|

From

THE SCOTSMAN

14 May, 1845.

THE LATE THOMAS HOOD. |

|

—was the son of Mr Hood, the Bookseller, of the firm of Vernor and Hood.

He gave to the public an outline of his early life, in the "Literary Reminiscences" published in

Hood's Own. He was, as he there states, early placed "upon lofty stool, at lofty desk," in a merchant's counting-house; but his commercial career was soon put an end to by his health, which began to fail; and by the recommendation of the physicians he was "shipped, as per advice, in a Scotch smack," to his father's relations

in Dundee. There he made his first literary venture in the local

journals: subsequently he sent a paper to the Dundee Magazine, the editor of which was kind enough, as Winifred Jenkins says, "to wrap my bit of nonsense under his Honour's kiver, without charging for its insertion."

Literature, however, was then only thought of as an amusement; for on his return to London, he was, we believe apprenticed to an uncle as an engraver, and subsequently transferred to one of the Le Keux.

But though he always retained his early love of art and had much facility in drawing, as the numberless quaint illustrations to his works testify, his tendencies were literary, and when, on the death of Mr John Scott, the

London Magazine passed into the hands of Messrs Taylor & Hessey, Mr Hood was installed in a sort of sub-editorship.

From that time his career has been open and known to the public.

The following is, we apprehend, something like a catalogue of Mr Hood's works, dating from the period when his "Odes and Addresses," written in conjunction with his brother-in-law, Mr J H. Reynolds, brought him prominently before the public:—"Whims and

Oddities;" "National Tales;" "The Plea of the Midsummer Fairies" (a volume full of rich, imaginative poetry); "The Comic Annuals," subsequently reproduced with the addition of new matter

as "Hood's Own;" "Tylney Hall; "Up the Rhine;" and "Whimsicalities; a Periodical Gathering."

Nor must we forget one year's editorship of "The Gem," since that included "Eugene Aram's Dream," a ballad which we imagine will live as long as the language.

Of later days Mr Hood was an occasional contributor to Punch's casket at mirth and benevolence; and, perhaps, his last offering, "The Song of the Shirt," was his best—a poem of which the imitations have been countless, and the moral effect immeasurable.

[The above short memoir is extracted from a kindly notice of Mr Hood in the

Athenæum, and gives a general idea of his multifarious labours.

Mr Hood's reputation is chiefly founded upon his unequalled talents as a wit and humorist, but he had many higher claims upon the voice of fame.

He was possessed of poetical powers of no mean order, as many of his descriptive sketches amply testify; and the ballad, "Eugene Aram's Dream," mentioned in the preceding sketch, is one of the most powerful pictures of the workings of remorse and guilty terror to be found in any language.

As a novelist, also, Mr Hood is worthy of a high place; and though "Tylney Hall" is the only regular novel he has ever completed (for a second was being published in "Hood's Magazine," under the title of "Our Family," when the author's hand was arrested by his final illness), yet it alone is amply sufficient to establish his excellence in this department.

We perceive that some regret has been expressed that Mr Hood should have expended his genius upon the light periodical literature of the day; but in our opinion such expressions are less justifiable than they at first eight appear to be.

His writings in magazines and elsewhere have cheered the leisure hours of many whom otherwise they might never have reached; he has diffused among thousands of his countrymen much innocent and cheerful amusement, thus contributing largely to the general fund of happiness.

And not only so, for the majority of his works were of such a nature as to instruct as well as to amuse—to improve the heart and the feelings, as well as to gratify the imagination.

The moral tendency of Mr Hood's writings was always of the highest and most unimpeachable kind, his sympathies were strong and active, yet tender and sensitive, and even in his most light-hearted moods, he would sometimes touch some of the hidden springs of the heart, and delicately appeal to the most tender and sacred feelings of our nature. There was often deep thoughtfulness in his smiles, and tears would sometimes mingle with his most joyous laughter.

We quite concur in the opinion of the writer in the Athenæum, that "the world will presently feel how much poorer it is for Hood's withdrawal."]

|

|

____________________

Advertisement for

lecture engagements, 1852.....

LECTURES!!! |

|

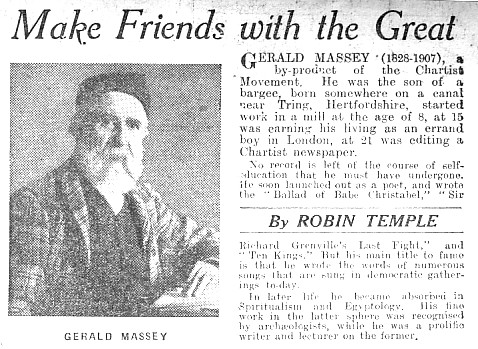

GERALD MASSEY,

Author of "Voices of Freedom and Lyrics of Love," will deliver lectures on

the following subjects, to Working Men's Associations, Mechanics

Institutes, &c., &c., who may think fit to engage his services.

|

A course of Six Lectures on our chief living Poets.

A course of Six Lectures on English Literature, from Chaucer

to

the present time.

Cromwell and the Commonwealth.

The Poetry of Wordsworth, and its influence on the Age.

The Ideal of Democracy.

The Ballad Poetry of Ireland and Scotland.

Thomas Carlyle and his writings.

Russell Lowell, the American Poet, his Poems and

Bigelow Papers.

Shakespeare—his Genius, Age, and Contemporaries.

The Prose and Poetry of the Rev. Chas. Kingsly.

The Age of Shams and Era of Humbug.

The Sonz-literature of Germany and Hungary.

Phrenology, the Science of Human Nature.

Chatterton, a Literary Tragedy.

The Life, Genius and Poetry of Shelley.

On the necessity of Cultivating the Imagination.

American Literature, with pictures of transatlantic Authors.

Burns, and the Poets of the People.

The curse of Competition and the beauty of Brotherhood.

John Milton: his Character, Life and Genius.

Genius, Talent and Tact, with illustrations from among living

notables.

The Hero as the Worker, with illustrious instance of the

Toiler

as the Teacher.

Mirabeau, a Life History.

On the effects of Physical and mental Impressions. |

For particulars and terms, apply to Gerald Massey, 56, Upper

Charlotte-street, Fitzroy Square, London

In answer to some communications which I have received from

good friends in provincial towns, &c., I may say that with the coming

spring, I intend making a lecturing tour through the Country, should I

succeed in making satisfactory arrangements.

GERALD MASSEY. |

|

____________________

MS. National Library

of Scotland.

FRESHWATER, I. OF WIGHT,

April 1, 1854

My dear Sir

In consequence of my change of residence I did not receive your

captivating volume till yesterday. I am no reader of papers and reviews;

I had not seen, nor even heard of any of your poems; my joy was all the

fresher and the greater in thus suddenly coming on a poet of such fine

lyrical impulse, and of so rich, half-oriental imagination. It must be

granted that you make our good old English tongue crack and sweat for it

occasionally; but Time will chasten all that. Go on and prosper and

believe me grateful for your gift and

Yours most truly

A. Tennyson.

|

|

____________________

MS. National Library

of Scotland.

FARRINGFORD, FRESHWATER, I.

OF WIGHT, July 11, 1855

Dear Mr. Massey.

Will you accept a little volume from me of my own poems? I have

ordered Moxon to forward one to you. My mother now between 70 and 80,

one who takes far more interest in the next world than in this, and not

generally given to the reading of literature, was quite delighted with

your paper in Hogg's Instructor. Believe me, dear Mr Massey,

Yours very Truly

A. Tennyson

|

|

____________________

MS. John Hopkins

11 August 1855

Dear Mr Massey

Many thanks for the Critique in the Edinburgh paper [Ed.―Edinburgh

News and Literary Chronicle, 28th July] which I suppose you sent me.

You have done wisely in not attempting, as most other of the periodical

writers have done, a full explanation of the poem. Men should read and

ponder over a work before they judge it: to prejudge it is ten to one to

misjudge it.

