|

ROADS, AND THOSE IN TRING

THE MOTOR AGE

|

“TRING. THE COMING VEHICLE

― On Sunday a motor car passing through the town came in for

a considerable share of attention.”

Bucks Herald,

12th November 1898 |

|

Motor vehicles and

garages

It is not known for sure who was the first to own a motor vehicle in Tring, but strong

contenders for the honour are Gilbert Grace, the ironmonger; Walter

Thomas, manager of Tring’s first power station in the old Silk Mill

premises; and, possibly, Lord (Nathaniel)

Rothschild.

Walter Thomas’s car parked outside the Silk

Mill

Several firms in the town applied to sell motor fuel, the first being in

1895 at Grace’s premises in the High Street, the local press reporting

that “plans have been passed

for Mr Gilbert Grace’s petroleum store as long as a ventilation shaft is

erected”. Gilbert’s love of motoring was passed down to

his son, Harold, who later became a successful racing driver

specialising in Riley cars. Before

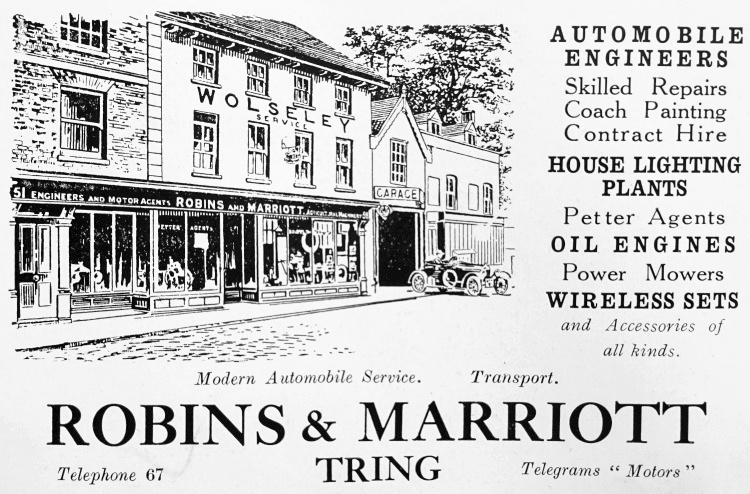

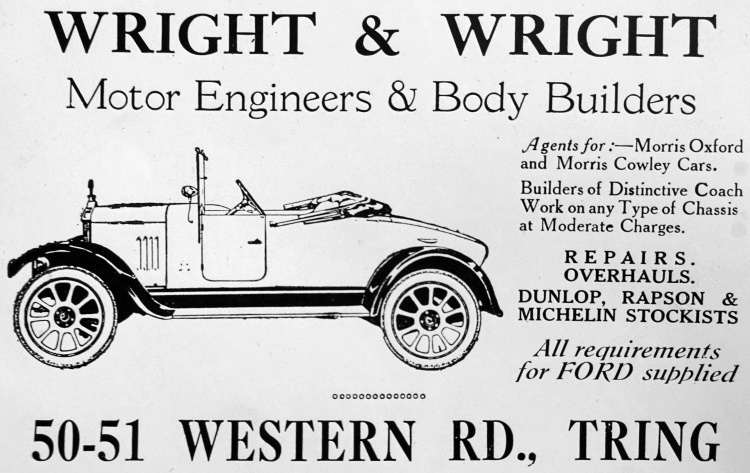

long Wright & Wright and Gower’s Garage, both in Western Road, obtained

petrol licences, and they were followed by Roberts & Marriott [1] and

The Market Garage in Brook Street.

Advertisements for some of Tring’s former

garage companies.

|

WRIGHT & WRIGHT, Coach and Motor

Body Builders and Garage Proprietors, Western Road, Tring —

Messrs. Wright & Wright’s

motor works, situated near the Britannia, were established here

in the year 1870 by Mr. George Parrott, who took Mr. A. S.

Wright into partnership in 1901. Mr. Wright, who is a

native of Tring, succeeded later to the business, and took into

partnership, in 1911, his cousin, Mr. R. G. Wright. The

premises have recently been enlarged, and are equipped with

plant for vulcanizing, mechanical repairs, etc. There is a

garage for about twenty cars. The firm are district agents

for the Mors, Ford, and the Maxwell cars. The chief work

of this firm in recent years has been body-building for motor

cars for pleasure or business. Tele. No. 12.

Advertisement, Pictorial Record,

1916 |

Wright & Wright expanded to become Tring’s largest motor business, and

by the start of World War I had obtained orders to construct small

trucks for the War Office. In 1919 an order was obtained to design and

produce the bodywork for a prototype of the prestigious Cubitt car,

manufactured in Aylesbury, [2] and the firm’s

coachbuilders subsequently built a number of bodies for both 2- and

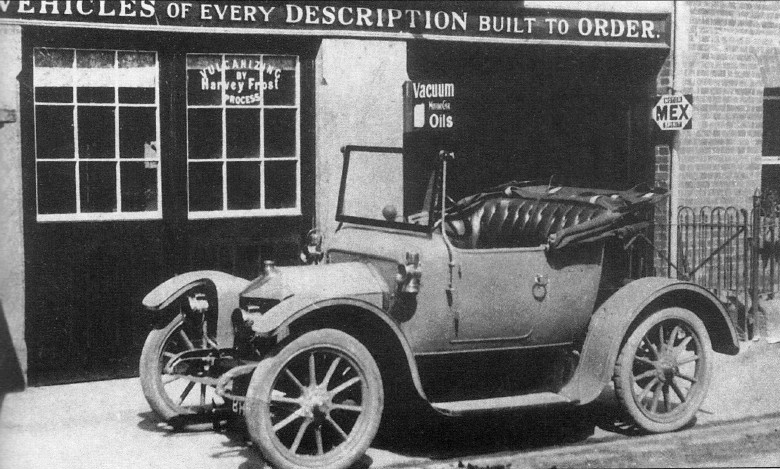

4-seater models. In the photograph below, the firm proudly claims “vehicles

of every description built to order”!

