|

Passing near Folly Farm (where a Roman cemetery was found when the

railway was built) the line is then lost through the old cement

quarry until it picks up the line of the public footpath running

along the eastern edge of the quarry to join the present route of

the Ridgeway Path until it meets the Aldbury-Ivinghoe Road.

Here the modern Ridgeway does a dog-leg before heading on to Incombe

Hole, but the Roman road continued straight ahead, as indeed did the

footpath until diverted further north. The modern and original

routes converge onto a fine terraceway around Incombe Hole. At

the top of the hill the Roman Road does a ninety degree right turn

and heads off through the former RAF station at Edlesborough and

thence along the line of a lost footpath via Willow Farm and

Vallence End Farm to pick up a track along the foot of Dunstable

Downs.

Space does not permit the inclusion of all the details of the

evidence used to support these findings. Although some will

have been lost to subsequent development, much should remain to be

seen for those who wish to investigate, using the original

publication (which includes beautifully prepared strip maps of the

routes) as a guide.

Footnote: although the research of The Viatores was evidence

based, with conjectured lines filling the gaps between hard evidence

on or under the ground, some of their findings have subsequently

been challenged. In the case of the two routes relating to

Tring the line of Akeman Street seems pretty certain, particularly

on the Nash Mills to Fleet Marston section, with just the route

through the centre of Aylesbury perhaps less so. The Romanised

Icknield Way could be more open to challenge and it would be

interesting if anybody would like to expound further on this.

Ed - see also Roads and those in Tring

――――♦――――

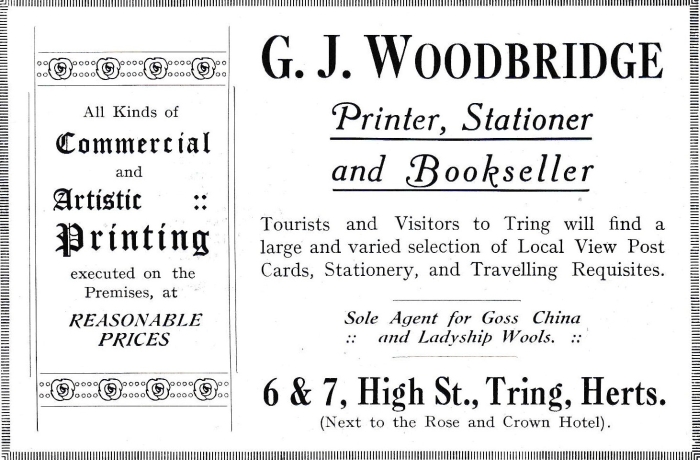

The Rose & Crown Inn, Tring

by Wendy Austin, January 2012

Although the Rose & Crown was sniffily described in 1953 by Nikolaus

Pevsner, the famous architectural historian, as “architecturally

deplorable” it is now considered a much-loved landmark of the

town of Tring, and we await with apprehension to hear of the plans

for its possible redevelopment. What we see now is an

Edwardian creation designed by Lord Rothschild’s architect, William

Huckvale, but this has not always been so.

The first mention of the Rose & Crown, which was owned by the Manor

of Tring, is said to be in 1620 when it was in the hands of Thomas

Robinson, but it is probably older than that. The original

building was largely Tudor in origin and the overall design followed

the general pattern of a complex of buildings ranging round a

sizable yard. Later on, in the early 18th century, a new

frontage was erected and old photographs show three stories, a tiled

roof, five dormer windows and an archway entrance to the yard at the

rear, the whole standing flush to the pavement with its adjacent

shops.

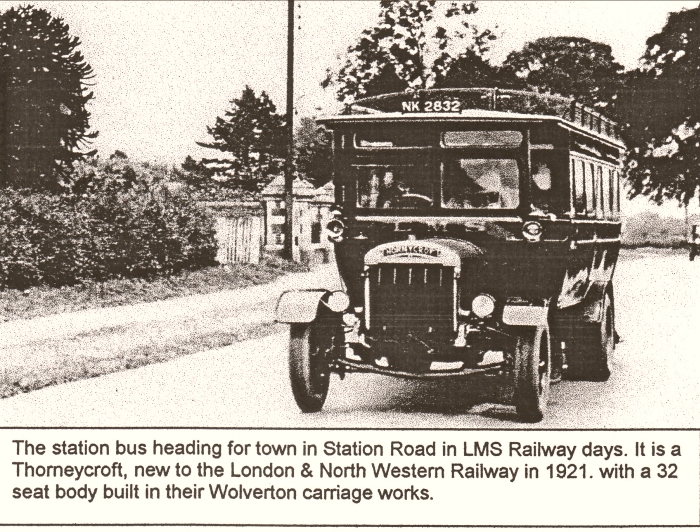

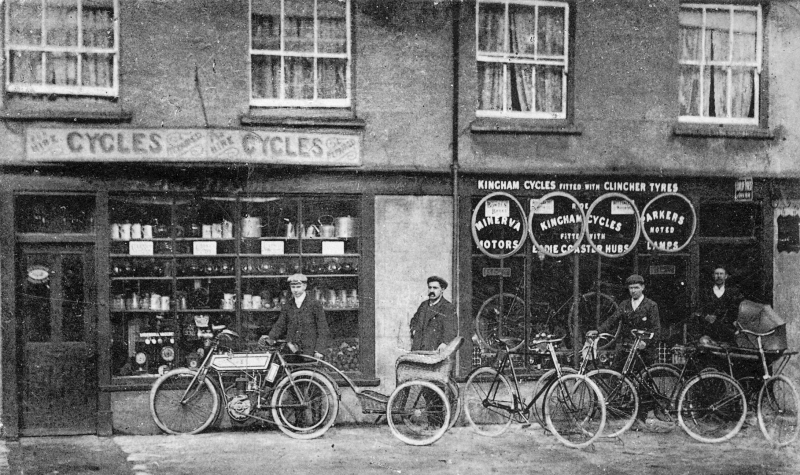

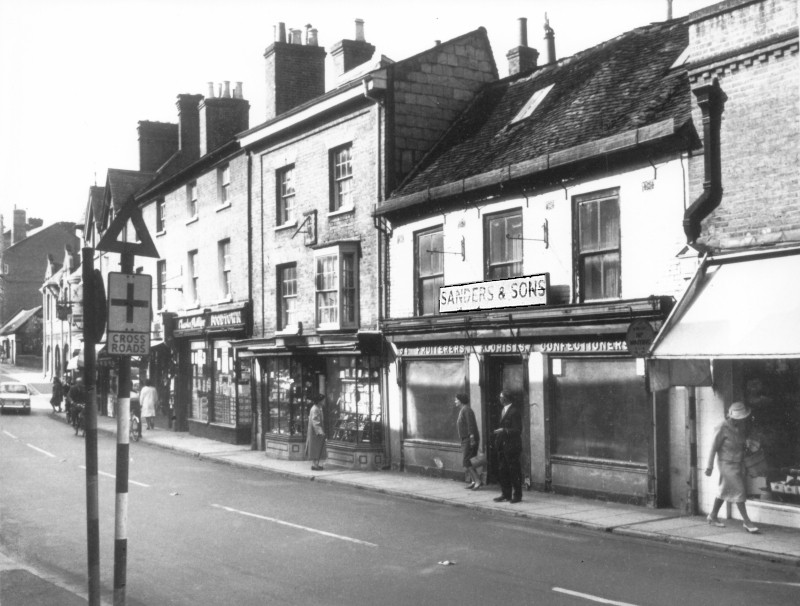

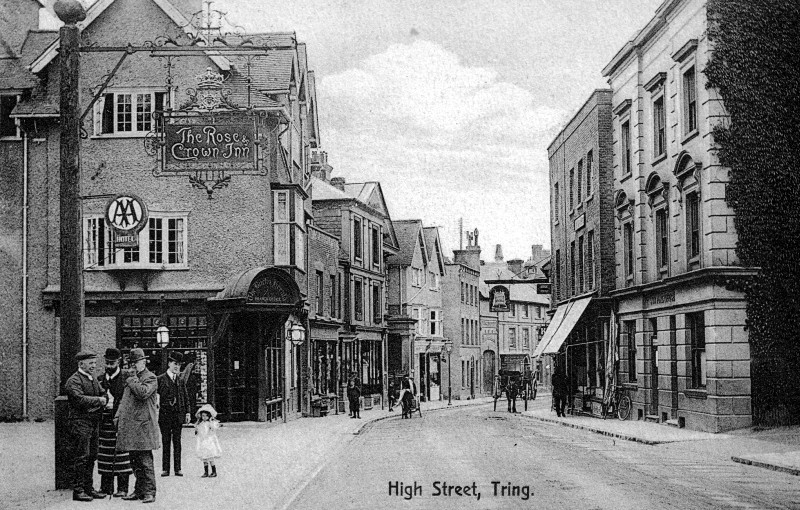

The Rose & Crown Inn

(immediate right) in the late Victorian era.

A large area of ground behind the hotel accommodated a bowling green

as well as providing a venue for fairs and circuses. An inn of

this type was considered a prestigious building and the central

focus of the town. During the next two centuries both members

of the Vestry and Excise Office made consistent use of the

facilities on offer, and an entry in the Vestry Minutes of 17

January 1711 records “William Gore Esq. [owner of Tring Park]

proposes that this Vestry be adjourned to the Rose & Crown to

consider and order all other parish affairs that shall be thought

needed”. In the 17th century the establishment was owned

by a well-known Tring family named Axtell who started to issue their

own trade tokens. [These tokens came into use because ‘the man

in the street’ had a problem - there was no official small change

for use in the market place, and innkeepers in particular were at a

disadvantage and many began to issue their own coins.] Those

from the Rose & Crown were stamped with “William Axtell. His Half

Penny” and the obverse side “1668 of Tring” and the sign

of the crowned Rose. Beer and porter were brewed on the

premises from the 17th century to about 1865, when the beer coolers

were removed to 15 Akeman Street. On William Axtell’s death an

inventory of his possessions disclose that he was a comparatively

wealthy man, the inn fully furnished on three floors; fully stocked

cellars and brewhouses; a woodhouse; a chaise barn and harness room;

and outbuildings for horses and cattle.

