|

|

The Dancersend Waterworks. In its later days

the pumping engine’s cooling pond was used by water company staff as a

swimming pool. |

FOREWORD

I enjoy reading old editions of the local press, for the rags of

bygone days contained much more meat than one finds amongst today’s

diet of local gossip. For instance, what an interesting read

was the account of the first amputation at the Bucks Infirmary in

which an

anaesthetic was employed. [February, 1847] Although the patient might later

have succumbed to gangrene, the administration of ether did at least prevent

death from shock.

The grisly spectacle of public hangings was also well covered, such as

that of the pair who murdered the

Sparrows Herne Turnpike gate keepers

for their meagre takings. [March 1823] Thousands turned up to witness the event which took place in front of the Aylesbury County Hall.

And when Queen Victoria stopped briefly at Tring station on her

journey to Wolverton along the recently opened London & Birmingham

Railway, [November 1844] our local news hound was there to record the event in which

a chorus of local children was assembled in the pouring rain to

sing her the national anthem.

A less happy newspaper report that stuck in my mind was of cholera visiting

a

local village (Ivinghoe) during the 1867 epidemic. In the course of a few

hours it wiped out most members of a family that had fallen victim to

it . . . .

“. . . . the

cholera had made its appearance in the last few days. Japhet Janes,

aged 40, was first attacked on the 9th inst., but he is getting

better. His son Thomas was taken on the 10th. inst., and died the

same night. His wife was attacked on the 10th inst., and died also

the same night, together with two of his children, one of whom died

on the 11th inst. Two other of his children were also taken ill, and

a woman named Turney, who was engaged in nursing the above-named

patients, was attacked with cholera and died in 12 hours. On Sunday

a man who gave evidence on the previous day at the Ivinghoe Petty

Sessions was taken ill, and died in a few hours.”

Thankfully, cholera and typhoid are strangers to us

today, but not to our Victorian forebears who had yet to receive a

plentiful supply of uncontaminated drinking water. So when the

Secretary of our local history society asked whether I would look

into the history of Tring’s public water supply, the invitation provided a good

excuse to root among the back issues of the local press to see what

gems on the subject might be unearthed.

The account that follows ― which for the most part comes from old

editions of the Bucks Herald

― is about the

early history of sanitation in Tring. It covers the period

1865 to 1905, during which uncontaminated drinking water became

publicly available (although many preferred to continue drinking well water,

sometimes with dire consequences) and a workable sewage disposal system

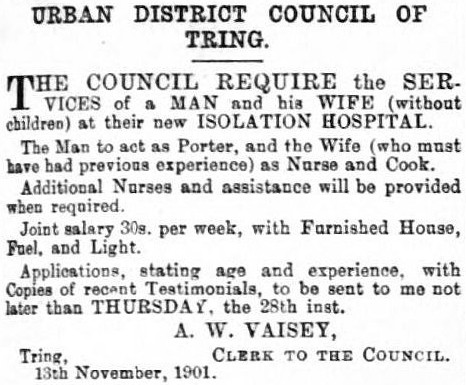

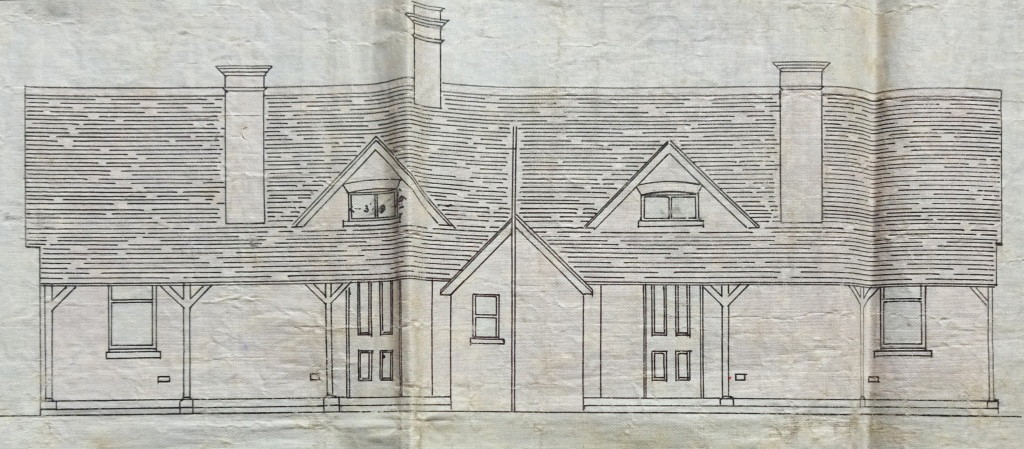

was brought into operation. An isolation hospital was built ― for this was

an age in which serious infectious disease was commonplace ― and

arrangements were made for the safe burial of the dead.

Although at first glance these topics might seem unconnected,

the theme that flows through them is that of serious disease and its

prevention and control within the community ― public health.

My thanks go to my friend and sometime co-author, Wendy Austin, for

her assistance with research, to Pat Roberts for access to her

papers on the Tring Isolation Hospital and for an interesting

guided tour of the former site ― now attractive residential

accommodation, tastefully landscaped ― and to local historian Mike Bass for the

use of his photographs of the Tring Nursing Home.

Ian Petticrew

October 2016

――――――――――――――

CONTENTS

CLEAN DRINKING WATER

SEWAGE DISPOSAL

MANAGEMENT OF INFECTIOUS DISEASE

BURIAL OF THE DEAD

DISTRICT NURSING

PREVENTIVE HEALTHCARE

APPENDIX I.: WATERBORNE DISEASE

APPENDIX II.: A MODIFIED FORM OF PRIVY

APPENDIX III.: THE SEWAGE SCHEME – LOCAL GOVERNMENT

INQUIRY

APPENDIX IV.: THE RECENT TYPHOID OUTBREAK

(Dr. William Gruggen, Obit.)

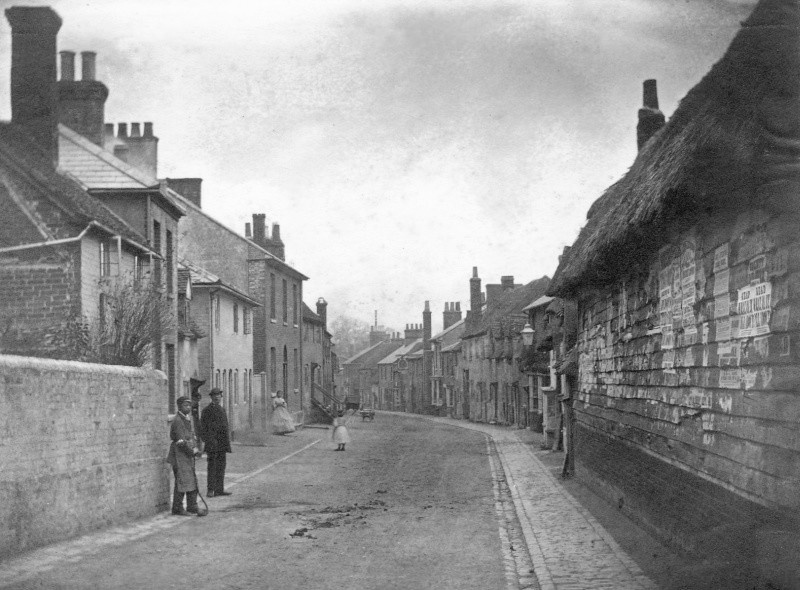

APPENDIX V.: SURREY PLACE IN 1899

APPENDIX VI.: A NEW CEMETERY FOR TRING

APPENDIX

VII.: DUTIES OF THE MEDICAL OFFICER OF HEALTH

APPENDIX VIII.: THE CHESHAM PLAGUE

APPENDIX IX.: PUBLIC HEALTH IN CHESHAM

APPENDIX X.:

THE FEVER

HOSPITAL, ALDBURY

――――――――――――――

CLEAN DRINKING WATER

Safe and readily available water is of great

importance for public health, whether it is used for drinking,

domestic use, food production or recreational purposes.

World Health Organisation.

“The half-yearly shareholders’ meeting of

the Chiltern Hills Spring Water Company, at Aylesbury, on Monday,

occasioned several farewells and reminiscences on the part of the

Directors and officers of the Company. It was the last meeting

of the Company, after 81 years existence, before it became merged

with the Bucks Water Board . . . . the Company was formed about 80

years ago by a small band of men who felt that the necessity for a

supply of pure water to the town was very urgent.”

Bucks Herald, 5th

October 1946.

THE FIRST ATTEMPTS TO SET UP A WATER COMPANY

Clean drinking water, drawn from deep wells in the Chiltern Hills at

Dancersend [31], was first piped to Tring in 1870. However, the

history of this important step in promoting public health began at

Aylesbury some years earlier.

The first attempt to establish a water company was in

1853. A scheme was announced to draw water from

Broughton Brook at a point adjacent to the canal ― the alternative

of piping water from the Chiltern Hills having been considered too

expensive ― then to pump it into a water tower “sufficiently high to

command the upper stories of all houses in the town”. The

estimated cost of the scheme was put at £8,000, added to which would

be a further charge of 20 to 30 shillings a house for connecting the

supply. It is interesting to note that at this time the

question of ‘water quality’ was confined to its hardness; that of

contamination had yet to appear on the agenda.

In an age before public infrastructure projects were funded centrally, schemes such as the creation of a water utility had to be

financed privately. The outcome was that if a scheme’s promoters

failed to raise sufficient capital, it was abandoned ― and such was

the fate of the first attempt to supply running water to Aylesbury.

