|

THE MEMOIRS OF RALPH SEYMOUR

CORN MERCHANT, MILLER AND CLERK IN HOLY ORDERS

|

FOREWORD

I knew Ralph Seymour slightly. Having transcribed the

following chapters I realise that I was the poorer for not knowing

him better, for that opportunity did once exist. We’re always wise with hindsight.

For the greater part of my working life I was in government service. During the

mid 1970s I was posted to a Ministry of

Defence computer centre near Stockport. Its role was to pay the

wages of the thousands of civilians then working at the Ministry’s dockyards,

army units and air bases dotted around the land (few of which survive).

My job was to audit the many and varied pay, allowance and

productivity schemes then in operation.

Technical matters concerning the treatment of National

Insurance Contributions led me to interview the centre’s guru on

such matters, a certain lady who a few months later became my wife.

Regulation audit often involved extracting certain information from the Ministry’s

computer files. Believing that if you want a

job doing properly then do it yourself, I taught myself to

program a mainframe computer, albeit at a fairly basic level. When word

of this leaked back to ‘head

office’ I was soon transferred to

London, the hub of auditing activities, for at that time any auditor who knew what a punched

card was was considered to be a ‘computer expert’, and such were in

short supply. And so my new wife and I duly set up house

within commuting distance of London, at Tring. Despite the

financial hardship of relocating to a high cost housing area and the weary

trek into London throughout the week, I never regretted moving to this

delightful area.

The removal men − having deposited our modest collection of furniture

in our newly built house − had barely set off

on their homeward journey when there came a knock at our

front door. I opened it to find an elderly, rather short,

stout and genial clergyman on the doorstep. “I happened to be

passing and thought I would take this opportunity of

welcoming you to the neighbourhood” or words to that effect formed

his opening remark. And so Jean and I met our first Tring resident

and over a cup of tea − another first in Tring − the Reverend Ralph

Seymour told us much about the Town and its locality.

From all reports Ralph

was definitely a ladies’

man.

Some 18 months later I found myself knocking on Ralph’s

front door, my visit being to ask if he would officiate at Jean’s

funeral. I was distressed and Ralph

provided, quite literally, a shoulder to cry on − from the way he handled

the situation I guess I wasn’t

the first distraught parishioner he had comforted down the years.

Having sorted out some ecclesiastical difficulty − for he was the

curate, not the vicar − Ralph did conduct Jean’s funeral, in his

eulogy speaking as if he had known her all her life.

That was the last time Ralph and I spoke.

Subsequently, I saw him on odd occasions within waving distance, but

with the memory of tears at our earlier meetings still vivid in mind I

always felt too embarrassed to cross the road. Some years

later my second wife and I attended evensong at St. John the

Baptist, Aldbury, to find Ralph rather than the regular incumbent in

the pulpit. I cannot remember the text for his

sermon but I do recall how extremely well he preached.

Ralph died in 1999, aged 93.

A few years ago while looking into the

history of our local

windmills I came across the manuscript of Ralph’s unpublished autobiography. I read

it with interest, but did nothing further. A more recent visit to Heygates Flour Mill

− which

Ralph managed for many years − brought the manuscript back to mind.

Having reread it I felt that this interesting piece of local

history ought to be available

to the local community, so having tracked down his daughter Brenda −

now a successful hotelier in Cumbria − I obtained her permission to

publish on the Internet. |

A. Harvey-Taylor (Aylesbury)

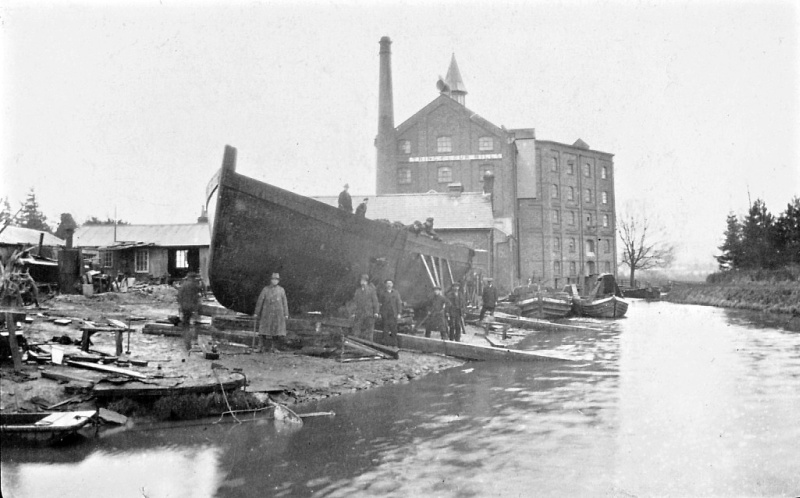

narrow boats at Tring Flour Mills on the Wendover Arm.

|

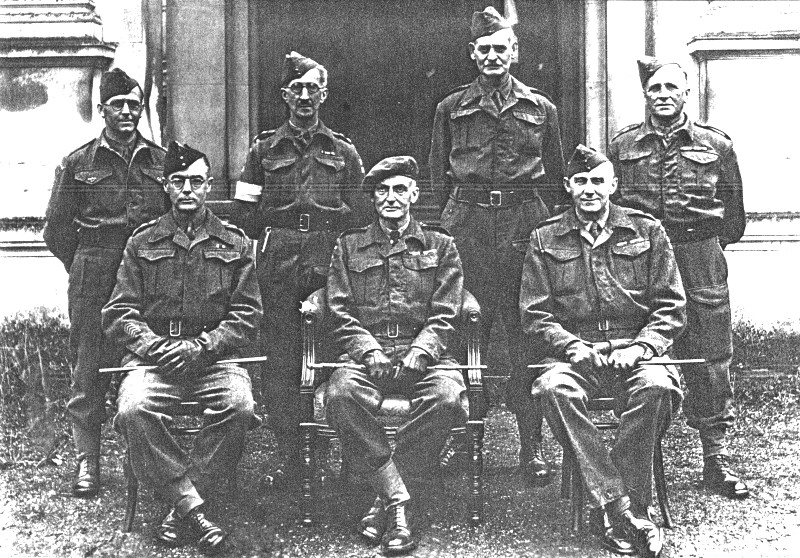

Ralph was born in Tring and served the Town all his life. As a

boy he began work in the corn industry, later moving to Wm N. Mead

Ltd. (now Heygates) Flour Mills at Tring (pictured above) where he became General

Manager. Being in a tied occupation, he served in the Home

Guard during World War II.

The Revd Ralph Seymour.

In 1973, by then aged 67, he applied successfully to study for the Anglican

ministry and entered

Cuddesdon College.

Ordained that

September, Ralph then served as Honorary Canon at Tring from 1973

until 1980 with permission to officiate until 1996. On his

90th birthday he took the communion service at the celebration held

for him at

Tring Parish Church.

Other roles that Ralph occupied in public life were as a member of

Tring Urban District Council (occupying the Chair on four separate

occasions) and later of the

Town

Council; as a Governor of

Tring School (1939-1973); and for many years as

a trustee of the

Tring

Charities serving for some years as Chairman. He also

served as both a committee member and Chairman of the Herts & Essex

Corn Merchants Association.

Ian Petticrew

February, 2017.

――――♦――――

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Wendy Austin, Mike Bass, Chris Hoare, Phil

Lawrence and Annette Reynolds for the text and images they

contributed, which together form a substantial part of the following

memoirs. Also Ralph’s daughter, Mrs Brenda Milsom, for her

permission to publish the material on the Internet.

――――♦――――

CONTENTS

BOYHOOD MEMORIES

THE

DUSTY MILLER IN TIMES OF PEACE 1919-1923

OF

FAMILY, HOUSES AND GARDENING 1923-1939

THE

WAR YEARS AND BEYOND 1939-1950

CHANGES AT THE MILL

SEVEN VICARS OF TRING

OBITUARY: RALPH SEYMOUR |

――――♦――――

|

BOYHOOD MEMORIES

MY EARLIEST YEARS

After I was born, my mother was quite seriously ill, and

consequently I was put out to a foster mother, a Mrs. Clarke in

Akeman Street. The house was double fronted with a central

passage on one side of which was the living room and on the other

side the sitting room.

