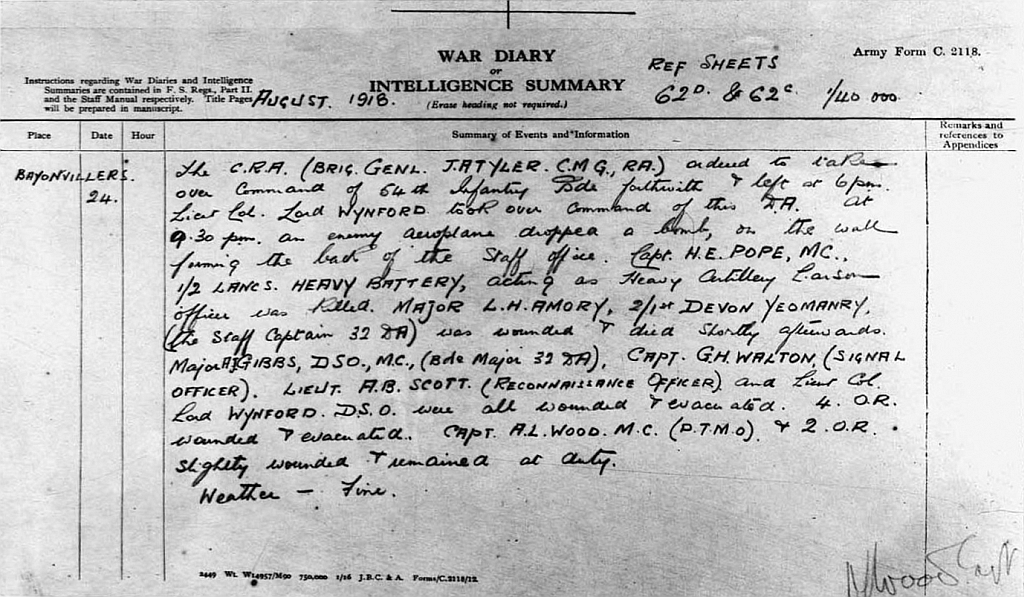

|

|

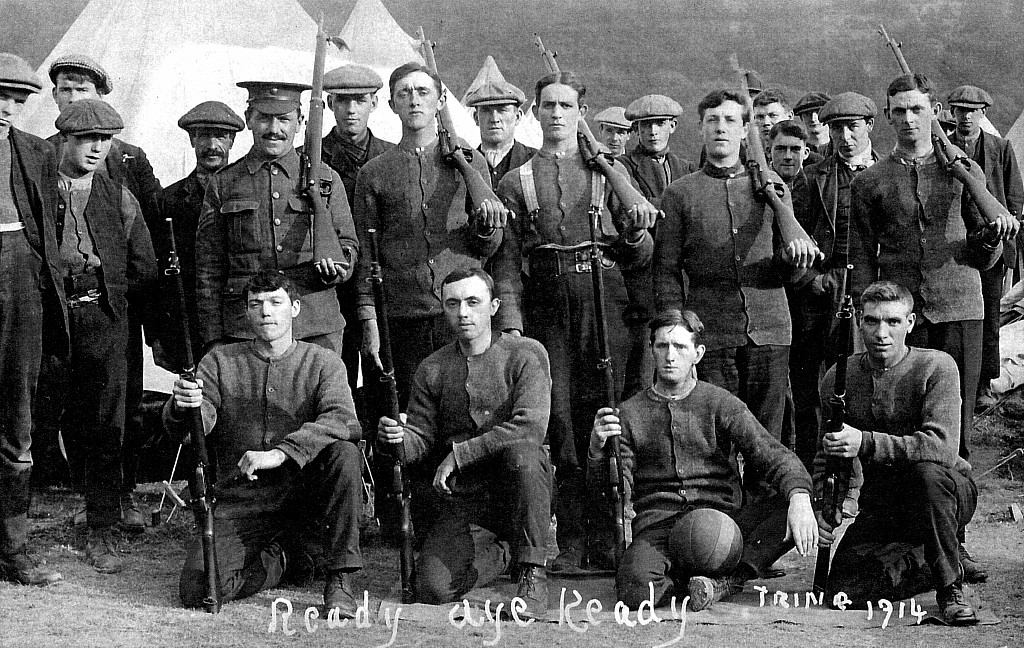

HAYWARD TO PRATT

WALTER HAYWARD

Private, 6th Australian Machine Gun Company, service number 462.

Born at St Leonards, Bucks. Son of Sarah and the late Charles

Hayward of 3 Henry Street, Tring.

Killed in action on the 4th May 1917 aged 22.

No known grave. Commemorated on the Villers-Bretonneux

Memorial, France.

Panel number, Roll of Honour, Australian War Memorial, 118.

Few personal details about Walter Hayward survive. He was born at St.

Leonards, Bucks., and was a Baptist by religion. At some stage

in his life he emigrated to Australia where he later enlisted in the

Australian Expeditionary Force (AIF) and returned with them,

briefly, to

England.

To transport the AIF to their various destinations, a fleet of transport ships was

leased by the Australian government. His Majesty’s Australian

Transport Ship (HMAT) A38, on which Private Haward sailed,

was owned by the China Mutual Steam Navigation Company of London and

in peacetime traded under the name Ulysses.

On the 25th

October 1916 Private Hayward’s unit embarked at Melbourne

(Victoria). The embarkation list shows his civilian occupation as labourer

and his address as c/o D.

McLennan, Mumbannar, via Heywood, Victoria.

Australian troops embarking on the Ulysses.

The Ulysses departed that day for Durban, South Africa, which

she reached on the 13th November; Cape Town on the 19th November;

Freetown, Sierra Leone, on the 14th December; and Plymouth on the

28th December. On landing at Plymouth the unit entrained for Tidworth, which they reached later that day.

HMAT A38, Ulysses.

Five infantry divisions

[Note] of the AIF saw action in France and Belgium. Commencing in April 1916,

for the next two and a half years they participated in most of the

major battles on the Western Front, [Note] earning a formidable reputation.

The 6th Australian Machine Gun Company, to which Private

Hayward was attached, was formed in February 1916 as part of the

6th Australian Brigade. This consisted of four infantry

battalions — the 21st, 22nd, 23rd and 24th Battalion — all of which

were raised in Victoria. After being sent to Egypt in June

1915 with the 2nd Division, the

brigade then went to Gallipoli in September. However, as the

last Allied offensive had come to an end the previous month, from

then until December 1915 when the Anzacs were evacuated from the

peninsula, the brigade was not involved in any significant

engagements.

In 1916, the

6th Australian Brigade was transferred to the Western Front, [Note] where it

took part in trench fighting for the remainder of the war.

During this time it was involved in a number of major battles

including the Battle of Pozières (23rd July–3rd September 1916), the Battle of Mouquet Farm

(23rd July–3rd September 1916) – the latter two being Somme

actions – and

the Battles of Bullecourt (April and May 1917). It was also involved in beating back

the tide of the German Spring Offensive (21st March–18th

July 1918) [Note] before taking part

in the final campaign of the war, the Hundred Days

Offensive (8th August–11th November). [Note]

Above: 2nd Australian Division machine

gunners near Pozières, 1916.

Below: Members of an Australian Machine Gun

Company, 1917.

Judging by the date of Private Hayward’s death and the location of

his unit at that time, it seems likely that he was killed during the

fighting for control of Bullecourt, one of several heavily fortified

villages in northern France that in 1917 had been incorporated into

the defences of the Hindenburg Line. [Note]

Two battles for Bullecourt were fought. The first attack was

launched on the 11th April 1917 by the 4th Australian and 62nd

British Divisions. The attack was hastily planned and mounted,

and was a disaster. The two brigades of the 4th

Australian Division that carried out the attack (the 4th and 12th)

suffered over 3,300 casualties while 1,170 Australians were taken

prisoner, the largest number captured in a single engagement during

the war.

A further attack was mounted on the 3rd May by the Australian 2nd

Division (5th and 6th Brigades) and the British 62nd

Division. The Australians succeeded in penetrating the German

line, but met determined opposition. Renewed efforts on the

7th May succeeded in linking British and Australian forces.

The Germans then mounted a series of ferocious and costly

counter-attacks, which eventually failed, and on the 15th May they

withdrew from the remnants of the village.

Although the locality was of little or no strategic importance, the

actions were nevertheless extremely costly to the AIF, their

casualties totalling 7,482 from three Australian Divisions.

The Villers-Bretonneux Memorial is the Australian National Memorial

erected to commemorate all Australian soldiers who fought in France

and Belgium during the First World War, to their dead, and

especially to name those of the dead whose graves are not known.

The Australian servicemen named in this register died in the

battlefields of the Somme, Arras, the German advance of 1918 and the

Advance to Victory. The memorial stands within Villers-Bretonneux

Military Cemetery, which was made after the Armistice when graves

were brought in from other burial grounds in the area and from the

battlefields.

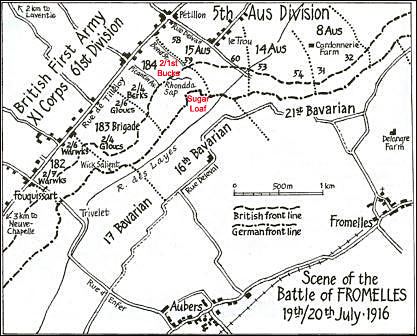

Of the 10,982 names displayed at the unveiling of the

Villers-Bretonneux Memorial the burial places of many have since

been identified and this continues to this day; 6 of these being

among the significant discovery of 250 burials which culminated in

the first new Commission cemetery in 50 years being dedicated in

July 2010 as Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Cemetery. All these

discoveries are now commemorated by individual headstones in the

cemeteries where their remains lie and their details recorded in the

relevant cemetery registers; their names will be removed from this

memorial in due course.

――――♦――――

HERBERT HAZZARD

Private, 1st Oxfordshire and Bucks Light Infantry, service no. 3027.

Son of Selina Hazzard of 1 Miswell Lane, Tring.

Enlisted at Aylesbury. Killed in action on the 1st April 1916

aged 21.

Buried in Hebuterne Military Cemetery, France, grave ref. I. A. 17.

On the 30th March 1915, the 1st Battalion (Territorial Force) Ox and

Bucks Light Infantry mobilised for war and landed at Boulogne.

