|

NOTES AND

EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

CHAPTER

12

DEVELOPMENT

OF THE STEAM

LOCOMOTIVE (II).

A QUESTION OF MOTIVE POWER

“Apart from three designed by Trevithick,

only 25 other locomotives had been built by 1823 and not one of them

was decisively superior to horse traction. The slow progress in

achieving a decisive breakthrough in the performance of the

locomotive resulted in the Stockton and Darlington Railway using a

mixture of stationary engines, locomotives and horse traction for

working the regular traffic . . . . After the superiority of the

locomotive had been demonstrated on the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway in 1830 the promoters of new lines had little difficulty in

raising the necessary capital.”

The Transport Revolution from 1770,

Philip S. Bagwell (1974).

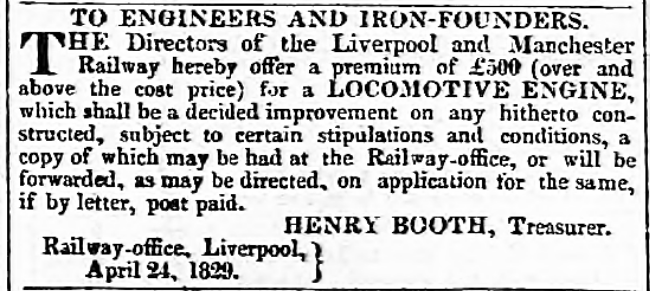

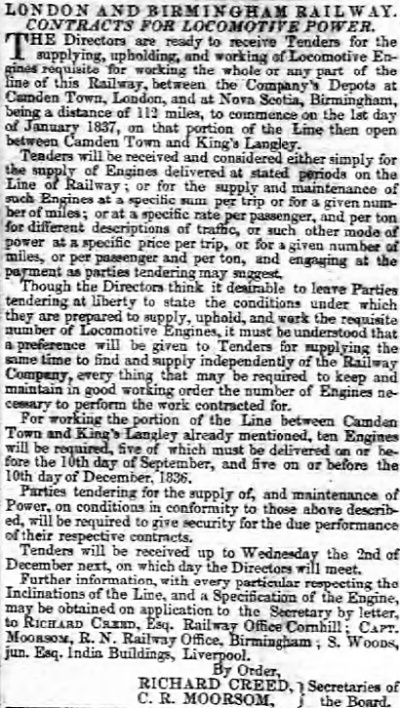

Birmingham Gazette,

Monday, 4th May 1829.

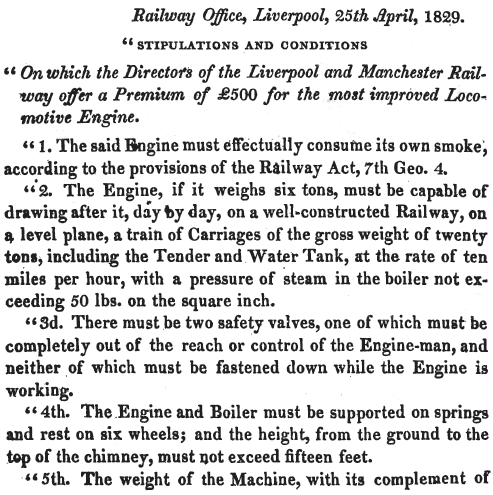

. . . . thus was announced the £500-prize that gave birth to the Rainhill

Trials, one of the most influential events in the history of

transport. The “certain

stipulations and conditions” the advertisement referred to were:

|

|

|

|

|

From A Practical

Treatise on Rail-roads, Nicholas Wood (1838). |

As the Liverpool and Manchester Railway neared completion, its

directors were faced with the decision on how the line was

to be worked:

“At that time the prospects of the

locomotive were most discouraging. The speed of five or six miles

per hour attained on the Killingworth and Darlington lines by no

means justified an enthusiastic support of the travelling engines. It was true that they had not been built with a view to speed, but

for the purpose of obtaining cheap carriage for coals. Indeed, not

many years before, the problem had been to make them move at all. But progression having been accomplished, the next thing was to

increase their powers.”

The Life of Robert Stephenson,

F.R.S., J. C. Jeaffreson (1864).

Steam locomotives had indeed acquired a poor reputation for

performance and reliability, added to which the highly inefficient boilers of the

time wasted large amounts of fuel. On a relatively short colliery wagonway, where

coal was cheap and

plentiful, a heavy fuel consumption was of little consequence, but

elsewhere the fuel bill had to be taken seriously. When

considered together, these factors

meant that locomotives were unlikely to be a practical proposition

for the immediate future, whereas both horse traction and stationary

steam engines

operating cable haulage were well-known quantities. Faced with this

conundrum, a party

of the line’s directors set out to visit the railways in the North-East

to assess the situation for themselves. What they saw merely

demonstrated that for the volume of traffic that they anticipated horse traction was out of the question, but they remained undecided

on whether to adopt

locomotives or cable-haulage.

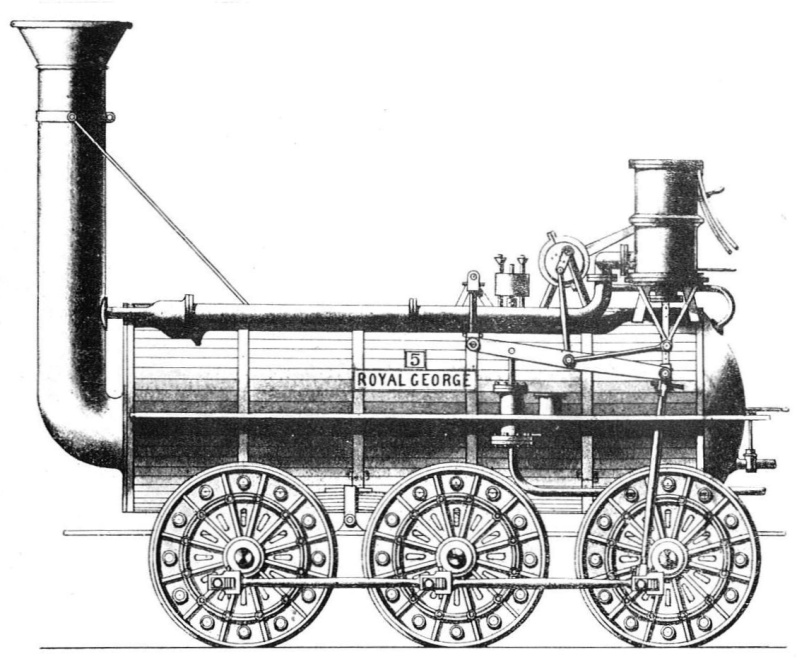

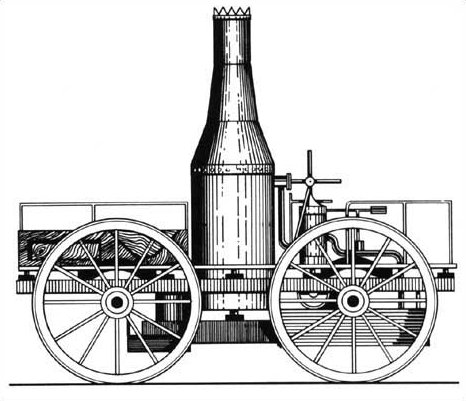

The ‘Royal George’ (1827), Stockton

and Darlington Railway.

Generally considered to be the first

adequate locomotive adapted to the rigours of everyday use,

and the

first to incorporate a correctly aligned steam blastpipe.

In view of their continuing indecision the Board decided to obtain a professional opinion independent

of their own advisors (principally the Stephensons, who were both keen advocates of

steam locomotives). To provide it they

engaged two eminent civil engineers, John Rastrick and James Walker. [1]

In January 1829, the pair set out on a

second tour of the North-East, their primary object being to

establish . . . . The comparative expense of conveying goods upon

a Railway by locomotive and by fixed Engines. [2] During their

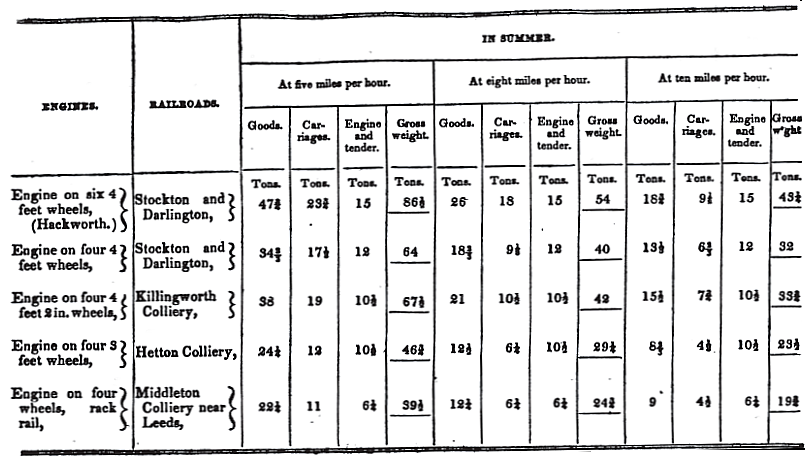

tour, they gathered much information, included in which was an

interesting summary of the loads that locomotives were then capable

of hauling, Hackworth’s Royal George (above) being well

ahead of the field:

A Practical Treatise on

Rail-roads, Nicholas Wood (1838).

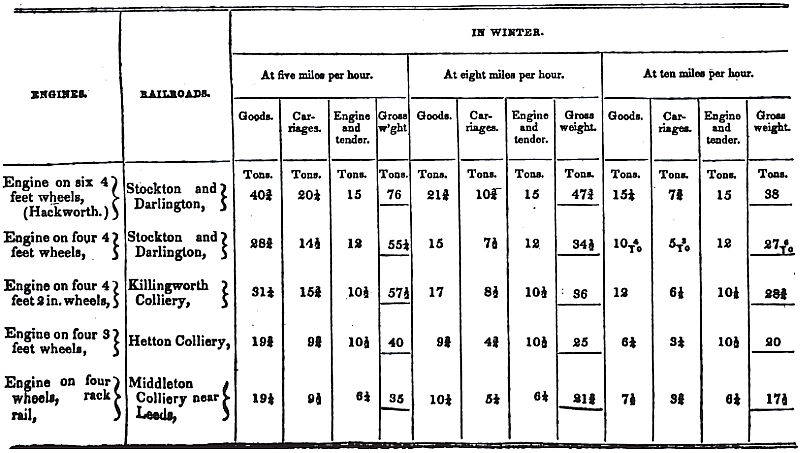

Rastrick and Walker submitted their findings to the Liverpool

and Manchester Board in

March 1829. In their report they provided their principals with a

considerable weight of data and calculations, which demonstrated

that, in terms of the cost of conveying each ton of goods per mile, a system of fixed engines would

be cheaper to operate than locomotives. However, they did acknowledge that the choice between the two forms of

motive power was finely balanced.

In his summary of the study,

Henry Booth, Secretary to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

Company, had this to say:

“The advantages and disadvantages of each

system, as far as deduced from their own immediate observation, were

fully and fairly stated, and in the opinion of the engineers

themselves, were pretty equally balanced. The cost of an

establishment of fixed engines between Liverpool and Manchester,

they were of opinion, would be something greater than of locomotives

to do the same work; but the annual charge, including interest on

capital, they computed would be less on a system of fixed engines

than with locomotives. The cost of moving a ton of goods thirty

miles, that is from Liverpool to Manchester, by fixed engines, they

estimated at 6.40d., and by locomotives at 8.36d., supposing in each

case a profitable traffic both ways.”

The Life of Robert Stephenson,

F.R.S., J. C. Jeaffreson (1864).

Liverpool and Manchester

Railway. Report to the Directors, James Walker (1829).

