This is not just another book

about gardening. A glance at the shelves of book shops,

charity shops, or public libraries shows that no further

volumes are needed. In any case, this author is totally

unqualified to offer any shred of advice on the subject. If

you wish to know when to prune your roses; how to prick out

your seedlings; the best way to scarify your lawn; or

whether or not to fumigate your greenhouse – please refer

elsewhere.

I have simply attempted to outline the story of gardening in

Tring and district from the late seventeenth century to the

present day. It has to be said that the town is not

especially known for any particular aspect of horticulture,

but in spite of this Tring gardening has a varied history.

This may be due to the fact that the very large private

estates in the vicinity had beautiful gardens, parks, and

walled areas. At the same time, allotment holders and

cottage gardeners added to the scene. Two world wars spurred

many to take up a spade or fork. In contrast, some

individuals in Tring have pursued their specialist gardening

passions. In attempting to squeeze three hundred years of

history into one small book, it is inevitable that some

aspects of gardening may have been left out, and if this is

so I apologise.

My thanks go to the many people who have contributed

information, photographs, and reminiscences, without which

the book could not have been written. Special thanks go to

Peggy Bainbridge, Michael Bass, Mervyn Bone, Alec Clements,

Grace Duckworth, Roger Dye, Peter Fells, Jill Fowler, Joan

Gregory, Martin Hicks, Angela Lloyd, Heather Pratt, Shirley

Read, Ann Reed, Rodney Sims, Carol Willmore, the staff of

the Dacorum Heritage Store, and the NatWest Bank.

W.M.A.

October 2006

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 1

The Early Years

|

What was Paradise? but a Garden,

an Orchard of Trees and Herbs, full of

pleasure, and nothing there but delights.

William Lawson, 1656 |

Before the seventeenth century about gardens in Tring.

Ordinary people were so busy struggling to make a living and to

support their families that no time was left for leisurely pursuits.

Most local effort went into farming the land, and any other

cultivation was solely for the purpose of growing vegetables.

Only the owners of large town houses or country estates could afford

the luxury of a garden, and so it was in Tring, as the first

reference to gardens of any sort is, unsurprisingly, those of

Tring Park House. The Manor of Tring had been

bestowed by King Charles II on Henry Guy, one of his finance

ministers. Access to the Treasury funds was tempting, and it

is said that Henry Guy appropriated money to build himself a

splendid new house surrounded by parkland and beautiful gardens.

A visitor at the time described Henry’s gardens as “of unusual

form and beauty”, but no other account survives.

|

|

|

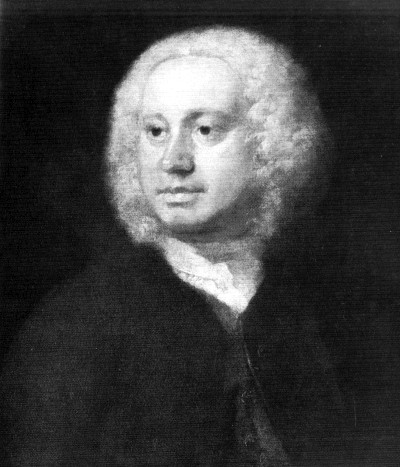

Charles Bridgeman (1690-1738)

English garden designer |

In 1702 the estate passed to Sir William Gore, and it was his son

who commissioned the services of Charles Bridgeman, the leading

landscape garden designer of the day. Working in conjunction

with the architect James Gibbs, Bridgeman created a fashionable

Baroque layout, covering 300 acres of park, 20 of which were given

over to gardens. An engraving of 1739 shows all the design

features, which included parterres, gravel gardens, a very large

straight–sided canal, softly–moulded lawns, and a formal woodland

with rides. Beyond all this, terraced slopes and extensive

avenues of trees led to an elaborate decorative building. To

the east of the house lay a bowling green, and an extensive walled

kitchen garden.

Just how much of Bridgeman’s ideas were carried out is not known,

but certainly enough for a guest at the time to observe admiringly:

“There

are 20 acres of gardens all full of fine slopes, with a canal

between and a Green House of eleven windows to front it; the House

is in the midst of the Park which is full of easy hills covered with

Beech and Oak trees, in which a canal of 110 feet broad is going to

be made to front the House; and the Park has 300 head of deer, and

the Gardens are so rich that there are always nine men and four boys

to keep them”.

Fashions change, and as the eighteenth century progressed the taste

for formal layouts with geometric lines and straight vistas fell out

of favour. The demand was for less enclosed spaces with more

views to the adjoining parkland. Large areas of water were

considered desirable, and streams and rivers were diverted or dammed

to provide natural–looking lakes. Sir Drummond Smith, the next

owner of Tring Park, followed the trend and swept away much of the

old design. For some reason the 300–metre avenue, running

north to south from the house, was allowed to remain and survives to

this day, as do both the obelisk (Nell Gwyn’s Monument) and the

portico of the summerhouse.

Britain’s increasing prosperity at this time meant that more local

gentry and London merchants were able to acquire land and build

large houses surrounded by gardens and parks. In 1764, John

Seare, the owner of The Grove at Tring, is known to have paid

Nathaniel Richmond, then a leading market gardener, £31 for

supplying plants from his London nursery. Two years later, the

property is shown on a map of Hertfordshire, but virtually nothing

is known about this fine house or its surroundings for, by the

beginning of the next century, all had disappeared. Four other

large country houses near Tring have gardens set in the natural

landscape, with little formal planting. These are the

late–Georgian properties Stocks House at Aldbury, and

Drayton Manor to the west of the town; and the Victorian houses

Pendley Manor, and Champneys at Wigginton.

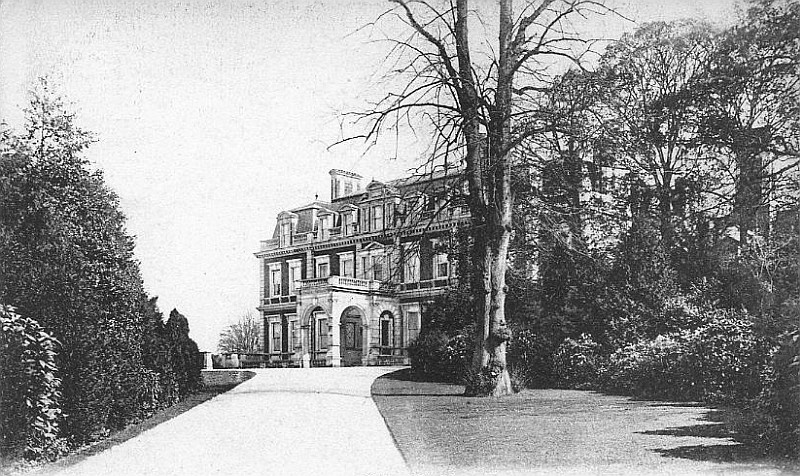

Stocks House, Aldbury, c.1903

When the successful novelist Mrs Humphry Ward and her husband moved

into Stocks in 1892 she enthusiastically described the house

and gardens to her father, but assured him “they are not grand in

any way”. However the account that followed describes a

layout far from modest, as she says it had “old–walled and

yew–hedged gardens, a small bit (i.e. 300 acres) of beautiful park,

and an avenue of limes like a cathedral aisle”. At a later

date T. H. Mawson, a fashionable garden designer of the time, worked

at Stocks, but many of his ideas were not implemented due to

cost. A cricket pitch was laid out for the use of the Wards’

son and his friends.

A late Victorian/Edwardian view of Pendley Manor

At Pendley some of the original planting is still to be seen,

with beech–lined drives and specimen trees including sweet chestnut,

Turkey oak, Atlas cedar, and Wellingtonia. Likewise at

Champneys many fine trees planted in the 1880s are now in the

full glory of their maturity. In the parks of both estates

were tennis courts, croquet lawns, and cricket pitches. In

properties of this type, the walled kitchen gardens contained large

areas under glass which included vineries and peach houses.

The kitchen garden at Drayton Manor enjoys a particularly

beautiful situation, with a backdrop of beech woods on the Chiltern

Hills. Although now crossed by the A41, Tring Park

still remains a enjoyable area in which to walk and appreciate the

landscape features. The grounds of both the hotel at

Pendley Manor and the health spa at Champneys can be

enjoyed by visiting guests. The old walled garden at

Champneys is given over to organic production of both vegetables

and fruit for use in the kitchen.

Champneys near Tring

(postcard)

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 2

The Horticultural Society

|

What a desolate place would be a world

without

flowers! It would be a face without a smile,

a feast without a welcome.

Clara Lucas Balfour, 1848 |

Tring Agricultural Association was formed in 1840 with aims of the

‘promotion of agriculture and horticulture and to reward industrious

labourers’. For nearly thirty years the Association carried

out its stated objectives, and the event mainly involved landowners

and farmers who gathered at the annual show on a site near Tring

Station. This was a regular date in the calendar of the

district, and was always well supported and well run.

