|

NOTES AND EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON

& BIRMINGHAM

RAILWAY

CHAPTER 13

THE RAILWAY IN OPERATION

THE EARLY DAYS

|

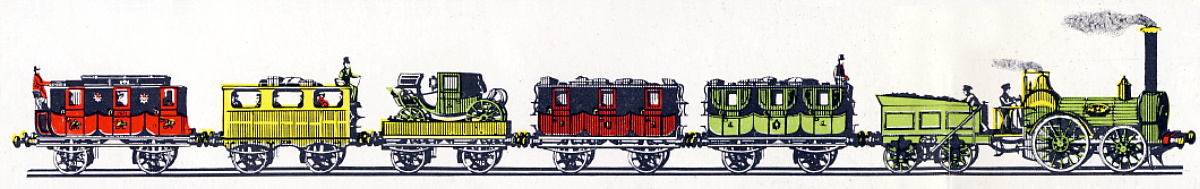

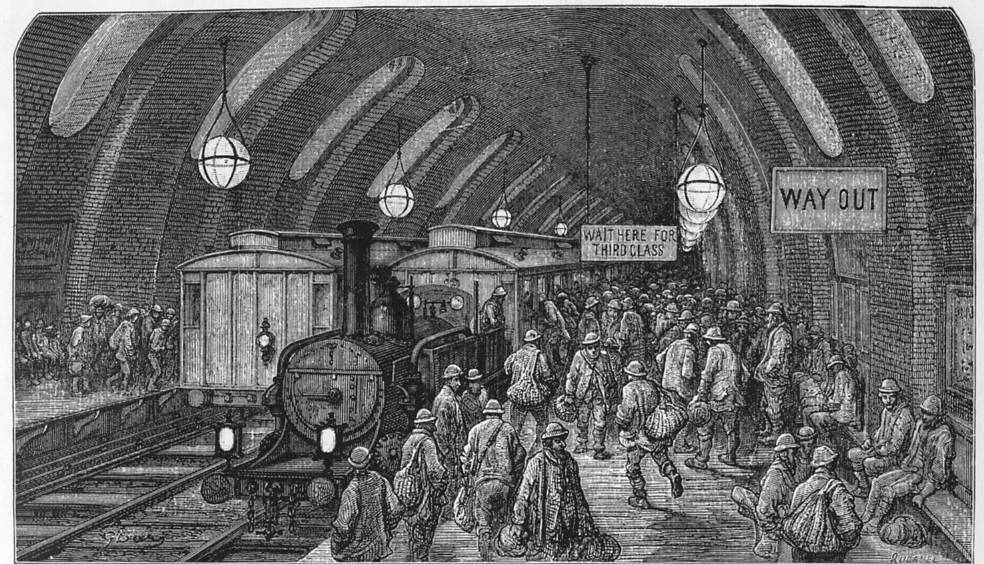

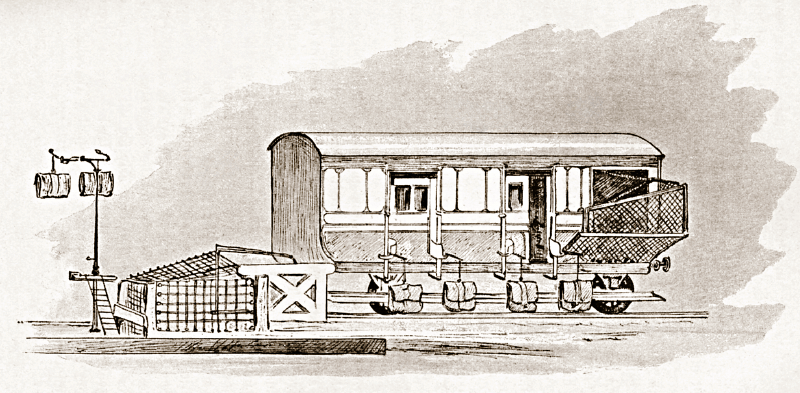

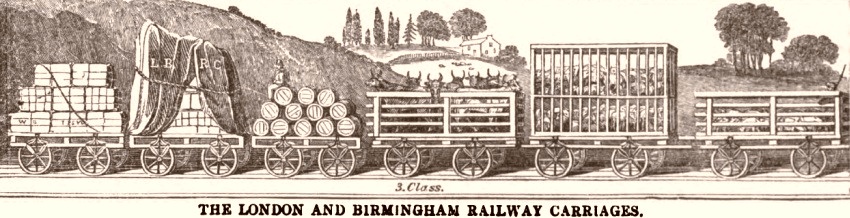

A Bury engine heads up a mixed

train. The carriage second from the end is a 2nd-class day coach.

Note the guards seated

outside, a leftover from stage coaching days. Among other duties

they operated the carriage brakes.

“When railways were first established,

every living being gazed at a passing train with astonishment and

fear; ploughmen held their breath; the loose horse galloped from it,

and then, suddenly stopping, turned round, stared at it, and at last

snorted aloud. But the ‘nine days’ wonder’ soon came to an

end. As the train now flies through our verdant fields, the cattle

grazing on each side do not even raise their heads to look at it;

the timid sheep fears it no more than the wind; indeed, the

hen-partridge, running with her brood along the embankment of a deep

cutting, does not now even crouch as it passes close by her. It is

the same with mankind. On entering a railway station we merely

mutter to a clerk in a box where we want to go ― say ‘How much?’ ―

see him horizontally poke a card [an Edmondson

ticket] into a

little machine that pinches it ― receive our ticket ― take our place

― read our newspaper ― on reaching our terminus, drive away

perfectly careless of all or of any one of the innumerable

arrangements necessary for the astonishing luxury we have enjoyed.”

The London Quarterly Review,

No. CLXVII. (1848).

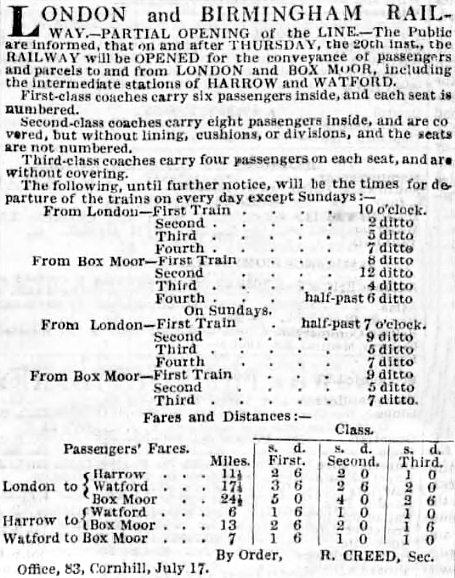

The London and Birmingham Railway was opened in stages as

construction progressed. A service between Euston and Boxmoor (now

Hemel Hempstead station), calling at the

intermediate stations of Harrow and Watford, commenced on 20th July 1837:

LONDON AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY.

PARTIAL OPENING OF THE LINE, 1837.

The public are informed that on and after Thursday, the 20th inst.,

the Railway will be opened for the conveyance of Passengers and

Parcels to and from London and Boxmoor, including the intermediate

stations of Harrow and Watford.

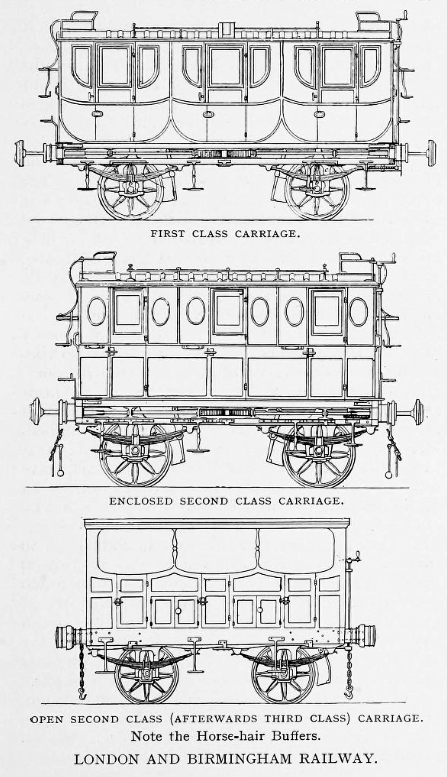

First class coaches carry six passengers inside, and each seat is

numbered.

Second class coaches carry eight passengers inside, and are covered,

but

without lining, cushions or divisions, and the seats are not

numbered.

Third class coaches carry four passengers on each seat, and are

without

covering.

The following, until further notice, will be the times for departure

of the

Trains on every day except Sundays. |

|

|

|

|

The London

Standard, 19th July 1837. |

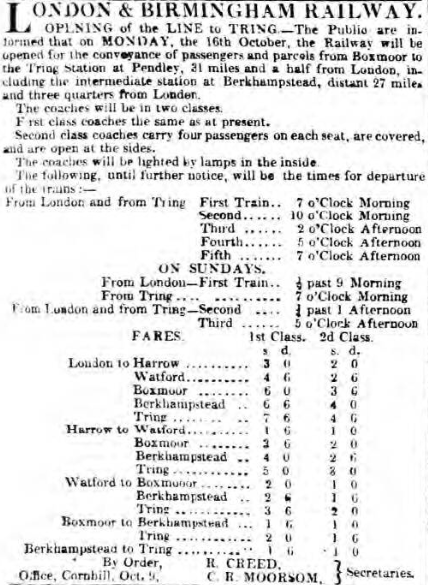

The Morning Post,

16th October 1837 |

|

On the 16th

October the service was extended to Tring; then, on the 9th April, to a temporary station at Denbigh Hall (Wolverton), a road coach shuttle service being used to

bridge the 38-mile gap to Rugby from where, on the same day, a

service to Birmingham had also commenced. On the 17th September

1838, the line was opened throughout, the temporary station at

Denbigh Hall being closed shortly afterwards. |

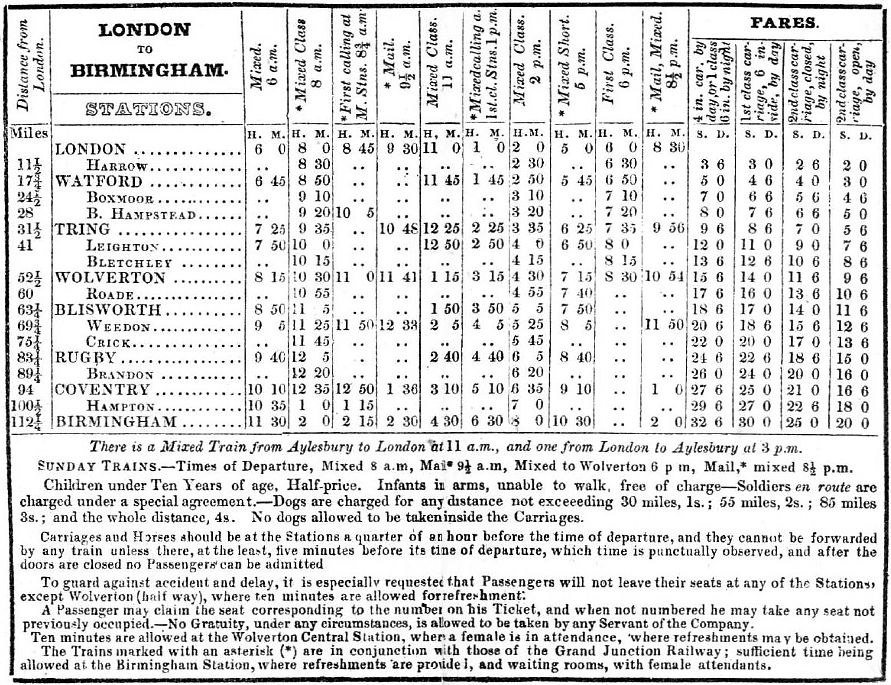

Bradshaw’s London and Birmingham Railway

timetable for 1839.

