The history of Tring Silk Mill is varied and touches on many

different subjects, and I hope that all readers will find

something that interests them. This edition has been

slightly revised since the first printing in 2008, and I am

particularly grateful to Ian Petticrew for his editing

skills.

The following individuals and organisations all contributed

greatly, and in various ways, to the preparation of this

book, and I acknowledge with thanks the contributions of

Mike Bass, Marjorie Clarke, Alec Clements, Jill Fowler, Len

Major, Linda McGhee, Ann Reed, Alan and Tracey Taylor,

Shirley Thornhill, William A.Wells, and Martin Wheeler. The

staff of Tring Library, the Hertfordshire Record Office, the

Aylesbury Local Studies Centre, Alexandra MacCulloch of

Buckinghamshire Resource Centre, Bexley Local Studies &

Archive Centre, Hannah Kay of the Bexley Heritage Trust, and

the Redbourn Museum.

W.M.A.

May 2014

By the same author:

Tring Personalities

More Tring Personalities

Further Tring Personalities

The Tring Collection (compilation

of local history and verse)

Tring Gardens: Then and Now

The Second Tring Collection

(compilation of local history and verse)

History of Tring Bowls Club: 1908-2008

The Mystery of the Tring Tiles

They Called us to Arms

with Ian Petticrew:

Gone with the Wind: Windmills and those around Tring

Grand Junction Canal: a Highway laid with Water

The Railway comes to Tring: 1833-1846

Roads and those in Tring

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 1

The Early History of Silk

It is a long and winding road from China in 2640 BC

to Brook Street in Victorian Tring. But if Empress Hsi Ling

Shi (venerated as the Goddess of Silk) had not used her powers of

observation when strolling in the mulberry tree groves of her

husband’s palace, there would be no connection at all. Legend

has it that she noticed that the caterpillars of a certain moth (Bombyx

Mori) were feeding on the mulberry leaves before spinning their

silvery, white cocoons. She took one cocoon inside where it

accidentally fell into warm water and, as the water was absorbed, it

began to unravel revealing a continuous mile-long delicate network

of fibres. From this small beginning, the Empress is credited

with the invention of the loom, and later gave her patronage to the

silk industry.

Bombyx Mori - caterpillars and moth

For some 3,000 years the Chinese endeavoured to guard their secret,

and it was not until around AD 300 that the western world became

aware of the existence of an almost magical fabric. From then

on came the gradual establishment of an export route from China

which became known as the Silk Road, with its romantic images of

endless deserts and dunes; trains of hundreds of merchants and

camels; remote oases; bustling caravanserai; and fabled cities like

Samarkand. However, the history of the silk industry in

Britain was the opposite of romantic, as will be outlined in later

chapters.

|

|

|

Silkworm cocoon |

It took until the twelfth century for the art of producing silk

cloth to reach France, Spain and Italy, and this was brought to

England by the Huguenots, Flemish Protestant refugees escaping

religious persecution. They set up business as silk weavers, and

invented a technique which resulted in glossy lustre on silk

taffeta. At first establishing themselves in Spitalfields, they then

extended their activities to Coventry and Norwich.

James I of England was an enthusiastic supporter of the early silk

industry, and ordered that 10,000 mulberry trees be planted across

the land, but the choice of the Black Mulberry proved unfortunate as

this species will not thrive in a temperate climate. A later

experiment in 1718 in Chelsea Park also failed, and further attempts

to grow trees and breed silkworms met with only limited success.

This is not surprising when it is realised that it takes around 630

cocoons to provide sufficient thread for one blouse. The main source

of raw silk had to remain the imported skeins from China and the

warmer parts of Europe.

Two Norfolk brothers, John and Thomas Lombe were responsible for the

development of factory-based silk production. Travelling to Italy,

John set out to discover the secret of successful silk spinning, a

dangerous assignment as the penalty for industrial spies was death.

He bribed his way into employment as a machine winder in one of the

Sardinian mills, and smuggled his drawings of the machinery into

bales destined for export to England. It was thanks to this brave

mission that manufacture of silk on a commercial scale was

introduced to this country.

The northern town of Macclesfield grew to become the leading centre

of silk production in the country, with 120 mills and dye houses.

Some accounts state that William Kay, the founder of Tring Silk

Mill, had interests in Macclesfield, and both Henry Rowbotham and

John Akers, were born in that town. These two long-serving Managers

at Tring Mill brought with them the necessary skill and knowledge to

insure that the venture in Brook Street prospered for over sixty

years.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 2

The Local Silk Industry

There was never a tradition of large-scale textile production in

Hertfordshire, but at the end of the eighteenth century the demand

for silk, the expense of manufacturing it in London, and the ban on

its import during the Napoleonic Wars, led to the setting up of

various silk-throwing and -weaving mills in the county. Astute

businessmen, seeing the advantages of the nearness to the capital

and the local unpolluted fast-flowing chalk streams, took the

opportunity to convert old water-powered corn mills for use in the

silk trade.

The first mill in west Hertfordshire was probably established around

1760, and built in level meadows in the hamlet of Oxhey,

one-and-a-half miles south of Watford on the banks of the River

Colne. The four-storey mill towered over its surroundings, and on

one side stood the grand house of the mill-owner, and on the other

the 34 tiny cottages of the mill hands. It became known as Rookery

Mill after the noisy birds nesting in the nearby trees. (The name

lives on today - one end of Watford Football Club ground is called

‘Rookery End’.)

Ownership passed to two Huguenot brothers, the Paumiers, who carried

on trading until 1820 when it was sold to Thomas Rock Shute who ran

that and another mill in Bushey. A trade directory entry mentions

three silk mills in Watford and states ‘silk throwing was the

principal manufacture of the town’. The other two mills were at Red

Lion Yard and Clarendon Road, and both at first were powered by

horses. At the end of the nineteenth century when the silk trade was

in decline, the workers at Watford were not so fortunate as their

counterparts at the Tring Silk Mill when Lord Rothschild rescued the

situation (see Chapter 12). The History of Watford records “Rookery

Mill was closed from depression of the silk trade, the hands thrown

out of employment, and considerable privation was endured by many of

them”. In late Victorian times it was converted to become Watford

Steam Laundry, but no trace of the premises remain today.

St. Albans Silk Mill

At St. Albans, on the site where monks once ground their corn, a

silk mill was established on the River Ver in the shadow of the

great Abbey on the edge of today’s Verulamium Park. Three floors

high, it was bought by the Woollam family and, as at Tring, was

powered by water and steam. As well as paupers from the town, a

smaller concern at Hatfield also drew on this source of labour. For

some reason this arrangement was not as successful, and in 1857 the

Wollams decided to transfer their operations to Redbourn.

Always a steam-powered mill, the factory at Redbourn was built

beside the Common and, at its peak, employed 140 mostly local men

and women. As at all factories, the dreaded ‘mill bell’ rang at the

crack of dawn six days a week rousing the sleepy workers to come

scurrying through the factory gates. Both Redbourn and St. Albans

mills were taken over by Maygrove & Co. in 1906, and when cheaper

foreign imports threatened production at Redbourn, operations

diversified with the output of rayon, embroidery silk, and

upholstery trimmings. The timely closure of the mill in 1938 enabled

the Brooke Bond Tea Company (which had been displaced from London by

bombing raids) to acquire the site and eventually to build a much

larger factory. About 50 years later, the company donated the old

Silk Mill Manager’s House to Redbourn Parish Council for use as a

museum of local history.

|

|

|

The bell from Redbourn Silk Mill |

Another more short-lived venture in Rickmansworth, the three-storey

Batchworth Mill had several uses, and for a while was run as a

cotton mill. The work-force included London children from the

workhouse in St. James, Piccadilly, and a second mill operated in

Rickmansworth High Street.

In the main, during the boom years of the silk trade, the risk of

setting up these mills paid dividends for their proprietors. In

1824, the largest and most successful operation of all was set up

and financed by an astute businessman and entrepreneur, William Kay,

in Tring on the western edge of Hertfordshire.

It was money generated by the silk trade that supplied another

direct connection to Tring. The Williams family, who acquired the

Pendley Manor estate, had inherited a fortune from profits amassed

in the manufacture of a specialised type of silk. The founder of the

family, Joseph Grout, probably started to trade in Spitalfields, and

with his brother invented or learned a way of making black embossed

silk crêpe. The obsession of the nineteenth century with mourning

attire, popularised in large measure by Queen Victoria after the

death of the Prince Consort, led to huge sales of this particular

textile.

Joseph Grout (1776-1852)

In 1806 the Grout brothers started a firm in Norwich to throw and

weave silk crêpe. Other factories followed, as well as a showroom in

London, and a silk-reeling works near Calcutta. Nearly fifty years

later their products were of sufficiently high a quality to be

displayed at the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace. The

catalogue entry tells us that Joseph Grout & Co. manufactured:

Folded and rolled black crape (sic), single, double,

treble and four threads.

Coloured aerophane crape.

Coloured lisse gauze.

Gossamer of various colours, used for veils.

Silk gauze grenadine scarves, and brocaded.

Silk muslin scarves.

Brocaded silk muslin dresses, with flounces etc. |

It is possible that Joseph was acquainted with William Kay and was

aware of his ownership of the Tring Park estate for, in 1844, he

rented the mansion from William’s Trustees. On Joseph’s death

the tenancy passed to his illegitimate son, the Reverend James

Williams. Knowing that the Tring Park estate would soon come

to the market, James Williams very much wanted to buy it for

himself, but knew he could not match any winning bid of Baron

Rothschild. He satisfied himself with his estate at Pendley,

where he constructed a brand new house.

Memorial windows to both Joseph and James can be seen in Tring

Parish Church, and the large house at Pendley has been converted to

an hotel. The factory Joseph established continued to prosper,

and received the Royal Warrant in 1895. In World War II it was

one of only two firms to make parachute silk for the Government, but

ceased trading in the 1990s, 189 years after the Grout brothers

first established the business.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 3

William Kay

(1776-1838)

Founder of the Silk Mill

In the late eighteenth century, the small town of Wigton in the

north of Cumberland was a centre of the weaving trade, and the

spinning factories here used imported cotton, locally-produced wool,

and linen from flax grown on the Solway Plain. On the moors

above the town stood The Mains, a large house occupied by a

yeoman farmer. Neither of his sons, William and Joseph Kay,

were interested in a farming life, preferring to direct their

considerable energies to the opportunities offered by the local

textile industries.

