|

MORE than half a century has passed since a volume of poems, falling into Landor's hands, so entranced him that he wrote a letter to a leading London newspaper, proclaiming the appearance of a poet whom he rapturously compared now to Keats, now to "a chastened Hafiz," now to the Shakespeare of the sonnets when the sonnets are at their best.

Singling out a poem on Hood, "How rich and radiant," he said, was the following exhibition of Hood's

wit:

|

... His wit? a kind smile just to hearten us,

Rich foam-wreaths on the waves of lavish life,

That flasht o'er precious pearls and golden sands.

But there was that beneath surpassing show!

The starry soul, that shines when all is dark!—

Endurance that can suffer and grow strong,

Walk through the world with bleeding feet and smile! |

And he comments on the "rich exordium" of the same poem:

|

'Tis the old

story!—ever the blind world

Knows not its Angels of Deliverance

Till they stand glorified 'twixt earth and heaven. |

Then turning to the lyrics and quoting:

|

Ah! 'tis like a tale of olden

Time long, long ago;

When the world was in its golden

Prime, and love was lord below!

Every vein of Earth was dancing

With the Spring's new wine!

'Twas the pleasant time of flowers

When I met you, love of mine!

Ah! some spirit sure was straying

Out of heaven that day,

When I met you, Sweet! a-Maying,

In that merry, merry May.

Little heart! it shyly open'd

Its red leaves' love-lore

Like a rose that must be ripen'd

To the dainty, dainty core;

But its beauties daily brighten,

And it blooms so dear;

Tho' a many Winters whiten,

I go Maying all the year. |

"I am thought," he says, "to be more addicted to the ancients than to the moderns . . . but at the present time I am trying to recollect any Ode, Latin or Greek, more graceful than this."

In many pieces, he continues, "the flowers are crowded and pressed together, and overhang and almost overthrow the vase containing them," and he instances the "Oriental richness" of such a poem as Wedded Love.

|

|

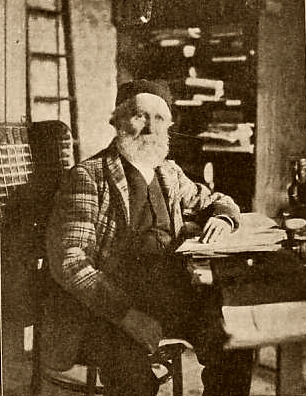

Gerald Massey (ca. 1905). |

Of the poet in whose work he found so much to admire, and in which he discerned such splendid promise, Landor knew no more than that "his station in life was obscure, his fortune far from prosperous," and that his name was Gerald Massey.

Had he known all he would indeed have marvelled. Whatever rank among poets may finally be assigned to Mr. Gerald Massey, and we may be quite sure that he will stand higher than some of those who at present appear to have superseded him, there can be no question about three

things—his genius, his singularly interesting personal history, and the gratitude due to him for his manifold services to the cause of liberty and to the cause of philanthropy.

If he has not fulfilled the extraordinary promise of his youth, he has produced poems instinct with noble enthusiasm, welling from the purest sources of lyric inspiration, exquisitely pathetic, sown thick with beauties.

His career affords one of the most striking examples on record of the power of genius to assert itself under conditions as unfavourable and malign as ever contributed to thwart and depress it.

But even apart from his work as a poet, and the inspiring story of his struggle with adverse fortune, he has other and higher claims to consideration and honour.

He is probably the last survivor of that band of enthusiasts to whose efforts we mainly owe it that the England of the opponents of all that was most reasonable in Chartism, the England of the grievances and abominations which Chartism sought to remedy, the England of the Report on which Ashley's Collieries Bill and of the Report on which his Address on National Education were based, the England of the opponents of the Maynooth Grant, of the persecutors of Maurice, was transformed into the England of to-day.

His revolutionary lyrics have done their work. The least that can be said for them is, that they are among the very best inspired by those wild times when Feargus O'Connor, Thomas Cooper, James [Bronterre] O'Brien and Ernest Jones were in their glory.

