|

|

“Good-morning,

good-morning!” the General said

When we met him last week on our way to the line.

Now the soldiers he smiled at are most of

’em dead,

And we’re

cursing his staff for incompetent swine.

“He’s a cheery old card,” grunted Harry to Jack

As they slogged up to Arras with rifle and pack.

But he did for them both by his plan of attack.

The General, by

Siegfried Sasoon |

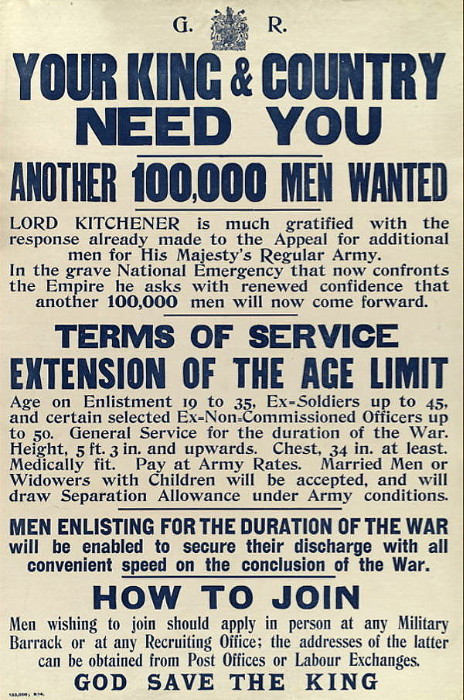

“KITCHENER’S ARMIES”: “Your King and Country need you: a call to arms” was a

recruiting poster published on the 11th August 1914. It

explained the new terms of service and called for 100,000 men to

enlist, a figure that was achieved within two weeks. Army

Order 324, dated 21st August 1914, then specified that six new

Divisions would be created from units formed of these volunteers,

collectively called “Kitchener’s Army” or K1. It

also detailed how the new infantry battalions would be given numbers

consecutive to the existing battalions of their regiment, but with

the addition of the word ‘Service’ after the unit number.

On the 28th August 1914, Kitchener asked for a further 100,000

volunteers. Army Order 382, issued on the 11th September 1914,

specified an additional six Divisions, which were to be called

K2.

They were organised on the same basis as K1, and came under War

Office control. A third 100,000 recruits followed and were

placed into another six Divisions, called K3, to be organised

on the same basis as K1 and K2 under War Office control.

Enough men came forward not only to fill the ranks of K3, but to

form reserves, which were initially formed up into the six Divisions

of K4.

GENERAL PLUMER: of squat figure and ruddy countenance, with monocle and white

moustache, the appearance of Field Marshal Herbert Charles Onslow

Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE (1857-1932) − as

he later became − sometimes caused amusement, but it belied one of

the most effective and successful First World War generals.

Plumer was a meticulous planner, cautious and impossible to fluster.

He won an overwhelming victory over the German Army at the Battle of

Messines in June 1917, which he followed with further victories at

the battles of the Menin Road Ridge, of Polygon Wood and of

Broodseinde. Plumer later commanded the Second Army during the

German Spring Offensive and the Allied Hundred Days Offensive in the

final stages of the war.

ARMY HIERARCHY:

the following hierarchy, by which the British Army was organised and

controlled at the time of the Great War is not exhaustive, but is sufficient to

cover the terminology used in the accompanying biographical notes.

PLATOON: each battalion

(see below) was divided into four companies (see below). A

company consisted of four platoons, each of about 50 men, under a

Lieutenant or Second-Lieutenant, assisted by a Sergeant.

Within a platoon were four sections of 12 men. A crucial part

of the platoon officer’s job was to care for the welfare of his men,

even down to inspecting their feet daily for signs of trench foot.

COMPANY: a military unit, typically consisting of 80–250 soldiers

and usually commanded by a major or a captain. Most companies

were formed from four platoons named alphabetically A through D.

BATTALION: a military unit typically

commanded by a lieutenant colonel and consisting of

1,000 men divided into four companies plus a machine

gun section. In

addition to consisting of sufficient personnel and equipment

to perform significant operations, as well as a

limited self-contained administrative and logistics capability, the

commander was provided with a full-time staff whose function was to

coordinate current operations and plan future operations.

REGIMENT: during

peacetime is the key administrative component of the British

Army and the largest permanent organisational unit. It

is typically commanded by a colonel and divided into two or more

battalions, which during war do not necessarily fight

together.

BRIGADE: a major tactical military formation typically

comprising three to six battalions plus supporting elements

and commanded by a Brigadier.

Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

DIVISION: a large military unit or formation, usually

commanded by a major-general and consisting

of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. Infantry divisions during the

World Wars ranged between 10,000 and 30,000 in nominal strength

comprising several regiments or

brigades possessing a range of specialities − Headquarters staff;

Infantry; Artillery; Ammunition column; Engineers; Signals; Medical;

Logistics and Cavalry.

CORPS: in military terminology a corps

(not to be confused with military units that had

‘corps’

in their title, such as Royal Army Medical Corps) was an operational

formation, usually commanded by a lieutenant-general, consisting of

two or more divisions. When the British Army was expanded from an

expeditionary force in the First World War, corps were created to

manage the large numbers of divisions.

ARMY: a field army (or numbered army, or simply army) is a military

formation in many armed forces, composed of two or more corps and

may be subordinate to an army group usually commanded by a general. A field army is composed

typically of 100,000 to 150,000 troops.

SERVICE BATTALIONS: in August 1914 Lord Kitchener called for

more men to fight, and by September half a million men had enlisted.