The next attempt to set up a water company came in 1858:

“We understand that the long-talked-of

Water Company is about to be established in this town, there being

at present nearly £2,000 in shares subscribe, the proposed capital

being £7,000. Looking at the scheme in a mercantile sense,

doubtless it will prove a profitable investment of capital; and, in

a sanitary point of view, its importance to the town of Aylesbury

will be incalculable.”

Bucks Herald,

8th May 1858.

. . . . so was announced the proposed Aylesbury Water Company, and

while the notice draws the attention of prospective investors to the

scheme’s scope for profit, it also emphasises its “incalculable”

contribution to the town’s sanitation ― it appears that news

of Dr. John Snow’s

work on the cause of cholera had reached Aylesbury, for the

notorious Soho pump was by no means alone in spreading that

potentially fatal disease among the population it served (APPENDIX I). Writing in 1868, Dr. Charles Hooper, an Aylesbury

general practitioner, had this to say about that other dread

waterborne disease, typhoid, and the town’s wells:

“During the last epidemic of typhoid fever

here, all those patients suffering from it who first came under my

notice had a special affection for the Kingsbury pump water.

The water on their own premises tasting disagreeably, they had all

been in the habit of imbibing freely from that source, and I

attributed the attacks to the impurity of that well . . . . It is my

firm conviction that there is scarcely a well in the town of

Aylesbury so situated as to be entirely free from the danger of

contamination by infiltration of sewage.”

The 1858 scheme appears to have been a reappearance of that from

five years earlier.

Based on their previous experience, the main concern of those

who gathered at the White Hart Hotel to consider the plan was whether sufficient capital

could be raised to fund the project, and whether sufficient customers

would then connect to the supply to yield a reasonable return on their

investment. It was therefore agreed that the town would first

be canvassed to estimate both the number of customers for a supply

of “pure and wholesome water” and the number of shares that

would likely to be taken up by investors, for, “unless a

sufficient number of shares are taken, the proposed undertaking must

fall to the ground”. When the townsfolk met a week later

to learn the outcome, they were informed that only £3,000 of the

estimated £7,000 requirement had been pledged. A further

effort was made to enrol potential investors, but this too seems

to have failed. For the time being, nothing more is heard of

this particular undertaking.

――――――――――――――

THE CHILTERN HILLS WATERWORKS COMPANY

Towards the end of 1863, statutory announcements appeared in the

Aylesbury press giving notice that two undertakings, the ‘Aylesbury

Waterworks’ and the ‘Chiltern Hills Water Works’, each intended to

apply to Parliament for leave to bring in a Bill to incorporate the

respective companies, their aim being to supply Aylesbury with

water.

The Aylesbury Waterworks Company planned to use as their source the

Bear Brook and to construct their waterworks “on the north side

of the road known as Dropshort Lane, and on the south side of the

corn mill known as Walton Mill.” The company also planned

to construct a reservoir and filter beds, and install steam-powered

pumping equipment.

The competing scheme was more ambitious. The promoters of The

Chiltern Hills Waterworks Company aimed to supply water, not just to

Aylesbury, but to surrounding parishes. While the statutory

notice fails to identify the source of the supply, it does state

that water was to be stored in a “service reservoir” to be

built in a field adjacent to the Sparrows Herne Turnpike Road [1] “on

or near the summit or highest point of Tring Hill”. [2]

Water from the reservoir was to be piped along the route of the

turnpike to Aylesbury to terminate “. . . . in the street known

as New-road, at or near the Market-place, opposite to the house

known by the sign of the Crown Inn . . . .” from where the mains

would distribute the water around the town.

A private Act of the type applied for would have given the company

who obtained it various legal rights not generally available to the

community at large, the most notable being the right to buy land and

property by compulsory purchase ― or as the statutory notice put it:

“To purchase by compulsion or agreement and

otherwise, take or lease and take grants or easements over lands,

houses, water rights of water and other property for the purpose of

the undertaking, and to levy rates and charges in respect of water

supplied by the Company.”

However, obtaining a private Act for an infrastructure project [3]

was (and remains) an expensive business, particularly if, as is

usual, objections are raised by parties opposed to the Bill.

Such objections are presented during the quasi-judicial committee

hearings in which the Bill is examined in detail, when each faction

generally employs barristers to state their case for or against

the Bill most forcibly. In this instance it was

unlikely that Parliament would approve both waterworks schemes, so

rather than spend a potentially large sum in fruitless legal fees in

a contest, the Board of the Aylesbury Waterworks Company withdrew

their application:

“It will be satisfactory for the

inhabitants of this town to learn that the promoters of the rival

projects for supplying Aylesbury with water have come to an amicable

agreement, by which the Chiltern Hills promoters are pledged to seek

for parliamentary sanction to their scheme by every means in their

power, and in which effort they will be assisted with evidence, &c.

(if necessary), by the promoters of the Aylesbury scheme, whose

engineer (Mr. R. J. Ward, Victoria Street, Westminster), has had

considerable experience in such matters, and who, as we understand,

only consented to withdraw his plan from the consideration of

Parliament, from a desire not to contest a matter of such importance

to the town of Aylesbury.”

The Bucks Advertiser and Aylesbury

News, 28th November 1863.

Withdrawal of the Aylesbury scheme left the field clear for the

Chiltern Hills Waterworks Company, but petitions against their Bill

were then lodged by The Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway [4] and the

Grand Junction Canal companies. The nature of these petitions

is unknown, but the outcome was that the Waterworks Company withdrew

their Bill, perhaps foreseeing the high cost involved in fighting

off these opposing parties. How the company managed to

construct their pipeline and distribution mains without the

underpinning authority of an Act of Parliament is unclear; it must

be assumed that the Company reached amicable agreements

with the Sparrows Herne Turnpike Trust, the Aylesbury Local Board of

Health [5] and any other parties affected by the Company in laying

their pipeline.

Despite the parliamentary setback, by April 1864 the Bucks Herald

was able to report that the directors and their consulting civil

engineer [6] had visited the Caterham Waterworks near Reigate where,

as in the Chilterns, water was pumped from wells sunk deep in the

underlying chalk. The extracted water was then softened using

Clarke’s process [7] before being released into the mains. The

article concludes by stating that “the works of the Company near

the summit of the Chiltern Hills are progressing most

satisfactorily. A large supply of water has been already found

at a depth of not more than 180 feet”. [8]

It appears that up to 1863 the Company had been prospecting for

water. A good supply was located in the aquifer at a site in

the Chilterns at Dancersend, on a steep hill known locally as The Crong, about 1½ miles southwest of Tring. This location was

sufficiently high to provide Aylesbury and its surrounding area with

water by gravity, while the site had the added advantage of lying

adjacent to chalk pits from which lime for water softening (by

Clarke’s process) could be obtained. [9]

“The works were visited by the Rivers

Pollution Commission, and were then softening 230,000 gallons a day

by means of 18,400 gallons of lime water, at a cost for lime and

labour of 27 shillings per million gallons, reducing the total solid

impurity from 28.60 [parts per 100,000] to 8.18, and the hardness from 26.3 to 3.2

without impairing its brilliancy, transparency, and palatability; it

has a normal temperature of 51° F.”

The Water Supply of England and

Wales, Charles Rance (1882)

The site having been agreed on, construction of the works and

reservoir commenced:

“We are happy to state that the

construction of the reservoir between Aston Clinton and Tring, for

the supply of the town with water, is progressing with great

rapidity, about 150 men being employed on the works. The water

has been found at a depth of 187 feet, some 30 feet nearer the

surface than was expected. A second shaft has now been sunk,

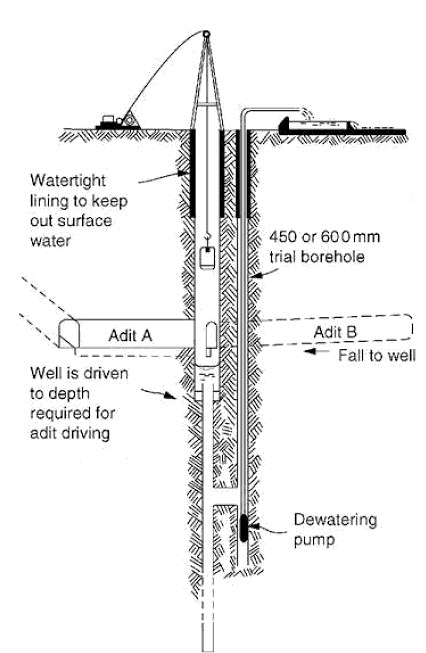

and as soon as this has been completed adits

[10] will be formed in

various directions to collect a quantity of water sufficient for the

requirements of the town. The purity of this water is

unquestionable, and after being softened by a patent process

[Clarke’s process – see fn. 7] it can

be supplied in any quantity at a level of 200 feet above the highest

part of the town. The company is now formed under the limited

liability act, it having been deemed advisable to abandon the

special Act of Parliament in consequence of the expense; and we

understand that the whole of the shares have been taken up.”

The Bucks Advertiser and Aylesbury

News, 26th March 1864.

Design was placed in the hands of George Devey (1820-86), an

architect usually associated with the design of country houses and

their estates, especially for the Rothschild banking family who

provided him with a steady stream of commissions. The

waterworks he designed comprised a walled courtyard with an attached

watchman’s lodge, a store, stables, an engine house with cooling

pond (used to condense the exhaust steam from the pumping engine),

two lime tanks, and a pair of depositing reservoirs (softening

tanks). In addition, a pair of semi-detached two-storey

workmen’s cottages was built at the north-eastern end of the site.

A date plaque on the wall of the main building reads 1866, although

the etched glass engraving on the main doors reads 1867, the year in

which the Works commenced business.

|

|

The Dancersend Waterworks as it

exists today. |

| Below: pumping engine and boiler. |

Early picture of the waterworks

showing the pumping engine chimney, long since removed.

|

The history of ownership in the waterworks’ early years is unclear.

