|

CANAL MEMORIES

CONTENTS

(click to select)

A Collection of

Stories About the Canal at Tring

by Bob Grace

Memoirs of a British Waterways Canal engineer

by Edward Bell

Memoirs of a Canal Boat Builder at Tring

by Harry Fennimore

John Dickinson and the Canal

by Russell Horwood

Canal Reminiscences of Working for Dickinson’s in Apsley

by Joe

Bloor

Memoirs of a Boxmoor Man

by John Mew

Memoirs of a Boatwoman

by Gladys Horn

see also . . . .

A HIGHWAY

LAID

WITH

WATER

(a history of the Grand Union Canal)

――――♦――――

A Collection Of Stories

About The Canal At Tring

by Bob Grace

[Biographic notes, c.1977] Bob Grace has lived in Tring for most

of his life. He was born at Parsonage Farm, which formerly

stood on the site of Bishop Wood School. As a boy he attended

the old National School at Tring.

Mr. Grace now lives a busy life in retirement. He worked in

Tring all his life and eventually joined the family’s corn and

milling business which had been in existence for 250 years before it

ceased in about 1977.

During the war, he was sent to study electronics and then went out

to the jungles in the East to work on radar equipment.

For the last 30 years Mr Grace has been a Local Councillor and has

accumulated knowledge and tries to pass it on as accurately as

possible.

The Wendover Arm of The

Canal

Tring’s connection with the canal is via the

Wendover Arm, which is

only a navigable feeder. It was never built to take the very

deep canal boats. To publicise the canal when this stretch was

first opened, they took a prize animal to Smithfield Show via the

Wendover Arm. It was brought from Cresslow between Aylesbury

and Buckingham to Wendover and loaded onto a barge for its journey

to London. The story goes that it actually won the

championship at Smithfield and it was extensively advertised that

this was because it had been brought down by the new navigation,

thereby arriving in prime condition, instead of being driven there.

One less known fact about the canal is that, before the railway

came, boats used to carry passengers. From Wendover and

Aylesbury they actually ran an emigration boat. This took

people during the hungry 40s (19th century) to emigrate to Canada.

I think they went to Liverpool by canal.

The canal worked the other way too, bringing people into the area.

There was a large estate in Tring (now called Drayton Lodge), just

on the Aylesbury road. The Squire there came from the

Derbyshire/Nottinghamshire area and brought all his goods and some

of his men down by boat. Soldiers were conveyed by canal,

also, before the railway, accompanied by their horses.

When the canal was being constructed, the story goes that a number

of ancient remains were discovered; amongst these was reputed to be

a gold chain and some gold sword hilts. The landowner, Mr

Sear, is supposed to have demanded the relics and melted them down

before they could be removed to a national collection.

Smallpox in Tring

There is also an account of the treatment of a man for smallpox in

Tring. One of the canal labourers was taken ill with smallpox,

which even in those days could be considered as a notifiable

disease, and he became chargeable to the Tring parish, and therefore

his expenses were put as a separate item in the Parish accounts.

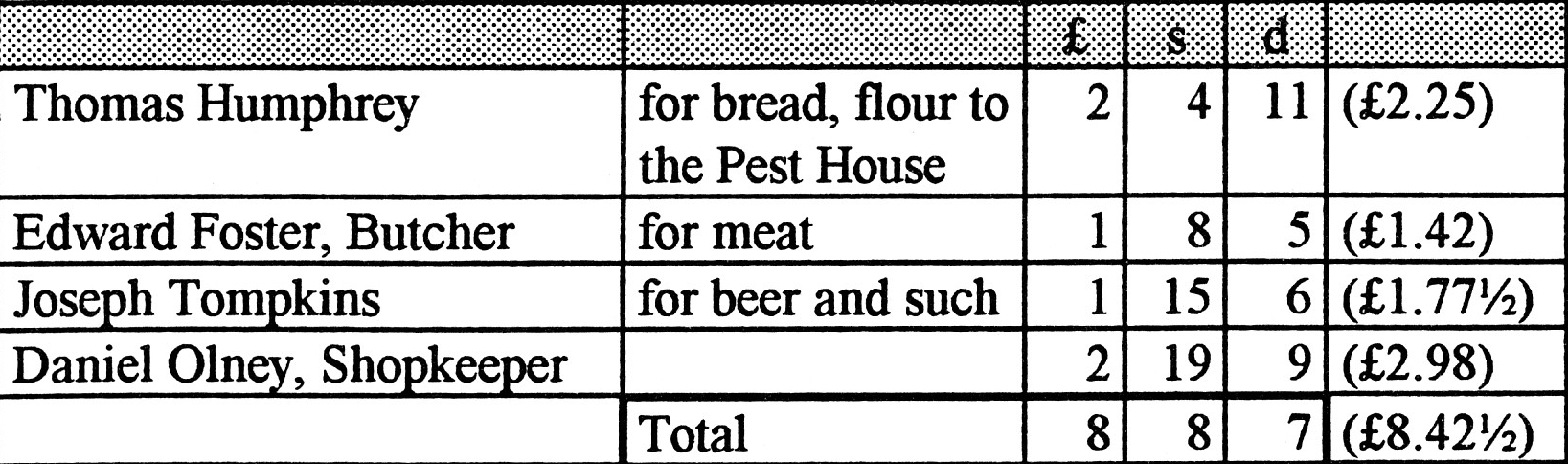

These are listed as ‘Payments by Mr. T. Humphrey to attending John

Turbot, a labourer on the canal with smallpox, viz:

