|

NOTES AND

EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

CHAPTER

1.

EARLY RAILWAYS

INTRODUCTION

|

“It is a common error to

suppose that there were neither railways nor locomotives

before the era of George Stephenson, Edward Pease, and

the Stockton and Darlington Railway. The fact is, that

mechanical locomotion, by the adhesion of the rim of a

loaded wheel to the surface upon which it rolled, while

being forced to revolve by some tangential force, is

very old . . . .”

A History of the

Stockton and Darlington Railway, J. S. Jeans (1875). |

. . . .

indeed, not only does the history

of the railway locomotive predate the Stockton and Darlington

Railway by some two decades, but the history of railways predates

that of railway locomotives by at least two centuries.

To some extent, the early development of

rail transport stemmed from the abysmal condition of British roads.

The Romans understood the need for good roads and how to build them,

at least to the standard that they required, but following their

departure from our shores road building and maintenance sank into

a state of oblivion from which it did not begin to emerge until the

18th Century. Even then, it was many years before a

system of trunk roads of a reasonable standard were built. Thus,

in the absence of good roads, the only practical means of

transporting deadweight cargoes such as coal, stone and minerals in any quantity was by water, and many of our early railways were built to link

mines and quarries to the nearest waterway.

Besides

the guidance that a line of rails imposes on a train of wagons,

rails also greatly reduce ‘friction’; in other words, the resistance encountered

when one body is moved when in contact with another. Much less

energy is required to move a wheeled vehicle over smooth and

hardened rails, than over the softer, more resistant surface of a

road. Whereas a horse could haul a wagon loaded to ⅝ ton over an

unmade road, or 2 tons if on a macadamised surface, the same horse could haul 8 tons on a railway and up to 50

tons on a canal. And so the question arises, why, when they arrived

in the 1840s, did the new locomotive-operated railways quickly

displace the canals?

――――♦――――

THE CANALS

Canals were our earliest man-made bulk

carriers, the Bridgewater Canal [1] being the first to

enter

service. Following its success, many more canals were built until

by their peak in the 1840s there was over 4,000 miles of inland

waterways.

During the early period of canal building,

speed on transit was relatively unimportant when balanced against a

canal’s capacity to move heavy loads over distance. But as the

Industrial Revolution progressed, time increasingly cost money and

the new locomotive-operated railways soon demonstrated that they

could move heavy loads reliably and at speed. Whereas three men

could move 50 tons in a pair of narrow boats at the pace of a

walking horse, the same manpower could shift 500 tons in a goods

train at ten times the speed.

|

|

The leisurely pace of

canal traffic. |

And other factors acted against

canals:

• compared with a canal, railways were cheaper to build and more adaptable to the

terrain, for a canal needed a sufficient water supply that was

sometimes difficult and expensive to obtain;

•

crossing high ground required a system of locks, which were

expensive to build and maintain, slowed traffic, and often

required one or more pumping stations to lift water to their

summit level;

•

droughts in summer and ice in winter brought canals to a

standstill, often for long periods;

.JPG) |

|

Ice, an old enemy of the

canals. River barges frozen in on the Grand Union Canal

at Hanwell

during the winter of 1962-3. |

•

there were no mandated standards governing canal construction;

thus, interworking between different waterways was sometimes impossible

due to the incompatible sizes of the canal craft designed to operate

on them;

•

canal companies resisted the introduction of steam-powered

barges for many years due to their unwillingness to invest in

bank reinforcement for protecting against the erosion caused by

propeller turbulence;

•

the waterway network had no equivalent to the Railway Clearing

House for allocating tolls for traffic moving between different

companies’ systems, which could result in chaotic charging,

particularly for long distance

traffic; and

last but not least was . . . .

• the parochial and complacent attitude of

the canal companies. This prevented mergers that would have brought

longer waterway routes under unified control. From an early

date, mergers between railway companies resulted in longer

routes coming under a single management with accompanying gains

in technical standardisation, administrative efficiency and economies of scale.

And so

the new railway companies quickly captured most of the canal trade, leaving once

important canals to eke out a bare existence, or go to the wall ― and

many did.

――――♦――――

THE RAILWAY ERAS.

“It will be evident that such a work as

this could only have been undertaken in a country abounding with

capital, and possessing engineering talent of the highest order. The

steps, by which the science of Railways has arrived at its present

position, were slow yet progressive. Railways of wood and stone were

in use, as well as the flat iron or tramrail, in the middle of the

seventeenth century, particularly among the collieries of the north,

and were gradually improved from time to time; they still, however,

retained a character totally distinct from those structures which

will soon form the means of transport through the principal

districts of the Kingdom.”

The History of the Railway

Connecting London with Birmingham, Lieut. Peter Lecount RN

(1839).

For the purposes of this account, ‘early

railways’ were those that predate 1830 and the opening of the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the Stockton and Darlington

Railway (1825) lying on the transitional boundary.

Broadly speaking, railways fall into three

eras, although the transition between each was more a matter of

evolution than of sudden change, with some examples of early types

of railway surviving well past obsolescence, even into the 20th

Century.

Wooden railway - a peg running

between the planks kept the truck in alignment.

National Railway Museum, York.

The earliest era was that of the ‘wooden

railway’, so named because of its timber construction. Wooden trucks

were pushed along wooden planks using a peg running within a slot to

keep the wagon wheels aligned with the planks. By the beginning of

the Industrial Revolution, the planks had become wooden rails, the

wagons were larger and horse-drawn and their wheel were by then

acquiring iron tyres, later becoming all iron (ca. 1730). Towards the end of this era, the life of wooden rails was being

extended with the use of cast iron reinforcing strips (ca.