The Rothschild Estate Books for the period 1851-79 (held in the

Rothschild Archive in London) list the purchases and tenants for the

Rothschild estates in the Vale of Aylesbury. Among the purchases is

an entry that reads “Dancersend, bought from Mr. Parrott in

1862 and sold to the Waterworks Company in 1866”. The

published report of the Company’s first Ordinary General Meeting,

held on 17th May 1866, states that the sum of £6,500 was paid as “Amount

agreed upon for the purchase of land, with the wells, reservoirs,

pits, pipes, buildings, &c., up to 19th of May 1865, the date of

incorporation of the company . . . .” Why, in 1862, the

Rothschild family bought a site on which to erect a waterworks is a

matter of conjecture, but it might have had more to do with

supplying water to the family’s property in the Vale of Aylesbury

than to the town itself.

Circa 1851, Sir Anthony de Rothschild (1810-76) bought an estate at

Aston Clinton. He commissioned the architect George Henry

Stokes to design his mansion (demolished in 1956) and

grounds, with George Devey later designing the park gates and

various estate cottages. It is possible that the Dancersend

waterworks was conceived originally to supply this estate ― which

lay mid-way between Dancersend and Aylesbury ― with running water.

Sir Anthony certainly made effective use of the product when it

became available:

“The other day I went over to see the

sanitary improvements carried out by Sir Anthony Rothschild in his

cottages at Aston Clinton and adjoining villages. I found that

in each cottage, water brought from the Chiltern Hills had been laid

on. It is not everyone who can, in this particular, follow the

example of Sir Anthony, or who, if willing, has a public water works

so near at hand. I have mentioned it, because on inquiry of

the cottagers, I found that it was a boon highly prized. One

man remarked that he did not know what they should now do without

it. The wife joined in, and said, ‘Yes, sir, it is a great

convenience, and it saves us so much in soap.’ Indeed, who can

estimate the value to these poor people of an abundant and constant

supply of the purest water for drinking, cooking, and washing, or ―

what is also important ― its value for carrying away a good deal of

filth which without it would be sure to collect in and about the

dwellings.”

The Farmer’s Magazine, Volume

76, 1874.

――――――――――――――

THE CHILTERN HILLS SPRING WATER COMPANY LIMITED (CHSWC)

The CHSWC was incorporated in May 1865 with a capital of £21,000.

In the following year it acquired the assets of the Chiltern Hills

Waterworks Company from the Rothschild family, which perhaps

explains why George Devey, the Rothschild’s ‘house architect’ at the

time, designed the Works. The question now arose of how to

finance the new company. In April 1865 a prospectus was

published inviting the public to apply for £10 shares in the

Company, which . . . .

“. . .

. has been formed for the purpose of obtaining for the Town of

Aylesbury and adjacent Parishes an ample supply of the finest Spring

Water from the chalk formation above the Village of Aston Clinton.

The Supply Tanks will be placed at an altitude of 650 feet above the

level of the sea, and will enable the Company to supply the Town of

Aylesbury and adjacent Parishes, including Tring, with a continuous

stream of the purest water by gravitation.”

Company prospectus, Bucks Herald,

1st April 1865.

The Company’s first Directors were: Edward Robert Baynes, of

Aylesbury; William Bell of Bierton; George Lathom Browne, of London;

Herbert Astley Paston Cooper, of Aylesbury; Rowland Dickens, of

Aylesbury; John Kersley Fowler, of Aylesbury; Henry Gurney, of

Aylesbury; James James, of Aylesbury; and Joseph Parrott, of

Aylesbury. There were also five members of the Rothschild

family with an interest in the concern and who, in later years, gave public-spirited assistance to

the Company by taking up a large number of shares and advancing

loans on favourable terms.

Unlike earlier attempts to establish a water company in Aylesbury,

the new undertaking appears to have made a good start financially,

for the directors decided that only 600 of its 2,100 shares would be

offered to the public with the subscription list being closed four

weeks after the offer. No doubt the candid description they

gave of the quality of the water then being consumed in the Town

encouraged potential investors to reach for their cheque books:

“A large proportion of the population

derive their supply from the Mill-stream, which gathers sewage and

other impurities on its passage through the Country intervening

between the Chiltern Hills and Aylesbury. The water thus

vitiated is unfit for ordinary used, and is moreover, from its

extreme hardness, equally unfitted for culinary and other domestic

purposes; but bad and unwholesome as it is, the cost is more than

ten times as great to the consumer than that which the present

Company can furnish water amongst the purest to be found in

England.”

Company prospectus, Bucks Herald,

1st April 1865.

The prospectus went on to describe the waterworks and how the supply

was to reach Aylesbury:

“To remedy these [above

mentioned] evils the Company has sunk deep

Wells in the chalk, with underground Tanks, where they can pump,

from day to day, a supply of water greater by far than a much larger

population can possibly require. This water will flow through

pipes laid along the line of the Turnpike Road, and after supplying

the Township of Aston Clinton, with the Farms and Residences on the

road, will be distributed through every part of Aylesbury and

Walton.”

Company prospectus, Bucks Herald,

1st April 1865.

At this stage the Company’s consulting civil engineer,

Samuel Homersham,

estimated the cost of the project to completion at £17,200:

“The cost of the works necessary for

supplying the town of Aylesbury, and including all the districts

named in the Bill, exclusive, of course, of the surveys, level,

Parliamentary expenses, land and compensations, and engineer’s

charges, I estimate approximately as follows:”

|

Wells, borehole, adits to yield 220,000 gallons per day |

£2,600 |

|

Pumping engines, pumps, boilers |

£2,000 |

|

Engine-house, boiler-house, boiler sealing, and chimney |

£1,100 |

|

Foundations for pumps and girders, &c., in well |

£300 |

|

Depositing reservoirs and service reservoirs |

£2,100 |

|

Limewater reservoir, lime house, &c. |

£350 |

|

Whiting pits |

£140 |

|

Roads, Boundary walls, &c. |

£300 |

|

Main pipes, 8 inches internal diameter, from service

reservoir to Aylesbury, laid in ground about 7 miles

long, at £830 per mile |

£5,810 |

|

Screw cocks, &c., for main, &c. |

£300 |

|

Distributing pipes in Aylesbury |

£2,200 |

| |

|

|

TOTAL |

£17,200 |

(At the Company’s

half-yearly meeting, held in March 1885, the final cost of the work

was stated to have been £30,000.)

In the following

month the company placed advertisements in the Bucks Herald

inviting tenders from contractors for building work at Dancersend,

the outline specification suggesting that construction of the Works

had already commenced, but was not far advanced:

“. . . . the

engineer was instructed to issue advertisements for tenders for the

necessary engines and pumping apparatus, and for the erection of a

pump house and other necessary works. The pipes, we

understand, will be laid from the engine-house across Sir A[nthony]

de Rothschild’s property, entering the road at the back of Mr.

Jenney’s house near Buckland Common; the pipes will then be carried

along the Tring-road to Aylesbury. The wells and pumps are of

sufficient capacity to supply the town of Tring, should it at any

future time be found desirable . . . . It may be observed, for the

benefit of intending shareholders, that water companies in all parts

of the country, when well managed, have usually been found to yield

a better return than any other undertaking of a similar nature.”

The Bucks Advertiser and Aylesbury News,

26th March 1864.

――――――――――――――

THE

FIRST

GENERAL

MEETING

OF THE

CHSWC (19th MAY

1866)

So far as funding

was concerned the new company initially had an optimistic start,

with the share allocation available to the general public being

limited to 600 £10 shares. But the cost of acquiring the

Chiltern Hills Waterworks Company (£6,500) together with that of

ongoing construction was beginning to make the company’s financial

position look distinctly shaky; on the other hand, the advancing

cholera epidemic was again focusing attention on the need for clean

drinking water. This from the report of the first general

meeting:

Calls on allotted shares together with other income had raised

£11,327 12s 3d, of which all but £262 2s 9d had been spent.

The Secretary reported that shares of only £15,560 had so far been

subscribed (of the £21,000 estimated capital).

“The Chairman urged every shareholder to solicit his

neighbours to take shares, as that would be a very great assistance,

not only so far as the supply of money was concerned, but also for

the increase of interest in those who were to be benefited by a

supply of pure water”.

Contracts for all the necessary works had been let and work was

progressing rapidly towards completion. The engine house was

complete, but the engine and pumping gear had yet to be installed.

Pipe-work had been laid from the Works as far as the Tring to

Aylesbury road, about a mile in distance leaving a further six miles

to complete. This section had been the most difficult on the

route to construct, with trenches in which to lay the water pipes

having to be excavated to a depth of 40 to 50 feet.

The

Chairman stated that “The cholera had

already made its appearance at Liverpool, and medical men said it

would probably rage again throughout the country during the summer;

and he was quite certain that all who had studied sanitary measures

would see that the best mode of preventing the introduction of that

disease was by seeing that an early supply of good water was

effected”.

As for the

Chairman’s

warning of approaching cholera, in the following

year, at Ivinghoe . . . .

. . . . the cholera had made its appearance

in the last few days. Japhet Janes, aged 40, was first

attacked on the 9th inst., but he is getting better. His son

Thomas was taken on the 10th. inst., and died the same night.

His wife was attacked on the 10th inst., and died also the same

night, together with two of his children, one of whom died on the

11th inst. Two other of his children were also taken ill, and

a woman named Turney, who was engaged in nursing the above-named

patients, was attacked with cholera and died in 12 hours. On

Sunday a man who gave evidence on the previous day at the Ivinghoe

Petty Sessions was taken ill, and died in a few hours.

[11]

Northampton Mercury,

22nd September 1867.

