|

1 - The Registers.

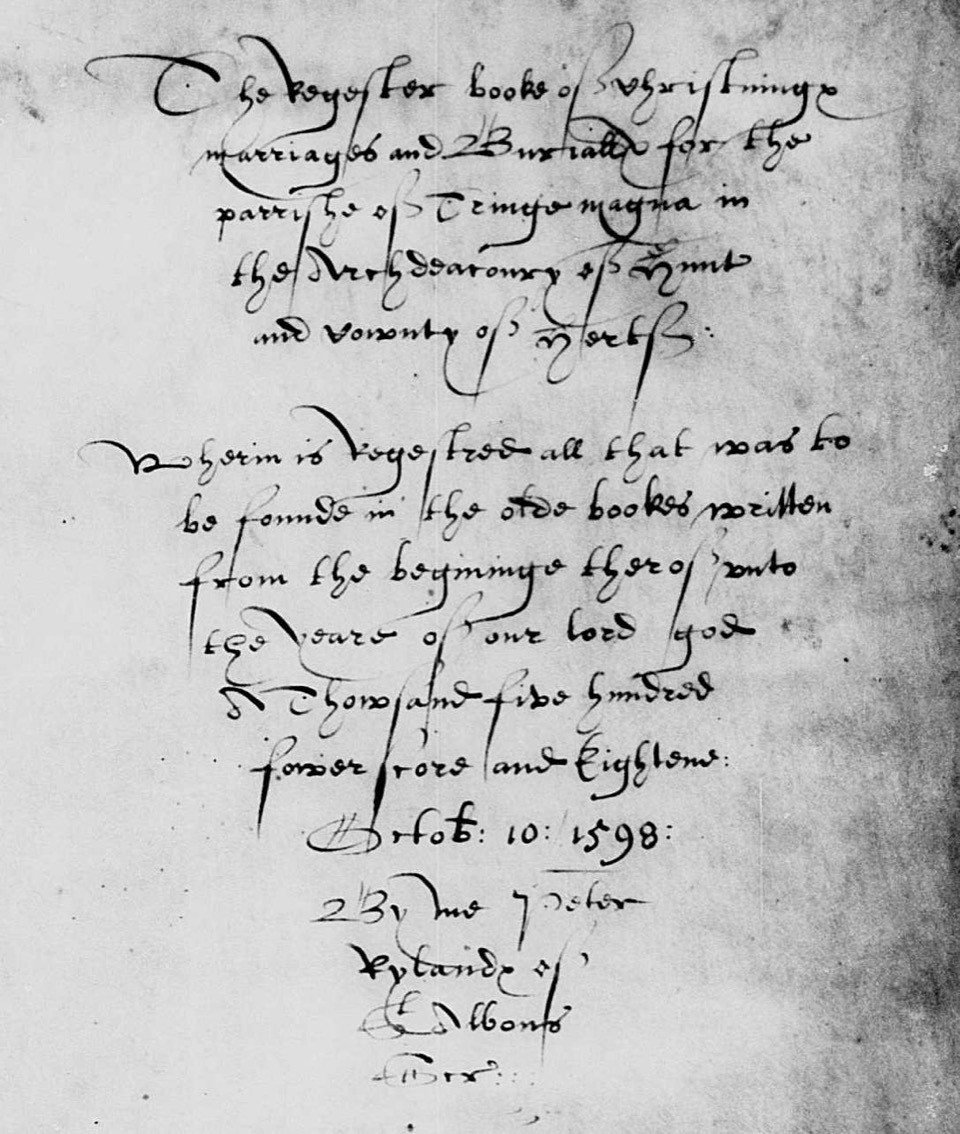

A page from Tring

Parish Registers, 1566 (HALS).

Prior to 1538 many English parishes kept an informal record of

important events concerning their parishioners. Henry VIII’s

break from Rome brought profound changes to the church in England

and in 1538 Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s chief minister, ordered

the parish clergy to keep a formal record of christenings, marriages

and burials.

The registers for the parish church of Tring, St Peter & St Paul,

are now kept by the Hertfordshire County Archive [HALS] in Hertford.

They start in 1566 and, for the years up to 1714, consist of four

volumes. The first book, now called Book 1, runs from 1566 to

1634. Book 3 runs from 1634 to 1695 and the fourth book runs

from 1695 to 1714. Book 2 contains a copy of the entries in

Book 1 and Book 3 up to 1673 plus some earlier records not in the

first book.

In the mid 16th century all that was required to be recorded were

names and dates. It is likely that the initial record was made

on a separate sheet or even scraps of paper which were periodically

copied into the register book.

At the start of Tring’s first book, marriages and burials were

recorded in separate sections. Later, christenings were added

and the arrangement changed so that all three types of record were

recorded together for each year. The writing and layout are

neat and in a single hand in 1566, but in later years different

hands become evident and the entries become cramped and messy.

Between 1577 and 1587 there is a gap in the records. No

explanation is given for this omission, but resumption in recording

corresponds with a change of curate. Thomas Norfolk’s name

appears at the top of a page of burials for 1573 and the entries

continue until the beginning of 1575 when they stop abruptly.

Marriages continue into 1576 and baptisms do not start until 1598.

According to the Clergy of the Church of England Database, Norfolk

remained curate in Tring until 1585. Recording begins again in 1587

when Timothy Fisher, curate, signed the register. It is

possible that Norfolk was less rigorous about recording baptisms,

marriages and burials or, more likely, he recorded them in a

separate document which is now lost.

In 1597, in the reign of Elizabeth I, it was ordered that the pages

of the parish registers should be made of more durable parchment,

rather than paper, and a copy sent to the Bishop annually for added

security. At the time, Tring was in the Archdeaconry of

Huntingdonshire in the Diocese of Lincoln so copies were sent there.