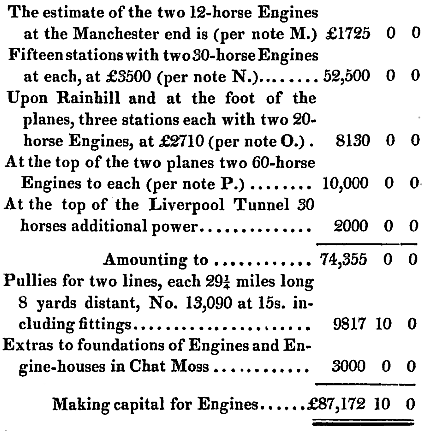

In arriving at their costings, Rastrick and Walker worked on the

basis of the following scheme of stationary engines:

Liverpool and Manchester

Railway. Report to the Directors, James Walker (1829).

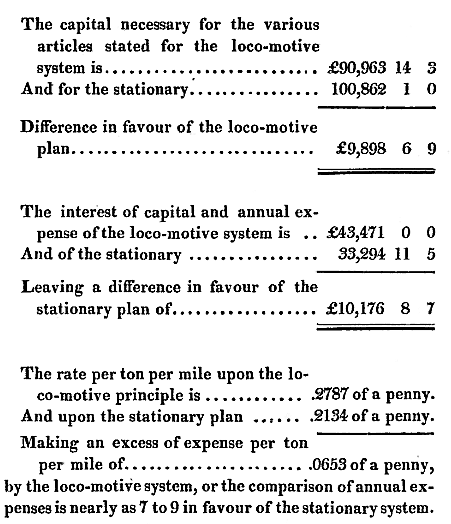

When it came to dealing with the likely fuel cost for operating the

line with locomotives, the

consultants experienced a difficulty:

“As to the consumption of fuel by

locomotive Engines: This article is so cheap in most places where

locomotive Engines are in use, that it is not customary to keep any

accurate accounts of it . . . .”

Liverpool and Manchester

Railway. Report to the Directors, James

Walker (1829).

. . . . added to which was the effect of the significant difference

in the efficiency of locomotive boilers then in use, and hence their fuel

consumption. What figures could be obtained ranged between 1.6 and 3

pounds weight of coal per ton per mile.

However, the pair discovered that engine drivers on the Stockton and

Darlington Railway were required to pay for the coal they

used, which they assumed, not unreasonably, would

encourage them to exercise some economy in its use. The

railway company kept a record of the amount of coal they sold as well as the ton miles their locomotives

ran, which, taken together, suggested a fuel consumption of 2.8

pounds per ton per mile. In their calculations, Rastrick and

Walker reduced this to 2.5 pounds to take account

of known improvements that were then being made in boiler

efficiency, which produced an estimated annual fuel bill of £13,653 for a fleet

locomotives, compared with £3,784

for fixed engines and cable haulage. [3]

In their response to the Rastrick/Walker

report, Robert Stephenson and Joseph Locke conceded that fixed engines were inherently more efficient

than locomotives:

“It is probable that the consumption of

fuel by Locomotive Engines will always be greater than by Fixed

Engines. In the latter the heat may, without inconvenience, be

applied in the best possible manner, and care taken to prevent loss

of heat by radiation; but lightness, compactness, and simplicity

being absolutely necessary in Locomotives, we are compelled to adopt

less economical methods of applying the fuel.”

Observations on the comparative

merits of locomotive & fixed engines,

Robert Stephenson and

Joseph Locke (1830).

A further point raised by Rastrick and Walker was that even if locomotives were to be used,

they would be unable to cope with the two 1:96 gradients at Rainhill and Sutton,

which would at any rate require cable haulage. Subsequently, however, the Rainhill

Trials demonstrated that locomotives were capable of handling such

gradients unassisted, although cable haulage was inevitable on the

1:48 gradient to the dockside at Liverpool.

Despite its apparent cost advantage, some points of interest emerged

from the report that underlined the weaknesses of the cable system. The first concerned

the

initial capital outlay, where the ready ability to increase

the number of locomotives by incremental steps, in line

with traffic growth, gave locomotives a distinct advantage over the

inflexible alternative:

“If the quantity of goods be small or

uncertain, it would require no calculation to determine that the

locomotive system is the cheaper, because by it you increase the

power by an increase of the number of Engines, and can therefore

always proportion the power to the demand, while upon the stationary

system it is necessary first to form an estimate of the probable

trade, and then at once to establish a line of Engines, Ropes, &c.

from end to end, that shall be complete and fully equal to it. There

is therefore in the locomotive system an advantage in this respect,

that the outlay of capital may at the first be much less than by the

other system.”

Liverpool and Manchester

Railway. Report to the Directors, James

Walker (1829).

Another factor against cable was the higher impact on

traffic flow, compared with locomotives, resulting from a failure in

any of the sections of the line of

either the cable ― the most likely cause ― or the power

plant:

“The probability of accident upon any

particular part of the system is, I think, less with the stationary

than with the locomotive; but in the former the effects of an

accident extend to the whole line, whereas in the latter they are

confined to the particular Engine and its train, unless they happen

to obstruct the way and prevent others from passing. The one system

is like a number of short unconnected chains, the other resembles a

chain extending from Liverpool to Manchester, the failure of one

link of which would derange the whole.”

Liverpool and Manchester

Railway. Report to the Directors, James

Walker (1829).

But perhaps the most telling blow against cable was the recognition

that, after many years of development, principally under Watt, the

stationary steam engine had reached a relative plateau of refinement compared with

the steam locomotive, where there lay much unexploited potential:

“I have reasoned upon the Engines generally

in their present state, but it is proper to say that improvements

have, since my survey in 1824, been made in them, and that the

attention at present bestowed upon the subject will in all

probability still do much for them. The Engine made by Mr. Rastrick

is different from that by Mr. Hackworth in the form of the flue and

otherwise; Mr. Stephenson’s is different from both, and every new

Engine he makes, differs in some respects from the one preceding

it.― Since 1824 the diameter of the wheels has been increased,

wrought iron tire substituted for cast, spring safety-valves have

been introduced, and the Engine itself is supported upon a spring

carriage. I think all these decided and great improvements, and in

estimating the question generally it is fair to anticipate others.

It is true that improvements in the stationary system may also be

expected, but not, I should say, to the same extent.”

Liverpool and Manchester

Railway. Report to the Directors, James

Walker (1829).

No doubt influenced by these last three arguments and, despite their consultants’

overall recommendation, the Board remained

undecided on what motive power to adopt, although by now the steam

locomotive had gained a majority of supporters providing it

could be shown to be up to the job. Thus, the decision was taken to hold a competition.

――――♦――――

THE RAINHILL TRIALS.

“Considering the very important

conclusions, which have resulted from the competition, induced by

the offer above noticed, the very rapid improvement which it

produced in these engines, forming not only a new era in their

history, but in the importance of railway communication in general;

we shall make no apology, in giving a brief outline of the

proceedings, and of the various improvements effected by this

competition of talent.”

A Practical Treatise on

Rail-roads, and Interior Communication, Nicholas Wood (1838).

The trials were to take place on a section of level track, about

1¾-miles long, at Rainhill, a few miles to the east of Liverpool.

News of the event caused much excitement. Supporters of the steam

locomotive hailed it as an opportunity to create a great change in

internal communications, the Company’s shareholders saw it as a

scheme from which profit (or loss, depending on point-of-view) would

emerge, the canal companies saw it as a threat to the wellbeing of

their businesses ― in this they were correct ― and the public looked

on in anticipation of great entertainment and spectacle:

“On the morning of the 6th the ground at

Rainhill exhibited a very lively appearance; several thousand

persons were collected from all parts of the country, amongst whom

were several of the first Engineers of the day. A commodious tent

had been erected for the accommodation of the ladies, which was

graced by the beauty and fashion of the surrounding neighbourhood;

the sides of the race ground were lined with carriages of all

descriptions;― in short, the tout ensemble exhibited as much bustle

and excitement as if the great St. Leger had been about to be

contested.”

Observations on the comparative

merits of locomotive & fixed engines,

Robert Stephenson and

Joseph Locke (1830).

The competition was set to commence on the 6th October 1829. The three

judges were to be John Rastrick (civil engineer), Nicholas Wood

(viewer at Killingworth Colliery and writer on locomotive

engineering) and John Kennedy (a Manchester industrialist). Their

first task was to refine the competition rules:

“The original stipulations of the Directors

containing no regulations as to the mode of trying the powers of the

different engines, the judges determined, that in order to ascertain

the comparative merit of each they should be subjected to the

following practical test. And in consequence, a card, containing the

following regulations, was distributed to the different

competitors.”

A Practical Treatise on

Rail-roads, and Interior Communication,

Nicholas Wood (1838).

Much of what then took place during the Rainhill Trials is beyond

the scope of this chapter (some press reporting

of the event is reproduced at

Appendix I). Suffice it to say that of the six competition entries,

three did not compete or failed to meet the entry requirements; these were

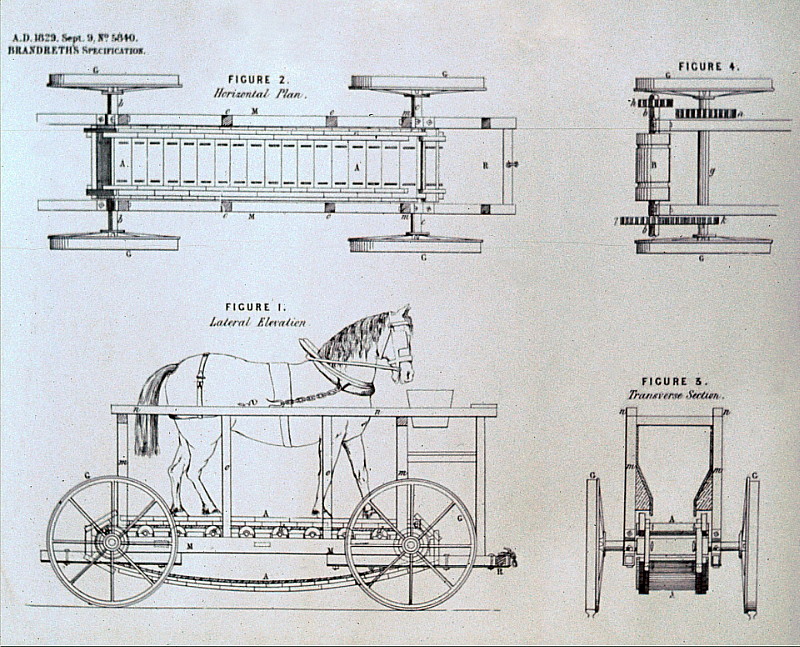

the Manumotive, a type of rail carriage operated by two men, entered by Ross Winan; Thomas Brandeth’s Cycloped, which

was powered by two horses walking an endless belt; and Timothy

Burstall’s Perseverance, which looked similar to Ericson’s Novelty, but there the comparison ends,

for it failed to reach the stipulated minimum speed of 10 m.p.h.

The Cycloped

Perseverance.

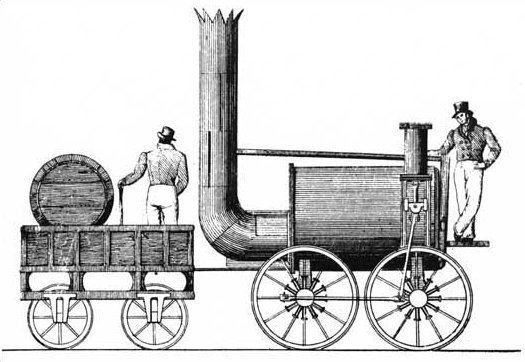

Of the remaining three entries, each being steam powered, only the Stephensons’ Rocket

completed the trials successfully. Timothy Hackworth’s

Sans Pareil [4] suffered boiler failure and the Novelty, entered

by Messrs. Ericsson and Braithwaite, was withdrawn following

a burst steam joint.