There is no entry for the funeral

expenses for John Turbot - so presumably he recovered! Beer and

spirits seem to have been standard treatment for illnesses of a

serious nature in those days. All the accounts for people

removed to the Pest House, which incidentally stood at Wigginton,

just at the edge of the woods, show that they were filled up with

beer and spirits and if they survived - they survived.

Mill Water

When the Wendover navigable feeder was dug round the contours to

Wendover with the sole idea of tapping all the springs, it stopped

all the water supplies to the water mills. My ancestors were

millers at that time and they had large mills at New Mill and at

Tringford, just below the town, and their water supplies were cut.

They were bought out at the New Mill by the canal company before the

work started but I think at the Tringford mill, and certainly at the

Marsworth mill (which belonged to another family), there was

disaster when the water supply was cut. Immediately they went

to law to support their claim for water rights. The lawsuit

dragged on for some time. Also the millers of Aylesbury banded

together and went to law and the result was that the canal company

had to form the reservoir at Weston Turville (sometimes called

Halton Reservoir, sometimes World’s End Reservoir), which people

often think is to supply the canal, but actually it is below the

level of the canal and it was entirely to supply the water mills.

Water was let out to the various brooks to keep the mills turning.

In fact, even today farmers can go and ask for water to be let out

to water their cattle.

The Mead Family

The Marsworth Mill was a fairly large water mill. Water mills

got gradually larger as one proceeded downstream - the mill at the

head was always the smallest. Marsworth was a fair-sized mill

fed by the Bulbourne and entirely cut off by the reservoirs so the

canal company bought a steam mill; the very first steam mill in the

neighbourhood, worked by a beam engine and let out to a family named

Clark who were the millers. This ran until the 1890s when it

was bought by Messrs Meads of the Tring Wharf mills. It then

closed down and the work was concentrated at the Tring Wharf.

The Tring Wharf Mill was built by a Mr Grover who originated from

Aldbury. He first had a windmill, then a wharf, and later a

lime-kiln, all directly connected with the canal. Then the

Mead family, who were warfingers, arrived. Then they decided

to go into the milling business and went into partnership with the

Grovers and built the first steam mill at Tring Wharf and also began

as canal carriers (they owned barges), and eventually became barge

builders in quite a large way.

The Mead family’s first trade was in hay and straw which they took

to the London area; they brought back the ‘London dung’ which was

terrible stuff containing all manner of city waste. It made a

vast difference, however, to the farms bordering on the canal as it

was unloaded straight onto their fields (this was before there was

much artificial manure). The resulting increased yield of corn

in turn went back to the Mead’s mill to be ground for flour and the

flour and side-products went to various districts, again by canal.

The Meads at one time had their headquarters at Tring Wharf, New

Mill (now Messrs Heygates). In addition they owned mills at

Wendover, at the head of the canal feeder there, and down the canal

to Hemel Hempstead where they had Piccotts End Mill and Bury Mill.

Then they spread further to Hunton Bridge where they had a mill

which burnt down many years ago and on to the Watford Mill which

used to stand at the end of the High Street, just before Bushey

Arches, right on the High Street. Again, mills got larger

downstream, and the Watford Mill was quite a large one. Wendover

Mill was a windmill - the largest one known in this area - with at

least six pairs of stones, whereas three was the usual number.

The Meads also had a depot at Paddington where the canal basin is,

and there they traded in hay, straw, oats and flour and on return

journeys in timber etc., up the canal back to Tring or beyond. The

brothers spread out, and each one established these various depots

where they had their houses and their families. They had

interests at Iver, where there is a branch of the canal which used

to go off through to Uxbridge, and there they had a large

brickworks. In Tring you could walk round and decide which houses

were built with Meads’ bricks from Iver.

One of the famous, or infamous, things about the Meads, depending on

your point of view, is that they were one of the first millers to

work in conjunction with bakers and to tie bakers to the mill so

that they could not buy flour except through the mill.

Eventually they got to what is now known as Clarke bread, and they

took Chelsea Mill in London, and that was the first mill where the

roller process of flour milling was established (they brought it in

from France). Roller flour gradually ousted all stone-ground

flour which is now just fashionable for health food.

