――――♦――――

|

FOREWORD

This booklet is intended as a small tribute to the men and women of

Tring who served in the Great War. I am aware that its content

is patchy, nevertheless I hope it gives a flavour of the spirit and

thinking of that dreadful time. It is impossible to list every

name, for during the four years of conflict more than 500 are

recorded as playing some part in the armed forces, of whom more than

110 were killed in the line of duty or died later from the effects

of wounds or disease. The 107 names inscribed on Tring War

Memorial bear testimony to the War’s impact on the town, although

Tring’s losses are a fair average for the country overall.

To provide background, the first chapter comprises notes on the

progress of the War during its five years; this is followed by

extracts from letters sent to Tring from the various theatres and

the various services. Undoubtedly all serving men and women

wrote to their loved ones and friends, but after almost a century

few letters survive, while those still treasured among family

possessions are difficult to trace. In most instances it

cannot be said that the letters are particularly interesting; the

young men who wrote them, some only teenagers, were probably unused

to letter-writing and at any rate the censor did not allow soldiers

at the front to say where they were or what they were doing. A

sample of letters sent to Tring by the commanding officers of those

who died are also included, as is some relevant correspondence

written to or by civilians living in the town; some are mere

fragments while others cannot be traced to a particular individual.

The booklet could not have been compiled without the generosity of

Jill Fowler, Ann Reed, and Mike Bass who shared their researches

with me; and also the late John Bowman who amassed a great deal of

information on the Great War, especially regarding the men from

Tring who fell. I also acknowledge with thanks the help of

John Fountain, Susan Gascoine, the late Heather Pratt, the late Alan

Rance, the late Don Riddell, Frances Warr, the staff of Aylesbury

Local Studies Centre, Tring Local History Society who lent some

items from its collection, and Ian Petticrew who proof-read the

text.

W.M.A.

Tring, November 2014.

――――♦―――― |

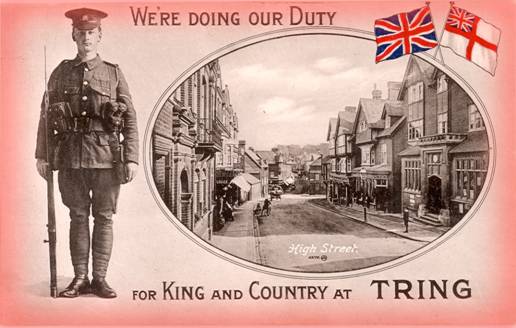

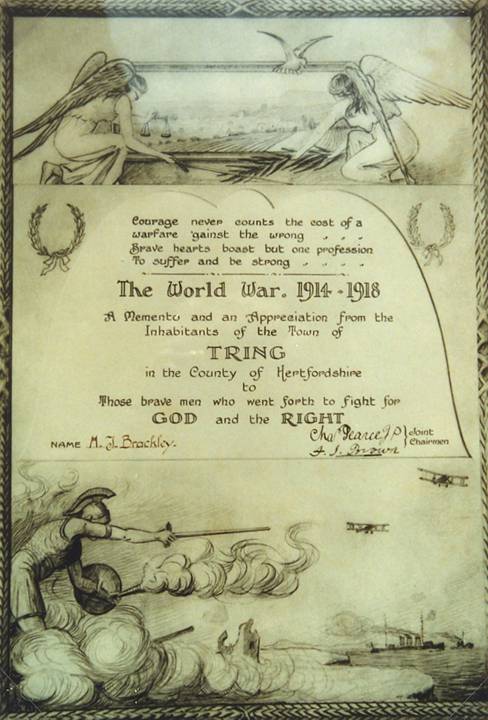

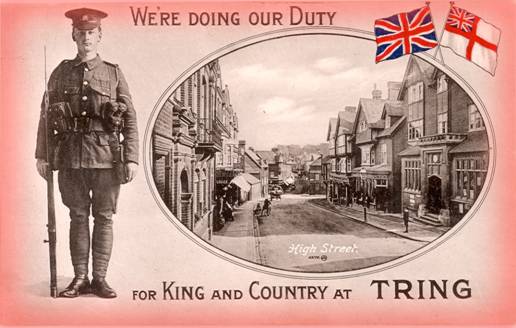

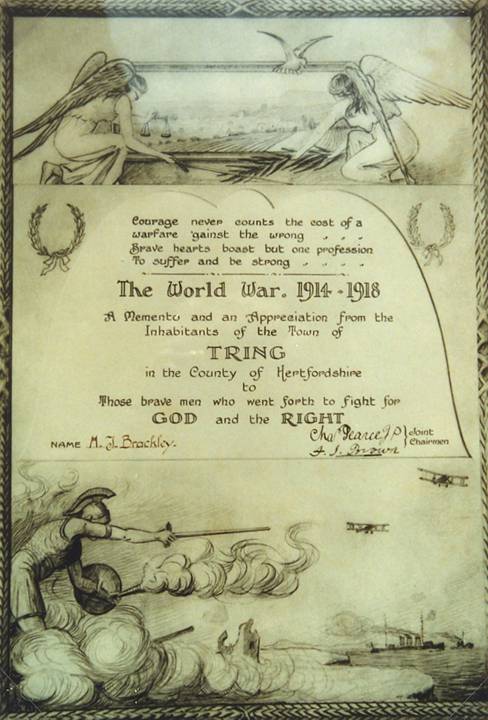

Issued by Tring Urban District Council to all

men of the town

who served in the armed forces.

――――♦――――

|

NOTES

ON

THE

PROGRESS

OF

THE

WAR:

1914-1919

1914: the political events leading up to the

assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on 28th

June are long and complex. Suffice it to say that although this

event

triggered the Great War, it did not result in Britain’s immediate

involvement. This came on 4th August when, following Germany’s

attack on France through Belgium, Britain, having chosen to honour

its obligation to defend Belgian neutrality

under the terms of the 1839 Treaty of London [1] —

declared war on Germany. By this time Germany was already at war with Russia and had allied itself

with Turkey.

|

|

Hunters owned by William

Mead of New Mill, requisitioned

for War Service on 4th August 1914. |

|

|

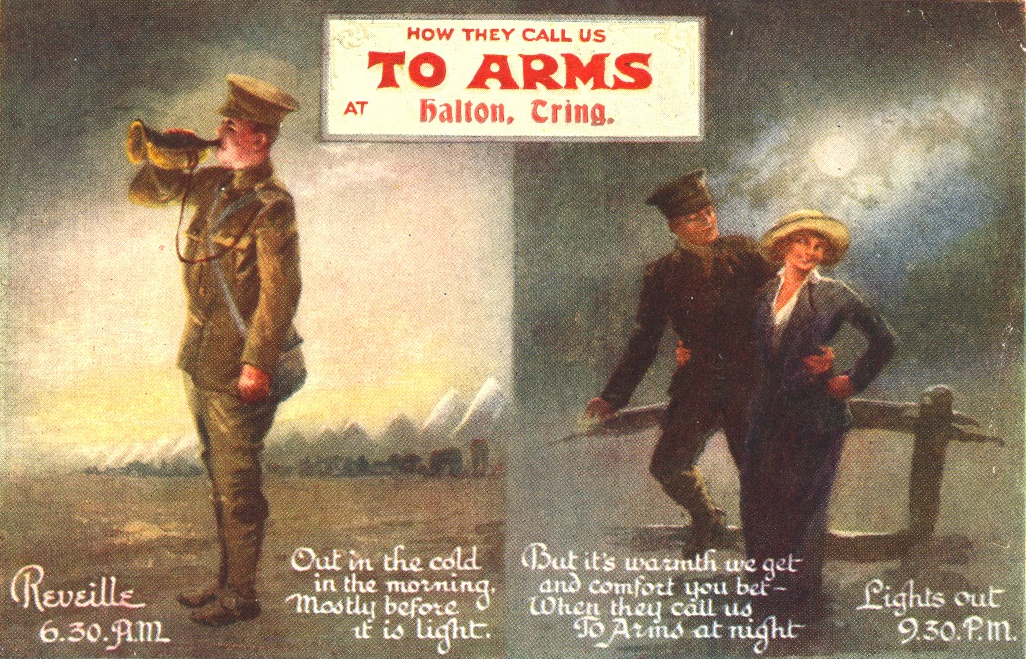

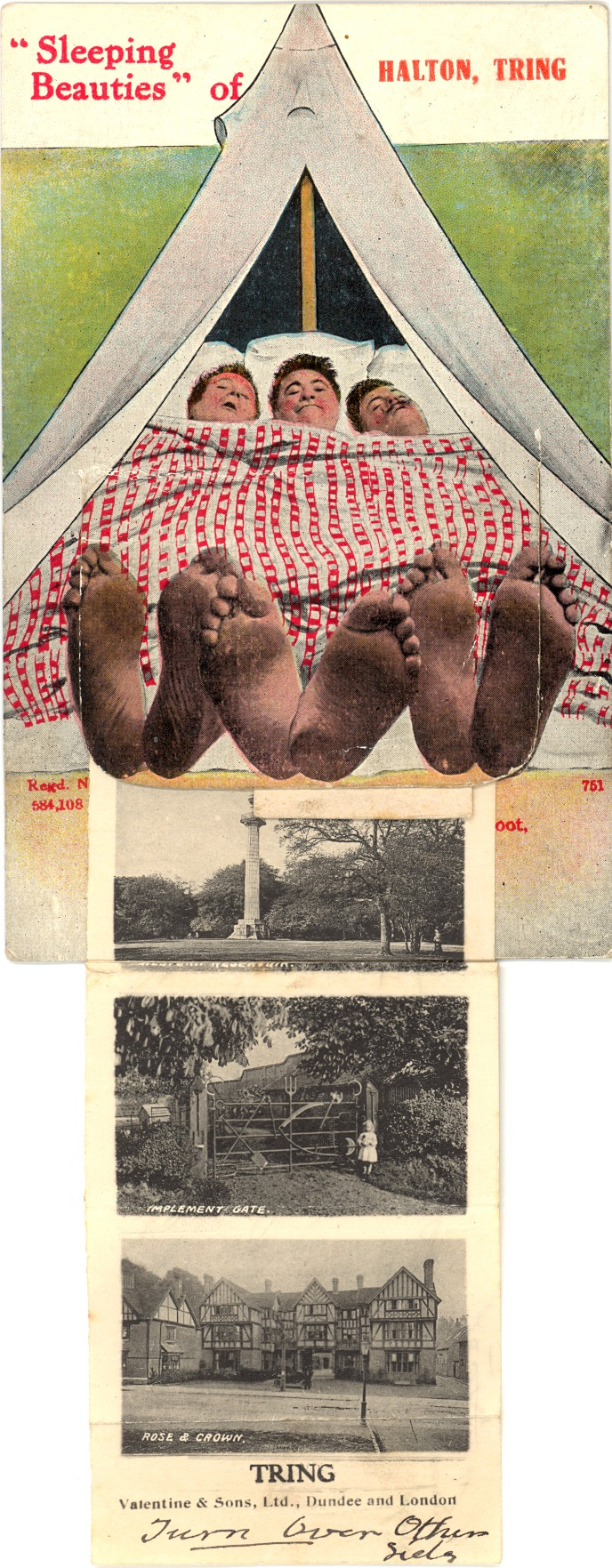

Postcard sent from Halton Camp. |

|

|

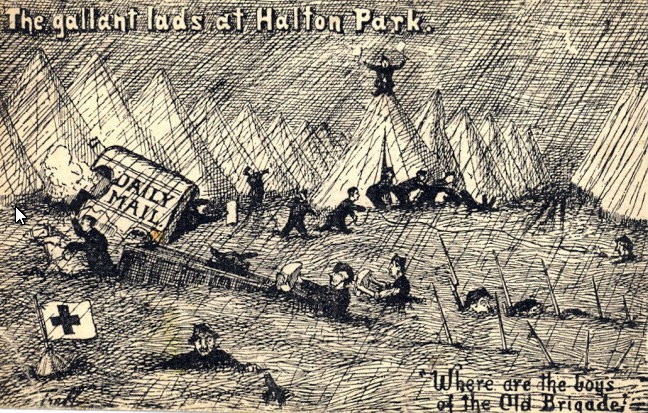

Postcard sent from Halton Camp, where the mud was seen

as a joke. |

Following the commencement of hostilities, reservists were soon

reporting to their naval and army establishments. Men of the

Territorial Army (primarily a home defence force) mustered at their

local drill halls and volunteers were requested to sign for service

where required. One of the first direct impacts on the town came

very shortly afterwards, on the day of the annual Agricultural Show

held in Tring Park, when horses of every size and breed were

numbered and catalogued ready for war. Two weeks after the

Declaration, Lord Rothschild made known to his employees on the

Tring Park estate that it was his wish that every unmarried man of a

suitable age should offer his services. About 20 men from the

gardens, timber yard, the Home Farm and other departments journeyed

to Aylesbury to join Lord Kitchener’s Army.

Field Marshal Lord Kitchener was a distinguished colonial

administrator and Army officer who won fame for his imperial

campaigns in the Sudan and South Africa. Following the outbreak of

war Herbert Asquith, the Prime Minister, appointed Kitchener

Secretary of State for War, and to him fell the task of organising

what became the largest volunteer army that Britain — and indeed the

World — had seen. Following his appointment, Kitchener set out to

supplement Britain’s small regular army by calling for 100,000

volunteers to strengthen the British Expeditionary Force, then

engaged in supporting the French and Belgians against the Kaiser’s

Army. [2] Having achieved this target in the

first few days of the proclamations, preparations were then made to

recruit a further 100,000 men. Local newspapers displayed

advertisements urging men aged between 19 and 38 to enlist quoting

Field Marshal French, then Commander-in-Chief – “It is an Honour to

belong to such an Army”.