Although

Sans Pareil and Novelty [5] represented cul-de-sacs

in the evolution of mainstream steam locomotives, it worth saying something about them.

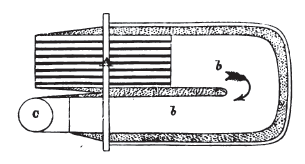

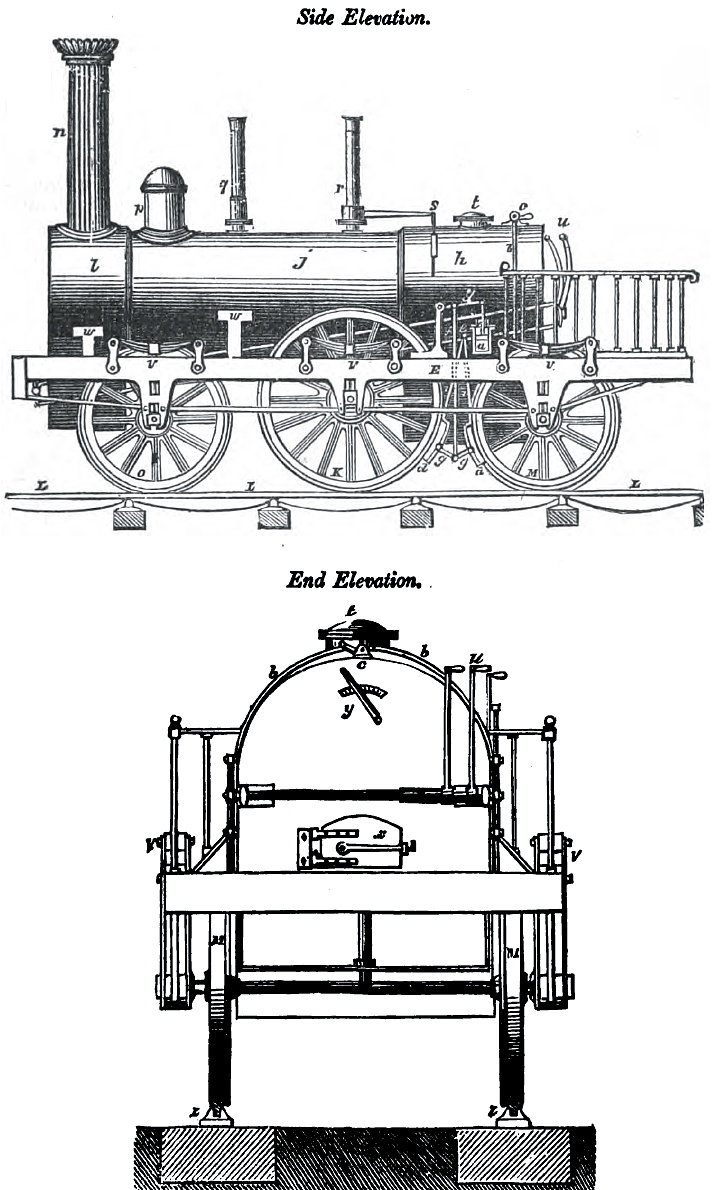

|

|

|

|

|

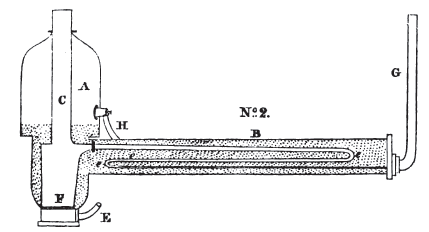

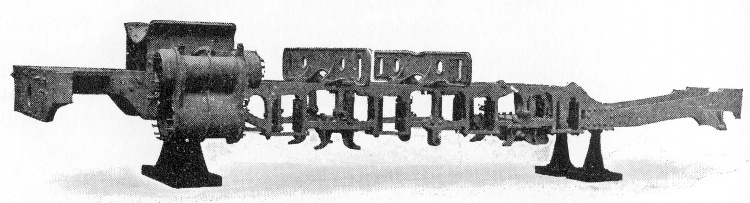

Timothy Hackworths San Pareil and

its return-flue boiler.

'C' marks the chimney, the parallel lines represent the

grate for the furnace. |

|

|

|

A replica of Timothy Hackworth’s

Sans Pareil on display at the

National Railway

Museum, Shildon. |

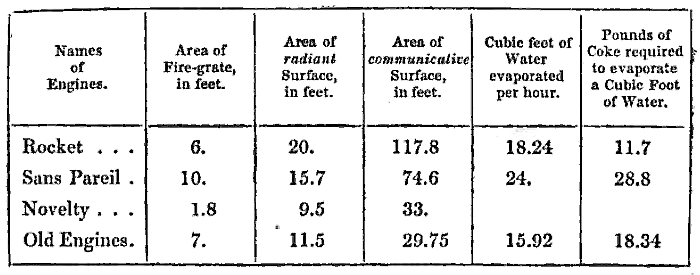

Sans Pareil (“without equal”) was a scaled-down version of Hackworth’s

Royal George. Fitted with wooden-spoked wheels (4 feet 6 inches

diameter) to save weight, the locomotive was powered by vertical cylinders

(7 inches diameter by 18 inches) that gave it the uncomfortable

rolling motion typical of its type. This instability would have limited its

in-service speed for passenger traffic (on the fifth trip of the

Trials the locomotive averaged 22.7 m.p.h., its best run) and its

vertical cylinders would probably have resulted in significant

hammer-blow to the track. Steam was produced in a

return-flue boiler (4 feet 2 inches diameter by 6 feet), the blast

being so fierce that it ejected a great deal of partly burned fuel

from the chimney resulting in heavy fuel consumption. Whereas the Rocket required 11.7

pounds of

coke to convert a cubic foot of water into steam, Sans Pareil

required 28.8 pounds:

The Engineer’s and

Mechanic’s Encyclopædia, Luke Hebert

(1836).

During Sans Pareil’s second appearance

in the competition, her boiler feed pump failed, the

level of water in

the boiler fell below the safe limit and the consequent increase in

temperature melted the fusible plug. Hackworth’s appeal to the judges for further time for

repairs was declined on the grounds of exceeding the

stipulated weight, which, together with the heavy fuel consumption,

precluded the judges from recommending the locomotive to the Company.

Nevertheless, Sans Pareil had a long life. After the trails she was bought by the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway and later sold to the Bolton and Leigh

Railway. In 1837, larger cylinders were fitted and her

wooden-spoked wheels replaced with cast-iron. In 1844, she was moved to the Coppull

Colliery near Chorley, turned into a stationary engine

and used to drive pumping and

winding equipment. Finally, in 1863, Sans Pareil was presented to the Patent Office Museum

(now the Science Museum), and later transferred to the

care of the National Railway Museum at Shilden where she is now on

display.

Overall, Sans Pareil was outmoded; whereas the Rocket

lay at the start of the evolutionary line that led to the

mature steam locomotive, San Pareil lay at the end of the

first era of locomotive development reaching back to Trevithick’s

Catch-me-who-can, to which she bore some resemblance.

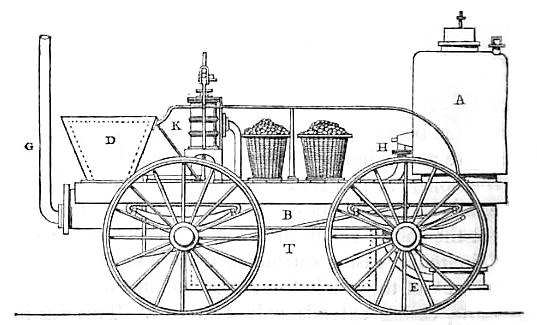

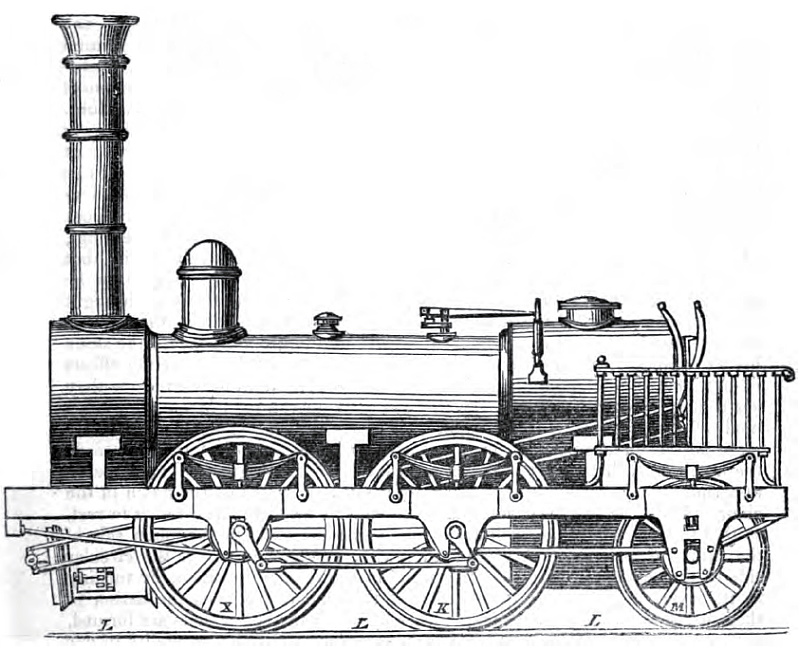

Braithwaite and Ericson’s

Novelty.

The Novelty represented what might best be described as an

interesting prototype, at a

time when the form and layout of the railway locomotive’s basic

components had yet to be settled:

“Messrs. Braithwaite and Erickson’s engine,

the ‘Novelty,’ is of a different principle, the air being driven or

forced through the fire by means of a bellows. The accompanying

drawings will shew the general construction of this engine, and more

particularly the generator, or mode of raising the steam, which

constitutes its prominent peculiarity.”

A Practical Treatise on Rail-roads,

Nicholas Wood (1836).

The storage of fuel on the footplate and water in a well between the

wheels (viz. letter ‘T’ above) placed

Novelty in the category of what were later classed as ‘tank’

engines ― as, indeed, was Burstall’s Perseverance. Judging

from contemporary reports there can be little doubt that

Novelty was the decided favourite among the crowd:

“The great lightness of this

engine, (it is about one half lighter than Mr. Stephenson’s) its

compactness, and its beautiful workmanship, excited universal

admiration; a sentiment speedily changed into perfect wonder, by its

truly marvellous performances. It was resolved to try first its

speed merely; that is at what rate it would go, carrying only its

compliment of cote and water, with Messrs Braithwaite and Erickson

to manage it. Almost at once, it darted off at the amazing velocity

of twenty-eight miles an hour, and it actually did one mile in the

incredibly short space of one minute and 53 seconds. Neither did we

observe any appreciable falling off in the rate of speed; it was

uniform, steady, and continuous.”

Mechanics’ Magazine,

Vol. 12 (1830).

|

|

|

Bell cranks being used

to convert vertical to horizontal thrust. |

In common with Sans Pareil, the drive in Novelty was

from vertically mounted cylinders. However, unlike Sans Pareil,

in which the vertical

cylinders were connected directly to the crankpins, the drive on

Novelty was via bell-cranks. These worked horizontal rods

connected to the cranked front axle, an arrangement that enabled a

leaf-spring suspension to be provided despite the locomotives’ cylinders

being vertically

aligned. Only the front axle was connected to the cylinders,

but the design did provide for both axles to be coupled using chain

drive.