2nd class passengers did not have a comfortable journey,

especially

during the day when the carriages were open-sided.

|

It is interesting to note that although the Company did

not at first offer a third-class service, third-class tickets

were

offered for the opening of the line to Boxmoor. At a time when

agricultural labourers were supporting their families on

between ten and fifteen shillings a week, at 2s. 6d, even a

third-class ticket into London would have been

prohibitively

expensive. By the time the line was extended to Tring,

Company advertising shows that

third-class fares were no longer available, the cheapest Boxmoor to

Euston (single) fare by then having increased to 3s. 6d. It is plainly

evident that the Company

had no interest in attracting the labouring-classes who had to

await W. E. Gladstone’s ‘Railway Regulation Act’ of 1844 for a

service ― the ‘parliamentary train’ ― that was cheap enough to

enable working men to use the railways to find work:

“At this period third class passengers

fared very badly, in fact, much worse than cattle do nowadays; far

from being encouraged, they were tolerated as a necessary nuisance

and that was all; but the Manchester and Birmingham Railway led the

way to better things, and from the first treated its third-class

patrons in a very generous way. Third class accommodation was

provided on all the twelve trains which performed the journey each

way daily at a rate of some twenty-five miles per hour. This was a

great concession, for third class passengers were at this date

generally restricted to one or two of the slowest trains of the day,

which started at some unearthly hour and performed the journey

between its innumerable halts at a leisurely crawl.”

The History of the London and

North-Western Railway, Wilfred L. Steel (1914).

In January 1842, the railway department of the Board of trade sent

out a circular letter to railway companies asking, among other

questions, “Whether third-class or other passengers-carriages go

with trains partly composed of luggage-waggons.” In most cases

the returns indicated that third-class passengers were conveyed by

the same trains as other passengers, but upon the London and

Birmingham Railway they were conveyed by a special train along with

cattle, horses and empty return-waggons. [1]

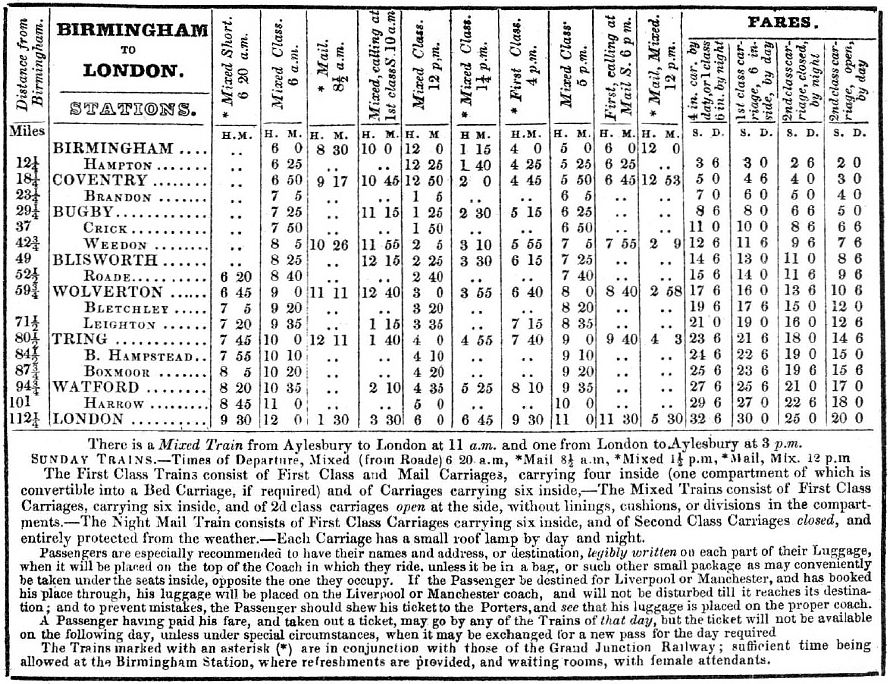

A third-class carriage

from the earliest days of railway travel.

“The

seats are so arranged that the whole space of the

carriage is accessible by a single door. Two doors are,

however, provided, one opposite to the other, and

situated in the middle of the sides of the carriage.

This carriage is adapted to hold about thirty-two

persons. The carriages, which were established on most

of the English railways under an order in Parliament,

and hence called

‘Parliamentary’

or ‘Government’

carriages, closely resemble the one here shown in the

position of the doors and arrangement of the seats, but

differ from it in accordance with the Parliamentary

order in being wholly enclosed, the sides being

continued upwards and roofed over and having two or more

small glazed openings on each side.”

The Practical Railway

Engineer, G. D. Dempsey (1855)

|

THE THIRD-CLASS

TRAVELLER’S

PETITION

From Punch (magazine)

|

Pity the sorrows of a third-class man,

Whose trembling limbs with snow are whitened

o’er,

Who for his fare has paid you all he can:

Cover him in, and let him freeze no more!

This dripping hat my roofless pen bespeaks,

So does the puddle reaching to my knees;

Behold my pinch’d red nose—my shrivell’d

cheeks:

You should not have such carriages as these.

In vain I stamp to warm my aching feet,

I only paddle in a pool of slush;

My stiffen’d hands in vain I blow and beat;

Tears from my eyes congealing as they gush.

Keen blows the wind; the sleet comes pelting

down,

And here I’m standing in the open air!

Long is my dreary journey up to Town,

That is, alive, if ever I get there.

Oh! from the weather, when it snows and

rains,

You might as well, at least, defend the poor;

It would not cost you much, with all your

gains:

Cover us in, and luck attend your store. |

|

Today, the Railway Regulation Act is remembered mainly for its requirement that:

one train ― which became known as the parliamentary or

government train ― with provision for carrying third-class passengers, should

run on every line, every day, in each direction, stopping at every

station;

the fare should be 1d. (½p) per mile;

its average speed should not be less than 12 miles per hour;

third-class passengers should be protected from the weather and be

provided with seats;

third-class passengers should be allowed to take up to 56 lbs of

luggage with them, free of charge.

In his lines in the operetta, The Mikado, the lyricist W. S.

Gilbert satirized this slow and inconvenient form of travel thus:

The idiot who, in railway

carriages,

Scribbles on window panes,

We only suffer,

To ride on a buffer,

In parliamentary trains. |

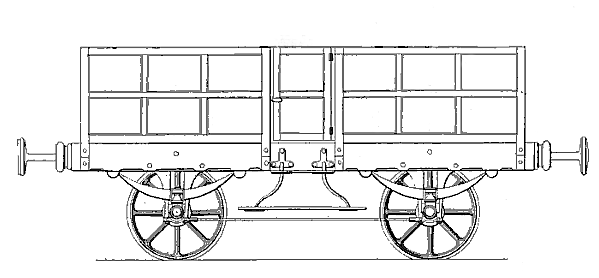

The Workmen’s Train, an

illustration by Gustave Doré

Third-class.

In return for this concession, the railway operator was exempted

from paying duty on third-class passengers.

However, train fares remained high, not only for the working classes,

but for many potential first and second-class travellers. The

Directors eventually realised that the Company would profit by

encouraging more people to travel by train, and that this could best

be achieved by reducing ticket prices across the board:

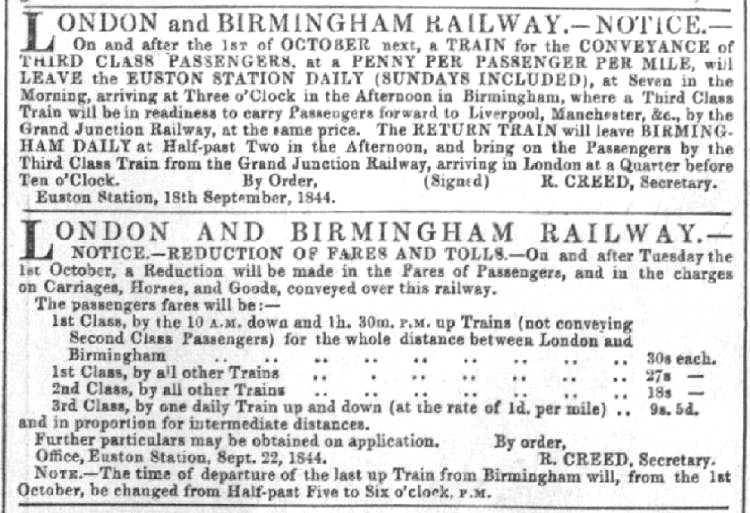

Illustrated London News,

12th October 1844.

Fare reductions were made, and a couple of years later the outcome was reported to Parliament by

Richard Creed, the Company Secretary:

Q ― “The Committee understand that the London

and Birmingham Railway Company have at different times made

reductions in their fares and charges; can you state the particulars

of them? ―

A ―

In September, 1844, the fares through, between London and

Birmingham, were 32s 6d for the mail train; 30s for the ordinary

first class; for the second class 25s and 20s; and for the third

class 14s.

In October, 1844, they were 30s and 27s for the first class; for the

second class 18s; and for the third class 9s 5d.

In April, 1845, they were for the first class 30s, 27s, and 23s; for

the second class 18s and 16s; and for the third class 9s 5d.

In May, 1845, we reduced to 27s for the express; and 23s and 20s for

the first class; the second class to 17s and 14s; and the third

class the same.

In January this year [1846] the

first class were reduced to 25s for the express train; and 20s for

the ordinary first class; 14s the second class; and the third class

a penny a mile, 9s 5d.

In addition to the above reductions, on the 1st of January, 1845,

day tickets were issued at one-third less than the regular fares; so

that, while in 1844 a passenger from London to Birmingham and back

paid 65s or 60s for the first class, and 50s or 40s for the second

class, he now pays only 26s 6d for the first class and 18s 6d for

the second class.

Q ―

“What is the extent of the difference between the prices charged

originally and the present prices? A ― It is exactly one third

reduction.

Q ―

“Have those reductions been attended in any instance with a loss of

revenue? A ― The reductions on the first class in the half year ending

30th of June, 1844, were 17¼ per cent, and it caused an increase in

the number of passengers of 19½

per cent. In the second class it was 26 3/5 per cent reduction in

the fares, and there was an increase in the number of passengers of

61 1/5 per cent. In the third class the reduction in the fares

was 33⅓ per cent, and the

increase in the number of passengers 259 per cent. That is the

effect of the reductions in the half years ending the 30th June,

1844, and the 30th June, 1845.”

Evidence given by Richard Creed to

The Committee on Railway Acts Enactments (26th June 1846).

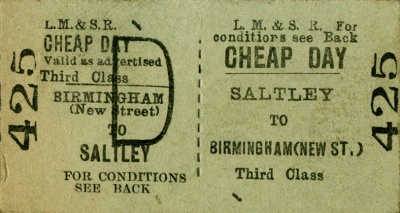

Points to note are the appearance of the cheap day return and the

quite phenomenal increase in third-class travel ― much more so than

of first or second-class ― apparently brought about by reduced

fares, although the introduction of covered third-class carriages

probably played a part.

|

Stockton and Darlington

Railway 2nd-class compartment.

This carriage had

compartments for both 1st and 2nd-class passengers.

Comfortable padded seating was provided in 1st-class ―

which had additional windows ― wooden benches in 2nd.

As on the stagecoaches of the time, passengers’ luggage

was stored on the roof while the guard occupied a

rooftop seat (in all weathers). |

Another potential cost-saving

for the travelling public was that railway companies carried

children under the age of ten free, or for a reduced fare, although

this concession sometimes gave rise to debate, as illustrated in

this Punch cartoon from later in the century:

|

Guard (taking

half-price ticket).

Dignified Little One. |

“Surely

Miss, that young lady is over ten; are you not Miss?”

