephenson, in those days, almost lived on the

line, and the first occasion on which he visited the portion in question, after

the contracts were let, accompanied by the Secretary and by four or five of the

Directors, was the twelfth time that he had walked the whole distance from

London to Birmingham.”

Personal

Recollections of English Engineers, F. R. Conder

(1868)

Much of this chapter concerns the problems that the promoters of the London and

Birmingham Railway were confronted with in Parliament, for having carried out a

great deal of exploration to identify the most appropriate route, all matters

being considered (and there many), there was then a further major hurdle to

overcome before the ceremony of ‘cutting the first sod’ could take place.

This stemmed from the need to obtain a ‘private’ Act of Parliament, which was

(and remains) necessary to authorise the construction of what today would be

described as a ‘transport infrastructure project’ and all which that entails.

――――♦――――

PRIVATE BILLS

A draft Act of Parliament is called a Bill. Unlike a ‘public’ Bill’, which

is a proposal for a law that applies to everyone within its jurisdiction, a ‘private Bill’ is a proposal for

a law that has more limited application. It applies only to a

specified individual, group of individuals, or

corporate body, such as a local authority or public company. If such a Bill

is approved by Parliament it then becomes a private Act (of Parliament).

The privileges granted by a private Act might include relief from another law,

or a unique benefit, or powers not available under the general law, or relief

from the legal responsibility for some otherwise unlawful act.

If the capital to construct a railway was to be raised by public subscription ―

which in the railway-building era was the case [1]

― and/or its course was to lie across public land and that of individuals not

associated with the scheme, a private Act had first to be obtained. There

were two reasons for this. First, under the cumbersome law of the day,

joint-stock companies could only be set up either by royal charter or by

private Act of Parliament. Second, an Act of Parliament was necessary to

authorise a scheme to proceed in accordance with whatever terms Parliament laid

down. For example, a provision generally to be found in a private railway

or canal Act gave the proprietors the legal power to acquire specified private

land by compulsory purchase; in effect, to acquire it without the owner’s

consent but with fair monetary compensation. Other provisions and

stipulations might include the right to cross public highways, divert rivers and

streams, fence the line, hold General Assemblies, and the arbitration procedures

to be applied in cases were land values were in dispute, to name just a few.

When applying for a private railway Bill, a necessary preliminary was for the

promoters, through their legal representatives, to advertise their intentions in the official newspaper of record,

The London Gazette, and in other

newspapers serving the areas likely to be affected. This was to alert the

general public to what was intended in order that the scheme or some part of it

might be challenged, either directly with its promoters or with the legislature

when it eventually came before Parliament. During its parliamentary

committee stages, a Bill might be challenged on specific matters by individuals

or corporate bodies who considered they would in some way be affected adversely

by its provisions.

In addition to informing the general public, parliamentary standing orders laid

down specific requirements that had to be met (see also Appendix I.)

to ensure that the legislature was also properly appraised of the promoters’

intentions with regard to their scheme:

“The different documents required to be deposited at

the Private Bill Office on or before November 30, are as follows:― Plans,

sections, and books of reference; and [London] Gazette notices; on or before

December 23 the petition for the bill with agent’s declaration and copy of the

bill annexed, and other copies for the use of members; on or before December 31,

estimates, declarations, lists of owners, occupiers, and lessees, distinguishing

who assent, dissent, or are neuter, and certain other documents in the case of

joint stock companies. All these documents must be deposited after 8 am and

before 8 pm, and not upon a Sunday or Christmas Day.”

Private Bill Legislation, S. B. Bristowe (1859).

|

|

|

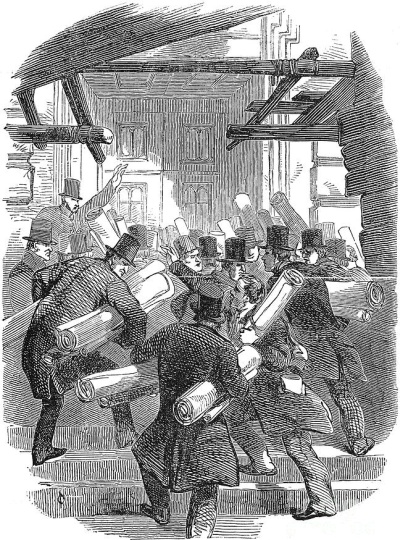

Depositing railway plans

during the ‘Railway Mania’. |

The deadline dates had to be met if a Bill was to be considered in the following

session of Parliament. Francis Conder [2] left a vivid

picture of the haste with which the deposited plans had sometimes to be

completed by drawing office staff working around the clock, and then despatched

post chaise to meet the parliamentary deadline:

“Accordingly for some ten days the labour of plotting

sections, copying plans, numbering and copying references, and the like, went on

almost without intermission. At nine in the evening would appear mighty

bowls of oysters, gallons of ale, and other materials of a rude but hearty

repast. A respite of some three quarters of an hour would be filled up by

uproarious hilarity and then a fierce objurgation from the chief ― the moment

before the chief reveller ― for so scandalous a manner of wasting the company’s

time would set all briskly to work again . . . .

The crisis came on a Monday. The farthest distance that could be traversed

in a given time, by the best paid post boy, had been carefully studied. In

the outlying counties the deposits had been sent off by the Saturday. On

through Sunday and Sunday night toiled the diminished staff. The last post

chaise was in waiting at the door . . . . Without his coat, the engineer in

chief was with his own hands completing the last book of plans . . . . At last

the final sheet is pasted in, the book closed, the expectant messenger tumbled

into the chaise with all his credentials; whirling off with a shout, and with

the proper accompaniment of an old shoe flung after the carriage for luck; and

now, if wheels and horseflesh hold, and no sleepy turnpike man make undue delay,

the deposit for the standing orders is safe. The wearied may repose, the

strain is taken off, and men begin to fear that they will hardly be able to

sleep if they go to bed in a regular way.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers, F. R. Conder (1868).

In addition to the documents deposited with the Private Bills Office, copies of

them were

also required to be deposited with the clerks of the peace in the counties

through which the line was planned to pass,

and with the relevant parochial authorities, while landholders had to be provided with a section showing the depth of cutting

or embankment across their estates. Facsimiles had therefore to be made, a

formidable task in the days before more sophisticated reproduction techniques

were available:

“If you prick through a dozen sheets of drawing-paper

at once, a very slight deviation from the perpendicular in the needle is enough

to make the twelfth plan very different from the first. Inaccuracies of this

kind might be harmless while you had to do with parish clerks or county

surveyors; but the great feature of the parliamentary fight was the opposition. Recalcitrant landowners, hostile corporations, or even rival companies, set

their own engineers to work. With more time to command for criticism than for

construction, these opponents would sometimes go to the expense of taking

tracing of all the deposited plans, and then denouncing to the expectant

legislators their want of identity.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers, F. R. Conder (1868).

The necessary documents having been deposited within deadline and the Bill

placed before Parliament, if all went well it would eventually progress to the

committee rooms in the Commons and the Lords for detailed scrutiny. It was

at this stage that those applying for a private Act would sometimes become

embroiled in a lengthy and very expensive legal wrangle.

Committee hearings are a quasi-judicial process, with witnesses ― both for and

against the scheme ― appearing to give evidence on which they could be cross-examined by

committee members and by lawyers engaged to represent the interests of those

promoting and opposing the Bill. Hearings on railway Bills were sometimes

entertaining, to the extent that the reputations of some of the professional

witnesses have gone down in history:

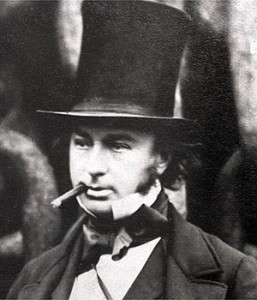

“Mr Brunel [Isambard Kingdom Brunel]

had a very high reputation as a witness. Mr. St. George Burke, Q.C., has

communicated a memorandum on this subject: ―

I. K. Brunel FRS (1806-59), Civil Engineer.

‘As a witness he [Brunel] could always be

relied on as a perfect master of the case he had to support and he had the rare

quality of confining his answers to a simple reply to the questions put to him,

without appearing as an advocate. . . . In his cross examinations he was

generally a match for the most skilful counsel, and by the adroitness of his

answers would often do as much to advance his case as by his examination in

chief . . . . Although he had attained to great celebrity as a witness, the

committee room being crowded to hear him, he always declined to engage in the

very lucrative work of a professional witness. He made a rule never to

appear except on behalf of undertakings of which he was the engineer, or with

which his own companies were interested.”

