|

NOTES AND

EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

CHAPTER

11

THE STATIONS

INTRODUCTION

“There is a great deal more

difficulty than would at first be imagined in laying out a railway station; and,

perhaps, in every one now in existence, if it had to be entirely built over

again, some change would be desirable: there are so many things to be

amalgamated, and such various accommodation to be provided, that the business

becomes exceedingly complicated.”

The History of

the Railway Connecting London and Birmingham, Peter Lecount

(1839). |

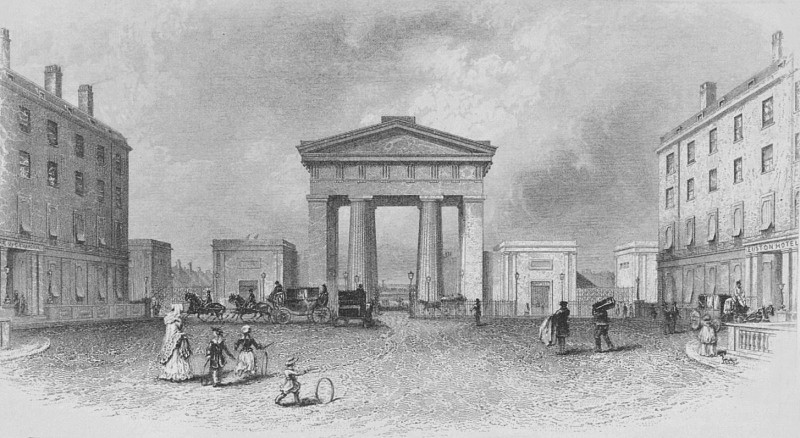

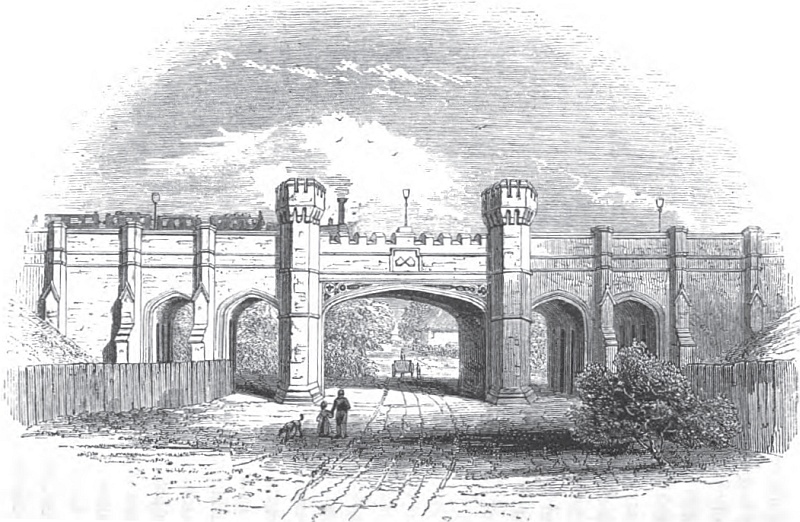

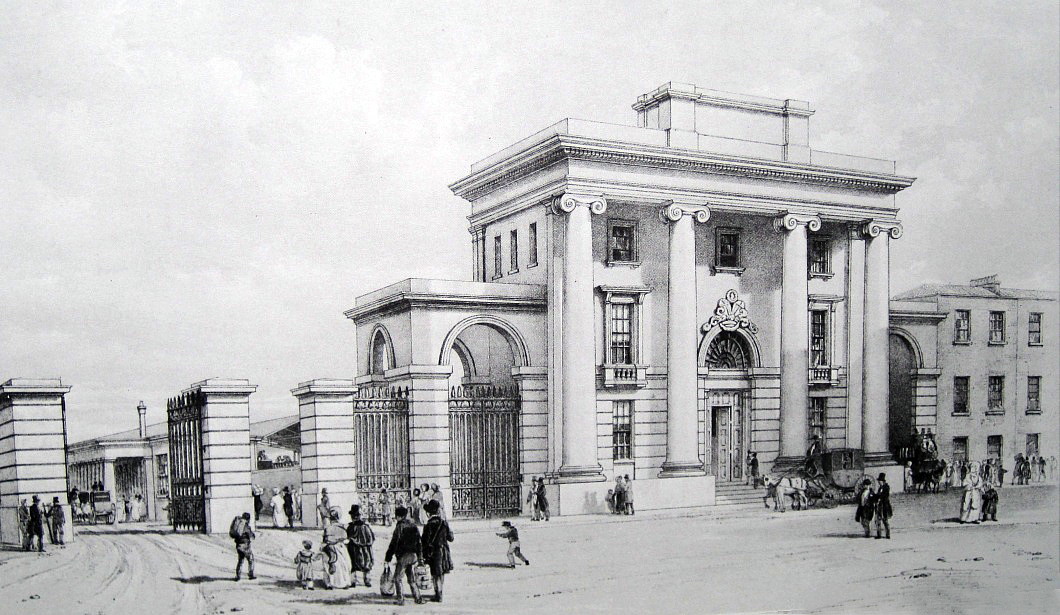

“Euston Square Depot. South front of the Propylæum, or entrance gateway, with two Pavilions, or Lodges, on each side, for

Offices”

by John Cooke Bourne, 1838.

The ‘Great

Gateway to the North,’ the entrance Portico at

Euston Station.

|

“The Grand Entrance is formed of a majestic Doric

portico, similar to the Propylea of the Greek cities, with antæ and

two lodges on either side, forming offices for booking parcels, &c.

and extending about 300 feet in width, the centre being opposite to

a wide opening into Euston-square. It was erected by Messrs. Cubitt,

after the designs of Philip Hardwick, Esq., the successful architect

of Goldsmith’s Hall, City Club House, and other first rate edifices.

The proportions of this splendid erection are gigantic, and the

portico may be considered the largest in Europe, if not in the

world. The diameter of the columns is eight feet six inches; their

height forty-two feet; the intercolumniation twenty-eight feet,

forming the carriage entrance; and the total height, to the apex of

the pediment, seventy two feet. It is built of Bramley Fall stone;

of which, in this erection alone, above 75,000 cubic feet were

consumed.”

The

London and Birmingham Railway, Roscoe and

Lecount (1839).

“When the Great

Northern Railway was about to build a London terminus, Sir William

Cubitt declared that ‘a

good station could be built at King’s Cross for less than the cost

[£35,000] of the ornamental archway at Euston Square.’”

The History of the London and

North-Western Railway, Wilfred L. Steel (1914).

The

Grand Junction Canal, [1] the

Railway’s near neighbour for many miles, has changed little since it was opened at

the beginning of the nineteenth century. Although most of its wharves and docks disappeared with its trade

many years ago ― a change spurred on by the

opening of the London and Birmingham Railway

― the waterway would be immediately recognisable to Jessop and

Barnes, its

engineers, were they to return today, despite what to them would surely be an inconceivable

change in the character of the traffic it now conveys. [2]

Robert Stephenson, however, would find far

less resemblance between the southern section of the West Coast Main

Line (as it now is) and the railway that he built. Although much of the

civil engineering depicted in John Cooke Bourne’s idyllic scenes

remains, it is festooned with high tension cables and associated paraphernalia, tampered with by

track widening schemes [3] and

often obscured by modern development. Another very noticeable change

would be to the size and speed of the rolling stock, made

possible, in part, by the heavy (around 120 lbs per yard) continuous

welded steel rail laid on pre-stressed concrete sleepers in a bed

of crushed granite ballast. Likewise, colour

light signals have replaced the top-hatted ‘policeman’

with their flags and signal lamps, stationed in the open at points along

the line (they can be sometimes be glimpsed in contemporary scenes

by Cooke Bourne

and other artists). And were he to return, Stephenson could not help

but

notice the remarkable changes that have been made to

the Railway’s station architecture ― one wonders what he and

Hardwick would make of

today’s utilitarian but

æsthetically deprived termini.

Almost none of the Railway’s original station architecture survives, its stations

being altered, sometimes rebuilt and sometimes relocated

within a few years of its opening; and as a coup-de-grâce, the

remnants of the great termini at Euston and at New Street succumbed

to the demolisher’s wrecking ball, victims of the architectural vandalism of the 1960s

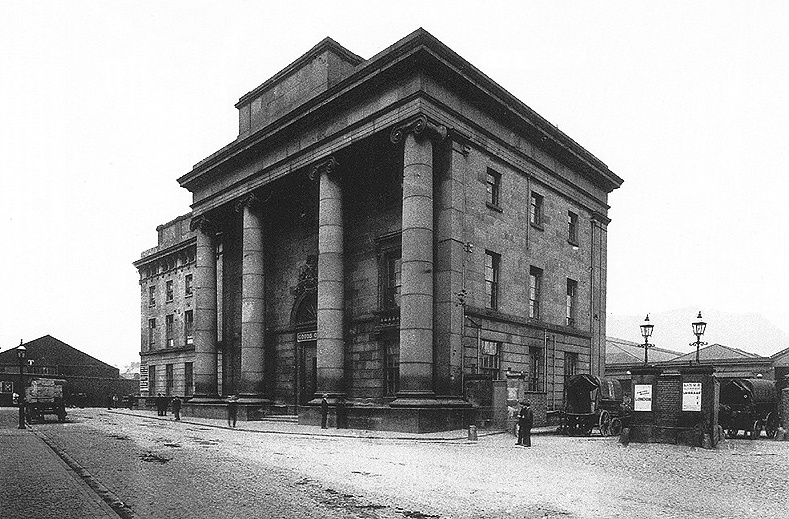

(part of Curzon Street ― Grade I. listed ― remains, although it

rather looks from its very sorry condition as if the building is

being encouraged to fall down!). |

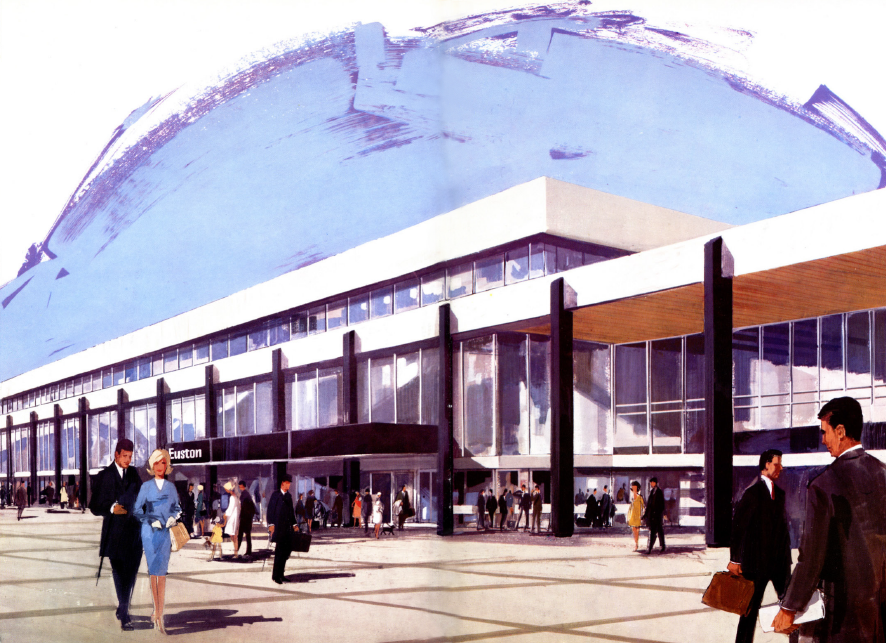

The New Euston, 1968.

|

This chapter draws on contemporary descriptions of some of

the London and Birmingham Railway’s principal stations as they existed during

its

early years.

――――♦――――

THE LONDON TERMINUS

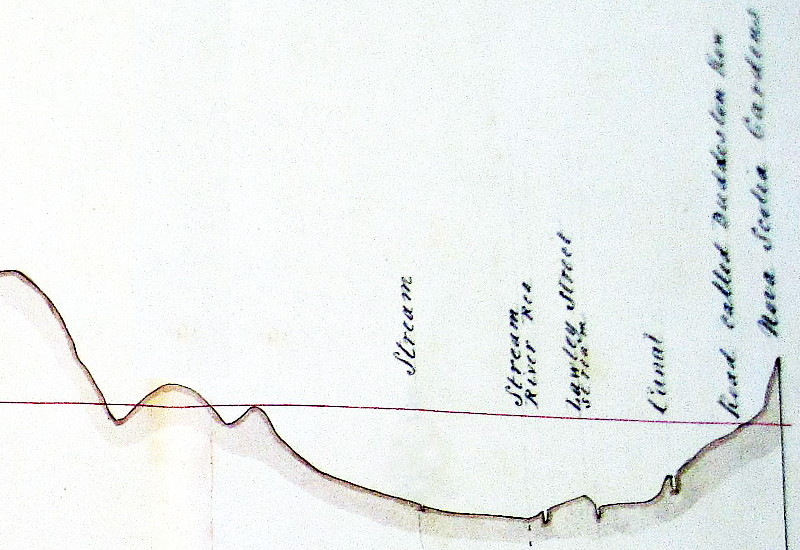

Stephenson’s first set of deposited plans for the Railway are dated November 1830. They show

its London terminus situated to the north of Hyde park,

west of the Edgeware Road and adjacent to

the confluence of the Grand Junction and Regent’s canals, an area

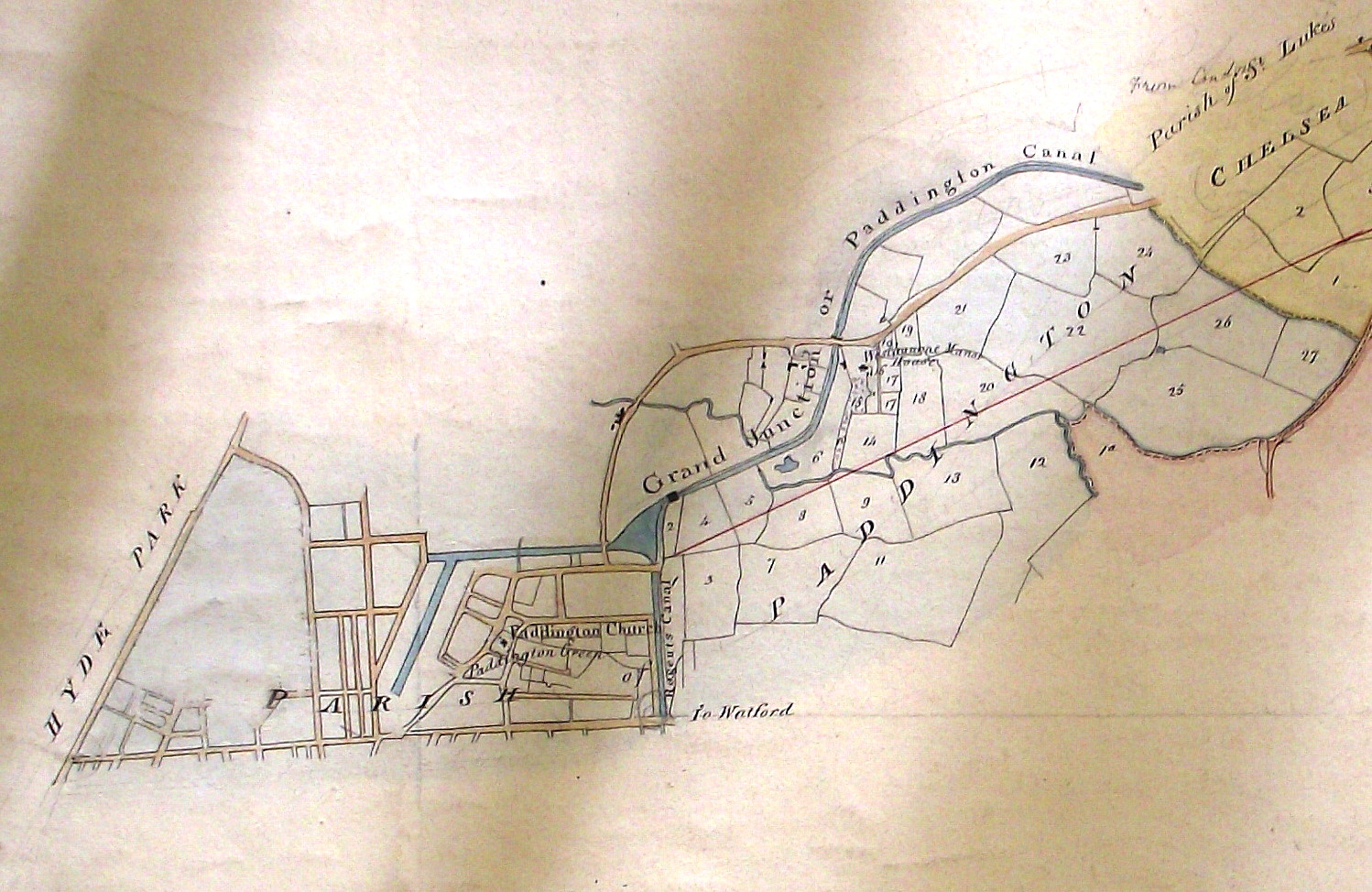

of west London now known as ‘Little Venice’. |

The London Terminus at

Paddington as conceived in 1830.