The Meads became very wealthy and influential. Some of them

went into farming (some are still doing this). The boat

building business gradually grew as well and was eventually handed

by the Meads to Messrs Bushell.

The Bushell Family

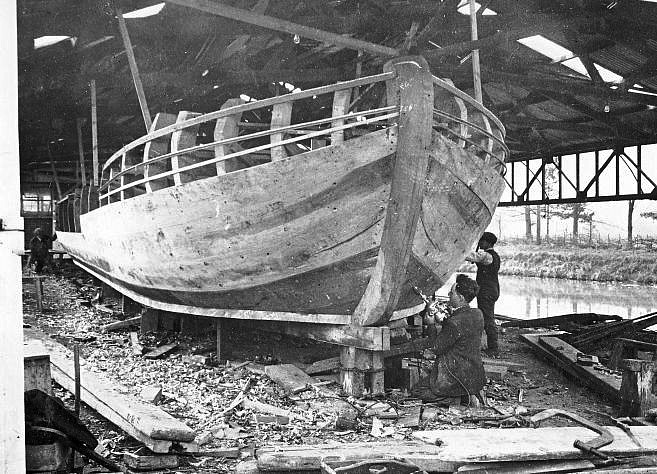

Above:

Progress under construction at Bushell Brother's boatyard, Tring, in

1934

Below: Progress being launched.

Photos courtesy of

Miss Catherine Bushell.

Joseph Bushell and his two sons Joseph and Charles, worked in

partnership until 1950 when they retired. One of the boats

they made was known as Progress. This was in about 1929

[Ed. 1934] when there was a short revival in the canal system. Government

money was put in and it was decided that instead of the ordinary

narrow boat they would have a slightly larger barge and alter the

canal system to take it right through from the Thames to the other

river systems. It was much larger than the ordinary narrow

boat and therefore had a much larger engine, and even boasted a

revolving wheel (like a ship’s wheel), instead of the barge tiller.

This boat was launched with some difficulty as boats were launched

broadside on at New Mill and this required considerable skill,

especially with this larger boat. They could not put the top

fittings on because it would not go under the bridges before they

got it to the Warwick/Birmingham branch where it was to start work.

After the fitting had been completed, a member of the Royal family

sailed it through the first locks. I am sorry to say that,

through no fault of the builders, the steering gear failed at the

first attempt because it was too sluggish to control a boat going

through the canal locks where they have to swing on the tiller to

make the boat move sideways. The engine was too powerful and

too fast for canal work, so it all had to be modernised and by the

time it was sailing the impetus had gone out of the whole affair and

the Government had decided that there was another recession and no

more money was available for the canals, but it was a great attempt.

The Meads at Tring Station

Returning to Tring itself - the Meads also had a wharf at Tring

Station where they specialised in hay and straw work and they also

maintained their Threshing Set, that is a steam engine and a

threshing drum and its associated chaff cutters and crushers and so

on which went round the farms and did work for contract, and of

course the straw and chaff were taken back to the canal.

The people we haven’t mentioned are the actual canal carriers.

The Meads were canal carriers and, of course, had their own boats

which they had built in the neighbourhood, but firms had grown up

who actually specialised in nothing but canal carrying and the chief

one was based at Aylesbury, and they had depots. I think they had

the one at Dudswell, you can still see the building just this side

of Northchurch, between the railway and the canal, there is a large

building that was a stable and a granary. This firm

specialised in express carrying, boats which travelled light - just

one boat with a gang of men aboard, travelling by day and night and

they could do extraordinarily fast journeys. Also, of course,

there was the day-to-day carrying. They had arrangements to

pick up even small amounts of things, as a parcel service would

to-day, to be delivered to Paddington Basin and from there by one of

the carriers to places in London. My grandfather and father

actually used to have small quantities of seeds (grass seed, turnip

seed and green kale seeds, etc.,) which were brought from specialist

warehouses in the eastern counties into London, probably by the Lee

navigation into London, round to the Paddington Basin by the

Regent’s Canal and then picked up by these boats, and they would be

dropped off at Bulbourne. A postcard (postage one ha’penny),

would arrive saying that our goods would be at Bulbourne at 9

o’clock the next morning, and they would be, there was no question

about that. In 1841, Thomas Langdon was the general carrier in

this district, and from my family he used to buy a large quantity of

beans to feed the barge horses. For example, in 1841 his

account to 30 December was £70 12s 0d. (£70.60), for beans and old

oats, which was a large sum of money in those days. The

carriage charges that he used to make were, for example, carriage of

17 quarters of beans to London 4 shillings (20 p) a quarter, which

is £3 8s 0d. (£3.40).

Mr Horwood and the Rothschild horses

Apart from the established carriers, who were taken over by bigger

firms and gradually amalgamated, there were individual carriers.