It was not long before both young men were drawn to Manchester,

which was rapidly expanding due to the enormous profits being made

in the spinning mills. From small beginnings as a cotton

throwster, William diversified and established a large mill for both

cotton and silk manufacture near the centre of the city. Later

on in Tring, his valuable experience gained in the silk trade was to

prove very profitable for both brothers.

It is possible that during his time in Manchester William first met

Nathan Rothschild, founder of the English branch of the famous

family, who had settled in that city on his arrival in this country

(Nathan’s immense fortune had its beginnings in the textile trade,

and he was one of the first to take advantage of the new technology

of printing onto cotton fabric.)

William Kay typified the go-ahead ambitious man who seized his

chance to make money on the back of the Industrial Revolution.

Using wealth made in the textile trade in Manchester, he moved south

to London where he increased his fortune by his dealings on the

Stock Exchange. By this time, he was well able to afford a

smart town house at York Terrace, Regent’s Park, and to marry a

young second wife, who in 1833 bore him a son.

In 1820 he had widened his business interests even further by

purchasing the Tring Park estate, which included the mansion,

parkland, properties, farms, and a water-driven corn mill

– in all

about 3,000 acres. According to the writings of Tring

historian Arthur Macdonald “having inspected the estate, he

(William Kay) called at the auctioneer’s offices and asked the

price. ‘One hundred thousand guineas’ was the answer, and Mr Kay

arranged a meeting for the next day. After some conversation,

Mr Kay pulled out his watch and said ‘Gentlemen, it is now ten

minutes to twelve. I make you an offer of eighty thousand

guineas, and I must have an answer, ‘yes or no’, by 12 o’clock”.

The offer was accepted at what was considered to be this extremely

low price. William never occupied the grand house himself,

preferring to remain at the centre of things in London, and using

another property in Tring only occasionally. The mansion, the

upkeep of which he deplored, was let continuously to his relatives

and other tenants, including his old Manchester acquaintance, Nathan

Rothschild.

It is likely that William Kay selected Tring in which to invest

because of its proximity to the capital, as well as the potential of

the Brook End site, with its adjacent source of water power.

After his arrival in the town he wasted no time in investigating the

advantages of his new purchase, and within a year, building of the

Silk Mill was under way, in addition to a row of cottages on the

west side of Brook Street. The setting up of the operation he

entrusted to Joseph, and when the local populace nicknamed the

looming five-storey mill ‘Little Manchester’, the Kay brothers most

likely felt they had achieved their objective. With the

business running smoothly and both management and workers in place,

after four years the decision was taken to lease the business to

David Evans’ company (see Chapter 5), but both Kays retained a

financial interest in the concern. When Joseph made his will

in 1834, he bequeathed £190 a year to his executors, to be held in

trust for his children’s education.

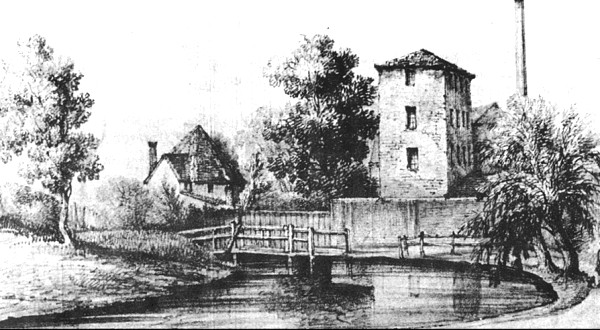

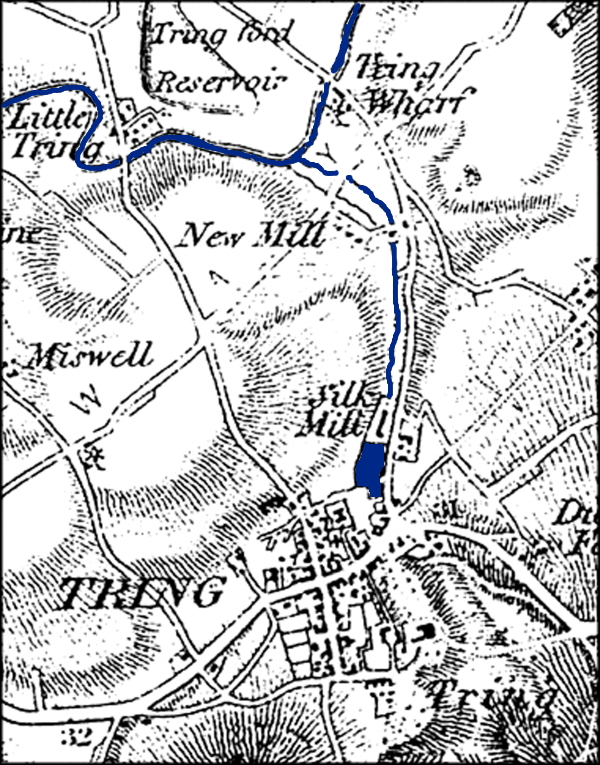

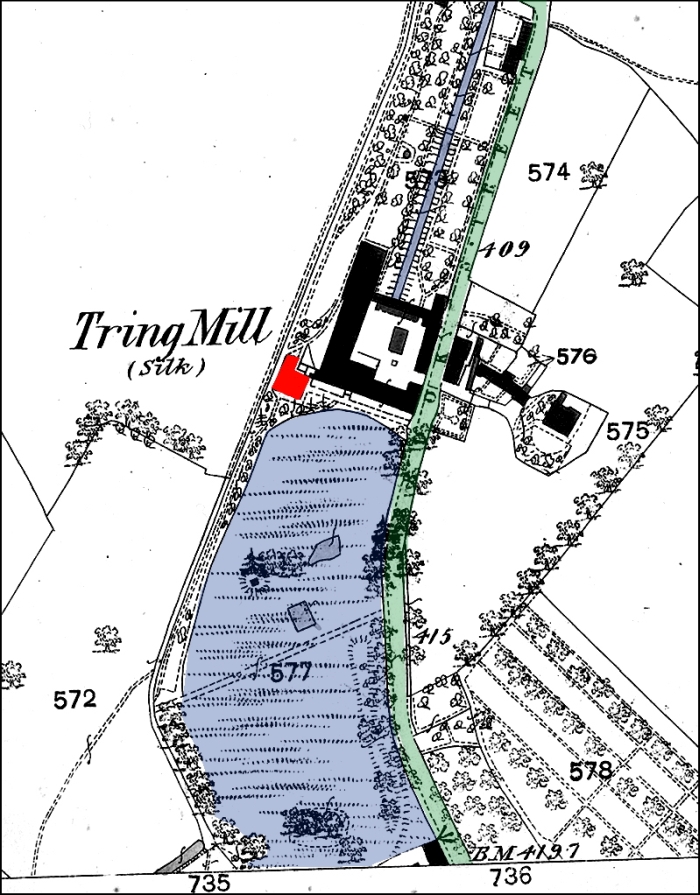

1833 map of Tring, showing the mill pond (blue), silk mill,

and feeder to the Wendover Arm Canal (top of map).

It was a boom time for industry generally, aided by the invention of

the steam locomotive. As the largest land-owner in the Tring

area, William used his influence to ensure benefit to the town in

general, and his own business interests in particular, by appearing

before an Enquiry into the suggested route of the London &

Birmingham railway. It is minuted that he gave evidence in

July 1832 to a Commission of the House of Lords, stating his

opinions very strongly. As the owner of some fields through

which the intended line would pass, he believed the value of his

land would be enhanced and, with other local businessmen, he

contributed financially to the scheme to locate the station near

Tring rather than at Pitstone Green as first proposed. He

stated he had to travel a lot, and when the construction was

finished he wanted to reside at Tring more often. William

claimed he had laid out £30,000 for the erection of a silk factory

and, as fashions change quickly, it was necessary to get goods to

the market as speedily as possible. He also contributed to the

cost of constructing the lengthy road between Tring and its railway

station. His views were not shared by some of the gentry

in the district, and it is possible they made him unpopular.

In any case, William did not live long enough to enjoy this new

wondrous means of transport, as he died in 1838, soon after the

railway reached Tring.

His death was untimely, and the local paper in his native Cumberland

reported that he expired of a head injury after being knocked down

by a horse-drawn cart a few yards from his house in York Terrace.

(In spite of his sad end, it is perhaps fortunate for Tring that he

died before he had time to implement all his ideas for the town.

He had in mind to lay a new road along a route similar to that taken

by the present bypass, the difference being that he probably

intended to demolish the mansion and to develop the surrounding

area.)

|

|

|

Memorial to William Kay, Tring parish church. |

William is buried in the now-neglected Kay family vault in Kensal

Green Cemetery, North London. He left a lengthy and detailed

will which included a very generous legacy to his nephew, Robert

Nixon, who had established the Aylesbury silk factory (see Chapter

10). The Tring Park estate, including the Mill, was left in

Trust for his young son, William who, at the time of his father’s

death, was still a minor and accordingly, for the purpose of the

inheritance, was made a ward of the Court of Chancery. He died

aged 31 in Paris as the result of a fall while hunting; he and his

wife were childless, and the Court ordered that the estate be sold.

After much legal wrangling, it was eventually offered for auction in

1872, to be bought by the Rothschilds.

Reminders of William Kay are still to be found in Tring. A

late-Regency-style tablet to his memory can be seen in the vestry of

Tring Church. This memorial was re-sited during the Victorian

restorations and was placed rather too high on a dark wall.

Nevertheless a female figure, scantily clad in marble drapery, may

be discerned dimly, drooping in heart-broken grief over an urn.

