|

[Previous Page]

HUMAN NATURE

May, 1872.

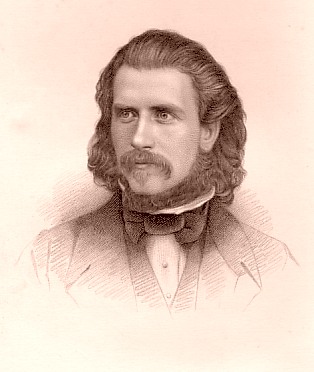

GERALD MASSEY'S LECTURES.

THIS favourite Poet of Progress is engaged by an

influential committee to give a series of lectures on Spiritualism, on

Sunday afternoons, in St. George's Hall, the particulars of which may be

found on a page in the advertising department. This step is one of

the most significant that has occurred in the history of Spiritualism, and

shows that literary men of the highest standing may identify themselves

with this movement without incurring social ruin. Any man of genius

and power may now become an advocate of Spiritualism with perfect safety

to his interests; for if popular opinion throw him off, spiritual opinion

is powerful enough to take him on. Since it was announced that Mr.

Massey would lecture in London as above stated, a number of other places

have caught up the idea, and flooded our table with inquiries as to

whether Mr. Massey would visit them on the same mission. We do not

take it upon ourselves to answer for Mr. Massey, but would recommend all

to write to him at Ward's Hurst, Hemel Hempstead, Herts. He is a

lecturer by profession; and for years has been notorious for his allusions

to Spiritualism in his public duties on the platform. We think there

is a grand field open for lecturers on the subject of Spiritualism, and it

would give us infinite pleasure to know that Gerald Massey had entered it.

As many of our readers as possible, both metropolitan and

provincial, should endeavour to be present at the lectures and promote

them as much as possible. It is usual for country people to visit

London to attend the May Meetings, and at this season the party of

progress have an excellent excuse to follow the usual custom, and

participate in Mr. Massey's lectures.

Ed.—this programme of

lectures was reported later in

The Medium & Daybreak. |

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

November 1, 1872.

MR. GERALD MASSEY IN THE NORTH.

We have received an advertisement bill from Bishop

Auckland, intimating that Mr. Massey will lecture in the Town Hall, on

Friday evening, November 8. Subject: "Facts of my own personal

experience narrated and discussed, together with various theories of the

alleged phenomena." The lecture to commence at eight o'clock.

Admission—front seats, 1s.; second, 6d.; gallery, 3d. We also learn,

from Mr. Wilson, that Mr. Massey is engaged to lecture at Halifax, on

December 18, 19, 20, and 21. This is a full course, and ought to be

imitated in other places of similar size. If well worked, the effort

would prove a great success. For the benefit of inquirers, we append

Mr. Massey's address —Ward's Hurst, Hemel Hempstead, Herts.

GERALD MASSEY'S LECTURES—"We

learn that Mr. Gerald Massey is engaged on a prose work, to bear some such

title as Myth, Mystery, and Miracle, a series or deep-sea soundings

in the abnormal domain of which Mr. Massey has had such a special

experience. Parts of his profoundly interesting subject will be

treated by Mr. Massey in a series of lectures, which he is preparing for

delivery in this country and the U.S. of America. Literary societies

that desire a preparatory specimen of the work cannot do better than

engage Mr. Massey to give them his curious and novel lecture on 'Sun and

Serpent Worship.'"—Newcastle Daily Chronicle. |

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

November 15, 1872.

MR. GERALD MASSEY IN THE NORTH.

Mr. Gerald Massey's visit to the county of Durham, to

lecture at Darlington, Bishop Auckland, and Barnard Castle, has given

great satisfaction in each of those towns, not merely to the

Spiritualists, who, we need not say, have had a rare treat, but to the

general public who patronised his lectures. The Darlington and

Stockton Times says:—

|

"One of the most intellectual,

and, I may say, influential gatherings that I have ever noticed of

the inhabitants or Darlington, assembled on Monday evening to listen

to Mr. Gerald Massey's lecture on Spiritualism. It was,

indeed, a strange story that Mr. Massey had to tell—how he was made

to believe in Spiritualism, almost in spite of himself. The

evidence was so strong, powerful, and multitudinous that Mr. Massey

could not resist it, he tells us. He tried to account for it

by every other means than that of the Spiritualist theory, but

failed. He was assured of the communication of the disembodied

spirits of his own relatives, and also others who had passed to the

other side. I heard one or two people say, however, that the

lectures were more for those who were to some extent acquainted with

Spiritualism than for the general public, though I defy any

intelligent man, be he Spiritualist or not, to listen to what was

said without having his attention arrested, and the spirit of

inquiry excited." |

On leaving Darlington, where Mr. Massey was the guest of one of the

leading gentlemen of the town, Mr. H. K. Spark, he proceeded to the

ancient town of Barnard Castle, where he gave the same two lectures as at

Darlington, and where he was most warmly welcomed by a small but

enthusiastic circle of friends, at the head of whom is Mr. Joseph Lee, who

was mainly instrumental in securing Mr. Massey's services for that place.

The lectures were delivered on Wednesday and Thursday evenings.

Great quakings, it is understood, were heard on the part of the orthodox

at this invasion of their very quiet little town, but nevertheless

curiosity and the energy of local friends secured a good house each

evening. The local scribe of the Northern Echo furnished some

account of these lectures to his employer, the Editor, who, it will be

remembered, made himself conspicuous by condemning Spiritualism while he

admitted the phenomena at the time of the late Conference. The

Northern Echo had a large heading over the article which dealt with

the lectures, entitled, " Gerald Massey interviewing the Ghost of Müller

the Murderer," and the article, we scarcely need say, was quite in keeping

with the heading, and ended with the remark, "Many things were propounded

difficult of apprehension, very strange to ears unused to them, and to

many minds revolting in their rank heterodoxy."

On Wednesday night Mr. Massey addressed a considerable

audience in the Music Hall. The subject advertised was, "The Man

Shakespeare;" but owing to some mischance Mr. Massey had not been informed

of the title, and hence was only prepared, as arranged with the other

placers on this tour, to give his course on the subject of Spiritualism.

However, with the approval of the audience, taken by vote, he delivered

his No. 2, or "The Spirit World revealed." The Subject was treated

in the lecturer's usual masterly style, and gave much satisfaction, save,

perhaps, to those whose religious prejudices influenced their reception of

the truth.

On Thursday the subject was on "The Facts of my own Personal

Experience." Much credit is due to Mr. Lee and Mr. Kepling, who so

energetically managed the arrangements of the Barnard-Castle lectures.

From Barnard Castle Mr. Massey journeyed to Bishop Auckland,

where our old friend Mr. N. Kilburn, jun., had made every arrangement for

his reception for a lecture on Friday evening (of which there is an

account appended). Mr. Massey again returned to Barnard Castle for

Sunday, and, on the evening of that day, delivered the third of his course

or lectures on Spiritualism, pertaining to the life and miracles of Jesus

Christ. This lecture was given in place of the usual discourse from

the pulpit of the Free Christian Church, of which Mr. Joseph Lee is the

pastor—a fact which reveals, both on the part of Mr. Lee and his

congregation, a freedom and liberality of thought rarely paralleled in the

churches of the present day.

GERALD MASSEY AT BISHOP

AUCKLAND.

On Friday night last, the 8th inst., Mr. Massey lectured in

the Town Hall to an audience of 300 people. The fact that such a

number of listeners could be brought together for a lecture will,

to those who know the town best, be the most convincing proof of the deep

interest taken in the subject of Spiritualism. Doubtless some few

who came out of curiosity rather than in search of knowledge found the

lecture technical, deep, and searching; but in Spiritualism, as in other

branches or knowledge, there is no royal road to learning; and on this

occasion the subject was being fundamentally expounded, rather than any

mere oratorical flights indulged in.

