|

THE GRAND JUNCTION CANAL

A HIGHWAY

LAID WITH

WATER.

PART III ― THE ROUTE

INTRODUCTION

“The Basin of the Canal at Paddington is a large square sheet of

water occupying many acres, with warehouses on either of its sides,

and so commodiously sheltered, that goods of every kind can be

shipped or unloaded without the danger of being wetted. This

is a most desirable advantage, as the fly boats from Manchester

bring a variety of fine articles that require every care.

Since the canal has been brought to Paddington, this place has

become an extensive and well frequented market for cattle, sheep,

butter, poultry, etc.”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell

In 1819 the travel writer and watercolourist John Hassell published

an illustrated account of a journey from London to Braunston

along the route of the Grand Junction Canal. However, the

title that Hassell chose for his travelogue ― A Tour of the Grand

Junction Canal in 1819 ― is something of a misnomer,

for having visited Paddington Basin he then travelled by road to

Watford, thereby excluding the Canal’s busy southernmost section,

which, following Paddington Basin, he felt “ceases to

be interesting”. At Watford he began his journey during

which he wandered quite widely from the Canal to visit places

of interest. Churches, manor houses, stately homes (together

with their occupants and artworks), villages, towns and historical

events all come under his pen. But, with the exception of

Paddington Basin, canal wharves, their operators and the nature and

extent of their trade go unnoticed, as do the boatmen; perhaps in Hassell’s day such subjects were too mundane to be worthy of

recording. And although details of the waterway’s construction

and its challenges would still have been fresh at this time, Hassell

tells us very little about them or the people who achieved this

great feat of civil engineering, the M1 of its day. Thus,

while he provides some interesting cameos, Hassell too often frustrates by dwelling on subjects of no relevance to the matter in

hand.

Nevertheless, the three chapters that form this section of our account

are influenced by Hassell’s plan. They provide a brief

description ― a complete study would easily fill a book ― of the

route followed by the Grand Junction Canal, in our case southbound from

Braunston to Brentford. And to address the apparent

shortcomings in Hassell’s account, we focus out attention on the

waterway, particularly on further construction following its delayed opening

in 1805.

With regard to commerce, more is written about the Canal’s southern

section. This is due to the greater prevalence of

industry in the south and to the early abandonment of most of the

wharves along the Canal’s rural northern section. By the

1930s, the Grand Union Canal Company listed only six of the sixty

wharfs north of Berkhamsted as hosting tenant traders, and most of

those were connected with the sand trade in the Leighton area.

Grand Union canal: Birmingham to Marsworth.

I. ― BRAUNSTON TO

MARSWORTH JUNCTION

From its northern extremity at Braunston in Northamptonshire, the

Grand Junction Canal follows a south-easterly path to the Thames at Brentford,

a distance of 93½ miles (viz.

system map). Within its length it passes

through the counties of Northamptonshire, Bedfordshire (for a short

distance), Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire and Middlesex;

crosses summits at Braunston and Tring; passes through long tunnels

at Braunston and Blisworth, and negotiates 102 locks [0]. There

are substantial embankments at Wolverton, Weedon Bec, Heyford,

Bugbrook and Cosgrove, and substantial cuttings on both approaches

to Blisworth Tunnel and at Tring (1½ miles). There are three

significant aqueducts ― Benjamin Bevan’s Great Ouse Aqueduct (1811);

the New Bradwell Aqueduct at Milton Keynes (1991); and Brunel’s ‘Three Bridges’

Aqueduct (1859) at Southall. On the Paddington Arm there

is a further significant aqueduct across

London’s North Circular Road, the present structure dating from 1993

when the road was widened. There are also numerous small

aqueducts, including three that carry the Slough Arm over the Fray’s

and Colne rivers and the interesting Kilburn Aqueduct (now a part

of the Ranelagh sewer), which lies buried beneath the Paddington Arm

near Little Venice.

――――♦――――

At Braunston, the Grand Junction

and Oxford canals meet at an unusual triangular junction.

From this point the Oxford

Canal heads north to Rugby and Coventry, and south to Banbury,

Oxford and the Thames.

In 1929, the Grand Junction, the Regent’s Canal and the Warwick

canal companies amalgamated to form the Grand Union Canal (Chapter XIV.).

The effect of the amalgamation (together with the negotiation of

running rights over a 5-mile length of the Oxford canal) was to extend

the former Grand Junction main line from

Braunston to the outskirts of Birmingham. Thus, at Braunston

Junction, the main line turns south along the Oxford Canal to Napton Junction,

from where it heads in a westerly direction

via Leamington, Warwick and Knowle to reach Camphill Locks

at Birmingham. [1] During the 1930s, the

Company invested heavily in improving its Braunston to Birmingham

section in an attempt to regain trade from the railways. The

waterway was widened and deepened, and new wider locks and bridges

constructed, but as the Company could not afford to extend these

improvements over the entire main line to London, their plan to use

larger craft (12ft 6in beam ‘wide boats’) on the route failed to

materialise.

.JPG)

Braunston Junction looking south along the

Oxford Canal.

.JPG)

Braunston Junction: a third Horseley Iron

Works bridge spans the entrance to nearby Braunston Marina.

――――♦――――

The village of Braunston was once an important hub in our national

transport system, thriving for many years on the transportation of

goods by canal between the Midlands and London. The original

canal depot now hosts Braunston Marina, and although little of its

Georgian and Victorian commercial past is plainly evident, its entrance

remains

dominated by one of three splendid cast iron bridges built by the

Horsley Iron Works ― its two partners span the nearby turning from

the Grand Junction into the Oxford Canal. Well-known canal

carrying companies including Pickfords and Fellowes, Moreton &

Clayton had facilities at Braunston, and many former canal

families have links to the village, if only to the graveyard of All

Saints Church. Today, leisure boating dominates and Braunston

Marina provides mooring facilities for some 250 boats together with

the attendant servicing and support facilities.

Commencing at Braunston Junction, the Grand Junction Canal heads

in an easterly direction, ascending a flight of six locks to reach the first of its two

summit levels, before passing through Braunston Tunnel (2,040yds).

The Daventry and Drayton reservoirs to the south of the Canal act as

feeders for the 3½ mile Braunston summit pound.

Norton

Junction lies some 2 miles to the east of Braunston Tunnel, at

which point the ‘old’ Grand Union Canal [2] heads north towards Market Harborough

and — via the former Leicestershire & Northampton Union Canal and

the River Soar Navigation — to Leicester, Loughborough and the River Trent.

The northern portal of

Braunston Tunnel.

The Leicestershire and Northampton Union Canal was originally

planned to link the River Soar at Leicester with the River Nene at

Northampton, and from there to connect with the Grand Junction Canal. It

received its Act in 1793, but by 1797 funds had run out with

construction halted at Debdale, some 6 miles from Market Harborough.

There progress rested until, in 1805, a further Act was obtained

authorising the Canal to be extended to Market Harborough, which it

reached in 1809, some miles short of and with no prospect of ever

reaching Northamptonshire, let alone its county town. Perhaps

prompted by the project’s failure and their continuing wish to

connect to Leicester and onwards to the Trent, the Grand Junction

Canal Company had James Barnes survey a route ― as did Thomas

Telford ― to link the two canals. In fact Barnes was to undertake three

surveys, which together with Telford’s is indicative of

the difficult terrain to be crossed, for it lacks river valleys or

any other obvious routes for a canal.