The 18th century saw the Golden Age of coaching and, Tring being on

a busy route to London, meant the fortunes of the Rose & Crown

increased accordingly. The Despatch, Sovereign,

and King William from Aylesbury, Leamington, and

Kidderminster called daily, and the inn’s own coach The Good

Intent ran to London three times a week. Such was the

increase in traffic that two other inns close by, the Plough and the

Bell, provided extra stabling. The advent of the railways must have

affected trade but, ever enterprising, the landlord in 1852 opened

‘the booking office of the London & North Western Railway’, and a

horse-drawn omnibus [see pictured below] carried passengers the

one-and-a-half miles to and from Tring Station.

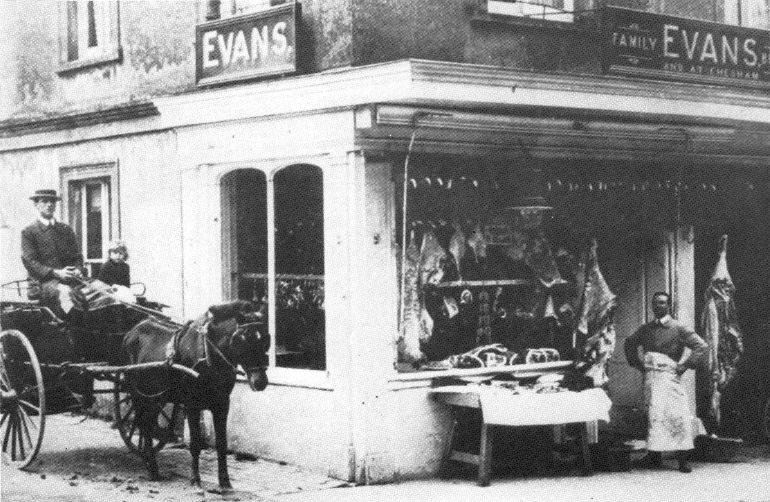

The new Rose & Crown Inn

by Tring architect William Huckvale.

The horse bus in the foreground ran a service to and from Tring

Station, 1½ miles distant.

In the Victorian age more prosperity came to Tring, and in 1904 the

townsfolk made an approach to Lord Rothschild, the Lord of the

Manor, with the suggestion that he should enhance the town with a

first-class hotel which they considered would benefit all. He

readily agreed, his action being reminiscent of the medieval habit

by which a landed lord erected additional accommodation to house the

influx of travellers whom by custom were his guests; the new hotel

had the added benefit of providing bedrooms for his personal

overflow of guests from Tring Park. When building work was

complete the finished hotel, with an imposing mock-Tudor facade well

set back from the road, was promptly handed over to the

Hertfordshire Public House Trust, an organisation promoted by the

Home Secretary, Lord Grey, to provide hotels with added sporting

facilities. And so the hotel has remained until the present

day when the need for such hotels in the centre of country towns has

almost disappeared, motorists preferring out-of-town travel lodges

with parking facilities and standard accommodation. At the

moment, we can only ‘Watch This Space’.

THE LATEST PLANS . . . . are indeed to abandon the hotel and convert

the building into apartments with, perhaps, retail outlets and

restaurants on the ground floor (Gazette 23 Nov 2011)

――――♦――――

HISTORY OF THE MEMORIAL GARDEN

by Time Amsden, January 2012.

|

|

|

Tring

Memorial Garden |

The history of Tring is closely bound up

with that of the manorial estate of Tring Park, the origins of which

pre-date the Norman invasion of 1066. Much of the land around

the centre of the town belonged to it and some indeed still does.

For the last three centuries it has centred on the Mansion.

Well into the 19th century the hamlet of Lower Dunsley could be

found at the eastern end of the town, on the edge of Tring Park and

close to the Mansion. Its only street was effectively a

southerly continuation of Brook Street. In 1872 the Tring Park

Estate was bought by the Rothschild family. Nathaniel, first

Lord Rothschild, did not wish to have a village in such proximity

and in 1885 he had most of it demolished and its residents rehoused.

Liddington’s Manor Brewery and adjacent houses at the foot of the

High Street remained until 1896 when they too were demolished and a

wall was built to enclose the land. Further up the slope stood

the Green Man Inn, which lasted until the death of the landlord,

John Woodman, in 1903. It was then demolished and the wall was

continued so that the whole area was taken into the Mansion grounds

to create a water garden. A lake was formed as a lily pond and

trees including the huge Wellingtonia were planted.

The third Lord Rothschild put much of the Estate up for sale in 1938

although the Mansion and the park were retained. During the

Second World War the Mansion was used as offices of the family

banking business and subsequently became a school. The water

garden evidently became derelict during these years.

After the war, many people in Tring

including Councillor Robert Grace were keen to create something

permanent to act as a memorial to those who had lost their lives and

a thanksgiving for those who had survived the conflict. In 1947 a

questionnaire showed that a Garden of Remembrance was the most

popular suggestion and a committee was formed to raise funds.

It was agreed that the Mansion’s water garden was the ideal place

for such a purpose and by 1950 the land had been transferred into

the ownership of Tring Urban District Council. The ground was

cleared, the lake bed resurfaced and simple planting carried out.

An opening was made in the wall at the point where it met the 1711

wall across the Mansion vista. Gates were made by Bushell

Brothers’ boatyard at New Mill and the archway reading “Memorial

Garden” was made by Hampshire and Oakley of Chapel Street.

The Garden was unveiled in June 1953 to coincide with the Queen’s

coronation and dedicated by the vicar of Tring, the Reverend Lowdell.

In 1973 Tring Urban District was merged into the newly formed

Dacorum District and most of its properties, including the Memorial

Garden, were transferred to the new council. Simultaneously, Tring

Town Council was formed with specific responsibilities such as

allotments and other matters unique to the parish.

By the mid-1980s the Garden again presented a forlorn appearance.

People were reluctant to go there because the planting had become

dense and gloomy. A scheme for the improvement of Tring High

Street, drawn up by Derek Rogers Associates and promoted by Tring

Town Council in 1987, recommended that trees should be thinned and

the entrance reconsidered. Dacorum Borough Council agreed to

undertake this work and many trees, especially yews, were removed.

A length of wall was taken down, a new planting bed was created

alongside the High Street and the gateway repositioned, with new

gates made to replicate the old ones. The work was carried out

in 1989-90 with the restored Memorial Garden unveiled by the Mayor

of Dacorum in June 1990.

The same report observed that the self-seeded trees behind the

adjoining vista wall were overgrown and detracted from the setting

of the Mansion. The Arts Educational School removed the trees,

bringing the house back into view. The fourth Lord Rothschild

presented Tring Town Council with a strip of land in front of the

wall and this was then paved and bollarded, greatly enhancing the

appearance of this part of the town.

In 2001 the lake had to be drained and the fish evacuated when it

was found necessary to repair a crack in the concrete base. Members

of the Tring branch of the Royal British Legion attended a reopening

ceremony, and presented plaques listing the names of those men from

the town killed in World War II. These are mounted on the brick

gate-pillars at the entrance to the garden. Further work was carried

out to the lake in 2011, giving it a more natural appearance and

installing a fountain.

Tim Amsden,

with acknowledgments to Wendy Austin and Mike Bass

Note:

Dacorum Borough Council is hoping to achieve Green Flag status for

the Gardens, which will be officially ‘re-opened’ sometime in March.

The overall plan is to create more flower beds, enhance the area

with new trees, and remove some of the overgrown bushes and trees.

The Green Flag Award® scheme is the benchmark national standard for

parks and green spaces in the UK. It was first launched in

1996 to recognise and reward the best green spaces in the country.

――――♦――――

TRING’S RAILWAY SERVICE IN 1895

by John Savage, March 2012.

Today Tring station enjoys a more frequent train service (4 per hour

off-peak, and even 2 per hour for most of Sundays) than at any time

during its 174 year history, so it is interesting to compare this

with the service provided by the London & North Western Railway in

1895, as seen in Bradshaw’s Guide.

There were then 12 trains a day to Euston on weekdays (with 14 from

Euston of which one required a change at Watford) and 5 (3 from

Euston) on Sundays. Additionally there was a late night

facility from London on Tuesdays when the midnight train to Glasgow

stopped at Tring, to set down only, on informing the guard at

Willesden. Fascinatingly, this train made a different request

stop each night; Leighton (as the station was then called, being

renamed Leighton Buzzard on 1 July 1911) on Mondays, Tring on

Tuesdays, Boxmoor on Wednesdays, Berkhamsted on Thursdays, Bletchley

on Fridays and Kings Langley and Wolverton on Saturdays.

Another interesting addition to the service was the 5.00pm Euston to

Wolverhampton train, scheduled to run non-stop from Watford Junction

to Leighton, but which would stop at Tring to set down First Class

passengers only on notification to the guard at Willesden!

Business travel was quite well provided for with trains to London at

7.36am, 8.43am, 8.57am and 9.30am with a similar provision in the

evening. At other times the frequency was sparse with gaps of

over two hours between trains. Considering the relatively few

trains, rather bizarrely two of the trains to London ran within 5

minutes of each other (at 6.58pm and 7.03pm).

Compared to today where trains generally take 35 or 42 minutes (with

the fastest at 30 minutes) between Tring and Euston, the times in

1895 were considerably slower. Most trains took about an hour

and a quarter, with the slowest all-stations taking almost one and a

half hours. However, some of the trains at business times were

quicker, making the journey in just under an hour.

The trains serving Tring went to and from quite a diverse set of

places. On weekdays the trains to London originated from

Bletchley (x4) and one each from Liverpool, Stafford, Nuneaton,

Rugby, Northampton, Leighton, Cheddington and Tring. From

London the Tring trains went to Bletchley (x7), Tring (x2),

Cheddington (from Watford), Leighton, Northampton (x2) and

Wolverhampton. On Sundays the trains to London originated from

Bletchley (x2), Wolverhampton (x2) and Birmingham. From London

the meagre three trains went to Rugby (x2) and Leighton. I

should mention that this information is as best I can deduce because

in those days generally the timetable confusingly did not

differentiate between through and connecting services.