1770), and so there began a gradual transition into the intermediate

era, that of the ‘iron railway’ (ca. 1790), during which

all-iron rails gradually replaced the earlier timber and composite

construction, and the first steam locomotives made their

tentative appearance.

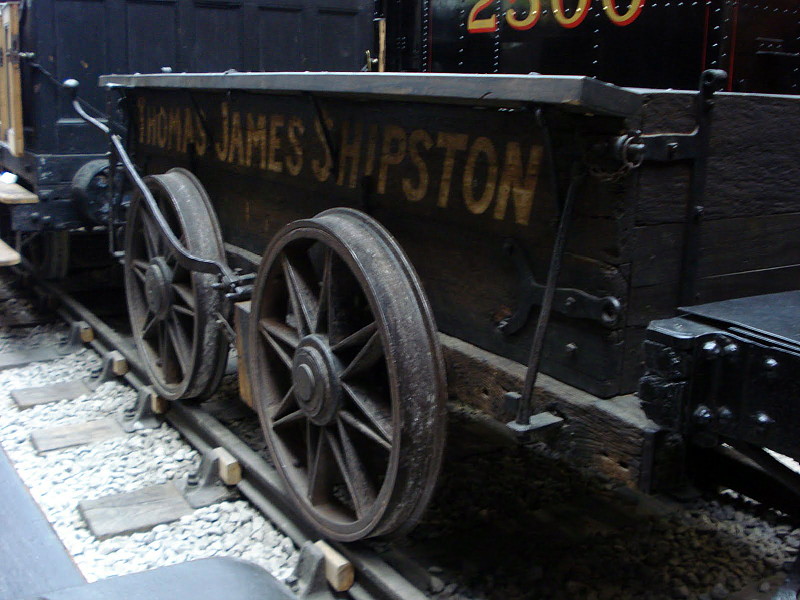

Moving on to the 1820s, this wagon

from the Stratford and Moreton Tramway

has iron flanged wheels

designed to run oniron edge rails, but note the absence

of suspension and shock-absorbers (buffers).

National Railway

Museum, York.

In its

turn the iron railway reached its zenith in the Stockton and

Darlington Railway, from where railway engineering (together with

railway administration) progressed to the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway, which marked the beginning of the era of the modern public railway. From then on entrepreneurs entered the

field, creating railway companies that eventually grew to form a

national network operated solely for the purpose of creating

wealth for its constituent companies’ shareholders.

――――♦――――

TERMINOLOGY.

In common usage, we refer today to metal

tracks designed to carry wheeled vehicles as ‘railways’ or

‘tramways’, although at the lightweight end of what is quite a broad

spectrum of descriptions there exists some distinction (both between

and within) ‘underground’, ’rapid transit’, ‘light rail’ and

‘tramways’.

|

|

|

The Little Eaton Gangway,

Derbyshire (1795-1908).

Note the L-section plate rails,

typical of many early railways. |

The terminology used to describe early

railways is more confusing. It was subject to regional variations,

to the type of engineering employed, and how the owners wished to

describe their line. Thus, the terms ‘wagonway’, ‘plateway’,

‘tramway’, ‘dramway’, ‘gangway’ and even ‘railway’ (or ‘rail-road’)

crop up, to name but some. Sometimes the name implies the type of

engineering employed, but not always ― strictly speaking, the

‘Surrey Iron Railway’ (described later) was a ‘plateway’, a term

that applies to horse-operated lines that utilised cast iron single

or double L-shaped plates on which ran wagons fitted with rimless (unflanged)

wheels. The term ‘railway’ came to describe lines constructed with

iron ‘edge rails’ that supported vehicles fitted with flanged

wheels, the predecessor of the modern railway.

However they were named, early

railways in general:

• were short lines, built mainly to transport

their owners’ goods, often to a waterway wharf;

• used horse-drawn wagons (steam traction began to

make its appearance towards the end of the era);

• were engineered with embankments and cuttings to

level the terrain, and bridges to cross waterways, but often

incorporated steep, rope-worked ‘inclines’ that were avoided by

later railway engineers;

• usually consisted of a single track with passing

places;

• used rails of various designs and materials

(wood, wood/cast iron composite, cast iron and later malleable iron

[2]), set to various gauges and mounted on

transverse wooden sleepers, or on blocks of either wood or stone and

sometimes a mixture (as in the case of the Stockton and Darlington

Railway);

• provided a gravelled surface between the rails

suitable for horses to walk on, or if transverse sleepers were used,

they were sunk into the ballast to avoid being damaged by horses’

hooves.

The ‘early railway’

era ended with the opening of the Liverpool

and Manchester Railway in 1830. From then on railways began to be built as

businesses in themselves, the aim being to make profits for their investors. They

offered the public a service carrying not only goods, but passengers;

they used locomotive-hauled trains; they operated to a timetable accompanied by a schedule of fares and charges; and,

increasingly, they linked towns and cities throughout the land.

These are all

features that we would recognise in our railway network today.

――――♦――――

WAGONWAYS.

Although ‘wagonways’ ― to use a general

description ― undoubtedly existed in Britain before the 17th

Century, the earliest to be recorded was built ca. 1603 to

convey coal from the mines at Strelley to the west Nottingham, to Wollaton, a distance of some two miles. [3] Its builder, colliery

owner Huntingdon Beaumont, later constructed other wagonways to

serve his mining interests near Blyth in Northumberland:

“Among the rest of the ‘rare engines’ introduced by

master Beaumont into the coal trade, one was ‘Waggons with one horse

to carry down coales from the pits to the staiths to the river.’ Lord Keeper Guilford, in 1676, thus describes them: ‘The manner of

the carriage is by laying rails of timber from the colliery down to

the river, exactly straight and parallel; and bulky carts are made

with four rowlers, fitting these rails, whereby the carriage is so

easy, that one horse will draw down four or five chaldron of coals,

and is an immense benefit to the coal merchants.’”

