|

|

NOTES

AND EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

CHAPTER

10

CONSTRUCTION

―

TRACK AND SIGNALLING

THE PERMANENT WAY

“I would here remark, that when competition

was developing the present high velocities upon railways, generally

Mr. Robert Stephenson gave it in evidence as his opinion, that the

limit would be found, not in any particular gauge, or in the

evaporating power of the engines, but in the economic endurance

of the permanent way to bear the additional weight which must, as a

matter of necessity, accompany every increase of speed. Time

is, in my opinion, rapidly demonstrating the truth of this

observation.”

From a Report by R.B. Dockray,

Engineer to the LNWR, 23rd August 1848.

Picture

Bermicourt

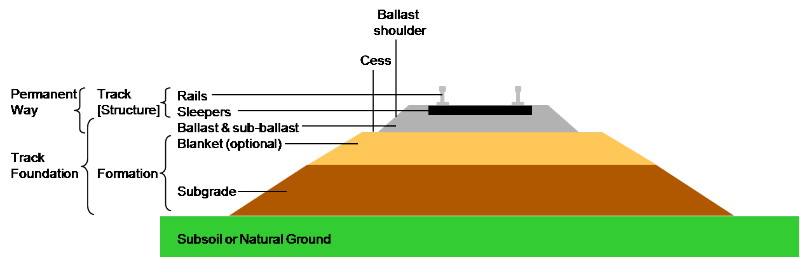

The term

‘permanent way’ originated in the early days of mainline railway

construction. Contractors laid temporary track on which to run the

earth wagons that they used to remove spoil from excavations and

carry it onto embankments being formed. This lightweight track

could easily be slewed into different positions to better

accommodate their operations as they progressed. When the work was

complete, the ‘contractor’s way’ was dismantled and moved

elsewhere. Ballast was then spread over the trackbed to provide

support and drainage, and onto this was laid the railway. The

rails, fasteners, sleepers and ballast that was to carry the railway

company’s traffic became known as the ‘permanent way’, despite

each of these components being anything but permanent, their

lifespan depending on factors such as the type and volume of

traffic, atmospheric conditions, curves and braking conditions.

Today the

dominant form of track consists of flat-bottom welded steel rails [1]

of uniform cross-section supported on timber or pre-stressed

concrete sleepers laid on crushed stone ballast. This position was

only reached after many years of experiment and development. Today the

dominant form of track consists of flat-bottom welded steel rails [1]

of uniform cross-section supported on timber or pre-stressed

concrete sleepers laid on crushed stone ballast. This position was

only reached after many years of experiment and development.

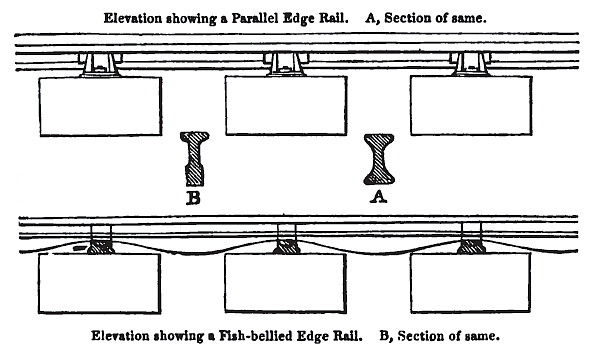

The first breakthrough came in 1820, when John Birkinshaw of

Bedlington Ironworks in Northumberland developed rolled wrought iron

fish-bellied rails in 15 feet lengths. They were strong enough to

bear the stresses imposed by a locomotive hauled train ― which

earlier brittle cast-iron rails, even in shorter lengths, were not

― and they marked the beginning of the modern rail era. Rails of

the Birkinshaw type were used on the Stockton and Darlington and the

Liverpool and Manchester railways:

“The material of which the Rails were to be

composed, whether of cast or forged iron, was a matter of some

importance. Each description of Rail has its advocates; but after

due consideration and enquiry into their respective merits, the

Directors [of the Liverpool and Manchester railway]

determined to adopt the forged or rolled iron Rail, in lengths of

five yards each . . . . A similar Rail is used on the

[Stockton and] Darlington way, but somewhat

lighter; the Darlington Rail weighing 28lb., and the Liverpool and

Manchester 35 lb., per lineal yard. The Rails are supported every

three feet, on stone blocks, each block containing nearly four cubic

feet of stone. Two holes, six inches deep, and an inch diameter,

are drilled in each block, and into these are driven oak plugs, and

the cast-iron chairs or pedestals to which the Rail is immediately

fitted and fastened, are firmly spiked down to the oak plugs,

forming altogether a construction of great solidity and strength.

On the embankments, where the foundation may be expected to subside,

the Rails are laid on oak sleepers.”

Remarks on the Comparative

Merits of Cast Metal and Malleable Iron Railways,

Longridge and Birkinshaw (1832).

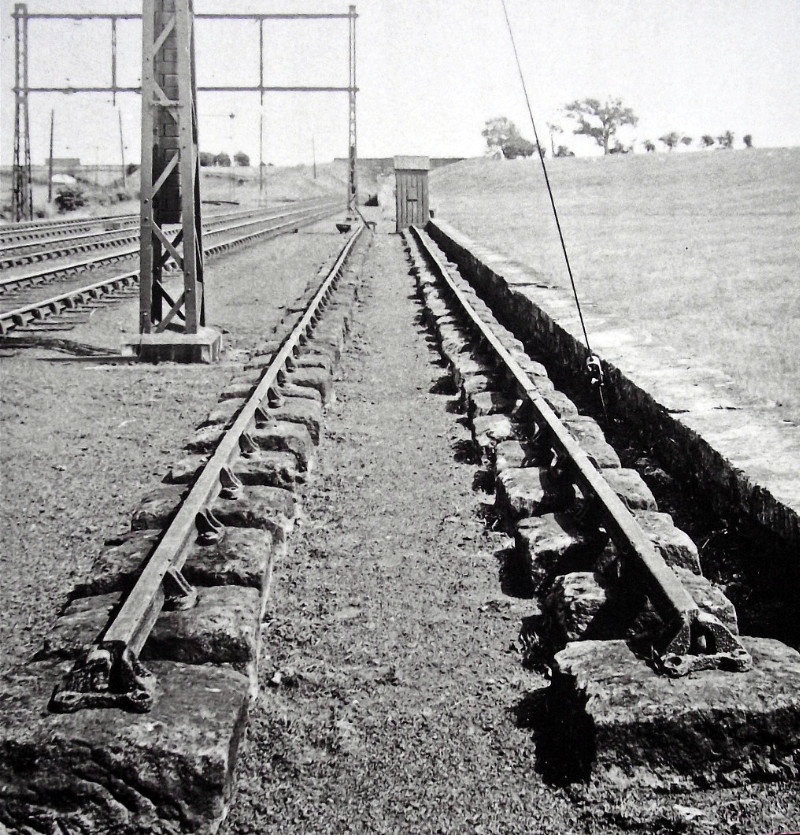

A section of fish-bellied

rail on stone block sleepers, Stockton & Darlington Railway.

Darlington Railway Museum.

Horse-drawn wagonways had used rails mounted on rows of stone

blocks, but without any cross ties between them to maintain the

correct gauge (unnecessary for light, slow-moving traffic). The use

of blocks left a clear path for the horses’ hooves, which would have

been denied them had transverse wooden sleepers been put down,

unless they were buried in the ballast where they would have been

more prone to rot. And so the builders of the first public

locomotive-worked railways, Robert Stephenson among them, followed

the wagonway model. Joseph Locke was a notable exception. [2]

Locke, Engineer to the Grand Junction Railway, [3]

realised that locomotive traction required a degree of flexibility

in the track that stone blocks did not provide, but that transverse

wooden sleepers laid at intervals did. Furthermore, the stresses

imposed on the track by much heavier, faster moving traffic,

required the rails to be held firmly to gauge ― wooden sleepers met

this requirement much more readily than stone blocks, which traffic

gradually eased out of gauge unless the blocks were fitted at

intervals with metal tie rods.

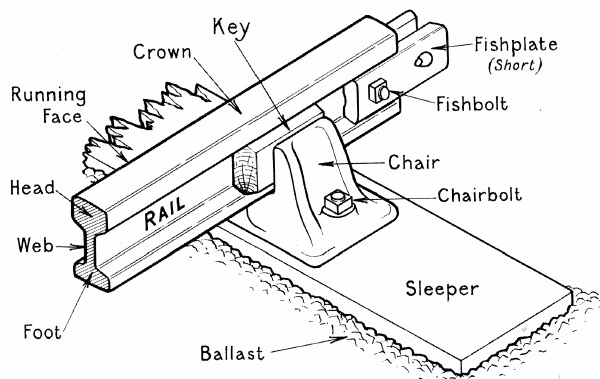

Rails fastened in iron

chairs laid on stone block sleepers.

There were other disadvantages associated with stone block

sleepers. The impact of train wheels against their unyielding

surface caused the rails to shake loose in their supporting chairs;

their lack of elasticity provided a train’s passengers with an

uncomfortable ride ― as one contemporary commentator put it, “The

clatter caused by the stone blocks, which were used before the

wooden sleepers replaced them, added to the unpleasantness of the

journey” ― and, generally speaking, they were more expensive

than wood. However, one problem that did not affect stone was rot,

which was probably an important factor in its choice.

During the construction of the London and Birmingham Railway, the

preparation much in vogue for protecting timber against rot was that

discovered by John Howard Kyan and first patented in 1832:

“Kyan’s Patent Preparation ― a process of

preserving timber from the dry rot, recently invented by Mr. Kyan,

consisting of a solution of corrosive sublimate [mercuric

chloride], in which the timber is immersed,

whereby the primary element of fermentation is neutralized, and the

fibre of the wood rendered indestructible. It also effectually

seasons the timber, occupying a space of only two or three months

instead of from two to six years, which is usually consumed in

laying it to dry, by the common method; and it also protects it from

the ravages of insects. The preparation has become generally

employed for railway sleepers, and for all timbering employed in

engineering works, which from their exposure to the weather are very

liable to premature decay.”