As Wood observed, the boiler was the locomotive’s “prominent

peculiarity”, having the appearance at first sight of a vertical

boiler. In fact the greater part of the boiler barrel extended

horizontally under the locomotive. This contained an S-shaped flue,

which carried the combustion gases from the furnace to the chimney at

letter ‘G’. Fuel was fed into the furnace (letter ‘F’ below) down a tube

(letter ‘C’), which passed through the boiler barrel (letter ‘A’), a method

later adopted by Sentinel in their steam wagons and shunting engines. In his design, Ericson bypassed the need for a blast

pipe by using forced draught, provided by axle-driven bellows, which

entered underneath the fire at letter ‘E’. Spent steam was

exhausted directly into the atmosphere.

The Novelty’s boiler.

Although withdrawn from the trials due to boiler failure,

Novelty performed more successfully than San Pareil. The

first day of the trials was taken up with some demonstration runs. According to the Morning Post (9th October 1829), “the

speed of all the other locomotive steam-carriages on the course was

far exceeded by that of Messrs. Braithwaite and Co.’s beautiful

engine from London. It shot along the line at the amazing rate of

thirty miles in the hour.” On the second day of the Trial, the

locomotive ran under test conditions:

“‘The Novelty’ engine of Messrs.

Braithwaite and Ericsson was this day tried with a load of three

times its weight attached to it, or 11 tons 5 cwt.; and it drew this

with ease at the rate of 20¾ miles per hour; thus proving itself

to be equally good for speed as for power. We took particular notice

to day of its power of consuming its own smoke, and did not any time

observe the emission of the smallest particle from the chimney.”

Mechanics’ Magazine,

Vol. 12 (1830).

Novelty next appeared on the fifth day of the trials, but did not

run under test conditions. During the morning the failure of some

pipework required repair, but the locomotive reappeared in the afternoon,

at the conclusion of which:

“Another carriage with seats for the

accommodation of passengers, was now substituted for the loaded

waggons attached to ‘The Novelty,’ and about forty-five ladies and

gentlemen ascended to enjoy the great novelty of a ride by steam. We

can say for ourselves that we never enjoyed any thing in the way of

travelling more. We flew along at the rate of a mile and a half in

three minutes; and though the velocity was such, that we could

scarcely distinguish objects as we passed by them, the motion was so

steady and equable, that we could manage not only to read but write

. . . .”

“. . . . A fresh pipe had, it appeared,

been substituted for the one which failed on the preceding trial;

one or two other parts of the machinery that were in a faulty state,

had also been renovated; but the engine, with the exception of some

of the flanges of the boiler being as Mr. Ericsson expressed it,

rather green, was pronounced in a working state . . . . The engine

now started to do the 70 miles for a continuance; but just as it had

completed its second trip of three miles, when it was working at the

rate of 15 miles an hour, the new cement of some of the flanges of

the boiler, yielded to the high temperature to which it was exposed,

and the spectators had again the mortification to hear it announced

that it was, under these circumstances, impossible the trial could

go on.”

Mechanics’ Magazine,

Vol. 12 (1830).

And that concluded the Novelty’s appearance at the Rainhill

Trials. In their account of the event, Messrs. Stephenson and Locke

give a more detailed analysis of the boiler failure:

“The first trip of 3 miles was performed in

16’ 43” which is at the rate of 10¾ miles an hour. In the second

trip the pipe which conveys the heated air from the furnace through

the horizontal boiler collapsed, and the steam, forcing its way into

the fire place, was evolved from the bottom of the furnace into the

atmosphere. This failure was at the time attributed to the yielding

of a ‘green joint,’ and was considered as such by the Judges; but

having seen the pipe when it was taken out, we feel convinced that

its failure alone was sufficient to account for the accident,

without the addition of any joint giving way.

The ‘Novelty’ was then withdrawn and Mr. Hackworth requested that he

might be allowed another trial. The Judges refused, on the ground

that his Engine was not only above weight, but that it was on such a

construction as they could not recommend to the Directors of the

Company.”

An Account of the

Competition of Locomotive Engines at Rainhill,

Robert Stephenson and Joseph Locke (1830).

A replica of Novelty.

Although in some ways an ingenious design, a locomotive of

Novelty’s design could not have been scaled up sufficiently to meet the more

demanding loads

that locomotives would shortly be called upon to haul, and over

greater distances. Furthermore,

the double-return boiler flue would have been impossible to clean

unless it had been constructed in sections to permit dismantling,

and only then with difficulty.

Following the Rainhill Trails, the locomotive ran experimentally on

the line before being transferred to the St. Helens and Runcorn Gap

Railway, where in 1833 she received a new boiler and cylinders. In

1838, Novelty is known to have been used on the construction

of the North Union Railway, after which she disappears from history.

Having met the competition criteria,

the £500 prize was shared between Henry Booth, on account of his

contribution to the Rocket’s boiler design, and the locomotive’s

designers and builders, the Stephensons. Had the Novelty not

suffered boiler failure, the outcome of the competition might have

been different, despite that locomotive’s unsuitability as a platform

for future development.

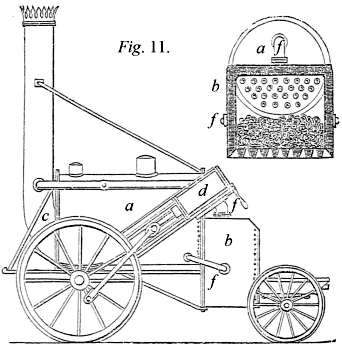

The Rocket, together with a

cross section of her firebox.

See also

Appendix II.

|

Built to compete in the

Rainhill Trials, under test Rocket beat its competitors

with its top speed of 29 mph and better reliability,

thereby confirming its designer, Robert Stephenson, as

one of the premier mechanical engineers of his age. |

“The furnace at A is a square box,

about 3 feet wide and 2 feet deep. This furnace has an external

casing, between which and the fireplace there is a space of 3 inches

filled with water, and communicating by a lateral pipe with the

boiler. The heated air, &c. from the furnace passes through

twenty-five copper tubes, 3 inches in diameter, arranged

longitudinally on the lower half of the boiler, and then enters the

chimney C. D represents one of the two steam

cylinders, which are placed in an inclined position on each side of

the boiler, and then enters the chimney C. D

represents one of the two steam cylinders which are placed in an

inclined position on each side of the boiler, and communicating by

their piston rods, through the media of connecting rods E, motion to

the running wheels. P G are safety valves; E is one of

two pipes on each side of the boiler, by which the eduction steam

from the cylinders is thrown into the chimney, and by the exhaustion

thus caused in the latter, producing a rapid draft of air through

the furnace. At M is exhibited part of the tender, which

carries the fuel and water for the supply of the engine.”

A Practical Treatise on

Rail-roads and Locomotive Engines, Luke

Hebert (1837).

The Rocket was built by Robert Stephenson & Co. at the firm’s

Newcastle-upon-Tyne works (see

Appendix II. for technical details). Although lack of hard

evidence makes it impossible to say who designed the locomotive, it

was probably a collaborative effort. The locomotive brought together a number of

engineering features ― some new, some existing ― which, taken together, represented a step change in locomotive design,

on the back of which further important developments were soon to

follow.

The

reasons for the Rocket’s high performance during the Rainhill

Trials can be attributed to a separate firebox, multiple fire-tube boiler and blastpipe,

which,

acting together effectively, resulted in material

improvements to the locomotive’s steam-raising ability and thermal

efficiency, while moving the connecting rods towards the horizontal

improved its suspension:

The principle of the fire-tube

locomotive boiler.

Combustion takes place in the firebox, the hot gases then passing

through the boiler to the smoke box

along numerous fire-tubes.

|

|

|

The Rocket showing

(top right) firebox,

water jacket and fire tubes. |

Separate firebox. In locomotive designs

predating Rocket, the furnace was located

at one end of the boiler flue. Early attempts to use a blast pipe to intensify the fire

when the locomotive was under load often created such a strong current of air through the fire,

that it was torn, causing large amounts of incompletely burnt fuel to be

expelled along the flue and up the chimney. Such was the experience with

the Sans Pareil

during the Rainhill Trials, which in part accounted for her very

heavy fuel consumption. The introduction of the

external firebox in the Rocket, provided a separate combustion chamber of larger

volume and grate area that had been possible when the fire was

confined within the boiler flue. The result was more complete

combustion, which was further improved following the invention of

the firebrick arch (attrib. Griggs

ca. 1856) shown in the drawing above [6]. Furthermore,

because the firebox was shrouded in a

water-jacket (except at its base where the grate bars were located),

some 20 square feet of water was exposed to the most

intense heat:

“The area of surface of water, exposed to the radiant heat of the

fire, was 20 square feet, being that surrounding the fire-box or

furnace; and the surface exposed to the heated air or flame from the

furnace, or what we shall call communicative heat, 117.8 square

feet; the area of the grate bars being 6 square feet. The end view

[adjacent drawing], will shew the disposition of the tubes in

the end of the boiler, with the fire box surrounding the end.”

A Practical Treatise on

Rail-roads, Nicholas Wood (1838).

Cool water entered the firebox jacket from the bottom

of the boiler through pipes on either side, while hot water left the

top of the jacket through a further pipe to the top of the boiler,

thus allowing thermal circulation between the two.

Multiple fire-tube boiler. Twenty-five

3-inch diameter tubes conveyed the combustion gases from the furnace

through the boiler. This arrangement replaced the single or return

flue (or in the case of the Lancashire Witch, parallel flues)

of earlier locomotive boiler designs, and greatly increased the

heating area to which the water in the boiler was exposed.

Multiple fire-tubes gave the boiler a far greater steam-raising

capacity ― thus avoiding a problem suffered by early locomotives,

which often ran out of steam and had to halt until boiler

pressure was restored ― and by utilising more of the heat to produce

steam, rather than wasting it up the chimney, less fuel was used per

cubic foot of water evaporated:

“In the Rocket the surface exposed to the

radiant heat of the fire compared with the area of the fire grate is

as 3⅓:1, while in the Sans

Pareil [return-flue boiler] it is only 1½:1, the same

proportion as in the old engines. In the Rocket, the surface exposed

to the heated air and flame, compared with the area of the

fire-grate, is as 19⅔:1; while

in the Sans Pareil, the proportion is only 7½:1.

The bulk of air passing through the tube of the Sans Pareil, at its

exit into the chimney, is 176.7 square inches, the exposed surface

being 47.12, or 3.8:1 nearly; while, as before stated, the bulk of

air passing through the tubes of the Rocket is 176.7 inches, or

precisely that of the Sans Pareil, while the surface exposed is

235.6 inches or 1⅓:1. These will

sufficiently account for the great difference in the evaporating

powers of the two engines, and also in the economy of fuel; the

Rocket requiring only 11.7 lbs to convert a cubic foot of water into

steam, while the Sans Pareil required 28.8 lbs.”

A Practical Treatise on

Rail-roads, Nicholas Wood (1838).

The multiple fire-tube boiler became a standard feature in

locomotive boiler design, but who can claim credit for its invention

is uncertain. Although Henry Booth is credited with suggesting its

use to George Stephenson, the French Engineer Marc Seguin

(1786-1875) patented the idea in 1827 and in 1829

built a locomotive that utilised it. The English inventor James

Neville is another claimant, while in the U.S.A. John C. Stevens

patented a water-tube boiler in 1803.

Blastpipe. In early

locomotives back to the time of Trevithick, it had been observed

that by turning the exhaust steam from the locomotive’s cylinders up

the chimney, a partial vacuum was created in the base of the chimney that air

rushed in to fill through the furnace grate and the boiler flue. This

inrush of air fed more oxygen to the fire, thereby intensifying it, a

beneficial effect and one that increased in proportion to the load on the

locomotive. However, it was not until the

introduction of the separate firebox in combination with the multitubular boiler

that the blastpipe became really effective, and a standard feature

in locomotive design.

