|

|

FOREWORD

In Tring, malting barley, straw plaiting, silk throwing, canvas

weaving, iron-working, vehicle body building, coaching inns, the

construction of canal craft (at Gamnel) and of lock gates (at Bulbourne) and the

manufacture of coal gas (The

Tring Gas Light & Cole Company) are some of the businesses that over the

years have come, and have gone.

Tring recently reacquired a brewery to replace the

several – if pub brewing be included – that once existed in the

town, while the sewage works at Gamnel can trace its roots back at

least 140 years. [1] This leaves just one important

and long-established business, grain milling. Milling has taken place at Gamnel for over two centuries,

longer if an earlier watermill that is known to have existed in that

locality is included. The following account is,

therefore, the story of Tring’s oldest continuous business, the

manufacture of flour.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks go to Mrs Heather Pratt, grand-daughter of William Mead

of Tring Flour Mill, and to Miss Catherine Bushell, whose father and

uncle were proprietors of the Tring Dockyard, for allowing me to use their

family photographs and papers. I am also grateful to Paul

Messenger, Manager of Heygates’

Flour Mill, for an interesting and informative tour of the mill and

its packaging plant (also for

some free samples of the product) and to Wendy Austin for her help

with research and editing.

Ian Petticrew

April 2017

――――♦――――

CONTENTS

THE NEW CANAL AND

GAMNEL WHARF

THE GROVER FAMILY

THE MEAD FAMILY

STEAM-POWERED MILLING

WIND MILLING GIVES WAY TO

ROLLER MILLING

THE MILL UNDER WARTIME

CONDITIONS

HEYGATES ACQUIRES THE

BUSINESS

TRANSPORT

THE BUSHELL BROTHERS’

BOATYARD

TRING FLOUR MILL TODAY

――――♦――――

THE NEW CANAL AND GAMNEL WHARF

An early product of the Industrial Revolution was our canal network, which improved

quite dramatically the

means of transporting goods, particularly those in bulk such as coal,

grain and manure (for in that horse-powered age, large quantities were shipped

from the cities to fertilise the land). Many local businessmen and farmers soon became aware of the

potential benefit that canal transport would have on

their profits, and factories, mills and wharfs soon sprang up along the banks of the new waterways.

The Grand Junction Canal (since 1929, the Grand Union Canal) reached

north-west Hertfordshire at the end of the 18th century.

Fortunately for Tring, which would otherwise have been bypassed, the need to provide the

Canal with a

reliable

water supply as it crossed the ridge of the Chilterns led to

a plan to construct a feeder ‘ditch’, which led westwards along the

contour between Bulbourne and Wendover, passing the northern

outskirts of Tring on its journey. However, pressure from local farmers and land owners

led the Grand Junction Canal Company (GJCC) to apply to

Parliament for an Act to make the ditch navigable.

In due course the following

statutory notice appeared in the newspapers published along the

route

of the GJCC, giving notice of the Company’s intention to apply to

Parliament for an Act which, among other things, would authorise

them:

“. . . . to make navigable, the cut or

feeder now making, and intended to be made, by the company of

Proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal, from the town of WENDOVER,

in the said county of Buckinghamshire, to the summit-level of the

Grand Junction Canal, at Bulbourne, in the parish of Tring, which is

to pass in, to, or through the several parishes of Wendover, Halton,

Weston-Turville, Aston-Clinton, Buckland, and Drayton-Beauchamp, in

the said county of Buckingham; and the parish of Tring; till it

joins the said summit-level at Bulbourne aforesaid. Dated this 5th

day of September, 1793.”

E. O. Gray, Aston

Chaplin, Clerks to the Company.

Exactly when the Wendover Arm was completed is unknown, but it was

probably shortly after 1794, for in his progress report of May of that year

Chief Engineer William Jessop states that “About seven-eights of

the Wendover Canal is cut”, and in a GJCC circular of November,

1797, reference is made to “The Wendover collateral line, now

finished for the sake of the water.” Thus, the Arm was widened and made navigable, and

wharfs were built at, among other places, Gamnel (Tring), Buckland and Wendover to

cater for the trade that commenced when the main line of the canal reached Bulbourne

Junction in

1799.

The earliest reference to milling in the

Gamnel locality is also in that year. The site now occupied by Tring Flour Mill (Heygates Ltd.) was in the vicinity of a water mill –

probably located near the Baptist Chapel in New Road – that had been bought

by the GJCC and then dismantled, its water supply having been

diverted into the canal summit. The loss of the mill pond affected the local Baptist community, whose

traditional baptism ceremonies were thus curtailed:

“The Water Mill at New Mill is now sold to the Canal Company, and the pond

cannot therefore be used in future for baptism. A baptistery is

being made in front of the pulpit in the Chapel [where it

remains].

The Mill had previously been in the ownership of friends of the

Chapel, and after a baptismal service the women used to change their

clothes there, and the men walked up to the Chapel to change. The

open-air baptisms were a good thing [to be] done away with, although

they were greatly preferred by the Minister and some members of the

Chapel. The services were always scenes of much hostility and abuse

from certain people in Tring, the participants in the service

oftentimes being pelted with filthy missiles.”

From the Tring

Vestry Minutes for

1799.

Then, on the 14th October 1800, the GJCC Minutes record that a wharf at Tring

– presumably

that at Gamnel, now generally known as

“Tring Wharf”

– was sold by auction for three years from 29th September. It

was taken by James Tate, a coal merchant and barge owner, for £15

per annum. The first reference to

“Gamnel”

appears in a deed of transfer held by Dacorum Heritage Trust dated the 5th July 1810, when

the GJCC sold the freehold of what appears to have

been the

same site . . . .

“. . . . by Deed Poll under Common Seal in Consideration of Four hundred

pounds paid to them by the said William Grover grant and release to

the said William Grover his Heirs and Assigns All that wharf Land

and Buildings thereon containing one acre and three roods more or

less situate next Gamnel [canal] Bridge in the Parish of Tring . . . . ”

. . . . which, with some later extensions, is the site now occupied

by Heygates flour mill (see map below).

|

A section of the GJCC's plan

for the Wendover Arm, the numbers identifying the respective land

owners.

The canal company bought the Gamnel site –

plots 25 & 26 (shaded red), comprising an area of 1 acre and 3 roods

–

from Henry Harrison and William Butcher respectively.

|

――――♦――――

THE GROVER FAMILY

William Grover must have seen a business opportunity in further

developing the Gamnel site on which “wharf

Land and Buildings”

did already exist.

On it he (or perhaps his brother James) later erected a windmill and

set up in business sending and receiving goods by canal. Exactly when the windmill was built is unknown. Andrew

Bryant’s 1820-21 map of Hertfordshire includes a windmill symbol at Gamnel Wharf,

while Pigot’s Directory for 1823 lists the brothers William and

James Grover as ‘millers’ at Gamnel, but the earliest record of

Gamnel

Wharf and premises is in 1829, when they were held by William

Grover, while James Grover held the windmill and a house on the same

site, at a rateable value of £13. 5s. 0d.