A Glossary of Civil Engineering,

S. C. Brees (1844).

The claims made in favour of ‘kyanizing’ were such that many

railways built at the time applied it to their sleepers. However,

the solution was highly poisonous, the process was expensive and, if

not applied properly, its efficacy was limited or neutralised.

Nevertheless, kyanizing was considered the best rot preventive then

available and, despite its drawbacks, it was used on those sections

of the London and Birmingham Railway laid with wooden sleepers.

These were mainly embankments and other sections where the formation

was more likely to settle when under load:

“On embankments transverse sleepers of

Scotch fir, larch, and oak, are used as the foundation for the

rails; and in cuttings, stone blocks; but on many parts of the line

sleepers have been substituted to a great extent. The are 7 feet in

length, having a scantling of 9 inches by 5 inches; the cost is

about 7s. each, exclusive of kyanizing, which adds 9d. additional to

each sleeper.”

The London and Birmingham permanent

way,

from The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland, Wishaw

(1842).

However, the results obtained from the process were mixed. On the

Great Western Railway it was found to be satisfactory, but on the

London and Birmingham it was not, and was soon discarded:

“With reference to the durability produced

by this process, accounts are somewhat contradictory. How far

success in this respect may be owing to careful and complete

performance, or, on the other hand, failure be promoted by careless

and incomplete Kyanizing, we have no means of determining. Upon the

application of the process for the Great Western Railway, it was

reported in August, 1843, that a part taken from the centre of one

of the longitudinal timbers forming the base of the railway which

had been Kyanized six years before, was as sound as on the day on

which it was first put down . . . . On the London and Birmingham

Railway, on the contrary, the engineer reported, that the sleepers,

which were all Kyanized, were, after lying three years, found to

exhibit symptoms of decay, ― that many of them had been

removed absolutely rotten, and Kyan’s process had been consequently

abandoned.”

Professional Papers of the Corps

of Royal Engineers (1845).

Kyanizing gradually fell out of favour after a patent covering the

use of ‘creosote’ [4] to treat timber was taken

out by John Bethell in 1838. The ‘Bethell process’ involved sealing

timber in a pressure chamber and then applying a vacuum to remove

air and moisture from its cells. The timber was then

pressure-treated in order to impregnate it with the preservative,

following which the vacuum was reapplied to separate the excess

solution from the timber:

“This process has been adopted by the

following eminent engineers, viz. Mr. Robert Stephenson, Mr. Brunel,

Mr. Bidder, Mr. Brathwaite, Mr. Buck, Mr. Harris, Mr. Wickstead, Mr.

Pritchard, and others; and has been used with the greatest success

on the Great Western railway, the Bristol and Exeter railway, the

Manchester and Birmingham railway, the North Eastern, the South

Eastern, the Stockton and Darlington, and at Shoreham Harbor; and

lately, in consequence of the excellent appearance of the

prepared sleepers, after three years exposure to the weather, an

order has been issued by Mr. Robert Stephenson, that the sleepers

hereafter to be used on the London and Birmingham railway are to be

prepared with it before being put down.”

Recent improvements in arts,

manufactures, and mines, Andrew Ure (1845).

Fortuitously, creosote became established as an affective rot

protection agent at much the same time that wooden sleepers were

replacing stone blocks for supporting rails:

“I find, as a general result, that stone

blocks are not adapted to high speeds, ― they are rigid, the chairs

cannot be retained firmly upon them, and from this cause they are

subject to rapid wear; and as they are in this district very

expensive in first cost, I should recommend their being renewed with

sleepers.”

From a Report by R. B. Dockray,

Engineer to the LNWR, 23rd August 1848.

The

Company was then faced with the task of disposing of many thousands

of tons of redundant stone blocks, which, according to Lecount, had

cost the Company dear:

“The stone blocks for the whole line may be

estimated at 152,460 tons, and their cost at £180,000; the expense

being pretty nearly divided into three parts ― viz., one-third for

the cost of stone, one-third for freight to the Thames, and the

remainder for delivery on various parts of the works.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Roscoe and Lecount (1839).

|

|

Redundant stone block sleepers in use

as a boundary marker

outside the Pheasant public house at

Tring.

|

|

|

“The difficulties, which attended the use

of stone blocks at length led to the substitution of wooden

sleepers, which have now almost altogether superseded them. The

traveller on the London and Birmingham line may notice, at

intervals, extensive piles of the blocks which have been removed,

any number of which may be purchased for about eighteen pence each.

Wooden sleepers are now almost universally employed, and they

serve at once as a support for the chair and rails, and as ties for

keeping the line in gauge.”

Our Iron Roads, F. S. Williams

(1852).

Today, many of the Railway’s former stone sleepers can be seen in

use as coping stones along the banks of the nearby Grand Junction

Canal. Some found their way into more domestic and decorative

applications, such as Abbot’s Hill House (King’s Langley), once home

to the paper magnate John Dickinson, which is built with redundant

blocks, and the attractive granite boundary markers fronting the

Pheasant public house at Tring (above).

The use of stone blocks undoubtedly led to significant wasted

investment, which Locke, then building the Grand Junction Railway,

managed to avoid to a great extent. [5] But

problems with the Railway’s permanent way did not rest solely on the

question of sleepers. The use of fish-bellied rails was another

instance of obsolete technology being employed, [6]

while the correct spacing of the supporting chairs (and hence of the

blocks or sleepers) became yet a further problem:

“The next [General]

meeting was in August 1835. The money then expended was £639,051;

and eighty-six miles of the railway were let to contractors, below

the estimates of the engineer-in-chief, and two-thirds of the whole

land purchased. This was the season of brightness and hope; no

reverses had come on, and all was sunshine and harmony, except

the unfortunate discussions on the rails question.”

The History of the Railway

Connecting London and Birmingham, Peter Lecount (1839).

|

|

Although

Lecount does not state it explicitly, he nevertheless gives the

impression that on the question of rails the exchange of views

between Stephenson, the Board, and their consultants, may have been

frank.

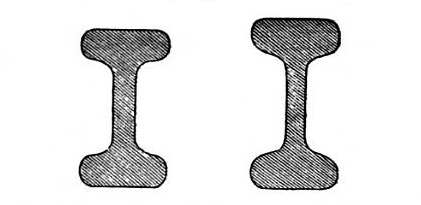

Fish-bellied line showing (in plan)

the half-lapped joint between the rails.

|

|

|

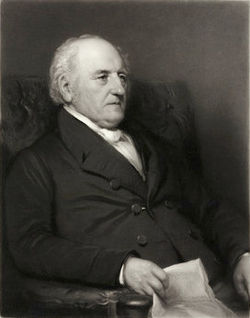

Peter Barlow FRS

(1776-1862),

mathematician and

physicist. |

The

Railway was originally to be laid on the same plan as that adopted

by the Liverpool and Manchester Railway ― wrought iron, fish-bellied

rails of 50 lbs. per yard (Liverpool first used 35 lbs.) laid mostly

on stone blocks, the supporting chairs being set at 3 feet intervals

and the joints between the rails being half-lapped. The chairs were

to be of Stephenson’s patent design.

At an early stage in construction some Board members became

dissatisfied with Stephenson’s plan for the track. The reason for

this is unclear, but as the debate that later took place on sourcing

locomotives for the line centred on objections to Stephenson

receiving royalties for the use of his Patentee class ― and

led to the use of Edward Bury’s engines ― it is possible that the

same objection (among others) applied to the use of his patent rail

chairs:

“The London and Birmingham Railway Company,

after a long discussion, decided to try four and five feet

[chair spacing] with a parallel form

instead of a fish-belly, which, requiring one third more height in

the chair, had in addition to other disadvantages, that of being

more liable to wring the chair from the block, which is found in

practice to take place directly as the height of the chair. The

block is also more loosened in the ground by a high chair, and the

continual repairs arising from this loosening, amount to one-half

the wages expended in repairing the way in general; hence every

means of diminishing such a heavy item, which can possibly be

devised, should he put in practice. As usual, where all was

theory, there were considerable diversities of opinion . . . .

. . . . On the Primrose Hill contract, which was laid with four-feet

bearings, it was found much more troublesome to keep the permanent

way in order, than with bearings of three feet. With the four-feet

bearings, it was found, that, in a very short time, the rails were

put out of gauge, the width continually increasing, until it became

absolutely necessary to readjust the whole. This was observed in a

very marked manner with a part of the line near KiIburn, which had

been recently laid down.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Explaining Their Construction, Peter LeCount (1839).

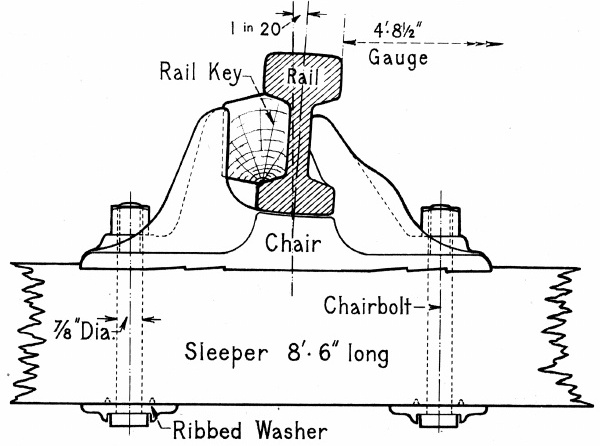

Stephenson’s

patent chair.

From A Glossary of Civil Engineering,

S. C. Brees (1844).

Whatever the cause of the Board’s dissatisfaction with Stephenson’s

plan, the outcome was a competition, with a prize of 100 guineas

going to the person who could devise the best design of track . . .

.