The lecture was in part an exhaustive reply to those who ask

for facts in connection with Spiritualism. Mr. Massey carefully

narrated, from notes taken at the time, the various experiences which

occurred in his own house through the mediumship of his Wife. From

these facts, most minutely analysed, no other possible conclusion could be

arrived at save that spirits who once lived on the earth could, and did,

under certain laws or conditions, communicate with us.

The so-called explanations of the phenomena, by psychic force

and unconscious cerebration, were thoroughly sifted without at all

damaging the spiritual theory. This portion or the lecture was

characterised by great depth of thought, and thoroughly taxed the mental

capacity of the audience.

The inestimable value of prayer, as a power on the

spirit-world, was pointed out in a graphic and touching manner; and its

use as a means of spiritual elevation, recalled from that sphere of

abstraction into which the creeds have banished it. Man is a denizen

of two worlds: in him meet and blend the spiritual and the natural; prayer

is the magnetic link between the two, and is therefore the special

attribute of all true Spiritualism.

Spiritualism claims to have substantiated and made real the

spirit-land, which is ever near. It teaches that our actions here

are the arbitrators of our position yonder, rather than any misty faith in

a wholesale salvation; and while it upholds the justice of God in the

punishment of all wrong-doing, condemns, with trumpet-tongue, the lying

farce of an eternal hell. Man, after death, will be his desires and

affections personified; therefore, set your affections on the highest

things.

God is really our father, not a chemical compound. Let

us draw near to him by communion with those departed ones whose exalted

position reveals to them more and more of his power and glory. In

our lives let us act so that no dear one may have to look back with sorrow

on us; rather may we be a strength and stay to both worlds. "Be not

afraid! eternally shall truth live on, whilst error shall shrivel up and

become as nothing."

We cannot attempt more than the briefest sketch of the

lecture, which was characterised by that wealth of thought and

illustration which is so profoundly exhibited in the author's works.

It is not to be anticipated, from the very nature of the subject, that all

present were satisfied or convinced; but certain it is that seeds of truth

were sown in many places, which after-time will abundantly reveal.

Mr. Massey deserves the lasting gratitude of all who love truth and

progress, for his courageous avowal of facts, the recital of which must

have cost him many a pang. We heartily wish him God-speed in his

labours.

N. K. J. |

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

November 22, 1872.

MR. GERALD MASSEY'S LECTURES.

We hear frequent echoes of the results of Mr. Massey's

lectures in the North. The newspapers have in general given full and

appreciative reports, and when falsehoods and bitter spite were vented by

obscure scribblers, such were themselves healthy signs of victory gained.

It is not alone the attendance at the lectures, nor the innumerable array

of good things said which form the excellency of Mr. Massey's services.

The lecturer's fame and personality are themselves a treasure, even if he

spoke not a word. Every person of culture knows who Gerald Massey

is—a man occupying the best-earned and one of the foremost places in

literature. This itself makes Mr. Massey's advocacy a telling

incident to thousands who do not go near the hall, and the newspaper

reports have given a very full expression to the fact.

Some gentlemen of Mr. Massey's position would be disposed to

please the popular demand by diluting the subject with that form of

thought which is already in good repute. To the lecturer's credit be

it said that this odious charge cannot be for a moment sustained, but

rather the contrary, as the following letter from Barnard Castle shows:—

|

On the 6th and 7th instant Mr. Gerald Massey

delivered two lectures, on Spiritualism to large and intelligent

audiences at Barnard Castle; the subject was handled in a masterly

style, orthodox theology was fought on its own ground, several

ministers were there to hear it, and such was the artillery brought

against the old creeds that the most independent thinkers declare

that its foundations are terribly shaken; raving priests and foaming

bigots raised such an uproar with the old cry, "the church is in

danger;" and an attempt was made to get Mr. Massey out of the town

before completing his engagement. This his friends would not

submit to, but the Free Christian Church was placed at his service,

and a large audience listened to him with great interest for one

hour and forty minutes. The subject was, "The Birth, Life, and

Death of Jesus," and again old orthodoxy fell in for a most fearful

lashing; he set forth Jesus as an ever-living and spiritual presence

which has given encouragement to free and independent thinkers.

A few séances have been held, and striking manifestations realised.

I would recommend all who wish to study this important subject to

listen to Mr. Massey's lecture on the person of Jesus from a new

standpoint. Yours faithfully,

J. L. |

A very certain corroboration of the above letter is found in a newspaper

report of the Congregational Anniversary at Barnard Castle. The Rev.

H. Kendall, of Darlington, spoke despairingly of the present state of

Church affairs. "As there are tides in the great ocean, so there are

tides of grace. The churches seemed to be in low water at present."

The speaker then ran aground on Spiritualism, a very dangerous now

continent, on the reef surrounding which a previous speaker had scraped

his keel. The reverend gentleman alluded to Mr. Massey as "a certain

individual who had been lecturing last week in Darlington and other places

on the subject, and he was amused at that gentleman's curious statements

and beliefs."

The opinion of Christians and theologians was given, viz.,

that the whole thing was due to the agency of his satanic, majesty.

A minister in Darlington, on Sunday last, said that nine-tenths of the

matter was humbug—the other tenth due to the devil. Modern

mediums—if living at the time of Moses, or in this country a century

ago—would have been put to death. He warned all Christians to have

nothing to do with the matter. The chairman characterised the

lectures on Spiritualism as a mingled mass of nonsense and heterodoxy.

The remarks of Mr. Kendall and the chairman were received with

enthusiastic applause, and showed what kind of an impression the lecturer

had made on a great number of his hearers.—Bishop Auckland Chronicle.

This is all very horrid, reverend brethren, and it must be a

source of great uneasiness to your charitable feelings that you do not

live "at the time of Moses," and have the glorious and god-like

satisfaction of putting the heretics to death. The nearest approach

you can come to it is to allude to the lecturer and not mention his name.

Our chief regret is that Mr. Massey's pressing engagements

previous to his departure for America will not permit of his doing much

more for our movement, and it is not at his request that we so urgently

beseech our friends to take all the work out of him they can. |

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

January 3, 1873.

GERALD MASSEY AT HALIFAX.

To the Editor.—Dear Sir,—During these last few days

there has been such a manifestation of profound intellectuality and

Spiritual erudition as has not been experienced in Halifax since Mrs.

Hardinge, with benedictions on her head, left us. There are those in

Halifax who are inexpressibly thankful to Gerald Massey for the rare, and

I may say wondrously unique treat which be has blessed them with; and the

writer of these lines is one amongst them. Mr. Massey's lectures are

the very paragon of excellence, because of the rich vein of thought which

runs through them—because of the great, yea stupendous, erudition evinced

in them, and because of the beautiful and exquisite diction with which

such thoughts and erudition are clothed. I am sorry to say, sir,

that the audiences were very meagre; yet it is somewhat gratifying to

record that the few who heard the lectures listened with rapt, attention,

so much so that it reminded one of that passage in Lord Lytton's play of

the "Lady of Lyons" where Pauline is made to say to her lover Claude, "As

the bee hangeth on the honey, so hangeth my soul on the eloquence of thy

tongue." Mr. Massey's first lecture, on "The Man Shakspeare," was a

production of a very high order. It was studded with beautiful gems,

such as delight and gladden the refined soul. The characteristics of

Shakspeare were exhibited in a manner which will not be forgotten by those

who heard the second lecture, which descanted upon the Spiritualism of all

ages, brought truth to view, which, to many, was hid in a heap of

mythology; ancient faiths and reputed legends were analysed from the

débris of myth and crude fancy, and some spiritual truths were culled.