My earliest recollection was the day the door to the sitting room

was open and in the centre of the room was a large basket of rosy

apples. I sidled on my bottom toward the apples for I could

not yet walk, only to be whipped and carried away by Mrs. Clarke

calling me a young varmit in the process. This happened each

time the door was left open. Meanwhile my sister Alice was

taken to live with an Aunt and Uncle at Old House Farm, High

Wycombe.

My father secured the help of a local woman who came in daily to do

the housework. My two brothers, younger than my sister, and my

older brother in his teens were also able to help. I fear that

father went through a very difficult period for a year or two.

For me this state affairs lasted until I could say a word or two.

One afternoon Mrs. Clarke took me up to see my mother whom I

addressed as the “Lady” because I addressed Mrs. Clarke as “Mummy”.

That night, apparently, my mother insisted that I was to come home

to live. Although still a semi-invalid she was able to ease

conditions in the home.

We then lived in 16 Longfield Road and houses were being built

opposite. By this time my mother was considerably improved

healthwise and was able to walk into the town. She had bought

me a linen sailor suit, my pride and joy. It had bell bottomed

trousers with blue piping, a lanyard and straw hat with “H. M. S.

Victory” proudly displayed on it.

One day mother had a friend come to stay for a few days. I was

rigged out in my sailor suit and told to be still and wait, while

the two ladies went to dress up for a walk. Well, my male

friends, you know how long this exercise takes with the ladies!

After what to me seemed hours, I could sit still no longer and went

down the passage and across the road to where the builders were

busy. There a heap of sand proved to be irresistible.

Eventually I heard by mother calling me. I went quickly saying

that I would not do it again for I knew I was in for trouble.

Off came my sailor suit and an ordinary one was put on.

During the time mother’s

friend was with us, she made a greengage suet pudding. When

this was taken out of the saucepan the covering cloth was streaked

with purple. I had only slipped in a piece of mauve crayon

while it was being prepared. It must have been a relief to

mother when, at the age five, I began my education by attending

Gravelly Infant’s School

(since demolished).

We had a large kitchen garden in addition to which father rented an

allotment at Duckmore Lane. The rent of a 10 pole plot was

five shillings per year (25p), but the Rothschild Estate to whom the

allotments belonged, issued a voucher to the value of seven

shillings and sixpence (37.5p) to all allotment holders. This

was exchangeable for beef at Christmas. Consequently, no plots

were uncultivated. So we were self supporting in potatoes and

fresh vegetables.

LIFE ON THE ALLOTMENT

As a staunch churchman, father taught us children to observe Sunday

very strictly − no work for him and no games for us. However,

he had an exception to this rule, as on Good Friday he would be busy

on his allotment. From about the age of ten years it was my

job to fetch up all the old brussel sprout stalks and burn them.

Having dug them up, I would pile them up in the form of at pyramid

and leave them for a week for all the sap to dry out. They

would then be mixed with the wood from the old peasticks, while

remaining in the pyramid form. The secret was to ensure that a

current of air would circulate through them. If you allowed

the pile to become flat, the fire would go out and you would have to

start all over again.

After a few years I was promoted to dig half a spit of soil ahead of

father. He was a perfectionist. “Now then, stand up over

your fork and lift the soil up and don’t pat it down. It needs

light and air.”

Before I graduated so to speak, I loved Sundays in the winter.

We would all site down including father, to our midday meal.

Then about 3 o’clock father

would go off to his allotment, bringing back, brussel sprouts,

turnips, parsnips and a stick of celery. Then in the gloaming

of the evening we would sit round the fire in the kitchen and mother

would usually set the ball rolling entertaining us with stories such

as “The Mistletoe Bough”. In this the bride of the day was

playing hide and seek with the wedding guests and hid in an old oak

chest, when the catch of the lid closed. “Did she really die?”

we would ask, and at the sad response I usually had tears running

down my cheeks. Then mother would start singing songs such as

“Do ye ken John Peel” and “Robin Adair”.

She was a wonderful raconteur. Oh that families could

participate in such simple joys today. It is the lack of

families joining in activities together which is largely the cause

of so many broken marriages today.

SATURDAY CHORES

When I reached the age of 13 it became my responsibility to do the

Saturday chores. First the Sunday shoes of the family had to be

checked and thoroughly cleaned and polished. Then the knives

had to be cleaned. They were steel and not stainless, as

stainless knives were not then in use. There was a special

board, an inch thick, nine inches wide and two feet long, to which

was glued a strip of soft leather. The board was then dusted

with Goddard’s knife powder. You then had to rub each knife up

and down the board until it shone and every little black spot was

removed. Then the kindling wood and coal for the fires had to

be replenished.

After these jobs were completed I had to wash and make myself tidy.

I then cycled to the town to collect one and half pounds of haslet

(lean pork from the side of a pig of 20 score or more).

Reaching home, this was put into a wooden bowl. Then some

bread was added, which had been soaked and then squeezed in a cloth

to expel excess moisture, also salt and pepper and dried sage

leaves. With the use of a half-moon shaped steel chopper, I

had to work to reduce the whole mixture to a fine texture until it

had satisfied my mother’s eagle eye.

In the season I then had to go to Hockney’s glass houses and buy two

pounds of splits or misshaped tomatoes; also some for normal use.

In the winter we used tinned tomatoes. On Sunday morning the

sausage meat was made into the shape of rissoles and then fried.

In the meantime rashers of home-cured bacon were fried together with

the tomatoes. What it feast for a hungry lad. I can

still recall the joy of it. Now, alas, plain country living

has disappeared to be replaced by packet breakfasts and calorie

lectures!

AN OUTING TO THE BRIDGWATER MONUMENT

Summer school holidays seemed to stretch on for ever, but by the

time I was 10 years old my mother’s

health had improved considerably so she would plan an occasional

outing for me and my sister. One of the most enjoyable was a

trip to Aldbury monument.

Food for the day was prepared and we would catch the horse bus from

what was then the Britannia public house at the bottom of Park Road.

This took us as far as Tring station and from there we would walk to

Aldbury and up to the Bridgewater column. Then we would have

our picnic lunch amid the beautiful surroundings of the woods with

the song of the birds for our orchestra.

Me and my sister were always eager to climb up the circular steps to

the top of the Column and we would arrive breathless to admire the

wonderful view of the surrounding countryside and Aldbury village

nestling below. Our climbs were usually limited to two in

number as each time one penny had to he paid for admittance.

What halcyon days they were!

We usually spent the afternoon exploring the many paths and glades

of the woods. By four o‘clock my mother had rested and tea was

called for. So we went to a cottage in the woods to procure,

for a small fee, boiling water for the brew and we then enjoyed the

goodies that mother had packed. Then we walked back to the

station to catch the horse bus back. Can you wonder that such

outings are enshrined in my happy memories?

EVENSONG AT DRAYTON BEAUCHAMP

Occasionally on Sunday evenings during the Summer months, mother

together with me and my sister would walk to a local country church

to attend Evensong. We often went to Drayton Beauchamp.

We walked along the county Herts-Bucks boundary over the fields.

Then we continued along the side of the “dry canal” [The

Wendover Arm - that section has now been restored].

There were three bells to the Church which were not rung but pealed.

As soon as we were able to hear them we would invariably sing “Fill

dung cart” which we thought was our own idea. Many years later

I preached at a Harvest Festival service and in doing so, mentioned

this fact. After the service a villager said, “You didn’t

finish your quotation, sir”. To my interest and surprise she

told me that the full version was “Fill dung cart, Bill Vinnicombe”,

and was well known. Despite many subsequent enquiries I could

never find out who Bill Vinnicombe was, or the origin of the ditty.

When we attended Evensong in my youth, the organist was Squire Jenny

who had the habit of rocking backwards and forwards as he played.

Drayton Beauchamp is a lovely church sat in rural surroundings.

It contains some exquisite stained glass windows.

St. Mary the Virgin, Drayton

Beauchamp

Suitably refreshed spiritually we walked back home to a supper of

cold meat from the Sunday joint and cold vegetables. I can

still in my memory recall the taste of new potatoes, peas, broad

beans etc. from father’s garden. How sad to think that today

countless people have never tasted fresh vegetables but rely upon

tinned and frozen varieties with their meals.