“The Board of Directors of the London and

Birmingham Railway Company, desirous of carrying on the great work

in which they are engaged on the most scientific principles; and, if

possible, to avoid the enormous cost of repairs which has attended

some large works of a similar description, offered, by public

advertisement, a prize of one hundred guineas ‘for the most improved

construction of Railway Bars, Chairs, and Pedestals, and for the

best mariner of affixing and connecting the Rail, Chair and Block to

each other, so as to avoid the defects which are felt more or

less on all Railways hitherto constructed;’ stating, that their

object was to obtain, with reference to the great momentum of the

masses to be moved by locomotive Steam Engines on the Railway:

1. The strongest and most economical form of Rail.

2. The best construction of Chair,

3. The best mode of connecting the Rail and Chair; and also the

latter to the Stone Blocks or Wooden Sleepers. And that the Railway

Bars were not to weigh less than fifty pounds per single lineal

yard.”

Experiments on the transverse

strength and other properties of malleable iron, Peter Barlow

(1835).

The Board engaged three judges to select the winning entry from

among the schemes submitted; J. U. Rastrick and Nicholas Wood were

both civil engineers (and former judges of the Rainhill locomotive

trials), while Peter Barlow was a distinguished mathematician and

physicist who held an appointment at the Royal Military Academy,

Woolwich:

“We met

accordingly in London; and after a long and careful examination of

the several plans, drawings, and written descriptions, recommended

those we thought entitled to the prize, which was awarded by the

Directors accordingly. But that part of our instructions which

required us to recommend one or more rails for trial, we were unable

to fulfil to our satisfaction principally for want of data to

determine which of the proposed rails would be strongest and

stiffest under the passing load, and whether permanently fixing the

rail to the chair, for which there were several plans, would be safe

in practice. No experiments on malleable iron having ever been made

bearing on these points, it was considered better to leave the

question unanswered, than to recommend, on no better ground than

mere opinion, an expensive trial which might ultimately prove a

failure.”

Experiments on the transverse

strength and other properties of malleable iron, Peter Barlow

(1835).

Following the competition, a Company meeting was held in Birmingham

at which Barlow was commissioned to undertake further research into

the strength of various types of rails and supports, and to make

recommendations. The result was a series of tests; some, carried

out under laboratory conditions at Woolwich Dockyard, aimed to

establish the strength of various types of iron bars, while in

others, carried out on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, Barlow

measured the extent to which rails were deflected by passing traffic

under different conditions.

Barlow published his results during 1835. [7] To

the layman at least, neither ― particularly the second ― is a model

of clarity, but according to Francis Wishaw they were influential in

determining the form of track:

“The rails originally introduced on this

line were of the fish-bellied form, weighing about 50 lbs. to the

yard, a few of which still remain at Kensall Green and Watford; but

Professor Barlow’s report to the Directors of this Company

completely set this question at rest, and now fish-bellied rails are

almost discarded. The larger proportion of this way is laid with 65

lbs. and 75 lbs. parallel [i.e. uniform cross

section] rails in 15 feet lengths; the

bearings for the parallel rails being 3 feet 9 inches and 4 feet

respectively. The rails are fixed in chairs of ordinary form, and

secured thereto by compressed wooden keys, according to the now

generally adopted plan . . . . The intermediate chairs weigh each

26½ lbs., and the joint chairs 31lbs.”

The Railways of Great

Britain and Ireland,

Francis Wishaw (1842).

In

his account, Wishaw fails to mention that the Directors originally

decided to position the chairs at much wider intervals, but this did

not work in practice. The problem was not that the rails failed to

sustain the load on a wider bearing, but that the stone blocks

failed to sustain the outward thrust and were pushed out of gauge.

The original spacing had, therefore, to be reinstated . . . .

“. . . . the parallel rails laid down on

the Grand Junction, and the London and Birmingham railways. The

left hand one is sixty-four lbs. per yard on the London and

Birmingham, and sixty-two lbs. per yard on the Grand Junction. The

right hand one is the London and Birmingham seventy-five pound

rail. Rails of this kind are laid on seventy-five miles of that

railway, and were intended to be at five feet bearings, but proved a

complete failure at that distance, which had to be reduced to three

feet nine inches. The left hand one was intended to be at four feet

bearings. These rails were laid down contrary to the opinion of

the engineer, Mr. Stephenson, and have entailed a vast expense on

that company. They have wooden wedges.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Explaining Their Construction, Peter LeCount (1839).

It is interesting to note in Lecount’s record of events (which

contain a hint of ‘I told you so’) that the Directors, rather

than Stephenson, were in the driving seat; but as considerable

savings in the cost of sleepers, chairs &c. and labour were to be

had by adopting a wider chair spacing, it is, perhaps, unsurprising

that on this the money men took control:

“As usual, where all was theory, there were

considerable diversities of opinion. Those who wish to enter more

at large on this subject, may consult Professor Barlow in favour of

lengthening the bearings, and Lieutenant Lecount against it. As the

matter has had a fair trial, it is only necessary here to state the

results.

On the Primrose Hill contract, which was laid with four-feet

bearings, it was found much more troublesome to keep the permanent

way in order, than with bearings of three feet. With the four-feet

bearings, it was found, that, in a very short time, the rails were

put out of gauge, the width continually increasing, until it became

absolutely necessary to readjust the whole. This was observed in a

very marked manner with a part of the line near KiIburn, which had

been recently laid down.

On the Harrow contract, from the crossing of the Harrow road to No.

12 cutting, the permanent road was used for conveying away the

material from a side cutting. The traffic was of course

considerable, but not by any means such as to account for the

absolute difficulty which the contractors had in keeping the railway

in gauge. They were obliged to put sleepers at the joints in

addition to the regular number of blocks, which of course kept the

rails in gauge at those points; but notwithstanding this, the

intermediate blocks moved outwards . . . .

On the Berkhamsted contract, where five feet bearings were in use,

and where a locomotive engine was at work, the contractors made

heavy complaints of the greater difficulty they had experienced in

keeping the rails in gauge than there was with the shorter

bearings. In fact, in the eighteen months prior to June 1837, the

three-feet rails in some parts of the line, had more work than they

now have, where the line is open; yet they stood it well, whilst the

five-feet have been so put out of gauge by one day’s work, that the

waggons had to be stopped till one and two additional sleepers for

each five feet could be laid down, and even then they were but

indifferent; and similar complaints having come in from other

quarters, together with the fact that the five-feet bearings on the

Liverpool and Manchester railway were found to cost double the sum

for keeping the way in repair that was required with three feet nine

inches bearings, the whole question had to be opened again, and

the directors resolved to shorten the bearings from five feet to

three feet nine inches.

This lateral deflection is of most serious importance, when we

recollect that the rails being out of gauge will throw the trains

off the line.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Explaining Their Construction, Peter LeCount (1839). |

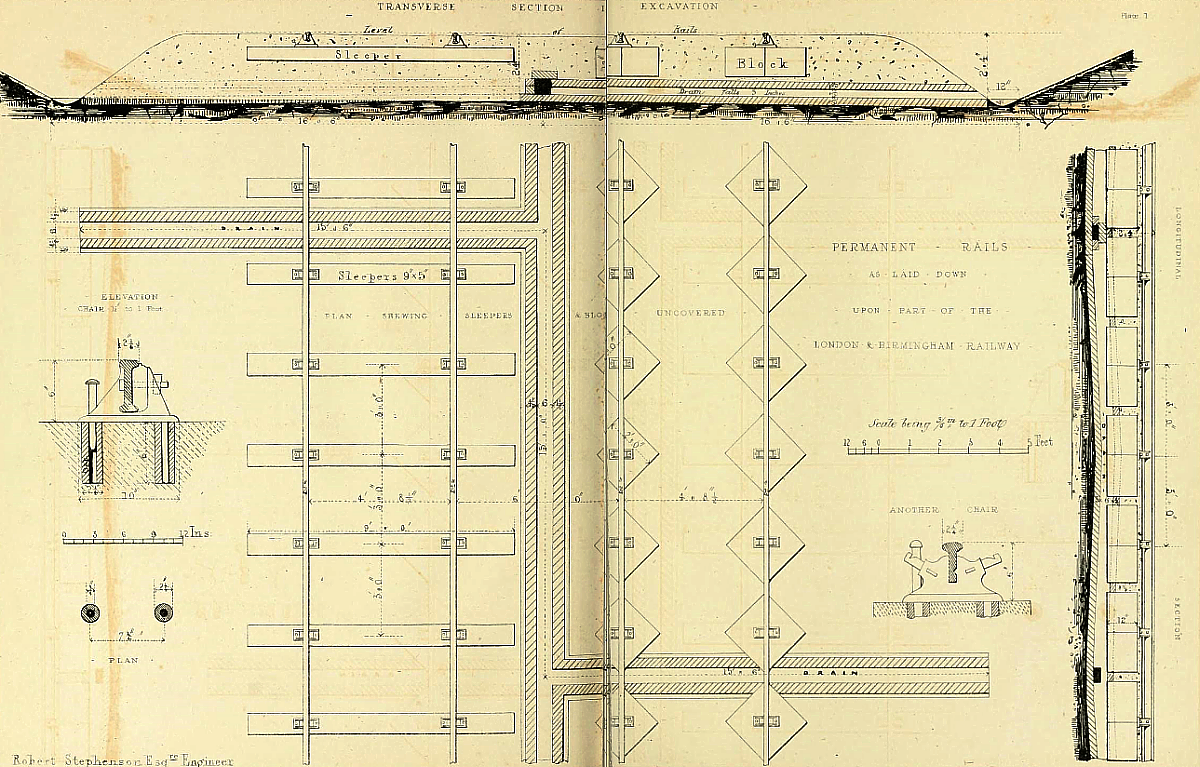

A drawing from Stephenson’s

specification for the permanent way.

Above: stone blocks (right of

drawing) were laid diagonally, instead of vertically. This was thought to have

the effect of steadying the rails,

while it gave the workmen access to the

four sides to set them right if they became displaced.

Below: detail. Chairs placed at 3 feet spacing.

Mail coach, Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

The coach is sitting on fish-bellied rails seated on diagonally laid stone

blocks

of the pattern used on the London and Birmingham

line.

|

The following describes the London to Birmingham

track in the year in which the line was opened:

RAILS.