From an age when motor vehicles were built

in Tring.

A Wright & Wright-built

open-top car displayed outside their garage in Western Road.

At various times the business held dealerships for Ford, Austin, Rover,

Morris and Wolseley cars. Wright & Wright’s premises finally disappeared from the Tring scene in

1999, when the site was redeveloped for housing, but the Market Garage continues to serve motoring

needs.

|

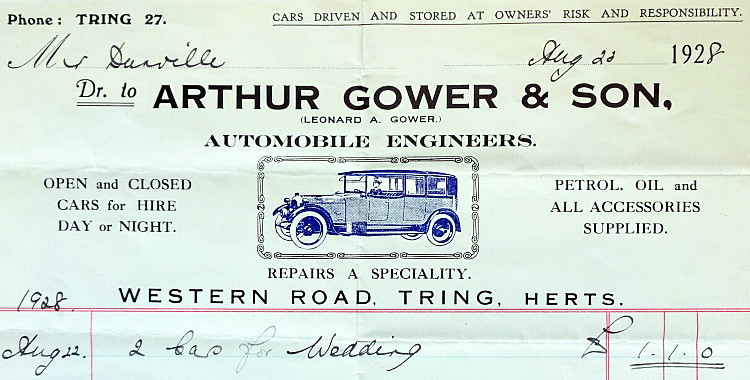

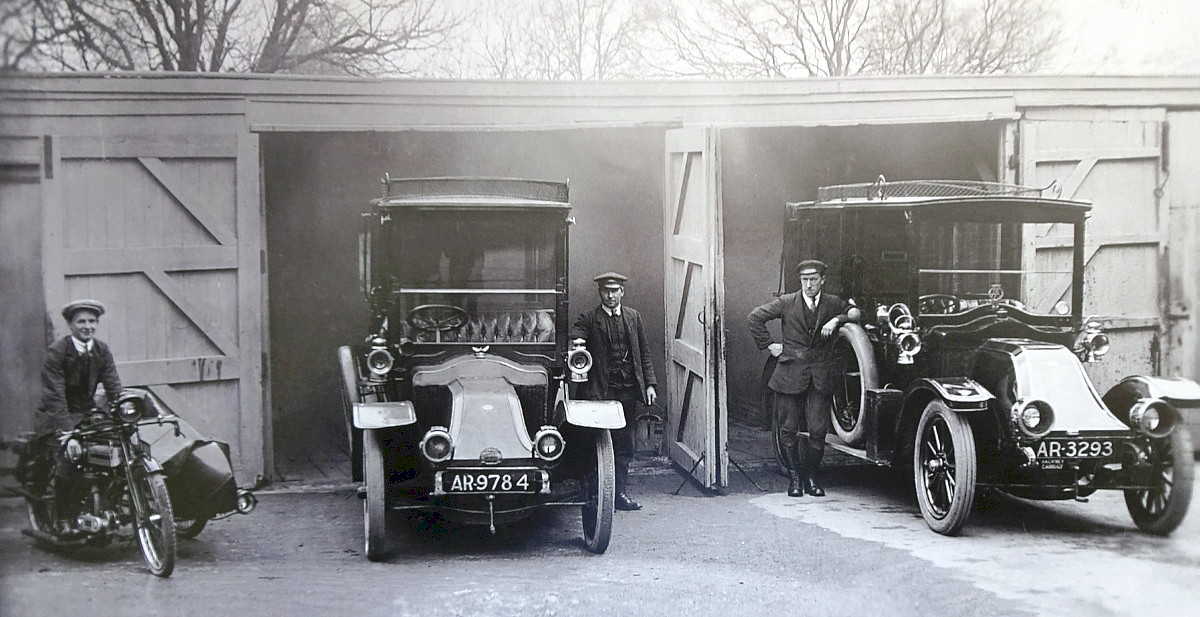

Above: Gower’s bill for providing “2

cars for wedding”, but from a later era than the Gower limousines pictured

below.

|

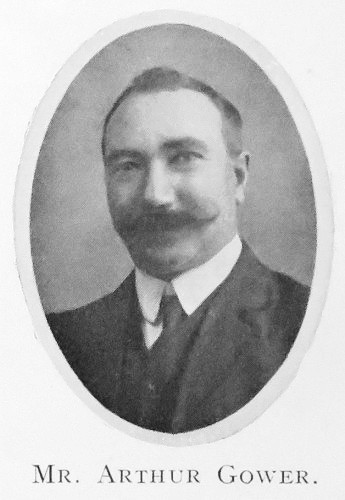

ARTHUR GOWER, Garage and Livery Stable

Proprietor, Tring Motor Garage, “Goldfield,” Western Road, Tring.

− Mr. Arthur Gower, a native of Tring, has carried on business at

his present address for the past quarter of a century − a length of

period which is sufficient indication that he is accustomed to

satisfy his patrons. To meet the needs of the new industry,

the motor car traffic, Mr. Gower has built additional premises and

garage. He has three cars for hire, cars of a superior type −

a Vauxhall holding six persons, and two Charron cars, also holding

six. Carriages for weddings and for funerals are available,

also, for supplying to the undertakers, a glass hearse. The

two brakes, each holding seventeen persons, are well known in Tring,

and always in demand at holiday times. Tele. No. 27.