Also in the church, a three-light stained-glass window on the south

side of the chancel was donated as a memorial by Rose Louise Kay,

widow of William junior, and all Mrs Kay’s cottage tenants who

worked at the Silk Mill received as her parting gift a pair of warm

woollen blankets.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 4

The Water Supply

No wide river ever flowed through Tring, nor was there any natural

large expanse of water. However, a thousand years ago, the

amount of water from the several springs rising in or near the town

provided the power for the two mills listed in William I’s Domesday

survey. In Medieval times these springs beneath the ground

supplied water to the monks’ fishpond at Tring Priory, and later to

the town’s public horse-pond in the lowest part of Frogmore End.

Maps from the mid-Victorian era show a chain of ornamental ponds,

complete with weir and sluice-gate, in the gardens of the

now-demolished Frogmore House, and the first chapel in New Mill also

relied on spring water to fill the outdoor pond used when conducting

baptisms by total immersion.

It is fortunate for Tring that the chalk hills in the Wendover

direction act as a sponge for the collection of rain water, which

then seeps down to rest on the harder rock beneath. The

resulting springs flow downhill towards the centre of the town.

Old maps show springs near Miswell Farm, Frogmore, and Dundale, and

it is possible that another underground supply begins in Tring Park

somewhere near the A41. It is thought this could run under the

Memorial Gardens, the A41, The Robin Hood, and the first few

hundred yards of Brook Street.

Tring water courses (blue)

From Andrews’ and Dury’s map of

Hertfordshire, 1766.

When William Kay decided to build his silk-throwing mill in Brook

End, his first concern was how to power the machinery. It was

apparent to him that the flow of water serving the existing corn

mill was nowhere near the quantity needed to drive the sort of

operation he was planning, and like all single-minded entrepreneurs,

he did not let a difficulty of this sort deter him from his

objective. It is likely that William had to work in

conjunction with the operators of the Grand Junction Canal, as that

Company retained powers to obtain water supplies from any brook,

spring, stream, river, or watercourse. Part of the supply

problem had been solved twenty-five years earlier when, in an

admired piece of engineering, the canal company had raised

substantially the bed of Brook End’s ancient watercourse.

William carried this idea further with a decision to divert the

Dundale and Miswell streams to an existing swampy area,

to create a huge mill pond (see below – estimates vary from six to eight acres

in extent) which was to supply water to a wheel beneath the proposed

new Mill.

From the 1877 OS map of Tring, showing the extent of the mill

pond at

that time; also, another feed entering the pond from springs at

Frogmore.

The mill pond is now much reduced in size and the feed shown is

culverted

In 1824 machines suitable for digging the necessary underground

culverts did not exist, and so this gruelling work was carried out

by men on their hands and knees hacking with pickaxes through the

chalk. Their efforts provided channels through which a

sufficient quantity of water passed in the steady flow necessary to

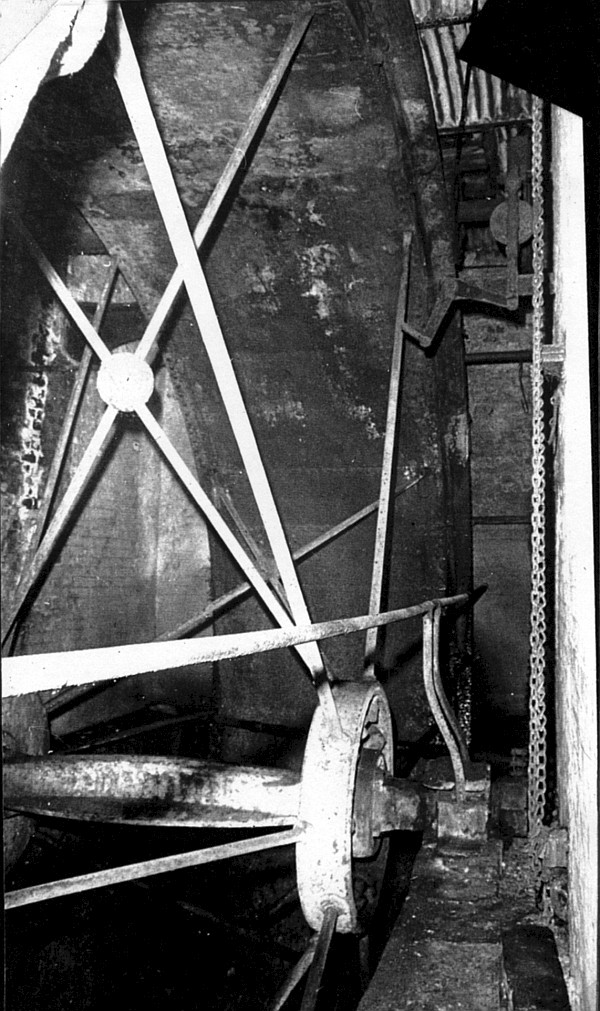

drive the massive 16-hp iron waterwheel. Housed in a chamber

partially below the ground, at 22 ft. in diameter and six feet in

width, it had the distinction of being the largest in Hertfordshire.

The culverts built to divert the waters, although damaged, still

exist and as late as the 1970s it was said to be possible to walk

through from Miswell to the Silk Mill. Beneath the front drive

of the Mill House lie a labyrinth of corridors, and at the rear a

manhole cover gave access to sluice gates controlling the flow of

water to the Mill. This ensured an even supply that remained

constant throughout the year.

The 22feet diameter Silk Mill waterwheel, half of which is

immersed

in the mill stream.

Once the water had served its purpose of sending the machines and

bobbins whirring, it passed through the tail-race into the stream in

Brook Street. This rivulet became known as the Feeder, since

its onward flow to the Wendover Arm of the Grand Junction Canal was

used to top up the volume of water required in the pound of the

Tring Summit; some emptied into the swampy area then known as

Wormwood Lake (now Tringford reservoir).

Underground culvert leading into the Feeder.

A second benefit arising from all this engineering skill and hard

work was improvement to the water supply from the Silk Mill to Tring

Park mansion. Passing through a pipe beneath Pond Close, the

market place, and the main road, water was pumped to a tank or

‘water-house’, an arrangement which continued for some years until

the erection of the Chiltern Hills Water Works at The Crong

above Tring. The auction particulars of 1820 for Tring Park

estate tell us that the whole included “moats and fishponds, with

an engine worked by water which amply supplies the mansion house,

offices, stables, grounds, gardens, and a pond at the north front.

The command of water in this situation is particularly valuable,

being equal to turning a water corn-mill, which is much wanted in

the neighbourhood”.

The Feeder as it looked in the 1920s.

Today it carries rather less water and its banks are much overgrown.

When the Silk Mill closed in 1898 the Tring Park estate maintenance

departments moved to the site, and the water-wheel continued to do

good work, driving the saw-mill used by the carpenters, as well as a

generator which supplied electricity (see Chapter 12).

Most of the mill-pond was drained, and the area planted out as a

well-irrigated site for Lord Rothschild’s orchards, which presented

irresistible ‘scrumping’ opportunities for local boys, whose

expression “going over the boards” meant crossing the wet

ground to reach the forbidden fruit. The remaining portion of

the pond, after years of neglect and vandalism, has been

attractively restored and re-stocked by the present owners of the

Mill House.

The area alongside the Feeder from the Silk Mill to Gamnel, now

retained as a waterside walk, is planted with trees and the stream

is crossed by two ornamental foot-bridges. Sadly, although

this stretch of Brook Street should be valued as the last-remaining

green space in an increasingly built-up and busy thoroughfare, the

stream and shrubbery are often polluted with litter.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 5

David Evans & Company

Tenant of the Silk Mill from 1829

Due to wars, tariffs, and fashions, the silk industry was never

viewed as ‘safe’ for the investment of capital, but for those

willing to take the risk the returns could be enormously profitable.

It was a lucky day for the silk trade when fashion dictated that

voluminous dresses replaced the simple straight lines of Regency

style. Then, any woman, even those in modest circumstances,

aspired to own a Sunday-best silk dress, so precious that it was

often handed down from mother to daughter.

The two men most connected with Tring Silk Mill recognised the great

potential of the silk trade, and it is a coincidence that William

Kay, the founder of the Mill, and his tenant, David Evans, were born

sons of yeoman farmers in rural counties. Both then moved to

London to further their ambitions.

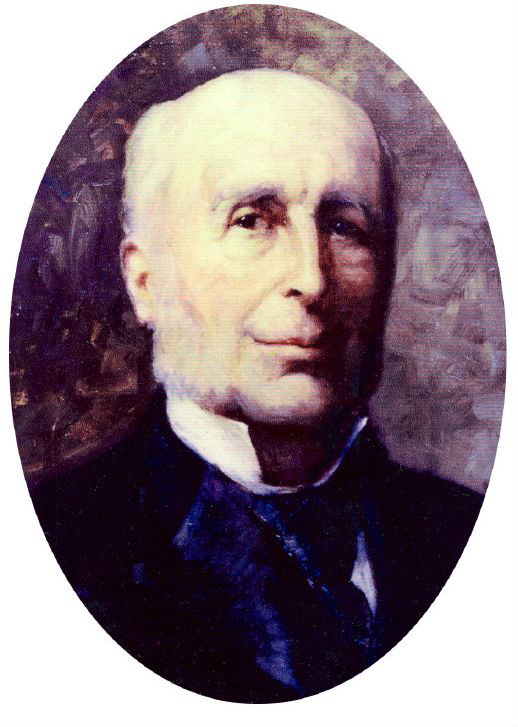

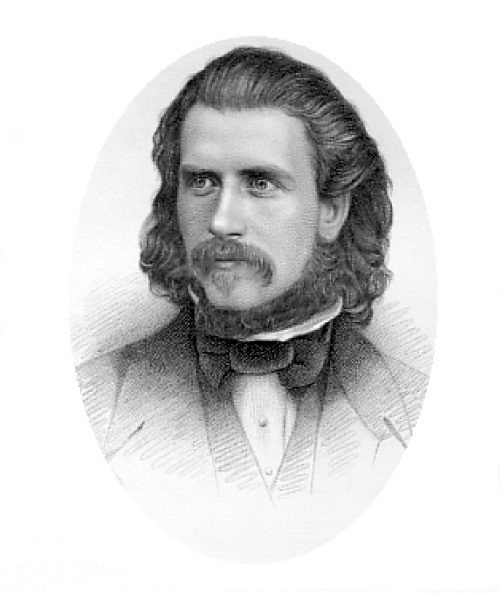

David

Evans (1791-1874)

Brought up near Oswestry in Salop, David established his base in

Wood Street, Cheapside, in the City of London. In entries in

trade directories from 1828 onwards he is described as a ‘Silk

Agent’, ‘Merchant’, or ‘Warehouseman’, and possibly he was a

consignee of Far Eastern merchants who shipped silk fabric to

London, as well as acting as a salesman for provincial manufacturers

in the north of England. Before long he added to his business

interests by undertaking hand-block printing on silk, a complicated

craft requiring great skill and as many as 30 different processes.