The Life of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Civil Engineer, Isambard Brunel

(1870).

But other witnesses performed less well. Despite his many noted talents,

one expert witness, Doctor

Dionysius Lardner, has done down in history for his

disagreements in committee with Brunel. Perhaps the most famous of these

relates to the construction of the Box Tunnel on the London to Bristol railway.

The tunnel was at a 1-in-100 gradient. Lardner asserted that if a train’s

brakes failed in the tunnel, it would accelerate to over 120 mph, at which speed

the passengers would suffocate. Brunel pointed out to the committee the

basic error in Lardner’s calculation, his total disregard of air-resistance and

friction.

Regardless of whether they were well founded, when challenges were mounted

hearings could drag on for weeks, and even if the promoters were successful in

obtaining their Act, the costs they accrued in the process could be exorbitant;

and when their application failed, and their Bill was thrown out, they were also

fruitless. In an extreme case, such as the Great Northern Railway Bill of

1845-46 ― which ran out of time during the 1845 parliamentary session and had to

be continued the following year ― the promoters alone spent £433,000.

Decisions could also be inconsistent, for while local interests might be

assessed accurately, the national interest tended to be neglected, as events

were to demonstrate to the promoters of the London and Birmingham Railway.

For in an age when the landed gentry held considerable sway over parliamentary

decisions ― even when an application for a private Act was well prepared and

convincing ― the outcome of a committee hearing was far less predictable than

might be the case today.

―――――♦―――― |

|

THE FIRST PROPOSALS

The earliest proposal to build a mechanically-worked railway from

Warwickshire into London appears to have been considered as early as

1820, when the far-sighted railway promoter William James surveyed a

route. The ‘Central Union Railroad’ was to commence at the

canal basin at Stratford-on-Avon (which provided a waterway link

into Birmingham), then pass through Moreton-in-Marsh

(Gloucestershire), Oxford and Uxbridge to a terminus at Paddington.

[3] Although

16-miles of its northern section were built [4]

to convey coal from the Stratford Canal to Moreton-in-Marsh, with

return cargoes of limestone and agricultural produce, nothing came

of the remainder of James’s grand scheme.

The next proposal followed soon after. Towards the end of

1824, during the prelude to the ‘Railway Fever’ of 1825-1826, [5]

the ‘London and Birmingham Railroad Company’ was formed:

“For the purpose of effecting a direct,

cheap, and expeditious communication between the metropolis and the

central part of England, it is proposed to form a Railroad from

London to Birmingham, connecting itself at the latter place with the

undertaking already commenced, the Birmingham and Liverpool

Railroad, and thus opening a direct communication with Manchester.”

The Times, 21st December 1824.

It was proposed to raise capital of £1.5M, this to include the cost

of “stationary and locomotive engines”. John Rennie Jnr.

(later Sir John Rennie) was commissioned to survey a route from

London to Birmingham, the fieldwork being undertaken during 1824 and

1825 by the brothers John and Edward Grantham.

In his survey report, [Appendix II.] Rennie

proposed commencing near the Islington Tunnel of the Regent’s Canal,

then following a line via Harrow Weald to Otterspool, to the east of

Watford, then through Leavsden Green to Hunton Bridge, along the

Gade Valley via Hemel Hempstead and across the ridge of the

Chilterns through the ‘Dagnall Gap’. The route then passed

north of Aylesbury; through Quainton; to the north of Bicester and

of Banbury; to the east of Warwick; to the southwest of Coventry [6];

and then to Acock’s Green . . . . “crossing the Worcester Canal

to the Ilchington road where it unites with the proposed Birmingham

and Liverpool Railway, being a total distance of 121 miles from

London” ― the junction referred to appears to be in the vicinity

of Stirchley, some 3 miles to the south of the present-day city

centre. Rennie mentions that his surveyors had tried several

approaches to Birmingham, including “. . . .Gaydon Hill by

Leamington, Warwick, and Kenilworth, which failed on account of the

inequalities of the country and the numerous parks and other

valuable and private property which it would have necessarily

interfered with . . . . “

Rennie then goes on the make some general observations (the thrust

of one being felt during the first attempt, in 1832, by the London

and Birmingham Railway Company to gain parliamentary authorisation for the line, their

application being defeated on the interests of the landed gentry):

“The principal objects in determining the

most proper line are, to make the course of the railway as direct as

possible between London and Birmingham; to avoid, as much as

practicable, all parks, pleasure grounds, and other valuable public

and private property; and to avoid interference with existing canals

and to embrace as many populous and important towns along the line

as can be done consistently with a reasonable degree expenditure.”

Rennie then reviews the problems that stood in the way of a shorter

route:

“The country between London and Birmingham

may be chiefly divided into four districts, comprehending the vales

of the river Thames, Aylesbury, the rivers Charwell and Avon, all of

which are surrounded by extensive ridges of high hills, which are

again intersected by numerous minor valleys, through which the

tributary streams descend towards the principal rivers

above-mentioned. To effect, therefore, a direct communication

between London and Birmingham, the whole of these must be passed by

numerous inclined planes, extensive cuttings, and embankments,

without regard to the situation of private property or otherwise; so

it will be extremely difficult to keep estimate within reasonable

bounds, and the only advantage of doing this, viz., shortening the

line, would be more than counterbalanced by the above

inconveniences.”

In other words a shorter route, while possible, would be outweighed

by the additional cost of engineering and of crossing private

estates. Rennie concludes by pointing out that although the

line he proposed was 12 miles longer than the London to Birmingham

mail coach route, it was 40 miles shorter than that by canal; and if

the heavier ruling gradient of 20ft to the mile ― as opposed to 14ft ― were to

be acceptable, a saving of 5 miles could be made.

Shortly afterwards the shareholders met to approve the route, to

commission a detailed survey and to make preliminary overtures to

the landowners whose property would (assuming a private Act was obtained)

become subject to compulsory purchase:

“The report of Mr. John Rennie,

recommending that the projected line from London to Birmingham

should go in the most direct way, viz. ― to commence at the Thames,

near the East and West India Docks, then by Islington to the North

of the Regent’s Park and Paddington, to the South of Harrow, to the

vicinity of Tring and Wendover, to the North of Aylesbury, Bicester,

and Banbury, between Coventry and Warwick, direct to Birmingham,

having been read . . . . Resolved ― that such a line be approved of,

and the necessary Survey immediately taken: and that as soon as they

are in a sufficient state of forwardness, they be submitted to the

Land-holders, the Proprietors being most anxious to carry into

effect the project with as little inconvenience as possible to

private property.”

The Morning Post, 23rd

February 1825.

But that meeting appears to have been the high point in the life of

the ‘London and Birmingham Railroad Company’, for in June 1826

announcements appeared in the press that the company was to be

dissolved:

“It is with considerable regret that we

hear of the proposed London and Birmingham Railway plan is about to

be abandoned . . . . after it has been satisfactorily ascertained

from actual surveys by experienced engineers, that a practicable

line of only 116 miles length, without inclined planes, standing

machinery or tunnelling, can be effected; and without the necessity

of passing through any Nobleman’s park, or interfering with the

Canals more than be simply crossing them in the same manner as any

ordinary road.”

Birmingham Gazette, 12th June

1826.

The reason for the dissolution of the company probably stemmed from the ‘banking

panic’. [7] Of the £17,000 that had been

subscribed, £2,500 had been spent on survey and legal fees, leaving

the promoters with a balance of 15s 9d in the pound subscribed.

Rennie’s report, together with the plans, sections, minute books,

documents and other company papers were to be preserved by the

respective solicitors.