“Pray,

are you not aware Guard, that it is extremely rude to

ask a lady her age?” |

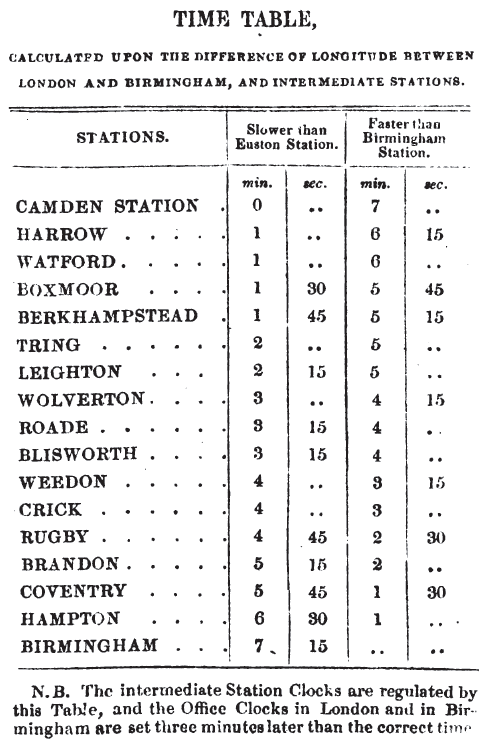

To return to what the Company considered its ordinary business, the original timetable listed

eight trains a day in each direction, of which one terminated at

Wolverton. The two daily mail trains were the expresses of their

age, their timings being regulated by the Postmaster General, for

The Royal Mail soon recognised the potential that railways

offered for streamlining the nation’s postal service. Mail was first carried

by train on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830. In 1838,

the Grand Junction Railway introduced the first travelling post office

between Birmingham and Warrington using a converted

railway horse-box operated by three mail sorters. |

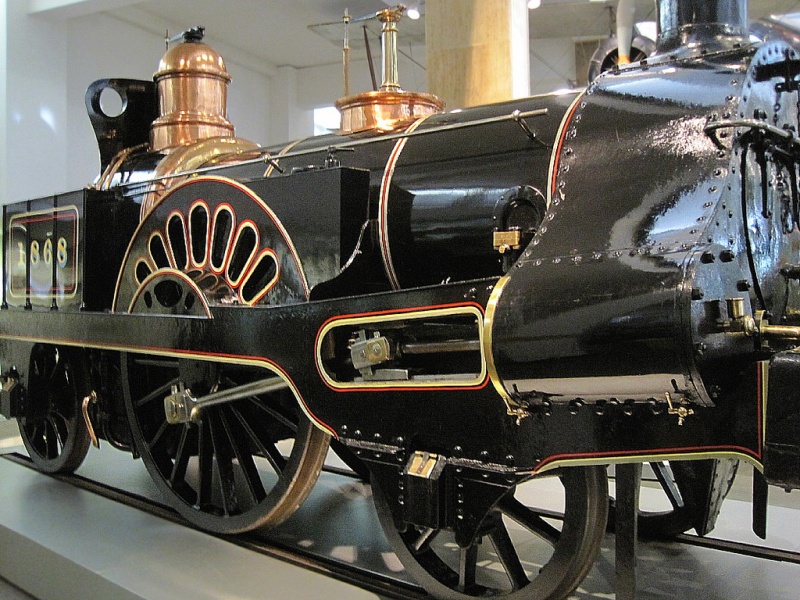

Grand Junction Railway travelling

post office (replica), National Railway Museum, York.

Equipment (ca. 1890) used to transfer

mail bags to and from a train travelling at speed.

|

Also in 1838, the London and Birmingham Railway introduced the first lineside

apparatus designed to pick up and drop down mail from trains travelling at speed. This was followed in 1848 by an improved system, with moveable nets

fixed to both train and the lineside apparatus. The ‘Travelling Post Office’, as

it became known, was so successful that it gave rise to the

‘Railways (Conveyance of Mails) Act’ later that year, which required

all railway companies to carry mail under the direction of

the . . . .

“. . . . Postmaster General, by Notice in

Writing under his Hand delivered to the Company of Proprietors of

any such Railway, to require that the Mails or Post Letter Bags

shall from and after the Day to be named in any such Notice (being

not less than Twenty-eight Days from the Delivery thereof) be

conveyed and forwarded by such Company on their Railway, either by

the ordinary Trains of Carriages, or by special Trains, as Need may

be, at such Hours or Times in the Day or Night as the Postmaster

General shall direct, together with the Guards appointed and

employed by the Postmaster General in charge thereof, and any other

Officers of the Post Office; and thereupon the said Company shall,

from and after the Day to be named in such Notice, at their own

Costs, provide sufficient Carriages and Engines on such Railways for

the Conveyance of such Mails and Post Letter Bags to the

Satisfaction of the Postmaster General, and receive, take up, carry,

and convey such ordinary or special Trains of Carriages or

otherwise, as Need may be, all such Mails or Post Letter Bags as

shall for that Purpose be tendered to them . . . . ”

Cap. XCVIII., An Act to provide

for the Conveyance of the mails by railways. R.A. 14th August

1838.

In the first London and Birmingham Railway timetable, the

day mail departed from Euston at 9.30 a.m. and from Birmingham at

8.30 a.m. The journey took five hours, calling at Tring, Wolverton, Weedon, and Coventry; the night mail took

30 minutes longer. Additionally, there was one first-class train in

each direction ― also a five hour journey ― stopping additionally at Watford, Blisworth and Rugby,

and five mixed

trains, which performed the journey in five and a half hours stopping at

all stations (i.e. including Harrow, Boxmoor, Berkhamsted,

Leighton, Bletchley, Roade, Blisworth, Crick, Brandon and Hampton). However, arriving at a station in time to catch a scheduled train

depended on knowing

the difference between ‘local time’ and that advertised in the railway timetable.

Today, clocks across Great Britain are set

to either Greenwich Mean Time or

British Summer Time depending on the time of year, but this wasn’t always so. Before the

electric telegraph could be used to broadcast accurate time

signals nationwide, time had to be determined locally, midday being

when the Sun appeared on the local meridian. But taking account

of the

speed of the Earth’s rotation, for every 15º of longitude between

two points there is a

difference of one hour in the time when midday occurs. For example,

the Sun is on the meridian (i.e. midday) of Birmingham some 7

minutes and 15 seconds later than in London, and this difference was

reflected in how clocks were set locally. Thus, for stations

along their lines railway companies published the

differences between local time and the times that appeared both in their timetables

and on their station clocks:

Cornish’s Guide and Companion to

the London and Birmingham Railway (1839).

On 22nd September 1847, the Railway Clearing House (dealt with

below) decreed that “GMT be adopted at all

stations as soon as the General Post Office permitted it”.

Then, on the London and North Western . . . .

“. . . . as soon as the railway was opened through from London to

Holyhead in 1848 the company enforced standardisation according to

Greenwich time. Each morning an Admiralty messenger carried a

watch bearing the correct time to the guard on the down Irish Mail

leaving Euston for Holyhead. On arrival at Holyhead the time

was passed on to officials on the Kingstown boat who carried it over

to Dublin. On the return mail to-Euston the watch was carried

back to the Admiralty messenger at Euston once more. This was

a practice which was taken over from the days of the mail coach and

carried on until the outbreak of the Second World War, by which time

the spread of telegraphy and the radio had long since rendered it

superfluous. Scottish independence was further undermined by

the irresistible spread of the railway. The Caledonian Railway

felt obliged, for reasons of business efficiency, to adopt Greenwich

time from the 1st December 1847.”

From The

Transport Revolution from 1770, Philip S. Bagwell (1974).

By

1855, when Greenwich time signals could be transmitted throughout the

telegraph system, it was estimated that 98 percent of Great Britain’s towns and cities were

synchronised with GMT. However, it was not until 2nd August 1880

that a unified standard time for the whole of Great Britain achieved

legal status:

“Whenever any expression of time occurs in

any Act of Parliament, deed, or other legal instrument, the time

referred to shall, unless it is otherwise specifically stated, be

held in the case of Great Britain to be mean Greenwich time, and in

the case of Ireland, mean Dublin time.”

From The Statutes (Definition of

Time) Act, 1880, 43 & 44 Vict. c. 9.

――――♦―――― |

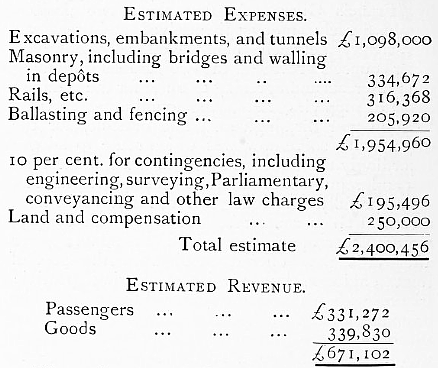

|

RETURNS TO INVESTORS

The Company issued its first circular to

prospective investors in January, 1831, in which were published the

Directors’ initial

estimates of construction costs and the revenues they expected from passenger and goods traffic:

Passenger traffic got off to a good start,

for even on the partial opening of the line sheer curiosity .

. . . .

“. . . . brought thousands of

passengers; but in the third class open carriages the dust from the

roofs of the tunnels and the newly made line, and the hot cinders

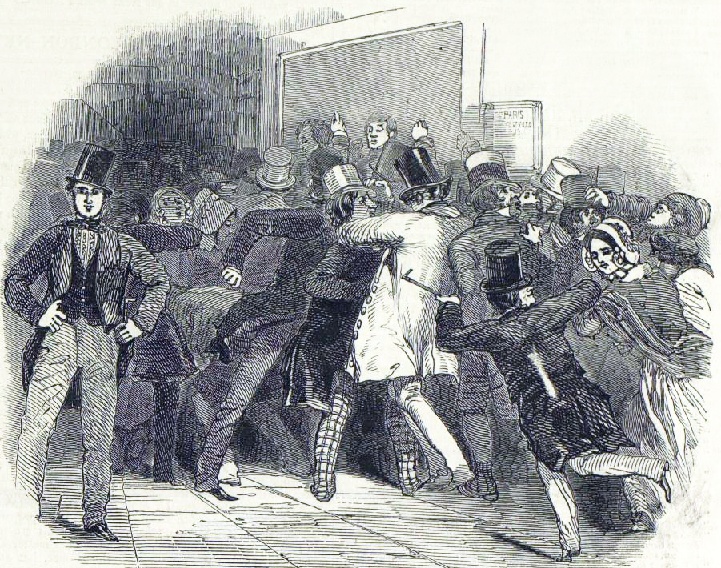

from the engines, gave them rough travelling. On October 16th, 1837,

the line was further opened to Tring, and on April 9th, to Denbigh

Hall. The stage coaches and mails were conveyed on carriage-trucks

to Denbigh Hall, thence by road to Rugby, and the rest of the

journey by rail to Birmingham. The stations were enlivened by

the sound of the bugle, but the coach-guards were disgusted with

their outside ride on the railway. The railway guards also had an

unpleasant time, for, adhering to old usage they too rode outside on

the top of the carriage, where, amidst other disagreeables, their

clothes sometimes caught fire. The roadside stations were enclosed

with lofty iron railings, within which the passengers were

imprisoned until the train arrived; they were then permitted to rush

out to take their places, for which they sometimes had to join in a

free fight . . . . The clatter caused by the stone blocks, which

were used before the wooden sleepers replaced them, added to the

unpleasantness of the journey. Thus the success of the new mode of

conveyance was not then established in the popular mind; and coach

proprietors and others interested in its expected failure, still

hoped on, and in many cases lost money by their lingering belief in

the old system.”

Fifty Years on the London and

North-Western Railway, David Stevenson (1891).