Known at the time as Kitchener’s Army, the new army consisted of

over 500 battalions. They were numbered consecutively after

the existing battalions of their regiment and were distinguished by

the word “service”, this indicating that they were intended to serve

only for the duration of the war.

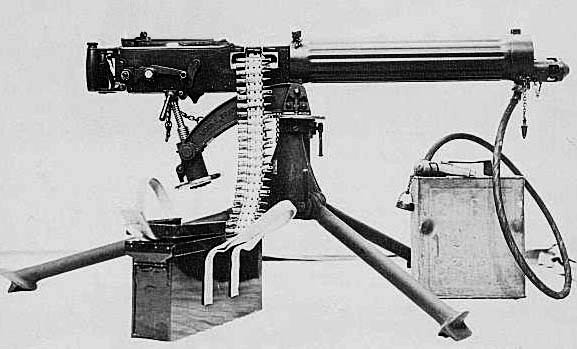

MACHINE GUN CORPS: at the outbreak of war, each infantry battalion and cavalry regiment

had a machine gun section equipped with just two guns served by a

subaltern and 12 men. Battle

experience soon revealed that to be fully effective machine guns

needed to be used in larger units crewed by men who were thoroughly

conversant with their weapons and who understood how they should be

deployed for maximum effect. To achieve this the MGC was

formed, with Infantry, Cavalry, and Motor branches, followed in 1916

by a Heavy Branch. The Infantry Branch was by far the largest

and was formed by the transfer of battalion machine gun sections to

the MGC, these sections being grouped into Brigade Machine Gun

Companies with three per division, later increased to four.

In 1914, machine gun sections were equipped with Maxim guns, by then

obsolete. Shortly after the formation of the MGC, the Maxim

guns were replaced by the Vickers, which became a standard gun for

the next five decades. The Vickers machine gun is fired from a

tripod and is cooled by water held in a jacket around the barrel.

The gun weighed 28½ pounds, the water another 10 and the tripod

weighed 20 pounds. Bullets were assembled into a canvas belt,

which held 250 rounds and would last 30 seconds at the maximum rate

of fire of 500 rounds per minute. Two men were required to

carry the equipment and two the ammunition. A Vickers machine

gun team also had two spare men.

Vickers machine gun with ammunition and

water-cooling.

In its short history − it was disbanded in 1922 − the MGC gained an

enviable record for heroism as a front line fighting force, but had

a less enviable record for its casualty rate. Some 170,500

officers and men served, with 62,049 becoming casualties, including

12,498 killed, earning it the nickname “the Suicide Club.”

LEWIS GUN: a First World War-era

shoulder-held air-cooled light machine gun of US design that was

perfected and mass-produced in the United Kingdom. It was

widely used during both world wars – as an aircraft machine gun

almost always with the cooling shroud removed – and served until the

end of the Korean War.

The Lewis weighed 26 pounds and

loaded with a circular magazine containing 47 rounds.

The rate of fire was 500–600 rounds per minute in

short bursts. The weapon was carried and fired by one

man, but he needed another to carry and load the

magazines.

Cartridge (British) .303; Rate of fire 500–600 rounds/min; Effective

firing range 880 yards.

Above: the Lewis light machine gun:

Below, Lewis Limber.

SPECIAL RESERVES: the Reserve Forces Act (1907) was intended

to provide a well-trained reserve for the Regular Army that was

capable of providing individual reinforcements or drafts at short

notice as well as an efficient and cost effective Home Defence

organisation. Before the introduction of the Reserve Forces

Act, Home Defence was the responsibility of the Volunteer Battalions

and the Yeomanry and the Reinforcement of the Regular Army was the

responsibility of the Militia. Thus, the Special Reserves was

a form of part-time soldiering in which men would enlist for 6

years. Their service began with six months full-time training

(paid the same as a regular) after which they received 3 to 4 weeks

training per year.

FIELD MARSHALL ALLENBY (1st Viscount Allenby, 1861–1936): fought

in the Second Boer War and in the First World War. After

periods in command of the British cavalry and the 5th Corps, he

became commander of the 3rd Army in October 1915 and was prominently

engaged at the Battle of Arras (9th April-16th May 1917), following

which he was transferred to Egypt. Although Allenby regarded

this transfer as a badge of failure, his service in the Middle East

was to prove most distinguished. In June 1917 he took command

of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, in which the strength of his

personality lifted moral (Montgomery’s arrival in the Western Desert

was later to have the same effect on his force). After careful

preparation and reorganization he won a decisive victory over the

Turks at Gaza, which led to the capture of Jerusalem on the 9th

December 1917. Further advances were checked by calls from

France for his troops, but after receiving reinforcements, he won a

decisive victory at Megiddo on the 19th September 1918, which,

followed by his capture of Damascus and Aleppo, ended Ottoman power

in Syria.

Allenby’s success in these campaigns was attributable partly to his

skilful and innovative use of cavalry and other mobile forces in

positional warfare. Overall, his defeat of the Ottomans more

than redeemed any reputational setback he suffered in France.

THE BATTLE OF THE BOAR’S HEAD: an attack on the 30th June

1916 at Richebourg-l’Avoué in France. Troops of the British

39th Division of the XI Corps in the First Army, advanced to capture

the Boar’s Head, a salient held by the German 6th Army. Two

battalions of the 116th Brigade, with one battalion providing

carrying parties, attacked the German front position before dawn on

the 30th June. The British took and held the German front line

trench and the second trench for several hours before retiring,

having lost 850–1,366 casualties. In fewer than five hours the

three Southdowns battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment lost 17

officers and 349 men killed, including 12 sets of brothers, three

from one family. A further 1,000 men were wounded or taken

prisoner. In the regimental history it is known as “The Day

Sussex Died”.