An Historical, Topographical, and Descriptive View of

the County of Northumberland,

Eneas Mackenzie (1825).

From here began the evolution of the

wagonway in the north-east of England, where many local systems grew

up to serve the collieries around the Tees, Tyne and Wear. It is

with some justification that this locality can be described as the

‘birthplace of the railway’. [4] These

wagonways were laid across land between colliery and waterway by

private arrangement with the owners, the proprietor of the wagonway

paying an annual rent under the name of ‘wayleave’. Where a public road had to be crossed,

this was by consent of the local authority. But as wagonways

developed, it was not always found practicable to arrange such

informal rights of passage, particularly when a line of considerable

length had to be laid down, and an Act of

Parliament became a necessary expedient. Such private legislation was used

to obtain the necessary powers to cross public

highways and to purchase ― by compulsion, but with fair compensation ― private land on which to lay the track.

The first application to Parliament for a ‘Railway Act’ was made in

1801, to authorise construction of the Surrey

Iron Railway. By then compulsory purchase was

already established in Acts authorising the construction of

canals. [5]

Besides being the first Act

of Parliament to contain the work ‘Railway’ ― it was in fact a

wagonway ― the Surrey Iron Railway was the first line intended for

public use. In the following 20 years, more such lines were

built (listed in the Appendix). But despite their importance to particular

businesses and localities, in themselves wagonways were

unimportant. Short and widely dispersed, they did not become part of the

railway network that eventually extended throughout the

land. Their importance lay in providing a testing ground for the

early development of railway engineering, both civil and mechanical, in particular the

development of the malleable iron edge rail and the steam

locomotive.

Despite their misleading titles, the following are

examples of some notable wagonways.

――――♦――――

BRANDLING’S RAILROAD

(the Middleton Railway).

Opened in 1758, this wagonway

was built by Charles Brandling to

link his collieries at Middleton with Leeds. It is

credited with being the world’s oldest continuously working line, a

short section ― a standard gauge railway since 1881 ― remaining in

use as a heritage site.

Brandling needed to transport his coal to

market in Leeds, but did not have access to a waterway for that

purpose. His agent, Richard Humble, solved the problem with wooden

wagonways, which were common in his native north east. The first,

constructed in 1755, crossed Brandling’s land and that of friendly

neighbours to riverside staithes, but two years later he began work

on a wagonway into Leeds itself. The line was financed privately and

operated using horse-drawn vehicles called ‘corves’.

Wishing to protect his investment with a

degree of permanence, Brandling obtained a private Act of

Parliament, the first piece legislation to refer to a wagonway.

Unlike later canal and railway Acts, it did not give powers of

compulsory purchase, but instead ratified existing wayleaves. In

return, the Act required Brandling to send into Leeds 240,000 corves

(a corf was defined as 210lbs., giving 22,500 tons) of coal a year

for 60 years, for which he was to receive 4¾d a corf, or 6d a corf

for delivery to specific dwellings. For the cheaper rate, all coal

had to be off-loaded at Cassons Close, and on no account was a coal

merchant to be employed; the purchaser had to make his own

arrangements. [6]

“On Wednesday last the first waggon Load of Coals was

brought from the Pits of Charles Brandling, Esq., down the new Road

to his Staith near the Bridge in this Town, agreeable to the Act of

Parliament passed last Sessions. ― A Scheme of such general Utility,

as to comprehend within it, not only our Trade and Poor, (which

ought to be grand objects of our Concern) but also beneficial to

every Individual within this Town and Neighbourhood: On this

Occasion the Bells were set a ringing, the Cannons of our FORT

fired, and a general Joy appear’d in every Face.”

Leeds

Intelligencer,

26th September 1758.

Around 1807 the wooden tracks began to be

replaced with iron rails to a gauge of 4 feet 1inch.

|

On Wednesday last a highly

interesting experiment was made with a Machine,

constructed by Messrs. FENTON, MURRAY

and WOOD, of this place, under the

direction of Mr. BLENKINSOP, the

Patentee, for the purpose of substituting the agency of

steam for the use of horses in the conveyance of coals

on the Iron-rail-way from the mines of J. C. Brandling,

Esq. at Middleton, to Leeds. This machinery is, in fact,

a steam-engine of four horses’

power, which, with the assistance of cranks turning a

cog-wheel, and iron cogs placed on one side of the

rail-way, is capable of moving, when lightly loaded, at

the speed of ten miles an hour. At four o’clock

in the afternoon, the machine ran from the coal-staith

to the top of Hunslet Moor, where six, and afterwards

eight waggons of coals, each weighing 3¼ tons, were

hooked to the back part. With this immense weight, to

which, as it approached the town, was super-added about

50 of the spectators mounted upon the waggons, it set

off on its return journey to the Coal-staith, and

performed the journey, a distance of about a mile and a

half, principally on a dead level, in 23 minutes,

without the slightest accident. The experiment, which

was witnessed by thousands of spectators, was crowned

with complete success; and when it is considered that

this invention is applicable to all rail-roads, and upon

the works of Mr. Brandling alone, the use of 50 horses

will be dispensed with, and the corn necessary for the

consumption of, at least, 200 men saved, we cannot

forbear to hail the invention as of vast public utility,

and to rank the inventor among the benefactors of his

country.