We will now look at the stations between Tring and Euston in 1895

and how they have changed since:

BERKHAMSTED (no change)

BOXMOOR (variously and erratically later Boxmoor & Hemel Hempstead,

Boxmoor for Hemel Hempstead, Hemel Hempstead & Boxmoor and

Hempstead; settling on Hemel Hempstead 1963/4)

KINGS LANGLEY (the intermediate Apsley was a late addition, opened

by the LMS on 26 September 1938)

WATFORD JUNCTION (no change)

BUSHEY (renamed Bushey & Oxhey 1 Dec. 1912 and back to Bushey 6 May

1974)

PINNER (renamed Pinner & Hatch End on 1 February 1897, Hatch End for

Pinner on 1 February 1920 and Hatch End on 11 June 1956. Now

only served by Euston- Watford local trains). The remains of

the old main line platform are still visible from the train.

HARROW (renamed Harrow & Wealdstone 1 May 1897)

SUDBURY & WEMBLEY (renamed Wembley for Sudbury 1 November 1910 and

Wembley Central 5 July 1948)

WILLESDEN JUNCTION (main line platforms closed 3 December 1962)

QUEENS PARK (no change)

KILBURN & MAIDA VALE (Closed 1 January 1917, reopened on same site

as Kilburn High Road 1 August 1923. Now only served by Euston-

Watford local trains)

LOUDOUN ROAD (Closed 1 January 1917). Later South Hampstead opened

at same location; remains of old station on main line still visible

from the train.

CHALK FARM (Closed 10 May 1915).

All of the then intermediate stations were served by some trains

to/from Tring, indeed some stopped at all of them! Willesden

Junction was then an important interchange with the radial North

London Line to Broad Street (for the City), Kensington, Clapham

Junction and through trains to the District Railway; almost all

trains, including long distance expresses, called there.

Fares in 1895 were: Tring-Euston (single) 5 shillings First Class

and 3s 4d Second Class. Third Class (known as “Parliamentary”

or “Gov” in the timetable because regulated by statute to 1d per

mile) was 2s 7½d,

exactly based on the 31½

miles (rounded down to the nearest half mile) distance. In the

reverse of today, in the early days of railways far more First Class

tickets were issued than any others, with Third Class trailing very

much behind. No doubt the poor and working classes neither had

the need nor means to travel.

In this time before bus services the railway would also have been

the means of travel from Tring to Aylesbury, by changing at

Cheddington (originally Aylesbury Junction) onto the branch line

(the world’s first branch line, incidentally) from there.

Indeed in earlier days there is evidence of through trains from

Tring to Aylesbury. The intermediate station on the branch

line at Marston Gate (on the Long Marston-Wingrave road) was usually

shown as a “signal” stop, i.e. by informing the guard if you wished

to get off or signalling the train to stop if you wished to board.

Finally, a lovely snippet from the timetable. The “Irish Boat

Express”, 9.30am Euston to Holyhead which ran non-stop from Watford

Junction to Northampton, conveyed a slip-coach, when required, for

Leighton during the Hunting Season. (A slip-coach was a

carriage attached to the end of a train, cast loose as the train

approached the due station, and brought to a halt by a guard with a

hand brake). To cater for such hunting parties to return from

Leighton the afternoon “Birmingham Express” would “stop by

signal at Leighton to take up Hunting Parties during the Season.”

――――♦――――

THE POLISH CAMP AT MARSWORTH

1948-1958

by Sandra Costello, July2013.

Polish servicemen and World War II

The heroic part played by Polish airmen, soldiers and sailors on the

side of the Allies during World War II is well known. However

from the early days of the War, Western Poland was occupied by

Germany and Eastern Poland by Russia. When peace returned to

Europe in 1945 all Poland was behind the Iron Curtain.

With the war over, most Polish servicemen did not want to return to

what they regarded as occupied Poland. One of the options

offered to them was assistance to start a new life with their

families in Britain. Many took advantage of this and as a

result some 30,000 Polish people came to live in Britain, where some

40 hostels were made available to house them in camps left empty by

the running down of British forces. Life was very difficult

for them: many had been forced for years to live in communal

conditions, and among them were many children who had never

experienced normal life. Those who came to Britain had to try

to assume again the responsibilities of independent people, but in a

strange land and with a different language.

The Polish Hostel at Marsworth

Some 900 Polish people, including whole families, came to Marsworth

in 1948, and were first accommodated in huts on the perimeter of

Cheddington Airfield at the end of Church Farm Lane. After

about five years the camp was relocated to a bigger and better site

once used by the RAF, then by the US Air Force, off Long Marston

Road. Food was cooked in central kitchens and eaten in

communal dining halls for the first two or three years, until

cooking stoves could be installed in the accommodation occupied by

each family. The huts did not have running water, and internal

partitions were few.

Affect on Marsworth

To begin with the village of Marsworth, with a population of only

316, objected to this huge influx. However according to a

report in the Bucks Advertiser of 1949, “Already the

people of Marsworth village have accepted them as ordinary families”

and the Polish people “now live happily in Marsworth”.

With the number of Poles exceeding the population of Marsworth by

nearly three times, the small local school did not have room for the

extra children. A school was therefore set up at the hostel

where virtually everyone, irrespective of age, attended classes to

learn English. One of the huts was converted to a chapel and

many community activities were carried on, including football,

volleyball, a youth club, women’s circle, and a Polish

ex-servicemen’s association.

The people of Marsworth were able to mix with the Polish community

by attending the dances, cinema and other entertainments held at the

hostel. This was a great help as the Poles were keen to learn

how British people lived.

The end of the camp

In the 1950s those at the hostel were eager for homes of their own

and a more normal life as part of the British community. In

their preparations for moving out of the hostel they learned a lot

from local people who helped them to gain confidence and make

contacts. Those who were able to work found jobs and this was

made easier when some employers provided transport in a variety of

vehicles from and to the Hostel. Contacts at work speeded up

the learning of English as well as improving knowledge of life

outside the Hostel.

The numbers living at the camp reduced steadily as families found

work and homes elsewhere, with the largest numbers leaving in the

first couple of years. In 1957 the Marsworth school roll

included the names of 25 Polish children, indicating that the school

at the hostel had closed. By the late 1950s numbers had

dwindled sufficiently for the few remaining to be accommodated

elsewhere, and the camp to be closed. The field that housed it

has since been returned to agriculture and all that remains is some

concrete. The only real legacy of the Polish presence in

Marsworth is some 15 graves in the churchyard of All Saints Church.

Those buried in the churchyard were mostly drowned — they swam in

the reservoirs, which were not allowed, but they could not read the

warning notices. Whenever there was a Polish funeral, all the

Poles from the camp turned out and the procession would stretch all

the way from the Camp to the Church.

For the Polish people, Marsworth was a pleasant village where they

were able to find security and become independent persons again, and

that gave assistance when it was needed after the horrors of war.

Polish return

In September 2008, Stanislaw Jakubas, now an Assistant Professor at

Krakow Academy of Fine Arts, paid a return visit to Marsworth.

He was born in 1948 at Bedford Hospital; his parents were then

living at the first of the two Polish camps — ‘Site Twelve’,

situated opposite Church Farm House. He recollected the

various ‘barracks’, but his memory was sketchy as he was very young.

He also remembered attending kindergarten at a building in Church

Farm Lane opposite the airfield (now long since returned to

pasture). He especially remembered playing with another young

boy, Ross Miller of Church Farm.

After about five years the Polish people were relocated to a bigger

and better camp situated near Bluebells, on a field bordered by a

concrete road leading towards Wilstone. He recollected the

layout of this camp, with its coal store at the entrance, the

various barrack buildings, the laundry and chapel. He attended

Marsworth School, and also remembered a large building then situated

opposite Lower End garage where concerts, etc. had been held on a

stage.

In 1956 Stanislaw went with his family to live in Canada. He

didn’t want to lose touch with his friend Ross, so he sent him a

letter in a bottle which he threw overboard. The bottle was

picked up 10 months later on the Irish coast. Apparently this

story made the BBC News and was reported widely in the local press.

‘Site 12’ was down a long lane close to the airfield and near a

yellowish brick farmhouse with several barns. The main site

was close to a canal. If you go to HP23 4NF on Google Earth

you should be able to see the latter site from the air. There

is nothing there now as all the buildings have been cleared for

farming.

――――♦――――

ANOTHER 100th ANNIVERSARY (not WW1)

by John Savage

1st March marked the 100th anniversary of Tring’s first motor bus

service on which date in 1914 the London & North Western Railway

took over the station route.

The station bus service, the earliest in Tring, started when the

station opened in 1837. It was to be over 80 years before any

other buses served the town. The horse buses were operated by

local people and by 1899 we know that the service was terminating in

the back streets at the “King’s Arms” probably where the

horses were kept. Change came in 1903 when the Tring Omnibus

Company was formed to take over the service; all the directors and

shareholders were local people. A new omnibus was purchased

for £99.15s and £300 compensation paid to the previous operator, C &

J M Buckle. Lord Rothschild soon joined the board, suggesting

that his financial support was already necessary. By 1906 the

company was in financial difficulties, and in 1907 resolved to go

into voluntary liquidation.

An unlikely rescuer came in the form of the Home Counties Public

Trust House (a forerunner of Trust House and Trust House Forte) who

owned “The Rose & Crown” and who took over the service,

terminating at the “Britannia” PH. In 1911 they

proposed extending the service to the Cemetery Gates in Aylesbury

Road, but it is not clear whether this actually happened; certainly

in 1913 it was curtailed at the “Rose & Crown” from the “Britannia”.

In 1914 the HCPHT gave notice that they were discontinuing the

service as they too had been unable to make it pay. Tring

Urban District Council requested that the London & North Western

Railway take on the service, which they duly did. The new

motor bus service terminated at the Cemetery Gates and provided a “frequent”

service between 8.00am and 9.30pm. With the grouping of the

railways in 1923 the service passed to the London Midland & Scottish

Railway which, in 1928, extended some journeys (on Fridays and

Saturdays) to Aldbury. By 1929 the service had again been

curtailed at the “Britannia”. Books of 24 or 50 tickets

could be bought from the station at a discount, and there were also

monthly season tickets.

With the imminent creation of the London Passenger Transport Board

the LMS sold out its local bus services to London General Country

Services in April 1933. LGCS changed the terminus to

Beaconsfield Road and gave it the route number 317. In July

1933 it thus passed to the LPTB (London Transport) who soon

renumbered it (by January 1934) to the familiar 387. Later in

1934 they gave the Tring Station to Aldbury section (still Fridays

and Saturdays only) a separate number, 387A, although this silliness

ceased in 1935 with all the service again becoming 387.