His next logical step was to acquire premises specialising in silk

throwing, so ensuring a steady supply of material for his London

operation. Deciding that it would best to base this in a less

expensive area than the capital, in 1829 he signed the lease of

William Kay’s silk-throwing mill in Tring, and bought outright the

stock and machinery. Soon David was able to increase the

output of thrown silk by supplementing the existing water power with

the installation of a steam engine. This factory was shortly

to be augmented by a small weaving operation in Akeman Street, and a

much larger works at Aylesbury (see Chapter 10). Four years

after, he added to his local investments in Brook End by buying land

and building 22 cottages. Later in 1850, he was requested by

the local authority to dispose of part of his land holding as it had

been identified as a suitable site for Tring’s new gas-works.

David Evans never lived in Tring with his family and contented

himself with a ‘temporary residence’ and frequent visits to the

town. Day-to-day control of operations he left to his

managers, firstly Henry Rowbotham and then John Akers (see

Chapter

7). At times not everything went smoothly at Tring and before

long disaster struck. In 1836, the Mill was damaged by a

serious fire and again six years later (see Chapter 6). David,

prudent as always, had taken out adequate insurance cover on the

premises and machinery, and production was quickly restored.

In his portrait, David Evans appears as a thin-lipped shrewd

individual, but this image belies his generosity to Tring on the

occasion of Queen Victoria’s coronation in 1838. Although it

is difficult to know whether this was inspired by benevolence or a

desire to demonstrate patriotism, his lavish expenditure gave his

normally-deprived workers a day they no doubt talked about for the

rest of their lives. On the morning of June 28th the church

bells woke the people of Tring, and a mood of feverish excitement

prevailed. Later came bands, singing, decorations, and

fireworks. The Aylesbury News describes events at the

Mill:

“In the course of the day, David Evans Esq., proprietor of the

Silk Mill, gave a holiday and a treat to 350 men, women, and

children, employed in the factory. The whole company assembled

at the Mill, and walked from thence in procession through the town

carrying appropriate banners, while Old England’s colours were seen

gracefully waving from the top of the factory, the entrance of which

was very tastefully ornamented with shrubs and flowers.

After dinner, which consisted of a good supply of beef and plum

pudding, the health of Her Majesty was given, and most cordially

drank by the whole party assembled, and the favourite old anthem was

sung with the most imposing effect, the voices of some hundreds of

children (who constantly sing while at work in the Mill), producing

an effect seldom given on such an occasion. The whole

celebration was very ably managed by Messrs. Rowbotham and Parker,

assisted in the kindest manner by many of the tradesmen of the town,

who volunteered to wait upon the people at dinner.”

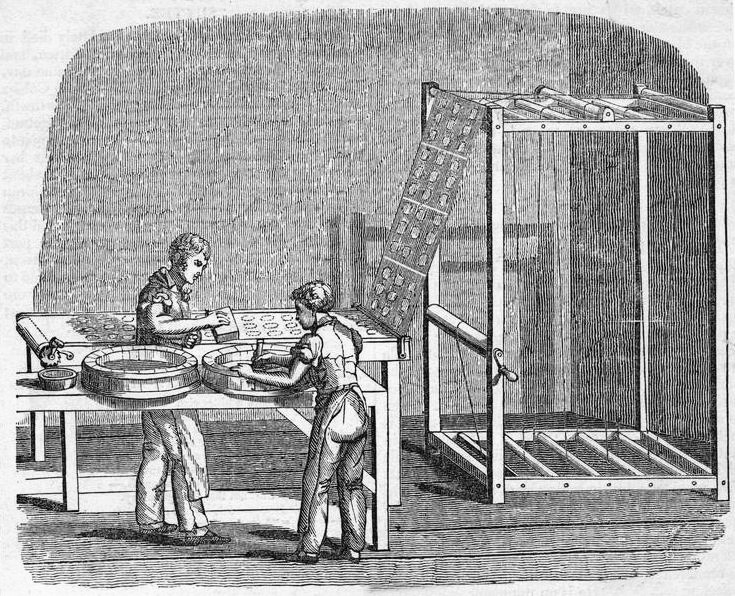

Hand

printing a pattern on silk using a wooden printing block.

As the century wore on, the huge upsurge in demand for printed silk

meant that David Evans was again able to further his business

operations. At Crayford in Kent he acquired a silk- and

calico- printing business established by the inventor Augustus

Applegarth who had run into financial difficulty. The quality

of the unpolluted water of the River Cray proved ideal for washing

the silk and for setting the dyes, a tricky process as too much dye

could rot the fabric. Also, there were broad open fields in

which the silk cloth could be laid out and bleached in the sun.

The latest building technology had been used in constructing

Applegarth’s factory, the result being an iron-framed structure with

a large skylight roof supported by iron columns. This had two

advantages; it admitted the maximum amount of light to the work, and

discouraged industrial spying, an ever-present threat to the

stealing of designs.

The silk printing skills refined in London were put into use at

Crayford, one speciality being the application of Paisley patterns.

These intricate designs originated from Kashmir, and acquired huge

popularity with the Victorian fascination for all things Indian.

Copying and modifying imported originals, textile manufacturers,

including David Evans, were not slow to claim their share of the

lucrative new market, and the works at Crayford became well known

for the production of high-quality silk shawls.

Paisley pattern printing block.

By the 1850s David had earned great respect in the textile world of

the City of London, being one of the founders of the Linen and

Woollen Drapers’ Institution, and also one of its first trustees.

He no doubt enhanced his reputation by taking a stand at The

Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace, where the company was

described as silk manufacturers and printers. The list of

products included:-

Bandanna handkerchiefs, manufactured in India.

Bandannas manufactured at Macclesfield from

Bengal and China silk.

Spun bandannas, manufactured in Lancashire.

Ladies silk dresses.

Table covers.

Registered designs. |

David Evans was then a wealthy man, and fully able to enjoy a

comfortable life at Shenstone, an elegant Swiss-style house on the

hillside above the works at Crayford. This imposing residence

stood in 19 acres of wooded parkland overlooking extensive views of

the Kent countryside, and the 20 rooms provided plenty of

accommodation for his large family of 14 children.

When he died in 1874 at the age of 83, the business passed to the

control of his three sons. All were known for their

philanthropy to their workforce and to local folk generally.

George, the youngest son, entered the Evans business in Cheapside

when he was 18, and remained there until his death at the age of 84.

In 1877 he paid for the refurbishment of the bells which had been

presented in memory of his father to Crayford church.

By the time of David Evans’ death, although still reasonably

profitable, the financial viability of Tring Silk Mill was in some

doubt, due in part to a continuing problem of lack of labour.

The opening of the Suez Canal also contributed, as raw silk from the

East could be sent more easily and quickly to Marseilles. The Mill

struggled on, and it is recorded that David Evans & Co. continued to

meet the annual rent of the premises and cottages in Brook Street

– amounting to over £500

– until, finally, the management was forced

to ask Lord Rothschild to agree to the surrender of the lease.

Shenstone at Crayford.

The Crayford works continued for over a century longer. After

160 years, operations were closed down in 2001 when David Evans &

Co. was described as “the last of the old London silk printers”.

Fifty years before, his private house had been purchased by Crayford

UDC and later demolished; today the grounds remain preserved as a

public open space.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 6

Working at the Silk Mill

Although the mill has been much altered and enlarged over the years,

it is apparent that William Kay was an ambitious builder as

reference to old maps show that his plans produced an extensive

L-shaped structure. Built of brick, five stories high, and

with a small warehouse on each floor, at each level the floors were

supported by runs of evenly-spaced cast-iron pillars, and through

the centre of the building ran a central staircase. The ground

floor housed a dining room for the workers, and offices, one of

which was occupied by Joseph Parker, a key member of staff whose

position today would be described as Chief Accountant.