On the 8th August 1914, The Defence of the Realm Act was passed

giving the Government wide-ranging powers during the period of

hostilities; for example, to requisition land and buildings needed

for the war effort, and to make regulations creating criminal

offences, such as discussing naval and military matters. And in an

effort to curtail excessive drinking, alcoholic beverages were

watered down and pub opening times were restricted to noon - 3pm,

and 6:30pm - 9:30pm.

In September, it was rumoured locally that a new army division was

to be formed at Halton Park, which had been offered to the Crown as

a further Rothschild contribution to the war effort. A tented camp

was hurriedly erected on what is now the airfield and men began

arriving from Northumberland, Durham and Yorkshire to form the 21st

Division. Due to a very wet autumn the camp soon became waterlogged

and the soldiers had to be moved out and billeted in any available

accommodation; 3,000 were housed in Tring, mostly with local

households. The billeting rates paid for soldiers were generous for

the time and no doubt supplemented the income of townspeople that

had been lost when so many of the male population had volunteered

for service . . . .

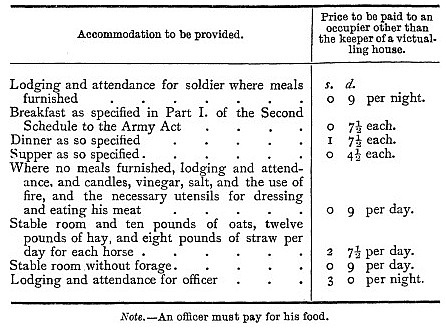

From: The Bucks Herald, 19th December 1914:

The continued presence of military in

the district is proving a boon to Tring, for it means the

circulation of money and the provision of employment. Tradesmen were

looking forward to a very slack time this winter, but the fixing of

the Headquarters of the 21st Division in the town and the billeting

of something like 3,000 soldiers has falsified this apprehension . .

. .

The school in Tring High Street was commandeered and the pupils

moved to various locations in the Town. Boys went to the

Church House and Market House, girls to the Lecture Hall in the High

Street Free Church and to the Western Hall (now the site of Stanley

Gardens), while infants were sent to the Sunday School room in the

Akeman Street Baptist Chapel. Further along the street the YMCA

building in Tabernacle Yard was opened as a writing and reading room

for soldiers, for whom bathing facilities were installed in the

Museum outbuildings. The Victoria Hall and Gravelly School (at

the top of Henry Street) were converted to medical and hospital

accommodation.

A bath parade in Akeman Street.

1915: the year began with the population being alerted

to a new form of attack — by aerial bombardment. This from The Bucks

Herald, 30th January:

PRECAUTION AGAINST

ZEPPELIN RAIDS. —

The police, acting on instructions from the County Constabulary

authorities, on Tuesday issued orders to the residents to lower all

lights at night and to dispose as far as possible with outside

illuminations. The street lamps were not lit, and the streets

presented quite a gloomy appearance. These precautions are being

taken in view of a possible raid by Zeppelins over the district, but

it is explained that such a raid is very unlikely to take place so

far inland. The special constables are out at night watching for any

signs of the approach of aircraft.

From: LIEUT. COLONEL LORD

CROFTON, 13th Northumberland Fusiliers,

to Mrs. Anderson of Westbury, Tring, after some of the Division had

left for France:

France, 9th January 1915.

Dear Mrs. Anderson,

I am writing on behalf of the NCOs and men of this Battalion to

thank you and the Tring friends of the Battalion for the cigarettes

and chocolates which were so very much appreciated by all, not only

for themselves, but for the kind thought which prompted the Tring

people to send them, and to think that the Battalion is not

forgotten, as the Tring people will certainly never be forgotten by

the Battalion for all their kindness to everybody. I am afraid

you will have thought that no acknowledgement was coming, but to

tell you the truth the things only arrived the day before yesterday.

With best wishes from the Battalion to everybody at Tring, and again

many thanks,

Yours truly,

CROFTON,

Lieut. Colonel commanding the 13th

Northd. Fusiliers.

On Saturday afternoon

Field Marshall Lord Kitchener, Secretary

of State for War, paid a brief visit to Tring for the purpose of

inspecting various contingents of the 21st Division who are training

in the neighbourhood. The greatest interest was manifested in

the War Secretary's visit . . . . Lord Kitchener inspected as many

Battalions as the time at his disposal permitted, and afterwards the

troops who has been inspected marched past the saluting point, where

the War Secretary stood with the Staff Officers. On leaving

the parade ground he was cheered loudly.

Bucks Herald, 27th March 1915. |

|

In Tring, various groups of ladies began knitting ‘comforts’ for the

troops, for it was quickly realised that scarves, gloves and

balaclava helmets were welcomed by those in the trenches.

From: MRS. C. M. WILLIAMS

to The Editor, The Bucks Herald:

Pendley Manor,

Tring, Herts.

3rd June 1915

Sir,

I have received a very urgent appeal from the Herts. Red Cross for

thin flannel or cotton nightshirts. They are in great need of

these articles at the present moment for hospitals in the county.

It is thought inadvisable to hold work parties in the summer, but

many may be willing to work at home for this object. I shall

be glad if any who are able to help will come to Pendley Manor at 8

p.m. on Wed. next to discuss the question.

Yours faithfully

(Mrs.) C. M. Williams

By the summer, the 21st Division had all left Halton Camp and were

in action around Loos and La Bassee. The Camp then became the

training ground for the East Anglia Regiment. In that year a number

of local men served in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign, [3]

as well as being part of the combined force of French and British

troops that had occupied Salonika and moved into Thessaly and

Macedonia in support of the retreating Serbian Army. The

casualty lists grew depressing long; almost every family in Tring

had a relative who had been killed or was missing, wounded or taken

prisoner, or had a friend or neighbour who had suffered in this way.

By now the Front had settled into a line of trenches that was to

remain little changed until 1918. This system varied from an

elaborate mishmash of deeply excavated trenches in the Arras/Somme

area, to built-up defences in the flat coal-mining areas around Vimy/Lens/Bully

and the Ypres Salient, where the water table was a mere two to three

feet beneath the surface. Large numbers of sandbags were

needed for these defences — it is estimated that each division of

15,000 men would need over one million bags a month — together with

wattle hurdles, chestnut paling and withy fascines. Voluntary

women’s groups were organised from North London collecting points to

make sandbags, the purchase of hessian in the Home Counties being

undertaken locally, and by September, 10,000 sandbags a day were

being despatched to the Front. The collecting point in Tring

was Hazeley in Station Road, the home of Miss Helen Brown.

1916: saw the Military Service Act come into

operation, which allowed the workforce to be directed as required to

support the war effort. Local tribunals were established to

grant exemption for men with large families, men and women who held

essential jobs, and men running family businesses and farms.

For those for whom the tribunals’ pronouncements were unacceptable,

there was recourse to an area appeal board.

Myryl Smith of Tring ploughing a field

off Icknield Way.

Goldfield Mill is left background.

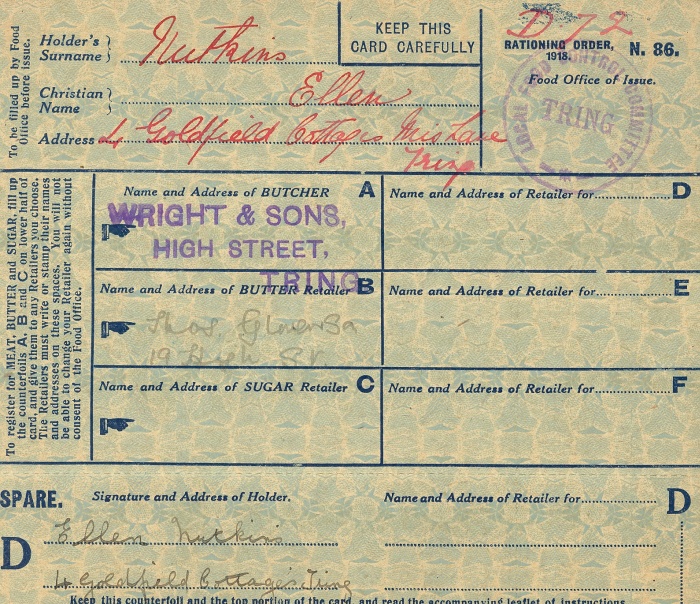

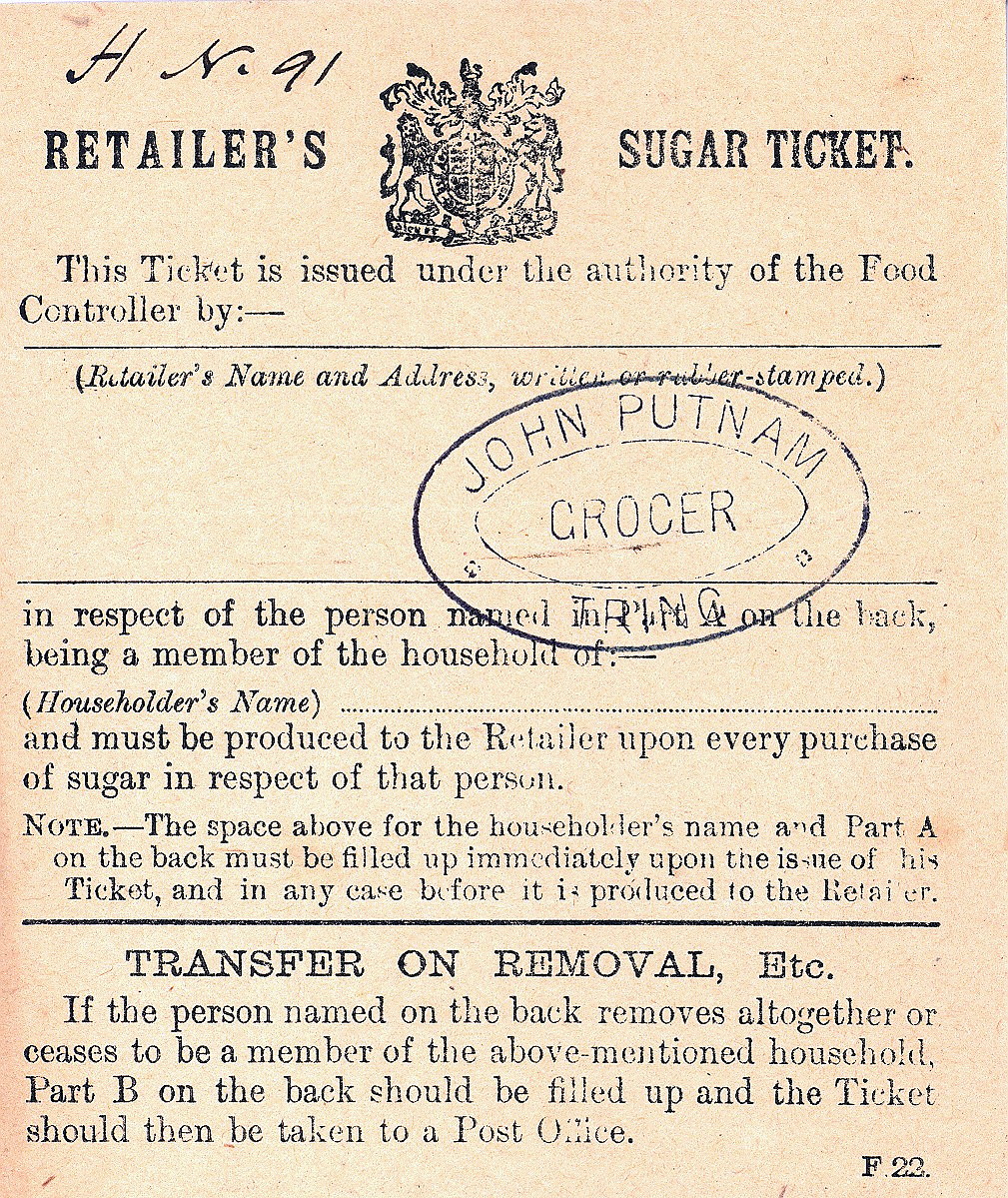

By now, the shortage of food caused by the German submarine campaign

was affecting the population. [4] Supplies

were not only limited, but prices were abnormally high.

Encouraged by the Government, steps were taken at local level to

increase the production of vegetables, with every available piece of

vacant land being placed under cultivation, including more areas

becoming allotment gardens. [5] The shortage

of labour on the land was circumvented by the formation of a women’s

volunteer force, ‘The Women’s Land Army’ (a recruiting rally held in

Tring in June 1918 attracted young women to a gathering outside

The Britannia public house, where some rousing addresses were

delivered by local worthies, followed a march through the town).

Women also played a vital part in Post Office work (post women were

seen in Tring for the first time) and women were also directed into

munitions factories. Felling of the Chiltern beech woods began

to provide pit props and duck boards for the trench systems in

France, and three forestry engineer units were put to work in the

area, one being Australian. The consumption of timber at the

Front was so great that a special port facility was built on the

River Seine at Rouen solely to address the need. The meadows

in the Vale of Aylesbury were in great demand for the provision of

fodder for horses, many thousands of which were used for

transportation and supply by the army, both at home and in France.