A new company, the ‘Grand Union Canal Company’ ― not to be confused

with the company of that name formed in 1929 ― was promoted to

build the link, which extended from Norton on the Grand Junction

Canal, to Foxton on the Leicestershire & Northampton Union Canal.

Benjamin Bevan was appointed

Engineer, and he chose the shorter route proposed by Barnes over

that by Telford. The undulating countryside to be

crossed required cuttings, embankments and two significant tunnels,

one of 1,528 yards at Crick and another of 1,166 yards at Husbands

Bosworth, both of which were built wide enough to allow two narrow

boats to pass abreast. All the locks were built narrow (7ft)

and grouped into two flights at opposite ends of the Canal ― two staircases of five

separated by a short pound at Foxton and a staircase of four and three single locks at Watford

― linked by a 22-mile pound.

Other than the earthworks, water supply was also a problem, with the Canal depending on that gathered in reservoirs at Welford, Sulby

and Naseby, which, in effect, also provided free gratis a supply to the Grand

Junction Canal. The 1¾-mile Welford branch was built as a

navigable feeder to channel water from the reservoirs into the Canal, the

short pound between Welford Lock and the terminus being the highest

point on the present day Grand Union Canal system.

.JPG)

|

The northern extremity of the ‘old’ Grand

Union Canal at Foxton (junction with the former

Leicestershire and Northampton Union Canal), and the commencement of

the famous 10-lock double staircase. Note the narrow (7ft) lock gate. |

The extent of the celebration that accompanied the Canal’s

opening in 1814 are perhaps difficult to understand in an age

when our navigable inland waterways are

regarded in the general scheme of things as unimportant .

. . .

“On Tuesday the 9th inst. the Grand Union Canal was formally

opened by the Committee of Management, who assembled at Long Buckby

Wharf, with several of the neighbouring Gentlemen and a Deputation

from the Union Canal Committee, proceeded in a boat, decorated with

flags and accompanied by an excellent Band of Music. The interest of

the passing scene was heightened by the Boats which followed, some

laden with spectators, and others with merchandize from London. The

Inhabitants from the adjoining villages crowded to the banks, and

loudly greeted the Procession. In eight hours the whole line was

passed, and the encomiums justly bestowed on the Works must have

gratified the Engineer, (Mr. Bevan) who in three years and a half

has so happily and ably executed a Canal of 23¼ miles in length,

attended with considerable difficulties in its progress, and having

in its line two Tunnels; and several heavy Embankments. ― The

festivity of the day was concluded by a Dinner in the Town-hall at

market Harborough, at which Sir Jas. Duberly presided. ― This

Navigation completes the water-communication thro’ Leicester,

between London and the Derbyshire Canals, thereby opening new

Markets for the produce of Leicestershire, and giving a direct route

for the trade between the Metropolis and Nottinghamshire, and the

Eastern parts of Derbyshire and Yorkshire.”

The Leeds Mercury, 20th

August, 1814

Despite the jubilation that accompanied its opening, the ‘old’ Grand

Union was never a financial success due to its heavy construction

costs and reliance on traffic originating from other systems; later,

the railways were to capture most of its trade. Although the Canal and

its bridges were built wide, its locks were not due to the Grand

Junction Canal Company wishing to discourage wide boat traffic on

the lower part of its system, where its tunnels (Blisworth and

Braunston) were too narrow to permit two wide boats to pass abreast.

In 1894, the Grand Junction Canal Company bought the old Grand Union and the adjoining Leicestershire &

Northampton Union Canal, which were then on the verge of financial collapse.

The Board realised that if trade was to develop, their

Leicestershire canals needed to be improved and they commenced a programme of dredging

and ― despite the problem with tunnel width on the main line ―

alterations to permit the passage of wide boats. Other

problems to be addressed were, on the old Grand Union section, the excessive time taken to lock

through the long Watford and Foxton flights and shortage of water.

The use of inclined plane boat lifts at Foxton and Watford was an

attempt to address all three problems with a single solution ―

bypassing the narrow flights of locks using boat lifts would enable

wide boats to enter the canal

while reducing both the delay in locking and the water wasted in the process.

Designed by Gordon Cale Thomas, the Grand Junction’s engineer, the boat lift

installed at Foxton used two caissons, each capable of accommodating

a single wide boat or two narrowboats abreast, entry being through vertical

guillotine gates that created a watertight seal when closed. The

caissons, when filled with water, balanced each other. The lift,

which was

powered by a small stationary steam engine, took some 12

minutes to complete a lift compared with, at best, 45 minutes for

the passage of a single narrow boat through the Foxton flight. No

water from the upper pound was lost in the process, for what flowed

out in the downward caisson was returned in the upward. But

the Company was reluctant

to install a second lift to bypass the Watford flight ― that

at Foxton had cost £40,000 ― or alternatively widen the Watford locks.

This

defeated much of the scheme’s overall objective:

“If we have a cargo in Leeds for delivery to London, we will

presume that we start from Leeds with a short boat measuring 57 feet

6 inches by 14 feet beam [governed by lock dimensions] . . . . we

could journey by Wakefield, Barnsley, Doncaster, Keadby, Newark,

Nottingham, Loughborough and Leicester, as far as the flight of

seven locks at Watford on the Grand Junction Canal . . . . these

locks can only accommodate narrow boats, and form the remaining

obstacle to prevent us reaching London.”

Evidence from H.R. de Salis (Vice Chairman Fellow,

Morton & Clayton)

to the Royal Commission (1906).

The Foxton boat lift conveying two pairs of

narrow boats.

Although the Foxton boat lift achieved its purpose, in practice its rails

suffered excessively from stress due to the weight of the caissons. More important, the anticipated growth in traffic on the Leicester

section failed to materialise and the lift’s operating and

maintenance costs could not be justified on what there was.

After eleven years in service it was taken out of use and eventually sold for scrap

in 1928 for the princely sum of £250. Today, the Foxton Inclined Plane Trust

has cleared the site of foliage for visitors to see, their

ambitious long-term aim being to rebuild the lift.

Despite the Company’s efforts to promote the Leicester route, its

trade continued to diminish. During the 1930s, as part of

their canal improvement scheme, the Grand Union Canal Company

planned to rebuild the Foxton and Watford locks to accommodate wide

boats, but they the failed to secure the necessary government

grant. Following a brief revival during

WWII., regular trade had ceased by the 1950s leaving the waterway

almost derelict. But having managed to survive into the era of leisure boating, the waterway has

since gained a new lease on life.

――――♦――――

To

the south of Norton Junction, the Canal descends through the Long

Buckby flight of seven locks to reach the village of Whilton and the

15-mile Blisworth pound. Some 3½ miles to the south of Buckby bottom

lock lies . . . .

“Weedon, a village in Northamptonshire 8 miles NNW of Towcester.

It stands on the Grand Junction Canal and has a great ordnance depot

and barracks.”