COLLECTING SHEEP MANURE

My father was a very good gardener, both for vegetables and for

flowers. He used to raise geraniums from cuttings and bedding

plants from seed in the conservatory at the front of the house.

For these he required fine mould, and so each Spring my brother and I

set off for Stubbins Wood, equipped with a wooden box mounted on an

old perambulator chassis, two small shovels and a hand sieve.

The box had originally held loose sugar which was then weighed out

into stout blue paper bags of either 1lb or 2lb by the grocer.

Upon reaching the wood we would search for a hollow where beech

leaves had piled up. Removing the top layers revealed lovely

rich mould, which we then riddled to remove large pieces of soil and

stones. To this rich soil, silver sand was added, which we

fetched from the builder’s merchants yard in Western Road.

Father grew tomatoes in the conservatory and also outdoors against

the corrugated iron fence of an old pig sty at the top of the garden

which retained the heat of the sun. If you enjoy a tomato,

then take one ripe direct from an outdoor plant warm from the sun.

To successfully raise his tomatoes father required sheep manure.

My brother and I would set off with small shovels and our Tate &

Lyle sugar box truck for Drayton Beauchamp which as you know has a

very steep hill. Now the left hand side is covered with scrub,

but at that time consisted of succulent grass.

The owner of Upper Farm, Drayton Beauchamp, owned a flock of

Hampshire Down sheep and from time to time they were brought to

graze the hillside; hence our source of droppings. This

particular morning there was a plentiful supply and we started to

fill up at once. We had almost reached the bottom of the hill

when we saw Daniel Heam the shepherd smoking his clay pipe.

“Well, Master Bill”, he said to my brother. “What do you

reckon you be up to?”. “Getting sheep droppings, Mr Heam, for

father’s tomatoes”, Bill replied. The response was “Well, you

two silly young beggars, you’ve got your truck well nigh full”.

“Yes, that’s that we came for”. “Yes, but why didn’t you bring

it down to the bottom of the hill empty, and fill it as you went up.

Now you’ve got to push it all the way up the hill full up”. A

lesson applied to life which I have never forgotten.

When we got back home the sheep droppings were transferred to a

hessian bag and left to soak in the rain water butt. This

supply was then used to add to the watering can. I can tell

you that the resultant fruit was absolutely delicious.

THE BILLETING OFFICER

One of the highlights of my youth was to go blackberrying.

One Saturday morning in early September in 1914 I set off to one of

my secret haunts. It entailed a walk of three miles or more,

but as I journeyed the prevailing mist rolled away to reveal a clear

sunny morning and the outstanding beauty of the hedgerows and large

wood through which I passed. Countless spiders’ webs bedecked

with beads of moisture sparkling in the sun. All was so still

that the song of the birds echoed everywhere. I could hear a

woodpecker tapping for his breakfast and the flash of colour and the

harsh cry of a jay added to my enjoyment.

However, I pushed on to my objective, a rough field with gorse

bushes into which the brambles clung covered in beautiful juicy

blackberries. I soon filled my two baskets and left for home

with visions of the blackberry and apple pie or pudding which mother

would make. On reaching home I was startled to see a chalk

mark of an inverted arrow on the front of the house with a figure 6

below.

A number of volunteers for the army who came from Northumberland

were due to be housed in Tring. As we had a fairly large house

the billeting officer had apportioned six to us who were to be

housed and fed. When father came home at mid-day he said that

mother was not to have any residents imposed on us due to her

indifferent health. He would go and see her doctor to get

exemption.

Mother had asserted that she could cope with two, Dr Brown told

father. However, some of the men were in rather bad “digs”.

Within a fortnight the two we had, had wheedled another two of their

pals in and within the month we were up to six. To give them

their due they were so pleased to be with us that they helped in

every possible way. So began mother’s war effort. The

first two thoroughly enjoyed the blackberry and apple pudding!! |

――――♦――――

|

THE DUSTY

MILLER IN TIMES OF

PEACE

1919-1923

IN THE BEGINNING

I began my working life at the age of 14 years, on the day after

Boxing Day in the year 1919, with Herbert Grange and Co., Corn

Merchants, who used premises for storage at Grove Farm, Tring, the

home of Mr. Herbert Grange, who was known as the ‘Maize King’.

Their main office was at Mark Lane, at the London Corn Exchange, the

Tring operations being under a manager, Mr. Walter Glasscock.

I started at the princely sum of ten shilling (50p) per week.

My hours were from 8.30 a.m. to 6.30 p.m. each weekday, with an hour

off for lunch, and from 8.30 a.m. to noon each Saturday.

It was common practice in those days for children to leave school at

the age of fourteen, and having reached that point in September, I

started looking round for employment. I had no job in view

until I heard at school one day towards the end of the term, that an

office boy was required at Grove Farm, and I went there straight

from school, without telling my parents. I had to wait until

5.30 p.m., when the manager returned from Mark Lane, but my

perseverance paid off and I got the job.

When I got home, considerably later than usual, and my parents

wanted to know where I had been, I explained, and told them about

the job. Father asked: “Do you think you are going to like

it?” I replied that I didn’t know, but if not . . . . Here

father cut me short, and said: “Oh no, my boy. If you start

something you have to see it through.”

I asked my mother if I could have a new suit with long trousers as

all my mates were wearing. “You will do no such thing. Your

present trousers are perfectly alright for continued wear".

However, I was determined to have my suit with long trousers.

Of the ten shillings wage, seven shillings and sixpence went toward

the cost of my ‘keep‘ and two shillings towards the cost of my

clothing. So I went to see Mr. Cross the tailor whose shop was

at the comer of Christchurch Road to ask if he would make me a suit

for Easter. I settled for a grey herring bone tweed for the

price of five guineas. I explained my circumstances to him.

By Easter Saturday, I would be able to give him three pounds, but

would it be agreeable if I paid him my two shillings and sixpence

after that to clear the balance?

I left the office at midday on the Saturday and cycled home with my

suit in a brown paper parcel. “What have you got in that

parcel?” my mother wanted to know. I explained the arrangement

for payment to Mr. Cross the tailor. “You young devil! I

told you that you were not to have a new suit. I have never

yet had anything on tick and I am not going to do so now”. She

flounced upstairs and came back holding two pounds five shillings.

“You go straight back to Mr. Cross with it and have the bill

receipted, and you will give me the full ten shillings each week

until the balance is paid”. She kept me strictly to it.

As soon as I was home from Church each Sunday I put the jacket on a

chair in the sitting room and donned an old jacket. My father

had a friend who a carpenter, Mark Osborne in Miswell Lane. I

went to him and persuaded him to lend me two lengths of plywood

about 30 inches long twelve inches wide. Every Sunday night

when going to bed I lifted up the mattress to lay my trousers

underneath to keep the creases in. It is a sound maxim of life

that if something is gained easily the less it is valued, but if

self denial and hardship are needed to achieve your object so will

you value it, as I did my suit with the long trousers.

The office was a ramshackle building attached to the farm buildings,

but I found the work interesting. There was a constant flow of

people in and out, either bringing in grain, or taking out feeding

stuffs, or both! I was required to do a bit of everything, and

I can honestly say I was keen on my work, and anxious to learn.

Gradually I became a proficient judge of grain quality, which in

those days was judged by natural means − smelling, weighing in the

hand, looking for signs of disease, or wild garlic, or smut.

The latter is a fungus, which gives off a noxious smell from the

infected grain. Testing also involved biting the grain, and

grasping it in the hand, to assess moisture content. Today the

miller or merchant has highly technical apparatus at his disposal to

enable quick and searching tests to be made.

In view of my interest, by the time I was sixteen I was entrusted to

call on farmers to sell feeding stuffs and to buy grain. It

was the custom in the trade to secure a sample of any grain for sale

on a farm by collecting at least half a pound, taken from at least

twelve sacks at random. By this means you found out if there

was an odd sack or two out of condition and reacted accordingly.

The manager kept some fifty or so laying hens at his home, so I was

frequently adjured to “Bring a large enough sample, Seymour.”

If the grain was bought, when it was delivered it was matched

against the sample, and if all was in order the sample was finished

with, and was tipped into a bushel measure in the office, to become

the manager’s perks. In the season he usually took home, in an

old Gladstone bag, sufficient corn to feed his hens!