Advertisement, Pictorial Record, 1916 |

|

|

In addition to the existing taxi service available from Gower’s Garage,

by the 1920s several enterprising businessmen in the town were offering

char-a-bancs for private hire by clubs, church groups and others for

outings and ever-popular excursions to the seaside. The proprietors

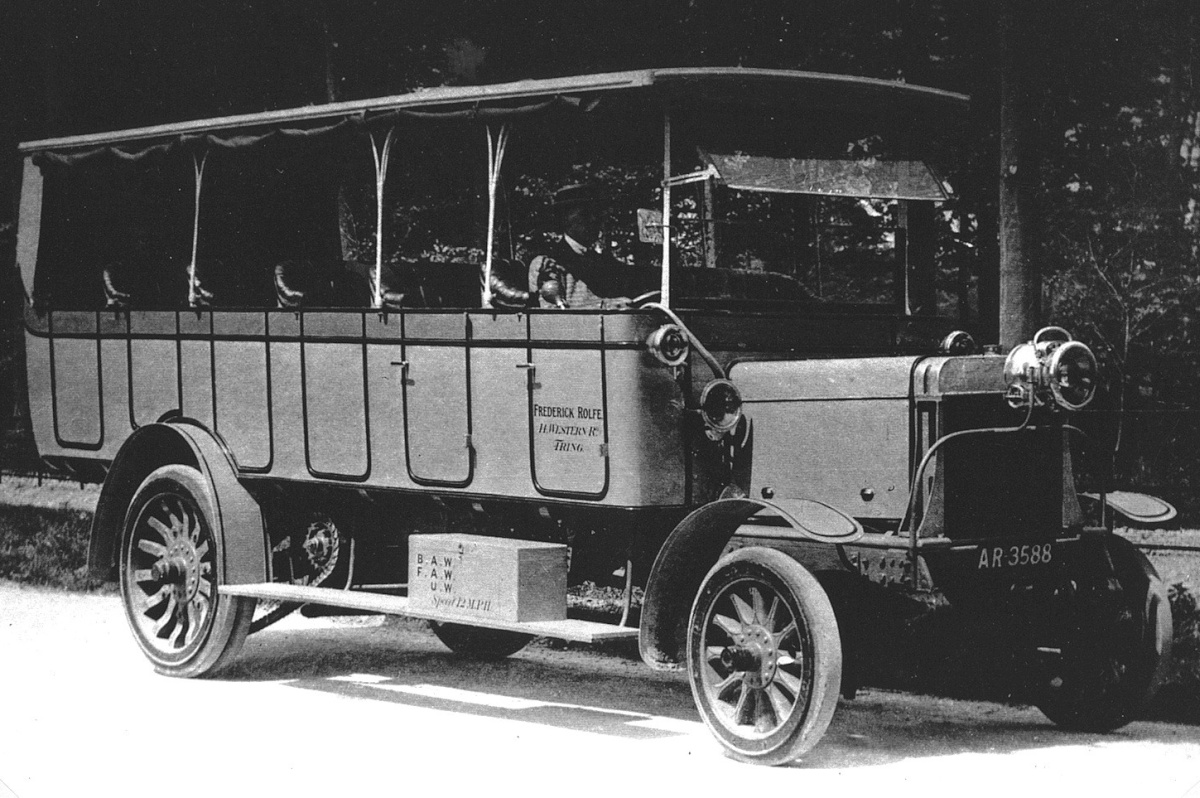

included Ebenezer and Frederick Prentice, and Frederick Rolfe ― who exchanged the bodywork on the chasses of his winter-months’

coal delivery lorries for char-a-banc seating in the summer (see below). |

In 1913 ― some of the versatile Frederick Rolfe’s summer

(above) and winter (below) businesses activities.

|

Road construction

Tring Urban District Council (UDC) was formed under the Local

Government Act 1894 as the successor to Tring Local Board of Health.

It held its first meeting on 3rd January 1895 and until April 1974, when

the Urban District was absorbed into the Borough of Dacorum, the UDC

governed Tring. Looking back, the scope of the UDC’s

responsibilities now appear surprising (if at times somewhat amusing) ―

for instance, the following are some of the subjects discussed at a UDC

meeting held in June 1896:

“The Surveyor was instructed to warn butchers not

to hang meat over the footpaths. ― The Council decided to enforce

regulations that no part of a shop blind should be less than 6ft 6 in.

from the pavement. ― Mr. Joseph Clarke’s application to be registered as

a cow-keeper was granted. ― Mr. Jeffery Stratford’s petroleum licence

was renewed for one year. ― A sample of water from Tabernacle Yard was

ordered to be sent for analysis to the Medical Officer for Health. ― The

Surveyor and the Highways Committee were instructed to ascertain the

cost of granite for the Station-road. ― Councillor Grange called

attention to the dangerous turning into Cow Lane from the London Road,

and the Surveyor was instructed to arrange with the Surveyor for the

County Council for improving the same. ― Attention was called to the

delay in obtaining horses for the conveyance of the Fire Brigade when

summoned to fires. The Surveyor was requested to confer with the Captain

of the Brigade, to see if some better arrangement could be made.”

Highways were part of the new Council’s

responsibilities, and a Highways Committee was formed to oversee and

manage their condition.

The Stone Pickers, by George Clausen (1887).

|

BREAKING ROAD STONE.

TRING URBAN DISTRICT

COUNCIL: “THE

WAGES OF THE ROADMEN

. . . . a man ought to be able to earn 3d an hour at

breaking stones, and the Surveyor ought to know whether it

was worth 9d. or 10d. to break a load of stone. There

was no doubt a great difference in the quality of the

stones, but if the pay was an unfair price, then it ought to

be increased. ― The Chairman said if the Surveyor thought

more should be paid he could pay it. ― Mr Bishop said in the

summer months there was no stone-breaking done, and that if

the men went to Cholesbury it was worth more to break

stones, and then they had all weathers. ― Mr Baines and Mr

Bishop did not seem to understand that they had only two men

who broke stones by the piece. They had two very old

men who worked by the day. He had one young man who

broke eighteen loads one week and twenty-two the next,

earning 13s. 6d. [67.5p]

and 16s. 6d [82.5p].