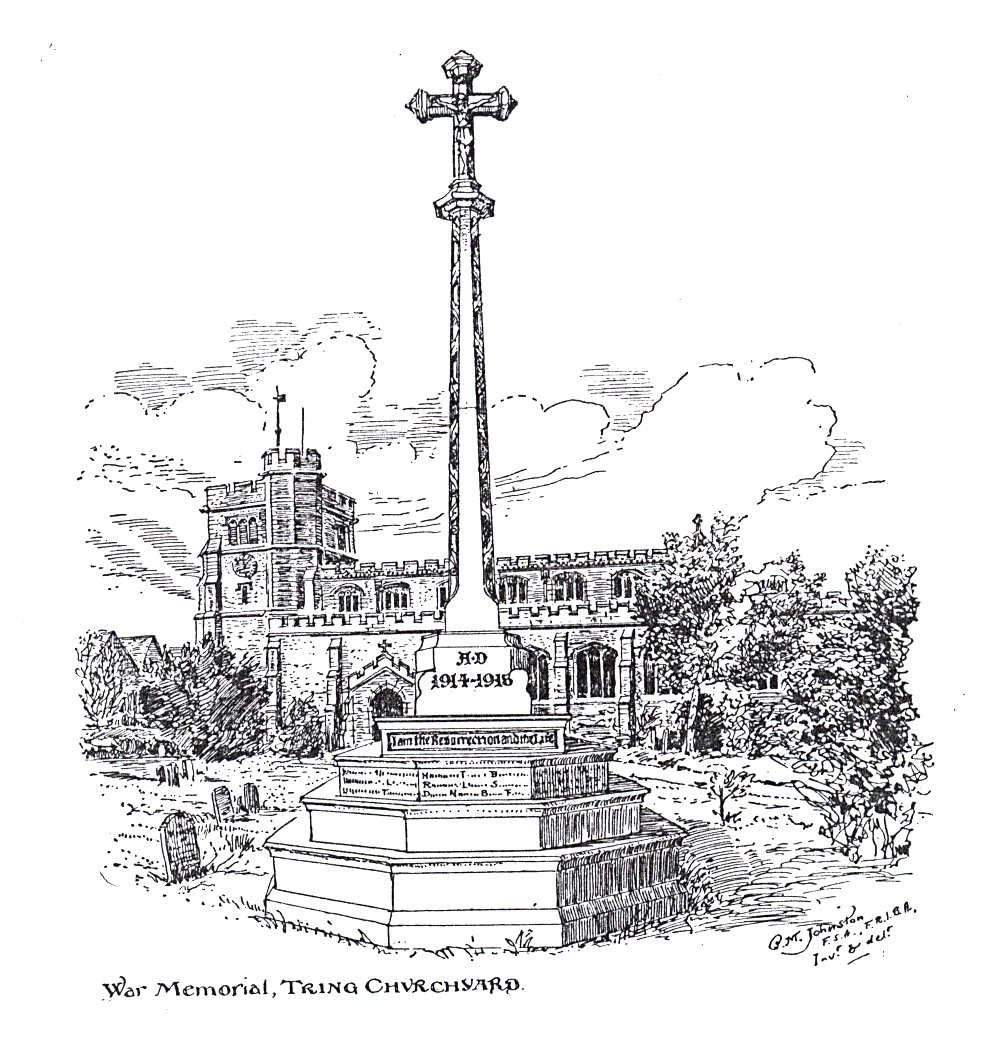

On 19th March, the Church Council discussed building a War Memorial

[Appendix] to commemorate the young men of the town who had given their lives.

It was suggested that the memorial should take the form of a

crucifix similar to the roadside shrines familiar to all soldiers

who had served on the Western Front. War savings groups were

formed under the auspices of the National Savings Committee, and

street marshals collected pennies for stamps which were affixed to

cards. When full (15s. 6d) they were exchanged for a

certificate worth a pound sterling in five years.

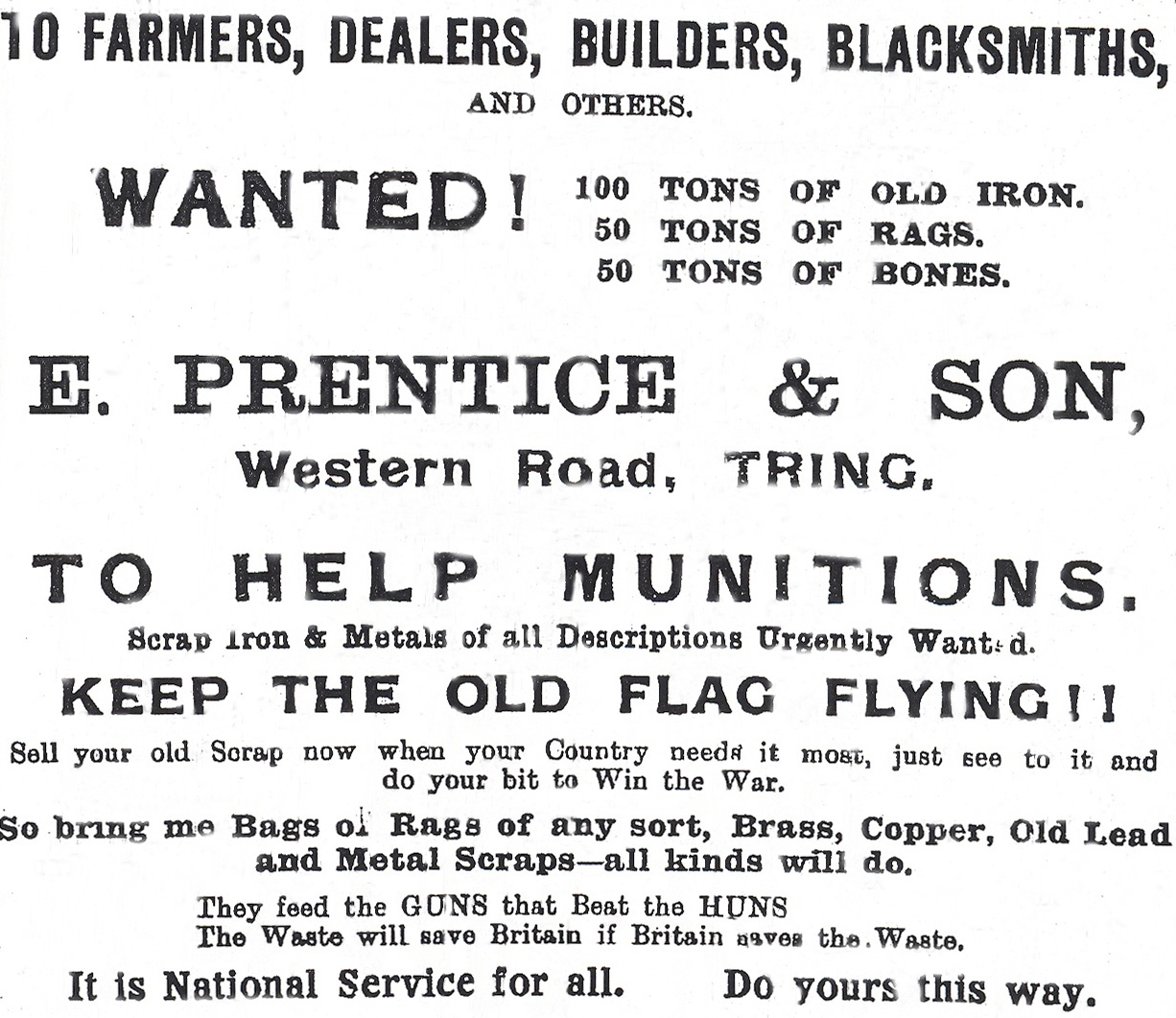

Bucks Herald advertisement, 1916.

The Royal Flying Corps moved into the north camp at Halton and a

flying field was established with an Australian Squadron. The

training organisation was concentrated in the new workshops being

built by German prisoners of war under the direction of the Royal

Engineers.

From the 31st May to 1st June, the Battle of Jutland was fought

between the Grand Fleet commanded by Sir John Jellicoe and the

German High Seas Fleet commanded by Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer.

It was the largest naval battle of the war and the only full-scale

clash of battleships, with both sides claiming victory.

Although the Royal Navy lost more ships and twice as many men as

their opponents, the High Seas Fleet was forced to retire, never

again to venture to sea in force. Germany now turned its

maritime war effort to unrestricted submarine warfare, with great

effect.

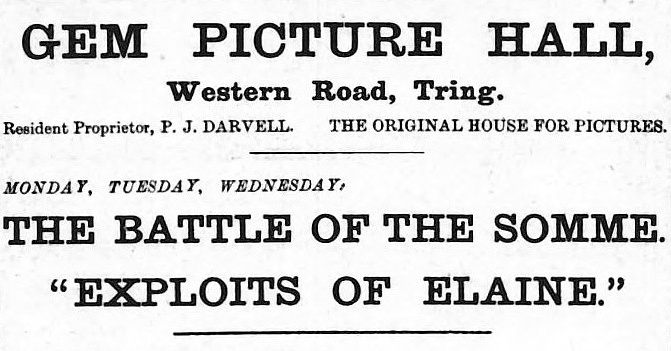

Bucks Herald advertisement, 1917.

On land, the Western Front extended some 400 miles from the Swiss

frontier to the Channel coast; stalemate had been reached.

Preparations were made for a major campaign on a 25-mile front in

the area north and south of Albert, its chief aim being to divert

German resources away from Verdun where the French Army was under

great pressure. The ensuing Somme Offensive (the ‘Big Push’)

raged from July to November; the outcome was inconclusive with both

sides suffering huge casualties. [6] During

this period yet more names were added to Tring’s Roll of Honour.

On 30th May, London was bombed for the first time, the Zeppelin raid

killing seven and injuring thirty-five — a portent of things to

come. On the 3rd September, a Zeppelin was reported over

Tring; this from The Bucks Herald:

|

“ZEP” SCARE. — Soon after

midnight on Saturday a warning to prepare for an air

raid came through. Specials and firemen were at

once called out, and at the military hospital

preparations were made for the reception of casualties.

How near the Zeppelins came to Tring is uncertain, but

the light from the one that was set on fire and which

fell at Cuffley was distinctly visible in the town

illuminating a wide area, and the noise made by the

engines was plainly heard. It was 4.40 on Sunday

morning before the danger was reported over, and the

tired specials and others were permitted to return to

their beds. |

1917: in April, a British offensive commenced in the

Arras area of the Western Front during which the German army was

pushed back resulting in the capture of the Vimy Ridge by the

Canadian Army Corps.

By May, the German submarine campaign was causing serious losses to

British merchant shipping and to our vital imported food supplies.

So critical was the position that the King issued a Royal

Proclamation exhorting the population to exercise the greatest

economy in the use of all kinds of grain, including that used to

feed animals. Householders were asked to reduce their

consumption of bread by at least a quarter and only to use flour for

making bread.

British freighter SS Maplewood being

sunk by German submarine U-35 on the

7th April 1917. In all the

U-35 sank 224 ships for a total of 539,741 gross register tons.

Women were already serving in various nursing services, such as the

Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) and Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army

Nursing Corps (commonly known as the QAs). To these units the

Navy and Army now added their own female services, the Women’s

Royal Naval Service (Wrens) and Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAACs)

to take over such duties as driving vehicles, catering and clerical

work, in order to release men to fill the increasing gaps in the

fighting forces.

On the 6th April — following the sinking of American ships in what

Germany classed as ‘war-zone waters’ — the U.S.A. declared war on

Germany and on the 26th June, 14,000 U.S. infantry troops landed in

France to begin combat training.

German Gotha heavy bomber.

The 25th May saw the first German aircraft (as opposed to Zeppelin)

raid. The target was London, but cloud cover caused the

‘Gotha’ bombers to divert to targets on the S.E. coast; this from

The Times:

Heavy casualties — 76 killed and 174

injured — many of them women and children, were caused by a German

air raid on a big scale on the South-east Coast on Friday evening.

Nearly all the casualties were in one town

[Folkestone], the name of which is not

given in the official report of the raid. The German official

report mentions Dover and Folkestone. On their return journey

across the Channel three of the German aeroplanes were brought down

by fighting squadrons of the Royal Navy Air Service from Dunkirk.

On the 13th June, a daylight attack on London killed 162 civilians,

the highest death toll from a single air raid on Britain during the

Great War.

1918: the Bolshevik Revolution resulted in Russia

ceasing hostilities with Germany in March, thus allowing thousands

of German and Austrian troops to be moved to the Western Front.

Later in the month the now strengthened German army under Ludendorff

launched a major offensive in the West. With American troops

still to join battle, the Germans advanced rapidly, crossing the

River Somme and pushing the French back towards the Marne, but the

German offensive gradually petered out and by July the tide had

begun to turn. A concerted Allied counter-offensive drove the

Germans back beyond their starting point. German military morale

began to crumble, exacerbated by the huge manpower and economic

might that the U.S.A. brought to the conflict.

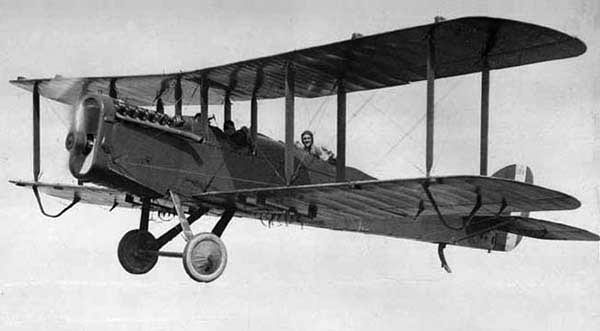

On 1st April, the Royal Air Force was formed from an amalgamation of

the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and the Royal Navy Air Service (RNAS).