―――――♦―――― |

|

LATER PROPOSALS

Plans to build the line then lay dormant until, in 1830, notices

posted by the ‘London and Birmingham Railway Company’ began to

appear in the press; nine of its twenty-five board members including

the Chairman, William Chance, High Bailiff of Birmingham, had sat on

the board of the earlier company. [8]

Rennie was again engaged, presumably to develop his earlier outline

plans and sections to a standard sufficient to satisfy the

requirements of parliamentary standing orders, particularly with

regard to listing the owners of the tracts of land across which the

line was to pass and to record those that were either ‘assenters’ or

‘dissenters’:

“To obviate the mischief and disappointment

that might ensue from any partial or imperfect attempts to lay down

a line of Railway between London and Birmingham some individuals in

both places have considered it expedient to adopt preliminary steps

for the accomplishment of this great work. With this view in

mind they have referred to Messrs Rennie, who were consulted in the

year 1826 upon a similar undertaking; and who have pointed out a

practical and nearly direct line between London and Birmingham,

founded on actual examination and surveys of the face and levels of

the country. A further examination of the line and the country

between the two places is now in progress; and no pains will be

spared to render the line perfect, as a line of national

communication.”

Birmingham Gazette, 19th July

1830.

But competition now emerged in the form of ‘The London, Coventry,

and Birmingham Railway Company’, which had engaged the civil

engineer Francis Giles to identify a suitable route. That

which Giles proposed was similar to Rennie’s at its southern end,

also passing to the east of Watford through South Mimms. With

regards to the Giles proposal overall:

“For the present it may be sufficient to

state that it will commence in the open grounds at Islington, near

London, and proceed by Hornsey, East Barnet, South Mimms, Hemel

Hempstead (where it will be joined by a branch from the Edgware

road) and passing the Chiltern hills at Dagnall gap, to the East

[actually the West] of Dunstable, will proceed by

Leighton Buzzard, Fenny Stratford, Rugby and Coventry, and thence by

Mendon and Stonebridge, into the Tame Valley, near Birmingham, and

thence form a junction with the intended Birmingham and Liverpool

Railway” [The Grand Junction Railway].

The Times, 5th July 1830.

It is interesting to note that Giles bypasses Northampton and, like Rennie,

is vague as to where exactly the central Birmingham

terminus was to be. Overall, the

promoters of the Coventry route claimed that . . . .

“. . . . While it will furnish every

accommodation to the town of Birmingham, it will deviate from the

direct route between Liverpool and London, which lies to the east of

Birmingham, it will pass near the large manufacturing City of

Coventry, and may readily be connected with the extensive coal-field

in that neighbourhood ― it offers the great agricultural counties of

Leicester and Northampton additional facilities for the conveyance

of their corn and cattle to the Birmingham and London markets, and

it presents no variation of level but such as may be easily adapted

to the use of the locomotive steam engine . . . . The Committee has

the satisfaction of announcing to the public that they shall have

the advantage of Mr. George Stevenson’s (sic)

services . . . . ”

Birmingham Gazette, 16th August

1830.

Meanwhile, at a meeting held on 19th July 1830, the board of the

London and Birmingham Railway Company was at pains to disassociate

itself from this new enterprise . . . .

“. . . . this committee, most of whom gave

their personal assistance, and largely contributed to the expense of

surveys made by Messrs. Rennie in the years 1825 and 1826, of the

line of Railway from Birmingham to London, having adopted that line,

subject to the improvements which enlarged information and repeated

experiments on this mode of transit have rendered obvious, and in

which considerable progress has, by recent surveys, been made; and

being satisfied that the line so adopted by them presents the most

eligible and direct route from Birmingham to London, are fully

determined to persevere in their undertaking.”

Birmingham Gazette, 26th July

1830.

The article rather suggests that the “recent surveys” to

which it refers were to refine the route identified by the Granthams

during 1824-25. However, the travel writers E. C. and W.

Osborne (and others) refer to the investigation of a possible line

through Oxford . . . .

“Between London and Birmingham two

different routes were proposed in 1830, one by Oxford and Banbury,

by Sir John Rennie, another line passing close by Coventry, by Mr

Giles. A company was formed to carry out the former proposal, and

another to realise the latter; each company had its separate suite

of directors, and these foreseeing the danger and loss that must

inevitably have resulted from the competitive struggle between two

such formidable public bodies wisely entered into arrangements for a

union of the two companies, which was effected, on September the

11th 1830. In consequence of the opinion of Mr. George

Stephenson being decidedly in favour of the line by Coventry, it was

concluded that that should be the route of the London and Birmingham

railway.”

Osborne’s London & Birmingham

Railway Guide, E. C. and W. Osborne (1840).

It is unclear whether this was an entirely new proposal or, as seems

likely, a misunderstanding of the route Rennie had earlier

proposed (Appendix II.), which at its nearest point

(Brackley, near Banbury) passes some 30 miles to the north of

Oxford.

Faced with the prospects of a mutually damaging conflict resulting

from two similar railway Bills being submitted to Parliament, the

competing companies jointly commissioned George Stephenson to review

their respective plans and choose between them. Following

careful examination of the country, Stephenson recommended that

proposed by Giles,

via Coventry:

“The one set of projectors advocated a line

by Coventry; the other adventurers being in favour of a route

through Banbury and Oxford. George Stephenson being applied to

for an opinion by the competing parties, decided in favour of the

Coventry route. The consequence of this decision was that the

rival Companies, instead of aiding the external enemies who were

ready to destroy both of them, prudently joined their forces, and

with united influence applied to Parliament for a line through

Coventry.”

Life of Robert Stephenson, J. C.

Jeffreson (1866).

In the autumn of 1830, the two companies combined their

resources to form ‘The London and Birmingham Railway Company’, [9]

‘George Stephenson and Son’ being engaged as civil engineers (Appendix

III.), but not before there had been some soul-searching

between father and son:

“At the meeting of gentlemen held at

Birmingham to determine upon the appointment of the engineer for the

railway, there was a strong party in favour of associating with

Stephenson a gentleman [possibly the civil engineer

Joseph Locke (1805-60)] with whom he had

been brought into serious collision in the course of the Liverpool

and Manchester undertaking. When the offer was made to him

that he should be joint engineer with the other, he requested leave

to retire and consider the proposal with his son. The two

walked into St. Philip’s churchyard, which adjoined the place of

meeting, and debated the proposal. The father was in favour of

accepting it. His struggle heretofore had been so hard that he

could not bear the idea of missing so promising an opportunity of

professional advancement. But the son, foreseeing the

jealousies and heart-burnings which the joint engineership would

most probably create, recommended his father to decline the

connection. George adopted the suggestion, and, returning to

the committee, announced to them his decision, on which the

promoters decided to appoint him the engineer of the undertaking in

conjunction with his son.”

The Life of George Stephenson and

of his son Robert Stephenson, Samuel Smiles (1862).

And to oversee the activities of George Stephenson and Son . . . .

“. . . . a committee of survey was

appointed to establish a regular communication with the Engineers,

by way of periodical reports, and to correct errors, make

improvements, confirm friends, and conciliate enemies.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe, Peter Lecount (1839).

Although the Stephensons were appointed joint Engineers-in-Chief,

Stephenson Snr. gradually receded into the background leaving his son at

the helm, and he immediately set about seeking ways to refine the

existing route:

“Robert Stephenson made three distinct

surveys for the London and Birmingham line, besides several minor

surveys of different portions of the country, for the purpose of

ascertaining whether the route could not be improved. The

first survey was made in the autumn of 1830. In 1831 a second

line was marked out, almost identical with the one eventually

executed. The plans and sections having been deposited, and

the requisite amount of shares subscribed for, an application was

made to Parliament, and a Bill to enable the Company to make their

proposed railway was read the first time on February 20, 1832.

The third survey was made in the autumn following the last date.”

Life of Robert Stephenson, J. C. Jeffreson (1866).