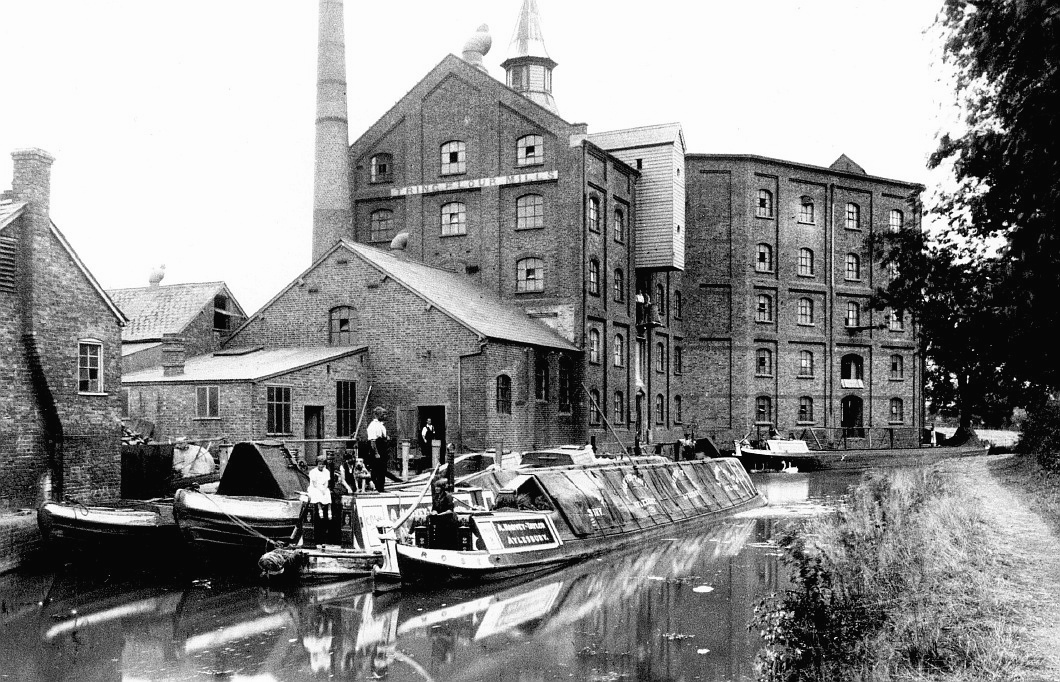

Viewed from across the Wendover

Arm, the steam mill erected in 1875

and the tower mill demolished in

1911.

Old photographs show the mill to have been a brick-built 6-storey

tower mill with a gallery on the second floor. In its latter

days its four sails were of the double-shuttered patent type.

The cap was in the ‘Kentish style’, winded by a fantail with an

extension at the rear to support the fantail’s stage. It was

considered to be a relatively large mill having power sufficient to

drive at least three pairs of millstones. While no record

exists of the mill’s machinery, it was probably comparable to that

in the later tower mill at Quainton and, judging from photographs of Gamnel Mill, was of similar

external size and appearance.

At some time after 1829, the partnership between the Grover brothers

ceased. Why is unclear, but following their father’s death in

1820 there arose a prolonged dispute between them concerning the terms of his will. In her

history of Aldbury, Jean Davis refers to a vestry dispute of 1828,

and states that . . . .

“The fact was that, at some time before he died in 1820, John Grover

had given up his baker’s shop in Aldbury and moved to Tring Wharf. Having acquired some land in North Field, he proceeded to build a

house there adjacent to the road, which he left to his son James

with the crop and implements and household goods. According to John

Clement, watchmaker and Baptist preacher of Tring, James’s brother

William disputed the will, which finally went to arbitration. James

is reported to have said that he was wronged of ‘hundreds of

pounds’.”

For whatever reason, James Grover set out to build and work the nearby

Goldfield windmill in competition with his

brother, which is where the 1839 edition of Pigot’s Directory

lists him. The mill at Gamnel Wharf continued to be run by William in partnership with his son Thomas, while the pai ralso

ran a canal carrying business, their listing in Pigot’s trade

directory for 1839 advertising services “To

London and all places on the line of the Grand Junction Canal, and

goods forwarded to all other parts of the Kingdom, by Grover and

Son, from Gamnel wharf, and Thomas Landon, from Cow Roast wharf,

daily.”

The 1841 Census records William

Grover, then age 60, at Gamnel with his son Thomas, and the Hillsdons, father and son, who were later to set up business as

millwrights in Chapel Street, Tring, all four being

described as millers. But the business was not to last much longer.

In January,

1843, a brief notice in the London Gazette announced the

dissolution of the partnership between William Grover & Son, wharfingers, of Tring Wharf and Paddington.

In the following month, a notice appeared in the

Bucks Advertiser announcing that:

“William Grover, in the town of Tring in the County of

Hertfordshire, having on the 28th day of January last disposed of

the business of wharfinger, coal and coke merchant and mealman, and

dealer in hay, straw, ashes, and other things, lately carried on by

him in partnership with Thomas Grover, at Tring Wharf, and at

Paddington in the County of Middlesex, under the firm of ‘WILLIAM

GROVER & SON’ to his sons-in-law, William Mead and Richard Bailey.

Messrs. Mead and Bailey beg to announce that they will continue to

carry on the same business, upon the said premises, in partnership

under the name of ‘MEAD & BAILEY’. All debts due to and owing from

the said William Grover, will be received and paid by Mead &

Bailey.”

The inherited rumour is that William Grover became insolvent, but a

book held in the Herts Records Office based on correspondence

between the deacons of New Mill Baptist Chapel and William Grover

attribute the reason to illness:

“He [William Grover]

had a sad end. He became ill and descried to make the business

over to Richard Bailey and William Mead – they took over the Wharf

and it was conveyed to them, and paid annuities of £100 to Wm. and

£90 to his son during their lives -

‘since

it has been said that his circumstances being in a deranged state,

caused his illness, if he was ill, which some thought not the case.’

Thus the Wharf and house that he had erected passed away from

himself, his son and grandson, and his name perished from his

inheritances after the sudden death of Richard Bailey in Feb. 1856.”

Characters against Clements 1853 (ref:

D/EHn Z48/6, Herts Records Office)

It is interesting that the Grovers described themselves not as

millers, but as “wharfingers”, which suggests that their

principal business activities were the shipment of produce by canal

and the resale of imported bulk commodities, such as coal, coke and

manure.

In an age before the development of road transport and with the

nearest railway goods yard almost two miles from Tring town centre,

the Wendover Arm was not only an important source of water for the

Grand Junction Canal, but of commercial importance to the town and

its surrounding area. Indeed, it is known that the Arm was

used to convey grain not only to the windmill at Gamnel, but also to that

at Wendover, it too being located

strategically close to that town’s canal wharf.

After 1843 the Grovers disappear from the story of the mill, and for

the following century Tring Flour Mills were owned, either in

partnership or in the sole possession of members of the Mead

family, eventually becoming known as Mead’s

Flour Mills.