As aircraft developed, the RFC had taken an increasingly offensive

stance in which enemy lines of communication were targeted; even

industrial complexes in the Ruhr and Saar areas came under aerial

attack. During the last five months of the War, British

aircraft dropped a total of 550 tons of bombs (including 390 tons

dropped by night) on German targets for the loss of 109 aircraft.

World War I. British bomber, the Airco

DH. 4.

By now the German nation was being worn down by lack of food

resulting from the British naval blockade, which together with the

appalling casualty lists was causing strikes and demonstrations

across the country, and there was growing fear of a Russian-style

revolution. With the country rapidly becoming ungovernable,

Germany sought an armistice, which was concluded on 11th November.

Vast crowds gathered in Trafalgar Square to celebrate the victory,

but when news of the Armistice reached Tring there was not the great

burst of jubilation that might have been expected. Over four

years of bereavement, hardship and privation had left behind a

mixture of emotions as well as uncertainty about the future, and

no-one was foolish enough to imagine that everything could revert to

how it had been before the conflict. A brief account of the

receipt of the news was reported in The Bucks Herald of 16th

November:

THE ARMISTICE

– Expectant knots of people were in the streets

[of

Tring] during Monday morning awaiting

news of the signing of the Armistice, but it was not until just

before eleven o’clock that the first definite news arrived in the

shape of a phone message from the YMCA Headquarters. As if by

magic, flags appeared from windows of adjacent residences, and

shortly after the incessant blowing of whistles at Aylesbury was

heard, which confirmed the receipt of the glad news. The

official Press Association telegram was posted outside the branch

office of The Bucks Herald and the streets were quickly

thronged with flag-bearing youngsters, while older people were

congratulating each other on the conclusion of the long period of

trial through which the country had been passing. There was

very little excitement in the town, the news being received with

grateful calmness, due no doubt to the grievous losses experienced

by so many families. Streamers of flags were hung across the

street, and by afternoon the town presented a festive appearance,

the bells ringing out a merry peal soon after noon, and again in the

evening, after a thanksgiving service in the Parish Church. A

service of thanksgiving also took place at the Akeman Street Church.

1919: although the Armistice marked the end of

fighting, six months of negotiations between Germany and the Allied

Powers were to follow before a peace treaty was concluded. The

Treaty of Versailles was signed on 28th June 1919, exactly five

years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the event

that led to the catastrophe. The terms imposed on Germany

included substantial territorial concessions and the payment of

heavy reparations, and the Treaty was only ratified by the German

government with great reluctance. Whether the Treaty terms

were excessively harsh remains a subject of debate among historians,

but what is clear is that the resentment they caused in Germany led

to the eventual rise of the Nazi Party; as Field Marshall Foch put

it, “This [the Treaty] is not peace. It is an Armistice

for twenty years.”

The “big three” - Prime Minister David

Lloyd George of the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Georges

Clemenceau of France, and President Woodrow Wilson of the United

States attend the Versailles Peace Conference, 1919.

At home, the joyous mood in the country following the end of

hostilities was short-lived. Many soon realised that post-war

Britain did not seem like a country that had just experienced a

great military triumph, for various political, economic and social

problems ensured that the our nation’s return to peacetime

conditions was not to be a quick and easy transition. Although

demobilisation was relatively unproblematic, the end of the war

witnessed many workers becoming involved in strikes, and by 1921

unemployment reached its highest point (11.3%) since records began.

Staple wartime industries such as coal, ship-building and steel

contracted, and working women were forced to relinquish their jobs

to returning soldiers. During the conflict, Britain incurred

debts equivalent to 136% of our gross national product — our major

creditor, the U.S.A., was soon to emerge as the world’s leading

economic and military power. [7]

|

Tramp of feet and lilt of song

Ringing all the road along.

All the music of their

going,

Ringing, swinging, glad

song-throwing,

Earth will echo still, when

foot

Lies numb and voice mute.

On, marching men, on

To the gates of death with

song.

Sow your gladness for earth’s

reaping,

So you may be glad, though

sleeping.

Strew your gladness on

earth’s bed,

So be merry, so be dead.

Captain

Charles

Sorley [8] |

――――♦――――

LETTERS

FROM

THE

WESTERN

FRONT

|

Kill if you must, but never

hate,

Man is but grass and hate is blight;

The sun will scorch you soon or late,

Die wholesome then, since you must fight.

Captain Robert Graves |

From: BOMBADIER PERCY SEABROOK,

35th Brigade Royal Field Artillery, one of four sons of Edwin

Seabrook, of Albert Street, serving in the Army or Navy:

8th December 1914

Dear Mother and Father,

Just a few more lines in answer to your letter. I am glad to

know you are still well. I am well at the time of writing,

only wet through to the skin. It makes the third wet shirt in

24 hours, but we take no notice of that now. We have got used

to it by this time. We have had some very bad weather here

lately, but I hope it is finished for a bit now. We are still

in the same place – been here for nearly three weeks – and I cannot

say when we are moving again. But I expect there will be a

sudden move shortly, as soon as everything is ready. It

doesn’t do to strike until everything is ready. You say in

your letter – shall I be home for Christmas? I may be home 12

months come Christmas, but I would like to be home for this all the

same.

Well, I am in the best of spirits up to the present, and although I

don’t much care about again going through the same as we have been

through, if we have to, we can do it again with a good heart.

You can read of my Battery in the Daily Mail of Nov. 26th. The

heading is “Sticking to the Guns” and “The Heroic Defence of

-------” by a Single Battery commanded by Major Christie.”

I remain, your affectionate son,

Percy Seabrook

――――♦――――

From: PRIVATE W. G. MUSTILL,

of Cow Roast Lock, Tring, serving with the 1st Battalion,

Northumberland Fusiliers. Taken prisoner of war, Private

Mustill had been severely wounded, losing an eye and having one arm

badly damaged. Repatriated to Alexandra Hospital, London, he

wrote home:

I am back again in dear old England.

I arrived at Folkestone at 6 p.m. Wednesday, and came up to London

to hospital. We stopped at different places on the way home,

picking up men by ones and twos. We were very glad when we

were out of Germany and amongst friends in Holland. It was

like waking up after a dream, even to me, and I had been luckier

than most of the others, as I had left a good hospital and the

others came from prison camps. We had a very rough passage

home. I shall be a little time yet as I am getting my arm put

straight. There are about 150 of us sent home in exchange for

Germans; we were at the same station as the Germans in Holland.

They were all in new kits, but our chaps were in any old things.

We have had the King and Queen to see us. We are very

fortunate to be home, although some of us are maimed for life.

I shall want an artificial eye before leaving the hospital.

There are half a dozen young fellows home who have lost both eyes,

so I am fortunate . . . .

――――♦――――

Private Frank Edgar Marcham was 22 years of age when he was killed.

He was the son of Fred Marcham of ‘Oakleigh’ Western Road and had

been employed by the local coach-builders, Messrs Wright and Wright.

He and others were chopping wood in a stable to take back to the

trenches when a shell, probably intended for the Battalion

Headquarters, exploded just inside the doorway. Marcham and

three of his companions were killed instantly and Fred Rodwell, son

of Mr W. J. Rodwell of Tring Brewery, lost an eye and sustained

other injuries. Frank is buried in the Guards Cemetery, Windy

Corner, Cuinchy, France.

1st Herts. Regiment, British

Expeditionary Force

2nd April, 1915.

Dear Mr. Marcham.

You will I am afraid have heard by now of the death of your son.

May I take this opportunity of conveying to you the deep sympathy of

the officers and men of his Company in your great loss. He was

hit by a shell at about 2.30 p.m. on the 29th March, and died at

once. I think he did not suffer at all, as his death was

practically instantaneous with his being hit by the shell. He

was buried by a clergyman in a grave that was properly made, and can

easily be identified after the war is over. At all times he

was cheerful, and his loss will be much felt by the Company. I

can only hope that in time you may draw some consolation from the

fact that he died as an Englishman would wish to, serving his King

and country.

Yours sincerely,

A. M. F. SMEATHMAN, Captain. |

The Guards Cemetery, Windy Corner, Cuinchy,

France.

|

――――♦――――

A letter published in The Bucks Herald on 4th December 1915,

turned out, with hindsight, to be a particularly sad document.

It related to CORPORAL WILLIAM

SPINKS, D.C.M., 1st Battalion,

Hertfordshire Regiment, son of Harry and Charlotte Spinks of

Bunstrux Cottages, Tring. It read:

Your Commanding Officer and Brigade

Commander have informed me that you have distinguished yourself by

conspicuous bravery in the field on 27th September. I have read

their reports and, although promotion and decorations cannot be

given in every case, I should like you to know that your gallant

action is recognised and how greatly it is appreciated.

W. J. Horne

Major-General, 2nd Division

In November 1916, less than a year after being awarded of the D.C.M.,

[9] the following account appeared in the Tring

Parish Magazine:

Sergeant William Spinks, D.C.M.,

Hertfordshire Regiment, was a soldier of the best type. Long

before the war broke out, he heard the call of his country and

joined the Herts Territorials; and, before that, had done his drills

in the Church Lads’ Brigade. Early in the war he was sent to

France, and took his place with that ‘Contemptible Little Army’

which wrought such wonders, and endured such hardships, and to which

we can never be too grateful. So excellent was his service

that he made, in time, a sergeant, and for a very plucky bit of work

on 27 September 1915, he received the D.C.M. . . . .

William Spinks died, aged 25 years, killed by a German trench mortar

bomb; he was buried in a small military cemetery at Auchonvilliers,

France. The name of William’s brother, LANCE

CORPORAL CHARLES

EDWARD SPINKS, is also

engraved on the Tring War Memorial. Charles enlisted in the

Hertfordshire Regiment in 1915, later being transferred to the 7th

Bedfordshire Regiment. Aged only 22, he was killed by a

sniper, his death being all the more tragic for his two sisters and

younger brother, for both his parents died within 18 months of

William. Writing to The Bucks Herald after his death,

one of his friends says:

He was hit by a bullet on the night of

11th January [1918] and

died almost immediately. I took it to heart as much as if he

had been my own brother, as we have been together practically for

the last 18 months, side by side in most of the big battles.

It was hard lines for him, as he was not wanted for the trenches

until the last five minutes. He was buried in a cemetery

[Artillery Wood Cemetery, Boesinge, Belgium]

in as good conditions as can be expected.

――――♦――――

Published in The Bucks Herald on 11th December 1915 – from

someone who described himself as ‘A Tring Tommy’ on the Western

Front. PRIVATE GILBERT

SLADE, Army Service Corps, was a

baker’s assistant in civilian life and the son of Mr. A. W. Slade of

Longfield Road, Tring:

Dear Sir,

To give you news is out of the question, for two reasons.

First that the Censor is a particular chap, and second that we get

here very little news. Winter is fast settling upon us and

well we know it. The comforts of the bell tent are very

limited, and we house-dwellers of England care none too much for the

canvas mode of living. But we smile through it all, and look

to a time when we shall be able to return to Merrie England, and

settle down again the better Englishmen for being able to take our

part in the war for freedom, and for having realised our duty and

responded to it at the most critical period of the nation’s history.

We get along very well with the Belgians and the French; but of

course we are not expert linguists yet, and never shall be.

Suffice it to say we can make our needs understood and that means

much.

Yours sincerely,

Gilbert Slade,

‘One of the Tring-ites’

――――♦――――

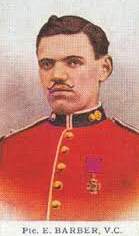

The story of Edward Barber, the town’s only holder of the Victoria

Cross, has been told many times. An exceptionally daring young

man, he won his award for most conspicuous bravery at the Battle of

Neuve Chapelle on 12th March 1915, when “he ran speedily in front

of the Grenade Company to which he belonged and threw bombs at the

enemy, with such effect that a very large number of them at once

surrendered. When the Grenade Party reached Private Barber, they

found him quite alone and unsupported, with the enemy surrendering

all around him.” Edward was later killed by a German

sniper without learning of the honour that had been bestowed upon

him. Because his body was not recovered, his name is recorded

on the Le Touret Memorial, France. Private Barber’s Victoria

Cross is displayed at The Guards Regimental Headquarters at

Wellington Barracks, London.

From: HIS MAJESTY KING

GEORGE V. to the parents of PRIVATE

EDWARD BARBER, V.C., 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards.

To: Mrs Sarah Ann Barber, Miswell Lane,

Tring.

Buckingham Palace,

9th March 1915.

It is a matter of sincere regret to me that the death of Private

Edward Barber deprived me of the pride of personally conferring upon

him the Victoria Cross, the greatest of all rewards for valour and

devotion to duty.

George R.I.

Mr. and Mrs. William Barber experienced more grief when their

youngest son, PRIVATE ERNEST

BARBER, 1st Battalion Hertfordshire Regiment,

was reported missing after an engagement on 31st July 1917. He

had been taken prisoner and did eventually return home, but died

from his wounds in September 1920.

――――♦――――

An account relating to LANCE CORPORAL

FRANK KITCHING,

Northumberland Fusiliers, was published in The Bucks Herald,

on 1st July, 1916:

News has been received here that Lance

Corp. Frank Kitching has had the Distinguished Conduct Medal

conferred upon by the King. Lance Corp. Kitching married Miss

Poulton of Western Road while the 21st Division was billeted in

Tring. Referring to the award, the Regimental Magazine says

“…….. Lance Corp. Kitching of the Lewis Gun Detachment has been

awarded the DCM. During a heavy bombardment he was twice blown

up but each time returned to his gun. He must have

napooed [sic] a lot of

the enemy with his accurate fire.