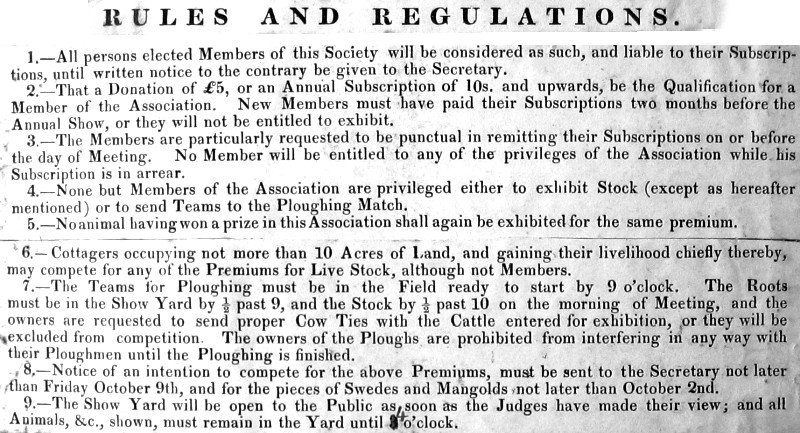

Tring Agricultural Association rules, c.1855

In 1868 an innovation was introduced when Dr Thomas Barnes, at that

time living with his family in Tring Park mansion, sponsored

a class for those in less affluent circumstances. Prizes were

offered for the neatest cottage and garden within three miles of the

Market House, the rent of which did not exceed £7 per annum.

From this small beginning, the seed was sown (forgive the pun) for

the foundation of Tring’s Horticultural Society.

As the years passed it was realised that the show would attract more

visitors if a site nearer to the town centre could be found.

By the time Rothschilds arrived in 1874, the show had steadily grown

in size and reputation, and it was then logical that it should be

held on their land. The following year, the Flower Show

classes relocated to Dawe’s Park (an area south of Park Road), and

fifteen years later the main Agricultural Show moved to the Park.

The Rothschild family’s benevolent attitude towards Tring was never

more evident than on Show days, when everyone was allowed to wander

at will through the Park; the gardens (see Chapter 4)

were open to the public; and famous military bands provided

entertainment. Nothing is so redolent of the fin de siècle

era as accounts written at the time when, of course, the sun always

shone from a cloudless sky; ladies wore gigantic flowery hats, and

twirled parasols; gentlemen sported blazers and boaters; all to the

accompaniment of selections of music from The Merry Widow,

Gilbert & Sullivan, and other period pieces.

In 1892 the Flower Show was renamed the Tring Horticultural &

Cottage Garden Show, and by the turn of the century the new event

was attracting around 500 people, who were rewarded by splendid

displays of flowers and vegetables set out in large marquees

decorated with ferns and palms from the conservatories of Tring

Park and Pendley Manor. As well as prizes for

garden produce, classes included bread, pastry, cooked vegetables,

and straw plait, and awards were presented for the best–kept

allotments in Tring and the surrounding villages.

“COTTAGE GARDENS SHOW: the Committee of the Tring Working Men’s

Club have just issued the preliminary notice of the annual show of

flowers, fruit, and vegetables, &c. This show has undoubtedly

given a great impetus to cottage gardening in Tring, and is now

quite an institution of the town. In the matter of allotments

Tring is singularly fortunate, as, owing to the liberality of lord

Rothschild and Mr. J. G. Williams, any man who has the leisure and

the inclination to cultivate a plot of ground can obtain the

necessary land at a mere nominal rent.

Recognising the importance of an allotment to a working man, the

Committee of the Club devote special attention to this particular

form of gardening. The allotments are grouped in six classes

for the purposes of the competition, and three prizes are offered in

each class. In addition to these prizes, this year Mr. George

Parrott, coachbuilder, offers a wheelbarrow as a champion prize for

the best allotment entered for the competition.”

Bucks Herald, 18th April 1896

The annual Cottage Garden Show encouraged club members to cultivate

allotments where, as plot-holders, they could acquire new knowledge

and skills, derive a sense of achievement from growing their own

seasonal produce, save on the household budget, and gain social

interaction with a community of like-minded people.

Obtaining fertiliser was not a problem for gardeners in the days of

horse power, and many cottagers believed that great results could

also be achieved by utilising the contents of the privy bucket.

They supported their argument by displaying excellent crops of

vegetables. Especially successful were tomatoes and cucumbers

which had the added advantage of being self–set, as it was well

known that pips from both plants pass undamaged through the human

digestive system. (Some did admit that application of this

form of manure was not exactly pleasant, but many householders owned

a special privy bucket which was designed with a long handle to

avoid slopping the contents.)

Tring Flower Show day, 1904

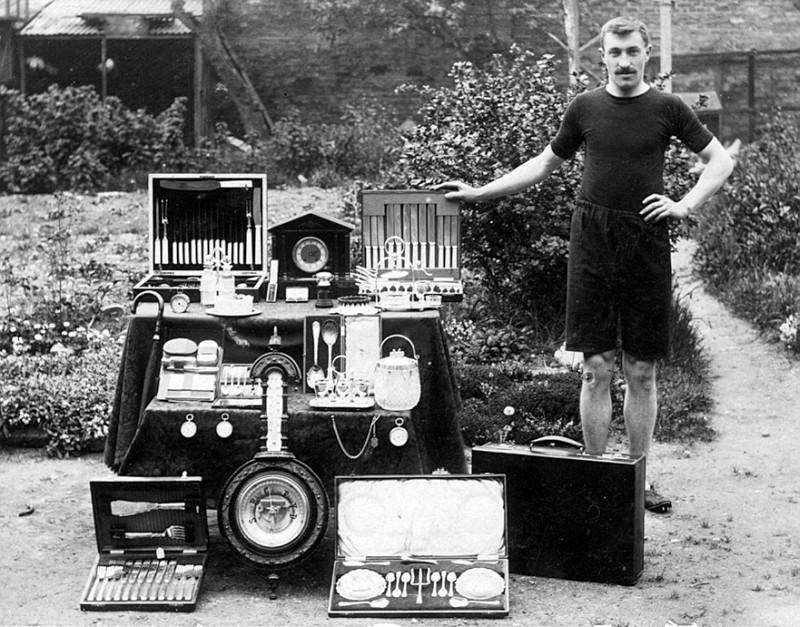

On Horticultural Show days Rothschild hospitality was again

generous, and visitors enjoyed a lavish tea under the trees, whilst

listening to selections played by the Tring Brass Band. This

was followed by athletic sports, giving the younger people of the

district an opportunity to show their prowess. Their efforts

were well rewarded as the prizes, often presented by Lady Rothschild

in person, were substantial, and the winner could expect a useful or

decorative item with his or her name engraved on an attached brass

plate. The prizes included canteens of cutlery, clocks,

tables, cut glass, suitcases, and inkstands.

Richard Wright of Langden Street, with trophies

won for athletics on

Flower Show day

When the first war broke out, most horticultural effort had to be

concentrated on vegetable–growing, and flower shows in Tring became

a fond memory. But in 1924 an inaugural meeting was held in

the Market Hall when a provisional committee of ten, chaired by John

Bly, proposed an open meeting to try and resurrect the society.

It rose like a phoenix, and soon

the shows of the pre–war years were again enjoyed. In the

second war, the Society continued in a limited way, encouraged by

the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries & Food. Now–famous

posters could be seen around the town, such as Dig for Victory

and On the Kitchen Front. People were encouraged to

switch on their radios early each morning and listen to gardening

tips. Advice was along the lines of “Garden peas that have

grown hard through lack of water or age can be put through a sieve

and made into excellent soup; Stew plums with no sugar, pulp, store

in hot clean bottles, and seal immediately; and Put down mothballs

as a deterrent for keeping away cabbage–white butterflies”.

The post–war years saw a large increase in membership, and shows,

now combined with fêtes, were held at different venues, including

Home Farm, Osmington School, and Christchurch Meadow.

Lectures were arranged in winter months, together with an annual

dinner and Harvest Supper. Several high–spots occurred during

this period, including the establishment of the popular Floral Art

section, and the broadcast from Tring of an edition of the

well–known radio programme Gardeners’ Question Time. A

panel of famous gardeners, chaired by radio personality Franklin

Engelman, attracted a capacity audience of 250 at Mortimer Hill

School. Around this time, the Society also entered a team in

the County Gardening Quiz held in different towns all over

Hertfordshire. Tring usually acquitted itself well; in 1968 it

lost by only half a point in the semi–final.

As the years passed, all the villages around Tring founded their own

horticultural societies and usually held one or more annual event,

often combined with a fête. Show days then were the highlight

of the village calendar, and potential exhibits would be carefully

nurtured and guarded. Enormous trouble was taken to match in

size and shape the number of vegetables stipulated for each class,

and these were washed in a little milk and the tops trimmed with

geometric precision. Early the next morning the whole lot

would be loaded carefully into a wheelbarrow and trundled down to

the village hall. No–one was much concerned that the prize

money was small – it was the award

of a precious red certificate that really counted.