――――――――――――――

THE

PIPELINE

REACHES

AYLESBURY

By the time of

the General Meeting of June 1867, the pipeline had still to

reach Aylesbury although the project was now “approaching its

completion”. One reason given for the delay was work

outstanding by James Kay, builder of the pumping engine to be

installed at Dancersend. Then, in September:

“We are pleased

to note that the mains of the Chiltern Hills Spring Water Company

have been laid down in the principal parts of this town, and there

is every reason to expect that in a very short time the majority of

the houses in Aylesbury will be supplied with wholesome water.

In many parts of the Town at the present time the water is so bad

that people refrain from drinking it until it has been boiled, and

very wisely to, for there is no doubt that the unwholesome water is

the primary cause of much illness in the town. The fire plugs

[fire hydrants]

have been fixed, and on Wednesday afternoon a large number of the

gentry and tradesmen of the town, and the directors, assembled in

the market square to witness an experiment with one of the fire

plugs. Among those present we noticed the two representatives of

the borough, S. G. Smith Esq., and N. M. de Rothschild, Esq. A hose

was fixed, and, under the direction of Mr. Boltbee, the manager, the

water was turned on. The force with which the water escaped was

tremendous and it was more than three men could do to hold it

steady, and much amusement was caused by the directors and others

getting wet. The water was thrown higher than the County Hall, so

that in case of fire these plugs would be of great assistance.”

Bucks Herald, 21st September 1867.

The water is turned on at Aylesbury.

In 1873 Samuel Homersham wrote a description of

the water supply system. It

is worth repeating most of what he had to say to illustrate the care he had taken to ensure that Aylesbury

received a supply of running water in the face of

inevitable breakdowns at the Works:

“There are two

boilers, two pumping engines, and two sets of pumps at the Company’s

works at Dancersend, to raise the water from the wells, and, so

arranged, that the two pumps, boilers and the two engines, with

their two sets of pumps, can be worked together, or either of the

boilers, engines, and sets of pumps, can be worked singly. This

arrangement admits of one boiler, engine, and set of pumps being

able to be repaired, while the other boiler, engine and set of pumps

are at work. The two engines, with the two sets of pumps, when

working together, are capable of raising more than four hundred

thousand gallons of water in twelve hours; and one engine, with one

set of pumps, in the same time, is capable of raising half this

quantity, or, in twenty-four hours, more than four hundred thousand

gallons of water.

Judging from the

amount of last year’s

[1872]

income, at present the Company must be disposing of little more then

one-fourth of the last named quantity, or, on the average of the

year, about one hundred and ten thousand gallons per day.

Therefore, one engine, and one set of pumps, when working only seven

or eight hours per day, is capable of supplying the present demand;

or the two engines and the two sets of pumps, working together,

would do so in only one-half the time, or in from three and a half

hours per day.

Again, the

softening and the service reservoirs are constructed in duplicate,

and so arranged that two can be used together, or can be used

separately as required.

Indeed,

notwithstanding the works are most solidly constructed, so that the

minimum outlay for repairs may be looked for, yet ample provision

has everywhere been made to enable any repairs that could be

required to be properly, readily, and quickly executed, without

danger of interrupting the continuous supply to the consumers.

With respect to

the engines and boilers, I may state that the steam power necessary

to raise the water to the height necessary to obtain pressure in the

mains or pipes used in Aylesbury, is remarkably small, because the

water has only to be raised two-thirds of the height due to the

pressure in the streets, in consequence of the water in the chalk

hills at the works existing in the natural level of about two

hundred feet above the town.

Almost the only

portion of the works not in duplicate is the main pipe, nearly seven

miles in length that conveys the water from the service reservoir at

Dancersend into Aylesbury. It is not usual to make such

lines of main pipes in duplicate, neither is it found to be

necessary.

The main pipe is

abundantly supplied with stop valves and other conveniences at

suitable distances, to enable any necessary repair to be quickly

executed.”

The pumping

engine referred to by Homersham has been preserved and can be seen

at The London Museum of Water & Steam at Brentford. The engine’s

description and specification are reproduced below by kind

permission of the Curator:

“The engine was

built in 1867 by James Kay of Bury. It was donated to the

museum by the Thames Water Authority’s Chiltern Division, where it

had been kept on standby since the 1930s. It was found to be

in good working order and was re-assembled at Kew Bridge in 1978-79.

The engine has

two high pressure cylinders, each connected to its own beam and

crank, the flywheel being common to what are, in effect, two

separate engines. This was a typical feature of engines used

to drive textile mills in Lancashire and Yorkshire, and it is

possible this engine was converted from textile to waterworks use.

The engine drove

a set of well pumps which used to be connected to tailrods driven

directly from the main piston rods.”

|

Date of manufacture |

1867 |

|

Cylinder Diameter |

14 inches (355 mm) |

|

Stroke |

30 inches (762 mm) |

|

Flywheel diameter |

11 feet (3.35 metres) |

|

Power rating |

36 horse power at 36

r.p.m. |

|

Last worked |

c. 1930 |

|

Returned to steam |

1979 |

The Dancersend pumping engine,

The London Museum

of Water & Steam, Brentford.

The pipeline to

Aylesbury having been completed, the Chairman was able to inform the

general meeting held in May 1868 that there was a steady increase in

customers for the company’s water; after just 4 months in operation,

revenue was running at the rate of £800 p.a. (an overstatement, as

events transpired). However, the shareholders were warned that

revenue would need to increase threefold before it would be

impossible to pay a dividend. Based on the number of prospective

customers in Aylesbury, Halton, Aston Clinton and Tring, all to be

charged at £2 per house p.a., it was estimated that the revenue

raised after working expenses should be sufficient to yield a

dividend of 5% ― but as in any large capital project, the prospect of

shareholders receiving a dividend in the early years following

completion are remote, and such proved to be the case. [12]

In view of the

rising expenditure, the shareholders were invited to approve an

increase in the company’s capital from £21,000 to £30,000 to be

raised by the issue of a further 900 shares, and

―

because it was considered to be the simplest and easiest way of

raising money ―

they were also invited to approve the directors’ decision to raise a

£10,000 mortgage, at 5% p.a., on the security of the company’s

assets. Both motions were carried.

The general

meeting held in 1869 commenced on a low note. Capital expenditure

slightly exceeded forecast while the number customers for water was

disappointedly low, at 140 households out of an estimated 1,500:

“People had

certain prejudices against the introduction of anything that was

new, and with the vast amount of ignorance which exists on sanitary

matters, they

[the directors]

were not surprised to find that people were satisfied to drink the

sewage of the town, instead of taking the wholesome liquid offered

to them when they were called upon to pay for it.”

Chairman’s address, General Meeting - Bucks Herald, 1st

May 1869.

Income for the

half year from January to June 1869 was £282 10s, falling

considerably short of the £800 p.a. predicted at the previous year’s

meeting. [13] The creation of additional shares had been fully

subscribed by the directors and their friends, the directors being

“much indebted to members of the Rothschild family for the

material aid and assistance they have rendered, and that the thanks

of the Directors are due to them for their large and generous

support.” The report of the meeting gives no information

of the nature of the Rothschild’s “material aid”, but it is

documented that in 1865 the family bought shares (Baron Lionel, 183;

Nathaniel, 181; Anthony, 183; Leopold 84) and on occasions loaned

money to the company at rates varying between 3% and 4%.

――――――――――――――

SUPPLEMENTARY POWERS, 1876.

On the 10th

August 1870, an Act of Parliament passed into law:

“. . . . to

incorporate the Proprietors of the Chiltern Hills Spring Water

Company (Limited), and granting them powers with reference to Supply

of Water to the town of Aylesbury and the vicinity thereof; and

other purposes.”

The Act gave the

CHSWC, among other statutory powers, that to raise further capital

by various means; to regulate the voting rights and other privileges

of shareholders; to break up any street, roads, highways, bridges,

and other public passages and places in which to lay and maintain

pipes; to levy and recover rates, rents, and charges for the supply

of water; and to exercise such other powers as are usually conferred

by Parliament on Waterworks Companies.

The Act also gave

the CHSWC statutory authority to supply water to Tring, but not to

villages to the north of Aylesbury. In the case of Waddesdon,

an unexpected gift was bestowed on the Company when Baron Ferdinand

de Rothschild offered, at his own expense, to lay a water main

between Aylesbury and the estate that he planned to build at

Waddesdon (‘Waddesdon Manor’).

“As soon as the

architect, the landscape gardener and the engineers had settled

their plans, we set to work, but at the outset were brought face to

face with a most serious consideration. This was the question

of water supply, as the few springs in the fields were not to be

relied on in a drought. The Chiltern Hills fortunately contain

an inexhaustible quantity of excellent water, which an Aylesbury

company works with much skill to the advantage of the immediate

neighbourhood and profit to its shareholders. Not a moment was lost

to coming to terms with the Company, laying down seven miles of

pipes from the county town to the village and thence to the

projected site of the house, and building a large storage tank in

the grounds. This subsequently proved insufficient for our

wants, as one dry summer the supply failed, and but for the

Manager’s energy, who sat up all night at the Works sending us up

water, we should have been compelled to leave the next day. To

obviate recurrence of a similar difficulty another and larger tank

was constructed.”

The Rothschilds at Waddesdon Manor

by Mrs James de Rothschild, pub.1979.

In February 1875,

Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild applied to the magistrates sitting at

the Bucks Epiphany Sessions for permission to lay the pipes along

the road between Aylesbury and Waddesdon, to which they saw no

objection “. . . . provided the work be executed to the

satisfaction of the Magristrates and of any Surveyor who they may

appoint to inspect the works . . .

”. And so work

commenced:

“CHILTERN

HILLS WATER

WORKS

EXTENSION.

