|

|

|

Since the time of Edward the Confessor, English laws have been drawn up

that aim to deter road crime; as described in Chapter 1, very often the

law of the time appeared to be more concerned with crime prevention than

road maintenance. But no amount of legislation could deter those seeking

quick pickings by robbing travellers. They came in two broad varieties;

robbers mounted on horseback were ‘highwaymen’, while those who went

about their business on foot were ‘footpads’.

The Hollywood image of a highway robber is that of a romantic figure,

mounted on a black horse sporting a pair of flintlock pistols and

wearing a mask, a tricorne hat and a swirling cape. But this was far

from the truth. Highwaymen were often unscrupulous ruffians who showed

small mercy for their hapless victims. Surprisingly the commands “Stand

and deliver!” and “Your money or your life!”, or variations of them,

are not the product of film script writers, but crop up in trial

reports of the 17th and 18th centuries.

In an age when there was no regular police force to detect crime, the

approach taken was instead to deter it through the harshness of the

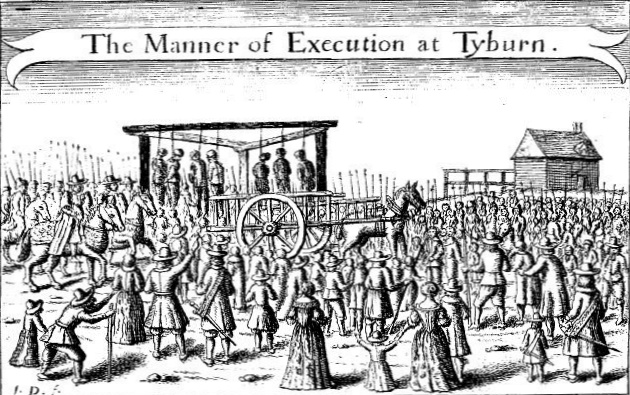

penalties imposed on those convicted. [1] The offence of highway robbery

was one such crime for which the penalty was the gallows, which is where

the most notorious English highwaymen ended their lives ― a common place

of execution for London and Middlesex was the ‘Tyburn Tree’,

today the site of Marble Arch. [2] Yet in harsh times the temptations to

acquire comparatively easy money were great, and robberies on the King’s

Highway were not uncommon, the roads radiating from London being

favourite haunts.

The following are examples of press reports of robberies in the Tring area:

“Last Friday night, the post-boy who takes the mail from Aylesbury to

London, was stopped between Berkhamsted and Hemel Hempstead, and robbed

of the Aylesbury, Winslow, Tring, Wendover and Berkhamsted bags; after

which the robber tied the boy’s hands, blindfolded him, and fastened him

to a gate, and then rode away with the mail and horse.”

Northampton Mercury, 4th June 1791

“Sunday morning, about half past three o’clock, as the post-boy was

conveying the mail from Hemel Hempstead to Aylesbury while he was

delivering the London bag at the post office in Tring, the mail was

stolen from off his horse, containing the Aylesbury and Winslow bags of

letters, and carried to the distance of about 300 yards. The robber was

immediately pursued by the mail-boy and taken. The sack and the

Aylesbury bag were both cut open, and the letters taken out. The robber

is fully committed to Aylesbury Gaol to take his trial Monday next at

the assizes at Hertford.”

Northampton Mercury, 8th March 1794

|

|

|

Commemorative stone placed by the

Boxmoor Trust in 1904 |

The best-known highway robbery in the Tring locality is well documented.

James Snook, a seasoned highwayman, encountered John Stevens, the

post-boy carrying letter bags from Tring. Snook rifled the bags and made

off with the money which amounted to £80, dumping the letters in a

field:

“The Post-boy carrying the mail from Tring to Hemel Hempstead, was stopped near Bourne End in the Parish of Northchurch at about 15 minutes past 10 o’clock last night, by a single Highwayman, mounted upon a dark coloured grey horse who took from him five bags of letters. There is good reason to suspect that one James Snook committed this robbery ……… Whoever shall apprehend and cause to be convicted the person who committed the said robbery, will be entitled to £200 reward over and above the reward given by Act of Parliament of apprehending Highwaymen. By command of H.M. Postmaster General, Francis Freeling, Secretary.”