The more recent history is another story; other than to say that,

apart from an interregnum from 1985 to 2002 when the route was

numbered 27, it has stayed as the 387 to this day.

――――♦――――

THE TRING GAS LIGHT & COKE COMPANY

by Ian Petticrew, July 2016.

The development of gas lighting in the 19th century had a dramatic

impact on people’s domestic and working lives. Gas provided a

far more efficient and economic form of lighting than the candles

and oil lamps that preceded it.

In 1812, the London and Westminster Gas Light & Coke Company became

the first public gas manufacturing utility and it proceeded to

spread gas lighting through London’s poorly lit streets, an

innovation that soon became popular elsewhere. The first town

in our area to acquire a gasworks was Aylesbury. In 1834 the

Aylesbury Gas Company began operations on a site located at Hale

Leys. Gas became available at Hemel Hempstead in 1835 when a

gasworks was opened in Bury Road. In 1849, the Great

Berkhamsted Gas Light & Coke Co. was set up to provide street

lighting; and then . . . .

TO THE INHABITANTS OF TRING.

A public meeting will be held on Thursday evening next, March 14th

1850, at the Commercial Hall at 7 o’clock to take into consideration

the report of Mr. Atkins on the practicability of introducing Gas

into the Town.

The advertised meeting was well attended and ended with the

unanimous decision being taken “That in the opinion of this

meeting it is desirable that gas should be introduced into the Town

of Tring”. A committee was formed comprising William

Brown, Frederick Butcher, H. S. Rowbotham, Henry Faithfull and

Alexander Parkes to “ascertain the practicability of establishing

a Gas Company in this Town.” It was decided that the

prospective company would require capital of £2,000, to be raised in

£10 shares, and that each director would need to hold at least five

shares to qualify.

At this stage a site for the Gasworks had yet to be found, so the

directors took Atkins on a conducted tour of the Town during which a

former gravel pit on Brook Street was identified as a suitable

location. The gravel pit was the property of David Evans,

owner of the Silk Mill, who agreed to sell part of it to the Company

for £60.

Construction went ahead and gas was first released into the mains in

September 1850 . . .

On Wednesday last, the town of Tring was all in a bustle, in

consequence of that being the night which was fixed upon by Mr. T.

Atkins, of Oxford, the contractor, to light the gas for the first

time. Great preparations were made to celebrate the event, and

an immense concourse of people was present. The men who had

been employed at the works were sumptuously regaled with a supper,

at the Green Man Inn.

In gasworks of the time coal provided the raw material.

Wagonloads were delivered by rail to Tring Station and carted to the

gasworks by local hauliers. Gas was then extracted by baking

the coal in enclosed ovens called ‘retorts’ in which the coal was

starved of oxygen to prevent it burning. This process produced

a crude gas that contained unwanted substances, such as sulphur,

that had to be removed by purification before the gas could be

released into the mains. Other by-products were useful and

could be sold, including coke and coal tar - when motor vehicles

arrived and measures had to be taken to seal road surfaces to

prevent dust and mud being thrown up by this new faster-moving

traffic, coal tar mixed with granite chippings became a popular

road-surfacing material.

For over a century coal gas was manufactured at the Brook Street

gasworks on the site now being developed as a block of luxury flats

(old gasworks sites are generally heavily contaminated -

decontamination of the Tring site cost £400,000 before building

could begin). Many local businessmen served as the Company’s

directors until, in 1930, the Company was sold to outside interests.

In 1948 the Tring Gas Company (as it had become) was nationalised

and incorporated into the Southern Gas Board. Then, in April 1957

the following notice appeared in The Bucks Herald . . . .

Tring gas now comes from Oxford. For 105 years the 5,000 people

of Tring have had a gasworks, but Southern Gas now pipe from Oxford.

By then coal gas had a limited life. In 1967 the first natural

gas arrived from the North Sea and over the next 10 years British

Gas carried out a massive programme to convert gas appliances to

burn this new type of fuel. Tring converted to natural gas in

January 1969. For some years a large gasholder marked the site

of the Tring gasworks, but now all that remains is the former

gasworks manager’s house (by local architect William Huckvale).

GASLIGHT

COMES TO TRING.

――――♦――――

TRING ATTRACTS WEALTHY RESIDENTS

by Wendy Austin, September 2016.

Originally most men of influence in the City of London lived near

their workplace, but as they grew wealthier, they started to

consider more congenial surroundings for their families. The

age of commuting was born, mainly with a north-westerly trend, as

the lack of river bridges delayed development southwards. In

spite of the discomforts of coach travel at that time, these men of

substance began to buy country estates when a deer park was a highly

desirable status symbol. In 1702, Henry Guy’s property, the

Tring Park estate, became available and was purchased by Sir William

Gore.

Both figuratively and literally Sir William was very much a bigwig

in the City, for in 1692 he had been knighted at The Guildhall by

William III. In the same year that saw the arrival in Tring of

Sir William and his lady, he achieved the supreme appointment of

Lord Mayor of London and, to mark this event, the traditional

splendid procession and pageant had progressed through the streets

of the City. The gilded coach was proceeded by elaborate

horse-drawn floats carrying figures from mythology depicting finance

and enterprise. Among his business concerns Sir William

numbered a place on the committee of the East India Company, and was

a founder member of the Bank of England, his only setback being a

failed attempt to be elected as Tory candidate for the City of

London.

Daniel Defoe, passing through Tring on his travels, reported “at

Tring is a most delicious house, built å la moderne ” which

referred to the mansion purchased by Sir William. It had been

erected in the 1680s to a plain but pleasing design, said to be that

of Sir Christopher Wren. Surrounded by a small deer park, it

had gardens described as “of unusual form and beauty”.

Sir William’s healthy income soon allowed him to buy another 300

acres to add to his estate. He and Lady Gore, together with

their eight surviving children, presumably settled in happily and

started to enjoy the wide vistas of parkland, with a backdrop of the

beautiful beech woods along the Chiltern escarpment.

As we all know, even when one finds the ideal property, there is

always a snag — at the Tring Park mansion the problem was traffic.

The main road through the town at that time followed a route to the

south of the house, passing in front of the windows of the chief

reception rooms. The elegant walnut furniture and Delft china

probably rattled as coaches and wagons rumbled by and, an even worse

horror, the general populace could catch a glimpse of the family

dining. This state of affairs was swiftly rectified when Sir

William’s son inherited the estate, and petitioned to move and sink

the level of the road to the other side of the house. As this

then became the route of Tring High Street, today’s traffic

congestion in the town can be blamed firmly on William Gore junior.

He had not waited too long to gain his inheritance, for by 1707 both

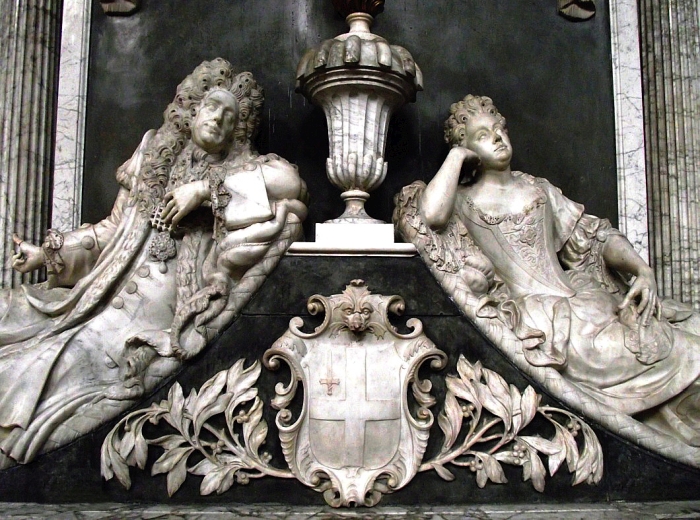

parents were dead. Ever a dutiful son, he erected in Tring

Church an enormous memorial. Their life-sized marble effigies

are attired in the height of early-18th century finery, Sir William

wearing an immense and elaborate periwig. Accompanied by a

graceful gesture of his hand, he is discoursing to his wife, who

stares stonily ahead into space. Having now heard her

husband’s stories for almost 300 years, she is probably entitled to

look a trifle bored (below).

The Gore Memorial,

Tring Parish Church

In due course, Tring was also chosen for his retirement home by an

eminent banker. In 1931 Sir Gordon Nairne did not expect to

own anything so grand as a mansion in a park, for his origins were

modest, and his success in life had been built upon his own ability,

application, and integrity. He was a son of Scotland, born in

Castle Douglas and, after working in Glasgow, he entered the Bank of

England in 1880, and served there for fifty years until his

retirement. His talent for financial management was recognised

at the comparatively early age of 41 when he was appointed Chief

Cashier. Perhaps Gordon then allowed his grave features a

twitch of a smile of pride on the first occasion that he saw bank

notes bearing his own signature. The novelty must have worn

off, for he held the post for sixteen years, and part of this time

covered the critical period of the Great War. This was

especially difficult for banking as the Treasury issued currency

notes through the Bank of England in almost unlimited amounts, with

inevitable inflationary effects. The Bank was in safe hands

however, and Gordon Nairne received his deserved reward. In

1917 he was created a baronet, and the following year appointed to

the newly-created post of Comptroller. A Directorship followed

in 1925, Sir Gordon being the first member of staff to achieve this

position. His wise guidance was appreciated elsewhere too, as

he was honoured by other countries, including France, Belgium and

Japan.

When he left the Bank in 1931 he and Lady Nairne sought a pleasant

home in the country. Their choice fell on The Furlong, a large

house of unremarkable design in Park Road, built in the late

Victorian period by a wealthy vicar of Tring. The couple

entered into the life of the town, dutifully undertaking the worthy

sort of community activities that were expected from people in their

position. Sir Gordon remained a busy man, serving as a

Governor of the BBC, and as one of His Majesty’s Lieutenants for the

City of London; he also found time for his favourite pastime of

horse-riding. After a happy retirement he died in 1945 aged

84, and was buried in his family’s grave at Putney Vale cemetery.

Later, The Furlong became an annexe of a convent school, and was

then demolished in the 1980s to be rebuilt as retirement apartments.