I trust you got a copy of Maud which I sent you, inscribed. I believe

you are quite right as to the conclusion of the Charge. I sent you a

copy of that version of it which I have just transmitted to the Crimea.

The Secretary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel out there

told a friend of mine that the ballad had in some strange way taken the

fancy of the soldiers: that half of them were singing it but that they

all knew it in fragments and that [all of them wanted it in black and

white. The chaplain of the Society wrote to the Society. 'You can do

no greater service] just now than to send out copies of the Charge

on slips for the army to sing.' Who could resist such an appeal? This is

the soldier's version and I dare say they are the best critics.

I trust my dear sir that you are by this time somewhat reconciled to the

loss of your child. Believe me,

Yours most truly

A. Tennyson

|

|

____________________

MS. Cornell

University

January 3, 1870

Dear Mr. Massey

I thank you for your Poems [Ed.—A Tale of Eternity and Other Poems

(1870)] and I send you an inscribed copy of The Holy Grail according to

your desire. I have been waiting for it or I should have answered

your note before.

I am by no means sure of being at home on 27th February but if you will

kindly give me an opportunity of communicating with you immediately

before I will let you know whether I am or not.

As to telling you what I think of your book, I am sorry that I cannot

promise to do much of that, having, as I think you know, been obliged to

decline all or nearly all criticism.

My wife begs to thank you for your inquiries. Believe me,

Faithfully yours

A. Tennyson

|

|

____________________

From

THE SCOTSMAN

24 March, 1858.

|

|

MR GERALD MASSEY’S LECTURES.

— A large audience assembled in the Queen Street Hall on Monday evening to hear Mr Gerald Massey on

"Thomas Hood, and Wit and Humour."

Professor Simpson presided.

Mr Massey introduced his lecture with a pleasing definition of the varieties of wit and humour, and the healthy tendencies or genuine merriment.

As Jean-Paul Richter said, "The tear of holy sorrow is beautiful, but it is the tear of joy that is the diamond of the first water."

Hood's verse drew such tears, although the sad and melancholy predominated in his songs, and was rendered more effective by the force of sudden antithesis.

His humour was of the most ethereal kind....neither coarse, like Swift's, nor sarcastic like Byron's.....his wit was anchored fast in humanity.

That Hood was irreligious in many of his poems Mr Massey denied. The poet ridiculed pretence, hated humbug, exposed all' Pharasaical cant, stripped false sanctimony of its disguise and consumed it to ashes in the fire of his scorn, but with religion he played not.

Having drawn a graphic picture of the remarkable contrast between light and shade which was everywhere to be met with in Hood's

poetry—a contrast influenced equally by his love of humanity as by his own personal misfortunes. Mr Massey glanced at him in his grandest character, as the poet of the poor, into whose sufferings he looked with a friendly and a sympathising eye, and in whose cup of bitterness he had so often and deeply shared.

At the conclusion of the lecture, which was frequently applauded, a hearty vote of thanks was passed to Mr Massey on the motion of the chairman.

|

|

____________________

From

THE SCOTSMAN

27 March, 1858.

|

|

MR GERALD MASSEY'S LECTURES.—On Thursday evening Mr Gerald Massey gave the last of his series of lectures in Queen Street Hall, the subject being

"The Poetry of Alfred Tennyson."

Lord Murray presided.

Mr Massey, by way of introduction, glanced at the two division of

Poetry—the objective and the subjective. Tennyson came under the subjective class; beginning his poetry with minute and careful particularising, and not like those who broadly handled the brush and produced effects not to be desired, his reputation was slowly and securely built.

Many people pretended to view his poetry unfavourably—

thought it vague, involved, and meaningless; but Tennyson never " moved with aimless

feet"—his verse was pregnant with meaning, and though at times subtle and obscure at first sight, this vagueness occurred only when the poet reached one of those eternal truths which, like a cut diamond, might be six -sided, and present as many meanings.

The stream of his speech might be deep—perhaps unfathomable to many—but it was never muddy, except through the splashings and flounderings of the reader.

The great function of the poet was to give expression to the beautiful; and surely he did well who translated a page of that language.

Tennyson's poetry was a world of beauty—not a world like Wordsworth's with the look of eternity in its aspect; not like Shelley's, so fantastic, so aspiring in its forms; not like Keats's, whose deity was Pan, who revelled in a wilderness of sweets, where the very weeds were fragrant; nor like Byron's, which was a volcano extinct.

Tennyson's world was like that fairer world of beauty of which they got glimpses only in the delectable views of the imagination.

It lay near heaven. It had a holy ground; it might be an invisible world to some, but others could glance up at it; it was a world where the mortal met with the immortal, and saw the spirits of the past move by grandly and solemnly, with music, perfect and ineffable, dying away into the faintest spirit-sweetness, seeming to be answered by an ethereal far-off echo in the life that is to come.

The lecturer showed that it required a refined and educated taste to appreciate the poetry of Tennyson, which was noble and moral and pure, having a womanly sanctity pervading it; he contrasted it with the poetry of Byron, noticing how the latter was sunk in self-consciousness, while the former was patriotic, and representing humanity.

He gave several readings from the more prominent of Tennyson's poems, and especially quoted from his

"In Memoriam," which possessed so wide a range of thought and beauty in its expression that he could not but consider it as the greatest poetic effort of the last two hundred

years—the climax and crown of Tennyson's poetic life, to be equalled by nothing he had yet done or would hereafter perform.

|

|

____________________

A letter published in the

THE SCOTSMAN

21 December 1859

|

|

Tuesday, December 20, 1859.

SIR,—Will

you permit me to throw out a suggestion which may possibly be of some benefit to

railway travellers in these snowy days. Yesterday, I came from Darlington

to Edinburgh by the train which was due at 3.35. As you are aware the

North British line is blocked up between Dunbar and Cockburnspath, so that we

had to come round by Kelso. I had to lecture in Falkirk last night.

This I could not do unless we were in time for the six o'clock train. I

made Mr Maclaren, the gentleman sent by the North British Company to clear the

trains through, aware of the fact, and he did all that was possible to reach

Edinburgh by six. Indeed, in spite of the snow, we came from Kelso in

twelve minutes less time than the ordinary train should have done. We were

in at the place for ticket-taking as the clocks were striking six. I ran

up, and the next instant saw the Falkirk train in motion. One minute's

grace would have been sufficient; and that brings me to my point. At a

time like the present, it may happen again that a train going north when a train

is coming from the south may, by giving a minute or two, save a great deal of

annoyance and expense to passengers who may already had enough of both! There

is such a thing as telegraphic communication even where there may be no

friendlier feeling between railway companies. In this case, there were two

or more trains long due, and other passengers than me waiting to go on.

Allow me, on the part of these passengers and for myself, to thank Mr Maclaren,

of the North British Railway, for the energetic and unwearying efforts he made

to ensure safety and attain speed. We all pronounced him to be a "brick."—I am, &c.

|

|

____________________

BRITISH PRESS and JERSEY TIMES

28th Nov., 1862.

MR. GERALD MASSEY'S

LECTURES.—Last evening Mr. G. Massey delivered his first

lecture in the Lyric Hall, his theme being "Sir Charles James Napier, the

Conqueror of Scinde." There were about 150 ladies and gentlemen present.

H. L. Manuel, Esq., took the chair, and, in introducing the lecturer to the

meeting, made a few remarks on the happy change which had of late years taken

place in the transmission of knowledge. Mr. Massey then apologized for his

non-appearance on Wednesday evening, and explained that the occurrence arose

from two circumstances—the late delivery of a letter, and losing the boat by

three quarters of a minute. The greater part of the lecture was an heroic

on one of England's most successful generals. In drawing the portrait of

Sir Chas. Jas. Napier, the Lecturer aims at accuracy of delineation,

truthfulness of detail, and beauty of execution. He succeeds; and,

although it cannot be said that Mr. Massey is a first-class lecturer, it may

safely be stated that he is a writer of eminence, many of his beautiful lyrics

having won for him a world-wide celebrity. He is a young man who has nobly

fought his way to the present position among the literati, by whom he is

regarded as being much more successful as a writer than as a lecturer. His

lecture last night was frequently interrupted by applause, and, at its close, he

had the additional gratification of receiving a vote of thanks from the

audience.

|

|

____________________

BRITISH PRESS and JERSEY TIMES

29th Nov., 1862.