The General Gazetteer,

Richard Brooks (1820)

The

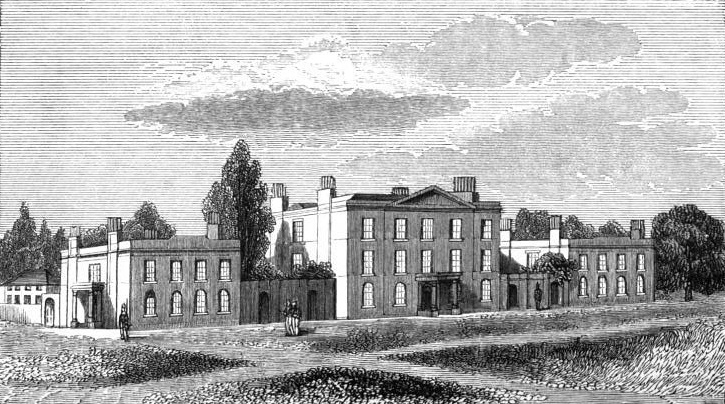

”great ordnance depot and barracks” referred to is the former

Royal Ordnance Depot, [4] a relic of the

Napoleonic Wars with their threat of French invasion.

|

“Such as been the demand for small arms for the

grand expedition, that an order has been made to the

Board of Ordnance, for 22,000 muskets to be sent from

the depot at Weedon; this requisition was received on

Saturday se’nnight [the space of seven nights and

days], and the whole was packed in cases and sent off

for London on Monday morning, by canal boats. On

this occasions nearly two companies of the Bedford

Militia, stationed at Weedon, were employed on the duty.

The arms will be replaced from Birmingham. Upwards of

120 pieces of artillery are said to be at the above

depot, with ammunition wagons, forges, &c. all in

perfect working order for immediate service.” |

|

The Hereford Journal, 9 August

1809. |

The

Depot was built following an Act of Parliament of 1803, which provided for the acquisition of 53

acres of land; this was later extended to some

170 acres. The site’s location was chosen for its considerable

distance from the potential invasion shores of the South Coast

while being well connected with other parts of the country via the

Grand Junction Canal and the Turnpike (the A5). The Depot

housed armouries, storerooms, magazines, guns

and equipment. [5] Nearby were barracks and stables for the

officers, men and horses of troops of cavalry and horse artillery. Security

was tight, the Depot being surrounded by a high wall at the corners

of which were bastions built as sentry lookouts, with patrol walks

along the top. Lodges were built at each end of the main

enclosure, each equipped with a moveable portcullis.

The barracks block at Weedon, as

depicted in Osborne's London & Birmingham Railway Guide

(1840)

In 1804, Barnes built a ⅝-mile branch to service the

new Depot. The military branch canal entered the Depot under a

portcullis, set in a building known as the East Lodge, which formed

part of the surrounding wall. The canal continued into the magazine, passing

through a further smaller building and portcullis. At the far end

was yet another portcullis leading to a barge turning area outside

the perimeter wall, but barges were also able to turn in a canal

basin within the magazine enclosure.

Above, the East Lodge and portcullis;

below, Barnes’s service canal.

Weedon Depot closed in 1965 and much of this interesting historic

relic has since been demolished; what remains is used by light

industry. Now isolated from the main line, Barnes’s branch canal

still runs through the middle of the site like a neglected

ornamental feature.

See also Appendix I.

――――♦――――

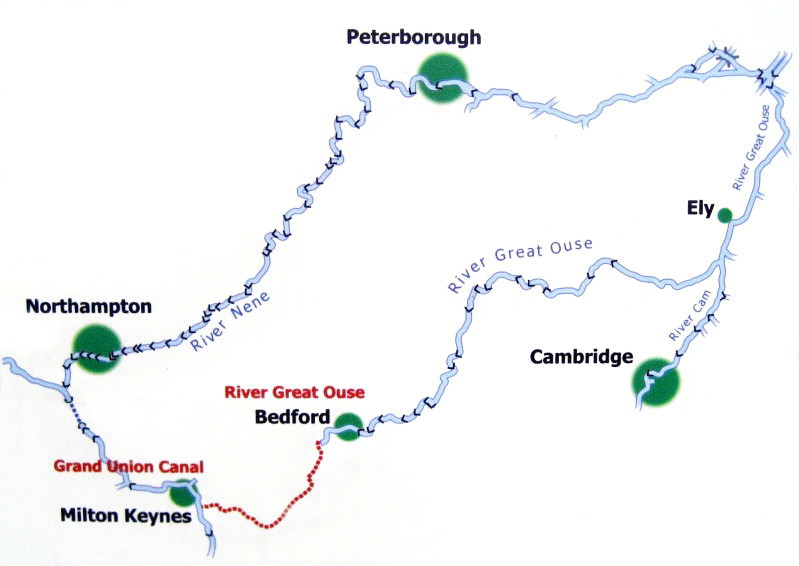

Gayton Junction

lies a

further 7½ miles to the south. Here, the

Northampton Arm heads east to the town where, at Northampton

Junction, it connects to the River Nene and onwards to East Anglia’s waterways and The Wash.

Construction of the Northampton Arm was delayed for many years

and in that respect shares a similar history to its contemporary, the

Aylesbury

Arm. Authorised in the 1793 Act and surveyed by Barnes

three years later,

the Company was reluctant to build this short link from Gayton to

the River Nene due mainly to the supply of water it would require from

the main line. [6] However, after much

protest by the town’s citizens, the Company was eventually persuaded, but to save expense Barnes was instructed to

build a

double-track horse tramway using sleepers and

rails released from the now redundant Blisworth tramway and the

completed Wolverton embankment:

“GRAND JUNCTION CANAL.―We

are happy to announce the completion of nearly all the great works

which are going on upon this important and extensive line of

navigation. On Monday morning last, the stupendous embankment

between Wolverton and Cosgrove, near Stony-Stratford, was opened for

the use of the trade. By this great work nine locks by its side,

four down and five up, are avoided, and one level sheet of water is

now formed, from Stoke Bruerne to some miles south of Fenny

Stratford (this overlooks the lock at Cosgrove), as well as on the Buckingham branch, extending to within

a mile of that town. The embankment seems to possess great

stability.

The branch and iron railway, that is to connect the Grand Junction

Canal with the New River at the town of Northampton, as also with

the Leicestershire and Northampton Union Canal, are proceeding

rapidly, and their completion may be expected about the end of next

month.”

The Morning Post, 30

August 1805

. . . . but as mentioned earlier, the Leicestershire and Northampton Union Canal

was never to reach Northampton.

Opened in 1805, the Northampton

tramway was operated by the firm of Pickfords, which relocated from

Blisworth wharves from where it had operated the hill tramway. But

that to Northampton proved unpopular, and in 1810, after much protest by the

town’s citizens, the Company agreed to construct a narrow

canal, although work on it did not commence for a further

three years. Built by Benjamin Bevan to

Barnes’s survey,

the 4¾ miles Northampton Branch opened on May 1st, 1815 to the usual

celebrations:

“On Monday May 1, was opened the Branch Canal between the River

Nene, at Northampton, and the Grand Junction Canal. The day being

remarkably fine, a great multitude of persons assembled to watch the

first arrival of the boats, several of which were laden with various

kinds of merchandise, manufactured goods &c. &c. from Ireland,

Liverpool, Manchester, Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, &c. &c. and

upwards of twenty with coals. From the greater facilities thus

afforded to trade, particularly in the article of coals, the

inhabitants of Northampton and neighbourhood may reasonably

anticipate considerable advantage. After mooring the boats, amidst

the firing of canon, different parties spent the remainder of the

day with the utmost conviviality.”

The Leicester Journal,

12th May, 1815

The limit of navigation was later extended to West Bridge, with

wharves being built to serve mills, timber and coal yards. Although a

steady trade was established, it never attained a sizeable volume due

mainly to the narrow locks that restricted the size of craft able to

use the branch.

――――♦――――

|

Southern entrance to Blisworth

Tunnel. The concrete ring (bottom left) is one of the

reinforcing liners

inserted throughout the central

third of the tunnel’s length during major repairs carried out in

1982-84. |

The village of Blisworth lies just to the south of Gayton

Junction. The canal reached Blisworth from the north in

September 1796, but it was not until the Blisworth Tunnel was opened

in 1805 that a direct link with the south was established. In

the intervening period, Blisworth Wharf, operated by Pickfords

among others, became the busiest inland port in England.