Inclined cylinders. Moving the Rocket’s cylinders from

the vertical position adopted on most old locomotives ― Trevithick’s

early road and rail locomotives being notable exceptions ― to

35º to the horizontal, allowed

spring suspension to be installed, which improved the distribution

of the locomotive’s weight on the track. Shortly after Rainhill locomotives

appeared with their cylinders installed near to the horizontal,

which together with spring suspension became standard practice.

――――♦――――

DEVELOPMENTS FOLLOWING

THE RAINHILL TRIALS

The Northumbrian, Robert

Stephenson & Co. 1830.

Following the Rainhill Trials, almost a year elapsed until the

official opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway took place on the 15th

September, 1830. In the intervening period, Robert Stephenson & Co.

built seven locomotives for the Railway on similar lines to the

Rocket, one being the Northumbrian pictured above. These locomotives [7] differed from the Rocket

in several ways. They were at least 3 tons

heavier, but the most significant change was to the water

jacket/firebox, which was integrated with the boiler. With the

addition of a separate smoke box, these became standard design

features in

locomotive boilers for the remainder of the steam traction era. Other features built in to this ‘improved Rocket class’ were

changes to the firetubes (reduced in size from 3 inches in the

Rocket to 2 inches and increased in number from 25 to 90) and a

reduction in the angle of the cylinders to near the horizontal. Apparently in the Rocket . . . .

“The steep inclination of the outside

cylinders caused the pistons to lift and depress the engine upon the

springs at every double stroke, and at moderately high speeds the

unsteadiness thus occasioned was very considerable. Timothy

Hackworth appears to have been the first to decide upon the

arrangement so widely adopted afterwards, for securing steadiness at

high speeds ― to wit, horizontal inside cylinders and a cranked

driving axle.”

Locomotive Engineering, and the

Mechanism of Railways: Vol. 1,

Zerah Colburn, Daniel Kinnear

Clark (1871).

Purpose-built tenders also made their first appearance, and both

locomotive and tender acquired buffers ― leather stuffed with horse

hair.

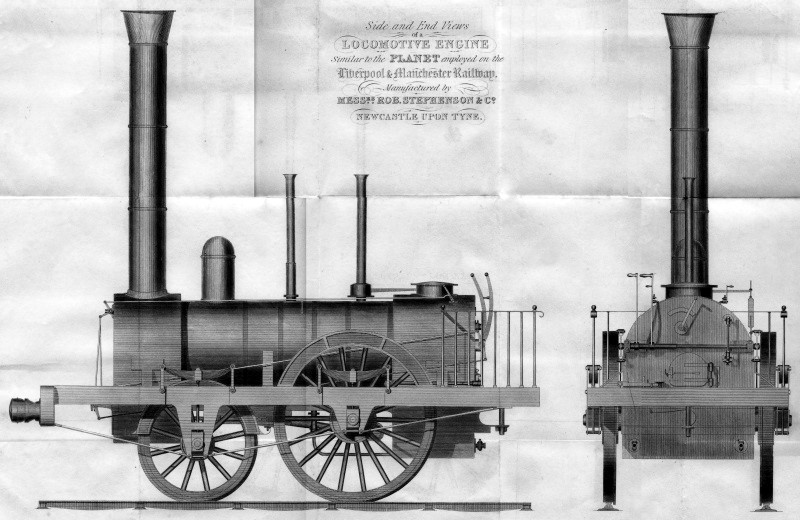

The Planet represented the next locomotive type to emerge

from the works of Robert Stephenson & Co. Not only did it give its

name to the 2-2-0 wheel arrangement, but it became the first design to

be built in quantity and to acquire something approaching the outward appearance of the

steam locomotive in its maturity. Although the Planet represented a further step change in locomotive design, in common

with the Rocket before it most of its refinements

were a bringing together of existing ideas enhanced with suggestions made by

others.

Planet-class

locomotive, Robert Stephenson & Co., 1830.

“The improvements which had been made in

the ‘Planet’ were very conspicuous. They were, in fact, the

combination in one engine of what had previously been known; viz.

the blast pipe, the tubular boiler, the horizontal cylinders inside

the smoke-box, and the cranked axle, together with a fire-box firmly

fixed to the boiler. The ‘Rocket’s’ fire-box was only screwed

against the boiler, allowing a great leakage of air which had not

passed through the fire.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Peter LeCount (1839).

“Since

the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester line, experience has

suggested a great variety of improvements, which have considerably

increased the power and speed of the engines;― of these the

following are the principal. The inclosure of the boiler

within wood, to prevent the radiation of heat;― the removal of the

cylinders from the exterior of the boiler to within a casing or

chamber which was kept warm by its proximity to the boiler, and by a

current of heated air from the boiler tubes;― the alteration in the

situation and motion of the piston rods from the exterior of the

wheel to beneath the boiler, and their connexion with two cranks

placed at right angles on the axles of the great wheels;― and the

production of a powerful draught, by forcing the steam which has

worked the pistons through an orifice up the chimney. By all

these improvements the three following important results are

obtained. 1st.― The unlimited power of draught in the furnace by

projecting the waste steam into the chimney;― 2nd. the unlimited

abstraction of heat from the air passing through the furnace;― and

3rd, keeping the cylinders warm, by immersing them in the chamber

under the chimney.”

Osbornes’

Guide to the Grand Junction, or Birmingham, Liverpool, and

Manchester Railway,

E. C.

Osborne (1840).

Rocket-type locomotives had an 0-2-2 wheel arrangement; the

smoke box was positioned above the driving wheels, while the heavier

firebox sat over the trailing wheels. In the Planets, the

position of the axles was reversed to give a 2-2-0 wheel arrangement. [8] This resulted in more weight being placed over the driving wheels,

which in turn gave more adhesion than in the

Rocket-class. The cylinders, which were almost horizontal, were placed inside the frames where they drove a cranked

axle, a layout that was to be followed in many other designs

throughout the steam era. However, the cranked axles of the day were

prone to failure due to difficulties in their manufacture; were a

fracture to occur, a locomotive could collapse on its broken axle. Stephenson took this risk into account by providing the Planets

with double frames; not only was the engine built around a solid

wooden frame reinforced with iron plate ― visible in the drawing

above holding the external bearings ― but a sub-frame was provided,

the driving wheels being mounted on two sets of bearings between the

two. Thus, were the cranked axle to fail, the driving wheels would

remain held in place.

The Planets also incorporated Richard Trevithick’s final contribution to the

development of the steam locomotive, his suggestion that heat loss

would be reduced by placing the

cylinders within the smokebox:

“The first eight engines made by Mr.

[Robert] Stephenson on the Liverpool and Manchester railway, viz.

the ‘Rocket’, ‘Meteor’, ‘Comet’, ‘Arrow’, ‘Dart’, ‘Phoenix’, ‘North

Star’, and ‘Northumbrian’, had the cylinders outside the boiler, and

worked by a crank pin on the wheel. Mr. Bury’s engine the

‘Liverpool’, was then constructed for that railway, and about four

months after it had been placed upon the line, Mr. Stephenson

adopted the crank axle, [9] and

placed the cylinders horizontally, with the improvement of putting

them inside the smoke-box. This was done first to his engine, the

‘Planet’, and it was suggested by a conversation which Mr.

Stephenson had with Trevithick, when they were on their passage from

South America. Trevithick stated there was 40 per cent increase in

the duty of Watt’s engines (worked expansively) in Cornwall from

putting a jacket on the cylinders.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Peter Lecount (1839).

Finally, the Planets acquired a feature that was to become

standard practice in locomotive boiler design, the ‘steam dome’. Its purpose was to provide sufficient space to keep

the opening of the main steam pipe well above the water level in the boiler,

thereby preventing

water from being carried over into the cylinders and cause a condition known

as ‘priming’. Were this occurs, priming can damage cylinder lubrication

and (because water does not compress) result in split cylinders.

“The ‘Planet’, by Messrs. Stephenson,

undoubtedly presented the first combination of the horizontal

cylinders and cranked axle with the multitubular boiler; and the

cylinders were furthermore encased in the smoke box, and thus warmed

by the waste heat escaping from the tubes ― an arrangement suggested

to the late Mr. Robert Stephenson by Richard Trevithick. The

constructors of the ‘Planet’, from their established position and

long practice in engine making, were enabled to turn to good account

the plans and suggestions of Messrs. Hackworth and Kennedy, who had

formerly occupied responsible positions in the Newcastle factory,

and who still maintained a friendly if not intimate intercourse with

their old employers. It must be admitted, to the credit of both the

gentlemen just named, as well as to Messrs. Stephenson, that the

‘Planet’ was the prototype of the modern English locomotive and that

for many years it was the model from which both British and American

locomotive engineers copied, not only freely, but minutely. The

‘Planet’ was tried for the first time on December 4, 1830, and drew

a train of goods and passengers, weighing 76 tons, exclusive of

carriages and wagons, from Liverpool to Manchester in 2 hours 39

minutes, the highest speed on a level being 15½ miles an hour. The

engine, with coke and water, weighed 9 tons, the tender weighing 4

tons. The cylinders were 11 inches in diameter; the stroke of

pistons was 16 inches; the driving wheels were 5 feet in diameter,

and the leading wheels 3 feet. The boiler was 3 feet in diameter,

and 6½ feet long, the fire box presenting 37¼ square feet, and the

tubes 370 square feet of heating surface. The tubes were 129 in

number, and 1⅝ inches in diameter.

In the ‘Planet,’ then, the Locomotive Engine had assumed a definite

and permanent form compatible with a fair degree of speed and

tolerable economy in working. This single engine embodied the

results of numberless efforts at locomotive improvement, ― for

Trevithick’s machine of 1804, crude as it was, was nevertheless a

locomotive engine, needing only improvement, and in the direction

indicated with tolerable distinctness by the inventor himself.”

Locomotive Engineering, and the

Mechanism of Railways: Vol. 1, Colburn and Clark (1871).

Although a fine design, the Planet type was soon to be

superseded by the Patentee, the first ever 2-2-2 locomotive

design [10] that in its essentials became the epitome of

the express passenger locomotive for many years.

The Planets suffered three particular problems that

the Patentee was designed to solve. At speed, the Planet’s short wheelbase gave a

very uneven ride added to which the greater weight placed over the

driving wheels, while providing better adhesion, resulted in a axle

load [11] that was as much as the lightly built permanent way of the

age could withstand. But increasingly heavy trains required greater motive

power; thus, the choice was to continue

building small 4-wheel engines and double (or triple) heading heavy trains

― a practice later followed on the London and Birmingham Railway ― or build more powerful locomotives

and spread the

increased weight over a third axle. [12]

Adding a third axle to the Planet type not only solved the

problems of stability and axle weight, but provided space for a larger boiler

and more power.

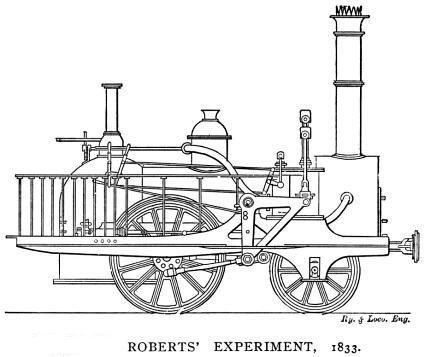

Robert Stephenson’s patent 2-2-2

locomotive.