The third lecture, which was on his own personal experience

in connection with Spiritualism, was listened to with mingled feelings of

amazement, awe, half incredulity, and yet, withal, with deep and riveted

attention. The statements were so forcibly put as to leave no room

for criticism or cavil. Every loophole by which the prejudiced

usually creep out in order to evade the logical conclusion which such

facts necessarily involve was effectually stopped up, as it were, to

prevent their wonted egress. Mr. Massey showed incontrovertibly that

departed spirits must be the chief agents in producing the phenomena he

had described.

There was a somewhat larger attendance on Sunday to hear the

lecture on "Jesus Christ." This lecture evinced the same

characteristics as the other—full of beautiful, humane touches—redolent or

appropriate repartee and satire, which cleaved deep through the fabled

dogmas of orthodoxy, and made an awful wreck of them. The true life

or Jesus , was exhibited in all its pristine beauty—minus the artificial

colouring which theologians have bedaubed it with. His miracles,

from his conception to his death, were considered in the light of

spiritual science; and it was shown that they were not accomplished in

virtue of suspended law, but in accordance with laws of nature, physical

and super-physical; or, as some would term it, material and spiritual.

In the evening of the same day Mr. Johnson, of Hyde, spoke in

the trance, and touched upon various themes in connection with the

philosophy of Spiritualism; but, having to go out on business, I cannot

say anything about it, save that the chairman did a little bit of

exorcising. I am told that he interrupted the spirit, and contended

that it was not speaking to profit. Judging from Mr. Johnson's

previous addresses in the trance, which I thought were of a high nature, I

fancy this interruption would be uncalled for; and I am strengthened in

this belief by the fact that two prominent Spiritualists in the body of

the hall protested against it, and contended that there were no signs of

disapprobation in the audience. Be that as it may, I myself demur

to, yea, detest, interferences of this kind. I say, let spirits have

their opinion as well as mortals. Apologising for my imperfect

communication, I am, yours in haste,

A. D. WILSON.

P.S.—Probably there are three causes which militated against

the success of these lectures. In the first place, the weather was

very unfavourable; in the second place, it is too near Christmas; in the

third place, there is disruption amongst the Spiritualists here. I

regret to say that many Spiritualists who were not interested in Mr.

Massey's coming amongst us ill-naturedly kept away, and even on the Sunday

got up an opposition meeting—a mode of proceeding, to say the least of it,

exceedingly disrespectful to Gerald Massey, not to mention bad manners in

other respects. I sincerely trust that Dr. Sexton's lectures, which

are got up under different auspices, will be attended by all

Spiritualists. Let all help, while differing in minor things, to

spread the cause which we all have at heart.

A. D. W.

13, Baker Street, Pellon Lane, Halifax. December 22nd.

[We rejoice at the sentiments conveyed in these last words.

Spiritualism does not seem to have taught these "ill-mannered" parties any

thing better than a childish retaliation. We hope the committee thus

aggrieved will pay back in good deeds, and do all they can to promote any

action for the good of Spiritualism, though it should be "got up under

different auspices."—ED. M.] |

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

January 31, 1873.

GERALD MASSEY'S LECTURES IN THE NORTH

AND THE PROGRESS OF SPIRITUALISM.

On Monday of last week Mr. Massey lectured in

Middlesborough for the Philosophical Society, the Mayor, R. Stephenson,

Esq., in the chair. There was a pretty large audience, and the

remarks of the lecturer were received with repeated salvos of applause.

The Gazette says:—"No one who listened to Mr. Massey could doubt

the honesty of his belief, and his lecture, which forms only a part or a

book he has in preparation on the subject, was adorned by a wealth of

allusion and illustration which imparted a charm quite, independent or the

particular line of thought which characterised it." Besides a

copious report of the lecture, the same paper devotes a leader to the

subject, in which Spiritualism is treated in a remarkably fair and cordial

manner. It is reported that the Swedenborgians are arranging for a

lecturer to visit Middlesborough as an offset to Mr. Massey's teachings.

The editor of the Gazette cannot understand such conduct, seeing

that Mr. Massey claims Swedenborg as one of the greatest Spiritualists or

all time. The editor appropriately remarks:—"The discussion thus

raised should contribute to the public enlightenment on a subject, to say

the least, very perplexing to the uninitiated. The proposed lecture

is only one indication of the peculiar interest which Mr. Massey's visit

to Middlesborough has awakened."

On Tuesday evening Mr. Massey lectured in the Mechanics'

Hall, Newcastle, E. Procter, Esq., in the chair. The lecture is very

fully and intelligently reported in the local Chronicle. Mr.

Massey's second lecture was very much better attended than the first.

It was on Mr. Massey's personal experiences. Mr. Councillor Barkas

presided, and admitted the existence of some invisible power. Mr.

Massey was listened to attentively, and frequently applauded. At the

close there was discussion and questions asked, which passed off

pleasantly, notwithstanding the efforts of several persons to raise

difficulties and misunderstandings. These lectures have produced a

very marked impression in the north of England. |

|

_____________________

CHICAGO DAILY TRIBUNE

December 10, 1873.

CHARLES LAMB.

_______

Lecture by Gerald Massey at the Kingsbury Music Hall.

Gerald Massey, the English poet, lectured last evening at the

Music Hall in the Star Course, to a house miserably disproportionate to

the fame of the lecturer and the amount of advertising done by his agents

in this city. It may have been the opera, or it may have been something

else that left the auditorium about two thirds empty. The larger part of

the audience being chairs, it is not surprising that there was but little

applause. In fact, the audience was rather cold. It did not applaud any of

the effects of the Star orchestra, and waited in mute astonishment, until

Mr. Gerald Massey stole quietly in at a side door of the stage, and

hurried to his stand, without making a bow, and without introduction. He

suddenly opened his manuscript, and began reading with considerable

nervous hurriedness. Mr. Massey is not handsome, nor is he in appearance

intellectual. His moustache and side whiskers are thin, and his hair is

parted in the middle.

The lecture began with a definition of the two qualities of wit and

humour, somewhat after the fashion we have generally heard, Mr. Massey

speaking, however, with such rapidity that the force of his illustration

was lost be the effort to crowd too much into a short space of time. The

illustrations were always bright and original, and occasionally brilliant.

The subject of the lecture was "Charles Lamb," and the introductory

remarks were admirable suited to the body of the discourse, inasmuch as in

Charles Lamb, according to Mr. Massey, wit and humour were inextricably

blended. Passing from these remarks, he gave a short sketch of Lamb's life

from his entering Christ's Hospital, where he first made the acquaintance

of Coleridge. He referred to the taint of hereditary insanity in both

Charles Lamb and his sister Mary, treating the subject very closely, and

with strong pathetic description. There were, he said, various kinds of

madness, one kind, such as that which affected these poor creatures, which

was a sort of disorganised somnambulism. Mary Lamb, her brother wrote, was

during periods of insanity, far more brilliant in conversation than any of

his wittiest friends. To the protection and preservation of this sister

Lamb devoted his whole life, giving up for this purpose his love's young

dream, the memory of that Alice to whom he refers occasionally in his

writings. And it was this devotion to his sister, of the grandeur and

heroism of which lamb appeared to be quite unconscious, that the lecturer

said he wished his hearers to think. Lamb used to kick against the

drudgery of his work at the East India House, but it was the very best

thing for him. To be taken out of himself by force for six hours a day, at

a good salary, was a godsend to Lamb, and a blessing to us. It had given

us all the best of Charles Lamb in the smallest possible space, four

pocket volumes containing all his contributions to literature. And if he

could write all he had to, in four volumes, how much better for him that

he did not dilute them into twenty-four.

Lamb was a creature of London, the roots of his nature clung to the bricks

of that old Babylon; he never breathed freely, save in its limits; was

never at home elsewhere. Whenever he was in the country, he walked out of

it as fast as possible. He never liked it, except at one time, and that

was when he was in love, and then, like all lovers, he had a sympathetic

longing for all green things. The fact that lamb's love of the country (in

poetry) survived fresh and green in the heart of the great city, was

curious in a literary point of view, as curious, he thought to men of

letters, as the discovery by small boys, that mustard and cress would grow

upon wet flannel, without taking root in the earth at all.