|

Stephenson’s second set of plans deposited in November 1831, show

the London terminus located at a point slightly to the north of Battlebridge Basin on the Regent’s Canal and adjacent to the present

day ‘York Way’, a name adopted in 1938 but at that time named

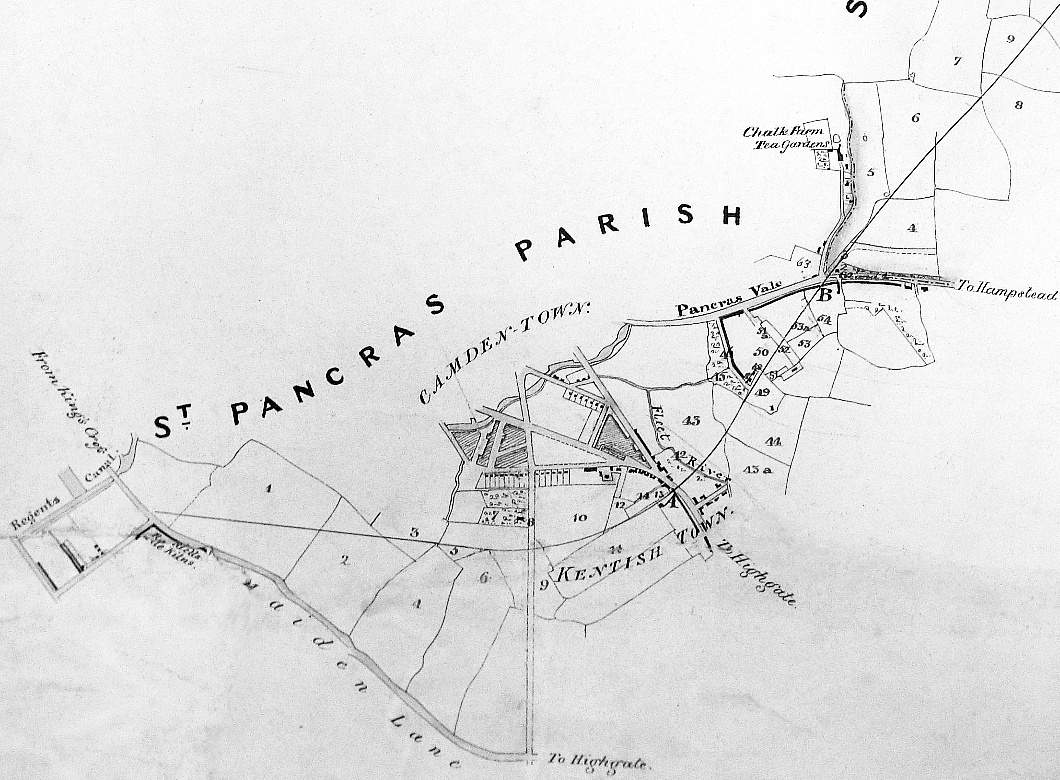

‘Maiden Lane’. |

Camden Town - plan dated

November 1831.

|

The area has changed greatly since 1831. At that

time it was populated mainly with market gardens and pasture:

“The line from Kilburn to Camden Town then ran through unbroken

country; and not only so, but the advance of the Hampstead Road,

considered as a street, had been so limited, that a thin crust of

houses, as it were, only lined its course; and with the exception of

crossing Park Street and the Hampstead Road itself, hardly a single

house of any respectable size was touched by the extension. To Park

Street, the line ran southward through fields of stiff clay pasture;

from Park Street to Hampstead Road, its site was chiefly occupied by

small and not very well tended market-gardens, and a little colony

of firework makers had their cottages or rather huts in this

intramural desert. South of the Hampstead Road, the fields and farm

buildings of a great milk purveyor reached nearly to Seymour

Street.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

Francis Conder (1868).

When applying for an Act of Parliament in the 1833 session, the Company’s intension was

by then to locate their London terminus north of the Regent’s Canal at

Camden Town,

and that is what Parliament authorised:

“V. And be it further enacted, That it shall be lawful for the

said Company and they are hereby empowered to make and maintain a

Railway, with all proper Works and Conveniences connected therewith,

in the Line or Course, and upon, across, under, or over the Lands

delineated on the Plan and described in the Book of Reference

deposited with the respective Clerks of the Peace for the Counties

of Middlesex, Hertford, Buckingham, Northampton, Warwick, and

Worcester, the Liberty of Saint Alban, and the City of Coventry;

that is to say commencing on the West Side of the High Road leading

from London to Hampstead, at or near to the first Bridge Westward of

the Lock on the Regent's Canal at Camden Town in the Parish of Saint

Pancras in the County of Middlesex, and terminating at or near

to certain Gardens called Novia Scotia Gardens, in the Parishes of

Aston juxta Birmingham and Saint Martin Birmingham in the County of

Warwick . . . . ”

The Act of 3 Gulielmi IV. Cap. xxxvi. for making a

Railway from London to Birmingham.

Passed 6th May 1833.

From the outset, the directors would have wished for a terminus nearer the centre of London and of business activity,

which would also

have permitted the Company’s freight and

passenger activities to be separated rather than collocated at Camden. However, to extend the line

further south

would have involved acquiring land from Lord Southampton, an

implacable

opponent of the Railway and a contributor to the parliamentary defeat of the first

London and Birmingham Railway Bill. Hence, the directors considered it

prudent to avoid confrontation with the noble lord. A further reason

[4] was to keep the

Railway’s construction cost within the parliamentary estimate of

£2,500,000, for to extend the Line further south, considerable engineering difficulties

would need to

be overcome in crossing London’s roads and sewers, and in allowing sufficient clearance over another obstacle that lay in the

its path, the Regent’s Canal.

However, following

passage of the first London and Birmingham Railway Act, attitudes

towards railways in general began to

change:

“Scarcely, however, had the line been begun, when Lord

Southampton began to entertain different views with regard to

railways. The success of George Stephenson’s lines, the Stockton and

Darlington and the Liverpool and Manchester, was admitted to be

beyond a doubt. The value of land adjacent to them had everywhere

increased, in some places had increased enormously. London residents

began to see that it would be to their interest to get the London

and Birmingham terminus as near them as possible; and Lord

Southampton perceived that the extension of the line through his

estate would greatly increase its value.”

The Life of Robert Stephenson,

J. C. Jeaffreson (1866).

In the light of changing attitudes, Stephenson suggested to the Board that they

locate their terminus nearer the centre of London; according to Jeaffreson,

this suggestion

“was rewarded with an emphatic and almost unanimous snubbing

by the gentlemen assembled who feared to take so bold a step.”

But the Board eventually saw sense. The necessary land was purchased, including a large tract at Euston

from the Duke of Bedford, [5] and application

was made to Parliament for an Act to authorise the line to be

extended southwards from Camden Town:

“The Directors believing that it would be for the interest of the

Company that passengers by the railway should have a nearer access

to the metropolis than is afforded by the station at Camden Town,

caused surveys and estimates to be made of a line, which the

Engineer recommended, about a mile in length, without tunnel, from

the present termination to Euston Grove. Having ascertained that no

opposition will be offered to the measure, and the terms on which

the quantity of Land required for this purpose may be procured from

the respective owners, and that no more favourable or less expensive

line of approach can be found, the Directors recommended to the

Proprietors that this extension of the line should be adopted.”

The Birmingham Gazette, 23rd February 1835.

And here lies a ‘might have been’; how would

Euston look today if the Station had become a joint

terminus with the Great Western Railway? For a time this was

considered possible,

for while the Euston extension was being

planned, the Great Western

Railway Bill, then before Parliament, had been drawn up to reflect a ban imposed by the Metropolitan Road Commissioners

on the

line crossing certain highways to the

west of London. The outcome was that the Great Western Railway Act

(1835) specified a terminus in the

vicinity of today’s Willesden Junction, [6] the intention being that

the line would continue from this point over shared track to a

terminus adjacent to that of the London and Birmingham Railway at

Euston. Sufficient land was therefore bought on which to

construct four tracks into Euston and to accommodate both stations.

Fortuitously, as things turned out, negotiations with the Great Western

Railway Company broke down

leaving the London and Birmingham with a wider trackbed into Euston and more land on which to site their

terminus than the Company would

otherwise have acquired, and which their operations soon grew to

fill.

The Act authorising what became known as the ‘Euston Extension’ received the Royal Assent in May 1835:

“WHEREAS an Act was passed in the Third

Year of the Reign of His present Majesty, intituled An Act for

making a Railway from London to Birmingham; and by the said Act

several Persons were incorporated, by the Name and Style of ‘The

London and Birmingham Railway Company’ for carrying into execution

the said Undertaking: And whereas it is expedient that the Line

of the said Railway should be extended from its present Commencement

near the Hampstead Road in the Parish of Saint Pancras in the County

of Middlesex to a certain Place called Euston Grove, on the North

Side of Drummond Street near Euston Square, in the same Parish and

County . . . . ”

The Act of 5 & 6 Gul. IV. Cap. lvi. [7].

RA 3rd July 1835.

The Act went on to set the character of Euston Station down to the

present day, as a passenger-only terminus:

“CXIII. And be it further enacted, That it shall not be lawful

for the said Company to receive at their intended Station in Euston

Grove, for the Purpose of Transport, or to deliver out therefrom,

any Merchandise, Cattle, or Goods of any Description, save and

except Passengers Luggage and small Parcels.”

The Act of 5 & 6 Gul. IV. Cap. lvi. [7].

Passed 3rd July 1835.

And so the site of the London terminus was transferred from Camden

Town to Euston

Grove:

“At the London end of the line near Camden-town, the company have

about thirty-three acres of land, intended as a depot for the

buildings, engines, wagons, goods, and various accessories of the

carrying department of the railway. At Euston Grove they have a

station of about 7 acres for the passenger traffic, and both

stations are connected by the extension line. Passenger trains are

to be moved on this portion of the railway, by a stationary engine

in the Camden depot, and locomotive engines are to be employed on

every other part of it. At the Birmingham end of this line, the

company have a station of about ten acres, which will serve both for

passengers and goods. The arrangement of these stations, and the

plans for the necessary buildings and machinery connected with them,

have been maturely considered, and the contractors are under

penalties that the various works in London shall be completed by

June next (with the exception of the facade of the Euston station

for which three months more are allowed) and the works in Birmingham

by November next.

The entrance to the London passenger station, opening immediately

upon what will necessarily become the grand avenue for travelling

between the Metropolis and the Midland and Northern parts of the

Kingdom, the directors thought that it should receive some

architectural embellishment. They adopted, accordingly a design of

Mr. Hardwick for a grand but simple portico, which they consider

well adapted to the national character of the undertaking.”

Directors’ Report to the Proprietors, February 1837.

In December 1835, the contract to build the Extension was

let to W. & L. Cubitt at a price of £76,860 (the outturn

was £91,528). Francis Conder, who as Fox’s pupil probably worked on

the Extension, referred to the extent of the civil

engineering difficulties to be overcome:

“In the two miles (sic) of extension from Camden Town to Euston Square,

the engineers had to solve nearly every problem which has

subsequently to that time been encountered by the projectors of

metropolitan railways. The canal had to be crossed under heavy

penalties for interfering with its traffic. The alteration of an

inch or two of level in the great highways was a matter of keen

debate in committee, and the execution of the parliamentary

conditions was closely watched by the courteous vigilance of Sir

James Mac Adam. [8] The sewers had to be avoided or provided

for. Nearly half the bridges that were constructed were insisted on

in order to provide for future roads, and intended streets and

crescents. The gradients were of, what was at that time considered,

unparalleled severity, so much so that the idea of running trains

propelled by locomotives from the terminus was laid aside; a

powerful winding engine was erected at Camden Town, and a cumbrous

but well considered apparatus of ropes and pullies was laid down, in

order to draw the trains up the inclines of 1 in 75, and 1 in 66.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

Francis Conder (1868).

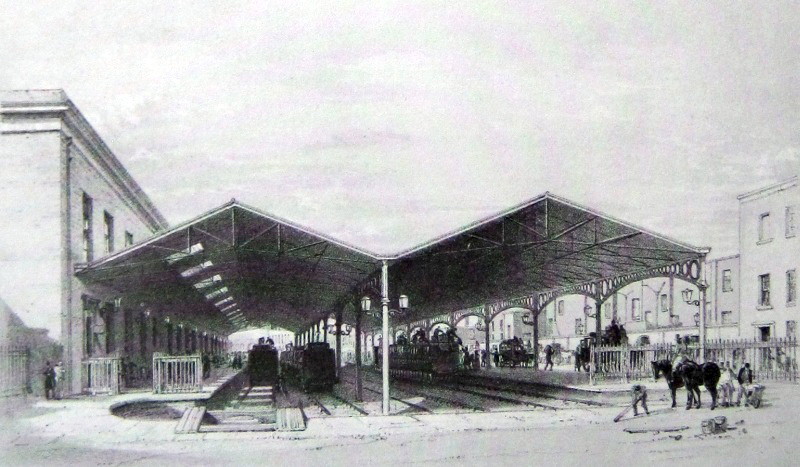

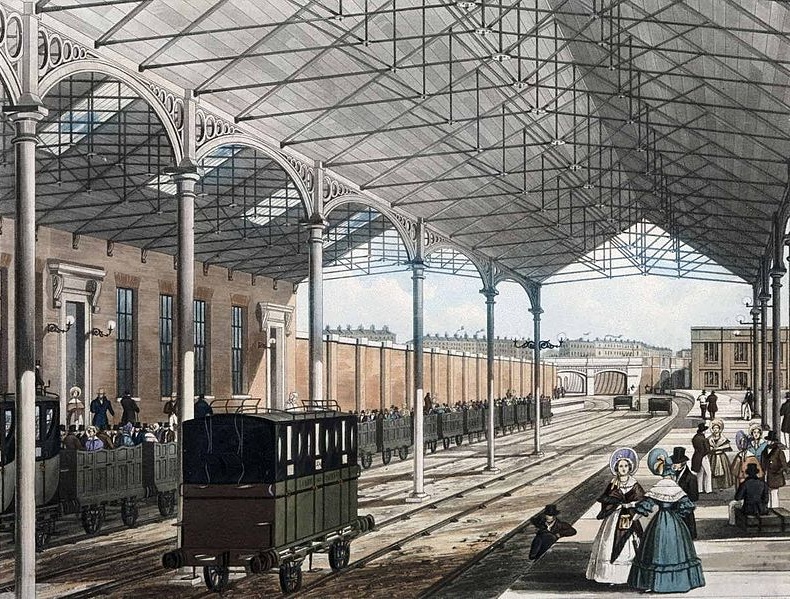

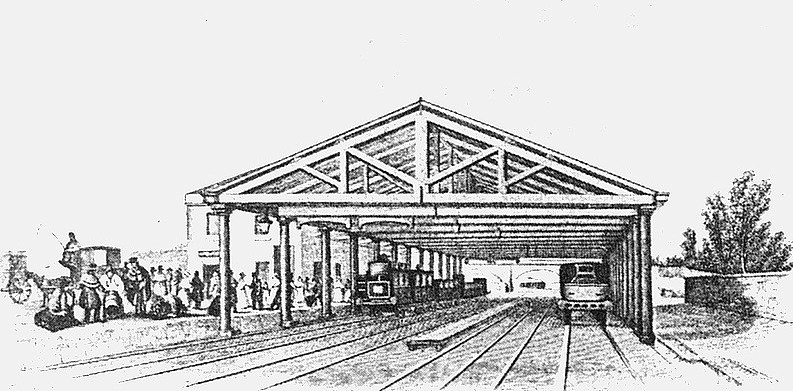

“Euston Station arrival and departure shed, for

sheltering carriages and passengers, on departing from, or arriving

at, London”

by John Cooke Bourne, May

1839.

Euston Station opened for business on 20th July 1837 to become London’s

first inter-city railway station. Robert Stephenson planned

its layout, the architectural frontispiece ― including the famous

‘Doric Propylæum’, or ‘Portico’, completed in 1840 ― was by Phillip Hardwick

(1792-1870), and Charles (later Sir Charles) Fox designed the train

sheds. [9]

Apart from the platform coverings and

Portico, the original station buildings consisted of a

narrow two-storey building adjacent to the departure platform. This building,

which had

a single-storey

Greek Doric colonnade projecting along its western or entrance

front,

contained the booking offices. The

departure platform thus became known as the “colonnade platform” ― the colonnade

is just visible through the central arch of the

Portico in Bourne’s famous drawing.

The Euston Train Shed

― the Colonnade is on the opposite side of

the building on the right.