Contrary to what the Directors expected, the

benefits of faster railway conveyance were not so quickly recognised

by the shippers and consignees of goods as they had been by passengers, where the general trend was that more journeys

by rail were being made than

had previously been made by road:

“The attention of the directors has been

sedulously given to the means by which the merchandise and cattle

traffic may be extended, and they are taking such measures as appear

to them conducive to this end. The proprietors will, however,

recollect that this description of traffic will be much longer in

accommodating itself to the railway than the passenger traffic.”

Half-yearly meeting reported in

The Morning Post, 8th February 1840.

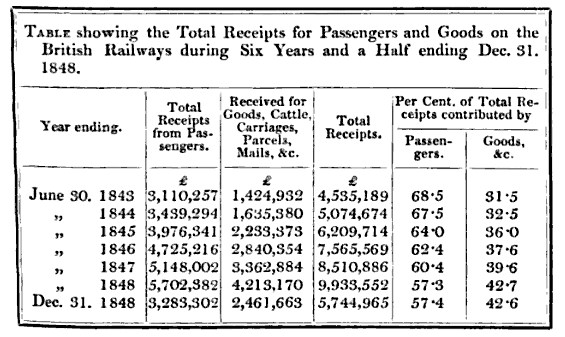

During the Railway’s first complete year of operation ― and despite the “rough travelling” and the “clatter caused by

the stone blocks” ―

passenger traffic earned revenue of £500,000, well above

the Company’s 1831 projection (£331,272). However, goods

traffic did not fare nearly so well, with revenue of

£90,000 falling well below estimate (£339,830). Some

types of freight business had at first to be won from the canal

companies and from other

sources ― for instance cattle, later to become a profitable source of freight

revenue, were driven into London along the

high roads. In 1819, the travel writer John Hassell, while visiting

the Grand Junction Canal at Tring, reported seeing . . . .

“. . . . herds of cows grazing, and

observed a fresh drove of sucklers with their calves coming up to

remain for the night, and we found, upon enquiry, that this inn

[The Cowroast Inn] was one of

the regular stations for the drovers halting their cattle for

refreshment; hence I should suppose, the proper name is the Cow

Rest, or resting place of those animals, for along the road, and all

the way through the breeding and grazing parts of Bucks,

Bedfordshire, and Northamptonshire, there is a perpetual supply of

cows passing to the Capital . . .”

A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal

in 1819, John Hassell.

The Board did not at first consider deadweight freight, such as coal and stone,

to be profitable, these being commodities which they felt more appropriate to canal

transport where they had been the staple fare from the very start. But attitudes, especially to coal, gradually changed, and . . . .

“. . . . for more than a hundred years after 1850

the movement of coal was the bread and butter of British railways,

the tonnage carried being always well over half the total volume of

freight traffic. In 1865, for instance, the quantity of coal carried

by rail was 50 million tons compared with 13 million tons of other

minerals (principally iron) and nearly 32 million tons of general

merchandise.”

The Transport Revolution 1770-1985,

Philip S. Bagwell (1974).

Indeed, trainloads of coal were later to choke the line into London,

leading, in 1859, to a third track being laid between Willesden and

Bletchley in an attempt to relieve the congestion.

|

|

|

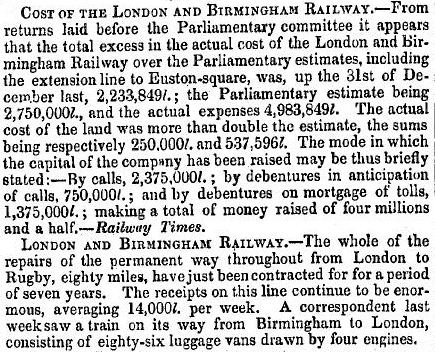

The

Weekly Herald, 27th October

1839 |

Other than the traffic figures, an item referred to in the Secretary’s Report for

the first year of operation was

the cost of repairs to stations and the permanent way, in

particular, the continuing expense of repairing damage dues to

slippage ― “. . . . the late extraordinary and continued rains,

acting upon works of great magnitude and recent formation, caused a

more than ordinary subsidence of all principal embankments . . . .” In an effort to reduce its maintenance costs, the Board had outsourced

civil engineering repairs at a fixed price per mile, but there were “a few embankments and cuttings,

which, from their peculiar liability to slips, could not well be

contracted for at present” and they were excluded from this arrangement.

In these cases repairs would “by the conditions of the contract, to be

paid for as extras for a limited period.” Indeed, the line was to

experience further substantial slips, such as that in

Bugbrooke

cutting in 1842.

At the half-yearly meeting held in February 1841, the Secretary was

able to report that traffic for the six months ended December 1840

exceeded that of any preceding half-year, and that revenue of

£406,040 was £61,846 more than in the preceding period. Despite the

initially poor performance of goods traffic, the dividend paid to

shareholders for 1839 was just over 8⅓%;

this increased to 8⅞% for 1840, 10 per cent for 1841, and in 1842 it

peaked at just over 11 per cent (£100 ordinary shares were

then changing hands for as much as £223) before dropping back to 10%

for 1843. |

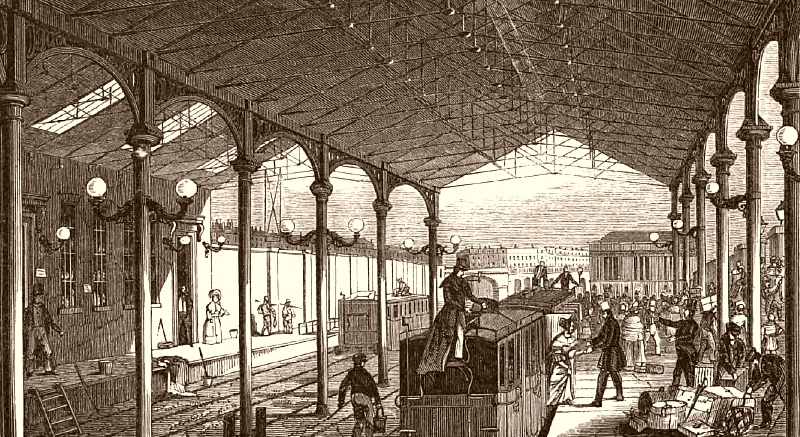

The arrival platform at Euston,

c.1839.

――――♦――――

SAFETY AND REGULATIONS

Bedsides turning in a good profit for its shareholders, the Railway was also

achieving a good safety record, which undoubtedly helped encourage

passenger travel in an age when for most its use was a

considerable step into the unknown. Take, for example, the

fear of passing in a train through a tunnel, which appears to have

caused some prospective passengers great unease to the extent that

the Company felt obliged to obtain several suitably qualified

professional opinions:

“Great prejudice once existed against

tunnels, arising entirely from ignorance; and the directors in order

to quiet the minds of the public, had a special visit to the

Primrose-hill Tunnel made by Drs, Paris and Watson, Surgeons

Lawrence and Lucas, and Mr. Phillips the Lecturer on Chemistry ― the

object being to ascertain the probable effect of such a tunnel on

the health and feelings. The atmosphere of the tunnel was found to

be dry, of an agreeable temperature, and free from smell. The lamps

of the carriages were lighted; and in their transit inwards, and

back again to the mouth of the tunnel, the sensation experienced was

precisely that of travelling in a coach by night, between the walls

of a narrow street. The noise did not prevent easy conversation, nor

appear to be much greater in the tunnel than in the open air.

Judging from this experiment, and knowing the ease and certainty

with which thorough ventilation may be effected, these gentlemen

were decidedly of opinion that no danger occurred in passing through

well-constructed tunnels; and that the apprehensions which had

been expressed, that such tunnels are likely to prove detrimental to

the health and unpleasant to travellers, were perfectly futile and

groundless; and to these opinions they all signed their names.”

The London and Birmingham

Railway, Roscoe and Lecount (1839).

Regardless of the travelling public’s fear of the unknown,

during the Railway’s first year of operation there had been no

serious accidents to passengers, which the Secretary attributed in

his half-yearly report

to the careful observance of the Company’s well considered “regulations”:

“In referring to the

progressively-increasing traffic of the railway, as evinced by the

half-yearly reports, the directors may be allowed to notice the

gratifying fact, that out of 1,483,123 passengers, conveyed on an

average sixty-five miles and a quarter each, from the 17th

September, 1838, to the 31st December last, according to the Stamp

Office returns, not one accident attended with loss of life or limb

to a passenger has occurred, although during the whole of this

period the works were undergoing those extensive repairs which are

inseparable from great excavations and embankments, and requiring

the frequent passage along the line of trains heavily laden with

materials. If, then, under these circumstances of disadvantage, the

directors are enabled to exhibit results which in the infancy of the

undertaking could only have been attained by regulations well

considered, and, with few exceptions, carefully observed, it must be

admitted that railways afford ample assurance for the safety of

travelling, and that the London and Birmingham line posses resources

adequate to any extent of traffic.”

Half-yearly meeting reported in

The Morning Post, 13th February 1841.

In the opinion of W. L. Steel, historian of the London and

North-Western Railway, the Company’s regulations

“were somewhat severe”:

“At all the stations on the line was exhibited the following

notice: ‘The public are hereby informed that all the company’s

servants are strictly enjoined to observe the utmost civility and

attention towards all passengers; and the directors request that any

instance to the contrary may be noted by the offended party in a

book kept at each station for that purpose, and called the

Passengers’

Note Book.’

But although the company’s servants were thus ‘strictly

enjoined to observe civility,’

the passengers were by no means without obligations which they had

to carry out, for the company’s bye-laws were both numerous

and stringent. The company announced that ‘upwards of 200 men

are sworn in as special constables and policemen to enforce a proper

attention to the rules of the establishment.’

The rules of the establishment were somewhat severe, and it was some

time before the force of competition caused them to be relaxed; for

instance, on no account were persons allowed on the platform to see

their friends off, dogs were only conveyed at the minimum charge of

ten shillings, whilst there was a rule for preventing the

smoking of tobacco and the commission of other nuisances.”

The History of the London and

North-Western Railway, Wilfred L. Steel (1914).

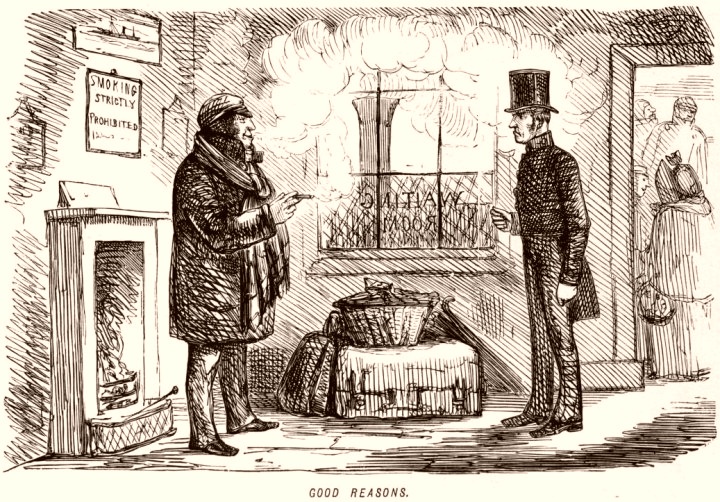

|

Railway Official.

“You’d better not smoke, Sir!”

Traveller. “That’s what my friends say.”

Railway Official. “But you musn’t smoke, Sir!”

Traveller. “So my doctor tells me.”

Railway Official (indignantly). “But you shan’t

smoke, Sir!”

Traveller. “That’s what my wife says.”

(From Punch) |

The “rules of the establishment”

that Steel refers to

were derived from the 1833 Act, which gave to the Company . . . .

“. . . .

full power and authority

from time to time to make such Bye-laws, Orders, and Rules, as to

them shall seem expedient for the good government of the Officers

and Servants of the said Company, and for the regulating the

proceedings, and reimbursing the expenses of the said Directors; and

for the management of the said undertaking in all respects

whatsoever; and from time to time to alter or repeal such Bye-laws,

Orders, and Rules, or any of them, and to make others and to impose

and inflict such reasonable fines and forfeitures upon all persons

offending against the same, as to the said Company shall seem meet .