Pickfords was already an established London-based road carrier when, in 1778,

the firm began to convey goods by barge as well as by wagon.

At this time the firm’s operations were being conducted by 50

wagons, 400 horses and 28 barges, and by 1800 they had added 8 canal

depots. In 1803 their canal services reached

Birmingham, and the firm went on to establish warehouses and wharves

at London (City Road and Paddington) and at Brentford. They advertised two classes of

services:

-

‘fly boats’ travelling day and night with two steerers and two

drivers (for the horses) at 3 to 3½ mph, covering 40-miles a day

in stages, with fresh horses at each stage;

-

by barge at 25 miles per day, with two men resting at night.

An

article on canals in Rees’s Cyclopedia of 1805 praises

Pickfords fly boat services “which travel night and day, and arrive

in London with as much punctuality from the midland and some of the

most distant parts of the kingdom, as the waggons do.”

During construction of the Blisworth tunnel, the village became a

transhipment terminal for the goods being

carried road over Blisworth Hill to the Northampton to Old Stratford

turnpike. Land was taken by Messrs. Barnes (he of the Canal), Roper & Co.

and rented

to canal carriage companies, including Pickfords, on which to erect warehouses.

However, the Grand Junction Canal Company received intelligence that

their Resident Engineer was lining his pockets to

their detriment; worse still,

“. . . . that Roper and Barnes having no inconsiderable weight in the

Councils of the Directors, it is probable that the navigation may

stop at Blisworth many years, possibly for ever”. [7] And so the

Company’s Northern Committee, which included the Marquis of

Buckingham, “. . .

thought it their duty, in consequence of some complaints, to

navigate the Canal from Braunston to Blisworth, and to enquire into

the state of the Company’s concerns in that part of the line.”

Their inspection found all to be above board,

and that “. . . the part Mr. Barnes has

taken in this concern has been with the purest and best motives; and

that the Company have derived a very considerable emolument from his

exertions”. [8]

But road communication across Blisworth Hill proved

unsatisfactory, and so the pioneer rail engineer Benjamin Outram was

employed to construct a double-track, horse-drawn tramway. The

tramway was in operation by mid 1800 and remained in use until the

tunnel was opened to much celebration and the customary

dinner in 1805:

“THE GRAND JUNCTION

CANAL – That grand line of

communication, between the metropolis and the most distant parts of

the kingdom, which the Grand Junction Canal was to effect, was

incomplete till Monday last, owing to a range of high land between

Stoke Bruerne and Blisworth, in Northamptonshire, not being

penetrated by a tunnel or arch, as intended; but all goods coming

past that place, have been obliged to be unloaded, and placed on

waggons, and conveyed on a railway over the hill, to be embarked

again in other boats.

On Monday morning, the weather proving very fine, an amazingly large

concourse of people were assembled, some of them from considerable

distances, to view the stupendous works at Blisworth Tunnel, and to

see the grand procession in honour of the opening of this internal

communication by water, between the most distant places. One of the

Paddington packet-boats, called the Marquis of Buckingham, was the

first boat which went through the tunnel. The principal company

retired to the Bull Inn, at Stoney Stratford, and, about six

o’clock, 120 proprietors and friends of this grand undertaking, sat

down to an excellent dinner. Mr. Praed in the chair.”

Morning Chronicle, 30th

March, 1805

There being no further use for the railway, it was dismantled and

the materials reused in the construction of the Northampton tramway.

Horse tramway (or plateway).

――――♦――――

The

Blisworth tunnel ― 3,056 yards in length ― lies to the south of the

village and is approached at both its ends through substantial

cuttings. There is sufficient width within the tunnel for narrow

boats to pass, but not wide boats. The tunnel has no tow path;

the barge

horses were led over Blisworth Hill while the boat crews ‘legged’ through.

|

|

Walking the barge

horse over Blisworth Hill. On the right is a

ventilation shaft ―a former ‘pit’, built to service the tunnel while it was

being built. A number of them

were afterwards extended into the chimney-like

structures seen today. |

In the age preceding mechanical propulsion, where a tunnel did not

have a tow path one method of

propelling a boat through was by the use of human legs placed

against the tunnel roof or (in the case of the Braunston and

Blisworth tunnels) the walls. This practice, known as

‘legging’, required two people to perform. Each lay at

opposite ends of planks (‘wings’) placed across the bows of the boat.

Holding

the plank with their hands, they then walked the boat along using their feet

against the tunnel walls. Professional

leggers were available, who in the early days of the Canal sometimes

terrorised the boatmen into employing them, which led to complaints

about:

“. . . the nuisance arising from the notoriously bad characters

of the persons who frequent the neighbourhood of the Tunnels upon

the plea of assisting Boats through them.”

Grand Junction Canal Company Minute Book, 10th

November, 1825

Eventually, in 1827, the leggers were registered and employed by

the Company who issued them with brass armlets for identification. They

were paid a standard rate of 1s 6d for a single trip, Blisworth men

working south and Stoke Bruerne men north. In 1859, the novelist

Charles Dickens commissioned John Hollingshead to write a number of

travel articles to appear in the periodicals that Dickens published.

Among them is an account of a journey that Hollingshead made along

the Canal, which includes a description of legging a narrow boat

through Blisworth Tunnel (Appendix

II.).

Above: fitting the wings (or legging boards).

Below: legging.

When steam tugs appeared in 1871, the professional leggers were made

redundant; this from the Company’s Minute Book:

26th April 1871: Mr Mercer reported that a tug was now at work at

the Braunston Tunnel and that the same charges were being made as at

the Blisworth Tunnel viz: Boats with cargoes of 25 tons or upwards

each, 1/6d each way. Boats with cargoes of under 25 tons, 1/3.

Empty boats 1/-. And that the services of the leggers would no

longer be required . . . Resolved that a weekly allowance of 5/-

each be made to [former leggers] Mr Benjamin, 75 years of age

and 44 years at the tunnel. R Thomas, 65 years of age and 38

years at the tunnel and John Fox 64 years and 19 years at the

tunnel.

But the new steam tugs were not universally welcome:

6th June 1871: Letter from Mr Cherry reporting that some of the

boatmen refused to avail themselves of the Tugs in use at the

Blisworth and Braunston Tunnels . . . . Resolved that all boats

using Blisworth and Braunston Tunnels between the hours of 4 am and

8 pm be hauled through the same by the Company’s tug at the

following scale of charges viz: Boats with cargoes of 25 tons or

upwards, 1/6d each way. Boats with cargoes of under 25 tons, 1/3. Empty boats 1/-. Any boatman refusing to have his boat so hauled be

charged a sum not exceeding one penny per ton for the weight on

board.

The introduction of steam propulsion was not without other problems. Ten years earlier, two fatalities had occurred:

27th September 1861: The chairman reported that on the 6th inst

an accident had occurred on board one of the Company’s steam boats

in the Blisworth Tunnel, by which two men, Webb and Edward Broadbent

had been suffocated and two men severely burnt and that every

possible attention had been given to the men injured who were now in

the Northampton Infirmary and that the sum of £45 had been given by

the Company to the widows of the deceased persons.