The story of one of these, Mr Horwood, is very interesting. He

was a farmer at Marsworth. This was in the days of the

Rothschilds at Mentmore. The Baron owned a great number of

famous race-horses, and the local farmers of course always followed

the Baron’s horses. In about 1871 it became what was known as

the “Baron’s Year” in the racing world, because his horses won all

the classic races. Mr. Horwood had the good sense to put an

accumulator bet on the Baron’s horses for the season and the result

was that he won enough money to build a row of cottages and to buy a

pair of boats to run on the canal. He called the boats the

Plobonius and the Hannah. The horse Plobonius

had won the Derby and Hannah had won the Oaks.

Mr Horwood ran these boats and a local family became bargees on

them. Being a bargee was not a good job, it was a killing job

and most of them died very young, many in tragic circumstances, from

illnesses such as consumption (tuberculosis), through being wet,

cold and miserable, working in all weathers and working extremely

hard to load and unload the boat, and then sometimes having to walk

with the horse all day and wind the locks. Also, the health

hazards were increased by the gypsy-like existence of travelling all

the time. Equally, the life was not particularly pleasant for

the canal staff who lived at the lock houses and isolated pumping

stations and who were as cut-off as anyone in the old days. To

give an example, there was a small pumping station at one time known

as The White House on the Wendover Arm pumping solely from a spring

leading into what is now the Wilstone Reservoir. The people

who lived there could only approach the White House by a winding

track through the fields from Wilstone or along the towpath.

The result was that when one of the household died they would not

allow the coffin to be brought across the field path because in

those days it was believed that if a coffin was carried along a

field path, that path became a public right of way.

Consequently there was a boating funeral. One of the flat boats

(I think they were called ‘flats’) from the works at Bulbourne was

covered with ivy and flowers and the coffin was carried on it.

The Bridgewater Connection

In the case of the people from the White House, they were buried at

Drayton Church, a short distance along the Wendover Arm of the

canal. Marsworth was the boat peoples’ church for this

neighbourhood because the top lock at Marsworth was the focal point

where the barges were weighed and measured when they came through

for their tolls and the Bulbourne Works was the headquarters of the

canal works’ staff‘, and therefore many retired and lived in the

Marsworth area and eventually were buried at Marsworth Church, and

this attracted the boating families. The boats could not go as

near to the church at Marsworth as they could at Drayton. The

coffin was unloaded below the bridge in Marsworth village and

carried up through the village and all the people in the village who

had canal connections used to follow on foot to the churchyard and

pay their last respects.

As you pass along the Tring summit of the canal, looking up towards

the Ivinghoe and Ashridge hills, you see the top of the Bridgewater

monument and people are apt to think that Bridgewater was the person

who built what was then the Grand Junction Canal. Actually he

died before the canal came through Tring, but the engineers who

started the canal were, of course, under his control and did have

connections with Ashridge. The then agent to the Bridgewaters

at Ashridge was a Mr Gilbert, whose brother was agent for the Earl

of Bridgewater at his estates near Newcastle-under-Lyne, where the

plans were made for the first Bridgewater canal leading out towards

Manchester to take the Earl’s coal from Worsley. One local

young man from Tring, through the friendship of Mr Gilbert, got a

job at Trentham on the estate of the Earl of Gower, who was a

relation by marriage to the Earl of Bridgewater and they worked in

conjunction, both putting up money for the canal project. The

young man from Tring worked for a time, helping with drawings and

measurements, under Mr Brindley who was the great self-taught canal

architect.

There was not a hotel at Tring Station in those days near the canal.

That was built on the coming of the railway by the Brown family,

under the aegis of the great Lord Lonsdale, (the ‘yellow duke’), who

built the Royal Hotel at Tring Station, as a hunting box. He

would come down by train from London and hunt for the day whenever

he wished.

Another great landowner who had the Pendley estate at that time was

Count de Harcourt and the Royal Hotel at Tring Station was at one

time called the Harcourt Arms, but he left because of the canal.

Before the canal came the Bulbourne streams which rose at the Tring

Summit (one running down the Gade Valley and joining up with the

Gade at Hemel Hempstead; the other running northwards and becoming

the head waters of the river Thames), provided excellent trout

fishing. When the canal was built the Count said it had

spoiled his fishing and he would leave his estate. This was

bought in later years by the Williams’ family, the well-known member

of this family being Mr Dorian Williams (died 1979), the famous show

jumping broadcaster.

Health Inspectors

Returning to the subject of the health of the boat people, this

became a matter of national concern and an Act of Parliament was

brought in that all canal boats must be inspected and checked for

their ‘canal worthiness’, and for the health of their crew.

This fell under the duties of an Urban District Council where the

boats were registered and in Tring in 1933 there were 76 boats on

the Tring Register, 11 of which were motorboats. In 1937 there

were 100 boats on the Tring Register, of which 17 were motorboats.