CARRYING PARTIES: carried forward ammunition, equipment, food

etc. from the rear area to the front lines. Providing carrying

parties seems to have been a fate allotted to new battalions

arriving in France and at the front for the first time. It was

part of the process of acclimatising them to the front lines.

Carrying parties could also be detailed as an integral part of

attacking waves, bringing up stores and ammunition, further defence

stores for holding newly won ground or trenches (wire, pickets,

sandbags, revetting material, duckboards and A-Frames) and assisting

with the carriage of machine guns and trench mortars.

YEOMANRY: is a designation used

by a number of units or sub-units of the British Army Reserve,

descended from volunteer cavalry regiments. On the eve of

World War I there were 55 Yeomanry regiments (with two more formed

in August 1914), each of four squadrons instead of the three of the

regular cavalry. Upon embodiment these regiments were either

brought together to form mounted brigades or allocated as divisional

cavalry. For purposes of recruitment and administration the

Yeomanry were linked to specific counties or regions, identified in

the regimental title. Some of the units still in existence in

1914 dated back to those created in the 1790s while others had been

created during a period of expansion following on the Boer War.

THE TERRITORIAL FORCE (TF): was originally formed by

the Secretary of State for War, Richard Burdon Haldane, following

the enactment of the Territorial and Reserve Forces Act (1907).

This combined and re-organised the old Volunteer Force with the

Yeomanry. As part of the same process, remaining units of

militia were converted to the Special Reserve. [Note]

The TF was formed on the 1st April 1908. It comprised fourteen

infantry divisions and fourteen mounted yeomanry brigades, with an

overall strength of approximately 269,000. The first fully

Territorial division to join the fighting on the Western Front was

the 46th (North Midland) Division in March 1915, with divisions

later serving in Gallipoli and elsewhere. As the war

progressed, and casualties mounted, the distinctive character of

territorial units was diluted by the inclusion of conscript and New

Army drafts. Following the Armistice all units of the

Territorial Force were gradually disbanded. New recruiting

started in early 1920, and the Territorial Force was reconstituted

on the 7th February 1920. On the 1st October 1920, the

Territorial Force was renamed the Territorial Army.

|

|

|

Field Marshall Sir John

French, pictured August 1915. |

THE HOHENZOLLERN REDOUBT:

a defensive labyrinth of trenches and machine-gun posts, it

protected an important German artillery observation point known as

Fosse 8, and was considered to be one of the strongest positions on

the entire Western Front in 1915. Named after

the House of Hohenzollern, the redoubt was fought over by German and

British forces. Engagements took place from the Battle of Loos (25th

September–14th October 1915) to the beginning of the Battle of the

Somme on the 1st July 1916. On the 13th October 1915, during

the Battle of Loos, the 46th North Midland Division undertook the

main assault on the Hohenzollern Redoubt, resulting in 3,643

casualties within the first ten minutes of action. The British

Official History of the war calls the attack “nothing but the

useless slaughter of infantry”.

FIELD MARSHALL SIR JOHN FRENCH, 1st EARL OF YPRES (1852-1925):

following a varied and distinguished career, which included the

Sudan Campaign of 1884-85 and notable service as a cavalry officer

in the Boer War, French was promoted to Field Marshal in 1913.

From 1912 to 1913 he served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff.

French was appointed Commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF)

at the start of World War I. When the line stabilized in 1915,

a series of stalled BEF offensives led to doubts about his

competence. Criticized for his indecisiveness with reserve

forces at the Battle of Loos, French resigned his post in late 1915.

He was created a viscount in 1916 and an earl in 1922, serving as

Commander in Chief of the British home forces and then Lord

Lieutenant of Ireland during those later years.

Despite recent attempts to give French’s strategic thought some

coherency, historians judge him unfit to have commanded at the

highest level.

|

|

|

Field Marshall Haig in 1924. |

FIELD MARSHALL DOUGLAS HAIG, 1st EARL HAIG (1861–1928):

commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front

from late 1915 until the end of the war. He was commander

during the Battle of the Somme – the battle with one of the highest

casualties in British military history – the Third Battle of Ypres,

and the Hundred Days Offensive, which led to the armistice of the

11th November 1918.

Although he gained a favourable reputation during the immediate

post-war years, since the 1960s he became an object of criticism for

his leadership during the First World War, during which the forces

under his command sustained two million casualties.

The Canadian War Museum comments, “His epic but costly offensives

at the Somme (1916) and Passchendaele (1917) have become nearly

synonymous with the carnage and futility of First World War battles.”

However, more recently historians have argued that this criticism

failed to recognise the adoption of new tactics and technologies by

forces under his command, the important role played by British

forces in the Allied victory of 1918, and that the high casualties

were a consequence of the tactical and strategic realities of the

time.

