|

Lest We

Forget

by

Wendy Austin

In

Britain the searing grief experienced by millions following the

horrors of World War One left many people numb and in a state of

shock. Gradually, all seemed to agree that the sacrifice

of the serving men should be commemorated in some way, but the

length of time it took to decide on the style, siting, and fund

raising method for a war memorial varied greatly from community

to community. (The war memorial in Tring was most unusual

in that it was erected and dedicated shortly before the

Armistice of November 1918 – in fact Tring was written up as

setting a splendid example to the nation as a whole.)

In

the villages north of Tring, it took three years from the time

that the subject was first broached until the erection of the

completed memorial. The historic day for Long Marston and

Marsworth fell on Sunday afternoon 7th August 1921 when the

second Lord Rothschild performed both unveiling ceremonies,

dressed in the uniform of his regiment, the Bucks Yeomanry.

Long

Marston selected as its design a Celtic cross carved from a

single slab of silver-grey granite set upon three high steps,

and sited in the centre of the village near the school (which

no-one then dreamed would be totally destroyed by bombing twenty

later during the next world conflict). It was estimated

that the cost would be £400 after allowing for carving the names

and inscription, supplying a rail fence, laying turf, and

planting ornamental trees. It is recorded that the

foundations were set by James Chandler & Son of Long Marston,

and the erection carried out by Newman & Harper of Aylesbury.

Before the ceremony the villagers assembled to the music of the

Long Marston Band, and ex-servicemen under the charge of

Sergeant Proctor formed a guard of honour for Lord Rothschild.

As it happened, a London troop of Boy Scouts were camped in

nearby fields, and two of their officers acted as standard

bearers. The short service was conducted by the Rev. R. H.

Rowden, assisted by Mr. Bates of Aylesbury representing the

village’s Wesleyan Methodist Church, following which a speech

given by Lord Rothschild in which he laid great stress on “the

call of duty”. Whether or not the fine words held any

shreds of comfort for the bereaved wives, mothers, fathers,

fiancées, and others, we cannot know.

The

party then progressed to Marsworth to perform a similar

ceremony. Marsworth architect A. J. Gurney charged no fee

for his design of a Gothic cross, which was sited in a prominent

position in the churchyard on rising ground fronting the road.

Constructed of Portland stone gifted by William Mead, owner of

Tring Flour Mill, the cost of carving and erection amounted to

£140, which was raised by public subscription. Of the 55

men of Marsworth who served in the Great War, 11 did not return

and their names are inscribed on the base of the cross. A

similar speech by Lord Rothschild was followed by the sounding

of the Last Post by trumpeters from the Wendover Boys’ Brigade,

and their band led the singing of the National Anthem.

Three

months later on 3rd October 1921, the village folk of Wilstone

experienced the same sad occasion as their neighbours.

Again, the design chosen was a Celtic cross made of Cornish

granite, but it did have one notable difference, for the base

was of stone that originally formed part of the swing bridge

over the Wendover Arm of the Grand Junction Canal. This,

and the generous donation of railings by local farmer Percy

Mead, helped to keep costs down to £140. After a service

on the village green led by the Rev. R. H. Rowden, Percy Mead

read out the nine names of the fallen and Capt. G. M. Brown MC

of Tring unveiled the memorial and addressed the crowd.

Following a minute’s silence, a prayer was said by Arthur

Bagnall representing Wilstone Baptist Church and the Long

Marston Band, under the baton of Mr Prothero, played the Last

Post followed by the Reveille sounded by a troop of RAF

trumpeters.

The

scenes enacted in these villages no doubt followed a similar

pattern and were accompanied by the same emotions as those

experienced by every community across the land. But it is

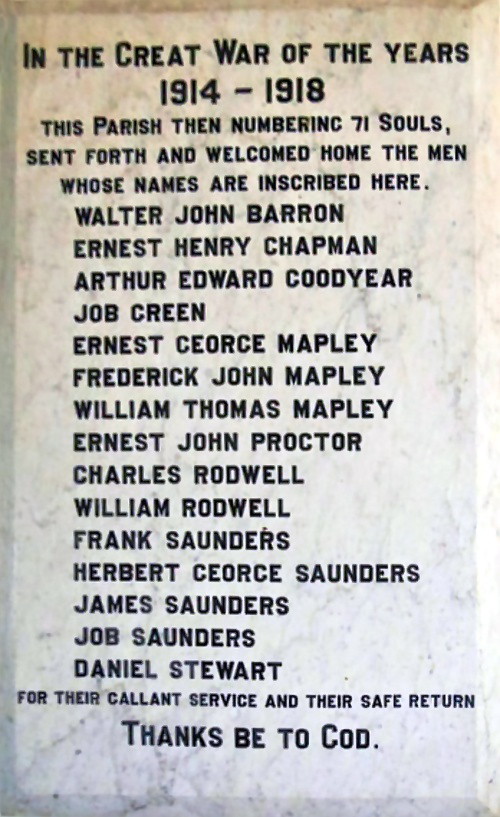

good to remember that in Puttenham things turned out

differently. This tiny hamlet can be called a ‘Thankful

Village’, that is, one that lost no men in the carnage of the

Great War. The term was first used by historian Arthur Mee,

who estimated that at most there were 32 such villages and

hamlets in the whole of Britain, although he could only

positively identify 24. Puttenham was certainly the only

one in Hertfordshire, and the relief and joy that greeted the 15

returning servicemen can only be imagined, although how much

physical and mental scarring they carried home with them is

impossible to say. At the Harvest Thanksgiving service of

1925, a tablet was unveiled in the south aisle of St. Mary’s

Church. Its simple inscription speaks for itself:

|

|