The need for better ventilation led to the uncovering of some of the

‘pits’ that had been sunk during the tunnel’s construction; seven of

the nineteen originally built are now used for this purpose, the

others have either been capped or filled in. A heavy build-up of

soot on the tunnel brickwork was another problem associated with

steam propulsion, which led to the introduction of a ‘brushing’

hopper. Fitted with a curved brush that matched the tunnel’s

profile, the craft was towed through the tunnel, its brush sweeping

the soot from the brickwork into the hopper.

Horse-drawn traffic continued on the Canal until well into the 20th

century, necessitating a continuing need for tugs:

“Although the old horse-drawn boats are rapidly being replaced by

motor-driven craft, the Canal Company still maintains a regular

service of tugs for the towage through the tunnel [Blisworth and

Braunston] of craft which cannot proceed under their own power. At Blisworth the Company has a warehouse of five storeys, for the

storage of goods of all kinds.”

From a Grand Union Canal Company publicity article

(1937)

The “regular service of tugs” was withdrawn in the following

year.

The

village of Stoke Bruerne lies a short distance from the southern end

of Blisworth Tunnel. When the canal reached Stoke from the south in

September 1800, this village also became a busy

transhipment terminal for canal goods conveyed over Blisworth

Hill on Outram’s horse-tramway. Today, Stoke is known for its Canal

Museum. Founded in 1963 by Charles Hadlow, an engineer, and Jack

James a boatman turned lock keeper, it was the first museum devoted

to our inland waterway heritage, although it has since been joined

by others at London (Battlebridge Basin), Gloucester and Ellesmere Port.

――――♦――――

From

Stoke the canal descends through a flight of seven locks to reach

its next level, the 5½-mile Cosgrove pound; only the lock at

Cosgrove separates it from the adjoining Fenny pound.

|

The main line descends through

Cosgrove Lock (No. 21) on the left. To the right is the remnant of

the branch to Stony-Stratford and Buckingham,

now used as moorings.

Rails set into the towing path signify that

Cosgrove

once exported sand and gravel, the

worked out pits (now flooded) being visible from Cosgrove

embankment. |

The

main line passes through Cosgrove village, following

the right bank of the Tove to near its confluence with the Great

Ouse. A public wharf was established about half a mile north

of Cosgrove, where the road to Castlethorpe crossed the canal.

This is Castlethorpe Wharf (a.k.a Thrupp Wharf), and it hosts a

public house, the Navigation Inn. When the Inn was put up for

sale in 1876, the wharf was described thus:

“The excellent WHARF-YARD, with landing for tying-up eight boats;

coal and coke yards, lime-kiln, capital warehouse (capable of

storing 150 quarters of corn), salt-house, granaries,

weighing-house, with weighing machine; stabling for eleven horses,

lock-up coach-house, large barn, with slated roof; piggeries,

excellent walled kitchen garden, and other appurtenances thereto

belonging. There is a COTTAGE, containing three rooms,

Adjoining, which is now used as a warehouse. And also all the CLOSE

of first rate Arable LAND, containing 9¾ Acres, or thereabouts,

adjoining the before mentioned Property, and fronting the road

aforesaid; together with A CLOSE of excellent Pasture LAND,

containing 11½ Acres, or thereabouts, adjacent thereto, with good

thatched hovel, and appurtenances created thereon, the whole being

now in the occupation of the said John Ayres.”

Cosgrove lock (No. 21) lies at the junction with the former Stony

Stratford and Buckingham

Arm. Authorised in the Grand Junction Canal Act of 1793 and

originally planned as a short branch to Old Stratford and the busy

highway of Watling Street (the A5), the Arm was soon extended a further 9¼-miles to Buckingham,

[9] principally at the instigation of

the Marquis of Buckingham who loaned the Company the construction

cost:

“The branch of the Canal from Buckingham to the Grand Junction

Canal was opened this day with great rejoicings. A barge with the

Marquis of Buckingham, Mr. Praed, and Mr. Selby (Gentlemen of the

Committee) and Mr. Box, the Treasurer, accompanied by a large party

of Ladies and Gentlemen, and a band of music, led the way to the

procession of 12 barges, laden with coal, slate, and a variety of

merchandise. Upon their entrance to the basin at Buckingham they

were saluted by the firing of several cannon. A numerous party were

handsomely entertained by the Marquis of Bath at the ‘Cobham Arms

Inn’ on this occasion, and a liberal supply of beer was given to the

populace. This branch of the Canal, 9¼ miles in length, has been

completed in about eight months, and will secure to an extensive

distance of country most substantial benefit.”

The Gentleman’s Magazine,

1st May 1801

As elsewhere, water-borne transport was to have a

considerable impact on the town and its locality. Coal, stone,

bricks, manufactured goods, imported produce from London Docks were

all more readily available at much lower cost than ever before; and

local produce could be moved faster and more easily, whether it was

foodstuffs to the local market, or loads of hay and straw

destined to nourish and sustain the motive power of the Metropolis. Within a few years, trade on the branch had

reached 20,000 tons per annum and was to remain at this level for

almost fifty years.

The first section of the Arm to Stratford was, in common with the

main line, built as a wide canal, but the extension to Buckingham

was built narrow. Its route led over easy ground, only two locks

being required, so construction progressed quickly. In its early

days the Arm was successful, but from the 1850s

railway competition led to its decline, which was further aggravated

by leakage and by Buckingham Corporation using it as a dump

for the town’s sewage, which caused silting. By 1904, Bradshaw’s Guide was

describing its upper section as being “barely navigable” and

by the 1930s the Arm was derelict. All that now remains is a section

of about 100 yards, which extends westwards above Cosgrove lock and

is used for moorings. The remainder of the canal has been filled in,

although there is an ambitious restoration scheme, the Patron of

which is the present Speaker of the House of Commons.

|

A relic of the Canal’s horse

drawn days, the Cosgrove horse tunnel

enabled barge horses to

be led under the Canal to the stables. |

――――♦――――

Immediately to the south of Cosgrove lock, the Canal crosses the

valley of the Great Ouse on a substantial mile-long embankment:

“All the works of that extensive and complicated undertaking, the

Grand Junction Canal, are now completed. The stupendous

embankment that had been raised between the villages of Wolverton

and Cosgrove, near the market town of Stony Stratford, has been

lately opened for the use of trade and internal navigation. . . .

The arches erected under this embankment, to create a passage for

the river Ouse, which arches were believed and reported to be in a

sinking state soon after the central arches were struck, are at

present considered as sufficiently firm, and the embankment is

thought to possess all imaginable strength and durability.”

The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure,

July-Dec, 1805

Reference to the “arches were believed and reported to be in a

sinking state” refers to the three arches of a brick-built

aqueduct, designed by Jessop, which carried the embankment

over the Great Ouse. When the timber shoring was removed the

aqueduct began to show signs of failure . . . .

“After its erection Mr. Bevan, the engineer, of Leighton Buzzard,

being called upon, gave it as his opinion, it would not stand twelve

months; his prediction was verified, for in less than six months

after its construction, the materials were so indifferent, that a

continued leak of the aqueduct was observable.”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819,

John Hassell (1819)

The embankment had experienced slippage in 1806, shortly after its

opening. This was repaired, to be followed in February 1808 by

failure of the aqueduct:

“On Friday morning last the inhabitants of this town were thrown

into the utmost consternation, by information which arrived from

Wolverton, that the large embankment for carrying the new line of

the Grand Junction Canal across our valley, about a mile below this

town, had fallen in; and that the river Ouse was so dammed up

thereby, that this town must shortly be intirely inundated to a

great depth. I hastened to the spot, where my fears were very much

allayed, by finding that one of these arches, which had been propped

up underneath with timber, soon after the centres were removed, was

still standing; and that this one arch, owing to there being no

flood in the river, was able to carry off the water of the river as

fast as it came down. On examining the other two arches, I found

that about 22 yards in length of the middle part of each had fallen

in, and blocked up the arches, laying the canal above in complete

ruins, emptying it as far as the nearest stop-gate on each side, and

exposing the remains of 500 quarters of coke and cinders which the

contractors had lain in the arches. The ends of each of the broken

arches were found standing in a crippled state. Most fortunately for

the Public, as well as the Company, the old line of the canal and

locks across the valley are still remaining, and in sufficient

repair, immediately to convey the barges, and prevent interruption

to trade: but the loss of £400 per month, which I am told has of

late been the amount of extra tonnage received by the Company for

goods passing over this embankment, will be lost to them during the

period of re-building the arches and repairing the canal over them.”