MR. GERALD MASSEY'S

SECOND LECTURE—The author of "Babe

Christabel" delivered his second lecture in the Lyric-hall last night, when the

number of ladies and gentlemen present very considerably exceeded the small

attendance of Thursday night. His subject was, "England's old Sea Kings;

how they lived, fought, and died." The lecturer appeared to be much more

at home than when drawing a picture of the life and exploits of the Conqueror of

Scinde, for although the tale of Sir Charles James Napier is a good one when

well told, it did not afford such scope for a display of Mr. Massey's high

poetical powers as the theme of England's Sea Kings. Having traced the

origin and progross of our maritime life up to the time of Elizabeth, Mr. Massey

showed clearly that we are deeply indebted for our supremacy on the seas the

genuine courage of the great Queen and the bravery of her admirals, foremost

among whom was the indomitable Drake. Its tells an excellent story,

showing the animus of haughty Spain, who instructed her admirals not to fail in

accomplishing two objects viz., "Take the Queen prisoner, and kill the Drake."

Fortunately for us, they did neither. The lecturer's descriptions of our

naval exploits were heart-thrilling and brilliant, and were received

enthusiastically by the audience. In the absence of Colonel Nicolle, Mr,

Wellman presided, and, at the close of the lecture, proposed a vote of thanks to

Mr. Massey, which was carried by acclamation.

|

|

____________________

BRITISH PRESS and JERSEY TIMES

5th Dec., 1862.

MRS. GERALD MASSEY'S

POETIC READING.—The talented wife of

the author of "Babe Christabel" gave a poetic reading last evening in the Lyric

Hall, about three parts of which were occupied by an intelligent audience of

ladies and gentlemen, with a few children. If an exception be made to the

weakness of this lady's voice, it may be said, with truth, that she reads very

well; her expression is sweet and pleasing, and her enunciation distinct.

The poems which she read embraced several of her gifted husband's best

productions, interspersed with choice selection from the Poet Laureate, Russell

Lowell, and poor Hood. Massey's touching "Poor Little Willie" was

charmingly rendered, as was also the poem "Nelson" (by the same author) and

"Lady Clare," by Tennyson. To Russell Lowell's enticing piece "The Courtin',"

full justice was done. That most pathetic piece of Hood's, "The Death

Bed," brought tears to many eyes, which were again lighted up with the treat of

"Under the Mistletoe," Massey's "Nicholas and the Lion," had many admirers, who

received a decided accession to their numbers when "Our Wee White Rose" was

given. "Sir Richard Grenville's Last Fight," is a fine production,

rendering infinite credit to the noble heart of the author. The

interesting entertainment closed with "A National Anthem," by Massey—the

auditory being evidently much gratified with what they had heard. We may

add that Mrs. Massey made a few pertinent remarks on the eminent poetic

abilities of the truly great Victor Hugo.

|

|

____________________

BRITISH PRESS and JERSEY TIMES

8th Dec., 1862.

MR. AND MRS.

MASSEY IN GUERNSEY.—We condense the

following from the Guernsey Star:—

On Monday evening a highly respectable audience, composed of

about 600 persons, assembled in the hall, the chair being occupied by Peter

Stafford Carey, Esq., Bailiff. To aid in a just appreciation of Mr.

Massey's merits we would mention that he is entirely a self-educated and

self-made man. The child of honest labouring parents, he at a very early

age, became a worker in a silk mill, and from thence went to London as an errand

boy. But he had that within him which compensated for the want of worldly

advantages, and by indomitable perseverance in reading he so trained himself as

to become a correct and able writer, stored his mind with various knowledge, and

at length made for himself a name amongst the lyrists of the day, affording in

his own person an encouraging example of what may be achieved by perseverance

applied to the culture of natural talent.—The subject subject of Mr. Massey's

reading on Monday evening was "Old England's Sea-Kings,—how they lived, fought

and died." It is not our purpose to follow Mr. Massey through his lecture.

He propounded the theory that the fighting element of the Anglo-Saxon character

was derived chiefly from the old Norsemen who had mixed themselves so largely

with the Celtic and Saxon population of Britain, and he then proceeded to

establish this theory by relating, from the Saga records the warlike deeds of

the Sea-Kings and their hardy followers. There was much of thought,

expressed in powerful and poetical language, in Mr. Massey's lecture, and we

found much to admire in his composition—much to confirm the reputation to which

he has attained. We should observe that Mr. Massey is not an elocutionist,

and that, consequently, his reading did but imperfect justice to his matter.—On

Wednesday evening Mrs. Massey gave readings from her husband's poetry, and from

that of Tennyson, Hood, Russell, and Lowell, before a meeting presided by the

Rev. A. Crisp. Mrs. Massey read in what may be termed "a drawing room"

style, without any attempt at declamation. Her reading was intelligent and

touching and was much applauded.

|

|

____________________

From

THE LIVING AGE

Volume IV, 1867.

|

|

JEAN INGELOW,

THE POETESS.

"WILL

you come and call on Jean Ingelow?” said my hostess, one fine day.

Of course I would. So away we went along a shady lane, with the old

oaks of Holland Park on the one side and the ivy-crowned walls of Aubury

House on the other; for, though a part of London, Notting Hill is rich in

gardens, lawns, and parks, such as one sees only in England. Our way

led us by Kensington Palace, the residences of Addison, the Duke of

Argyle, Macaulay, and, better than all the rest to me, the house of

Thackeray. A low, long brick house, covered with ivy to the chimney

top; a sunny bit of lawn in front, trees and flowers all about, and,

though no longer haunted by the genial presence of its former master, this

unpretending place is to many eyes more attractive than any palace in the

land. I looked long and lovingly at it, feeling a strong desire to

enter its hospitably open door, recalling with ever fresh delight the

evening spent in listening to the lecture on Swift long ago in America,

and experiencing again the heavy sense of loss which came to me with the

tidings that the novelist whom I most loved and admired would never write

again. Leaving my tribute of affection and respect in a look, a

smile, and a sigh, I gathered a leaf of ivy as a relic, and went on my

way. Coming at last to a quiet street, where all the houses were gay

with window boxes full of flowers, we reached Miss Ingelow’s. In the

drawing-room we found the mother of the poetess, a truly beautiful old

lady, in widow’s cap and gown, with the sweetest, serenest face I ever

saw. Two daughters sat with her, both older than I had fancied them

to be, but both very attractive women. Eliza looked as if she wrote

the poetry, Jean the prose —the former wore curls, had a delicate face,

fine eyes, and that indescribable something which suggests genius; the

latter was plain, rather stout, hair touched with gray, shy, yet cordial

manners, and a clear, straightforward glance, which I liked so much that I

forgave her on the spot for writing these dull stories. Gerald

Massey was with them, a dapper little man, with a large, tall

head, and very un-English manner. Being oppressed with "the

mountainous me,” he rather bored the company with "my poems, my plans, and

my publishers,” till Miss Eliza politely devoted herself to him, leaving

my friend to chat with the lovely old lady, and myself with Jean.