Of their effect in awakening and, making all allowance for their intemperance and extravagance, in educating our infant democracy and those who were to mould it there can be no question.

How vividly, as we listen to a strain like this, do those days come back to us:

|

Fling out the red Banner! the Patriots perish,

But where their bones whiten the seed striketh root:

Their blood hath run red the great harvest to cherish:

Now gather ye, Reapers, and garner the fruit.

Victory! Victory! Tyrants are quaking!

The Titan of toil from the bloody thrall starts,

The slaves are awaking, the dawn-light is breaking,

The foot-fall of Freedom beats quick at our hearts! |

If lines like the following had a message for those days which they have not for us, we can still feel their charm:

|

'Tis weary watching wave by wave,

And yet the tide heaves onward:

We climb, like Corals, grave by grave

That have a path-way sunward.

The world is rolling Freedom's way,

And ripening with her sorrow.

Take heart! who bear the Cross to-day

Shall wear the Crown to-morrow. |

And the truth of what their author wrote of these poems many years later few would dispute:

|

Our visions have not come to naught

Who saw by lightning in the night:

The deeds we dreamed are being wrought

By those who work in clearer light. |

So heartily and fully did Mr. Massey throw himself into the life of his time that all that is most memorable in our national history during the most stirring years of the latter half of the last century is mirrored in his poetry.

There is scarcely any side from which he has not approached it, from politics to spiritualism.

To the cause of Chartism he was all that Whittier was to the cause of the Abolitionists on the other side of the Atlantic.

Of the Russian War he was the veritable Tyrtaeus. It is impossible even now to read such a poem as New Year's Eve in Exile, and such ballads as

England Goes to War

[Ed. — Battle?], After Alma,

Before Inkermann

[Ed. — Inkermann?], Cathcart's

Hill, A War Winter's Night in

England, without emotions recalling those that thrilled in that iron time, when:

|

Out of the North the brute Colossus strode

With grimly solemn pace, proud in the might

That moves not but to crush, |

on fields

|

of the shuddering battle-shocks

Where none but the freed soul fled, |

in homes

Where all sate stern in the shadow of death.

In Havelock's March the heroes of the Indian Mutiny found a laureate as spirited and eloquent as Tennyson, whose

Defence of Lucknow, which appeared many years afterwards, was certainly modelled on Mr. Massey's poem.

Ever in the van of every movement making for liberty, he pleaded in fiery lyrics the cause of Italy against Austria; and, of all the tributes of honour and sympathy Garibaldi received, he received none worthier than the poems dedicated to him by his young English worshipper.

He extended the same sympathy to the Garibaldi of Hungary, and his Welcome to Kossuth, when he visited England in 1851, if it does no great credit to its author as a poet, is at least proof of the generous enthusiasm which inspired it.

But the passionate sympathy which he expressed for the friends of liberty was equalled by the vehemence of the detestation which he expressed for its enemies.

And pre-eminent among those enemies he regarded the "hero" of the coup

d'état and the founder of the Second Empire. We must go back to the broadsides of Swift to find any satire equalling in intensity and concentrated scorn the poems in which he gave vent to his contempt for

Louis Napoleon, and his indignation at the friendly reception accorded to him by England in 1853.

Take two stanzas of one of them:

|

There was a poor old Woman once, a daughter of our nation,

Before the Devil's portrait stood in ignorant adoration.

"You're bowing down to Satan, Ma'am," said some spectator, civil:

"Ah, Sir, it's best to be polite, for we may go to the Devil."

Bow, bow, bow,

We may go to the Devil, so it's just as well to bow.

So England hails the Saviour of Society, and will tarry at

His feet, nor see her Christ is he who sold Him, curs'd Iscariot,

By grace of God, or sleight of hand, he wears the royal vesture;

And at thy throne, Divine Success! we kneel with reverent

gesture,

And bow, bow, bow,

We may go to the Devil, so it's just as well to bow. |

Or take three stanzas from The Two

Napoleons:

|

One shook the world with earthquake-like a fiend

He sprang exultant—all hell following after!

The other, in burst of bubble and whiff of wind

Shook the world too—with laughter.