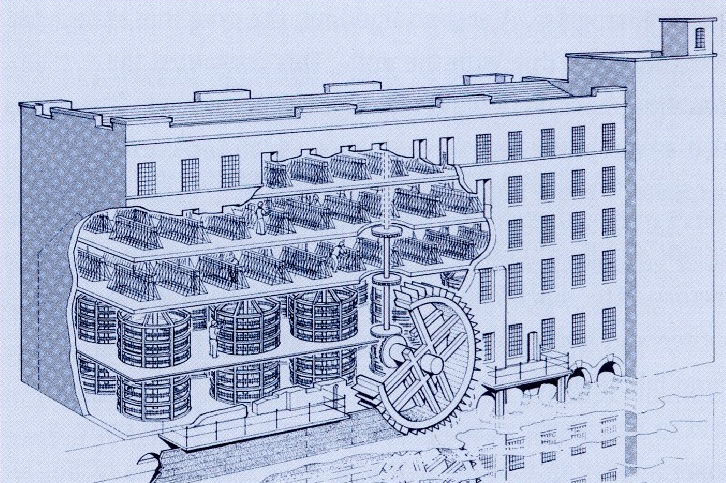

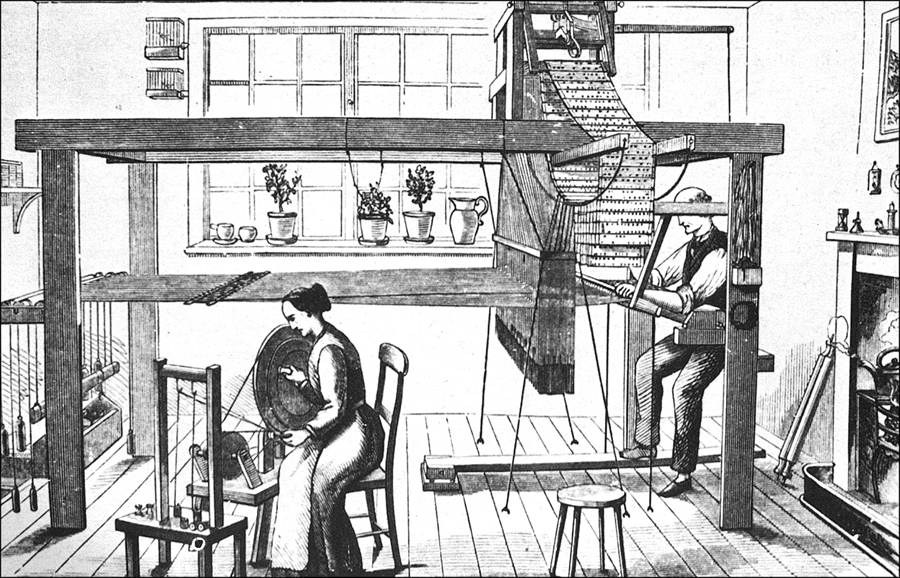

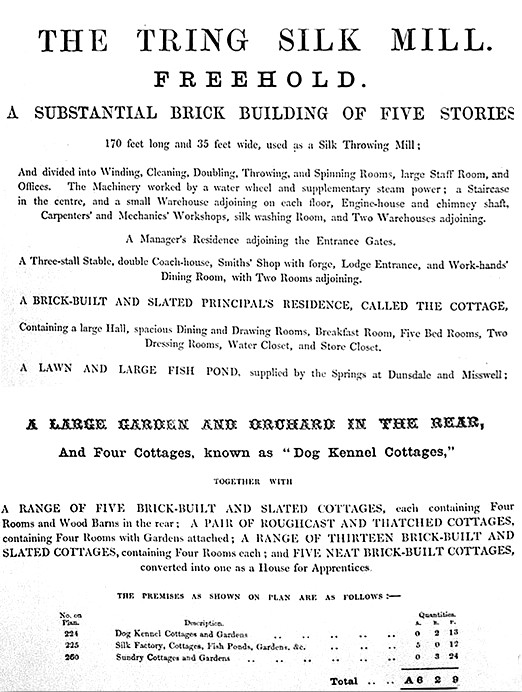

The general arrangement of a water-driven silk throwing mill.

The engine house, approached by an oilcloth-covered stairway, and

the chimney-stack adjoined the main building. Outside were the

carpenters’ and mechanics’ workshops, the silk washing room, and two

warehouses. As was customary, accommodation was provided for the

senior staff: a large house and garden for the Manager (see

Chapter

11), a good-sized cottage, and a lodge house. Other amenities

included stabling for three horses, a double coach-house, and a

smith’s shop and forge.

Descriptions of the numbers employed in the Mill vary greatly, and

fluctuated according to the demand for the supply of silk, and to

agricultural seasonal work. In 1840 a reliable account states that

the Mill had capacity for 500 pairs of hands, consisting of 40 men,

140 women, and 320 children. The superintendents received one pound

a week; the men between 12 and 15 shillings; the average women’s

wages were 5s.6d.; and the children’s between 1s.0d. and 2s.3d.

Skeins of silk imported from China, Italy and Bengal underwent a

complex operation (see diagram) and on each floor workers

performed a different process. After being graded and washed with

soap and water, Winding onto star-shaped frames (known as ‘swifts’)

took place at the top of the mill, where the machinery required

little power to turn the reels; followed by Cleaning where the silk

passed through a scissors-like device which removed the knots and

enabled the size, or denier, to be measured. These processes were

usually carried out by children who had to keep constant watch and

re-join any broken threads immediately. On the next floor came the

Spinning, where the single silken filaments were twisted together up

to 80 times to strengthen them. Then came Doubling, when two to four

filaments were brought together with a slight amount of twist. In

the final stage, called Throwing, the doubled threads were twisted

once again by machine, but in the opposite direction, making the

silk strong and pliable. The finished product, a rope-like yard

called ‘organzine’, was then ready to be stored in the warehouses in

the yard to await transport either to David Evans’ weaving factory

at Aylesbury (see Chapter 10) or to mills in the north of England. The coarser-quality output was sent to Macclesfield and Coventry for

the ribbon trade.

Compared to other mills at that date, working conditions were

considered to be light and congenial. But the rooms were hot, the

machinery very noisy and dangerous, and the working hours long. Adults worked twelve hours a day and the children, controlled by Act

of Parliament, ten. An insidious problem was the risk of contracting

the dreaded ‘ague’, a loose term which covered many different sorts

of fever. This seemed to be particularly prevalent at Tring, and was

blamed on the stagnant water beneath the building, and the proximity

of the mill pond, the vapours of which were described as ‘pernicious

effluvia’.

Visitors to the Mill were not encouraged, less from a desire to hide

the working conditions, but more from anxiety about what would now

be called ‘industrial espionage’. However, with difficulty, an

admission card could be obtained, and one official visitor of 1840

has left us his detailed account. One extract reads - “Tring is

seldom or never without ague, and as the malaria is generally found

to result from stagnant pools, several of which are in the vicinity,

it is to be hoped that, ere long, the proprietors of these sources

of pestilence will evince sufficiently morality and intelligence to

compel the removal of a nuisance so highly dangerous to all the

neighbourhood; actually fatal to some, and deeply injurious to the

lives and happiness of many innocent people. In the mill there are

almost always persons whose haggard looks evince their having lately

been afflicted with this terrible disease ............... The

proprietors of the mill pay Mr Dewsbury, Surgeon of Tring, £20 a

year for inspecting the persons employed in the mill, to insure

cleanliness and freedom from disease: after this evidence, we must

not attribute the presence of the injurious marsh to a want of

feeling in the proprietors, but rather to a want of information on

the subject”. (In fact everyone lacked “a want of information on the

subject” as later it was established that some of the town’s sewage

was leaking into the Mill Pond.) Other health hazards which caused

concern were bronchial problems, glandular swellings, and scrofula

(i.e.

tuberculosis of the neck).

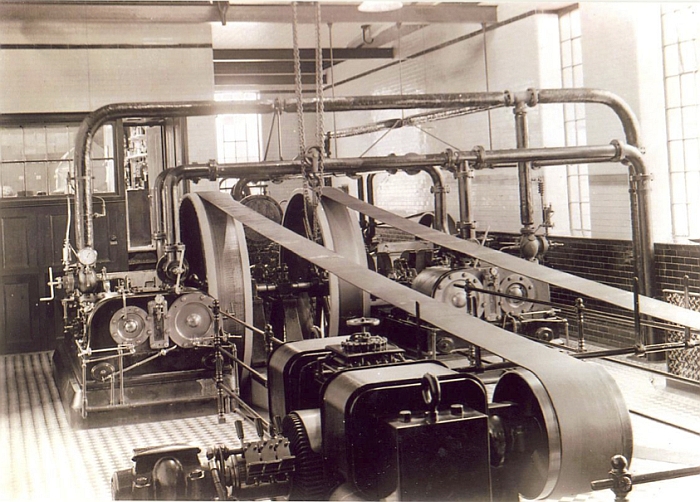

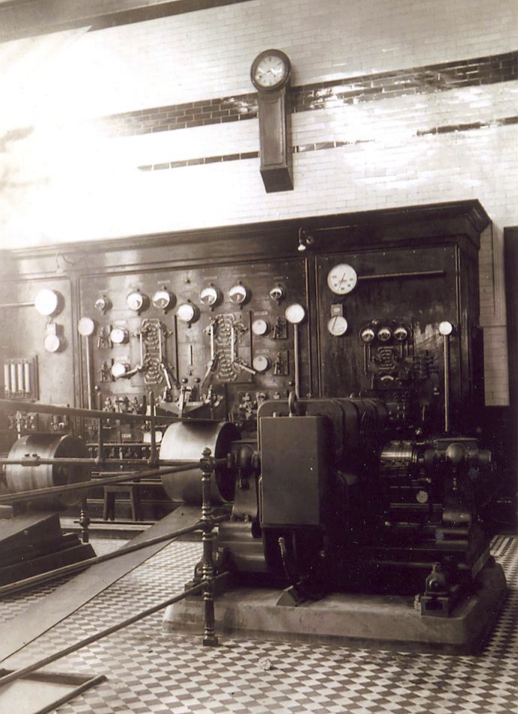

However, the same writer showed excited interest when he reached the

engine room, as he went on to say “There is a steam engine of

twenty-five horse power, of so beautiful construction, fitted up so

elegantly, and taken so much care of, as to elicit from anyone who

sees it the warmest expression of admiration. The room evinces the superintendence of a man of refinement and mechanical taste. The engine

is appropriately called Venus, and was constructed at the

manufactory of Peel, Williams, and Peel, Manchester.” This fulsome

account would no doubt have caused the engine’s experienced minder,

John Rolfe, a justifiable glow of pride.

Interior view of the Silk Mill.

In any silk mill the main hazard was always the threat of fire. Sparks could be caused for any number of reasons - friction from

opening the bales of skeins which could contain nails, stones, dry

grass, or leaves; contact with hard objects; netting covering the

boilers in the drying rooms; and steam pipes. However, none of these

applied as the management’s worst fears were realised in 1836 and

again in 1842, when fires gutted part of the mill building (Appendix

I.).

