|

The authors’ text may be used for any scholarly

or

educational purpose without prior permission

so long as this website is cited.

CONTENTS

――――♦――――

|

|

THE

RAILWAY COMES TO

TRING:

The London & Birmingham Railway 1835-1846

FOREWORD

“. . . . the inhabitants are making

every exertion to accommodate the public that every day throng this

beautiful neighbourhood, which, from the variety of hill and dale,

wood and water, combined with the extensive views it commands, is

likely to become a place of importance.”

The opening of the

railway from Euston to Tring, The Bucks Gazette, October 1837.

We doubt that many, if indeed any of the travellers

that pass through Tring Station spare a thought for its history. Why should they? With the possible exception of

the adjacent

Royal Hotel the station offers nothing that is likely

to arouse historical curiosity. Austere functionality now pervades

the scene. As for the railway today, it bears little resemblance

to that constructed by Robert Stephenson and his team of civil

engineers with their contractors and gangs of navvies.

The following account makes no claim to be a detailed

treatise on the history of the London and Birmingham Railway.*

It aims instead to provide readers interested in the history of

the town with a résumé of events leading up to the Railway’s

arrival at Tring in October 1837, to the construction of the

town’s station, and some points of general interest concerning travel

in the locality in that age. Our narrative is in the form of a compilation of

notes and historical extracts taken from the sources listed at the

end of this booklet. We would be interested to hear from

anyone who can add further information on the history of the

London and Birmingham Railway in the locality.

Our thanks go to Michael Bass, Chris Reynolds, John Savage

and Russell Burridge, and to staff at the Buckinghamshire Centre for Local Studies and the Hertfordshire Record Office for their

kind assistance.

Ian Petticrew and Wendy Austin,

November 2013.

* For a

more detailed account of the Railway’s history see . . . .

The Train Now Departing.

――――♦――――

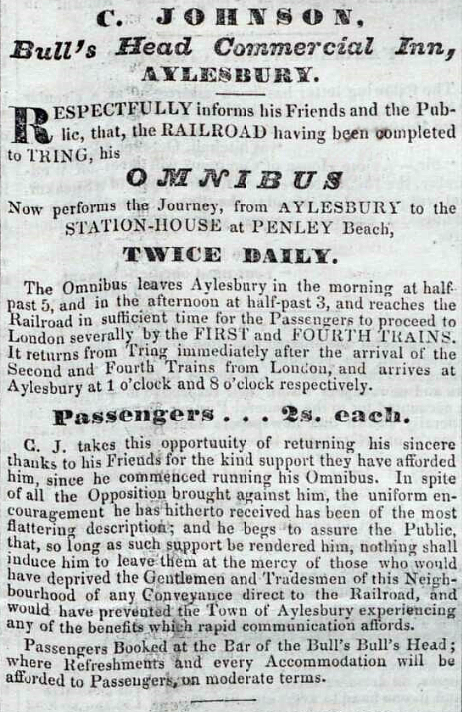

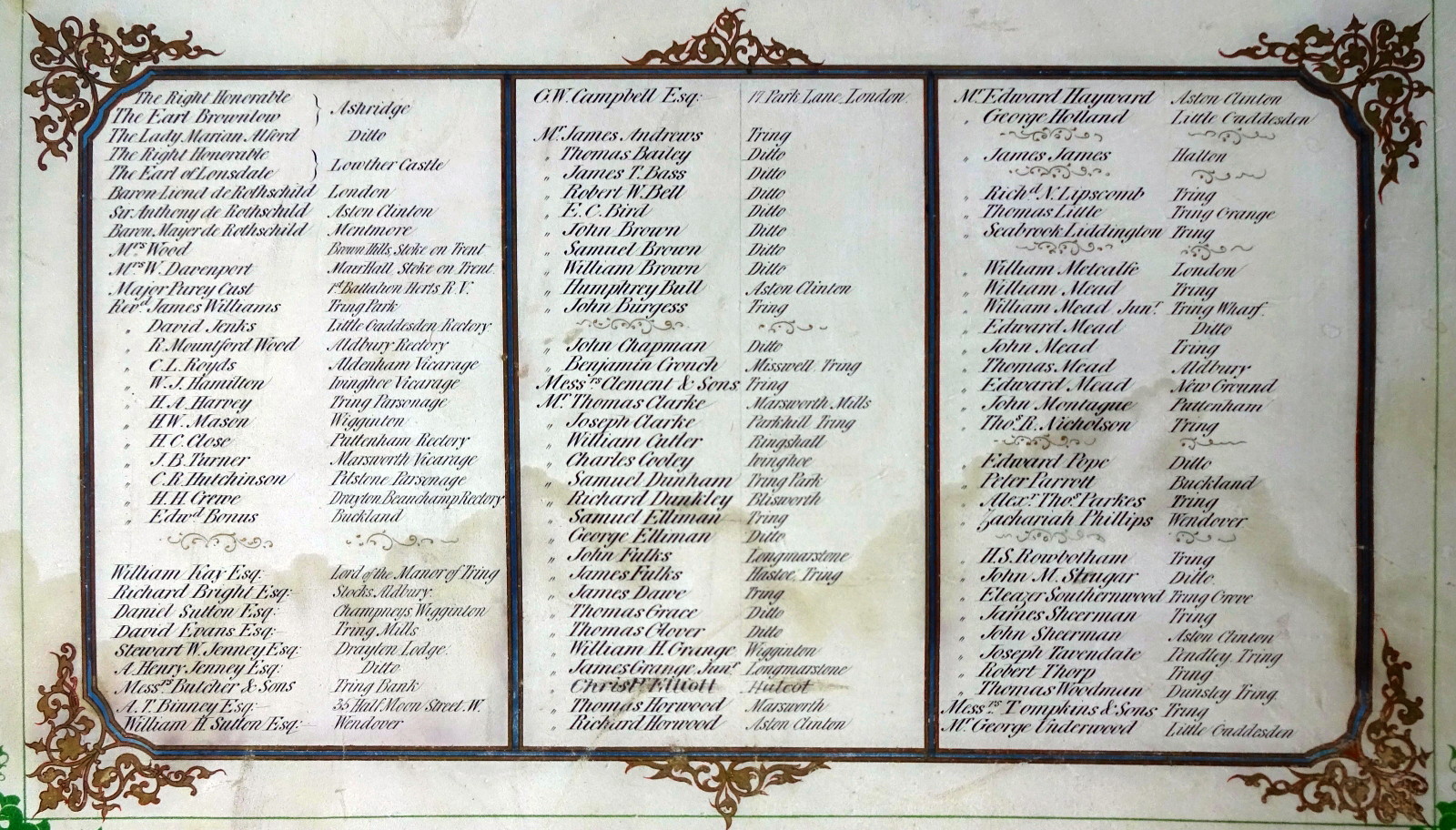

THE RAILWAY ACT IS PASSED

“The Bill for the new London & Birmingham

railroad has at last passed through both Houses of Parliament. For

nearly three years since the original scheme was first drawn up, the

struggle has gone on. The greatest opposition has come from the

large landowners of Hertfordshire, viz. Lord Essex, Lord Clarendon,

Lady Bridgewater, Sir Astley Cooper and others.

In deference to the wishes of these

landowners, big alterations were made in the original route. The

terminus is changed from King’s Cross to Euston, and at Watford the

line is altered to avoid the parks of Lords Essex and Lord

Clarendon, and this will involve the construction of a very long

tunnel at Watford. The original plan was to carry the line along the

Great Gaddesden valley, but this was abandoned, owing to the great

opposition from the House of Ashridge. Those who stood in the way of

progress were eventually won over by giving them tremendous prices

for their land, in some cases three or four times its value. The

total cost of carrying the Bill through Parliament amounted to

nearly £73,000. The difficulties with the various landowners

appeared to be insuperable, but they appear to be over now, and in a

few years the railway will be an accomplished fact.”

Tring’s Vestry

Minutes, 1833.

|

|

|

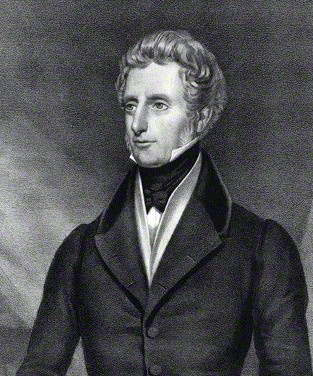

Railway opponent, John Cust,

1st Earl Brownlow (1779-1853). |

The London and Birmingham Railway Company

required the authority of a ‘private’ Act of Parliament before

construction of the line

could begin. Among the privileges that

such an Act conferred on the Company was that of compulsory purchase,

the ability to buy land without the owner’s consent, but at a fair valuation. However,

influential landowners who did not wish to sell could oppose the

Company’s railway Bill as it passed through Parliament, and they

did.

It is not easy to ascertain what the Company thought was a fair

price for land in Hertfordshire. They estimated £183 per acre

for land between Kilburn and Tring, and £71 per acre between Tring

and Wolverton. However, the surveyors generally reckoned a

reasonable price for agricultural land at that time to be £70 per

acre. The Bridgewater Trustees received £76 per acre for land

in Tring, Marsworth and Cheddington, and their tenant, Peter

Parrott, £3.60 per acre, giving a total of nearly £80 per acre; and

for 43 acres of land in Northchurch, Tring, Cheddington, Marsworth

and Horton, they received £130 per acre. They also received

the expenses they incurred in opposing the 1832 London and

Birmingham Railway Bill, a sum amounting to £2,178. Mr.

William Smart of Aldbury was paid £140 an acre and Captain Harcourt

of Tring £120. Members of Tring Vestry appear to have

considered the amounts awarded to these objectors to the railway

scheme to be ‘tremendous’, but several other landowners did accept

the railway company’s original valuation.

|

|

|

Railway

opponent, Sir Astley Cooper Bt. (1768-1841). |

The Company first applied to Parliament for a

private Act in 1832. Their Bill passed through the House of

Commons, but was vetoed in the Lords by an influential landowner,

Lord Brownlow of Ashridge, who, speaking on behalf of a group of

railway objectors, stated:

|

“That the case for the promoting of the Bill

having been concluded, it does not appear to the committee that they

have made out such a case as would warrant the forcing of the

proposed railway through the land and property of so great a

proportion of dissentient landowners and proprietors.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Roscoe and Lecount (1839).

|

The Bill’s failure resulted in the Company wasting Parliamentary and

other expenses amounting to £72,869, a huge sum for the time, and it

caused outrage. In order to placate influential landowners who

remained unwilling to sell – and thus avoid further opposition when

their railway Bill again came before Parliament – the Company was

obliged to pay them considerably above market rates. But when

a further application was made to Parliament in the following year –

a significant number of objectors’ palms having been greased in this

way during the intervening period – the railway Bill went through

almost unopposed and passed into law on the 6th May, 1833.

Work could then commence, although the volume of detailed planning,

the preparation of drawings and specifications, and the letting of

construction contracts by competitive tender was a lengthy task, and

it was to be a further 12 months before the first sod was turned.

By the end of 1838, when the line eventually opened, the Company had

paid out £537,596 for land against their initial estimate of

£250,000.

――――♦――――

ROBERT

STEPHENSON

CIVIL ENGINEER

(1803-1859)

The great railway cutting at Tring is just one of a number of

notable civil engineering features along the course of the London

and Birmingham Railway. Completed almost 180 years ago, it is almost

60 feet deep in places and, at 2½-miles, is the longest cutting on

the line. It took 500 men three years to excavate using picks,

shovels and wheelbarrows, and helped along by horse power. In that time they cut through 1,400,000

cubic yards of chalk, which they then had to lift to the surface for

disposal. This feat of pre-Victorian civil engineering was planned

and carried out under the supervision of Robert Stephenson.

|

|

|

|

Robert and George Stephenson. |

|

Robert Stephenson was born near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the only son of

George and his wife Fanny. His mother died when he was two years old

and Robert was then cared for by his father’s sister and

housekeeper. George Stephenson (1781-1848), a self-made man of scant

formal education, was a tough and ambitious father who was

determined that his son followed in his footsteps. Robert received a

good education including a short period spent at Edinburgh

University, to which was added intensive engineering training. He

soon became his father’s assistant, eventually working with him on

projects such as the construction of the Stockton and Darlington

Railway. Following a 3-year mining venture in South America, Robert

returned to England in time to oversee construction of the Rocket

― the locomotive that in 1829 won the famous Rainhill Trials ― in

the process creating the basic locomotive design template for the

remainder of the steam traction era.

In 1830, the London and Birmingham Railway Company was formed and

the civil engineering firm of George Stephenson & Son was appointed

to make surveys, select the best route and carry the railway through

the arduous process of obtaining a private Act of Parliament. Two outline

surveys had already been made; one, via Quainton and Banbury, by

John Rennie Jnr., the other, via Rugby and Coventry, by Francis

Giles. Following a detailed examination of the ground, and with some

alterations, the Stephensons recommended the route via Rugby and

Coventry. This being approved by the Board, from then on George disappeared

from the scene leaving Robert

to take over the detailed surveying and planning of the line. Here, he had to tread

a delicate path to avoid upsetting more of the landed gentry than

necessary, for this was an age in which they held very considerable

influence and the line would inevitably cross some of their estates.