. . .”

Section CLIV., 3 Gulielmi IV. Cap xxxvi., R.A. 6th

May 1833.

. . . . under which authority were published a set of bye-laws,

which, despite Steel’s

reservations, seem no more onerous than those of today ―

indeed, the smoking ban, both on trains and on station premises,

was years ahead of its time, while the

absence of a guard’s van on today’s

trains and the very limited space available on luggage racks imposes

its own restriction on the amount of

“Luggage

accompanying a Passenger”.

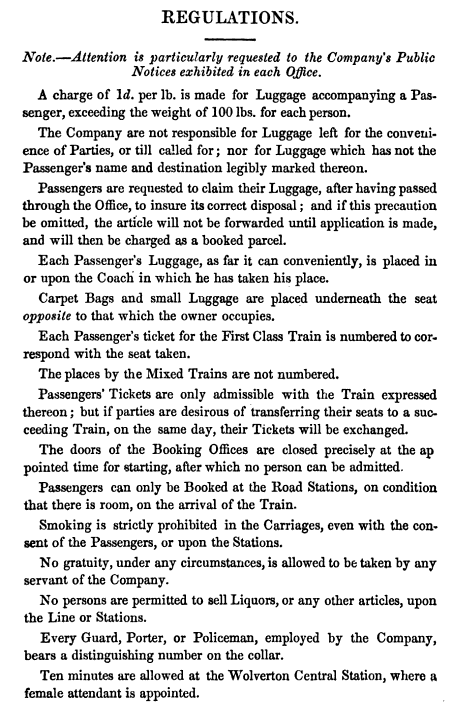

The regulations were often

reproduced in a condensed form in the numerous railway travel guides of the day,

and if they did not represent an attention-gripping read, at least

an attempt to read them probably induced a suitably soporific

remedy to a monotonous journey:

The London and Birmingham Railway

Regulations, c. 1839.

These Regulations were condensed from the “Bye-laws”

at Appendix I.,

which were also reproduced in some of the railway travel guides.

――――♦――――

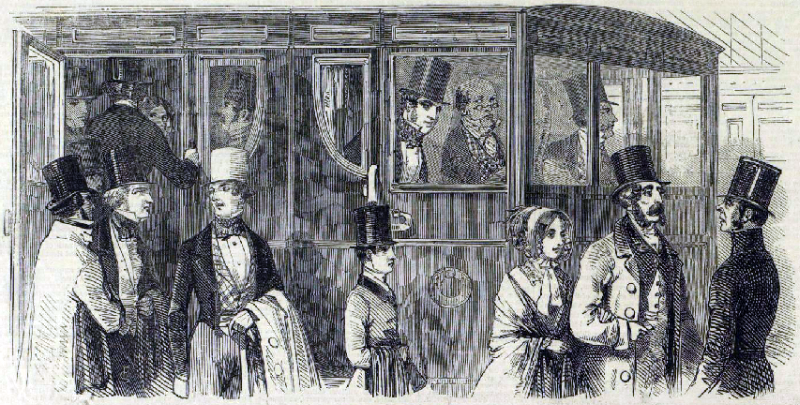

CARRIAGES AND PASSENGERS

The entrance to Euston Station . . . .

“. . . . On that great covered

platform, which with others adjoining it, is lighted from above by

8,797 square yards (upwards of an acre and three quarters) of plate

glass, are to be seen congregated and moving to and fro in all

directions, in a sort of Babel confusion, people of all countries,

of all religions, and of all languages. People of high character, of

low character, of no character at all. Infants just beginning life ―

old people just ending it. Many desirous to be noticed ― many, from

innumerable reasons, good, bad, and indifferent, anxious to escape

notice. Some are looking for their friends ― some suddenly turning

upon their heels, are evidently avoiding their acquaintance.”

The London Quarterly Review,

No. CLXVII. (1849). |

Above: replica Liverpool and Manchester

Railway first-class carriage on display at the National Railway

Museum, York.

Below: perhaps a little cramped, nonetheless 1st-class passengers

travelled in comparative comfort.

Timetables show that when the line was first opened there was only

two classes of travel. First-class carriages

looked much like three stagecoach bodies mounted on a common

chassis. Judging by the Liverpool and Manchester railway example

on display at the National Railway Museum, passengers travelled in

comfortable conditions, if rather cramped by modern standards. In his Road Book of

the London and Birmingham Railway, James Drake describes what a first-class passenger could expect

in 1839:

“Upon examining the internal

fittings up of the carriages, upon which so much of the comfort of

his journey will depend, the traveller will find that the first

class carriages are divided into three entirely distinct

compartments, and these compartments into six divisions (except in

the mails in which there are only four) so that each traveller has

an entire seat to himself, in which he can recline as freely and

comfortably as in the most luxurious arm chair; and after the shades

of evening have gathered over the scenery, can read the news of the

day, or turn over the pages of our little volume by the light of a

lamp, which is fixed in the roof of the coach.”

Second-class, however, sounded grim, especially for those

travelling in the ‘day coaches’ (see below) in a cold, wet and windy

weather, and to exacerbate their

discomfort the horse-hair buffers between coaches would have added

jolts to the noise and vibration from travelling over rails laid on

stone block sleepers:

“The second class carriages are,

however, of a very different character. These cushionless,

windowless, curtainless, comfortless vehicles, seem to have been

purposely constructed so that the sweeping wind, enraged at being

outstripped in his rapid flight, might have an opportunity of

wreaking his vengeance upon the shrinking forms of their ill-fated

occupants. At night, however, the partnership of the railway with

Messrs. Rheumatism and Co. is dissolved, and even second class

passengers are provided with shelter from the cold and chilling

blast.”

|

|

|

Note the roof

luggage racks and the outside seats for

the guards. |

In

The Iron Road Book and

Railway Companion, Francis Coghlan offers helpful advice

to those unfortunate second-class passengers:

|

“In the second-class carriages, or

rather waggons, there is certainly a preference to be observed. In

the first place, get as far from the engine as possible ― for three

reasons:― First, should an explosion take place, you may

happily get off with the loss of an arm or a leg ― whereas if you

should happen to be placed near the said piece of hot machinery, and

an unfortunate accident really occur, you would very probably be

‘smashed to smithereens’ . . . . Secondly ― the vibration is

very much diminished the further you are away from the engine.

Thirdly ― always sit (if you can get a seat) with your back

towards the engine, against the boarded part of the waggon; by this

plan you will avoid being chilled by a cold current of air which

passes through these open waggons, and also save you from being

nearly blinded by the small cinders which escape through the funnel.” |

When the Company introduced third-class travel, passengers in that

social strata inherited the second-class day coaches, leaving

second-class passengers at least the comfort of compartments

enclosed from the elements.

Most of the Company’s

railway carriages at this date were built by Joseph Wright, formerly a London

coach builder, who in the early part of the 19th century was both

contractor to the Royal Mail and owner of most of the stagecoaches then running between London and Birmingham. Wright was a man

of outstanding ability and foresight. Having closely watched the

birth and early development of the railways, he realised that the

stagecoach era was drawing to a close. In the early 1840s he began

to manufacture railway carriages utilising his company’s

skill and experience of coach building to the full, as is evident from some

of his early railway carriage designs:

“The Company’s establishment at

Euston Station, which is therefore principally for the maintenance

of carriages of various descriptions running between London and

Birmingham, consists of a large area termed ‘the Field,’ where

under a covering almost entirely of plate-glass, are no less than

fourteen sets of rails, upon which wounded or spare carriages lie

until doctored or required. Immediately adjoining are various

workshops, the largest of which is 260 feet in length by 132 in

breadth, roofed with plate-glass, lighted by gas, and warmed by hot

air. In this edifice in which there is a strong smell of varnish,

and in the corner of which we found men busily employed in grinding

beautiful colours, while others were emblazoning arms on panels, are

to be seen carriages highly finished as well as in different stages

of repair. Among the latter there stood a severely wounded

second-class carriage. Both its sides were in ruins, and its front

had been so effectively smashed that not a vestige of it remained. The iron-work of the guard’s step was bent completely upwards, and a

tender behind was nearly filled with the confused debris of its

splendid wood-work ― and yet, strange to say, a man, his wife, and

their little child, who had been in this carriage during its

accident, had providentially sustained no injury.”

The London Quarterly Review,

Volume LXXXIV (1849).

As early as 1844, Wright patented improvements to railway carriages,

in which 4, 6 and 8-wheeled bogies appeared, ideas that in many

respects were 50 years in advance of general carriage-building

practice. |

|

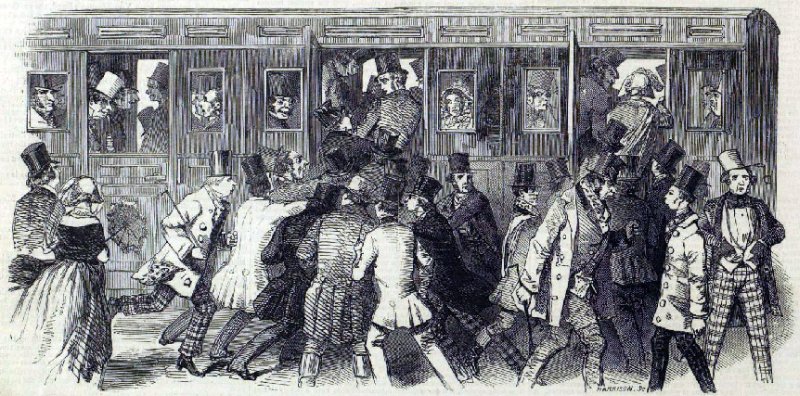

Some depictions of early railway travel,

from the Illustrated London News, 1847 . . . .

‘Epsom races’

|

|

|

|

The ticket office. |

|

|

|

First-class. |

|

|

|

Second-class. |

|

|

|

Third-class. |

|

As the railways grew, the demand for rolling stock was such that

Joseph Wright decided to build a new factory where more space was

cheaply available. Lying at the confluence of the London &

Birmingham, the Grand Junction and the Birmingham & Derby Junction

railways, among others, and in a position in close proximity to the

coal and iron districts, Birmingham was a good location.

In 1845, he leased land at Saltley on which to build his new

factory, which, when completed, contained “the

newest and most expeditious mechanical appliances”

and consisted of “workshops,

offices, a wharf and other buildings”

and included “engines, boilers

and other machinery”.

After becoming established at Saltley, Wright disposed of his works

in London. When he died in 1859, the business was continued by his

son Joseph under its original name until, in 1862, it became the

‘Metropolitan Railway Carriage and Wagon

Company Ltd’. The firm later became

part of ‘Metro-Cammell’,

and today is a constituent

of the Alstom group.