The First at least a splendid meteor shone!

The Second fizzed and fell, an aimless rocket;

Kingdoms were pocketed for France by one,

The other picked her pocket.

*

*

*

* *

That showed the Sphinx in front, with lion-paws,

Cold lust of death in the sleek face of her,—

This the turned, cowering tail and currish claws,

And hindermost disgrace of her. |

Worthy of Swift, too:

|

He stole on France, deflowered her in the night,

Then tore her tongue out lest she told the tale. |

And

|

Our ghost of Greatness bath not fled

At crowing of the Gallic Cock! |

But if in his poetry he has been the ally of those who have furthered the cause of liberty and humanity in the field and in politics, he has been an ally as loyal to those who have furthered it in other capacities.

When the bigots hunted down Maurice, he addressed brave words of comfort to him;

Bradlaugh's Burial is in praise of a martyr of more doubtful character perhaps, but it strikes the same note.

In the ringing lyric of Stanley's

Way, we have a tribute to heroism in another form. The fine poems on Burns, Hood, and Thackeray could only have come from one who had the sympathy and insight of kinship, and so could pierce at once to the essence of each, and the work of each.

No one indeed can go through the two volumes of Mr. Massey's poems without being struck with what struck George Eliot when, as she made no secret, she drew the portrait of their author in Felix

Holt—the innate nobility of the character impressed on them. Whatever may be their defects as compositions, and it may be conceded at once that they are neither few nor small, they have never the note of triviality.

Instinctively as a plant makes towards the light, the poet of these poems makes towards all that appeals and all that belongs to what is most virtuous, most pure, and most generous in man.

In some he kindles sympathy for the wrongs and miseries of the poor by giving pathetic voice to them; in others he pleads for the victims of injustice and oppression in his own and in foreign lands.

Here he calls on the patriot, there on the philanthropist to be true to trust and duty.

No poet has painted more vividly or dwelt with more fervour on the virtues which have made us, as a people, what we are at sea, on land, in the home.

Who can read unmoved such ballads as The

Norseman, Sir Richard Grenville's Last

Fight, which appears to have suggested Tennyson's Revenge, and

The Stoker's Story, such a lyric as

Love's Fairy Ring and

Wedded Love, the poem so much admired by Landor?

As his heart went out to the heroes and martyrs of the revolutions of the middle of the last century, and his sympathetic insight enabled him to discern and interpret what so many of his contemporaries were blind

to—the nobility and greatness underlying the foibles of Burns, the buffooneries of Hood, and the cynicism of

Thackeray—so wherever the beautiful or "aught that dignifies humanity" has found expression, whether on the heights of life or in its valleys, he has ever sprung to greet it with readiest and sincerest homage.

All this gives an attractiveness to his poetry quite irrespective of its merits as mere poetry, just as in human features there is often a beauty and a charm which is simply the reflection of moral character.

There was little in Mr. Massey's early surroundings to promise either such traits as these, or such poetry as they informed.

The story of his life is no secret, and a more striking illustration both of the independence of genius, when thrown on itself-for he had neither education nor sympathy-and of its irresistible

energy—for everything combined to thwart and depress it-cannot easily be found.

His father was a canal boatman of the ordinary type, supporting on ten shillings a week, in a wretched hovel, a numerous family.

A little elementary instruction at a penny school, to which his mother sent him, was all the education he ever received.

At eight years of age he was working in a silk mill, from five in the morning to half-past six in the evening, for a weekly wage beginning at

9d. and rising to 1s. 3d. Here he experienced all that Elizabeth Barrett so powerfully and pathetically denounced in a poem which nine years later brought indignant tears into the eyes of half England,

The Cry of the Children. From this cruel servitude the poor child was released by the mill being burnt down, and in some touching reminiscences of those dismal days he tells how he and other children stood for many hours in the wind and sleet and mud, watching joyfully the conflagration which set them free.

But he had only exchanged one form of toil for another quite as ill-paid and more unwholesome.

This was straw-plaiting. The plaiters, having to work in a marshy district with constitutions enfeebled by confinement and want of proper food, fell easy victims to ague.