――――♦――――

THE MEAD FAMILY

Following the change of ownership, Messrs. Mead and Bailey continued to offer a diverse range of

services at Gamnel Wharf, advertising themselves as millers, coal merchants, wharfingers

and water carriers. They were also dealers in horse manure, which they

imported by canal from London sending cargoes of hay and straw in

return. It is likely that Bailey managed the wharf, for in the 1851 Census he describes him as “Miller

and Wharfinger” while Mead appears as “Farmer and Miller”(the Mead

family continue to farm in the area today). Their workforce numbered around 30 men, which the Census

lists living (with their families) in the

immediate vicinity of the mill, which covered only half the area of

that taken up by the mill today. William Mead lived on

site in a handsome house adjacent to the yard. However, it is open to question

whether this was a close-knit and caring community, for a

contemporary account relating to one of the mill’s employees rather

belies this view.

William Massey, who worked as a labourer at the mill, lived with his

family on the wharf where he rented a hovel from the miller for a

shilling a week. David Shaw, in his

biography of Gerald Massey,

William’s eldest son, writes:

“For this money they [the Massey

family] were given a damp flint stone hut

with a roof so low that it was impossible for an average adult to

stand upright. Having paid the rent, nine shillings remained from

William’s weekly wage to provide a minimum subsistence.”

In his autobiographical sketch, John Mead, William Mead’s sixth and

youngest son, also refers to the cottages (and to the

windmill):

“We are sometimes told that adults do not generally remember

anything that happened before they were 5 years old, unless of a

very special character. Such a special happening did take

place in my case, for the neck of a windmill broke, and the sails

all tumbled down together. This is my earliest recollection, and I

was then but 3 years old [i.e. 1849].

It was the custom in those days for mothers to send their children

while very young to such schools as were convenient, so that they

could get on with their work without being hindered by the presence

of the little folks, and I was sent, with my cousins the Baileys,

when under 4 years old. My first school was at Mam Rowe’s, who lived

in one of 4 houses in a row of 4 flint cottages. The next one was

occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Massey, parents of the better known Gerald

Massey, the poet; and the others by Thomas Rowe, a stoker at the

mill, and Joseph Anderson. The rent of these cottages, including

good gardens, was about 1/- per week. At Mam Rowe’s school we sat in

a row on a form about 1 foot high, and there I learned the

alphabet.”

Gerald Massey (1828-1907),

poet, critic and writer

on Ancient Egyptian beliefs.

Gerald Massey was to become a Chartist agitator, later acquiring

renown in literary circles as a poet, critic and author. Some years after

William’s death, Gerald Massey had this to say about his late

father’s employment at Gamnel Wharf . . . .

“I know a poor old man who, for 40 years, worked for one firm and

its three generations of proprietors. He began at a wage of 16s. per

week, and worked his way, as he grew older and older, and many

necessaries of life grew dearer and dearer, down to six shillings a

week, and still he kept working, and would not give up. At six

shillings a week he broke a limb, and left work at last, being

pensioned off by the firm with a four-penny piece! I know whereof I

speak, for that man was my father.”

Regardless of whether the Meads treated their employees in such a

Dickensian manner, their business prospered. However, the partnership between Mead & Bailey

was to end in 1856

with Bailey’s death.

In the following year his widow Sarah bound their

son Thomas as an apprentice miller to Edward Mead for a period of

five years.

The details of whatever financial settlement William Mead reached

with Sarah Bailey do not survive, but following her husband’s death

sole ownership of the mill

passed into the Mead family, beginning with William.

By the 1860s ownership of the mill had passed jointly to William’s

sons, Edward and Thomas, but in 1865 Edward sold his share to

his brother John, who three years later sold out to Thomas, leaving

Thomas Mead the sole owner of the business. In the same year

Thomas extended the site with the purchase of an adjoining plot of

land facing the Wingrave Road (curiously, the purchase document

describes his occupation as “farmer”).

Although not relevant to the milling business, it is interesting to

see the nature of the canal trade that was still being carried out

at Gamnel Wharf despite the damaging impact of the railway.

This from John Mead’s autobiographical sketch . . . .

“My next move was to Gamnel Wharf, where I was born – my brother

Albert who had the hay and straw trade there was a bachelor.

He had done well in business, and offered to let me have it which I

did, taking it over in 1879, when I was 33 years old. I then

became coal merchant, lime burner, and dealer in artificial manure

etc., sent hay and straw to Paddington by canal, and had stable

manure for the return journey . . . . I had nothing to do with the

sale of hay and straw at 5 South Wharf, Paddington. My brother

Albert arranged with another brother, Frederick, to pay commission

of 1s. on each load of 36 trusses of straw, and 5s. on each ton of

hay, and he charged 2s. 6d. for each ton of manure brought back by

boat.”

. . . . from which it is fair to conclude that at this date the

Wendover Arm remained important to local farming interests.

Thomas Mead was blessed with five sons (of which Thomas Mead Jnr. died in

his youth) and two daughters. In the late 1890s Thomas Mead Snr. bought Clifford Mills, Northampton, and this business was

managed by Frank and Duncan Mead, until Duncan was killed in the

Boer War; Frank then carried on the business alone for many

years. Of the other two sons, Percy later took over Gubblecote

Farm, Tring, which his descendents continue to farm, and, in 1898, William

bought the Tring Flour Mill from his father in exchange for an annuity

of £200 p.a.

William Mead then carried on the business

successfully until his death in 1941, at some time also farming

Old Manor Farm, Wingrave; Hospital Farm, Marsworth; and Silk Mill

Farm, Tring. And until government restrictions caused it to be

discontinued following the outbreak

of World War II., he also ran a

successful retail coal business from the wharf.

――――♦――――

STEAM-POWERED MILLING

By the 1840s it appears that a steam engine had been installed to supplement wind power,

which by then was fairly common practice, for in his

autobiographical sketch John Mead refers to one of the occupants of

the mill cottages as

“Thomas Rowe, a stoker at the

mill”

(the 1861 Census lists

19-year old Samuel Bull as an “engine stoker”). Nothing is known about the steam

engine, but later evidence suggests it was separate from

the windmill, unlike the practice adopted at Wendover where a

small steam engine was installed beside the windmill and coupled to

its spur wheel (which drove the millstones, etc) via an iron shaft

and cog.

Wendover windmill and engine

house.

The

flue from the engine’s boiler passed underground to a tall

brick-built chimney in the centre of the mill yard.

By this date the business at Gamnel Wharf was run by William Mead’s

sons Thomas and Edward (who also rented Wendover windmill).

Edward had become a busy man, having acquired milling interests at

Watford, Hunton Bridge and Chelsea.

But having sold his share of the business to his younger brother

John in 1865 (see previous section), Edward Mead departs from the

story of Tring flour mill. John Mead then carried on in

partnership with Thomas for 3 years, as he records in his

autobiographical sketch . . . .

“Prior to my return home Gamnel [a.k.a. Tring]

Flour Mill was run by my brothers Edward and Thomas, but the former

took the mill at Hunton Bridge, near Watford, and said I might have

his share of Gamnel for £1500. This I accepted, giving notes

of hand [i.e. promissory notes],

which I paid off when I had earned the money. I worked hard,

sometimes up to 10 o’clock, and if windmill and steam-mill

were both working I would stay until 1.00 o’clock in the

morning.

In these cases I slept at my brother William’s house . . . .

After being a miller for 3 years, my brother Thomas took the

business, and I became a farmer. This was in 1868 when I was

22 years old, but farming was not so remunerative as milling.