Both being bashful, and both labouring under the delusion that it was

proper to allude to each other’s works, we tried to exchange a few

compliments, blushed, hesitated, laughed, and wisely took refuge in a

safer subject. Jean had been abroad, so we pleasantly compared

notes, and I enjoyed the sound of a peculiarly musical voice, in which I

seemed to hear the breezy rhythm of some of her charming songs. The

ice which surrounds every Englishman and woman was beginning to melt, when

Massey disturbed me to ask what was thought of his books in

America. As I really had not the remotest idea, I said so; whereat

he looked blank, and fell upon Longfellow, who seems to be the only one of

our poets whom the English know or care about. The conversation

became general, and soon after it was necessary to leave, lest the safety

of the nation should be endangered by overstepping the fixed limits of a

morning call. Later I heard that Miss Ingelow was extremely

conservative, and was very indignant when a petition for women's rights to

vote was offered for her signature. A rampant Radical told me this,

and shook her handsome head pathetically over Jean's narrowness; but when

I heard that once a week several poor souls dined comfortably in the

pleasant home of the poetess, I forgave her conservatism, and regretted

that an unconquerable aversion to dinner parties made me decline her

invitation.

—M. L. Alcott

in the "Queen."

Massey reviews Jean

Ingelow's Poems for the Athenæum. |

|

____________________

From

THE SCOTSMAN

12 December, 1868.

|

|

PORTOBELLO LECTURE—On

Thursday evening, a lecture on the "The Sea Kings of England” was delivered

at the Town Hall, Portobello, by Mr Gerald Massey. The room was completely

filled by a fashionable and attentive audience.

In the first part of the lecture Mr Massey treated of the virtues

and the vices of the old Norse Vi-Kings, of their heroism, endurance of pain,

love of adventure, grim humour, and deep-seated tenderness, as well as of their

influence on our national life and character; in the second, he dwelt on the

revival of the sea-spirit in the Elizabethan Age, and did full justice to the

memory of Granville, Gilbert, Drake and many other worthy.

To show that there was life in the old land yet, he concluded a

most eloquent and animated narrative with graphic descriptions of the cavalry at

Balaclava, and the wreck of the Birkenhead.

|

|

____________________

From

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

17 February 1871

GERALD MASSEY ON SPIRITUALISM.

On Tuesday last, Gerald Massey the poet, lectured at Ulverston,

Lancashire, on "Pre-Raphaelitism, a Plea for Reality." The lecture

was an eloquent, advocacy of "Truth," whether in painting, literature,

sculpture, or religion. In the course, of his remarks Mr. Massey

referred to the supernaturalism of the age. He thought great harm

was done by regarding Spirituality as something to be reached only by an

act of faith. The fact was, life was but a portion of eternity, and

was quite as great a mystery as ever death could be. We wanted more

naturalism in our religion. He looked upon the spiritual world as

ever round about us. He pictured disembodied spirits as ever

carrying on God's work, and occasionally they gave us glimpses of his

glory and his love. That was his idea of the realism of the

supernatural. It had, however, he could assure his hearers, taken

long and deep inquiry to arrive at such a conclusion. Gerald Massey

is a thorough believer in Spiritualism, and his latest work, "A Tale of

Eternity, and other Poems," which appeared simultaneously with Tennyson's

"Holy Grail," is full of his personal experiences. In an article on

the "Self-made Men of Our Times," which appears in last week's Chimney

Corner (an illustrated periodical), the story of Gerald Massey's life

is told, and the writer describes him as "a true poet," and a man of "the

most exalted character." Nevertheless the biographer finds it hard,

as do most of his class, to accept the facts of Spiritualism which Gerald

Massey narrates. This is how be gets over the difficulty:—

"We do not pretend to be very deeply versed in the doctrines

of Spiritualism, nor indeed do we believe much in the supernatural, but we

do not think that such testimony as Mr. Massey's is altogether to be

ignored, though to us it does not appear necessary to go out of the world

of reality to account for phenomena which Spiritualists themselves admit

are only exceptional, and which may be easily accounted for in some

peculiarity of the temperament of the so-called "medium." Every

imaginative mind has experienced its capacity for realising visions which

itself creates, and, by excessive indulgence in this capacity, the mind

may be strained to a state of tension that becomes almost dangerous.

Gerald Massey himself best illustrates this view in the following passage

of this remarkable poem:—

|

'One night as I lay musing on my bed,

The veil was rent that shows the dead not dead.

Upon a picture I had fixed mine eyes,

Till slowly it began to magnetise:

So the ecstatics on their symbol stare,

Until the Cross fades and the Christ is there!' |

But, whatever

the theory that forms the basis of this poem, the utterances that spring

out of it display a mind in the author capable of the deepest and

profoundest thoughts on subjects that affect humanity more nearly than

anything else, and we are very far from agreeing with some of his critics

that such subjects are not fit ones for poetry. What we are, and

whence, and whither we tend, are not questions of mere theology; they are

the questions that man has endeavoured to solve for thousands of years.

Who ever objected, on the score of theology, to Wordsworth's 'Ode on the

Intimations or Immortality,' or to Shelley's 'Hymn to Intellectual

Beauty'? The 'Tale of Eternity'

has the same spiritual tendency, and exhibits a grasp of intellect, in

clearing away the films of matter, and contemplating 'the awful presence

of that Unseen Power' which exists beyond, equal if not superior to

either." |

|

____________________

From

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

5 October 1883

WHY DOES NOT GOD KILL THE DEVIL?

(Man Friday's Crucial Question )

DELIVERED IN ST. GEORGE'S

HALL, LANGHAM PLACE,

LONDON, SUNDAY

AFTERNOON, SEP. 30TH,

1883.

___________

This lecture, the last of the series, was better attended

than any of those previous. The audience had come to know what to

expect, and they took their places with a feeling of familiar confidence.

The lecturer was equally at home, and performed his task with great

freedom. The voice was clear, powerful, and sonorous, and could have

been perfectly heard in any part of a hall three times as large.

There was a flow of humour, and feeling of vivacity about the manner of

delivery which gave a charm to the lecture. It was the most

practical of the series; the application of the whole question.

Though its lively sallies were received with irrepressible laughter, yet

it had an equal proportion of passages that moved the deepest and most

sacred feelings of the audience.

The Lecturer introduced his subject by observing that the

savage laughed at the statement that man could live after death without a

body. The human intellect began by recognising things—thing-king.

The metaphysicians, whom he had called impostors, were literally so, for

they imposed a system of words upon the things that had been previously

observed. Thus Plato bridged over the chasm between the system of

Egypt and the Christian Fathers, leading to chaotic misrepresentation.

Thus the doctrine of the trinity was shown to originate in the phases of

the moon, which, when full, represented the mother, in the quarter it was

the child, while the sharp horn of the new moon was the reproducing male.

These phases represented the moon in totality, as man is represented by

father, mother, and child. The three are one.

The metaphysician uses words without any facts of his knowing

to represent them. Thus the Spiritualist calls certain

manifestations by the name of materializations, and yet knows nothing of

spirit any more than the materialist knows of matter, or the mentalists of

mind. Such people could not explain themselves: like Crusoe, when

Friday asked him if God could not kill the Devil, being so strong, they

pretend not to hear inconvenient questions.

The Lecturer traced the origines of the dualism known amongst

us as God and Devil. These were darkness and light; Cain and Abel,

one of which slew the other; Esau and Jacob, having a feud with each other

even before they were born, they were supplanters and destroyers of one

another. The myths of the Bible representing this dualism were found

amongst savages. Night, or darkness, was the measurer of time, and

observed in advance of light as a fact in nature. The devil, or the

dark brother, took the precedence of God, or the good brother in the

savage myths. The Hebrew Satan was the Adversary—darkness—which

swallowed up the light incessantly. The Lecturer at full length

showed that in early times no devil was understood to be behind the

darkness: the darkness itself was the devil. To illustrate he showed

that the animals after which constellations are named were not animals,

but images of natural phenomena. It was pointed out that the duality

of God and Devil existed in Egypt, and another form, the twin Christ, had

been discovered in the Catacombs of Rome. The duality was then

traced by the speaker into mental and moral states: the enlightened and

dark mind, the flesh and the spirit. The misunderstandings were

pointed out which result from the transference of this primitive fetishism

into modern theology, of which the mind of the present day is the victim.