This caused quite a lot of trouble to the Surveyor of the Urban

District Council, who was also the Health Inspector, and Inspector

of Canal Boats, for which he received an extra salary which I

believe was something like one shilling per boat inspected. He

was always complaining that he was never able to inspect any of

these boats because he could only inspect them if they were actually

tied up in the Tring area for the day and if he had been notified of

that fact. This meant that when he had to give his return at

the end of the year for the number of boats inspected, it was always

much less than the authorities required and the result was that

threatening letters came from the Ministry of Health saying that

Tring had not done its duty in inspecting canal boats. The

boats became registered in Tring because they had been built or

repaired at Messrs Bushells’ yard. Along the top of the cabin

usually, in white lettering on black paint, could be seen the words

‘Registered at Tring No .....’ so that each boat could be easily

identified as to whom was responsible for inspection.

Water Rates and Rights

The canal and local councils were always at loggerheads about

drainage. Drainage from the roads going into the canal was a

nuisance at times, but sometimes they were glad of it.

However, it always caused friction. Also the coming of the

canal brought in the first industrial rates. An agricultural

parish, like Marsworth, suddenly brought in a windfall in rateable

value, which was paid over the years until the decline of the canals

with the coming of the railway. Various schemes were then made

to ease the rates on the canal and the adjoining wards. Tring

eventually went to law with the old Grand Junction Canal Company

over the question of water rate and water rights. The case

dragged on for some years and the only people who benefitted from it

were the legal authorities and eventually the two sides had to reach

an agreement to call it a day.

With the coming of the great reservoirs to Tring, they were not

constructed in their present form in the first instance. First

of all they were just ‘heads’ - the Ashwell Head at Wilstone and the

Bulbourne Head at Marsworth, which were dammed up and small pumping

engines put in to pump direct into the Wendover navigable feeder,

one pump being halfway between the main arm and New Mill and the

other pump being at the White House, above Wilstone reservoir.

These were the first engines of the neighbourhood and the men who

came to work them were, of course, engineers, the first to come into

this part of the world.

The engines were vacuum engines, which meant that they worked on

very little steam pressure (about 5 psi, I think), from very simple

boilers. The engine was activated by the weight of the pump

bucket drawing up the piston and the piston cylinder being filled

with steam from this boiler, then a jet of water was squirted in

condensing the steam. The vacuum then formed drew up the

bucket and brought up the water to the canal level. These two

engines were extremely inefficient, even by the standards of those

days, and they were soon replaced by engines put in at the Tringford

station. These were two great beam engines.

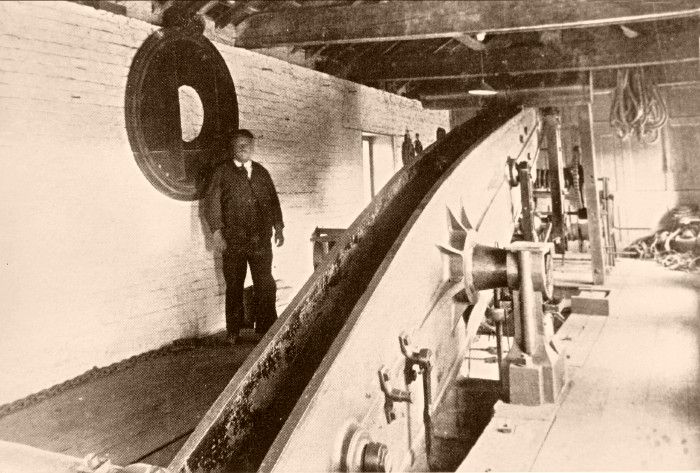

Beam engine at

Tringford pumping station.

Mr. Jonathan Woodhouse

The engineers who came to work the machines brought their associated

tradesmen with them; blacksmiths, iron-founders, bricklayers,

well-sinkers and so on. They mostly came from the Midlands to

Tring and made their homes here. One of the families was named

Woodhouse and Mr Jonathan Woodhouse was the first engineer to

establish the great engines in the Tringford Pumping Station.

One of these pumped from a depth of about 80 feet (24 metres) from

the Wilstone Reservoir and the other one something like 40 to 50

feet from the Little Tring and what we call Startops Reservoir.

When I was a boy I used to go and watch the last great beam engine

working - it ran at 13 strokes a minute and lifted a ton of water at

each stroke - and it was very thrilling to stand at the water outlet

and see it come up in a great gush (there was no continuous flow as

there is with modem pumps). Sometimes fish would come up with the

water - this was not a rotary pump it was merely a pump with what

was known as ‘clacks’ in it, i.e., little trapdoors that

opened when the bucket went down and shut when it began to lift, so

quite a large fish could be caught in the bucket, and we were always

watching as boys to see if we could catch one. Some very brave

boys who got inside actually rode up and down on the great beam but

I never had pluck enough for that. The old engine was offered

to the Science Museum when it came to the end of its life (it was

still working perfectly), but the Museum had not got enough room for

it.