I should have made more money at the mill.”

. . . . after which John also leaves the story of the Tring Flour

Mill.

A particular

milestone was reached on the 1st March, 1875, when Thomas Mead took the bold step

of signing a contract for the construction of an imposing brick-built grain mill adjacent to the

windmill. The builder was one Duncan Stewart of Wallington, in

Surrey, who undertook to build the mill for the sum of £1,246, the contract

stipulating that the building was to be complete by the end of July

against a penalty of £2 for every week over-run.

The new steam mill. It

consisted of five spacious and lofty floors

fitted with the

necessary storage bins.

The new mill was powered by a beam engine capable of driving five pairs of

millstones.

Installation of this new machinery did not go without incident,

as one local newspaper reports . . . .

“Accident — There was a shifting of the old boiler out of the old

engine house at Mr Thomas Mead’s flour mill into the new one on

Tuesday; and in order to do this, the boiler had to be raised four

feet. A small space had been left at the end for the jack, and the

block underneath slipped when the boiler was raised about two feet,

and caused the boiler to run ahead, striking against Lot Denchfield,

fracturing his right thigh and left fore arm. Denchfield was at once

taken to the County Infirmary at Aylesbury.”

――――♦――――

WIND MILLING GIVES WAY TO ROLLER MILLING

|

|

|

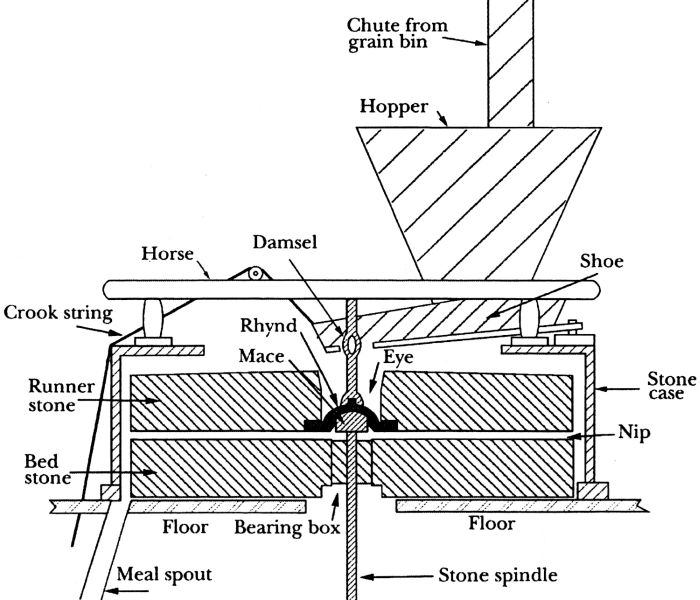

Schematic

illustration of traditional

milling equipment. |

The

age-old process of producing flour was to crush wheat between

two circular millstones. Of the two, the lower ‘bed stone’

remained stationary while above it the ‘runner stone’, which

does the grinding, was caused to rotate under the power of a

windmill’s sails or a waterwheel (a few combined wind and

water mill also existed, Doolittle mill at Totternhoe been a

nearby example). Under gravity, wheat trickled into the

eye of the rotating runner stone from where it was channelled

between the faces of the two stones. The rotating runner

stone then subjected the wheat to a ‘scissoring’ or grinding

action that produced ‘meal’. The runner stone was

generally slightly concave, while the bed stone was slightly

convex. Under the rotating action of the runner stone,

this shaping channelled the meal to the outer edges of the

stones where it was gathered up.

A ‘flour dresser’ was then used to sift the meal into various

grades of fineness. This consisted of a cylindrical drum

covered in wire mesh of increasing grades of fineness, and set

at an angle. Inside the drum revolved a set of brushes.

Meal, fed into the upper end of the cylinder was rubbed against

the mesh screens by the brushes as it fell through the cylinder

under gravity. The finest meal, white flour, passed

through the finest mesh screen; next came semolina flour, which

passed through the next grade of mesh, leaving the coarsest

product, bran. Each grade was ejected into canvas chutes

which feed sacks on the meal floor below.

|

|

|

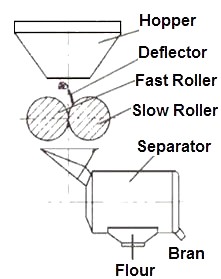

The principle of

the roller mill. |

As the 19th century progressed, advances in technology swept away

old industrial systems and grain milling was not exempt from

progress. Thus, in 1894 Thomas Mead took a further step forward

when he installed the recently-developed roller milling system,

running it for some years in conjunction with the windmill (which

was

probably relegated to grinding animal feed).

Roller milling made possible the construction of larger, more

efficient grain mills, hastening the abandonment of the small

country wind and water mills that used millstones to crush

the grain. The new system crushed the grain between a series

of fluted steel rollers of about 12 inches in diameter. The

rollers are set with a specified gap between them and spin towards

each other at high, but at different speeds; the surface of each

roller is also grooved with a different pattern. The input and

output to the milling equipment is through a system of pneumatic

pipes.

Roller mills

enabled the production of a larger amount of better-grade flour from

a given amount of wheat, quicker and to a much more consistent

standard than traditional stone grinding. (Appendix

1)

A modern roller flour mill.

Then, in 1905, Thomas’s son William, by then the mill’s owner, (Appendix

2) replaced the old Bolton & Watt-type beam engine with

a Woodhouse & Mitchell tandem compound condensing engine, rated at

120 hp, which drove the mill until it converted to mains electricity in

1946.

The early 20th century saw the rapid demise

of what windmills remained. After some ninety years of service Gamnel Wharf

tower mill was demolished on 4th May 1911. A local

newspaper gave the following account . . . .

“Removal of a Landmark — On May 4th a familiar landmark was

demolished. For many years the old windmill where Mr. Mead and his

ancestors have long carried on their business, has stood at Gamnel. The leisurely business methods of bygone days have had to give place

to more up-to-date arrangements and so the ground on which the old

mill stood was wanted for an extension of the steam-powered mills. Under the personal direction of Mr W. N. Mead the structure was first

undermined, wooden struts taking the place of the brickwork and when

it was ready a steel cable and winch hauled it over.”

The demolition of Gamnel Wharf

tower mill, 4th May 1911.

――――♦――――

|

|

THE

MILL UNDER WARTIME CONDITIONS

Following the demolition of the windmill, nothing is then on record

until the 1930s. This was a time of severe depression

throughout the land, which included farming and milling. Subsidised French flour was brought into this country

for as little as 12s 6d (twelve shillings and six pence) a sack of

280 lbs. Wheat was selling for about 18 shillings a quarter

(4½ cwts or 229 kilos), and even home-produced flour was as low as

17 shillings and 18 shillings a sack, but with the inception of the

Wheat Act (1932) [3] conditions gradually improved

and farming became more secure. Then, at the outbreak of World

War II., in common with all other flour mills, Tring was brought

under the control of the Ministry of Food. No-one envisaged at

the time that this control would last until August 1953, nearly 15

years! – indeed, government controls and restrictions on the

production and distribution of food grew even more severe for

several years following the return of peace.