Luther and Calvin did much to set up the Satan of modern Churches, the Romish Church knowing too much of his antecedents to make much of him.

Having repudiated the mythical Church devil and the hell

where he is supposed to dwell, the Lecturer gave a forcible illustration

of the "devil" revealed by Spiritualism. In powerful language, he

showed how the consequences of earth-life followed the spirit into the

future state, returning again as a tempter to man on earth. But in

some cases man was the tempter of those undeveloped spirits, by holding

out in his own undeveloped vicious state, conditions through which these

evil spirits can approach earth and gratify their passions. The only

devil is the Nemesis that follows broken laws, in heredity, personal acts,

&c. This was a hell more terrible than that of the Church.

To illustrate how evil affects in various ways man's

condition, he read a poem relating a legend of a youth and an angel

passing a dead dog in a state of putrefaction. The youth was almost

suffocated by the bad smell, whereas the angel did not at all perceive it.

Further on they met a beautiful woman. The youth was ravished by her

attractions, whereas the angel could not approach her, the influence of

her surroundings were so disagreeable to him. The decaying dog was

too far down in the scale to affect the angel, whereas the worldly

passions of the woman which fascinated the youth repelled the angel.

The passions, like a fever, had to burn themselves out; when

no trace of them were left in us, then their analogues in the spirit world

would be unable to influence us. When a natural appetite became a

lust, and led the attractions to a lower state, then it was enthralling to

man's spirit. The miser would have to haunt the treasure left on

earth till it was all distributed. By overlooking these

considerations man had failed to recognise the true devil, which every man

has within him, his worse self, which has to be overcome by the better.

The Lecturer then reviewed the many abuses in society that

extend beyond the province of personal effort or responsibility, and

appealed to all to co-operate to destroy the causes of evil prevailing

amongst us. God is not the author of this evil; we shed it on his

creation. It is the consequence of evolution, and has to be

continually combatted with as man rises. Thus treated evils were

blessings in disguise. When a thing is seen to be evil, then it must

be abandoned and substituted by good: and thus the "devil" may be

converted.

The use of pain was shown as necessary to the perfection of

conditions inhuman life. Pain and suffering were not a curse, but

the result of ignorance and its conditions, and therefore an incentive to

improvement. Man is so much of one family that "own-hookism" cannot

be practiced. If the condition of the masses leads to disease, the

wealthy who are better placed may fall victims to the infection. The

condition of the poor was sketched with much pathos; persons "who neither

go to church nor chapel." The sectarian, it was said sarcastically,

would possibly attempt to remedy the matter, by spending money on building

more churches, and appointing another bishop, instead of improved

dwellings for the sufferers from man's avarice. He held that we are

all responsible for the welfare of man as a whole. He ridiculed that

selfish policy which strives for an individual salvation and the "rights

of property" utterly callous as to the welfare of others. There was

enough in the world for the use of all, and man required a salvation by

which everyone would be able to live his best. He was not so

concerned about another world as this one. Here our duty for the

present lay, and by attending to it the best preparation could be made for

what might follow.

But the considerations arising from the fact of a future life

were introduced in a most powerful manner. That there is a realm

beyond the visible introduced a new factor into man's life on earth.

The reign of law extended beyond the visible and the present. There

was no longer the idea of "blind force," but an eye and an intelligence

dominating all things. Spiritualism showed that man is not alone in

the universe, whether there be a God or not. But thought opened up a

vista of possibilities which turned the ground of materialism into a

Godwin's Sands. As to a personal God, he considered it premature to

speak decidedly: a true conception on this point was coming in the future.

He had great sympathy with the atheist, who had no alternative but the

fetish of the primitive man. That kind of God was the cause of

atheism; and it was better to be blind than to see falsely. He

seldom used the name of God; it had been so long taken in vain by the

orthodox blasphemers. With great delicacy of statement the lecturer

regarded the question of God as private with each soul. "It is a

consciousness working under conditions like his own consciousness."

Man's relations to God in the matter of prayer was discussed.

He did not recognise a God that played fast loose with the laws of nature:

a weathercock placed on the top of creation, and which could be turned in

any direction if sufficient human lung power could be obtained to blow it.

The land laws were examined, and the complicity of the Church

in all abuses that demanded legal reform. The bishops would not even

vote for the poor pigeons. The savage sport of the landowners, and

the monopoly it maintained was the inscrutable cause of the origin of much

evil that the Church professed to bewail. The policy of the 30,000

thieves who invaded us as Hastings—the eaters up of the land—was

contrasted with that of the clansmen. The evil of large farms and

fancy farming was pointed out. The productive powers of these

islands had never been tested. The Church stands in the way of any

effort to remove these evils. The Church, indeed, opposed all

progress. Its cruel and unjust plan of salvation was represented by

the vivisection of animals on the plea that such suffering is for the good

of mankind.

The lecture closed with an eloquent appeal for action to be

immediately taken to promote the kingdom of heaven on earth. Though

the Church stood in the way, it was nearly "played out," to use an

American phrase. He called on the misdirected worshippers to get up

from their knees and work for the better kingdom, and do all that might be

required for its establishment. All the evils that exist are of

man's making, and by him alone can they be removed. So God cannot

kill the devil.

_____________

Having concluded his lecture amid great enthusiasm on the

part of the audience, Mr. Massey remarked that before he went on the

platform it had been suggested to him that a vote of thanks should be

proposed to the lecturer. He thought it would be better for the thanks to

proceed from the lecturer; he therefore very sincerely thanked his

audience for their attendance and attention.

_____________

Such are a few heads of a long lecture, which bristled with

gems of thought, poetical language, flashes of wit, deep pathos, and a

thorough and comprehensive treatment of all that is the concern alike of

theology, philanthropy, and reform. No report could give a true idea

of the performance, and there is a charm about Mr. Massey's presence and

manner which greatly enhances the value of his most excellent matter,

expressed only as a poet can phrase it.

The position assumed is a most independent one. All the

vested interests and abuses of society are openly and honestly assailed.

Mr. Massey makes a clean breast of it, and takes his audience freely into

his confidence, even to his most secret thoughts on the most sacred

themes. It is his earnestness and straightforward manner that charm

even those who do not agree with him on all points. His fiercest

thrusts are given with such good humour and pitying love for human

suffering, that no shade of coarse invective or harsh denunciation can be

perceived, Mr. Massey is an embodiment of a new concrete progressive idea.

While he boldly speaks as a Spiritualist, and derives his strongest points

from spiritual sources, yet he has a word of criticism as he goes along.

He curries favour with no class or party, while he is a tower of strength

to all true and sincere reformers.

|

|

____________________

From the

SYDNEY DAILY TELEGRAPH

26 May, 1885.

[Re-published in The Medium and Daybreak, London, 24

July, 1885]

GERALD

MASSEY'S EXPERIENCES IN SPIRITUALISM.

At West's Academy, on Sunday night, Mr. Gerald Massey

delivered a peculiarly interesting lecture on Spiritualism, which he calls

"A Leaf from the Book of my Life." The lecture was chiefly interesting

from being to a large extent a plain statement of extraordinary facts in

Mr. Massey's life, giving support to the belief in a spirit-world which

can and does communicate with this world of ours. In his opening remarks

Mr. Massey said:—

"We have a class of journalists in London who grin for the

public through the horse-collar of the Press. They laugh for their

living, and their duty is to make fun of all that is foreign—the more the

seriousness the greater the absurdity for them. Such jesters are not

wholly unknown to the colonial papers. Their duty is to play the

fool. They have no comprehension and can have no respect for the

love of truth, which alone could compel a man to tender his own testimony

in a case so painfully personal as this. In the course of my life, I

have been a fighter in the forlorn hope of more than unpopular cause.