Young Massey was no exception, and for three years he was racked, and sometimes quite prostrated, by this disease.

At these times and when his father was out of work the sufferings of the family were terrible.

It was only by unremitting drudgery, so miserable was the wage each could earn, that the wretched cabin which sheltered them and the barest necessities of life could be secured.

They were more than once literally on the verge of starvation. At one dreadful crisis they were all down with the ague, with no one to assist them, and unable to assist each other.

Well might Mr. Massey say, "I had no childhood. Ever since I can remember I have had the aching fear of want, throbbing in heart and brow."

It was these experiences which inspired the touching poem, Little Willie and

The Famine Smitten, and the "Factory-bell"

in

Lady Laura. But the lad, thanks to his mother, had been taught to read, and in his scanty leisure committed many chapters of the Bible to memory, and eagerly devoured such books as he could get at, among them the Pilgrim's Progress and Robinson Crusoe, which he took, he tells us, for true stories.

So passed the first fifteen years of his life. In or about 1843 he came up to London, where he was employed as an errand boy.

And now an eager desire for knowledge possessed him, and he devoured all that came in his way-history, political philosophy, travels, everything, strangely enough, but poetry, going without food to buy books, and without sleep to read them.

Sometimes in and sometimes out of employment, a waif and a stray, his only solace in this dismal time was his passion for information.

Then social questions began to interest him. His own bitter experiences naturally led him to brood over the wrongs and grievances against which the Chartists were protesting, and which they were seeking to remedy.

He attended their meetings and, inflamed not only by what he heard there but by what he had himself seen and suffered, as well as by the sympathetic study of the writings of English and French republicans, immediately threw himself heart and soul into the cause.

At last poetry awoke in him, inspired, he tells us, not by politics but by love.

His first volume, Original Poems and

Chansons, was published in 1847 by a provincial bookseller at Tring, his native place.

This was succeeded three years later by Voices of Freedom and Lyrics of

Love, a very great advance on the crude work of the preceding collection.

Meanwhile, though as poor as ever and amid surroundings as sordid and dismal as they could well be, his prospects had in some degree brightened.

He was beginning to feel his way with the pen. He started, and became the editor of, a cheap journal for working men, half of which was written by himself and the other half by them.

But this coming to the ears of the employers on whom he depended for his daily bread, and who were not likely to regard with much favour the propaganda of which it was the medium, he was continually turned adrift by being dismissed from such situations as he could manage to scramble into.

At last he fought his way to his proper place, and found he could rely on his pen at all events for a livelihood, if only a bare one.

He became a regular and valued contributor to the principal socialist journals, such as the

Leader, Thomas Cooper's Journal and the Christian

Socialist. This brought him into connection with his earliest friend Thomas Cooper, and subsequently with Charles Kingsley, who had just written

Alton Locke, and with F. D. Maurice. Nor was this all.

Dr. Samuel Smiles, ever helpful and ever quick to recognize merit, had been greatly struck by some of the lyrics in these publications and in the volume of 1850, and, hearing the young poet's history, wrote an eloquently appreciative review of both in a magazine long since defunct but in those days very popular.

He welcomed the advent of a new and true poet "who had won his experience in the school of the poor, and nobly earned his title to speak to them as a man and a brother, dowered with 'the hate of hate, the scorn of scorn, the love of

love' "; and, dwelling on the fact that the maker of poems so full of power and beauty was only twenty-three years of age, prophesied, if fortune was kind, a splendid future for him.

Fortune was not kind and was never going to be kind, but in Mr. Massey's next volume, published in 1854, appeared most of the poems on which his fame must mainly

rest—The Ballad of Babe Christabel with other Lyrical Poems [Ed.

—the North American edition was published as 'Poems

and Ballads']. From this moment his reputation was made.

The volume passed through edition after edition and became the subject of eulogies so unmeasured that they may well have turned a young poet's head.

But they did not turn the head of this poet. In a modest and manly preface prefixed to the third edition he deprecated the homage which had been, he said, prematurely paid him. "Some of the critics have called me a 'Poet': but that word is much too lightly spoken.