An unusual class of passenger soon to be conveyed in the

carriages of the London and Birmingham Railway was

the military ― probably the only instance of passenger traffic being

won from the Railway’s competitor, the Grand Junction Canal Company,

who had formerly undertaken troop movements. In early Victorian England, there were

very few police forces to

suppress civil unrest, and when such action was felt necessary, the Government and factory owners

called in the

army, the Peterloo Massacre (Manchester, 1819) being the most

notorious occasion. The year 1842 is believed to be the

first in which the new railway system was used to deploy troops to

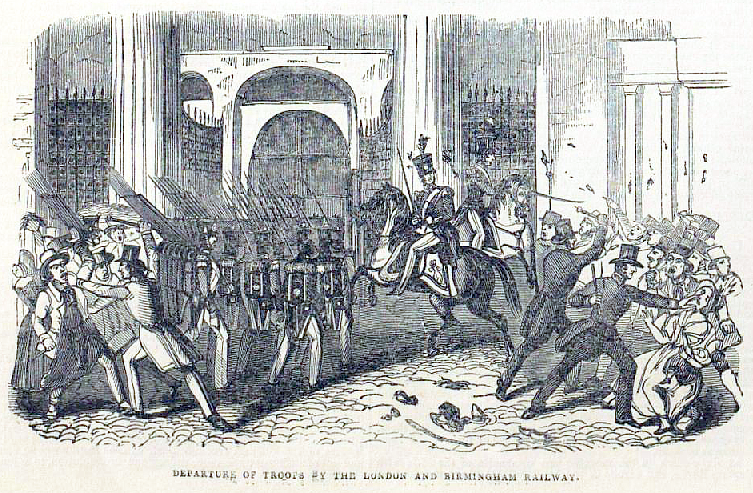

quell civil unrest ― the picture below shows troops marching through the

Euston Arch amidst a throng of jeering protesters toward the train

that will take them to Manchester.

Troops marching through Euston’s

Doric Arch, en route to Manchester,

The Illustrated

London News, 20th August 1842.

The reason for this particular troop movement is tied up with the

political situation of the day, particularly the lack of voting

rights ― very few men and no women were entitled to vote at

elections. Out of this injustice emerged the ‘Chartist’

movement, its name being derived from the formal petition or ‘People’s

Charter’ that listed the movement’s main aims:

1. a vote for all men (over 21);

2. the secret ballot;

3. no property qualification to become

an MP;

4. payment for MPs;

5. electoral districts of equal size;

6. annual elections for Parliament. |

Support for Chartism peaked at times of economic depression and

hunger, and 1842 was a time when many working-class people

badly wanted political reform. Unemployment and near-starvation

brought rioting to Stockport and to Manchester, where workers

protested against wage cuts. Other areas most affected were the Midlands,

Lancashire, Cheshire, Yorkshire, and the Strathclyde region of

Scotland. With Chartist activists in the forefront, demands

for the provisions of the Charter to become law were included with

economic demands. The Government’s reaction was to send in the army to stamp out the

unrest, the troops

being conveyed to the scene of action by train:

“Immediately after the conclusion of the

deliberations of the Cabinet Council, which occupied upwards of two

hours, orders were forwarded from the Horse Guards to Woolwich, for

a party of of the Royal Artillery to hold themselves in instant

readiness to depart for Manchester; and a similar order was

despatched to St. George’s Barracks, Charing-cross, for the

departure of the third battalion of the Grenadier Guards, stationed

at that barracks, for the same destination, via the London and

Birmingham Railway . . . . About six o’clock a detachment of 150 of

the Royal Artillery left Woolwich, having in charge four heavy

pieces of ordnance, each drawn by four horses, and accompanied by

numerous waggons, containing ammunition, baggage, stores, and

accoutrements, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Smith, and

proceeded at the terminus of the London and Birmingham

Railway . . . . LONDON AND BIRMINGHAM

RAILWAY, SUNDAY,

― This morning, as early as nine o’clock, another troop of Royal

Horse Artillery arrived from Woolwich at the Euston Station of the

London and Birmingham Railway, with three field pieces and

ammunition. About 4 o’clock, the Quartermaster of the 34th Foot,

from Portsmouth, attended by an orderly, arrived, and ordered

refreshment to be procured from the various public-houses for that

regiment, which was en route by the South Western Railway from

Portsmouth. The great excitement at this time prevailed, the

Quartermaster being obliged to be escorted from the various

public-houses by the police. In an hour after, two waggons, laden

with ammunition and guarded by several soldiers of the 34th came up,

and was shortly after followed by the regiment, under the command of

Colonel Airey, consisting of 600 men. On their arrival they were

greeted the the most discordant yelling by the mob, and it was as

much as the police could do to prevent them from forcing an entry

into the railway yard.”

The Illustrated London News,

20th August 1842.

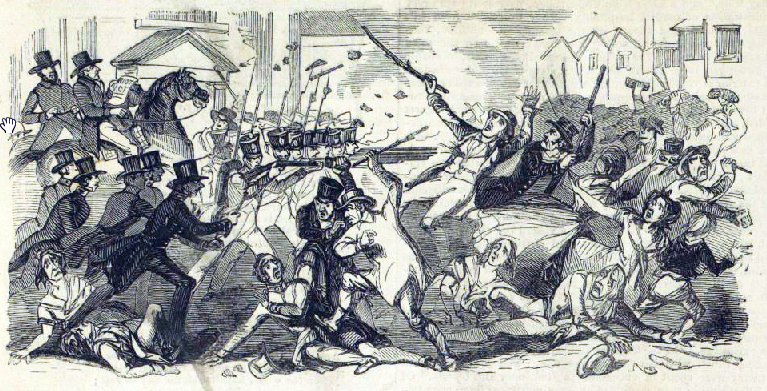

Troops firing on protesters at

Preston.

The Illustrated

London News, 20th August 1842.

But in general, the early travel writers were complimentary

about the treatment they received on arriving at Euston, albeit from

the Company’s officials rather than

a howling mob. The following is a

typical introduction to Euston Station:

“On arriving in a cab at the Euston

Station, the old-fashioned traveller is at first disposed to be

exceedingly pleased at the new-born civility with which, the instant

the vehicle stops, a porter opening its door with surprising

alacrity, most obligingly takes out every article of his luggage;

but so soon suddenly finds out that the officious green,

straight-buttoned-up official’s object has been solely to get

the cab off the premises, in order to allow the string of variegated

carriages that are slowly following to advance; in short, that while

he was paying to the driver, say only two shining shillings, his

favourite great-coat, his umbrella, portmanteau, carpet-bag, Russia

leather writing-case, secured by Chubb’s patent lock, have all

vanished; he poignantly feels like poor Johnson, that his ‘patron

has encumbered him with help;’ and it having been the golden maxim

of his life never to lose sight of his luggage, it gravels and

dyspepsias him beyond description to be civilly told that on no

account can he be allowed to follow it, but that ‘he will find it on

the platform;’ and truly enough the prophecy is fulfilled; for there

he does find it on a barrow in charge the very harlequin who whipped

it away, and who, as its guardian angel, hastily muttering the words

‘Now, then, Sir!’ stands beckoning him to advance . . . .

Now them ma’am, is this your

luggage?

A John Leech cartoon from Punch.

When every person has succeeded in

liberating himself or herself from the train, it is amusing to

observe how cleverly, from long practice, the Company’s

porters understand the apparent confusion which exists. To people

wishing to embrace their friends ― to gentlemen and servants darting

in various directions straight across the platform to secure a cab

or in search of private carriages ― they offer no assistance

whatever, well knowing that none is required. But to every passenger

whom they perceive to be either restlessly moving backwards and

forwards, or standing still, looking upwards in despair, they

civilly say ‘This way Sir!’ ‘Here it is Ma’am!’ ― and

thus, knowing what they want before they ask, they conduct them

either to the particular carriage on whose roof their baggage has

been placed, or to the luggage van in front of the train, from which

it has already been unloaded onto the platform.”

The London Quarterly Review,

No. CLXVII. (1849).

――――♦――――

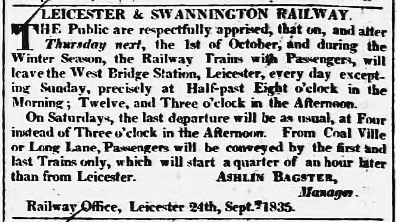

ASHLIN BAGSTER AND ADMINISTRATION

The names of several people who played some part in the

early history of the London and Birmingham Railway crop up, and then disappear

just as suddenly. Peter

Lecount (whose name peppers these pages) is one such person,

another is Ashlin Bagster.

If a large organisation is to achieve its

business objectives

it requires an administrative system ― a bureaucracy

if you like ― through which the board can

exercise control. The London and

Birmingham Railway Company was no exception and it is in this

context that the name of Ashlin Bagster appears fleetingly.

Had he lived beyond his thirtieth birthday he might ― as the two

references to him suggest ― have achieved great things in railway

company administration.

|

|

|

Leicester Journal,

25th September 1835. |

While still in his early twenties, Ashlin Bagster was appointed

Manager of the 16-mile Leicester and Swannington Railway.

Engineered by Robert Stephenson and opened in 1832, the line was

essentially a colliery railway built to serve local pits, but it

supplemented its modest income by carrying passengers.

Following a level crossing collision between a locomotive and a

cartload of farm produce, Bagster suggested to George Stephenson

that locomotives be fitted with steam whistles, and Stephenson

duly patented his ‘steam trumpet’. It is to Stephenson that credit for the

invention of the steam locomotive whistle is generally given.

Bagster appears to have been sufficiently efficient in his role for

Robert Stephenson to suggest his appointment as General Manager of

the London and Birmingham Railway, a considerable

advance in status:

“We may, in the course of this work, digress a little upon the

effects which this new system of travelling will produce; but we do

not propose to stop here, further than to notice that the whole code

of laws regulating the immense machinery of the passenger traffic of

this vast undertaking, may be said to have emanated from Ashlin

Bagster, Esq., a gentleman who holds the appointment of agent to the

Company for this department of traffic; and under whose management

we have no doubt, from his talents and the experience he possesses

in such undertakings, the most beneficial results will accrue to the

shareholders of the concern; whilst the public will have every

reason to find that their comfort and safety have been alike

provided for.”

The London and Birmingham Railway, Roscoe

and LeCount (1839).

Much of Bagster’s correspondence survives in the National Archives.

The index to the collection alone makes interesting reading, for it

illustrates succinctly the wide diversity of subjects that Bagster

was called upon to deal with. The following are just a few

examples:

|

CORRESPONDENCE |

|

4.1.1837 |

Two

receiving houses for parcels in London needed. |

|

23.1.1837 |

The parcels

vans cost £35-£40 each, we need three. Tarpaulins are

required to protect luggage on the roof. |

|

9.5.1837 |

12 feet

turntables delivered. |

|

27.6.1837 |

We have no

drawbar chains to any of the coaches. |

|

19.7.1837 |

The sidings

and turnpoints at Boxmoor are decidedly backward. |

|

21.7.1837 |

re erecting

of small dwellings at each road station. |

|

24.7.1837 |

Method of

accounts presentation. |

|

26.7.1837 |

Application

to sell newspapers at stations. |

|

7.8.1837 |

O’Connor

the constable fined 20/- by the Magistrates for being

drunk. |

|

24.8.1837 |

476 sheep

successfully loaded as trial from Boxmoor. |

|

26.8.1837 |

Complaints

of derailments and damage. |

|

4.9.1837 |

Intoxicated person injured jumping out of train to

rescue hat. |

|

4.9.1837 |

Application from porter whose arm was fractured between

buffers and amputated. |

|

25.9.1837 |

Derailment of passenger train near Harrow road gates. |

|

1.10.1837 |

Is the Parcels Office to open on Sundays? |

|

27.2.1838 |

Bye laws notices to be framed and exhibited. |

|

2.3.1838 |

Inspectors are selected from the most deserving of the

police. |

|

13.5.1838 |

Report two cows killed on the line. |

|

1.8.1838 |

Report of station clerk bad conduct and was dismissed. |

|

25.8.1838 |

Report lighting the mail and second class carriages ―

cost of lamps. |

|

12.9.1838 |

Fish traffic ― our proposed charge is 1½d a pound. |

|

18.9.1838 |

Re additional clerks, and salary increases for junior

clerks etc. |

Taking one letter from the bundle, Bagster wrote to the Company

Secretary, Richard Creed, on the 20th April 1837, asking him to

bring to the Committee’s attention the following “principal

preliminary arrangements for the conveyance of passengers”, on

which he awaited top management decisions:

Passenger fares, and whether the trains are intended to travel in

classes, or mixed carriages.