The London Chronicle, 18th May, 1801

“On Sunday last was committed to Marlborough Bridewell, by the Rev.

Dr. Popham, James Snook charged on suspicion of robbing the Tring mail

May last. He was apprehended on Saturday afternoon in Marlborough

Forest, by Mr. Wm. Gale, of Great Bedwin, assisted by one of his

neighbours and some postboys belonging to Mr. Cooper, of the Bear Inn at

Hungerford, who are entitled to the thanks of the public in general, but

in particular, to those of the farmers and others who had to return home

that afternoon through the Forest. Snook when taken had a brace of

very handsome pistols loaded, in his possession, and a handsome cased

silver watch, maker’s name Egerton and Son, London, No. 2275, with a

steel chain and cornelian seal, a lion rampant engraved thereon, have

since been found at a public house near the spot where he was taken,

which he had left there. He is suspected of having committed

divers highway and other robberies in and about London and in many parts

of the country. Intelligence of Snook’s apprehension was

immediately transmitted to the General Post-Office, by the Postmaster of

Hungerford.”

Reading Mercury, 7th December 1801

“James Snook the highwayman was indicted for feloniously assaulting on

the King’s Highway John Stevens the post-boy who was employed to convey

the letters from Tring to Hemel Hempstead, putting him in fear of his

life, and taking from him the said letter bags. A considerable number of

witnesses were brought forward on the part of the prosecution, by whom

several of the notes that were taken out of the letters in the bag, were

traced up to the prisoner. It formed such a mass of circumstantial

evidence that the Jury without hesitation found him guilty. Justice

Heath in his address to the prisoner, previous to passing sentence on

him, told him that his crime was so destructive to Society, that he must

not flatter himself with a thought of pardon. James Snook was therefore

sentenced to execution on the morrow, near the place where the robbery

was committed.”

The London Chronicle, 11th March 1802

“The execution of James Snook the Highway took place at Boxmoor. The

sentence was that he should be hung and his body gibbetted at

Northchurch the scene of his crime, but the inhabitants of the district

protested to such an extent that the gallows were moved to Boxmoor. Journeying from Hertford gaol on the morning of March 12th Snook was

given a final glass of ale at the Swan Inn, at the corner of Box Lane. Snook behaved with remarkable courage, and called out to the multitude

of people that were running to the scene of execution ‘Don’t hurry,

don’t hurry, there’ll be no fun till I get there’.”

The London Chronicle, 12th March 1802

Exactly where Snooks was buried is unknown, but in 1904 the Box Moor

Trustees placed a headstone on ‘Snook’s Moor’, and added a footstone

in 1994.

The white-painted headstone (pictured) can be

seen in the middle of one of the fields adjacent to the main road over Boxmoor

Common.

Another notorious local highwayman was Richard “Galloping Dick”

Ferguson. Ferguson, with his partner Jeremiah Abershawe, raided

the area around London during the late 18th century. Following

Abershawe’s capture and execution in 1795 ― he was hung in irons ―

Ferguson continued on his own successful career as a highwayman for

another five years until, following the robbery of a coach in Aylesbury,

he was captured by the Bow Street Runners. Ferguson was publicly

executed soon after his trial at the Aylesbury Lent Assizes in 1800.

Other highwaymen hanged at Aylesbury include William Maund in 1693 and

Joseph Radlay in 1784. Another, one Summers, was executed at

Aylesbury in 1694. Before his hanging he is said to have sold his

body to a surgeon for dissection, an early example of what today would

be described as trading in a futures market. Having received eight

shillings, in the words of a ballad of the time. . . .

“So . . . . was the money paid, and put in Summers’ hands, But strait he drank it out in wine, until he could not stand.” |

After about 1815, incidents of highway robbery declined. There is no

single reason for this. Travellers began to carry the compact

multiple-barrel repeating firearms (such as the ‘pepperbox’) that became

available from the 1790s, while the turnpike road system, with its

regularly-spaced tollgates, made it more difficult for robbers to effect

a quick get-away without being seen. From the late 1830s, the growth of

railway travel and of country police forces were further reasons.