No doubt there are some descendants of the Woodhouse family still in

the area, but I don’t know anyone of that name now in the town.

Not only did they work for the canal company, but gradually some of

them left the canal company and became engineers in their own right

in the district, fitting the very first engines in flour mills and

then in sawmills and other local industries. It is interesting

to remember that before the canal came there wasn’t an engine known

anywhere, and, of course, the canal also brought the coal to drive

these engines (which they consumed in vast amounts). The coal

came from the Nuneaton area and the boats did it as a regular run,

they didn’t bother to load back, they went back empty as fast as

they could to fetch another load. The men would stand in the

hold and throw the coal up into wheelbarrows and the women would

stand on the planks and wheel the barrows into the yard - tons of

coal in each load.

The Mew Family

The Mew family have worked on the canal for many, many, years (all

very skilled tradesmen), and in their spare time they used to make

little model engines similar to the ones they were working.

When there was a dry time on the canal, the water had to be pumped

back to the Tring Summit and they had a set of engines known as the

Northern Engines, and this was so engineered that the water could be

pumped back from as far as Leighton Buzzard to the Tring Summit by

this relay of engines all pumping away so that the same lock of

water was never wasted. You might wonder how the water got to

Tringford pumping station from the reservoirs. This itself was

a great engineering feat because they drove culverts through from

Wilstone reservoir under the hill which surrounds it to Tringford

through the chalk by tunnelling - the men working on their hands and

knees to clear the very hard chalk at that depth. There was no

brick lining or anything like that, they just dug the chalk tunnel

through to Tringford. At the present day (1979), the tunnel

from Startops End reservoir has collapsed underneath the Tringford

reservoir and they are spending thousands of pounds trying to repair

it, but the old original tunnel from Wilstone is still there, and it

must be something like well over 100 feet (30 metres) deep at its

deepest point and it was all done by men on their hands and knees.

Years ago at Bulbourne works you could still see the special

corduroy trousers that were issued to these men. They were

extremely heavy and thick so that they could work on their knees,

and they were so stiff that an ordinary person could not manage to

get into them.

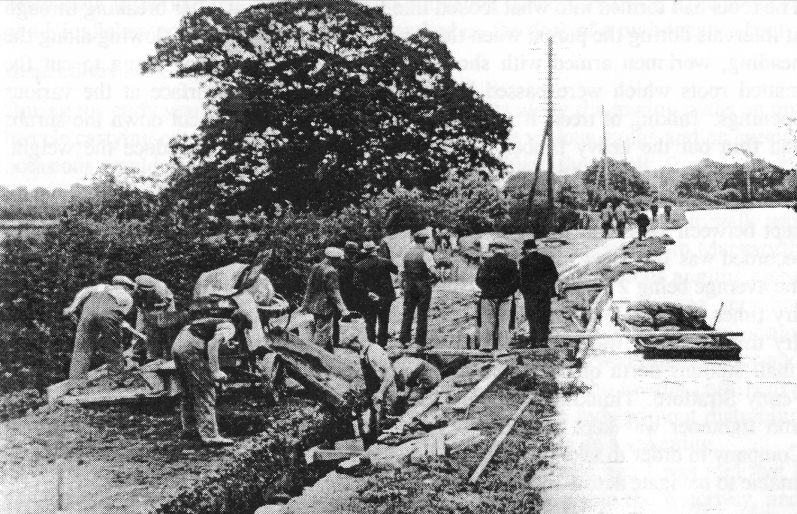

Bulbourne Works in

its heyday.

Lock gates were made at the Bulbourne Works. These days they

have much machinery but in the beginning the whole work was done by

pitsaw which was terribly hard work. Trees were cut down and

sawn up to make the lock gates and the sills for the gates and so

on, which were all extremely heavy pieces of timber.

――――♦――――

Memoirs of a British

Waterways

Canal Engineer

by Edward Bell

I was born in Canal Street, Hopwood, Heywood, Lancashire, during

March 1902. As a small boy I often went to a nearby bridge

over a branch of the Rochdale Canal which served the cotton-spinning

town of Heywood and saw the smoke spiralling upwards from 21 factory

chimneys. I little thought that I would ever become a canal

man as I always wanted to be a motor engineer.

My mother came from Tring and so after the death of my father’s

parents we came south to live here in November 1913.

Previously I had been several times to Tring on holidays spent with

members of my mother’s family, all of whom were employed by the

Rothschild Estate and I can well remember walking down to Startops

End Reservoir where I was privileged to see King Edward VII and his

friend Lord Rothschild enjoying an afternoon of duck shooting.