− A large body of workmen have commenced work this week, to carry

the water company’s pipes from Aylesbury to Lodge Hill, Waddesdon,

to supply the new mansion of which will be shortly erected there by

Baron F. de Rothschild. A junction with the present water mains is

made at the top of Walton-street, and the pipes will be carried

thence along the Oxford and Hartwell-roads, through Hartwell, Stone,

Eythrope, and Winchendon, to Lodge Hill. The whole of the expense,

we believe, will be borne by Baron F. de Rothschild, whose property

the pipes will be; but we have no doubt that places through which

they pass will be able to participate in the advantages to be

derived from the possession in their midst of a good supply of pure

water.”

Bucks Herald, 17th April 1875.

The newspaper

report is somewhat misleading, for it appears to have been agreed

that the new mains would be taken over by the CHSWC when complete.

At the company’s interim meeting held in October, 1875, the

directors appeared to be rubbing their hands with glee at the

acquisition of a valuable asset gratis, for the Chairman was

able to report that:

“Since they last

met there has been a large amount of work undertaken by Baron

Rothschild, and the Company had laid down at his requirement ten or

eleven miles of pipe between Aylesbury and Waddesdon. They hoped to

have a large increase of customers from the extension of pipes,

which included Eythrope, Hartwell, Winchendon, Lodge Hill, and

Westcott, besides Waddesdon. So large an extension of course

implied a large expenditure of money, but that happily the Company

would not have to pay, though they hoped to have the profit of it.”

Bucks Herald, 2nd October 1875.

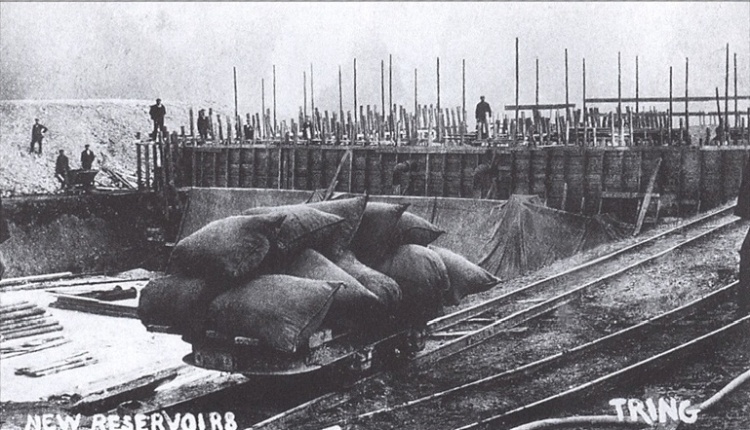

Undated photo of a reservoir under

construction at Dancersend.

The question then

arose concerning the CHSWC’s powers to supply water to areas not

covered in the company’s Act of 1870. However, under the Gas and

Waterworks Facilities Act, 1870, a provisional order could be

granted by the Board of Trade authorising, among other things,

“the construction, maintenance and continuance of gas or water

works.” An application for an order was made, which was granted

in June 1876, giving the CHSWC additional powers to supply water

Quarrendon, Fleetmarston, Waddesdon, Westcott, Wootton Underwood and

Upper Winchendon.

――――――――――――――

THE

NEW

GROUND

PUMPING

STATION AND

OTHER

WORK

(1879-1900).

The period

1879-1885 brought other additions to the system. The Directors felt

it expedient to install a second set of pumping equipment at

Dancersend to cater for the possibility that the existing set

might suffer a serious breakdown and the supply fail completely as a

result. In 1880, the new machinery came into operation together with

a new well and adits, the Chairman later stating that the Company:

“. . . . had

saved £120 in the use of coal, and that arose mainly from the use of

their new and beautiful engine

[capable of

raising some 12,000 gallons per minute],

which worked more economically and more satisfactorily than the old

one.”

Bucks Herald, 31st March, 1883.

As the demand for

water grew it became apparent that a further pipeline would

eventually be needed between Dancersend and Aylesbury, but its

high cost postponed a decision. However a decision could not be

postponed on additional reservoir capacity, to pay for which Sir Nathaniel de Rothschild

lent the Company £3,500 at

4%, to be repaid by yearly instalments when the Company could afford

to do so. Construction was at first delayed through scarcity

of labour ― due to Mr. Alfred de Rothschild building his large

mansion at Halton and Sir Nathaniel de Rothschild making extensive

alterations at Tring

― but by

1884 the new reservoir was on stream:

“Formerly it was

found that, notwithstanding pumping until late at night, it was

necessary to utilise some part of the Sabbath Day, in order to keep

up the supply, but the new reservoir enabled them to have two or

three days’ stock in hand, and the men could finish their work on

the Saturday. The whole concern could rest upon the Sunday,

and he

[the Chairman]

thought this was a pleasing feature of the undertaking. (Hear,

hear.)”

Bucks Herald, 29th March 1884.

The most

significant addition to the system at this time was construction of

a second waterworks. The need for more water became apparent during

the summer of 1884, when the water level in the wells at Dancersend

began to sink to the extent that the supply to the mains had

eventually to be restricted. The Directors

acted promptly in response. They bought a plot of land from

Nathaniel de Rothschild

at New Ground on the road between Tring and Northchurch. There

they sank a well,

laid a ten inch main between the new works

and the Dancersend reservoirs, and set temporary pumping engines

to work until the New Ground engine house was complete. This

eventually housed an

inverted compound vertical pumping engine, followed

later by a second engine, and a technical

innovation for the period was the installation

of a telephone connection to coordinate activities between the two

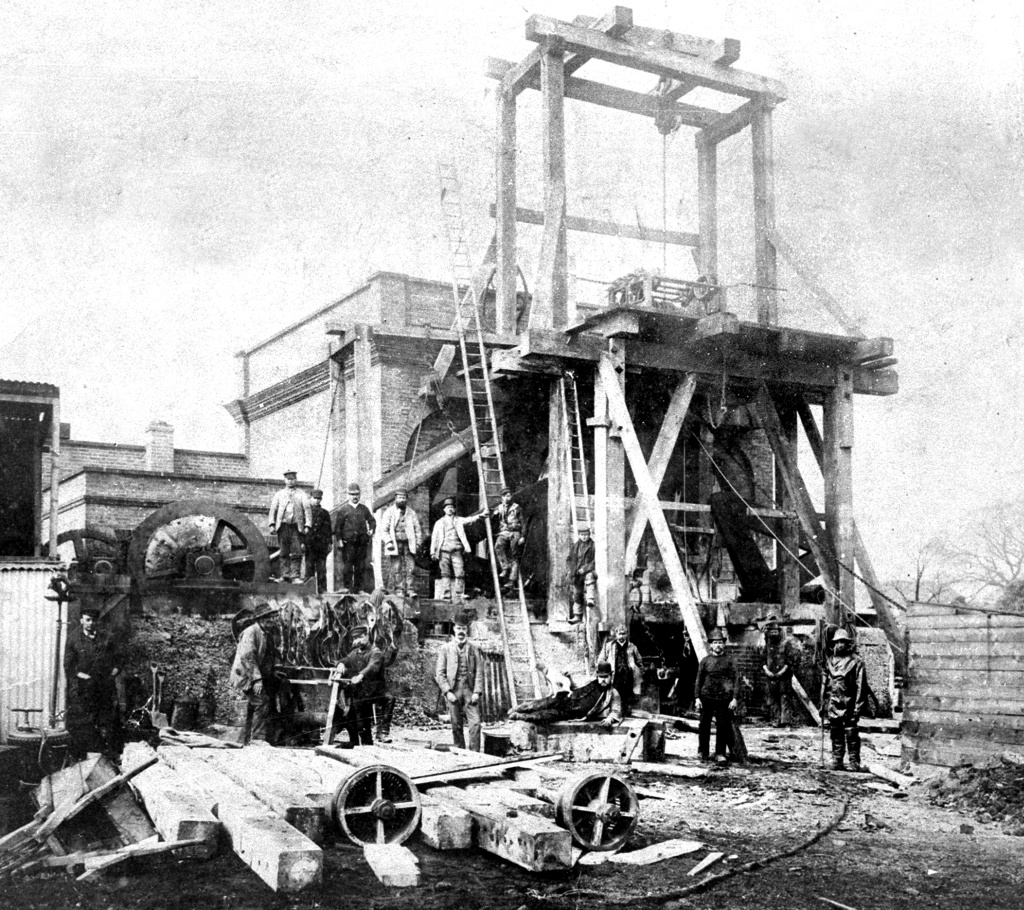

engine houses. |

New Ground Pumping Station under construction.

|

By 1886 New

Ground was in full operation, but a problem foreseen by the

directors several years earlier then resurfaced:

“The Directors

have, for some time past, been aware that the means for bringing

water to Aylesbury are altogether insufficient for supplying the

demand, and have considered that there ought to be a double line of

pipes from Dancersend Works to Aylesbury; and the Directors have

felt that if the means could be provided, on favourable terms, the

work ought to be carried out; and they are now able to inform the

Shareholders that the money required to completing the work

(estimated at about £8,000), can be obtained on such favourable

terms that it is proposed to commence and complete the work as soon

as practicable.”

Bucks Herald, 20th August 1887.

The second

pipeline was completed with money loaned by the Rothschild family

―

on the “favourable terms” referred to (3%)

―

and was in use by the following year. In 1891 a

further well was sunk at New Ground, new pumps were installed and the

existing wells at Dancersend were lowered.

――――――――――――――

CLEAN DRINKING

WATER

COMES TO

TRING,

WIGGINTON,

ALDBURY AND

LITTLE

GADDESDEN.