“Locomotive engines, constructed according

to the description of the foregoing, Mr. Stephenson says, have the

effect of preventing the boilers being burnt out so soon as usual,

by allowing them to be made of greater magnitude and strength; the

additional wheels supporting the extra weight. The bearing springs

are used for the extra small wheels, the same as is now done for

other wheels in ordinary engines; the six springs used causing all

the six wheels to apply and bear fairly on the rails, and ease all

jolts and concussions; the relative weights, or portions of the

whole weight of the engine, which is to be borne by each of the six

wheels, being regulated by the strength and setting of their

respective bearing springs. The main wheels, which are impelled by

the power of the engine, are in all cases, left loaded with as much

of the weight of the engine as will cause sufficient adhesion of

those wheels to the rails, to avoid slipping thereon. The larger the

entire capacity of a boiler is, the more metallic heating surface it

will contain; and consequently, render unnecessary that extreme heat

which is so prejudicial to the metal. And that diminution of the

intensity of the combustion the patentee considers to be

advantageous in another point of view; because the jet of waste

steam (which is thrown into the chimney to produce a rapid draught

therein for exciting the combustion of the fuel) may be greatly

diminished in its velocity, which will permit the waste steam to

escape from the working cylinders with greater freedom than could be

permitted with smaller boilers, wherein a greater heat and a more

rapid generation of steam are indispensable to furnish the requisite

power.”

A Practical Treatise on Rail-roads

and Locomotive Engines, Luke Hebert (1837).

However, the addition of a third axle inevitably lengthened the locomotive’s rigid wheelbase,

which in turn increased

the stress on its (central) cranked axle when negotiating tight curves,

such as in sidings; and as

mentioned earlier, the cranked axles of the age had at any rate a tendency to facture.

Stephenson’s solution was to remove the flanges from the driving wheels. This gave them the ability to move laterally on sharp curves, thereby

relieving the stress on the cranked axle, while the flanged wheels on

the front and rear axles kept the locomotive on the track: [13]

“So considerable is the movement of the

driving wheels in such cases towards the inside of the curve, that

the flange of the inner wheel is often forced violently against the

rail. To this strain the frequent breaking of crank axles was

formerly attributed; and the late Mr. Robert Stephenson, in his six

wheel engine patent, based his claim upon the making of the driving

wheels with plain tyres, or tyres without flanges.”

Locomotive Engineering, and the

Mechanism of Railways: Colburn and Clark (1871).

A further innovation that Stephenson introduced was the

steam-powered brake. This was not a train braking system, but

applied only to the locomotive’s driving and trailing wheels (see

side elevation above ― the steam brake cylinder is at letter ‘a’). But the steam brake did not catch on and it was to be

some decades before steam braking was adopted.

The flangeless wheel and steam brake, together with other

improvements, became the subjects of a patent granted to Stephenson

in October 1833 ― hence the name given to the class locomotive,

Patentee:

A.D. 1833, October 7. ― No. 6484.

STEPHENSON, ROBERT. ―

Improvement, applying to that kind of locomotive carriage used on

the Manchester and Liverpool Railway (the first of which was called

the Planet), having the two main wheels fixed on a double-cranked

axle turned by the engine, to advance the carriage along the edge

rail. Makes the tyres of these main wheels without any projecting

flanges, and runs them plain upon the edge rails, and places beneath

the hinder end of the engine two small wheels with flanges on their

tires, to keep them straight on the rails.

2. A “brake or clog,” which is caused to press on the tires, by

means of a piston working in a small cylinder, supplied with steam

from the boiler.

3. Describes a locomotive engine carriage in present use (1833),

with the improvements added.

Patents for inventions.

Abridgments of specifications: Patent Office (1871).

The Patentee was completed at the workshops of Robert

Stephenson & Co. on 25th September 1833 and then delivered to the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway. [14] Other

locomotives of the Patentee type were constructed with 0-6-0

and 0-4-2 wheel arrangements:

“The following cut exhibits another form of

Mr. Stephenson’s locomotive engine, such as is now in use, but with

the foregoing improvement added thereto. The foremost wheels, at the

chimney end of the boiler, are, in this, however, impelled by means

of outside cranks and connecting rods, as well as the two middle

wheels K, [above] which are on the cranked axle; in other respects, the

improvement is the same as in the other engine. The brakes, or

clogs, are, of course, applicable to this or any other engine, but

they are left out in this instance as being unnecessary to our

illustration.”

Locomotive Engineering, and the

Mechanism of Railways: Colburn and Clark (1871).

A Patentee in 0-4-2 form.

――――♦――――

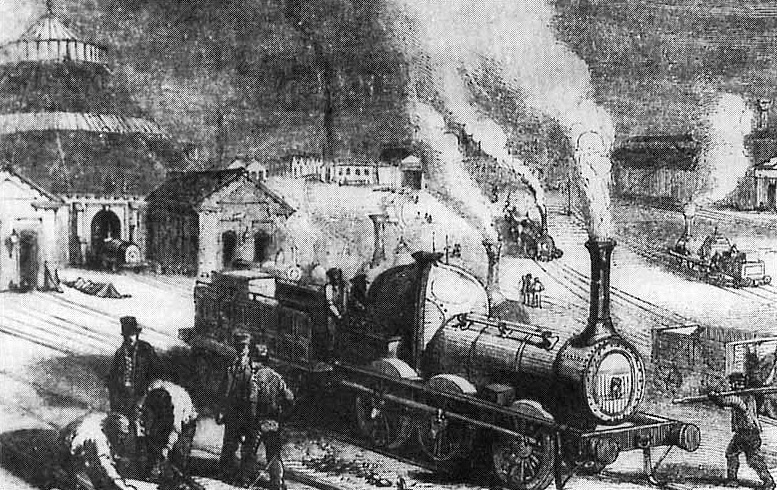

EDWARD BURY

The Harvey Combe on

construction work near Berkhamsted, June 1837, by John Cooke Bourne.

The diminutive locomotive pictured above is a Stephenson Patentee,

the Harvey Combe. One might wonder why an express passenger

locomotive ― “the best of its day”,

to use one commentator’s description [15]

― was relegated to the task of hauling a train of earth

wagons on a construction site. However, before looking into the background of the Harvey Combe,

it is first next necessary to turn to Edward Bury, whose star shone brightly in the

railway firmament for some twenty years and who, together with his

works foreman, James Kennedy, had an important influence on

locomotive development.

|

|

|

Edward Bury F.R.S.,

M.I.C.E. (1794-1858) |

Bury was a talented man with a mechanical

aptitude. [16] In 1826 he set up the Clarence Foundry, an engineering and iron foundry

business in Liverpool, where for a number of years

railway locomotives were manufactured successfully for both

domestic and overseas markets:

|

“The first locomotive ever used in the

United Stales is still in good running order on the Little Schuykill

railroad. It was built in Liverpool, England, by Edward Bury. At

that time it was necessary to send a man from England to put the

engine in running order on the road. It was but twenty years ago

that Edward Bury’s engine was placed upon this road. Since then, the

iron track has extended throughout our land; the fierce breathing of

the iron horse is heard in almost every valley; the ingenuity of our

own Mechanics enables them to supply our own engines; and even

furnish them to nations across the ocean.”

Railway Locomotives and Cars,

Volume 24 (1851). |

Bury’s foreman, James Kennedy, [17] had

previously held the position of Manager at the Newcastle factory of

Robert Stephenson & Co. The extent to which Bury and Kennedy

collaborated on their locomotive designs remains a matter of

conjecture, but the prevailing view is that Kennedy was the

principal designer:

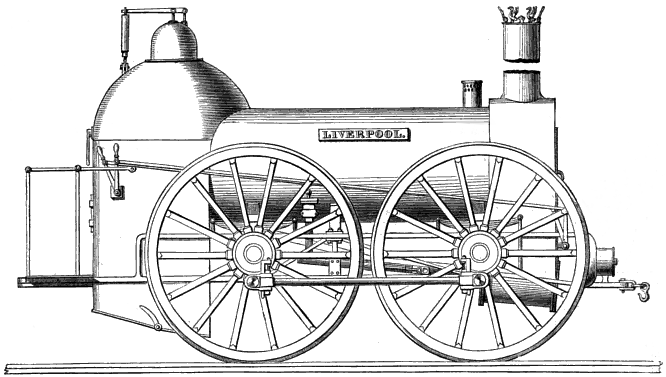

“The first engine made by Mr. Bury was the

‘Dreadnought,’ which was started on the Liverpool and

Manchester railway March 12, 1830. She had six wheels and was much

objected to on that account. The next was the ‘Liverpool’;

this was the original engine made by him with horizontal cylinders

and cranked axles. She was placed on the Liverpool and Manchester

Railway on July 22, 1830, and had an 18 inch stroke, two pair of

six-feet coupled wheels, and 12inch cylinders.”

A Practical Treatise on

Railways, Peter Lecount (1839).

The history of Bury’s first two locomotives, the

Dreadnought and the

Liverpool, is confused, both with regard to their construction

and later life. The Dreadnought was intended to compete in the Rainhill

Trials but was not ready in time. No image of the locomotive is

known to exist, but in the biographic sketch she wrote of her husband,

Priscilla Bury describes it thus:

“Mr. Bury’s first locomotive was the

‘Dreadnought’, commenced in 1828. She had the old type of boiler

[return flue?] and six wheels, with

cylinders ten inches diameter, two feet stroke, and two valves ―

one the ordinary, the other the expansion valve ― to allow the

steam to be worked expansively.”

Recollection of Edward Bury, by

his Widow (published privately, Windermere, 1860).

The expansion valve that Priscilla refers to must have made the

Dreadnought one of the earliest ― if not the earliest ―

locomotive to have an adjustable cut-off. Subsequently, the Dreadnought

worked as a ballast engine on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway,

which was then under construction, but it was not retained by the

Company on account of its excessive weight and, some authors

suggest, its rolling motion. The engine was then sold to the Bolton and Leigh

Railway. That is one account of the Dreadnought’s

later life, but there is another ― see fn 18.

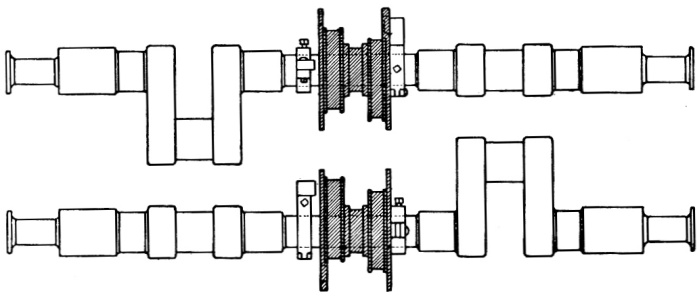

A cranked axle.

According to Edward Woods, [19] onetime Locomotive Superintendent of the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway, Bury’s second engine, the

Liverpool, was equipped with a modified form of return-flue

boiler (which accords with Priscilla’s

description of it) that would have left the fireman and driver

facing each other from opposite

ends of the boiler.

Following a serious derailment while at work on the Bolton and Leigh

Railway, the locomotive was rebuilt by Bury with a new

multi-tube boiler, and presumably then appeared as shown below. In this

form it had several similarities to Stephenson’s

Planet. Both locomotives had multi-tube boilers and (nearly)

horizontal cylinders placed between the frames driving a cranked

rear axle. Stephenson was adamant in later years that in arriving at

this arrangement in the Planet he was not influenced by the

Liverpool’s design; [20] the

appearance of these significant design changes in both locomotives contemporaneously must

therefore have been coincidence.