During the war the

milling business was run under very difficult conditions. This

was due in part

to the rationing of a wide range of items, to manpower

shortage, and to stringent government controls implemented by the

Ministry of Food. In his autobiographical sketch,

Ralph Seymour, the mill’s

former General Manager,

describes working under Ministry of Food control:

“The

effect of the World War II on the mill was instant and shattering.

We came under the direct control of the Ministry of Food, who issued

an endless stream of Statutory Rules and Orders, which sometimes

contained twenty or thirty pages of closely printed instructions and

regulations, all couched in such legal jargon and phraseology as to

be almost incomprehensible. You needed the help of a lawyer to

decipher it all, so much so that one wag succinctly observed

‘You

don’t make a mistake today, you commit an offence!’

[4]

The mill

was now run on a constant 24 hours, 7 days a week basis. The

men worked 8 hour shifts − 6 a.m. to 2 p.m., 2 p.m. to 10 p.m., and

10 p.m. to 6 a.m. again, and these were worked on a rotation basis,

so that each man worked a different shift each week, on a 3-week

cycle. The only stops were made for essential repairs and

maintenance, but to get parts and machinery replacements you had to

sign applications ad nauseam to obtain a licence. Even

then you had to use every wile and trick known to man to actually

get the stuff! I have personally travelled 150 miles or so to

fetch a particular part.

Unfortunately

Harold Saunders, the flour traveller, died in 1940, and a few months

later Teddy Clarke also died. Replacement staff had to be

employed, and we were lucky to get an accountant, who came out of

retirement to help, and we also found a flour traveller who was

exempt from war service, but every firm then was having staffing

troubles, as so many were in the services, or munitions, or other

war jobs.

Soon,

all animal feeding stuffs were strictly rationed. Coupons were

issued to all owners of livestock, the number of coupons being

apportioned from returns made in previous years to a government

department, and depending on numbers and type of stock. Beef

farmers, for instance, fared very badly, as they were expected to

make full use of their grazing land, whilst producers of milk were

in a much better position.

The

coupons were valid for the month of issue and the subsequent month

only, and a strict account had to be kept of each transaction.

Officially, no customer was to become ‘overdrawn’ so to speak.

The coupons then had to be tabulated by us on special forms, fully

detailing the number and value of each coupon, and the quantity and

type of feeding stuffs supplied against it. Different forms

were required for the different types of feed-cereals, protein,

etc. The forms then had to be submitted to a central area

office, in our case Cambridge. On submission of the tabulated

forms to Cambridge, we were issued with Buying Permits, to enable us

to purchase more feeds for sale. At the end of each month,

these again had to be tabulated.

Under Ministry control the quality of flour was gradually lowered.

White flour became unobtainable, and the resultant output of

‘national’ flour produced a ‘standard’ loaf of a dingy grey crumb.”

――――♦――――

HEYGATES ACQUIRES THE BUSINESS

William Mead and his wife

Edith.

William Mead died in April, 1941. There being no son to

succeed him, the business passed into the control of his executors

and trustees. Ralph Seymour, who was a

minority shareholder in the business, [5] states

in his memoirs

that the three years following

William’s

death were a very unsettled period during which the

future of the mill was by no means clear. Then, early in July 1943,

Ralph

returned from a busy day on the London Corn Exchange to learn that

the mill had a new owner – he relates what then transpired:

“. . . . on coming into the office I

was introduced to a Mr. Robert Heygate. This gentleman said he

wished to consult me about the purchase of English grain from the

coming harvest. ‘In what connection, may I ask?’ I

enquired. ‘My family has bought the business of Wm. N. Mead

Ltd., and has paid a deposit,’ was the startling reply. ‘Well,

you haven’t bought me with it, have you?’ I responded. I

suggested that we should talk after I had dealt with all the affairs

of my London trip, and if he would accompany me to my home for tea

we could converse without interruption. Subsequent to my

meeting with Robert Heygate I agreed to travel down to their family

mill at Bugbrooke, Northampton, to meet his father and elder brother

Jack. I liked what I saw there. A family firm, they had

employees with upwards of 50 years in their service, which told its

own story.

I agreed to continue to manage the Tring business, but much of the

previous responsibility was off my shoulders. From the outset

the Heygates placed implicit trust in me and, as formerly, I

continued to be the sole signatory for cheques, etc. After

consultation, it was agreed that for the time being the Tring mill

would continue trading under the name of Wm. N. Mead Ltd; three

years later the trading title was revised to Meads Flour Mills Ltd.,

still with me in charge, and we continued under this name for a

number of years.

Despite the limitations of continued Ministry control and shortages

due to the war, I liked the Heygate approach, which was: ‘What

can we do to modernise,’ rather than the old Governor’s ‘Make

do and mend’ attitude.”

Messrs. Heygate and Sons, of Bugbrooke Mills, Northampton were – and

remain – a family business of millers, merchants and farmers.

The family, who had been farming the same land in Northamptonshire

since the 16th century, [6] moved into milling in the 19th

century, when Arthur Heygate Snr acquired Bugbrooke Mill. A

large change to the business came in 1942 when the mill was

destroyed by fire. It was rebuilt with state-of-the-art

milling equipment capable of converting 24 sacks of wheat into 18

sacks of flour every hour, plus bran for a feed mill alongside.

In 1944 the company acquired the Tring Flour Mill followed, in 1958,

by the Downham Market Mill. Subsequent investments have made

Heygates one of this country’s largest independent millers, while

the Group also has interests in a specialist milling business in

France.

Ralph Seymour, for many years

General Manager of Tring Flour Mill.

Following

retirement Ralph was ordained and worked as a clergyman

in the Parish.

Following the takeover, the management of the Tring Flour Mill was

reconstituted. Ralph Seymour became General Manager and with

the return of peace the ravages of the war years were gradually

repaired. From 1946 to 1950 considerable extensions were made

to the warehouse and the offices. The conditioning bins were

increased in capacity and the intake of wheat by barge was

discontinued, with all supplies subsequently arriving by road.

This change created a very awkward bottleneck in the single road

access to the mill, the existing entrance being between the Mill

House building and the mill cottages. To remedy the problem

some 2 acres of land on the south side of the mill were purchased

from the Rothschild estate to permit a new access road to be laid

down. To make an entry, the old south boundary wall

was removed – this had formed part of the Carpenters’ Shop

and was the remaining part of the old windmill that had been pulled

down in 1911. Shortly after this work was complete it was

found necessary to extend the warehouse and the silo accommodation,

which until then were exactly as built nearly 40 years previously.

With the return to peace government wartime controls gradually

eased. Bread production was no longer limited to the national

loaf [7] and again became profitable. Good salesmanship in both

flour and feeding stuffs became essential. With the

mill remodelled, production increased and the business grew steadily.

Major re-arrangements of the flour milling procedures were again

undertaken in 1955-56 when the first pneumatic system was installed,

the third such installation in the U.K. Further major changes

took place during the 1970s, when additional bulk flour storage was

erected, and all the wheat cleaning plant and almost the whole of

the mill machinery was replaced. Careful management of this

project permitted the mill to continue to grind the same amount of

grain each week while the work was being carried out.