In May the formation became the 145th Brigade of the 48th (South

Midland) Division. They spent the greater part of this period

in trenches at Hébuterne − a village 15 kilometres north of Albert

(Somme) and 20 kilometres south-west of Arras − losing a few

officers and men and having a somewhat arduous time, but without

being seriously engaged with the enemy.

A Relieved Platoon of 1/5th Battalion,

Gloucestershire Regiment, at Hébuterne, France, c.1916.

Courtesy of the Cheltenham Trust and Cheltenham Borough Council.

Towards the middle of January 1916 the Battalion moved to take over

other trenches. These lay more to the S.E. of Hébuterne in

very much lower ground than their previous sector, and they found

them in a serious state of decay and rapidly falling in everywhere.

The result was that every man had to do his utmost with the spade to

bring about substantial improvement, and it was not long before a

marked change was achieved. However, efforts to keep open the

communication trenches were very difficult, for even in good weather

the results achieved were in not proportionate to the amount of

effort expended. Furthermore, the enemy artillery became ever

more active and their shooting was exceptionally good. This

accounted for a number of casualties.

During this period the enemy undertook several raids, but without

managing to enter the battalion’s trenches. These raids were

preceded by heavy bombardments, in which the trenches suffered

considerably, the more so when minenwerfers [Note]

were employed in large numbers, as their shells made the most

gigantic craters that completely obliterated all traces of dugouts

and trench. At the beginning of April 1916 the battalion was

relieved and took over trenches that, while in better condition,

were by no means good.

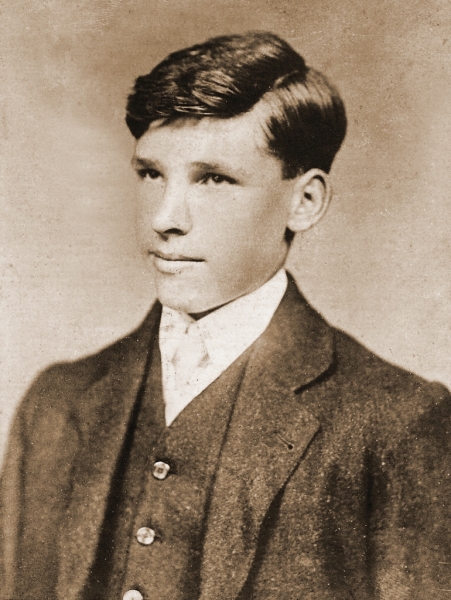

Herbert Hazzard (1895-1916)

As the weather began to improve, patrols were sent out more

frequently and brisk fighting in “No Man’s Land” resulted.

This from the regimental history:

“On Sunday 26th March 1916, the Battalion

moves in to ‘J’ section trenches at Hébuterne. On the night of

1st April a patrol of Bucks men encountered an enemy patrol of some

fifty soldiers in no mans land. In the ensuing skirmish L/CPL Colbrook , Privates Hazzard and Webb were killed. The bodies

of Webb and Hazzard lay for sometime between the enemy and our

positions. When darkness fell, L/CPL Jennings and six men

recovered the bodies but alas, Private Coleman was killed. Our

patrol was led by Captains Combs and Aitkin who remarked that the

men killed were regularly used for such patrols, because of their

expertise and bravery on such operations.

All of the soldiers mentioned in the Regimental Report, lie buried

next to each other in the cemetery which is situated on the edge of

the village next to a farm.”

During the war, 5,878 officers and men of the Oxfordshire and

Buckinghamshire Light Infantry lost

their lives. This from the Bucks Herald:

“The Great War. Another Tring Man

Killed in Action. − Tring’s Roll of Honour grows apace. Private

Herbert Hazzard, of Chapel Street, Tring, enlisted in the 1st Bucks

Territorials in November 1914, and has been in France twelve months.

Before joining the army Herbert Hazzard was working for Messrs

Honour and Son as a machinist. Last Thursday evening his

parents received intimation that their son had fallen in action.

Private Hazzard was well known in the town, where he was much liked,

being a young man of steady character and amiable disposition.

The circumstances attending his death are related in the following

letter to his father from the commanding officer of Private

Hazzard’s company.

‘2nd April 1916.

Dear Sir,− It is with very great regret and sorrow that I have to

write to you to acquaint you with the fact that your son, Private H.

Hazzard, of my company was killed in action last night. He was

out on patrol with a number of his comrades and two officers.

Our patrol met a large number of the enemy outnumbering us by more

than two to one. A fight ensued in which your son threw his

bombs with great effect. I am grieved to say that he was

killed instantly, by being struck on his head with a piece of bomb.

Your son was one of the best fellows in the world, and was

absolutely fearless, and always cheery. It was not the first

time by any means that your son had distinguished himself on patrol.

He received special commendation from the General commanding the

Division for his work during a patrol fight about a month ago.

Please accept my most sincere sympathy and the sympathy of all his

comrades, both officers and men, in your sad loss. I have lost

one of my best men in your son and I feel his loss most keenly.

Yours truly

L. W. Crouch, Captain.’” [Note]

Herbert Hazzard was born in Tring.

In the 1911 Census, he is recorded living with his parents Fred

(aged 53, a bricklayers’ labourer) and Selina at 18 Chapel Street,

Tring. His occupation is given

as “working in machine shop.”

Herbert Hazzard is buried at the Hébuterne Military Cemetery.

The village of

Hébuterne gave its name to a severe action fought by the French on

the 10th-13th June 1915, in the “Second Battle of Artois”. It

was taken over by British troops from the French in the same summer,

and it remained subject to shell fire during the Battles of the

Somme. It was again the scene of fighting in March 1918, when

the New Zealand Division held up the advancing enemy, and during the

following summer it was partly in German hands.

There are now over 750, 1914-18 war casualties commemorated in this

site. Of these, nearly 50 are unidentified and special memorials are

erected to 17 soldiers from the United Kingdom, known or believed to

be buried among them.

――――♦――――

JOHN RUSSELL HEDGES

Private, 1st/5th Battalion Bedfordshire Regiment, service no.

201230.

Son of Elizabeth Hedges of 7 Parsonage Place, Tring.

Died of pneumonia (possibly of malaria [Note]) in the Lebanon on the 16th

November 1918 aged 26.

Buried in Beirut War Cemetery, Lebanon, grave ref. 312.

The long-established Bedfordshire Regiment was greatly expanded

during the First World War, elements of which were engaged on both

the Western Front [Note] and in the Middle East.

In January 1915, the 1st/5th Battalion was re-designated as part of the

162nd

(East Midland) Brigade in the 54th (East Anglian) Division. On

the 26th July the battalion set sail for Egypt. After a brief

stop-over they reached Gallipoli where the battalion served between

the 10th August and 4th December. In December, the pitifully

small number that remained were moved back to Egypt where, between

January and March 1916, the battalion were rebuilt. They then

undertook a year-long posting as guards to the Suez Canal.

|

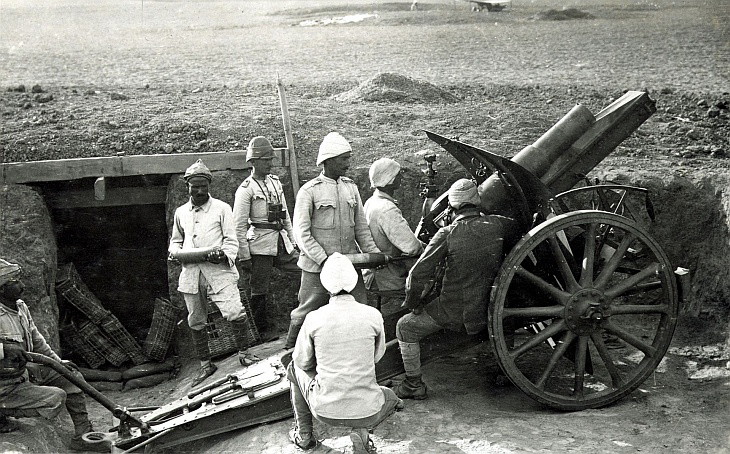

A Turkish machine gun

company during the 2nd Battle of Gaza (17th-19th April

1917). The 54th (East Anglian) Division took part in

this British defeat in which at 6,444 men, the British

casualty figure was three times that of the Turks. |

In March 1917, the battalion advanced to Gaza with the British and

Commonwealth forces where they took part in all of the actions both

there and in those that followed during the advance through

Palestine. [Note] By the time of the Armistice they were stationed at

Beirut, having spent the entire campaign in that theatre of war.

Soldiers in this theatre of war suffered considerably from diseases,

with the battalion losing considerably more men to that cause than

to enemy fire. This from the War Diary [Note] for

the 31st October 1918:

“Beirut 0746 Battn. moved with Bde. Group through BEIRUT. Bde.

halted outside town & prepared for a Ceremonial march through.

1030 Bde. Group less wheeled & camel transport marched through

BEIRUT. When in the SQUARE Corps Commander with other General

officers British & French took the salute. Troops were

received by populace with enthusiasm. Bde. bivouaced one mile E

of town. Troops allowed into town until 1900. Official

Wire received Re. Armistice between TURKEY and the ALLIES.

During the month an epidemic of fever has been experienced malarial

cases being numerous.”

During November alone the War Diary records 10

deaths from malaria. Although the Diary attributes

Private Hedges’ death to pneumonia, there can be striking clinical

similarities between it and malaria, which − presumably based on

correspondence received by Mrs. Hedges from the Regiment − is the

cause of death reported in the Bucks Herald.

From the

Regimental War Diary for November 1918:

16 Nov 1918 Physical training 0800-0830.

Working parties engaged on stables. A & B Coys amalgamated to

form Y Coy. C & D coys to form Z Coy. Half holiday in

afternoon.

[Private 201230 J. R. HEDGES died of

Pneumonia at 1/2nd East Anglian Field Ambulance, Beirut].

17 Nov 1918 Bde. Church Parade 0900. Pte. Hedges buried

at MAR TATLAR at 1300 with Military Honours.

From the Bucks Herald, 14th November 1918:

“ROLL OF HONOUR.

− News has been received of the death of . . . . Pte. John Russell

Hedges, son of Mrs. Robert hedges, Parsonage Place, is reported to

have died of Malaria in Egypt on Nov. 16, at the age of 25 years.”

From the Tring Parish Magazine:

“News has been received of the death,

through pneumonia of John Russell Hedges, in a field ambulance in

Palestine, on November 16th 1918. He joined up in January 1915

and was attached to the Bedfordshire regiment. After a years

training in England, he went to Egypt, and served all through the

campaign in Palestine. His Chaplain, writing to his mother,

says: ‘we laid your son to rest at Martatlar near Essafa, on a

gentle slope overlooking the sea and his funeral (with Military

Honours) was a most impressing one.