As the farm buildings were in use for storing grain and feeding

stuffs, as well as ordinary farming operations, there were always

rats about. Periodically efforts were made to reduce this rat

population, and ferrets were used in this. If the manager was

at market, or elsewhere, I found ratting more attractive than office

work. By then we had a younger office boy, and I would

alternate shifts with him − one in the office, one outside ratting.

On one occasion the ferrets failed to get the rats to move from

under a row of pig sties, so the farm manager decided to test the

fire hose, and at the same time flush the rats out with the water.

The farm lads and I waited to deal with them if they ran.

Suddenly five or six bolted at once, and one lad struck at one of

them, hitting it over the back. The rat scrabbled away, and

the lad’s second attempt was equally unsuccessful. One old man

watching could contain himself no longer, and exclaimed: “Hit ‘un

over the ‘ead boy, the arse’ll die of itself!”

Mr. Grange normally went to Mark Lane, or his London office, every

day, but when he was at home cable messages, all in code, would come

for him, over the telephone. In these cases it was my job to

go to his private house, get the code book, and decode the message

before giving it to him. I would then be given a reply in

longhand by Mr. Grange, which I had to translate into the

appropriate code before relaying the answer.

There could be enormous variations in market prices from day to day.

On one occasion I know that Mr. Grange, in his maize dealings, lost

£3,000 in one day, when the bottom dropped out of the market.

One day I was told to cycle to a farm some four miles away, to look

at some wheat the farmer had for sale. I was told to bid for

it, up to a given limit, according to quality. The farmer had

a very attractive daughter of my age, which delayed me somewhat, but

eventually I went into the barn with the farmer, to draw the usual

sample, which I put in a bag which would hold up to about 3 pounds

in weight. He watched me filling this with much interest, and

then asked: “How did you get here, young ‘un?” Puzzled, I

replied: “On my cycle, sir.” “That’s a pity,” he said, “For

you might as well have taken a sackful!”

Now, it was a cardinal rule that you ascertained the quantity of a

parcel of grain by counting the number of sacks but, owing to the

fact that the farmer’s daughter had followed us into the barn, I

neglected this essential duty! Then I found that I couldn’t

buy the wheat within the limit I had been given, so I set off back

to the office with the sample. The manager looked at it and,

of course, asked the quantity. The startled look on my face

told him I didn’t know, and I was told, in no uncertain terms, to

“Ruddy well go back and count it now!”

Off I went back to the farm, feeling the biggest fool on earth.

The farmer thought I had gone back to accept his asking price, and I

had to explain myself. Never, in all my subsequent fifty years

in the grain trade, did I make that mistake again. You learnt

in a hard school in those days.

At least I drew genuine samples, not like one farmer. One day

a lad brought in a very good sample of barley, and even the manager

said he didn’t think he’d seen a better sample. “I’ve brought

it in for me dad, because he’s not well,” said the lad. “And

it ought to be good. It took me sister three or four hours

this morning to pick it out!”

On another occasion I was offered ten hundredweights of ‘swede’

seed. Feeling pleased with myself I took the sample back for

the manager’s inspection, only to be told that I should learn the

difference between swede seed and charlock (a weed seed of very

similar appearance).

After I had been with Grange’s for nearly five years, my wages had

risen to thirty shillings a week, but when I asked for another rise

he said he couldn’t afford to pay more. In any case, I was

beginning to feel that I needed to enlarge my knowledge and

experience, so I went to see Mr. William N. Mead, at the flour mill

at New Mill, with whom I had had contact previously, through selling

him wheat. I asked him if he knew of anyone who would take a

young chap who wanted to learn milling. He told me he would

make enquiries and to go back and see him in a week’s time.

An early picture of the Tring

Flour Mill. The

windmill was pulled down

in 1911.

One week later I returned, and he offered me a job at the mill.

I returned to Grove Farm and immediately handed in a three-week

notice. The usual was one week, but I extended it, with Mr,

Mead’s agreement, to enable me to tidy up things. Upon

receiving this notice the manager at once offered me £3.00 a week −

double my present thirty shillings − to stay.

“Sorry,” I said, “But it is time you and I parted. If you

couldn’t afford more than thirty shillings last week, but now offer

to double it, I don’t want to bankrupt the firm.” So I left,

and he never spoke to me again.

At the mill I found things very different. Mr. Mead not only

owned the mill, but he also farmed extensively, both in Tring, at

Silk Mill Farm, and also at Marsworth, at Hospital Farm, sometimes

called Manor Farm. In fact, during hay and harvest times − and

on other occasions if necessary − if extra men were required on the

farms, he had no hesitation in shutting the mill and taking all the

men employed there down to the farms for as long as they were

required. In the mill yard itself, he also ran a retail coal

business.

Bushell Bros. boat yard. Tring

Flour Mill is in the background.

At the bottom of the mill yard there was a boat building and repair

business, for the canal barges, owned by the Bushell Bros.

This business actually continued until after the Second World War.

When I joined the mill staff, there was only one man, other than Mr.

Mead himself, in the office. This was Teddy Clark, who was

employed as clerk, cashier and accountant, and he kept the ledgers

meticulously, with each name written in beautiful copperplate

writing. There was also a flour traveller, Harold Saunders.

Mr. Mead was always known as ‘the Governor’, and I very soon got the

nickname of ‘Chikko’, which came about when I found there were some

residues going to waste, and experimented with them, making up some

samples of chick corn. The Governor’s two daughters − who were

always about the yard − heard of this, and gave me the name. I

didn’t mind, and it stuck!

For the first fortnight or so I was put into the mill, to learn my

way around, and on the first day I was set to lower some empty flour

bags from the top floor, where they were then stored (later we had a

sack-warehouse). There were flaps in each floor which could be

opened, so that with the aid of a hoist, bundles of bags could be

lower right through to the basement. I soon got the hang of

it, and was letting bundles down quite speedily.

Unfortunately, however, one bundle went down a bit too fast, and

arrived just as the mill foreman was walking under the open flap and

it knocked him sideways. Although I assured him it was

accidental, all the time I knew him I felt he was never certain that

it was!

I also put my foot in it early on in my time in the mill office.

In those days phones were in very short supply, and people would

come in and ask to use our phone. The Governor got fed up with

this, and told us that if anybody came in to use the phone we were

to charge them sixpence for each call, no matter who it was or what

the call was for. With this in mind, when a gentleman came in,

in full hunting kit, demanding: “Use your phone, boy!”, I told him

to go ahead. When he put the received down, I asked him for

the required sixpence. “Sixpence! What for?” he demanded.

I explained. He was furious. “Daylight robbery!” he exclaimed,

but he flung sixpence on the desk and stormed out.

It wasn’t until a few weeks later that the Governor told me I had

demanded sixpence from Lord Rosebery, one of his best customers.

I pointed out: “That was your orders, sir. I only did as I was

told.” That was the last I heard of it!

PRODUCTION OF FLOUR

My initiation into flour production was a complete revelation.

Hitherto I had assumed that a fairly simple grinding process of

wheat was involved. Instead I found it to be a highly skilled

and technical operation.

Wheat, according to availability and cost, was shipped in from many

countries, all with varying moisture content − as low as 12% in that

from India, Russia and the Argentine, to as high as our native wheat

at 16%. Manitoba Wheat from Canada was graded in quality from

No.1 to No.4, the latter containing some immature grains.

Mr. and Mrs. Ward, daughter

Phoebe and her children from Startops End at the Tring Flour Mills

on the Wendover Arm. They had delivered a cargo of Manitoba wheat.

IRIS was owned by A. Harvey-Taylor of Aylesbury and registered at

Tring.

All imported wheats were brought from the London Docks by barge to

the canal alongside the mill. A barge and a ‘butty’ − an

engineless trailer − together carried up to 60 tons, in sacks of 250

lbs. Hoisted from the barges by chain, the contents of the

bags were shot into a hopper, from which the wheat was conveyed by

elevator cups on an endless belt to the top storey of the mill into

holding bins.