“There are four lines of way at this station, which terminate in

as many turning platforms contiguous to the carriage wharf; the

whole width of this shed is 80 feet, and the length 200 feet; the

roof is constructed of iron rafters, strutts, and ties, and presents

a light and pleasing appearance. At the north end of the shed are

four corresponding turn-tables from which the four lines of way pass

with a quick curve towards the first bridge, which carries Wriothesley Street over the railway. A cross line intersects the

main lines at a distance of 240 feet from the north end of the

passenger shed, furnished with four turn-plates for the purpose of

conducting the carriages to or from the carriage-house.”

The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland

Practically Described, Francis Wishaw

(1842).

Charles Fox’s train shed

with the Departure Platform on the left.

Osborne paints an interesting picture of a first-time rail

passenger’s experience on arriving at Euston to board a train:

“. . . . the omnibuses and carriages enter under the centre of

the portico, and the foot passengers at their right side on the

causeway, between the pillar and wall. Policemen, in the dark green

uniform of the company, are stationed about the entrances, and are

always ready to give directions to any person needing them.

On passing under the portico, a range of buildings is observable to

the right, the upper part of which is used as offices for the

secretary, and other functionaries, located at the London end of the

line. Moving onwards, we enter beneath a colonnade, and presently

arrive at the booking offices, where a short time previously to the

starting of a train, a number of persons will be found waiting to

pay their fares. Behind a large counter are stationed a number of

clerks, displaying the usual bustling, but still we may say a rather

more methodical appearance, than their professional brethren at the

coach offices; this latter semblance, doubtless, results from the

system that is adopted; a rail in the office is so constituted as to

form with the counter a narrow pass, through which only one

individual can pass at a time, and into this the travellers go, and

are thus brought, ad seriatim, before the booking clerk. Into

this pass we enter, and wait patiently listening to the utterance of

names of stations to which persons are going, such as Coventry,

Tring, Birmingham, &c., till those before us are booked to their

respective stations; when our turn comes, we mention the place we

are going to, and the station nearest it is named, together with the

fare to that station; this sum we pay, and receive a ticket which is

forthwith stamped for us, on which the number of the seat we are to

occupy, and all other necessary directions are printed.

Ticket in hand, we proceed forwards through an entrance hall, and

emerge beneath the spacious shedding, round which the traveller can

scarcely cast a wondering gaze, when he is assailed by a policeman,

who in a hurried tone cries ‘number of your ticket, sir;’ having

obtained a glance of the ticket, the official immediately points out

its owner’s seat in the train and then hastens away to perform

similar duty to others.”

Osborne's London & Birmingham Railway Guide,

E.C. & W. Osborne (1840).

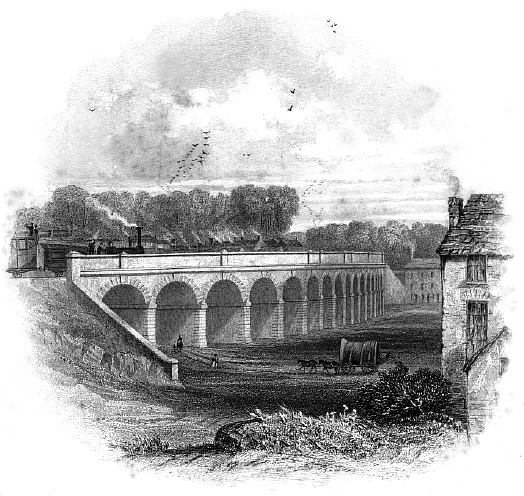

. . . . and were travellers to arrive at either terminus during

hours of darkness, the scene would be lit by gaslight:

“The preparations for lighting the Euston

Square, Camden Town, and Birmingham stations, took up considerable

time and labour. These stations are all supplied with gas, by

contract, on very fair terms, from Gas Companies whose works are

adjacent to them; large mains being laid throughout the whole of

them, from one end to the other, in situations which admit of

smaller mains being brought into all the various buildings; from

these branch off pipes of different sizes, so as to convey the gas

into all the various rooms and offices, passenger sheds, engine

houses, coke vaults, carriage sheds, &c., as well as generally about

the ground, in sufficient numbers to give an efficient light, and at

the same time with due regard to economy. It was also found

necessary to light up the whole of the extension line between Camden

Town and Euston Square, and at the Birmingham end provision is made

for the lights to be continued to the end of that noble structure

the Lawley-street Viaduct; proper gas meters are fixed in places

which ensure the quantity burned being correctly ascertained.

The locomotive goods departments having each separate meters to show

their respective consumption.”

The History of the Railway Connecting London and

Birmingham, Peter Lecount (1839).

The Ground Plan of Euston

Station shows the original layout, including the positions of

the Portico, Colonnade, Booking Hall, Departure and Arrival

platforms, turntables and the “cross lines”.

The

Victoria and

Euston hotels face each other across Euston Grove (ca.

1840).

Euston did not remain in the condition depicted by Bourne for long. A programme of building and extending soon began that was to

continue throughout most of the life of the ‘old’ Euston Station. More land was acquired from Lord Southampton on which to build

two hotels. Opened in 1839, the world’s first railway hotels ―

named the Victoria and the Adelaide (later renamed the

Euston) ―

flanked the approach to the Portico. The

Victoria was merely “a coffee house with dormitories”, [5]

but the Euston was intended for use by the gentry and

offered a full hotel service:

“These may be regarded as portions of the Station, having being

erected by the Railway Company, to afford local accommodation for

passengers. Like all other parts of this gigantic undertaking, these

buildings are on a spacious and handsome scale: they were designed

by Philip Hardwick, Esq. and have been erected by Messrs. Grissell

and Peto, with that rapidity and excellence of execution which at

once demonstrates the powers and skill, as well as the modern

system, of the London builders. In the course of nine months, the

whole has been executed. The eastern buildings form the hotel;

consisting of commodious coffee-room, sitting-rooms, bed-rooms, with

dressing-rooms, baths, and other necessary domestic conveniences.

The corresponding pile, on the western side, is a coffee-house, with

apartments for lodgings. The whole is arranged and fitted up to suit

the habits and comforts of different classes of families, and single

gentlemen, who may require a residence in London either for a few

hours, one night, or for several days.”

Introduction to the Drawings of the London and

Birmingham Railway

by John C. Bourne, John Britton (1839).

“When the London and

Birmingham Railway Company . . . . extended their line from Camden

to Euston Square they built two hotels opposite the terminus ―

simple erections as regards architecture, being nothing more than

white painted walls, pierced with numerous windows, of which there

are no less than 350 on the several frontages. Many persons were

surprised at the boldness of such an investment of capital, in a

neighbourhood where few hotel-living visitors take up their abode;

but the hotels have proved to be very profitable. Belonging to the

Railway Company, they are leased to other persons, who look (and it

seems are justified in looking) to railway passengers as means of

amply supporting the two establishments ― between which there is an

underground communication. The charges are altogether beyond the

means of third-class passengers (for whom, indeed, railway companies

supply far too little accommodation); and nearly so beyond those of

the second. We are bound, however, to say, which we do from

experience, that the accommodation and service at either the Euston

or Victoria are excellent; and to shew the pressure of traffic, we

are told that notwithstanding the vast size of these houses, they

cannot insure rooms unless written for in the morning of the day

they are required.”

About Railways, William

Chambers (1865).

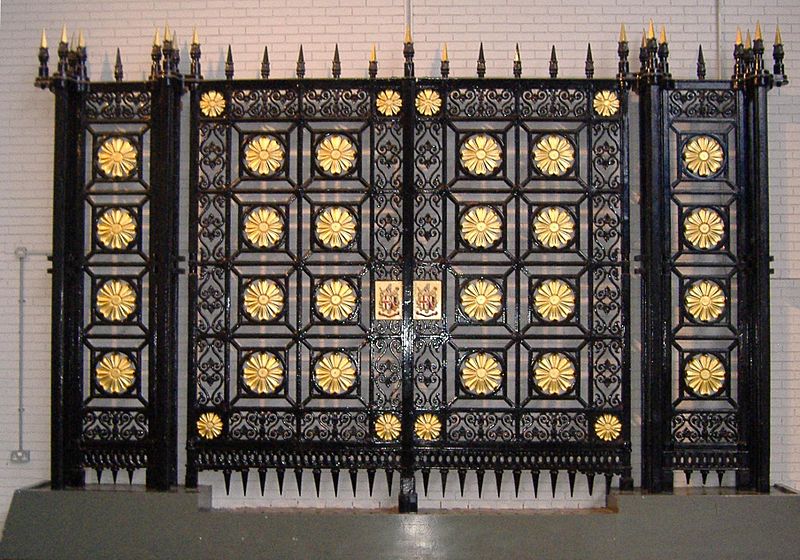

The main gates from

the Euston facade ― visible on the left in

Cooke Bourne’s

drawing

― were designed by

Hardwick and cast

by J. J. Bramah.

They are now in the care of the National Railway Museum

at

York.

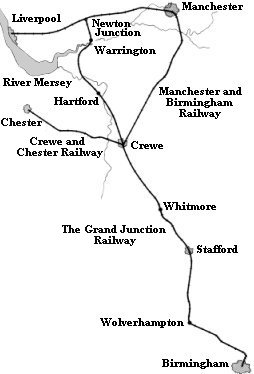

In 1846, the London & Birmingham

amalgamated with the Grand Junction and Manchester & Birmingham

railways to form the London & North Western Railway Company. The

merger

coincided with the start of significant new building work at Euston,

which included a

meeting room, board room, general offices, booking offices and the

majestic Great Hall, the latter being the work of Hardwick’s son,

Philip Charles Hardwick (1822-92).

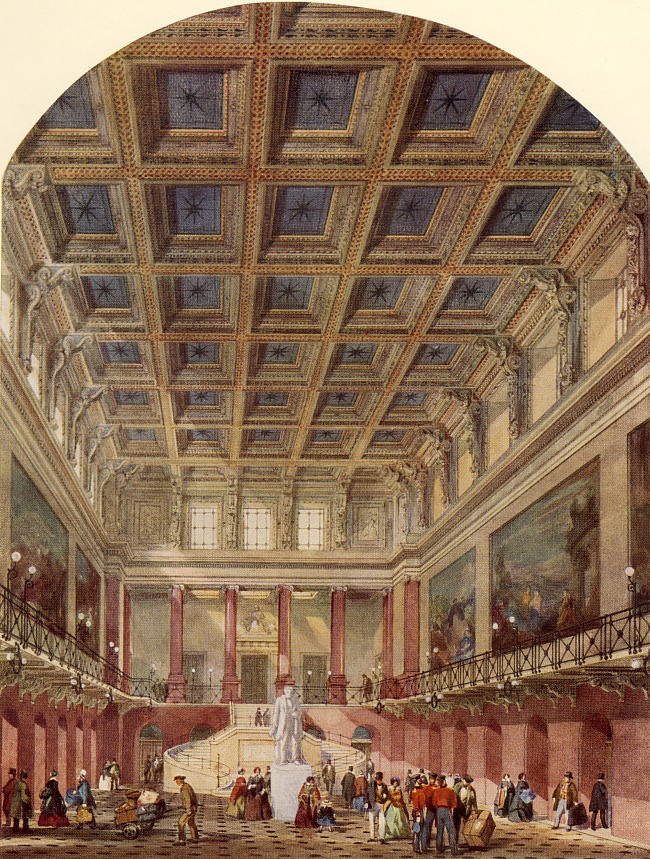

An artist’s impression of the Great Hall.

It was brought into

public use on the 27th May 1849.

The murals depicted were never painted . . . .

|

“. . . . its architecture, based on

Greek temples, was deemed a fitting gateway to the

capital and an introduction to the engineering marvels

of the railway beyond . . . . commissioned to celebrate

the creation of the London and North Western Railway in

1846, this was to be Euston’s new booking hall. The room

immediately impresses by its great scale. Added to this

are the double-flight stairs, graceful gallery and

elaborate mouldings. Above, the magnificent coffered

ceiling, actually built of iron, stretches across the

hall’s great width. This is not what we imagine a

booking hall to look like: the porters, laden with heavy

trunks, seem most out of place here. Hardwick’s superb

design was executed, apart from the murals above the

balconies. Its demolition, with the rest of Euston

(1962), was regarded as one of the greatest acts of

Post-War architectural vandalism in Britain, the

campaign to save it leading to the foundation of the

Victorian Society.”

The Royal Institute of British

Architects. |

|

The Great Hall in the 1950s.

The Portico ca. 1938.

Compared with Bourne's spacious scene, the now grimy Doric arch is

boxed in by development,

one of its lodges has gone and the others are plastered with

advertisements.

|

――――♦――――

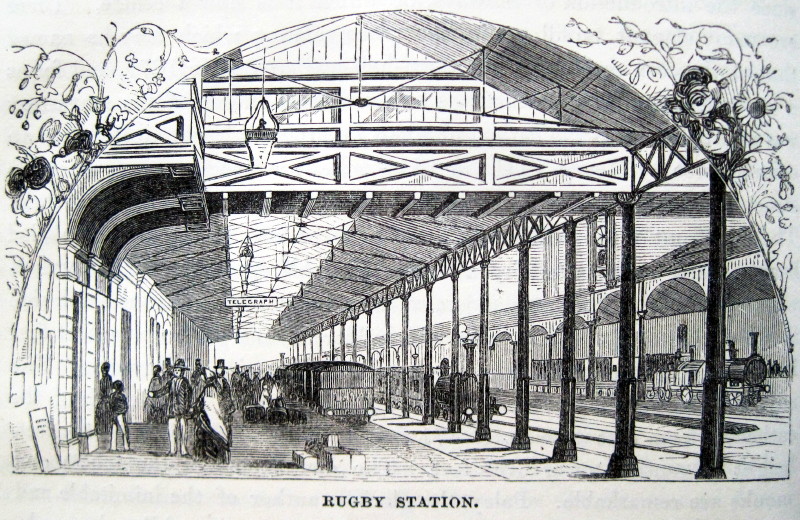

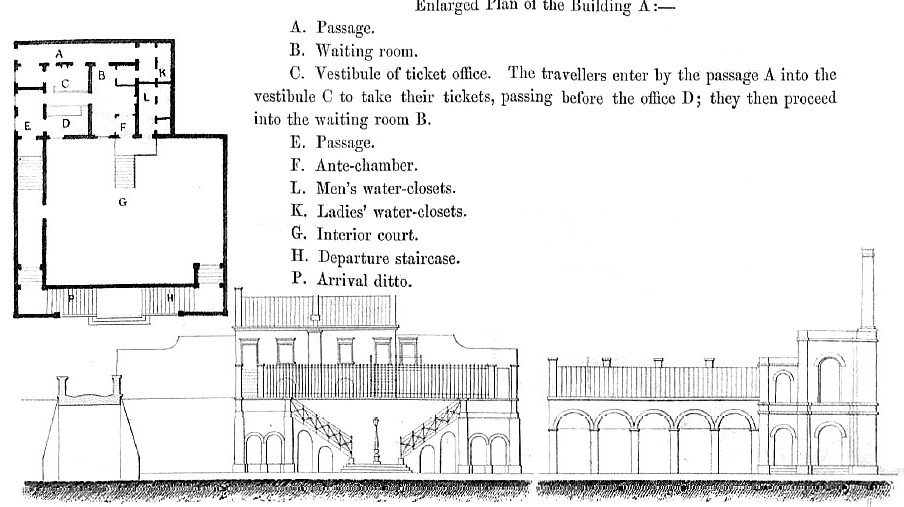

THE INTERMEDIATE STATIONS

“The intermediate stations call for little notice, most of the

roadside stations being very modest affairs with no platforms,

passengers entering or leaving the trains at both sides.”

History of the London and North Western Railway,

W. L. Steel (1914).

Descriptions of the Railway’s intermediate stations during its

early years exist in varying degrees. Several had a short life

and were soon rebuilt, sometimes in a

new location to cater for the opening of a branch (e.g. the

Saint Albans branch at Watford) or a junction (such as that with the

Midland Counties Railway at Rugby), for not only was our railway network

growing quickly during the 1830s and 40s, but

there was very little precedent in station design for their

architect, George Aitchison Snr. [35],

to work from. Thus, rebuilding ― with or

without relocation ― is hardly surprising. Peter Lecount explained the problems that

the Company faced in siting and designing their intermediate

stations:

“There is a great deal more difficulty than would at first be

imagined in laying out a railway station. If those now existing had

to be built over again, some change would be desirable: there are so

many things to be amalgamated, and such various accommodation to be

provided, that the business becomes exceedingly complicated. An easy

approach for the engines and trains, without bad curves ― a

convenient situation with regard to the town ― an easy access to and

from the engine house, and to the carriage sheds and repairing shops

― a proximity to water ― carriage facilities for getting coke and

water ― a convenient situation for the store department: these are a

few, among many desiderata, which render it very difficult to make

them all fall into the desired arrangement; but it may be said of

the London and Birmingham Stations, that as much has been made of

the ground as could, by any possibility under the circumstances.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Roscoe and Lecount (1839).