His death made a great impression among his fellows. He was

liked very much for his quiet and gentle manners. The times

have been strenuous of late, and he was a hard and uncomplaining

worker, and we are glad we can keep the memory of your son’s

devotion, and the inspiration of his sacrifice.’”

Beirut War Cemetery

Lebanon was taken from the Turks in 1918 by Commonwealth forces with

small French and Arab detachments. Beirut was occupied by the

7th (Meerut) Division on 8 October 1918 when French warships were

already in the harbour, and the 32nd and 15th Combined Clearing

Hospitals were sent to the town. There are 628 First World War

Commonwealth burials and commemorations at the cemetery.

――――♦――――

SIDNEY WALTER HEDGES

Lance Corporal, 6th Northamptonshire Regiment. Enlisted at

Watford, service no. 28398.

Born in Tring. Son of the late Thomas, and of Susanna

Elizabeth Hedges of 55 Western Road.

Died of wounds on the 16th April 1918 aged 21.

Buried in Rosieres Communal Cemetery Extension, France, grave ref. II.A.9.

The Northamptonshire Regiment was a British line infantry regiment

that existed from 1881 until 1960. In the years

that followed, amalgamations with other regiments took place in

which it was absorbed

into the present Royal Anglian Regiment.

6th (Service) Battalion, [Note]

Northamptonshire Regiment was raised at Northampton in August 1914

as part of Kitchener’s Second New Army [Note]

and joined 18th (Eastern) Division as army troops. They

moved to Colchester for training and in November (transferring to

the 54th Brigade in the same Division) before moving to

Salisbury Plain in May 1915 for final training. On the 26th

July 1915 it landed in France where the division concentrated near Flesselles. |

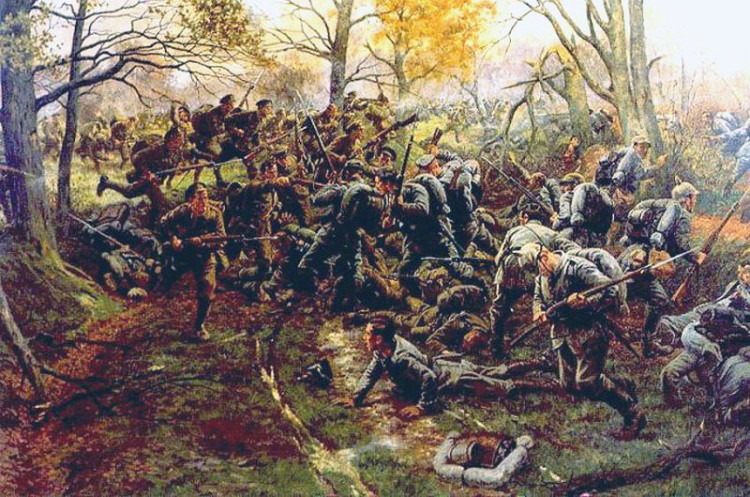

Artist’s impression of savage hand-to-hand fighting

in Delville Wood.

|

In 1916 the battalion was in action on the Somme in the Battle of Albert

capturing their objectives near Montauban, the Battle of Bazentin

Ridge including the capture of Trônes

Wood, the Battle of Delville Wood, the Battle ofThiepval Ridge, the

Battle of the Ancre Heights playing a part in the capture of the

Schwaben Redoubt and Regina Trench and the Battle of the Ancre.

In 1917 they took pait in the Operations on the Ancre including

Miraumont and the capture of Irles, the fought during The German

retreat to the Hindenburg Line [Note] and in the Third Battle of the Scarpe

before moving to Flanders. They were in action in the Battle of Pilkem Ridge,

the Battle of Langemarck and the First and Second

Battles of Passchendaele.

In 1918 they saw action during the Battle of St Quentin, the Battle

of the Avre, the actions of Villers-Brettoneux, the Battle of Amiens

and the Battle of Albert where the Division captured the Tara and Usna hills near La Boisselle and once again captured Trônes

Wood. They fought in the Second Battle of Bapaume, [Note] the Battle of Epehy,

the Battle of the St Quentin Canal, the Battle ofthe Selle

and the Battle of the Sambre. At the Armistice the battalion was in

XIII Corps Reserve near Le Cateau and demobilisation began on the

10th of December 1918.

British troops captured during the

Spring Offensive, March 1918.

During the early stage of the 1918 German Spring Offensive, [Note]

the 6th battalion formed part of the 5th Army (Lieut. General

Gough), but following the Battle of St Quentin (21st–23rd March)

it was moved to the 4th Army (General Sir Henry Rawlinson)

with which it was engaged in the Battle of the Avre (4th-5th April).

Private hedges is reported to have been killed during the Spring

Offensive (see Parish Magazine obit below), but as the date

on which he was wounded is unknown, it is unclear in which action he

was involved at the time. It might have been in either of the

two actions referred to, although he may have been wounded and

captured on some other occasion between the start of the Offensive

(21st March) and his date of his death (16th April).

From the Tring Parish Magazine:

“Sidney Walter Hedges, L/CPL, 6th Northants

Regt joined the army in October 1916 and went to Halton Camp for

three months training. He then immediately proceeded to France

where he remained until his death. He was, apparently,

severely wounded during the German offensive of the spring and was

taken prisoner by the enemy. He died in a German Field Reserve

Hospital on April 16th and was buried in a cemetery reserved for

prisoners.

He leaves behind him a pleasant memory in Tring, and has died, as we

are sure he would have wished to die. gallantly, doing his duty to

his king and country.”

Rosieres Communal Cemetery Extension

Rosieres was the scene of heavy fighting between the French Sixth

Army and the German First Army at the end of August, 1914. It

came within the British lines in February 1917. With the

advance to the Hindenburg Line in the spring of 1917, Rosieres

became part of the back area; but in the German Offensive of 1918 it

was reached by the enemy on the 26th March. In the Battle of

Rosieres on the 27th it was defended by the 8th Division and

the 16th Brigade, Royal Horse Artillery, [Note] but these troops had to be

withdrawn during the night. After a stubborn defence the

village was retaken by the 2nd Canadian Division with Tanks on the

9th August. There are now over 400, 1914-18 war casualties

commemorated in this site of which over one-third are unidentified.

――――♦――――

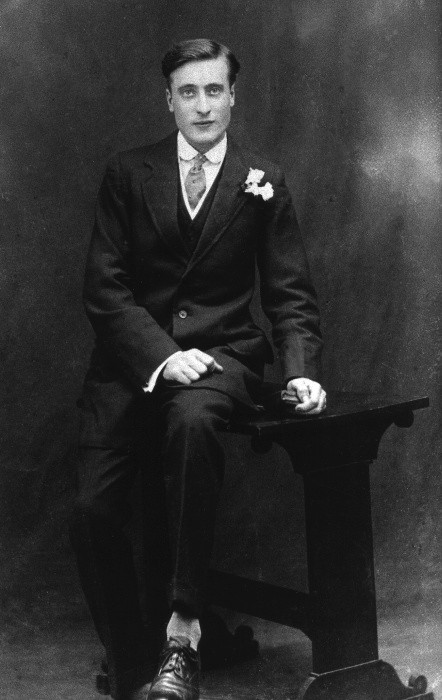

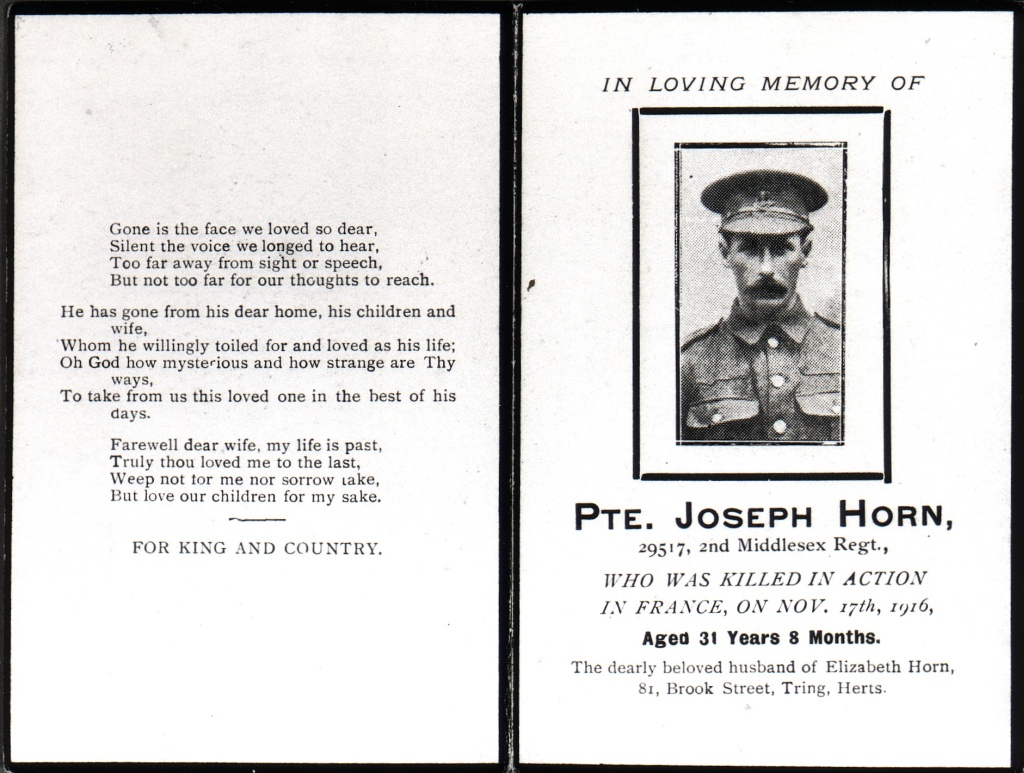

JOSEPH HORN

Private, 2nd Middlesex Regiment, service no. 29517.

Born in Tring. Husband of Elizabeth Horn of 81 Brook Street,

Tring.

Enlisted at Bedford on the 30th May; killed in action on the 17th

November 1916, aged 31.

Buried in Guillemont Road Cemetery, Guillemont, France, grave ref.

I. F. 2.

The Middlesex Regiment (Duke of Cambridge’s Own) was a line infantry

regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 until 1966.