Robbery was not confined to the highway, and sometimes the toll-houses

were raided. This was a matter for the Sparrows Herne trustees to

consider:

“On the Hartwell Turnpike near Aylesbury ‘two men in dark clothes, with

their faces disguised, with a drove of cows which had been taken from a

farmyard near ………. Did burglariously [sic] enter the tollhouse and rob

the wife and daughter of several pounds and eight shillings in silver

……’

On the same night at 3 o’clock the Weston Turville gate was also robbed

of 20s. in silver. The toll-keeper’s wife wrote that it was so dark they

could not tell the features of the men but thought their voices were

familiar. From the testimony of Edward Needle one learns that he was in

bed when some person called Master came and said open the gate. Two men

were near the door with clubs and caught hold of my collar and said

‘Deliver your money directly or you are a dead man’. The men were in the

house one quarter of an hour threatening murder and set off for

Aylesbury.”

Sparrows Herne Minute Book 19th March, 1822

It is not recorded whether these robbers were apprehended. Just eight

months later, Edward Needle and his wife did not escape so lightly:

“When Wyatt’s coach bound for London reached Broughton, the turnpike

gate was not open for them as usual. A boy was waiting for the coach,

and from what he said, the coachman got down, and found that poor old

Needle and his wife, the gatekeepers, had been brutally murdered during

the night. Information was sent back to Aylesbury, and Mr Wyatt gave the

alarm at Aston Clinton, Tring and Berkhamsted. Great excitement

prevailed in Tring, and many people went over to Broughton Gate during

the day. Later two men named Croker and Randall were taken at Gaddesden

and charged with the murders.”

Tring Vestry Minutes 19th November 1822

“Aylesbury. Was tried today the capital charge against Croker and

Randall, for the murder of Edward Needle and Rebecca Needle, at

Broughton Gate, or as some call it Weston Gate. The court was very

crowded, and the greatest confusion prevailed. Silence could not be

obtained, and the court was like a bear garden. The judge talked of

adjourning the trial, as he could not proceed for the noise; the

confusion continued; at last a jury was got into the box, and the

prisoners were arraigned, when the court became quieter. Croker pleaded

guilty, Randall not guilty. The case was very plain, and the guilt of

the prisoners could not be doubted for a moment, indeed the judge

declined to hear all the evidence. The witnesses amongst others were C

Whitehall, Mr Wyatt the coachman, Mr Maynard the surgeon, and Mary

Barnacle, a companion of one of the prisoners. The Jury immediately

returned a verdict of guilty, and the judge passed sentence of death

upon them, to be executed in 48 hours, and he also ordered that their

bodies should be given to the surgeons to be anatomised.” [3]

Tring Vestry Minutes 4th March 1823

“This morning Croker and Randall were brought out to be hung on the new

drop in front of the County Hall at Aylesbury. There was an immense

crowd extending to every point from which the gallows could be seen. The

criminals ascended the platform with great firmness, when Croker looked

on the crowd and said ‘God bless you all’. Both made confessions in

detail. There was a great fall of snow at the time.”

Tring Vestry Minutes 6th March 1823

This from the Sparrows Herne Trust Minute Book:

“. . . . after the murder the Trustees ordered that the expense of the

funerals be met from Trust funds, also the expense of the prosecution.

The Reverend Charles Lacy [4] and other inhabitants of Tring were

thanked for their prompt exertions which led to the immediate

apprehension of Randall and Croker who were committed to the gaol at

Aylesbury. £20 reward was paid by the Trust to Thomas Row and Job

Flowers for finding and giving the magistrates three bundles hidden by

the murderers, and £40 was distributed by the Trust as a reward to the

various inhabitants of Tring who had caught the suspected murderers.”