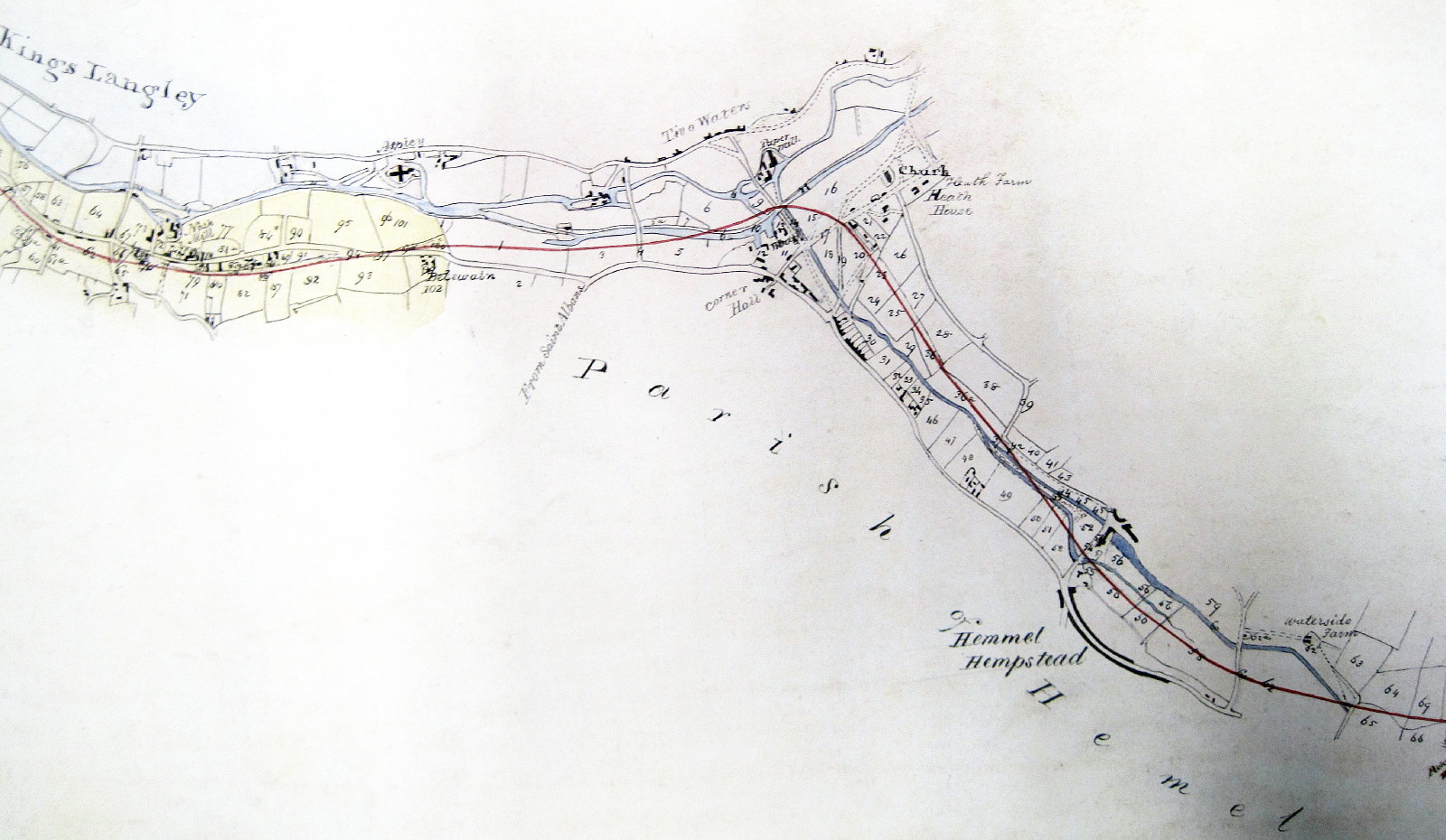

Stephenson’s preferred choice of route for taking the railway over

the Chiltern Hills was along the Gade Valley from Two Waters,

through Hemel Hempstead, Gaddesden and Dagnal and then on to

Leighton Buzzard. This route crossed land owned by, among others,

the influential Earl of Essex and the trustees of the Bridgewater

estate, and it aroused such opposition that the Company was forced

to find an alternative. Stephenson’s second choice was to follow the

Bulbourne Valley through Berkhamsted and to the east of Tring. However, taking the railway through the Tring Gap required the

construction of a long and deep cutting to enable the railway’s

maximum gradient to fall within Stephenson’s target of 1:330 (16

feet to the mile). |

|

Part of the plan of

Stephenson’s abandoned route in Dacorum. At Two

Waters, the line

was to have turned into the Gade Valley, passing

through Hemel Hempstead and

crossing the ridge of the Chilterns through the

Dagnal Gap. |

Having obtained their Act of Parliament, the Company appointed

Robert Stephenson Engineer-in-Chief at an annual salary of £1,500

(later increased to £2,000 to equal that paid to Brunel, then

building the Great Western Railway). Stephenson’s contract required

him to devote virtually all his time to this exceptionally large and

complex undertaking, during which, it is said, he walked the entire

route 20 times. All manner of civil engineering difficulties had to

be overcome requiring the construction of cuttings, embankments,

viaducts, bridges (including difficult masonry ‘skew arch bridges’

that cross roads and waterways at an angle), cuttings (including

two substantial cuttings at Tring and Blisworth) and tunnels, of

which that at Kilsby in Northamptonshire is generally considered to

be one of the most ambitious civil engineering feats of its age.

Robert Stephenson’s gifts of leadership and organisation were

needed during the difficult task of selecting and managing his

project team, which eventually numbered sixty. He was supported by

five assistant engineers, under whom were a team of sub-assistants,

draftsmen and pupils (in effect, apprentices). The young men

referred to themselves as ‘Stephensonites’ and remained loyal to

their chief in later controversies and triumphs. A contemporary pen

portrait tells us that Stephenson had “an energetic countenance,

frank bearing, and falcon-like glance . . . . he was kind and

considerate to his subordinates, but was not without occasional

outbursts of fierce northern passion.” But the intense pressure

of the work took its toll, for the account continues “during the

construction of the line, his anxiety was so great as to lead him to

frequent recourse to the fatal aid of calomel”, a toxic

mercury-based chemical prescribed by English doctors at the time as

a universal remedy.

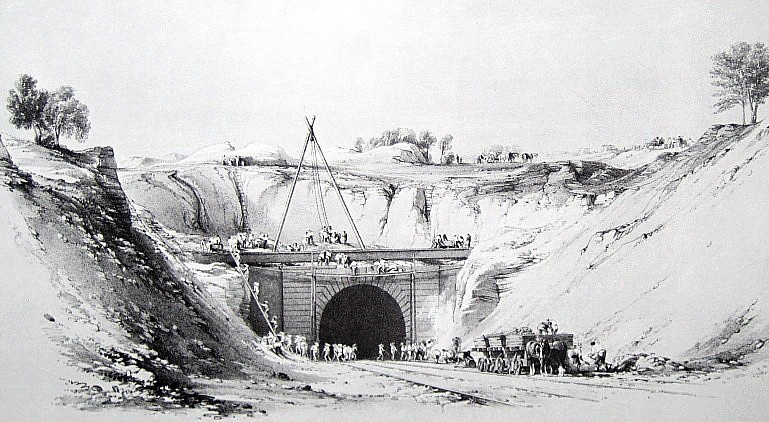

Watford Tunnel under construction, June 1837,

by John Cooke Bourne.

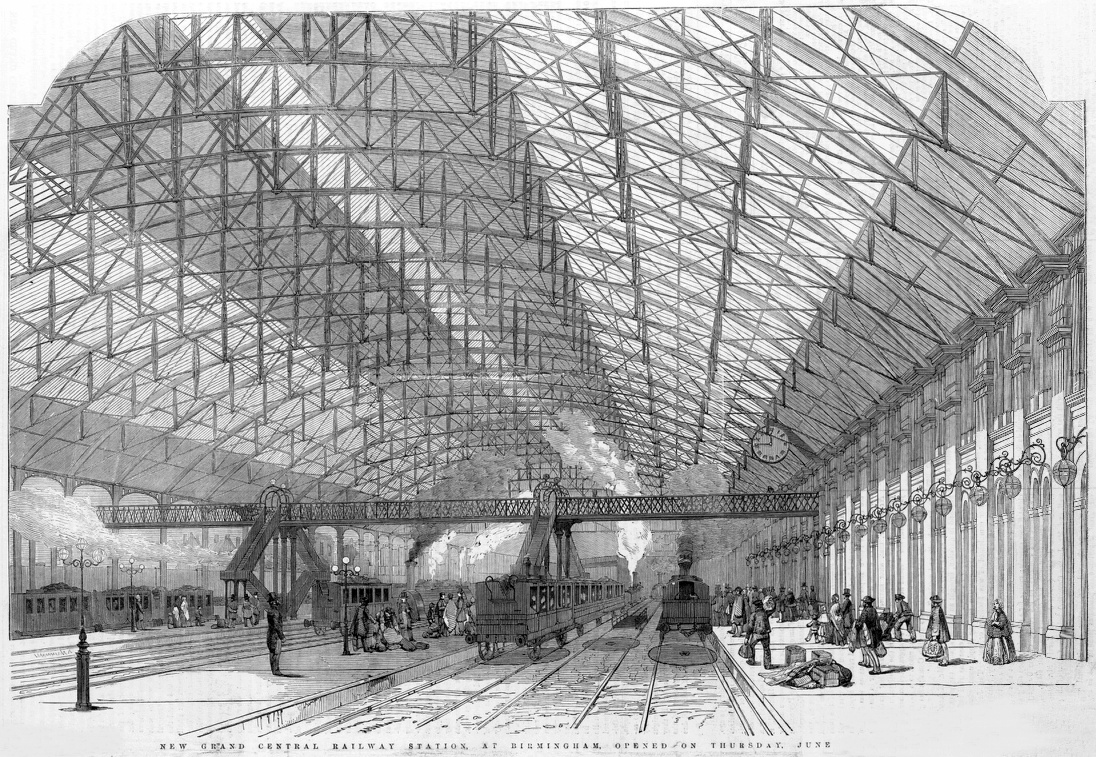

The railway opened in stages as work progressed; to Boxmoor, on the

20th July 1837; to Tring, on the 16th October; to Denbigh Hall, and

to Rugby from the opposite direction, on the 9th April (the 38-mile

gap being bridged by a shuttle coach service); and

the line was opened throughout on the 17th September, 1838. In the

meantime the Grand Junction Railway ― constructed, principally, by

another famous civil engineer, Joseph Locke ― had reached Birmingham from

Warrington, both railways sharing the same terminus at Curzon

Street. There was now a continuous rail link between London and the

North-West of England.

Following the line’s completion, Stephenson’s career went from

strength to strength. Among his engineering triumphs was the High

Level Bridge across the Tyne (1849), the great Britannia Bridge

across the Menai Straits (1850), and the 6,588-feet long Victoria

Bridge over the St. Lawrence River at Montreal in Canada (1859). But

the Dee Bridge on the Chester to Holyhead Railway was to cast a dark

shadow over his later achievements, for on the 24th May, 1847, it

collapsed while a train was crossing, causing in five deaths and

nine serious injuries.

|

|

|

Entrance

to Watford Tunnel.

An L&NWR postcard. |

After 1840, Stephenson was consulted increasingly on overseas

railways schemes and began to travel a good deal. He also became

engaged in public activities and in the development of his own

business concerns, particularly the locomotive manufacturing firm of

Robert Stephenson and Company based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne. In

1847, he broadened his interests further when he entered Parliament as the member for Whitby, a seat he held

until his death. In politics, Stephenson was a Tory of the Right, hostile to

free trade and anxious to avoid change in almost any form, which

seems paradoxical in a man who was responsible for a great deal of

economic and social upheaval.

In 1842, Stephenson was again concerned with matters at Tring when

he was consulted by the London, Westminster & Metropolitan Water

Company on the feasibility of providing London with water from

sources in the Chiltern Hills. His reports were lengthy and, as to

be expected, well-reasoned. He stated “I am well acquainted with

the chalk district between Watford and Tring, and it having devolved

upon me, in the course of my connexion with the London & Birmingham

Railway, to sink a great number of wells, my attention has been

particularly called to the extraordinary quantity of water existing

in the chalk . . . .” Perhaps fortunately for our locality,

the water company did not pursue the idea of using the Bulbourne

Valley to supply London.

In later life, Stephenson acquired all the outward marks of

recognition of a distinguished career. He declined a knighthood, as

had his father, but was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and

served as President of both the professional bodies with which he

was associated, the Institutions of Mechanical and of Civil

Engineers. With his life’s work completed and the premature death of

his wife, he became melancholy, sometimes peevish, and he often

returned to visit his childhood haunts in the Northeast. His

constitution, never robust, finally gave way, and Stephenson died on

the 12th October 1859, aged 55 (Brunel had died a few weeks

previously, aged 53). There was never any doubt about Stephenson’s

burial place and 3,000 people packed Westminster Abbey for his

funeral. The driver of the first engine used on the London and

Birmingham line wrote to ask for a ticket – it is pleasant to record

that he received one.

|

|

|

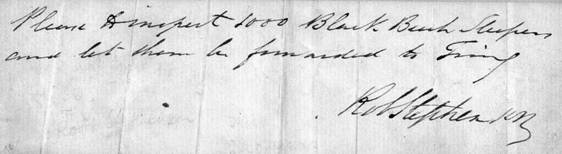

“Please to inspect 1000 Black

Beech Sleepers and let then be forwarded to

Tring”

R.

Stephenson. |

Robert Stephenson built the London and Birmingham Railway in

accordance with his father’s strict engineering principles as

evidenced by the line’s gentle curves and gradients, both of which

are conducive to high-speed running. All those who travel through

Euston Station and who walk out onto its forecourt can see a fine

bronze statue of Robert Stephenson (below) – and those few

travellers who do not hurry past with heads down might pause for a

moment or two before it to pay their respects to his memory.

Robert Stephenson, FRS, Civil Engineer:

Statue (1871) by Carlo Marachetti, Euston

Station.