It was formed on the 1st July 1881 with two regular, two militia and

four volunteer battalions.

On the 4th August 1914, the 2nd Battalion, which had been stationed

at Malta, returned to England. It then landed at Le Havre in

November as part of the 23rd Brigade,

8th Division, [Note] to provide badly-needed reinforcement to the B.E.F. [Note].

The 8th Division had been formed at the outbreak of war by combining

battalions returning from outposts in the British Empire,

Major-General Francis Davies taking command. The division

moved to France in November, following the First Battle of Ypres, and

fought on the Western Front [Note] for the remainder of the war.

During this time the 2nd Battalion Middlesex Regiment was engaged in

the following actions:

1915; The Battle of Neuve Chapelle, The Battle of Aubers, The action

of Bois Grenier;

1916; The Battle of Albert (the first phase of the Battles of the

Somme 1916), operations near Le Transloy;

1917; The German retreat to the Hindenburg Line, [Note] Third Battles of

Ypres (The Battle of Pilkem and The Battle of Langemarck, The Battle

of the Menin Road);

1918; The Battle of St Quentin, The actions at the Somme crossings,

The Battle of Rosieres, The actions at Villers-Bretonnex, The Battle

of the Aisne, The Battle of the Scarpe and the Final Advance in

Artois including the capture of Douai. They ended war (11th

November) at Douvrain in Belgium, N.W. of Mons.

During the Somme Offensive, the 2nd Middlesex Regiment served with

the 23rd Brigade, 8th Division. The battalion

had arrived on the Somme front in 1915 and spent many months there in

the lead up to the battle. On 1st July 1916 they took part in

the attack at Mash Valley near Ovillers (during The Battle of

Albert, 1st–13th July) suffering more than 650 casualties on that

day.

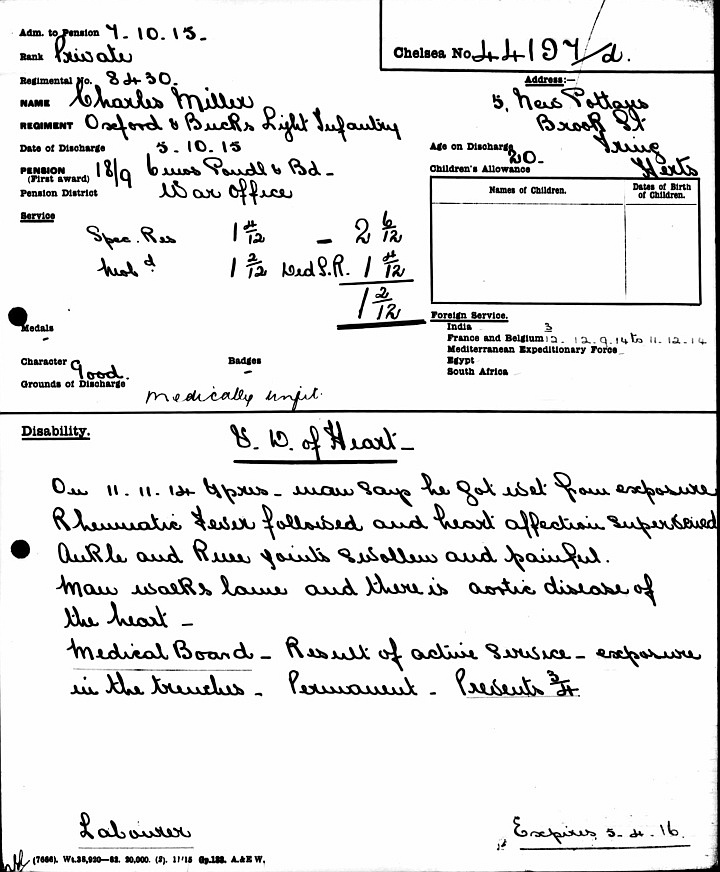

Moving a 60-pdr field gun into position

during the Battle of Le Transloy, October 1916.

This from the Parish Magazine:

“Joseph Horn was killed alongside five

others, by a shell which burst in his dug-out. He joined the

Army on 30th May 1916 and had been in France since September 1917.”

In October 1916, the battalion returned to the Somme and took part

in operations near Le Transloy, losing more than 230 casualties in

bitter hand to hand fighting at Zenith Trench. This action,

which was the 4th Army’s last offensive in the Battle of the Somme,

ended in the middle of October after which the 2nd Battalion appears

not to have

played a part in any significant actions for the remainder of 1916.

Thus it seems reasonable to assume that Private Horn was killed during intermittent

periods of artillery fire. |

Joseph married Elizabeth Hart (aged 24) of 37 Akeman Street,

daughter of Frederick Hart (labourer), on the 7th January 1909.

Joseph (aged 23), the son of James Horn, a boot-maker, who was then

living at 80 Brook Street, gave his profession as “carman”

(this being a driver of horse-drawn vehicles for transporting

goods).

Guillemont was an important point in the German defences at the

beginning of the Battle of the Somme in July 1916. It was

taken by the 2nd Royal Scots Fusiliers on the 30th July but the

battalion was obliged to fall back, and it was again entered for a

short time by the 55th (West Lancashire) Division on the 8th August.

On the 18th August, the village was reached by the 2nd Division, and

on the 3rd September (in the Battle of Guillemont) it was captured

and cleared by the 20th (Light) and part of the 16th (Irish)

Divisions. It was lost in March 1918 during the German

advance, but retaken on the 29th August by the 18th and 38th (Welsh)

Divisions.

The cemetery was begun by fighting units (mainly of the Guards

Division) and field ambulances after the Battle of Guillemont, and

was closed in March 1917, when it contained 121 burials. It

was greatly expanded after the Armistice when graves (almost all of

July-September 1916) were brought in from the battlefields

immediately surrounding the village and certain smaller cemeteries.

Guillemont Road Cemetery now contains 2,263 Commonwealth burials and

commemorations of the First World War, 1,523 of which are

unidentified, but there are special memorials to eight casualties

known or believed to be buried among them.

――――♦――――

CHARLES FREDERICK HOWLETT

Private, 8th Lincolnshire Regiment, service no. 41722.

Son of Frederick Charles and Emma of

Western Road, Tring.

Enlisted at Aylesbury, formerly with the RASC.

Killed in action on the 4th October 1917 aged 22.

No known grave. Commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial,

Belgium,

panel

35 to 37 and 162 to 162A.

The 8th Lincolnshire Regiment was established on the 15th September

1914 as part of K3. [Note] At the

outbreak of war all the battalion commanders had been in retirement

− of the 21st Division, to which the 8th Lincolns were attached,

only 14 officers had any previous experience in the Regular army.

The 8th Lincolns formed part of the 63rd Brigade,

21st Division in XI Corps. [Note]

The Battalion trained at Grimsby during August and at Halton Park

near Tring in November. During the winter of 1914 they moved

into billets at Leighton Buzzard, but in the following spring

returned to Halton Park Camp where they commenced rifle practice. |

Training at Halton Camp.

|

On the 10th September 1915 the battalion landed at Boulogne, its

compliment being 28 officers, 2 personnel, and 993 Other Ranks.

Having stayed in the Watten area for a week, the battalion set off

for the front and The Battle of Loos. In this, their first

action, lack of battlefield experience quickly showed resulting in

many unnecessary casualties − following the action 22 of their 24

officers and 471 other ranks were dead, wounded or missing.

The battalion was then taken out of the line and into billets to

receive replacements and for training, periods of work on trench

defences, periodical tours of the trenches and working parties.

July 1st 1916 marked the beginning of The Battle of the Somme.

The 8th Battalion attacked at Fricourt, their casualties being

Officers − 4 dead, 1 missing, 7 wounded; Other ranks - 30 dead, 12

missing, 197 wounded.

On the 8th July the battalion was transferred to the

110th

Brigade, 37th Division. Their next in action was in

the Battle of Ancre (13th-20th November) in which casualties were 3

officers and 172 other ranks.

During 1917 the battalion was in action during The German retreat to

the Hindenburg Line, [Note] The Arras

Offensive (The First & Second Battles of the Scarpe and The Battle

of Arleux), the The Third Battles of Ypres (The Battle of Pilkem

Ridge, The Battle of the Menin Road Ridge, The Battle of Polygon

Wood, The Battle of Broodseinde, The Battle of Poelcapelle, The

First Battle of Passchendaele) and The Cambrai Operations.

Judging by the date when Private Howlett was posted missing and the

8th Battalion’s involvement in fighting in October 1917, it appears

likely that he was killed in action during The Battle of Broodseinde.

This action was fought on the 4th October near Ypres in

Flanders. The attack aimed to complete the capture of the

Gheluvelt Plateau by the occupation of Broodseinde Ridge and

Gravenstafel Spur, the objective being to protect the southern flank

of the British line and permit attacks on Passchendaele Ridge to the

north-east. Using new ‘bite and hold’ tactics the capture of

the ridges was a great success, General Plumer (C-in-C 2nd Army)

calling the attack “. . . . the greatest victory since the Marne”

while the German Official History referred to “. . . . the black

day of October 4”. 2nd Army casualties for the week ending

the 4th October were 12,256.

Their War Diary records that on the 1st October the

Battalion was in the Front line (Battalion H.Q. at Het Papotje Farm)

and on the 4th October they attacked Jute Cotts, Bury

Cotts etc. Casualties were 8 officers, 181 other

ranks. The following extract from the Battalion History

describes the action in which, judging by the date on which Private Howlett

was posted missing and the 8th Battalion’s involvement in fighting

at that time, it seems likely that he fell:

THE HISTORY

of the

LINCOLNSHIRE REGIMENT

1914-1918

Compiled from War Diaries, Despatches,

Officers’ Notes and Other Sources

Edited by

MAJOR-GENERAL C. R. SIMPSON, C.B.

COLONEL OF THE REGIMENT

The Battle of Broodseinde: 4th October

“During the evening of the 3rd of October the fine weather broke: a

heavy gale and rain blew up from the south-west. Under such

adverse conditions arrangements were made for the next battle.

The attack took place at 6 a.m. on the 4th of October, and was

directed against the main line of the ridge east of Zonnebeke.

The front of the principal attack extended from the Menin road to

the Ypres-Staden railway — a distance of about seven miles.

Only a short advance, with the object of capturing certain strong

points was to take place south of the Menin road.