Matters came to a conclusion when the Trustees ordered that a shotgun

with bayonet, an alarm bell and a rattle be provided at each

tollhouse; later in the following year, the shotguns were replaced with

pistols with fixed bayonets.

It was not only sensational stories that were reported in the press. One

can only assume that during one particular week, newsgathering at the

offices of the Windsor & Eton Chronicle (later the Bucks Gazette) was in

short supply, for a seemingly storm in a teacup was reported at

considerable length:

“Marylebone. John Headlin, the driver of the Tring coach, appeared to an

information at the instance of Johnson, the well-known informer [5],

charging him with having carried one more passenger than is allowed by

the 38th of Geo. III cap.48, and by which he subjected himself to a

penalty not exceeding £1. It was deposed that the Tring coach passed

along Oxford Street with ten grown persons and two infants, beside the

coachman, on the outside, on which there was a quantity of luggage . .

.”

Windsor & Eton Chronicle, 24th July 1824

The account carried on with details of how the offence occurred, how the

miscreant was dropped from the coach, and the calling of witnesses by

the defence solicitor, who went on to accuse Johnson of being “a common

informer”. This elicited the reply that “common informers were quite as

necessary to the state as lawyers”. The result was that it was decided

that no offence was intended, and the case was dismissed.

“On Saturday as Mr. C. Grace of

Tring, was returning from Aylesbury market, three men rushed from a

hedge at the top of Tring Hill, and attempted to stop him, but

fortunately Mr. Butcher, the banker of Tring, arrived in sight, and the

men took to flight. They were dressed like hawkers of drapery.

We understand Mr. Grace had a large sum of money on his person.”

Bucks Gazette, 19th January 1839

――――♦――――

“The fall of snow has continued all day and all night, a sharp wind has

sprung up, and in some places the snow is several feet deep, the roads

are completely blocked up.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, Christmas Day 1835

“No mails, so no letters, the London Mail got through to Broughton but

then got fixed in the snow. The coachman, guard, and passengers all got

down to help, but they could not stir it, so they obtained nine plough

horses, and drew the coach to Aylesbury. It ought to have reached there

last night, and is nearly 24 hours behind its usual time.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 26th December 1835

“No communication with any town or village, and it is dreary indeed. The

Inns are full with travellers who cannot continue their journeys. The

Birmingham Coach crawled to Aylesbury where it stopped as it was

impossible to go on; it took 20 hours making 38 miles. Pack-horse

brought some letters.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 27th December 1835

“The snowed coaches are released and went through to London, and traffic

is partly resumed. The cross posts cannot yet travel, neither can the

carriers’ carts; such a snow has not been known before.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 29th December 1835

“Some of the snow-drifts were 20 and even 30 feet deep. Sheep have been

lost all over the country. The Mails and all business and correspondence

were stopped nearly a week, until the multitudes had out a way through

the snow. Several lives were lost in this great snow.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 31st December 1835

Similar trouble was encountered on the very last day of the following

year:

“The fall of snow in Aylesbury and its vicinity was excessively heavy

on Sunday and Monday mornings, and owing to the great drifting in

consequence of the high wind, all the roads leading from the town were

completely blocked . . . . the mail was not extricated until the middle

of Monday, and then could not proceed beyond Aylesbury . . . . at the

New Ground gate the snow drifted above the turnpike-gate, and the people

at the turnpike-house were blocked in for some time . . . . the

Aylesbury coach did not start until Thursday, the road being cleared,

the four-horse coaches started to London at 8 o’clock, and Hearn’s

Dispatch coach driven by James Wyatt returned the same day.”

Bucks Herald, 31st December 1836

――――♦――――

“Dreadful Accident by a Stage-coach ― One of those melancholy

events which have of late occurred but too frequently, happened on

Saturday to the regular Hemel Hempstead coach, belonging to Mr Hearn, of

the King’s Arms, Snowhill, which was overturned in passing the corner of

Hunton Bridge, Herts, owing to the wanton behaviour of the coachman in

endeavouring to make a fine angle, and literally ground to shivers by

the horses subsequently drawing it after them. A woman on the outside

was killed on the spot; another outside passenger and the coachman are

so mutilated that little hopes are entertained of their recovery; and

eight or nine other passengers have been so severely cut and bruised

that a considerable time must elapse before they can again follow their

usual occupations. The outside passengers, among whom was a gentleman of

great property and consequence in the county of Herts, were more

fortunate, but did not any of them escape without injury . . . .”