The autumn of 1830 saw the publication of statutory notices in the

London Gazette and other newspapers advising of the Company’s

intention to apply to Parliament for an Act to authorise construction

of the line, the Coventry route being that proposed. It is

interesting to note the difference between the estimated cost of

what was then being proposed, and what was eventually delivered:

“It is not a little curious to turn back,

and watch the first beginnings of a work of such magnitude as this

railway, which will cost more than £5,000,000. In November,

1830, there was to be one line of rails only, and the work was to be

done for £6,000 per mile. The capital was then one million and

a quarter, and no greater velocity contemplated than eight miles an

hour. Shares got up to nine and ten premium on the prospectus,

at which many hundreds were sold. Then it was determined to

have two lines; and at that announcement the shares fell directly to

a discount . . . . We wonder that the speculators of those days

would have thought, if they could then have been informed what the

real cost of the present two lines would be. One thing is

certain, there would not have been a railway between London and

Birmingham for many a year.”

The History of the Railway

Connecting London and Birmingham, Lieut. Peter LeCount R.N.

(1839).

The statutory notices describe a route commencing at a point near Horsfall Basin

(later known as Battlebridge Basin) on the Regent’s Canal, slightly

to the north-east of King’s Cross Station, to terminate at

‘Nova Scotia Gardens’ within the Parish of Aston near Birmingham. [10]

Where exactly the line was to cross the Chilterns had yet to be

decided; separate notices published in the London Gazette

during October and November 1830, specified routes through both the

Dagnall (Gade Valley) and the Tring (Bulbourne Valley) gaps. [11]

The public was also informed that the Company intended to seek

powers to build a branch railway, which appears ― the notice is not

specific ― to have been intended to serve Northampton.

Although much effort had been put into identifying the optimum

route, there was insufficient time to assemble a convincing case to place

before Parliament. It was therefore decided to defer

application for an Act until the 1831 session:

“From this sketch of the nature of the

ground it is evident what care was required in searching for the

best line of road. Mr. Robert Stephenson examined the country

in the Autumn of 1830, and was ordered to prepare the necessary

plans and sections to deposit with Parliament in the November of

that year. The time, however, was much too short; and it was

only by great haste and force of numbers that the preliminary step

of depositing these plans was accomplished.

After some further preliminaries, therefore, it was determined to

defer the application to Parliament for a bill till the following

year, and thus give the Engineer the opportunity of examining and

selecting such a line as he could confidently report on as being the

best the country would afford. When this was done, the plans

and sections were deposited with Parliament in the November of 1831,

showing a line almost identical with that which is now executed

where the steepest gradient except where the line has been extended

from Camden Town to Euston Square is sixteen feet per mile.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe, Peter Lecount (1839).

In addition to the routes proposed by Rennie and Giles, and the work

undertaken by Robert Stephenson, two further explorations were

carried out prior to the Company’s first application to Parliament

(in 1832). Richard Creed, a banker by profession and

subsequently the Company’s Secretary, investigated at least two

further routes, well to the east of that finally chosen:

“In the Summer of 1831 Mr. Creed examined

another line, with the mountain barometer, from Northampton, through

Bedford, Baldock, and Hutford, to near the West India Docks; another

line through Buckingham, Brackley, and Warwick was surveyed, and

many other attempts at improvement were made, each line having its

advantages and disadvantages; the chief things next to the traffic

to be kept in view being to select that line where there is the

least difference between the highest and lowest levels, and also

that which is least expensive even if it is not the most direct.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe, Peter Lecount (1839).

Nothing came of

Creed’s proposals, but both they and the other survey work carried

out serve to illustrate the amount of effort that went into

searching for a route that took full account of the topography, the

commercial prospects, and the desirability to avoiding the estates

and pleasure grounds of the landed gentry.

―――――♦―――― |

|

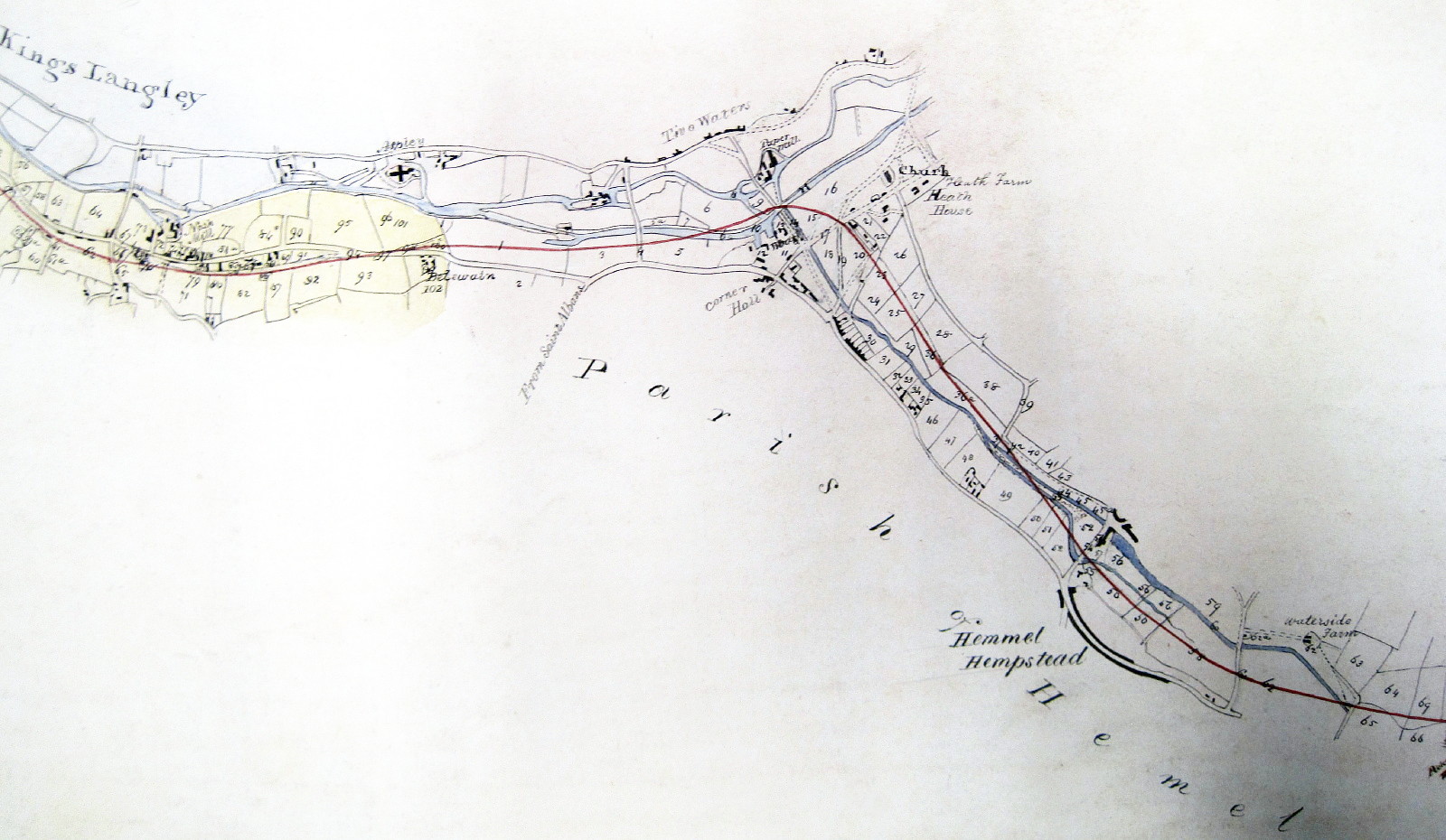

The

original plan for the London and Birmingham Railway at Watford, was to route the line to the west of

the town, through the Cassiobury and Grove Parks, and then along the Gade Valley in company with the Grand

Junction Canal, as shown above. But such

was the influence of the aristocracy, that following strong

objections from the Earls of Essex and Clarendon the line was

routed to the east of Watford, hence the long Watford Tunnel. |

|

THE FIRST RAILWAY BILL

It was not unusual for a railway Bill to meet determined opposition, both

in the run up to its presentation to Parliament and during its

passage through both houses. Following the public announcement

of the Company’s intentions, organised protest quickly gathered

force. Vested interests ― such as the stagecoach operators,

canal companies, turnpike trusts, inn-keepers along the coaching

roads, and the landed gentry, in league with individuals opposed to

the scheme due to “a train of other evils too numerous to

particularize” ― began to meet at towns along the proposed

route:

“RESOLVED ― That it

is the opinion of this Meeting that the projected Railway will, if

carried, be productive of ruin of the best interests of the country,

by the injury which it cannot fail to produce to agriculture, the

basis of its prosperity ― by the destruction of turnpike roads, the

sacrifice of the securities created by Parliament, upon the faith of

which individuals have advanced thousands for the support of such

roads ― by the entire subversion of the vested interests in property

of various descriptions ― by the depriving of the labouring classes

of the community of employment ― by the barrier which it will create

between those parts of the country which it will intersect, and by a

train of other evils too numerous to particularize.”