The Leeds

Mercury, 27th June 1812. |

Following its opening in September, 1758, Brandling’s wagonway conveyed

thousands of tons of coal into Leeds each year. Cheaper coal, based

on more efficient transport, gave Leeds a head start in the newly

developing large-scale industries and the City was to grow into an

important centre for heat-dependant processes, such as metal-working

and brewing; the manufacture of bricks, glass, pottery and tiles;

and cloth-making in steam-powered mills. But the Middleton Railway

was to make its mark in history for another more significant

reason. In 1812 it became the site of the world’s first rack

railway (an idea later exploited on mountain railways, such as that

on Snowden) and of the first commercially viable steam locomotive

(see Chapter 2). Priestly later described it thus:

“BRANDLING’S RAILROAD

31 George II. Cap 22 Royal Assent 9th June 1758.

This railroad proceeds from the extensive collieries,

situate at Middleton, (belonging to the Rev. R.H. Brandling) about

three miles south of the town of Leeds, and terminates at convenient

staiths, near Meadow Lane in the above town. It is three miles in

length, and was constructed under the powers of an act, entitled, ‘An

Act for establishing Agreements made between Charles Brandling, Esq.

and other Persons, Proprietors of Lands, for laying down a Waggon

Way, in order for the better supplying the town and neighbourhood of

Leeds, in the county of York, with Coals.’

There are upon this railway two inclined planes, one

at the southern corner of Hunslet Carr, and the other at Belleisle,

near Middleton, upon which the full descending waggons, regulated by

a brake, draw up the empty ones. It is here worthy of remark, that

it was upon this railway that the powers of the locomotive engine

were first applied in this part of the country, by the ingenious

inventor, Mr. John Blenkinsop, the manager of the Middleton

Collieries.”

Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals,

and Railways,

Joseph Priestley (1831).

Having

seen Blenkinsop’s locomotive at work on

the Middleton wagonway and recognising its potential, George

Stephenson set to work at the Killingworth and Hetton collieries the chain of development that

would eventually lead to the

mainline steam locomotive. In the process he gained valuable experience in

railway construction that he would later apply to the Stockton and Darlington,

the Liverpool and Manchester, and other lines.

――――♦――――

THE SURRY

IRON RAILWAY.

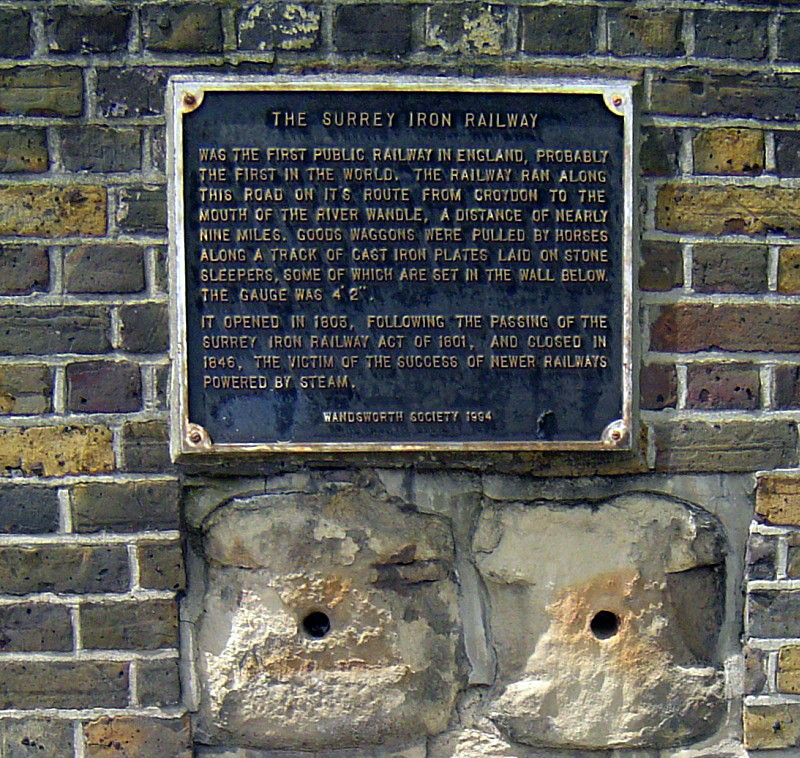

Opened in 1803, the Surrey Iron Railway (SIR)

was a purely commercial venture. In common with many

other wagonways (which is what it was), its purpose was to improve

access to a waterway, in this case to link the industrial areas

extending from Croydon along the Wandle Valley to Wandsworth on the

Thames. However, the SIR was not intended for private use; its enabling

Act was framed in a similar manner to that for a canal, authorising

the Company to provide a track on which the public could convey

their goods for payment of the appropriate toll, but it was left to

the user to arrange conveyance in their own wagons or in those of a

haulage contractor. [7] The SIR was therefore our first public

railway:

“The Surrey Iron Railway promises to be one of the

most useful public works that have late been undertaken for the

improvement of the country. These iron roads are excellent

substitutes for canals, and in some instances superior to them. They

are executed at one third of the expense; and by not obstructing the

natural flow of rivers, all the evils with which the canals are at

times accompanies, are avoided. One horse on an iron railway will do

the work of ten, and the speed with which carriage is performed

exceeds all other modes of conveyance. This iron railway commencing

at Wandsworth, will in all probability be extended to Portsmouth, by

which at all times of the year, and in the severest storms, when

canals are blocked up by ice, stores might be in one day conveyed

from Woolwich Warren to our fleets at Spithead ― a thing which it

has been long in contemplation to effect.”

The Reading Mercury,

1st June 1801.

The original plan had been to link Croydon

and Wandsworth by canal. The civil engineer William Jessop reviewed

the route and while declaring a canal to be feasible he felt it

impractical due to the sole source of water, the River Wandle, being

heavily used by water-driven factories and mills. Instead, he

proposed linking the towns by wagonway along a route running south from

the Thames at Wandsworth, through Streatham, Tooting, Wimbledon, Merton, Mitcham and Beddington to Croydon, where it terminated at Pitlake

Meadow.