The total length of the line is 112½ miles. The part between Euston

Grove and Camden stations is laid with four double lines of rails;

the remainder with two double lines. The sidings, or

passing-places, with the stations, &c., make an addition of one

tenth to the quantity of the rails, so that there will be about 125

miles of double line of railway.

The width of each double line of way is five feet. The space in the

centre, between the lines, is six feet.

The rails used on the line are all of malleable iron. Those

originally laid upon the Liverpool and Manchester line were of the

weight of 35 lbs. to the yard; but they have been found insufficient

for the immense traffic, and they have accordingly been increased.

On the London and Birmingham line 10 miles are laid with rails of

unequal depth termed fish-bellied, 50lbs. to the yard; 25 miles with

parallel rails 65lbs to the yard; and the remainder with parallel

rails 75lbs to the yard.

The rails are supported by cast iron chairs or pedestals of an

average weight (of about 25lbs) fixed to stone blocks or wood

sleepers; a piece of felt being placed between each chair and

block. The chairs under the 50lbs. rails are 3 feet from centre to

centre, under the 65lbs. rails 4 feet, and under the 75lbs. rails

they were intended to have been 5 feet; but, this latter bearing

having been considered too great, has been altered to 3 feet 9

inches in the cuttings and small embankments, and to 2 feet 6 inches

on the higher embankments.

The rails are raised above the ground rather more than an inch; they

are wedged to the chairs with oak keys.

SLEEPERS.

The stone blocks under the chairs are 2 feet square and 1 foot deep,

excepting those under the joints of the 75lbs rails which are 1 foot

3 inches deep. They are laid in a direction diagonally to the

rails. The descriptions of stone are various, ― viz. Granite,

Limestone, Portland, Bramley Fall, and Whitby.

The sleepers are mostly of larch and oak, some few are of beech; all

9 feet long, 9 inches wide, and 5 inches deep.

The blocks are used in the excavations and on the smaller

embankments; the sleepers on the large embankments.

The chairs are attached to the blocks by drilling two holes in each

block, into which oak trenails, or plugs, are driven, and a spike

inserted through them and the chairs. The chairs are attached to

the sleepers by a couple of pins or spikes.

The trenails are 6 inches long, with a hole bored through for the

spike.

The ballasting of the line is about 2 feet in thickness, being 10

inches under the bottom of the blocks, and 18 inches under the

sleepers. Open brick drains, to take off the soakage, are laid

along the centre of the ballasting, and each side in the

excavations.

Where the common roads pass the railway on a level, the part of the

road between and on each side of the rails is paved with granite

carriage-way paving.

The Iron Road Book and Railway Companion,

Francis Coghlan (1838).

|

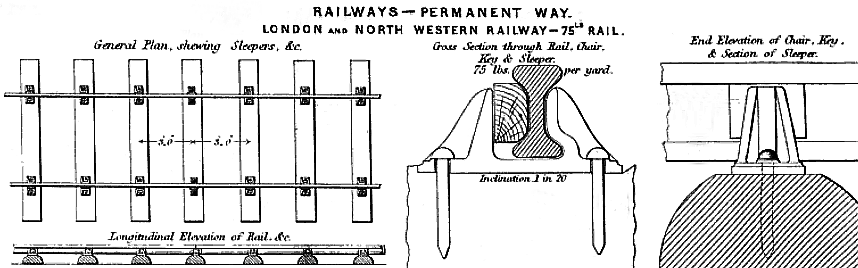

L.N.W.R. permanent way using 75lb rail,

from The Practical Railway Engineer, G. D. Dempsey (1855).

|

――――♦――――

SAFETY AND RAILWAY SIGNALLING

|

On an engine, in the

night-time,

Flying through the starlit gloom;

Not a word between us spoken:

On great caution hangs our doom.

Watch the gauge ― turn on the water ―

Ope the gleaming furnace-door,

Making us appear like demons,

In the glare, and smoke, and roar!

Ho! the signal! Put the break on!

Shut off steam ― reverse the gear!

Now the monster throbs and struggles,

While we stare ahead and fear.

To man’s frail limbs the mighty engine

Yields obedience, and we stand

Beneath the lofty danger-signal.

(Isn’t this description grand?) |

|

From Fifty years of the London

& North Western Railway,

David Stevenson (1891) |

Railway signalling and telecommunications (originally the electric

telegraph) evolved in partnership, almost from the start of the

steam worked public railway era. These two disciplines were later

to be joined by a third, digital computing. Nowadays, components

from each combine to form systems capable of providing a distant

traffic control centre with the ability to transmit instructions to

any part of the network and to receive a wealth of information on

the location of trains and on the status of track and other

equipment. By comparison, the signalling system first employed on

the London and Birmingham Railway was primitive:

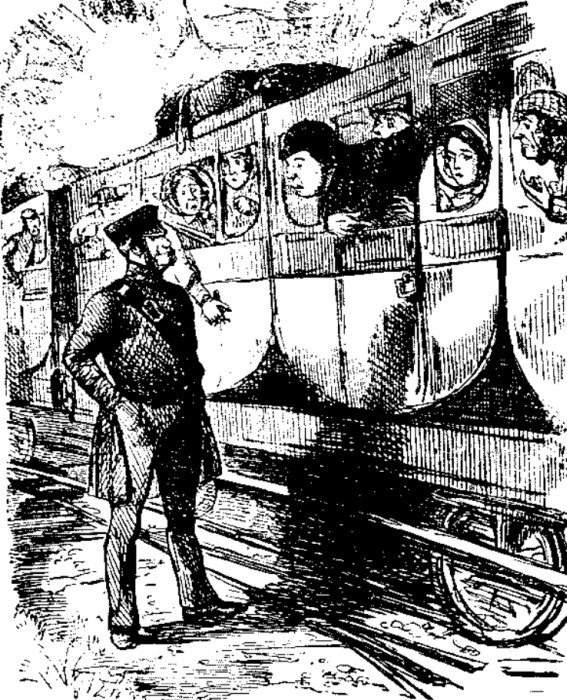

|

Passenger.

Guard.

Passenger.

Guard. |

“Whats

the matter guard?”

“Oh,

nothing particular, sir. We’ve

only run into an excursion train!”

“But,

good gracious! there's a train just behind us, isn’t

there?”

“Yes,

sir! But a boy has gone down the line with a signal,

and it’s

very likely they’ll

see it!”

From Punch (magazine) |

Until the deployment of the electric

telegraph ― which was not as quick as it might have been ― there was

no means of even monitoring the progress of a train. If it was

unduly late, all that could be done to discover why was to despatch

a spare locomotive (or a horse and rider) to find it. As this

section attempts to illustrate, the appearance of effective railway

safety took time ― even the introduction of the locomotive’s steam

whistle had to await a level-crossing accident. [8]

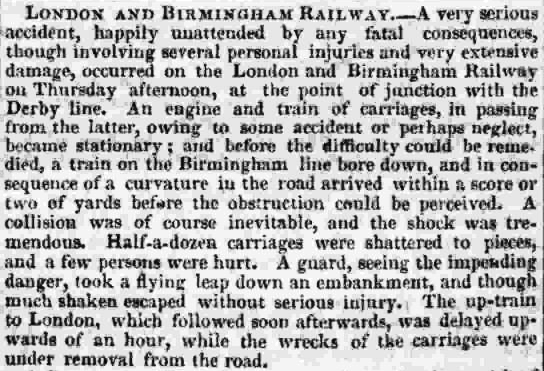

A railway policeman (right) giving the

‘all clear’.

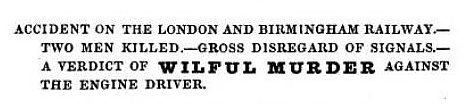

In its bare essentials, railway signalling is designed to prevent

collisions between trains. However, an accident that occurred at

Harrow in November 1840 demonstrates another aspect to the problem,

which modern railway signalling systems control by automatically

stopping trains that pass signals set to danger. In this case the

driver of the ‘train engine’ of a double-headed goods train ignored

a stop signal, causing his train to collide with a stationary engine

with fatal consequences:

“At the inquest on the two men killed

by the collision near the Harrow station of the London and

Birmingham Railway, the evidence proved that the blame rested

principally with the driver of the second engine of the waggon

train; who did not shut off the steam, though warned; and the train

consequently ran against the engine which was standing on the line.

The man lost his life for his want of care; and the fireman of the

first engine was also killed ― he had jumped off, it is supposed,

and been run over by the waggons. The driver of the engine which

was standing on the line was also blameable for having left his

engine in the care of the stoker, whilst he went to a public-house

to obtain refreshments for the men at work in clearing the railway

from the obstruction caused by the break-down of a waggon-train in

the early part of the afternoon. It appeared from the

examination of the witnesses at this inquest, that Bradbury, the

driver of the first engine of the waggon train, cannot write his

name, or read. It was stated also that many of the men employed as

engine drivers are equally illiterate.”

From The Spectator, Volume 13 (1840).

The illiteracy that this article refers to implies a

further risk to railway safety, for being unable to read the

company’s operating instructions can negate aspects of safe working

and traffic control.

Accidents can also result from problems with the

railway infrastructure, such as a track or signalling failure: [10]

|

“The

maintenance of the permanent way in perfect efficiency

is of the utmost importance. To provide for this, the

line is divided into sections, each of about a score of

miles, to which ‘overlookers’

are appointed. These sections are subdivided into short

lengths, superintended by a foreman, or a

‘squinter’,

as he is technically designated, with two or three

assistants. The duty of the foreman is to visit his

portion of line every morning before the first train

passes, to see that the rails and sleepers are perfectly

secure, to observe whether the keys are fitted in the

chairs, and generally to inspect the fences and works.

In case of repair being required, he summons his men

to the spot, and if it is sufficient to interfere with

the passage of trains, or to warrant the exercise of

special caution on the part of engine-drivers, a

signal flag to that effect is placed eight hundred yards

above the injured spot, until the patch is completed.”

Our Iron Roads, F. S.