The possibility of laying on a water

supply to Tring had been mentioned at earlier company meetings, and

the company’s engineer had stated that it was feasible, but nothing had

been done to make the connection. Instead, all effort and resources had been

concentrated on supplying Aylesbury.

During 1869, James

James, the CHSWC Chairman, together with one of the directors,

William Brown of Tring, engaged in some private enterprise.

Between them they bought sufficient pipes to connect Tring with the Dancersend

waterworks and arranged with a contractor to lay them. This

avoided the need to place a further burden on the Company’s limited

capital until the point was reached at which its earnings were

sufficient to cover the cost

of supplying Tring, which appears to have been in the following year:

“Mr James and Mr

Brown have fulfilled their engagements with the company, and have

expended a large sum of money in laying on the water to the town of

Tring. The capital applied for that purpose, and the works

performed, are now, by virtue of our Act of Parliament, incorporated

with our capital and our works.”

Chairman’s address to the annual meeting

―

Bucks Herald 20th August

1870.

1881 saw

Wigginton connected to the system. It was estimated that to

supply Wigginton with running water would require four to five miles

of pipeline and a reservoir (in fact “a new tank” laid in

“Mr Butcher’s wood”). In view of the cost of the project

vis-à-vis the anticipated revenue, the Directors had reservations

about its profitability; as the Chairman put it, Wigginton was “a

destitute district”! However, Nathaniel de Rothschild together

with Messrs Williams (of Tring) and Valpy not only guaranteed the

Company against loss, but paid for the pipeline to be laid.

Aldbury

was connected to the supply in 1900.

Although a supply of running

water was now available in Tring, Aldbury and Wigginton, many

households continued to draw their water from wells, which, due to

sewage contamination, presented a risk of waterborne disease.

Indeed, until into the 20th Century the Bucks Herald

carried reports of patients being admitted to the isolation

hospitals at Tring and Aldbury suffering from typhoid, the source of

which was usually attributed to polluted well water.

The Little Gaddesden area was better served, thanks to the Brownlow

family of Ashridge. The Ashridge Water Company was formed in

1856 at the instigation of the guardians of the 2nd Earl Brownlow of

Ashridge House, Little Gaddesden. In addition to supplying

Ashridge House, the company piped water to the villages of Little

Gaddesden, Hudnall and Ringshall from a new covered reservoir

at Ringshall via a steam-driven pumping station and well in Little Gaddesden.

Walter Parker built the reservoir at Ringshall Meadows; Robert and Joseph Paten of

Watford sank the well, 6 feet in diameter and 255 feet deep; Joseph Harris of Berkhamstead erected the

engine and boiler house for the pumping station; and Messrs Eaton

and Amos of London supplied the steam-engine, boiler, and pumps, and

also laid the water mains, and by 1857 a clean water supply was

available. In 1930, the steam engine was replaced by electric power and the boiler chimney demolished. It appears that the well

was used to supply water to the neighbourhood until at least 1980,

but the former pumping station and the water tower now lie derelict.

The now abandoned Ashridge Water Company

tower at Little Gaddesden.

――――――――――――――

SEWAGE DISPOSAL

A

“SINGULARLY

DISASTROUS”

SEWAGE

SCHEME

The subject

of public health now turns from water supply to drainage, and to the public

sewers that carry sewage and rainwater run-off for treatment

and/or disposal.

In 1877, Dr.

C. E. Saunders, [15] Medical Officer of Health

for Middlesex and Hertfordshire, published a report on the

sanitary ― or rather the insanitary ― conditions prevailing in

parts of Tring. [16] Some of the squalor

he refers to makes disturbing reading. On the need for the

town to acquire effective sewers he had this to say:

“This

necessity can scarcely by better appreciated than by comparing

two streets in the Western Road ― Charles Street and Langdon

Street ―

the one with pail privies, emptied into an open ashpit and

having slop-water cesspools; the other having a sewer into which

many of its houses can, and do, drain. The filth and

squalor of the one and the decency and order of the other could

scarcely fail to show the necessity for a better system of filth

removal. Another place I would refer to is Church Alley.

Here there is a row of 10 privies within about 8 feet of the

back-doors of the houses; these privies have pails, and these

pails when full, as they usually have been when I have seen

them, are emptied into a huge ashpit, also near the back-doors

of the houses.”

Sanitary Conditions of Middlesex and Hertfordshire for

the year 1877.

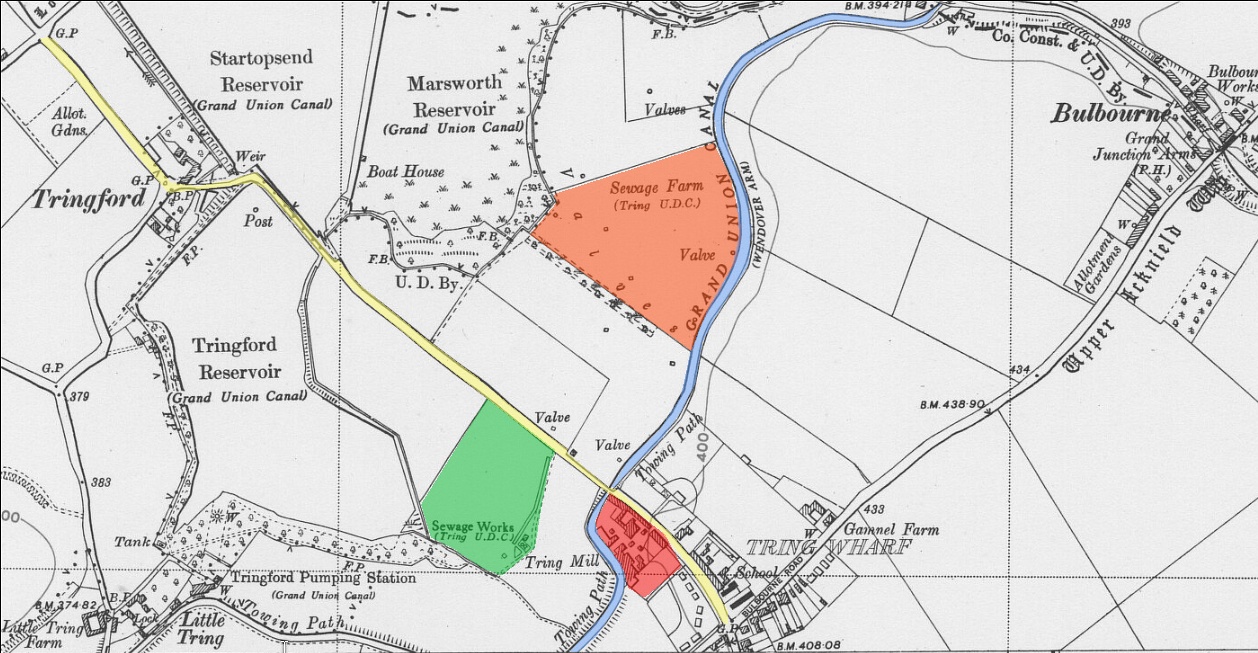

In 1867, the

Tring Local Board of Health [17] first

attempted to address the problem of sewage disposal in a

systematic manner. In that year the Board built a main sewer

under Brook Street, commencing beside the Silk Mill Pond [18]

and leading down to New Mill where it entered an open ditch.

This ditch led under the Wendover Arm canal into either

Tringford or Startops reservoir depending on the setting of a

sluice.

At a later

date the Board built another sewer, the ‘cross culvert’, which

connected the Frogmore area of the town with the Brook Street

sewer. Writing some years later, Dr. Saunders had this to say

about the construction of these sewers:

“The Board’s

first attempt to carry out a scheme of sewage was so singularly

disastrous that their efforts for the last five years have been

confined to devising means to undo the mischief that was done by

draining the Silk Mill Reservoir”

[i.e. the mill pond].

Sanitary Conditions of Middlesex and Hertfordshire for

the year 1877.

To explain

the problem that Saunders refers to, it is first necessary to

say something about the Silk Mill Pond and Tring’s water courses

at the time, for construction of the cross culvert was to lead

to expensive litigation and years of delay in resolving the

town’s sewage disposal problem.

The Silk Mill

Pond received water from three feeds, one man-made and two

natural. The man-made connection is a subterranean culvert

that connects the Dundale Lake (located at the junction of

Icknield Way and Dundale Road) to the Silk Mill Pond. It

was built c. 1824 by the Silk Mill’s owner, William Kay, to

supply water to drive the mill’s waterwheel. The Mill Pond’s two

natural sources were (i) springs that arose beneath it and (ii)

the Horse Pond, a narrow stretch of water that once lay in the

vicinity of today’s Bishop Wood School (see map below). A stream connected

the Horse Pond with the Silk Mill Pond ― in terms of today’s

locations, it left the Horse Pond, crossed Frogmore Street

somewhere in the vicinity of the Black Horse public house,

passed between the Churchyard and the Red Cross Hall, and

entered the Silk Mill Pond somewhere in the vicinity of the Fire

Station. The new cross culvert ran parallel to this stream

for at least part of its length, then passed under the

Silk Mill Pond ― which had to be drained to enable its

construction ― to join the main sewer in Brook Street

(centre right on the map below). |

Above: the Horse Pond (bottom left) feeds the Silk Mill

Pond (centre right) via the connecting stream.

Below: the Silk Mill

Pond today, much reduced in size (Tring Church just visible centre background)

|

When the

cross culvert was complete and the Silk Mill Pond refilled,

its level was seen to be much lower than before.