Before the actual milling process began wheats were blended into

what was called the grist. The foot of each storage bin had a

calibrated release on a ratchet principle so that this could be set

and the correct quantity of each wheat released. All the

wheats contained extraneous matter to some extent, so the next

process was to remove this by a most exhaustive cleaning process, so

that sound grain, free from all impurities, resulted. By

various elevators this was then fed into a washing process, and from

there into a screen-meshed whizzer, to remove excess moisture.

The next process was to feed it into a heated container to open the

pores of the skin of the wheat, and then on to a cold container to

close the pores up again. The grist was then put into a

conditioning bin for 24 hours, with the result that drier grain

absorbed moisture from the damper, and a level moisture of about 16%

was arrived at, ready for the milling process.

The strongest gluten cells of the grain are towards the outer skin,

so the object of the treatment is to scrape them free without

breaking up the outer skin. A series of chilled steel spiral

rolls were employed, the first with serrations of four to the inch,

the top one of two revolving at a differential speed of 2 to 1, thus

opening the grain wide with a shearing action. The subsequent

rolls were serrated progressively less acutely. The release

from these was elevated to the top storey of the mill into a most

ingenious machine called a plansifter. This consisted of an

outer wood casing containing no less than 12 sieves, from a coarse

wire mesh at the top to a fine one at the bottom. The whole

plansifter was suspended from the ceiling attached to 16 flexible

bamboo rods. Under the bottom was an elliptical weight which,

when in motion, afforded a perfect sieving motion.

The releases from this operation were fed back to the roller floor,

the coarsest to the second rolls, and according to the grading, to

each appropriate roll, and a final pair of smooth rollers.

Meanwhile, the finer separations from the plansifter were fed to the

enclosed cylinders inclined at an angle but clothed with coarsely

meshed cloth. The finer release was then fed to the next

machine clothed with finer mesh, and the over- tail despatched to

the last sequence of the rolls.

The resultant fine release was now actual flour, which was fed to a

holding bin, from where it was bagged up by an operative into jute

bags weighing 140 lbs. nett. (Nowadays it is packed into 32 kgs.

stiff paper bags, or alternatively stored in a glass-lined bin, from

which it is loaded into bulk lorries, and at the bakeries blown from

the lorries by means of compressed air into the bakers’ bins.)

ONWARD AND UPWARD

Life at the mill was never dull. On one occasion the Governor

fell out with one of the men and told him to go to the office and

get his cards. “I shan’t!” said the man. “You will!”

said the Governor. “If you don’t know when you’ve got a good

man, I know when I’ve got a good boss!” was the reply. He

continued to work for us for some months afterwards, but was

eventually sacked.

The Governor was furious with anyone who untied a sack of corn for

some reason and left the mouth open. One day he was passing a

stack of corn sacks and noticed someone had left the mouths of three

open. An employee, by the nickname of ‘Choice’, was passing at

the time, and was promptly torn off a strip by the Governor.

Choice was innocent of the offence and said: “Look here, Governor, I

don’t mind being blamed for what I have done, but I ain’t being told

off for what I ain’t done! Another thing, I’ve been going to

ask you for a rise for a long time. You ain’t paying me

enough!” As I was on the spot I tried to suppress a grin −

unsuccessfully. “How much are we paying Choice, Chikko?” asked

the Governor. “Not enough, sir” I said. He was a good

workman, so recourse to the office secured Choice a rise of five

shillings a week.

I began to sell the whole range of animal feeding stuffs needed by

farmers. I also bought grain from them, with the exception of

English wheat for milling. That was definitely the Governor’s

province. That not suitable for milling I could buy, provided

I made a profit when selling it on!

To start with my operations were confined to farms within cycling

distance, but after two years I bought an AJS motor cycle, which

considerably extended my range. I was, of course, on a salary

basis, and had some difficulty in extracting an allowance from the

Governor for using my own motor cycle.

After twelve months I became tired of being out in all weathers on

the motor cycle, and I tackled the Governor about assisting me to

purchase an Austin motor car. I had by then been employed by

him for 5 years, and had successfully developed a thriving animal

feeding stuffs business. I suggested that I could also try to

sell flour. I pointed out to him that the mill was being run

uneconomically as it was producing 4 sacks of flour an hour (packed

in two half—sacks of 140 lbs. weight) and was running only 8 hours a

day, for five days each week. The solution was to sell more

flour! I would not interfere with the existing flour salesman

s customers, but would break fresh ground.

I tried to secure one shilling (5p) per sack commission for all new

business, but the Governor would not budge from sixpence per sack

(2p). In 1937, my flour sales were such that the Governor said

he could no longer afford the commission of sixpence per sack, but

instead would give me a share of the profits.

In 1938 he formed the mill into a private limited company, with

6,500 shares, of which half were issued. The major number he

held for himself, giving 1,000 each to his two daughters. Six

months later, he told me he was giving me 400 shares, but I never

drew a dividend, as such.

Competition was really keen. Sometimes as many as ten

travellers from as many millers were calling on one small country

baker. However, in selling you have first to ‘sell’ yourself

to the prospective customer. If your face fits you have then

only to prove the quality and competitive price of your goods.

NAMES, NICKNAMES AND YARNS

One of my best farm customers was Dwight‘s Pheasantries of

Berkhamsted, then the largest pheasant farm in Europe. One day

Percy Dwight asked me to do him a favour by delivering a few bags of

layers mash and mixed corn to a friend of his, a member of the

Tyrwhitt Drake family, who kept some hens in his paddock.

Accordingly Bert Heley, one of our lorrymen, was given job of

delivery. He did the job, but came back to the office raving

mad! “I’m not going to deliver to that man again,” he said.

“He was as nice as pie when I stacked the food in the shed − gave me

two bob (shillings), and chatted with me. Then he asked me

where I had been to school, and I told him. He called me a

ruddy liar!”

Two of the Governor’s lorrymen

with their Sentinel steamer.

Now Bert was born and had gone to school at Eaton Bray, but the

locals never called it anything but ‘Eaton’. It took me some

minutes to pacify him, explaining that his Eaton had been mistaken

for Eton College.

The abbreviation of place names was quite common practice, often

with a long ‘AR’ − so Aston Clinton became ‘Arson’; Drayton

Beauchamp was just ‘Drayton’; Long Marston was Marson’, while Hemel

Hempstead was shortened to just ‘Hemel’, and Berkhamsted became ‘Berko’,

and so on.

Apart from place names being localised, many of the local people had

their own personal nicknames, which were often passed from father to

son. Some examples which come to mind are:

‘Sausage’ Harrop; ‘Niddie’ Bradding; ‘Ponny’ French; ‘Wiggle’

Barber; ‘Spivvy’ Budd; ‘Puffy’ Howlett; ‘Totty’ Ives; ‘Packer’

Brooks; ‘Nippy’ Hearn; ‘Dekko’ Budd, and ‘Splash’ Harry. I have

already mentioned ‘Stumpy’ Cato, and ‘Bumper’ Eggleton. There was

also a family in Tring named Higby, each of whose sons had a

nickname — the aforementioned ‘Choice’, ‘Jammy’, ‘Knock’ and ‘Inkerman’.

Some of the names were given for obvious reasons, but many were not!

I once queried how ‘Dekko’ Budd got a name like that. “I can

tell you,” said his sister. “Because he was always poking his

nose into other people‘s business!”

Another man was known as ‘Bent Axle’ − a very cruel nickname, as the

man concerned had suffered a broken leg in his youth, which had been

improperly set so that it was permanently bent.

There were many local characters, of course, who did not have

nicknames. One was the late Arthur Macdonald Brown. He

always employed a chauffeur to ferry him around − particularly when

he visited the Ashridge estate, which for some years he overlooked.

The drill was that he would go in the morning, have a look round,

and then break off a midday, to go to the ‘Bridgewater Arms’ for a

sandwich and a drink. His usual chauffeur had retired, and a

new one was employed. On his first day taking Macdonald Brown

round the estate, they went to the Bridgewater Arms as usual, where

Macdonald Brown turned to the chauffeur and asked: “What about you,

Tofield? You like a drink?” “I don’t mind if I do, sir,”

was the reply. “Well,” said Macdonald Brown, “I do. I’d

have to damn well pay for it!” And he never did buy him a

drink, during all the nine or ten years that Tofield chauffeured

him.