In describing the appearance of Charles Lamb, Mr. Massey declared that the

subject of his discourse was not formed according to the conventional idea

of a great man, against which popular fallacy he (the speaker) felt

himself to be a standing protest. Charles lamb was not much of a teacher,

but he was one of the best good fellows and humorists the world had ever

seen, and he left us in his writings, and inexhaustible supply of

amusement and keen delicate fun.

The lecture was made up, in the great part, of extracts from lamb's works,

chosen with admirable taste, as illustrative of the character and

personality of the man whose genial, simple, nature he was discussing, and

anecdotes were given, especially towards the end of the lecture, which

were listened to with warm appreciation and marked attention on the part

of the audience.

Mr. Massey possesses considerable initiative, ability and versatility of

expression. He was guilty of an occasional omission of the aspirate and

said "unctious" for "unctuous" twice. His delivery is very rapid, puzzling

to an audience for some time but agreeable after a little. His

spiritualistic leanings were expressed in an occasional remark dropped

half unconsciously.

|

|

_____________________

BANNER OF LIGHT

11th Oct., 1873.

Arrival of Gerald Massey.

It will be seen by the following announcement that Gerald

Massey, distinguished as a poet and man of letters, and a Spiritualist

withal, was among the recent arrivals at New York. He is engaged

as a lecturer in several of the winter courses, and we hope that our

friends will see that he is well cared for.

Gerald Massey, the English poet who has just just arrived in

this country, was born in May, 1828, and is therefore forty-five.

He was the son of a poor canal boatman, and after hard toil in a

silk-mill as a boy tender, at fifteen went to London and found work as

an errand boy. His is another example of the power of genius to

make itself known despite all repression of circumstance. He has

published some five volumes of poetry--"Poems and Chansons," "The Ballad

of Babe Christabel, and other Lyric Poems," "Craigcrook Castle," and,

latest of all, "A Tale of Eternity, and Other Poems." The latter

is a ghostly and strange work. Massey's strength has been in his

lyrics, which have won for him the admiration of the English common

folk.

|

|

_____________________

BANNER OF LIGHT

11th Oct., 1873.

Gerald Massey.

Now in this country on a lecturing tour, delivered recently

in London a very successful series of lectures on Spiritualism [Ed.—probably

the series in Langham Place].

He is the author of a little volume, bearing the title "Concerning

Spiritualism," in which, assuming the facts as proven, he deals chiefly

with the philosophy of the subject. The following passages in

reference to the Darwinian system, &c., will be read with interest:

"Spiritualism will accept evolution, and carry it out and

make both ends meet in the perfect circle; with it is the nexus,

not on the physical side of the phenomena; without it the doctrine of

Mr. Darwin is but a broken link. Complete evolution is the

ever-unfolding of the all-present, all-permeating creative energy

working through all forces and forms."

"Mr. Darwin, as much as any theologian, when he does

allude to the Creator, appears to look upon him as operating ab extra,

and working from without; a mind dwelling apart from matter and

ordaining results which are executed unconsciously in his absence;

whereas the Spiritualist apprehends him as the innermost Soul of all

existence, the living Will, the spiritual involution that makes

the physical evlution—the immediate and personal Causation of

dynamic force, no matter by what swift transmutations—the creative

Energy in presence penetrating every point of space at each moment of

time, effectuating His intentions, and fulfilling His creative being.

"Spiritualism will also destroy that belief in the eternity

of punishment, which has, for many mourning souls, filled the whole

universe with the horror of blackness, and made God a darkness visible.

'Ah,' said the dear cheery Old Calvinist, 'these people—the

Spiritualists—'believe in a final restitution and the saving of all,

but we hope for better things.' Many good people will cry out

in an agony of earnestness, as Charles Lamb stammered in his fun, 'But

this is doing away with the Devil; don't deprive me of my Devil.'

"Spiritualism must not destroy the dogma that God has but one

method of communicating his love to men, and but one doorway way through

he draws them into his presence. I tell you the God of heaven

bends and broods as lovingly, as divinely, and with a balm as blessed,

in the dear, appealing, winsome face of my little child, as He can do in

face of Christ."

We needn't say more to show that Mr. Massey's little tract on

Spiritualism is worth reading; but it will require close attention and

study in the reading, for he enters into some of the profoundest of

questions of life and creation. |

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

December 19, 1873.

GERALD MASSEY IN AMERICA.

Gerald Massey, to quote the Daily Graphic, is no

longer the "Coming Man," for the excellent reason that he has come.

He has spoken twice, once in Unity Chapel, Harlem, on Sunday, October

26th, to a crowded, intellectual, and enthusiastic audience. His

subject was based on the Man Friday's question to Robinson Crusoe, "Why

does not God Kill the Devil?" Under the head of a "Poet Preacher,"

the Graphic says:

|

"The lecture was scholarly, pictorial, glowing, and

at times really eloquent. The first part was rather overladen with

myth lore for popular effect, but the body of it was practical

enough for anybody. Mr. Massey's voice was slightly husky, but not

unpleasant. He speaks with great rapidity and nervous energy, and

with an earnestness which communicates something of its own glow and

fervor to his auditors. He makes no attempt at oratory; he is too

much in earnest for that, and perhaps will be all the more effective

and successful because of his simple, down-right sincerity and

directness in presenting his convictions." |

The World has a full and fair report of the lecture. The

Herald intimated that it would take a full page to do justice to its

profoundity, and that it was too compactly welded to deal with piece-meal.

The Tribune also rendered a very favourable account. This

paper had put in a claim for Mr. Massey to be heard for himself, even when

his subject might not seem attractive from the title. It wrote, when

Mr. Massey first arrived in America:

|

"Mr. Massey comes to us to lecture

upon literary subjects. and brings with him a reputation as a

lecturer not second to his poetical fame. In a truer sense

than any English writer, he may be called the poet of the poor.

But his early association with labouring people did not prevent him

from becoming an unusually cultivated and ingenious scholar.

He has made the most subtle and curious study of the character of

Shakespeare, as shown in his writings, which has yet been put forth.

He is at present engaged on a work requiring enormous research and

acumen—an investigation of the history of myths and the origin of

language. In the meantime, we do not doubt that the thousands

who have read and enjoyed his pure and earnest verse, will be glad

to see and hear him on the platform." |

On Monday Evening, October 27th, Mr. Massey lectured in Association Hall

to an audience which, when the state of the weather and the financial

state are considered, was impressively good. We again quote the

Graphic.

|

"Mr. Gerald Massey made his bow as

a lecturer to a New York audience at Association Hall last night his

theme being, "A Spirit World Revealed to the Natural World."

There was a large and intelligent audience present. Mr.

Massey's manners as a lecturer are pleasing, and the theme is one

exceedingly provocative of thought. The literary merits of Mr.

Massey's lectures are of the highest possible order. He has

won the warmest regard of all who think well of their kind by the

feeling he has expressed for the poor of his own and every country.

There ought to be enough of interest in him and his subject to bring

him large audiences in every city of the Union." |

Theodore Tilton, in the Golden Age, characterises Gerald Massey as

|

"A genial, modest gentleman; full

of bright thoughts and fancies earnest and sincere in his

convictions; enthusiastic in his temperament, and altogether an

agreeable and attractive friend. His lectures will not begin

for a week or two, and during the interval he is devoting himself to

seeing what he can of our people, and interchanging views on

subjects in which he is interested. One of these is

Spiritualism—not its vagaries and follies, but its philosophy and

facts. Another is the labour question, in which his whole

heart is interested on the side of the working classes.