The two old men, Wilkins and John Adams, earned about 8s.

[40p] or 9s.

[45p] a week.”

Bucks Herald, 6th July

1895 |

At the time when Tring UDC was formed, that part of the

Sparrows Herne Turnpike Road

passing through the Town had been returned to Council care (1st

November 1873), added to which were all the Town’s other roads, lanes

and public footpaths. Apart from the occasional steam road

locomotive,

most traffic went on foot or by hoof, for which the roads of the time were adequate. The more important roads were ‘metalled’,

which meant that they were

built on a sub-layer of broken flint or ironstone slag over which was

laid a surface of compacted gravel.

Flint, which is plentiful in this area, was a nuisance to farmers, so

those receiving parish relief ― often women and children ― were employed

to pick it off ploughed fields to be used for road maintenance; for this

they were paid between 8d and 1s. per cubic yard. Flints were also

quarried from the naturally occurring pockets found in the

Cholesbury/Hawridge area. Men were then employed to

break the flints so collected into a suitable size for road use.

Charles Delderfield of Aldbury breaking

roadstone.

Born in 1843, Charles was blinded in one eye by a flying

stone splinter. He lived into his 90s

Slag ― a solid waste by-product produced in the manufacture of of iron

and steel (and used by the Romans in road building) ― was sometimes used

as an alternative to flint, such as its application to Station Road in

1896:

“Several Councillors referred to the very

unsatisfactory character of most of the flints supplied recently, and

the Surveyor said there was very great difficulty in obtaining clean

picked flints. The general opinion being that the cost of granite

was too high, Councillor Stevens suggested ironstone slag, which he had

seen used with much success. In the discussion which ensued, it

transpired that the principal objection to the use of slag is that in

damp weather it emits a rather strong, but not unhealthy smell.

Ultimately, Councillor Stevens proposed, and Councillor Crouch seconded,

‘That we use slag on Station Road from the boundary of Aldbury parish to

Cow Lane.’ Four voted for the motion and three against, so that it

was carried.”

Bucks Herald,

5th September 1896

The annual reports of the Surveyor to the UDC give an interesting

insight into the extent that (when the Town was self-governing) the UDC

managed our roads, a different situation to that which prevails today.

Perhaps 1911-12 was a particularly busy year, for a great deal of road

work seems to have been done:

“. . . . The highways that have been metalled

include parts of Hastoe Lane, Gladmore Lane, Cow Lane, Station Road,

Bulbourne Road, Wingrave Road, Grove Road, Marshcroft Lane, Brook

Street, Icknield Way, Frogmore Street, King Street, and Henry Street.

The materials used on the above work include 362 tons of granite, 46

tons of chippings, 417 tons of gravel, 1,972 [cubic]

yards of flints, and 248 loads of brick rubble. The steam roller

has been employed for 94 working days. The nett cost of the work

on the highways was £1,750 4s. 1½d.”

Tring UDC Surveyor’s report on the

highways, April 1912

Laying the dust

Tarring.

In the years leading up to World War I., the townsfolk of Tring began to

witness a move away from the McAdam

type road surfaces described above,

to the sealed road surfaces we

have today.

No doubt our forebears were as familiar with potholes as we are,

but they also had to contend with road dust. One problem (there

were others) that the new motor vehicle brought with it was the clouds

of dust it raised in dry weather from the unsealed road surfaces of the

time. Tring’s shopkeepers complained that their wares ― which at

that time they often displayed in front of their premises ― were

becoming coated with road dust during dry weather while being immersed

in a dust cloud was an unpleasant experience for pedestrians and other

road users. |

The progress of the early motorist along the unsealed

road surfaces of that era

was marked by a trailing screen of dust

|

Other problems presented by unsealed roads ― particularly those where

flint in the sub-layer became exposed ― was that of the sharper and

larger stones cutting and puncturing the new pneumatic tyres, or being

thrown up by the vehicle wheels and damaging the underside, especially

puncturing vehicle fuel tanks. Loose gravel also skipped up

hitting the car body, lights or windshields when vehicles passed at

speed. And so the battle against road dust and loose chippings

commenced. In an attempt to combat the problem, the Council decided to

employ tar as a sealant, and they

selected Station Road for the trial:

“Mr Asquith suggested that tar should be tried with granite

[chippings] on a length of the main road.

This would produce a better road, its life would be increased, and it

would be practically dustless. He (Mr Asquith) also thought the

granite used on the roads was too small, and not of quite the right

character. A less brittle granite of not less than two-inch gauge,

laid on a bed of asphalt and steam-rolled, would give a road which would

yield the minimum dust in dry weather, and the minimum of mud in wet.

This would not materially increase the estimate, and any additional

first cost would be more than saved in the increased durability of the

road. Anything, too, which would reduce the dust nuisance was

very desirable in these days of mechanical traction . . . . it was

resolved that the report of the Highways Committee be adopted, and that

the Committee be empowered to spend £25 in treating a length of Station

Road as suggested.”

Bucks Herald, 8th June 1907

Amazing what you could then get for £25!

The Station Road trial was

successful, for in November 1912 the Town Council decided to tar-spray

the whole of the road together with London Road, the High Street,

Western Road and Aylesbury Road, all at a cost of £270; it was hoped

the Road Board would

contribute towards the cost, but

for some unknown reason they declined. Nevertheless, the

project went ahead and in June of the

following year the Bucks Herald was

able to report that:

“. . . . the work of tar-spraying provided for

in the estimate had been completed, and that he [the

Surveyor] had got out the cost, from which it

appeared that a net saving of about £44 had been effected. He also

stated that he thought that if the area previously watered was not

extended, a saving of about £40 could be made on that item; and he asked

for instructions as to whether it was desired to carry out any further

tar-spraying . . . . It was decided to recommend that Akeman Street,

Frogmore Street, Langdon Street and Lower Albert Street be tar-sprayed

at an estimated cost of £44 . . . .