The Aldbury Allotment & Cottage Garden Association mounted their

inaugural show in the Memorial Hall in August 1931. The fates

were not kind, and it transpired that this was decidedly not a good

year to chose for the first–ever show. A week before the

planned event a terrific hailstorm damaged much of the produce

prepared by hopeful exhibitors but, even so, 150 entries were on

display.

Wilstone’s society was founded immediately after the war in 1946.

The opening ceremony of the first show was performed by founder

member Dennis Noble, the international baritone, who for some years

made his home in the village. The 10th annual show and fête was

opened by local celebrity, Dorian Williams, and a record 520 entries

judged. On that occasion the weather was awful, with the wind

howling over the loudspeakers. These adverse conditions inspired a

Churchillian–type speech from Dorian, who commented “There is

nothing more English than the allotments in an English

village............ the constant fight against the weather to

organise these little shows is characteristic of the national spirit

of determination”. The 21st Show in 1967 was opened by actor

Wilfrid Bramble of Steptoe & Son fame, and the 25th Show by Melvyn

Hayes of It Ain’t Half Hot Mum. But times change and,

due to lack of support, the society was disbanded in 1986 when the

funds were transferred to the village–hall appeal. Other local

villages have managed to keep their shows alive, and these include

Wigginton Gardeners’ Association, Long Marston & Puttenham, and

Aston Clinton Horticultural Societies.

In the mid–eighties Tring Horticultural Society was still

flourishing with a membership of 645. All events were

well–supported and the Society added to its reputation by winning

first prize at Tring Carnival for its float “Gardening through the

Ages”. However, as the the new millennium approached it was

clear that the growing of vegetables and flowers for exhibition was

not the popular pastime it had been. Also, members were

reluctant to give time to serve on the committee, so the decision

had to be taken to wind up its affairs. Its end came in 2000,

much to the regret of many townsfolk who had always supported its

shows.

Despite the demise of the Society, garden enthusiasts in the town

can still pit their skills against each other. Tring Town

Councillors are asked to nominate attractive gardens in their wards,

and the entries are judged by a local celebrity. Challenge

cups are awarded each year for Best Garden; for the best Small

Garden (a cup presented by the late Trevor Marwood); and for best

garden in Eight Acres. The latter competition began in 1966

when the estate was newly–built, and the head of the firm of

architects who designed the development donated a challenge cup.

The following year the town Council established a new competition

for the best–kept garden by any tenant occupying a local authority

property in Tring. The first winner was Arthur Poulton of

Woodland Close who had only lived in his house for two years and had

inherited ‘a wilderness’ of a plot. He impressed the judges

with his split–level garden containing rockeries, greenhouse, garden

pool with picturesque rustic bridge, trellises, and wishing–well.

In recent years a new commercial venture for a flower show has been

tried in Tring at Pendley Manor. This is held in the four–acre

meadow at the rear of the hotel which is well prepared to receive

the professional exhibits. Flowers, plants, trees, cacti,

alpines, and bonsai are among the displays on show, as well as

stands selling water fountains, garden furniture, and arts and

crafts. The first event in 2003 was opened by television

gardening personality, Charlie Dimmock, who was on hand to answer

visitors’ questions on gardening problems.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 3

MARKET GARDENS AND NURSERIES

|

Seedsmen reckon that their stock in trade

is not seeds at all – it’s optimism.

Geoff Hamilton (1936–1996) |

In the mid–Victorian period several families named Marcham lived and

worked at humdrum occupations in Tring. One of the more

enterprising was Joseph Marcham, whose job as a gardener led him to

start a small business in Akeman Street. By 1850 Joseph was

able to describe himself in the local trade directory as a ‘gardener

and seedsman’. (In the early days Joseph’s only rival was an

elderly lady, Anna Missenden, who traded in groceries and seeds in a

small shop in Frogmore Street.) Joseph’s business prospered

and after a few years he relocated to Brook Street and established a

nursery which he ran for over 40 years. In November 1882

The Tring Telegraph carried the following notice:

“Joseph Marcham begs to acknowledge his sincere thanks to

the Gentry of Tring and Neighbourhood for their kind and liberal

support for the last 42 years. He begs to say that he has

given up his Nursery Grounds to his nephew W. Rickett. The

Shop and Business will be carried on as usual at 63 Brook Street.”

The Marcham expertise was passed on for two further generations, and

Arthur Marcham was responsible in the Edwardian period for laying

out many of the gardens of newly–built properties in Tring.

His son, Henry, received a good grounding in the trade at his

grandfather’s nursery. While still a young man, he spread his

wings and secured a job as garden foreman to the Duke of Devonshire.

He then moved on to become rose–grower to Lord Northcliffe, and

travelled further afield, engaging in important landscape work at

Castle Konospicht in Bohemia. Then he was appointed

inspector of three gardens belonging to Baron Alphonse Rothschild in

Vienna, where he held a very responsible position controlling a

staff of 204. During the first World War, he and his wife were

classed by the Austrians as enemy aliens and spent weary years in

separate internment camps. After the war he returned to

England and ran his own nursery at Carshalton, succumbing to heart

disease at the age of 54.

At the beginning of the twentieth century there were two market

gardens at opposite ends of the town. On the eastern side

Albert Westwood laid out a nursery on Mortimer Hill, very near the

site of Joseph Marcham’s original premises. He sold some of

his produce at his florist’s shop at No.18 High Street.

Albert’s business was later taken over by Frank Westron, trading as

a nurseryman, seedsman, florist, fruit grower, and retailer.

He was well qualified to describe himself as an all–round

horticulturist, as he had been brought up with gardening in his

blood. Born in 1875 at Taplow Lodge on the Cliveden

estate near the River Thames, Frank was the son of the head

gardener. He came to Tring in the 1920s and rapidly

assimilated into the life of the town as a town councillor and

church sidesman. He died in 1960 and left a home–made will

which, after his wife’s death, bequeathed a very generous sum to

provide “a home for the old people of Tring who have resided

there for years”. Due to legal complications and other

problems, it was over thirty years before fifteen bungalows were

erected on a redundant site in Mortimer Hill owned by Tring

Charities. The development is named Westron Gardens in

his memory. When Frank retired, his business and shop were

taken over by John Stewart, and the market garden area is now the

site of Nursery Gardens.

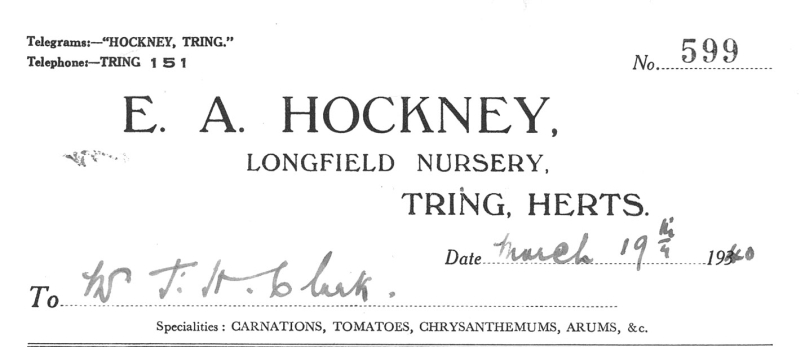

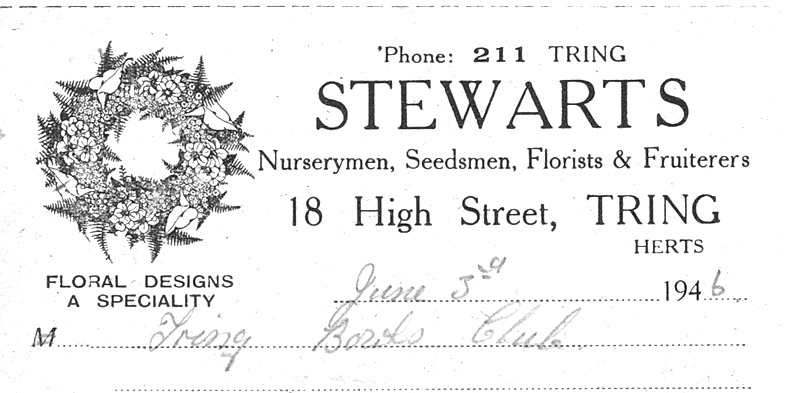

Edward Hockney’s and John Stewart’s

billheads

The other market garden was started by local builder, James Honour,

in 1897 in Longfield Road at the western end of the town. He

erected some fine large greenhouses, and from then until the nursery

was demolished, these were known locally as the ‘tomato houses’.

As the business grew the nursery diversified into other produce.