On both occasions nobody was hurt, and the ample insurance of the

building and machinery covered the many thousands of pounds worth of

damage. Such rare pieces of sensational news were written up with

relish by the editors of the local papers. On the occasion of

the 1836 blaze, it was reported that at

noon the workers left for dinner, and at 1.30 pm. Ruth

Goodson, the housekeeper who lived in the Mill Cottage, saw thick

smoke rising from an upper storey. She instantly gave the alarm, but

soon flames burst from the fourth floor, eventually engulfing the

floor above. Messengers galloped to Aylesbury, Berkhamsted, and

Ivinghoe, and all responded by sending their fire engines, and two

wealthy neighbours (Lady Bridgewater and a Mr Hay) despatched their

private engines. Streams of water from the mill pond were directed

at the blaze.

As it happened, David Evans was travelling from London that same day

to visit his mill in Tring. He arrived on the scene some four hours

after the event, having been forewarned by excited locals of the

drama unfolding in Brook Street. He was in time to see the flames

still rising, and must have grieved to imagine what was happening to

his valuable machinery. The damage was mainly confined to the

winding machines on the top floor, and was not too severe thanks to

the efforts of Robert Harrison. At very considerable risk, he saved

many of the moveable parts, in spite of dodging molten lead raining

down. On a lower floor, two modern machines made of cast metal and

worth about £400 each, were broken by crashing iron ceiling supports

from the floor above, sending the machines hurtling to the

flagstones below. It was established that the fire started in the

lumber loft after some boys had been ordered to remove a stock of

bobbins but, when the dinner-bell sounded, forgot about their

burning candle. The outcome of the fire caused many to lose their

jobs, but production was quickly resumed, and later, through the

medium of the local newspaper, David Evans publically thanked all

those who had rendered assistance.

Only six years later in the early hours of the morning, fire again

broke out, this time in the steam-engine room. Afterwards, the local

paper reported that due to water pumped from the mill pond “most

prompt and efficient means were made to arrest the progress of the

flames”. Berkhamsted and Ashridge fire engines arrived some two

hours later and it was then unnecessary to call others, but too late

to stop the Aylesbury engine. Although the main staircase remained

intact, a total of £6,000 worth of damage was caused which included

the loss of substantial quantities of both silk and coal. One wing

of the building was put out of use, and for a second time resulted

in limited employment and financial hardship to many families.

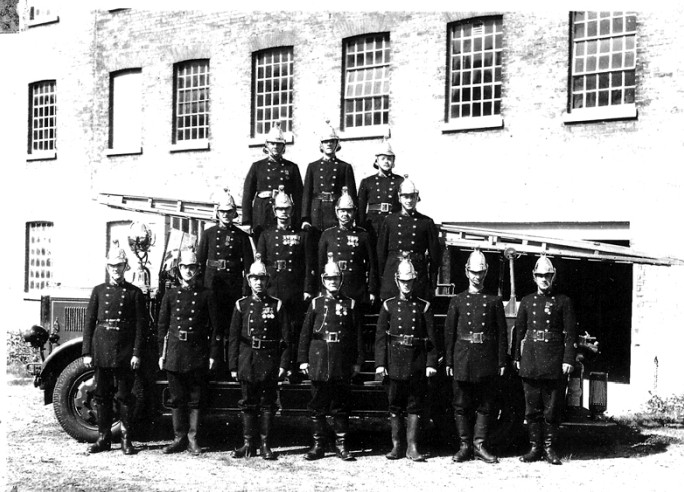

After the second disaster, it was proposed that the Parish of Tring

should move its fire engine, and David readily agreed to the

suggestion to locate it in a specially-prepared room at the Silk

Mill. (It was an arrangement that lasted for 25 years until an

official Fire Brigade was formed, and the engine moved to the more

central position of the Rose & Crown yard.)

Towards the middle of the century David Evans & Co. set up a small

silk-weaving operation at No.60 Akeman Street, which complemented

the printing and throwing factories he already owned and rented.

Never a large concern, it gave work to a number living in the small

crowded streets in the centre of the town; in the Census of 1851, 35

people in Akeman Street are shown as engaged in the silk trade. It

seems that this concern had several different proprietors and

perhaps was not too profitable, as newspaper accounts of 1859 inform

that John Hillsdon, a Tring millwright and engineer, was involved in

a court case in an endeavour to obtain outstanding payment for work

done.

Another short-lived venture was started in Frogmore Street. It was

not a success, as this sad little notice was inserted in the Bucks

Advertiser by William Brown, Tring’s land agent:

FOR SALE

4th August 1858 - Auction under a Distress for Rent and Bill of Sale

on the premises of Mr William Shipley.

Fixtures used in the business of a Silk Throwster. 6 hp

high-pressure steam engine; 10 hp flue boiler with furnace and

brickwork; all running gear driving the Spinning and Throwing Mills

and Winding Engine; Also all furniture of dwelling house adjoining.

Some accounts say it was bought by David Evans’ son, Thomas. In any

case, silk manufacture in Frogmore Street finally ceased two years

later when a notice in the local paper announced “the silk mill is

soon to close” and again offered the steam engine, the machinery,

and utensils for sale.

All in all, it was probably a good thing that William Kay

established the silk industry in Tring, as it gave employment to

many in the town, either directly or indirectly. Working conditions

at the Mill in Tring may have been better, but were certainly not

worse, than for the large majority of those in Victorian England

caught up in the Industrial Revolution and on the bottom rungs of

the social ladder.

The Silk Mill today (reduced to three storys).

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 7

Managers of the Silk Mill

Any enterprise employing 500 workers needs an excellent management

team to return a healthy profit, and no doubt David Evans selected

his senior staff very carefully, especially the Manager. His

choice of Henry Sherratt Rowbotham ensured that, if nothing else, he

had engaged a man with experience of the silk-throwing industry.

Henry came from Macclesfield, then a town containing 120 mills,

mostly all involved in the various processes of silk manufacture.

Born in 1810, Henry moved to Tring during the late 1830s and

occupied a house described as being at ‘West End of Mill’. A

few years later he returned to Macclesfield to marry, and then

brought his young wife, Jane, back to Tring. Usually in those

times it was the custom for the Manager of a factory to live

adjacent to his workplace, but Henry did not occupy the Mill House

in Brook Street. This may have been through choice, or the

fact that the Bookkeeper and Cashier and his large family were

already in residence. Instead, the Rowbothams settled in a

house in the semi-rural smarter ‘West End’ of the town, in a

property large enough for his wife, children, mother-in-law, and

three servants. Jane, who may have had social pretensions, is

described in the Census of 1851 as ‘Gentlewoman’.

The proprietor of the Mill lived 70 miles away in Kent, and it was

this fact that enabled Henry to enjoy such a comfortable lifestyle.

His high salary reflected the complete responsibility for the

day-to-day running of production at Tring; control of the workforce;

and the expectation that he would sort out serious problems.

His pride in his position and his comparative youth is shown in a

letter of 1839, when he wrote to the Aylesbury Guardians of the Poor

-“The report of your Committee, who recently visited the Silk

Mill, was handed to me by Mr David Evans, since he does not

interfere with any regulations connected with this establishment”.

But as will be seen from the newspaper account below, Henry’s

policies sometimes could have unwanted consequences.

His other duties included liaison with local authorities including

the Tring Vestry, which involved matters relating to pollution,

drainage, and the health of the workers. He was expected to

take an active part in civic affairs, and was elected as one of the

Tring Guardians of the Poor serving the Berkhamsted Union.

Disciplinary matters also had to be addressed and, where necessary,

evidence set before the Bench about any employee’s misdemeanours.

A typical case occurred in 1849 when two 16-year olds, Joseph

Copcutt and George Norman, ran away from the Mill. As it was

not the first time this had happened, both received one month’s hard

labour at Hertford gaol. Henry Harris, on the other hand, came

up before a more lenient magistrate and was sentenced to three days’

solitary confinement and only two week’s hard labour for the

unlikely offence of stealing a violin.

Sometimes a far more worrying incident arose which the Manager had

to treat with the utmost seriousness. Mary Ann Beard, a pauper

child from St. Margaret’s, Westminster, complained that she had been

assaulted by an elderly male worker. A lengthy correspondence

followed between Henry, the Guardians, and eventually the proprietor

of the Mill. The outcome was a court case (which David Evans

complained had cost him £53 in prosecution costs) and the man spent

four months in gaol and, although formally acquitted, was dismissed

from his employment of 25 years. Following this episode the

mill girls were allowed to leave for dinner 10 minutes ahead of the

other workers, and their surveillance was increased.

Henry Rowbotham appears today as a character from the pages of a

novel by Charles Dickens. He employed stern discipline in the

Mill; he visited the Governors of London workhouses to negotiate the

allocation of pauper children; he travelled to Aylesbury and

Berkhamsted to carry out the same function there; and at times he

personally inspected the children and made his selection on the

grounds of their “strong constitutions, free from disease and

strong in limbs, particularly about the ankle joints”.

(The latter was important, considering that they were expected to

stand at their work for up to 10 hours a day.) However, it is

likely that his rule was not as harsh as that of his counterparts in

the mills of northern England, where labour was more readily

available and expendable, and beatings were commonplace. Even

so, the following account appeared in the Bucks Herald of 9th

November 1839:

AYLESBURY UNION. – A report having

reached the Board of Guardians, that four lads belonging to this

union, employed at the Tring Silk Mill, had been beaten with too

much severity by Mr. Rowbotham, the superintendant of the mills, the

boys, and the woman with whom they lodged, were brought before a

full Board on Wednesday last, when a thorough and patient

investigation of the facts took place.

It appeared from the evidence of the lads that they had run away for

the second or third time from their work, and were absent all night;

that on their return, Mr. Rowbotham made them take off their

smock-fronts and jackets, and then beat them with nut (hazel)

sticks, about the thickness of half and inch in diameter

– five of which he broke about

them, and then used the strap –

they were much marked, but in only one case had blood been drawn.

Three of them, however, did their job as usual, the youngest of them

played at leap-frog the same afternoon. One of them was laid

up for one day with the bowel complaint, but resumed his employment

the next morning.

The woman at the lodging house, told them on their return, that

their flogging “served them right.” One of them repeated her

remark, after she had seen one of the boys stripped

– the other two thought that the

lads were more severely beaten than they had seen lads before; but

they were lads very difficult to manage and keep in order.