The Rev. Charles Pearce referred to the excellent way the tar-spraying

had been done. ―

Mr Batchelor endorsed this, and said that several anti-tar people had

been quite converted.”

Bucks Herald,

14th June 1913

|

Mending the road ― stones without tarring ― between Long Marston

and Dixon’s Gap c. 1933. The caption on the photo states that

the stones were delivered to Marston Gate

Railway Station and Mr Cartwright fetched them with his horse and

cart. |

By February 1914, the Town Council’s road improvement plans had

been extended to include tar-spraying Parsonage Place, King

Street, Charles Street and Park Road, for which purpose a

contract had been placed for the supply of 12,500 gallons of tar

at 4½d a gallon. By June of the following year the work

had been completed; the 20 barrels of tar remaining were

used to treat Longfield Road, left out of the original plan to keep

the overall cost

within estimate.

In receiving a tar-and-chippings surface, Miswell Lane appears

to have been the Cinderella of the Town’s old roads. At a

Highways Committee meeting held in July 1919, the road was

reported to be in

“a bad state, the surface being very rough and

dangerous in places”. However, the Surveyor

reported that there was no money in the budget to deal with the

problem; at their next meeting, the Committee decided to defer

consideration of tarring until the following year’s work was

planned. Nothing further is then heard of the problem, so

it must be assumed that Miswell lane was tar-surfaced during the

1920s.

And so ― even if they do come in for much criticism in the

present age ― Tring’s roads gradually acquired modern

sealed surfaces.

Street watering.

Street watering was another technique used to combat road dust, and for

other purposes that no longer apply.

Here, the Town Council commissioned Gilbert Grace, a local ironmonger,

to fashion a water-sprayer for attachment to one of their carts:

“With regard to street watering it was decided that no additional

watering should be undertaken, and that High Street should be watered

once a day, but that the other tar-sprayed roads should not be watered.

― Mr

Asquith pointed out that if any extension of watering was possible, New

Mill was entitled to a little attention.

― Mr Batchelor

replied that the question was before the Highways Committee the previous

evening, but they decided they could not see their way to find the

money.”

Bucks Herald,

14th June 1913

Tar also has a propensity to melt, so until it was replaced

by bitumen, which is less

temperature sensitive, the water wagon was also used to cool road

surfaces in hot weather. In his rhyme below (‘The Water Cart’), Ron

Kitchener refers to a further use for the water wagon, that of disinfecting

the road in an age when there still much hoofed traffic about, which,

inevitably, left its calling card. The photograph below show

Tring’s water wagon at work in the High Street, probably during the 1930s.

The Tring Urban District Council water cart

at work outside the Rose & Crown.

|

The Water Cart |

|

You’ll remember the “Tarring”

Which was really well done,

Well! Along came a Water Cart

To cool tar from Sun.

A loose drawing Cart,

Shaped like a Drum

With pipe like a watering can,

To cause so much fun.

For the long scorching Summer,

It would water the ways,

And lay all the dust

From the hot sunny days.

If that wasn’t the purpose

Then maybe much more,

To spread disinfectant

To sweeten the floor! |

Perhaps a tradition

or a product of time,

When livestock paraded

To leave much behind.

Or maybe amusement,

As watering came,

For children did love it

And thought it a game.

A kind of free shower

To give feet a bath,

Whatever the reason

It made many laugh.

Ah! Now for the progress,

They don’t do the same,

that’s all a redundant,

To wait for the rain. |

|

Ron

Kitchener,

from JUST “RAMBLING”

ON WITH

ME. |

Tring’s early bus

services

On 20th July 1837, the London & Birmingham Railway Company commenced

operating a train service on the newly-completed section of line between

Euston and Boxmoor. The new railway had an immediate impact on the local stagecoach

business, although their proprietors cannot be criticised

for lacking adaptability. These notices from the Bucks Herald for

August, 1837:

|

|

|

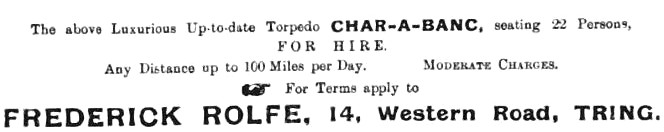

Station omnibus service,

Bucks Herald 21st October 1837.

‘The

Station-House at Pendley Beach’ refers to Tring Station. |

“Jospeh Hearns begs also to announce that his coaches from Tring to

London and from Hemel Hempstead to London are discontinued, and which,

in future will meet the respective trains from Tring at Box Moor and

also from Gaddesden, Ashridge and Hemel Hempstead at Boxmoor.”

“John Elliot, Carrier of Aylesbury: Respectfully informs his Friends and

the Public that he intends conveying Passengers and Luggage every

Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings from the Angel Inn, Aylesbury

(where Passengers may secure places) to the Station House at Box Moor,

and that he will start from Aylesbury at six o’clock each morning, and

leave Box Moor at six o’clock the same evening. Passengers 2s. each

extra luggage to be paid for.”

“Chas. Johnson, Bull’s Head Inn, Aylesbury respectfully informs his

friends and the public that he has commenced running an Omnibus from

Aylesbury to Box Moor, and back, daily.”

And as the line extended northwards ― Tring being reached on the 16th

October ― the local coach operators adapted to the changing situation:

“The Tring Station on the Birmingham railway is two and a-quarter-miles

from the town, and thirty-one and three-quarters from Euston Square.

Conveyances attend at this Station on the arrival of several trains, to

carry passengers to Tring, Aylesbury, Oxford etc. Passengers intending

to join the trains are desired to be in good time, as the train leaves

each place as soon as expeditiously as possible. No persons are booked

on the railway after the arrival of the train in the Station.”