Haig’s military career ended in January 1920, following which he

devoted the rest of his life to the welfare of ex-servicemen.

|

|

|

Kaiser Wilhelm II

(1859-1941) |

THE BRITISH EXPEDITIONARY FORCE (BEF): was an army

established by Richard Haldane, Minister for War, following the

Second Boer War. Its purpose was to ensure that Britain had a

fully trained and prepared army that was able to deploy quickly to

conflicts. At the outbreak of war, the BEF comprised

approximately 120,000 full time soldiers supplemented by a Special

Reserve consisting of members of the territorial army. It

deployed very quickly – the first British troops arrived on the

Western Front just 3 days after the declaration of war with the

remainder of the force following soon after. The BEF, together

with the French army, was able to slow and then stop the German

advance into France and Belgium, but at great cost. By the end

of 1914 the BEF was having to be supplemented by volunteers and

recruits.

At the outset the BEF was commanded by Sir John

French, but he was replaced by Sir Douglas Haig

in December 1916. By then the majority of soldiers deployed in

the Western Front comprised ‘Kitchener’s Army’

recruits and conscripts, along with many soldiers from the Empire.

THE OLD CONTEMPTIBLES: although there is no documentary

evidence of it, it is alleged that on the 19th August 1914, at his

headquarters in Aix-la-Chapelle, Kaiser Wilhelm II gave this order:

“It is my Royal and Imperial Command that you concentrate your

energies, for the immediate present upon one single purpose, and

that is that you address all your skill and all the valour of my

soldiers to exterminate first the treacherous English; walk over

General French’s contemptible little Army.” Hence the British

Expeditionary Force, the B.E.F., became known as The Old

Contemptibles.

THE MESSINES MINES: deep mining beneath Hill 60 began in late

August 1915. When complete, the Hill 60 mine was charged with

53,300 pounds (24,200 kg) of explosives and a branch gallery under

the nearby Caterpillar took a 70,000-pound (32,000 kg) charge.

At 3:10 a.m. on the 7th June 1917 these and other mines – filled in

total with 990,000 pounds (450,000 kg) of explosives – were

detonated under the German lines, the blasts creating one of the

largest explosions in history (reportedly heard in London and

Dublin) killing some 10,000 German soldiers. In total 19 mines

were exploded over a period of 19 seconds, mimicking the effect of

an earthquake and ranking among the largest non-nuclear explosions

of all time. That the detonations were not simultaneous added

to the terrorising effect on German troops, as the explosions moved

along the front. An eye-witness reported:

“The artillery preparations which for days

had been intense had died down and the night was comparatively

quiet. Suddenly, all hell broke loose. It was

indescribable. In the pale light it appeared as if the whole

enemy line had begun to dance, then, one after another, huge tongues

of flame shot hundreds of feet into the air, followed by dense

columns of smoke which flattened out at the top like gigantic

mushrooms. From some craters were discharged tremendous

showers of sparks, rivalling everything ever conceived in the way of

fireworks.”

HALTON PARK: at the outbreak of war the Park, on the

outskirts of Wendover, was offered to the War Office by Alfred de

Rothschild for use as a training camp. The first division to

arrive was the 21st Yorkshire Division, which had its divisional HQ

at Aston Clinton House (demolished in the late 1950s). Halton

House was lent to the Royal Flying Corps, which, from the 1st April

1918 became the Royal Air Force. Devastated by the carnage of

the war, Alfred de Rothschild’s health began to fail and he died in

1918. Having no legitimate children, the house was bequeathed

to his nephew Lionel Nathan de Rothschild who detested the place and

sold it at auction in 1918. The house and by now diminished

estate were purchased for the Royal Air Force by the Air Ministry

for a bargain £115,000.

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME: during discussions held in December

1915, the French and British committed themselves to an offensive on

the Somme, an area of northern France named after the Somme river.

They agreed on a strategy of combined offensives in 1916, with

initial plans calling for the French army to undertake the main part

of the offensive supported on the northern flank by the Fourth Army

of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). However, on the 21st

February 1916 German Army launched the Battle of Verdun, resulting

in the French diverting many of the divisions intended for the Somme

to the Verdun theatre, and what in the the plan was to be a

“supporting” attack by the British became the principal effort.

The Battle of the Somme was one of the most bitterly contested and

costly series of battles of the First World War, lasting for nearly five

months. Despite this, it is often the first day of the battle

that is most remembered, for British forces suffered 57,470

casualties (including 19,240 killed), the largest loss ever suffered

by the British Army in a single day.

The offensive began on 1st July 1916 after a week-long artillery

bombardment of the German lines. Advancing British troops

found that the German defences had not been destroyed as expected

and many units suffered very high casualties with little progress.

The Somme became an attritional or ‘wearing-out’ battle. On

the 15th September tanks were used for the first time with some

success, but they did not bring a breakthrough any closer.

Operations on the River Ancre continued with some gains, but in

deteriorating weather conditions major operations on the Somme ended

on the 18th November.

|

|

|

Captain Lionel William

Crouch (1886-1916) |

Over the course of the 5-month battle, British forces took a strip

of territory 6 miles deep by 20 miles long. But improvements were

made in the use of artillery and infantry tactics, and new weapons,

including tanks, began to be integrated in the British Army’s

methods.

LIONEL CROUCH: son of William Crouch, a Clerk of the Peace to

Buckinghamshire County Council, and Helen Marian Crouch née Sissons.

He had a younger brother Guy R. Crouch (who became a captain in the

1st Bucks Battalion of the British Army and was awarded the Military

Cross) and a sister Doris. The family home was Friarscroft in

Aylesbury.

Lionel was educated at Marlborough College from 1900 to 1904.

Having qualified as a solicitor in 1909, he worked for Horwood and

James in Aylesbury and was also a deputy Clerk of the Peace for

Buckinghamshire. His brother was also a solicitor, with

Parrott and Coales. A keen philatelist, Crouch was

vice-president of the Junior Philatelic Society.