Despite the design problems, by February 1837 the Chairman was able to

report to the General Meeting that:

“The plans and specifications of the buildings at the intermediate

stations are in progress, and the whole of this portion of the work

will be completed against the opening of the railway. The greater

part of the locomotive-engines required to convey the trains of

passengers and goods, and of the necessary carriages of all

descriptions are also contracted for, and will be delivered in

succession as they are required to meet the wants of the Company.”

Report of the 7th

half-yearly General Meeting, Northampton Mercury, 18th

February 1837.

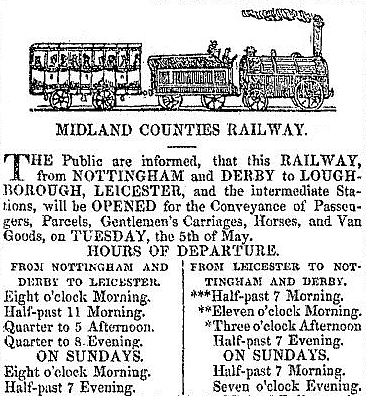

The Railway opened with sixteen intermediate stations. They

fell in two classes, first and

second, the distinction being that ‘first-class trains’

(comprising just first-class accommodation) and mail trains stopped only at the first-class stations, while ‘mixed trains’ stopped at

every station. The first-class stations together with their distance in miles from Euston,

were at

Watford (17¾), Tring (31¾), Leighton (41), Wolverton (52½),

Blisworth (62½), Weedon (69¾), Rugby (83¼) and Coventry (94). In the

second class came Harrow (11½), Boxmoor (24½), Berkhamsted (28),

Bletchley (46¼), Roade (60) ― later redesignated first-class due its

important stage coach connections to Northampton, Leicester,

Nottingham and further afield ― Crick (75½), Brandon (89¼) and Hampton

(103).

To allow for the transfer of passengers following the

opening of the Aylesbury Railway in 1839, the Company erected what

was probably no more than an interchange platform named ‘Aylesbury

Railway Junction’. [10]

In addition to the number of train services they attracted, a

further distinction between

the two classes of stations lay in their

facilities. In his

Treatise on Railways,

Peter Lecount described the general characteristics

of railway stations of the period:

“The minor

stations along the line may be divided into two classes. The first

might consist of merely one room, serving for office and

waiting-room, where nothing but passengers and small parcels are

sent either up or down. Such stations would do for small villages or

points where only a limited traffic is expected. We do not, however,

recommend these, although they are used on several railways. All

passengers pay alike, and they are therefore entitled to the same

accommodation. The other class should be a house containing an

office, waiting-room in common, or which is better, one for each

class of passengers, ladies’ waiting room, and two rooms for the

inspector of police to reside in, a small office for the police, and

a porter’s room. To this would have to be added, if water was

required to be pumped, a steam-engine, and the requisite room for

the engineer, a locomotive engine-house when necessary, and a

covered space for holding spare carriages, trucks, horse-boxes, &c.,

together with the requisite sheds, and an office for the goods

department.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Peter Lecount (1839)

Francis Wishaw left a brief description of the London

and Birmingham Railway’s second-class stations:

“A second class station on this railway consists

usually of a building in the cottage style, in which are

the booking-office and waiting room, a front court

enclosed with space and pale-fencing, and the usual

conveniences, with separate gates for the arrival and

departure of passengers.”

The Railways of Great Britain and

Ireland Practically Described,

Francis Wishaw (1842).

――――♦――――

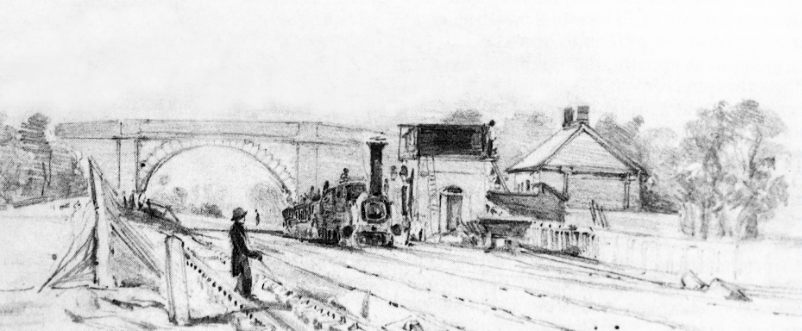

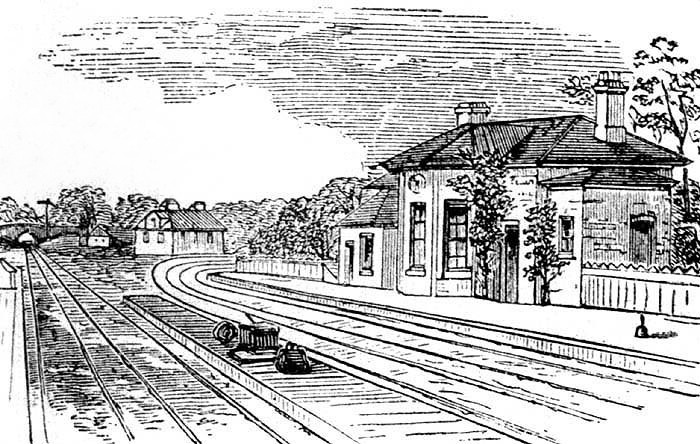

HARROW

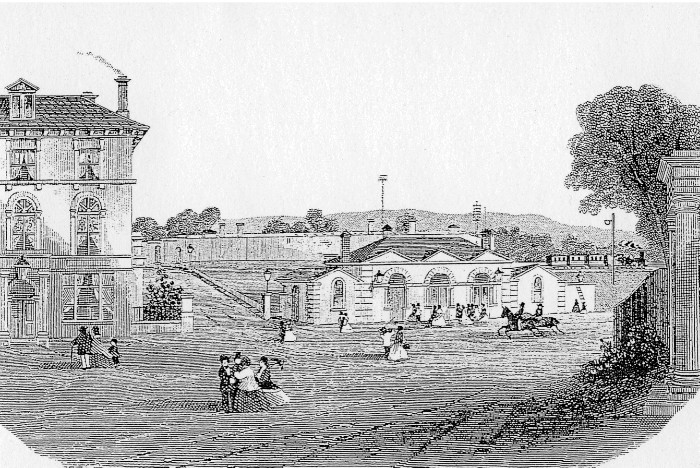

Harrow Station looking South, ca.

1837.

The locomotive travelling wrong line appears to be heading a works

train.

Harrow Station, the

London and Birmingham Railway’s first stop after Euston, opened on

the 20th July 1837:

“The Harrow Station is a neat brick

building, with an enclosure in front, where passengers who intend to

go by the next train may walk about at leisure, after booking their

places; or, should they prefer to repose themselves within doors,

commodious waiting rooms are provided. A similar arrangement is

observed here, as well as throughout the whole of the line, in order

to prevent confusion amongst passengers, arriving or departing; as

separate entrances are provided for each class of passengers, and

the utmost order and regularity prevails, even if there be a number

of persons going to and from the stations at the same moment.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Roscoe and LeCount (1839).

As can be seen from the drawing, the station building was of modest

single-storey construction. It was built by Thomas Jackson of No. 1 Wharf,

Commercial Road, Pimlico for the sum of £663. It will come as

no surprise that the Headmaster of Harrow School, fearful for what

he imagined would be the Railway’s detrimental effect on the

discipline of his pupils, asked that the station be built at Wembly,

but by the time the Directors had received his complaint the station

was a fait accompli.

――――♦――――

WATFORD

|

|

|

The original Watford

Station booking office. |

Watford Station was the first principal station north of Euston,

where the locomotives of first-class and mail trains made their

first stop for water and coke (second class trains having stopped at

the intermediate or ‘second-class’ station at Harrow). The

small brick and slate building shown above was the original station’s

booking office, and is one of two surviving examples of the Railway’s

early intermediate station architecture, the other being the

original Hampton Station, built by the

Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway.

Built in 1836-37 by William Starie of Houndsditch (for £1,355) to a

design by George Aitchison Snr. ― as were the other original

intermediate stations ― it was located at street level to the north

of Saint Albans Road and on the eastern side of the line:

“Passing onwards through Primrose-hill and Kensal-green tunnels,

and Harrow, we arrive at Watford. At this station tickets are

collected from passengers arriving by the up-trains from Birmingham. The station is fitted up with booking-office, passengers’-room,

ladies’ waiting-rooms (elegantly furnished), inspector’s-room,

porters’-room, stationary engine-house, with an engine of four-horse

power, used to throw up water into the tank above for supplying the

locomotive engines (on their requiring it) on their arrival at the

station; a repairing-house, fitted up with furnaces, lathes, and all

necessaries for that department. The whole station is covered with a

light corrugated iron roof.”

The Bucks Herald, 7th

September 1839.

The specification was similar to that for the first station

at Harrow. Materials were to be ‘none but the best’, with

‘none but well seasoned Oak (English)’ and ‘best Duchess slating’ to

cover the roof, not only of the offices but also the privies. Portland stone

was specified for the parapet and gables, window sills, and ‘hearth,

chimney piece and shelf’ and the entrance was to have steps of York

stone. Finally the woodwork was to be painted with five good coats

of oil and colour’. As at Harrow, there were to be ‘Inscription

Tablets’ on which ‘London and Birmingham Railway’ had to be written,

although here the size of the lettering was left for later approval.

The “repairing-house” mentioned above is now usually referred

to as an engine shed; there was also a carriage shed.

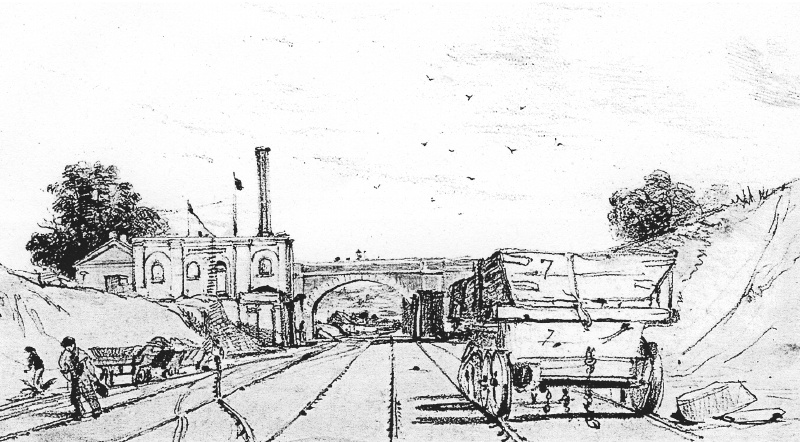

Watford Station,

looking south. The booking office to the left of the main building

survives.

The original ticket office (shown in the preceding

photograph) appears

in the above drawing, beneath the tree on the left. The

chimney is probably associated with the stationary engine-house in

which the 4hp pumping engine referred to in the Bucks Herald

article was installed.

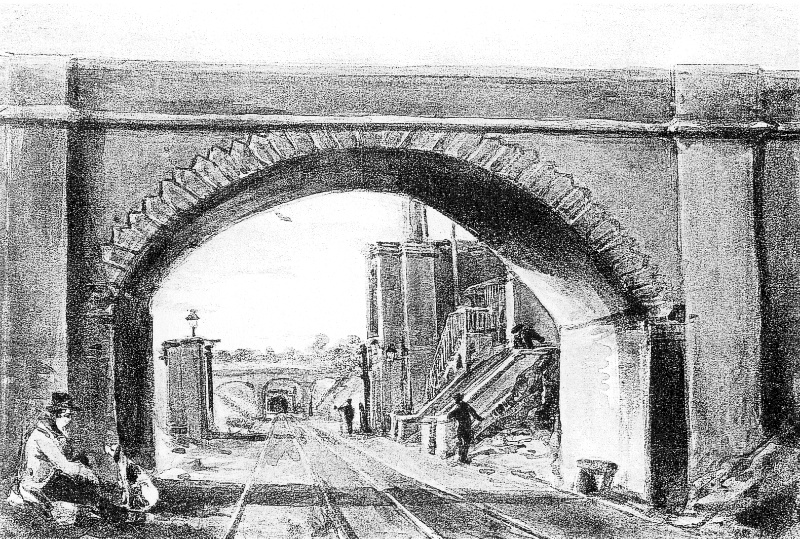

Watford Station

looking north towards Watford Tunnel,

showing the steps down from

street level (no platform). |

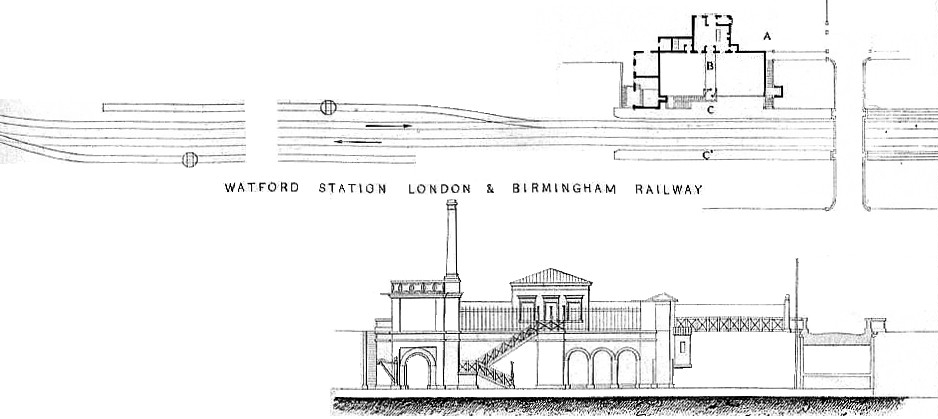

Outline drawing of Watford

Station as originally built.

Our thanks go to Tom Nicholls for bringing this

drawing to our attention. It appears in

First [fourth] series of railway practice: a collection of

working plans and practical details of construction in the

public works of the most celebrated engineers by S. C. Brees

(1847).

|

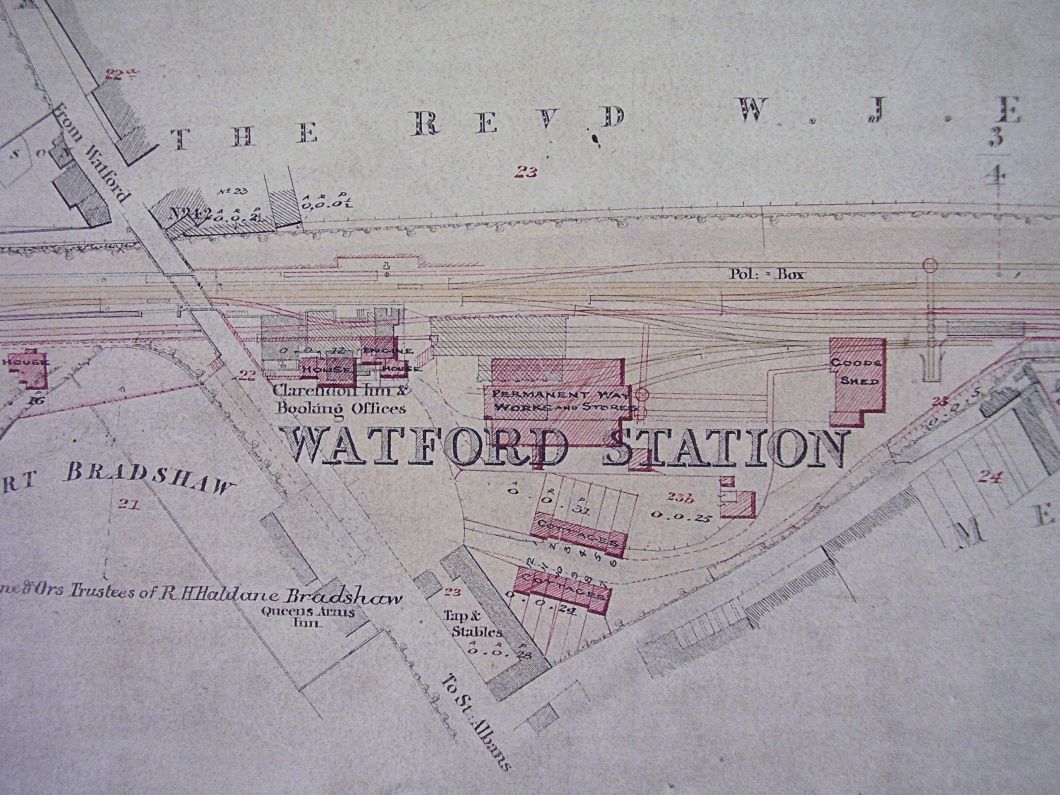

This undated plan of Watford Station

seems to be an amendment of an earlier plan, for some of the

original station buildings are now ‘blacked out’ — with a track

passing through their site — with only the buildings that accommodate

the booking office and the engine house remaining.

The plan shows that track widening took place after Watford

Junction station came into service. The position of the

Clarendon Arms (viz. above WAT), referred to above, is shown.