For the time being, Tring’s ‘moneymen’ have departed. It

remains to be seen whether the twenty-first century will see yet

another eminent man of finance wishing to spend his annual bonus on

an expensive property and put down roots in our town.

――――♦――――

THE OTHER ALBERT HALL

by Wendy Austin, July 2018.

Forget the dominating and magnificent edifice on the south side of

Kensington Gore in London, as many and varied were the structures

erected to the memory of Albert, the Prince Consort. Some

people may not know that one such existed in Tring; unsurprisingly,

it can be found in Albert Street.

Its origins are obscure, but by the 1880s local newspaper accounts

show the hall served a useful purpose as a venue for various events

and meetings. For example, the Mothers’ Union gathered in the

hall; the Church Lads’ Brigade used it for band practice; William

Brown, the land agent and auctioneer, held sales there; technical

classes were run by Dr Spurway, who lectured on sanitation, nursing,

and first-aid, all of which were described as “useful to the

wives and daughters of working men”.

It also served as a useful space in which to hold bazaars and

rummage sales. At that time, the latter were obviously a

novelty, as one account shows it was necessary to explain to readers

exactly what a ‘rummage sale’ was. The account reads:

“ .... .. on Saturday 25th ult, the Albert Hall presented a

remarkable scene. At the invitation of the Vicar, the

parishioners had ‘rummaged out’ the contents of their attics,

storerooms, closets and dark corners and had collected what had been

cast aside as worn-out and useless, to be sent to the Hall, to be

sold for the benefit of the fund from which the little expenses of

the Parish Charities are defrayed. On the previous day, the

donkey cart of Cogger, the sexton, perambulated the town going from

house to house collecting the things that had been turned out for

the sale . . . . . . . .”

The Albert Hall also became the central point for the serving of

what were known as ‘Penny Dinners’. Organised by Tring

District Visiting, a national C. of E. charity organisation,

cardboard tickets (later metal discs) were distributed to the more

deserving children of the town by their school teachers, these

tokens to be exchanged for a nourishing meal. The food and

money was donated by well-off citizens of the town, the subscription

list being headed, of course, by Lord Rothschild. According to

the late Ron Kitchener, the meals were plain but sustaining, e.g.

pea soup, Irish stew and rice or jam pudding, he goes on to quote

that in the first year of the scheme, 1,307 tokens were issued.

By the end of the century many other general gathering places had

sprung up in Tring, and possibly the hall became under-used, as the

premises were then shared with Henry Stevens, a town councillor who

owned a shoe shop at No.15 High Street. He set up a small

factory in the Albert Hall which he called ‘The Shoe Mart’ and

advertised his wares for sale in The Tring Gazette; examples

of his boots and shoes were also exhibited with great pride at Tring

Agricultural Show and other such events. This operation was

closed down and sold in 1899.

The former Salvation

Army hall in Albert Street,

February 2014

A year later the premises became a meeting place for members of

Tring Salvation Army who, up until then, had worshipped in what was

described as “a draughty uncomfortable little carpenter’s shop”;

the Albert Hall then became known as The Barracks. What

happened over the next 20 years is unclear, as an advertisement of

1924 states that the premises were owned by Messrs. Rodwell & Sons

who offered it for auction citing that it was ‘a good site for a

small factory or similar’, but even so it failed to attract a

purchaser. But a little later the premises were acquired by

the Salvation Army, and approval for erection of a new building, at

an estimated cost of £1,550, on the site of the Albert Hall was

granted in July 1926, with demolition a few months later. The

following year The War Cry was able to report on the opening

ceremony of the new Citadel:

“ .... .. for some years the comrades of Tring have laboured

under the disadvantage of having no permanent building in which to

hold their meetings. This came to an end last Saturday when,

amid scenes of enthusiasm mingled with praise and gratitude to God,

they entered their new Citadel .........”

There was good reason for ‘enthusiasm’ as the Tring branch of the

Salvation Army had waited 38 years before attaining its own meeting

place. Major modernisation of the premises were carried out in

2001, but the history of the Salvation Army in the town came to an

end in 2014 when the building then became an arts and education

centre. It now serves as Tring’s Yoga Studio.

――――♦――――

THE TRING AND AYLESBURY TRAMWAY

that might have been,

by Ian Petticrew, September 2018.

The street tramway arrived in Britain in 1860 when American

entrepreneur George Train opened a short line at Birkenhead.

It was not long before most of Britain’s cities and towns of any

size had trams.

Motive power was at first provided by horses, but in an age of steam

attempts were soon made to use it to replace animals. The

small steam ‘tram engines’ that resulted were expensive to run and

maintain, so when more compact and efficient electric traction

became feasible in the 1890s it quickly replaced steam.

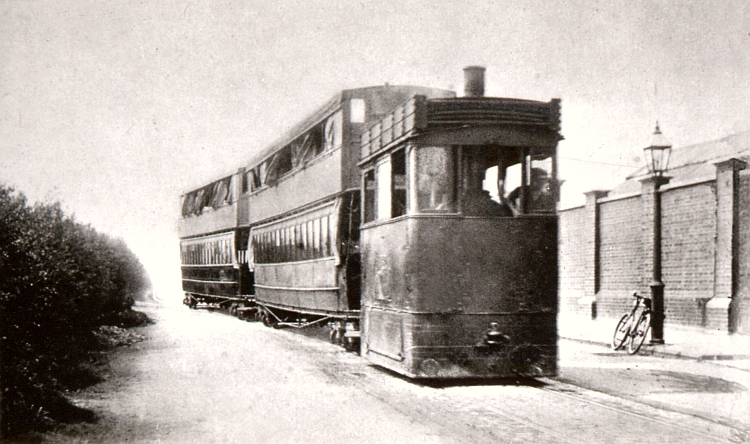

However, one steam tramway survived longer than others. The 2½-mile

Wolverton and Stony Stratford Tramway opened in 1887 to bring

workers from outlying districts into the London & North Western

Railway’s large carriage works at Wolverton. It ran until 1926

earning the dual distinctions of having the largest trailer cars in

Britain (seating 100 passengers) and being our last steam-worked

street tramway.

The Wolverton steam

tramway

In 1887, reports appeared in the local press of a plan to build a

tramway linking Tring Station, via the town, with Aylesbury —

whether the system was to be steam or horse powered is not

mentioned, but taking account of the length of the line and its

gradients, steam seems likely. At the same time a grander

scheme was announced for a steam tramway linking Hemel Hempstead,

Boxmoor, Chesham, Berkhamstead and Northchurch. Descriptions

of the route and its gradients held in the Hertfordshire Archives

show that detailed surveying was carried out before the scheme was

announced. The line was to commence opposite the goods

entrance to Tring Station, cross the Grand Junction Canal over the

existing bridge and proceed up Station Road (gradient 1:65) to Tring

Lodge, after which it would descend (1:20) to Brook Street.

The line would climb steeply at Frogmore Street (1:18) followed by a

gradual ascent to the summit of Tring Hill (1:48) before descending

(l :20) to the Vale of Aylesbury, after which the route to the

Aylesbury terminus was comparatively level (1:100).

Press reports do not mention the extent to which the scheme was

supported by the townsfolk, but there were some objectors:

THE TRAMWAY SCHEME. — A Tring correspondent writes: We understand

that Lord Rothschild, Mr. Williams, and other owners of property in

the narrow part of the High-street have objected on public grounds

to the laying of the Tramway there. Even with the present traffic

the street is narrow and insufficient, and accidents, especially on

market days, are not infrequent. The promoters will, it is thought,

abandon the scheme, without incurring the expense which opposition

at a later stage of the order would entail upon them.

Bucks Herald, 17th

November 1887.

When the Tring Local Board met to discuss the scheme, their main

concern was that part of the High Street was too narrow to meet

statutory requirements:

LOCAL BOARD.— The Clerk read several sections of the Tramways’

Act, 1870, which referred to the position of the Board with regard

to the persons interested in that portion of the High-street which

was too narrow to allow the required width on each side of the

rails.— Mr. Elliman thought they should not forget that the tramways

would give facilities for getting about, and that they were

generally advantageous to a town. It might be the wish of the

townspeople to have the tramway.— After some discussion, the Clerk

was directed to issue a circular, drawing the attention of the

inhabitants to section 9 of the Act of 1870, which provides for the

case in which the street is too narrow to admit a width of “9 feet 6

inches between the outside of the footpath on either side of the

roadway and the nearest rail of the tramway.”

Bucks Herald, 3rd December

1887.

The Tring and Aylesbury Tramway scheme was finally laid to rest when

its promoters met Lord Rothschild, whose main objection to the

tramway was that it would not be a financial success. How this

would affect anyone other than the scheme’s promoters and

shareholders is unclear, for they would probably have been required

to arrange a bond to cover the cost of road clearance should the

scheme fail. The following newspaper report also refers to

other objections, which presumably included the narrowness of the

High Street, while local folklore has it that his Lordship objected

to trams passing his residence:

THE PROPOSED TRAMWAYS SCHEME.— It is stated that Mr. Wilkinson,

the promoter of these schemes, accompanied by the solicitor and the

engineer, had an interview with Lord Rothschild, Messrs. Leopold and

Alfred de Rothschild being also present, at New Court, St. Swithin’s-lane,

on , Wednesday, as to the proposed line from Tring to Aylesbury, and

that his Lordship having intimated that the line would not receive

his support because, among other objections to the scheme, he

considered it was a line which would not be a financial success, it

was decided to abandon the project. But as his Lordship at the

same time intimated that he felt certain that the line from Chesham

to Hempstead would be supplying a long-felt want to the district,

and also prove a certain commercial success, it has been decided to

press forward the project with the upmost vigour.

Bucks Herald, 24th

December 1887.

What is surprising is that the tramway promoters appear not to have

foreseen such predictable obstacles before incurring surveying,

planning and legal expenses. To modern eyes it might also seem

extraordinary that his Lordship’s word should carry such weight in

the matter, but this was an age in which the peerage was

considerably more influential than today, as is evidenced by the

London & Birmingham Railway’s application to Parliament in 1832,

which was thrown out — at great cost to the Company — by Lord

Brownlow of Ashridge and a coterie of peers who had no more

justification than they happened not to like railways.

As for the Hemel steam tramway scheme, it too sank without trace.