Pigot’s Trade Directory 1838 – entry for Tring

“A Coach from the Plough Inn, Tring, to meet all the trains, and an

Omnibus from the Rose & Crown, Market Street, Tring: Elizabeth Montague,

Post Mistress – Letters from London arrive (by railway) every afternoon

at one and night at eleven, and are despatched every morning at four and

forenoon at half-past eleven. Letters from the North (by railway) every

morning at half-past five, and at twelve, and are despatched every

morning at three.”

Pigot’s Trade Directory 1839 – entry for Tring

Tring’s first petrol-driven

bus (1914)

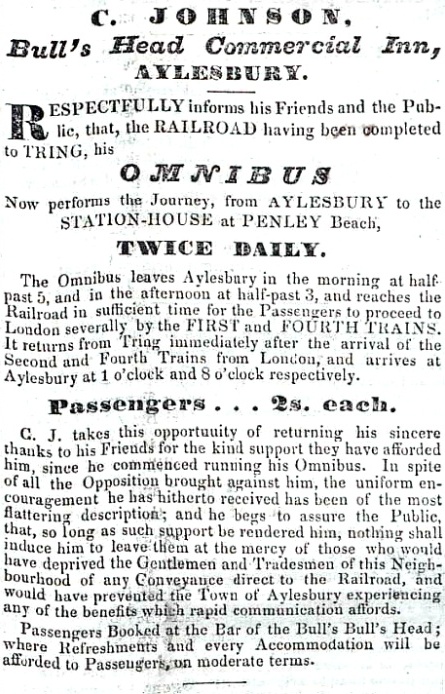

Thus, Tring’s earliest bus service can be said to have commenced on the

opening of the town’s railway station in October 1837. Bus services to the station continued to operate under various

ownerships. In 1846, the London & Birmingham Railway became a

constituent of the London & North-Western Railway Company, which

operated a horse omnibus (Chapter 6)

between the town (The Rose & Crown Hotel) and its station until February

1914, when the petrol engine replaced horse traction:

“The horse ’buses ran by the

Tring Omnibus Company have been replaced by motor ’buses

belonging to the Railway Company, which have provided more rapid, if not

more reliable, communication between the station and the town.”

Bucks Herald, 2nd January, 1915

Towards the end of WWI, a service was provided for the transport of

passengers and general deliveries, calling at Bulbourne, Pitstone and

Ivinghoe.

A Leyland Lion with LMS bodywork about to

depart from the Rose & Crown for Aldbury

Following WWI and the railway Grouping, [3]

the London Midland & Scottish Railway Company operated a fleet of buses

in the Tring and Hemel Hempstead areas, most being Leyland Lions fitted

with bodywork built in the Company’s Derby workshops.

A London General AEC NS-type bus on route

301 (Aylesbury ― Bushey) at Aylesbury c.1932.

This open-top vehicle (top speed 20

mph!) entered service in 1924 and was withdrawn ten years later

This fleet was taken over in 1932 by London General Country Services

and, in the following year, by the newly formed London Passenger

Transport Board, [4] Tring being just within the

North-Western boundary of the Board’s operations.

A Leyland Cub on the 397 service (Tring ― Chesham) heading

for the ‘LT Garage’ at Tring

The Tring Bus Garage,

Western Road

At this point it is appropriate to mention a long-departed local

landmark, the Tring Bus Garage. Built in the London Transport style, it

stood in Western Road on the site now occupied by the Royal Mail sorting

office.

The garage’s history began in 1925 when E. Prentice & Son set up the

Chiltern Garage, on the site of the former Gem Cinema, advertising

themselves as motor engineers and char-a-banc proprietors. The

firm also had an interest in local bus services. Prentice & Son was acquired

in 1932 by London General Country

Services, which in the following year was absorbed by the London

Passenger Transport Board, the logo ‘London Transport’ then adorning

their buses (see above, although this bus is being operated by London

Transport’s Greenline subsidiary). |

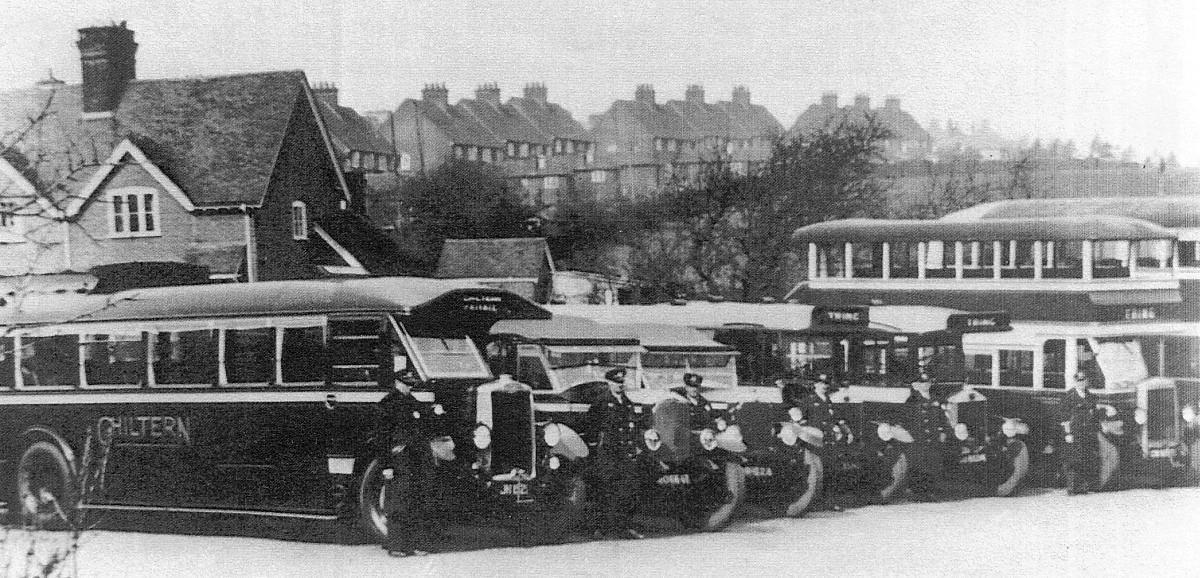

Above, the Chiltern garage, Western Road, in

1931. Below, some of the company’s bus fleet

|

In 1935, London Transport opened a large Art Déco-style bus

garage and

office in Western Road on the site of the former Chiltern Garage to

serve the needs of the Aylesbury to Watford service and other local

routes. The Board also began to advertise a bus service passing through

Tring, London and into Kent operated by their Green Line Coaches

subsidiary.