Mrs Kitching received the following letter:

British Expeditionary Force,

25 May 1916.

Dear Mrs. Kitching,

I am writing to you inform you that your husband has been awarded

the D.C.M. medal for his gallant conduct on Sunday 30 April.

Please convey to him the congratulations of all officers and men of

this Battalion and especially of the Machine Gun Section. We

are proud of him. I was sorry he was wounded but pleased to

know his wounds are not serious; and we trust he will soon recover

and be able to re-join us out here. . . . .

Yours sincerely,

John McKinnon

――――♦――――

|

|

Memorial plaques to William

and Charles Spinks.

Issued by the Government to relatives of all who died in

the war, they were nicknamed

Dead Man’s Penny, Death Penny, Death Plaque or Widow’s

Penny. |

|

|

|

|

Above, Private Edward

Barber, V.C.,

1st Battalion Grenadier Guards.

Left, Private Sidney Fountain, 1st Battalion,

Cambridgeshire Regiment. |

|

|

|

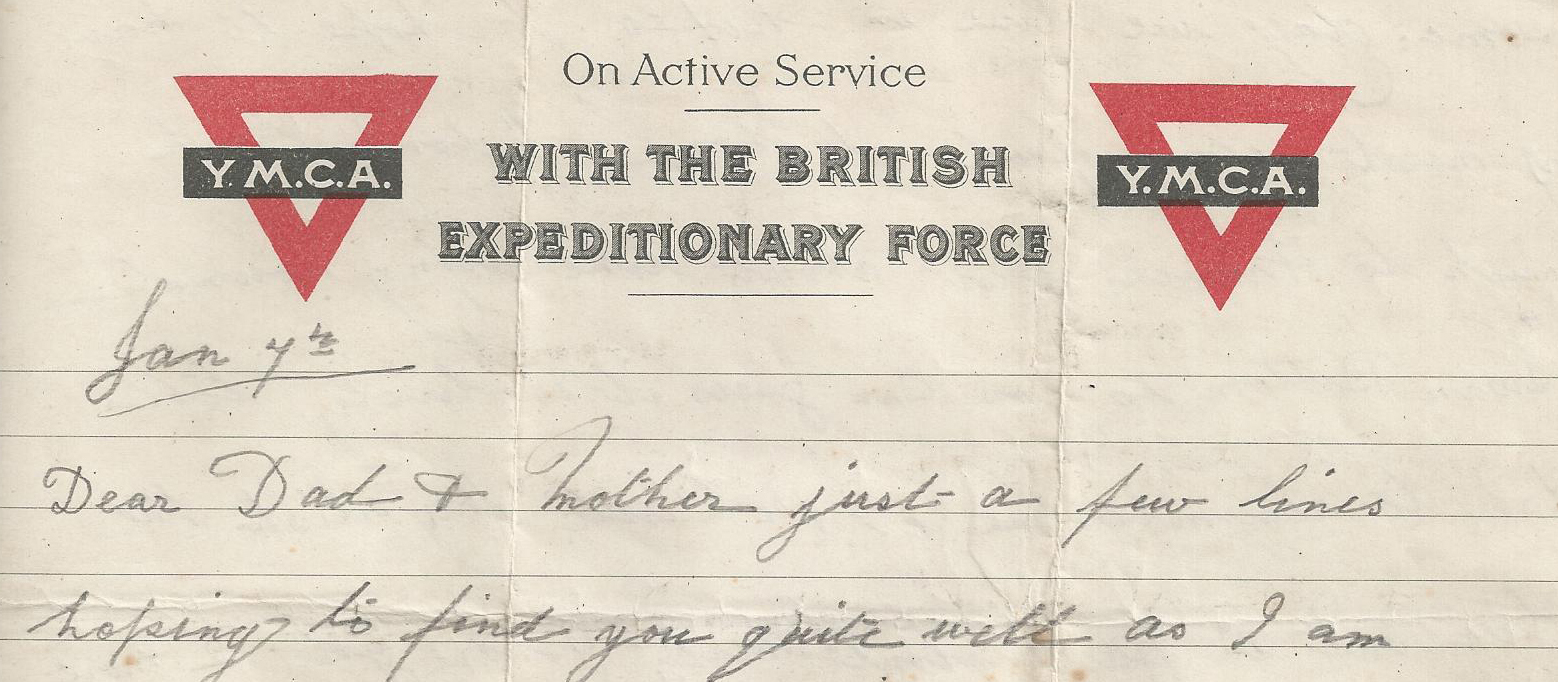

The beginning of

Sydney

Fountain’s letter to his parents. |

|

|

|

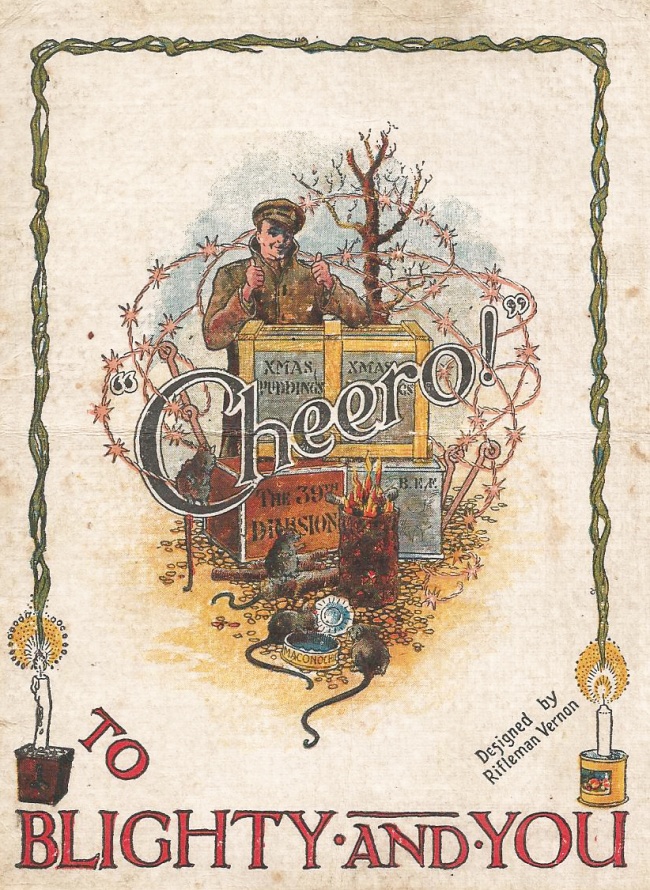

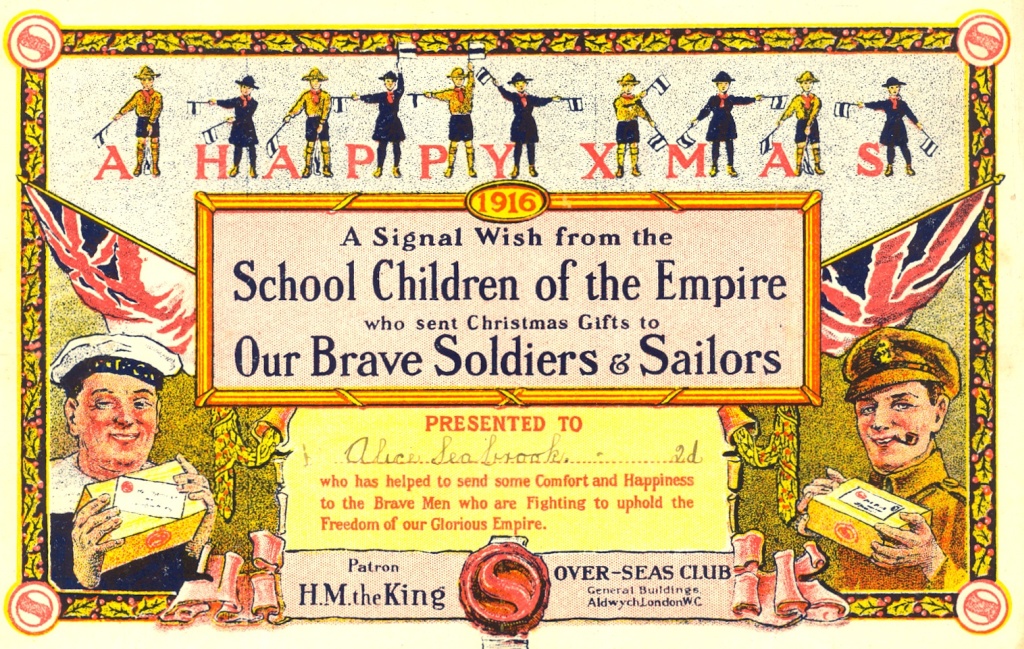

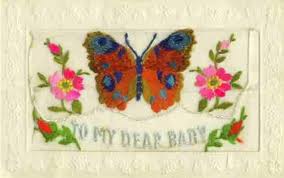

An example of a typical

Christmas card sent from the Front . . . .

from Sidney Fountain to his parents in 1917. |

|

|

|

Tommies keeping in touch

with their loved ones. |

Several Tring men fell during the course of the protracted battle on

the Somme in 1916, among them 2nd LIEUTENANT ANDREW

CRANSTOUN BROWN,

8th Battalion South Staffordshire Regiment. Killed in action

during what was termed ‘The Big Push’, he was the 21-year old son of

the late Dr. James Brown of Aylesbury Road, Tring, who had died

early in the war. He is buried in the Danzig Alley British

Cemetery, Mametz, France, and is also commemorated on his father’s

memorial stone in Tring Cemetery. Shortly after his death,

Andrew’s mother received this letter from one his men:

I always thought when I got back to

England that I should like to tell you the brave way in which your

son died and how he led us. That day he was quite cool all the

time and one of our boys, after we had advanced over three lines of

trenches and were lying down, said to Lt. Brown ‘That trench is full

of them, Sir’. He got up on his knees, put his glasses to his

face to observe them, when he had a bullet through the head.

We were all dumbfounded.

A great mark of respect was offered to Lt. Brown when about three

days later, his Platoon had fallen back a bit and his body was

brought down and lay quite close to us on a stretcher. A

German battalion which had surrendered was coming down and we could

see them being led on, when suddenly, as they got to where we were,

the German commander pulled up the lot and turned to salute, which

we thought was funny. But again we looked, but it was the

salute to the dead body of our Lt. Brown. This thing impressed

me very much. I always said if I got back I would let his

people know.

You will, perhaps, pardon me as a private soldier. I admired

and respected your son.

――――♦――――

From: (dating probably 1918): PRIVATE SIDNEY

THOMAS FOUNTAIN,

1st Battalion Cambridgeshire Regiment:

Dear Dad and Mother,

. . . . myself. I received the parcel alright and was very

pleased with it. Pleased you enjoyed yourself at Xmas. I

spent my Xmas night and Boxing Day in the trenches, but we are right

back now. We had our New Year’s supper last night, plenty to

eat and drink and with your parcel I had quite a good time.

Pleased to hear Jack is coming home, hope he is quite well, I should

like to be at home to see him but I hope we shall some day. We

live in hopes. I hope to have my next Xmas at home.

I don’t think much to France, just about like being round Swan

Bottom. So you can guess it is lively. Tell Dad to

remember me at The Castle. They dish the beer out in pails

about here. I have got two more parcels to come Sarah

[his wife] tells me, so I shall

be alright. They are a long time coming sometimes. This

is about all this time, wishing you a happy New Year, hoping to see

you all again someday, from Sid.

Aged 29, Sidney Fountain lived with his parents, wife and two

children in Charles Street, Tring, where he worked for the Co-op as

a car-man. He joined the Army in 1916 in the Northants

Regiment, and transferred later to the Cambridgeshire Regiment,

being posted to the Front in June 1917. Sidney was not granted

the last wish in his letter above — to see his family again — for he

was killed in action by shellfire on the Somme towards the end of

the war (28th August 1918). He is buried in Perronne Road

Cemetery, Maricourt near Albert, France.

Published in Tring Parish Magazine — from an OFFICER

IN THE ROYAL ENGINEERS

(Signals) 3 April 1918 —

At last! After twelve of the most

strenuous and exciting days I have ever known, remnants of us are

safely out for a bit in a green field, able to sleep. Ever

since the fight began we have been at it all day and all night –

fighting, marching, retreating, counter-attacking etc. etc.

Out of the 12 nights of the fight I was four nights without a wink

of sleep, and have certainly not averaged three hours of sleep out

of 24 for the rest of the 12 days. Never had boots off except

once to wash my feet, shaved about three times, washed hands and

face about every other day; and with it all I have been wonderfully

and marvellously fit – huge appetite and perfect digestion; walked

and ridden countless miles without fatigue or soreness and come

right through it without a scratch. A wonderful experience!

Yesterday we came out of the fight battered and dirty but still

cheerful. I ended up by an all-night march of 24 miles, so

tired and sleepy that I could not remain on my horse, but had to

walk to keep awake, after which I slept all morning, most of the

afternoon, and all night and still could do with more.

The Signal Company has been pretty fortunate on the whole in the way

of casualties, one officer killed and some valuable NCOs but very

few men and only three horses.

When we are refitted we will, I suppose, enter the fight again with

renewed vigour. The end is not yet, and though the Hun has won

the first act, it does not follow he has won the rubber. Our

post has been held up from the start but I have received it

altogether yesterday.

|

Waste of blood and waste of tears,

Waste of youth’s most precious years.