In the 1920s the business was acquired by the manager, Edward

Hockney, and later it passed to his son, Ted junior. To give a

flavour of those times at Hockneys, reproduced below is a brief

article that this author wrote for a Tring Local History Society

newsletter:

“A recent mention of the glasshouses in Longfield Road awakened

some old memories of the time when Ted Hockney junior, employed me

as a ‘worker’ during the school summer holidays. I quote the

word ‘worker’ as I cannot believe that a teenage girl who had never

so much as removed a weed from the garden, could have contributed in

any appreciable way to Ted’s business –

a budding Charlie Dimmock I was not. Looking back, I suspect

that he only gave me a job because he was a lifelong friend of my

mother, who had been born a few doors away in Longfield Road.

The Hockney family had always lived in the house adjoining the

business, and Mrs Hockney was remembered by older Tring residents as

a rather grand lady who habitually dressed in tasteful shades of

violet and mauve. The nursery became well established and was

especially known for tomatoes, cucumbers, and the Hockneys’ prize

crop – carnations. Tring

people, mainly from the western side of the town, purchased the

products direct by visiting a long, low shed where the tomatoes were

weighed out from ‘Covent Garden’ style round baskets. The

smell inside this shed was familiar and welcoming, a mixture of warm

baskets, earth, and firm ripe tomatoes. Whilst still quite

young, I was often sent round the corner to buy these, for those

were the days when small children could safely run errands alone.

By the time I came to work at the nursery, Ted junior was a

middle–aged bachelor, shy and kindly. His sole companion was

Bill, a mongrel dog of independent spirit, who daily took himself

off for long walks – crossing the

main road, trotting through the Aylesbury Road allotments, and far

into Stubbin’s Wood and beyond.

Until that time my only experience of glasshouses was limited to

visits to Kew. Ted’s were much smaller, but still vast enough

to overawe me. The work I was given was tedious, but not

arduous. It consisted of de–shooting growing tomato plants,

pricking–out young lettuces, and for ever watering the cucumbers.

This latter was not pleasant, for cucumbers thrive best in extremely

hot steamy conditions – not good

for my teenage experimental hairstyle. Understandably, I was

never allowed to set foot inside the precious carnation houses.

The four other employees treated me with amused tolerance and were

always kind when we shared our tea–break in a cramped but cosy shed,

although it seemed to me that sometimes they did not get along with

each other. The two men endlessly argued about football,

whilst the two women seldom spoke to each other at all.

Every day without fail a welcome break came when Ted, who must have

had a very sweet tooth, asked me to fetch a bag of cakes from

Atkins, the Bakers in Western Road. The selection was left to

me and, anxious to do the right thing, I used to make enquiries

along the lines of “Do you like doughnuts, Mr Hockney?”

Whatever variety I asked about, Ted always said he did. With

the cakes and buns stowed in the saddle–bag of my bike, I peddled

back hurriedly. I was concerned to keep my job, for my wise

parents insisted that if I wanted any extra spending money (mainly

for clothes – pop groups had yet to

be invented) I must earn it myself. Occasionally, when I

returned to deliver the cakes to the back door, I would find Ted

being furiously berated by his housekeeper for some misdemeanour.

On one memorable occasion a row took place with the whole length of

a greenhouse between them whilst, in the middle, I kept my head down

and carried on with my de–shooting.

Ted is remembered for his fanatical interest in both hockey and car

driving. Fearless at each pursuit, he twice landed himself in

hospital with serious injuries after accidents in his MG sports car,

and could also claim the doubtful distinction of three speeding

fines on the same day.

Alas, the characters and the nursery are now gone, and modern houses

stand on the site, now Longfield Gardens. The Hockney family’s

house has changed hands several times, and the familiar

‘thump–thump’ of the artesian well alongside Donkey Lane is no

longer heard. Lorries from Tring Station collecting the round

baskets of tomatoes and crates of carnations at exactly 3 p.m. every

day have also ceased to trundle up and down Longfield Road.”

|

|

|

John Batchelor,

founder of the Tinkers Lane

Nursery |

The early history of Batchelor’s nursery in Tinkers Lane, between

Wigginton and Tring, is largely a story of one man’s enterprise and

determination. John Batchelor was born in 1904 in Heath End,

and received a basic education at Hawridge village school. He

obtained a job at a large house in Berkhamsted, working as a

gardener and chauffeur, and at the early age of 20 fell in love and

married the cook (a wise choice). As a wedding gift from their

kind employer, the couple received half an acre of ground in Tinkers

Lane, on which John resolved to start his own landscaping business

and build a bungalow for his future family.

By 1925 both projects were well under way and, as John had no means

of transport except his push bike, he hired a lorry to carry stone

from the Cotswolds with which to build rockeries for his customers.

He also supplemented his income by keeping chickens, turkeys, pigs,

and a cow. The latter proved a particularly good source of

revenue, as John was able to sell milk for use at nearby Champneys

health spa, and in return collected their waste for use as

pig–swill. The nursery side of his business was established in

1932 when he bought three redundant greenhouses from the famous

Lane’s of Berkhamsted for £5. He added a further acre of

ground to his existing holding, and began to specialise in rose

growing. He became so well–known in the district that he was

asked to judge at many notable horticultural shows. This

activity was interrupted by the Second War when all production from

market gardens was channelled into vegetable growing. Later,

three more acres and a wood were added, which included part of the

historic Grimsditch. The nursery continued to expand with most

stock being grown on site from seeds, cuttings, and grafts.

John Batchelor was still working at the nursery well after his

eightieth birthday, alongside his son, Tom, and three grandsons.

The total area now covers 12 acres. Today, when ‘garden

centres’ often combined with a DIY superstore seem to be the

preferred choice of many, Batchelor’s nursery remains a traditional

market garden where good plants may be purchased at sensible prices.

Seventy years after John first set up his enterprise, any local

gardener can now say simply “I’m just popping up to Batchelor’s”,

and everyone knows just what he or she means.

In the years immediately after the second war, a Swiss named Boudet

acquired seven acres adjacent to Kiln Lane, Cholesbury, where he

erected three greenhouses. He built an adjoining bungalow

where he lived with his wife and her pet hen. His crops grew

well, for Boudet maintained that there was no better manure than

watered–down cowpats, which he collected from nearby Kiln Farm.

Thanks to this method, he was able to grow splendid Rhubarb plants

to provide the main outdoor crop.

Another enterprise was that of Robert Hedges, who owned a

greengrocery business in Miswell Lane, Tring. In the mid–1930s

he bought an adjacent site which included two small greenhouses and

an old wooden shed with beams covered with nails, where rabbit skins

were once hung to dry. He added two larger glasshouses, one

from The Bothy (see Chapter 4) and, with

the addition of a propagating house and brick cold–frame, soon

started to grow a variety of crops to stock the Hedges family shop

(nowadays The Old Stables). One of the original

greenhouses was converted to a boiler house providing heat for the

other houses and steam for sterilising the soil. His nephew

remembers that someone had often to rise at 3 a.m. in bitter winter

weather to check that the boiler was functioning properly.

Miswell Lane Nurseries, 1960s

Robert’s nursery was a success, and he employed three full–time

workers, assisted at busy times by members of his own family.

The crops included vegetables, salad plants, cucumbers, and

tomatoes, as well a selection of pot and bedding plants, and cut

flowers. When a large piece of ground (now Cobbett’s Ride)

opposite the existing business became available, the nursery gardens

were expanded. During the second world war chickens and a few

pigs were also kept, their swill being prepared on the boiler in the

old greenhouse. Some older Tring residents still have good

memories of Hedges’ produce being freshly picked in the morning,

sold in the shop during the day, and on their supper tables the same

evening.

Only one traditional nursery remains in the Tring area (Batchelor’s

in Tinkers Lane), and one modern garden centre at Bulbourne has been

established in recent years. However, for those not fond of

DIY in the garden, services of landscape designers are in demand.

Charles Hogarth, whose business is based within the old walled

garden of the Tring Park estate, is a member of the Association of

Professional Landscapers. His work often features waterscapes

and nightscapes, and has won several awards, including the APL

Design and Build Commercial prize for the creation of a beautiful

layout at Bedford Butterfly Park.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 4

TRING PARK GARDENS – THE ROTHSCHILDS

|

A garden

that one makes oneself becomes

associated with one’s personal history and

that of one’s friends, interwoven with one’s

tastes, preferences, and character.

Alfred Austin (1835–1913) |

Tring Park Mansion,

South Front, c.1900

Unlike many of his relatives, the first Lord Rothschild was not a

passionate gardener, and practical matters relating to farming and

agriculture held far more appeal for him. However, in the 1880s when

Tring Park Mansion was remodelled, substantial alterations to the

gardens were also undertaken. As the new landscape design matured,

Nathaniel Rothschild did become more interested and in fact grew

knowledgeable about the names and qualities of shrubs. His wife is

known not to have favoured too much formal planting, and at the

south front of the house except for a few flowerbeds (sometimes

displaying the Rothschild racing colours of blue and gold), the

landscaping remained soft. The lawn was extended and a new ha–ha

constructed to allow an uninterrupted view to the wooded escarpment

on the far side of the park.