Williams (1852). |

|

|

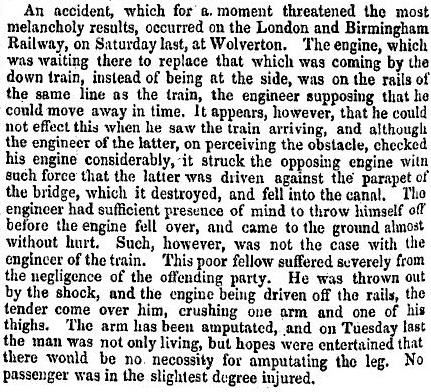

The Weekly Herald,

31st March 1839. |

|

Even the simplest of signals, such as the flag

mentioned above, by halting traffic and isolating the problem serve

to prevent matters becoming worse. Being guided by fixed rails,

railway traffic is highly vulnerable to accidents caused by line

obstruction (such as that mentioned in the Weekly Herald

article above) or track failure, particularly as trains sometimes

operate at speeds that prevent them being halted within the driver’s

line of sight.

|

|

|

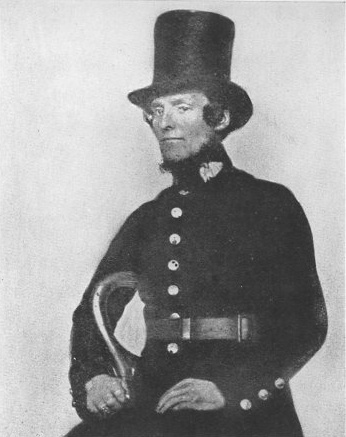

The Standard, 14th Sept.

1839 |

Thus, from the earliest days, it was recognised that

an effective signalling system together with operating rules (Appendix)

were crucial to safe railway operation. However, before describing

the railway signalling of the period, it is first necessary to say

something about the ‘policemen’ who operated the system, for their

role has changed significantly over the years.

Established in 1829, the Metropolitan Police was the U.K.’s first

police force; it was not until 1856 [11] that

county and borough police forces became compulsory throughout the

rest of England and Wales. In 1830, the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway formed a ‘police establishment who have station houses

[police stations] at intervals of about a mile along the road’.

Three years later, the London and Birmingham Railway obtained their

first Act, which required the Company to create and maintain a force

of special constables to police its property. In 1837, the

authority of the London and Birmingham force was extended to a

distance of half a mile on either side of the line:

“XXV. And be it

further enacted, That it shall be lawful for any Justice of the

Peace acting within his Jurisdiction and he is hereby required to

appoint such fit and proper Persons as he shall think proper to be

Special Constables within the said Railway and other Works and every

or any Part thereof; and every Person so appointed shall make a

solemn Declaration, to be administered by the same or any other

Justice of the Peace, duly to execute the Office of Constable for

the said Premises; and every Person so appointed, and having made

such Declaration as aforesaid, shall have Power to act as a

Constable for the Preservation of the Peace and for the Security of

Persons and Property against Felonies and other unlawful Acts within

the Limits of the said Premises, and within Half a Mile therefrom,

and shall have, use, exercise, and enjoy all such Powers,

Authorities, Protection, and Privileges for the apprehending

Offenders, as well by Night as by Day, and for doing all Acts,

Matters, and Things for the Prevention, Discovery, and Prosecution

of Felonies and other Offences, and for the Preservation of the

Peace, as Constables duly appointed now have by the Laws and

Statutes of this Kingdom; and it shall be lawful for any such

Justice to dismiss or remove any such Constable from his Office of

Constable, and upon every such Dismissal or Removal, all Powers,

Authorities, Protections, and Privileges by virtue of such

Appointment as aforesaid vested in any Person so dismissed or

removed shall wholly cease.”

An Act to amend the Acts relating to the

London and Birmingham Railway,

1 Victoriæ, cap. lxiv, R.A. 30th June

1837.

Today, points and signals are operated by signalmen,

but in the early days the railway policemen performed this task. A

railway policeman’s duties also included collecting tickets, serving

on occasions as booking clerks, and performing (on railway land) the

law enforcement duties that police perform in the community today:

|

“The

inspector at each station has a portion of these men

under his orders; they are on duty ― that is, walking

backwards and forwards on their beat ― from half an hour

before the passing of the first train in the morning

till after the passing of the last train at night. I

can vouch to their promptitude from personal knowledge,

having spoken with every man from London to Birmingham,

when I surveyed the line . . . . and I am convinced

that, were the Directors themselves placed on the line,

they could not display greater anxiety than these men do

for the protection and safety of those travelling on the

railway. Each man, besides being in the employ of

the Company, is sworn as a county constable; they

receive the same pay, and wear a dress similar to that

of the metropolitan police, except in colour which is

green. Watch boxes are placed at certain distances

on the line, to protect the men from bad weather . . . .

The principal stations at present are at Watford, Tring,

Denbigh Hall, Rugby and Coventry. At each of these

places, two clerks, a police inspector, and several

policemen and porters, are in attendance. At the

secondary stations, which are the Harrow, Boxmoor,

Berkhamsted, and Leighton Buzzard, there is but one

clerk, an inspector, and a less number of policemen and

porters.”

The Iron Road Book and Railway

Companion, Francis Coghlan (1838). |

The original

Metropolitan Police uniform. London and Birmingham

Railway police were similarly attired. |

Because the London and Birmingham Railway was double-tracked

throughout, in normal operation all that was required of the

signalling system (excluding control over points and junctions) was

to ensure that trains were spaced sufficiently far apart to avoid

one train colliding with the rear of the train in front. Policemen,

stationed at intervals along the line (‘blocks’) used sand glasses

to time the interval between trains. If a train passed shortly

before the following train arrived, then the driver of the following

train was instructed to slow down or stop in order to increase the

distance between it and the train in front. This method is called

‘time interval working’, and the means by which a railway policeman

halted a train, or indicated to its driver the status of the block

he was about to enter, was by using flag signals or different

coloured lights during darkness:

“Throughout

the journey travellers will have observed a number of policemen

stationed along the Railway, who not only prevent intrusion,

but are charged with the important duty of keeping the road free of

obstruction and making signals as the train passes. The police are

placed along the line at distances varying from one to three miles,

according as local circumstances render it necessary. Each man

has his beat and duties defined, and is provided with two signal

flags, one of which is red and the other white: the white flag is

held out when no obstruction exists; and, on the contrary, the red

flag indicates that there is danger, and that the train must not

pass the signal till it is ascertained that the cause of danger is

removed.

Each policeman, also, is furnished with a revolving signal lamp, to

be used after dark; which shows, at the will of the holder, a white

light when the line is clear; a green one when it is necessary to

use caution, and the speed of the train be diminished; and a red

light, to intimate the necessity of immediately stopping. The

whole of the police department is under the able control and

superintendence of Captain C. R. Moorsom, R.N., a gentleman who has

been connected with the Company since its formation, as one of the

Secretaries. It is but justice to add, that the police arrangements

on the London and Birmingham Railway are more complete than on any

other line.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Roscoe and Lecount (1839).

|

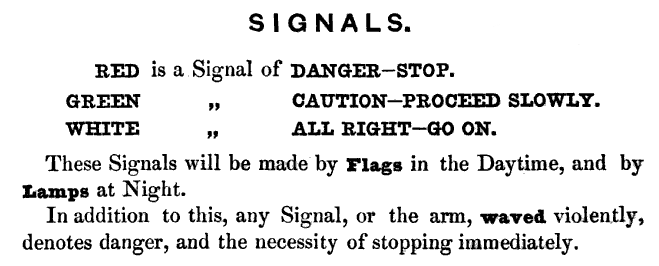

|

1. When the Line is clear and

nothing to impede the progress of the Train, the

Policeman on duty will stand erect, with his Flag in

hand, but show no signal thus . . . |

2. If it be necessary to proceed

with Caution the Green Flag will be elevated thus . . .

. |

3. If it be necessary to proceed

with Caution from any defect in the rails, the Green

Flag will be depressed thus . . . . |

|

|

|

|

|

4. If required to stop, the Red Flag will be shown

and waved to and fro, the Policeman facing the Engine.

5. Engine-Drivers must invariably Stop on seeing the Red

Signal.

6. As soon as the Engine passes, the Policeman will

bring his flag to the shoulder.

7. Every Policeman will be responsible for having his

Hand Lamp in good order. |

|

From the London & North Western

Railway signalling rules, 1848. |

When writing about some of the problems that occupied

the Board during the early days of the Railway, David Stevenson, a

former employee, included railways signalling:

“The working

of the line went struggling towards a state of order. The rails

were found to be too light for the traffic ― 56lb fish-bellied rails

in some cases ― the stone blocks a failure; fires to luggage on the

tops of the carriages frequent; signals by flag and hand lamps

insufficient. The signalmen, dressed in police uniform, had been

drilled by Mr. Superintendent Bedford, formerly of the Guards and

lately of the Metropolitan Police, and they brought the flag-staff

round to the shoulder, as the trains passed, with true military

precision. But they were not enough, and signal posts were

contemplated. These and many other defects occupied the Board and

Management.”

Fifty years of the London & North Western

Railway,

and other memoranda in the life of

David Stevenson, (1891).

It is unclear exactly when the signals mounted on posts that

Stevenson refers to were introduced, but in the account given by

Frederick Williams (in which he also refers to flag signals) he

describes the signalling posts in use by the London and North

Western Railway a few years after its formation, but without saying

whether they were in use on the southern section (the former London

and Birmingham Railway). Nevertheless, they are indicative of the

state of railway signalling at the time:

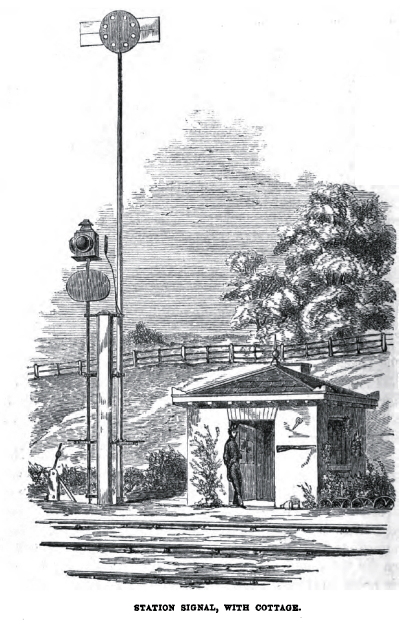

|

“The signal

arrangements at the intermediate stations on the

[London and]

North Western line are various, but all are simple and

complete. A station signal is provided for both the up

and the down line, one being usually erected at each end

of the station, and of the kind represented in the

Engraving. On a train stopping, or travelling slowly

through an intermediate station, the signal which is

painted red on one side is shown for five minutes in the

direction from which the train has come, in order to

stop any following train; the green signal, on the

shorter post, is then turned on for five minutes, to

complete the ten minutes precautionary signal . . . . As

the lamps and the boards are connected together, the

lamp has only to be lighted at night or in a fog, and

the arrangement is complete. When the vane is presented

edgewise to the driver of an approaching train as is

seen in the Engraving, it shows that all is right. The

higher mast supports the red signal and the lower one

with the lamp has the green.”