Image courtesy of Russell Burridge. |

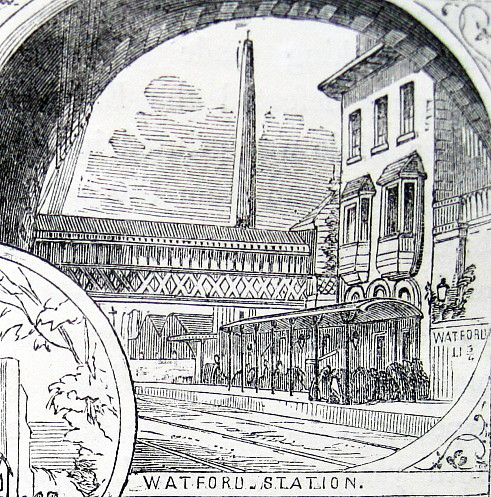

|

This sketch appears to

date from late in the life of the original station.

It shows the corrugated iron roof referred to in the

extract above, together with the chimney of the pumping

engine. By this date, the station has acquired

platforms and a footbridge that are not evident in

earlier depictions. |

Following the station’s opening, James Toovey,

a local entrepreneur, saw a business opportunity, which he set about

exploiting:

“London and Birmingham Railway ― In addition to the many great

improvements that have recently taken place upon this line of

railway, is to be noticed the establishment at the Watford station

of a large and commodious inn, by the title of the Clarendon Arms. The proprietor, Mr. James Toovey, of the Rose and Crown, Watford,

has spared no expense in fitting it up for the convenience of the

public. There are meeting rooms and every accommodation for

travellers by the railway; and horses and vehicles can be procured

at all hours of the day and night. The public have long required

this accommodation, and Mr. Toovey deserves great credit for the

spirited manner in which he has established the undertaking.”

Railway Times, 14th December 1839.

When the Watford to Saint Albans line was built, Watford Station was relocated some 150 yards further south,

at the junction with the new branch line. Renamed

Watford Junction, the new station opened for business in May 1858, and its

predecessor was closed, James Toovey’s large and commodious inn no

doubt suffering as a consequence.

Watford Junction Station, ca.

1858. |

|

――――♦――――

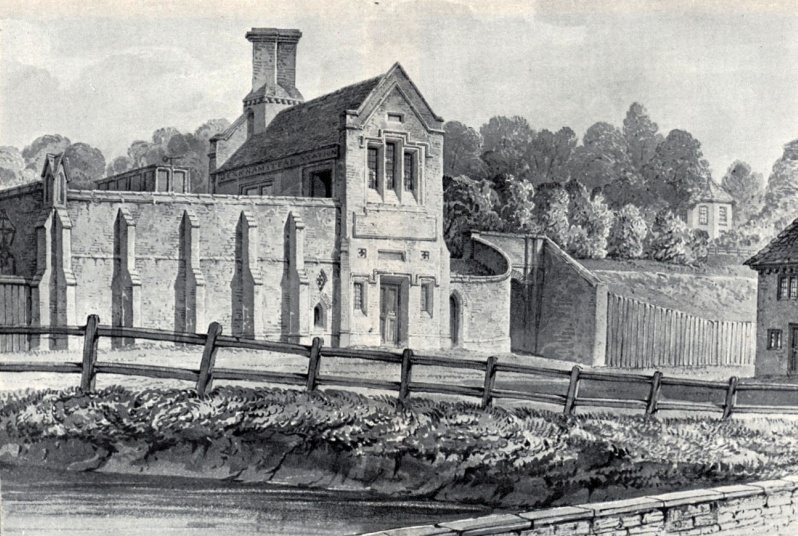

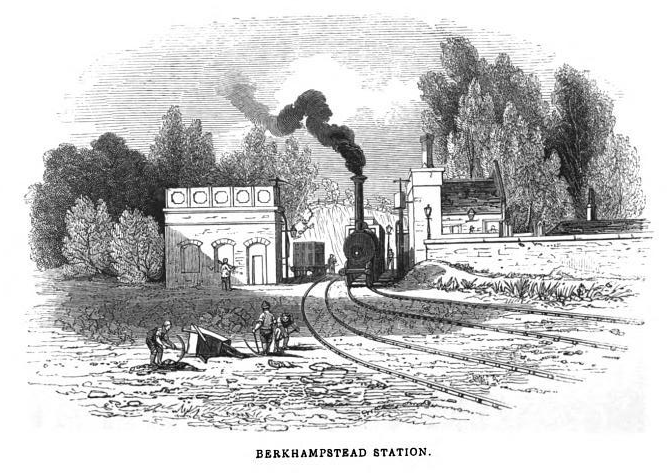

BERKHAMSTED

Although there are descriptions of several of the

Railway’s original intermediate stations, few images appear to have survived.

Of what there is, the old Berkhamsted Station ― described by John

Britton as

“built of brick, in the ‘Gothic’ style, with stone dressings”

― is well represented, probably on account of its distinctive

appearance. The station shown here was located some 100 yards to the south of the

present station, which, together with additional sidings, was built

in 1875 as part of the scheme to increase the line’s capacity with a

fourth track. The old

station was then demolished and no trace of it now exists.

――――♦――――

TRING

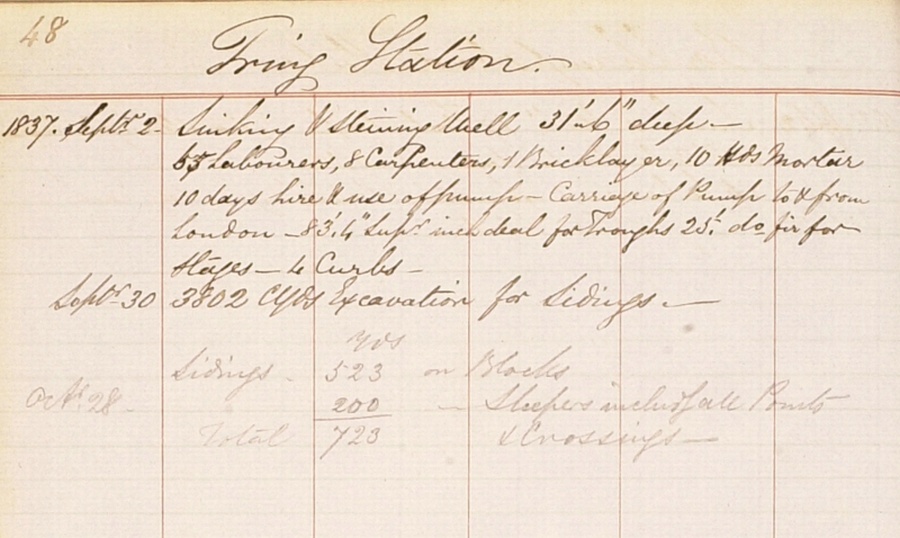

A

page from a London and Birmingham Railway civil

engineering record.

This

page records work done at Tring Station during September

and October 1837. It includes sinking and ‘steining’* a

well 31ft 6 ins deep, and excavating 3,802 cubic yards

for sidings, 523 yards being laid on blocks** and 200

yards on sleepers. 65 labourers, 8 carpenters and 1

bricklayer were employed, a pump was hired for 10 days

with transport to and from London, and timber was

obtained for troughs and stages.

* When excavating a well,

it is necessary to hold back the loose upper strata

until solid rock is reached. It is therefore necessary

to line the sides of the well with bricks, stone blocks or flints,

a process called ‘steining’.

** The blocks for the

sidings are

‘stone block sleepers’.

Following the invention of the wood preservative

creosote, stone blocks were soon replaced with cheaper

and more effective wooden sleepers.

The Comte d’Harcourt, absentee owner of the Pendley

Estate, demanded such an exorbitant price for land on which to build

Tring Station, that the Company decided to build the station some 3

miles further north on cheaper land at Pitstone Green. But

local demand for a station nearer the town resulted in its traders

offering to make good the difference between Harcourt’s asking price

and what the Company was prepared to pay. Thus Tring got its

station, but even after its citizens had built a new road to link

the two the town centre remained a good mile and a half from its

station.

Tring was designated a first-class station,

although at first glance its rural location makes its designation as

such difficult to understand. Part of the answer lies in the

town’s east-west road communications.

At a time when our public

rail network was in an embryonic state of development, Tring was the

nearest railway connection point for travellers ― from as far afield as Oxford to

the west and Luton to the east ― who wished to make, by the standards

of the time, a quick and comfortable

journey to London or Birmingham. In November

1837, a

four-horse coach service commenced between Oxford and Tring Station, arriving in time for

its passengers to join the third train

of the day for London, and then returning with any Oxford-bound

train passengers.

Other less obvious reasons for Tring Station’s status in its early

days lay in opportunities for both speculative building and good hunting

in the surrounding countryside:

“London and Birmingham Railway.―Amongst the many alterations and

improvements which have taken place since the formation of the above

line, there is no part which has progressed more with the times than

the vicinity of Tring. As soon as the Company had determined upon

making it a first class station (where every train stops) the

inhabitants came forward in a very spirited manner, and at their own

expense formed a new road direct to the town. Since then other

improvements have taken place, and adjoining to the station has been

erected the Harcourt Hotel, a very handsome building, capable of

affording every accommodation. The situation of this station is in a

very beautiful part of this county, in the centre of the estate of

the late General Harcourt; and in consequence of the demand for

houses in the neighbourhood, the present possessors have made

arrangements for accommodating the public with building ground at a

reasonable rate, so that in a short period we may calculate on this

spot becoming an important place. It has also become quite a

sporting district, many gentlemen who reside principally in London

finding it so extremely convenient to get to and from, that it is

treated as almost nothing to ride 40 miles to cover, and have a good

day's sport.”

Railway Times, 7th

December 1839.

The former Harcourt Arms Hotel,

Tring Station, is now an apartment block ―

a fine period piece with

large courtyard (on r.h.s.) and extensive stables (now mews houses).

The contract to build Tring Station was awarded to W. & L. Cubitt

for the sum of £1,885. Its architect, George Aitchison, must have been particularly pleased

with his handiwork, for in the Architecture section of the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1838, the

catalogue entry reads;

“975. View of the Tring Station of the London and Birmingham

Railway, erected in 1838, from the design and under the direction of

G Aitchison.” Aitchison’s handiwork is now long gone and

even his exhibition “view” of the station buildings cannot

now be found, but

Francis Wishaw’s detailed description does survive, even down to the number of steps between

platform and road levels:

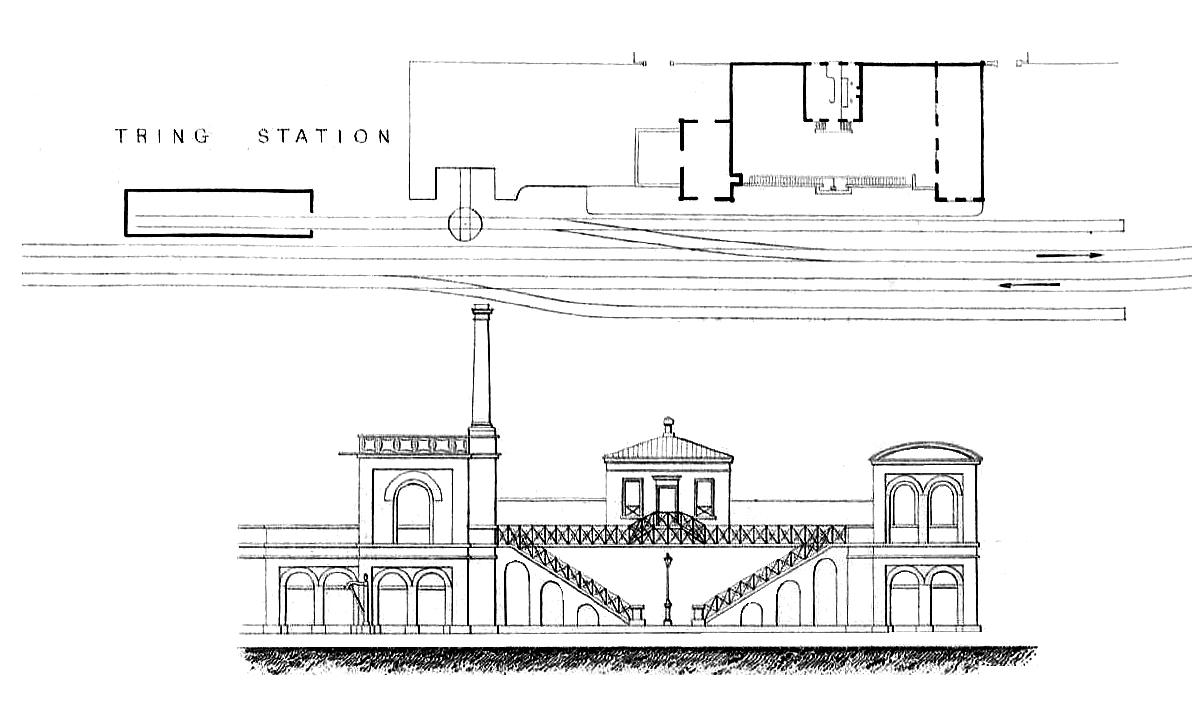

“TRING (FIRST-CLASS)

STATION.―The station at Tring is

inconveniently placed in a cutting, as was the original

Coventry

station. The offices are on an elevation equal to the depth of the

cutting, and are approached from the railway by a flight of 18½

7-inch steps for foot passengers, and a sloped road for the private

carriages to be embarked or disembarked at the carriage-dock. There

is a separate passage from the railway for the departure of persons

arriving by the trains, and also a separate staircase for the use of

the porters.

The offices consist of booking office and waiting-room in one, with

an entrance-lobby next the road, and exit lobby towards the railway.

The width of this building, which is constructed of brick, is 32

feet, and the depth 24 feet 5 inches. A paved yard extends in front

of the offices for a length of 58 feet, being 33 feet in depth; the

front next the railway is enclosed with iron railings. The urinals

and water-closets are conveniently placed on the north side of the

offices, and entered from the paved yard. There is also a porter's

lodge, which is detached from the other offices . . . .

Besides the booking-clerk, there are at this station one inspector,

three policemen, four porters, and one stationary engine-man.

The carriage-dock is approached by a siding from the main line,

furnished with a 12-feet turn-table opposite the entrance to the

dock. This dock is 14 feet in length 9 feet 5½ inches in width, and

3 feet deep.

Some of the ballast-engines are housed in a shed at this station.

One horse-box and carriage-truck are kept at this, as at all the

first-class stations.”

The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland

Practically Described, Francis Wishaw

(1842).

In an age before mains water became generally available,

Wishaw describes the well sunk at the Station from which to obtain water for

the locomotives, together with the pumping equipment necessary to keep the

water tank topped up. The use of the pumping engine’s exhaust steam

to provide feed water heating is interesting:

“The fixed-engine and boiler-house are about 33 feet in length and 18

feet 6 inches in width, and abut on the north side of the paved

yard. The coal-shed, which is contiguous, is 23 feet in length and

about 7 feet wide. The engine has an 8 inch cylinder and 18 inch stroke;

the usual working pressure is 31lbs. on the square inch. There are

two boilers, with return tubes. The water-tank is placed over the

engine and boiler-house; the usual depth is 3 feet 6 inches. The

quantity of water which this tank will hold is equal to the supply

of eight or nine locomotive engines. The supply-pipes from the pumps

are each of 6 inches diameter. From the boiler the waste steam is

admitted by a 2½-inch pipe into the water-tank, to raise the

temperature of the water previously to its being let into the tanks

of tenders.