――――♦――――

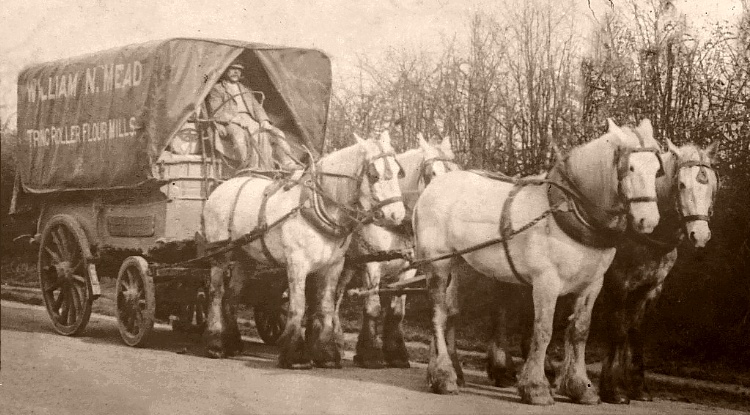

TRANSPORT |

Above: A. Harvey-Taylor

(Aylesbury) narrowboats at Gamnel,

c.1930s.

Below: Mr. and

Mrs. Ward from Startops End with their daughter Phoebe and her

family.

They are discharging

Manitoba wheat at Tring Flour Mill.

|

By the late 19th century much U.S. and Canadian imported wheat was

being exported to the U.K. In his

memoires Ralph Seymour says that it was shipped by barge from Brentford to Bulbourne, where it was transferred to a horse-drawn narrowboat for

its passage to the mill up the narrow Wendover Arm. However,

the above photographs suggest that wheat might also have been shipped

directly to the mill by narrowboat.

So far as local deliveries were concerned, before the Great War horse-drawn

wagons were used to deliver goods, with either 2-horse or

4-horse teams according to the load, the flour being delivered as far

as Chesham, Aylesbury, Leighton Buzzard and Dunstable. A

single horse van was used for smaller local deliveries. Then,

in 1916, a Foden steam wagon running on solid tyres and capable of

carrying 8-tons was first used; judging from the photograph below, a

Sentinel steamer also joined the fleet. In 1918, a 2½ ton

Napier lorry, also on solid tyres, was added, the body of which –

and of all succeeding lorries up until the Second World War – was

constructed by Bushell Bros. at their boatyard on the premises.

Above: a Foden steam lorry in

W. N. Mead livery. Below: a Sentinel steam lorry.

The intake of wheat by canal was discontinued soon after the end of

the World War II., with all supplies subsequently being delivered by

road.

By the time this photo was

taken the steamers appear to have been replaced

by internal combustion-engined

vehicles. This is a Dennis dropside lorry c.1935.

According to a 1953 article appearing in the Berkhamstead Gazette, the fleet

then consisted of two 6-ton and three seven-ton Bedfords, a Foden lorry and trailer with a carrying capacity 15

tons, and a bulk grain wagon with a carrying capacity of 13 tons

used for haulage of wheat from the Docks. The article goes on

to say that

“even

this is insufficient to cope with the work, so that a large tonnage

of business is hauled by local contractors,”

a situation that continues.

Today, the mill is owned by Heygates Ltd., whose transport division

operate a fleet of 80 vehicles covering their three milling

operations (16 being based at Tring) to deliver 450,000 tons of

flour annually.

――――♦――――

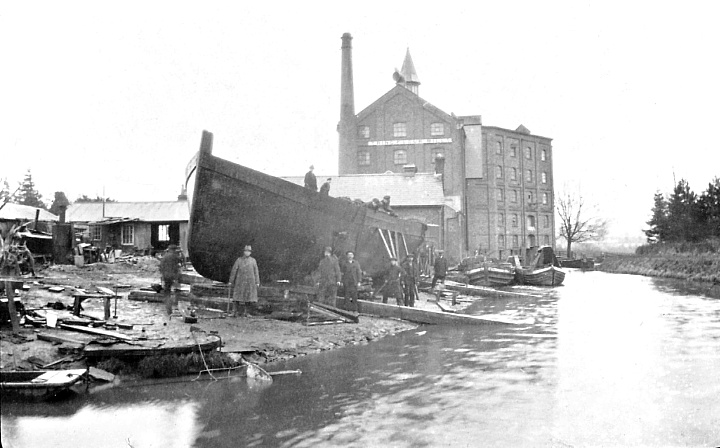

THE BUSHELL BROTHERS’ BOATYARD

|

The

motor barge Progress being launched at Tring boatyard in 1934.

|

Until the 1940s, all the imported wheat and flour used for admixture

were carried along the Grand Junction Canal by barge from the London

Docks, and considerable quantities of flour were also despatched by

canal boat from Tring to London, particularly to the Fulham and

Chelsea districts. In the early days of the Mill the barges

often returned to London carrying other cargoes including hay and

straw for use in the horse-powered Metropolis.

Meads had their own fleet of barges, and from about 1850 John Bushell, a local man, was employed by the Meads to

build and repair them. At that

time canal boats were often built in small boatyards run by a few

men and this applied at Gamnel Wharf, where the boat builders worked in the open air in

the most extreme weather. Eventually – c.1930 – the open-sided shed

shown above was erected to provide some shelter from the elements.

Modernisation at the mill in 1875 resulted in John Bushell’s son

Joseph leasing the boatyard and developing it into a separate

business, while continuing to meet the Meads’ requirements for

building and maintaining their canal craft.

In 1912,

Joseph Bushell’s two sons, Joseph junior and Charles, took over

the business. They renamed it Bushell Brothers, and boats for

many of the largest canal users in the country were built and

repaired in their boatyard. Their crowning achievement was the

400 h.p. barge tug Bess built in 1920 for use on the Thames. Following

her sideways

launch she was taken along the Grand Junction Canal from Tring to London.

Most careful precautions had to be taken before this could he done

to ensure that she would clear all the bridges on the route, and

scale models of the tug and the two bridges likely to give trouble

were built, which showed a clearance of just 2 inches – when Bess

at length reached them, the clearance was found to be exactly 2

inches!

Bess being prepared at Bushell

Bros. boatyard for launching into the Wendover Arm at Gamnel.

Tring Flour Mill complete with

its splendid engine chimney is in the background.

The Thames tug Bess, built

for the London Haulage Co. in 1920 by Bushell Bros. at Tring.

Originally powered by a 400 h.p.

steam engine, she was re-engined in 1926 with a 200 h.p.

Kromhout diesel.

By the 1930s as

canal traffic and the market for new barges and repairs was declining,

and more varied work had to be sought.

Besides their work on narrowboats, the firm is known to have built

and repaired pleasure boats, maintenance flats, wide boats, tugs and

even a fire float, while their letterhead advertised boats for hire,

carpentry and decorating services.

Shortly before its closure in 1952, Bushells were constructing and

painting coachwork for commercial vehicles.

Some examples of Bushell Bros.

coachwork.

|

――――♦――――

TRING (HEYGATES) FLOUR MILL TODAY

Silos at Tring Flour Mill, from

the works entrance.

|

Today, flour milling continues at Gamnel Wharf, but in a manner

greatly transformed from its wind and steam-driven milling days.