――――♦――――

|

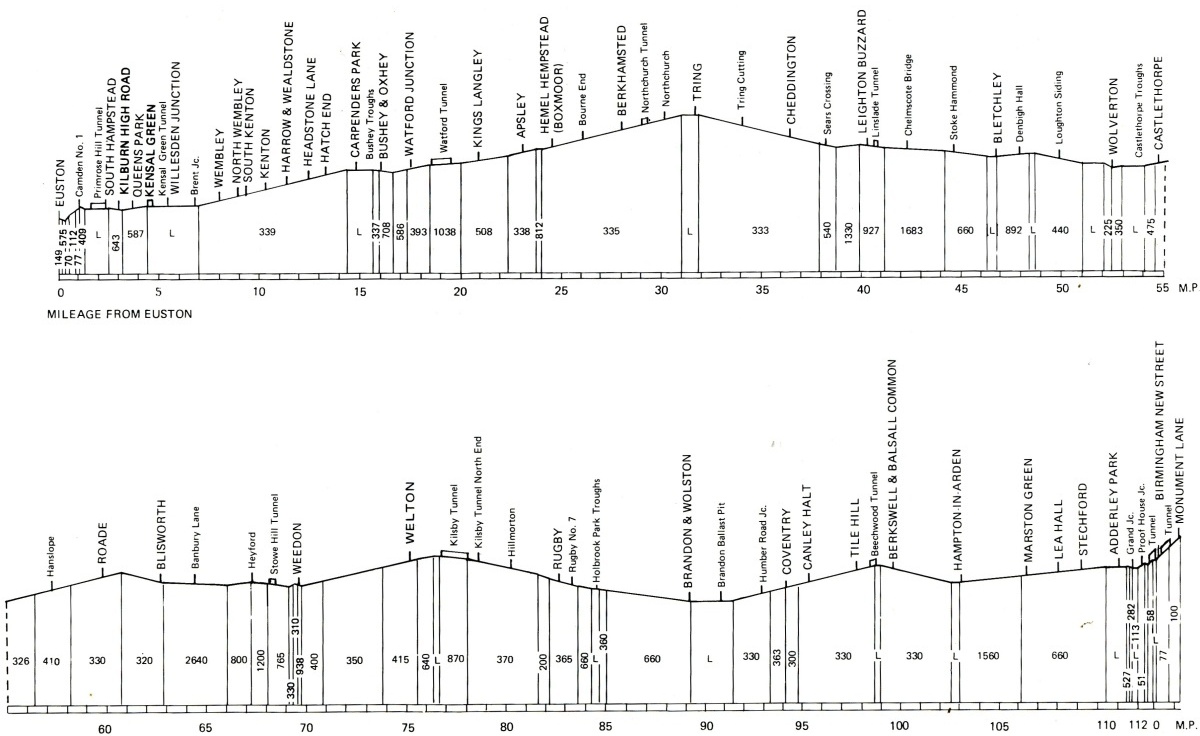

Euston to

Birmingham gradient profile.

At Birmingham, the line originally terminated at Curzon

Street, about three quarters of a mile north-east of New Street Station.

|

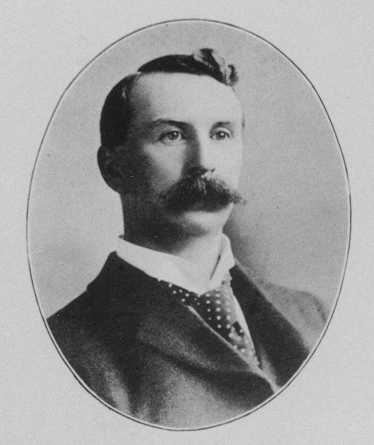

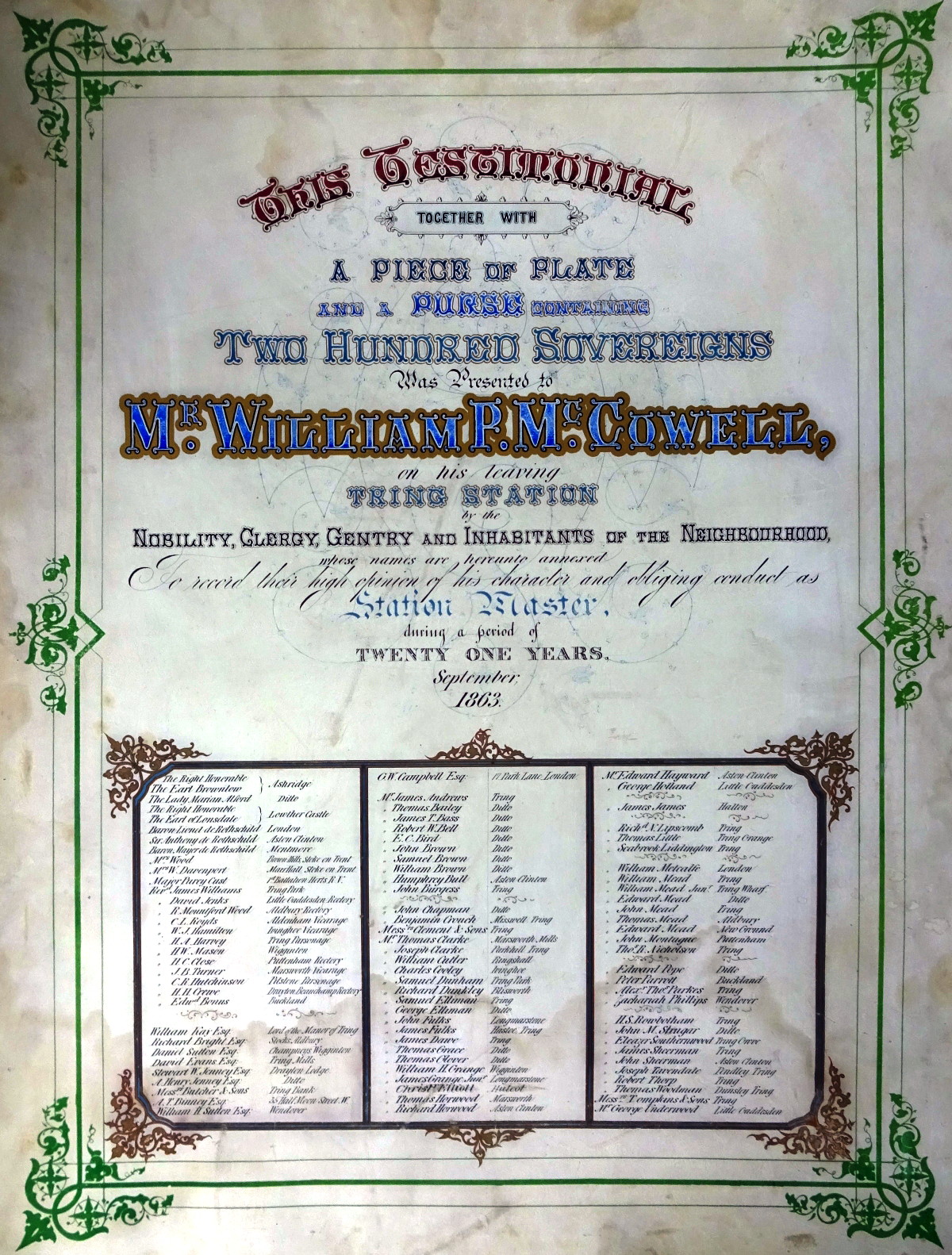

ARTHUR MACDONALD (BROWN) M.A.

(1861-1951)

The following notes relating to the railway at Tring were written by

Arthur MacDonald Brown (usually known as Arthur MacDonald) some time

during the late Victorian era. They were intended to form a section

of a published book on the complete history of the town, and it is

apparent that he put much time and effort into its research.

However, although some sections are detailed, others comprise rough

notes that were probably awaiting further research before

being written up.

|

|

|

Arthur Macdonald (Brown). |

Much to the regret of today’s local historians the book was

never completed, for as MacDonald said, “I have quailed at the task

of putting them [the notes] into proper shape for a

parish history, but have amused myself in old age by utilizing some

of them in a gossiping narrative.” In 1940, he did just that

when he published a small book entitled That Tring Air to

help raise funds for the Tring Nursing Association.

This transcription of MacDonald’s section on the railway is taken

from his original writing and, apart from some editorial notes [bracketed

in italics], the extracts appear exactly as he wrote them. In

some places they contain their author’s quaint Victorian turn of

phrase, in others his rather anecdotal style. It may well be that

modern research and the findings of later writers and railway

historians call into question some of the facts and information, but

in essence the story of the coming of the railway to Tring remains

unaltered. Although his image (enhanced by a typically late

Victorian heavy moustache) suggests a serious gentleman, it probably

belies a more light-hearted character, for he also wrote a number of

humorous poems, songs and sporting ditties.

Arthur MacDonald was the second son of William Brown, a land agent

of Tring, who founded the local firm of estate agents, Brown & Merry. After attending Berkhamsted School and Jesus College, Cambridge, he

became a partner in the family firm in which he fulfilled a

distinguished career. He was an expert in ecclesiastical and lay

tithes, as well as in estate management, also undertaking the role

of Examiner in Surveying for the Civil Service.

TRING RAILWAY:

Notes written by Arthur MacDonald (Brown) c.1890.

In October 1837 the London & Birmingham Railway, now the London

& North-Western, was opened to Tring. Two companies were formed in

1830 to form lines from London to Birmingham; one by Oxford and

Banbury, the other by Coventry. They amalgamated and on George

Stephenson’s advice chose the latter route. The first survey had

been made in 1825, but the commercial crisis of that year stopped

further progress. The final surveys were made in 1830 and 1831, and

Robert Stephenson is said to have walked over the ground no less

than 20 times in selecting the best route. Of course the engineering

difficulties were the lightest obstacles that had to be overcome. The opposition from all classes was almost overwhelming. The

surveyors had exciting times, and had often to adopt stratagems to

get their work done. In one case the owner was so determined in

keeping them off his land, and so vigilant in his determination,

that the necessary levels had to be taken in the middle of the

night, with a dark lantern held on the instrument and another to the

staff. Another Reverend owner had to be circumvented by being

watched safely into the pulpit, when the work was snatched. In not a

few cases it came to a pitched battle, and the invaders had to get

navvy protectors.

The Route – the direct route from Watford to Leighton would be

by way of Hemel Hempstead and the Little Gaddesden

and Dagnal valley, but we have to thank the powerful opposition of

the landowners in that district for turning the line out of its

course down the Berkhamsted valley and so by Tring. The opposition

to the line was by no means confined to the landed interest; public

meetings were held at many places, protesting against railways in

general on every conceivable plea. The tradesmen foresaw the loss of

all their business, those who lived within a mile or two of the line

expected their houses to be set on fire, the air was to be poisoned,

all horses were to emigrate, and all cattle were to be frightened to

death.

There is said to have been a public meeting held at Tring to protest

against a proposal to bring the line from New Ground to near Grove

turn, this being considered dangerously near. They changed their

tune when the line was being made, and wanted a branch, but the

opportunity had passed.

The Bill was thrown out by the House of Lords in 1832, seven-eighths

of the owners along the line being dissentient. It was brought in

again however and passed in 1833. The average cost of the land was

£6,300 per mile, which at one chain wide is equal to nearly £80 per

acre. The cost on other lines varied from £3,000 to £14,000 per

mile.

Robert Stephenson was appointed engineer-in-chief. The section from

Camden to Tring was completed first, Camden being originally

intended for the terminus. The Contractor for the section from Tring

to Leighton was named Townshend; he was one of the unfortunate

eleven out of the eighteen contractors who became bankrupt over the

business. Contracting on such a scale was new, and the ins and outs

of estimating were little known. There were no leviathan contractors

of the modern Lucas & Aird type

[an engineering company founded

in 1848 and trading until 1990].

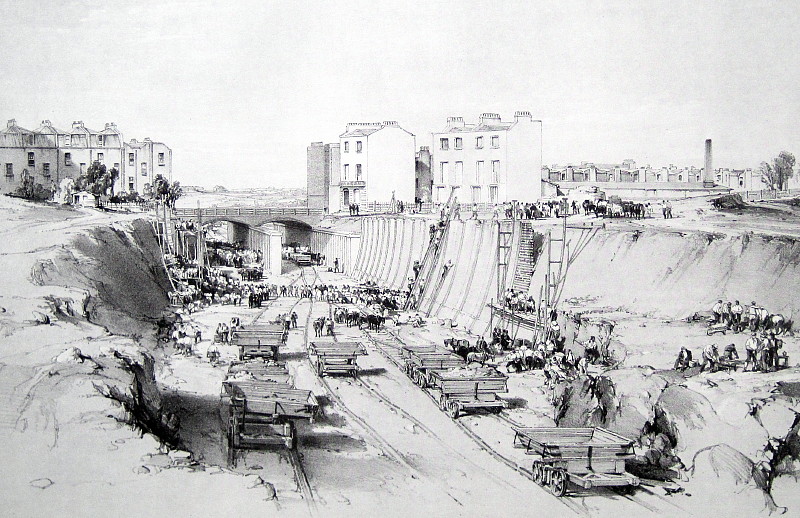

The Tring Cutting – the largest on the line, is well known as a

stupendous engineering work, and nearly approaches the limit of

depth at which tunnelling becomes preferable. It passes through the flintless lower chalk ridge of Ivinghoe for nearly two miles and a

half. Its average depth is forty feet; for a quarter of a mile it is

57 feet; a million and a half cubic yards of chalk were removed when

it was first made, and they form an embankment to the north six

miles long and 30 feet high, besides huge spoil banks of superfluous

material.