Birmingham Gazette, 7th

February 1831.

“Very numerous and influential meetings of

the proprietors of estates, and others, between London and Leighton,

were held last week at Great Berkhamstead and Watford, at the former

of which the Right Hon. Richard Ryder, and at the latter the Earl of

Clarendon, presided, when resolutions were entered into, and a large

subscription made for opposing the projected rail-roads from London

to Birmingham. We understand a similar meeting will be held in

London this week.”

York Herald, 21st January

1832.

MPs were lobbied and fighting funds set up with which to hire

lawyers to express their clients’ grievances most forcefully during

committee hearings, and to endeavour to present as unreliable or

incredible the evidence given by the witnesses appearing for the

promoters.

While the protest movement’s meetings were being reported in the

press, the Company was also using the public prints to present their

own case, for by now they could refer to the comfort (“being

superior to the best turnpike roads”) and safety of the rail travel

by then being experienced on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (opened 15th

September 1830), which also provided some interesting statistics on

the economics of steam-hauled rail transport:

“Goods and merchandize of all kinds are

conveyed from Liverpool to Manchester by the Railway in four or five

hours, for eleven shillings a ton, instead of from thirty-six hours

to a week or ten days at 15s. per ton, as by the water conveyance.

The most rapid coach travel at the rate of nine or ten miles an

hour, a speed at which in three or four years destroys the horses,

while the locomotive engines travel regularly from 15 to 20 miles an

hour, and occasionally with much greater rapidity . . . .”

Birmingham Gazette, 31st

January 1831.

There was no doubt that “waterway conveyance” between

Liverpool and Manchester [12] had, until the

arrival of the railway, been run with the arrogant indifference of

the monopoly operator, a malaise that extended to much of the

canal network. It is therefore unsurprising that when

the London and Birmingham Railway Bill came before Parliament it

faced stiff opposition from competing canal companies. [13]

Their fears were well founded, for following the Railway’s opening

the canals soon lost urgent and perishable cargoes to this quicker

form of transport, which having captured that category of business

then moved on to absorb the canals’ staple deadweight cargoes,

particularly coal. By the end of the century, long-distance

canal traffic on the London to Birmingham route had dwindled, to the

extent that the Grand Junction Canal in particular was left to rely

on the short-haul traffic south of

Berkhamsted, which did not face

strong railway competition.

Other public fears arose from the unknown. People had yet to

form a realistic view of the extent to which the railways would

interfere with their everyday lives and the services they could

expect to receive when they chose to use them. Again the Company

attempted to allay their fears, particularly those of the more

influential of their prospective travellers:

“The railway will either pass under or over

the great roads, never on the same level, will be carefully fenced

every where, and ornamentally when in sight of gentlemen’s

residences; the carriages make little noise, the engines produce no

smoke. Most convenient and elegant carriages will be provided

for individual passengers and for families, whose carriages, horses,

servants, &c. may be taken with them on the Railway, ready to drive

off from any point at which they may wish to leave it.”

Birmingham Gazette, 31st

January 1831.

|

|

|

Sir Astley Paston Cooper,

1st Baronet (1768-1841)

English surgeon and anatomist. |

While opposition to the Railway gathered force, a detailed survey

was being carried out, sometimes in confrontation with hostile

landowners over whose estates the surveying teams had to take their

measurements. Without the force of an Act of Parliament behind

them the Company’s

surveyors had no lawful right of access to private land, which at

times made accurate surveying

difficult. Attempts at conciliation were sometimes

memorable, at least to Robert Stephenson, who was in frequent

attendance. He later recalled visiting Sir Astley Cooper, [14]

. . . .

“. . . . in the hope of overcoming his aversion to the railway.

He was one of our most inveterate and influential opponents.

His country house at Berkhamsted was situated near the intended

line, which passed through part of his property. We found a

courtly, fine-looking old gentleman, of very stately manners, who

received us kindly, and heard all we had to say in favour of the

project. But he was quite inflexible in his opposition to it.

No deviation or improvement that we could suggest had any effect in

conciliating him. He was opposed to railways generally, and to

this in particular. ‘Your scheme,’ said he, ‘is preposterous

in the extreme. It is of so extravagant a character as to be

positively absurd. Then look at the recklessness of your

proceedings! You are proposing to cut up our estates in all

directions for the purpose of making an unnecessary road. Do

you think for one moment of the destruction of property involved by

it? Why, gentlemen, if this sort of thing be permitted to go

on, you will in a very few years destroy the noblesse!’ We

left the honourable baronet without having produced the slightest

effect upon him, excepting perhaps, it might be, increased

exasperation against our scheme. I could not help observing to

my companions as we left the house, ‘Well, it is really provoking to

find one who has been made a “Sir” for cutting that wen out of

George the Fourth’s neck, charging us with contemplating the

destruction of the noblesse because we propose to confer upon him

the benefits of a railroad.’”

Life of George Stephenson and of

his son Robert Stephenson, Samuel Smiles (1862).

It was probably at this time that today’s line ― which passes

slightly to the east of Watford Town Centre and then through the

long Watford Tunnel to Hunton Bridge ― replaced the more circuitous

route that Stephenson had planned along the Gade Valley, through the Cassiobury (Earl of Clarendon) and Grove (Earl of

Essex) estates:

“It is, however, to be regretted, that the

opposition of the Earls of Essex and Clarendon should have forced

the Directors to abandon the most eligible line, which would have

passed through Grove and Cassiobury Parks, near Watford, pursuing

the line of the canal through the valley of the Gade; as, in

consequence, the public is now obliged to pass through a tunnel more

than a mile in length, and a far less advantageous route has been

adopted. Nor can the reason for this opposition be imagined;

through each of the parks the Grand Junction Canal passes; the

barges in their slow and tardy progress, interrupt their privacy,

and introduce a set of men notorious for their half-savage and

predatory habits; the Railway could have been screened from both

mansions; and the trains, passing with lightning velocity, could

not, in any way, have inconvenienced their noble owners. The

influence, however, of these noblemen was such as to induce the

Directors to abandon, for a short distance, the best and cheapest

line, rather than encounter the DELAY and expense which their

opposition would have occasioned.”

The Railway Companion, from London

to Birmingham, Arthur Freeling (1838).

Stephenson also abandoned his preference for crossing the Chilterns

through the Dagnall Gap in favour of that at Tring. [15]

These changes introduced heavier engineering work, but they avoided

the estates of the noble Earls, of the Countess of Bridgewater (Ashridge

Estate), and of Sir Astley Cooper (Gadebridge Estate), all

of whom were avowed opponents of the Railway. Further

aristocratic opposition – this time from the Duke of Buckingham –

defeated Stephenson’s plan to pass through the town of Buckingham,

where a locomotive and carriage works would have been built, and so

the line was routed further east through Linslade and Wolverton.

When the Bill was eventually laid before Parliament, much evidence

from the growing experience of railway operations was produced in

its support. As a result, its promoters believed that they had

clearly established that the need for the Railway was in the national interest. On the

1st June 1832, a large majority of the House of Commons committee

voted in favour of the Bill, but when in the following month it

passed to committee in the Lords . . . .

“. . . . a similar mass of testimony was

again gone through. But scarcely had the proceedings been opened

when it became clear that the fate of the bill had been determined

before a word of the evidence had been heard. At that time the

committees were open to all peers; and the promoters of the measure

found, to their dismay, many of the lords who were avowed opponents

of the measure as land-owners, sitting as judges to decide its fate.