But these grinning, drivelling fools of the present time need not think

that I am therefore, the champion of an unparalleled imposture. Some

of my hearers would possibly have preferred a short and easy lesson upon

Modern Spiritualism, in which I should tell and teach them the whole that

I have learned, and they could go away, knowing all about it, in 70 or 80

minutes. But what I have to offer to-night is a story of personal

experiences, and I will answer for my facts with as much certitude as Mr.

Cocker has done for his. I speak in all sincerity, and mean exactly

what I say, never doubting that the truth, truly spoken, will ring

truthfully on the touchstone of all true souls. But in relating an

experience so personal and peculiar, it is only fair to myself and my

subject that I should ask your attention to one or two facts which with

the unprejudiced, if there are any such, may count in my favour as an

observer. In the first place, then, I am no visionary, and have no

predisposition to superstition—no predilection for wonder-mongering in any

department. I have had to earn my own living by hard work of various

kinds ever since I was eight years old. During that time I have had

to form the habit of looking facts in the face as fully and squarely as

possible, with the view of getting a good grip-hold of reality. Nor

did I start with any original tendency to 'mooning'—all my abnormal

experiences came unsought. I had no wish to try the spirits—they

tried me too much. My testimony may be questioned on the ground that

I am sometimes called a poet, and poets are supposed by some people to be

born liars. But even in poetry it has always been my desire and

endeavour to get at the truth. I never could derive any inspiration

from unreality, and I have spent some years of my literary life

conscientiously trying to tell the truth. The facts now presented

are those that I recorded just as they occurred."

Mr. Massey then proceeded to explain how he, some 33 years

ago, was invited to see a young clairvoyant, who afterwards became his

wife, and he then narrated some remarkable phenomena which he experienced

through the mediumship of that lady. Many things, for example, were

communicated to him by her while in the trance condition, which could not

be accounted for but by the working of some intelligence external to this

life. Events were recorded by her on the date of their occurrence,

at great distances from them at the time, with perfect accuracy, as

subsequent inquiry proved. Some of these events were trivial, others

were of importance, and one touching instance of this abnormal power may

be related in Mr. Massey's own words:—Washing up one night, my wife said

"Mother is dead!" "Why do you think so?" I asked. "She told me

so, and showed me the letter pushed under the bedroom door with the black

seal upwards. At 8 o'clock the same morning* I saw the letter

pushed under the door by the servant with the black seal upwards, and

which letter verified my wife's vision by announcing the fact. "For

many years," continued Mr. Massey, "I used to look on the trance

conditions as only showing an exalted form of the same personality.

But by degrees I was forced to the conclusion that there was more in it

than one individuality manifesting under some duality of obscure brain

conditions—that, in fact, other persons, individuals, or intelligences had

the power to make use of these conditions, as if they, also, could

magnetise and put their patient into a trance, take possession of the

human machine, and run it on their own account; that these conditions were

those of mediumship betwixt two worlds, the unseen and the seen; and that

the kind of manifestations on the character of the operators were in

keeping with the nature of the conditions. That is, to put it

roughly, health, mental or moral, is conducive to the manifestations of

good or pure spirits; whilst disease, whether mental or moral, lets in the

lower, darker, earth-bound kind of natures to make use of the victim for

their gratification. I know whereof I speak, and if need were I dare

stand here to say what some of you would not dare to sit there and listen

to. Some of us could present facts so hard that they would strike

the blatant sceptic and shut him up dumb, as with a back-handed blow on

the open mouth."

Mr. Massey then gave further facts in proof of spirit

communication, relating one instance where it seemed the spirit of his

wife's mother and of his little daughter absolutely conveyed certain

intelligence by means of rapping, which was the means of preventing his

wife being consigned for a time to an asylum for the insane. He also

referred to a number of manifestations he had obtained, and phenomena

experienced, as for example when he received a direct communication from

Müller, who was hanged on a charge of murder, and in whom he (Massey) had

interested himself in consequence of a communication made through the

medium that Müller did not actually commit the murder, laid to his door.

"As soon as executed he (Müller) purported to come and thank me in trying

to save his poor neck." Other experiences in the same direction,

which the lecturer told his audience were of a weird and gruesome

character, as for example when a certain house** occupied by his family

was haunted for a term by the restless spirit of a departed murderer, the

scene of whose crime was that same house, his victim being an illegitimate

child, whose body he buried in the cellar. In this instance it was

the medium who suffered most, the supposed spirit of the murderer taking

complete possession of her, and in the most horrible language demanding

possession of the discovered bones of the murdered child. "If we had

never touched the other world before, it looked as if we had broken into

it now, and that it responded in a frightful manner. When the

supposed spirit was in possession of her organism, the medium would become

to all intents and purposes a male, consumed with a craze for rum and

clamorous for tobacco. Other and even more peculiar manifestations

were apparent when the seizure was on her and the transformation took

place. It is not my purpose merely to tell you a thrilling story, or

I might repeat some of the details that may be found in 'Tale of

Eternity,' but I would rather set people's brains at work within the skull

than see their hair standing on end outside of it. For myself, I

wonder I did not come out of that awful experience white-haired."

Mr. Massey then quoted a portion of his "Tale of Eternity,"

in verse, giving an account of this particular experience.

Continuing, he said—"Before passing away, the medium promised to come back

and prove her presence with the children by rapping a clock, and those

raps were of common occurrence for years, and at my first sitting with the

medium Home my wife purported to speak to me, giving her experience of the

time when she parted this life. The contact of the spirit-world is

to me as real, as active, as that of the natural world. I have

touched it at various points, and joined hands with it for the doing of

better work in this world. I have proved that spirits can be evoked

whether good or bad, Heaven-soaring or earth-bound, in strict accordance

with the nature of our longings and desires. I have had my own hand

compelled to write without any volition of mind hundreds of times. I

declare when I come to think of it, that these miserable, despised, and

repulsive facts in their mental transformation have been such a lighting

of the earthly horizon, and such a letting in of the Heavens, that I can

only compare life without Spiritualism founded on fact to sailing on board

ship with the hatches battened down, and being kept below, 'cribbed,

cabined, and confined,' living by the light of a candle, and then being

allowed upon some splendid starry night to go up on deck to see the glory

of the starry heavens overhead, and drink in new life with every breath of

the wondrous liberty." The lecturer proceeded at considerable length

with an analysis of the Spiritualist's belief, but was careful to say that

for him the belief was based solely on facts. A Positivist critic

and opponent of his had admitted that he (Mr, Massey) had accumulated and

presented such a mass of facts that it would take half a dozen

philosophers to deal with them. Spiritualism was at once the oldest

and the newest light in the world.

In bringing his lecture to a conclusion, Mr. Massey said he

had to confess that the Spiritualists as a body were possibly the most

curious agglomerate of human plum-pudding-stone in the world, an aggregate

of the most crooky and kinky individualities ever massed together.

They were drawn, but by no means bound together by the facts to which they

testified in common. They were an inchoate and an incoherent cloud

of witnesses. Of one thing only did they speak with one voice.

That was the reality of their facts; the actualities of the phenomena, to

which he bore true witness that night. But mark this. It was

not Spiritualism that created, or was accountable for this bustling crowd

of crooks. They were the diverse outcome of other systems of

thought. They were the warts on the stricken and stunted tree—the

thistles and thorns of uncultivated fields—the wanderers during forty

years in the theological wilderness—the rebels against usurped authority.

They stood with all their divergencies distinct, but massed together like

a chevaux de frise of serried spears around their central truth

whoever might advance against them, or touch it. Spiritualism meant

a new light of revelation in the world from the old eternal source.

The old grounds of belief were breaking up rapidly. The foundations

of the orthodox faith were all afloat. They had built as the

Russians rear their winter palaces on the frozen river Neva, and the great

thaw had come suddenly upon them. The ominous sounds of a final

breaking-up were in their ears. Their anchorage and place of trust

was crumbling underfoot before their eyes. They had built on many

things that had sealed up the living springs and stopped the stream of

prayers. They arrested for the purpose of resting. And here

was the hint of the Almighty that they must move on or be moved off.