The work was commenced at Pitstone end, and took nearly three years. The method of raising the chalk was peculiar and attended with no

little danger. 30 or 40 horse-runs were erected – steep inclines

made of three or four planks side by side wide enough for the legs

of a barrow to stand on, placed down the slope of the excavation. In

the field at the top was a strong post with a pulley upon it; over

this a horse drew a rope and chain which passed down the slope and

was hooked on to the barrow. When the barrow was full, the word was

given, the horse was trotted out into the field, the navvy hung to

the handles of the barrow and ran up the planks in an almost

horizontal position, taking his chance of a lump or two falling back

on him. Any irregularity in the motion of the horse, and down went

the man, barrow and all, and he had to be very quick to escape

falling under it. All the men were precipitated to the bottom many

times, but such is the toughness of the British navvy that there was

only one fatal accident. The engineer, seeing the great risk of the

method, invented a kind of lift consisting of a small tram on lines

carrying two barrows, but this the men disapproved of and broke,

preferring the old method to a labour-saving contrivance.

|

|

|

Horse (or barrow) run in use on

the Manchester Ship Canal. |

System of ‘ganging’

– the price per cubic yard paid to the men

varied with the depth from seven pence to a shilling, and the men

formed themselves into corresponding gangs of from seven to twelve,

each man thus taking a penny per yard raised by the gang. The

contractor found the horses and runs, the men undertaking to dig,

raise and deposit the chalk. One of each gang acted as ‘runners’,

and they could run 100 barrows in a hundred minutes up a 90 ft

plank. The ‘diggers’ too had their dangers. The practice was to

undermine a length of some yards, leaving one or two pillars of

chalk or ‘legs’ to hold it up, then to cut away the legs and by

driving piles into the top, bring down the overhanging mass. A

well-known old inhabitant of Tring, Bunce, was engaged in this work,

and was cutting away a ‘leg’ when the mass came down. He and his mate were buried in the falling chalk up to

their shoulders, but escaped without broken bones.

Townshend’s

[Thomas Townshend, 1771-1846, civil engineer and

contractor] section commenced about 200 yards north-west of

Tring Station; Cubitt [Sir William Cubitt, 1785-1861, founder of

W. & L. Cubitt, civil engineers] taking the nine-mile Kings

Langley to Tring section [according to company records,

the Cubitt contract terminated at the northern end of Northchurch

Tunnel, the short section between the Tunnel and Tring Cutting

(contract 6B) being let to Richard Parr]. The

bridge at Northfield has always gone by the name of the ‘bird-house

bridge’, from the circumstance of a Dwight from ‘the hills’, one of

the originators of the pheasant breeding business

[Matthew Dwight, game farmer], bringing a

hut on wheels or ‘bird-house’ down to that point, where he lived and

sold beer to the navvies.

The regular navvies or ‘old hands’ commenced the cutting, and

thought they could do it without assistance, but it was found

necessary to employ quite an equal number of local men when the work

got deeper, and they soon showed that they could hold their own with

the old hands, not only at digging, in which Tring men have always

excelled, and still do so, but at this (to them) new practice of

‘running’. This excited great jealously among the old hands, which

rankled in their minds long after, and on other works a Tring man

was in danger of getting his head punched if the others knew where

he came from.

|

Former stone block

railway sleepers in use as boundary

markers at New Mill, Tring. The two

holes in the top of the block on the

right were to hold the oak peg fasteners

for the rail chair. The other blocks are

up-turned. More former sleeper blocks

are in use as coping stones on the

nearby canal at Cooks Wharf.

|

|

|

|

|

|

A section of line laid on stone

block sleepers. |

Altogether there were about 500 men employed in the cutting, and

they brought some life of a curious character into the

neighbourhood. Ivinghoe was Mr Townshend’s headquarters and pay

office, and many of the men lodged there and at the other villages

near the line. There was a lively party of eight at The Bell

in Tring, who occasionally gave some trouble to the authorities of

public order. Mr Bull and Mr Philbey were Parish Constables at that

time, and the former was called in on several occasions when the

navvies were having a row, when he laid about him with his staff of

office in a highly business-like and effectual manner. Mr Philbey,

too, had the faculty of arriving with great celerity on the scene of

action – he drove furiously a small pony cart and was familiarly but

irreverently called ‘Flying Issac’.

‘Tompkins at the Tommy Shop’ is an expression which denotes to every

man, woman and child in Tring and the villages round, an emporium

where almost everything can be obtained which makes life worth

living, from a loaf of bread to a lawn mower.

[Mary Tompkins &

Sons, according to a billhead of the time - Wholesale & Retail

Ironmongers, Coppersmiths, Braziers, Tin, Iron & Zinc Plate Workers,

Stove-grate & Range Manufacturers, trading at 51 & 52 High Street,

Tring, now the premises of F. W. Metcalfe & Son] This

establishment rose into prominence at the time of the construction

of the railway, being the rendezvous for the navvies to get their

‘Tommy’and also their tools. [The navvy knew that he was a

helpless being unless he could get his tommy – drink was ‘wet

tommy’; and this word came to mean all supplies – beef, bacon,

cheese, bread, butter, and tobacco.]

During the excavation many fossils were found, chiefly oysters,

nautili, ammonites etc. also numbers of concretions of iron pyrites,

popularly known as ‘thunder bolts’, some spherical and some

cylindrical, but most irregular and fantastic in shape, and all with

the common radiating structure.

At the Icknield road bridge 15 or 16 skeletons were found, and some

Roman pottery. Two urns were found at the Pitstone end, and these

are now said to be in the possession of the Antiquarian Society.

The line and bridges

– the lines were originally laid on square

stone blocks, instead of wooden sleepers. These were however

replaced throughout by timber on account of the excessive vibration,

and many of the old ‘railway blocks’ may be found forming useful

bases for shed posts, corner stones, mounting blocks for horsemen

etc. in the neighbourhood of the line.

[Some of these may still

be seen around the locality – notably at Hastoe Cross and in front

of The Pheasant public house in New Mill.]

Another replacement found necessary was the parapets of the road

bridges over the railway, which first consisted of open palisades of

short cast-iron doric pillars on stone bases. It was soon found that

horses passing over the bridges were terrified by the engines and

trains roaring below, in full view of the animals. These had to be

replaced everywhere by high, solid, brick walls. (I have not seen

the old palisades used up anywhere but as the front fence of my own

house, where they make a substantial, imposing, and everlasting

frontage-guard, the only drawback being their frequent use by the

passing boy as a dulcimer by drawing a stick along them, to the

detriment of the paint.)

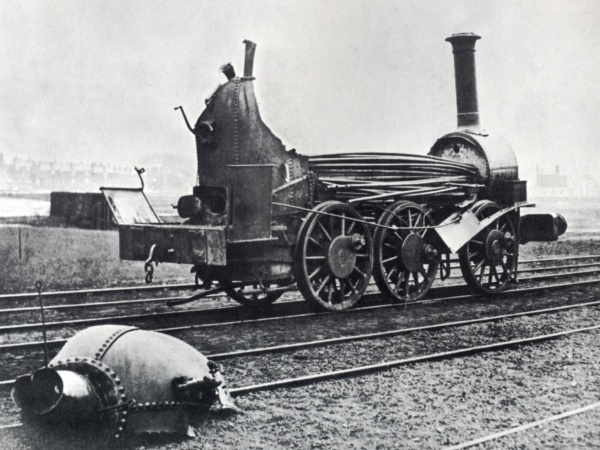

The first locomotive

– the first locomotive was brought down in

pieces by canal, and housed in a barn at Pix Farm, beyond

Berkhamsted until wanted. It was a heavy 6-wheeled engine,

used to test and consolidate the line and was called the ‘Harvey Coombe’. There was great excitement to see this wonderful beast when it took

its first run down to Tring. One old wiseacre who had been working

at the cutting refused to go with the others to see it, remarking

that it was ‘Harvest home’ rather than ‘Harvey Coombe’,

meaning that it was the signal of their job being finished. This

ponderous joke, after a life of 50 years, is still repeated by the

survivors of that time with brimming hilarity.

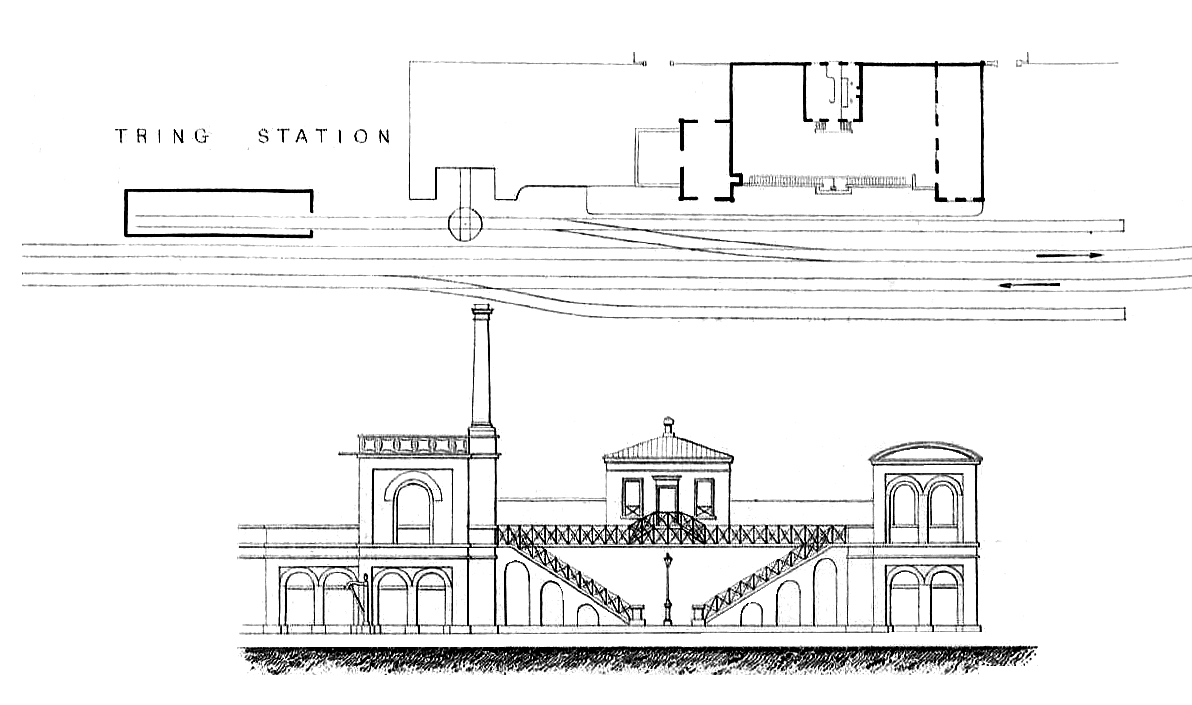

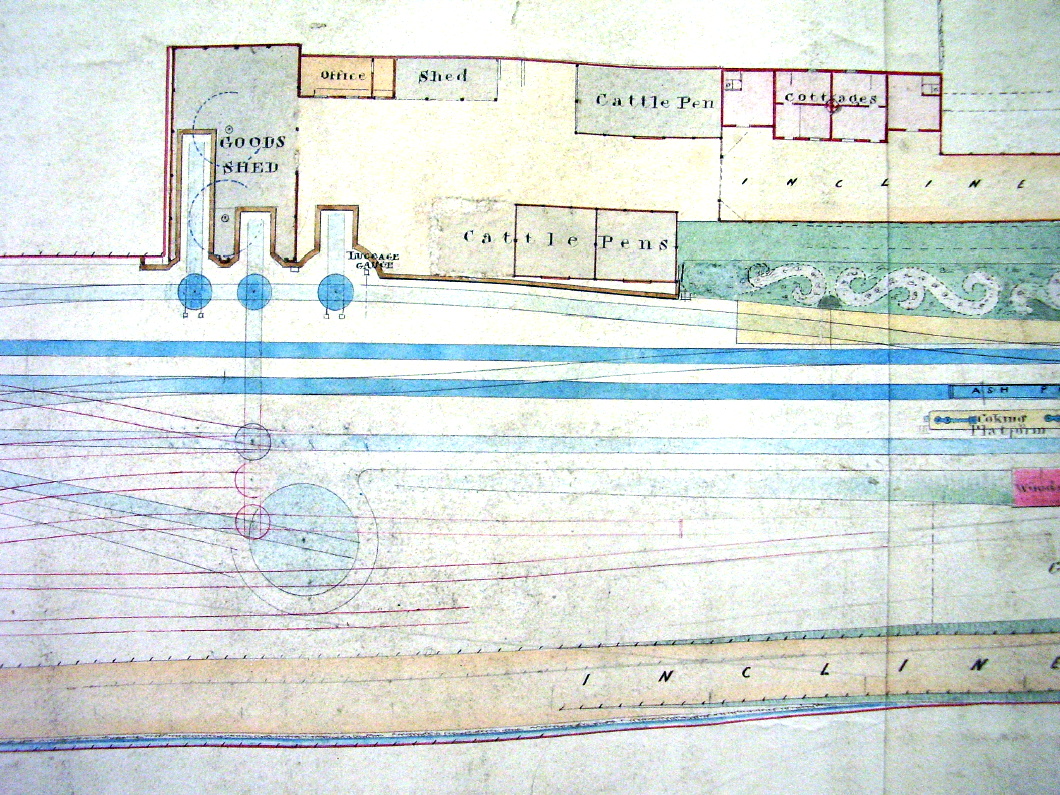

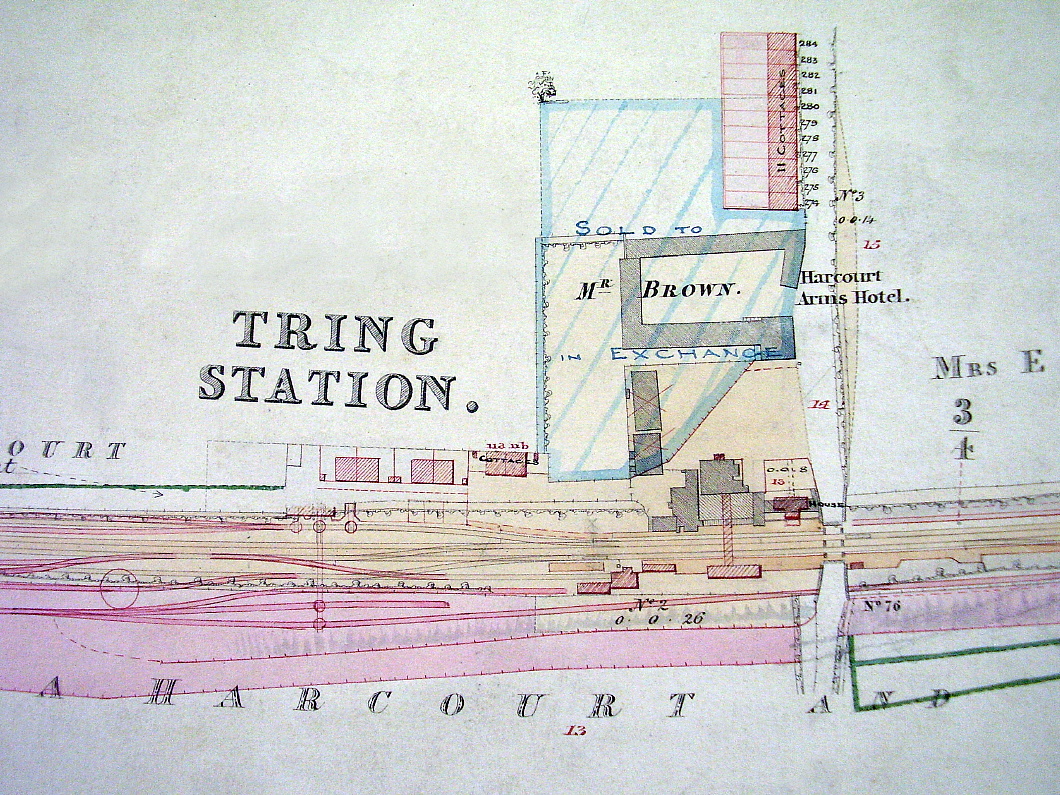

Tring Station – it was the intention of the Company to place a

station at Pitstone Green at the north-west of the cutting, and

perhaps another at New Ground. The leading inhabitants of Tring,

however, finding their town about to be left out in the cold began

to agitate for a station at Pendley, but the owners of the Harcourt

estate had made such opposition to the line and asked such a high

price for the land, that the Company had taken as little of it as

possible. A public meeting was held at the Rose & Crown to

memorialize the Directors. Their reply was that if the land could be

obtained at a fair price they were quite willing to make the station

at the desired point, but that they were not going to pay a fancy

figure, and if the town wished it, they must get the land and if

necessary pay the difference.