Tring was one of London Transport’s smaller garages, with less than 20

buses and coaches stationed there. Probably for this reason it was

closed in 1977, the site then becoming a depot for Unigate Dairy before

assuming its present role as a Royal Mail sorting office. [5] |

The London Transport bus garage, Western Road, Tring.

‘Our

Local Bus.’

|

You could tell the time for sure,

As Bus switched on the power,

Twenty past and twenty to

And then upon the hour.

You could choose to go up top,

With slatted sides so plain,

Tarpaulin sheets to cover up,

In case it turned to rain.

A staircase open and outside,

And up that you could pop,

One curved brass rail a winding,

To help you to the top.

Two rings would start Bus on it’s way,

One ring would make it stop,

One long cord from front to back,

Conductor did the lot.

That was many years ago,

Now progress has been made,

Diesel powered and modernised,

With so much to be paid! |

The Driver is a one-man crew,

You pay as you go in,

No longer any open top,

You all can sit within.

No “Ding Ding” or even “Dong”

If Bus has come your way,

So lucky if it comes on time,

You could wait there all day!

The Driver and Conductor,

Were friends of yesteryear,

They greeted you so cordially,

And fares were far from dear.

Now we get from here to there,

Who could say more than that,

It’s more like sitting in a Hearse,

There is no friendly chat.

There seems no pride or courtesy,

No one to really care,

Something we left so far behind,

The modern way to share. |

The Bus no longer

gleaming bright

To give a friendly pat,

It’s just the local transport,

I’ll say no more than that! |

|

|

Ron

Kitchener,

from JUST “RAMBLING”

ON WITH

ME. |

――――♦――――

The post-war era

After WWII as modern communications improved and the original pipe work

laid by utility companies under Tring’s main road started to wear out

and drastic digging was often required. The best efforts of the Civic

Authorities were not always appreciated, and exasperation probably led

Reverend Hearn of Tring’s United Free Church to pen this verse on 12th

May 1950 (as might be expected from a clergyman, this poem about Tring

High Street ends with a telling analogy):

|

‘THE BROKEN ROAD.’

They laid it down with utmost care,

Expense they did not seem to care

To make it good they worked so hard

The camber right, the surface tarred

The central line done in white

With ‘cats eyes’ shining in the light

A roadway worthy of the best

If only they would let it rest

But no, their work was all in vain

They had to dig it up again

For whilst the traffic safe did go

They had not put some pipes below

They marred what seemed a perfect strand

And all because they had not planned.

So life may be a broken road

Because we reap what we have sowed. |

In the 1990s, similar complaints could be heard the cost of the road

improvement scheme through the town centre, which caused considerable

noise and chaos while the work was in progress. The Highway Authority

had taken up with seeming enthusiasm the fashion of laying fancy

block-paving instead of the more mundane tarmac. Although the outcome

looked attractive, it proved an unsuitable road surface for a busy town

centre high street. The constant transit of buses and other heavy

vehicles quickly exposed its weak points, especially around drain

covers, and it was not long before sections of the surface had to be

re-laid.

The High Street paving project, 1992.

The A41(M) Watford-Tring

Motorway

For many years residents of the towns along the A41 from Hunton Bridge

to Aston Clinton had to put up with the noise and congestion caused by

heavy traffic. This problem had first come to the attention of the road

planners in the 1920s, when consideration was given to by-passing

this section of road. Proposals were made in 1927 and 1928, in 1944 and

in 1951, but no steps were taken. Eventually in May 1971, the Department

of the Environment published proposals for what was named the A41(M),

which was to run for 15 miles from Watford to Aston Clinton, a mile or

two short of Aylesbury. Due to the inevitable objections, the Secretary

of State decided that a public inquiry should be held. Having considered

individuals’ objections and representations, together with the report of

the independent inspector who held the public inquiry, it was decided

that the majority of the route should be confirmed, but with some

modifications.

Plans were then developed to the stage at which the line of the motorway

was even marked on Ordnance Survey maps. The 2-mile Tring Bypass was

built as the first section of the proposed Watford-Tring Motorway, but

on its completion work stopped and what had become the Watford-Tring

Motorway project was quietly laid to rest.

The Tring Bypass, opened in 1973, was built to motorway standards,

although when it appeared that the rest of the motorway would not be

built, the Bypass was downgraded. In the meantime traffic on the A41

continued to increase until the need for a higher capacity road could no

longer be avoided. Thus, in the 1990s, a fast dual carriageway on the

same alignment as the A41(M) was built, but not to motorway standards;

it has no hard shoulders (although there are lay-bys) and the junction

designs are substandard, some might even argue ‘dangerous’. The new road

was completed from Junction 20 on the M25 to Tring in 1993. But what

about Aston Clinton, which was part of the original bypass scheme?

|

“In a few hours’ time my constituents in the village of Aston Clinton

will wake up to the rumble of lorries and the roar of cars passing

through their small village. I am grateful for the opportunity to bring

to the attention of the House the long wait that those villagers have

had for a road improvement first promised them in 1937, and to press on

my hon. Friend the Minister for Railways and Roads the case for the

Aston Clinton bypass to be given the highest possible priority, within

what my constituents and I accept is inevitably a finite road budget in

any one year.”