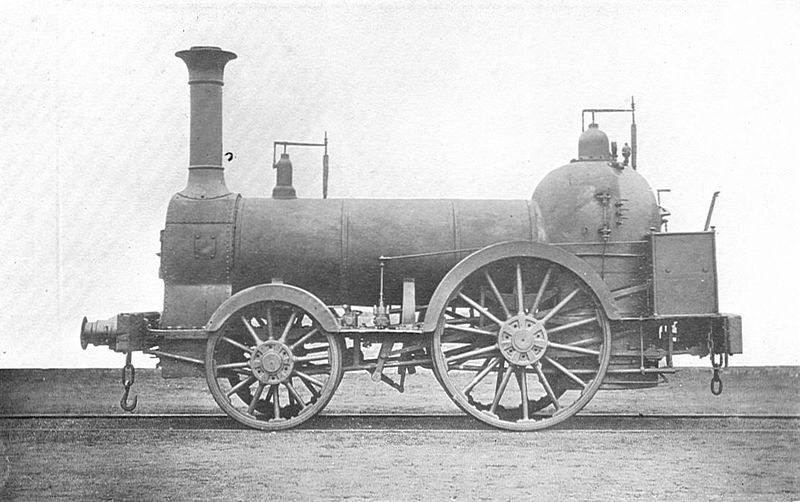

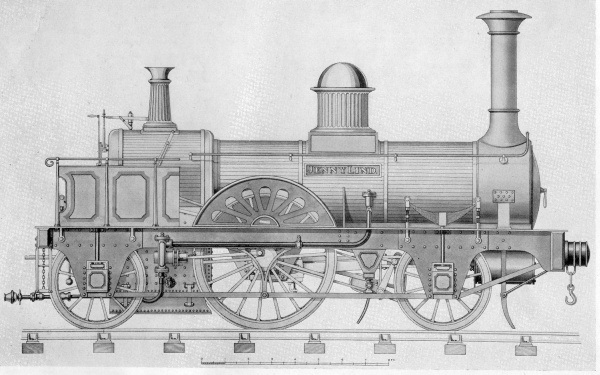

The Liverpool, by Edward

Bury & Co., 1830.

“The first permanent type of modern

locomotive was that of Mr. Edward Bury of Liverpool. Mr. Kennedy, by

whom this locomotive was designed and constructed, had several years

before been the manager of Mr. Stephenson’s works at Newcastle, and

had subsequently joined Mr. Bury, by whom the manufacture of

locomotives was then begun. The locomotive ‘Liverpool’

embodying his improvements, was put to work on the Liverpool and

Manchester Railway on the 22nd of July 1830 . . . . The cylinders are placed in a horizontal position, and the

connecting rods operate upon cranked axles. The framing is that

known as inside framing, and the general arrangements are such as

Messrs. Bury, Curtis, and Kennedy subsequently persisted in with so

much success.”

A treatise on the steam-engine in

its various applications; Artizan Club (1868).

Other than their similarities, there were some significant

difference between the Liverpool and the

Planet.

The Liverpool’s 0-4-0 wheel arrangement

(compared to the Planet’s 2-2-0) was a superficial difference,

but its 6 feet diameter wheels (compared

to the Planet’s 5 feet) were not; this caused George

Stephenson, for no clear reason, to advise the Company not to buy

the locomotive. It is possible that he believed that on the poor

quality track of the time, derailment was more likely with large

diameter wheels, but he might equally have wished to steal a lead

over a competitor.

Bury’s locomotive was equipped with what became known

as a Haycock or Gothic Arch boiler of his

devising. It had a prominent upright firebox, the outer

shell

of which comprised a vertical cylinder capped with a dome, which dispensed with the need for a separate steam dome.

Seen in plan, the inner firebox was D-shaped; although short, it

was deep, giving plenty of space for the fuel to burn through

before the hot combustion gases entered the firetubes.

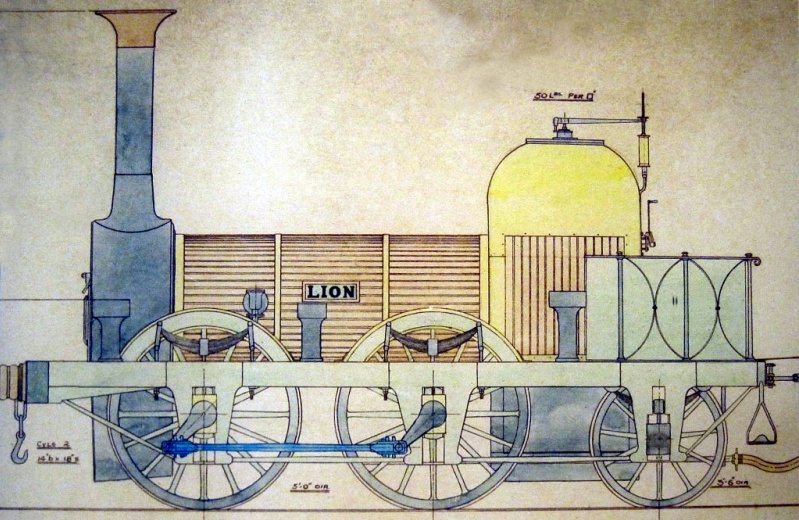

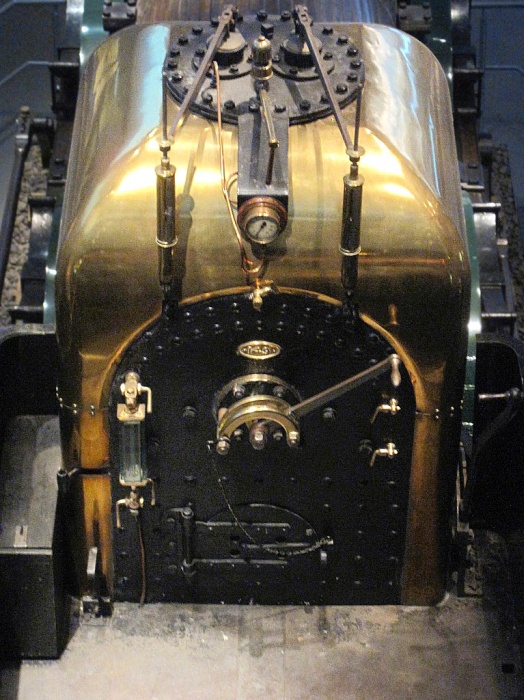

Above and below: a locomotive fitted with a Haycock or

Gothic Arch boiler.

Lion was built in 1838 by

Todd, Kitson and Laird of Leeds for the Liverpool & Manchester

Railway.

But the most notable difference between the two types of locomotive

lay in their frames (comparable in function to a road vehicle’s

chassis). The Planet was built on an outside ‘plate

frame’; in essence, this was a box structure built out of

vertical planks and/or metal plates (see photograph),

and frames of this type

later became common in locomotives of European manufacture. By

comparison, the Liverpool was built on a frame comprising

iron bars. Perhaps as a result of the popularity of the locomotives

that Bury exported

to North America, the ‘bar frame’ later became standard for locomotives

manufactured there.

4-wheeled locomotives that had twin inside cylinders, a haycock

boiler and bar frames became known as ‘Bury types’.

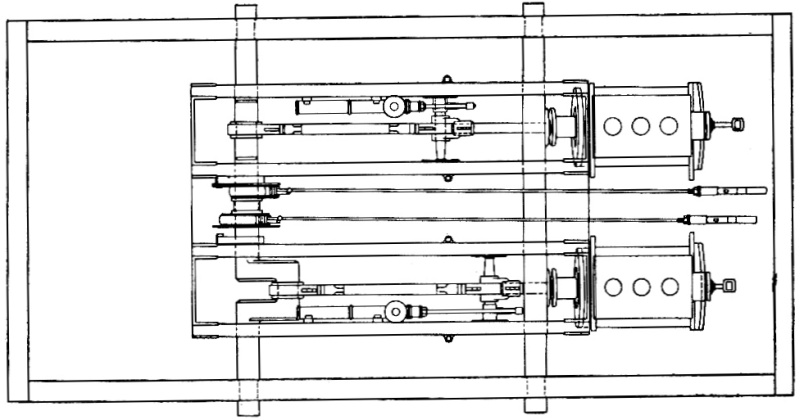

Plan of the Planet’s frame

― cranked rear axle on the left, inside (horizontal) cylinders on

the right.

The cranked axle is supported by 6

bearings, 2 on the main frame and 4 on the sub-frames.

|

|

|

Top, plate frame for a

4-2-6 locomotive; bottom, bar frame for a 2-6-0. |

|

|

The Rainhill Trials having demonstrated the feasibility of working

the line with locomotives, the Company bought a number of the Rocket and

(later) Planet types from Robert Stephenson and

Co.; indeed, during the first three years of the Railway’s operation

the firm supplied almost all its locomotive stock. [21] George Stephenson, who by then was generally regarded as a guru on

railway matters,

considered it his prerogative as Chief Engineer to

specify the line’s motive power requirement. Thus, it is hardly

surprising that manufacturers competing with the

family firm would find difficulty

meeting the Railway’s requirement in

circumstances where their product differed substantially ― as, for

instance, did Edward Bury’s bar frame and haycock boiler

construction ― from that

specified by Stephenson, which could, of course, be met easily by Robert Stephenson and Co. And although

Stephenson’s specification might be

met by other manufacturers, royalty payments would become due on

aspects of the design for which Robert Stephenson & Co. held the

patent. It is therefore unsurprising that some board members

came to believe that having their Chief Engineer specify how the

Railway’s motive

power requirement was to be met smacked of nepotism, if not

monopoly.

A entirely new development then arose of a type that has resounding echoes

in our own age. Charles Tayleur &

Co., an engineering firm [22] based near the Railway at Newton-le-Willows

and in which the Stephensons

had a financial interest, proposed what today would be described as

a service management contract. Under its terms, Tayleur & Co. offered to supply, operate

and maintain the Railway’s motive power needs for an agreed sum. Although

the proposal was declined, this type of contract was to appear on the London and Birmingham Railway,

and with interesting consequences.

After much debate [23] and wavering strategy, the

Liverpool and Manchester directors decided that their motive power requirements would

best be met

by open tender. In 1834, Robert Stephenson & Co. delivered the Patentee, the first

ever 2-2-2, which turned out to be the last order that the Liverpool

and Manchester Railway

placed with the firm. Charles Tayleur &

Co. continued to supply the Railway with locomotives until 1837, but

by then the Stephensons had been obliged to severe their connections

with Tayleur due to a conflict of interest issues arising with other

projects in which they were involved, one such being the London and

Birmingham Railway.

While the motive power debate progressed at Liverpool, similar

concerns were fermenting in the boardrooms of the London and

Birmingham Railway, some of whose directors had interests

in both companies. By now construction of the London and

Birmingham line had begun, and the Board’s thoughts were turning to the question

of how motive power was to be sourced. Robert Stephenson drew

up a specification for its locomotives that

conformed with his 2-2-2 Patentee design, which meant either

the Stephensons benefitting directly if they built the engines, or

indirectly (through royalties on the patents)

if they were sourced elsewhere.

|

|

|

Birmingham

Gazette, 9th November 1835. |

Towards the end of 1835, the London and Birmingham Railway advertised

for tenders to provide motive power, either by selling the Company

the locomotives or by providing the motive power on a service

management basis. Charles Tayleur & Co. submitted a service

management proposal from which, had it been accepted, the

Company’s Chief Engineer (Robert Stephenson) would have benefitted one way or the other.

However, Tayleur’s

proposal was rejected, possibly for that reason. Edward Bury

also submitted a tender by which the Company would buy locomotives

built to his specification, which he would then operate and maintain

for an agreed rate.

While Bury’s proposal was being considered, Robert Stephenson

attempted to influence the Company’s locomotive policy by having W.