Newspaper reports suggest that although it met with public approval,

there were also influential objectors among who was Sir Astley

Paston-Cooper, a landowner in the Hemel area (whose ancestor’s

objections had helped cause the route of London & Birmingham Railway

to be changed). Cooper, it appears, “thought the tramway

horrid. People in London liked to come into the country to

enjoy the peace and quiet there, but would they come if a beastly

tramway were introduced?” The Hemel scheme did obtain its

Act of Parliament, but despite overcoming that legal obstacle to its

construction it was abandoned, probably owing to lack of finance.

――――♦――――

A WALK AROUND TRING

as it was in the eighteen nineties

by Joseph Budd (written

c.1966)

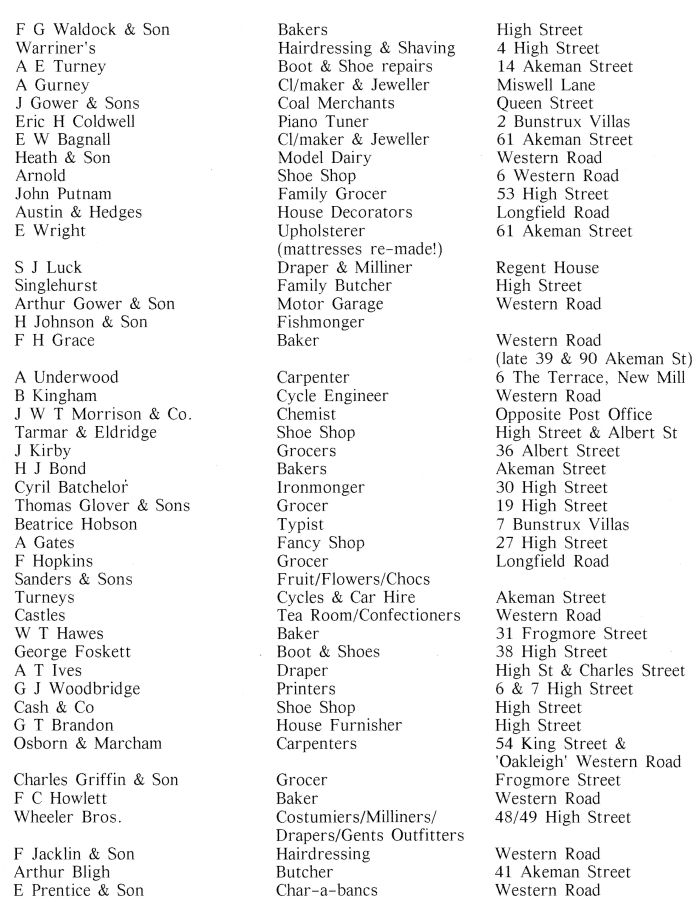

In these days of Progress and Changes and with the town centre the

subject of much debate, suggestion and criticism, it might be

interesting to walk round the town and recall some of the features

which have changed during the past three quarters of a century.

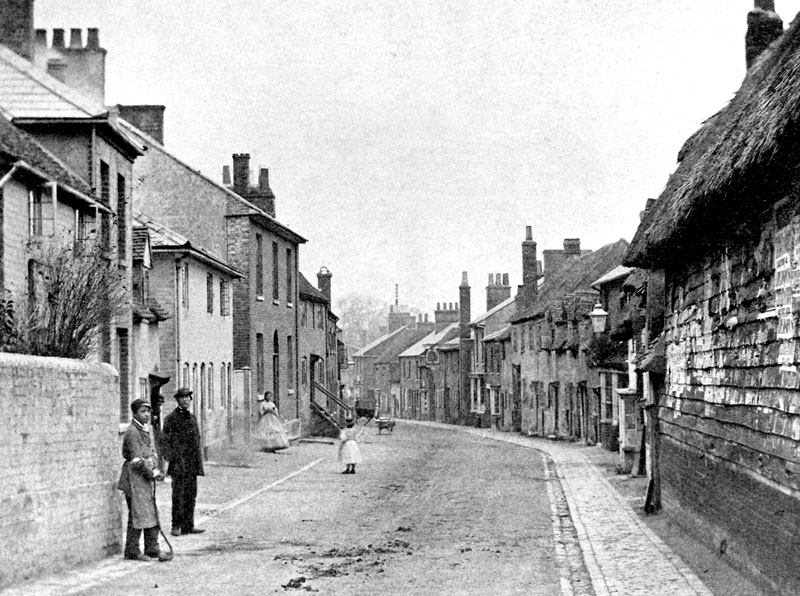

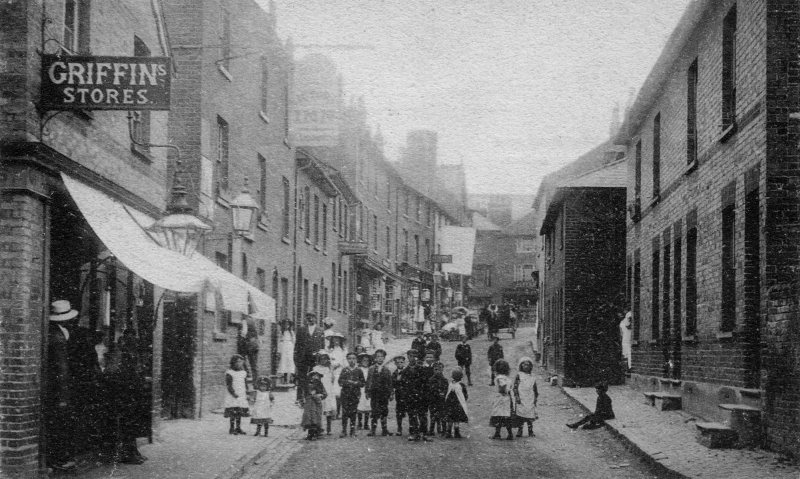

View looking down Akeman Street.

The Jolly Sportsman (now Louisa Cottages) is on the left.

Photo courtesy of Jill Fowler and

Mike Bass.

About 1890, the extent of the town would have been described as

“from Lower Dunsley to Bottle Cross, and from the Red Lion to the

Jolly Sportsman”. This does not convey much information today, but

we will indicate these cardinal points as we walk round.

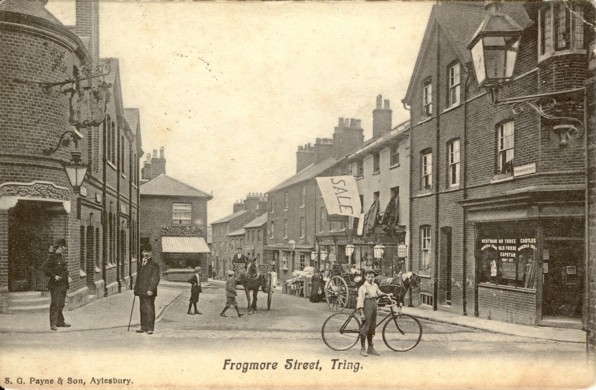

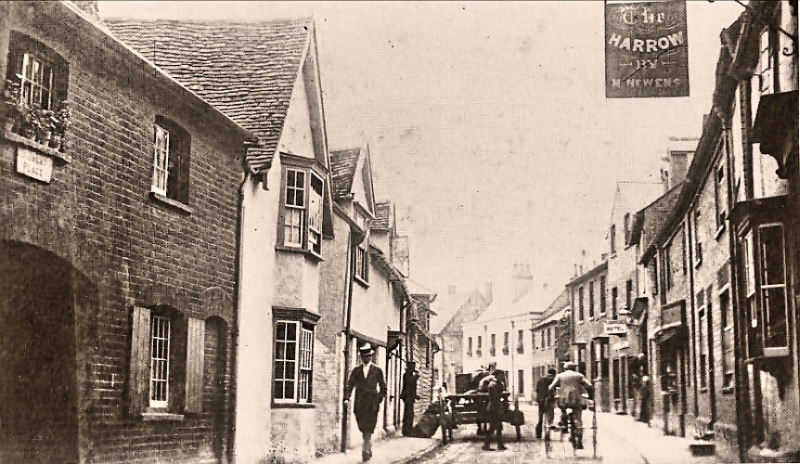

The George public house at the

junction of Frogmore Street and the High Street.

Photo courtesy of Jill Fowler and

Mike Bass.

Where to start? Where else but the “George Corner”, but a different

prospect from the present time, with the original George Hotel some

yards further east making the entrance to Frogmore Street narrower

than it is now.

|

.JPG) |

|

Joseph in Home Guard uniform, 1943 |

A shop on the other corner of Frogmore Street was Mr Dan Bedford’s

barber’s shop, haircut two-pence, shave one penny. Opposite to this

on the corner of Akeman Street was Mr Jeffrey’s chemist shop, still

a chemist but the name Jeffery is vanished many years ago. The two

great flasks of coloured water have also gone, replaced by one only

half the size. Two fishtail gas burners behind them showed them up

splendidly well as illuminating the shop. Another small burner on

the counter was used for sealing wax. When dispensing a bottle of

medicine, Mr Jeffery always wrapped it in paper and sealed it before

handing it over.

On the other corner of Akeman Street, on the site of the present

Market House, was Mr Mead’s slaughter house. This also was further

east making Akeman Street as narrow as Frogmore Street. The

slaughter house was a timber building, heavily tarred, with a hole

in the boards low down through which a rope could be passed to pull

down a bullock for the poleaxe. Boys on their way to school would

often help to pull.

We will now leave the crossroads and explore the High Street. Next

door to the chemist was Mr Lawsons grocery store, a good shop well

stocked. One department was the off licence, and one line here that

sticks in the memory is a quart bottle of Tarragona Port for two

shillings. The liquor trade has now ousted the grocery trade but

next door Mr Brown’s brewery has reversed the process and “gone dry”

being now a butcher’s shop.

Doctor Brown’s surgery was next door, and he had not yet built Harvieston in Aylesbury Road, now the Convent of St Francis de

Sales.