Investigation of the cause showed that the stream from the Horse

Pond together with some of the contents of the Silk Mill Pond

were seeping into the cross culvert, then into the Brook Street

sewer. The impact of this diversion was to derive the Silk

Mill of part of its water supply ― perhaps not a big issue, for

a steam engine was by then powering the Silk Mill’s machinery ―

but more important was the reduction in the volume of water

flowing along the Feeder and directly into the Wendover

Arm. The diverted water was now passing along the Brook

Street sewer and into the open ditch at New Mill that passed

beneath the canal and into the canal reservoirs. To

make good the shortfall in water supply, the Grand Junction

Canal Company had ― at additional cost ― to raise a greater

volume of water from the reservoirs into the canal in order to maintain

its level. Another problem was that the village of Long Marston’s

water supply was chiefly obtained from the overflows of Tringford and Startops reservoirs, which was now contaminated with Tring’s sewage.

This added further complaint.

However, the Tring

Local Board of Health refused to remedy the problem. The

Grand Junction Canal Company therefore sought an injunction to (i)

restore the shortfall of water into the Wendover Arm and (ii) to

restrain the Local Board from polluting the company’s reservoirs

with the raw sewage they were now receiving from the Brook

Street sewer. The canal company won its case (Grand

Junction Canal Company v. Shugar, 1871) leaving the Local Board

to

face the legal costs and the problem of addressing the

injunction’s requirements; the latter was no easy matter, as

events were to prove.

During the

four years following the court case it is difficult to ascertain

the course of events, for the Local Board considered the problem

in closed session, a procedure that in itself was to cause major

dissatisfaction in the community, for the ratepayers ― not

unreasonably ― wanted to know the basis of decisions concerning

the expenditure of local taxes. From the newspaper reports

of later meetings it is possible to surmise that some form of

agreement was reached with the canal company, but this was

abandoned following much local disagreement, principally from

Baron Nathaniel de Rothschild, by then owner of the extensive

Tring Park Estates.

The Local

Board next engaged John Bailey Denton, [19] a

civil engineer and expert on sewage engineering, to devise a

suitable disposal scheme. Bailey Denton drew up a plan

that appears to have met with the Local Board’s approval, for

they submitted it to The Local Government Board [20]

for sanction together with an application for a loan to fund

construction. In response, the Local Government Board appointed

an Inspector, Major Hector Tulloch, formerly of the Royal

Engineers, to hold a public inquiry into the scheme.

A number of

inquiry meetings then took place commencing on the 7th

October, 1875, in Tring’s Vestry Hall. In that year an

important Act ― The Public Health Act (1875) [21]

― passed into law designed to combat the filthy urban living

conditions that caused various public health threats, including

the spread of many diseases. During the inquiry meeting

held on the 18th December, Major Tulloch reminded

those present that under clause 17 of the new Act it was now an

offence to pollute water courses with sewage:

“Nothing in

this Act shall authorise any local authority to make or use any

sewer drain or outfall for the purpose of conveying sewage or

filthy water into any natural stream or water course, or into

any canal pond or lake until such sewage or filthy water is

freed from all excrement or other foul or noxious matter such as

would affect or deteriorate the purity and quality of the water

in such stream or watercourse or in such canal pond or lake.”

Clause 17, Public Health Act 1875 [38 & 39 VICT.

Ch. 55].

Sewage

pollution of the canal reservoirs had led in part to the costly

legal conflict between the Local Board and the Grand Junction

Canal Company. To avoid any recurrence, whatever scheme

the Local Board adopted would require some form of filtration to

purify any discharge of effluent into a water course, and

filtration did form part of Bailey Denton’s proposed scheme.

The newspaper

description of the Bailey Denton scheme is vague, but from what

is said it required 17 acres of land for “intermittent

filtration” (described below). The filtered sewer

water ― ‘effluent’ ― was to be run off into a 30 acre reservoir

that was to be connected to the canal, while the remaining

sewage was to be spread over the land as agricultural

fertiliser. It is unclear whether the Local Board adopted

this plan to the letter, but considering the number of years

that were to elapse before anything actually happened, and the

progress made in the treatment of sewage in the intervening

period, the scheme carried out is more likely to have been a

refined version. However, what Bailey Denton’s plan did

amount to was, in principle, a ‘sewage farm’, which was what was

eventually built at Gamnel to process the town’s sewage.

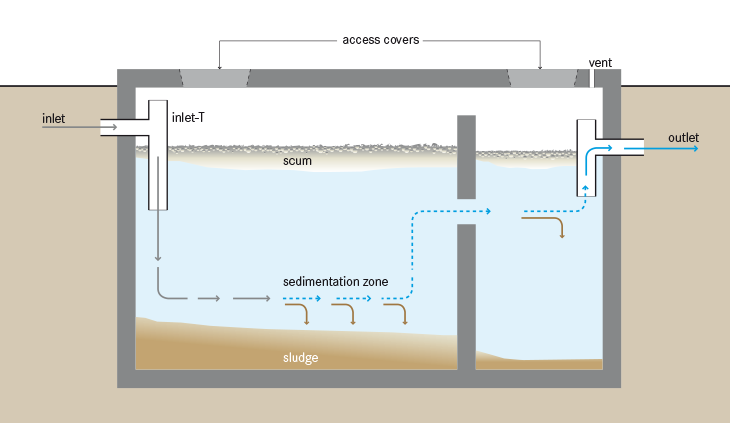

In general, a

sewage farm comprises an area of agricultural land irrigated and

fertilised with sewage. The product being ‘farmed’ is the

sewage combined with the microbes and bacteria that are used to

break it down. In this context, the term ‘intermittent

filtration’ (referred to above) has a particular meaning.

In 1868 Sir

Edward Frankland conducted a series of experiments which showed

that natural land did not clog up if sewage was applied to it in

small quantities and allowed to trickle away before the next

dose was applied. This is the principle of ‘intermittent

filtration’. Coupled with this, efforts were made to reduce the

area of land necessary for treatment of the sewage by using a

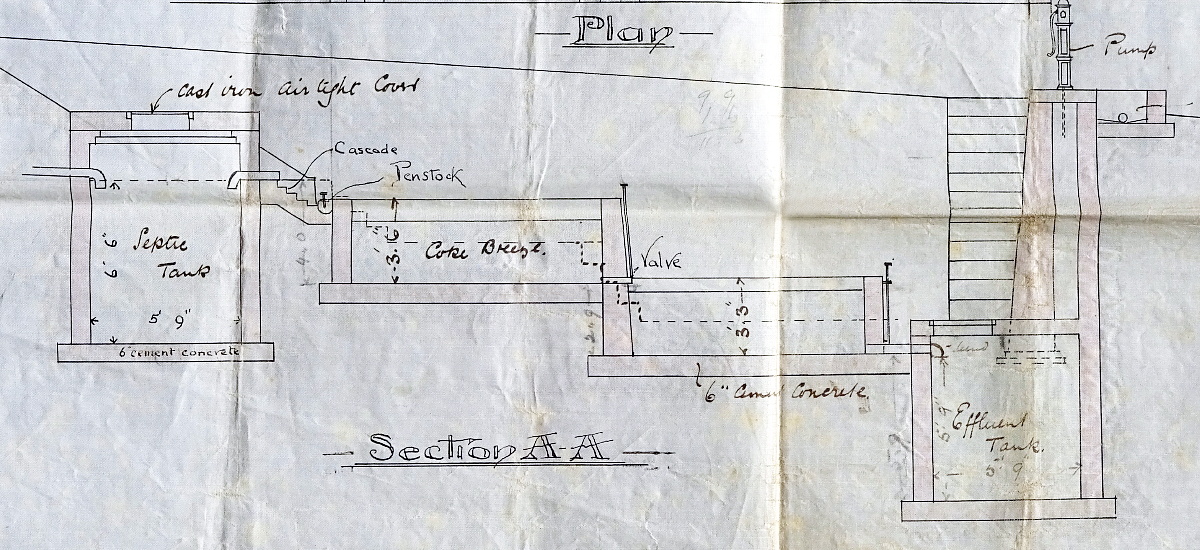

pre-treatment process, the most common form of which was to

channel the raw sewage into settling tanks into which a chemical

was added to speed up the precipitation of the solid matter.

The most common precipitant was lime (also used as a water

softening agent at the Dancersend Waterworks). When

sufficient sludge had accumulated in the settlement tank it was

collected and used as agricultural fertiliser.

Bailey Denton

joined Frankland by making another important contribution to the

principle of sewage farming. He observed that when land

was ‘under drained’, [22] water and sewage

flowed more rapidly through the soil into the under drains; that

water discharging from the under drains was clear; and that

plant growth flourish where under drainage was carried out.

These principles were later applied to the construction of

Tring’s first sewage farm at Gamnel.

According to

the notes left by the 19th-century local historian Arthur

Macdonald Brown, in order to comply (in part) with the

injunction, Bailey Denton also laid a 9-inch iron pipe from the

Horse Pond to the Silk Mill Pond to restore the flow of water

that ran between the two before the cross culvert was built.

At the same time the Silk Mill Pond was diminished in area and

‘puddled’ (i.e. lined with impervious clay) to better

enable it to retain the water that flowed into it from the Horse

Pond and from Dundale Lake.

――――――――――――――

PRESS

REPORTING

OF LOCAL

BOARD

MEETINGS

An

interesting side issue to emerge from the public meeting held in

the Vestry Hall on the 18th December 1875 had more to

do with democratic government than with Tring’s sewage problems.

The meeting

was of Tring’s ratepayers and not part of the Government Board’s

inquiry into the proposed sewage scheme that was then taking

place. Some fifty attended, a Mr. C. Chappell taking the

chair. While the meeting had been called to discuss the

sewage scheme and its associated costs, dissatisfaction was

expressed that the press were not being admitted to Local Board

meetings and that the Town was in ignorance of how decisions

were being taken:

“Mr. J.