Two battalions of the Regiment — the 1st and 8th Lincolnshire — took

part in the Battle of Broodseinde, the former attacking the

enemy near the south-western corner of the Polygon Wood, the latter

south of the Menin road.

The 8th Lincolnshire was the left attacking battalion of the 63rd

Brigade (37th Division): the 8th Somerset was on its right.

The brigade had been but a short while in the line, having relieved

the 118th Brigade on the night of the 27th/28th of September.

The position taken over was supposed to be the line of a road

running north and south through Jute Cotts (a farmhouse south

of Tower Hamlets), but the actual line was found to be about one

hundred and fifty yards west of the road and in places even more.

And even this road had been obliterated by shell-fire. No

movement was possible during the day and reconnaissance was

extremely difficult. Even runners as soon as they left

Battalion Headquarters were sniped. However, after offensive

operations had been ordered, some sort of a reconnaissance was

carried out and the road was then found to be the German outpost

line, with strong points behind it.

The Somerset and Lincolnshire formed up under the greatest

difficulties, and at 6 a.m. attacked the enemy. But from the

time they left their assembly positions both battalions came under

murderous machine-gun fire.

The only comment made by the 8th Lincolnshire in their Battalion

Diary is ‘Attack unsuccessful,’ while the 63rd Brigade narrative has

the following: ‘On the left the 8th Lincolnshire advanced and, after

going about one hundred yards, came under fire of several

machine-guns which swept the slope. Two of these appeared to

be between the road and Joist Trench and another at Berry Cotts.

These guns inflicted very heavy casualties on the leading companies.

The enemy, about one hundred strong, were occupying the trench about

fifty yards east of the Jute Cotts road and were reinforced from

Joist Trench. The enemy also made local counter-attacks, but

it was entirely due to the machine-gun fire that the attack was held

up here. Owing to the whole plateau being swept by these

machine-guns and also by the machine-guns from the south, it was

decided that the attack could not get over the ground and, owing to

casualties, the original line was occupied.’

On the 5th the Lincolnshire advanced their posts north of Jute Cotts

to within fifty yards of the German line, and on this line they were

relieved on the 6th of October, returning to Little Kemmel.

The Brigade Diary gives one hundred and eighty-four as the total

casualties suffered during the operations: Captain R. G. Cordiner,

Lieutenant A. F. Forge and 2nd Lieutenants R. H. Westbury, W. R.

Gibson and F. H. J. Robilliard were killed and 2nd Lieutenants E. H.

Dukes and H. E. K. Neen wounded.”

This from the Parish Magazine:

“Charles Frederick Howlett, Lincolnshire Regiment who has been

missing since 4th October 1917, is now presumed killed on that date. He was engaged alongside his battalion in the fighting about Polygon

Wood. He was last seen by his Corporal, going over the top, and has

not been seen since. Also, there is nobody left who could tell what

happened to him subsequently.”

Charles, the eldest child (he had two sisters and seven brothers) of

Frederick and Emma Howlett, was born in Aylesbury in 1895. He

sang in the Tring Parish Church Choir for some nine years and was

confirmed as a chorister. In October 1915 he joined the Royal Army Service Corps in his trade as a baker.

In January 1917 he was transferred to the

Infantry and was sent to France in the following May, where he joined the 8th

(Service) [Note] Bn.

Lincolnshire Regiment.

The Tyne Cot Memorial is one of four memorials to the missing in

Belgian Flanders which cover the area known as the Ypres Salient.

Broadly speaking, the Salient stretched from Langemarck in the north

to the northern edge in Ploegsteert Wood in the south, but it varied

in area and shape throughout the war.

There was little more significant activity on this front until 1917,

when in the Third Battle of Ypres an offensive was mounted by

Commonwealth forces to divert German attention from a weakened

French front further south. The initial attempt in June to

dislodge the Germans from the Messines Ridge was a complete success,

but the main assault north-eastward, which began at the end of July,

quickly became a dogged struggle against determined opposition and

the rapidly deteriorating weather. The campaign finally came

to a close in November with the capture of Passchendaele.

The Tyne Cot Memorial now bears the names of almost 35,000 officers

and men whose graves are not known.

――――♦――――

HENRY JANES

Corporal 1st Royal Marine Light Infantry, service no. PO/17361.

Son of Job and Ruth Janes of 33 Kimberley Terrace, Wingrave Road,

New Mill.

Killed in action on the 17th February 1917 aged 23 years.

Buried at Queens Cemetery, Bucquay, France, grave ref II M 10.

|

|

|

Recruiting poster for the

Royal Naval Division, c.1914/1915. |

At the outbreak of the war the

Royal Naval Division was formed from Royal Navy

and Royal Marine reservists and volunteers − some 20-30,000 men − who were not needed for

service at sea. This was sufficient to form two Naval Brigades

and a Brigade of Marines for operations on land.

The Division fought at Antwerp in 1914 and at Gallipoli in 1915.

In 1916, following many losses among the original naval volunteers,

the Royal Naval Division was transferred to the British Army as the

63rd (Royal

Naval) Division, under which title it fought on the Western Front

[Note] for

the remainder of the war. During this time the 63rd took part,

during 1916, in the Battle of the Ancre

(13th–18th November); in 1917, in the Actions of Miraumont (17th–18th

February); Battle of Arras (9th April–16th May); Second Battle of

Passchendaele (26th October–10th November); Action of Welsh Ridge

(30th December); and, in 1918, in the Battle of St. Quentin (First Battle of Bapaume) (24th–25th March)

[Note]; Battle of Albert (21st–23rd August);

Hundred Days Offensive (8th August–11th November) [Note].

Judging from the date of Corporal Janes’s death (17th February 1917)

and the location of his unit at the time, it appears likely that he

was killed during The Actions of Miraumont (17th–18th

February, 1917).

The 63rd (Royal Naval) Division had two battalions of Royal Marine

Light Infantry, the 1st (1RMLI) and 2nd, both of which formed

part of the 188th Brigade. Due to the serious casualties it

suffered at the Battle of Ancre in November 1916, 1RMLI was

withdrawn from the front line to be rebuilt as a fighting unit.

Although the Battle of the Somme officially ended on the 18th

November 1916, the slaughter continued in the New Year as the higher

command demanded that the line be advanced. In early 1917, the

5th Army planned a series of attacks to improve its positions, the

first of which was carried out on the 17th February. The main attack

south of the Ancre [Note] was to be

carried out by the 99th Brigade (2nd Division) and 53rd and 54th

Brigades (18th Division). 6th Brigade (2nd Division) was to

attack in support on the right, while 63rd (Royal Naval) Division on

the left was to advance north of the Ancre. Success would give

the British command of the approaches to Pyrs and Miraumont, and

observation over the upper Ancre Valley. The attack was

officially named The Actions of Miraumont.

Royal Field Artillery [Note]

howitzer

emplacement at Miraumont-le-Grand, 1917.

The 63rd (Royal Naval) Division objective was to capture 700 yards

of the road north from Baillescourt Farm towards Puisieux, to gain

observation over Miraumont and to form a defensive flank on the left

back to the existing front line. On the evening of 16th

February, 1RMLI assembled for the attack, but based on

intelligence they had received, at 0500 the Germans brought down an

artillery barrage on the 1RMLI assembly area resulting in the

battalion suffering more than 50% casualties before their attack even

began. Despite this setback, the surviving Marines began their

advance at 0545 under the cover of a British artillery barrage under

the cover of a British artillery barrage. In the confusion of

battle and with the difficultly in navigating, the two left hand

companies veered towards the right, by pure chance avoiding intact

barbed wire. Thus, the sector they attacked had no wire at

all, and

by 1100 1RMLI had achieved their objectives. Their starting

strength was around 500; at the end of

the day’s fighting only 100 personnel were fit for duty, most of the

casualties having resulted from the initial German artillery

bombardment. Few men were killed in the assault itself in

which they encountered little opposition.

Corporal Janes was killed in action of the 17th February 1917.

This from his battalion’s War Diary for that period.

The Battalion was then in the RIVER TRENCH SECTOR, North of Grandcourt

(a commune in the Somme department in northern France):

“14.2.17: The 1st Royal Marines relieved the 10th Royal Dublin

Fusiliers in the RIVER TRENCH SECTOR, N of Grandcourt. B & D

Companies Hd. Qrs. in Pusieux Trench. Battalion Hd. Qrs. PUSIEUX

ROAD. Capt. Nouse to 2nd Field Ambulance (Influenza).

Casualties 2 killed - 1 offr (2nd Lt. Lee) and 9 Other Ranks

wounded.

15.2.17: Relief completed 3.0am. Casualties 6 killed - 3

missing - 9 wounded.

16.2.17: Battalion Hd. Qrs. moved forward to PUSIEUX TRENCH.

Battalion lined up for attack at 10.0pm. Objective SUNKEN ROAD

- L32C 91 to RCa26 including two strong points, that on the right

being known as the PIMPLE. Posts had to be established 50

yards beyond the Road.

Howe Battalion to attack on our right

- 2nd R.M. Battalion held ARTILLERY ALLEY and protected left flank.

ANSON Battalion held position R2d75 - R3c37 - R3c63. The

following officers were with the Battalion in the attack.

Lieut. Col. F. J. W Cartwright, D.S.O., Major H. Ozanne (wounded),

Major F. H. B. Wellesley, West Riding Regiment (wounded),

Captain E. J. Huskisson, Captain J. Pearson, Lieut. H. W. R. Hall,

Lieut A. C. Donne (wounded), Lieut. L. W. Robinson

(killed), 2nd Lieut. A. A. Okell (killed), 2nd Lieut. F.

Savage (killed), 2nd Lieut. E. Sanderson (wounded),

2nd Lieut. C. R. Burton (killed), 2nd Lieut. C. L. Rugg

(severely wounded), Lieut. E. G. Coulson (killed), 2nd

Lieut. W. C. Gudliston (wounded), Lieut. R. E. Champness,

Lieut. F. W. A. Perry (killed), 2nd Lieut. H. C. Brown

(killed), Surgeon Unthank R.N.

17.2.17: Advance commenced at 5.45am, on barrage

[Note]

opening. Our dispositions were, from right to left D, B, C, A

companies were extended at 2 paces interval, & in two waves at 20

paces distance. The lines were subjected to heavy bombardment by

77mm. at about 5.00am necessitating a call for retaliation by our

Artillery. [Note]

Reports received at 6.40am to effect that the Battalion had gained

their objective, and that the PIMPLE had been captured. 102

prisoners were taken, 1 77mm gun, & 2 machine guns were captured.