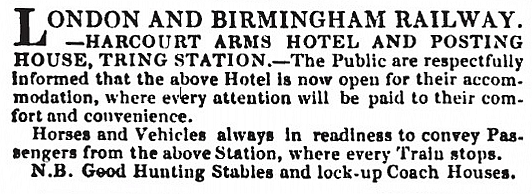

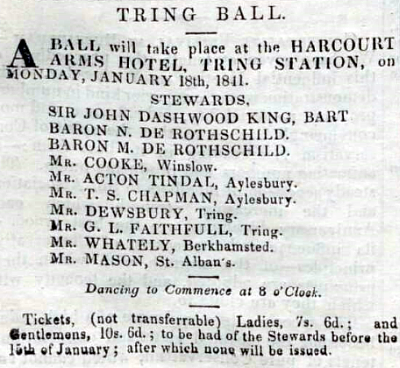

Mr. John Brown of the Tring Brewery had noted this spot as not only

the nearest point to the town, but also as a convenient one for the

erection of a Hotel & Posting House; this gentleman not sharing the

opinions expressed by the coach proprietors, that horses, vehicles,

and roads would be of no further use after the arrival of railways.

On Sunday morning May 7 1837 the brothers John and William

[the

father of Arthur MacDonald, author of these notes] Brown set out

on a drive to Sunninghill, Berks, to interview Mr. Houghton, the

Agent for the Harcourt estate, with a view to applying a ‘lowering’

treatment. On arriving there, their foe had broken cover and they

started off again in pursuit to Ruislip. Here they received a

temporary check, but finally ran into him in the open ascending

Harrow Hill, after a rattling day with their old grey horse and

chaise. An appointment with Captain Harcourt was arranged, and

finally the two acres of land required were obtained for 300

guineas, instead of the thousand the price asked. Half an acre was

set apart for the station, and in the spring of 1838 The Harcourt

Arms now the Royal Hotel was commenced, under the

superintendence of Mr. Aitchison, the Railway Company’s architect,

and completed in March 1839. [George Aitchison, 1792-1881. After working on warehouse design he came into contact with some of

the directors of the L&B Railway, and devised a system of

book-keeping for the works, as well as acting as architect for the

intermediate stations. He also, according to his obituary, gave

Robert Stephenson “the aid of his experience in carrying out the

structural works on the line”. Not to be confused with his

better-known son, George, architect of Leighton House, London.]

There was some idea of calling the station Pendley, but the name

Tring was adopted. The Station Road was soon formed, and our little

town was thus put into railway communication with the outer world

after so many vicissitudes, and its station turned out to be one of

no mean importance on the line. It was selected as a principal or

first-class station at which all trains stopped, on account of its

being at the highest point of the line, and an engine being usually

thrown off here, also on account of the purity of the water, which

did not fur the boilers. The level of the rails at Tring Station is

about 330 feet above the line at Euston, and 420 feet above the

level of the sea. It is thus about level with the top of St Paul’s. There is only a short length of the line in Tring Parish (a mile and

four chains), from the Northfield or ‘Birdhouse’ bridge to the Icknield Road bridge at the Folly Farm. The Station is in Aldbury

parish.

Aylesbury Branch Line – was constructed by a private

company formed at Aylesbury in 1835, the first intention being to

leave the main line at the proposed Pitstone Green Station, passing

on the south side of Cheddington Hill by Long Marston and Drayton

Beauchamp. When Tring Station was secured, it was to have been made

the junction, the branch leaving the main at the Pitstone end of the

cutting as proposed. Finally, Cheddington was chosen as the

junction, which has the advantage of being perfectly straight all

the way and having no cuttings and very little embankment, and was

opened on 18 June 1839. It was soon after purchased by the London &

Birmingham Co.

The opening of the line

– the first portion of the main line

completed was that between London and Boxmoor. This was opened in

the summer of 1837, and the curiosity to see the new mode of

travelling drew a large crowd to Boxmoor from all parts of the

country round. Brass bands played, and many performed during the

journey. At the end of that year the line was opened to Tring, and

in April 1838 the whole line was completed with the exception of the

part between Rugby and Denbigh Hall (Bletchley), which was delayed

by the great engineering difficulties encountered in making the

Kilsby Tunnel. Omnibuses connected the two portions until the line

was finished, and the first train ran through from London to

Birmingham on 17 September 1838.

In 1836 a Cheltenham & Tring Railway was being projected,

this portion of the proposed route starting from Tring Station on

the L&B by Grove, New Mill and Drayton, to Aylesbury and Thame.

In 1845, the year of the railway mania, no less than 1,428 new lines

were projected, the London & Birmingham and many other companies

then paying 10%. Some of these affected this neighbourhood:

Tring, Reading &

Basingstoke Railway was to have joined the London &

Birmingham at Pitstone Green and passed near Buckland, Halton,

Risborough and West Wycombe.

A second Tring &

Aylesbury line was to have left the L&B at the same point as

the last mentioned, approached the old branch at Long Marston,

and passed through the parishes of Weston Turville and

Broughton.

The

Buckinghamshire Railway was to have gone down the Amersham

and Wendover Valley, from Willesden to Banbury, along the same

route from Aylesbury as the present, being intended to work with

and relieve the L&B.

The Oxford &

Cambridge line would have passed by Aylesbury, Cheddington,

and Dunstable.

There was a Tring

and Banbury Railway projected, this may possibly be the same

as one of those mentioned above.

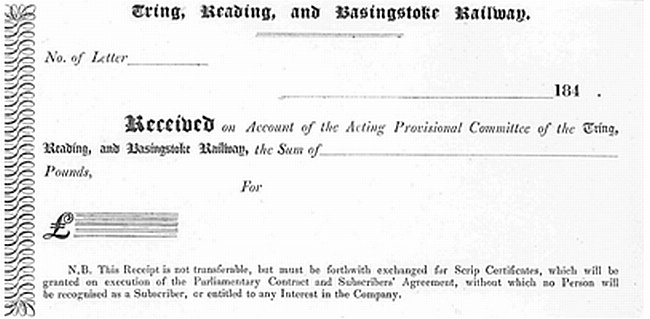

Receipt issued in 1845 by the projected

Tring, Reading and Basingstoke Railway Company.

The company was dissolved in bankruptcy in

September 1846.

By an entry in the Tring Vestry book, 4 April 1845, it appears that

application was made for power to rate in the usual manner a line

which was to have passed through Betlow, this Lordship being under a

special Act as to rating. The Railway was called the London,

Worcester, & South Staffordshire and was to have run from the

L&B at Marsworth to Worcester.

In 1846 the London & Northwestern Railway was incorporated,

including the London and Birmingham, Grand Junction, and Manchester

& Birmingham lines.

Later development. – When the L&B Railway had been opened 17

years, it was found that within a circle of two miles round each

station between the Metropolis and Tring the total amount that had

been expended in new buildings was only £22,000. It was then

suggested that if a first class pass, available for a few years,

were presented to every person who constructed a residence of a

certain annual value near the line, all parties would be benefitted.

In eight years, between £240,000 and £250,000 were spent in

house-building in those localities, and the amount expended since

has been enormous.

Beech Grove, shortly before demolition in

1997.

Tring did not however share in this wholesale suburbanizing, and

there is only one house whose owner took the advantage offered by

the Company of a first-class pass for 21 years.

[This was

William Brown, the father of the author of these notes. The house

was named Beech Grove, before demolition for many years the

Headquarters of the British Trust for Ornithology.]

――――♦―――― |

|

TRING CUTTING

“Leaving the Tring Station towards Birmingham the traveller passes

under a bridge, and immediately enters one of the most stupendous

cuttings to be found in the country. The contemplation of this vast

undertaking fills the mind with wonder and admiration.”

The London and Birmingham

Railway, Roscoe and Lecount (1839).

Above: an unrebuilt Royal Scot-class locomotive and train in Tring Cutting.

Below: Midland Compound 1114 in Tring Cutting.

A Midland Compound in Tring Cutting

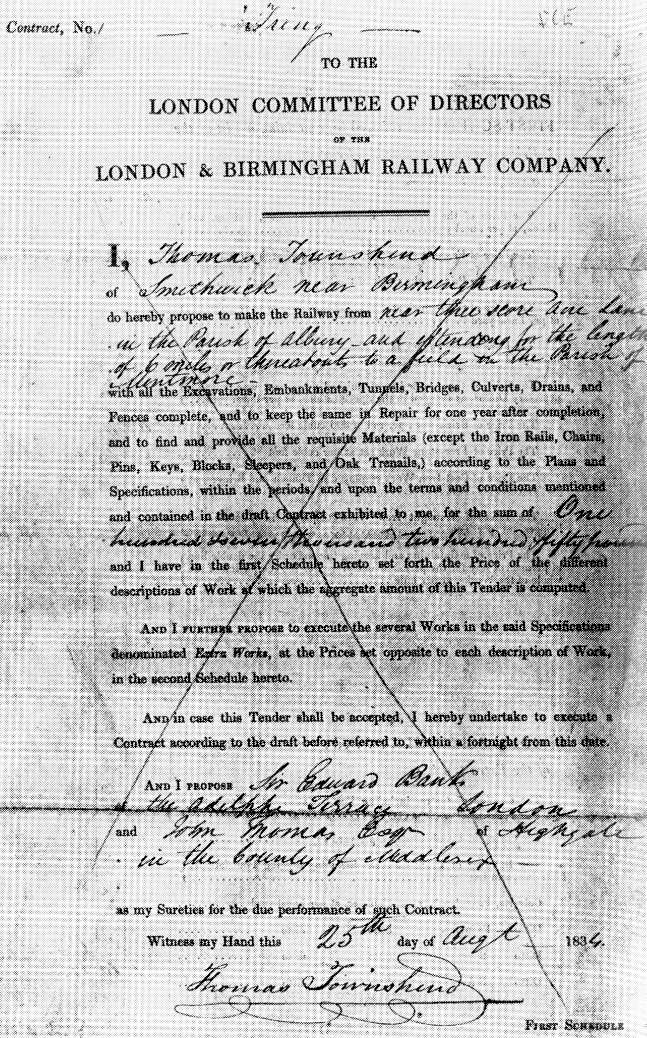

Stephenson was well aware that one of the most labour-intensive

tasks along the route would be the excavation of the 2½-mile Tring

cutting. Thomas Townshend (1771-1846), an established civil

engineering contractor from Smethwick, secured the contract to

construct the 6-mile section of the line from a point to the north

of Tring Station, his tender price being £107,250. Although

approaching the end of his career, Townshend was very experienced in

heavy earthworks, drainage and canal cutting, having earlier worked

on projects for the great civil engineer John Rennie Snr.

Townshend’s responsibilities were considerable. Not only did they

entail the construction of the cutting, numerous bridges and the

very long embankment to the north of the cutting, but he also had to

build culverts and drains, erect fencing, and lay the rails, blocks,

chairs and sleepers. All this he was required to maintain in good

order for a year after completion.

|

The first page of the contract for

excavating Tring Cutting and for other work,

including the long embankment to the north. It was

signed by Thomas Townshend on 25th August 1834. The

contract price of £107,250 included keeping all the

works in good repair for one year after completion. |

Because of the size of the task, work commenced on the cutting in

1835, well ahead of other work in the Tring area. Townshend set up

his headquarters and pay office at Ivinghoe, probably at the

Kings Head, from where he supervised his army of sub-contractors

and labourers. At first, all went moderately well. Apart from the

huge volume of chalk to excavate, it was anticipated that there

would be problems with the workings being flooded by groundwater (if

not by the weather!):

“The excavation,

through Tring-hill, is proceeding rapidly. Mr Townshend, the

contractor, has upwards of 500 men employed besides a great number

of horses. It is expected they will intercept the Bulbourne springs

when they get deeper. These springs at present come directly into

the Grand Junction Canal . . . .“

The Mechanics’ Magazine

(vol.23) 1835.