Their principal object seemed to be to bring the proceedings to a

termination as quickly as possible.”

Life of George Stephenson and of

his son Robert Stephenson, Samuel Smiles (1862).

|

|

|

Railway opponent, John

Cust,

1st Earl Brownlow (1779-1853). |

. .

. . the Bill was rejected on the motion of Lord Brownlow (a trustee of

the Countess of Bridgewater, representing the Ashridge Estate), who

declared that a sufficient case had not been made to warrant “forcing”

the railway through the property of so many dissenting landowners. Thus, Lord Wharncliffe, Chairman of the Lords committee . . . .

|

“. . . . presented the Report of the

Committee on this Bill, which stated that the parties who had

applied for the Bill had, in their opinion, failed to prove the

allegations contained in the preamble, [16]

and that the Committee did not think, in those circumstances, that

they ought to proceed farther with the measure.”

Morning Post, 13th July 1832.

|

In fact Lord Wharncliffe, [17] a strong supporter

of the Bill, entertained:

“. . . . a conviction which induced the

noble Chairman of the Committee of the Lords (Lord Wharncliffe) so

emphatically to declare at the meeting of Peers, Members of the

House of Commons, and other persons favorably disposed to the

undertaking, at the Thatched House Tavern, on the 13th July, at

which his Lordship presided ―

‘He must now say upon hearing the evidence for the Bill that he was

quite satisfied that this undertaking had the character of a great

national measure,’ and

‘That of the many Bills of this description which had come before

him in the course of his parliamentary life, he had never seen one

passed by either House that was supported by evidence of a more

conclusive character.’”

Extracts from the Minutes of

Evidence given before the Committee of the Lords (1832).

|

|

|

James Archibald Stuart-Wortley-Mackenzie,

1st Baron Wharncliffe PC (1776-1845). |

This was not the first time the aristocracy had a railway bill

thrown out. The proprietors of the London and Birmingham

Railway were in company with those of our first public line, the

Stockton and Darlington, whose:

“. . . . application of 1818 was defeated

by the Duke of Cleveland who afterward profited so largely by the

railway. The ground of his opposition was that the line would

interfere with his fox-covers, and it was mainly through his

influence that the bill was thrown out . . . . The next year, in

1819, an amended survey of the line was made, and, the Duke’s

fox-cover being avoided, his opposition was thus averted.”

Life of George Stephenson and of

his son Robert Stephenson, Samuel Smiles (1862).

The sentiment expressed by the authors of Osborne’s London &

Birmingham Railway Guide summed up the feeling in the country:

“When we consider that evidence had been

laid before the committee sufficient to demonstrate to any

reasonable persons, the overwhelming national importance of the

realization of the proposed project, it will be palpable that the

opposition arose from mere selfishness, and in ignorance or contempt

and wilful violation, of the principle on which the tenure of land

is based. The stoppage of this great national undertaking was

extremely aggravating and vexatious to the public, and the placidity

and sangfroid of the mode in which it was done, was not at all

calculated to decrease the aggravation; on the contrary the

rejection was so much more galling on that account.”

|

|

North of Watford, at Two Waters,

Stephenson planned to turn the line into the Gade Valley, then

passing through Hemel Hempstead and Gaddesden, cross the ridge of

the Chilterns through the Dagnall Gap. But again resistance from

influential land owners prevailed, forcing the line to be routed

along the Bulbourne Valley and across the Chilterns through the

Tring Gap. Although the Bulbourne Valley route resulted in the long

Tring Cutting, necessary to maintain the line’s ruling gradient

(1:300), it did avoid the sharp turn at Two Waters (above) that

would have resulted from the original plan. |

――――♦――――

|

THE SECOND RAILWAY BILL

Parliamentary proceedings had so far consumed

£50,000, but such was their belief that the Railway’s construction was in the national interest

that, having revised their tactics, in October 1832 the Directors

applied to present a Bill in the following session:

“Owing to these dissentient manifestations,

and various other subsequent occurrences, it was deemed prudent to

alter the route of the proposed line, so as to interfere less with

the parks and residences of the gentry, and the comparative

advantages of a line of four and two rails attentively investigated.

In February, 1832, upwards of 19,000 shares had been subscribed for,

and £5 paid as a deposit upon each share. It was, therefore,

resolved on by the directors, after a further revision and

correction of the proposed route, and the difficulties which

presented themselves, to apply for leave to bring in their bill.”

The London and Birmingham Railway

Guide, Joseph W. Wyld (1838).

With regard to the remaining dissentient landowners, much of the

Company’s conflict with

them was resolved with the aid of their cheque book, an

effective tactic, but one that more than doubled the estimated cost of land

acquisition from £250,000 to £537,596:

“The compensations demanded from the

Company by the proprietors of land and other premises on the line of

the railway were enormous, and in many cases where no injury

whatever was done, the land valuers having made their estimates upon

the most liberal scale. All sorts of payments were required on the

most frivolous pretexts, and even some of the opponents to the bill

were obliged to be paid, in order to gain their consent to the

measure. The sum of £3000 was given for one piece of land, and the

extravagant amount of £1000 for consequential damages, when instead

of any damages being sustained the land has been improved; these and

similar transactions soon run away with all reasonable estimates;

and yet it is certain, that in every instance the best plan that

could be devised was followed to procure the land on equitable

terms, taking into consideration that to gain time was in most cases

the principal object.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe, Peter Lecount (1839).

Purchase of land from Sir William Harcourt, a Railway opponent, on

which to build Tring Station, illustrates the sort of problem the

Company encountered, although in this case there was an unusual solution:

“The former owner of the land on which the

station now stands, asked so extravagant a price for it, that the

directors determined to have the station at the far side of the

cutting, which would have been three and a half miles from Tring.

The inhabitants were much excited on the subject, and a town’s

meeting being called, a deputation was appointed to wait on the

Directors rectors to memorialize them on the subject. The

Directors when waited on by the Deputation, stated the sum they

could afford for the land; and explained that the matter being

important to the people of Tring, the Directors would willingly

erect the station at the desired place, if the people of Tring would

undertake to pay the difference between the price of the land,

according to an equitable valuation, and that demanded by the owner

of it. The parties agreed to this fair and business like

proposal . . . .”

Osborne’s London & Birmingham

Railway Guide, E. C. and W. Osborne (1840).

It was during this period that Robert Stephenson undertook his third

survey, in which he appears to have revisited the route proposed by Rennie

with the aim of weighing up its pros and cons and comparing them

with the

slightly longer route via Coventry:

“Mr. R. Stephenson and Mr.

[Thomas Longridge] Gooch spent a great deal

of time in investigating this question, examining the country, and

taking levels in all practicable directions, in order to ascertain

the merits of the line referred to. This was intended to

branch off from the present route near Tring, and leaving Aylesbury

a little to the south-west, passing near to and on the easterly side

of Bicester, thence on to Buckingham and Banbury, crossing the river

Avon between Leamington Priors and Warwick, and joining the present

line again in the neighbourhood of Hampton in Arden.

The saving in distance by this line would not have exceeded four or

five miles, and in addition to the many difficulties and expensive

works on this route the crossing of the valley of the Avon, near

Warwick was at once a fatal objection.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe, Peter Lecount (1839).

The main objection to Rennie’s proposed line was the gradient out of

the Avon Valley and across the Meriden (a.k.a. Reaves’s Green) Ridge,

which lay across the path to Birmingham. By taking the line

through a heavy cutting and tunnel at Beechwood, to the west of

Coventry, Stephenson was able to maintain the line’s ruling

gradient at 1:330 (16 feet to the mile), but crossing the Avon

Valley further south would have increased it ― or so claimed

Roscoe and Lecount ― although in his survey report of 1826, Rennie

claims that the maximum gradient of his proposed route was 14ft to

the mile, with a short section at 15ft.

While the travel writers of the day dwelt on the line’s topography,

another substantial argument in favour of the Coventry route must have been commercial, for the prospects

of picking up business from this developing industrial centre

(30,000 population in 1840) would

surely have outweighed all but major topographical problems, such as the Nene Valley, which appears to have been

the reason why

Northampton was bypassed by the Stephensons and by Giles before

them.