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy |

|

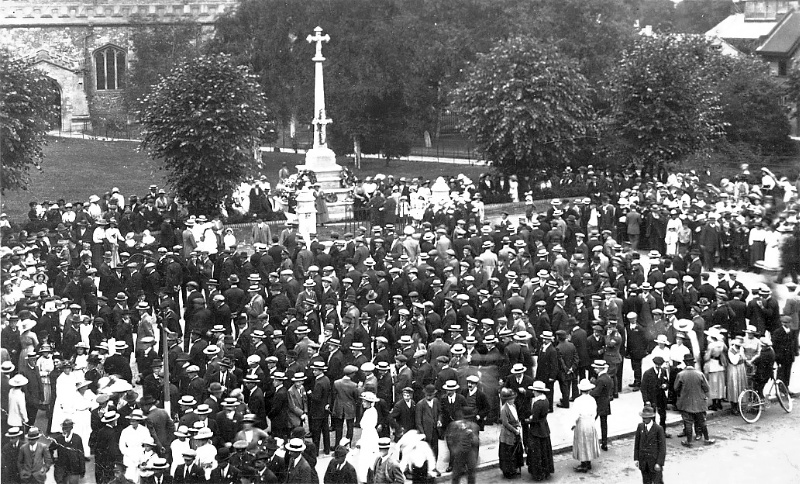

Tring War Memorial

[Appendix].

Plaque on the gatepost of Tring Memorial

Gardens.

――――♦――――

|

LETTERS

FROM

OTHER

THEATRES

OF

WAR

In August 1915, SERGEANT FRANK

SHEERMAN, Royal Bucks Hussars, was

wounded in action in the Gallipoli campaign and invalided home

shortly afterwards. His parents received this letter from his

great friend Frank Nash of Aylesbury, also badly wounded and in

hospital in Cheshire:

We had orders to march across the Salt

Lake (a death trap) on 21st August. When we were about a

quarter of a mile across the Turks spotted us, and poured shot and

shrapnel at us for all they were worth. It was like a

thunder-storm. Our men kept falling around us, but we marched

on all gay as if on a route march. Believe me, it was the best

march I have had, for it made one feel proud to be with such a

gallant lot of boys.

When we were about a mile and a half across, Frank got hit in his

left hand. I am almost sure it was only his fingers that were

hit, because Frank was in the front of the troop and I was just

behind him, and some of the shrapnel hit my boot at the same time.

Well, we got under Chocolate Hill, and I asked Frank if he was hurt

anywhere beside his finger, and he said he did not know; but he felt

very bad. He looked very white, and walked lame. I

thought at the time he might have a slight rupture, as he laid down

under Chocolate Hill as soon as we stopped, and it was a job to

avoid laying on one’s water-bottle with all our Infantry equipment

on. We left Frank behind with the doctor, as we had to get

into touch with “Mr Turk” and do some dirty work with our bayonets .

. . .

British troops dig in on Chocolate Hill,

Sulva Bay. This attempt in August 1915 to break the

deadlock

of the Battle of Gallipoli was

unsuccessful, and Sulva Bay was evacuated a few months later.

About the time the above letter was received, Frank Sheerman’s

parents also heard directly from their son then lying in hospital in

Plymouth:

You must think you have got one of the

luckiest sons on God’s earth, firstly for his being spared in that

terrible attack on the 21st August (a day that will never be

forgotten); and secondly for his being fortunate enough to be

brought to England, while so many thousands of others only go to

Alexandria, Cairo or Port Said. Well, my wound is not very

serious. I am hit in the lower part of the abdomen, and I have

got to undergo an operation here; but I am very confident of coming

through all right, and being none the worse afterwards. We

lost heavily, I believe, but have not seen the regimental

casualties; so if you can give me any particulars which may have

been published, I should like to see them.

After a rough voyage we arrived in Plymouth Harbour on Friday, and

were moved here. All now that we have been through seems like

a bad dream; a hot bath and clean shirt (minus the wee midges), to

say nothing of a spring mattress, being fair compensation for a lot

of hardships. Chocolate Hill, the hill we are trying to

capture is 907 ft. high, and rises straight from the beach, so you

can tell what it is like trying to climb up and do bayonet charges,

carrying 250 rounds of ammunition. . . . . If it had not been

for my mess tin (full of Army biscuits) which the pieces of shell

struck first, I should have been killed outright . . . .

Frank Sheerman did recover sufficiently from his wounds and

subsequent operation to re-join his regiment, the Royal Bucks

Hussars. In November 1916 he was appointed Depot

Sergeant-Major at Buckingham, his duties including responsibility

for enlistment, clothing and the posting of recruits.

――――♦――――

|

|

|

Lieut. Samuel Kesley. |

Serving in the same regiment was LIEUTENANT SAMUEL

KESLEY of Miswell Lane, Tring, a

sorting clerk and telegraphist in civilian life. Samuel

enlisted early in the war, in September 1914, and was invalided home

from the Dardanelles a year later suffering from enteric fever from

which he recovered. Posted abroad again, in June 1918 he wrote

a letter from Palestine, which was published in Tring Parish

Magazine. Due to censorship one can only guess at his

exact role in the Middle East campaign: [10]

I have been moved from camels to

donkeys. The corps is under the same administration as camels,

and is newly formed so of course it has to be officered, and I have

been selected as one of them and posted to No.1. It really is

a big scream. I wish you could hear the noise at feeding time.

I have 500 of them, and it is a regular Donnybrook!

[a horse fair in Dublin. Ed.] Of

course I am no longer on the Coastal sector and probably shall have

a chance of getting to Jerusalem which is about 25 miles distant but

the country is about the worst I have ever struck. It is very

mountainous with hardly any cultivation and the mountains are

covered with huge boulders of rock and only donkeys can get about

them with the exception of goats. But they are not forming a

goat corps yet! We seem to be away from the world here, away

in the hills. Everything is very quiet except for the hum of

an aeroplane; it seems almost living a hermit’s life.

Later: At last I have seen Jerusalem. Just before entering the

city, Neby Sainwil, the traditional tomb of the prophet Samuel, is

clearly visible from the road. This is where some of the

stiffest fighting took place and one cannot understand how our boys

overcame such strong positions, it was superhuman. I took a

guide to the Holy Sepulchre, there I saw Our Lord’s tomb. The

church which it is built over is very beautiful inside. I

cannot say what passed through my mind as I stood by the side of His

tomb, but everything seemed to be at peace. I also saw the

mosque of Omar, the Jews’ waiting place, and the Garden of

Gethsemane. It is hard to realise all that happened here.

――――♦――――

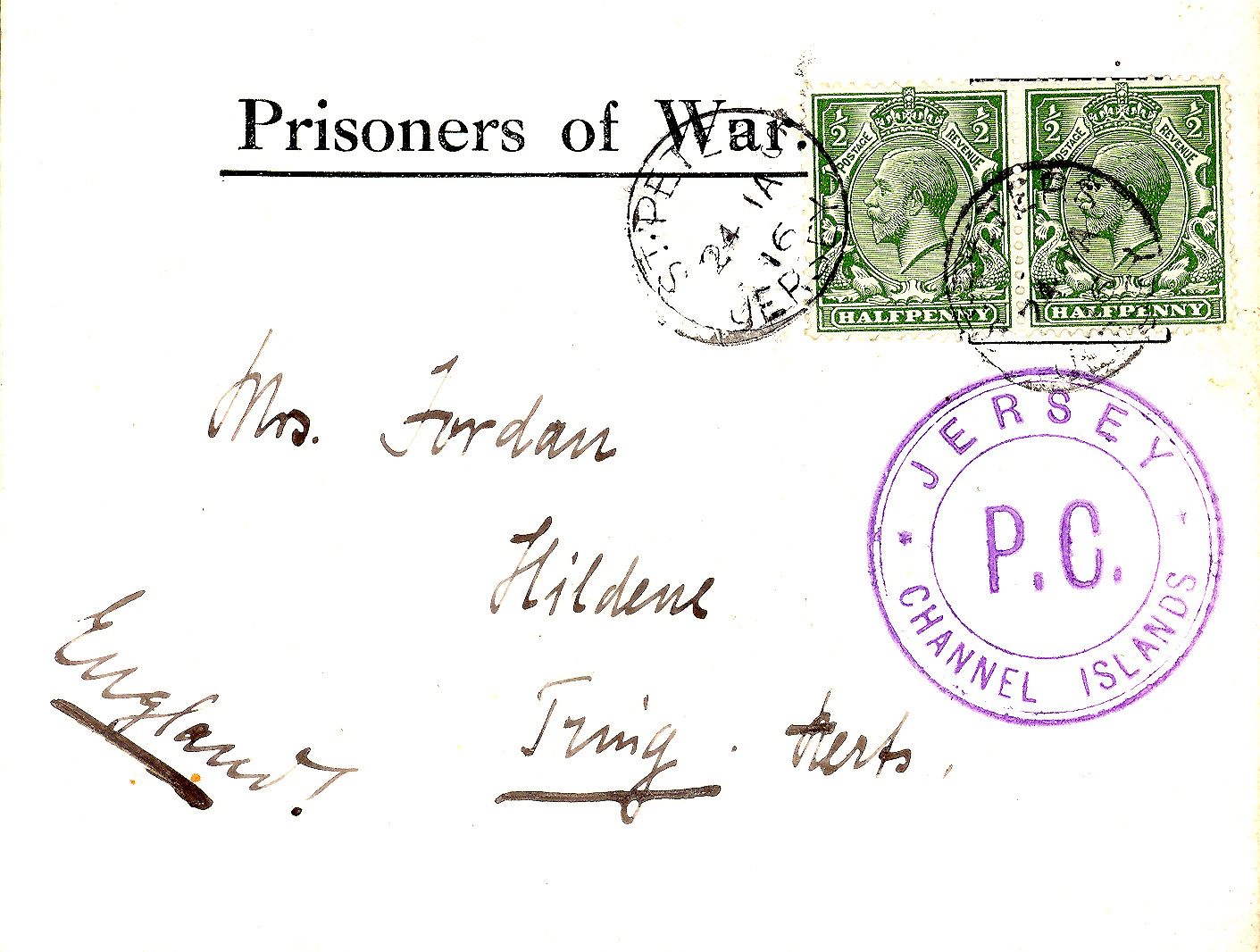

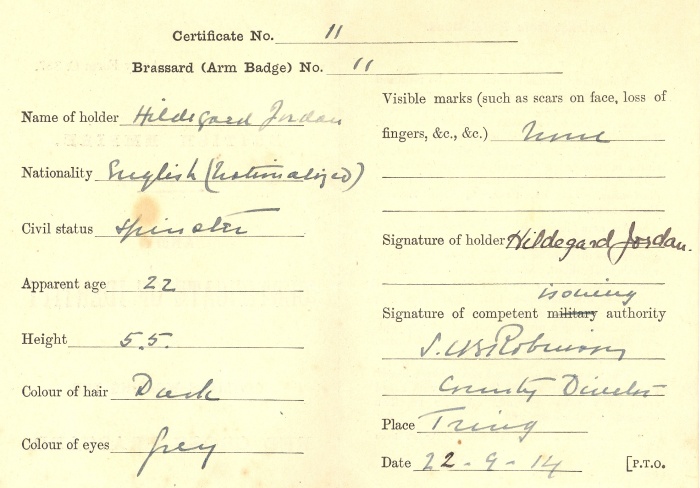

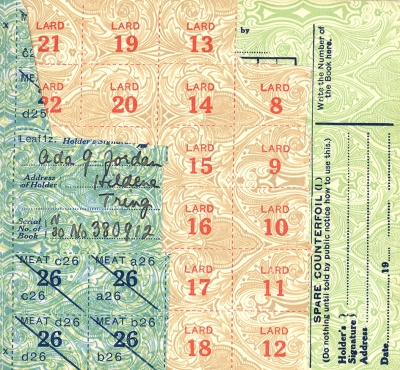

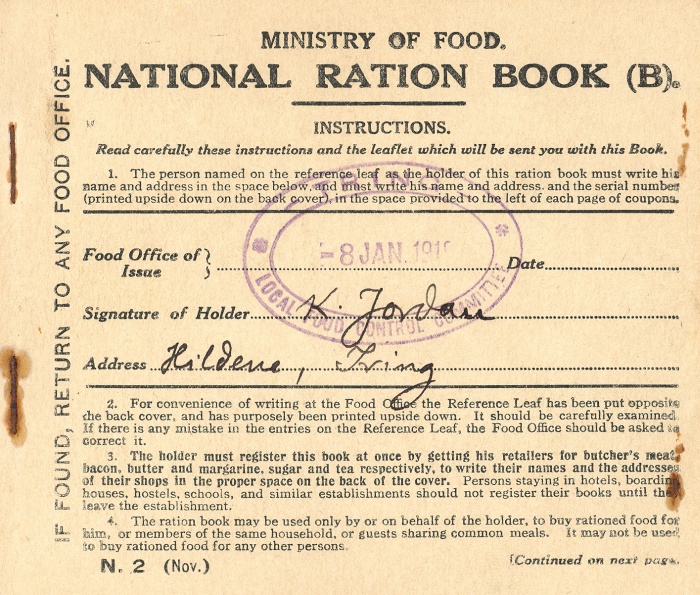

Minna Jordan, of Hildene, Aylesbury Road, [now the site of St

Joseph’s Retirement Home] wife of one of the curators at the

Zoological Museum [The German Connection] maintained a regular correspondence with men serving

abroad. For instance this, written in pencil:

4th October 1918

Signal Section, 77th Infy. Brigade Headquarters,

British Salonika Force.