The mechanical shafts, cogs, belts and sets of grindstones have long

been replaced by banks of cabinets that house sophisticated filters

and grinding rollers serviced by a network of pneumatic feeder

pipes. The finished product is no longer packed in the

2½ hundredweight (280 lbs.) sacks that carters like

William Massey had to deliver into bakers’ lofts, sometimes carrying

each sack up slippery external wooden steps or ladders. Today, Gamnel’s modern automated packing plant fills 32 kilos (70 lbs.)

sacks as well as a large output of 1½ kilo bags for the domestic

consumer market. These are then neatly palleted, swathed in polythene sheet,

and loaded onto lorries by forklift truck. Some flour also

leaves the mill in bulk transporters such as that shown on the right

of the picture above.

Rear of the steam mill of 1875.

In the days of the windmill, two millers could process half a ton of

grain per hour. Today, only two men are needed to operate the

plant, but its electrically-driven machinery operating under

computer control can mill 12 tons per hour; or put another way,

100,000 tons of wheat is milled in a year resulting in 76,000 tons

of flour (the bulk of the waste going into animal feed), mainly for

baking, but there is also a major commitment to wholemeal for

biscuits and bulk outlets. The mill employs a workforce of 80, and 16 trucks deliver its

products to outlets throughout the south of England.

Silos

at the rear of the mill.

Overall, the Heygate Group spans farming, flour and feed milling and

baking, with seven flour mills on three sites, a feed mill, two

modern bakeries and 7,500 acres of mainly arable land in England.

In total it employs over 900 staff, compared to just 20 in 1935. Its

seven flour mills over three sites consume more than 450,000 tons of

wheat a year, the vast majority coming from British farms.

More than 80 grades of flour are produced, for breads, cakes,

pizzas, burger buns, chapattis, biscuits and more besides, supplying

large manufacturing plants, in-store supermarket bakeries and craft

bakers, delivering 24/7.

Rear of the flour mill from the Wendover Arm.

――――♦――――

APPENDIX 1

Before the actual milling process began, wheats were blended into

what was called the grist. The foot of each storage bin had a

calibrated release on a ratchet principle so that this could be set

and the correct quantity of each wheat released. All the wheats

contained extraneous matter to some extent, so the next process was

to remove this by a most exhaustive cleaning process, so that sound

grain, free from all impurities, resulted. By various elevators this

was then fed into a washing process, and from there into a

screen-meshed whizzer, to remove excess moisture.

The next process was to feed it into a heated container to open the

pores of the skin of the wheat, and then on to a cold container to

close the pores up again. The grist was then put into a conditioning

bin for 24 hours, with the result that drier grain absorbed moisture

from the damper, and a level moisture of about 16% was arrived at,

ready for the milling process.

The strongest gluten cells of the grain are towards the outer skin,

so the object of the treatment is to scrape them free without

breaking up the outer skin. A series of chilled steel spiral rolls

were employed, the first with serrations of four to the inch, the

top one of two revolving at a differential speed of 2 to 1, thus

opening the grain wide with a shearing action. The subsequent rolls

were serrated progressively less acutely. The release from these was

elevated to the top storey of the mill into a most ingenious machine

called a plansifter. This consisted of an outer wood casing

containing no less than 12 sieves, from a coarse wire mesh at the

top to a fine one at the bottom. The whole plansifter was suspended

from the ceiling attached to 16 flexible bamboo rods. Under the

bottom was an elliptical weight which, when in motion, afforded a

perfect sieving motion.

The releases from this operation were fed back to the roller floor,

the coarsest to the second rolls, and according to the grading, to

each appropriate roll, and a final pair of smooth rollers. Meanwhile, the finer separations from the plansifter were fed to the

enclosed cylinders inclined at an angle but clothed with coarsely

meshed cloth. The finer release was then fed to the next machine

clothed with finer mesh, and the over-tail despatched to the last

sequence of the rolls.

The resultant fine release was now actual flour, which was fed to a

holding bin, from where it was bagged up by an operative into jute

bags weighing 140 lbs. nett. (Nowadays it is packed into 32 kgs.

stiff paper bags, or alternatively stored in a glass-lined bin, from

which it is loaded into bulk lorries, and at the bakeries blown from

the lorries by means of compressed air into the bakers’ bins.)

――――♦――――

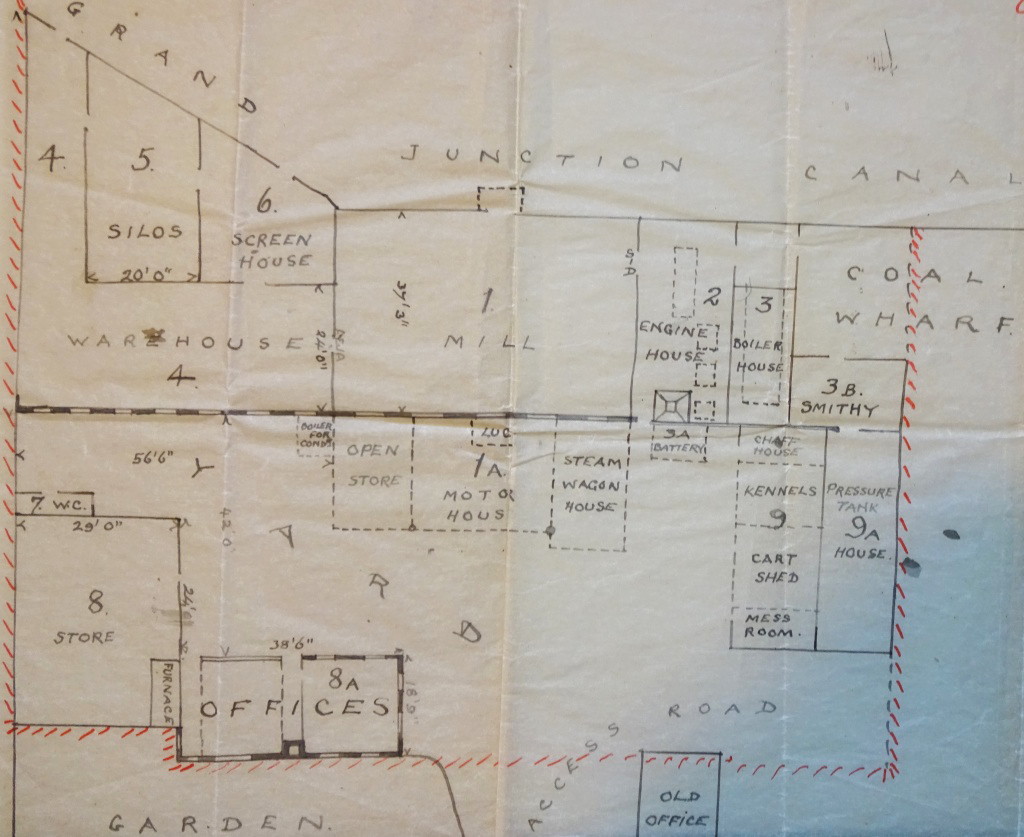

APPENDIX 2

In 1898, William Mead acquired Tring Flour Mill from his

father in exchange for an annuity of £200 p.a. Being a prudent

businessman, before completing the transaction William arranged to

have the business valued to assess whether it was worth the

capitalised cost of the annuity in relation to his father’s likely

lifespan (Thomas was then 65). |

This plan of the mill in 1929

was found among

some Mead family papers.

|

The

valuation has disappeared, but the following manuscript letter that

accompanied it provides an

interesting summary of the fixed assets of the business as they then

existed:

“In accordance with your instructions I have attended at the Steam

Flour Mills, Tring, July 5/98 and now beg to make the following

remarks.