Tring Park Mansion,

North Front c.1900

The area known as ‘the pleasure gardens’ to the west and north of

the house was extensively remodelled and replanted. A description

written at the time records that they featured a summer house and an

Italian garden and fountain. A sunken path, lined with flint, led to

an under–pass which survives. This ran beneath the drive

leading to the stables, and gave access to a winter tennis court; a

topiary garden clipped into the shapes of tables, chairs, and chess

pieces; a Dutch garden; an Elizabethan garden; and a number of other

areas. An account in the gardening press at the time says:

“Each of

these little gardens is complete in itself; once entered, the whole

comes under the eye in an instant, but nothing is seen of the

gardens beyond, for each of these separate designs is encircled by

an irregular bank, planted with rare Conifers and shrubs, faced with

flowering plants, Lilies, and Roses, and in all cases with as many

annual or perennial sweet scented plants as possible”.

The account

reads on to wax lyrical about all the chosen bedding, including

purple Clematis, Begonias, Violas mixed with silver Pelargoniums,

Cannas, Marguerites, white Nicotiana, and Sweet–peas.

Lily Pond and Turf Steps at

Tring Park

That same year, a correspondent from The Gardeners’ Chronicle

visited Tring Park, and in his article he comments with surprise on

the modest entrance and approach to the estate. But once beyond the

stables area, matters obviously lived up to his expectation of a

home appropriate for the richest man in the British Empire. The

following extracts give a good description of the gardens at that

date:

“A broad new carriage drive leads to where a grand entrance to

the house is evidently meditated, and on the right of this approach

is a bank of evergreens. It was planted only eighteen months since

with large shrubs of Yew, Bay, Box, and Aucuba japonica

............. Passing round the house you will find a lawn, much

enlarged recently, and clipped about by a very unlevel park,

beautifully planted with clumps of Limes, animated by deer and

shorthorns, and enclosed by masses of encircling Beech woods on the

high ground which bounds the view.

........... Among the proofs of outlay, as well as of excellent

taste, are the numerous costly shrubs around the house, including

the bushes of Golden Yews grown from cuttings, as well as the much

rarer seedlings. I dare say thousands have been expended in shrubs

lately ...... Numbers give only a mechanical idea of works of

planting like those which Mr Hill (the head gardener) with his men

and long hose has brought to such a successful issue; but it may

please nurserymen, and make their mouths water, to repeat that 500

Golden Yews, costing a great sum, have been planted here, and 10,000

bulbs of Gladioli set in the shrubberies to enliven them. ..........

I can only say that it (the garden) is filled with costly “things”,

and in standing before the largest Japanese specimen, which is many

times repeated in smaller sizes, one cannot help counting the cost. It is the beautiful Retinospora obtusa nana aurea and is worth seven

guineas. The double Spanish Gorse is used as an edging of this grand

clump of shrubs, and I observed several specimens of weeping Yew on

stems one foot or more high, and then spreading horizontally

..............

The kitchen gardens are on the roadside near the town, and will soon

be entirely shut in by walls, and enlarged from three to six acres. The glasshouses are numerous, and the management unsurpassed. Five

houses are devoted to Orchids, and two entirely to Carnations, one

of them to the favourite Malmaison. The foliage plants, Crotons,

Caladiums, Alocasias, Dracænas and others were superb, and the

varieties of Begonia and Coleus looked charmingly bright. I believe

that a London firm decorates the London house so far as pot plants

are concerned; but the cut flowers are sent from Tring, and two

houses of Adiantum ceneatum are required for the growth of Fern

foliage by the bushel.

There are five vineries where the Muscat of Alexandria Grapes, of

five years’ growth, are as good as can be, and the adjoining Black

Hamburgs too having this year the largest berries yet produced here.

In the Fig-house the first crop was just over, and the second coming in ............. The Orchard-house is simple and comparatively

inexpensive. It consists of 135 yards of wall, enclosed by glass,

having hot-water pipes to keep the temperature above freezing, and

making all the wall fruit – Apricots, Peaches, Pears, and Plums –

perfectly secure.”

The article goes on at great length in the same vein, and also makes

mention of ‘the cottage’, the home of the unmarried gardeners. This

was replaced in 1905 by The Bothy, a fine new building where the

boys were well-cared for by a housekeeper. It survived for almost

one hundred years, until demolished to make way for a supermarket.

The Bothy c.1905

By the time of Lord Rothschild’s grandson, matters were beginning to

change. By that date, death duties and the effect of a devastating

world war had taken their toll. A description written by Bob Poland,

recently appointed as Greenhouse Foreman at Tring Park, gives some

idea of how things were.

Arriving at his new job one Saturday evening in November 1934, he

was stunned when the head gardener called for him at The Bothy at 9

a.m. the next morning. He was instructed to start cutting fresh

flowers ready to be sent to the Rothschild houses in London and

Cambridge. On enquiring when they were wanted, he was told to leave

them in water overnight, but to be up at 3 a.m. the following day

“as the van calls at 6.20 a.m.” and only two men would be available

to help. Bob Poland’s new empire was larger than anything he had

experienced before, and he describes the glasshouses with 18 miles

of piping and boilers consuming 30 tons of coke each week, all

shovelled by hand. These glasshouses were not as they had been in

their heyday, and Bob recounts they “were in an awful state with

every known greenhouse pest – thrips, mealy bug, red spider, and

millions of ants”. In an attempt to rid the gardens of pests, he

persuaded the head gardener to pay the men so much each for the

tails of rats, mice, moles, and for Queen wasps.

Once the major problems had been dealt with, Bob came to enjoy his

job as his duties were varied. When the family was in residence, his

responsibilities included supplying and arranging all the floral

decorations in the house. Busying himself in the flower room on the

ground floor of the mansion, Bob provided the sumptuous arrangements

that were changed twice a week, and those in the dining room once a

day, or sometimes twice. At the festive season a huge 30 ft.

Christmas tree stood in the centre of the staircase well, and

hundreds of flowering pot plants were used to decorate wherever

space permitted.

In the second world war not much time or effort could be spared for

gardening, and the grounds of Tring Park became neglected and

overgrown. During the conflict the staff from the Rothschild bank in

the City of London moved into the house, and the stables were used

by the Home Guard, the ARP, and the Red Cross. Shortly before the

war, the 3rd Lord Rothschild had offered Tring Park house, grounds,

park, and woodlands as a gift to the British Museum of Natural

History. The committee appointed to consider this did not accept it. The mansion

later became the Arts Educational School; part of the

‘pleasure gardens’ was dedicated as the Memorial Gardens (see

Chapter 12); The Bothy was used to house engineering staff from the

Royal Mint Refinery in Brook Street; and the route of the A41 bypass

sliced through the park. Like many similar estates all over the

country, the golden days were over and nothing was ever the same

again – sic transit gloria.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 5

HEAD GARDENERS

|

A Gardener’s Work is never at an end;

it begins with the Year, and continues to the next.

John Evelyn (1620-1706) |

For many years, the pretty Regency house with Gothic-style windows,

was the home of successive head gardeners on the Tring Park estate.

It enjoyed an open aspect and was not shielded from the London Road

until much later, when high brick walls were built to enclose the

entire kitchen garden. During the early Victorian period the

various occupants included William Brown, William Ivory, and James

Smith, who also ran a seed merchant’s shop in the High Street.

The privilege of living in the Garden House did not come

easily because, on any large country estate, the head gardener was a

figure of immense importance, whose knowledge of gardening matters,

control of men, and organisational skills were expected to be

all-embracing. But in 1877 this did not prevent the Rothschild

family appointing to the post a youthful 27-year old Gloucestershire

man, Edwin Hill.

The Garden House c.1905

For the next 27 years Edwin reorganised and maintained the grounds

around the Mansion. As his experience grew, he became

recognised as a well-respected member of his profession, and was

rewarded by being elected to the committee of the Royal

Horticultural Society. He also laid out the gardens of the

newly-built Louisa Cottages in Park Road, and those of the

Isolation Hospital on the road to Little Tring. He acted as

Secretary of the Cottage Garden Society (see Chapter

2), an organisation close to Lady Rothschild’s heart, and was

expected to arrange the athletic sports on show day. Edwin

died at the early age of 54 and his obituary appeared in the

Gardener’s Chronicle magazine.

Edwin was succeeded by his assistant of eight years, Arthur Dye, who

came to Tring Park with the very best credentials. Born

in Norfolk, he started his career in the Royal Gardens at

Sandringham and later moved to Royal Lodge, Windsor.