These copies are now called the Bishop’s Transcripts and for Tring

they survive from 1604 onwards. In addition, the earlier,

paper, registers had to be copied into the new parchment books.

In accordance with this edict a parchment copy was made of the Tring

register entries up to 1598. However, parchment is expensive

and subsequent Tring registers reverted to the use of paper.

Tring Parish Registers

vol. 2: Peter Rylande’s inscription (HALS).

We know who made the parchment copy because his name is on the

fly-leaf of the book: Peter Rylande of St Albans. As a

professional scribe or scrivener Rylande would have been paid for

his work. He may be the Peter Rilande of St Albans who married

there in 1583 and had several children. He died and was buried

in St Albans in 1621. He may also have been the Peter

“Rylands” who appears in many documents associated with the St

Albans Archdeacon’s court between 1593 and 1612 (St Albans parish

registers and HALS online catalogue reference ASA7).

Rylande’s copy is not exactly the same as the original, for example,

it starts with baptisms from 1566 to 1597 (with the exception of the

missing years 1577 to 1586) which are missing from the original book

and includes burials from 1588 to 1597, also missing from the

original book. Which means there was at least one other book,

now lost. In addition, the records in the parchment copy are

organised differently from the original book, with christenings,

marriages and burials in separate sections instead of being together

for each year. The spelling of some names also differ from the

original. Before the early 19th century most ordinary people

could not read or write and so the writer would spell the name as it

sounded.

As time went by the authorities made changes to what was required to

be recorded in the parish registers. The English Civil war in

particular brought upheaval to the lives of ordinary folk.

When Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans came to power in 1653 they

threw out the old modes of worship and anything that could be

interpreted as excessive, extravagant or leaning towards

Catholicism. Sundays were to be strictly reserved for worship

and the traditional Christian calendar of holy days and saint’s days

was banned, including festivals like Christmas and Easter.

On 24th August 1653 an act was passed in Parliament transferring the

responsibility for recording from the Church to the civil

authorities. In some parishes ministers destroyed or hid their

registers rather than surrender them to the new authorities.

Thankfully this did not happen in Tring and the register continued

in use.

The aptly named Benjamin Parish (or Parrish) was made responsible

for recording all births, marriages and burials in the Tring

register. Benjamin would have been familiar with the registers

as he was the son of William Parish who had been parish clerk in the

1630s. Three months later John Bates, also a local man, was

appointed “Legester” or registrar and took over this responsibility.

Thereafter only dates of birth, as opposed to baptism, were recorded

with the occasional exception, including two of John Dagnall of the

Grove’s children. These baptismal entries were most likely

added later, probably after the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660,

which would suggest that the Dagnalls, and perhaps a few other Tring

families, baptised their children privately, and possibly in secret,

during the Interregnum.

The recording of marriages also changed after the act came into

force. Actual marriages, with some exceptions, were no longer

recorded in the parish register and no longer took place in church.

However, the publication of the intention to marry, was recorded in

the register. The marriage ceremony itself became a civil

affair carried out by a magistrate. Two such marriages are

recorded in the Tring register: John Leash of Long Marston married

Susanna Brigginshaw, a widow of Tring, in January 1654 and Walter

Church, a gentleman, married Anne Price in March the same year.

That these two marriages were recorded in the register is unusual

and it may be that both couples had connections with influential

people especially as they were married by Sir William Rowe, a

Justice of the Peace and an associate of Oliver Cromwell.

Rowe’s brother Thomas, a Doctor of Divinity was buried in Tring

fifteen years earlier in 1639 and his burial entry includes an

intriguing note that says he was buried at night. There is

nothing sinister about this: as a member of the nobility, Thomas

Rowe was entitled to a traditional College of Arms funeral which

would have been an expensive and onerous imposition on his family.

In his will Thomas says that he is to be buried according to the

wishes of his executors and it seems they were keen to avoid an

extravagant funeral either for financial reasons or because of the

association of elaborate ceremony with Catholicism. Burial at

night was a way of avoiding a College of Arms ceremony as the

College stipulated that funerals should be carried out during

daylight hours (Brady, p78).

The monarchy was restored in May 1660 and baptisms in Tring resumed

immediately. For the rest of that year only one or two

children’s births were recorded without baptism.

After the Restoration Tring’s registers did not revert to orderly

recording. Instead baptisms were sometimes grouped by family

rather than in strict date order and odd entries appear in odd

places. Recording was messy and erratic with different hands

evident. Part of this chaos was the result of attempts to fill

in the gaps in the register caused by the events surrounding the

Civil War, but also Tring had five changes of Rector from 1660 to

1684 which may account for the different handwriting (see

note 1).

During the reign of Charles II a series of acts were brought in

affecting burials. The Burying in Woollen acts between 1666

and 1680 were designed to stimulate the English woollen industry.

A friend or relative of the deceased person was required to swear an

oath in front of a Justice of the Peace to confirm that the person

had been buried in a woollen shroud as opposed to a shroud made from

foreign textiles or other material, usually linen, which was much

cheaper than wool. Exceptions were made for plague victims and

the very poor.

It is worth noting that at the time the poor may not have been

buried in a coffin but simply wrapped in a shroud and buried in the

earth. The majority of people would not have had a headstone (Mytum,

p 97).

At the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th the

entries in Tring’s parish registers become more detailed: for

example, occupations start to be recorded frequently rather than

occasionally.

Over the whole period from 1566 to 1714 approximately 3740 baptisms

and births, 3218 burials and 663 marriages were recorded in Tring

Parish Registers. As noted above, recording was not always

consistent, nor are the pages of the registers always easy to read,

hence these figures are approximate. |

![]()

![]()