18.2.17: The enemy counter attacked on three

occasions. On one occasion taking advantage of thick mist, he

counter attacked, without artillery preparation, 2 battalions

strong, on 1½ mile frontage. S.O.S. message was sent, the

artillery replying with great promptitude, causing many casualties.

The battalion on the left turned and fled, and was almost

immediately followed by the right battalion. The line from

Battalion Hd. Qrs. to front line had only just been repaired when

S.O.S. was asked for.

Total casualties suffered by the Battalion in the attack, capture

and consolidation of the objective – SUNKEN ROAD. Officers – 7

killed, 6 wounded. Other ranks – 57 killed, 193 wounded, 27 missing.

19.2.17: 1st R. M. Battalion relieved in the line

during the night of the 18th/19th Feb. by 2nd R. M. Battalion.

Relief completed 7.0am. Companies moving independently to old

German 2nd and 3rd lines – Q18a30 – 1500 yards SSE of

BEAUMONT HAMEL. Major Ozanne to Field Ambulance.”

The Action of Miraumont forced the Germans to begin their withdrawal

from the Ancre valley before their planned Retreat to the

Hindenburg Line. [Note]

On the 24th February, reports arrived that the Germans had gone,

while further south their positions around Le Transloy were found

abandoned on the night of 12th/13th March. Allied troops

entered Bapaume [Note] on the 17th

March.

From the

Bucks Herald, 31st March 1917:

“THE ROLL

OF HONOUR. − The parish has to mourn

the loss of two more of her sons, who have laid down their lives for

their country’s cause ‘somewhere in France’ − Henry Janes, a

corporal in the Royal Marine Light Infantry, son of Mr. J. Janes, of

Wingrave-road, and Pte. Frank George Wilkins, son of Mr. Geo.

Wilkins, King-street.”

From the Parish Magazine, April 1917:

“Henry Janes must have done well to have

attained the rank of Corporal in such as body as the Royal Marines.

He served throughout the campaign in Gallipoli and came out

unscathed. However, he was killed in action on the 17th

February 1917, somewhere in France. May god accept what he has

given.”

Ruth Collyer married Job Janes in 1876 when she was 22 years old.

The 1901 Census records her and her family living at 1, The Grove,

Tring. Her husband, Job Janes (then aged 48) is recorded as a

domestic gardener. Their son Henry was born at Tring on the

27th February 1893. In 1901 the Census records him living with his parents,

brother (Robert, aged 14, a grocer’s assistant) and 3 sisters (Amy,

aged 12; Emily, aged 10; and Ethel May, aged 6). Also living

at the address was a grandson, Albert (born at Pitstone), then a

baby.

Ten year later the family was resident at 33 Wingrave Road. In

the Census of that year none of the girls are recorded at living that

address, but Robert (grocer’s assistant) and Henry (apprentice

whitesmith) continued to reside there with

their parents, and with grandson Albert (a scholar).

Queens Cemetery, Bucquay, France, was begun in March 1917, when 23

men of the 2nd Queen’s were buried in what is now Plot II, Row A.

Thirteen graves of April-August 1918 were added (Plot II, Row B) in

September 1918 by the 5th Division Burial Officer. The

remainder of the cemetery was made after the Armistice by the

concentration of British and French graves and one American from the

battlefields of the Ancre and from small cemeteries in the

neighbourhood. These included, at Puisieux, the River Trench

Cemetery (containing the graves of 117 officers and men) and the

Swan Trench Cemetery (containing the graves of 27 officers and men),

in both cases mostly of men of the Royal Naval Division who fell in

February 1917.

――――♦――――

FREDERICK

KEMPSTER

Rifleman, 7th Royal Irish Rifles, service no. 41863.

Born in Tring. Husband of Rose Kempster, 76 Akeman Street,

Tring.

Enlisted at Tring, formerly with the Essex Regiment.

Killed in action on the 2nd October 1917 aged 29.

Buried in Cojeul British Cemetery, St. Martin-sur-Cojeul, France,

grave ref. 1. F. 6.

The 7th (Service) [Note] Battalion

Royal Irish Rifles was formed at Belfast in September 1914 as part

of K2, [Note] coming under the command of

48th Brigade in 16th (Irish) Division. [Note]

After training in Ireland and in England, in December 1915 the

battalion moved to France for service on the Western Front, [Note] where

they remained for the rest of the war.

The division was introduced to trench warfare at the battle of Loos

and suffered greatly during the action at Hulluch (27th–29th April

1916). Just before dawn on the 27th April, the 16th Division

and part of the 15th Division were subjected to a German gas attack

at Hulluch, a French village north of Loos. The gas cloud and

artillery bombardment were followed by raiding parties that made

temporary lodgements in the British lines. Two days later the

Germans began another gas attack, but the wind turned and blew the

gas back over the German lines. A large number of German

casualties were caused by the change in the wind direction and the

decision to go ahead with the attack against protests by local

officers, and casualties were increased by British troops firing on

German soldiers as they fled in the open. However, the German

gas − a mixture of chlorine and phosgene − was of sufficient

concentration to penetrate the primitive British PH gas helmets [Note]

and the 16th (Irish) Division was unjustly blamed for poor

gas discipline. Production of the Small Box Respirator, [Note]

which had worked well during the attack, was accelerated.

On 27th April, the 16th (Irish) Division lost 442 men, while

the total British casualties from the 27th to the 29th April were

1,980, of whom 1,260 were gas casualties, 338 being killed. In

the Loos sector, between January and the end of May 1916, out of a

total of 10,845 men, the 16th (Irish) Division lost 3,491

including heavy casualties from bombardment and the gas attack at

Hullach in April. Losses of this order were fatal to the

Division’s character, for they could only be replaced by drafts from

England.

The Division was next involved during 1916 in the Battle of the

Somme, in particular in the battles of Guillemont (3rd–6th

September) and of Ginchy (9th September) in which they suffered

heavy casualties − in these actions the Division had 224

officers and 4090 men killed or wounded.

%20Division%20going%20back%20for%20a%20rest%20after%20taking%20Guillemont,%203rd%20September%201916.jpg)

Men of the 16th (Irish) Division

returning for a rest after taking Guillemont,

3rd September 1916.

In 1917 the 16th (Irish) Division was moved to Flanders,

where it took up position beside the 36th (Ulster) Division

below the Messines Ridge. On the 7th June, the two Divisions

took part in the successful assault on the Ridge, but another

severe blow was struck at the Battle of Langemarck (16th-18th

August, part of The Third Battle of Ypres) when the Division was

hurled against strong German defences. By mid August it had

suffered over 4,200 casualties while the 36th Division suffered

almost 3,600, or more than 50% of its numbers. Daily

Telegraph journalist Philip Gibbs, who witnessed this conflict,

later wrote the following account. Many of his comments are

acerbic, especially when analysing “the atrocious Staff work,

tragic in its consequences”:

“The story of the two Irish Divisions, the

36th Ulster and 16th (Nationalist), in their fighting on August

16th, is black in tragedy. They were left in the line for

sixteen days before the battle, and were shelled and gassed

incessantly as they crouched in wet ditches. Every day groups

of men were blown to bits, until the ditches were bloody and the

living lay by the corpses of their comrades. Every day scores

of wounded crawled jback through the bogs, if they had the strength

to crawl. Before the attack on August 16th the Ulster Division

had lost nearly 2,000 men. Then they attacked and lost 2,000

more and over 100 officers. The 16th Division lost as many men

before the attack and more officers. The 8th Dublins had been

annihilated in holding the line. On the night before the

battle hundreds of men were gassed. Then their comrades

attacked and lost over 2,000 more and 162 officers. All the

ground below two knolls of earth called Hill 35 and Hill 37, which

were defended by German pill-boxes, called Pond Farm and Gallipoli,

Beck House and Borry Farm, became an Irish shambles. In spite

of their dreadful losses the survivors in the Irish battalions went

forward to the assault with desperate valour on the morning of

August 16th, surrounded the ‘pill-boxes,’ stormed them through

blasts of machine-gun fire, and towards the end of the day small

bodies of these men had gained a footing on the objectives which

they had been asked to capture, but were then too weak to resist

German counter-attacks. The 7th and 8th Royal Irish Fusiliers

had been almost exterminated in their efforts to dislodge the enemy

from Hill 37. They lost 17 officers out of 21, and 64 per

cent, of their men. One company of 4 officers and 100 men

ordered to capture the concrete fort known as Borry Farm, at all

cost, lost 4 officers and 70 men. The 9th Dublins lost 15

officers out of 17, and 66 per cent, of their men.

The two Irish Divisions were broken to bits, and their brigadiers

called it murder. They were violent in their denunciation of

the Fifth Army for having put their men into the attack after those

thirteen days of heavy shelling, and, after the battle, they

complained that they were cast aside like old shoes, no care being

taken for the comfort of the men who had survived. No

motor-lorries were sent to meet them and to bring them down, but

they had to tramp back, exhausted and dazed. The remnants of

the 16th Division, the poor, despairing remnants, were sent, without

rest or baths, straight into the line again, down south.

I found a general opinion among officers and men, not only of the

Irish Division, under the command of the Fifth Army, that they had

been the victims of atrocious Staff work, tragic in its

consequences. From what I saw of some of the Fifth Army

staff-officers I was of the same opinion. Some of these young

gentlemen, and some of the elderly officers, were arrogant and

supercilious, without revealing any symptoms of intelligence.

If they had wisdom it was deeply camouflaged by an air of

inefficiency. If they had knowledge they hid it as a secret of their

own. General Gough, commanding the Fifth Army in Flanders, and

afterwards north and south of St. Quentin, where the enemy broke

through, was extremely courteous, of most amiable character, with a

high sense of duty. But in Flanders, if not personally

responsible for many tragic happenings, he was badly served by some

of his subordinates; and battalion officers, and divisional staffs,

raged against the whole of the Fifth Army organization, or lack of

organization, with an extreme passion of speech.

‘You must be glad to leave Flanders,’ I said to a group of officers

trekking towards the Cambrai Salient. One of them

answered violently: ‘God be thanked we are leaving the Fifth Army

area!’”

From Realities of War, by

Philip Gibb (1920).

By the spring of 1918, 5th Army’s commander, Hubert Gough, was

undergoing serious criticism of his conduct and was regarded as

perhaps the least-talented or able of Sir Douglas Haig’s generals.