Having visited some

existing wagonways, the proprietors decided in favour of Jessop’s

scheme and engaged him to engineer the 9¼-mile line. Jessop’s estimate for the work was

£33,000, which included a substantial basin at Wandsworth capable of

holding 30 barges, and an entrance lock into the Thames. In February 1801 a Bill was laid before Parliament, and later that year the

proprietors of the Surrey Iron Railway

became the first company to obtain an Act with ‘Railway’ in its

title:

[8]

“An

Act for making and maintaining a Railway from the town of Wandsworth

to the town of Croydon, with a collateral Branch into the parish of

Carshalton, and a navigable Communication between the River Thames

and the said Railway at Wandsworth, all in the county of Surrey.”

41 George III. Cap. 33, Royal Assent 21st May, 1801.

In his Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and

Railways of Great Britain (1831), Joseph Priestly provides

information on what the Act contained regarding the raising of

capital and charging of tolls:

“It incorporates the subscribers by the name of ‘The

Surrey Iron Railway Company’ and empowers them to raise, for the

purposes of the undertaking, amongst themselves the sum of £35,000,

in three hundred and fifty shares of £100 each, and, if necessary, a

further sum of £15,000, either amongst themselves, by creation of

new shares or by mortgage of the tolls and rates, and also

authorizes them to take the following:

TONNAGE RATES

For all Goods Wares and Merchandize

whatever carried into or out of the Dock or Basin . . . . 4d per

Ton;

For all Dung carried on the Railway . . . . 2d per Ton, per Mile;

For all Lime stone, Chalk Lime and all other Manure, except (Dung)

Clay, Breeze, Ashes, Sand and Bricks . . . . 3d per Ton, per Mile;

For all Tin, Copper, Lead, Iron stone, Flints, Coal, Charcoal, Coke,

Culm, Fullers Earth, Corn and Seeds, Flour, Malt, and Potatoes . . .

. 4d per Ton, per Mile;

For all other Goods, Wares and Merchandize . . . . 6d per Ton, per

Mile;

Fractions of a Quarter of a Ton to be considered as a Quarter, but

all Fraction of a Mile as a Mile.”

Any person was at liberty to put wagons on the line and to

carry goods within the prescribed rates. The Company was also given

compulsory powers to lease wayleaves across land, and in the event

of differences arising as to price, &c., local commissioners named

in the Act were appointed to meet and determine disputes.

Below the memorial plaque are two

stone-block sleepers from the line.

Such sleepers were in

common use on early railways because they created a clear path

between the lines for horses to walk on, without the risk of

tripping.

Tenders

were invited to build the line, Benjamin Outram and Company [9]

winning the contract at £33,000. Construction progressed quickly,

the contractors being George Leather (father and son) with Outram

supervising the works:

“On Thursday last the lock, canal, and basin, from

which the proposed iron railway is to commence at Wandsworth, was

opened, and the water admitted from the Thames. The first barge

entered the lock, amidst a concourse of spectators, who rejoiced in

the completion of this part of the important and useful work. The

ground is laid for the railway, with some few intervals, all the way

to Croydon, and the undertakers wait only the approach of open

weather to lay down the iron.”

Jackson’s

Oxford Journal,

16th January 1802.

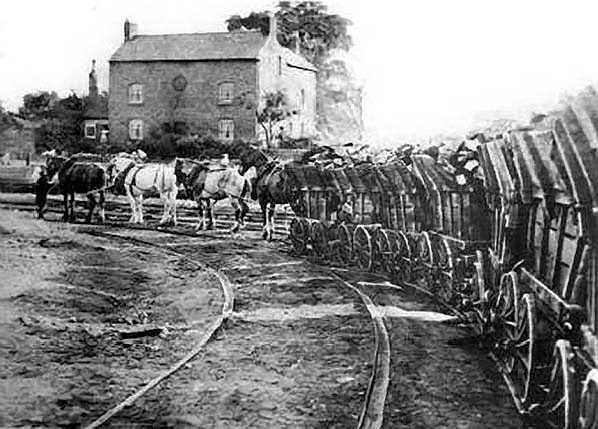

As built, the line was a double track

‘plateway’, the rails being cast iron L-shaped plates mounted on

stone blocks, an arrangement that left space between the tracks for

the horses’ hooves. The wagons had rimless wheels set to a gauge was

4 feet 2 inches and were initially hauled by horses, mules and

donkeys, but donkeys were found to be cheaper and later took over.

The line opened to the public in 1803, to

be followed by the 1¼ mile Carshalton Branch a year later:

“On Tuesday last the Iron railway from Wandsworth to

Crydon was opened to the public for the conveyance of goods. The

Committee went up in waggons drawn by one horse; and to show how

motion is facilitated by this ingenious and yet simple contrivance,

a gentleman, with two companions, drove up the railway, in a machine

of his own invention, without horses, at the rate of 15 miles per

hour. The Committee afterwards dined together at the King’s Arms, in

Croydon, and spent the day with the utmost conviviality.”

The Hampshire Telegraph, 8th August 1803.

In 1805 the Company returned to Parliament

for:

“An Act to enable the Company of Proprietors of the

Surrey Iron Railway to raise a further Sum of Money, for completing

the said Railway, and the Works thereunto belonging.”

45 George III. Cap. 5, Royal Assent 12th March 1805.

. . . . which authorised the Company to

raise a further £10,000, some of which paid for enlarging the

Wandsworth basin. The final cost of the project overall was £60,000, almost

twice the original estimate.