Another is Shakespearean literature, or which he is a diligent

student, and to which he has contributed a stately volume called

"The Secret Drama of Shakespeare's Sonnets Unfolded." |

As a lecturer, he depicts Mr. Massey as "original in thought, rapid,

ardent, and glowing in expression, and honest as the day is long."

The Evening Mail predicts that Mr. Massey will receive a warm

welcome from all classes of our people.

|

"He has won at once the cordial

will of those who have had the pleasure of making his acquaintance.

Those who have admired his genius—and they are a countless host—will

not fail to appreciate his modesty, his quiet earnestness, and his

unaffected devotion to what he believes to be the truth." |

Mr. Massey's literary lectures—such as those on the more familiar subjects

of "Lamb," "Hood," the "Man Shakespeare," and the "Story of the English

Pre-Raphaelites"—will attract, entertain, and charm our people. And

these are kept quite distinct from his other utterances, which are

reserved for those who desire to hear them, and are not thrust on those

who do not. The Sun called Mr. Massey's first lecture—

"Spiritualism handled so that Spiritualists did not

understand it."

This was a compliment, however unintentional. They are

immensely mistaken who assume that Mr. Massey has come to America to talk

over the trivialities of table-tipping. He has explained in the

Golden Age that, by means of a very peculiar experience, he has struck

on a lost track of ancient knowledge. The first fruits of this are

offered in a few of his lectures. But the fuller unfolding will take

one or two large volumes. There can be no doubt that Mr. Massey has

most personal affection for the less popular of his subjects, or he would

hardly have run the risk of offering these to audiences in Now York

against the advice of the Bureau and his more worldly-wise friends; it is

because he feels that he has something new to say, and he thought this

country the right place to say it. He proclaimed on Monday night

that Spiritualism, as he understood it and had wrought it out, was a New

World's gift that amply repaid all America had ever received from the old

world, and concluded his peroration with these words:—

|

"It may be the dream was true; it may be flint I saw

with visionary eyes. But as I strained them across the Atlantic long

before I came, I saw your young world of the West arise and brighten

with this new life quickening at the heart of her, this new dawn

kindling in her face, throbbing and radiating with auroral splendour

of this latest light, as if the millenium morning of humanity's most

golden future had touched her forehead first, and she shone

illumined, glorified and glorifying, as if in the very smile of

God." |

|

|

_____________________

THE SPIRITUALIST.

February 13, 1874.

MR. MASSEY IN AMERICA.

On more than one occasion Mr. Gerald Massey's lectures in the United

States have been too unorthodox for the listeners. The executive

committee of the Chicago Philosophical Society recently replied as follows

to a protest from the trustees of the Chicago Methodist Church, who had

let their building to the society for the delivery of one of Mr. Massey's

lectures:—"We fully recognise not only your right, but your duty, to

protest, against any improper use of the church property held by you its

trustees, and we are free to admit, in the case of Gerald Massey's

lecture, we did not use our usual caution in ascertaining the character of

it; and are equally free to say that, had we been aware of its character,

we should have declined it."

On the 17th of last mouth, at a dinner which took place in

Boston in connection with the Franklin Typographical Society, Mr. Massey

said:—

|

"I am pleased that the first public social reception

given to me in Boston should have come from the working-men. I

was born among the workers, and to them I belong. At the

present time I am associated with a subject that is tabooed and

unfashionable—so much so that only a single preliminary word of

welcome was given to me by the Boston press. It has always

been my fate to stand on the weaker and unpopular side, and it is so

still. But, gentlemen, I can assure you it was the side that

came uppermost, and was the stronger in the end, and I do not doubt

it will be so with this much despised subject of Spiritualism.

I carry with me from England letters of introduction from some of

our foremost people to some of your most honourable citizens.

But, as fate would have it, none but the despised Spiritualists

invited me to lecture in Boston, and with them have I cast in my

lot. In this connection too, it is pleasant to reflect that

all the private hospitality extended to me in America has been in

the homes of the Spiritualists." |

|

|

_____________________

BANNER OF LIGHT

28th May, 1874.

GERALD MASSEY'S

WORK IN SAN FRANSISCO.

The News Letter, a literary journal of high

merit and popular standing, which is published in the above-named city,

thus kindly treats in brief—in its issue of April 18th—of the past life-labors

in England, and present especial results in the Golden State by this

gifted poet and earnest orator, who on Sunday, May 10th, took leave of

the Boston friends at Music Hall preparatory to his homeward voyage

across the Atlantic. To the views expressed by our contemporary of

the Pacific slope concerning Mr. Massey, we desire to say, Amen!

"A thoughtful, earnest and original spirit has come amongst

us and in the brief space of a week, has created almost a revolution in

the domain of intellect, and set those thinking who rarely thought

before. Gerald Massey, until of late years, has been known to the

world as a writer of impassioned verse, some of the love strains of

which are destined to live as long as our mother tongue shall last, but

recently the poetical faculty seems to have given place to the more

generally one of the public teacher, and the latter triumphs of our

friend have been won upon the lecturer's platform. Born with

somewhat unfavorable conditions for the fostering of the more gentle

qualities of our nature, it was somewhat surprising to find a boy of

eighteen or nineteen dashing with such charming rhymes as those

well-known love-lyrics of his, beginning

'No jewelled beauty is my love,'

And,

'Heaven hath its crown of stars.'

The former of which has found has found its way into every

selection of poetical beauties which in late years has issued from the

press. Sprung from among the people, his association has always

been with them, and sympathy for their sorrows and advocacy of their

rights have ever enveloped his life, and borne him onward upon the

stream which carries the old prejudices of the past toward the great

ocean of oblivion. A deep and inquiring thinker, he has shaken off

the trammels of sectarianism and boldly dared to think for himself on

all matters most intimately concerning his own moral and spiritual

nature. The conclusions to which he has come upon religious

subjects are such as would startle the class of minds accustomed to

regard them through the spectacles of their ancestors; but placed as

they are before his audience in terse and vigorous language, and with an

earnestness which is the fullest proof that they are the purest

convictions of their author's mind, they tell the listener that there is

much room for doubt as to many of his cherished theories, and send him

seeking into new paths for treasures of truth which may lie there, to

him as yet unknown. Mr. Massey's subjects are various and widely

separated, and touch the very opposites of mental thought. Poetry,

science and drama, the ancient myths, modern religious creeds, wit and

humor, and the teachings of Spiritualism, are all treated by him in

their fullest measure, and receive the advantage of candid and impartial

research. The visit of this remarkable man to this city has been

unfortunately too brief, and only three of his many topics have received

illustration before a San Francisco audience. The first of these,

'The Man Shakspeare,' was a careful epitome of the author's more

extended analysis of the sonnets and a pleasant inlook upon the private

life of the grand poet of the world. It was full of gems of

masterly English, and when published, as it doubtless will be, will

serve as a text upon the phases of Shakspeare's life and character of

which it professes to treat [Ed.—see 'The

Secret Drama of Shakspeare's Sonnets']. 'Why does not God

kill the Devil?' is a startling title, and the interest in the subject

displayed by a very numerous audience showed how attractive was the

lecture in which the question was to be answered. In this Mr.

Massey scattered to the winds the trumpery doctrine of a personal fiend,

and showed that God did not kill the devil because there was no devil to

kill. Bold and perfectly outspoken, he cares not to shelter

himself behind glittering flowers of rhetoric, but without a fear dashes

into the midst of what be believes to be error, and does his best to

vanquish it. His third lecture, on 'The

Coming Religion,' we could not hear, but we are willing to believe

that it was marked by all the originality and breadth of thought which

distinguished his previous efforts. It is a matter of regret that

we should have seen so little of Mr. Massey, and that his many calls

among the cities of the Eastern States forbid the prolongation of his

stay. He may, however, be assured that such is the impression he

leaves upon the minds of his hearers, that his second visit to the

Pacific Coast will be hailed with delight by a large number of the most

thoughtful minds among us, and that a warm welcome will be extended to

him when he again bends his steps hitherward. In the hope that we

may soon witness his return, we for a time regretfully bid him

farewell!"

|

|

_____________________

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

July 31, 1874.