Our Iron Roads, F. S.

Williams (1852) |

|

|

|

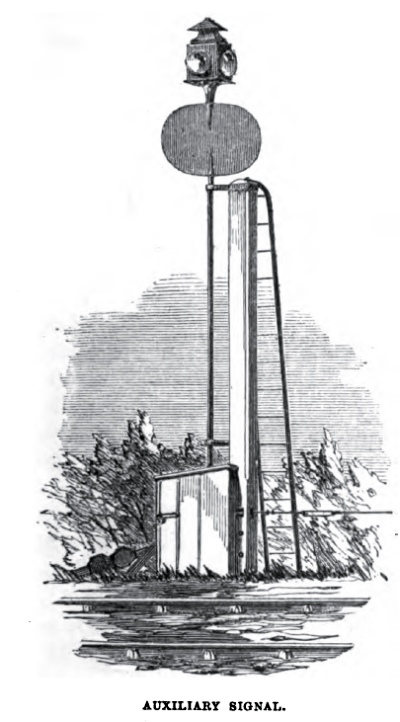

“Besides these there

are auxiliary signals at most of the principal stations,

worked by means of wires, which permit their being

placed at almost any distance from the spot where they

are regulated. These auxiliaries are especially

valuable in thick weather; for as they are constructed

several hundred yards up or down the line; drivers of

engines can obey them when it would be impossible for

them to see the station signals with distinctness. They

are constructed with only the green or ‘caution,’ and

the ‘all right’ signals; the presence of the former

intimating that the red signal is turned on at the

station, and that it is therefore to be approached

slowly. In the Engraving of the station signal, the

reader may observe the lever by means of which the

auxiliary signal is worked.”

Our Iron Roads, F. S.

Williams (1852) |

|

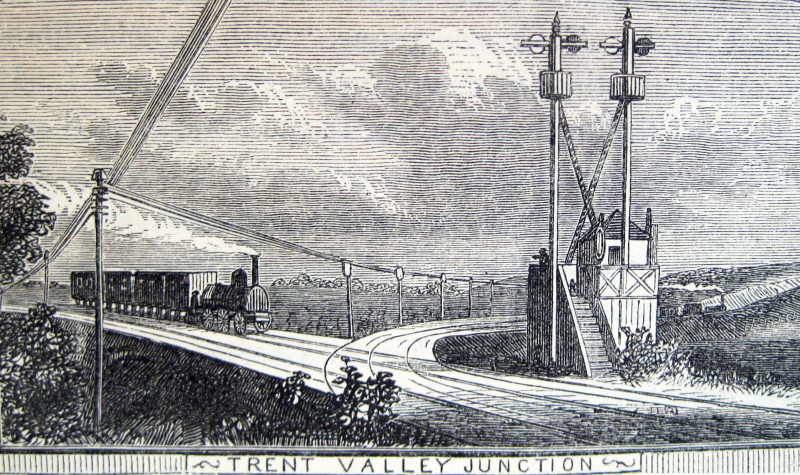

|

“Where junction lines unite, or

lines cross one another at the same level, it is

essential that a complete

system of signalling should be adopted. The Engraving .

. . . represents a junction or double signal station.

It consists of two masts, to the summits of which

fan-like arms and lamps are attached; these convey the

desired information to the drivers of approaching

trains. When the arm which is painted red, and is

always on the left of the engine-driver, is at right

angles to the mast, it signifies danger, and the train

must be immediately stopped; if it be at an angle of

forty-five degrees, caution must be observed; and if the

arm be parallel with the post, it announces the signal

all right.”

Our Iron Roads, F.

S. Williams (1852) |

|

|

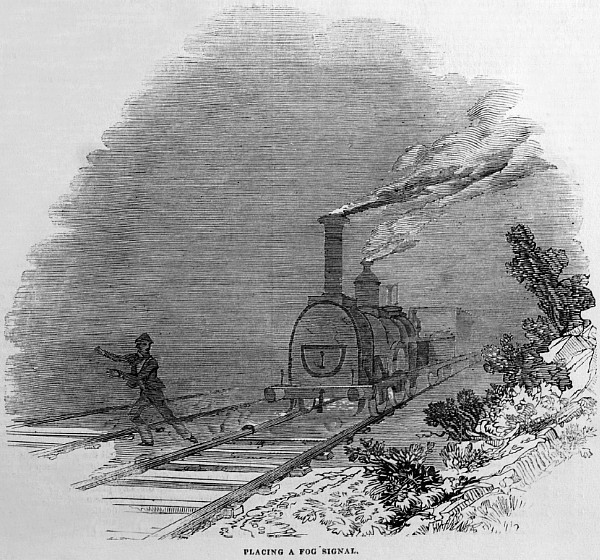

“FOG

SIGNALS. ― In foggy

weather both day and night signals are given; but in

addition, when accident or sudden emergency requires,

‘Cowper’s Fog Signal’ is used. This is a detonating

compound, packed in the shape of a small circular box,

with flanges to fasten it to the rail, and which, on a

train passing over it, explodes with a tremendous

noise. The signal thus given is the warning

immediately to stop the train. Our engraving shows

a policeman placing one in front of an advancing train.”

Illustrated London

News, 14th December 1844. |

――――♦――――

THE ELECTRIC TELEGRAPH

Separating trains using time interval working was the

best that could be achieved when the Railway first opened. However,

this method had an inherent risk ― a policeman had no way of knowing

whether a train that had passed him had in fact cleared the block.

If, for any reason, that train subsequently slowed appreciably, or

stopped, the crew of a following train had no way of knowing unless

it was clearly visible to them and at a sufficient distance

in which to bring their train to a halt. With the invention of the

electrical telegraph it became possible for policemen to exchange

messages between the ends of a block to confirm that the block was

clear and to prevent more traffic from entering if it was not. This

method is called ‘block’ working, but for many years its use was

considered an unreasonable restriction on the free flow of railway

traffic ― profit came before safety:

“The fundamental principle

of the ‘block’ was at first derided, and the name chosen was

considered as characteristic of the condition traffic was likely to

get into under any such system of working. That there should be any

reason to prevent a driver from proceeding as far as his visionary

powers assured him the line was clear, or that any train should be

prevented from ‘bumping’ a preceding train gently, of course was

considered absurd, and there were not wanting those who predicted

the early demise of this or any other system which involved

restrictions being put on the free passage of traffic. This, of

course, was before the era of express trains travelling at rates

varying between 60 and 70 miles per hour.”

Railway ‘block’ signalling, James Pigg

(1898).

|

|

|

|

Sir Charles Wheatstone F.R.S.

(1802-75), physicist. |

Sir William Fothergill Cooke

(1806-79), inventor. |

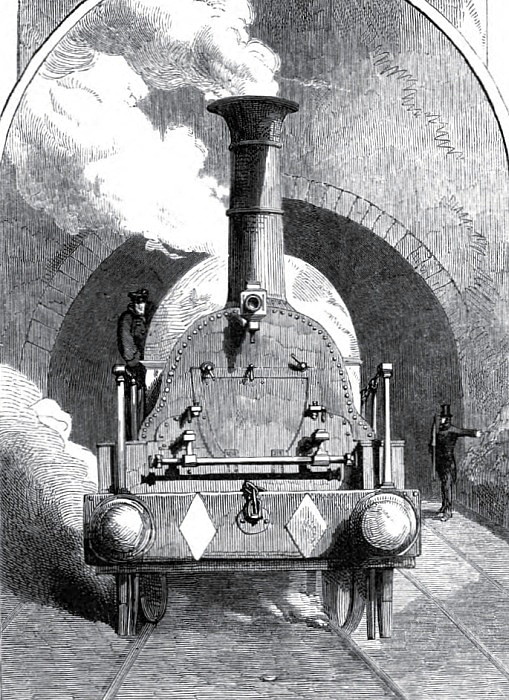

In the U.K., the first successful demonstration of an electric

telegraph took place on 25th July 1837, when a system developed by

William Fothergill Cooke and Charles Wheatstone was used to exchange

messages between Euston Station and the stationary engine house at

the top of the Camden Incline:

“AFTER repeated

experiments and numerous accessory discoveries of scientific men,

both in this country and abroad, the famous invention of electric

telegraphy was at length brought to the test of a fair and

satisfactory trial on the night of the 25th June, 1837, or just

thirty years ago. For the purposes of this experiment, a mile and a

quarter of telegraphic wire had been laid down between the two

stations of Euston Square and Camden Town, of what was then the new

London and Birmingham Railway. Professor Wheatstone seated in a

small ill-lit room at Euston Station, and surrounded by several men

since known to fame, and notably by Robert Stephenson, held

anxiously the one end of the mystic wire, whilst his co-adjutor, Mr.

Fothergill Cooke, attended at the other extremity in Camden Town.