Captain Crouch was an officer in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire

Light Infantry, part of the Territorial Force, before the start of

the First World War. On the outbreak of the war, in July 1914,

the Territorials were mobilised and Captain Crouch left Aylesbury on

the 4th August while his brother Guy and the bulk of the men left

the town by rail the following day. They arrived in Cosham for

training with not a man missing which was a source of pride to

Crouch. His battalion left Chelmsford for the front on the

30th March 1915.

Lionel was shot during an attack on Pozieres on the 21st July 1916.

While being dragged back by his orderly he was hit a second time and

died ten minutes later. He is buried in Pozieres

Cemetary. His father published Lionel’s letters from the front

to him privately under the title

Duty and Service: letters from the front − the

proceeds of the publication he donated to war charities.

MINENWERFER (“mine launcher”): is the German name for a class of

short range mortars used extensively during the First World War by

the German Army. The weapons were intended to be used by

engineers to clear obstacles including bunkers and barbed wire, that

longer range artillery would not be able to accurately target.

It was loaded from the muzzle like a typical mortar, but did have a

rifled barrel and a hydraulic recoil dampening system.

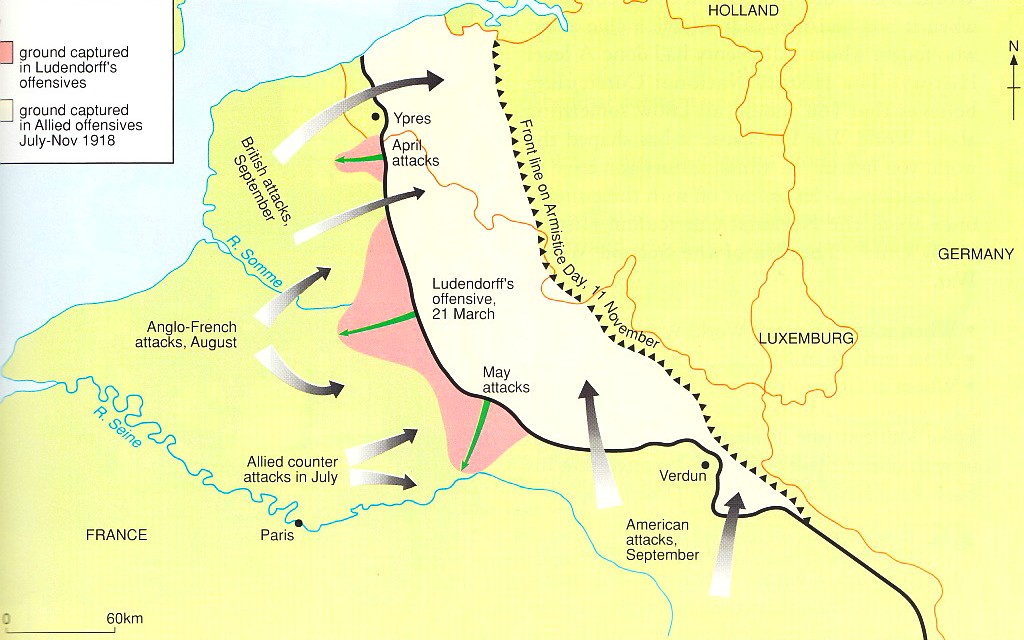

THE 1918 SPRING OFFENSIVE – a.k.a. THE LUDENDORFF OFFENSIVE

(see map below):

was a series of German attacks along the Western Front beginning on

the 21st March 1918. Although ultimately a failure, it was the

nearest the German Army came to a decisive breakthrough on the

Western Front during the entire war.

The Germans realised that their remaining

chance of victory was to defeat the Allies before the overwhelming

human and material resources of the United States could be fully

deployed. They also had the temporary advantage in numbers

afforded by the nearly 50 divisions freed by the Russian surrender

(the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk).

There were four German offensives, codenamed Michael,

Georgette, Gneisenau and Blücher-Yorck.

Michael was the main attack, which was intended to break through

the Allied lines, outflank the British forces which held the front

from the Somme River to the English Channel and defeat the British

Army. Once this was achieved, it was hoped that the French

would seek an armistice. The other offensives were subsidiary

to Michael and were designed to divert Allied forces from the

main offensive on the Somme.

No clear objective was established before the start of the

offensives and once the operations were underway, the targets of the

attacks were constantly changed according to the battlefield

situation. The Allies concentrated their main forces in the

essential areas (the approaches to the Channel Ports and the rail

junction of Amiens), while leaving strategically worthless ground,

devastated by years of combat, lightly defended.

The Germans were unable to move supplies and reinforcements fast

enough to maintain their rapid advance. The fast-moving

stormtroopers leading the attack could not carry enough food and

ammunition to sustain themselves for long and all the German

offensives petered out, in part through lack of supplies.

By late April 1918, the danger of a German breakthrough had passed.

The German Army had suffered heavy casualties and now occupied

ground of dubious value which would prove impossible to hold with

such depleted units. In August 1918, the Allies began a

counter-offensive with the support of large numbers of fresh American

troops, and using new artillery techniques and operational methods.

This Hundred Days Offensive [Note]

resulted in the Germans retreating or being driven from all of the

ground taken in the Spring Offensive, the collapse of the Hindenburg

Line and the capitulation of the German Empire that November.