Jackson’s Oxford Journal,

27th February, 1808

A subsequent investigation attributed the aqueduct’s failure, not to

deficiency in Jessop’s design, but to poor workmanship on the part

of the contractor. The legal dispute with the contractor that

followed was settled in the Company’s favour, with damages being

awarded for loss of trade and the cost of the replacement. Today,

the Great Ouse is bridged by Benjamin Bevan’s iron trunk aqueduct of

1811:

“The new aqueduct bridge of the Grand Junction Canal, over the

Ouse River, below the town of Stoney Stratford at Wolverton, which

has been for some time in preparation, of cast iron, in lieu of that

of brick, which fell down in 1808, was on 22nd January, at one

o’clock, opened for the passage of boats, the Empress,

belonging to Mr. Pickford, and his Queen Charlotte, being the

first of 30 which passed this first metal aqueduct that has been

constructed anywhere in the South of England. ― The whole length of

the iron-work is 101 feet; it is wide enough for two boats to pass

each other, and has a towing path of iron attached to it; it is firm

and tight in every part. Mr. Benjamin Bevan, the Engineer who

designed it, and about twenty persons only besides the boatmen were

present, no announcement having been made of its completion. The

opening of this Aqueduct and the passage of trade over the

embankment, will, it is expected, add full £500 per month to the

revenues of the Company.”

The Tradesman Vol. VI.,

Jan - June, 1811

Benjamin Bevan’s cast iron

trunk aqueduct of 1811.

――――♦――――

The

Canal now enters Wolverton, the first town of any size on its

southward journey. Wolverton was once home to the London and

Birmingham Railway Company’s locomotive works before this was transferred to

Crewe, after which Wolverton Works concentrated on the manufacture

and repair of rolling stock. At Wolverton, the Canal passes

under the former London and Birmingham Railway ― which Robert

Stephenson conveyed across the Ouse Valley on a fine brick-built viaduct

(1838) ― before crossing Grafton

Street on the New Bradwell aqueduct (1991). It then commences a

circuitous journey around the eastern outskirts of Milton Keynes,

during which it becomes a travelling companion to the River Ouzel [10] until their paths

eventually diverge at Grove Lock, to the south of Linslade.

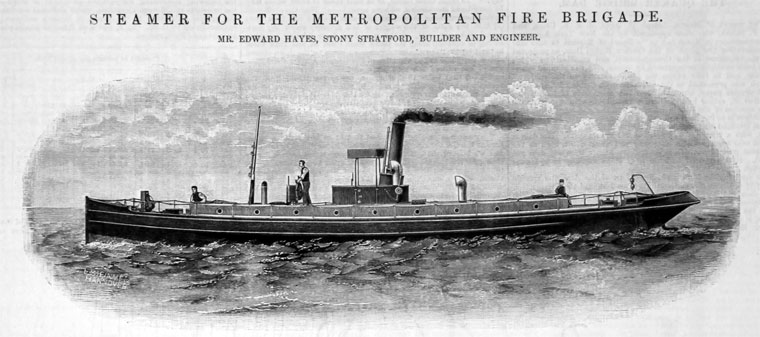

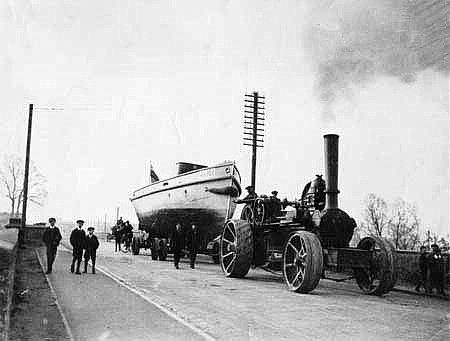

Stony Stratford lies to the south-west of the canal at Wolverton.

Here, at

‘Watling Works’, the engineering firm of Edward Hayes was once

located. Although originally in the agricultural engineering business,

the firm was to make its mark in boat-building, not canal boats, but

steam boats of various descriptions for

coastal and harbour work ― and this despite being some distance from

the Canal and many miles from the sea:

“In 1845 the late Mr. Edward Hayes started the works for general

engineering, but gradually the business has become confined to the

building of steam yachts, tugs and launches. These are exported to

all parts of the world for steamers and machinery of various

descriptions have been built for the British Admiralty, Crown Agents

for the Colonies, the Board of Works, Trinity House Pilots, the Shah

of Persia, the Sultan of Morocco, besides various foreign

governments and well-known shipping lines. During the late

South African War a little steamer destined to work in connexion

with the landing of troops and stores actually steamed from the

place she was launched, the Old Stratford Wharf, which is a branch

of the Watling Works, along the Grand Junction Canal to the Thames

and thence to Delagoa Bay, South Africa.

In Stony Stratford it is not an unusual sight to see one of these

steamers being drawn on large eight-wheel trolleys by a powerful

traction engine from the Watling Works, where they are built, to

the wharf half a mile away, and often followed by its engine and

boiler on separate trolleys . . . . The steamers originally built

for the riverside work of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade came from

the Watling Works, and the present Mr. Edward Hayes has taken out

numerous patents for improving steamers, one of the most recent

being for cheapening and facilitating the exportation of small

steamers abroad, making it possible to erect steamers at the site of

their work and where only unskilled native labour can be obtained.”

The Victoria History of Buckinghamshire

(1908)

The steamer that sailed to South Africa was the 65ft Curlew.

Built

in 1902 and launched into the Canal, she then set off for London, grounding on a

shoal at Leighton Buzzard en route from which she was hauled by

a team of horses. Having reached the Port of London under her own

steam and successfully completed her trials, she then sailed on to

her overseas customer. The larger of Hayes’s vessels built for

export were prefabricated.

The firm ceased boat-building in 1923 due to the glut of small

war-surplus vessels on the market, but at least one of their craft

survives. Following her retirement from the Thames Water Conservancy

Board, the river tug Wey (originally named Pat) was repatriated and

is now on display at Milton Key Museum.

――――♦――――

|

|

|

Newport Pagnell

Canal: charges authorised under its Act |

At

Great Linford the canal approaches the M1 (north of junction 14) and

the site of the junction with the former short ― and

short-lived ― Newport Pagnell Canal (1¼-miles). As with the Aylesbury and

Northampton arms, the Grand Junction Canal Company were unenthusiastic about building

this branch,

the view being that as Newport lay close to the

main line there was nothing to justify a branch. But the citizens of

the town disagreed. In 1813, after some years of fruitless argument,

they decided to promote the branch themselves while harbouring the

grander ambition of extending it eventually to Olney, Bedford and

beyond. Benjamin Bevan surveyed the line, an Act was obtained in

1814, work commenced in 1815, and the canal, built as a broad canal,

opened early in 1817.