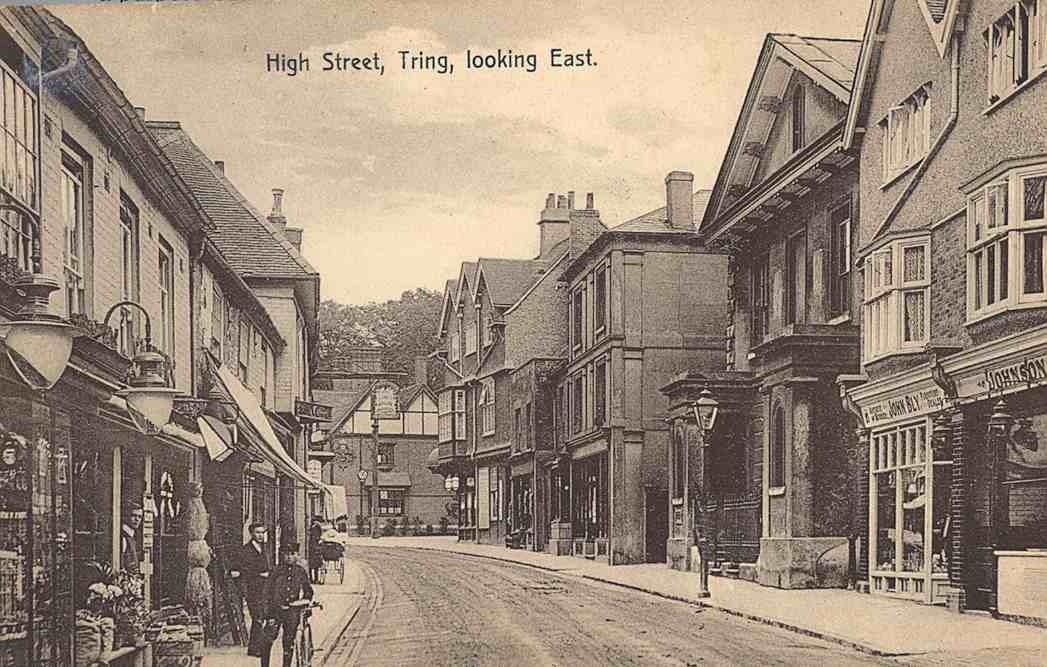

Next, Mr John Bly’s furniture shop and Johnson’s butcher’s shop and

slaughter house, the site now occupied by the Midland Bank [on

the right

of the picture below].

Bank Alley was much the same as at present, except that there were

cottages on the right hand side going up. They were dilapidated

smelly old places, but some were still occupied. One of the last

tenants was old Mr Rivett, a little old man who had to use two

sticks to walk. He was one of the people who had to exist on Parish

Relief, a few shillings to prevent absolute starvation. An

occasional shilling from people like Mr Tommy Glover was a godsend

to him. His end was rather pathetic. His favourite walk was to

Thorn’s Meadow in Station Road, to sit on the grass. One warm

afternoon he just sat and died. He had a Pauper’s Funeral in the Old

Cemetery, not very elaborate.

The bank adjoining the Alley was at that time Butcher’s Bank, but

has changed its name and proprietors several times, ending up as the

National Provincial.

Glover’s next door was considered the premier grocer’s in the town,

carrying a large stock of provisions, and also in their off-licence

department being agents for W & A Gilbey’s wines and spirits.

Incidentally, they supplied a good part of the groceries to

Rothschilds at the Mansion, and when Mr Tommy Glover called there

for their order (which he always collected himself), it was

customary for his to be taken through to Lord Rothschild for half an

hour of friendly conversation.

Several shops followed before the Rose & Crown, including Baldwin’s

(tailor), Stevens (boots and shoes), Allison (corn chandler), etc.

The Rose & Crown, which stood flush to the footpath, had been the

principal coaching and posting house, but of course those days were

over, and though the stables still contained plenty of horses, the

vehicles were no longer coaches, but Broughams, Landaus, and even a

wagonette. Mr Jesse Thorn was the landlord. He rented the first

meadow on the left in Station Road for his horses in the summer, and

it was known as “Thorn’s Meadow” right up to the time houses were

built on it a few years ago.

Passing the entrance to the Avenue, we shall come to Mr Ebenezer

Charles Bird’s stationer shop and printing works. This shop was up

some steps, but the stocks of pencils, crayons, writing books, etc.

were a magnet to small boys and girls with a few coppers to spend.

Mrs Bird was a nice woman and very kind to juvenile customers. This

was Mr Bird’s second wife, his first having died in 1849 at the

early age of twenty-five. Her tombstone in the churchyard bears the

touching inscription; “Life is even as a vapour which appeareth for

a little while, and vanisheth quickly away.”

This was the last shop before the Market Place. On Fridays the first

stall this side was invariably that of Mr Garner, pastry-cook and

cake baker, from Aylesbury. One of his best known lines was a

Madeira cake, complete with paper band and a liberal piece of candy

peel on the top, for one penny. Looking over the wall on this side

of the Market Place we should probably see an emu or a kangaroo or

two surveying the scene from their elevated position, and quite

unperturbed by the passing traffic. The road being below the land on

either side, in what was known as a “Ha-ha”, was not visible from

the Mansion, and the vista from there appeared to be unbroken grass

all the way to the horizon.

At the lower end of the Market, where the Memorial Garden Gates now

stand, was the Green Man public house. The landlord was Mr Woodman.

He collected the tolls from the stallholders, and as he approached

each one he had a habit of rattling the shillings he had already

taken, and naturally became known as “Jinker” Woodman.

The Green Man public house

Beyond the public house was Doctor Pope’s residence. This was a

rather nice house, complete with stables and coach house. He kept a

smart carriage and employed a coachman. When this house was

demolished it was interesting to note that the window frames were

made of mahogany; quite unusual.

From here to the beginning of London Road was Lower Dunsley, so

called from its proximity to the “Dunsley Field”, the ancient name

for the field which is now Dunsley Farm, and to distinguish it from

Upper Dunsley, a collection of old cottages standing near the site

of the present farmhouse and buildings. Near the turning to Upper

Dunsley, near the main road was the “Pound”. This was a fenced

enclosure in which any horse or farm animal which strayed upon the

highway could be confined until redeemed by payment of a fine to the

Overseers of the parish. The meadow is still known as Pound Meadow.

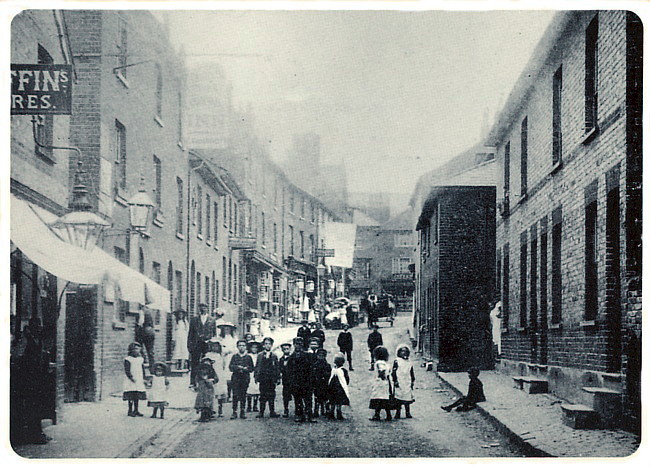

Lower Dunsley viewed from the

Robin Hood Corner.

Photo courtesy of Jill Fowler and

Mike Bass.

To return to Lower Dunsley, the iron marker of the Sparrows Herne

Trust can still be seen. These were the people who maintained the

road and took tolls at the various turnpike gates on the London

Road.

Near the marker stood the “Hole in the Wall”, an old-fashioned

public house complete with oak-beamed tap room, and a copper

“Muller“ for anyone who wished to warm their beer. This did

occasionally happen on very cold days, but most beer drinkers would

say “It’s poor beer if it won’t warm itself”. The name was only a

nickname, as it was only a beer-house retailing beer from the

adjacent brewery.

Standing in front of the Hole in the Wall, and looking down Brook

Street, one would have seen, on the present Cattle Market, a row of

cottages. These belonged to the Silk Mill, and had been in

bygone days occupied by “Prentice Girl”. These were

girls who had been an expense to the Overseers of their home

parishes, and if a girl had a good character she could be accepted

as an apprentice at the Silk Mill and earn her living. There

were “house-mothers” in charge of these girls, several of whom

eventually married Tring men.

The Mill Pond at this time filled all the space from here to the

Silk Mill itself, but when the waterwheel was no longer used most of

it was filled in and planted with fruit trees. These trees

have now about finished their useful life, and in 1966 no one

bothered to gather the crop.

Leaving the prospect of Brook Street and returning to the Market

Place, and passing Mr Billy Fulks’s butcher’s shop, we should find

the Green Man meadow, which was the recognised site for visiting

circuses. One that came every year was Fossett’s, a good

little show, but when “Lord” George Sanger’s circus came, that

really was an event. The procession around the Town was indeed

something to remember. The great wagons drawn by teams of six,

eight, nine or even twelve horses had to be seen to be believed.

There being no overhead wires such as telephones and electricity

supply, the wagons could be built up to a great height and the

climax of the procession would probably be Britannia or some other

allegorical figure, seated on a throne nearly twenty feet above the

roadway.

A Sanger’s circus parade.

Leaving the Market Place we should pass Mr Putman’s grocer’s shop,

and Tomkins ironmonger’s ditto, and come to the Plough Inn,

landlord Mr John Penn (now Frank Bly’s shop). Several of the

plait buyers from Dunstable and Luton used to make The Plough their

headquarters on market day.

The High Street looking West -

the old Market House (below) has been demolished

Following on, to what is now known as Church Square, with its car

park and bus shelter, here stood the old Market House. This

was an ugly old building of two storeys, the ground floor paved with

flag stones and enclosed by very heavy iron fencing, and the upper

story entered by a door in the eastern end by means of a removable

step ladder. On the ground floor, in a brick wall, was the

entrance to the “cage”. This was a dungeon-like cell, very

strongly built, dark, and with an oak door four or five inches

thick. There was a stone bench for the occupant to sit on, and

the whole place looked most cheerless and uncomfortable. There

was a small grille in the door for observation purposes.

The old Market House in what is

now Church Square.

If the old building were to be standing today it would be venerated

as an ancient monument, but at that time it was only on eyesore,

especially to Lord Rothschild when he came out the of the Avenue in

his carriage, and when his Lordship gave a site for a new Market

House at the corner of Akeman Street it was gratefully accepted and

the old one demolished.

Next to the Market House was Mr Booker’s fish shop and the last shop

before what is now Brown & Merry’s offices was Thorps (another

grocer). A memory of this shop is of whole cheeses stacked

five high on either side of the doorway.