THE HUNDRED DAYS OFFENSIVE (see map above): was the final period of the First World War,

during which the Allies launched a series of offensives against the

Central Powers on the Western Front from 8th August to 11th November

1918, beginning with the Battle of Amiens. The offensive essentially

pushed the Germans out of France, forcing them to retreat beyond the

Hindenburg Line and, on the 11th November, was followed by an armistice.

BITE AND HOLD: a tactic that gradually emerged from

late 1915, it was designed to increase the chance of military

success by aiming to achieve and then consolidate a modest objective

as opposed to making a big breakthrough. The tactic employed a concentrated artillery barrage to

wreck the German trenches and fortifications followed by a rapid

infantry advance under an umbrella of shellfire (see

Creeping

Barrage) to seize a small sector of the defences (the bite)

and then hold it. The British reserves could then be

brought up under the shelter of further precision shelling to repel

the inevitable German counter attack. In this way progressive

chunks of the German defences could be eroded away leading to an

eventual breakthrough.

THE HINDENBURG LINE (TO THE GERMANS, THE SIEGFRIED LINE):

constructed by the German army on the Western Front during the

winter of 1916–1917, it eventually became a system of linked

fortified areas (not a continuous line of defence) running from the

North Sea to the area around Verdun in mid-France.

Faced with a substantial numerical inferiority and a dwindling

firepower advantage, the new German commanders Field Marshal von

Hindenburg and General Ludendorff shortened their lines (which

reduced their frontage by 30 miles, releasing 10 divisions of

infantrymen and 50 batteries of heavy artillery for the Reserves)

and installed concrete pillboxes armed with machine guns as the

start of an extended defensive system up to eight miles deep.

Based on a combination of firepower and counterattacks, the

Hindenburg Line resisted all Allied attacks in 1917 and was not

breached until late in 1918.

GERMAN RETREAT TO THE HINDENBURG LINE: Operation Alberich was

the codename of a German Army military operation in France during

1917. It was a planned withdrawal to new positions on the

shorter, more easily defended Hindenburg Line,

which took place between the 9th February and the 20th March 1917.

It eliminated the two salients which had been formed in 1916 during

the Battle of the Somme, between Arras and Saint-Quentin, and from

Saint-Quentin to Noyon. The British referred to it as the

German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line but the operation was a

strategic withdrawal rather than a retreat.

|

|

|

The PH Helmet. |

THE ANCRE: is a river in Picardy, France. It rises at

Miraumont, a hamlet near the town of Albert, and flows into the

Somme at Corbie.

BAPAUME: in 1916 Bapaume was one of the cities considered to

be strategic objectives by the allies in the framework of the Battle

of the Somme. The city was occupied by the Germans on the 26th

September 1914, then by the British on the 17th March 1917.

The Germans retook the city on the 24th March 1918 during their

Spring Offensive. The Second Battle of

Bapaume (21st August–3rd September 1918) was part of the second

phase of the Battle of Amiens. This British and Commonwealth

attack that was the turning point of the First World War on the

Western Front and the beginning of the Allies’

Hundred Days Offensive.

THE PH HELMET: was an early type of gas mask issued by the

British Army for protection against chlorine, phosgene and tear

gases. Rather than having a separate filter for removing the

toxic chemicals, it consisted of a gas-permeable hood worn over the

head which was treated with chemicals. The PH Helmet replaced

the earlier Tube Helmet in October 1915. Added hexamethylene

tetramine greatly improved protection against phosgene and added

protection against hydrocyanic acid. Around 14 million were

made and it remained in service until the end of the war by which

time it was relegated to second line use.

|

|

|

The Small-box

Respirator. |

THE SMALL-BOX RESPIRATOR: introduced in 1916, it was much

more sophisticated than earlier types. It consisted of a face

piece and a filter box, connected by a corrugated tube. The

small-box respirator was carried in a canvas bag, normally on the

soldier’s chest. In the event of a gas alarm, the soldier

fastened the respirator against his face, leaving the filter box in

the canvas bag. When the soldier inhaled, he drew air through the

filter box, where it was decontaminated before passing through the

corrugated tube and into the facemask.

THE CHILDERS REFORMS: restructured the infantry regiments of

the British Army. The reforms, undertaken by Secretary of

State for War Hugh Childers, were a continuation of the

earlier Cardwell Reforms. They came into effect on the 1st

July 1881.

The reorganisation was brought into effect by General Order 41/1881,

issued on the 1st May 1881, amended by G.O. 70/1881 dated the 1st

July, which created a network of multi-battalion regiments. In

England, Wales and Scotland, each regiment was to have two regular

or “line” battalions and two militia battalions. In Ireland,

there were to be two line and three militia battalions. This

was done by renaming the numbered regiments of foot and county

militia regiments. In addition the various corps of county

rifle volunteers were to be designated as volunteer battalions.

Each of these regiments was linked by headquarters location and

territorial name to its local “Regimental District”.

VADs: in 1909 the War Office issued the Scheme for the

Organisation of Voluntary Aid. Under this scheme the British

Red Cross were given the role supporting the Territorial Forces

Medical Service in the event of war. They did this by

recruiting volunteers, called “voluntary aid detachment members”,

who came to be known simply as ‘VADs’ (the term also applied to

voluntary aid detechments). VADs were trained in first aid and

nursing, and proved invaluable during both world wars.

THE RACE TO THE SEA: following

the September battles of the Marne and Aisne, the Race to the Sea

was conducted by Allied and German forces from September to November

1914. It was the last mobile phase of the war on the Western

Front and ended with the onset of trench warfare that would continue

until the German Spring Offensive of March 1918.