. . . . and as the lower levels of the chalk terrain – which form an

aquifer – were reached, so commenced the predicted flooding. It was

also anticipated that weather conditions would turn the bottom of

the cutting into a mire, and that this would also hamper progress:

“In the event of a

sharp frost, the ground, which is a sort of chalk rag, will slake

down like lime, and will consequently be a great nuisance after the

rail is finished. The banks of the GJC,

[Grand

Junction Canal]

in the deepest cuttings

collateral with the railroad, are more than one to one, yet the

slips which have occurred after a frost have been prodigious.”

The Mechanics’ Magazine

(vol.23) 1835.

Following the line’s opening to Tring in October 1837, the

groundwater encountered in the cutting and the weather combined to

make working conditions impossible. In his history of the line,

Peter Lecount, one of Stephenson’s engineers, writes:

“The Watford Tunnel was

finished, and but little remained in the excavation. The state

of the three succeeding contracts was also very satisfactory.

The North Church (sic.) Tunnel was

finished; and, with the same exertions on the part of the

contractors which had hitherto been evinced, there appeared no

reasonable doubt but that the works might be all completed, and the

line opened to Tring in the autumn. The quantity of water

yielded however by the Tring cutting, in addition to that which had

fallen in rain, together with the argillaceous character in the

chalk in that cutting, rendered absolutely necessary to stop all

proceedings on that embankment. It had, in fact, been

proceeded with, till it was at last quite impossible.”

A History of the Railway

connecting London and Birmingham, Peter Lecount (1839).

Stephenson submitted regular reports to the Railway Board relating

on the progress of the work and its cost. In February 1838, he

reported that:

“The Tring contract,

which comprehended the most extensive excavation on the line, is now

nearly completed . . . . it has, however, been impracticable to

proceed as intended due to the intense and protracted frost, which

set in a few days after the beginning of the year, continuing up to

the present date, without a single available interval of one day. The contractors have been urged, and every expedient resorted to,

for the purpose of proceeding with the permanent rail, so as to

expedite the approaching opening, but without success. There still

remains work which, as nearly as can be calculated, must require

three weeks to perform, after a thorough thaw has taken place.”

Lecount summarised as follows:

“The railway opened to Tring in October 1837, as had been

anticipated; but a winter of unusual severity and duration, by

retarding the remaining works, made the farther opening in January

1838 impracticable; so intense, in fact, was the cold, that the

ground was frozen two feet in depth, and although, by means of large

fires and using hot mortar, brickwork was in some cases carried on,

every one at all conversant with such works, will readily know how

much time must be necessarily lost under weather which for weeks

kept the thermometer at nearly zero.”

A History of the Railway

connecting London and Birmingham, Peter Lecount (1839).

The minute book of the Institution of Civil Engineers (vol. 90, part

4) records Stephenson’s comments on the immense volume of ground

water that flooded into the workings:

“. . . . The Tring

cutting on the L&B Railway presents another forcible example of the

constant and rapid absorption of water by the chalk. In the

execution of that cutting a very large quantity of water was

encountered, notwithstanding the situation was on the summit of the

chalk ridge, forming the actual brim of the basin, where it could

not be supplied with any water but such as fell upon the immediate

neighbourhood, yet it yielded upwards of one millions gallons per

day [50 cubic feet], and continues to yield an extraordinary quantity up to this

hour, without any sensible diminution.”

A further difficulty arose when the Grand Junction Canal Company

claimed that the excavation had resulted in a considerable loss of

water that would otherwise have flowed into the canal’s summit,

which lies a short distance to the west of the railway cutting. Although Stephenson had the flow measured and disputed the argument,

the canal company threatened legal action. To settle the issue, the

railway company undertook to build a tunnel through which drainage

water could flow from the railway cutting into the canal’s summit,

an exercise that added to the cutting’s expense.

Arthur MacDonald’s account (c.1890) helps to confirm and

explain this:

“Much water was met

with in making the Tring railway cutting, and culverts were laid

below the level of the rails on each side, which carry considerable

quantities of water to the Canal by a tunnel under Parkhill Farm.

One result of the cutting was to drain Bulbourne Pond entirely. It

was a long sheet of water, three-quarters of an acre in extent, and

in the report made in 1838 on the damage, which was assessed at

£150, it is described as a very delightful place from which any

good-sized fish had been taken . . . .”

This pond – also known as “Bulbourne Water”,

for it was quite a large expanse – was on the Grove Estate, at that

time in the ownership of the Seare family.

|

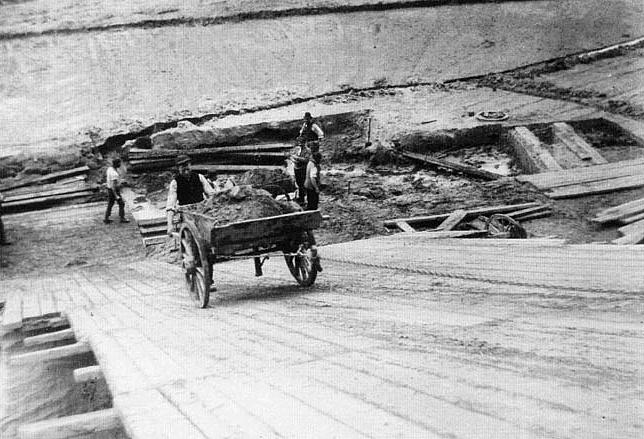

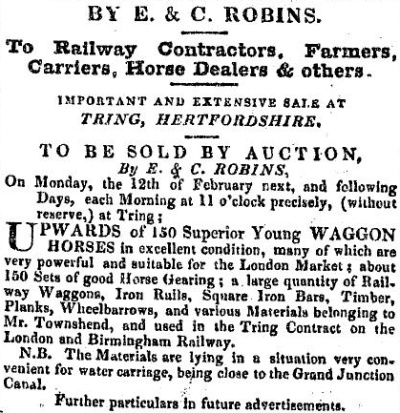

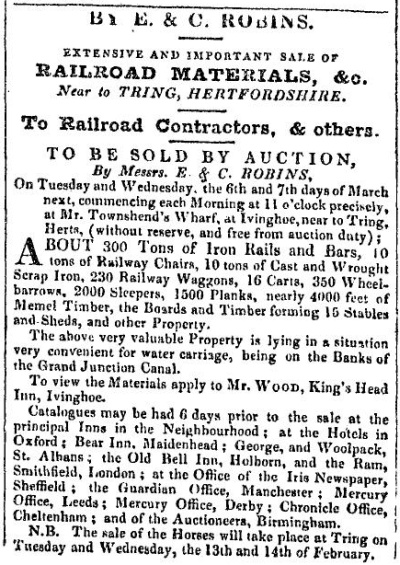

Sale of Thomas

Townshend’s assets. Both advertisements

appeared early in 1838. It is

interesting to see the wide range of

equipment that a railway contractor of

the age had to provide, indicative of

the private capital that was necessary

to undertake such work. |

|

|

Auction of Townshend’s assets. The Derby

Mercury, 24th January 1838.

|

|

|

Bucks Herald,

7th January 1854. |

Apart from problems with the weather and the terrain, another blow

was dealt when Townshend was forced to relinquish his contract. He

had been hit by rising labour rates and the problem of finding

sufficient local accommodation for his large workforce, and his

costs began to outstrip his estimate for the work, a familiar story

throughout the whole of the construction work. The railway company

had assisted other contractors with loans for temporary housing, but

refused to help Townshend. In October 1837, he filed for bankruptcy

in the sum of £24,212. Townshend was just one of eleven of the

original 30 contractors employed on the line to fail, although his

failure came as a surprise, as Peter Lecount relates:

|

“. . . . the person

who had the Tring contract became bankrupt – a matter least

expected, perhaps, of any. He was a man of capital talent, and had

an established reputation for years as an able contractor. The works

he had on hand were of the most extensive nature, and ought to have

paid him well; when, to the surprise of everyone who knew him, he

was suddenly declared to be in difficulties . . . . leaving the work

at Tring, including the heavy cutting through the chalk, to be

finished as best it might.”

A History of the Railway

connecting London and Birmingham, Peter Lecount (1839).

|

The cutting was eventually completed under the supervision of the

Company’s engineers using some of Townshend’s staff to control the

workforce, its final cost being £144,657 against the contract price

of £107,250.

To take on a civil engineering project, such as that at Tring, a

contractor needed to engage an appropriately skilled workforce and

provide them with a wide range of equipment. This is evident from

the advertisements for the auction of Townshend’s assets, which give

some idea of the amount of capital that a contractor required to set

up in business. Further advertisements six months later imply that

Townshend’s property was used until work on his contract was

complete. In June, 1838, a further sale was held at Pitstone, in

which chain pumps, block cranes, a large Iron Crab windlass, timber

and stone carriages, as well as materials from many temporary

erections used to supply the needs of the dozens of horses (e.g

the contents of several large stables), blacksmiths’ bellows,

anvils, vices, and a chaff-cutting machine, were put up for sale.

|

|

|

A farmer’s bridge near Pendley

Cottages. |

A deep cutting necessarily entails the construction of road bridges,

which require a small army of bricklayers, joiners and labourers. Four bridges cross the Tring railway cutting – at Tring station, a

farmer’s accommodation bridge near Pendley Cottages, Marshcroft Lane

and Bulbourne (Folly Bridge, where the cutting reaches its

maximum depth).

Little can be seen of Stephenson’s original bridges, for they were

largely reconstructed when the cutting was widened in 1859 (to three

lines) and 1876 (to four lines), and during the electrification of

the line in the 1960s, but all remain three-span arches with a new

48 feet centre span. Jean Davis writes in Aldbury, the Open

Village (pub. 1987) that a map of 1840 shows another bridge,

which carried the church path across the railway. This bridge was

later removed by the railway company to make way for further

development, and the resulting compensation (£140) was used by

Aldbury Vestry to build a house for the village school master.

――――♦―――― |

|

THE NAVVIES

|

|

|

The navigator, known as a

‘navvy’

or ‘banker’. |

In his notes, Arthur MacDonald describes the navvy’s working

practices and the arduous nature of their existence, which required

skill to avoid serious injury. Today, people generally think of the

navvy as Irish; some were, but the majority were English or Scots

with a smattering of other nationalities. In this area, many were

local men who, due to the agricultural depressions of the early 19th

century, lived in the shadow of the workhouse. In the public mind,

navvies were generally reckoned rough and depraved, and in the towns

and villages along the railway’s route they were awaited with

apprehension – if not trepidation – and sometimes with

good reason, as the following accounts from the Tring Vestry Minutes

illustrate:

|

14th March 1836. Boxmoor.

A great riot took place here last night between the English and

Irish Bankers working on the new railroad.

30th September 1836. Berkhamsted. There was a great riot here

today. A party of Irish navvies passing through the town were

attacked by parties of navvies working on the L&B railroad. The

Irish navvies were knocked down, severely beaten, stones thrown at

them, and dogs were set on them to tear them. The Irishmen returned

again later in the day, and there was a great riot in the town. Several inhabitants of the town assembled and took some of the

rioters into custody. There has been a lot of disturbances in the

neighbourhood with these men, many of whom are but rough uncouth

savages, as fierce as tigers.

See also

Annex. |

In spite of such disturbances, while endorsing the general view, the

civil engineer Peter Lecount suggests that acts of violence –

presumably on the local populace, rather than among themselves –

were rare:

“These banditti, known in some

parts of England by the name ‘Navvies’ or ‘Navigators’, and in

others by that name of ‘Bankers’, are generally the terror of the

surrounding country; they are as completely a class by themselves as

Gipsies. Possessed of all the daring recklessness of the Smuggler,

without any of his redeeming qualities, their ferocious behaviour

can only be equalled by the brutality of their language. It may be

truly said, their hand is against every man, and before they have

been long located, every man’s hand is against them; and woe befall

any woman, with the slightest share of modesty, whose ears they can

assail.

From being long known to each other, they in general act in concert,

and put at defiance any local constabulary force; consequently

crimes of the most atrocious character are common, and robbery,

without any attempt at concealment, has been an every-day

occurrence, whenever they have been congregated in large numbers;

but they were so thinly scattered over the London and Birmingham

Railway, that their depredations partook more generally of a

deceptive character, and acts of violence were rare.”

A History of the Railway

connecting London and Birmingham, Peter Lecount (1839).

A long account of life as a navvy was written by a well-educated

young man whose ambition was to become a civil engineer ― whether he

succeeded is not known, for his account is anonymous. He left a

first-hand record of his work on the construction of the line

between Watford and Tring, including everyday problems, some of

which could arise from a most expected quarter:

“In February 1836 Frazer

[an engineering contractor] took a

contract to dig ballast at Tring; and I was sent down to have charge

of the job; on which there were about 50 men employed. The job was

bravely started, and things went on smoothly enough for the first

ten days, when, lo! It was reported that there was a bogie

[gremlin] in the ballast pit.

These men who could defy alike death and danger became panic

stricken. The idea that the pit was haunted filled them with a

mortal terror, of which the infection heightened as it spread.

At first the current rumour was that picks, shovels, and barrows

were moved from their places nightly by the bogie; then it came to

be that earth was dug, barrow-runs broken up, tools spoiled, trucks

shunted, and even tipped by his nightly visits . . . . Finally the

men struck work in a body. Reasoning with them was useless;

the old ganger, as spokesman for the rest, declared as the result of

his former experience that ‘there was no tackling the old un’

[the Devil], and to a man

they refused to re-enter the pit.

. . . . Frazer came down the same night, bringing with him a band of

chosen roughs from Watford tunnel . . . . Frazer expected much from

this gang; and the next morning they commenced work in earnest. But

on the second day they too became possessed with the same

superstitious terror as their predecessors; and they also struck. Persuasives, promises, and threats were alike unavailing; the men

would not ‘go agin the bogie’; and the pit was once again deserted.

Frazer raved like a madman. He was under a penalty to dig so much

ballast per week . . . . suggested to set on a gang of farm

labourers; of whom there were plenty out of employ. He assented;

and, in a day or two, we were at work again swimmingly; and

continued so for a week, when the old contagion showed itself, and

another suspension appeared inevitable. It came at last, but was for

some time averted by the allowance of rations of tommy in addition

to wages, and by seeing that every man was half drunk before he went

to work . . . .”