The plans and sections for the second application corresponded as

nearly as possible with those prepared in the preceding year, the only

alterations being a slight change between Harrow and London and the

re-siting of the London terminus near the railway’s intersection

with the Regent’s Canal at Camden Town.

Little is recorded about the second Bill’s passage through Parliament.

Perhaps the sweeteners paid to landowners had their effect, but the

weight of support for the scheme in the country probably had a

deterrent effect on those who might have opposed the scheme through

personal prejudice, rather than for important reasons of general

application. Osborne

described the national feeling following the first Bill’s rejection

thus:

“The stoppage of this great national

undertaking was extremely aggravating and vexatious to the public,

and the placidity and sangfroid of the mode in which it was done,

was not at all calculated to decrease the aggravation; on the

contrary the rejection was so much more galling on that account.”

Osborne’s London &

Birmingham Railway Guide, E. C. and W.

Osborne (1840).

Suffice it to say that the London and Birmingham Railway Act passed

the Commons Committee on 15th March, the Lords on 22nd April, and

it received the Royal assent on the 6th May, 1833 (at a cost of

£72,869).

Cap xxxvi

An Act for making a Railway from London to Birmingham

[6th May 1833].

WHEREAS the making a Railway, with proper

Works and Conveniences connected therewith for the Carriage of

Passengers, Goods, and Merchandize from London to Birmingham, will

prove of great public Advantage, by opening an additional, cheap,

certain, and expeditious Communication between the Metropolis, the

Port of London, and the large manufacturing Town and Neighbourhood

of Birmingham aforesaid, and will at the same Time facilitate the

Means of Transit and Traffic for Passengers, Goods, and Merchandize

between those Places and the adjacent Districts, and the several

intermediate Towns and Places: And whereas the King’s most Excellent

Majesty, in right of His Duchy of Cornwall, is entitled to certain

Lands upon the Line of the proposed Railway: And whereas the several

Persons herein-after named are willing, at their own Costs and

Charges, to carry into execution the said Undertaking; but the same

cannot be effected without the Authority: of Parliament May it

therefore please Your Majesty that it may be enacted; and be it

enacted by the King’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the Advice

and Consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in

Parliament assembled . . . . .

CHAPTER

5

――――♦――――

|

|

APPENDIX I.

Some requirements to be met in applying for a

Private

Act of Parliament.

From The London and Birmingham Railway Guide,

Joseph W. Wyld (1838).

“Every public railway in the United Kingdom, is commenced, carried

on, and completed under the authority of a special act of

parliament, which can only be applied for, and obtained by a

compliance with certain conditions specified in the standing orders

of the Houses of Lords and Commons. The following is a cursory

abstract of the parliamentary requisites and injunctions relating to

Railway Bills.

Previously to applying for leave to bring in a bill, the Company

must have advertised their intention a stated number of times,

during particular months of the year, in the London Gazette, and

newspapers of the counties traversed by the intended line. To

the various owners of land through which it is intended to carry

such railway, notices and specifications of the manner of its

construction, at those particular spots, must be forwarded in

writing. Plans of the whole length of the line, drawn to a

scale of four inches to a mile, and enlarged drawings of buildings,

gardens, &c., on a scale of a quarter of an inch to every 100 feet,

together with a section of altitudes, and a book of reference to the

whole, must be deposited with certain official persons.

One-half of the amount of the estimated expense of constructing the

railway must have been subscribed, and a bond entered into by

certain persons, for themselves, heirs, and assigns, to insure the

payment of such subscription. Before reading the bill a third

time in the House of Commons, it must be satisfactorily proved that

three-fourths of the capital have been deposited; and before the

third reading in the House of Lords, that five-sixths have been

deposited.

During the progress of the bill, any owner of land, or other person,

who considers himself likely to be directly and substantially

injured by the intended railway, may claim to be heard, by counsel,

before the select committee of the house, who are ever ready to

investigate any claim, or listen to any argument, which may be

brought forward to prove the inutility of such railway, or the gross

injustice which will accrue from its adoption.

The bill having been obtained, the only material obstacle to the

commencement of the works, is the fair remuneration to those

land-owners whose property is directly affected by the route of

line. The difficulty of properly assessing and adjusting such

remuneration, varies, of course, according to the neighbourhood and

situation of the soil, and depends, also, in some degree on the

disposition of the party to be remunerated.

From the above epitomical remarks, it will be obvious, that the

preliminaries necessary to the commencement of any intended railway,

render the subsequent practicability of such intention a subject of

serious deliberation, and such an one as requires the advice and

counsel of the most eminent of all professions, in order to

ascertain its probable value, not only as an individual, but also as

a great national benefit.”

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

Sir John Rennie’s report on the survey undertaken by

Messrs. John and Edward Grantham during 1824 and 1825.

From The Railway Magazine, Vols. I. (1836) &

II (1837).

Birmingham, 1st April, 1826.

Gentlemen,

In consequence of your resolutions of January, 1824, directing me to

explore and survey the most practicable route for communication by

means of a railway between London and Birmingham, I directed Messrs.

John and Edward Grantham to explore the intervening counties and

take the necessary levels for this purpose, and the whole of the

spring and the greater part of the summer of last year was employed

by them in making various trials through the country; but on account

of the extensive and intricate nature of the survey, comprehending a

district of above 130 miles, it was scarcely possible to complete

this work in an effectual manner until the autumn following, when

you determined not to proceed to Parliament this session (indeed the

extended nature of the subject rendered this scarcely practicable).

I should certainly have reported to you my opinion upon the progress

made before, but have been prevented by illness from examining the

line until the present.

I now beg leave to apologise, and report my opinion upon the various

trials and sections that have been made, although I am still in

hopes that, in the event of your prosecuting the scheme, further

improvements may be made, until the line becomes almost

unexceptionable.

By referring to the accompanying plan and sections it will be seen,

that the line commencing at the Islington tunnel of the Regent’s

Canal rises 10 feet to the mile for 3 miles, and continues from

thence nearly parallel to it, and skirting Regent’s Park pursues a

tolerably direct line until arriving at the Edgeware-road, a

distance of 3, miles rising 30 feet, or 10 feet to the mile; but to

obtain these inclines considerable obstacles must be encountered,

namely, two miles of 23 feet of average cutting from the Hampstead

to the Edgware road. The property, moreover, here is extremely

valuable, and mostly laid out for building ground, and several

nearly new houses must be sacrificed; indeed, here, the greatest

part of the difficulty occurs; but by assuming steeper inclines and

taking a wider range of London, a considerable portion of these may

be avoided, or the line may be stopped at the Edgeware road for the

present; from thence to the river Brent, a distance of 4 miles, the

line continues rising 16 feet, two of which are level, the remainder

rising 8 feet to the mile; to obtain this it will be necessary to

embank about ¾ of a mile, averaging 9 feet high, and for ½ a mile

over the Brent, averaging 30 feet high, the remaining distance of 2¾

miles being little more than surface forming.

Thence the line takes a direction to the east of Harrow and by

Harrow Weald, and crossing the road to Rickmansworth, a distance of

8½ miles rising 14 feet to the mile in this division, except the

cutting at Oxley-lane, which will average 28 feet high for a quarter

of a mile, little more than surface forming and some small pieces of

cutting and embankment will be necessary, nor will any gentleman’s

park or pleasure grounds or other valuable property be affected by

it; from thence to Otter’s Pool [Otterspool], a distance of 4 miles,

the line continues level, passing to the east of Pinner-wood, and

crossing the turnpike road about ¼ of a mile from the town of

Watford, and without interfering with any valuable property; in this

division the levels are rather irregular, although the cuttings and

embankments are by no means serious. The total distance from

London is 18 miles, and the distance by the turnpike road is about

the same.

From Otter’s Pool to Hunton bridge, a distance of 3½ miles, the line

continues rising at the rate of 15 feet to the mile crossing the

vale of the Colne by a heavy embankment ¾ of a mile long averaging

30 feet high, and a piece of heavy cutting at Leavesiton-green [Leavesden

Green], averaging 50 feet high for ¾ of a mile; these no doubt are

serious obstacles, independent of the circuitous course. The

town of Watford however and the park and pleasure grounds of the

Earl of Essex intervening, render it almost impracticable to obviate

these difficulties entirely, although I have reason to believe that

by increasing the inclines, it may be materially improved.