Fares of children under 10 years of age.

Weight of luggage to be allowed to each passenger.

Rate for conveying 4 wheeled carriages.

ditto 1 horse 4 wheeled and gigs.

Arrangements for persons [travelling] in their own vehicles.

Rate for conveying 1 horse or pony.

ditto two

ditto three (one truck will contain three

horses.)

Scale of rates for conveyance of parcels.

Protecting notice boards, and boards of rates.

Numbering of carriages, and whether to extend to any, but the first

class coaches, lighting of the coaches by lamps.

Admission of coaches into station yard.

Mode of appropriation of area in front of station.

Organisation of police force, on station and the line.

Appointment of clerks, guards (2 to each train), porters,

gatekeepers, enginemen, firemen and bankriders.

Uniforms of guards, policemen and porters.

Supply of gas (of gasometer).

Supply of water.

Clocks and bells to announce starting.

Office fitting, safes, heating apparatus.

Insurance of buildings and carriages.

Hours of departure

Sunday travelling

City receiving house for parcels.

Charge for booking or delivering parcels.

In the same letter, Bagster suggested to the Committee that the

following “should form part of the general regulation of traffic”:

No gratuity permitted to attendants.

Smoking prohibited on the station, or in carriages.

No dogs admitted (not even lap dogs).

Applicants intoxicated to be excluded.

Passengers behind time, to have half fare returned, if on same day.

Passengers losing tickets to pay again.

Trains never to stop but at fixed stations.

Company’s servants or their friends, prohibited travelling free on

the railway.

Bagster did not remain with the Company for long. He

left to take up an appointment as Manager of the North Midland

Railway, but his tenure there was also short lived, for he died in July

1839.

“I was introduced to Mr. Ashlin Bagster, who had been appointed,

at the nomination of Mr. Robert Stephenson, to be the first manager

of the London and Birmingham line: a tall and serious-looking

gentleman, who shook his head when, at his bidding, I copied a

letter as a specimen of my hand-writing. I was, however, appointed a

cadet in his office at a salary of twenty pounds per annum; the

first clerk to the first manager of the railway! . . . . The

details of the preparation for the opening fell upon Mr. Bagster, at

a salary of £400 per annum, and his small band of assistants at

Euston, at salaries from £20 to £150. This gentleman provided many

of the methods and forms which were adopted afterwards by most of

the railways, and which still remain in use. Of those who took part

in the preparations only a few rose to distinction in the

development of railways. Mr. Bagster left the London and Birmingham,

and took service on a northern line, but died early . . . .”

Fifty years on the London & North Western

Railway, by David Stevenson (1891).

――――♦――――

THOMAS EDMONDSON AND THE RAILWAY TICKET

A booking office.

When the Railway first opened, from the passenger’s

perspective the method of booking a seat remained virtually

unchanged from the stagecoach era ― indeed, that was the

origin of the term ‘booked’:

“Passengers were ‘booked’

just as they were for the stage coaches, and their names and

destination all written in the book, and it was some

considerable time before tickets were introduced; everything

connected with the passenger department was copied from the coaches,

and for some time a trumpeter played a tune on the horn as the

trains departed from the terminal stations.”

History of the London and North-

Western Railway, Wilfred L. Steele (1914).

Steele is here referring to the Liverpool and Manchester Railway,

but in Fifty Years on the London and North-Western Railway

David Stevenson gives a similar description of London and Birmingham

practice, although by the time the Railway had opened throughout the system appears to have been

somewhat streamlined by the use of colour-coded tickets:

“On paying your fare at either of the

Booking offices in London or at the stations, tickets are given,

coloured according to the class carriage you are going in. In London

they give pink for the first class, white for the second: along the

line, and at Birmingham, the colours are ― first class, yellow,

second, blue.”

The Iron Road Book and Railway

Companion, Francis Coghlan (1838).

Colour coding assisted aspects of railway accounting and made what

today is referred to euphemistically as ‘revenue protection’ easier

for the ticket inspector:

“The tickets, which should be of different

colours for up and down, and for each class of carriage, should be

collected by the guards from the passengers at the last station

before the termination of their journey, the upper guard taking the

first class, and the under the second class, a ticket collector

accompanying the upper guard to receive the tickets and money where

excess fares occur, and a trusty porter doing the same with the

under guard. The tickets, when collected, should be given to the

head booking-clerk for assortment, and by him sent to the principal

office the following morning, except where passengers get down at

any out-station, in which case their tickets are to be collected by

a man stationed for that purpose at a wicket, where only one person

can get through at a time; and the collector must see that each

ticket is issued to take the bearer to the station where he has got

down. When passengers are going from this last station to the

terminus, they should all be put in the carriages previous to the

guard going round to collect the tickets, that he may get theirs

also.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Peter Lecount (1839).

|

|

|

An Edmondson Ticket. |

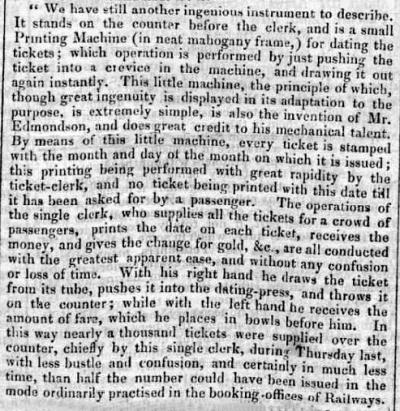

Two further important refinements were soon made to the ticketing system. The first to arrive, in 1839, was the

‘Edmondson railway ticket’, which

formed the basis of a system for recording the

payment of railway fares and accounting for the revenue received.

It was the brainchild of Thomas Edmondson (1792-1851), who introduced

it on the Manchester and Leeds Railway to replace the stagecoach system, by

which a booking clerk wrote out a ticket ― name, destination and fare ― in

manuscript for each passenger, the counterfoil being retained in the booking

office. While this long-winded task was being performed, long queues formed at busy stations.

The pre-printed Edmondson tickets ― a card cut to 1 7⁄32 by 2 1⁄4 inches, with a nominal thickness of 1⁄32

inches ― were not only faster to issue, but their serial numbers provided

accountability, since, at the end of each day, ticket clerks were required to

reconcile their takings against the serial numbers of the unsold tickets.

This

prevented unscrupulous clerks from pocketing the fares. Tickets of

different types and to different destinations were stored in racks within a lockable cupboard, where the lowest remaining number of each issue was visible. Different

colours and patterns helped distinguish the different types of tickets, which

were date-stamped on issue.

|

|

|

|

|

Carlisle

Journal, 31st August 1839. |

Edmondson-type ticket

dating machine and box of date stamps. |

|

Example of an Edmondson cabinet and ticket

storage racks.

――――♦――――

THE RAILWAY CLEARING HOUSE

The Edmondson ticket did not enter widespread use until after the

creation of the second important refinement in the ticketing system,

the ‘Railway Clearing House’. This organisation was set up to manage the allocation of passenger and

freight revenue collected by railway companies for journeys that were to be

made, in part, over the lines of different companies.

The Edmondson system coped well with ticketing and accounting for journeys made over a single company’s

system, but as the railway network grew, single journeys became longer and

inevitably crossed the boundaries of other railway systems. Thus, ‘through

charging’ became desirable to avoid passengers having to

re-book their journey wherever this occurred, a requirement that applied equally

to freight. [2] A system was therefore required to

enable passenger and freight revenue to be divided equitably between the various

railway companies that

had provided whatever resources were necessary to complete a journey.

|

|

|

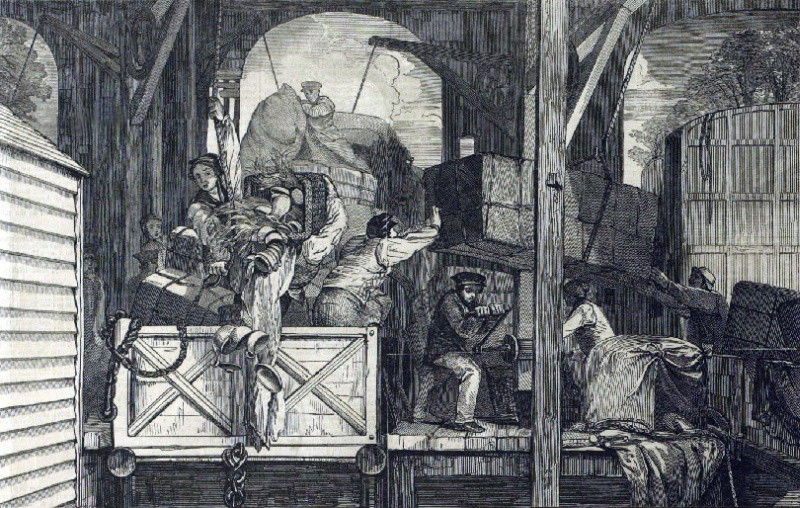

These two illustrations

show the mayhem that resulted during the transhipment of

goods and passengers at Gloucester, where Brunel’s broad gauge met the standard gauge.

However, they also illustrates the problem resulting

from the absence of ‘through charging’ arrangements

between adjoining railway companies, which the Railway

Clearing House resolved.

|

|

|

In 1842, an

idea that originated within the audit department of the London and Birmingham

Railway led to the formation of the Railway Clearing House (RCH):

“As the railways had not adopted a uniform

system of keeping their accounts, the division of these receipts led to much

controversy between the different lines, and this, in many instances, delayed

the introduction of through facilities. Accordingly, it occurred to Mr. Morison,

an audit clerk [3] on the

London and Birmingham Railway, that if a Clearing House, on the model of the

Bankers’ Clearing House, was established,

and authorised to divide all the through receipts between the different railways

on an uniform system, it would put an end to the bickerings between the

companies, and at the same time lead to the introduction of many new facilities. Mr. Morison brought his scheme to the notice of Mr. Glyn, the Chairman of the

London and Birmingham, and the latter enthusiastically took up the idea, with

the result that in 1842 the Railway Clearing House was started, under the

auspices of nine companies, with Mr. Glyn as Chairman, and Mr. Morison as its

first manager.”

The History of the London & North Western

Railway, Wilfred L. Steel (1914).

In years to come, the RCH was to have enormous impact in enabling the smooth

operation of inter-company accounting and the prompt settlement of outstanding

balances ― it was in the processing of passenger transactions that the

Edmondson ticket came into its own, eventually becoming adopted universally.

Initially, the RCH handled traffic receipts for the through conveyance of goods,

passengers, parcels and live stock between London and Darlington in one

direction, and between Manchester and Hull in the other. Nine railway companies

were admitted to participate in the business, these being the London and

Birmingham, Midland Counties, Birmingham and Derby Junction, North Midland, Hull

and Selby, Manchester and Leeds, Leeds and Selby, York and North Midland, and

Great North of England. By 1845, membership had increased to sixteen companies

operating 656 route-miles of track. In 1842, receipts were £193,246; by

1876, they were upwards of £16,000,000; and by 1933, £34,000,000. [4]

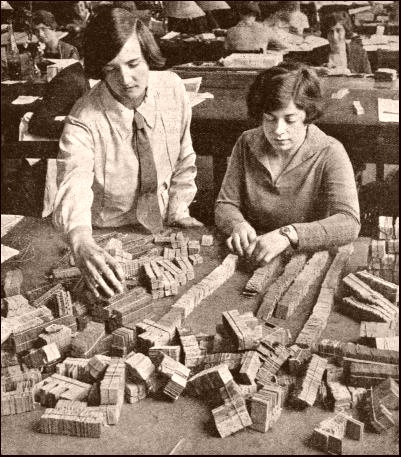

“The traffic returns of the different railway

companies were checked at the Railway Clearing House. The (Edmondson) tickets

surrendered to the collectors at the end of journeys were despatched to the RCH

each month. This illustration shows how they are sorted into order so that the

returns may be checked.”