He had also become very unpopular with his troops. Following

the reverses suffered by the 5th Army during the German Spring

Offensive, [Note] on the 4th April

1918 Haig received a telegram from Lord Derby (Secretary of State

for War) ordering that Gough be dismissed on the grounds of “having

lost the confidence of his troops”.

Following the Langemarck action, the 16th (Irish) Division was not

involved in a further major action until the Battle of Cambrai

commenced on 20th November, by which time Rifleman Kempster was

dead. How he met his end is not known. this from the Bucks Herald 20th October 1917:

ROLL OF HONOUR.

− We have this week to announce with deep regret the loss of two men

of the town, both of whom have been killed in action . . . .

Rifleman F. Kempster, Royal Irish Rifles, killed in action October

2, leaves a wife and two children. His home was in

King-street, and previous to the war he was employed as carter by

Mr. William Lockhart, coal merchant. He was well known as a

member of the local corps of the Salvation Army, and an

instrumentalist in the band. The deepest sympathy is felt with

the bereaved families.

From the Parish Magazine, November 1917:

“Frederick Kempster, Rifleman, Royal Irish

Rifles, was killed in action on October 2, 1917. Several of

his friends sent a joint letter to his wife. They wrote ‘He

was a good soldier and was well liked by his comrades. He died

like a soldier, and his body now has a soldier’s grave somewhere in

France’.

Frederick Kempster joined the Army in July 1916 and went to France

in March 1917. He was a good fellow, and a consistent member

of the Salvation Army, where for many years, he was a tenor player.”

Frederick Kempster was born in Tring on the 27th February 1890. In

April 1912 he married Rose Barber in Berkhamstead, and she gave

birth to their son Alfred Frederick on 26th October of that year.

Cojeul British Cemetery was begun by the 21st Division Burial

Officer in April 1917, and used by fighting units until the

following October. It was very severely damaged in later

fighting. The cemetery contains 349 burials and commemorations, 35 of the burials

being unidentified while 31

graves destroyed by shell fire are represented by special memorials.

――――♦――――

ERNEST KING

Private, 4th North Staffordshire Regiment, service no. 42586.

Son of Susannah of 9 Myrtle Cottages, Bulbourne, Tring.

Formerly employed at Apsley Mills.

Died of wounds (sustained in France) at Coombe Lodge Auxiliary Military Hospital,

Essex,

on the 13th February 1919, aged 19.

Buried in Tring Cemetery, grave ref. Row F Grave 64.

Although its roots can be traced back to the 18th century, The North

Staffordshire (infantry) Regiment grew out of the Childers Reforms [Note]

in 1881. The Regiment then served all over the Empire in times

of both peace and war, elements of which took part in many conflicts

such as the Second Sudanese War (1895), the Second Boer War

(1899-1902), the Anglo-Irish War (1919-22) and the Third

Anglo-Afghan War (1919).

At the outbreak of the First World War, the 4th Battalion was

serving as the garrison in Guernsey. In 1916 it returned to

the United Kingdom and in the following year arrived in France

where it served on the Western Front [Note] for the remainder of the war.

Trench warefare.

On the 3rd of February 1918 the 4th Battalion North Staffs joined

the 105th Brigade in the 35th Division. In 1918

they fought in the First Battle of Bapaume (24th–25th March) and the Final Advance in

Flanders, including The Battle of Courtrai and The action of Tieghem.

They crossed the River Scheldt near Berchem on the 9th of November

and by the Armistice they had entered Grammont. They moved

back to Eperlecques and many of the miners in the Regiment were

demobilised in December. In January 1919, units of the

Division were sent to Calais to quell rioting in the transit camps.

The last of the Division were demobilised in April 1919.

The brief obituary published in the Tring Church Parish Magazine

(below) states that Private King arrived in France on the 31st March 1918.

Thus, with the exception of the First Battle of Bapaume (24th-25th

March), it is

possible that he was involved in one or both the actions in which the

Battalion was engaged in 1918 – The Battle of Courtrai

(14th-19th October); The Action of Tieghem (31st October) – but when he received his wound is

not known.

Private King died at Coombe Lodge Auxiliary Military Hospital, Essex.

The hospital, which operated from the 6th November 1914 to the 19th

March 1919, was located in a large country house donated by Evelyn

Heseltine, a successful stockbroker. Shortly before the outbreak of war his daughter,

Muriel, married Brigadier General Cecil Henry De Rougemont.

Whilst her husband was abroad fighting for king and country, Muriel

worked as Commandant of the VAD [Note] Red Cross unit at Coombe Lodge, and

for her services she was awarded an OBE.

Before the war began, the British Red Cross searched for suitable

properties that could be used as temporary hospitals if war broke

out. This meant that as soon as wounded men began to arrive

from abroad, hospitals were largely available for their use, with

staff and equipment in place. Such ‘auxiliary military

hospitals’ were usually staffed by:

a Commandant, who was in charge of the hospital’s administration,

but not its medical

and nursing services;

a Quartermaster, who was responsible for the receipt, custody and

issue of articles in the

provision store;

a Matron, who directed the nursing staff;

members of the local Voluntary Aid Detachment who were trained in

first aid and home

nursing.

Both the reports below state that Ernest died of pneumonia, which,

at this date, suggests that Spanish Influenza might have been the

primary cause of death. [Note]

This from the Bucks Herald, 1st March 1919:

“ROLL OF HONOUR.

− We regret to hear that the Roll of Honour of Tring men who have

given their lives in the war has passed 100. It is our sad

duty this week to record the deaths of yet two more local men. −

Ernest King, North Staffordshire Regiment, had done 12 months

service, joining up when he was 18 years of age, and was quickly

sent over to France. He was badly wounded, was brought home to

England, and for a period had been in hospital. It was hoped

he would make a full recovery, but pneumonia supervened, and he died

on Feb 13. His remains were brought to Tring and laid to rest

in the new cemetery, military honours being accorded by a party from

Halton Camp. The last service was conducted by the Vicar (Rev.

H. Francis).”

From the Parish Magazine, Holy Week, 1919:

“Ernest King, North Staffordshire Regt,

joined twelve months ago, and crossed for France on Easter Day 1918. [31st

March]

He was soon in action, and later on was badly wounded. He was

brought to England and received every care and attention at Combe

Lodge, Great Warley, Near Brentwood in Essex, and great hopes were

entertained for his recovery, but pneumonia carried him off on 13

February.

His body was brought to Tring and laid to rest in our cemetery with

Military honours on 20 February.”

Ernest King’s grave in Tring Cemetery.

――――♦――――

BERTIE LOVEGROVE

Private, “D” Coy, 9th East Surrey Regiment, service number 3012.

Born in Tring. Joseph and Annie Lovegrove, 14 Frogmore Street,

Tring.

Enlisted at Watford. Killed in action on the 25th February

1916.

Buried in Menin Road South Military Cemetery, Ypres, Belgium, grave

ref. I. A. 17.

The East Surrey (infantry) Regiment was formed under the Childers

Reforms, [Note] from the

amalgamation of the 31st (Huntingdonshire) Regiment (which became

its 1st Battalion) and the 70th (Surrey) Regiment (which became its

2nd Battalion). The Regiment contributed greatly to the First

World War, raising 18 battalions. Included in this were seven

service battalions raised as part of Kitchener’s New Army. The

10th and 11th battalions were used for auxiliary purposes and

recruiting, but the 7th, 8th, 9th, 12th and 13th went to France.

Overall, 6000 men were lost and seven Victoria Crosses won.

The 9th (Service) [Note] Battalion

was formed at Kingston-upon-Thames in September 1914 as part of K3.

[Note] Following training, the

Battalion landed at Boulogne on the 1st September 1915 for service

on the Western Front [Note] as part of the 72nd Brigade in the

24th Division. On the 4th September the Division

concentrated in the area between Etaples and St Pol, and a few days

later marched across France into the reserve for the British assault

at Loos, going into action on the 26th of September and suffering

heavy losses.

|

One of the most famous

incidents to occur during the carnage of the first day

of the Battle of the Somme (1st July 1916) was the 8th

Battalion East Surrey Regiment’s famous ‘football’

charge towards the German trenches at Montauban. |

In 1916 the 9th Battalion suffered in the German gas attack

at Wulverghem (30th April and the 17th June) and then moved to The

Somme, seeing action in the battles of Delville Wood (15th July–3rd

September) and of Guillemont (3rd–6th September).

The haunting drama Journey’s End (1928) is a well-known play

about the Great War. Its author, R. C. Sherriff, saw all his

front line service with 9th Battalion. The entire story

plays out in the officers’ dugout over four days from the 18th to

the 21st March 1918, during the run-up to the real-life events of

Operation Michael. [Note]

Bertie Lovegrove was born in the 3rd quarter of 1891. In the

1901 Census he is recorded living at 14 Frogmore Street with his

parents Joseph (a gardener, aged 46) and Annie (aged 50), together

with his Aunt Bessie (aged 39, a straw plait worker) and cousin Lily

(aged 20, a wood box maker). Ten years later the family remain at 14

Frogmore Street, but besides Bertie (aged 20, an ostler, looking

after the horses at the Black Horse, Frogmore Street), the household

has now reduced to Joseph (general labourer), Annie and a boarder

named Betsey Coughfrey (aged 48, charwoman) whose surname suggests

she is related to Annie.