I know what a poet is too well to fancy that I am one yet; I may have something within which kindles flame-like at the breath of Love, or mounts into song in the presence of Beauty: but, alas! mine is a jarring lyre.

I have only entered the lists and inscribed my name—the race has yet to be run."

Referring to the political poems he was, he said, half-disinclined to give them a place in the volume, so averse was he "to sow dissension between class and class and fling firebrands among the combustibles of society."

"But," he added, "strange wrongs are daily done in the land, bitter feelings are felt, and wild words will be spoken."

Then he went on to say that his aspiration was to become the poet of the masses, to brighten and elevate the lives of those whose toils and sufferings, whose miseries and darkness he had himself shared.

"I yearn to raise them into lovable beings. I would kindle in their hearts a sense of the beauty and grandeur of the Universe, call forth the lineaments of Divinity in their poor, worn faces, give them glimpses of the grace and glory of Love and of the marvellous significance of Life, and elevate the standard of Humanity for all."

And to these aims he was nobly true, as innumerable poems were to testify, poems which if they have not always intrinsically the quality of poetry of a high order and which endures, went home influentially to hundreds of thousands in times when such appeals were of incalculable service to society.

When this volume was passing through the press the Crimean War had broken out, and, during its progress, the young poet found his themes in what it inspired.

The spirited ballads, in which he told the story of England's truth to herself and to her heroic past in that conflict, and in which just before he had deplored and denounced her apostasy from both in her recognition and welcome of Louis Napoleon, were collected and published in 1855, under the title of

War-waits. Then came the Indian Mutiny and another series of ballads in which the heroism of his countrymen and the achievements and virtues of one of the noblest and purest of England's sons were commemorated: these were also collected and republished in 1860 under the title of

Havelock's March. Nine years afterwards the regular sequence of his poetry and his serious life as a poet ceased with A Tale of Eternity and other Poems.

With Mr. Massey's subsequent career and occupations I am not here concerned.

In 1890, as his poems had never been collected, he was prevailed on to allow a selection of such as he thought most worthy of preservation to be made, and they appeared in two volumes under the title of

My Lyrical Life.

In a very modest preface he re-introduces himself to a generation which he assumes has forgotten him, and to which his poems will be "as good as MS."

For himself, he says, they "may contain the flower, but the fruit of my life is to be looked for elsewhere by those who are in sympathy with my purpose."

The enormous labours, "the fruit" to which Mr. Massey refers, his Book of Me

Beginnings, his Natural Genesis and the like—the value of these must be estimated by those competent to estimate it.

It is with the "flower" and the flower-time of Mr. Massey's life that I am here concerned and seek to interest others, with the poet and enthusiast to whom Ruskin wrote:

I rejoice in acknowledging my own debt of gratitude to you for many an encouraging and noble thought and expression of thought, and my conviction that your poems in the mass have been a helpful and precious gift to the working-classes (I use the term in its widest and highest sense) of the country, that few national services can be greater than that which you have rendered.

The history and career of Mr. Massey can never be separated from his work as a poet, and taken together they form a record which surely deserves to live.

Of the services to which Ruskin refers I have already spoken.

In considering his work as a poet I do not propose to deal with it critically, to balance its merits and shortcomings, and to enter into any discussion about his relative place among the poets of his time.

I wish to dwell only on its beauties, on its very real beauties, and to invite the attention of all for whom poetry has charm to the two little volumes "which are as good as MS."

The Ballad of Babe Christabel is one of the richest and most pathetic poems in our language, sown thick with exquisite beauties; as here:

|

In this dim world of clouding cares,

We rarely know, till wildered eyes

See white wings lessening up the skies,

The Angels with us unawares.

*

*

*

* *

Through Childhood's morning land, serene

She walked betwixt us twain, like Love;

While, in a robe of light above,

Her guardian Angel watched unseen.

Till life's highway broke bleak and wild;

Then, lest her starry garments trail

In mire, heart bleed, and courage fail,

The Angel's arms caught up the child.