GERALD MASSEY'S LIST OF LECTURES FOR 1874—5.

Mr. Massey has issued the following list of subjects

for the ensuing season. We hope Mr. Massey will be extensively

engaged. The plan which we recently recommended for the introduction

of lectures on Spiritualism into the arrangement of Mechanics'

Institutions, might be adopted in respect to Mr. Massey. Special

efforts should be made to secure a visit from Mr. Massey in every place

where lectures can be got up. His lectures are of the highest class,

fearless and logical, and carry conviction with a class of minds which are

repelled by the performances of those where genius is not so sparkling.

The recent triumphant tour in America will re-introduce Mr. Massey to the

English public with renewed zest. The list of subjects offered is as

follows:—

-

Charles Lamb,

the Most Unique of English Humourists.

-

A Plea for

Reality; or the Story of the English Pre-Raphaelites.

-

Why I am a

Spiritualist.

-

A

Spirit-World Revealed to the Natural World from the Earliest Times by

Means of Objective Manifestations, the Only Basis of Man's Immortality.

-

The Life,

Character, and Genius of Thomas Hood.

-

Why Does Not

God Kill the Devil? Man Friday's Robinson Crucial Question.

-

The Man

Shakespeare, with Something New.

-

The Birth,

Life, Miracles, and Character of Jesus Christ, Reviewed from a fresh

Standpoint.

-

Robert Burns.

-

The Meaning

of the Serpent Symbol.

-

Old England's

Sea Kings.

-

The Coming

Religion.

Address—Ward's Hurst, Hemel Hempstead, Herts.

|

|

_____________________

ST. LOUIS GLOBE DEMOCRAT

Oct. 21, 1875.

GERALD MASSEY INSANE

The Weaver-Boy Poet in a Lunatic

Asylum.

(From the New York Mercury.)

[Editorial note: "If you don't read newspapers

you're uninformed. If you do read newspapers you're misinformed." (Mark

Twain) . . . . errors, omissions and

exaggerations in newspaper articles are, and always have been,

commonplace. Thus, when used as primary evidence, such material should be

treated with caution. This article is no exception to that rule.

During the Autumn of 1875, several U.S. newspapers

carried brief statements—probably re-postings, as is this article—that

Massey had been confined to an asylum. However, there is no corroborating

evidence that this was ever the case. It is perhaps coincidental that Massey's

first wife, Rosina Jane, throughout her married life suffered from an increasingly serious

psychological disorder worsened by alcoholism.

Thomas Cooper, writing to a friend in

1861, had this to say of Rosina

".....I wonder that poor Gerald Massey parades the figure of the

drunken plague to whom he has so sillily tied himself."—he

had little choice; he couldn't leave Rosina on her own.

Towards the end of her life, Massey was encouraged

strongly to place his wife in an asylum; this he resisted. Rosina was to

die suddenly, of no definite cause, some nine years before the date of

this article, so it is possible that we have here a garbled version of

that story, which Massey often related in his lectures on spiritualism

(e.g. see the report....

Conviction and Conversion). That said, this article's author

(anon) paints an interesting picture of Rosina, of whom we have little

detailed information, and of Massey's early years on the lecture

circuit. There can be no doubt that Rosina greatly influenced

Massey's life—not, for the most part, beneficially—sparking off an

interest in Spiritualism that was to absorb much of his later years and

give him a living on the lecture circuit, both at home and abroad, long

after this piece was written.

(Incidentally, the Lancashire poet

Samuel Bamford might have owned up to the epithet

'Weaver-Boy Poet', but Massey? Definitely not!)]

________

Tidings have reached this city from private sources in England that the

well-known poet and lecturer, Gerald Massey, is suffering from aberration

of mind, and has been placed in a private asylum. To those that have

been at all familiar with the career of the gifted and unfortunate poet,

this sad news will not occasion unmixed surprise. In his marriage,

infelicitous as Byron, he has been literally chained to a woman who was at

once an Amazon, a Medea and a Venus.

The writer became acquainted with Mr. Massey in the winter of

1854-55 in Newcastle-on-Tyne, England. Gerald was then a young man

of twenty-six engaged on a lecturing tour. For three nights he

lectured before the Literary and Philosophical Society of that town, his

terms being ten pounds sterling per night. His success was immense.

Lord Ravensworth was the chairman of his second lecture, and the poet was

for a couple of days his lordship's guest at Ravensworth Castle. At

every town he visited on that tour he was the guest of the aristocracy,

and though this distinction did not turn his head or make him arrogant,

there was no disguising the fact that he became in the slightest degree

snobbish. While engaged in lecturing, he was also a regular

contributor to the columns of the Athenaeum. Consequently his

worldly circumstances were easy, and he was a jolly but temperate

companion. He talked much of his home, his baby, his Newfoundland

dog, Carlo, and his "beautiful, beautiful wife;" and he used to say that

the money he made by his lectures very inadequately repaid him for the

home happiness he was deprived of during his tour. He abhorred

tobacco, and repeatedly said he could not understand how a man of culture

and refinement could introduce the "beastly ador of tobacco into his

home."

Everything was lovely with Gerald in those days. The

writer was over half a dozen years his junior, and caught some of the

poet's enthusiasm while listening to his fervid eloquence. Let me

describe him as he then appeared: A very little man, with a shock of sandy

hair combed straight back, without parting, from the forehead; underneath

a pale, careworn face; moustache lighter than the hair; a scrambling

goatee; large, luminous iron-gray eyes, an upper lip too large for his

face, and a painful lack of character about the lines of the mouth.

His hands were as white as those of a hospital patient, and though they

were small, the fingers had not that tapering form or delicate tip which

are accustomed to associate with the artistic or poetic mind. He had

then written a few poems, one of which was published in the Edinburgh

Witness, while the celebrated geologist, Hugh Miller, was its editor. But that was before poor Gerald was

married; or, to adhere strictly to the facts, in the year 1848.

Alas! the year after he was married to his queenly-looking Dulcinea; and

as she said herself, "Massey's impassioned poetry won me." We have

no room to print the entire poem of "Unbeloved,"

which won Gerald's wife, but this notice of the man's life would be

incomplete without the first verse, which paints his hopeless passion at

the time he was courting the beautiful Mabel:

|

LIKE a

tree beside the river

Of her life that runs from me,

Do I lean me, murmuring ever

My fond love's idolatry:

And I reach out hands of blessing,

And I stretch out hands of prayer,

And with passionate caressing,

Waste my life upon the air.

In my ears the Syren river

Sings, and smiles up in my face;

But for ever and for ever

Runs from my embrace. |

Mr. Massey was then living in an elegantly-appointed house in

Portobello, a couple of miles from Edinburgh. The writer visited him

there in the summer of 1853. It was impossible to escape the

conviction that the poet was then "overshadowed" and hen-pecked by his

wife. She had a grand presence, large jet-like black eyes, a hard

mouth, fine teeth, and a form that a sculptor would love to model.

After luncheon, Gerald and I took a walk round Arthur's Seat, and he

commented enthusiastically, as was his want, on the physical and

picturesque contours of the Newhaven fishwomen returning home [to]

Edinburgh. As I left him for the night he said, while clasping my

hand with both of his, "My boy you must get married; see how happy I am!"

Two years elapsed, and I heard little of Massey. But

when the winter came I was surprised to see a "poster" in the market-place

at South Shields, announcing that "Gerald Massey, the poet, would deliver

three lectures in the Central Hall, Chapter Row." I attended the

first lecture. Its subject was "Hood, and Wit and Humor."