Enthusiasm for the SIR led to the Croydon,

Merstham and Godstone Railway being formed to extend the line to

Reigate, there to exploit the stone and chalk of the area, with the possibility of eventually

reaching Portsmouth:

“An Act for making and maintaining a Railway from, or

from near, a place called Pitlake Meadow, in the town of Croydon,

to, or near to, the town of Reigate, in the county of Surrey, with a

collateral Branch from the said Railway, at or near a place called

Merstham, in the parish of Merstham, to, or near to, a place called

Godstone Green, in the parish of Godstone, all in the said county of

Surrey.”

43 Geo III Cap. 35, Royal Assent 17th May 1803.

But the project was seriously

under-capitalised and despite an application to Parliament for:

“An Act for better enabling the Company of Proprietors

of the Croydon, Merstham and Godstone Iron Railway, to complete the

same.”

46 Geo III. Cap. 93, Royal Assent 3rd July 1806.

. . . . the line only reached Merstham,

which, together with its branches, added a further 16 miles to the

SIR. Jessop was the engineer and Outram’s company was both

civil engineering contractor and supplier of the iron rails. [10]

Neither railway prospered. The Croydon to Merstham line closed in 1838, its trackbed being acquired by the

London and Brighton Railway. It was followed in 1846 by the SIR, its trackbed being sold to local landowners and to the

Wimbledon and Croydon Railway Company. Both

lines were abandoned by Act of Parliament.

Following the opening of

the Merstham line, an interesting article appeared in a number of

newspapers that gives some insight into a wagonway’s carrying

capacity:

“The SURREY IRON RAILWAY being completed, and opened

for the carriage of goods all the way from Wandsworth to Merstham, a

bet was made between two Gentlemen, that a common horse could draw

thirty-six tons for six miles along the road, and that he could draw

this weight from a dead pull, as well as turn it round the

occasional windings of the road. Wednesday last was fixed for the

trial; and a number of Gentlemen assembled near Merstham to see this

extraordinary triumph of art. Twelve waggons loaded with stones,

each waggon weighing above three tons, were chained together, and a horse taken from the timber cart of Mr. Harwood, was

yoked into the team. He started from near the Fox Public-house, and

drew the immense train of waggons with apparent ease to near the

Turnpike at Croydon, a distance of six miles, in one hour and 41

minutes, which is nearly at the rate of four miles an hour. In the

course of this time he stopped four times, to shew that is was not

be the impetus of the descent that the power was acquired ― after

each stoppage he draw off the chain of waggons from a dead rest.

Having gained his wager, Mr. Banks, the gentleman who

laid the bet, directed four more loaded waggons to be added to the

cavalcade, with which the same horse again set off with undiminished

power; and still further to shew the effect of the railway in

facilitating motion, he directed the attending workmen, to the

number of about fifty, to mount on the waggons, and the horse

proceeded without the least distress, and in truth, there appeared

to be scarcely any limitation to the power of his draught. After the

trial the waggons were taken to the weighing machine, and it

appeared that the whole weight was . . . .

[55 tons 6 cwts 2 qtrs].”

The

Morning Post,

5th July 1805.

――――♦――――

THE

STOCKTON AND DARLINGTON RAILWAY.

|

|

|

The Company emblem is

indicative that the Railway was only

partly worked by

steam locomotives

in its early days. |

The transition between the era of the

‘iron railway’ and that of the ‘modern railway’ ― or at least a

railway that, in its essentials, would be recognisable as such

today ― was by no means immediate. The

transitional period began in 1825 with the

opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway and extended to at least

the opening of the Grand Junction and the London and Birmingham lines in 1837 and 1838. Neither was its arrival solely a matter of new

technology, as had largely been the case with earlier

transitions, for with the modern railway came the beginning of railway

administration, of the active marketing of railway services, and

of interworking

between the networks of different railway companies, and all on a grand scale.

The Stockton and Darlington Railway is

sometimes considered to be the beginning of the modern railway era,

but although it incorporated much that had been learned in the

fields of mechanical and civil engineering (mainly in locomotive and

track design), initially it retained many of the features

of the colliery wagonway.

The line was first surveyed [11] by George Overton, a Welsh canal and railway engineer now remembered

mostly for his work in connection with the Pen-y-Darren wagonway, the

site of Richard Trevithick’s steam locomotive experiment of 1804

(Chapter 2). Using Overton’s survey, the proprietors applied to

Parliament for a railway Act in 1819, but their application was

rejected due to the opposition of landowners, Lord Darlington in

particular. Their second application was based on an altered route.

It met

with little opposition, and in 1821 the Stockton and Darlington Railway

Company obtained:

“An Act for making and maintaining a railway or

tramroad from the River Tees at Stockton to Witton Park Colliery

with several branches therefrom, all in the County of Durham.”

l & 2 Geo. IV. C. 44, R.A. 19th April, 1821.

However, Edward Pease, an influential director

of the Company, was unimpressed with Overton and his proposed

route. Influenced by George Stephenson’s

growing reputation, Pease invited him to Darlington where Stephenson arrived on 19th

April 1821 in company with

Nicholas Wood, that being the day on which the Stockton and Darlington Railway Act

received the Royal Assent. At the time, Stephenson was employed constructing a

7-mile wagonway between Hetton Colliery and staithes on the

River Wear.