Her wave of life hath backward roll'd

To the great ocean; on whose shore

We wander up and down to store

Some treasure of the times of old. |

And this:

|

We sat and watched by Life's dark stream

Our love-lamp blown about the night,

With hearts that lived as lived its light,

And died as died its precious gleam. |

And this:

|

With her white hands clasped she sleepeth; heart is hushed

and lips are cold

Death shrouds up her heaven of beauty, and a weary way we

go,

Like the sheep without a shepherd on the wintry Norland wold,

With the face of day shut out by blinding snow.

O'er its widowed nest my heart sits moaning for its youngling

fled

From this world of wail and weeping, gone to join her starry

peers;

And my light of life's o'ershadowed where the dear one lieth

dead;

And I'm crying in the dark with many fears.

All last night she seemed near me, like a lost belovèd bird,

Beating at the lattice louder than the sobbing wind and rain;

And I called across the night with tender name and fondling

word;

And I yearned out through the darkness, all in vain.

Heart will plead, "Eyes cannot see her: they are blind with

tears of pain,"

And it climbeth up and straineth for dear life to look, and hark

While I call her once again: but there cometh no refrain,

And it droppeth down and dieth in the dark. |

As long as a shaft, as cruelly barbed as any that Fate holds in its quiver, flies to its aim, will

The Mother's Idol Broken find response:

|

Ere the soul loosed from its last ledge of life,

Her little face peered round with anxious eyes,

Then, seeing all the old faces, dropped content.

The mystery dilated in her look,

Which on the darkening deathground, faintly caught

Some likeness of the Angel shining near. |

Full of wisdom and beauty is the poem

Wedded Love:

|

We have had sorrows, love! and wept the tears

That run the rose-hue from the cheeks of Life;

But grief hath jewels as night hath her stars,

And she revealeth what we ne'er had known,

With Joy's wreath tumbled o'er our blinded eyes. |

The kindred poems, The Young Poet to His

Wife, Long Expected and

Wooed and Won are full of rich beauty.

In Memoriam, with

its eloquent and impressive exordium, is a poem over which most of those

who have been initiated in "the solemn mysteries of grief" will

gratefully linger. How sunny are many of his lyrics, how full of

grace! Take the following:

|

We cannot lift the wintry pall

From buried life: nor bring

Back, with Love's passionate thinking, all

The glory of the Spring.

But soft along the old green way

We feel her breath of gold:

Glad ripples round her presence play;

She comes!—and all is told.

*

*

*

* *

She comes! like dawn in Spring her fame!

My winter-world doth melt;

The thorns with flowers are all a-flame.

She smiles!—and all is felt. |

If a more charmingly touching lyric than

Cousin Winnie exists in our language, where is it to be found?

It is impossible to go through these volumes without being struck with the felicities which meet us at every turn, now of thought, now of sentiment, now of expression.

How happily, for example, are Hood's witticisms described as:

Rich foam-wreaths on the waves of lavish life,

and men in affliction as those

To whom Night brings the larger thoughts like stars.

How beautifully true and how originally expressed is this:

|

The plough of Time breaks up our Eden-land,

And tramples down its flowery virgin prime.

Yet through the dust of ages living shoots

O' the old immortal seed start in the furrows. |

How happy this:

|

The best fruit loads the broken bough:

And in the wounds our sufferings plough

Love sows its own immortal seed. |

Or:

|

Hope builds up

Her rainbow over Memory's tears. |

How simple and true is the pathos here:

|

The silence never broken by a sound

We still keep listening for: the spirit's loss

Of its old clinging place, that makes our life

A dead leaf drifting desolately free. |

And this too we pause over:

|

Who work for freedom win not in an hour.

The seed of that great truth from which shall spring

The forest of the future, and give shade

To those that reap the harvest, must be watched

With faith that fails not, fed with rain of tears,

And walled around with life that fought and fell. |

And this:

|

The world is waking from its phantom dreams

To make out that which is from that which seems;

And in the light of day shall blush to find

What wraiths of darkness had the power to blind

Its vision, what thin walls of misty gray,

As if of granite, stopped its outward way. |

This, too, was worth saying and is well said:

|

Prepare to die? Prepare to live,

We know not what is living:

And let us for the world's good give,

As God is ever-giving. |

In The Haunted

Hurst, A Tale of Eternity Mr. Massey struck a new note, and has produced a most powerful and original poem to which I know no parallel in poetry.