[ED.—see also Massey's essays, "Thomas

Hood, Poet and Punster" (1855) and "Life

and Writings of Thomas Hood" (1863)].

I occupied a back seat, yet I could distinctly perceive that

the poet's face was more haggard and careworn than when I last saw him.

There was probably a majority of ladies in the fashionable audience, and

the lecture proceeded with that rippling eloquence of which Massey was

such a master. His voice—always full, musical and mellow—had lost

none of its resonance, and his hearers were alternately dissolved in tears

or shaking with laughter. Tender glances from bright eyes were

thrown upon him, and before he had progressed half and hour it required no

particularly acute observer to discover that half of the young ladies in

the hall adored him. When he began to recite the "Bridge

of Sighs" you could have heard a pin drop, and as he, with touching

pathos and lingering sadness, repeated the lines:

|

Cross her hands humbly,

As if praying dumbly,

Over her breast!

Owning her weakness,

Her evil behaviour,

And leaving, with meekness,

Her sins to her Saviour! |

there was not a dry female eye in the assemblage.

I saw Mrs. Massey gaze round with astonishment. She saw

that the little man was the idol of the hour—that tears were flowing from

aristocratic cheeks; that beautiful young hearts responded to the touch of

nature which makes the whole world kin. The sight was too much for

her nature. With a wild, shrill shriek, she apparently fainted away.

Poor Gerald advanced to the edge of the platform pale with anger and half

unnerved. Four men hoist the woman and bear her from the place, two

matronly women attend and apply restoratives, tidings pass round the hall

that the fainting woman is the lecturer's wife, and that she is jealous of

him, and after a while the lecture proceeds undisturbed.

At the next lecture I went as a privileged individual with

Mr. and Mrs. Massey, to the central Hall. The lecture was upon

"Burns, and Love Poetry." The hall was crowded; but the lecturer

looked as if he expected a sheriff around. He was fidgety and

restless, and his annunciation was at times indistinct. I sat

besides Mrs. Massey. She said to me in a whisper; "Look"

Gerald is in love with that lady; I know it. See how he looks at

her!" Almost immediately came the recitation of the poem, "To Mary

is Heaven," and with an amazonian yell, Mrs. Massey fainted away, and I

was one of the bearers who conveyed her from the premises. It was

the same story wherever he lectured. Mrs. Massey systematically

fainted away, and had to be carried from the hall, while he looked on with

an expression of poignant anguish. There was no aristocratic houses

offering their hospitality to the poet and his wife now; but there were

humble friends who were not banished like bees by the wintry weather, who

now surrounded him, and who offered their "best apartments" as a dwelling

for the poet and his wife. And in one of these comfortable,

unpretending houses—No. 9 Summerhill Terrace, Newcastle-on-Tyne—I dined

with Massey and his wife in 1858. it was Sunday, and after dinner

Mr. M—, Massey and myself retired to the "library" to smoke. There

was no sentimental aversion to tobacco now in the poet's mind; but he had

a lingering fear—and expressed it— that "she" might burst into the room

at any moment. It was as he expected. She opened the door,

and, with the appearance of a Medea, cried: "Gerald! don't you know

'Carlo' is dying?" This was the dog, and the affect on the little

sensitive man was most distressing. Soon after she returned with the

announcement: "Gerald, our little Freddy is sick." "O, curse you,"

cried Massey, throwing down and breaking his long clay pipe, "you will

kill me!" At every town in which he lectured these scenes were

repeated. And she would wake him up in the night to retail horrible

visions, where some cherished member of his family was predicted dead.

By and by he began to believe that his wife possessed the power of

divination, and it was then not a difficult road for him to reach a

profound belief in Spiritualism.

His vagaries in the spiritualistic business are notorious to

all newspaper readers. In all of these eccentricities he has been

assisted by his wife. Together they have seen visions of babies and

hogs, and discovered that the bones of the weird visitors were buried

beneath the Massey hearthstone. These absurd visions he minutely

described in the London Spiritualist, and then his friends and

well-wishers began to suspect that his mental balance was shaken. A

few years since, it will be remembered, he lectured in Boston and other

New England towns on spiritualism. But the man had lost his

magnetism, and the lectures, as they deserved to be, were an absolute

failure. In point of fact, poor Massey has been approaching insanity

for years.

Most of Massey's latest writings have been on the subject of

spiritualism, and his most intimate friends have regarded every succeeding

speech or article as a nearer approach to lunacy. Massey will not be

regarded by critics as a strictly original poet. Taking Tennyson as

his model, he has, to some instances, almost servilely imitated that great

master. Still, there are poems of Massey's that can only perish with

the English language.

|

|

_____________________

From

THE BANNER OF LIGHT

Boston, March 15, 1884.

Gerald Massey in Springfield, Mass.

Sunday, March 9th, Gerald Massey, the distinguished lecturer

on the origins of Religions, gave a learned exposition of the fable of the

"Fall of Man" in Genesis. The audience was very large and paid

strict attention. Many of our editors and professional men were

present. His explanation of the astronomy of the ancient Egyptians

throws a flood of light upon the story of the Garden of Eden, the Serpent,

the Tree of Knowledge, etc. It was almost like a new revelation to

us to hear such clear and unanswerable explanations of these Bible myths.

Mr. Massey ought to be heard in every city in New England

before he goes West, for he has information of the gravest importance to

give to the people. His lectures lay bare the false foundations of

Christianity, and prove conclusively that the dogmas and ceremonies of the

Christian Church are misrepresentations of myths of antiquity whose

original signification has been lost to the people in the lapse of ages,

and yet whose meaning can be restored by a careful study of the mythology

of Egypt.

Public libraries ought to have Mr. Massey's book "Natural

Genesis" which gives in full his discoveries; and his lectures, which are

a popularized epitome of his researches, should eventually be printed in

cheap form for the masses.*

Mr. Massey has a magnetic voice and an earnest manner, and

both his thought and his delivery insure a charmed and instructed

audience. He will give two lectures at Gill's Hall, Sunday, March

16th. The subject for the evening lecture will be "The

Historical Jesus and the Mythical Christ."

Prof. Milleson will speak here on March 23rd, and James R.

Cocke, the blind musical medium, the 30th. The Spiritualists' Union will

have a meeting here on the 31st, particulars of which will be given you

next week.

H. A. BUDINGTON.

* Ed. While

not material that the "masses" would readily take up, as Mr. Budington

appears to think likely, Massey did eventually arrange (in 1887) for his

principal lectures to be printed individually as inexpensive booklets.

These, which are reproduced on our lectures page, remain available in modern reprints. |

|

_____________________

From

THE BANNER OF LIGHT

Boston, March 22, 1884.

Gerald Massey in Springfield, Mass.

Another full and very intelligent audience assembled Sunday evening, March

16th, to hear Mr. Massey in his masterly lecture on "The

Historical Jesus and the Mythical Christ." In this discourse

parallels are drawn between the gods of Egypt and the Christian Christ,

showing from the "Book of the Dead" that most of the stories of Jesus

found in the four gospels are modified copies of the Egyptian myths.

A number of citizens from other churches and some or our best

thinkers among the unchurched were present. The views of Mr. Massey

were new and startling to most, and yet they are founded on the facts of

facts of Egyptology. The Springfield Republican reported the

lecture, giving an unusual amount of space to it.

Prof. Milleson of Boston will lecture here next Sunday, the

23rd, and in the evening exhibit his paintings and diagrams of the

spirit-body, which he has made a study of for years, and which he claims

to have been shown clairvoyantly some new and beautiful truths.

H. A. BUDINGTON. |

|

____________________

From

THE BANNER OF LIGHT

Boston, Saturday, April 19, 1884.

Gerald Massey.