When he arrived to take up his new position, Arthur and his wife

were tenants in one of the Louisa Cottages but, after Edwin

Hill’s untimely death, they moved to the Garden House within

the walls of the kitchen garden. Living in this splendid house

had, at times, certain disadvantages. On spring nights when

the apple-blossom was in flower, a bell sometimes sounded a warning

that the outside temperature had fallen below freezing point: Arthur

then had to leave his warm bed to ensure that fires were lit in the

orchards. (Propped up in his bedroom was a shotgun, which he

used to despatch any unwelcome Glis Glis who trespassed into

the loft space.)

Arthur Dye, head gardener at Tring Park,

with his family

His new responsibilities included the welfare of the unmarried

gardeners living at The Bothy (see Chapter 4). Liaison

with other senior staff members such as the chef and butler were

also part of the job. One very special task each year was a

visit to Buckingham Palace, bearing Lord Rothschild’s gift of

flowers to decorate Queen Mary’s breakfast table. Arthur

remained head gardener for forty years, and on his retirement moved

to a Rothschild property, Woodlands, in Chesham Road,

Wigginton. There he enjoyed 25 years tending his own large

garden where he waged a constant war against Wigginton’s rabbit

population.

In the summer months it was the practice for owners of large houses

to open their gardens to the less privileged local folk of the

district. These events were greeted with mixed feelings by

head gardeners. Their natural pride and pleasure in

compliments, were weighed against possible hazards to their precious

plants. At Tring Park during the annual Agricultural

and Flower Shows, ‘Freedom of the Park Day’ meant all could wander

around the grounds and gardens, but some very necessary preparatory

work had to be done. The park was home to a variety of exotic

creatures belonging to Walter, eccentric zoologist son of Lord

Rothschild. Throughout the year kangeroos, emus, and other

animals roamed freely, but of course had to be kept under control on

the great day. Beforehand, an army of gardeners’ boys were

deployed to clean up the park, in a thoughtful attempt to preserve

the Sunday-best boots and clothes of the visitors.

It was also the case that head gardeners did not always appreciate

the largesse shown by their employers towards the general populace,

especially when children were involved. One hot summer, the

owner of Stocks House at Aldbury, the writer Mrs Humphry

Ward, a typical example of a Victorian lady bountiful, had the idea

of opening her kitchen garden and allowing the village children to

visit her strawberry beds. In spite of the disapproving eye of

her head gardener, Daniel Keen, they took full advantage of the kind

offer. His apprehensions were realised and he was obliged to

send the children packing for trampling his plants. Mary Ward

must have listened to his woeful description of the episode, as the

following year a better idea was suggested. The village

children were invited to a strawberry tea with cream, laid out on

long tables on the lawn of Stocks House.

Daniel had already been at Stocks for fifteen years before

the arrival of the Wards in 1892, and he lived long enough to gather

the branches of wild cherry that decked his mistress’s grave in

1920. In summer he often worked for fifteen hours a day, and

his simple answer to his employer’s protestations was that he could

not bear to see his plants die for lack of watering. He grew

to know exactly what would most please Mary Ward, and at

Christmas-time filled the house with hyacinths, narcissus, and banks

of azalea. He also achieved wonders in the walled kitchen

garden, as large amounts of produce were sent from Tring Station to

the charitable settlement for children that Mary Ward had founded in

London. During the war Mary and her daughter between them

devised a scheme of “war economies” which was implemented

vigorously. Timber was felled, potatoes grown, jam was made,

and garden fruit shared with the villagers of Aldbury. As all

the gardeners were serving in the army, the family helped Daniel by

planting out bedding and seedlings, and even the butler was

recruited to cut the lawns.

Daniel Keen was not alone in his devotion beyond the call of duty,

as gardeners in charge of extensive grounds surrounding large

country houses often seemed to love these gardens as much as their

own modest plots. The same feeling was brought to Drayton

Manor by Thomas Bateman, who tended the gardens until well past

his eightieth birthday. Tom, who had been in the employ of

Miss Alice Rothschild at Eythrope Park, came to Drayton on

the extreme western edge of Tring in the mid-1930s. With his

wife and young daughter, he settled in the lodge house at the

entrance to the drive in Aylesbury Road. He was proud of his

place of work, and with great enthusiasm set about organising the

lovely gardens, which had far-reaching views towards the Chiltern

escarpment.

The second world war changed everything when Tom left to serve in

the army, and Drayton was converted to a hospital for wounded

soldiers. However, the grounds continued to be enjoyed, as

every summer fêtes were held with a variety of activities designed

to help cheer up both the convalescent soldiers and the residents of

Tring. (These carried on for a few years afterwards, and in

the early fifties Godfrey Wynn, the celebrated broadcaster,

performed the opening ceremony.) After the war, the house

stood empty for two years before becoming a school for blind

children. While it was unoccupied Tom kept an eye on the

premises, and on more than one occasion he glimpsed the resident

ghost that all old houses claim. This took the form of a Grey

Lady flitting through the upstairs rooms. When the house

reverted to a private residence in 1957, the Batemans left the lodge

to live nearby. Tom continued to look after the gardens, and

remained until his wife’s ill-health forced him to retire. The

Batemans loved Drayton Manor so much that their

daughters thought it fitting that their ashes be buried in the Manor

gardens.

At the end of the Victorian era, when the Williams family of

Pendley Manor departed in August to shoot grouse in Scotland,

the gardens were opened to the public on several occasions.

The head gardeners (Henry Amos, followed by Frederick Gerrish)

always received great compliments on the appearance of their

gardens, but kept an eagle eye on proceedings. As the tennis

courts, bowling green, and croquet lawn were also open for the use

of all, they were wise to do so. Around the 1920s the position

of head gardener was held by Thomas Westcott, whose son Douglas was

for many years the star fast bowler of Tring Cricket Club.

In the centre of Tring once stood a large house, Frogmore,

which took its name from the street in which it was situated.

It was the home of Thomas Butcher, owner of the town’s private bank,

established in what later became the NatWest building in the High

Street in the 1830s. Thomas at first lived over the premises

enjoying the large garden area behind, but when his son inherited

the estate Thomas took advantage of the natural springs at the

bottom of Frogmore Street to include several water features in

Frogmore’s overall garden layout.

OS map of Tring (1877-79)

Frogmore is shaded red, the Parish

Church green, and the springs blue

At the turn of the century the head gardener was Joseph Reeve, a

local man who had been born in the now-vanished hamlet of Lower

Dunsley (once diagonally opposite the Robin Hood). He

was also responsible for overseeing the maintenance of the large

garden at the rear of Butcher’s Bank in the High Street.

Joseph lived with his family in one of a pair of pretty cottages

opposite The Black Horse. He was expected to supply

choice examples of fruit from the orchard, and vegetables from the

kitchen garden to exhibit in the local horticultural show (see

Chapter 2). Along with other head gardeners

in the area, he enjoyed considerable success. However, their

names never appeared on the winner’s certificate or challenge cup,

for it was always their employers who received the credit. In

any case, all Joseph Reeve’s efforts were swept away in 1956 when

Frogmore, the grounds, the water gardens, the gardener’s cottage,

and 18 acres of land were sold for redevelopment.

Joseph Reeve, head gardener at Frogmore,

with prize-winning apples

In an account of January 1902 we learn that less-exalted gardeners

were eager to learn from these acknowledged experts. One cold

evening a large and attentive audience gathered in the Boys’ School

at Tring to hear one of a series of lectures arranged by the local

Technical Instruction Committee. The speaker, Hedley Warren,

head gardener to Lady de Rothschild of Aston Clinton House, took

‘Cottage Gardening’ as his theme. Hedley did not talk about

subjects we now associate with olde-worlde gardens such as pretty

hollyhocks and delphiniums, but concentrated on the all-important

practicalities of soil, manures, and garden pests. He was

helped in his task by Frank Grace who operated a magic lantern which

illuminated diagrams on to a suspended white sheet.

Before the age of Women’s Lib, the gentlemen of Tring Park Cricket

Club proved what an enlightened group they were. For the first

time in the 120-year history of the Club, a female groundswoman was

appointed, with complete responsibility for the total four-acre

area. Mrs Elsie Gooch had been trained at Suttons (famous seed

merchants), and later was appointed gardener to F. J. Rodwell who

owned Tring Hill Café (renamed The Crow’s Nest).

Her new duties included preparation of the pitches; care and

maintenance of the table; re-turfing the ends after each game; and

planting and tending the flower beds in front of the pavilion.

At the end of the first season, members expressed themselves well

satisfied with their new groundswoman, and from then on Elsie,

sitting on her motor-mower, became a familiar sight to passers-by in

Station Road.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 6

TRING RAILWAY STATION GARDEN

|

And in my flower-beds, I think,

Smile the carnation and the pink;

And down the borders, well I know,

The poppy and the pansy blow.

Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) |

Tring Station flowerbeds

Gardens have been a feature of British railway stations for more

than a century. In past times these displayed anything from a

few milk churns full of geraniums to an intricate French knot

garden. Railway companies encouraged their staff to create and

maintain station gardens by offering prizes for the best examples.