Grange ― The ratepayers generally like to know what is done by a

public body who represents them. I should say that whatever may

be done in the future, should be done in a more satisfactory way

to the ratepayers. I therefore beg to propose ‘That at

all meetings of the Local Board the representatives of the press

be admitted’. . . .

Mr.

Chappell ― “The time has come, and it is only right that we

should know what is done. Don’t you think it unjust that we

should find money, and not know how that money is spent? Are not

the ratepayers as well able to appreciate the spending of their

money as any gentlemen of the Local Board?

The motion

was put to the meeting and carried with acclamation.”

Bucks Herald, 18th December 1875

And so

reports of Tring Local Board meetings began to appear in the

press.

――――――――――――――

THE

TRING

SEWAGE

FARM

Following the

inquiry meetings chaired by Major Tulloch, no significant

advance in treating the town’s sewage appears to have made for

the next decade; indeed, taking account of the canal company’s

injunction it is a mystery how, during this period, the problem

was managed. Even the Government Board (whose duties

included supervising the law relating to public health)

wanted to know, for at a Local Board meeting held on 3rd

June 1880 the Clerk read a letter from that body asking what had

prevented the adoption of a sewerage scheme for the district; he

was instructed to reply that they “were doing the work by

degrees.” Then, in 1885, the Medical Officer of Health

announced in his annual report that:

“The

[Tring

Local] Board have adopted a method of sewage treatment which

promises success - viz., the precipitation of the sewage by

chemicals in tanks, and the intermittent filtration of the

effluent, on ground under-drained and prepared for the purpose.”

The canal

company agreed to supply water to operate a small water wheel

for mixing the chemicals necessary for “the precipitation of

the sewage”, for which they charged the Local Board £5 p.a.

subject to their use of the canal water being restriction to

50,000 gallons a day. However, with regard to sanitary

matters elsewhere in the town, the same report goes on to say

that . . . .

“. . . . it

would be an anomaly that the main street of the town should

remain the worst sewered, and it is to be hoped that the

[Tring Local] Board will relay the

sewer along the High Street as well as complete the general

sewering of the town. There are special difficulties in

sewering the main street, owing to it being so narrow, and to

there being no other approach to the West-End except through the

town, but they are not of such a nature as to be

insurmountable. Thirty-one houses have been cleansed and

disinfected.”

Tring and Urban Sanitary Authority Report

for 1885.

Another three

years were to elapse before there is any mention of the sewage

farm being in operation (and a further decade before anything

was done about re-sewering the High Street). But as the

following newspaper report refers to various crops under

fertilisation, the sewage farm appears to have been in operation

for some time before a “party of gentlemen” from the town

paid it a visit:

“The party on

arriving at the Farm was met by Mr. Mead, who explained the

operation of the disposal of the Tring sewage which is being

carried out there. The sewage flows by gravitation from

the town, and is delivered to the Farm at the highest possible

point. The area of land under irrigation is twenty acres,

and the crops growing on the land are oats, Italian rye grass,

wheat, mangels, and cabbages, and preparations are being made

for the cultivation of other crops.

The party

walked all round the Farm, and finished up inspecting the point

at which the effluent water runs away into the canal. This

small stream is perfectly bright and clear, and absolutely free

from smell and taste, and in every way proves how thoroughly the

land is doing the work of purifying the sewage. The party,

as a result of their visit, were unanimously of the opinion that

the whole operation is carried out in a thoroughly business-like

manner, and that the freedom from nuisance was evident.”

Bucks Herald, 12th May 1885.

For many years Ralph Seymour (in later life the Reverend Ralph

Seymour) worked at the Tring Flour Mill, eventually becoming its

Manager. In his (unpublished) autobiography, he also

refers to the fertility of the ground irrigated by the sewage

farm:

“Percy

[Mead]

was tenant of some ground below the mill, owned by the local

council, as part of the sewage works, where an open irrigation

system was employed. From time to time sewerage liquor was

directed over the ground in rotation. Consequently Percy

was always able to grow exceptionally large mangel wurzels

there, and each October he would invariably search for two of

the largest specimens and place them, one on either side of the

door to the mill office, much to the governor’s chagrin.”

The Local

Board had entered into a ten-year contract with Thomas Mead for

receiving the sewage on his land. When that agreement had

run its course it was renewed for a further ten years, Mead

taking the sewage and treating it and the Council paying him

£125 a year so long as ‘surface water’ (not a part of the sewage

treatment) was excluded successfully from what he received; but

if the drainage system failed to keep out surface water, the

payment was to increase to £150. Under the old contract

some twenty acres of land were under irrigation, but following

its renewal Mead added a further ten acres.

――――――――――――――

NIGHT

SOIL

AND SCAVENGING

|

|

|

Night soil collectors |

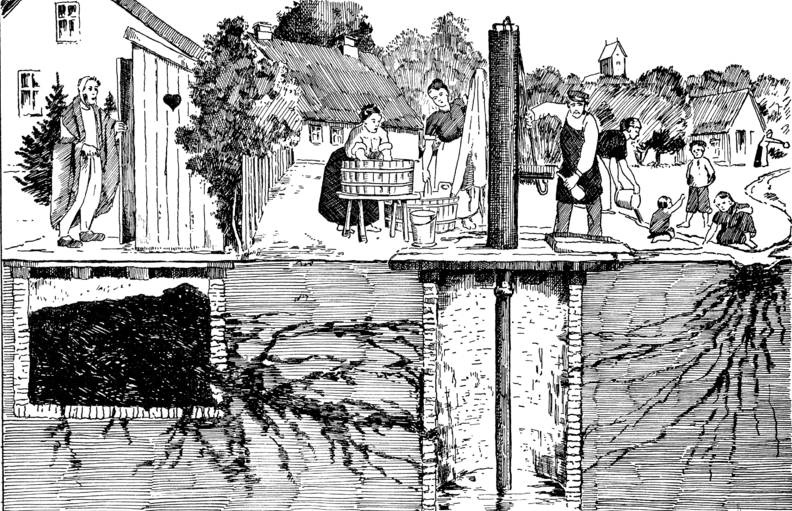

Two other

aspects of public health addressed by the Public Health Act

(1875) appear in press reports of Local Board meetings.

They were the removal of “night soil” and “scavenging.”

At the

meeting held in June 1879, it was resolved “That the Board

take immediate steps to purchase a night-soil cart.”

Fortunately, the term “night-soil” (a.k.a. “slops”)

is one that we are unfamiliar with today, but our Victorian

forbears knew it well. It is a euphemism for the human

excrement collected nightly by a contractor from buckets and

privies, which for convenient access were usually placed in an

outhouse.

In an age

before water closets became standard fittings, many households

―

particularly those of the poor ― relied on more basic means of

disposing of human excrement. At the lower end of the

scale was the bucket, while the better off used “earth

closets” ―

Dr. Saunders, the town’s former Medical Officer of Health, left

a description of those used in Tring (APPENDIX

II). The contents of buckets and earth closets had

to be disposed of, hence the use of a ‘night-soil cart’ to carry

away this particular spoil. The operators of the service

generally sold the product of their endeavours to farmers to be

spread on the land as fertiliser. Earth closets remained in use

in parts of old Tring until the 1950s. |

A purpose-built night soil van.

|

The term

‘scavenging’ refers to street cleaning, a requirement that

appears in the Public Health Act (1875), clause 42 of which

required local authorities “to provide for cleansing of

streets and removal of refuse.” At a ratepayers’

meeting to discuss the proposed sewage

scheme for the town

held in November 1875, a motion was put to the meeting, and

carried unanimously, “That it is desirable that a thorough

system of scavenging should be adopted by the Local Board”,

which implies that either nothing of the sort was in place or

what there was, was not “thorough.“ Nothing then

appears in the press until the Local Board meeting held on the

12th June 1880, when:

“Mr. Baines

[the Town

Surveyor and Inspector of Nuisances] was instructed to make

enquiries as to the terms upon which the scavenging of the

streets would be undertaking, and to report to the next meeting

of the Board.”

The

tender of 4 shillings a day submitted by coal merchant and

removals contractor John Gower was accepted, “one horse and

one man” being provided for the work; in 1888 the rate was

increased to 5 shillings a day. This contract continued

until at least 1895, but the extent of the scavenging and the

location of the rubbish dump at this time are not mentioned.

The Town’s

rubbish was later dumped into the abandoned section of the

Wendover Arm canal at Little Tring.

――――――――――――――

A

NEW

SEWAGE

SCHEME

In March 1895

the Thames Conservancy wrote to Tring Council [17]

alleging that the town’s sewage was again running into the canal

and polluting the Thames and its tributaries, and they gave

notice under the Rivers Pollution Act to abate the nuisance.

This alarmed the Council, for they were aware of the cause of

the problem and that remedial action would involve considerable

investment in a modified drainage scheme for the town.

The existing

brick-built sewer through the High Street had been constructed

by the Local Board during the 1860s. Since then they had

sewered various streets in the town, but the problem they had

not solved completely was how to manage storm water. In

stormy weather the greatly increased volume of surface water

passing down the main sewer caused an overflow of sewage into

the Silk Mill brook, which fed the canal. The polluted

water then found its way across the canal’s

overflow weirs into the streams that feed the Thames.

Previous attempts to separate the sewage from storm water had

failed.

Faced with

the possibility of further legal action, the Council engaged

Professor W. H. Corfield, [23] a drainage

expert, to report on the problem. In September 1895 the

Council’s civil engineer, Gordon Thomas, guided by Corfield’s

conclusions, presented the Council with a preliminary report.

This was fully discussed and many suggestions were made.

Two months later Thomas presented a detailed report together

with estimates and drawings, and after further discussion the

Council adopted his scheme. In essence, this involved

building a weir (or dam) across an existing culvert near to the Silk Mill