The poet, the scholar and the orator, concerning whom the friends of

Spiritualism on both sides of the Atlantic cannot do other than cherish an

appreciative memory, in view of the important services which he has, by

research, voice and pen, rendered the cause, is at present speaking in the

West, having just concluded his initial engagement in that quarter, at

Cleveland, O.

Mr. Massey's first lecture in Cleveland was given on the

evening of April 6th. Though the weather was very inclement, the

Church of the Unity, in which it was delivered, was crowded with an

appreciative audience. The subject was "The Mystery of Evil," and it

was dealt with in a manner so much out of the common course that every

word was listened to with the utmost degree of attention. The

lectures that followed increased the public interest, and when the

concluding one of the series was delivered, many regrets were expressed

that there were no more to be heard. Very favorable mention of them

was made by the press some of the papers giving quite lengthy notices,

including the leading points of each.

The manner in which Mr. Massey turns his scholarship and

learning to spiritualistic account is remarkable. For example, it is

commonly assumed that what is termed the phallic religion, the types and

symbols of which are found the world over, originated in a worship of the

generative powers. But Mr. Massey proves, in his lecture on

Man in search of his soul during

many thousand years, that the phallic imagery was first employed by

primitive man in the burial of the dead, whether in the re-birth place of

the Egyptians, the caves of Europe, or the "Navel-Mounds" of the red men.

He shows that the dead were buried in the tomb as the locale of re-birth;

end that the natural imagery of reproduction in this life was repeated as

the symbolism of reproduction and resurrection for another. In this

way he makes use of Spiritualism, the light of to-day, to read the

far-off facts that have been obscured in the dark places of the past.

His mode of treatment has proved interesting to all men, whether

Spiritualists or not. For instance, Courtlandt Palmer, the President

of the Nineteenth Century Club, testifies that he heard Mr. Massey's

lecture in New York with the most profound interest; and although a

Positivist himself, he says Mr. Massey's facts and deductions are of the

utmost value according to any theory of the world.

|

|

____________________

From

THE BANNER OF LIGHT

Boston, Saturday, 3 May 1884.

Gerald Massey in Grand Rapids.

The Grand Rapids (Mich.) Eagle, April 21st, speaks as follows

regarding Mr. Massey's Sunday discourse in that place:

|

"Quite a large audience listened to the lecture in Powers' Opera

House yesterday, by Gerald Massey, on the 'Mystery of Evil,' and all

seemed delighted with his masterly handling of the subject—some of

them saying that they could listen two hours longer without being

wearied. He gained their close attention from the first and

held it till the close. Mr. Massey is a rapid speaker, will a

great command of words, yet often his fervid sentences demand the

closest attention. By some he is called Emersonian in his

epigramatic utterances; but as a speaker his delivery as compared

with Emerson's, is like the rushing storm as compared with the

steady breeze of a dull morning. He may be set down as

pleasing and instructive speaker, whether his views are shared by

his auditors or not, and an impetuous platform orator."

|

Mr. Massey spoke in Grand Rapids April 20th, 23d and 25th,

and was to lecture there again the 28th. As noted in these columns

last week, he intends to devote some six weeks in May and June to places

between Chicago and San Francisco, on his way to Australia, where it is

said he has just concluded negotiations to deliver ten lectures. The

friends all along the route should make every effort to secure the

services of this ripe scholar and eloquent speaker.

|

|

____________________

From

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

16 January 1885.

Republished from The Harbinger of Light, 1 November, 1884.

GERALD MASSEY IN AUSTRALIA.

_______

On the evening of September 29, a conversazione was given in

Melbourne, to the members and friends of the Victorian Association of

Spiritualists, Mr. C. Johnston, President, in the chair. Between 300

and 400 persons were present. "The Harbinger of Light," November 1,

reports the following:—

"Mr. Gerald Massey, who was received with applause, responded

cordially to the words of welcome that had been spoken. He was, he

said, one of those 'cranks' called Spiritualists. He was not an

abnormal medium, as one of the papers had made him say, but his first wife

was mediumistic, and through her he had received many proofs. He

spoke of his state of health when he left England, after the completion of

his book, as very low, but he was glad to say he now found himself, after

his travels, very much better. He thought that Spiritualists did

not, as a rule, learn sufficiently from nature. They believed in the

natural; only that in that expression they properly included the

domain of the spiritual. But some Spiritualists, the moment they

found that certain extraordinary phenomena were true, at once thought that

it proved all the miracles recorded in the Bible to be true likewise.

These, however, were simply myths, and had to be interpreted by the light

of mythology. Spiritualists ought to be educated in the doctrine of

Evolution. The Denton Museum, which he was glad to see there, was a

step in the right direction, and he was also glad to find that the young

had an opportunity of being freed from the damnable doctrines which had

cursed their forefathers. Everywhere he went, he had found the

Spiritualists in a chaotic state, with many divergences of opinion, and he

had come to the conclusion that the object of Spiritualism was essentially

to make people independent in mind, and that they were not meant to think

alike, and that these divergences of opinion really formed a species of

protective bristling chevaux de frise around their facts. He

approved, however, of any attempt at confederation; for though they could

not meet to agree to think alike, they could meet to agree to do

something, to carry out some plan of action. He was not exactly a

representative sent out by English Spiritualists, but in some sort he did

represent them, and, therefore, in conclusion, in their name he tendered

to his hearers a cordial greeting."

Mr. Massey has been lecturing in the Theatre Royal, Sydney,

to crowded audiences. Of his lecture on "The Fall of Man," The

Liberal says: "We have no hesitation in describing it as the most

elaborate, the most learned, the most profound, and the most absorbingly

interesting discourse ever delivered in the City of Sydney."

We regret to learn that Mr. Massey has been taken ill in

Sydney.

|

|

____________________

From

THE MEDIUM AND DAYBREAK

27 November 1885.

Republished from The Rationalist, Auckland, New Zealand,

Sunday, August 30, 1885.

ORATION BY GERALD MASSEY

_______

PERORATION TO "A LEAF FROM THE BOOK

OF MY LIFE."

Mr. Gerald Massey again lectured on Sunday evening

last, to a large audience. The subject of the lecture was "A Leaf

out of the Book of my Life."

In his introductory remarks, Mr. Massey said: We have a class

of journalists in London and elsewhere, who grin for the public through

the horse-collar of the press. Their duty is to make fun of all that

is foreign to them. The more the seriousness the greater the

absurdity. Such writers have no comprehension, and can have no

respect for the love of truth, which alone could compel a man to volunteer

his testimony all the world round to an unpopular truth, in a case so

painfully personal as this of mine. In the course of my life I have

been a fighter in the forlorn hope of more than one unpopular cause,

beginning as a Chartist, but the clown who grins professionally for the

press must not, therefore, assume that I am the champion of an

unparalleled imposture. I am impelled to tell my story solely

because it is true, and because it enables me at times to be of use to

others who may be in the midst of some peculiar experience, the mystery of

which they cannot fathom by themselves. I am not here to

proselytize; only to state facts, and now and again to draw an inference.

We cannot generalize or form an opinion on any subject unless we have the

facts to go upon.

We reproduce the conclusion of the lecture verbatim:—

Mind you, I am not going to claim for Spiritualism any more

than it will carry. These phenomena, if true, are not about to prove and

re-establish the mythical miracles of the Old or New Testament as true.

The sun never stood still in heaven, in any time past, tho' all the tables

on earth should take to dancing in the present. I am aware that the

first effect of these phenomena on many observers, is to make a profound

appeal to the feeling of religions awe, and therefore to confirm the

orthodox in all the errors of their early thought. If certain

extensions of recognised laws take place in the present, why may not all

the mythical miracles of the past be veritable matters of fact; and of

course they may, if we have no means of distinguishing between them.

Thus, the primary tendency of spiritism, is to rehabilitate all the old

beliefs that have been founded on misinterpreted mythology, which have

been, and are, the cause of natural enmity between men of science and the