The property consists of (all being freehold) a brick built

and slated house, fronting the Wingrave Road, containing kitchen,

scullery, dining room with marble mantel & folding doors to garden,

small sitting room with grate, passage & small wine cellar off;

basement and cellar.

First Floor: five bedrooms, bathroom and W.C.

There are also two staircases.

The Mill House, c.1930s.

Adjoining (and though originally a separate house, it is now

connected) is a brick built and slated dwelling house containing, in basement,

a dairy and cellar: ground floor, washhouse with 2 coppers, with range

and cupboards.

Room with grate forming entrance hall (under staircase is entrance

to a cellar), drawing room with marble mantel, dining room, also

entered from garden is a small office up steps.

In the rear is a pretty garden, tastefully laid out with shrubs,

trees, grass plots and paths.

The construction of the above mentioned houses is somewhat peculiar. They were originally a row of cottages, which have been built onto

and converted into their present state. The condition and state of

repair is generally speaking very satisfactory. Both houses are

inhabited by Mr Thomas Mead and his family.

Crossing the Wingrave Road, I came to a nice enclosure of a paddock,

enclosed with brick walls on two sides and containing a tennis

court, nut stems and fruit trees. At one side and at one time forming

part of same is a capital garden, enclosed with a high wall and well

stocked with fruit trees and laid out with paths. In it are a lean

to potting house and two lean two vineries.

The above described freehold land contains about 1½ acres. It has a

long frontage to the Wingrave Road and forms an excellent building

site. I understand, however, that at the present time there is no

demand for ground for such a purpose here.

Again crossing the road, I come to the wharf and business premises

connected with the mill, including four freehold brick built and

slated cottages, containing two rooms upstairs and two rooms

downstairs. Range of brick and slated wood barns to each house, also 2

WCs and shed at end. These cottages are substantially built and in a

very fair state of repair. They are let at 2s 6d per cottage per

week, the landlord paying outgoings.

Also abutting onto the Wingrave Road is a range of brick built and

slated stables and coach house (4 stall stable), also loose box, nag

stable and harness room. The coach house is entered by double

folding gates. The whole has lofts over.

In the rear of above is a range of brick built and tiles pigsties

with enclosed yard, 2 pigsties, feeding place and yard at back, and

open cast shed. Further is a paved washhouse with copper, 2 sinks

and 2 pumps with loft over brick built and slated coach house with

folding gates and loft over. Part paved yard behind. Boarded and

tiled 5 stall stable with brick underpinning and paved. Attached and

forming part of above is open shed, and oil shed.

The boat-building business that in

1912 became Bushell Bros.

There is also the spacious wharf used as a boat building

establishment and occupied by Messrs W. Mead and Co. Ltd., who have

erected several sheds for the carrying out of the business, which

are their property. The wharf also contains, adjoining the canal a

part brick built, boarded and slated warehouse and store with lofts;

also a brick built and slated warehouse further; a boarded warehouse

on brick underpinning with pan tile roof; a long boarded shed with

galvanised iron roof; a brick built and slated building forming a

forge and workshop.

The flour mill viewed from the

owner’s garden, engine and boiler house on the right.

William Mead bought

the ornamental fountain at the dispersal sale of Aston Clinton House

in 1923, while the stone relief coat-of-arms behind it

came from the Mark Lane Corn Exchange in London when it was

demolished in 1931.

The modernly substantially brick built slated steam flour mill,

known as Tring Steam Flour Mill. This is a very imposing and

handsome building erected as recently as 1875. It comprises a

lean-to boiler house and shaft through door to engine room.

The mill consists of five spacious and lofty floors fitted with

necessary bins. Above top floor is a platform and above a

glazed observatory. Boats can be loaded or unloaded directly

from, or to the mill ex canal. In front of the mill and

setting off the appearance is a very useful ornamental iron built

loading shed, which has recently been erected at a considerable

cost.

Edith

Mead and her three daughters in

the Mill House garden (one daughter died in childhood)

At right side of mill is a brick built and slated cart shed, chaff

house and 2 stall stable, loft over. On left hand is a

recently erected open shed with galvanised iron roof. Also a

weighing office and weigh bridge.

Adjoining, and entered by a covered passage from the modern mill, is

the original 4 story windmill in going order and repair, with a

lean-to brick built and slated store surrounding the base.

Part boarded and brick built store in position of old mill

adjoining. Brick built and slated engine room now used as a

wagon shed.”

A Sunday School outing about to

depart from Tring Flour Mill in 1931.

William Mead is shown with his arms outstretched.

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES

1. Yes, the shareholders of Thames Water would

classify sewage disposal as a ‘business’, even if their works at

Gamnel has not exactly been a profit centre in recent times (a fine of £1m plus costs was imposed on Thames Water

in January 2016 for discharging partially treated sewage from its Gamnel

sewage works into

the adjacent Wendover Arm of the Grand Union Canal).

2. Advertisements suggest that the sale of coal at Gamnel Wharf

continued to be

a lucrative business until government restrictions brought it to an

end at the outbreak of

World War II.

3.

The Wheat Act 1932 aimed to provide U.K. wheat-growers with a secure

market and enhanced prices for home-grown wheat of millable quality.

4.

“At one time the

chief officer at Cambridge was a fiend of a bureaucrat, and every

pettifogging little detail of the regulations had to be conformed

to. On one occasion I had an excess of 28 lbs. of face value on the

coupon returns I submitted, and my ‘friend’ at Cambridge refused to

accept other than an exact balance on the forms, and sent the

offending one back. I telephoned him, explaining the difficulties

in getting a balance to the exact pound every time, but he still

said he would refuse to accept, so I said

‘Right, then, I shall just

blot out the quarter of a hundredweight, and re-submit.’

I was

immediately told this would be an offence!

Hinting

that I had a friend in high office at the Ministry, I called his

bluff and got my Buying Permits.” . . . . Taken from Ralph

Seymour’s

autobiographical note.

5. The other shareholders were William’s wife Edith

– she being the majority shareholder – and his two daughters.

Edith Mead, c.1930s.

6. The first mill on the site was established in

800 AD and, by the time of the Domesday Book, was the third-highest rated mill in England.

It is now the site of the Heygate Group’s

headquarters and its flour mill, whose large central tower can be

seen for several miles around.

7. The National Loaf was of bread made from wholemeal flour with added

calcium and vitamins. Introduced by the government in 1942 to

save space in shipping wheat to Britain, the loaf was made from

wholemeal flour to combat wartime shortages of white flour.

The bread was grey, mushy and unappetising, and contained quite a

high amount of salt to make it keep longer - only one person in

seven preferred it to white bread. In 1950 sliced, wrapped

white loaves were again allowed to be sold, which people preferred,

although the National Loaf was not discontinued until October 1956. |

――――♦――――

<>

|