During its comparatively short life the Newport Pagnell Canal

remained in the ownership of its promoters, and while their grander

ambitions were unfulfilled, the Canal did pay a modest dividend

throughout most of its life. In 1864 the Canal was bought by the

Newport Pagnell Railway Company who used part of it for their track bed. [11]

Proposed canal linking

the Great Ouse at Bedford with the Grand Union Canal at Milton

Keynes.

Bedford and

Milton Keynes Waterway Trust.

――――♦――――

Fenny pound extends for 11½-miles from Cosgrove lock southwards to

Fenny Stratford. Located just to the east of Watling Street (the

A5), Fenny Stratford lock provides the unusually small rise of 12 inches, for it was never intended to form a permanent

feature of the canal. Its purpose was, as a temporary measure, to

control leakage through the uppermost part of the canal banks in

Fenny pound by reducing the water level. The problem

was addressed in 1802, but although the Company considered removing the

lock on more than one occasion, they were deterred by the cost and

disruption to canal traffic, and the ‘temporary’ lock lives on.

The Canal was opened to Fenny Stratford in 1800, the event attracting

public celebration and ending with the customary dinner for the Company

hierarchy:

“The Grand Junction Canal was on Wednesday opened for barges from

the Thames at Brentford, to Fenny Stratford, and early in the

morning a number of boats started from Tring, at which place the

canal has been completed these two years past; about one o’clock

they passed through Leighton; and a short distance before they

reached Fenny Stratford the Marquis of Buckingham, accompanied by a

number of friends and principal proprietors, attended by the band

and a party of the Buckinghamshire Militia, met them. They then went

in grand procession to Fenny Stratford, where they were received

with firing of cannon belonging to the town, and other

demonstrations of joy. The Marquis and the proprietors retired to

the Bell Inn to dinner.”

Jacksons Oxford Journal,

31st May, 1800

By the 1930s, regular local trade on the Canal appears to have

mostly died out on the section of the Canal north of Berkhamsted,

with Grand Union Canal Company publicity material of the period

identifying very few of the wharves with tenants. Of those that

are listed, most are located along the section from Fenny Stratford

to the Leighton area:

|

|

|

Grand Union Canal Company

route map, c.1938. |

“At this point thousands of tons of

Leighton sand are loaded from the adjoining pits . . . and taken by

canal boat both to Paddington and Brentford for distribution to all

parts of London. Mr L. B. Faulkner, one of the long distance canal

carriers, has his depot and boat repairing yard at Leighton Buzzard.

. . . At Fenny Stratford, quantities of farina

[12]

and sugar are landed from steamers in the River Thames.”

Grand Union Canal Company

publicity material,

c. 1938

The farina and sugar referred to was probably destined for Valentin, Ord

and Nagle, a tenant listed at Fenny Stratford wharf who manufactured brewing sugars from grain brought in by

narrow boat.

Before the Canal reached Leighton, the deposits of sand in the

locality had been used by building firms and in tile-making,

but the Canal’s arrival opened up a much

wider market. Local hauliers transported the sand from quarries

for loading into barges at canal-side wharves, from where it was

shipped to London and to the Midlands. But the constant

passage of carts through the town caused such damage to the roads

that the Council demanded that the sand firms set up an alternative

form of transport. This led, in 1919, to the building of the

2ft gauge Leighton Buzzard Light Railway. Constructed from war surplus

materials and equipment, the railway became the main means of moving

sand from the quarries in the north of the town to its southern

outskirts where the grading and washing sheds were situated and from

where there was good access to the Canal and the mainline railway. But transport by canal and rail declined in the years following the

Second World War, for road haulage could deliver faster and more

directly. From the 1950s onward, Leighton Buzzard became home to

many road haulage firms specialising in the transport of building aggregates,

while the light railway has become a popular attraction for tourists

and those with an interest in the industrial narrow gauge.

Brantom’s Dock (with

towing path bridge) in

operation ― and following its transformation into an office

block.

Linslade hosted a number of wharves. Sandhole Bridge had

wharves that served the sand quarries of Heath & Reach.

Whichello’s Wharf, named after Stephen Henry Whichello and Son, coal

merchants, was situated to the north of the busy Leighton Road bridge

and on the west bank of the canal. To the south of the bridge, on

the opposite bank, was the dock of Grant and Lawson, later known as Brantom’s

Dock.

Both served as

coal yards, timber yards, agricultural machinery suppliers, brick

and tile manufacturers, etc., and they undoubtedly attracted industry

and commerce to this new part of the town. [13] Both wharves had rectangular basins perpendicular to the canal for

loading and discharging, with various warehouses, offices and other

buildings set around. In 1974 the basin serving Brantom’s

Wharf ― by then choked with weeds and mud ― was filled in to make a

car park, but its attractive towing path bridge was preserved

through the efforts of the Leighton Buzzard Preservation Society.

Traces of another of the canal-side wharfs, Garside’s Wharf, also

exists complete with its semi-inset 2ft-guage railway track. This

line was not part of the Leighton Buzzard Light Railway, but served Grovebury Quarry and connected with other tracks serving quarries

and works in the area to the south of the Linslade to Dunstable

railway branch, and east of the Canal. It appears to have been

horse-operated at first but later used locomotives. The last

boatload of sand was shipped from the wharf in 1965.

――――♦――――

The three locks at Soulbury.

One of the ‘northern engines’ pumping stations is on the right.

At Fenny Stratford the

Canal begins its gradual ascent to Tring summit, and over the next 16½ miles ― much of it in company with the River

Ouzel ― it negotiates a further 14 locks [14] rising

by 105ft. Within this section there is an attractive flight of three

locks at Soulbury together with an old steam pumping house, one of

what became known as “The Northern Engines”.

Ensuring an adequate depth of water was always at the forefront of

the canal builder’s mind, particularly at summits where recourse to

steam pumping from reservoirs was often necessary. Even then,

prolonged drought could bring traffic to a near

standstill, and there are records of the cost of pumping coupled

with the

decline of traffic due to low water making a substantial dent in the

Company’s profits (referred to in

Chapter XIV). In 1838, to help alleviate this problem, the Company awarded a contract to Grissell and Peto to build nine

engine houses and culverts between Fenny Stratford and Marsworth,

the aim being to pump lockage water back up the canal from the

valley of the Ouzel to the Tring reservoirs. By 1841 the

engines were in operation and capable of pumping water around seventeen

locks. The Soulbury pumping station ― to the right in the

picture above ― is one example, that at Seabrook [15]

another and particularly attractive in having been fortunate to

retain its yellow

brick chimney.

|

|

|

Seabrook pumping

station |

――――♦――――

At Marsworth Junction, the Aylesbury Arm branches off to the west.

Construction of this narrow canal was authorised by the 1794 Act (together with its

contemporary, the Northampton Arm), but the Company was reluctant to

build it due in part to their concern about the quantity of water

that it would draw from the main line.

Henry Provis was appointed

Engineer, construction commenced in 1813 and the

branch was opened in either 1814 or 1815 ― oddly, there seems to be

no reliable record of exactly when. In its 6¼-mile journey, the Arm follows a

fairly

straight path across the Vale of Aylesbury, descending 95ft through

16 locks (the first two at Marsworth being a ‘staircase’ [16])

to its terminus to the south of Aylesbury town centre.