It was occasioned and inspired by certain extraordinary experiences which he once had in a certain house where many years ago he resided, and which had the effect of converting him to Spiritualism.

With the esoteric interest which it no doubt has for Spiritualists I have no concern, but its dramatic and poetic interest is so great that an account of it will probably be as acceptable to those who have no sympathy with the creeds which it is designed to support and illustrate as to those who have.

The physical fact on which it is founded was the discovery of a child's skeleton in the garden of the house occupied by the poet, the metaphysical fact the apparition of the materialized spirit of the self-destroyed murderer, who tells the story of the crime and of the punishment posthumously inflicted on him.

The poem opens weirdly and vividly with a description of the phenomena commonly associated with so-called haunted houses, but here symbolic of the tragedy afterwards divulged:

|

At times a noise, as though a dungeon door

Had grated, with set teeth, against the floor:

A ring of iron on the stones: a sound

As if of granite into powder ground.

A mattock and a spade at work! sad sighs

As of a wave that sobs and faints and dies.

And then a shudder of the house: a scrawl .

As though a knife scored letters on the wall.

*

*

*

* *

The wind would rise and wail most humanly,

With a low scream of stifled agony

Over the birth of life about to be. |

At last "the veil was rent that shows the Dead not dead," and live figures define themselves; one:

|

A face in which the life had burned away

To cinders of the soul and ashes gray:

The forehead furrowed with a sombre frown

That seemed the image, in shadow, of Death's Crown.

*

*

*

* *

The faintest gleam of corpse-light, lurid, wan,

Showed me the lying likeness of a man!

The old soiled lining of some mortal dress. |

the other:

|

A dream of glory in my night of grief.

*

*

*

* *

She wore a purple vesture thin as mist,

The Breath of Dawn upon the plum dew-kissed.

*

*

*

* *

The purple shine of violets wet with dew

Was in her eyes. |

And the first apparition tells its horrible story, the tragedy of its earthly life, the lust that led to murder and from murder to self-destruction.

|

She was a buxom beauty!

*

*

*

* *

No demon ever toyed with worthier folds,

About a comelier throat, to strangle souls;

A face that dazzled you with life's white heat,

Devouring, as it drew you off your feet,

With eyes that set the Beast o' the blood astir,

Leaping in heart and brain, alive for her;

Lithe, amorous lips, cruel in curve and hue,

Which, greedy as the grave, my kisses drew

With hers, that to my mouth like live things clung

Long after, and in memory fiercely stung. |

One wild and stormy night, the shame of her sin having driven her from her home and friends, she rushes into her lover's house with her new-born child:

|

Harsh as the whet-stone on the mower's scythe

She rasped me all on edge; the hell-sparks flew,

Till there seemed nothing that I dared not do.

"Kill it, you coward!" |

And the wretch murders the child, to perish afterwards, in the agonies of frenzy and remorse, by his own hand:

|

I fancied when I took the headlong leap,

That death would be an everlasting sleep:

And the white winding sheet and green sod might

Shut out the world, and I have done with sight.

Cold water from my hand had sluic'd the warm

And crimson carnage; safe the little form

Lay underground; the tiny trembling waif

Of life hid from the light: my secret safe. |

But this was not to be. The panic horror of one awful moment was to become stereotyped for ever. He had made the child's grave in a chamber of which he had lost the key, and so exposed his crime—for the grave was open—to instant discovery. So:

|

The lost soul whirls and eddies round

The grave-place where the lost key must be found.

*

*

*

* *

He often sees it, but he cannot touch

It: like a live thing it eludes his clutch—

Gone, like that glitter from the eyes of Death,

In the black river at night that slides beneath

The Bridges, tempting souls of Suicides

To find the promised rest it always hides. |

All this, as well as the Angel-form who acts as interpreter, reveals itself in clairvoyance to the poet, explaining the sounds heard in the house:

|

The liquid gurgle and the ring

Metallic, with the heavy plop and ping,

. .