In the Race to the Sea, both sides attempted to outflank their

opponent by pressing their attacks increasingly further north in

Flanders, the only flank open for manoeuvre, but all attempts were

thwarted as each side dug in and prepared effective trench defences.

Once the trench lines had reached the the coast, the focus switched

to the opposite direction all the way to the (neutral) Swiss border,

some 400 miles in length. Deemed something of a draw by the

close of November, each side then settled down to protracted trench

warfare punctuated by periodic concerted attempts (such as the

Somme, the 2nd Aisne and Passchendaele) to break through the enemy line.

THE WESTERN FRONT: the main theatre of war during the First

World War. Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, the

German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and

Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial

regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically

turned with the Battle of the Marne (6th–10th September 1914).

The Western Front in 1916.

Following the Race to the Sea (below), both sides dug in along a

meandering line of fortified trenches, stretching some 400 miles

from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier with France. Except

during early 1917 and in 1918, the Western Front changed little.

CAVALRY IN THE MIDDLE EASTERN WAR: General Chauvel, Commander of

the British Desert Mounted Column, and his 33,000 strong cavalry,

defeated two Turkish armies from Cairo to Damascus and beyond during

the Middle East War (1916-1918). He and his horsemen then

swept across the Jordan Valley and helped T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia)

and company put a third Turkish army asunder. The type of

horse Chauvel used was the Waler, a term derived from New South

Wales when the breed was scattered and developed all over Australia.

The Waler stood from 12 to 19 hands, usually in the range 14 to 16

hands, and weighed between 300kg and 750kg, sometimes more.

They were originally sired by English thoroughbreds from breeding

mares, which were often partly draught horse, and were versatile,

hardy animals that could withstand the rigours of Australia’s vast,

semi-desert regions.

MALARIA: an unexpected adversary in the First World War was malaria.

It attacked all combatant armies with adverse consequences for many

troops. Statistics for British and Dominion troops serving in

Egypt and Palestine in the period 1914-1918 show that out some

40,000 cases of malaria, 854 (2.13%) were fatal (Casualties and Medical Statistics of the Great War.

1931, London: HMSO).

When bitten by a malaria-infected mosquito, the parasites that cause

malaria are released into the person’s blood infecting the liver

cells. The parasite reproduces in the liver cells, which then

burst open to allow thousands of new parasites to enter the

bloodstream and infect red blood cells.

Malaria can affect different people in different ways, and no two

infections are identical. So while malaria kills, it can cause

death in different ways (and these conditions can strike in

combination, further reducing the survival prospects of sufferers):

One serious condition is called cerebral malaria,

caused when malaria parasites stick in the blood vessels in the

brain leading to deep coma, seizures and death. This affects

really young kids the most, usually when they are still babies and

is a very serious illness.

Another problem during malaria infection is severe anemia,

which is due to not having enough red blood cells to carry oxygen

around the body. Malaria infection causes the destruction of

red blood cells in the body, and also interferes with the body’s

ability to make new red blood cells. So the body becomes

starved of oxygen which can lead to death.

Malaria infection can also damage the lungs, and cause massive

breathing difficulties. Patients affected this way often take

huge deep breaths, almost like they are so hungry for air they can’t

get enough in and out of their lungs fast enough. This is

called respiratory distress, and one is the

worst signs for malaria patients.

It is no coincidence that both of the discoverers of the cause

of malaria and the carrier of the disease were military

surgeons serving in tropical countries, for armies have always been

plagued by the disease. In 1880, Charles Laveran, a French

army surgeon stationed in Algeria, was the first to notice parasites

in the blood of a patient suffering from malaria, but it was Ronald

Ross, a British Army surgeon working in Calcutta in 1897, who

discovered the role of the malaria carrying Anopheles mosquito in

spreading the disease.

|

|

|

Charles Louis Alphonse

Laveran

(1845-1922) |

Sir Ronald Ross FRS

(1857-1932) |

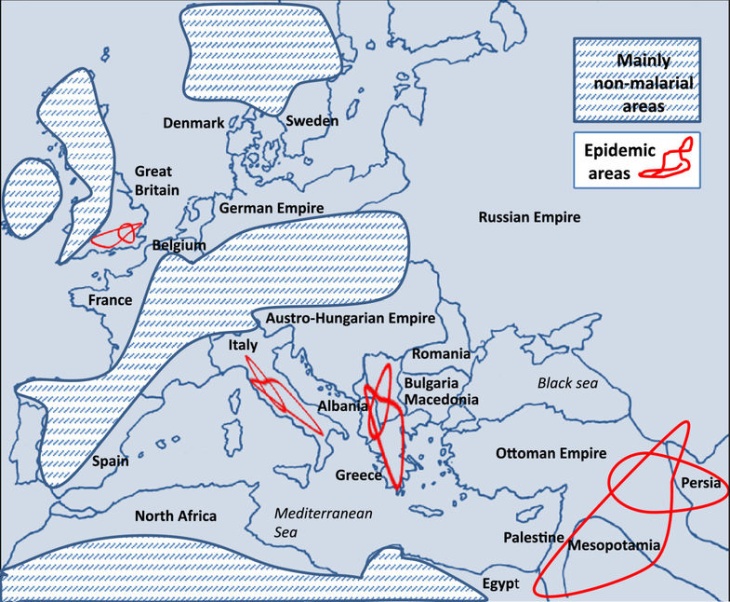

Distribution of malaria transmission in

theatres of the First World War.