‘Navvies as they used to be’, from

Household Words, Vol. XIII. (1856).

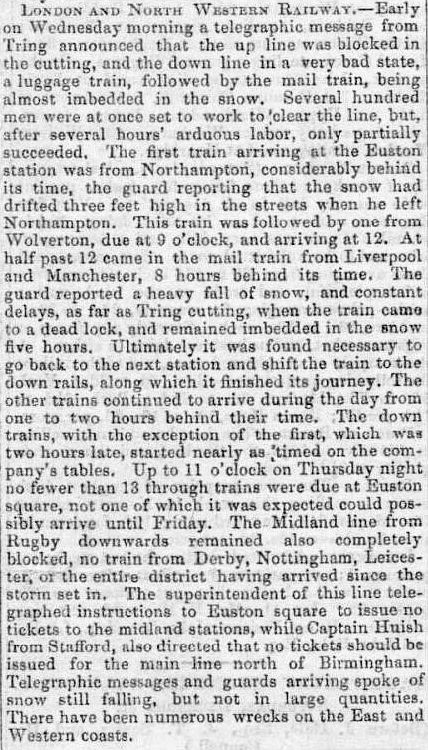

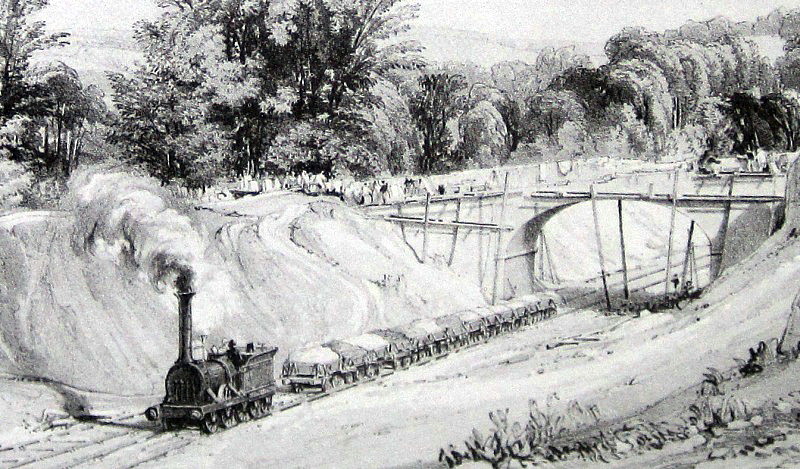

Navvies excavating a cutting near Camden on the

London & Birmingham Railway, September 1836,

by John Cooke Bourne.

Many among the local populace became so concerned by various aspects

of navvy behaviour that it was felt that something had to be done to

point out to them the error of their ways:

“. . . . in the summer of 1836,

the fearful depravity of the men working upon the railways, and the

demoralizing influence upon the surrounding population, became a

matter of public notoriety; and missions were organized by various

religious sections of the community . . . .

The object was most praiseworthy; for by no class was reformation

more radically required than by railway makers of every grade, from

gaffers to the tip-boy . . . . Thus, many well-dressed, and

doubtless well-meaning persons, obtained permission to visit the men

on the works, during meal times, with the view of imparting

religious instruction to them, and did so. The distribution of

religious tracts, and the usual machinery of proselytism, were

shortly in active operation and the men’s dinner-hour, instead of

being a period of rest and relaxation, was converted into a time for

admonition and harangue.”

‘Navvies as they used to be’, from

Household Words, Vol. XIII. (1856).

Some of this evangelizing did not fall on deaf or resentful ears, as

Berkhamsted local historian Henry Nash writes in 1890:

“Some of the men were as brutal

as tigers, while there were others who were noble, manly fellows,

and who but for their drinking propensities, would have made their

mark in the world in any pursuit of life. There were also a few

among the foremen who, in addition to their superior intelligence,

were remarkable for their sobriety and for their religious

principles. It is to these men that Berkhamsted is indebted for the

introduction of Wesleyanism into the town . . . .”

It is reasonable to suppose that the same applied to a few at Tring,

but it is likely that the majority were unmoved and persisted in

their favourite pastimes of drinking, pugilistic encounters, and dog

fighting.

Apart from the dangers inherent in a navvy’s leisure hours, most of

which stemmed from drink and the squalor in which they often lived

(contagious disease, such as smallpox, cholera, and dysentery often

struck), life in the workings was inherently dangerous in an age

when ‘health and safety’ had yet to be thought of. John Cooke

Bourne’s famous picture showing the excavation of Tring cutting

(below) illustrates just one significant risk, the ‘horse-run’. On the face

of it, using a horse to haul a man up the side of a cutting, while

he guided a barrow loaded with several hundredweights of spoil,

might seem straight forward, but when the rope gave away or the

horse panicked and bolted, the consequences could prove fatal.

However, before the spoil could be lifted up the horse-run, it was

first necessary to cut it out of the sides of the cutting. This too

could prove a dangerous operation:

“In

excavating a deep cutting, they [the navvies]

would work it as much as possible in ‘lifts’ or ‘benches,’ by which

the ground was so undermined at the bottom as to produce a large

fall of earth. The last operation was called ‘knocking the

legs from under it;’ and if the earth did not readily fall,

sharpened iron piles and bars were driven in from above to force

down the ground. From ten to fifty tons would thus be brought

away at a time; but not infrequently with one or more men buried

under the mass.”

The Quarterly Review, Volume 103

(1858).

|

|

“Upwards

of a thousand men are engaged in making

the Tring railroad cutting. Horses

attached to a windlass draw the barrows

laden with soil up inclined planks, the

labourer merely guiding the barrow.

It is very dangerous work, and

unfortunately there have been several

accidents. In Hertford Museum is

an engraving depicting the work.

It is dated June 17th 1837.”

From the

Tring Vestry Minutes for 1837. |

|

|

|

|

Horse runs, drawn by John Cooke Bourne, June 1837.

Top, at Tring Cutting. Bottom, at the Boxmoor

Embankment. |

Tunnelling was the civil engineer’s nightmare, for it was impossible

to foresee with confidence what lay beneath the surface. Subterranean streams and, worse still, pockets of quicksand and

gravel might be concealed, which, when pierced, would pour into the

workings in a torrent until the cavity it occupied was empty. Then,

no longer able to support the weight of the ground above, the cavity

would collapse, burying the workings and those unfortunate not to

have got out in time. This incident occurred during construction of the

Northchurch Tunnel to the south of Tring station:

“The soil through which we were

carrying the drift of Northchurch tunnel was of a most treacherous

character, and caused many disasters. Despite every precaution, the

earth would at times fall in, and that, too, when and where we least

expected. Thus, in the fifth week of our contract, notwithstanding

that our shoring was of extra strength and well strutted, an immense

mass of earth suddenly came down upon us. This came from the tapping

of a quicksand. One stroke of a pick did it. The vein was shelving

and the sand, finding a vent, ran like so much water into the open

drift; which was of course speedily choked up. George Hatley was at

once on the spot; and, under his directions efforts were promptly

made to clear away the sand, so that the shoring should be

re-strengthened if possible before the earth above (deprived of the

support afforded by the sand) should collapse. The most strenuous

efforts were made in vain. There came a low rumbling, like the

distant booming of artillery, then followed crashes louder than the

thunder, startling us from our labour; and, while we were hurrying

away, down came the whole mass of earth, masonry, timber, and sand,

crushing five men under it. Of these men three were dug out alive,

and removed terribly mangled – to the West Herts Infirmary; the

other two were found dead.”

‘Navvies as they used to be’, from

Household Words, Vol. XIII. (1856).

|

|

|

Northchurch Tunnel under construction.

Above:

by John Cooke Bourne, July 1837. Below: by S. C. Brees, September 1837. |

|

|

A similar incident occurred during construction of the Watford

tunnel, where the terrain is predominantly chalk, but soft chalk

interposed with gravel-filled fissures, as much as one hundred feet

deep:

“The gravel is most abundant in

the neighbourhood of Watford, covering the upper chalk which in many

places it penetrates, or in other words, the large fissures or rents

in the chalk are filled with gravel, and as this latter material is

very loose and mobile, it was the occasion of much difficulty and

danger in the excavation of the Watford tunnel; for at times, when

the miners thought they were excavating through solid chalk, they

would in a moment break into loose gravel, which would run into the

tunnel with the rapidity of water, unless the most prompt

precautions were taken.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe and Peter Lecount (1839).

Such gravel-filled fissures were cut into on several occasions, but

on the 17th July 1835, there occurred a huge inrush of gravel. Ten

of those at work in the tunnel were buried alive. So much for the

dangers of the navvies’ work.

During construction of the railway at Tring, some of the workforce

are known to have lodged in the town. What little is known about

Tring’s medieval Priory, which stood on the site of today’s Library,

come from an account by an unnamed author published in 1838 in

Railroadiana, a new history of England. After the Dissolution of

the Monasteries, the Priory building served various purposes

including, from 1718, use as Tring’s House of Correction, later

renamed the Workhouse. It was then converted into a residence for

farmer William Beal, part of which he used as a lodging house for

‘travellers of the working class’.

The old Priory building.

An 1837 extract from Tring Vestry Minutes records that:

“The old Workhouse has been

converted into a lodging house for travellers. William Beal, the

tenant, is fortunate in having just now a large number of the

excavators, or bankers as they are called, engaged in making the new

Railroad, lodging with him.”

A year later Railroadiana tells us that over 100 workers were

boarded there, all labouring on the construction of the line and the

massive cutting through the hills east of Tring. According to this

account, the lodging house was a jolly place, especially on Friday

nights when the beer flowed freely in what had once been the monks’

kitchen. A visitor of the time (clearly not an admirer of Henry

VIII, but even less an admirer of monasteries) wrote a ten-verse

poem on the subject, four of which appear below:

|

TRING PRIORY

Strange changes mark the flight of time:

Three centuries since men wondering saw,

The old abodes of cant and crime,

Abolished by a despot’s Law.

Heaven with base instruments works good,

A pregnant instance we have there;

The wretch who shed a consort’s blood,

Made tyrant priests and monks despair.

And thus perhaps it was that Tring,

Though at the time it zealots shocked,

Was cleansed by a ferocious king

From knaves who truth and virtue mocked.

We ask not who successive pass’d

Next occupants of this secure,

The fabric we behold, at last,

Came “Heaven directed to the Poor”.

Now industry on every part,

Its hand has laid in manly strife,

To render each with rustic art

Appropriate to humble life.

Where monks sung, those who guide the plough,

And those who dig until nightfall.

And in the Chapel-stable now,

A horse enjoys the only stall.

The world goes round, I see it here,

For yonder venerable pile –

Where lazy monks breathed vows austere,

Is now the scene of cheerful toil.

No more the sternly thundered doom,

Turns offending brothers pale,

But song and chorus in its room,

And mirth inspired by home-brewed ale. |

When the navvies finally completed their work, Tring perhaps

breathed a sigh of relief, although some (as recorded in Arthur

MacDonald’s notes) probably missed the additional business they

brought to the town. No doubt after their departure their old

lodging house, Tring’s Workhouse premises, needed a good tidy-up:

“William Brown – Desirable opportunity

for carpenters and builders. Directed to sell by auction on

Wednesday 30 March 1842 at one o’clock.

A large quantity of sound and very useful materials comprised in

the Old Rectory (since used as a Workhouse) at the entrance to

the town of Tring, which have recently been taken down, sorted,

and divided into convenient lots for the accommodation of

purchasers. [These included beams, joists, posts, rafters,

braces, floorboards, window frames and 1,000 cu.ft. of solid

oak.]

Catalogues will shortly be obtained from Watson’s Printing

Office, Berkhamsted.”

The Aylesbury News &

Advertiser, 26th March

1842.