Another local character, who suffered from a heart condition, was

notoriously mean. He always carried a small bottle of brandy

on him, in a blue glass bottle. At that time the law ordained

that any liquid of a poisonous nature must be carried in a blue

glass bottle, and thus no-one would touch the brandy! On one

occasion, however, while awaiting his turn for a hair cut he felt

faint, so took out his brandy bottle, but before he could drink any

the barber saw it and knocked the bottle to the floor saying: “No

you don’t, you old devil, you ain’t committing suicide here!”

“You foolish, interfering man, you’ve spilt all my brandy,” stormed

the man, as evidence of which the bottle was in fragments, and a

lovely aroma of brandy filled the saloon.

Another character, by the name of Charlie, is worth a mention.

He had a lovely turn of phrase. On one occasion he went to a

local butcher and asked for a pig’s head. “Alright, Charlie,”

said the butcher. “I shall be slaughtering on Tuesday, so if

you come in on Wednesday I shall be able to fit you up.” So on

Wednesday Charlie arrived at the shop and the butcher got his

carving knife poised. “Now then, Charlie, how far shall I go

back?” he asked. “As near the arse as you likes, boy,” he was

told.

One day Charlie came into the office, and was asked how things were

going on. “Well,” he said, “I’ve got a touch of financial

cramp!”

THE MEAD CLAN

The Governor had an uncle who lived in a large house in Station

Road, Tring, which had an adjoining paddock and stable. He

employed a coachman-cum-gardener, who drove him around in an open

carriage. The pony was getting on in years, and if it became a

bit sluggish the old man would call out to the coachman: “Touch him

up, John. Touch him up!”

One Christmas all the relatives gathered together, as usual, for a

party, and a game of charades ensued. My Governor, always fond

of a leg pull, enlisted the help of an accomplice as coachman, and

went into the drawing room mimicking his uncle, calling: “Touch him

up, John!” Unfortunately the joke misfired, and the old man

took umbrage. Shortly afterwards he altered his will and

struck the Governor’s name off. In consequence that game of

charades cost him £12,000.

The same man was not exactly generous minded, and once, when two

workmen were making alterations and repairs in one of the bedrooms,

put a sovereign coin under the carpet where he knew they would see

it. The next day the workmen asked him to come to the bedroom

to give his instructions about the work to be done, and when he did

so, they lifted up the edge of the carpet to display his pound coin

nailed down securely to the floor boards, saying: “We thought you’d

like to know where to find it another day!”

Another nephew of the old man, named Percy Mead, farmed locally, and

worshipped at New Mill Baptist Chapel. At that time a new

tenant came to Dunsley Farm, Tring, and the two became friendly.

As the incoming farmer was short of hay and straw until the next

harvest, Percy supplied him with sufficient of both to last some

time. Unfortunately the new man was also short of capital, and

no money was forthcoming for two or three months, so Percy sent him

a postcard with just a biblical text on. In response he also

received a postcard with a biblical text on.

Percy’s card read: “I was a stranger and ye took me in.” (St.

Matthew’s Gospel, Chapter 26, Verse 35). The response was:

“have patience, friend, and I will pay thee all.” (St. Matthew’s

Gospel, Chapter 19, Verse 29).

Percy had one particular field in which he grew delicious white

turnips, and his new friend, in due season, was supplied with some.

Then there was a rift in the friendship, so no more turnips.

One day, Percy saw his erstwhile friend climbing over his field

gate, having helped himself to some. Percy later went to his

brother-in-law, R. Sallery, a butcher in Tring, and bought two

breasts of lamb. He gave one of the butcher boys sixpence and

sent him up to Dunsley Farm with the strict instructions to say they

were sent with the compliments of Mr. Percy Mead, to go with the

turnips he had stolen.

My Governor and Percy were brothers, but they loved to ‘take the mickey’ out of one another. Percy was tenant of some ground

below the mill, owned by the local council, as part of the sewage

works, where an open irrigation system was employed. From time

to time sewerage liquor was directed over the ground in rotation.

Consequently Percy was always able to grow exceptionally large

mangel wurzels there, and each October he would invariably search

for two of the largest specimens and place them, one on either side

of the door to the mill office, much to the Governor’s chagrin.

The Governor, William Mead

While on a Mediterranean cruise one year, the Governor met a member

of the seed family of Cundy, who were introducing a new strain of

mangel called, I believe, Red Chief, so some of the seed was

ordered, and in due course arrived. “Now then, Chikko,” asked

the Governor of me, “How can we grow some of these to match brother

Percy?” “As much farmyard manure as you can plough in,

together with half a ton of I.C.I. No.1 complete fertilizer to the

acre,” was my advice. “You’ll ruin the Bank of England!” he

said. “Alright, then, just treat one acre, and see how it

works,” I suggested. This was done.

October arrived, and eventually the Governor brought up two large

red mangels, placing them one on either side of the office door,

where Percy would see them. When he did, Percy said

scathingly: “What have you got there, beetroot?”

“No,” replied the Governor, “Radish!”

“If I couldn’t grow better mangels than them, I’d give up trying.

I’ll show you what mangels should be like,” said Percy,

disappearing. A few minutes later he was back in the yard.

Taking two yellow mangels out of his car, and putting on an act of

puffing and staggering, he put them alongside the two reds.

They were certainly slightly larger than the Governor’s.

“That’s what I call mangels,” said Percy with glee. “They’re

as hollow as your head is,” said the Governor. Striving to

keep the peace between this now personal confrontation, I said: “We

can soon prove it, sir,” and fetched an old cutlass, which hung on a

wall in what we called the tin officer although it was actually the

coal office.

“Shall I split them in half, or will you?” I asked the Governor.

“I will,” he said, and gave one of his a hefty swipe with the

cutlass, revealing a perfectly ringed, solid root. When Percy

sliced his, there was a hole as big as a tennis ball in the centre.

“What did I tell you?” crowed the Governor. Percy turned on

his heel and shot off in his car as if the devil had kicked him

endways! We saw nothing of him for some days, although it was

his normal custom to call on us nearly every day. That night I

asked the Governor for a rise, and got it!

Mind you, if the Governor wanted something, or something done, he

went all out for it, and not always in the most obvious way!

Due to his strong connections with Marsworth he used to attend the

parish church there. It so happened that the vicar at

Marsworth retired, and there was a long interregnum, so much so that

the Governor got very cross about it. Despite making

application on more than one occasion to the Bishop of Oxford,

nothing happened. His patience beings exhausted, the Governor

had an advertisement placed in the Bucks Herald, which read:

“Wanted. Shepherd for an unruly flock of about 300 head.

Apply in the first instance to William N. Mead, Gamnel Mill House.”

Of course, one or two genuine shepherds applied, but the Governor

told them they were not quite suitable. He reimbursed them,

and made sure they were not out of pocket. The whole affair

caused so much fun and ridicule, however, that an appointment was

made within a bew weeks of the advertisement appearing.

This was typical, and Percy was just as bad! On the outskirts

of Tring at the junction of the old A41, Brook Street and Station

Road, was a wide Y-shaped area. Percy Mead badgered the

Tring Urban District councillors to have a traffic island erected

there with ‘Keep Left’ bollards to alleviate an obvious potential

traffic hazard, but neither the local council nor the County Council

was interested. Thus, every day except Sunday and for some

weeks Percy planted a large empty pickled onion jar in the centre of

this space, which he filled with wild flowers or flowering shrubs.

As fast as one jar was removed he replaced it. The resulting

amusement and publicity had the desired effect and eventually a

traffic island was placed there for the safety of all concerned.

RECOLLECTIONS OF FARMERS

Percy drove a succession of old ‘bangers’, one of which was an

Austin 12 Tourer. The glass windscreen of this had been

broken, so he replaced half the depth of the screen with a piece of

plywood, leaving the other half open to the elements. Anything

from dogs to pigs were carried in this car, covered, if necessary,

by a pig net.

One day he brought some store pigs for sale to Aylesbury Market and

after penning them went to the auctioneer’s office to book them in.

On returning to the car he saw a young policeman looking at the

licence disc stuck to his ‘windscreen’, which was obviously out of

date. He promptly sauntered down to his pen of pigs and

surreptitiously undid the gate, letting them loose in the yard and

immediately creating a hullabaloo. Several people rushed to

help including the young ‘bobby’. Seeing him safely occupied

Percy drove his car away. Some minutes later he drove into the

market again grinning all over his face, having been to the adjacent

county office to secure a new licence disc.