The water used at this station being of excellent quality is taken

in by most of the locomotive engines; it is obtained from a depth of

80 feet, the well is of 7 feet diameter.” |

|

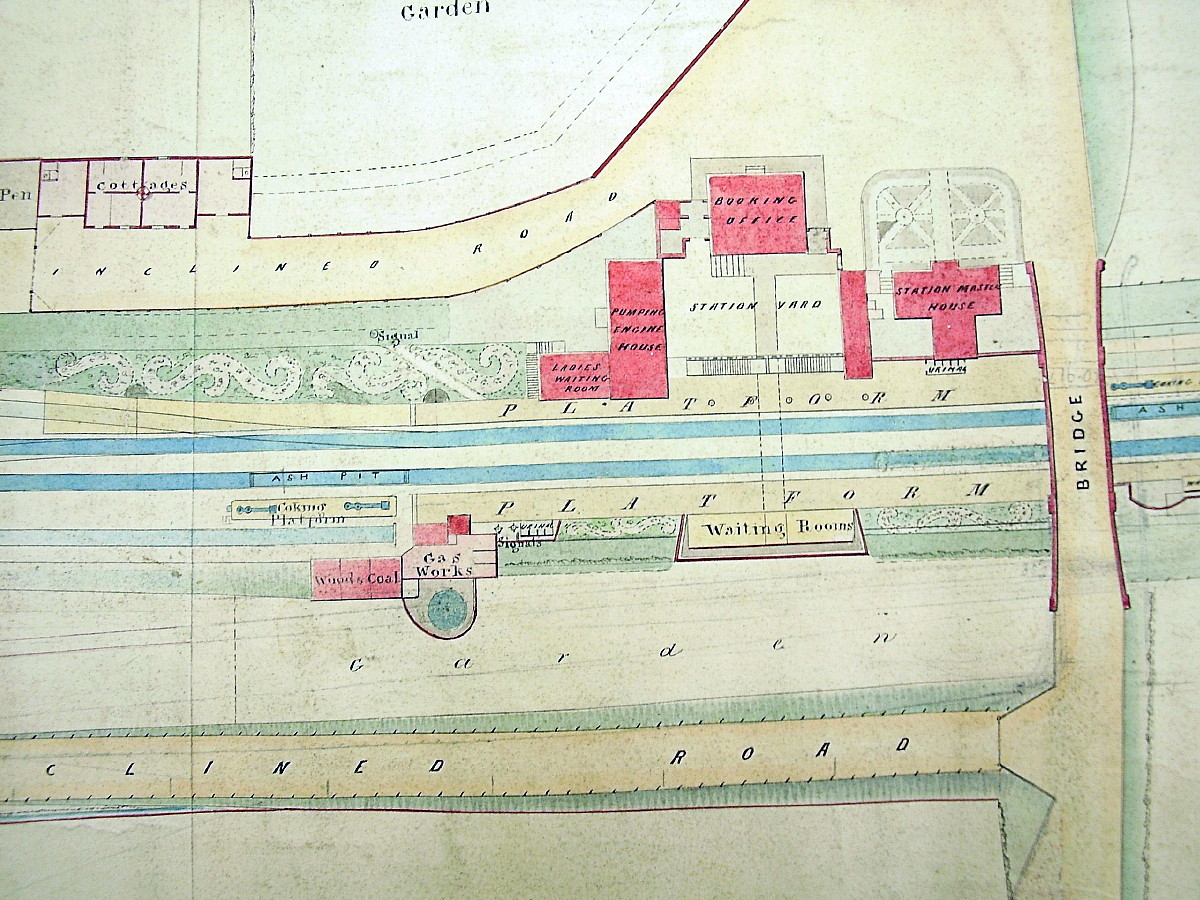

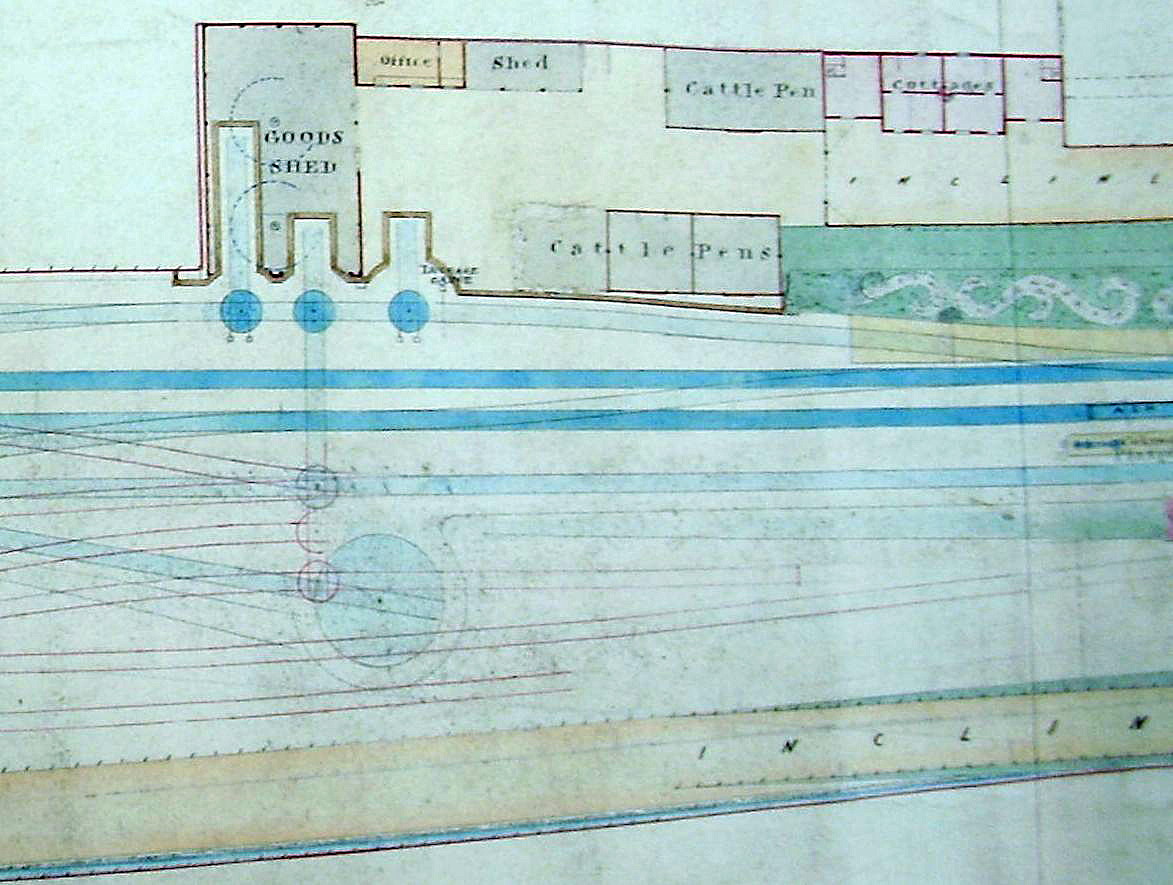

An early (pre-1860) plan of Tring

Station. The Booking Office and Station Master’s house lie on

the western side of the line. The plan below is of the section

adjacent to that above.

Our thanks go to Russell Burridge for providing

copies of the plans. |

|

The circles shown on the plan above are turntables — referred to at

the time as

“turn-plates”. They were such a novelty that Osborne gave a complete description of

the operation of what he described as a

“profound contrivance” in his guidebook (1840).

Referring to those serving the goods shed and cattle dock, he had

this to say:

“The mode in which heavy goods and carriages

are placed upon the trucks, is well worthy of notice. At the

Station there are several turn-plates on the line; they consist of

large flat circular iron plates, of twelve feet in diameter, with

two lines of railing on them, the one crossing the other at right

angles, the plate turning round on iron rollers beneath, and capable

of being moved with very little power. One of the trucks which

is to receive a carriage, or heavy goods, or a box for horses, or a

pen for sheep or pigs, is pushed on to one of these turn-plates, and

being turned to a right angle, is then passed up a short line of

rail to an embankment or stand of the same height as the truck, and

the animals, goods, or carriage placed on. The truck is then

taken back to the turn-plate, and turned on to the line again.

By this apparently simple, but in reality, profound contrivance, the

heaviest and most cumbrous loads are managed with the greatest

ease.” |

Outline drawing of Tring

Station as originally built.

Our thanks go to Tom Nicholls for bringing this

drawing to our attention. It appears in

First [fourth] series of railway practice: a collection of

working plans and practical details of construction in the

public works of the most celebrated engineers by S. C. Brees

(1847).

|

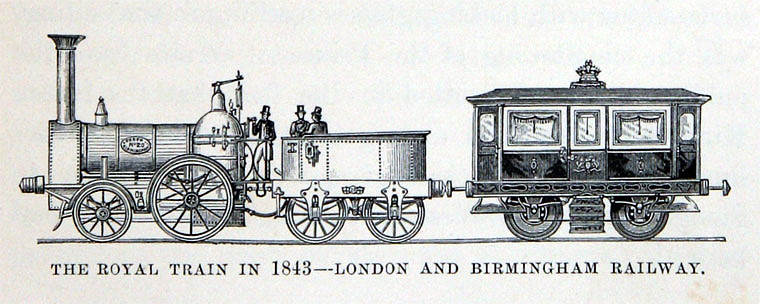

Among the notables to call at Tring Station was Queen Victoria,

together with Consort and retinue:

“The train reached Boxmoor station about one minute past ten

o’clock. To the platform of this station several persons had been

admitted in order that they might have an opportunity to seeing her

Majesty as she travelled on the railroad, but, considering the

rapidity with which the train proceeded, it is hardly possible to

conceive that their very natural curiosity could have been

adequately gratified. It was, however, an unusual sight to see a

special train of this kind at all. In the centre of it was a

magnificent carriage surmounted with a Royal crown. The spectators

knew that it contained their Sovereign and her Royal Consort; and

this was some gratification, even though they might not be able to

distinguish very clearly the illustrious individuals themselves.

Indeed, many a labourer and farmer on the railroad side left the

labour of the field to look at the Royal special train as it rushed

rapidly along.

The drizzling rain which was falling at the time had not deterred a

considerable number of persons from collecting together at Tring

station. The station is situated 31¾ miles from London, and was

reached at 14 minutes past ten o’clock; and here the train halted

for a few minutes, in order that the engine might obtain a fresh

supply of water.

Among the persons assembled at this station were the juvenile

members of the neighbouring population, boys and girls, who were

drawn up in distinct rows, and who strained their tiny voices to be

utmost in welcoming their Sovereign. Her Majesty appeared highly

pleased with this specimen of infantine loyalty and enthusiasm. A

sufficient supply of water having been obtained, the train again

started on its course, at 18 minutes past ten o’clock . . . . ”

The Illustrated London News,

16th November 1844.

When Tring had a ‘proper’ station —

Tring Station looking north,

a view that appears to date from the Edwardian era.

Today, Tring

Station comprises platform shelters (more appropriate to a bus stop), a ticket office

(in the absence of a clerk, travellers have to deal with a fiendish

ticket machine) and an

infrequent bus service to the town. By comparison, its southerly neighbour, Berkhamsted,

originally a second-class station, now offers travellers waiting room and toilet

facilities, a news stand, and a cafe (for those in need of more substantial

repast there is a fish and chip restaurant adjacent to the main

station entrance).

――――♦――――

WOLVERTON

Wolverton was an

important stopping point during the Railway’s early years, where passengers could obtain refreshment, for

corridor carriages giving access to on-board catering and toilet

facilities lay far in the future. It was also the point on the

journey where locomotives were changed and serviced: [11]

“Every engine with a train from London to Birmingham is changed

at the Wolverton station, which answers the double purpose of having

it examined, and of easing the driver and stoker. We consider even

fifty miles too great a distance to run an engine without

examination; and have seen on other lines the ill consequences

arising from the want of this necessary precaution. We should prefer

about thirty miles stages when it can be managed.”

The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland,

Francis Wishaw (1842).

However, the town’s main claim to fame

was as host to the Company’s locomotive works. It acquired

this role through its location, approximately midway between

London and Birmingham, and

retained it until the 1860s when the London and North-Western

Railway centralised locomotive construction and overhaul on Crewe.

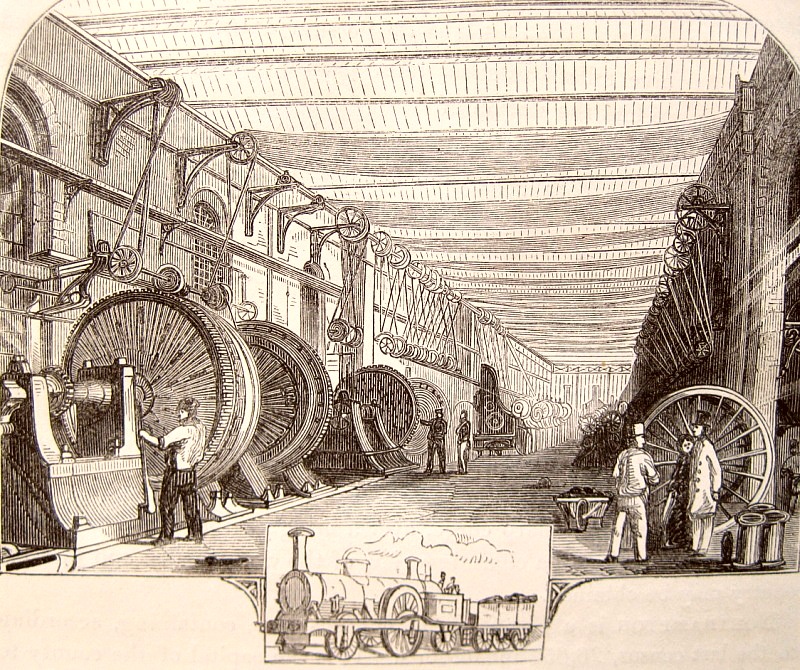

The interior of Wolverton Works, ca.

1850.

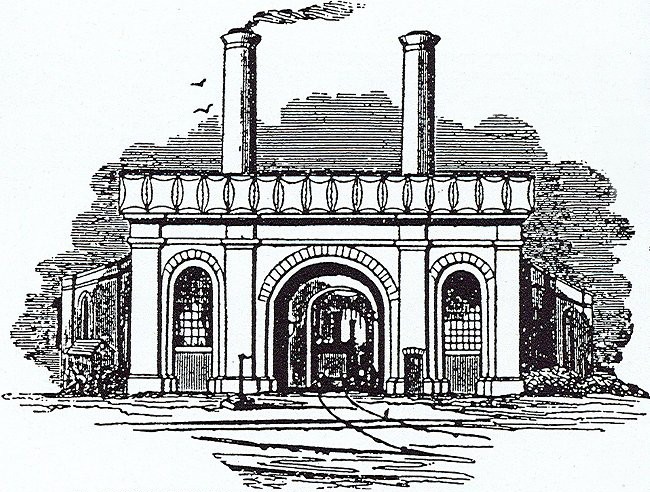

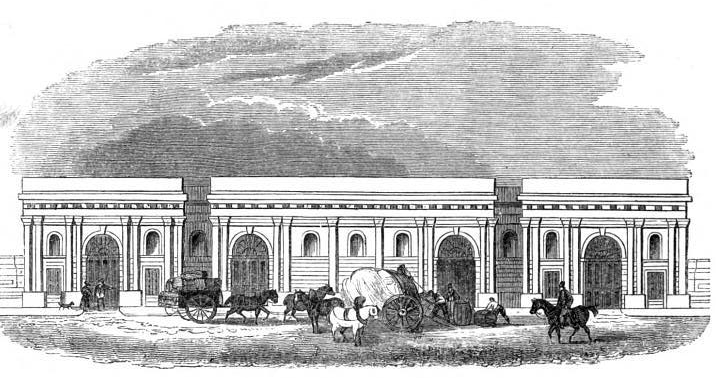

Construction of what became Wolverton Works began in 1838 with the erection of

an engine shed where maintenance could be carried out and reserve

locomotives kept in steam. Designed by

George Aitchison, the original workshop was a substantial quadrangular brick building, with

stone dressings. It could accommodate up to 36 locomotives, with

repairs being carried out in erecting shops located either side of

its entrance:

“The erecting shop is on the right of the central gateway, and

occupies half of the front part of this building. It has a line of

way down the middle, communicating with a turn-table in the

principal entrance, and also the small erecting shop, which is on

the left of this entrance. Powerful cranes are fixed in the

erecting-shops for raising and lowering the engines when required.

Contiguous to the small erecting-shop, and occupying the principal

portion of the left wing, is the repairing shop, which is entered by

the left gateway. One line runs down the middle of this shop, with

nine turn-tables, and as many lines of way at right angles to the

central line. This shop is 131 feet 6 inches long and 90 feet wide,

both in the clear, and will hold engines and tenders, or thirty-six

engines. It is lighted by twenty-four windows reaching nearly to the

roof.

In the same wing, and next to the repairing-shop, is the

tender-wrights’ shop, having the central line of way of the

repairing-shop running down its whole length, with a turn-table and

cross-line, which runs quite across the quadrangle, and intersects a

line from the principal entry to the boiler-shop the rear of the

quadrangle.

The remainder of the left wing is occupied by a room for stores on

the ground-floor, with a brass foundry and store room over; and the

iron-foundry, which extends to the back line of the buildings.”

The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland,

Francis Wishaw (1842).

Around the courtyard were the engine and tender sheds, the joiners’

shop, iron foundry, boiler yard, hooping furnaces, iron warehouse,

smithy, turning shops, offices, stores, and a steam engine for powering

the machinery and for pumping water into a large tank over the

entrance gateway.

Wolverton later added locomotive construction to its maintenance and

repair activities, although this probably post-dated the London and

Birmingham Railway; the first locomotive is believed to have been turned out ca.

1847. [12] Nevertheless, it is worth including some extracts

from the detailed account of Wolverton Works left by Samuel Sidney, who

visited several years later at a time when carriage building ― later to displace locomotive work altogether ― was

regarded, as Sidney put it,

“as experiments”:

“A few passenger carriages are occasionally built at Wolverton as

experiments. One, the invention of Mr. J. McConnel, the head of the

locomotive department, effects several important improvements. It is

a composite carriage of corrugated iron, lined with wood to prevent

unpleasant vibration, on six wheels, the centre wheels following the

leading wheels round curves by a very ingenious arrangement. This

carriage holds sixty second-class passengers and fifteen

first-class, beside a guard’s break, which will hold five more; all

in one body. The saving in weight amounts to thirty-five per cent. A

number of locomotives have lately been built from the designs of the

same eminent engineer, to meet the demands of the passenger traffic

in excursion trains for July and August, 1851.