We all know the result. The old inquiry: ‘Canst thou send

lightnings that they may go and say unto thee, Here we are?’ had

often been asked, and sometimes half-answered; now, however, a

positive reply was made possible; ‘Never did I feel,’ says Professor

Wheatstone, ‘such a tumultuous sensation before, as when in that

still room I heard the needles click; and as I spelled out the

words, I felt all the magnitude of the invention now proved to be

practicable beyond cavil or dispute.’ Wheatstone and all concerned

might well exult in this triumph! The telegraph has, from this

humble beginning, and within the short space of thirty years, become

an indispensable agent of civilized society.”

Telegraphic Reform ― The Post Office and

the Electric Telegraph. The Post Office (1867).

“This

instrument gives all the letters of the alphabet, the numerals, and

a vast number of conventional signals; which follow each other with

perfect distinctness at the rate about thirty five per minute, and

can be read off with the greatest facility even by an unpractised

eye.

Before the operator is placed an instrument, which gives the exact

signals which he is conveying to a distance; if therefore, through

carelessness, an error is committed, it is immediately perceived,

and corrected by the succeeding signal. These signals are

communicated from either terminus with equal facility, and literally

with the speed of lightning, both instruments being synchronous in

their action.

When the telegraph is about to be put into action, the person

communicating rings an alarm bell by striking a key, or by the same

motion he may release a weight, which can be attached to the wrist

of the person who has the working of the instrument at the distant

point. This perhaps will be the most effective mode of attracting

the attention, particularly at night, or if deaf and dumb persons

were so employed. By this simple contrivance, the unceasing

vigilance necessary for every other description of telegraphs is

dispensed with; whilst by night as well as by day, sunshine or rain,

fog or storm, the electro-magnetic telegraph performs its silent

mission, uninfluenced by those disturbing causes which render the

ordinary [i.e. optical or semaphore]

telegraph useless during four-fifths of the year.”

The London and Birmingham Railway Companion,

Arthur Freeling (1838).

|

|

|

Cooke and Wheatstone indicator

panel and, below,

transmission keys. Photo: Milton Keynes Museum. |

|

|

|

Cooke and Wheatstone’s 5-needle

telegraph.

The needles are pointing to the letter ‘G’. |

The Camden trial was followed shortly afterwards by a

radically different approach to telegraphy developed in the U.S.A.

by Samuel Morse and Alfred Vial. What became known (somewhat

unjustly to Vial) as the ‘Morse’ system, was first demonstrated on

the 11th January 1838 at the Speedwell Ironworks near Morristown,

New Jersey. It was the practicalities of this system and the Morse

Code in its various adaptations that quickly led to its universal

adoption for both line and, later, wireless telegraphy. But within

the U.K. (and throughout the British Empire) simplified versions of

the Cooke and Wheatstone system continued to be used in railway

signalling applications for many years. The system did not require

its operators to become proficient in the use of Morse Code nor to

be literate, an important factor in an age when illiteracy was

common. All that it required was for the operator to watch the left

or right deflections of a needle and/or listen to the ‘dings’ of a

signal bell.

|

“. . . .

Cooke and Wheatstone’s Telegraph still keeps its

ground. Superseded on all the principal commercial

telegraph systems, namely, those worked for the public

by the Telegraph Companies, it is still in demand for

Railway Telegraphs and other lines where simple

apparatus is required, as it is generally in the hands

of porters, brakesmen, and other inexperienced workmen.

It owes this, no doubt, as much to the character it

earned in the first stage of Telegraphic operations, as

to its simplicity and durability . . . . ”

An Illustrated Hand Book to the

Electric Telegraph, Robert Dodwell (1862). |

The history of the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph is a study in

itself, as indeed was the complex relationship between its inventors

(reminiscent of that between Gilbert and Sullivan). Of the pair,

Cooke was the impresario with the commercial acumen and ambition who

wished to profit from the invention, and did. Professor Wheatstone

was the scientist, possessing the technical ability to deliver a

working system, the principles of which he wished to release

gratis to the world at large. Conflict between the two was

inevitable and at one stage Marc Brunel (father of I. K. B.) was

appointed to arbitrate between the collaborators over who should

receive credit for the invention ― after hearing the evidence he

distributed the honours evenly.

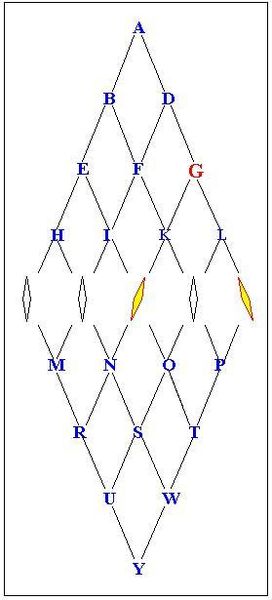

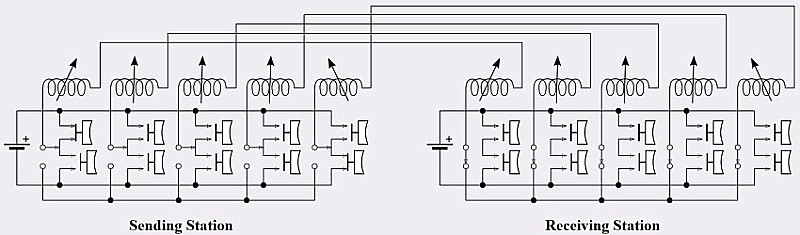

The initial design of the Cooke and Wheatstone system required for

its operation five signal wires. To transmit a character, current

was sent along two of the five wires by operating two

of five transmission keys. At the receiving station, the five

signal wires terminated on an indicator panel comprising five

needles, each of which could swivel to left or right. In the

system’s idle state all the needles pointed vertically, but when

energised by signals sent from the transmitting station, two of the

five needles swivelled to point to the letter on the indicator panel

that corresponded to that being transmitted. In the example shown

in the accompanying diagram, the two energised needles (coloured

yellow) intersect at the letter ‘G’.

The problem with the Cooke and Wheatstone system in this form lay in

the number of conductors it required. A five-wire circuit [12]

was expensive to install, added to which the limited technology of

the time gave poor electrical insulation, which quickly perished,

thereby affecting the system’s reliability. However, those who

attended the Camden demonstration ― including Robert Stephenson and

Charles Fox ― were impressed by what they saw:

“London and Birmingham Railway,

Engineering Department,

Camden Station, September 18th 1837.

My dear Sir, ― I have great pleasure in adding my testimony to that

of many others, who have been gratified by witnessing the very

beautiful experiments exhibited by yourself and Professor Wheatstone

to prove the practicability of transmitting signals by means of

electro magnetic fluid. Nothing can have been more satisfactory

than these experiments, which have placed beyond a doubt that the

principle may be applied with unerring certainty.

I am dear, Sir, yours very truly,

Charles Fox, Resident Engineer.

W.F. Cooke, Esq.”

A Reply to Mr. Cooke’s Pamphlet, ‘The Electric Telegraph . . . .’,

Wheatstone and Cooke (1855).

Circuit diagram of the 5-needle telegraph

transmitting the character ‘A’.

Picture:

Spinningspark

However, the Directors were only prepared to lay down

telegraph lines between London and Birmingham provided that their

counterparts at the Grand Junction Railway Company continued the

circuits northwards to Liverpool; this they refused to do. As a

result, the telegraph languished for the remainder of the Railway’s

independent existence, with signalling between the ends of the

cable-worked Camden Incline being conducted over a pneumatic system.

“The

trains were hauled from Euston to Camden by a stationary engine and

an endless rope 2½ miles long, these ropes

cost £460 each. The working of this section is described in a

paper of the time as follows:

‘As

soon as the carriages at Euston are connected with each other and

the passengers seated, the train is pushed forward by the porters to

a bridge under Wriothesley Street; here it is attached to a large

endless rope for the purpose of being drawn up an ascent on the line

to Camden Town depot, a distance of more than a mile. The

gradients of the inclined portion of the railway vary from 1 in 62

and 1 in 366.’

The starting signal from Euston to the stationary engine at

Camden was conveyed by an underground pneumatic tube, which worked a

whistle. It is interesting to note that in 1837 Cooke and

Wheatstone had carried out some successful experiments between

Euston and Camden with their electric telegraph, and were anxious to

extend it to the North, but for some reason the directors would not

consent to this, and Cooke and Wheatstone took their invention to

the Great Western Railway, where it was successfully taken up.”

The History of the London & North-Western

Railway, Wilfred L. Steele (1914).

In the meantime, that imaginative but occasionally flawed genius I.

K. Brunel also saw the possibilities of the electric telegraph. In

1838, he encouraged the Great Western Railway Company to establish a

five-needle system between Paddington and West Drayton, a distance

of 13 miles. It seems that, in the history of railway signalling,

the laurels for introducing block working using the electric

telegraph, albeit in a rudimentary form, must go to the Great

Western Railway, for . . . .

“. . . .

the germ of the present

system was brought into use between Paddington, West Drayton, and

Hanwell, on the Great Western Railway, at the instance of Cooke and

Wheatstone, as early as December, 1839. The system there brought

into operation was an adaptation of the ordinary telegraph system

the departure and arrival of trains being telegraphed, and

instructions issued to stop a second train on its arrival at any of

the telegraph stations until the arrival of the first train at the

advance station was telegraphed back. This is the earliest record

from official sources of the application of electricity to the

preservation of a space limit between successive trains on the same

line of rails.”

Railway ‘block’ signalling, James Pigg

(1898).

|

|

|

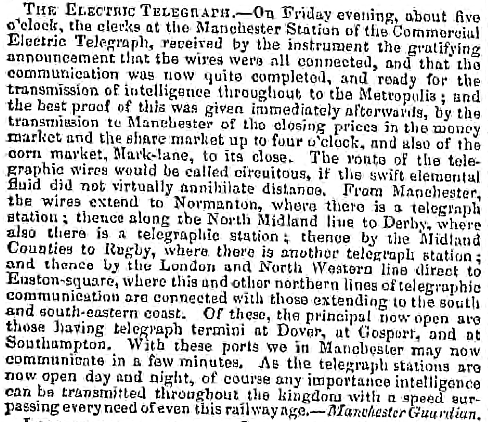

The Manchester Guardian,

20th November 1847. |

The electric telegraph did not appear on the London

and Birmingham line until after the company mergers of 1846, from

which emerged the London and North Western Railway. In the

following year telegraph circuits were laid between London and Rugby

and onwards to the north, while from Euston Square connections had

already been established with the south and south-east coasts. But

these circuits were used principally to convey revenue-earning

commercial traffic. Although the telegraph could convey messages

between stations connected to the system, signals and points were

still operated from adjacent external ground-frames, rather than

being grouped together in enclosed signal-boxes, so their operation

was physically separated from the telegraph. And so time interval

signalling continued until . . . .