. .

. The grinding sound

O' the grating door; the digging underground;

The shudders of the house; the sighs and moans;

The ring of iron dropt upon the stones;

The cloudy presence prowling near. |

Sometimes, as here, with tragic power, and sometimes with infinite pathos, the poem explains and illustrates that what we call death is but life's continuance behind a veil which it is in the power of some who are still in the flesh to uplift; that the impressions which the soul receives from earthly experience it retains long after the body is dust; that Heaven and Hell, with those who people them, are around us and in our midst, the barrier dividing them from us so thin that for some it scarcely exists.

Of all this the poem gives us many weird and most impressive illustrations; such as the story of the man who, seeing a woman, with a beautiful child in her arms, standing begging in a crowded London thoroughfare, placed in her outstretched hand—for he was touched with pity for the child—a golden coin, only to find it ringing on the pavement at his feet, and no woman or child any longer visible:

|

He was one of those who see

At times side-glimpses of eternity.

The Beggar was a Spirit, doomed to plead

With hurrying wayfarers, who took no heed,

But passed her by, indifferent as the dead,

Till one should hear her voice and turn the head.

Doomed to stand there and beg for bread, in tears,

To feed her child that had been dead for years.

This was the very spot where she had spent

Its life for drink, and this the punishment. |

In sentiment, in imagery, and in expression there is much in this original and powerful poem over which no reader can fail to pause.

Never have the genesis and progress of evil in the human soul been more subtly and terribly described and analyzed than in the Fifth Part, and if we are not prepared to accept every article in the creed of this poem we can at least understand the wisdom and force of such lines as these:

|

If those blind Unbelievers did but know

Through what a perilous Unknown they go

By light of day; what furtive eyes do mark

Them fiercely from their ambush of the dark;

What motes of spirit dance in every beam;

What grim realities mix with their dream;

What serpents try to pull down fallen souls,

As earth-worms drag the dead leaves through their holes

. .

. . .

How, toad-like, at the ear will work

The squatted Satan, wickedly at work.

*

*

*

* *

Till from some little rift in nature yawns

A black abyss of madness, and Hell dawns. |

And how beautifully is the Divine guidance described as:

|

The magnet in the soul that points on through

All tempests, and still trembles to be true, |

and as

|

A bridge of spirit laid in beams of light,

Mysteriously across a gulf of night. |

Nor are the comments on the perversions of Christianity even now altogether superfluous, and very far indeed from profanity is the aspiration:

|

Forgive me, Lord, if wrongly I divine,

I dare not think Thy pity less than mine. |

It is characteristic of Mr. Massey's cheerful optimism that a poem which begins so grimly, and that a theosophy which involves so much which is both sombre and awful should conclude with an assurance

|

That all divergent lines at length will meet,

To make the clasping round of Love complete;

The rift 'twixt Sense and Spirit will be healed

Before creation's work is crowned and sealed;

Evil shall die, like dung about the root

Of Good, or climb converted into fruit.

All blots of error bleached in Heaven's sight;

All life's perplexing colours lost in light. |

I have indulged very freely in quotation, but I must find room for the following noble lines which conclude the sixth part:

|

Lean nearer to the Heart that beats through night;

Its curtain of the dark your veil of light.

Peace Halcyon—like to founded faith is given,

And it can float on a reflected Heaven

Surely as Knowledge that doth rest at last

Isled on its "Atom" in the unfathomed vast

Life-Ocean, heaving through the infinite,

From out whose dark the shows of being flit,

In flashes of the climbing waves' white crest;

Some few a moment luminous o'er the rest! |

I have already said that I shall not presume to attempt any estimate of Mr. Massey's relative position among the poets of the Victorian era; if he has no pretension to rank among its classics, in the house of song there are many mansions.

My purpose will have been fulfilled if I recall to a generation which, judging from popular anthologies and current literary memoirs, appears to have forgotten them, poems full of interest and full of charm. |