From Railway Wonders of the World, July 1935.

Sorting railway tickets in the Railway Clearing

House c.1935.

“A

prospective passenger can walk into any station booking-office in Great Britain

and purchase a ticket for practically any other station in the country ― and

that ticket will take him right through to his destination, irrespective of the

ownership of the lines over which he may have to travel.”

From Railway Wonders of the World, July 1935.

So important did the RCH become, that its function became enshrined in law, first

in ‘The Railway Clearing Act (1850)’,

the preamble to which succinctly states the organisation’s

purpose:

XXXI. ― CLEARING HOUSE.

13 & 14 Vict., Cap. xx xiii.

An Act for regulating legal Proceedings by or against the Committee of Railway

Companies associated under the Railway Clearing System, and for other Purposes.

[25th June, 1850.]

Whereas, for some Time past, Arrangements have subsisted between several Railway

Companies for the Transmission without Interruption of the through Traffic in

Passengers, Animals, Minerals, and Goods passing over different Lines of

Railway, for the Purpose of affording, in respect to such Passengers, Animals,

Minerals and Goods, the same or the like Facilities as if such Lines had

belonged to One Company; which Arrangements are commonly known as and in this

Act are designated as the ‘Clearing System’

and which Arrangements are conducted under the Superintendence of a Committee

appointed by the Boards of Directors of such several Railway Companies, which

Committee is in this Act designated ‘the

Committee;’ and the Business of such Committee

has heretofore been and is now carried on at a Building appropriated for the

Purpose in Seymour Street

[now Eversholt Street] adjoining the Euston Station of the

London and North-western Railway Company: And whereas the Clearing System

has been productive of great Convenience to the Public, and of a considerable

Saving of Expense in the Transmission of Passengers, Animals, Minerals, and

Goods over the Lines of the Railway Companies Parties to such Association; but

considerable Difficulty has been experienced in carrying into the Objects of the

Association, in consequence of the Committee not possessing the Power of

prosecuting or defending Actions or Suits, or taking other legal Proceedings:

And whereas George Carr Glynn, Esquire, is the present Chairman,

Kenneth Morison is the present Secretary, of the Committee: And whereas the

Purposes aforesaid cannot be effected without the Authority of Parliament: May

it therefore Your Majesty that it may be enacted and be it enacted; That the

several Companies which at the Time of the of this Act are Parties to the

Clearing System, and every other Company which shall in manner hereafter become

Party to the same, shall be subject to the Provisions of this Act.

Further Acts followed, the main purpose of the of the ‘Railway

Clearing Committee Incorporation Act’

(1897) being to incorporate the RCH and . . . .

“To confer upon the Railway Clearing

House as so incorporated, the power of acquiring, holding, receiving,

possessing, and disposing of lands and other property, and of suing and being

sued, and prosecuting and defending criminal proceedings, and all other usual

and incidental rights, powers, .and privileges of a corporate body.”

The London Gazette, 24th November 1897.

――――♦―――― |

GOODS TRAFFIC

|

The 1836 Act empowered the Company to carry goods in a manner

similar to that of canal companies. Canal companies provided a

waterway on which, for payment of a toll, carriers’ barges could ply laden with

goods that they had contracted to carry. Generally speaking, the

businesses and carriers that used the canals provided their own

wharfs, docks and warehouses. [5] In a

similar manner, the

London and Birmingham Railway Company Act

envisaged that the carriers would bring in the business and that the Company would charge them a toll

for the use of the line, the rate depending on the type of freight

and distance carried. It would also provide

the locomotives and wagons and, for an extra charge, warehouse facilities:

“CLXXI. And be it further enacted, That all

Persons shall have free Liberty to pass along and upon and to use

and employ the said Railway, with Carriages properly constructed as

by this Act directed, upon Payment only of such Rates and Tolls as

shall be demanded by the said Company, not exceeding the respective

Rates or Tolls by this Act authorized, and subject to the Rules and

Regulations which shall from Time to Time be made by the said

Company or by the said Directors, by virtue of the Powers to them

respectively by this Act granted . . . .

“CLXXIV. And be it further enacted, That it shall be lawful for the

said Company and they are hereby empowered to provide locomotive

Engines or other Power for the drawing or propelling of any

Articles, Matters, or Things, Persons, Cattle, or Animals, upon the

said Railway, and to receive, demand, and recover such Sums of Money

for the Use of such Engines or other Power as the said Company shall

think proper, in addition to the several other Rates, Tolls, or Sums

by this Act authorized to be taken.”

3 GUL. IV. Cap. xxxvi. RA 6th

May 1833.

The provision of locomotives was extended in the second Act to

include wagons:

“CXIX . . . . That it shall be lawful for the said Company to

provide or hire, use and employ, locomotive Engines or other Power,

Coaches, Waggons, and other Carriages, and with such locomotive

Engines or other Power, Coaches, Waggons and Carriages, or any other

Coaches, Waggons, and Carriages, to carry and convey, as well upon

and along the said Railway as upon and along any other Railway or

Railways, all such Articles, Matters, or Things, Persons, Cattle, or

Animals, as shall be offered to them for that Purpose, and to make

such reasonable Charges for such Carriage or Conveyance not

exceeding the Amount specified in the said recited Act, as they may

determine on . . . . ”

5 & 6 Gulielmi IV. Cap. lvi.

RA 3rd July 1835.

Thus, in conformity with the Acts’ provisions . . . .

“. . . . The system adopted by the London

and Birmingham Company was the open one of allowing all carriers to

use the line. The railway company stipulated that they should supply

the locomotive power at agreed rates, and that for the use of the

road certain tolls should be levied. [Appendix II.]

These constituted the whole and sole account between the company and

the carriers. The latter collected and delivered the goods, took all

risks upon themselves, and provided they paid to the railway company

its dues, every needful facility was given to them to carry on their

business. The tolls and haulage rate were so regulated, that whilst

on the one hand they contributed a handsome profit to the railway

exchequer, they were on the other sufficiently reasonable to allow

the carriers to conduct their business to a profit. In this there

was mutuality -- an essential ingredient in all business

arrangements. The competition amongst the carriers was the security

which the public had against unfair charges.”

Railway Management, John

Whitehead (1848).

However, the open competition carrying system used by the London

and Birmingham was not adopted universally:

“An opinion pretty extensively prevails

that the railway companies are the carriers of goods on their own

railways; but this is true only to a partial extent. Three modes of

proceeding are adopted by different railways in this respect: ―

1.

as on the Grant Junction Railway; the Company being their own

carriers: 2. as on the London and Birmingham Railway; the Company

having nothing to do as carriers, but allowing the regular carriers

to use the railway on payment of a certain toll: 3. as on a few

minor railways in the north of England, where both the other systems

are combined, the Company and the carriers competing one with

another. The comparative advantages and disadvantages of these three

systems form an intricate subject, into which we do not propose to

enter; both in committee-rooms of the House of Commons and in courts

of law, questions of much difficulty have arisen in respect of one

or other of these systems. It happens, however, that on the railway

which forms the great artery between the metropolis and the

manufacturing districts, viz., the London and Birmingham, the system

of open competition is adopted; and the very nature of this

competition, coupled with the immense extent of the daily traffic to

the metropolis, render this railway a peculiarly advantageous one

for watching the communicating machinery which links the Manchester

or Birmingham manufacturer with the London warehouseman or

merchant.”

Penny Magazine, Volume 2,

edited by Charles Knight (1842).

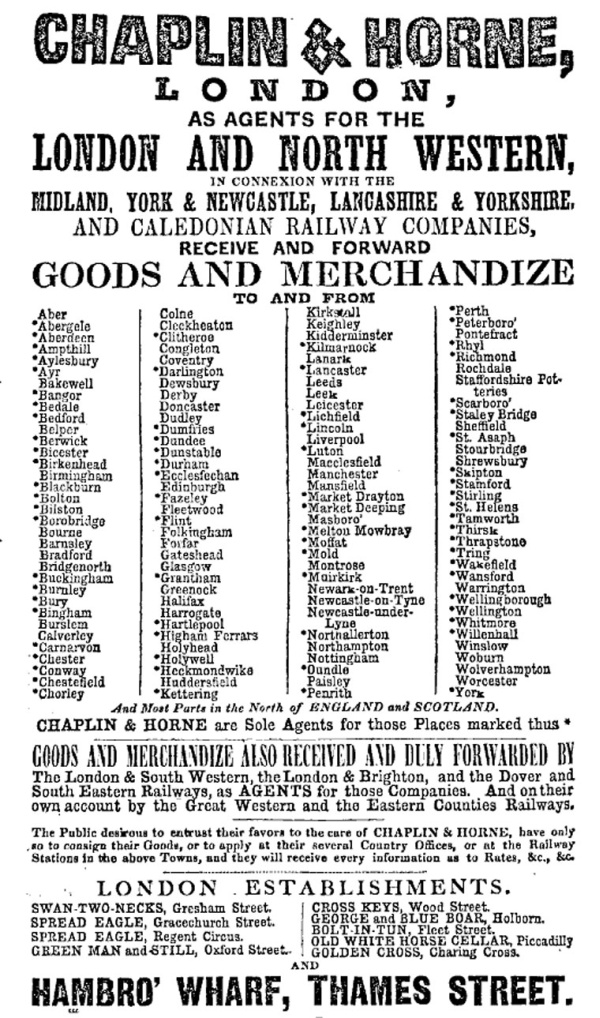

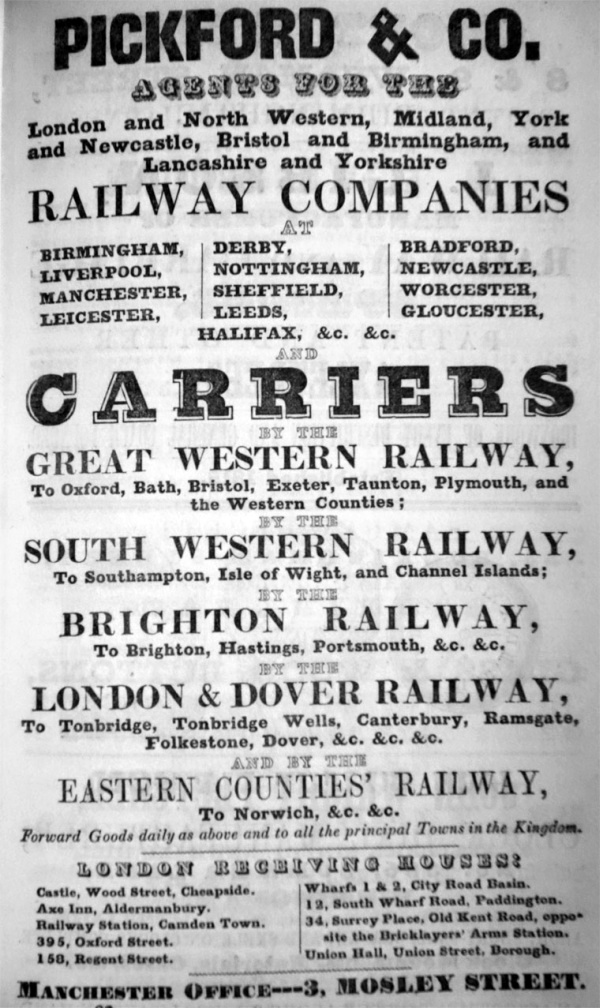

The practice adopted by the Grand Junction Railway, from Birmingham

northwards (referred to at 1. above), was to employ a large

carrying firm, Chaplin & Horne, as

their goods agent, on terms more favourable than those they applied

to Pickfords and to other carriers on the line. However, this

arrangement ignored the terms of the Grand Junction Railway’s Act, which

required that there be equal charging. The long-established firm

of Pickfords contested this practice in