The Sparrows Herne Trustees took a sufficiently serious view of the accident

for the Earl of Bridgewater, their Chairman, to write to the Clerk

of the Peace:

“I enclose a copy of a resolution passed at a meeting of the trustees

of the Sparrows Herne turnpike road, and request you to lay the same

before the magistrates. In the accident alluded to, a woman on the coach

was killed and other passengers extremely injured. We are of the opinion

that the widening of the bridge on the Watford side (an expense of about

£100) would obviate the present inconvenience, and be of great advantage

to the public.” [6]

Serious accidents involved not only coaches, but more humble

conveyances:

“At the County Infirmary at Aylesbury, on view the body of William

Alderman. It appeared from the evidence that the deceased was a maltster

to Mr John Brown of Tring, brewer, and that on the 6th instant he was

sent by his master to Haddenham with a waggon for the purpose of

fetching a load of malt, and on his return he attempted to get on the

shafts to ride, and in so doing fell to ground, and both of the wheels

passed over his body, he was immediately conveyed to the Infirmary, but

all surgical aid was of no avail, as he died about 19 hours afterwards. Verdict: Accidental Death. Deodand 4s.” [4 shillings]

[7]

Bucks Herald, 10th September 1838

“ACCIDENT. On the evening of Wednesday last, as Mr William Claydon of

Aston Clinton was passing through Tring driving in his cart he came in

contact with a horse and gig driven by a servant of Mr Bennett of the

George Inn, Aylesbury. The collision was so violent that the shaft of

the gig penetrated the chest of Claydon’s horse for several inches, and

it was found be to so severely injured that it was killed on the spot. The horse in Mr Bennett’s chaise was also so much hurt in the shoulder,

that, after lingering until Friday morning it died. Mr Prendergast, the

barrister, was in the gig, the shafts of which were both broken, but, we

are happy to say, the learned gentleman escaped without harm, as well as

the drivers.”

Bucks Herald, 23rd March 1839

From the turn of the century onwards it was sometimes the case of

accidents being caused by the motor car, or possibly by a combination of

old and new technologies. Any accidents were considered

sufficiently important to report in the local newspapers:

“Mr Gifford Foulkes [8] while driving to Chesham had a very

narrow escape. The horse, apparently started by something, swerved

suddenly on one side and running against the wall, broke one of the

shafts. It then started off uphill and did not stop until the other

shaft was broken . . . . Mr Foulkes and the gentleman with him were thrown

out, but neither were much the worst for the experience. The horse did

not escape so lightly, its legs being badly damaged.”

Bucks Herald, 27th April 1901

“On Tuesday afternoon a horse attached to a cart started off

from Hastoe and was not stopped until he reached the town. In his

journey he severely damaged the trap but fortunately did not collide

with anything.”

Bucks Herald, 18th May 1901

“On Sunday evening as a motor car was coming from Wendover

down the Aylesbury Road in Tring it ran into the bank. All the occupants

were thrown out and the car considerably damaged. It was found that two

or three of the motorists were severely injured, while all were more or

less bruised. Dr le Quesne [9] attended to their injuries and they were

subsequently driven home in a conveyance from the Rose & Crown.”

Bucks Herald, 29th June 1901

“On Wednesday midday a car came through the town at a smart

pace containing four gentlemen. As they came up the School House hill

they blew their hooter which alarmed the pony of Mr F Johnson, jeweller,

which was standing outside his shop. The pony reared and Mr Johnson

rushed to its head, but was thrown over with the pony which swerved and

fell, breaking one of the shafts. The gentleman in charge of the car,

who gave his name as Mr W V Thorne of New York, amply compensated Mr

Johnson for the damage to his trap and for his own personal injuries,

before proceeding on his journey.”