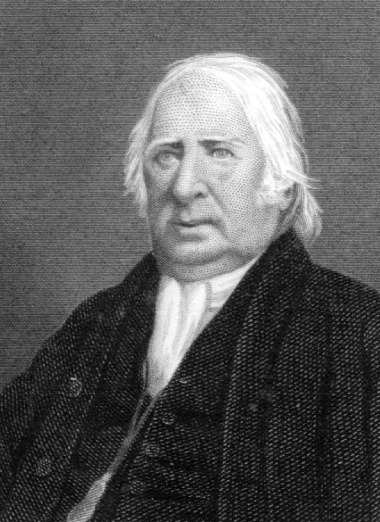

|

|

|

Edward Pease (1767-1858),

Quaker, anti-slavery campaigner

and railway

pioneer ―

“a man of weight, of prudence,

of keen commercial

instincts”. |

The directors’ original intention had been

to work the line with horses, but in the conversation between them

Stephenson suggested that it should be worked entirely by steam.

Pease subsequently visited Killingworth to see the colliery

locomotives at work and was impressed with what he saw. The outcome was

that Stephenson was engaged by the Company to re-survey Overton’s

route. This he shortened by three miles and eased the gradients,

although two substantial ‘inclined planes’ remained. [12] Following

the survey, Stephenson was appointed Engineer to the Company.

Taken together, the changes that

Stephenson proposed ― to which were added the conveyance of

passengers and parcels, both a novelty ― required a further Act of

Parliament, which the Company obtained in 1823 (4 Geo. IV. C. 33,

R.A. 23rd May, 1823). Construction then went ahead, and the Stockton

and Darlington Railway was formally opened on 27th September

1825 to become the world’s first public railway to utilise

steam power. That said, the line was not worked

solely by steam, but also employed horse traction:

“. . . . its promoters had only anticipated the

carriage of 10,000 tons per annum, they had not thought of

passengers, and the locomotive appeared incapable of acquiring

the regularity required by such traffic. They began their work,

therefore, with animal power. Prior to the formation of this

railroad, there had been a coach traffic of fourteen or fifteen

persons weekly: the rail increased it to five or six hundred. Each

carriage was drawn by one horse, bearing, in ordinary cases, six

passengers inside, and from fifteen to twenty outside; ‘In fact,’

says one writer, ‘they do not seem to be at all particular, for in

cases of urgency they are seen crowding the coach on the top, sides,

or in any other part where they can get a footing: and they are

frequently so numerous, that when they descend from the coach and

begin to separate, it looks like the dismissal of a small

congregation.’ The general speed with one horse was ten miles an

hour.”

A History of the English Railway,

John Francis (1851).

In addition to locomotive and horse

traction, there were two steep rope-worked inclines, both powered by a

combination of stationary steam engines and gravity. This

system appears to have been influenced by Stephenson’s

construction of the Hetton Colliery wagonway:

“On the 18th of November, 1822, the Hetton Colliery

Railway, which had been formed under the direction of George

Stephenson, was brought into use, the traffic being worked over five

self-acting inclines and conveyed over other portions of the line by

locomotive and stationary engines. The directors of the Stockton and

Darlington Railway had thus an opportunity of seeing in another part

of the country a successful application of the principles which had

guided George Stephenson in the laying out of their own line.

These principles, deduced from a series of experiments

which he had made in conjunction with Nicholas Wood, were, as stated

by the latter:― (1) On the level or nearly level gradients, horses

or locomotive engines were proposed to be used, a rule being laid

down that, if practicable, the gradients ascending with the load

should not be more than 1 in 300; (2) in gradients descending with

the load, when more than 1 in 30, the use of self-acting planes; and

(3) in ascending gradients with the load, where the gradients did

not admit of the use of horses or locomotive engines, then fixed engines with ropes.”

The North Eastern Railway; its rise and development,

W. W. Tomlinson (1915).

For about five miles at the western end of

the Stockton and Darlington, stationary steam engines were used to

haul trains up the inclined planes at Brusselton and Etherley;

having reached the respective summits, the loaded wagons then descended

by gravity, hauling empty wagons up the incline in the process.

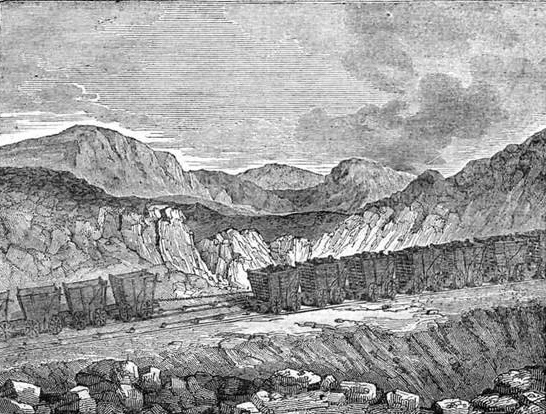

|

|

Inclined plane ― loaded

coal wagons descending

hauling empties up the slope.

|

Horses were then used to haul the wagons between the two inclines. For the remaining 20 miles or so eastwards from Shildon, the line

was at first worked by horses and by locomotives, although in

service the latter proved to be highly unreliable:

“On the 27th of September, 1825, the Stockton and

Darlington line of railway, twenty five miles long, was opened for

public traffic. Twenty miles of this was worked by locomotives and

horses, the powers of each being put thus in close competition. At

this early period of the history of a line of railway, the first

ever laid down on the improved principles as introduced by

Stephenson, and which formed the nucleus of the railway system, the

locomotives employed on it were five in number, four having been

manufactured by Messrs. Stephenson at their factory at Newcastle,

and one by Mr. Wilson of the same town. Such, however, was their

inefficient working condition, that the power of steam was about to

be abandoned and the railway conducted by horses.”

The Steam-Engine, its History and Mechanism,

Robert Scott Burn (1854).

The locomotives that Stephenson built for

the line were equipped with single-flue boilers, which, together

with the lack of an effective blast-pipe, resulted in their

inability to raise

sufficient steam to sustain the effort required to haul their loads. It was not until

Timothy Hackworth took over as locomotive superintendent that steam

traction on the line came to prove itself; nevertheless, horse

traction was not replaced entirely until 1833.