During the First World War the only effective treatment for malaria

was the drug quinine, an extract from the bark of a South American

Cinchona Tree. Soldiers thought to be at risk

in malarious countries received a systematic treatment of quinine,

but the drug could have side effects such as tinnitus (a persistent

ringing in the ears) which many found difficult to tolerate, whilst

other distressing side effects were giddiness, blurred vision,

nausea, tremors and depression.

RHEUMATIC FEVER (RF): is an

inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and

brain. Although its exact cause is unknown, the disease

usually follows the contraction of a throat infection caused by a

member of the Group A streptococcus bacteria (called strep throat).

Penicillin remains the most effective treatment for RF (although

this drug was not widely available for military use until 1944).

The long-term prognosis of an RF patient depends primarily on

whether he or she develops carditis (inflammation of the heart

muscle) the only manifestation of RF that can have permanent

effects. Those patients with mild or no carditis have an

excellent prognosis. Those with more severe carditis have a

risk of heart failure, as well as a risk of future heart problems

(which today may lead to the need for valve replacement surgery).

TRENCH FOOT: is a medical

condition caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to damp,

unsanitary, and cold conditions. The foot become numb, changes

colour, swells and starts to smell due to damage to the skin, blood

vessels and nerves. It can take three to six months to recover

fully, and prompt treatment is essential to prevent gangrene and

possible foot amputation.

Trench foot can be prevented by keeping the feet clean, warm, and

dry. It was also discovered in World War I that a key

preventive measure was regular foot inspections; soldiers would be

paired and each made responsible for the feet of the other, and they

would generally apply whale oil to prevent trench foot. If

left to their own devices, soldiers might neglect to take off their

own boots and socks to dry their feet each day, but if it were the

responsibility of another, this became less likely. Later on

in the war, instances of trench foot began to decrease, probably due

to the introduction of the aforementioned measures; of wooden

duckboards to cover the muddy, wet, cold ground of the trenches; and

of the increased practice of troop rotation, which kept soldiers

from prolonged time at the front.

WAR DIARY: is a regularly

updated official record kept by military units of their activities

during wartime. Their purpose is to record information which

can later be used by the military to improve its training and

tactics as well as to generate a detailed record of units’

activities for future use by historians.

The British Army first required its units to keep war diaries in

1907 as a means of preventing its mistakes of the Second Boer War

from being repeated. The First World War diaries − many of

which are held in the

National Archives and are available (for a fee) to download −

contain a wealth of information that has proved of far greater

interest than the army could ever have predicted. They provide

unrivalled insight into daily events on the front line, and are full

of fascinating detail about the decisions that were made and the

activities that resulted from them. While war diaries focus on

the administration and operations of the units they cover, they

follow no absolutely consistent format. Some record little

more than daily losses and map references whilst others are more

descriptive, with daily reports on operations, intelligence

summaries and other material. Diaries sometimes contain

information about particular people, including acts of gallantry,

but they are unit diaries, not personal diaries. That said,

officers that join or leave the unit or feature among its casualties

are are usually named whereas other ranks appear as totals (e.g.

42 ORs killed).

ARTILLERY: is a class of large

military weapons built to fire munitions far beyond the range and

power of infantry's small arms. Artillery is arguably the most

lethal form of land-based armament currently employed, and has been

since at least the early Industrial Revolution. The majority of

combat deaths in the Napoleonic Wars, World War I, and World War II

were caused by artillery.

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the

Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as “The Gunners”, is

the artillery arm of the British Army. On the 1st July 1899,

the Royal Artillery was divided into three groups: the

Royal Horse Artillery (RHA) and Royal Field Artillery (RFA) comprised

one group, while the Coastal Defence, Mountain, Siege and Heavy

artillery were split off into another group named the Royal

Garrison Artillery (RGA). The third group continued to be

titled simply the Royal Artillery and was responsible for

ammunition storage and supply. During the First World War

there was a massive expanse in artillery, and by 1917 there were

1,769 batteries in over 400 brigades totalling 548,000 men.

An RGA battery of 9.2 inch howitzers

with ammunition.

SIEGE BATTERY: the Royal

Garrison Artillery (RGA) became the ‘technical’ branch of the Royal Artillery

and was responsible for much of the professionalization of technical

gunnery that was to occur during the First World War. It was

armed with heavy, large calibre guns and howitzers that were

positioned some way behind the front line and had immense

destructive power. These sent large calibre high explosive

shells in high trajectory. The usual armaments were 6

inch, 8 inch and 9.2 inch howitzers, although some had huge railway-

or road-mounted 12 inch howitzers. As British artillery

tactics developed, Siege Batteries (of the RGA) were most

often employed in destroying or neutralising the enemy artillery, as

well as putting destructive fire down on strong-points, dumps,

store, roads and railways behind enemy lines.

Heavy and Siege Batteries were organised into Heavy Artillery

Brigades, a title that was altered to Heavy Artillery Groups

(HAGs) in April 1916, but reverted to Brigades in December 1917.

An RFA 18-pounder battery on the move.

The RFA, the

largest branch of the artillery, provided howitzers and medium

artillery near the front line. The Ordnance QF 18-pounder

(shown above), or simply 18-pounder, was the standard British field

gun of the First World War-era and was produced in large numbers.

It was used by British Forces in all the main theatres. Its

calibre (84 mm) and shell weight were greater than those of the

equivalent field guns in French (75 mm) and German (77 mm) service.

It was generally horse drawn until mechanisation in the 1930s.

|