The Bell Inn was one of the pubs that opened at 6 a.m. for the

benefit of customers who had drunk a “skinfull” overnight, and

needed a “livener” to “waken the dead”.

Among the shops on this side of the street were Mr Clement’s

(jewellery, watches, etc.), Pitkins (saddler and harness maker),

Greenings (drapers and clothiers), and Mr James Edwin. This

last shop was famous for pork pies, which were known for many miles

around.

Above: looking down Frogmore Street from the crossroad

Below: looking up Frogmore Street towards the crossroad

We are now back to Frogmore Street. Passing Parsonage Lane,

Church Lane, Stratton Place, and Westward Lane, we should come to

the “Square”. This is what is now the Car Park, and consisted

of a row of cottages in front, with an archway giving access to a

yard behind surrounded by other cottages, with no back doors.

When they were demolished some of the resident families were moved

to “Sugars Green”, the council houses off Brook Street near the Gas

Works. A few yards beyond the Square was the Pawnshop, which had a

regular clientele among the poorest and most shiftless of the

populace. Next to the pawnshop was the Fellmonger’s Yard, no

longer used as such but keeping the name. A fellmonger dealt

in sheepskins, which he processed in such a way as to remove the

wool and leave the skins ready for conversion into thin leather,

suitable for making such things as hedging gloves, etc. The

process was eventually concentrated at Thame, and then the skins

were only collected here, and taken there by Mr Jack Olliffe with

horse and van.

Almost opposite to the Fellmonger’s Yard was the “horse pond”, the

last remaining evidence of a stream which at one time ran through

this valley to the Brook (of Brook Street), crossing the road in a

watersplash. When the Silk Mill was built, and the Mill Pond

made, this was the main source of the water supply for the

waterwheel which drove the machinery. A culvert was put in

crossing Pond Close and discharging straight into the Mill Pond.

Next to the Fellmonger’s Yard was the Black Horse pub, and next

again the Red Lion. These were both lodging houses as well as

beer houses. They catered for “travellers”, not tramps, but

such people as organ grinders, street singers, German Bands, mat

menders, dancing bear keepers, fire eaters, knife grinders, etc.

The Red Lion had an annex in the back yard which served as kitchen

and day room for the lodgers. The scene in there when a dozen

or more were present would have made a good picture for Hogarth.

This couple would visit Tring

every 6 months and stay in the Red Lion

for 1d a night, leaving their barrel organ parked in the yard.

Behind this, on land now partly covered by the telephone exchange,

was Saws Alley, a row of old cottages built in such a way that the

earth at the back was almost up to the upstairs windows. Mrs

Saw lived in one, and the remainder were occupied by a poor class of

tenants. When Mrs Saw died, and her house was cleared out,

there was more than half a ton of old clothes, garments which

tenants had persuaded her to accept in lieu of rent.

Back in Frogmore Street, and almost opposite to the Square, was the

Chapel, built in 1751 (and still used as such in 1890). Like

other Baptist chapels in the Town, this one has a gallery to

accommodate the expected large congregation, but whether it was ever

necessary is a moot point. The people who built it never

imagined that it would end its days as a residence and antique shop.

Arriving back at the High Street and proceeding up the School Hill,

one of the first shops to catch the eye was a harness maker’s.

This was kept by Mr Jennings, universally known as “Dad” Jennings.

He was also the bandmaster and conductor of the Town Band. A

few yards up the hill on the other side of the road is the

Conservative Club. When this was being built some ill feeling

cropped up between two bricklayers working on the front gable end,

and the two hob carriers serving them with bricks. It was a

tidy height and the labourers were inclined to take an occasional

rest, at which the “brickies” would ring their trowels and call for

bricks. In retaliation, the two hod carriers decided to

overwhelm them with bricks, and in a little while they had more than

a ton supported by one “ledger”. Of course it broke, and down

came scaffold planks, putlogs, bricks, hods and carriers. It was a

marvel that no one was killed.

Tring Junior School, formerly

Tring National School.

Photo courtesy of Jill Fowler and

Mike Bass.

A few yards further at the top of the hill were the National

Schools. About this time great excitement was caused one day

by a stag which ran through the High Street followed by Lord

Rothschild’s stag hounds. It was cornered in the boys’

playground. Fortunately the whippers-in were well up and were

able to net the stag and keep the hounds off until the stag cart

arrived, when he was loaded up and taken back to Ashridge Park

whence he had been borrowed.

The schoolmaster was Mr Henry Hobson, and although his eyesight was

failing he was long remembered for doing wonders with the boys he

had, in the time he had them. They would leave school at any

time after their thirteenth birthday and if a boy had not got a good

grounding in the threes “Rs” by then, it was most likely his own

fault. If a boy had reached Standard Four he could take what

was called the “Labour Exam”, and if he passed he became a

“half-timer” when he was twelve. After this, for the next

year, he only attended school five half-days a week, and could go to

work for the rest of the time.

The other end of the building was occupied by the girls’ school.

The school mistress was Miss Luffman, and like Mr Hobson she held

the post for a long time. She is still spoken of with respect

and affection by some of her former pupils.

Opposite to the boys’ school was the chemist shop of Mr Marsh, where

many a boy had an aching tooth extracted for which the charge was

one shilling without anaesthetic.

the High Street Chapel was nearly new, having been built in 1889,

which from the start had attracted a numerous congregation. It

was not as strictly sectarian as some and eventually became known as

the United Free Church.

By 1896 it was strong enough to send quite a large party to a choral

festival at the Crystal Palace, where they sang with choirs

assembled from all parts of southern England.

The next building of note was Elm House, the home and surgery of Dr.

Le Quesne. As the name suggests, he came from the Channel

Islands. His carriage and coachman were well known throughout

the town and surrounding villages.

Elm House, later renamed Ardenoak House, stands at the junction of

Langdon Street

and the High Street. Now a Grade II listed building.

Beyond Griffins Lane (now Langdon Street) was a meadow extending

extending as far as Gowers Street (now Queen Street). The

meadow was owned by the Elliman family, who were drapers in the High

Street. Eventually they had a house (Westcroft) built on it

and lived there. They were related to the Ellimans of Slough,

who produced the famous Elliman’s embrocation. Before any

houses were built on this land an attempt was made to dig gravel,

but the product was not clean enough and this was given up.

The road at the Western end of this meadow became known as Gowers

Street because Mr John Gower had his house and stables built there,

but when it was properly made up and kerbed and channelled it was

officially named Queen Street.

Passing on to Henry Street we should pass the terrace of five small

cottages, each with its tiny front garden. Three of these

having been converted into shops the gardens have disappeared ,

leaving a nice wide pavement or forecourt. These cottages have

brick fronts but the back walls were mainly built of flints.

The five cottages in Western

Road.

The Baptist Chapel a few yards further on - now demolished - never

seemed to attract a large congregation, but thanks to the liberality

of two or three members was able to carry on some time after similar

chapels had closed. The house next door, demolished at the

same time, was occupied for many years by Mr Fred Rolfe, after he

moved his business from Albert Street. It is believed that the

intention was to build a good shop on this site, but apparently

something prevented this and the only result of the demolition has

been the creation of an eyesore.

Beyond Chapel Street and with its gateway in Western Road was

Fincher’s builder’s yard, with its stables , stores, machinery,

carpenters shop, etc. The boss of the business was Mr John

Fincher, but the day-to-day management was in the hands of Mr Bert

Cook, a man liked and respected by all who had dealings with him,

whether as employees or customers. Finchers had their own

brickfield at Buckland Common where they made good multi-coloured

bricks. Many of the houses they built could be recognised by

the bricks and the workmanship.

A few yards further on was Amsden’s coal yard and stables.

This was not a big business, but they always had a couple of real

good horses, and their harness and trolleys were always kept in

top-notch condition.

Near the end of Western Road on the other side of the Street, was

the ironworks of the Crawley Brothers. their business was

mainly agricultural and industrial blacksmithing and forging, and

not horse shoeing, which was done by the various farriers scattered

about the Town.

Next to Crawley’s place was Mr Parrot’s coach building works.

Most of the vehicles built here were in the light category, such as

pony traps, governess carts, wagonettes, etc. and some excellent

skilled work went into their manufacture. Both these

properties have been replaced by Wright & Wright’s motor works and

showrooms.

At the corner of Duckmore Lane was a row of cottages. In the

gable and facing Western Road was built a cross of black bottles,

bottoms outward. It was only a gimmick, but the name bottle

cross for this corner of Town persisted for many years, long after

the cottages were demolished.

The Bricklayers’ Arms at Bottle

Cross

On the Town side of the cottages was a public house, the

Bricklayers’ Arms, and a stonemason’s yard. The land behind

these properties belonged to the Rothschild estate, and when the

site was leased it was included in the same field. But it was

a poor stony field and eventually it was planted with trees and in

due course became known as “The Spinney”. By the time part of

it was cleared to make room for Woodland Close it could have been

described as a wood. But before any of these alterations could

take place the road was narrow with a high bank and tall overhanging

hedge, and was well named Dark Lane. This was the recognised

name as far as Chapel Street after which it became Park Road.

Above: Park Road looking towards

the Natural History Museum.

Photos courtesy of Jill Fowler and

Mike Bass.

Below: Park Road viewed from the opposite direction. Louisa Cottages

were extended in 1901.

The “Furlong” was much as it is today, except that the trees in the

grounds have grown out of all proportion, some of them now being

eighty feet high, but across the road the “Weaving Shop”, which was

then a busy canvas factory, has been gone many years, and the site

is occupied by a clump of trees. The looms were operated by

middle-aged and elderly men but there was a constantly changing

quota of boys doing a job called “quill winding”. The wage for

this was half-a-crown a week, so few boys remained long but left as

soon as anything else offered.

Twenty yards up the farm road at the side was the footpath to West

Leith, but when Lord Rothschild bought the weaving shop and had it

demolished, this path was closed and replaced by the “New Path” off

Dark Lane.

About this time the farmhouse at Home Farm suffered a disastrous

fire and was destroyed. It was a freezing cold night, and the

firemen were covered with ice when they came off duty in the

morning. The present house was built a year or two later.

Almost opposite the farm drive was Arnold House, originally built as

a sort of vicarage for St. Martha’s Church. It was altered and

enlarged years ago, and named The Old House.