On another occasion at Aylesbury Market, two farmers were in

conversation, one of whom owed the Mill for feeding stuffs. I

approached them. “I suppose you want some money, young ‘un,”

said the man. “Yes, sir, if you please,” I replied.

Before my man could answer his companion spoke up: “I never

owe money. I pay as I go along” he said, to which the other

replied: “I owe the corn merchant, the vet, and the implement

blokes. You want to do the same, you get better service that

way.” “Good Lord, Jim,” said his friend, “It would worry me to

death if I owed money like that.” “Ah!” was the response,

“That’s where you make a mistake. It’s the folks as I owe it

to does the worrying!”

On market day many farmers would stay the whole day at the “Rose &

Crown”, or the “Robin Hood”. On one occasion this was the case

with Bill, who came from a farm a few miles out of the town.

At about 7 p.m. a man called at the farm to see him about some

business, and his wife explained and told the man where her husband

could be found. She asked if he was going home through Tring

and when he said he could, she said she would go with him and find

her husband. As they got to the “Rose & Crown”, a pal of

Bill’s was looking out of the taproom window, and exclaimed: “Bill!

There’s your missus just getting out of Thorpe’s trap and is coming

in!” “Oh is she,” said Bill, and as she went into the saloon

bar to ask for him, he went out of the other door and, unhitching

his pony, set off under the arch. She saw him and came running

out.

“I’ve come to fetch you back home,” she called. “Have you?”

said Bill. “How did you get here?” “Mr.Thorpe brought

me. He wanted to see you about some business,” she explained,

“But I’ll come home with you.” “You won’t,” said Bill.

“He brought you in, he can take you back” and off he drove.

Mr. Thorpe, however, had decided against doing any business with

Bill that evening and had driven home. She was left standing

and had to get a taxicab to take her back to the farm!

Milk was retailed in those days by farmers calling round to the

houses, often with a can holding 2 or 3 gallons, and it was measured

out into the customers’ own jugs. It had to conform to a

certain standard, but it was not at all unknown for water to be

added before being sold, and inspectors went round periodically to

check for this. One farmer was going round New Mill with his

churn of milk for sale when he saw an inspector coming and promptly

‘tripped over a straw’, and spilt all his milk onto the ground, thus

preventing the inspector from taking a sample.

A farmer friend of mine hunted once or twice a week, and he used to

use his cattle truck as a horse box. A neighbouring gentleman

farmer − a member of Lloyds − one day asked if, instead of hacking

to the meet, he could put his horse into Norman’s lorry, to which

Norman agreed. This arrangement went on for some two seasons,

but no offer was made towards the cost of petrol, or anything, and

eventually Norman dropped a small hint. “Ah,” said the Lloyd’s

man, “I’m going to America next week, Norman. I’ll bring you

back some cigars.” When he came back he duly presented Norman with

his cigars − two single King Edwards. I don’t think Norman’s

remarks were printable!

Many years later, after the war, we had a terrific tornado one

Sunday evening. It caused extensive local damage, ripping off

roofs including that of the school at Aston Clinton. It

brought down countless telephone wires, trees, etc., and lifted

portable sheds and buildings, blowing them away like toys.

Naturally, it was a fruitful source of conversation for some time as

people related their own experiences of it. Discussing the

damage with a small farmer with whom I did business at Aylesbury

Market, I asked: “How did you fare on Sunday, Frank?” “Frit me

to death,” he said. “I was in the milking shed and I thought

the end of the world had come, so I went inside and made me will.”

When I asked what blooming good that would have been, he looked at

me for a minute and then said: “Never thought of that, chap!”

The easiest ‘draw’ I ever made was not on the customer’s premises,

or at market, but was the outcome of a chance meeting with a farmer

who was ‘in our ribs’, who attended a dinner where I was present.

During the lull between the dinner and the speeches and the

entertainment, we had to queue for the ‘Gents’, and he chanced to be

immediately in front of me. Glancing round he said: “Hallo,

how are you?” to which I replied “Still waiting.” “Is that

meant to be funny?” he asked. “Could be,” I responded.

On the following Monday morning I received a cheque for £500 ‘on

account’.

By this time I had established a general corn merchandising business

in addition to selling flour. Normally I attended Thame cattle

market each Tuesday and Aylesbury cattle market every Wednesday and

Saturday, both to sell feeding stuffs and to buy English wheat and

barley. I was now permitted to buy wheat suitable for our own

milling and barley for barley meal; this we ground ourselves, for

which purpose we ran three pairs of mill stones. Choice Higby

was in charge of these and was a skilled dresser for them. The

lower stone was the bedstone and the upper one rotated more quickly.

The barley − or sometimes oats or maize − was fed into the eye of

the stones. The resulting meal was caught in a hopper

underneath and then channelled into a sack hooked onto the delivery

spout.

Millstone

The dressing was varied for different pairs of stones. When

they became dull in use, they had to be lifted out by Morris lifting

tackle, for they weighed several hundredweights each. They

were then laid horizontally and new faces were then chipped into

them using a mill ‘hammer’. Because they were of extremely

hard granite, the mill hammer had hard chilled steel chisel blades,

locked into a wooden handle. By much hard work, Choice would

chip diagonal crisscross furrows, which were expertly inclined to

feed the meal to the outside of the stones. He had to wear

goggles while doing the work, for little specks of stone and sparks

would fly off as he chipped.

|

|

|

A stone dresser

using a 'mill bill' |

One particular farmer was a very good customer for barley meal, as

he kept pigs. Normally I did business with him at Aylesbury

market. If making a journey locally, or taking the missus for

a ride, it was his custom to attach to the back of his car an empty

trailer with a pig net, so he could call on possible sources of

store pigs (young pigs bought for fattening to porkers). He

phoned me one Saturday morning before I went to the market to say he

wouldn’t see me there that week. He explained that his wife

had been unwell and had been away for some ten days, and he was

going to fetch her back over the weekend. Foolishly I said: “I

suppose you’ll take your trailer and pig net?” The rejoinder

came smartly. “Why, did you want to come?”

PRANKS BY THE GOVERNOR’S DAUGHTERS

By this time I had bought my first car, a Baby Austin. I can

still remember the registration number − PP 9154. It had

celluloid side curtains and a collapsible hood, and was my pride and

joy. I took delivery from a local garage early one morning,

but alas for the shining paintwork pouring rain set in, so I drove

it into one of the empty lorry sheds at the mill and closed the

door.

When I went to go home, the engine refused to start. Soon I

had several of the men around offering all sorts of suggestions and

help. Then to my consternation and chagrin and amid much

ribald laughter I saw the Governor’s two daughters, who were on

holiday from school, arriving with one of the mill horses together

with chains. “Are you in trouble, Chikko?” they asked.

“We’ll help and give you a tow.” I put as good a face as

possible on it, amid the general amusement, and soon spotted the

trouble. While I had been busy in the office the girls had

gone into the shed and altered the sparking plug leads.

The Governor had only the two girls. Both attended Roedean

School, which they hated. They were never happier than when

riding, hunting, or attending to the various dogs of which there

were several, ranging from a small terrier to two old English sheep

dogs. They were close together in age and not much younger

than myself. When they were on school holiday and, indeed,

when they came home permanently, there was a constant battle of wits

between us. One dark evening I started the engine of my car,

engaged the clutch and first gear to move off, but the engine just

‘revved’. They had lodged the back axle of the car on two

bricks with the back wheels just off the ground. Another time

they stuffed up the exhaust pipe with cotton wool!

One April, on April Fools Day, I found amongst the post, which I

usually opened, a typewritten envelope, stamped and franked,

addressed to me. This was not at all unusual, as some

customers invariably sent mail directed to me. Unfortunately

for the girls, however, I spotted that this particular envelope had

a cypher out of alignment, just as our office typewriter had!

Writing on the outside: “Not known at this address. Try

schoolgirl seminary,” I entrusted it to the Governor to take it to

the house when he went up for breakfast. I learnt afterwards

from Mrs. Mead that he took delight in taking it to them.