It must be understood that although locomotives are built at

Wolverton, only a small proportion of the engines used on the line

are built by the company, and the chief importance of the factory at

Wolverton is as a repairing shop, and school for engine drivers . .

. . The history of each engine, from the day of launching, is so

kept, that, so long as it remains in use, every separate repair,

with its date and the names of the men employed on it, can be

traced. Allowing, therefore, for the disadvantage as regards economy

of a company, as compared with private individuals, the system at

Wolverton is as effective as anything that could well be imagined.”

Rides on Railways,

Samuel Sidney (1851).

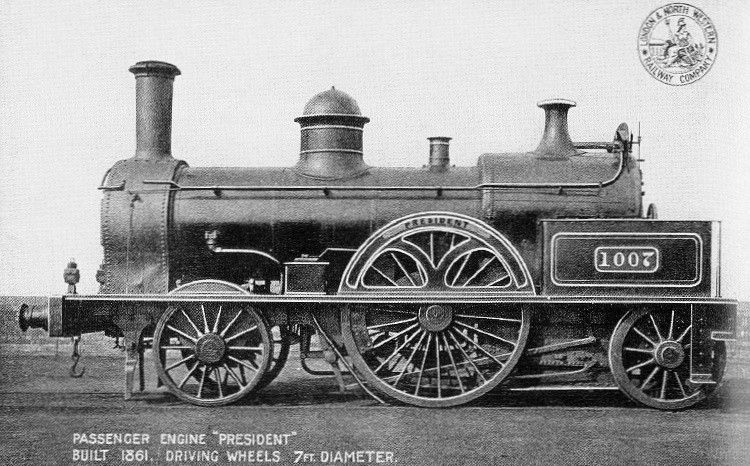

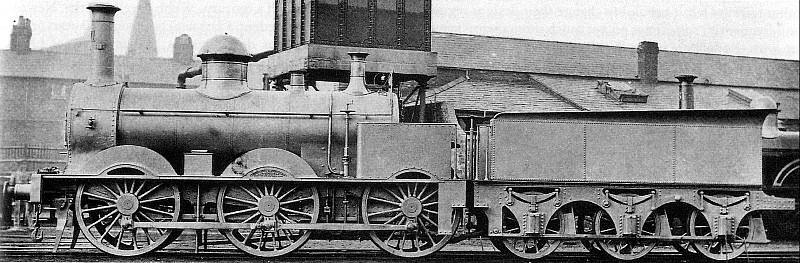

Above, a McConnel Wolverton-built

‘Bloomer’ express

locomotive, and below,

a McConnel ‘Wolverton Goods’ engine.

Sidney then goes on to describe the offices and workshops, those who

worked in them, and the various processes that were typical of the heavy

engineering that once occupied Wolverton and other railway works. The following are some of his impressions:

“At Wolverton may be seen collected together in companies, each

under command of its captains or foremen, in separate workshops,

some hundreds of the best handicraftsmen that Europe can produce,

all steadily at work, not without noise, yet without confusion . . .

. the drawing office, where the rough designs of the locomotive

engineer are worked out in detail by a staff of draughtsmen, and the

carpenters’ shop and wood-turners, where the models and cores for

castings are prepared . . . . the casting of a mass of metal of from

five to twenty tons on a dark night is a fine sight. The tap being

withdrawn the molten liquor spouts forth in an arched fiery

continuous stream, casting a red glow on the half dressed muscular

figures busy around . . . . we hasten to the steam hammer to see

scraps of tough iron, the size of a crown piece, welded into a huge

piston, or other instrument requiring the utmost strength . . . .

after seeing the operations of forging or of casting, we may take a

walk round the shops of the turners and smiths. In some Whitworth’s

beautiful self acting machines are planing or polishing or boring

holes . . . . solid masses of cast or forged metal are carved by the

keen powerful lathe tools like so much box-wood, and long shavings

of iron and steel sweep off as easily as deal shavings from a

carpenter's plane. At the long row of vices the smiths are hammering

and filing away with careful dexterity . . . . It is not mere

strength, dexterity, and obedience, upon which the locomotive

builder calculates for the success of his design, but also upon the

separate and combined intelligence of his army of mechanics.”

Rides on Railways,

Samuel Sidney (1851).

Locomotive construction at Wolverton was short-lived. Some 160

locomotives are believed to have been built at the Works, the last in 1863,

after which new construction was transferred to Crewe. Locomotive repairs

continued at Wolverton until 1872, the Works then switching entirely

to the construction and maintenance of carriages, eventually

becoming the largest carriage works in Britain.

When the railway first came to Wolverton, there was nothing there to

accommodate the large labour force that the workshops would require

and provide

the usual infrastructure of shops, school, utilities,

etc. Thus, as a matter of necessity, the Company had to build

around the Works what was to become the

country’s first railway town:

“The population entirely consists of men employed in the

Company’s service, as mechanics, guards, enginemen, stokers,

porters, labourers, their wives and children, their superintendents,

a clergyman, schoolmasters and schoolmistresses, the ladies engaged

on the refreshment establishment, and the tradesmen attracted to

Wolverton by the demand of the population. This railway colony is

well worth the attention of those who devote themselves to an

investigation of the social condition of the labouring classes. We

have here a body of mechanics of intelligence above average,

regularly employed for ten and a half hours during five days, and

for eight hours during the sixth day of the week, well paid, well

housed, with schools for their children, a reading-room and

mechanics institution at their disposal, gardens for their leisure

hours, and a church and clergyman exclusively devoted to them.”

Rides on Railways,

Samuel Sidney (1851).

“. . . . it is a little red-brick town

composed of 242 little red-brick houses — all running either this

way or that way at right angles — three or four tall red-brick

engine-chimneys, a number of very large red-brick workshops, six red

houses for officers — one red beer-shop, two red public-houses, and,

we are glad to add, a substantial red school-room and a neat stone

church, the whole lately built by order of a Railway Board, at a

railway station, by a railway contractor, for railway men, railway

women, and railway children; in short, the round cast-iron plate

over the door of every house, bearing the letters L.N.W.R.,

is the generic symbol of the town . . . . All, however, whether

whole or mutilated, look for support to ‘the Company,’ and not only

their services and their thoughts but their parts of speech are more

or less devoted to it: —for instance, the pronoun ‘she’ almost

invariably alludes to some locomotive engine; ‘He’ to ‘the

chairman,’ ‘it’ to the London Board. At Wolverton the progress of

time itself is marked by the hissing of the various arrival and

departure trains. The driver’s wife, with a sleeping infant at her

side, lies watchful in her bed until she has blessed the passing

whistle of ‘the down mail.’ With equal anxiety her daughter, long

before daylight, listens for the rumbling of ‘the 3½ A.M. goods up,’

on the tender of which lives the ruddy but smutty-faced young

fireman to whom she is engaged. The blacksmith as he plies at his

anvil, the turner as he works at his lathe, as well as their

children at school, listen with pleasure to certain well-known

sounds on the rails which tell them of approaching rest.“

Stokers and Pokers, Sir Francis Bond Head

(1849).

Not only did the Company house and educate its workforce, it extended its

paternalism to their spiritual welfare, the directors making a contribution

of £1,000 from shareholder funds towards

a church “for the use of the Company’s

servants”:

“. . . . So extensive is the establishment in this place, that a considerable village, composed of the men in

the company's service and their families, has sprung up where

formerly there was not a single habitation. The company has erected

houses for the men, and allotted gardens to them, and some time

since voted a grant of money for the erection of schools for the

infant and adult population, but there was still no means of

supplying them with religious instruction. The trustees of the

Radcliffe Estate, through which this part of the railway is made,

thereupon offered to build and endow a church, and to provide a fund

for future repairs, if the railway company would contribute £1,000

towards this desirable object. Accordingly, at the last meeting a

proposal that such a contribution be made was brought forward by a

gentleman named Jones, who, it is worthy of notice, is himself a

Dissenter, and was carried with but one dissentient voice.”

Company General Meeting, reported in The Morning Post,

13th February 1841.

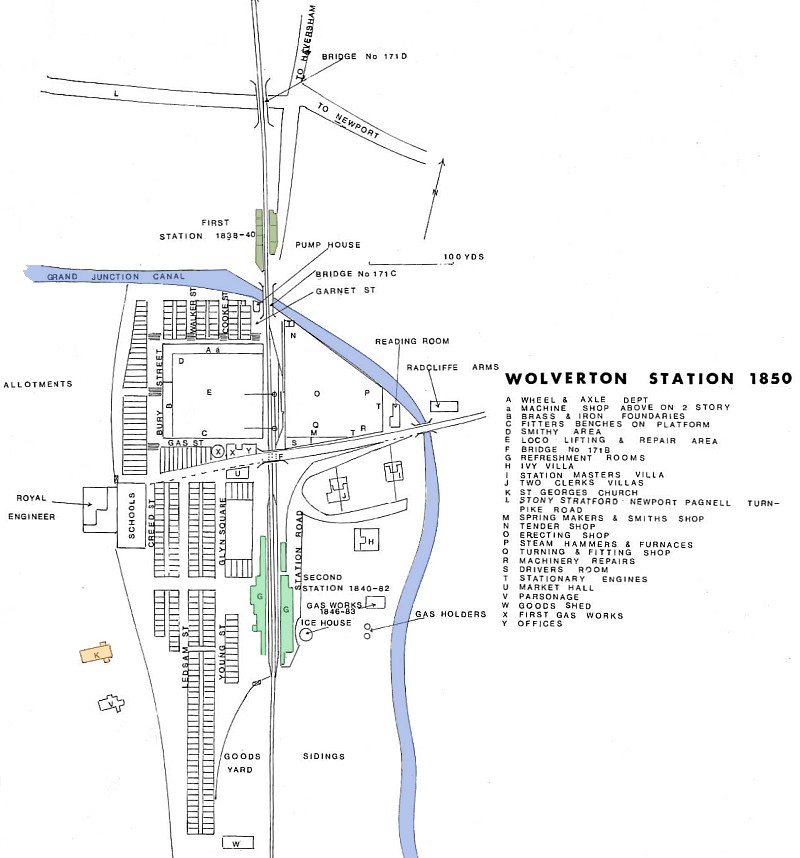

Wolverton in 1850 - courtesy Milton

Keynes Museum

Even in an age predating multiculturalism, questions concerning

religious belief at times awakened warm debate and censure ― as indeed

reference in the preceding extract to “a Dissenter” might

suggest. It is therefore unsurprising that the Company’s proposal to contribute towards an Anglican

church should arouse the ire of its Quaker shareholders, who:

“. . . . contended that, however desirous they might be of

promoting the moral and religious instruction of the company’s

servants, it was not right that they should be compelled to the

support of the Church of England, from which they conscientiously

differed. They proposed, therefore, that the resolution of the

previous meeting be rescinded, and that the amount required should

be raised by voluntary subscription.”

General Meeting, reported in The Morning Post,

13th February 1841.

After

“a very long discussion” a compromise was reached; the objectors’ proportion of the £1,000 ―

about 4½d a share ― was refunded to them, and the

“company’s servants”

got their church, although whether they really wanted it is

unrecorded. Opened in 1843 for the special, but not exclusive use of

railway workers, Saint George’s Church claims the distinction of

being the first church in the world to be built by a railway

company. |

|

|

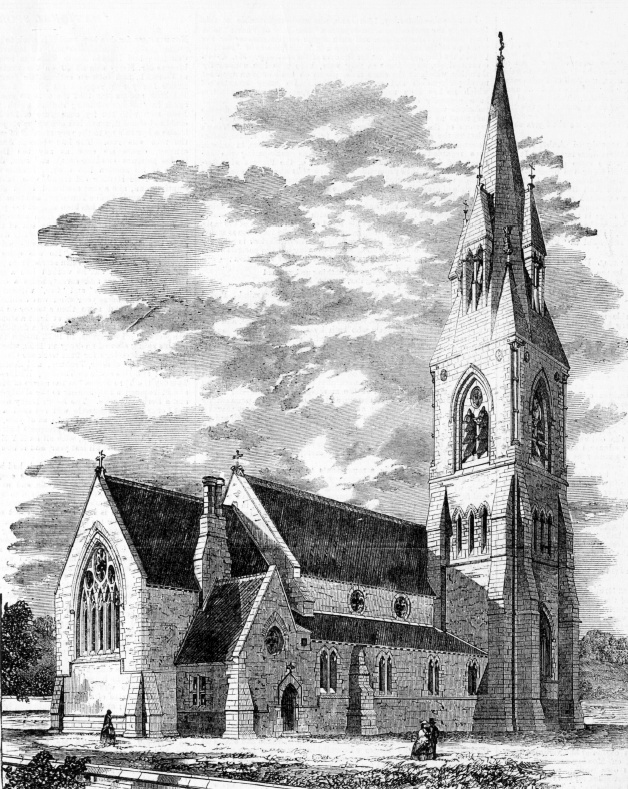

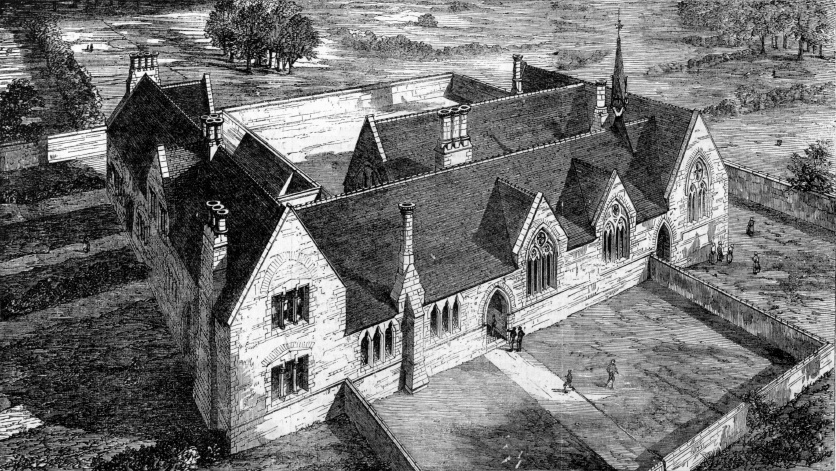

The new church and school about

to be erected at Stantonbury, near Wolverton.

Illustrated

London News, 19th June 1858.