Dear Mrs. Jordan,

You have no doubt heard that this little war is all over. We

are looking forward to having a quiet winter. A fortnight ago

we had rather a lurid period, but just now we are sitting quietly in

a fertile valley in Bulgaria, doing nothing.

There is a rumour of another move, but I think it will only be a

short one. By the time you receive this it will be just a year

since I was last at Tring. Isn’t it a fearfully long time . .

. .

I am afraid there is not much hope of us returning to England now.

I am afraid they are more likely to send us to a cheerful place like

Albania. However, I am due to have leave in about a year’s

time. I enclose my latest photograph. It is really

intended to be principally a photograph of my horses. The one

I am riding is Mike, who is large, beautiful and stupid; the one the

groom is riding is Rajah. He is old and ugly but very fast.

There is very little news of interest. I am quite well.

I have passed through the summer with no malaria.

With best wishes to all at Tring,

Yours sincerely,

Robert H [surname illegible]

|

|

|

|

From Hans Michael, Jersey

Camp, Channel Islands. |

PRIVATE GEORGE DELDERFIELD

of the School House, Tring, had been missing for some time, but in

June 1918 his wife received a letter from him saying he was quite

well and being held prisoner in Bulgaria. He was engaged in

gardening, an occupation of which he was quite fond, and his only

need was a supply of clothing.

Other Tring men in the armed forces found themselves in far-flung

corners of the conflict that claimed less attention than France and

Belgium. Some served in Gallipoli, Italy, Mesopotamia, Egypt,

Lebanon, Palestine, German East Africa, and Syria, and among those

who died are:

PRIVATE JOHN RUSSELL

HEDGES, 1st/5th Battalion Bedfordshire

Regiment, died of pneumonia in Palestine in a field ambulance five

days after the Armistice in November 1918. He is buried in

Beirut, Lebanon. His chaplain wrote to his mother “We laid

your son to rest at Mar Tatlar, near Essafa, on a gentle slope

overlooking the sea, and his funeral (with military honours) was a

most impressive one”. On the same day, PRIVATE

ARTHUR LOVELL,

54th Machine Gun Corps, Norfolk Regiment, died of malaria in Lebanon

and is also buried in Beirut; his brother, LANCE-CORPORAL

FREDERICK LOVELL,

had been killed in France two years earlier.

LANCE-CORPORAL WALTER

RANCE, 2nd Queen’s Royal West Surrey

Regiment, was killed in action on 30th October 1918, and lies in

Tezze British Cemetery north of Venice. He had been a member

of Tring YMCA and the local Fire Brigade, before enlisting in 1916,

being posted first to France where he was wounded, and then for 12

months to Italy where he took part in the last big offensive against

the Austrians.

CORPORAL STANLEY MILLER,

1st Bucks Hussars, after surviving the Gallipoli campaign, was

transferred to the Palestine Expeditionary Force. He was

wounded severely on 1st June 1917 by what was described as a “piece

of bomb dropped from an aeroplane”; he died the following day in

an Australian stationary hospital and was buried in Kantara War

Memorial Cemetery, Egypt, on the eastern side of the Suez Canal.

Two days later PRIVATE ERNEST

GEORGE WRIGHT,

4th Battalion Essex Regiment, of Brook Street, Tring, who saw

service in France before being posted to Palestine, was laid to rest

in the same cemetery.

Kantara War Memorial Cemetery.

|

If I should die, think only

this of me:

That there’s some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England.

Sub-Lieut. Rupert Brooke [11] |

――――♦―――― |

|

LETTERS AND

PARCELS

As the war dragged on towards the end of its third year, William

Mead, owner of the Tring Flour Mill at Gamnel and a great local

benefactor, sent a Christmas parcel to each man, not only to those

who worked for him at the mill or on his farms, but to every New

Mill lad serving abroad. Twenty-six parcels were despatched to

France in response to which William Mead received eleven letters of

acknowledgment. These he pasted into a scrap book, preserved by his

granddaughter, from which the following five are taken.

A ‘thank-you for parcels’ — Christmas

card sent from France to Tring.

From PRIVATE JAMES GREGORY: 20727, 7th Platoon, B. Coy. 4th

Battalion, Beds Regiment, B.E.F. (in pencil):

Dear Sir,

I am writing a line to thank you for your kindness in sending me the

Xmas parcel which I received safe and sound and I am sure came very

acceptable, also on behalf of my brother Fred I must thank you as he

was killed in our last great advance. He died a brave lad doing his

duty as a Signaller for our Company. He was greatly respected by his

mother and the rule is to share out all parcels with their platoon

mates. We are expecting to soon be in the firing line again.

Wishing you and Mrs Mead a Happy New Year, I remain, yours truly, J.

Gregory.

PRIVATE FREDERICK JOHN

GREGORY, in the same regiment and battalion

as his brother, was killed in action on 14th November 1916. His name

appears on the Thiepval Memorial (soldiers with no known grave) in

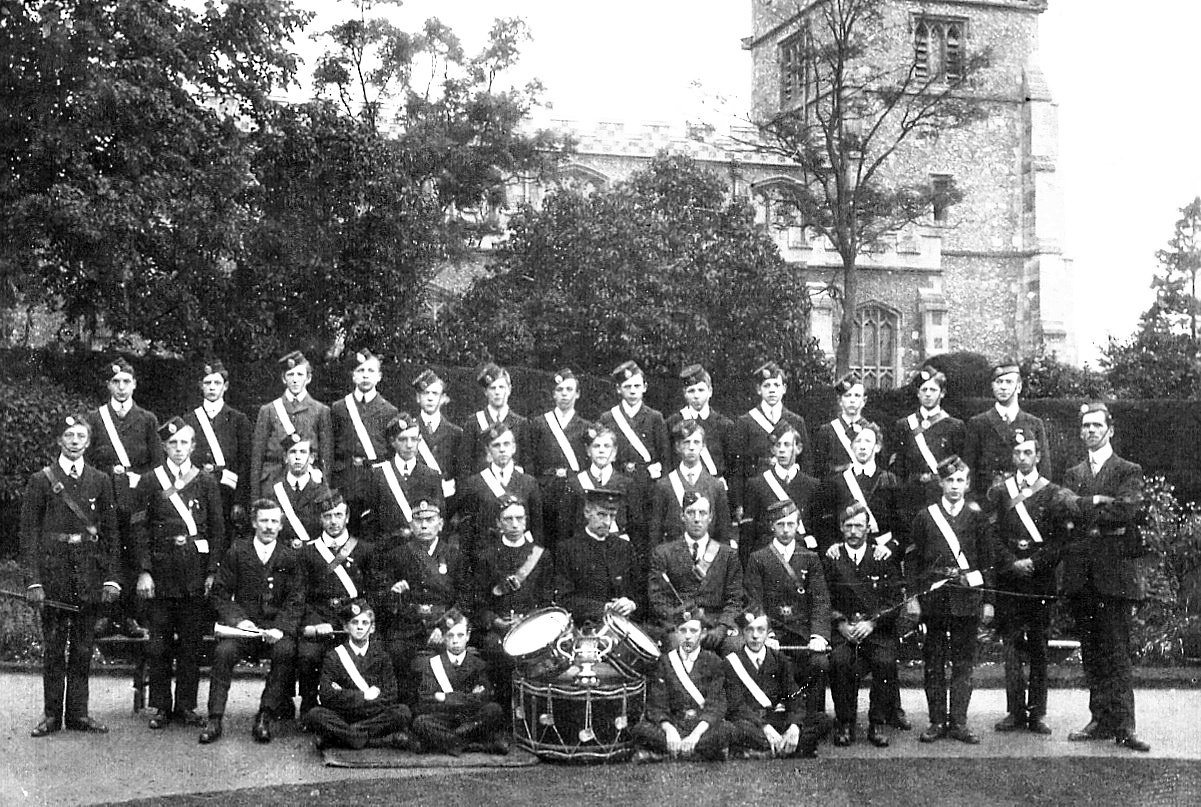

France. The Tring Parish Magazine recorded

“. . . .

Frederick Gregory

was killed as he left the trenches. He joined the Army two years

ago, and has been at the front for the past six months. He is

another of our Church Lads’ Brigade boys to lay down his life in

this war . . . .”

――――♦――――

From GUNNER JOHN NUTKINS: 74795, Royal Field Artillery, B. Battery,

124th Brigade, B.E.F. (written in pencil on paper torn from a pocket

book):

Dear Sir,

Just a line to thank you for the parcel which I received on the 28th

as it came in very handy as we have had it a bit rough lately but I

am like all the others making the best of it we have had some very

rough weather out here hoping you are getting better weather hoping

you had a merry Xmas and happy New Year.

Thanking you again, I remain, yours sincerely J. Nutkins.

――――♦――――

From PRIVATE JOSEPH KEEN: 129973, 2nd Suffolk Co., 3rd Division, B.E.F. (in pencil with a drawing on the envelope):

The Front,

31st Dec. 1916

Sir,

Please accept my best thanks for the nice parcel of “goodies”

received from you today. My mates and self have heartily enjoyed the

contents as a great change from the monotony of Army fare. Please

accept my best wishes for Peace and Prosperity for 1917.

Yours gratefully,

Joseph Keen.

――――♦――――

From PRIVATE EUSTACE PHEASANT: 4438 Headquarters Company, 1st Herts. Regiment, B.E.F. (in pencil):

1st January 1917

Dear Sir,

I am write to thank you very much for the parcel you sent me for

Christmas. It is very kind of you to think of us at such a season,

as of course we are all thinking of the homeland, and it makes us

very grateful to know that we are not forgotten by those at home. We

spent Christmas in the trenches where your parcel reached me, and

the contents were thoroughly enjoyed by my comrades and myself.

The Battalion was lucky enough to have no-one killed on Christmas

Day and only one wounded, so you will guess it was rather a quiet

day. It is very wet and muddy in the trenches this time of the year

and we have to wear gum boots to save getting frostbitten feet, so

you can imagine the state of the trenches in this part. Still

everything is done to make it as good as possible for us, and

altogether we did not spend such an awful Christmas as one might

think. I am sure I am very grateful to you for your kindness and

wish you every success in this New Year.

I remain, yours truly,

E. R. Pheasant

――――♦――――

From DRIVER ERNEST WRIGHT: 3023980, No.3 Company, A.S.C., 20th

Division (in very faint pencil):

Dear Sir,

Glad to say I have received your very nice parcel quite safely for

which I send my warmest thanks. I am sure I enjoyed the contents

immensely by the way. We spent Christmas very quietly out here, as

our Div. were rather unsettled so we kept our Christmas festival up

on Boxing Day and had a fairly good time under the circumstances, as

I also hope you did. Well, I do not think we shall see another Xmas

out here ‘hope not anyway’; as I think the End is now in sight by

what Mother tells me. You also have been having the weather very

rough the ground is in a terrible state here, we even have to have

eight horses on a water-cart. Still I have been very fortunate in

being an Officer’s Servant as I have a great many advantages. I do

not think I should be long now before getting my leave, at the

present rate any turn comes at the beginning of Feb. Well I must now

conclude.

Wishing to be remembered to Mrs Mead,

I remain,

Yours truly, Wright E. J.

――――♦――――

Letter to EDITH, WIFE OF WILLIAM

MEAD, headed 4th King’s B.E.F. (in

pencil, on yellowing torn paper):

15th October 1916

My Dear Mrs. Mead,

Thank you very much for your letter which I was very pleased to

receive, you seem to have been having a really old time of it. I had

quite a good time down at a seaside place but was recalled too soon,

and I had only just got to know the place but still I had quite a

good time while I was there, but coming back I was lost for 4 days

and travelled backwards and forwards without arriving at my final

destination.

How is Mr. Mead and the kiddies, please give my love to both. I

shall remember the good old times I had at “Gamnel”. The weather out

here is pretty wretched, still taking all things into consideration

it is not always so bad as we always have some nights when we get

relieved and have a good time until we go into the line again. I

myself have been on reconnaissance duty lately which I don’t like at

all, it is too lonely altogether. I don’t mind shells when I am with

somebody as one can listen for it coming and then watch the

direction it comes from. But it is far too trying a job doing both

things by yourself. I wrote to Gladys yesterday, how is Dr Clark

please? Remember me to him, also Mr. & Mrs. Honour [?]). I may see

Graham out here, do you know what Division he is in? I had a letter

from old Leslie the other day; he does not seem to be very hopeful

about his eyes [Ed. presumably a wounded friend from home.]

You must excuse pencil and scrawl etc. but it is the best I can

obtain under the present circumstances [damaged section follows]

. . . . Ernest is still carrying on and I am glad he has got exemption. My

love to him and ask him to drop a line when he has time.

Cheeryho for now. I remain, Always your loving friend, ?? [signature

illegible].

――――♦――――

William Mead’s contribution to the war effort had been unceasing. During the period that the soldiers of the Northumberland Fusiliers

and other northern regiments were billeted in Tring, he fitted an

annexe to the mill containing two enormous baths for their use. The

photograph above is an example of the hospitality and entertainment

he arranged at intervals for wounded servicemen both in the garden

of his home, and on the adjacent canal. One newspaper account tells

us that he also invited wounded British and French soldiers for

drives around the countryside in his steam lorry, finishing with

refreshments and games at the mill; those too ill to attend he

visited in the various local military hospitals. And after the war,

William Mead arranged the collection and re-erection of a sizable

army hut, complete with stove, which was sited at the central point

of Gamnel. Periodically refurbished, it served as a Community Centre for a great variety of

activities for nearly a hundred years. [12] |

Envelope from Private

Joseph Keen.

|

Outside Tring Flour Mill at

Gamnel on the Wendover Arm. The Mead family

entertain wounded soldiers and airmen from Halton Camp

on board one of the firm’s narrow boats, 1918 — note the

bandsmen seated beneath the awning. |

William Mead’s effort had been part of a general desire in the town

to let the men know they were not forgotten at Christmas. An account

appearing in The Bucks Herald just after Christmas 1916 gives some

idea of the type of gifts that the parcels contained:

On the suggestion of the Rev. H. Francis

[Vicar of Tring] a representative

committee had been formed, and a number of ladies undertook to

collect the necessary funds . . . .