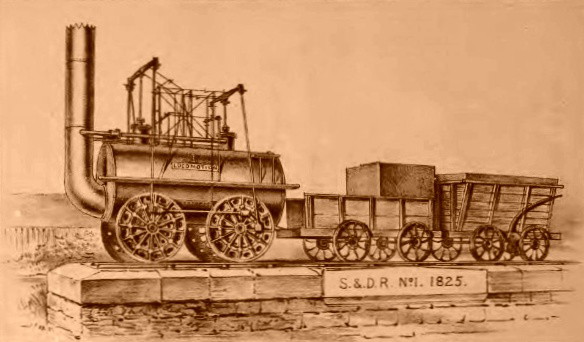

Stephenson’s

Locomotion No. 1, the first locomotive to run on a public railway.

Although authorised in its Act to carry

passengers, the line was built essentially to convey local coal to

the Tees for shipment further afield:

“In making thy survey, it must be borne in mind that

this is for a great public way, and to remain as long as any coal

in the district remains.”

Letter, Pease to Stephenson, 28th July 1821 [13].

Initially, the Railway was operated as a single track toll road; as

with the Surrey Iron Railway, the Company did not operate the

trains. Thus, for payment of the appropriate toll (laid down in the

Act), both steam and horse-hauled traffic could use the line

whenever they wished ― and in an uncontrolled manner that often

resulted in conflict. Only in later years did the Stockton and

Darlington acquire the characteristics of a modern public railway.

Nevertheless, it was a landmark in the use of steam-worked trains on

a public railway, and much was learned from its construction

and operation that was later applied elsewhere.

――――♦――――

THE

CANTERBURY AND WHITSTABLE RAILWAY.

from

The Railways of Great Britain and Ireland

by Francis Whishaw C.E.

London, 1840

The Canterbury and Whitstable was

the first railway in the south of England worked by stationary and

locomotive engines. It was projected by Mr William James, who

also originally proposed the Liverpool and Manchester Railway; but

who like many others spending his time and means for the public

good, died a poor and neglected man. [14]

The first Act of Parliament for the construction of this railway was

passed in 1825, being the 6th of Geo IV chap cxx. Three

additional acts have subsequently been obtained; the first received

the royal assent on the 2d April, 1827, by which the Company were

empowered to raise an additional capital in joint stock of £19,000.

By the second, which received the royal assent on the 9th May 1828,

£21,000 additional; and by the third, dated 21st July, 1835, a

further sum by loan of £40,000.

It [the Railway] was opened to the public on the 3d May,

1830; and although it is of great use to the citizens of Canterbury,

and the district generally through which it passes, it is far from

having answered the proprietors expectations.

When we visited this line in 1831, it was partly worked by fixed

engines, partly by one locomotive engine, [Invicta] and

partly by horses; but in 1839 we found that the locomotive engine

had been dispensed with. [Note]

The course of this line is nearly direct between the station at

Canterbury and the harbour at Whitstable. It is divided into

five planes; the first of which rises from Canterbury for 3,300

yards at the rate of 1 in 46, to the engine station at Tyler’s

Hill. The next plane is also on an ascent, rising at the rate

of 1 in 750 for 1,980 yards to the second engine station at Clow’s

Wood, which is the summit of the line. The line thence

descends for a length of 1,760 yards at the rate of 1 in 31.

For the next 2,200 yards the line is nearly level. Of the two

remaining planes to Whitstable, the first descends at the rate of 1

in 53 for 880 yards; and the second is nearly level being 440 yards

in length. Thus the whole length is six miles.

The principal traffic is in coals, which are brought coastwise to

Whitstable and thence by the railway to Canterbury. Passengers

are also conveyed at a moderate rate of charge; but the receipts on

this account are not considerable.

The fixed engines at Tyler’s

Hill and Clow’s

Wood are two of 25-horse and one of 15-horse power each,

respectively. The ropes used are of 3¼ inches circumference.

The sheeves are of 10 inches diameter, and 8 yards apart.

The way is single throughout; the gauge is 4 feet 8½ inches, and

each side-space 2 feet 7¾ inches wide; the top width of embankments

being 10 feet. The rails are of wrought iron, of light weight,

and are set in chairs with 3 feet bearings; the chairs being spiked

down to cross sleepers of oak.

The line is at present on lease to Messrs Nicholson and Bayliss

Editor's note.

Invicta was built at Newcastle by Robert Stephenson and

Company in 1830, and was the next locomotive built by that eminent

firm after the famous Rocket. The Invicta ran

upon only about a mile of level line of the 6-mile long Canterbury

and Whitstable Railway, the rest of which was worked partly by

horses and partly by ropes worked by stationary steam engines.

|

|

| Invicta, as rebuilt with

single flue boiler, on display at Whitstable Community

Museum & Gallery. |

The major controls, including the regulator, are located about

halfway along the boiler’s

left-hand side. It was operated by a driver, who stood on a

timber footboard mounted above the locomotive’s

rear wheel (as on Locomotion No. 1) and a fireman who stood

in the tender. As originally built, the Invicta, like

the Rocket, was fitted with a multi-tubular boiler which

seems to have answered its purpose sufficiently well, but in about

1838 a single flue boiler after the fashion of earlier engines was

substituted with the result that steam could no longer be kept up,

and Invicta had to be withdrawn from service never to work

again. As the advantage of multi-tube over single flue boilers

were by this time well established, it is difficult to imagine what

gave rise to this retrograde step.

The Invicta has survived and is on display in the

Whitstable Community Museum & Gallery. |