The church was to

accommodate between seven and eight hundred people, the

school one hundred each of boys, girls and infants, with

residential accommodation for the teachers. |

|

|

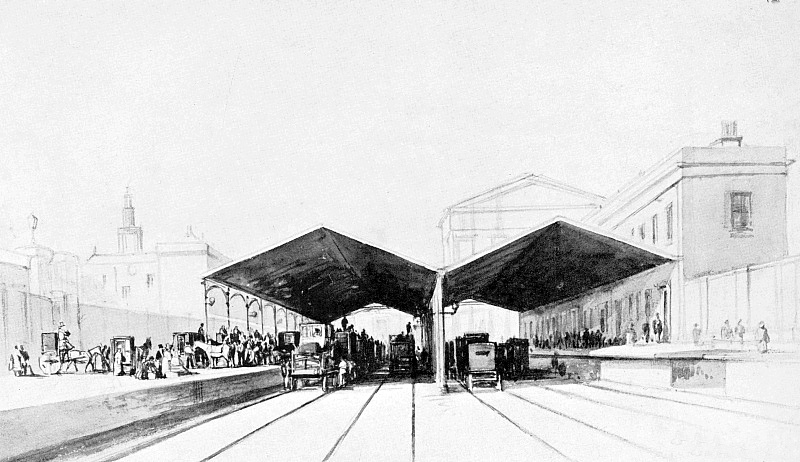

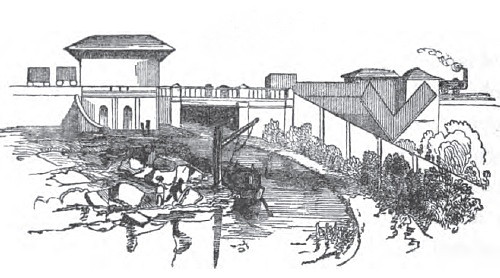

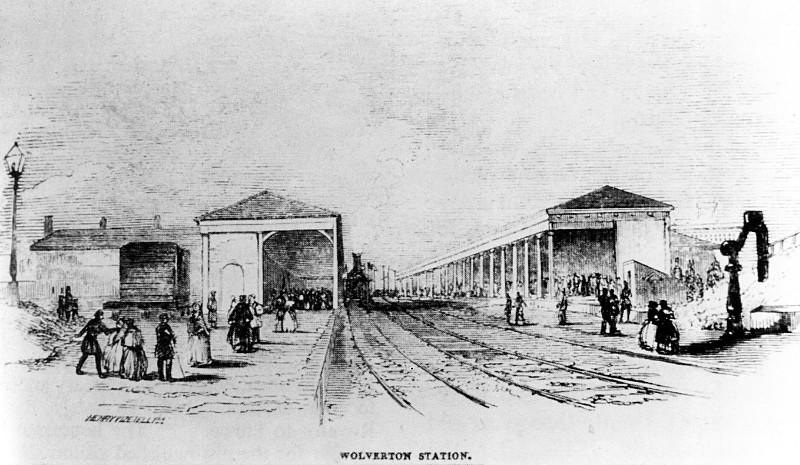

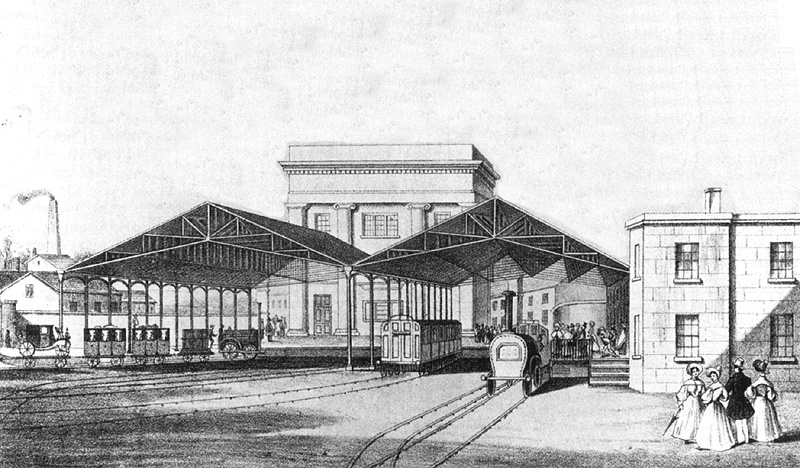

The

first Wolverton Station with the Grand

Junction Canal in the foreground. |

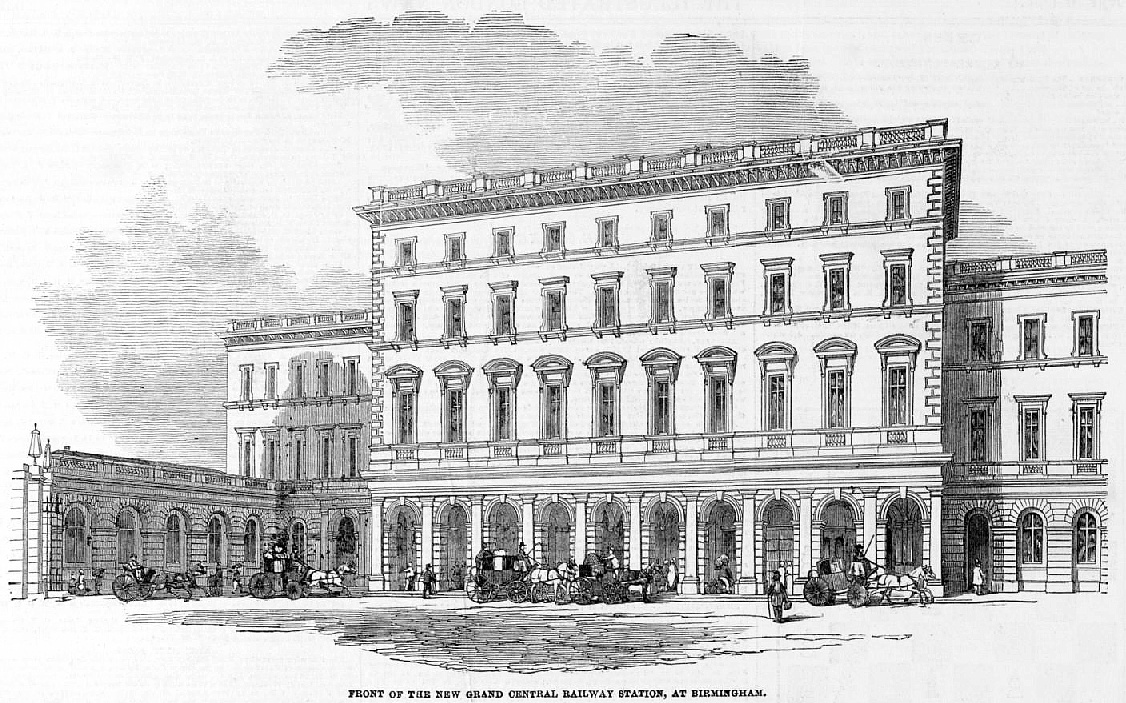

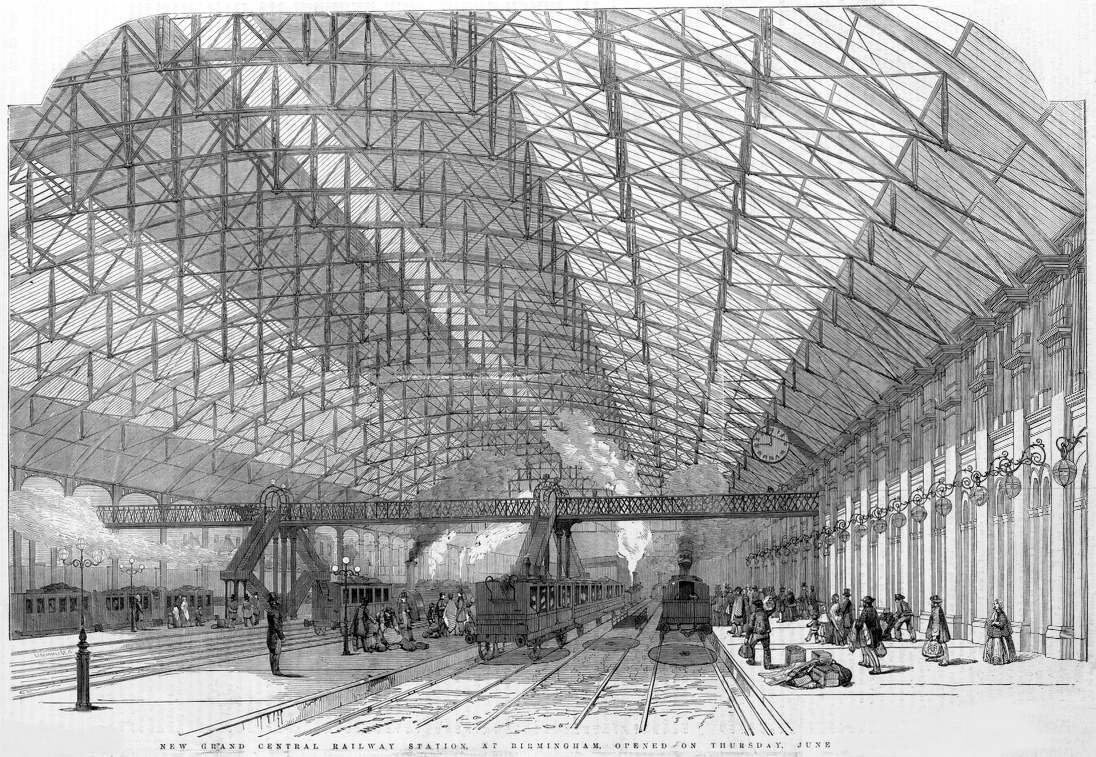

Turning next to Wolverton Station, the first

building to be built was located

to the north of the Grand Junction Canal (see plan). Opened in 1838, the volume

of passengers using it soon outgrew its capacity

and in 1840 a new and larger station was opened. Located slightly to

the south of the first station, it

offered travellers waiting rooms, toilet facilities, a restaurant

and refreshment rooms. The colonnaded platform canopies shown below are

somewhat reminiscent of Hardwick’s colonnaded frontage to the

booking office at Euston. |

The second Wolverton station. |

Many sentiments ― mostly uncomplimentary ― have been expressed about

railway refreshment rooms down the years, particularly about those at Wolverton.

Trains once paused there to change locomotives, which created a ten-minute interval during which

there was a stampede to the

refreshment rooms, for the journey in either direction was long (2½

hours or more) and uncomfortable. Among other things,

travellers complained about the difficulty in getting served.

However, contrary to the general flow of opinion, Sir Francis Bond

Head in his account of the London and North Western Railway

(published in 1849) devotes an entire chapter in praise of

Wolverton’s refreshment facilities. His views, together with

those of others on the subject of railway catering, are reproduced

in the Addenda ― they provide

amusing reading.

|

Head Barmaid.

“These

tarts are quite stale, Miss Hunt ― been on the counter

for a fortnight! Would you mind taking then into the

second-class refreshment room?”

(Punch). |

In other areas Wolverton Station also appears to have fallen short of the ideal,

at least in the opinion of one member of the travelling public. To

those of a nervous disposition the roar of escaping steam warranted

complaint, as did the limited stopping time in an age when the gentry

and their ladies travelled with their carriages, sometimes in them: [13]

“Frequently (he says) on the stopping of a train at a station,

the engines are stopped close to the windows of the opposite train,

and during this time these boilers are allowed to play off their

steam, which causes so frightful a noise as easily to bring on

illness with a nervous person. These engines might easily be sent

200 or 300 yards until the trains are ready, and not to terrify the

passengers for five minutes and more, to so great an extent as I

have been witness to frequently. The second point, although a minor

one, is the great want of attention on the part of some one when the

train arrives, and stops for ten minutes at Wolverton, where ladies

have wished to alight from their carriages which are of necessity

perched upon a truck; but no one can be found with a ladder until it

is generally time to start off again, when on hearing the bell

ringing and the steam puffing off, the poor ladies are seen running

about in all directions almost frightened out of their lives at

being left behind.”

Letter to the Editor of the Railway Times,

31st August 1839.

As the century progressed, Bletchley’s importance grew, helped by

the opening of the now defunct Oxford to Cambridge rail link. And as locomotives became faster and capable of

longer journeys without servicing, express trains ceased to call at

Wolverton and its importance diminished. The refreshment rooms are

long gone and today Wolverton is a minor

station on the line. At the time of writing (2013), much of

Wolverton Works lies derelict.

――――♦――――

FORGOTTEN STATIONS AND THE NORTHAMPTON LOOP

In former days there were several stations between Wolverton, Rugby

and Coventry,

all part of the line’s original complement, which have since

disappeared. All were victims of the mass

station closures

of the 1950s and 60s.

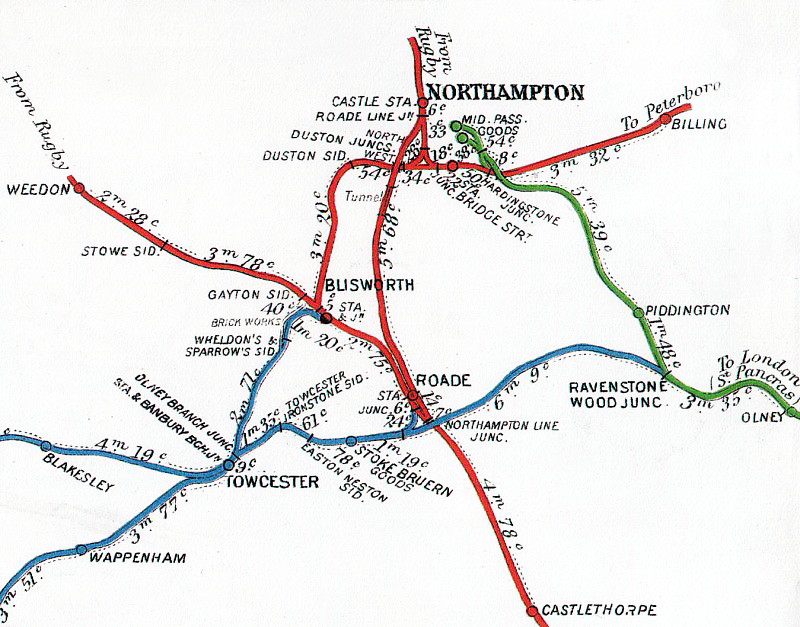

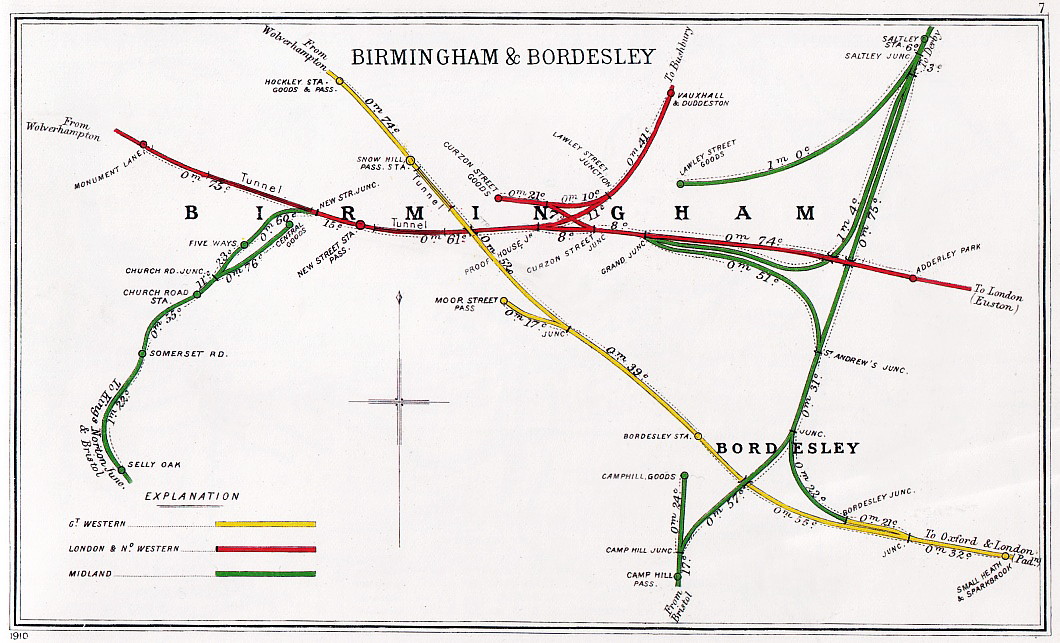

1911 Railway Clearing House map of

railways in the vicinity of Roade.

The most northerly of the group was Brandon, the only station

between Coventry and Rugby. It was replaced in 1879 by a new

station nearby named

‘Brandon and Wolston’, but the station never generated

much income and was closed in 1960. The most southerly closure was Castlethorpe, a late

addition to the line that opened in 1882, and closed in 1964. Then came Roade

(closed 1964), Blisworth (closed 1960), Weedon (closed 1958) and

Crick (renamed Welton in 1881; closed to passengers in 1958 and

entirely in 1964).

Roade was originally the jumping off point for Northampton, a town that the Railway

bypassed:

“As the

line neared completion the Duke’s [of Grafton]

officials, the railway company and other interested parties

discussed whether a station to serve Northampton should be built at

Roade, where the line crossed the road from Northampton to London,

or Blisworth, where it crossed the Northampton-Towcester turnpike

not far from Watling Street and also ran close to the Grand Junction

Canal. In both cases, the site would be acquired from the Grafton

estate. At first, Blisworth was preferred as ‘the great depot for

the county’, although first-class stations were also provided at Roade and Weedon. For a few years Roade, where the station was built

in the cutting immediately south of the bridge carrying the main

London road over the line, prospered as the most convenient of the

three for Northampton, but after the opening of the line from

Blisworth to Peterborough through Northampton in 1845 it was reduced

to a third-class station. By 1862 the refreshment room had been

removed and there were only seven stopping trains a day. In 1875 the

London & North Western Railway obtained powers to quadruple the main

line between Bletchley and Roade and build a loop which left the

main line about a mile north of Roade station to serve Northampton. Once again land was acquired from the Grafton estate and in 1882 Roade station was rebuilt on a larger scale with three platforms and

four running faces.”

From: ‘Roade’, A History of the

County of Northampton: Volume 5: pp. 345-374.

Why the Railway bypassed Northampton remains a vexed question. Take,

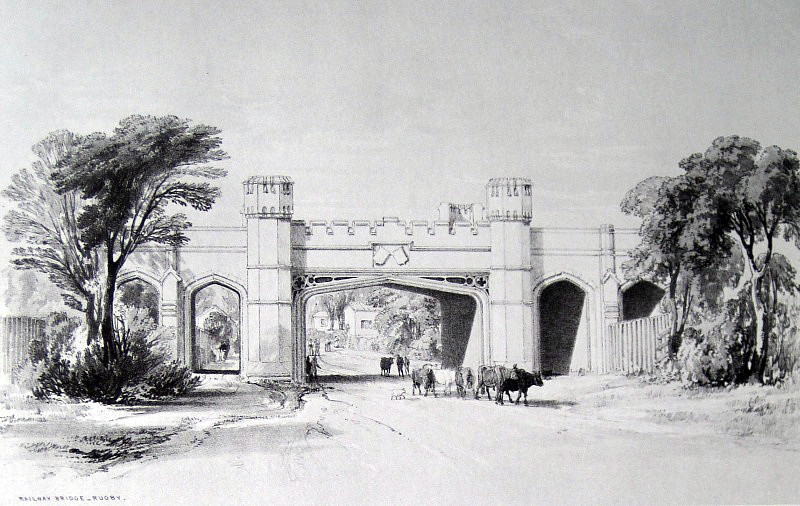

for example, Ernest Carter, writing about the Blisworth to