Donations per lady collector, and others with special donations to

clear the deficit, amounted to £99.19s.0d. . . . . The contents of the

parcels (the number exceeding 300) were supplied by 27 tradesmen of

Tring. A Christmas card, a cake, OXO, cigarettes, soap,

writing pad with paper and envelopes, towel, and a note explaining

that the parcel was a gift from their fellow townsmen in

appreciation of all they were doing and bearing for King and

country, and a box of chocolates and bit of holly were put into

every parcel. The YMCA also added extra cigarettes.

Scores of letters acknowledging receipt of the parcels have already

come in, showing how much the men appreciated not only the things,

but the kind spirit and remembrance which the gifts betokened.

Those who subscribed (772 in all) were well pleased to know how much

their gifts were appreciated . . . .

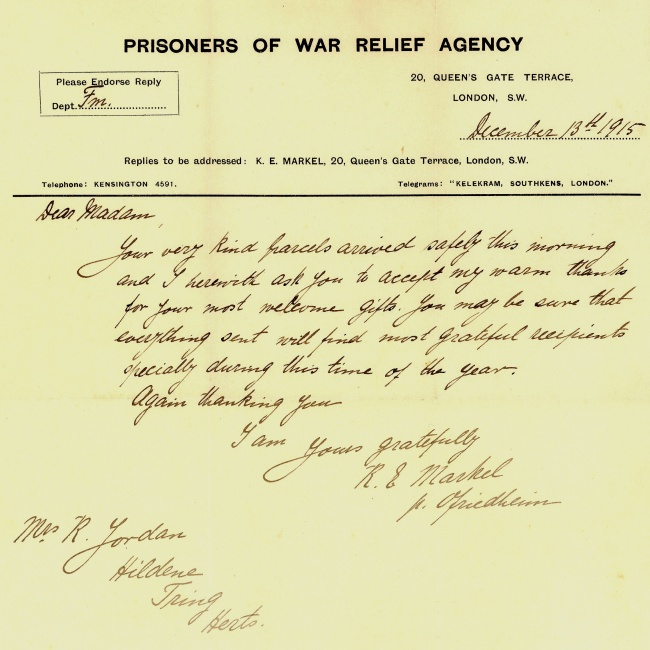

A year previously, real concern was being felt for the men who had

been taken prisoner, and the Cockburn family of Red Lodge, Miswell

Lane, decided to do something about it. The following letters were

printed in the The Bucks Herald:

Tring,

9th November 1915

Sir,

Many of our men who were taken prisoner have now experienced twelve

months captivity in German hands, and we gather from those who have

been fortunate enough to return home that if those left behind are

to survive a second winter in that rigorous climate, it is

absolutely essential that they should receive warm clothing and food

regularly.

We ask, therefore, for contributions in money or in kind – even a

stick of chocolate or a cake of soap will be welcome – and old

underclothing, if warm and in thoroughly good condition, may be

sent. The following list of the most useful articles to send is

supplied by the Prisoners of War Help Committee in London:

Tea, Cocoa Handkerchiefs

Tinned meats Soap, carbolic soap too

Biscuits, cheese Pencils, tooth-brushes

Chocolate Towels

Plasmon chocolate, Bovril Gloves, mittens

Tinned vegetables Draughts, dominoes etc.

Sugar Needles, cottons, buttons

Dried fruits Tobacco, pipes, cigarettes

Force, Grape Nuts Shaving brushes

Will friends order from their grocers a weekly parcel to be sent? The cost need not be great. The benefit to the prisoners will be

immense. These gallant men were fighting our battles till evil fate

overtook them; for us they shed their blood and lost their freedom.

We are now given an opportunity to repay (in part) the debt we owe

them.

Yours faithfully,

J. Cockburn

This letter had the desired result, and Miss Cockburn undertook the

collection and despatch of parcels:

48 Charles Street,

Berkeley Square,

London, W.

My dear Miss Cockburn,

The contents of your glorious box full of comforts will be for the

most part on their way tomorrow. The great coats are quite

splendid. The gloves, mitts, jerseys etc. are most useful.

Some contributors write their names and addresses on the cigarettes,

and I am sorry to say I had to scratch it off, as no scrap of

writing may go through, and if it does there is the chance of the

parcel’s owner being ill-treated, so we have to be very careful.

Helen Woodward,

Lady Burghclere’s Fund

|

If I were fierce, and bald,

and short of breath,

I’d live with scarlet Majors at the Base, [13]

And speed glum heroes up the line to death.

You’d see me with my puffy petulant face,

Guzzling and gulping in the best hotel,

Reading the Roll of Honour. ‘Poor young chap,’

I’d say — ‘I used to know his father well.

Yes, we’ve lost heavily in this last scrap.’

And when the war is done and youth stone dead,

I’d toddle safely home and die — in bed.

Captain Siegfried Sassoon, M.C. |

――――♦―――― |

|

LETTERS

FROM

CLERGYMEN

From the REVEREND CHARLES

PEARCE, Minister of the United Free

Church in Tring High Street, to The Editor of The Bucks Herald:

Fernlea, High Street, Tring.

10th November 1915.

Dear Sir,

|

|

|

The Rev. Charles Pearce. |

Much, but not too much, has been written about the officers and men

of Halton Camp and at the Front. I believe you will think a

line or two about our Hospitals worthy a place in your valuable

paper. Neither rose nor rainbow gain anything from painter or

poet, and deeds of mercy require no flourish of the pen. A

simple statement will be enough to show the skill, sympathy, and

success of the doctors, their staff, and assistants. We have

had three Military Hospitals in Tring for considerably over 12

months (a number of the wounded from the Front are now here); but,

as far as I remember, we have had only three deaths. Surely

this must form a record. Some of these were very seriously ill

before admittance. I have been deeply touched by the tears in

the tone: “We did our very best, but could not save him”. The

men seem to have undoubted confidence in the medical staff and their

helpers. The monotony of indoor life is just now largely

increased by the darkened windows. But all are hopeful of

brighter days.

Yours etc.,

Charles Pearce,

(Army Chaplain)

Later in the war, in addition to his already considerable duties,

Reverend Pearce received the distinction of being appointed

Officiating Chaplain in local military hospitals to the Wesleyans,

Presbyterians, Congregationalists, Primitive and United Methodists,

and Baptists, thus filling the unique position of representing all

of the Free Churches.

――――♦――――

From: ACTING CHAPLAIN TO

THE FORCES GUY

BEECH: [14]

19th December 1915.

My dear Friends,

|

|

|

Rev. Guy Beech. |

As most of you will know before this letter is published, I have

been appointed to temporary duty as an Acting Chaplain to the

Forces. I shall therefore be leaving Tring for a time after

Christmas; but, at least for the present, I am not going far away .

. . .

It is with much regret that I leave the Vicar, and the Parish with

an incomplete staff of clergy, but those in authority over me in the

Diocese consider that I can reasonably be spared from here at this

time of crisis in Church and Nation.

You will, I am confident, readily forego some of the spiritual

ministrations to which you have been accustomed in your country’s

hour of need. May I further appeal to all who can do so to

offer their help, each in his or her several capacity, in the work

of the Church at this time. We ought not to expect everything

as usual, but much of the Parish work, notably the Sunday Schools,

can hardly be carried on at all unless new helpers will come forward

to take the place of those who have been called away on active

service . . . . The services of intercession in connection

with the war, in which I have taken part with you week by week for

so long will have a very special place in my thoughts when I am

away.

Your faithful servant

Guy Beech

Later Guy Beech was posted “somewhere far away”. He did

not return to Tring after the war, going instead to the Rectory of

Turvey, near Bedford. He wrote from France on 3rd May 1918:

As the address shows you, I am now

attached to ‘The Diehards’ [nickname for the

Middlesex Regiment, Duke’s of Cambridge’s Own].

My last letter was written just before I left the reinforcement camp

to join the division. Eventually I reached it close to the

town I had left the week before. I was posted to this

battalion whose padre had been killed in recent fighting. But

how long I shall be with it is uncertain as it seems likely to be

broken up, which will mean my being transferred to some entirely

different unit. Most of the men have been drafted away and

their place may possibly be taken by Americans. We have been

perpetually on the move from one village to another, in back areas

quite a long way from the fighting line. We are billeted first

in one and then another French house, usually a farmhouse built

foursquare like an Oxford college quad, and usually with a refuse

heap in the centre!

In the last village my bedroom overlooked a pretty little valley

with an aerodrome on the opposite hill, and on clear evenings I used

to watch the aeroplanes come out one after the other from their

hangers, like wasps from a nest, and go off in formation, laden with

bombs for the enemy territory.

Here, in another farmhouse, I am roused at dawn by the old French

peasant starting forth with his plough and horses for the fields.

The French are indeed wedded to the soil. Everywhere you see

them working on the land, the women and old men, and there they are

from sunrise to sunset every day. Doubtless it is one great

reason for the strength of France, and one can’t help wishing we

English people loved the soil as they do.

We are under orders to move again tomorrow and have a 17-mile march

before us.

――――♦――――

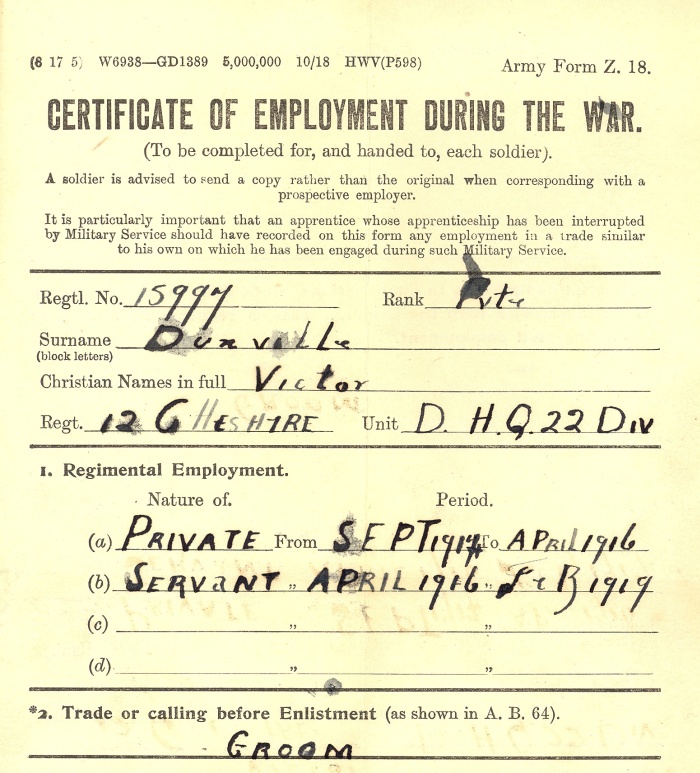

A few letters from MAJOR THOMAS

VERNON GARNIER,

12th Cheshire Regiment survive. [15] After his Army discharge, he

arrived in Tring to take up the position of vicar at the Parish

Church. He had become ill in Northern Greece in the Salonika

theatre of war and gradually recovered in Stavros Hospital, from

where he sent instructions to PRIVATE VICTOR

DUNVILLE, the soldier who had served as

his batman. It was obviously a successful relationship, as the

Reverend Garnier was anxious that Victor should remain in his

service at Tring Vicarage, acting as his manservant and chauffeur.

Thomas Garnier served as vicar of Tring from 1919 to 1930; described

as rather an austere man, nevertheless he was much respected.

He married Helen Stenhouse, daughter of a retired tea-planter living

in Tring, and they had three children. He died in 1939, aged

64. Garnier scribbled the following letter in pencil:

To: Private V. Dunville

Stavros Hospital

6 January 1918

My dear Vic,

I have been very ill or I would have written before and they tell me

that I am now for home, so if I were you I would just concentrate on

getting demobilized as quickly as possible and not bother too much

about getting back to Division. Yes, I am counting on your

coming with me after the war and I can’t tell you how I have missed

you – nobody will ever take your place as far as I am concerned.

At present I am negotiating about a parish. I tried my best to

get you up (Col. Holden got a direct order from GHQ for John

[Garnier’s other soldier servant];

perhaps it means early demobilization for you.)

Yours sincerely,

T. V. Garnier

December 1918

My dear Vic,

I was so glad to get your two letters and to hear you had got safely

home. Your mother and father must have been delighted to see

you after all this long time. We know nothing of our future

movements but people hope that we may be demobilized in February, if

so we shall not do so badly. There was a lot of trekking soon

after you left and so you did not miss much. I rather doubt

your being sent back here and I hope you will not be for we might

just miss each other.

As soon as ever I know my plans I will let you in, in the meantime

perhaps you could carry on with something. If you could learn

or pick up something about motor driving it might come in very

useful, as when I come home I meant to pay for your having some

lessons but with the long interval between letters it is useless to

try and make any arrangements from here, and so I must leave it to

your judgment what to do till we meet.

Isn’t it a blessing it is all over? But of course everybody

finds this waiting about very trying. Booth

[John Booth, Garnier’s other soldier servant who also accompanied

him to Tring after the war. Ed] has done