Finding the articles abovementioned, and wishing at the same time to

avoid the Grand Junction canal, I directed Mr Edward Grantham to

pursue the course of the St. Alban’s Valley; this, however, proved

to be unsuccessful, as the high lands beyond St. Alban’s would have

rendered its further continuance almost impossible at any reasonable

expense.

From Hunton bridge to the summit at Dagnall, a distance of 11¾

miles, the line continues rising gradually at the rate of 12 feet to

the mile, passing to the north of Abbot’s Langley, Hemel Hempstead,

and Gaddesdon, but in order to preserve the above mentioned gentle

inclination, it was necessary to keep the line as near as possible

hanging upon the sides of the adjoining hills, the section in

consequence shows generally a rugged and an uneven surface, on

account of the numerous ravines which constantly run down from the

main chain of hills, the cuttings and embankments for 6 miles, to

Pitchett’s End, although apparently heavy as shown upon the section,

are nevertheless of short duration; near Gaddesdon, Gaddesdon Park

intervenes, and cannot be entirely avoided without much difficulty,

although, as the line here nearly skirts that part adjoining the

road, I should not apprehend any reasonable objection; with this

exception no other valuable public or private property is interfered

with, indeed the country generally is extremely open and the land by

no valuable: by increasing the inclination in some places to 15 and

others 20 feet to the mile, the whole of this district may be

improved and shortened.

At Dagnall the summit must be passed by a piece of heavy cutting,

averaging 28 feet for one mile long.

The line continues by Eddesborough (Edlesborough?) to Cheddington

being 5½ miles, descending at the rate of 14 feet to the mile, the

cuttings and embankments in this division being entirely along the

points of the adjoining ridge of hills are not serious, although

apparently so upon the section, and being chiefly composed of chalk

would stand at very small slopes, and by increasing the inclination

here to 16 feet to the mile, about ten feet of cutting might be

saved at the summit, and about a quarter of a mile in the distance.

At Cheddington the line crosses the Grand Junction Canal at an

elevation of 18 feet, and continues descending 12 feet to the mile

for 8¼ miles to Weedon, and passes to the south of Wingrave and

Bunton, about three miles to the north of the town of Aylesbury, to

which a descending branch can readily be made. In this

division no particular obstacle intervenes, except a small valley

near Mentmoor, which must be passed by an embankment of 12 feet

average for three quarters of a mile.

From Weedon to Aylesbury there is a descent of about 30 feet, which

might be readily approached with a branch from the Main line, and as

this is a place of considerable importance, this might be well

worthy of consideration. From Weedon to a place called

Whitefield Farm, the line continues level for 3 miles without any

material obstacle. The Thames [The Thame?], which is much

subject to floods, must be crossed by a considerable bridge and a

small piece of cutting and embankment.

From thence to Quainton Mill, a distance of three miles further, the

line continues rising gently at the rate of 10 feet to the mile,

with little more surface forming, and without interfering with any

valuable property. By referring to the accompanying plan and

sections, it will be seen that this line by the Dagnall summit is

rather circuitous, on account of being compelled to keep so far to

the northward. I consequently directed Mr. John Grantham to try the

line by the Bickampstead [Berkhamsted] and Tering [Tring] Valley,

which is already occupied by the Grand Junction Canal; from thence

by Drayton, Bearton, Aylesbury, to Quainton where it joins the

former line: this certainly saves about 2 miles in the distance, but

would be attended with a heavy piece of cutting of 30 feet for near

two miles [the Tring Cutting], and would partially interfere with

the Reservoir and works of the Grand Junction Canal, which no doubt

would render it objectionable to them; from thence however to

Aylesbury, and even Quainton, no difficulty occurs. The

distance from London to Quainton by the turnpike road is 47 miles,

and by the railway section as laid down, 52 miles, being an increase

of 5 miles by the latter; but when the moderate inclinations which

have been adopted are considered, and that no private parks,

pleasure grounds, or other valuable property have been interfered

with, I trust, that so far the line upon the whole may be considered

favourable, and is still capable of further improvement, by adopting

the alterations abovementioned.

Several other minor trials were made in the vicinity of the above,

but as they proved abortive, it is not worth while to enumerate

them. I also directed a line to be tried from Chesham,

immediately above Uxbridge, to continue up the Amersham valley to

Wendover and Aylesbury: this summit, however, proved to be 90 feet

above that of Teing [Tring] and would have required an inclination

of at least 30 feet to the mile, and an inclined plane and heavy

cutting to Aylesbury: the distance, moreover, would be increased. I

consequently abandoned this attempt as fruitless.

From Quainton Common the line continues by Dodders hall to near

Knoll Hill, a distance of 3 miles, falling 30 feet or 10 feet to the

mile. In this division there are several sharp pieces of equal

cutting and embanking, averaging 12 feet for one mile and a half;

from thence to the Chamdon and Twyford-road the line continues 3

miles further, rising 18 feet, of which the first mile rises 10

feet, and the other two 4 feet each; and these levels or

inclinations are obtained without any difficulty ― indeed little

more than surface forming is required.

From Twyford-road to the Goddington-road, a distance of two miles

and a-half, the line rises 20 feet, and will require an equal series

of cuttings and embankments for about 6 feet upon the average; from

thence by a place called Fringford Mill over the high grounds of

Shelnwell to Mixborough, a distance of 5 miles, the line rises 70

feet, or 14 feet to the mile division, the chief obstacles are a

small valley near Goddington, which will require an embankment of 8

feet for a quarter of a mile, a piece of cutting through the side of

Saul’s Mills, averaging 17 feet high for a quarter of a mile, an

embankment 3 furlongs 27 feet high; and the valley over off the

Goddingon river, one of the principal feeders of the Ouze in this

embankment, a bridge about 30 feet wide will be requisite, and a

considerable piece of cutting, near two miles through the high

grounds of Shelswell, averaging 16 feet high: an inclination,

however, of 20 feet to the mile will reduce this latter piece of

cutting to little more than surface forming.

From Mexborough to the village of Evenly, a distance of 2 miles, the

line rises 11 feet, with a trifling piece of cutting and embanking

of about 15 feet for seven chains long. From thence to Heyne

through the village of Hinton the line continues level for 3 miles,

leaving Brackley about a quarter of a mile to the right. In this

division there is no particular obstacle, but a heavy piece of

cutting at Gretworth, averaging 25 feet for a quarter of a mile,

which cannot well be avoided in this direction, as it is the lowest

part of the ridge of hills which divide the summit of the Ouze from

the Charwell: from thence to the ridge north of Middleton Chenny,

the line continues rising 33 feet for 2 miles, and 2 furlongs,

requiring a piece of cutting averaging 12 feet for half a mile.

Here the country becomes difficult and rugged; and in order to cross

the ridge, and to descend into the vale of the Charwell, a heavy

piece of cutting averaging 35 feet for three furlongs must be

encountered.

The line continues through this by the villages of Chalcombe and

Wilscot, being a distance of 5 miles, 1 furlong, and falling 74

feet, or nearly 15 feet to the mile. On account of the

intricate nature of the country, surrounded on all sides by high

hills, and intersected by deep valleys, the line is necessarily

rather circuitous, and attended by alternate cuttings and

embankments, although these being mostly along the points of hills,

will not be so serious in the execution as represented in the

section.

From the river Charwell to a small valley and water course the line

falls 9 feet in two miles. In this division the only obstacle is the

valley of the Charwell, which must be crossed by an embankment and

bridge, for which an excellent quarry is expected to be found in the

heavy piece of cutting near Middleton Chenny; the remainder will

require little more than surface trimming and forming: from thence

to the entrance of the Oxford Tunnel [formerly Fenny Compton Tunnel

on the Oxford Canal, now a cutting], the line rises 33 feet in 2

miles and three quarters, through a very favourable country.

From the Oxford Tunnel [north of Banbury] the line passes by Fenvy,