Outbreak of War

In the spring of 1914 my twin brother and I joined the First Tring

Troop of Boy Scouts and we were camping near the Bridgewater

Memorial at Ashridge when the First World War broke out. As my

brother and I were due to go to Berkhamsted School in September, and

had a longer holiday than other members of the troop, we were chosen

for duty at the Pitstone Rifle Range near Folly Farm (where soldiers

did final rifle training before going over to France) to carry any

messages to and fro from the nearest telephone situated at that time

in the ofiice of W. N. Meads Flour Mill, New Mill, Tring.

During my scouting days I came to know and love the Chiltern Hills

and I collected knowledge of the roads, footpaths, the arable or

pasture land, numbers of cattle, sheep, pigs, etc., on the many

farms in this area, with the object of obtaining my King’s Scout

badge, but unfortunately by the time I had obtained all the

necessary data an examiner could not be found, so many men having

gone to the war.

When I left Berkhamsted School in the summer of 1916, it was

intended that I should start my working life at the Fiat Motor Car

Works, Wembley, as my father knew the Manager, but he advised that I

should try to get general experience in a small garage as the Fiat

Works was turned over to munitions and I would be stuck at a lathe

turning out shell cases for the duration of the war. I

therefore became an apprentice in a small garage paying a £15

premium for three years’ training at a weekly wage of one shilling,

increased at the end of the first year to 1s 6d. During 1917

petrol was no longer available for private motoring and I was

reduced to mending bicycle punctures and unable to gain the training

I desired.

Chilly Start to Canal World

It seemed fated that I was to be a canal man when I secured a

position as assistant to the overseer of the then Middle District

(from Lock 22 Fenny Stratford to Lock 46 Cowroast) of the Grand

Junction Canal at the princely sum of 15s per week on Monday, 8

January 1918. The canal was frozen over and so on my second

day I was asked if I would like to join the iceboat crew who were to

break the 6½ miles of canal from my office at Marsworth to the canal

basin at Walton Street, Aylesbury, and I was quickly introduced to

the exciting work of ice-breaking. During my early years with

the Grand Junction Company I went out on many occasions with the ice

breaking crews and once we had as many as 15 horses stretched out

along the towing-path to provide the motive power, with 24 men on

board the iceboat to rock the craft from side to side breaking the

way through pack-ice up to 9 inches (23 cm) thick. In those

days there was no unemployment benefit for the boat people who were

always eager to follow the iceboat and would oflen assist with their

own horses when we were in difficulty. I soon learned to love

the outdoor life on the waterway and was very thrilled when I became

sufficiently skilled to steer one of the 70 feet (21.5 metres) long

maintenance narrow boats up the flight of seven locks between

Marsworth and Bulbourne, as the short pounds between these locks

were very difficult to navigate.

Floods and erosion

The first major catastrophe I remember occurred in November 1918,

when the large brick culvert under the canal at Chelmscote, three

locks north of Leighton Buzzard burst, flooding the surrounding

farmland until the escaping canal water could reach the nearby river

Ouzel. Gangs worked in shifts by day and night, and commercial

boats were moving again along a restricted width of waterway after

being held up for three days. Owing to the shortage of labour

towards the end of the war soldiers from a labour battalion were

used for this work to augment the canal staff.

One of my first tasks was to assist in taking cross-sections of the

canal to try to assess the amount of bank erosion which had taken

place since the canal was constructed and in later years I was able

to repeat this and obtain a comparison between the speed of erosion

in the days of horse-drawn craft and the more rapid deterioration of

banks and towing-path dry-stone walling when self-propelled craft

had been operating for a number of years.

Tring Summit

One of the major difficulties confronting the engineers responsible

for constructing the Grand Junction Canal over the 100 miles between

Braunston near Rugby and the River Thames at Brentford was the task

of taking the waterway over the Chiltern Hills at a point just to

the east of Tring. This they decided to do in an open cutting

along the length between Lock 45 Bulbourne and Lock 46 Cowroast,

which we now call the Tring Summit level. It is 391 feet (119

metres) above sea level when there is a depth of 5 feet (1.5 metres)

of water on the lock head sills at either end.

A pair of A.

Harvey-Taylor narrowboats in the steep-sided Tring Cutting.

My first memories of Tring Summit were of the deep concrete walling

being constructed along the towing path side on the bend just south

of Bridge 135 near Tring Station. Sections of towpath were

side stacked with hand driven timber piling and the resulting

enclosure pumped dry so that excavation could be carried out for the

concrete-filled trench to form the foundation for the massive

concrete wall. This was extremely hard manual work and was

later to be superseded by reinforced concrete sheet piling driven by

a 7 cwt (355 kg) cast iron monkey hoisted up and down the

pile-driving frame by means of a mechanical winch. During

these later piling works considerable difficulty was experienced in

Tring Summit because halved tree trunks had been laid in the bed of

the canal across the waterway at intervals with timber piles at each

end of the tree to prevent the toe of the high offside bank from

encroaching into the waterway.