Spiritualism, as he interpreted it, meant a new life in the world, and new

life was not brought forth without pain and partings and sheddings of old

decay. New ideas were not born in the mind without the pains and

pangs of parturition, and to get rid of old ingrained errors of false

teaching was like having to tear up by the root the snags of one's own

teeth by one's own hand; but by one's own hand this had to be done, for

nothing else could do it. Light and life, however, did not come to

impoverish, they came to enrich, and no harm could befall the nature of

that which was eternally true. It was only falsehood that feared the

purifying touch of light, that must need shrink until it shivered away.

Spiritualism would prove a mighty iconoclast, but the fetishes and idols

it destroyed would yield up their concealed treasures, as did the statue

which was destroyed by Mahmoud, the image-breaker. The priestly

defenders offered him an enormous sum to spare their god, but he resisted

the bribe, and smote mightily with his iron mace, and as it broke there

rolled out of it a river of pent-up wealth which had been hoarded and

hidden within. "It will take a long time," said a learned professor

the other night, "before this sort of thing—Spiritualism—saves the world."

And this expression of an obsolete system of thought was no doubt

considered to be a "modern instance" of wisdom. But the world had

never been lost, and consequently never could be saved in the sense

intended. Such language had lost its meaning for others. It

had become one of the dead languages of the past. Spiritualism would

have done its work if it only abolished the fear of death, and enabled

them to live as free men and women, who would do their own thinking in

that domain where they had so long suffered from the pretensions of the

sacerdotalists, who ignorantly peddle the name of God—a system of thought,

the sole foundations of which, as it was his special work to show, were to

be found at last in misinterpreted mythology.

* This must mean next morning, unless the

conversation reported took place after midnight. In other places we

have found errors in reporting.—ED.

M.

** Ed.—'Ward's Hurst', at Ringshall near Tring — the

current tenants (2005) still believe the house (in particular, its cellar)

to be haunted.

|

|

____________________

From

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

4 December 1885

Reprinted from the New York Tribune.

MASSEY AS AN EVOLUTIONIST.

_______

THE NATURAL GENESIS. By GERALD MASSEY

2 vols. imp. octavo, pp. 552, 555. London: Williams & Norgate.

Price £1.10s.

This is the second part of a voluminous work undertaken by

Mr. Massey for the purpose of establishing a theory which certainly should

have sober examination. He holds that the origins of the "myths and

mysteries, types and symbols, religions and languages," are to be found in

Africa alone, and that Egypt is the "mouth-piece." Proceeding on the

evolutionary hypothesis he seeks to demonstrate, to quote his own words,

"the Kamite origin of the pre-Aryan matter extant in language and

mythology found in the British Isles—the origin of the Hebrew and

Christian theology in the mythology of Egypt,—the unity of origin for all

mythology, and the Kamite origin of that unity,—the common origin of the

mythical Genitrix and her brood of seven elementary forces, found in

Egypt, Akkad, India, Britain and New Zealand, who became kronotypes in

their secondary and spirits or gods in their final psychotheistic

phase,—the Egyptian genesis of the chief celestial signs, zodiacal and

extra-zodiacal,—the origin of all mythology in the Kamite typology,—the

origin of typology in gesturesigns,—and the origin of language in African

onomatopoeia."

It is clear that if on the one hand this is a sufficiently

audacious and ambitious conception, on the other hand it is a perfectly

legitimate enterprise, and one the implications of which may be most

important. The author deliberately undertakes to prove all

Christendom the dupes of sweeping and long-sustained delusions. He

challenges scientists, theologians, philologists, anthropologists,

sociologists. But he proceeds upon methods the soundness of which no

evolutionist, at least, can question; and since he presents to his readers

all the testimony upon which his conclusions rest, it is not difficult to

check him as he goes on, and to ascertain how far, if at all, he is making

unwarrantable deductions. The volumes represent an immense amount of

labour and research. Mr. Massey has evidently sought conscientiously

to exhaust the field in regard to justification for his views. The

abundance of his evidence, indeed, will have the effect of delaying the

comprehension of his purpose, inasmuch as the ordinary reader will soon

become lost in the mass of detail, and, bewildered by this accumulation of

minute proofs, will fail to perceive the tendency, the sequence, and the

significance of the argument. To the non-evolutionist the work will

probably appear either unintelligible or wantonly wicked, since its

involves, among other results, the relegation of the whole system of

Christianity to the realm of mythology, the very historical existence of

its Founder being denied, and the not altogether novel theory of the

sun-myth being put forward as the origin of the alleged delusion upon

which the religion was based. Necessarily, however, this conclusion

is only reached after a long and elaborate study of the typology and

primitive language of early mankind. In these researches it must be

conceded that the author has sifted the best authorities; that he shows

familiarity with a wide range of scholarship; that he has not undertaken

to thrust upon the world an altogether crude theory, by straining,

distorting or mutilating the evidence used on its behalf. In fact he

has succeeded in bringing together a great number of illustrations whose

peculiarity is that they appear quite naturally, and because of inherent

accord, to fortify his conclusions. The worst that can be said of

any controversial work is that the theory was first invented, and that the

facts have been selected to fit the theory. Such a description ought

to be fatal to any work of the kind, if true. But Mr. Massey is not

open to that accusation, so far as we can perceive. He has

questioned facts to find out what they meant, and he has endeavoured to

put that meaning, as it appeared to him, plainly before his readers.

And certainly some of his suggestions are well calculated to approve

themselves to intelligent minds. The old notion that primitive man

began with monotheism and gradually declined into polytheism, is now

exploded. But there still survives a tendency to believe that

primitive man was a good deal of a philosopher, capable of somewhat subtle

reasoning upon physical phenomena, and possessing an imagination potent

enough to create for himself a complete mythology. Upon this subject

Mr. Massey argues forcibly. He says: "The world of sense was not a

world of symbol to the primitive or primeval man. He did not begin

as a Platonist. He was not the realizer of abstractions, a

personifier of ideas, a perceiver of the Infinite. In our gropings

after the beginnings we shall find the roots of religious doctrines and

dogmas with the common earth, or dirt even, still clinging to them,

and showing the ground in which they grew."

He deals boldly with the theory that the ancient mysteries

concealed subtle and mystic teachings and occult secrets. That

theory has of late been revised by some who desire to find new support for

belief in a modern adaptation of those mysteries. Mr. Massey,

however, does not hesitate to express the opinion that the reason why the

mysteries were so carefully concealed from the masses in later times was

"the simple physical nature of the beginnings out of which the more

abstract ideas had been gradually evolved." He holds, in fact, that

the Gnosis, the Kabalah, the esoteric evidence of all the so-called

mysteries, owe their origin to very simple and transparent physical

allegories. That, as he puts it, "the knowledge was concealed

because of its primitiveness, and not on account of its profundity."

Certainly some of the partial explanations which have come down to us of

the mysteries of Eleusis, seem to bear out this theory. The extent

to which symbolism has been employed, the natural progress made by it from

its beginnings in the crudity of gesture language to its tyrannical

sovereignty over partially civilized minds during long periods of time, is

exhibited in a suggestive way, and with the usual wealth of illustration.

Indeed, so far as the argument is concerned, Mr. Massey would, in our

judgment, have done better had he curtailed the illustrative portion of

his book considerably; and even now he may find it worth while to

popularize the work by making a condensed revision of it, in which only a

bare sufficiency of evidence need be given, and so as not to interrupt the

free and steady progress of the argument.