Hansard ―

David Livingstone M.P, House of Commons debate, 02 April 1996 |

In 2003, the dual carriageway was finally extended north of Tring to its

original destination with the addition of the 4-mile Aston Clinton

Bypass.

The Aston Clinton Bypass, looking north

from the Icknield Way Bridge

In 2003, the Highways Agency handed over control of this section of the

A41 to Buckinghamshire and Hertfordshire County Councils, at which date

it ceased to be a trunk road. This decision reflects the road’s regional

and local importance and the fact that, as a through route, it stops

short of Aylesbury. But at least it was built -- eventually.

The Tring By-pass

The 1970s was to see the biggest change to Tring’s main highway since

1711. For many years it was apparent that the town could no longer cope

with the volume of traffic, especially as the size of heavy goods

lorries increased. The need for a by-pass and the routes it might take

were discussed at length, and not without the usual vehement protests

that accompany such undertakings. None of the prospective routes was

ideal, for lines both north and south of the town would entail the

destruction of attractive countryside held so dear to the town’s

residents. The major concerns were that the northern route would dissect

land on the Pendley Estate, while the southern route would slice through

Tring Park; it was the southern route that was chosen.

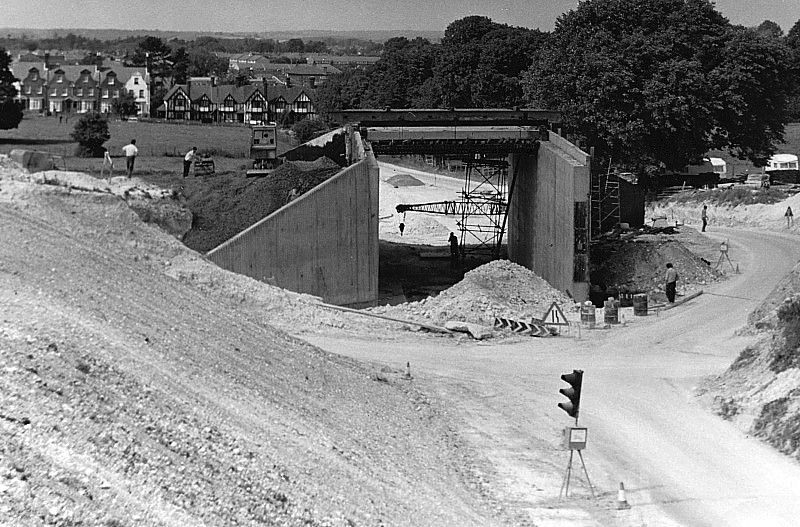

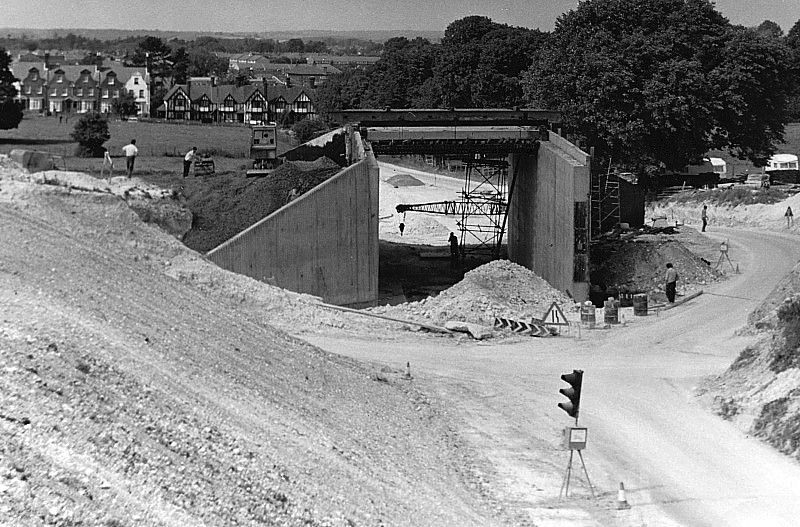

Above: the Hastoe lane

flyover under construction, July 1974.

Below: the

Tring Park footbridge under construction, September 1974.

Despite Tring Park being sliced in two, the town welcomed the respite

from heavy traffic while the attractive footbridges over the Bypass

ensured that Tring Park remained easily accessible. Indeed, the bridge

over the Bypass’s eastern end (shown below) has become something of an emblem, being

known locally as ‘The Gateway

to Tring’ . . . .

The Tring Bypass (A41), looking south from

the Icknield Way bridge

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES

1. Now the hardware premises of R W Metcalfe & Son.

2. Produced from 1919 to 1925 by the Cubitt Engineering Co. Ltd.,

located on the Bicester Road, Aylesbury. The 3,000 cars

manufactured and marketed by Cubitt were of an affordable price. A fine example

can be seen in the County Museum in Aylesbury.

3. The great workload placed on our railway network during WWI,

together with little opportunity or resources for proper maintenance,

left it in a sorry condition, and, when peace returned, it was losing

money. The government of the day aimed to remedy the situation by

imposing a merger on most of the 120 existing railway companies then

existing. Under what has become known as ‘The Grouping’, four large

railway companies were formed from this merger, the L&NWR becoming a

constituent of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (‘The LMS’),

which operated the West Coast Main Line.

4. The London Passenger Transport Board (LPTB) ― better known as ‘London

Transport’ ― was the organisation responsible for local public transport

in London and its environs from 1933 to 1948. It was replaced

(under the Transport Act 1947) in 1948 by the London Transport

Executive, effectively becoming nationalised but with considerable

autonomy. Control of public transport in London passed to

Transport for London (TfL) in 2000.

5. A comprehensive history of Tring’s bus services ― from the first

horse-drawn buses to the present day ― was published in five volumes by

John Savage in 2014. These can be consulted at Tring Local History

Museum.

――――♦――――

[Next page] |

|