& L. Cubitt, the building contractor for the Berkhamsted section of

the line,

accept a Patentee as a works engine. The locomotive,

originally destined for Belgium, was shipped to London, then up the Grand

Junction Canal to Bourne End where it was assembled and later

depicted at work in Cooke Bourne’s famous drawing.

But Stephenson’s tactic was to no avail and Bury’s tender was

duly accepted:

“The Directors have entered into a

contract, under the guarantee of two responsible sureties, with Mr.

Edward Bury, of Liverpool, an able and experienced builder of

locomotive engines, for the conveyance of passengers and goods, on

the railway, by locomotive power, to whatever extent may be

required, at a fixed rate of remuneration; the Company providing

engines of Mr. Bury’s specification, and Mr. Bury on his part

maintaining and keeping them in repair; the contract to be in force

for three years from the opening of the railway. The Directors have

also contracted for such locomotive engines as will be first wanted,

and for a portion of the carriages.”

The Railway Magazine,

Vol. 1 (1836).

The contract terms were ¼d per mile per passenger,

at a speed not to exceed 22½ mph, and ½d per ton per mile for the

conveyance of goods. [24] The contract was to

remain in force for three years following the opening of the

Railway, but an interim arrangement must have been agreed to cover

the period during which the line was being opened in stages. However, the arrangement proved unworkable.

In July 1839, the contract was annulled and Bury

was appointed Superintendant of the Locomotive Department, for which

he received a

salary. He chose Wolverton in Buckinghamshire, midpoint

on the 112½ mile-long line, as the

location of his headquarters and locomotive workshops, which opened in 1838 and eventually grew into Wolverton Works.

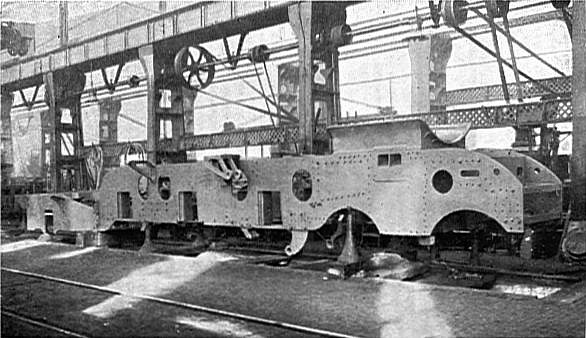

Because Bury was unable to meet the Company’s delivery deadline, the first tranche of locomotives

were built

by a consortium of suppliers working to a common specification (Appendix

III.): indeed, Bury can be said to have been the first

“Chief Mechanical Engineer”

― a later designation, but one applicable nevertheless ― to insist

on standardization:

“It is to be noted, that although the

London and Birmingham engines are made by different persons, they

are constructed exactly alike, in all their parts, and to an exact

size every where, being entirely made from working drawings given

out by Mr. Bury of Liverpool, who contracts to work the line. This

will, eventually, conduce to great economy, as every individual part

of an old and disabled engine, which is worth preserving, can be

used in the formation of a new one.”

The History of the Railway

Connecting London and Birmingham, Lieut.

Peter Lecount R.N. (1839).

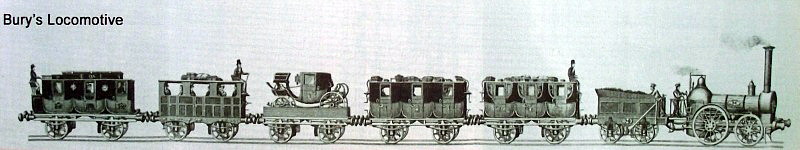

Above, a Bury 2-2-0 passenger locomotive of the London &

Birmingham Railway.

Note the upright cylindrical domed firebox.

Below, a Bury 0-4-0 freight locomotive, built in 1846 by Bury,

Curtis & Kennedy of Liverpool

for the Furness Railway.

All Bury’s locomotives for the London and Birmingham Railway (both passenger and goods) were 4-wheeled (see also

Appendix IV.), the advantages of which Bury set out thus:

“The four-wheeled engine is less costly

than that on six wheels; it can be got into less space; is much

lighter, and therefore, requires less power to take it up the

inclines, and consequently leaves more available power to take up

the train; is safer, as it adapts itself better to the rails, not

being so likely to run off the lines at curves or crossings; is more

economical in the working, there being fewer parts in motion, and

less friction; those parts of the machinery which are common to both

plans are more easily got at in the four wheeled engine the

buildings and turntables are not required to be on so large a scale

as there are fewer parts in the four-wheeled engine; fewer tools, as

lathes, drills, &c., are required; having fewer parts to be

deranged, stoppages are not so likely to take place on the journey.”

A Rudimentary Treatise on the

Locomotive Engine in all its Phases:

George Drysdale Dempsey

(1856).

While Bury might, at first, have had a point on safety ― for he

mentions derailments on curves and crossings ― as the standard of

track improved, so those particular risks diminished. In other

respects his belief that locomotive size had reached the point at

which the law of diminishing returns set in ― that larger engines

delivered less value in relation to their overall cost ― was flawed:

“The locomotives on the London and

Birmingham were small and light compared with those now in use. A

few used in the goods department were coupled. The passenger-trains

were run by an engine on four wheels, the driving-wheel being about

five feet six in diameter. They were swift, but hardly strong enough

for the work, and many of the trains required two engines to draw

them, and a pilot engine was always on the station at Wolverton

ready to go in search of belated trains, and assist them.”

Railways in 1840 . . . . from

Notes of my Life, H. Stowell Brown (1888).

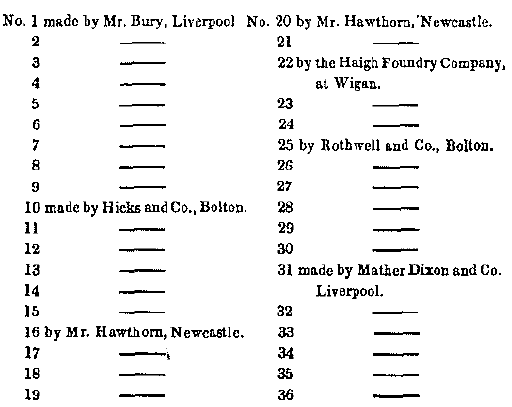

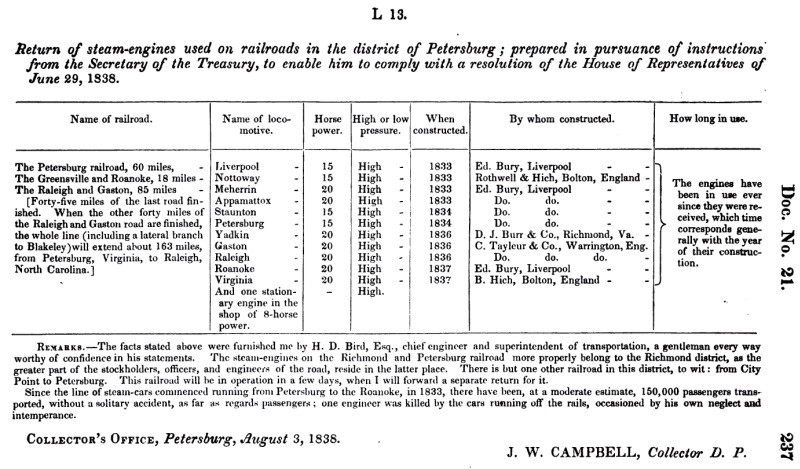

In his History of the Railway connecting London with Birmingham

(1839), Peter Lecount lists the following locomotives as being

active on the line in August 1838:

Lecount also refers to a Stephenson locomotive, but without

identifying it ― if not the Harvey Combe it was probably of

that type, and if so, the data that he provides gives some clue as

to its tractive power:

“A very superior engine was also made by

Robert Stephenson, for carrying the trains up the inclined plane

from the Euston Square station to Camden Town, till the fixed

engines were completed; and the performance of the whole has been

most satisfactory, as may be judged from the following instances.

The average of fourteen trips, of twenty-three miles, up 1 in 440,

with the engine No. 16, was twenty-two miles an hour, with a gross

weight, including the tender, of seventy-five tons, ― viz., fourteen

carriages and one hundred and forty-eight passengers: the

consumption of coke was 148 lbs.

The average of fourteen trips, of three-quarters of a mile, up 1 in

90, from Euston Square to Camden Town, with the large engine built

by Robert Stephenson and Co., was fifteen miles and hour, with

seventy tons, ― viz., fourteen carriages and one hundred and

forty-eight passengers.”

The History of the Railway

Connecting London and Birmingham, Lieut.

Peter Lecount R.N. (1839).

By 1845, the Railway’s locomotive stock consisted of one six-wheeled

(the Harvey Combe?) and 89 four-wheeled locomotives, but by then experience had demonstrated that for high speeds,

heavy loads and severe gradients, larger engines were necessary to

handle the traffic effectively. By the time Bury’s superintendence

of the motive power department ended, the six-wheeled locomotive

had been adopted on the London and

Birmingham Railway, as it had long been on most others;

“ACCELERATION

OF THE MAIL TO LIVERPOOL:

We learn that a desire has been expressed by the Post Office

authorities that the London and North-Western Company should run a

mail train between London and Liverpool (210 miles) in five hours,

and we believe there is little doubt that such an acceleration of

the mail will soon take place. On Friday afternoon the London and

Birmingham directors, who, we believe, had to attend, at Manchester,

a board meeting of the London and North-Western Company ― of which

it will be recollected, the London and Birmingham is now a component

portion ― tested the capacity of the ordinary passenger engines for

such a rapid journey north. The train (a special one) consisting of

six first class carriages left Euston-square at five minutes before

five o’clock in the afternoon, and reached Birmingham at 33 minutes

past seven o’clock, having been detained at Wolverton 14 minutes

beyond the time necessary for the change of engine . . . . It is

necessary to state that the journey over the London and Birmingham

line was made with the ordinary four-wheel passenger engines, with

five feet nine driving wheels. They are Mr. Bury’s make, and weigh,

we believe, between 10 and 11 tons only. Within the last fortnight

two very powerful six-wheel engines, with six feet driving wheels,

and made by the same manufacturer, have been put on the London and

Birmingham line. They are stated to be equal to twelve carriages, at

an average speed of 50 miles an hour over the unfavourable

gradients from Euston to Tring.”

The Standard, 15th September

1846.

In the design of his 4-wheeld locomotives

Edward Bury erred on the side of caution and reliability. But with that caveat, during his time in office

he delivered what was expected of him (see also

Appendix V.):

|

“The Directors considering it of more

importance that passengers should be able to rely on a certain and

safe conveyance to and from the stations where the trains stop, than

that they should in the first instance travel at the highest

attainable speed, have made it their chief aim in the regulation of

the trains to ensure a uniform precision of movement on the railway. In this endeavour they have been ably seconded by their contractor

for locomotive power, Mr. Bury, and a degree of punctuality in the

arrivals and departures has for some time past been attained at all

the stations, which, considering the unavoidable imperfections of a

road so recently formed, and the many difficulties to be surmounted

in every new undertaking, the Directors could scarcely have

anticipated, and which they may add has not been accomplished upon

any other railway.”

Herapath's Railway Journal,

Vol. 4 (1838). |

From 1845 Bury began to build larger six-wheeled locomotives with

his usual bar frames; one of these, a 2-2-2 passenger locomotive of

1847 was preserved and is on display at Cork railway station.

This sketch is of a scene outside

the Luggage Engine House at Camden (‘The Roundhouse’).

The unidentified 6-wheeled

freight locomotive in the foreground appears to be a Bury design.

In March, 1847, Bury resigned his post from what by then had become

the London and North Western Railway Company; he later became, for a

short time, General

Manager of the Great Northern Railway after which he retired from

railway business. His entry in the Oxford Dictionary of

National Biography concludes thus:

“By his