All could participate – the

station-master, porters, ticket clerks, and signalmen. The

judges often used track-inspection carriages (nicknamed ‘glass

coaches’) to travel the length of the line, viewing exhibits.

In the summer months, rail passengers made special train journeys

just to admire and appreciate the efforts of the station staff.

In 1910, the heyday of the golden age of travel by steam, the London

& Northwestern Railway Company announced that a sum of money would

be allocated for the purpose of making stations more attractive.

Many station-masters in the district welcomed the offer and adopted

the scheme with enthusiasm. Not only was this an appeal to

their Edwardian pride, but cash prizes were to be provided by the

recently formed L&N.W.R. Southern Division Horticultural Society, as

well as an award for the best platform in the district.

At Tring, station-master Bradley set to work with a will. This

was no mean task, as the three platforms at his station totalled

about a mile in length. He drew up a design, and an appeal

went forth to the principal residents of the area for trees, shrubs,

plants and everything else necessary to complete his ideas. Mr

Bradley was not short of willing helpers, as eleven of his staff

were keen gardeners and they planned to enter exhibits of their own

at the the railway company’s summer show at Pinner. An account

of the time relates “they all placed their services ungrudgingly

at the disposal of the station-master, and worked with hearty good

will to carry out his plans”.

Some trees and shrubs were planted in the ground, while others stood

in large tubs. Hanging baskets were suspended from the

platform canopies; stands of flowering plants were placed in

suitable spots; and fern rockeries were erected in several hitherto

bare corners. Unsightly banks were filled with trees and

plants, and on the centre platform a large grotto, made of Leighton

sandstone, was covered with plants in bloom.

The area in front of the station-master’s own house was included in

the judging, and planted out with some nicely-arranged flower beds.

Berkhamsted, Cheddington, and Boxmoor were other local stations

entered for the competition, but it is not recorded who won in 1910.

Whatever the outcome, the station gardens at Tring were planted,

maintained, and enjoyed for many years afterwards.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 7

HERBS AND WILD PLANTS

|

Lavender hanged up in houses, it doth

very well attemper the aire, coole and make

fresh the place to the delight and comfort

of such as are therein.

John Gerard, 1597 |

It may be surprising to read that the sometimes not-so-fragrant air

of Victorian Tring was once scented with aromatic herbs. What

was considered ‘the most fertile field in Tring’, an area bordering

the ancient stream in Brook Street, was given over to the growing of

herbs for use in scent and other products. Around 1830 an

enterprising gentleman named Henry Narraway opened a small factory,

or lavender mill, in a dilapidated property adjoining a mud-walled

cottage which was the original place of worship for New Mill

Baptists. As well as the field in Brook Street, he grew

lavender on Tring Hill at a site close to the right-hand turn to

Drayton Beauchamp. This area was especially suitable for this plant,

for lavender can thrive on a thin chalk soil providing it enjoys

sunlight for several hours each day.

Lavender mill off Brook Street, New Mill

Other herbs grow well in these conditions, and some years later at

Pendley Beeches a natural bed of Belladonna was exploited for

commercial reasons. This poisonous alkaloid plant produces

atropine, a mildly anti-spasmodic drug extensively used in

pre-medication. The bed at Pendley was harvested and

replanted, and was reported to produce a leaf and root of better

quality than the imported Balkan variety. During World War I,

the benefactor from this activity was the Red Cross Society in

Tring. The same Belladonna bed at Pendley was re-discovered in

the second war and again harvested for use by military doctors.

Another, unnamed, Tring entrepreneur hit upon the discovery that

Hollands gin was good for the treatment of lumbago and rheumatism,

ailments then difficult to relieve. His researches led to the

fact that it was the addition of the juniper berry to gin which

produced the effect, eliminating acids from the blood through the

kidneys. He assiduously collected large quantities of these

berries from the Halton hills with the idea of producing a patent

remedy, but found that the supply was limited, even if he searched

all the slopes of the Chilterns. To acquire sufficient

quantities of berries meant dense cultivation of the juniper plant,

and also a considerable outlay of capital. Apparently the

would-be inventor then found that his idea was not entirely

original, as in fact sixpenny-bottles of Oil of Juniper were easily

obtainable from any Boots’ chemist shop.

Gathering wild plants was an important and useful activity during

the first world war. In 1917 the headmaster of Tring School

was asked to arrange the collection by pupils of horse chestnuts.

(It is likely to suppose that the boys kept the choicest conkers for

themselves). The active ingredient of the horse chestnut is

aescin, long known to relieve a variety of unpleasant conditions,

including vein problems, inflammation caused by arthritis and

swellings, and fevers.

The following autumn the local Food Control Committee extended the

request to include blackberries, and again the headmaster was

appointed as agent and organiser. Parties of children were

despatched to the hedgerows of Tring, their efforts totalling 190

lbs. which all went for jam-making. J.G. Williams of

Pendley Manor encouraged the children’s efforts by offering a

silver trophy to be awarded to the local school contributing the

largest amount. W. J. Rodwell of Tring Brewery acquired 12,000

redundant wooden butter boxes for transporting the blackberries, and

engaged women and girls to carry out the necessary sorting and

repair work.

Herb gathering was again very necessary in World War II when the

herbalists of Britain could no longer obtain their supplies from the

Continent. The wife of a Tring doctor, Mrs O’Keefe, and Lady

Craufurd of Aldbury organised the collection of wild plants for

medicinal purposes. Children were eager to help, and glad to

supplement their meagre pocket-money by the two-pence or

three-farthings a pound that the dealers paid. Ladies from

local Women’s Institutes also helped with the collection, and the

results of their efforts were taken in half-hundredweight sacks to a

mill, or furnace, at Dunstable. Below are a few examples of

the plants that the Government requested:

Yarrow (tonic)

Shepherd’s Purse (anti-scorbutic, stimulant, diuretic)

Camomile (carminative, sedative)

Burdock (blood purifier)

Pilewort (self-explanatory)

Digitalis (heart medicine)

Ragwort (cough medicine)

Elder Flower (diuretic)

Coltsfoot (cough medicine)

Belladonna (narcotic, diuretic, sedative)

Poppy petals (cough medicine) |

This last plant was financially the most worthwhile as the petals

fetched one shilling a pound. But as it took 200 petals to make up

one ounce, the money was not earned easily.

Stinging nettles were also on the list, but it seems that Wilstone

W.I. members were the only ones to agree to this rather unpleasant

work. This was a pity as the plant could be put to three different

uses - as a diuretic and astringent; in animal feeds; and,

importantly, as a green dye for use by the Army in camouflage

sacking. The watery ditches around the Wilstone area were a good

source of Meadowsweet, which was used as a remedy for children’s

diarrhoea. The plant that the ladies most enjoyed gathering was

Sweet Marjoram, used as a tonic or a stimulant, and it was said that

nothing was more pleasant than searching out this fragrant herb on a

hot summer’s day.

Some families gathered wild plants for their own use, and these

included the dandelion. This plant had long been known as a general

stimulant to the system, and was useful as both the leaves and roots

can be used. It was taken as a general tonic in either an infusion

or an extraction, and also fresh leaves could be added to salads.

Autumn brought rich pickings and whole families went on expeditions

to the woods and hedgerows to gather blackberries, rose hips, crab

apples, and mushrooms. Hazelnuts were another treat, and to take a

basket and ‘to go nutting’ was a seasonal ritual.

Gathering dandelions off Icknield Way

During and after the second war, long before the dangers were

realised, smoking was both a comforting and fashionable habit. In

the late 1940s some hopeful town residents, (although admitting

Tring was not exactly the Deep South) attempted to cultivate tobacco

plants in their back gardens. Much attention was lavished on

the crop, and buds and side shoots were nipped off to encourage leaf

growth, a task that was not especially pleasant as the leaves were

gummy, and stained the fingers brown. Nevertheless they

persevered, and one gardener from Longfield Road reported that the

leaves on his plants had reached a creditable 20 inches in length.

In a Beaconsfield Road garden another enthusiastic grower really

‘went to town’ and gave over a good section of his entire plot to

the cultivation of 50 tobacco plants. The leaves were duly

picked and hung up to dry and cure, and when ready, this local

tobacco supposedly boasted a ‘Havana flavour’ and was particularly

good for use in a pipe.

When viewing the shelves of present-day health food shops, it seems

that since Victorian times the wheel has turned full circle.

In those days, self-help using herbal remedies was often the only

resort for treating ailments. There is now a marked trend

towards the same thinking, and many prefer to use natural plant

extracts rather than prescribed drugs. In the mid-nineteenth

century in Akeman Street in Tring, William Sexton traded as a

herbalist, selling his products in a small shop. Many of his

remedies, albeit in very different packaging, may have been little

different from those to be found in Harmony today.