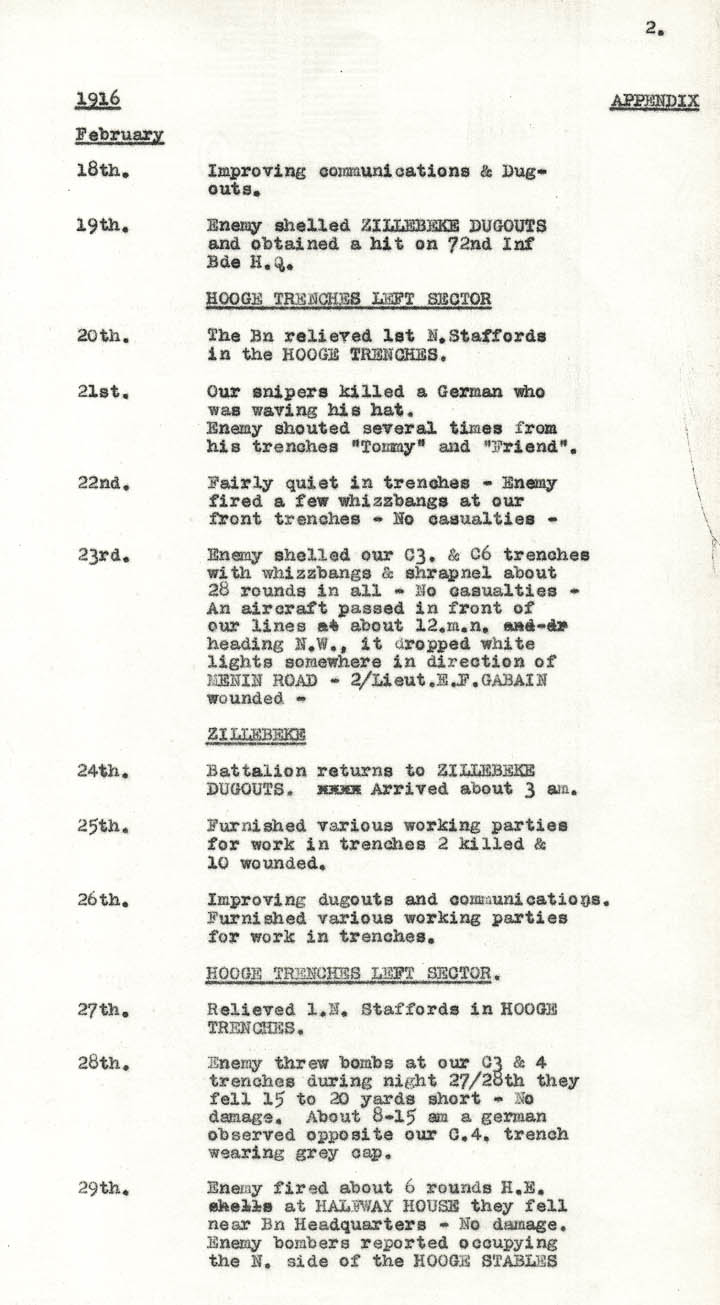

Private Lovegrove was killed in action on the night of the 25th February 1916.

According to its War Diary [Note] entry for that day, the 9th

Battalion was at the village of Zillebeke (scene of the

infamous Battle of Hill 60, 17th April-7th May 1915), about 1½ miles

south-east of Ypres. The single entry states simply: “Furnished

various working parties for work in trenches 2 killed & 10

wounded.” It thus seems likely that Bertie was one of

the two fatalities referred to, possibly falling victim to shellfire

or to a nocturnal raiding party:

From the Parish Magazine, April 1916:

“Bertie Lovegrove, Private in ‘D’ Company

9th Bn East Surrey Regt was killed in action on 25 February 1916.

The sergeant Major of ‘D’ Company writes, in a letter to his

parents:

‘I have sorrowful news for you; your son who was in my company was

killed in action on the night of February 25th. I must tell

you, he died a hero, for his country. He will be missed by all

of his comrades in the company.

For myself, his loss will be great, for he was a good soldier and a

brave lade. He seemed to have a presentiment that he was going

to die, but for the last three days in action, he was the brightest

of boys, trying to cheer everybody up. We all feel for you in

your distress.’”

The Menin Road ran east and a little south from Ypres to a front

line which varied only a few kilometres during the greater part of

the war. The position of this cemetery was always within the

Allied lines. It was first used in January 1916 by the 8th

South Staffords and the 9th East Surreys, and it continued to

be used by units and Field Ambulances until the summer of 1918.

The cemetery was increased after the Armistice when graves were

brought in from isolated positions on the battlefields.

There are now 1,657 servicemen buried or commemorated in this

cemetery. 118 of the burials are unidentified but special

memorials are erected to 24 casualties known or believed to be

buried among them. In addition, there are special memorials to

54 casualties who were buried in Menin Road North Military Cemetery,

whose graves were probably destroyed by shell fire and could not be

found.

――――♦――――

ARTHUR LOVELL

Private, 54th (East Anglian) Infantry Division, Machine Gun Company, service no. 50477.

Son of Alfred and Mary of 7 Bunstrux Hill, Tring.

Died of

Malaria [Note] in the Lebanon on the 16th November 1918 aged 26.

Buried in Beirut War Cemetery, Lebanon, grave ref. 123.

The 54th (East Anglian) Division [Note]

was a formation of the Territorial Force, [Note]

formed as a result of the Haldane reforms of 1908. As such it

was one of 14 Divisions of the peacetime TF.

On the 8th July 1915, the Division was ordered to refit for service

at Gallipoli. Leaving the artillery and train behind, the rest

of the Division sailed from Liverpool and Devonport, the first ships

reaching Lemnos on the 6th August. On the 10th August units

landed at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli, as part of IX Corps and took part in

operations in the Sulva area before being evacuated from Gallipoli

in December (only 240 officers and 4480 men strong).

Private Lovell joined the Bedford Regiment in June, 1915, and

was later transferred to the Norfolk Regiment, joining the

54th Division Machine Gun Company. This Company was formed

in April and May 1916 from a merger of the 54th Division’s three

existing Brigade − i.e. the 161st (Essex) Brigade, 162nd

(East Midland) Brigade, and 163rd (Norfolk & Suffolk) Brigade −

machine gun companies.

Ottoman artillerymen at Hareira in 1917

before the Southern Palestine offensive.

During 1916, the 54th Division formed part of the Suez Canal

defences, and in the following two years took part in the Gaza and

Southern Palestine offensives. [Note] On the date of the Armistice

with Turkey (31st October 1918) the Division was concentrated at

Beirut, where Private Lovell died from malaria.

From the Parish Magazine December 1918:

“Just as we go to press, we hear that

Arthur Lovell, Machine Gun Corps (Norfolk Regt) has died of malarial

fever at Alexandria [but see below].

He has been in the Army for the last three and a half years, for the

greater part of this time, with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force.

He was a great favourite with all who knew him. His parents,

who have now lost two sons, have our deepest Sympathy. R.I.P.”

From the Parish Magazine, January 1919:

“Of Arthur Lovell, whose death was recorded

in our last number Major Culme Seymore writing to his parents , says

‘Your son was only two days in hospital at Beyrouth,

[French for Beriut] having been admitted

there on 14th November, so his death was sudden.

It may be of some consolation to you to know he was spared a

lingering illness. He has served with me since the Machine Gun

Corps was formed in 1916. You will be pleased to know, that he

was a good soldier and did his work well, both in action and when

out of the front line.

I send you my deepest sympathy. He was buried at Beyrouth on

Sunday 17th November.’

A letter from one of his mates says:

‘Jerry, as we used to call your son, was a good soldier and a great

mate, and I assure you will be greatly missed by us all. He

was always merry and bright, and tried to live a godly life.

This letter conveys to you and yours, the deepest sympathy of myself

and all the boys in A section.’”

Lebanon was taken from the Turks in 1918 by Commonwealth forces with

small French and Arab detachments. Beirut was occupied on the

8th October 1918, and the 32nd and 15th Combined Clearing Hospitals

were sent to the town.

The Beirut War Cemetery was begun in October 1918 and was later

enlarged when graves were brought in from other burial grounds in

the area. Commonwealth burials and commemorations now total

628 for the First World War and 531 for the Second World War.

The cemetery also contains a number of war graves of other

nationalities, many of them Greek and Turkish.

――――♦――――

FREDERICK LOVELL

Private, 13th Essex Regiment, enlisted at East Ham, Essex, service

no. 17199.

Born in Tring. Son of Mr. and Mrs A. Lovell of Akeman Street, Tring.

Husband of Mrs. E. E. Stocker (formerly Lovell) of 1 Pinewood

Cottages, Pinewood Road, Ash, Surrey.

Killed in action the 2nd August 1916 aged 28.

Buried in Dantzig Alley British Cemetery, Mametz, France, grave ref.

VIII. C. 8.

There is some confusion over both Frederick’s rank and his unit,

with different burial documents stating Lance Corporal and Private,

and the 13th Essex and the 15th Essex respectively. Rank is unimportant in

this context, but unit is, so I have selected the Commonwealth War

Grave Commission information, which places him in the 13th Battalion

(West Ham) Essex Regiment, ‘The West Ham Pals’.

The Essex Regiment was a line infantry regiment formed in 1881 under

the Childers Reforms [Note] by the

amalgamation of the 44th (East Essex) Regiment of Foot and the 56th

(West Essex) Regiment of Foot, which then became the 1st and 2nd

battalions of the new regiment. During the First World War,

the Essex Regiment provided 30 infantry battalions to the British

Army. In 1914, three service [Note]

battalions (9th, 10th and 11th) and one reserve battalion (12th)

were formed from volunteers as part of Kitchener’s Army. [Note]

A further service battalion, the 13th West Ham, was raised by the

Mayor and Borough of West Ham. Initially recruits came from

West/East Ham, Forest Gate, Custom House, Barking and Stratford but

others from abroad joined the regiment. Overall, some 9000

officers and men of the Essex Regiment died in the 1914-18 War, many

having no known grave.

In November 1915, the 1200 strong West Ham Battalion landed in

Boulogne after which they saw action in most of the major battles on

the Western Front. [Note] Initially

under orders from the 100th Brigade in the 33rd Division, on the

22nd December 1915 the 13th Battalion was transferred to the 6th

Brigade in the 2nd Division, as part of which they were involved in

major actions including, in:

1916, The Battle of Delville Wood, The Battle of the Ancre and

Operations on the Ancre;

1917, The German retreat to the Hindenburg Line, The First Battle of

the Scarpe, The Battle of Arleux, The Second Battle of the Scarpe,

The Battle of Cambrai.

Frederick Lovell was killed in action on the 2nd August, 1916 where,

between the 29th July and the 4th August, his unit was in the front

line in Delville Wood.

Delville Wood, 20th September 1916.

Following the successful dawn attack of the 14th July, the newly won

British line formed a salient, the right side of which was

threatened by German positions in Delville Wood. The wood

needed to be taken, a task fell to the South African Brigade.

During the attack the South Africans came under withering German

artillery fire that almost completely destroyed both the wood and

their battalions. The Brigade had gone into battle with a

strength of 121 officers and 3,032 other ranks − at roll call on

21st July they numbered a mere 29 officers and 751 other ranks.

Mud and rainwater covered the bodies of South Africans and Germans

alike, many of whom remain in the wood today.

Vicious fighting for Delville Wood continued for another six weeks,

the advantage continuously changing from one side to the other.