“You’ll have to get up earlier in the morning to catch Chikko!” he

told them.

A fall of snow always spelt danger if I crossed the mill yard.

One day I caught Vera, the younger daughter, unawares, and got in a

lovely shot with a snowball. Her father, who had seen it,

laughed his head off, but Vera was so annoyed at being caught

napping that she hit him with one full-faced.

The next day, however, the girls had the laugh on me. Opposite

the office was a flat-roofed part of the warehouse to which one door

from the main mill building gave access. Noticing them coming

down the yard I nipped out there and from my vantage point lobbed

snowballs at them, scoring two direct hits before they realised from

where the snowballs were coming. They quickly took cover out

of sight and I waited for them to reappear, but the next thing I

heard was the bolt of the access door being pushed home! There

I was, marooned on the flat roof in the snow! Then from a safe

distance they barracked: “Shall we let your mother know you’ll be

late home?”

RECOLLECTIONS OF BILL MEAD

The Governor kept pigs in the mill yard and also a boar, and a

charge of five shillings was made to local pig keepers if their sow

was serviced by this boar. This money was the Governor’s perks

and was usually placed on one particular spot on the office desk.

Sometimes there would be ten or fifteen shillings lying there for

days before he took it.

Coming back from the bank one day, the man responsible for the

accounts, etc., threw down two halves of a dud half-crown, demanding

two shillings and sixpence in lieu. Naturally he chose me, as

being the junior of the three of us in the office, but I refused to

accept that I had taken it from a customer. It could have been

he himself, or the flour traveller. The next day he spotted

another dud, when the flour traveller paid in his cash. I had

a brainwave. “Slip it in among the Governor’s pile” I

suggested. “He shouldn’t have left his money lying about!”

Two days later yet another dud received the same exchange operation.

That same night the Governor came into the office and, pocketing the

pile of money on the desk, remarked “They tell me there’s some dud

half-crowns about. “ He was no fool and probably had a very

good idea what we had done, but we heard no more about it!

At hay time and harvest customers had to take second place to the

needs of the farm. On one occasion the mill was stopped at

midday, and every man and every available vehicle was commandeered

for ‘carting’. On another such occasion I came up against it.

A local farm tenancy had just changed and on my rounds I obtained a

good order from the new man, but the goods had to be delivered,

without fail, on the Wednesday. The customer was also a

butcher, whose shop was closed on Wednesdays, so that was the only

day he could be at the farm to accept the goods.

I got back from market on that day, only to find that four of the

lorry men were down at the farm, leaving only one lorry without a

driver in the yard, and the order for Buckland had not been

delivered. I was furious. The Governor himself was just

off to the farm when I accosted him. “I promised that man his

stuff today and he’ll have it, even if I have to take it myself,

single-handed!” I stormed off and was in the driving seat of

the remaining lorry like a jack rabbit. I backed it against

the loading bay and went into the warehouse to find a man to truck

the stuff to the bay for me to load.

There was a dispersal sale at Aston Clinton of the effects of the

late Lady Bathurst, a member of the Rothschild family, and the

Governor went along. He bought some beautifully carved glazed

mahogany doors from a summerhouse and had them installed as French

doors in the drawing room of the Mill House, where, as far as I know

they remain. He also bought, complete, a very large,

ornamental fountain. It had a central column of water rising

some ten feet into the air, which fell into the large surrounding

basin. Around the inner circumference of this basin were eight

stone frogs, all of which also spouted water into the basin.

The whole thing amounted to a miniature bathing pool. This the

Governor had installed in his garden and when it was up and running,

he held a garden party to ‘christen the new fountain’. It was

a very warm July day, and with the office windows all open we could

hear the talk and much laughter.

Now it so happened that the Governor let the farmhouse where farmed

in Marsworth. He and the most recent tenant had ‘had a few

words’ over a few points in the tenancy about which they couldn’t

agree, and the Governor was very annoyed about it. This tenant

was a guest at the party, and we in the office had a fair idea that

something would happen. Sure enough, all at once we heard a

shriek and a yell. The Governor had ‘accidentally’ stumbled

against his dissatisfied tenant and had pitched him head-first into

the fountain! Of course the Governor, with his tongue in his

cheek, was full of apologies. He sent the man into the house,

found him a suit of his own clothes, which fitted, and even gave him

a bottle of champagne to take home — but he had got his own back

about the difficulty with the tenancy! I should add that many

years later, after the death of the Meads, when I was living in the

Mill House both my daughters learnt to swim in this fountain!

Shortly after the fountain was installed, the old premises of the

Mark Lane Corn Exchange were replaced and a sale of effects from the

old building was held. Among the items put up for sale was the

lovely coat of arms from the top of the old building, which the

Governor bought amidst much chaff and leg pulling from his pals on

the market, who said he must be crackers to buy such a thing.

It was a massive piece of stone, weighing at least a ton, on which

was sculpted a coat of arms comprising an English rose, a Scotch

thistle and a Welsh leek with sheaves of corn, on each side of which

was a lion and a unicorn. The Governor, of course, had to

arrange his own transport for his purchase, so at about 2 a.m. one

morning he set off with two or three of the men in the firm’s Napier

lorry, into which they had loaded some Morris lifting gear.

The loading safely accomplished, they made for home, having put a

tarpaulin over the coat of arms. Unfortunately, however, they

hadn’t covered it properly and they were stopped twice by wide-awake

policemen who thought that the statue of Eros, or something similar

was being pinched! They eventually got it home and it was

installed behind the fountain to form an effective backdrop, and

there it remained for many years. It was lucky to do so,

because when the new Corn Exchange building was nearing completion a

search was made for the coat of arms to be placed on the top.

It should never have been sold!

Unfortunately, the man who was deputed to approach the Governor to

try to recover it was one of those who had ragged him unmercifully

over the purchase, and his answer was: “No. If I was crackers

enough to buy the thing, I’m crackers enough to keep it!” And

he did! When enlargement of the mill premises became necessary

some years ago, some of the mill garden was taken away, and the coat

of arms had to be moved. It now stands at the road frontage at

New Mill for all to see.

At the Mill House, in addition to his flower garden, the Governor

had a large walled garden and a range of greenhouses for which he

employed three gardeners. One of the greenhouses was used for grapes

which, when harvested, were luscious. He was always very

generous and if one of his employees or a friend was ill, they would

receive a gift of grapes if in season, or of flowers.

The entrance lobby and the hall of the Mill House were always filled

with a lovely display of pot plants, and cut flowers were always in

the lounge. On the occasion of the Bucks Farmer’s Ball, held

annually at the Aylesbury Town Hall, he provided all the pot plants

etc., for decoration. On the afternoon of the ball he would

appropriate one of the mill lorries − often disrupting deliveries of

flour or feeding stuffs − and together with his gardeners would go

to the hall to arrange the display. Then the following morning

the lorry was sent to bring them back.

When dressed for a visit to Mark Lane, or any special occasion, the

Governor always sported a colourful buttonhole. Visitors to

the mill or house would invariably receive a present of a pot plant,

cut flowers or grapes. On the other hand he was intolerant of

anyone who blatantly cadged things. One of his specialities

was sweet peas, which he grew from Dobbies. One man, who was

noted for his parsimony despite being quite wealthy, enthused to the

Governor about the blooms. “When you order your seed, William,

I would be delighted if you would order some for me,” he said,

obviously with no thought of payment. In the spring, he duly

received an envelope containing ‘Pea seed, with the Complements of

Bill Mead’. His gardener, a most gentle man, for whom I felt

sorry, tended them with great care. Alas, when the outcome was

small mauve flowers, the product of wild hedgerow peas, or ‘tares.’

Naturally, the news leaked out and the general comment was: “Serve

the mean old devil right!” I should add that the Governor sent

a bottle of Scotch to the unfortunate gardener.

The Governor went down to the Marsworth farm one morning, getting a

lift with our traveller, who was going by, and it was arranged that

a lad from the garden was to go, with the pony cart, to fetch him

back later. However, things went wrong and Proctor, the lad

who should have fetched him back, had not gone down as instructed.

When the phone rang, I answered it. “Who’s that?” snapped the

Governor. “Seymour,” I identified myself. “You seen

young George Proctor?” he asked. “Yes,” I said, “He was over