“. . . . About 1855 an epoch-making change

in the matter of signalling took place on the London and

North-Western, for, about this time, the North-Western inaugurated

on the southern division [the former London and

Birmingham Railway] a

system of signalling known as the two-mile telegraph system.

Previous to this it must be confessed that almost everywhere

signalling had been in an extremely crude state, and fast travelling

in consequence fairly risky, the chief safeguard being a long time

interval between trains and a good lookout ahead.”

The History of the London & North Western

Railway, Wilfred L. Steel (1914).

|

|

|

A block instrument set to its

default

position of ‘line blocked’. |

Devised by Edwin Clark, the two-mile telegraph system

was the first use on the Railway of telegraph technology that was

capable of supporting block working, the principle behind

which is to allow only one train at a time to occupy a defined

section of track, the ‘block’:

|

“Among the more recent

improvements adopted by the London and North-Western

Company for securing perfect safety of travelling over

their line, has been the establishment of a ‘special

train telegraph,’ with signal stations every two

miles. At each station a policeman is on duty night and

day, in whose watch-box there is a telegraph dial with a

single needle. By inclining the needle to the left

hand, the person in charge gives notice to the next

station that a train had passed on to the two miles of

the road entrusted to his special care; while inclining

it to the right hand would show that the train had

passed off that portion of the line. There were in fact

but two signals, ‘train on’ and ‘train

off,’ but as it might happen that an accident

occurred upon the two miles of road between the

telegraph stations, the guard and breaks-man

(sic) were

instructed instantly to sever the ‘special train

wire,’ which has the effect of placing the needle

at each adjacent station in an upright position. The

policeman on duty at once becomes aware by this movement

that something is wrong, and can act according to

circumstances.”

Civil Engineer & Architect’s

Journal, Vol. 19 (1856). |

In 1855, the system was installed between Euston Square and Rugby, a

distance of 83 miles, using 2½-mile signalling blocks. The use of

permanently flowing current along the signal wire introduced a

valuable safety feature; it kept the needles pointing to their

settings until reset. However, in other respects danger crept in,

for the principle of block working was not strictly adhered to:

“Mr.

Edwin Clark (M. Inst. C.E.) perfected the scheme of Mr. Cooke, in

the system he introduced upon the London and North Western Railway,

which was fully described. The needle instrument was employed,

but its indications were made permanent by the use of continuous

currents of electricity. It not only showed when the line was

clear, and when there was a train on the line, but also the

occurrence of an accident. This last signal was produced by

rupturing wires that descended every alternate pole on the line; but

this plan was thought to be dangerous. The London and North

Western Railway Company did not strictly adhere to the

‘block’

system. They allowed two, three, and sometimes four trains to be on

the same length at the same time. The

‘train on line’

signal was only accepted as a caution, and not as a danger signal.

This was a partial expedient, which provided a certain amount

of safety, but it was not considered sufficient under all

circumstances to prevent collision.”

The Civil Engineer and Architect’s Journal,

Volume 26 (1863).

. . . . and the system’s inventor had this to say . .

. .

“ ‘It will be

observed that in the following system it has not been thought

desirable to forbid two trains entering on the same length of line

between the signal stations, it is, however, evident, that if the

stations are placed sufficiently near together to avoid delays from

stoppages, that by such an arrangement all accidents from collisions

will be quite impossible, and in this case the caution signal will

be entirely cancelled.’

As has previously been said, the two-mile system was a great advance

on any previous signalling system, but even then absolute security

was not by any means obtained, and trains over-running one another

and collisions were not infrequent. And this state of affairs

continued until the absolute block system was afterwards adopted,

which made travelling as safe as any signalling possibly could do.”

The History of the London & North Western

Railway, Wilfred L. Steel (1914).

Following the Armagh rail disaster ― the worst in the U.K. during

the 19th Century and Ireland’s worst railway disaster ever ― [13]

the Regulation of Railways Act 1889 (52 & 53 Vict. c. 57) was

enacted and the use of the absolute block system on passenger

carrying lines became mandatory.

CHAPTER

11

――――♦――――

APPENDIX

REGULATIONS FOR ENGINEMEN

|

At a Meeting of the Board of

Directors held on the 11th of September, 1847, it was

Ordered,

That the following code of Rules and Regulations be, and

the same is hereby approved and adopted for the guidance

and instruction of the Officers and Men in the service

of the London and North-Western Railway Company, and

that all former Rules and Regulations inconsistent with

the same be cancelled.

Ordered,

That every person in the service do keep a copy of these

Regulations on his person while on duty under a penalty

of five shillings for neglect of the same.

By order of the Board of Directors.

MARK HUISH,

General Manager,

London and North Western Railway. |

1. No Engine shall pass along the wrong line of Road, but if, in

case of accident, an Engine shall be unavoidably obliged to pass

back on the wrong line, the Engineman is to send his Assistant, or

some other competent person, back a distance of not less than 800

yards, before his Engine moves, to warn any Engine coming in the

opposite direction, and the Assistant shall continue running, so as

to preserve the distance of not less than 800 yards between him and

the Engine. If dark, the man shall take his light and make a signal

by waving the same up and down, and the Engineman of the Engine

moving on the wrong line shall keep his Steam Whistle constantly

going, and must not move in the wrong direction farther than to the

nearest shunt, where he is instantly to remove his Engine off the

wrong line of Road; and it is expressly forbidden that any Engine

should move on the wrong line of Rails at a greater speed than four

miles an hour.

2. All Engines travelling on the same line shall keep

800 yards at least apart from each other, that is to say, ― the

Engine which follows shall not approach within 800 yards of the

Engine which goes before, unless expressly required.

3. No person, except the proper Engineman and Fireman shall be

allowed to ride on the Engine or Tender, without the special

permission of the Directors or one of the Chief Officers of the

Company.

4. The Engineman and Fireman must appear on duty as clean as

circumstances will allow and every Driver must be with his Engine 30

minutes, and every Fireman 45 minutes, before the time appointed for

starting, in order to see that the Engine is in proper order to go

out, has the necessary supply of coke and water, and that the

Signals are in a fit state for use.

5. The Front Buffer Light of a Passenger Train is White, and of a

Goods or Cattle Train Green, except on the Liverpool and Manchester

Section.

6. Every Engineman shall have with him at all times in his Tender

the following Tools:―

|

1 complete set of Lamps |

1 Screw Jack |

|

1 complete set of Screw Keys |

A quantity of Flax and Twine |

|

1 large and small Monkey Wrench |

4 large and small Oil Cans |

|

3 Cold Chisels |

Plugs for Tubes |

|

1 Hammer |

2 Fire Buckets |

|

1 Hammer |

Fog Signals and Red Flag |

|

2 short Chains with Hooks |

|

7. When the Engine is in motion the Engineman is to

stand where he can keep a good look out a head and the Fireman must

at all times be ready to obey the instructions of the Engineman and

assist him in keeping a look out when not otherwise engaged

8. No Engine is permitted to stand on the main line (except under

very special circumstances) when not attached to a Train, and the

Engineman shall not at any time leave his Engine or Train, or any

part thereof, on the main line, unless there be a competent man in

charge to make the necessary signals.

9. No Engine shall cross the Line of Railway at a Station without

permission.

10. An Engineman is never to leave an Engine in Steam, without

shutting the Regulator, putting the Engine out of gear, and fixing

down the Tender Break.

11. No Engine is allowed to propel a Train of Carriages or Waggons,

but must in all cases draw it, except when assisting up inclined

planes, or when required to start a train from a Station, or in case

of an Engine being disabled on the road, when the succeeding Engine

may propel the train slowly (approaching it with great caution) as

far as the next shunt or turn-out, at which place the propelling

Engine shall take the lead.

12. No Engine is to run on the Main Line Tender foremost, unless by

orders from the Locomotive Superintendent, or from unavoidable

necessity.

13. Every Engineman on going out is to take his Time Table with him,

and regulate by it the speed of his Engine, whether attached to a

Train or not; and when not attached to a Train, he is on no account

to stop at second-class Stations unless specially ordered, or there

is a signal for him to do so.

14. Enginemen are not allowed (except in case of accident or sudden

illness) to change their Engines on the Journey, nor to leave their

respective Stations, without the permission of their Superintendent.

15. When the Road is obscured by steam or smoke (owing to a burst

tube, or any other cause) no approaching Engine is allowed to pass

through the steam, until the Engineman shall have ascertained that

the road is clear; and if any Engineman perceive a Train stopping

from accident or other cause, on the road, he is immediately to

slacken his speed, so that he may pass such Train slowly, and stop

altogether if necessary, in order to ascertain the cause of the

stoppage, and report it at the next Station.

16. Where there is an accident on the opposite Line to that on which

he is moving, he is to stop all the Trains between the spot and the

next Station, and caution the respective Enginemen, and further he

is to render every assistance in his power in all cases of

difficulty.

17. In case of accident to his Engine or Tender (when alone) he is

to send back notice by his Fireman to the nearest Policeman on duty:

but if the Policeman is too distant, the Fireman is to remain

stationary not less than 600 yards in rear of his Train (until

recalled), showing his Red Signal until he has rejoined his Engine.

(See Rule 17, page 182.)

18. Enginemen are strictly prohibited from throwing out of their

Tender any small coke or dust, except into the pits made for that

purpose at first-class Stations.

19. Enginemen with Pilot or Assistant Engines must be prepared

(while on duty) to start immediately on receiving instructions from

the Locomotive Foreman or the Station Master.

20. Enginemen are strictly enjoined to start and stop their Trains