On the conclusion of the investigation, a guardian moved that “the

boys were too severely beaten;” but on a division the motion was

negatived.

And this from the Bucks Herald, 17th

April 1847:

THURSDAY, APRIL 15

(Before the Rev. J. Williams.)

George Newman and Joseph Copcutt, two lads, about 16 years of

age, were charged with running away and leaving their employment at

the Silk Mills, at Tring. Proof of the offences being given,

and it further appeared that this was not the first time they had

been guilty of the same offence, they were committed to Hertford

Goal for one month to hard labour.

Like most Victorians, Henry experienced great personal grief.

Within the space of ten years, he lost two of his five children, his

young wife, and his mother-in-law, leaving him to raise the three

surviving children with help from an elderly live-in governess.

On his retirement, he moved to Reading to be near his married

daughter, but Henry was at least spared the knowledge of the tragic

end of his younger daughter who was drowned off the coast of New

Zealand in that country’s worst-ever shipwreck. This occurred

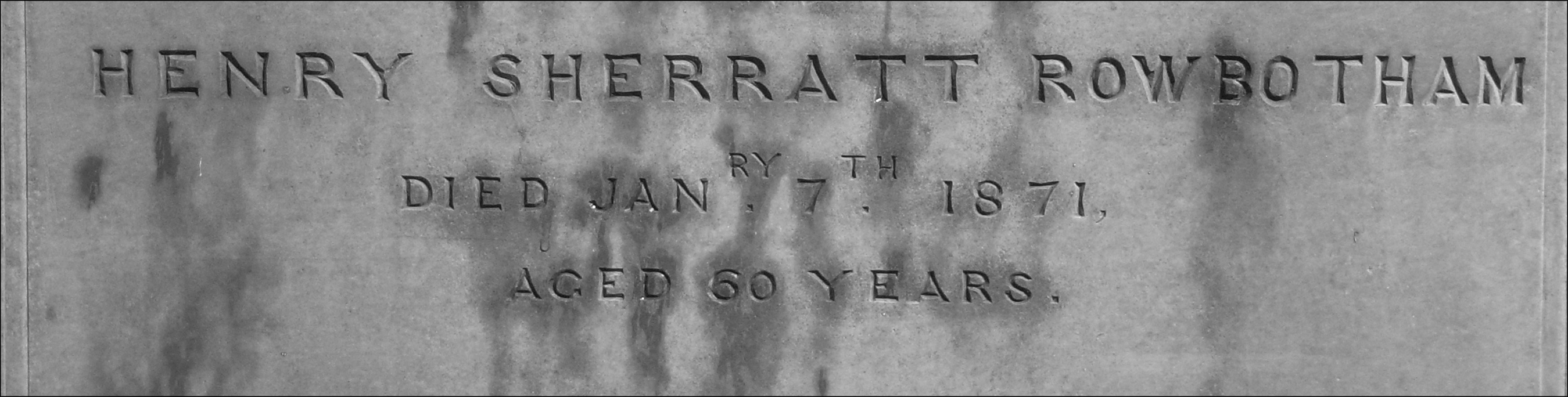

shortly after he died in 1871, when his body was returned for burial

in the Rowbotham family vault at Drayton Beauchamp churchyard.

The cortège travelled slowly from Tring Station through the length

of the town and, as was the custom of the time, most tradesmen and

shopkeepers lowered their window shades as a mark of respect.

Grave of Henry Rowbotham, St Mary the Virgin Church, Drayton

Beauchamp.

The position of manager at the Silk Mill passed to John Akers,

another Macclesfield man, who during his time in Tring was to see

many changes to the old order. By that date the system of

binding apprentices from the London workhouses was over and,

although paupers were still used, other choices of available

occupations meant it was often a case of taking whoever was

available.

Three years after John took over, David Evans died and the ownership

of his various business concerns passed to his sons. In

England the silk industry was starting to decline, and it was only a

matter of time before the inevitable surrender of the lease of Tring

Silk Mill to the new owner, Lord Rothschild. During these

difficult years, John was retained as Manager and, in addition to

the problem of labour shortage, he had to weather some stormy

dealings with Tring local authorities. Disputes started when a

request was made to the Mill to give up the right to extract water

from the stream, and to agree instead to the construction of a

reservoir for water storage in front of the premises.

Brook Street c.1870s (Robin Hood public house on the left).

For many years after the Mill was first built, Brook Street was

still known as ‘Brook End’. Lined with small cottages, the

road was little more than a country lane, overhung with trees, and

no doubt muddy in the winter months. It meandered down towards

New Mill to join with Wingrave Road, and then on to the corn mill at

Gamnel. In the middle of the century, Tring Council decided

upon a plan of action for improvements which included road-widening,

better drainage, and once the problem of leaking sewage had been

identified, provision of a sewer. It was not long before

concerns about the effects of these works on the water level in the

mill pond led to increasingly acrimonious meetings between John

Akers, Lord Rothschild’s agent, the Canal Company and the Solicitor

representing the Tring authorities. The latter received a

letter from John (which he later regretted) beginning and ending:

|

“Tring Mills

March 23rd 1888

Dear Sir,

I have your letter of yesterday

– when I require your

advice for my ‘future guidance’, I may ask you for it

....................... Some portion of your letter

assumes the nature of a threat; if meant as such,

I treat it with contempt.

Yours truly,

J. Akers |

After various Injunctions and Appeals, the matter of Tring’s water

and sewage problems eventually ended up in the Court of the Lord

Chancellor, when a decision was made that most likely completely

satisfied none of the parties involved.

In spite of a far from smooth working life, John Akers enjoyed the

time spent with his family at the Mill House, where the three

youngest of his five children were born. He remained there until his

retirement to Aylesbury, where he died at age 76 in 1906. It

was the end of an era, and Tring’s industrial past as ‘Little

Manchester’ would soon begin to fade into the history of the

locality.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 8

Child Labour

The story of the use of child labour in the mills of Britain is

bound up with the role of the Poor Law and the workhouse system.

Maintenance of the poor was expensive, and a prime aim of the

Guardians of the Poor in every town was to recoup part of the cost,

lessening the burden on local ratepayers. Savings were made

possible by binding workhouse children in apprenticeship to the mill

and factory owners. As the century wore on, some of those with

a social conscience began to protest at the system, and by the 1830s

and 1840s various Factory Acts were introduced. However, as

child labour was considered essential in the manufacturing process

of silk, this legislation did not apply to them, and they had to

wait another twenty years to obtain a degree of protection in the

workplace.

The view held by Joseph Grout (then renting Tring Park mansion from

the Trustees of William Kay) was typical of other silk mill owners.

He gave evidence to a Factories Enquiry Commission and stated that

he saw no objection generally to restricting the working hours of

children under the age of 13, but “ ..... the measure is quite

uncalled for with regard to the silk trade, as the labour of

children is so extremely light, for it is only to watch a thread,

and tie it when it breaks. They have to walk backwards and

forwards which is only gentle exercise.”

The Manager at Tring, Henry Rowbotham, stressed that children should

start work at an early age so they would be worthy of their hire

later on, and that they must have done nothing previously as their

hands would otherwise be too rough. Girls were valued more

highly than boys, who were usually discarded by the age of 15, and

this preference was reflected in the girls’ wages, as they were paid

3d. a week more than the boys. It was felt that they obeyed

orders more readily, their reactions were better co-ordinated, and

their small nimble fingers could swiftly fill the bobbins and join

broken threads.

One tragic victim of the system was Lucy Marshall, born in Harrow

Yard, Tring, in 1848. Her drunken father deserted his wife and

four young children, forcing the family to be sent to the

Berkhamsted Union workhouse. After a few years Lucy and her

brothers returned to Tring to work in the Silk Mill, and she

recounts the terror of her first day, when she was overwhelmed by

the noise and flying wheels. She was still too small to

properly reach the machines, and stood on what was called a ‘wooden

horse’. Her temporary home in Brook End added to her woes, as

the couple she lodged with quarrelled, drank, swore, and did not

feed her sufficiently. The Marshall family’s harrowing

sequence of events continued, when the mother, still in the

workhouse, languished with cancer for three years, and Lucy’s oldest

brother absconded from the Mill. After many unpleasant

experiences, Lucy left the Mill at thirteen years of age and

continued to battle her way through a life dogged with difficulties

and sadness.

At that time, Lucy’s story was probably no more or less different to

dozens of others, but it may be that the pauper girls from London

enjoyed better conditions than some local children living in nearby

lodgings. David Evans had purchased five cottages in front of

the Mill in Brook End and these were converted into a dormitory to

accommodate the apprentice labour force. A married couple, the

Master and Matron, supervised this building and were responsible for

the welfare of the young inmates. Regular inspections by the

Board of Governors from St. Margaret’s and St. George’s workhouses in

London ensured that the boarding arrangements met with approval.

St. Margaret’s Workhouse, Westminster.

However, it is now not really possible to say just how satisfactory

or otherwise were the conditions for the children. Any

criticisms resulting from the inspections were most likely

moderated, as the Governors avoided any situation where paupers had

to be returned to their workhouse. So generally the overseers

found everything favourable, and the girls in excellent health, but

sometimes they had to admit that the sleeping arrangements were not

impressive - the bedding scanty and not clean enough.

Former dormitory accommodation for the workhouse children (Brook St.

to the left).

Consideration of the weekly diet of the children concluded that the

following was adequate and, although monotonous, the amounts

probably compare favourably with the diet of the local populace:

Daily – Breakfast l lb. Bread, 1 pint milk (sufficient

to last the day)

Dinner 6-oz. Meat cooked with vegetables

(4 days a week)

Soup or Rice or Suet Pudding

(3 days a week)

No Beer

Supper 3-oz. Cheese

(no sweetened food or any sort of fruit) |

In spite of the approval of the workhouse inspectors, it may be that

the above did not always apply, as an incident reminiscent of Oliver

Twist occurred at the Mill when the Berkhamsted Union reported that

a young apprentice, Elizabeth Gibson, had complained about the food.