Patience and determination are required for the perusal of

such voluminous works, and the author evidently does not expect that his

book will achieve a large circulation. If, however, it is read by

the small minority of thinkers who, after all, give tone and tendency to

the intellectual progress of the age, his aim will have been attained; and

this limited range the work assuredly deserves. For it is an honest,

intelligent, painstaking effort to apply the evolutionary principle to the

beginnings of things, and to get at the real meaning of many mysteries by

ascertaining how the beliefs which men have held have grown naturally.

No doubt modern ethnology is very useful in this connection, for there is

no lack of examples of savage, barbarous, half-civilized, and peoples of

arrested development, to investigate. By the psychological growth of

the modern savage we can tell with almost certainty what was the

psychological growth of our ancestors, and of the ancestors of those

ancient peoples; the evidences of whose high culture have been preserved

so wonderfully in the Nile Valley. And inquiries from the beginnings

are becoming recognised as the only profitable ones. The school of

which Mr. Herbert Spencer is the acknowledged chief and guide has

proceeded mainly upon this method, though it has not always been true to

itself, because perhaps it could not at once liberate itself from the

influence of inherited and instilled fallacies. Mr. Massey has gone

further in this research than any of his predecessors. He is justly

entitled to claim, as he does in his preface, that his book is written "by

an Evolutionist for Evolutionists." Unhampered by educational bias

of any kind, he was enabled to start from a more advanced point than any

who preceded him, and as a result he has produced a work which must be

characterized as the boldest and most uncompromising outcome of the

evolutionary principle, carried out with an intrepid determination to

arrive at the truth concerning all the subjects of the inquiry. The

volumes are well printed, and are furnished with an index, which, however,

might well be enlarged for the better convenience of those to whom the

work is likely to become one of reference.—New York Tribune.

|

|

____________________

From

THE BUCKS ADVERTISER AND AYLESBURY NEWS.

MAY 22ND, 1886.

GERALD

MASSEY'S LECTURES.

_______

The eighth of Mr. Massey's ten lectures was given in St. George's Hall on

Sunday, and was on the "Logia or Sayings and Teachings assigned to Jesus."

The lecturer said the popular ignorance of the various origins of "History

Christianity" must be well-nigh invincible when a man like Professor Jowett

could say, as if with the voice of superstition in its dotage, "to us the

preaching of the Gospel is a new beginning, from which we date all things,

beyond which we neither desire, nor are able to inquire." Whereas we who

commence with our canonical Gospels—the latest of a hundred scriptures—are three

or four centuries too late for the beginnings. From the time of Irenaeus to that

of Mansell it had been taught that Gnosticism was a heresy and an apostacy from

the true faith originating in the second century, whereas the earliest

Christians known were Gnostics, although they did not accept Historic

Christianity. Essenes, Mandaites, Sethites, Elkesites, Nazarenes,

Docetæ, Simonians of Antioch, and others, were Gnostic Christians; some of whom

preceded, and all of whom opposed, the belief in a carnalised Christ. The

Gnostics, who were muzzled, and whose evidences were masked, constituted the

true connecting link betwixt Egypt end Rome. The Horus-Christ of Egypt was

continued as the Gnostic Christ called Horus. Other Gnostic types, probably

Egyptian, survived as Christian. It was Gnostic art that brought on the

types and symbols and portraits of the Horus-Christ, which are to be seen in the

Gnostic stories and in the catacombs of Rome. The Gnostic rituals repeat

the matter, names, and symbols found in some late chapters of the Egyptian Book

of the Dead. It was the Gnostic ante-Christ that became the haunting

anti-Christ of historic Christianity. According to the unquestioned

testimony of Papias, the primary nucleus of the canonical Gospels was not

biographical but a collection of sayings of the Lord (the Logia Kuriaka)

written down in Hebrew by one Matthew. The lecturer proposed to show that the

sayings referred to by Papias, together with the sayer and the scribe, were

originally Egyptian. The Ritual is partly composed of the sayings of Horus,

whose names signifies the Lord. One of these saying is "I have given food to the

hungry, drink to the thirsty, clothes to the naked, and a boat to the

shipwrecked," and as the speaker has done these things the judges say to him,

"Come, come, in peace," and he is welcomed to the great festival called "Come

thou to me." These sayings of Horus (literally, the Logia of the Lord) are

written down by Tehuti (Thoth or Hermes) the scribes of the Divine Words, who is

said to have the power of granting the Makheru to the solar god—that is

the gift of "speaking the truth" by means of the word, because he is the writer

of the sayings—the scribe of the wisdom uttered orally by the Lord; the means

therefore by which the word became truth to men. Now the special title of

this divine scribe in the character of registrar when he writes down the sayings

in the judgement hall (chapter 125) is Matin, which the lecturer claimed

to be the Egyptian original of "Matthew." Mr. Massey's next lecture will

be on the " Mystic Christology of Paul." |

|

____________________

From

THE BUCKS ADVERTISER AND AYLESBURY NEWS.

MAY 29TH, 1886.

GERALD

MASSEY'S LECTURES.

_______

The subject of Mr. Massey's ninth lecture in St. George's Hall on Sunday

was "The Mystery of the Apostle Paul, and the nature of his Christ."'

It was well known that there was an original and fundamental difference

between Paul and the three apostles, or "pillars," whom he saw in

Jerusalem. But the depth of that doctrinal difference had never yet

been fathomed, in consequence of false assumptions concerning the origin

of historic Christianity. Paul found that Peter, James, and John

were preaching another gospel than his, and setting forth another Jesus,

which he denounced and anathematised. We know what their gospel was,

because it has come down to us in the doctrines and dogmas of historic

Christianity. It was the gospel of the literalisers of mythology,

and the Christ made flesh to save mankind from an impossible Fall; the

gospel of a physical resurrection, and the immediate ending of the world.

These doctrines of delusion were repudiated and opposed by Paul. The

lecturer entered into immense detail in his analysis of the Epistles to

identify the Gnostic doctrines found there. Upon any theory of

interpretation two voices were to be heard contending for supremacy in

Paul's writing. They utter different doctrines; and this duplicity

of doctrine makes Paul, the one distinct and single-minded personality of

the New Testament, look like the most double-faced of men. These two

doctrine are those of the Gnostic Christ and the historic Jesus. The

lecturer contended that the true solution of this profound problem was to

be found in the fact that Paul did not set forth or celebrate any

historical Christ. He was a Gnostic, or, in Hebrew, a Kabalist.

He was an adept in the mysteries, a master of the gnosis, and one who

spoke wisdom amongst the perfected. According to Clement Alexander, when

Paul was going to Rome he stated that he would bring to the brethren, not

the true "Gospel history," but the gnosis or gnostic communication—the

tradition of the hidden mysteries "as the fullness of the blessing of

Christ," which, Clement says, were revealed by the Son of God—"the

teacher who trains the Gnostic by mysteries"—that is the mysteries of the

gnosis and of abnormal experience, such as that whereby Paul at first

received his personal revelation. A knowledge of the Gnostic

doctrines, which had been continued from Egypt, will alone explain the

true position of Paul. No Gnostic could admit that the Christ became

flesh, and Paul was a Gnostic. No Gnostic ever called the Christ

"Jesus of Nazareth;" neither does Paul. The Gnostic Christ had no

human genealogy and Paul likewise repudiates the genealogies amongst other

Jewish fables. Paul was the only apostle of the true Logos who was

recognised by Marcion, the rejector of historic Christianity. The

double dealing with us in the Epistles may be set down to the

interpolators of the writings after the death of Paul—the forgers whom be

had warned the Thessalonians against in his life-time. The supreme

feat performed by the secret managers in Rome was the conversion of Paul's

epistles into the chief support of historic Christianity by the

restoration of that "other Jesus," whom he had all along repudiated.

But there wait a great gulf for ever fixed between the Gnostic-Christology

and the historic Christianity, which has not yet been plumbed, or

bottomed, or filled in. It was bridged over, with Paul and Peter for

supports on either side—they who from the first had stood on two sides of

the chasm that could not be closed. The "Prædicatio Petri" declare