Initially the Arm was very busy, being used to transport grain,

timber, coal and building materials, but competition from the

Cheddington to Aylesbury railway, which opened in 1839, followed later in

the century by the arrival at Aylesbury of the Metropolitan Railway, led to

its decline. By the Second World War trade had become

spasmodic and the last regular delivery of coal to Aylesbury by

canal was in

1964. In the 1960s British Waterways considered the Arm for

closure, but its fortunes revived with the growth

of leisure cruising. Aylesbury Basin now hosts a marina and

is currently at the heart of a major town-centre redevelopment

programme. The Arm is also very popular with fishermen.

A more detailed account of the

AYLESBURY

ARM.

Turning into the Aylesbury Arm

at Marsworth Junction (looking south). Marsworth Wharf is on the right.

|

Marsworth Junction and the

entrance to the Aylesbury Arm.

The silo on the right

marks the site of the former British Waterways plant for manufacturing

concrete piles used for bank protection.

The wharf site has now been cleared and

is awaiting redevelopment. |

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

WEEDON ORDNANCE DEPOT

from

The History of Northampton and its Vicinity,

(Pub. James Birdsall, 1831)

WEEDON or Weedon Beck,

formerly called Church Weedon, but now generally Weedon Royal, from

the barracks and depot erected there; it is bounded by Nether

Heyford on the east, Dodford on the north, Everdon on the west, and

Stow with Farthingstone on the south.

The works of this depot commenced about the year 1805, and consist

of barracks originally intended for two troops of horse artillery

but now capable of containing 500 infantry; they are strong

buildings of brick erected in the form of a square; near them is a

handsome hospital. Upon an eminence contiguous to the barracks is a

most elegants edifice, consisting of a centre with corresponding

wings, built of white brick intended as a residence for the officers

of the ordnance department; which is said to have cost £18,000 in

erecting.

There are eight store-houses, four being built on each side of the

arm ot the Grand Junction Canal, which runs by this place, and a

proportionate number of work shops for the artificers. The upper

rooms of these store-houses are capable of containing 240,000 stand

of small arms, which are placed under the charge of a store keeper.

The lower rooms are appropriated for field artillery, and may be

generally computed as containing about twenty four brigades, of six

guns each, with all necessary stores, ready for service at the

shortest notice; these are under the superintendency of a field

train commissary. At an extremity of the canal branch, in an

enclosed square, completely detached from the other buildings, are

four powder magazines, one of which contains nearly 70,000 rounds of

ammunition for the field pieces; the remaining three are adapted for

powder and small arms ammunition, containing, when filled, about

5,000 barrels each. Alternately is a magazine and traverse, of equal

altitude filled with earth for the purpose of preventing extended

damage in case of explosion.

Weedon has been considerably enlarged and improved within these few

years, and now contains several neat dwelling houses some of them

being residences for officers &c attached to the depot. The quantity

of ground purchased by government for this establishment is about

170 acres.

OSBORNE'S GUIDE TO THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

(1840)

The Royal Military Depot stands on a slight eminence, and consists

of a centre and two detached wings, with lawn in front; these form

the residence of the governor and officers, while for the common men

there are barracks on the top of the hill, capable of containing

500. At the bottom of the lawn there are eight store houses

and four magazines, adequate to contain 240,000 stand of small arms,

with a proportionate quantity of artillery and ammunition; there are

also a number of workshops for the military mechanics and a hospital

capable of accommodating 40 patients. In consequence of the

establishment of the railways, this one military force is rendered

so efficient and such power is afforded of presenting itself when

ordered by the civil authorities, in any portion of England, in the

course of a few hours, that the inutility of a number of these

expensive establishments will doubtless soon begin to attract public

attention. A troop of a few hundred men can be forwarded by

railway from this central depot to any important part of the kingdom

where their services might be required with a magical celerity and

precision that would be quite adequate to prevent mischief. A

small force permanently stationed here for such emergencies would

certainly be much more efficient than our present very numerous but

straggling military establishments, to concentrate the forces from

which, without marching to the scene of action, would often take a

much longer time than is needed in having a troop from Weedon to any

of the important districts.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX II.

ODD JOURNEYS IN AND OUT OF LONDON

by

JOHN HOLLINGSHEAD

(1860)

A journey through Blisworth Tunnel

The boatmen were preparing for the passage of the Blisworth tunnel

(nearly two miles in length), an underground journey of an hour’s

duration. The horses were unhooked, and while standing in a group

upon the towing-path, one of the child drivers, a girl about six

years of age, got in between them with a whip, driving them, like a

young Amazon, right and left; utterly disregarding the frantic yells

of a dozen boatmen, and nearly half a dozen family-boatmen’s wives. At the mouth of the tunnel were a number of leggers, waiting to be

employed; their charge being one shilling to leg the boat through. We engaged one of these labourers for our boat to divide the duty

with one of our boatmen; while the youth went overland with the

horse. A lantern was put at the head of the boat; the narrow boards,

like tailors’ sleeve-boards, were hooked on like projecting oars

near the head; the two legging men took their places upon these

slender platforms, lying upon their backs; and, with their feet

placed horizontally against the wall, they proceeded to shove us

with measured tread through the long, dark tunnel.

The place felt delightfully cool, going in out of the full glare of

a fierce noon-day sun; and this effect was increased by the dripping

of water from the roof; and the noise caused by springs which broke

in at various parts of the tunnel. The cooking on board the boats

went on as usual, and our space being confined, and our air limited,

we were regaled with several flavours springing from meat, amongst

which the smell of hashed mutton certainly predominated. To beguile

the tedium of the slow, dark journey— to amuse the leggers, whose

work is fearfully hard, and acts upon the breath after the first

quarter of a mile, and above all to avail themselves of the

atmospheric effects of the tunnel, the boatmen at the tillers nearly

all sing, and our vocalist was the captain’s straw-haired son.

If any observer will take the trouble to examine the character of

the songs that obtain the greatest popularity amongst men and women

engaged in heavy and laborious employments, he will find that the

ruling favourite is the plaintive ballad. Comic songs are hardly

known. The main secret of the wide popularity of the ballad lies in

the fact, that it generally contains a story, and is written in a

measure that fits easily into a slow, drawling, breathtaking tune

which all the lower orders know; and which, as far as I can find,

has never been written or printed upon paper; but has been handed

down from father or mother to son and daughter, from generation to

generation, from the remotest times. The plots of these ballad

stories are generally based upon the passion of love; love of the

most hopeless and melancholy kind; and the suicide of the heroine,

by drowning in a river, is a poetical occurrence as common as

jealousy.

There may have been a dozen of these ballads chanted in the

Blisworth tunnel at the same time; the wail of our straw-haired

singer rising above the rest. They came upon our ears, mixed with

the splashing of water, in drowsy cadences, and at long intervals,

like the moaning of a maniac chained to a wall. The effect upon the

mind was, in this dark passage, to create a wholesome belief in the

existence of large masses of misery, and the utter nothingness of

the things of the upper world.

We were apprised of the approach of another barge, by the strange

figure of a boatman, who stood at the head with a light. It was

necessary to leave off legging, for the boats to pass each other,

and the leggers waited until the last moment when a concussion

seemed inevitable, and then sprang instantaneously, with singular

dexterity, on to the sides of their boats, pulling their narrow

platforms up immediately after them. The action of the light in

front of our boat produced a very fantastic shadow of our recumbent

boatman-legger upon the side wall of the tunnel. As his two legs

stuck out horizontally from the edge of the legging-board, treading,

one over the other, against the wall, they threw a shadow of two

arms, which seemed to be held by a thin old man — another shadow of

the same substance — bent nearly double at the stomach, who worked

them over and over, as if turning two great mangle-handles with both

hands at the same time. |