She stated that there was only bread and butter and no milk, and

that meat was served infrequently and then often inedible. Mr

Burnett, the Master, allegedly grabbed her, dragged her by the hair

across a cobbled yard, and locked her in an outhouse for two hours.

An enquiry found this, and other aspects of his behaviour,

reprehensible.

Working hours for everyone were long, but sometimes varied according

to the current demand for silk. When the Mill first opened the

working day was about 12 hours, later reduced to 10, with nine hours

being worked on Saturdays. Children under the age of 11

supposedly did seven hours plus three more for ‘schooling’.

The apprentices were roused from their beds at 5 a.m. to be ready at

their machines half an hour later, and 30 minutes were allowed for

breakfast at 7 a.m. and an hour for dinner.

Children working in a silk mill.

The one day of rest each week saw little fun for the apprentices, as

the Mill Manager, assisted by the clergymen of the Parish, was

expected to enforce strict observance of the Sabbath. Both

Sunday School and church services were attended twice and, as a

treat, special entertainment was provided on Holy Days.

Occasionally there was a red-letter day, when some local worthy

would arrange the venue and food for a sit-down meal.

The girls must have presented a quaint sight as they filed to church

from their lodgings in Brook Street. In summer they wore a

cotton print dress and a lilac print cape, covered in the winter

months by a shawl. These clothes (which after their day’s work

the girls were required to keep in good repair) were complemented by

good strong petticoats, thick nailed boots, and a coal-scuttle

bonnet. Two complete sets of outfits were supplied each year,

together with a new Bible and a Prayer Book. One early account

of conditions inside the Mill claimed that the children were taught

to sing hymns as they worked, and to put especial energy and piety

into the tunes if visitors were present. To some extent this

practice continued, as local folk passing along Brook Street

reported they could hear singing coming from inside.

It is difficult to assess just how much education the children

received. Under the Health & Morals Apprentices Act 1802 (42

Geo III c.73), all those under 11 years of age were required to

attend school for half the day, and some sort of school had been

established by the first Manager, which supposedly benefitted not

only the children at the Mill but also local infants. But as

late as 1865, the Berkhamsted Guardians were complaining to his

successor on this point. They stated that “there does not

seem to be any part of the day set apart for instruction or

amusement”, eliciting the response “we are going to keep up

or add to the education of the children by setting apart several

evenings a week for writing and reading”. Perhaps matters

in this respect did improve, as later accounts report that the girls

from the Silk Mill joined with pupils from Tring School in singing

at fund-raising concerts.

Although unwanted children were removed from the Berkhamsted

workhouse, the Guardians were never entirely happy about the

arrangement, and protested every time labour was requested for

Tring. Their argument was that the wages paid were so low that

the paupers often still needed to be supplemented with Poor Relief.

The authorities were also well aware that it was difficult to make a

living as an adult Silk Throwster and few stayed in Tring after

their apprenticeship had run, so the worry remained that they might

return to the workhouse and revert to their poverty-stricken status

as a continuing charge on the Union. This possibility (among

others) also concerned the guardians of the St. Margaret’s

Workhouse, Westminster [see Appendix].

It seems odd that the Mill Managers did not ask the Tring workhouse

to help with the supply of child labour, but it is possible that the

dominance of the straw-plaiting industry might explain this.

The Tring Workhouse is known to have had a furnished plait room, and

this occupation could be said to be more congenial than mill work,

as at least it did not impose too much restraint on the liberty of

the individual.

For those who worked in the Mill during their formative years, the

destructive experience branded itself on their character. In

the following chapter, evidence of this is clearly shown, and

eloquently described, in the words of one such unfortunate lad.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 9

Gerald Massey

(1828-1907)

(Child Worker at the Silk Mill and later known as

‘The Tring Poet’)

Still all the day the iron wheels go onward,

Grinding life down from its mark;

And the children’s souls,

which God is calling sunward,

Spin on blindly in the dark. |

The above words from Cry of the Children were written by

Elizabeth Barrett Browning and clearly mirror the experience of the

young

Gerald Massey, when at the age of eight years old he was sent

to work in the Tring Silk Mill. Born in dire poverty in a stone

hovel at Gamnel Wharf and largely self-educated, he went on to

achieve some renown in Victorian times with his early poetry, later

prose work, and his lecture tours in Britain and America.

Gerald’s father worked as a boatman at the flour mill at New Mill,

and his paltry wage forced him, probably with reluctance, to send

his older sons a short way down the road to the Silk Mill. It

was a wounding time that Gerald never forgot, and one that shaped

his radical opinions and outlook for the rest of his life.

Written in later life, the following description of his childhood

has been reproduced many times, but it is worth quoting again.

The brief and bitter summary speaks for all the children at the Mill

who would, most likely, have given similar voice had they possessed

Gerald’s literary talent:

“Having had to earn my own dear bread by the cheapening of flesh

and blood thus early, I never knew what childhood was. I had

no childhood. Ever since I can remember, I have had the aching

fear of want, throbbing in heart and brow. The currents of my

life were early poisoned ... I look back now in wonder, not that so

few escape, but that any escape at all ... so blighting are the

influences which surround thousands in early life, to which I can

bear bitter testimony.”

His release from this detested employment came after the disastrous

fire of 1836 (see Chapter 6). Gerald was one of the children

who stood in Brook Street and watched with high excitement and

pleasure as the flames shot skyward, not realising the grim

financial consequences for his parents. Afterwards, to make

ends meet, he was forced to take up the local cottage industry of

straw-plaiting, less arduous than mill work, but still a stifling

occupation for a spirited young boy.

In spite of the Massey family’s dismal life, Gerald’s mother had

managed to instil Christian values in her sons, and to see that

Gerald was taught to read well. When he was fifteen, he was

able to escape from Tring and seek his fortune in London. Once

there, his poetic talent was soon recognised by, among others, some

leading members of the Chartist movement. It is not surprising

that his background encouraged him to take up the cause with

enthusiasm, and soon he was editing a radical publication.

Gerald’s later life was interspersed with problems, tragedy, and

lack of money. None of it deterred him from writing copiously, and

even at the end of his life, he was labouring on a great work

expounding his theories about ancient Egypt.

An 1856 poem of his, entitled Lady Laura, tells the story of a

wealthy lady who takes pity on the children working in a nearby silk

mill. She plucks one man from the mill, is kind to him and his old

mother, and the couple fall in love and eventually marry. (This is

surely a flight of fancy, as it is highly improbable that anything

so romantic ever occurred at the Mill in Tring.) In the account of

her life, Lucy Marshall (see Chapter 8), who

worked at Tring Silk Mill along with her young brother, mentions

that he “was put to lodgings with the man who used to ring the

Mill bell”. This feature of the children’s working life

impressed also itself on Massey’s memory,

for in his Lady Laura he also mentions the mill bell:

|

Pleasantly the Chime that calls to Bridal-hall or Kirk;

But Hell might gloatingly pull for the peal that wakes

babes to work!

‘Come, little Children,’ the Mill-bell rings, and

drowsily they run,

Little old Men and Women, and human worms who have spun

The life of Infancy into silk; and fed Child, Mother,

and Wife,

The factory’s smoke of torment, with the fuel of human

life.

O weird white face, and weary bones, and whether they

hurry or crawl,

You know them by the factory-stamp, they wear it one and

all.

The Factory-Fiend in a grim hush waits till all are in,

and he grins

As he shuts the door on the fair, fair world, and hell

begins!

The least faint living rose of health

from the childish cheek he strips,

To run the thorn in a Mother’s heart: and ever he

sternly grips

His sacrifice; with Life’s soiled waters turns his

wildering wheels;

And shouts, till his rank breath thicks the air, and the

Child’s brain Devil-ward reels. |

It is likely that Massey retained few fond memories of his

birthplace, but he did return over the years to give lectures in

Tring’s Commercial Hall and its Assembly Rooms; he also

presented copies of his books to the Tring Mechanics’ Institute.

He would probably be the first to appreciate the irony of the way

his native town remembers him, as a block of cream-rendered luxury

flats, built in 2004 and sited almost opposite the hated Silk Mill,

is named Massey House. What might have pleased Gerald more was

the Poetry Competition named in his memory. Open to all pupils

of Tring School, the theme for 2008 was Working in Tring Silk Mill

in the 1800s and the panel of judges awarded first prize to 15-year

old Abbi Brown for her poignant poem entitled:

|

FIFTEEN PENCE A WEEK

Red-raw hands shield dusty eyes

Weakly raised to dream-laden skies

Invisible hands stifle silent cries

For fifteen pence a week.

Far from family, far from home

Back in the workhouse, never so alone

Small hands shake, starved stomachs groan

For fifteen pence a week.

Winding, cleaning, all day long

Beyond the bars, the sun shines strong

Scarce a whisper, scarce a song

For fifteen pence a week.

Enveloped in shadow Kay’s henchmen lurk

One fumbling finger brings shouts from the murk

“You’re worthless! You’re nothing!

Now get back to work!”

And to fifteen pence a week.

We’re ‘civilised’ now; we know that it’s wrong

To force children to work and cut short their song

Locked in a factory, all the day long

For fifteen pence a week.

And yet we go shopping, and yet we still buy

Clothes made in China by children who’ll die

Once it was English and now it is Thai

Paid fifteen pence a week.

The problem remains, though the years

have gone by

We don’t want to know, and we’re living a lie

We’re thrilled by the prices and don’t

the question why

It’s that fifteen pence a week.

Not four feet tall I stand, and yet

My bones are aged from physical debt

My childhood is gone, and my future is set

At fifteen pence a week.

I can’t tell the time and I can’t tell the date

I’ve not been to school, and now it’s too late

But I hope that in heaven they’ll open the gate

For my fifteen pence a week. |

|

Like almost everyone, towards the end of his life Gerald Massey

sometimes thought back to his youth and the days when he departed

Tring to work in London. The poverty and cruelty he saw in the

city impressed itself on him to such an extent that, years later, he

recalled one aspect in a poem he wrote for his granddaughter.

Always sympathetic to suffering, whether of people or animals, he