――――♦――――

CHAPTER 8

ORCHARDS

|

Beneath these fruit-tree boughs that shed

Their snow-white blossoms on my head,

With brightest sunshine round me spread

Of spring’s unclouded weather,

In this sequestered nook how sweet

To sit upon my orchard seat!

William Wordsworth (1770-1850) |

Tring has never been an area particularly noted for commercial fruit

growing, but reference to local old maps shows that the gardens of

every farm, sizeable house, and even some cottages supported an area

of orchard. In neighbouring villages fruit was cultivated on a

larger scale. At Aston Clinton and Pitstone apples and stone

fruits grew well. The speciality of the area was a natural

seedling plum known as the Aylesbury Prune, a variety

especially suited to soils of mixed clay and chalk. (In many

of these orchards another local delicacy, the Aylesbury Duck,

could be seen foraging under the trees.) Fruit from the

orchards at Pitstone was taken to Cheddington Railway Station, and

in the season it was by no means exceptional for ten to fifteen tons

to be despatched on any one day. A fruit farm at Buckland

Common also provided some jobs at picking time, and the village

supported a small cider factory which employed 13 workers.

However the little sour apples necessary for this product were not

grown on site, but arrived by rail at Tring Station, there to be

loaded on to a steam wagon and taken up the hill.

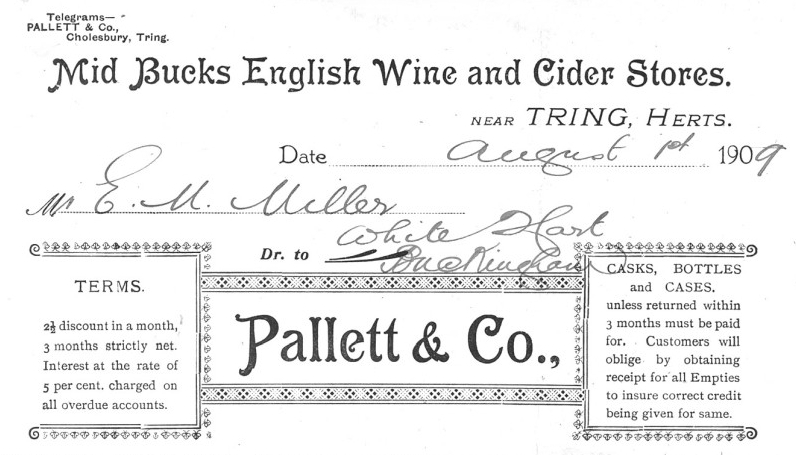

The cider factory at Buckland Common hidden

among the trees

Pallett & Co.’s billhead

Every large country estate had its own fruit orchard, as well as

kitchen gardens and glasshouses which contained fresh produce for

the owners, their guests, and servants. The orchard of the

Tring Park estate was situated in an area behind Silk Mill

House, on a piece of ground once part of the mill pond which

supplied the huge waterwheel that drove the machinery in the mill.

When water power was later supplemented by a steam engine, the lake

was partially filled in and fruit trees planted. Despite

guarded by a high brick wall, the orchard proved an irresistible

temptation to local lads who were always alert for ‘scrumping’

possibilities. (Some orchard owners sited their beehives among

the apple trees, not just for the purpose of pollinating, but to act

as a deterrent). By the middle of the twentieth century the

fruit trees at the Silk Mill were past their useful life.

Another area known as Dunsley Orchard was sited off the

London Road near the cricket ground. This was probably one of

the oldest fruit-growing areas in the town, as it can be seen

defined as an orchard on an estate map of 1719. In 1938, the

1.3 acre site was offered for sale during the dispersal of the

Tring Park properties. Nearby at The Bothy, the

home of the unmarried gardeners on the estate, a small orchard of

pyramid apple trees was planted in front of the house, and these

were never allowed to get beyond ten feet high.

W. J. Rodwell, who in Tring founded the soft-drinks company that

still bears his name, died in 1958, aged 90. He was a

versatile man who in his youth had undertaken every task on his

father’s farm. Later he studied land surveying, and learned

the process of straw plaiting (his father was a wholesaler of

straw). He was also widely known for his skill as a

horticulturist and fruit grower, and owned nearly 40 acres of

orchard land in Aston Clinton, where he cultivated apples and stone

fruits, including the Aylesbury Prune. Towards the end

of World War I when food supplies were scarce, William Rodwell was

able to help in an active way. In 1917 he supplied over 200

tons of fruit to the Government for drying and preserving, for which

the Ministry of Food requisitioned thousands of hampers.

Problems arose when these were reclaimed by their owners, and

William’s business acumen then came to the fore. He promptly

acquired 50,000 rectangular baskets which had been the standard

container for carrying howitzer shells. Stripped of their

internal fittings, these proved an ideal way to transport the fruit.

In a central depot at the Old Maltings in New Mill as many as 3,400

baskets were packed and despatched in one day. The centre

provided welcome employment for over one hundred mostly home

workers, women, and young people.

The year 1917 must have been excellent for its yield of apples.

It is recorded that in September a man from Tring carried a sack

full of fruit to the outlying villages hoping to sell the contents.

Alas, he could not find a single buyer and, rather than carry his

heavy load back, he dumped it in the road and said to the villagers

“help yourselves” which, of course, they did.

The story of the last working orchard in Tring is interesting.

After the horrors and hardships of World War I ‘Homes Fit for

Heroes’ was a common phrase heard for many years afterwards.

First uttered by David Lloyd George when campaigning during the

‘Khaki Election’ of 1918, like many Government promises it did not

entirely live up to expectations. An Act of 1919 gave local

authorities the task of helping to secure improvements in

working-class housing, as well as land on which to run

small-holdings. The owners of the Tring Park estate

offered Dunsley Farm to Herts. County Council for this latter

use, a gift which was accepted gratefully. The Council however

requested that the farm land fronting Station Road might be reserved

for better-class housing, and this eventually proved to be the case.

A Tring-born man, Walter Wilkins, became the tenant of the

farmhouse, and another ex-serviceman also benefitted from the new

scheme. Andrew Jeacock, from Warwickshire, was fortunate to be

granted an area of four acres off Cow Lane. A timber-framed

and elm-weatherboard bungalow and barn were constructed on the site,

and apple and plum trees were planted. Andrew combined this

work with his job as gardener to Miss Williams at Hawkwell in

Station Road, and as Green Ranger at Tring Bowls Club. Until

1959 he lived at Dunsley Bungalow, when his life ended

tragically at age 75. Although suffering from advanced

Parkinson’s Disease, Andrew continued to potter on his

small-holding. One bright August morning he busied himself in

the orchard, burning some dry grass. There, he stumbled over

an anthill and fell into the fire.

During the following years the bungalow had several different

occupants including one tenant who tapped the existing well to lay

on piped water to the orchard. Others used the property as the

base for a kennel business.

In 2003 came the threat of redevelopment when the Dunsley Action

Group was formed to fight proposed building plans. Martin

Hicks is an ecologist who for 18 years has lived at Dunsley

Bungalow, and holds the farm tenancy for two acres. He has

maintained much of the original orchard, which yields up to 3,500

lbs of apples and plums. Martin was instrumental in starting

Tring’s Own brand of apple juice, supplied in green bottles

which contain the juice from the organically-grown apples at

Dunsley, as well as from an orchard in Cheddington.

To members of Tring Environmental Forum the threat of demolition of

the bungalow and the construction of thirteen dwellings on the site

in Cow Lane was a call to action. Their efforts were not

helped by Herts County Council’s decision to commission an

independent ecological report contesting the Wildlife Status of the

area. In 2004 English Heritage Inspectors visited the site in

Cow Lane. In the report, one of the inspectors wrote “It is

a rare, well documented, almost unaltered example of a home fit for

heroes, and still within the managed holding.” They

decided that the whole site, including the 1920s bungalow, piggery,

and cart shed, had sufficient historical interest to warrant Grade

II listing.Misteltoe

|

|

|

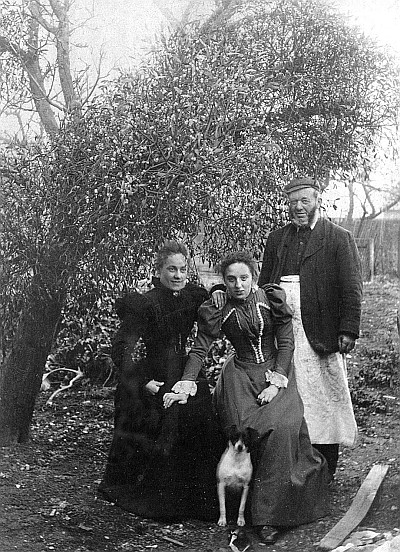

Mistletoe in the Cato family garden,

1898 |

Until the second world war, an orchard of mixed fruit trees extended

for a considerable distance close to the Icknield Way, in an area

known as Dundale. This was part of the pleasure gardens of the