――――♦――――

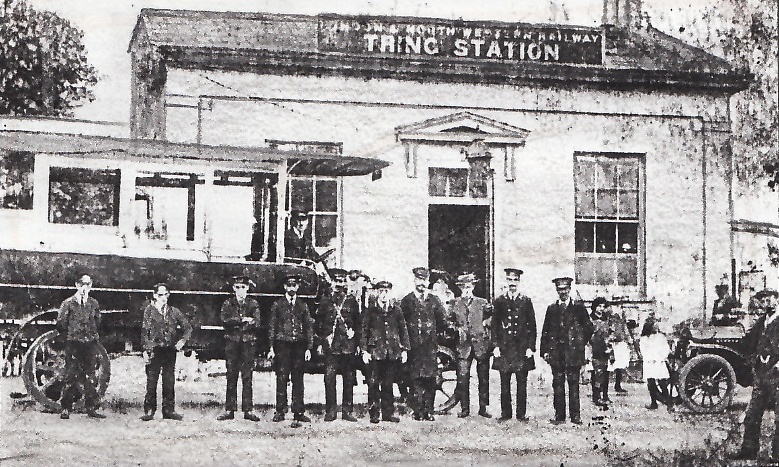

THE RAILWAY REACHES TRING |

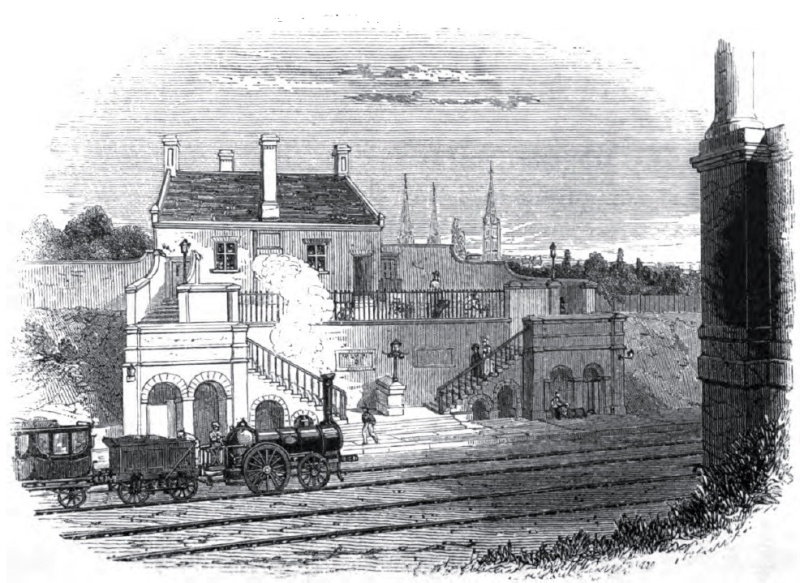

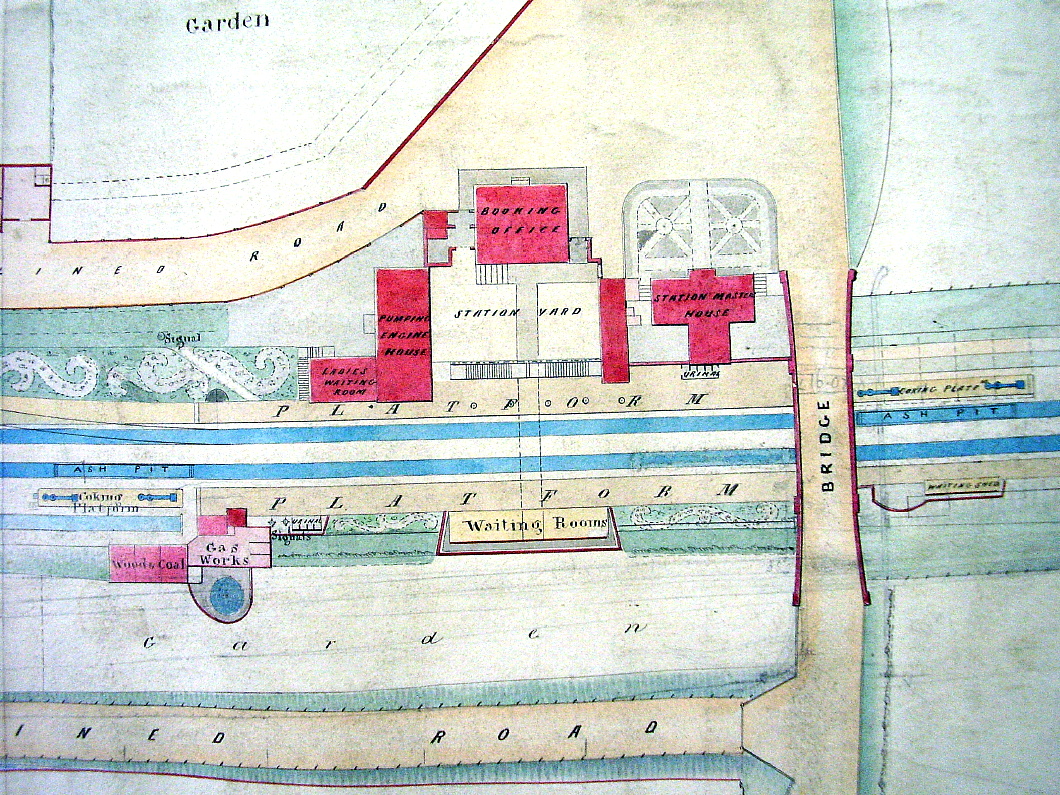

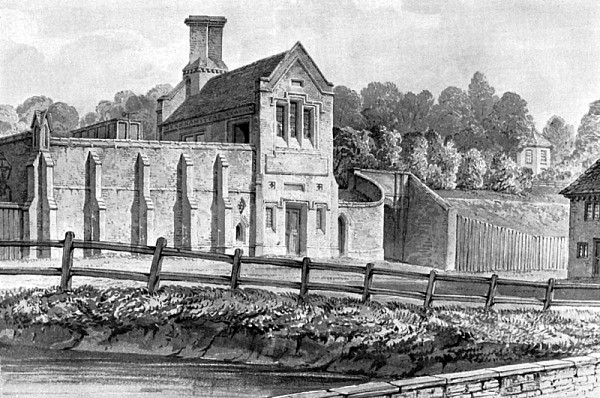

Outline drawing of Tring

Station as originally built.

The chimney was part of the gasworks that provided coal gas for

station lighting.

Our thanks go to Tom Nicholls for bringing this

drawing to our attention. It appears in

First [fourth] series of railway practice: a collection of

working plans and practical details of construction in the

public works of the most celebrated engineers by S. C. Brees

(1847).

|

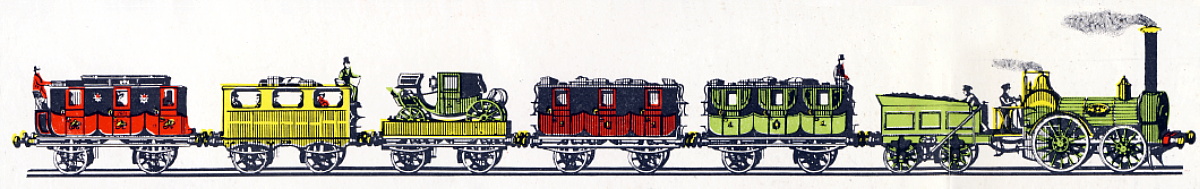

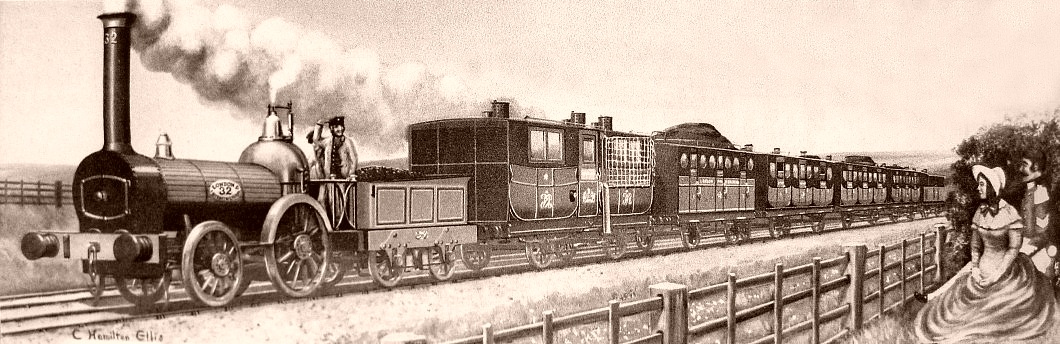

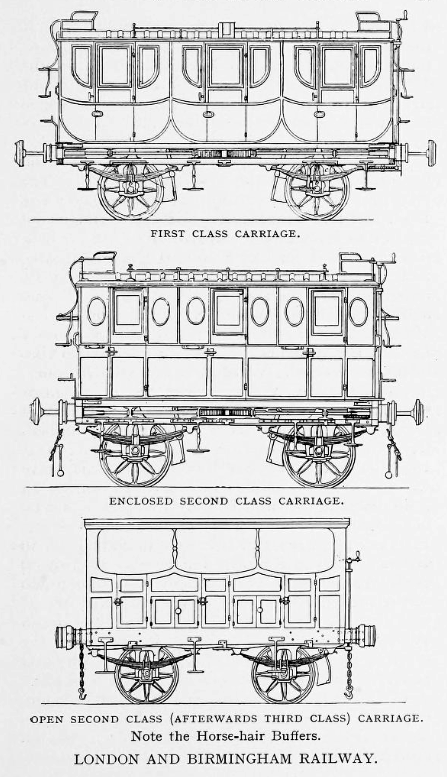

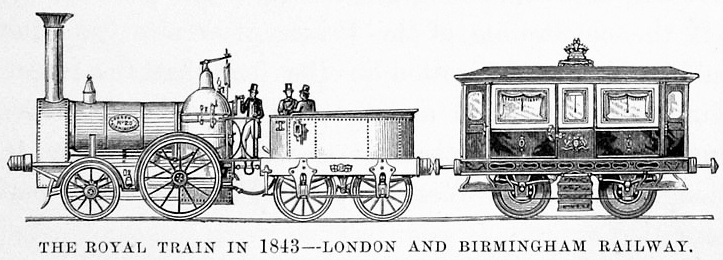

London & Birmingham Railway Bury 2-2-0

passenger locomotive No. 32 heading a mixed train.

The first carriage is a Grand Junction Railway

travelling post office, an example of which is on display at the

National Railway Museum, York. It is followed by a second-class

and then by several first-class carriages. The cylinder-like

objects projecting from the carriage roofs hold oil lamps

(it appears that second-class

passengers didn’t qualify!).

|

|

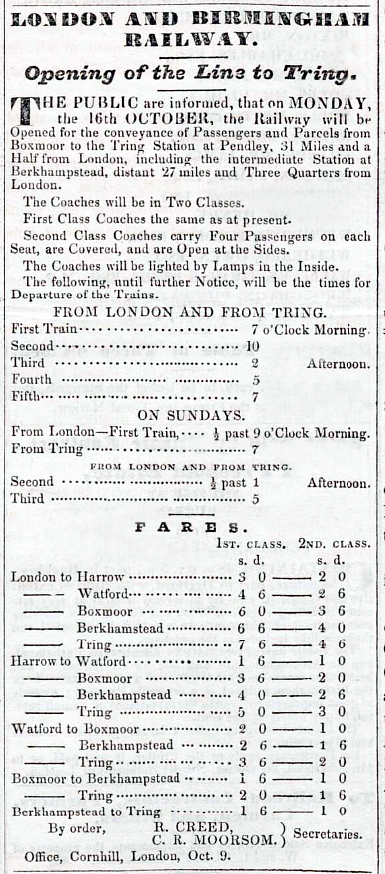

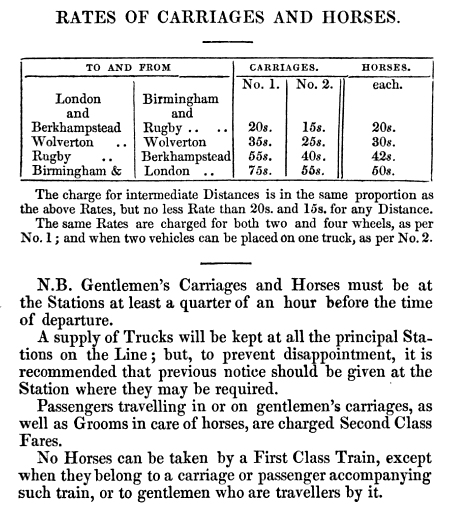

THE OPENING

The day of the opening of the line to Tring was blessed with fine

weather, and all those of importance travelled along the line. The

whole expedition, which appeared to pass without any problems, was

followed by much self-congratulation. This from the Tring Vestry Minutes:

16th October 1837 – Today the new

London & Birmingham railroad was opened as far as Tring. The

Directors and a few friends made an experimental trip in six

carriages, and the fineness of the day contributed to the pleasure

of the journey. They completed the distance to Harrow by 25 minutes

after nine, to Watford 37 minutes after nine, and to the Station at

Boxmoor by 9 minutes before ten o’clock. The train here entered on

the new line of rails.

Immediately after leaving Boxmoor Station there is an embankment of

very considerable length, at the conclusion of which there is a

short cutting of a few feet in depth, and a tunnel immediately

following the tunnel is only 300 yards in length, and the

inconvenience which has been complained of is passing through these

at the earlier part of the railroad, and the want of light therefore

was scarcely felt. An arrangement has been made with a view to

remedying this defect entirely, by the introduction of lamps into

each carriage; the regulations, it is intended, shall extend to

carriages both of the 1st and 2nd class, and the object is to be

effected by placing oil lamps in apertures in the roof of each

carriage.

The train passed through Berkhamsted Station at precisely ten

o’clock, and concluded its journey without any accident or mistake

by arriving at Tring (that is Pendley) at 10 past ten o’clock, thus

having covered the whole distance from Primrose Hill in an hour and

11 minutes.

The line of rails now laid down does not extend more than 100 yards

beyond the station, and concludes there in a deep cutting about 55

feet below the level of the earth, in soil consisting entirely of

chalk. The point at which this excavation is made is the highest

point of the whole line of the railway from London to Birmingham,

and its level is 300 feet higher than that of the station at Euston

Square, a gentle acclivity therefore, extending through the whole

distance. The journey, when the railroad is completed, will be

performed from London to Birmingham in eight and a-half-hours, but

as soon as the rails are completed the whole distance, there is

little doubt that the mails will be carried in little more than four

hours, and to Liverpool in eight and a-half, or thereabouts.

The object of the Company at present, however, is not so much to

procure speed as to secure the regular passage of their carriages,

and every train will be regularly timed on reaching its station.

Several extra engines are now in the course of building, and at the

next opening of rails, eight will be kept at all times ready to be

called into work, although three only is the number required to be

used every day.

18th August 1838 - London & Birmingham Railroad. Extract from

the Directors’ Report. The number of passengers conveyed to and from

London and Boxmoor, has exceeded all expectations. The numbers being

as follows – on 16th ult. – being 28 days from the first opening

39,855, being an average of 1,423 per day ,for which the daily

receipts average £153; during the last week, the daily number has

advanced to 1,807, the receipts being £189.

17th November 1838 – The L&B railroad is finished all through,

and a train started from Euston Grove and reached Birmingham in four

hours and a quarter.

The account in the local paper concentrated more on the aesthetic

and human aspect of the new phenomenon. The writer of a very long

report of the whole journey is breathless with admiration as he

describes the tunnels, embankments and, of course, the “steep,

precipitous trenches of chalk which shut out all prospect.”

He goes on:

“. . . . the arches of tunnels, bridges,

and viaducts, which in many cases cross the railway, the

station-houses, and the various buildings connected with the

undertaking are all built with a view to durability; they all

exhibit as much taste as could be displayed in such erections,

consistent with the strength and massiveness which are peculiarly