Bucks Herald, 29th June 1901

“On Tuesday evening as a number of Messrs. Finchers

workmen were returning from Northchurch, the cart in which they were

riding, near the London Lodge, was run into by a cart driven by Mr Baker

of Wigginton. Both the shafts of the former snapped and the men were

thrown out. Fortunately no-one was seriously injured.”

Bucks Herald, 9th November 1901

“On Thursday as Mrs Oakley of Long Marston was driving

into the town, when coming up the hill near the Green Man [10] her pony

took fright at something and swerved across the road. Mr H Johnson who

was going in the opposite direction was unable to get out of the way,

and the two carts came into collision, both Mrs Oakley and Mr Johnson

being thrown out. Mr Johnson escaped with a few bruises, Mrs Oakley was

cut about the face.”

Bucks Herald, 7th December 1901

Two or three wheels could be as difficult to control as four:

“ACCIDENT TO A LADY TRICYCLIST ― On Saturday last, a

lady who was riding a tricycle on the Aylesbury Road, had a mishap. Her

dress became entangled in one of the wheels, and the result was an

upset, giving the fair tricyclist a severe shaking, which rendered her

incapable of resuming her ride. Fortunately a gentleman, who happened to

be passing in a trap, was enabled to assist her into Tring.”

Bucks Herald, 17th June 1882

“On Wednesday evening last a little boy named

Wilkins, about seven years of age, met with a somewhat serious accident

by being knocked down and run over by a bicycle. The boy ran out of the

George Yard [11] to cross the road, just as a young man named Muncey, of

Aldbury, was coming by on his bicycle. As he was descending the steep

hill the bicyclist was travelling at a good speed, and before he could

pull up he had knocked the boy down, and ridden over him. The boy had

several of his teeth knocked out, and was badly shaken. He was at once

taken to Dr Brown’s surgery, and attended to. The part of the road where

the accident occurred is a dangerous one for bicyclists, and hardly a

week passes without one or two narrow escapes occurring.”

Bucks Herald, 8th August 1889

“A runaway cycle. On Sunday morning a young lady from

Berkhamsted was riding down Albert Street when she lost control of her

machine. She dashed with much force into the windows of Messrs. Batchelors’ stores, which face Akeman Street, as to smash the window

frame and shatter four large pieces of glass. The rider escaped without

injury.”

Bucks Herald, 7th August 1901

As the century progressed, road accidents became less newsworthy, and in

the age of the motor car only those of a very serious nature were

reported, with the bumps and dents incurred in everyday motoring being

ignored entirely.

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTE

1. In 1688 there were 50 offences on the statute book punishable by

death; that number almost quadrupled by 1776, and reached 220 by the end

of the century. The system of English laws and punishments existing

during this period has since come to be described as England’s ‘bloody

code’.

2. The famous Dick Turpin was publically hanged at York in April 1739.

Ironically, he was hanged by another highwayman, Thomas Hadfield; as

York had no official hangman, Hadfield was granted a pardon for

acting in that capacity. One wonders about Turpin’s thoughts were of

being hanged by a former colleague in crime.

3. ‘Anatomised’ ― the custom of releasing a criminal’s body for

dissection after execution was then common practice. It would be taken

to the Surgeon’s Hall and used for teaching purposes. The law was

changed in 1832.

4. Vicar of Tring 1819 -1839.

5. Common Informers Act 1575, repealed 1959. ‘Common informer’ – one

who, without being specially required by law, or by virtue of his

office, gives information on crimes.

6. From the County Records of Hertford, page 285, entry 289.

7. ‘Deodand’ ― a chattel forfeited to God, if a coroner’s jury decided

it had caused the death of a human being. Finally abolished in 1846.

8. Gifford Foulkes ― a land agent in Tring.

9. Edward Le Quesne ― a doctor in Tring.

10. The Green Man ― an inn standing on the site of the entrance to Tring

Memorial Garden.

11. Now the premises of Costa Coffee.

――――♦――――

[Next Page]

|

|