Vital Water Supplies and Management

Originally this Tring Summit level was continuous through from

Cowroast Lock 46 to Lock 45. The vital necessity was a

sufficient water supply to maintain such a long level. This

came from surface springs feeding into the millstream at Wendover,

also from underground spring water tapped by an artesian well and

conveyed to the canal at Wendover Wharf where the millstream supply

also entered the waterway. Unfortunately considerable trouble

was experienced owing to leakage of water from the Wendover Arm of

the canal and around 1904 to solve the problem the Arm was closed.

The canal bed between Drayton Beauchamp and Little Tring was

excavated, in about 1914, to take a line of 18 inches (48 cm)

diameter earthenware pipes to conduct the Wendover water supply into

Tringford Reservoir. Only the length between the Main Line and

Tringford Pumping Station remained navigable and the canal bed from

Drayton Beauchamp to Wendover became a water course, which needed to

be kept free from weed growth to allow the maximum supply to reach

the Tring Reservoirs.

The supply of water from the Chiltern Hills at Wendover and other

sources was so vital to maintaining the Tring Summit Level that

gauges were provided at all points where a supply entered the canal

or any of the reservoirs. A record of weekly readings was kept

in order to calculate the total amount of inflow as against the

quantity used by boats passing over the Summit Level. Each

pair of boats passing over the Summit would require at least two

locks of water and a standard lock was estimated to hold 56,000

gallons (254,600 litres).

I enjoyed cycling around the Tring area on occasions with the

Waterman and for many years I kept these records, becoming fully

acquainted with the very complicated water supply system. With

the exception of the Tring feeder which receives its water supply

from the Miswell Ponds via Dundale Spinney to the Silkmill Pond in

Brook Street and then flows direct into the Tring Summit just west

of Gamnel Bridge, all water other than actual rainfall into the

canal and the drainage from the high banks of both the canal and

railway cuttings, had to be lifted into the Summit Level by the

various pumps at Tringford Pumping Station. When I joined the

Canal Company the old beam engine was still operating at Well No. 3,

but diesel plant had been installed in 1911 to generate electricity

for pumps in Wells Nos. 1 and 2. The old beam engine dated

1803 was replaced by vertical spindle pumps in 1927, and these were

driven by electricity supplied direct from the mains. Quite

recently the 100 hp and 50 hp diesel engines have been removed and

now the whole pumping station is electrically operated from a

comprehensive switchboard with mains supply. Also in 1945

automatic float control pumps were installed in a small separate

pumphouse alongside the Wendover Arm pipe discharge chamber, to lift

the supply continuously to the Summit Level - the small or large

pump operating in relation to the quantity of water flowing through

the pipeline. In the event of power cuts or any emergency the

water could still be diverted into the reservoir.

From Grand Junction to Grand Union produced improvements

During 1929 an amalgamation of several canals took place to form the

Grand Union Canal System and a big development scheme was started so

that during the next few years much concrete walling was constructed

and many long lengths of sheet concrete piling driven, for which in

this area I was largely responsible.

Hand-excavating

trenches to repair walling to prevent leakage.

In earlier years, efforts to prevent leakage from the waterway had

usually been by hand-excavating of trenches in the towing path until

the inflow of water could be found and then sealing up the trench

with puddled clay, tramped down by the workmen treading the clay in

their very heavy leather thigh boots. It was often very

difficult to determine where the leakage took place as the inflow

was frequently a long way from where the outlet showed on adjoining

land. I mentioned that some water was supplied to Tring Summit

by drainage of the adjoining railway cutting from along the track

into a large brick culvert entering the canal on the towpath side

just south of Bridge 134 called Marshcroft and I was privileged to

walk through this heading during the drought of 1934, at a time when

we were desperately short of water and our Tring reservoirs were

almost completely empty. The reservoir beds looked like crazy

paving from the pattern of the cracks in the dried mud. In

order not to have to retrace our steps through the long heading

between the railway and canal the waterman and I climbed the high

railway bank and I remember feeling very scared as an express train

thundered along the track below us.

This is a good point at which to record that the reservoirs are

connected to the wells in Tringford Pumping Station by underground

chalk headings along which the water flows to give the same level in

the Pumping Station Well as that of the particular reservoir being

pumped from at the time. When the rains came to refill the

reservoirs after the drought in 1934 a portion of the length under

the Tringford reservoir collapsed and we had to construct a coffer

dam around the affected part to carry out repairs. This gave

me the only opportunity I ever had during my 49 years of service of

inspecting a section of this heading, the route of which ran from

the deepest part of Startops End reservoir, then under Tringford

reservoir to the Pumping Station, and I am therefore able to vouch

for the fact that the heading is cut out of the chalk with no

brickwork lining to give support, and by keeping my head well down I

could walk along at shoulder height.

In addition to the large brick culvert from the railway cutting

south of Bridge 134, there is another drainage supply from the

railway at Pitstone Green Bridge near the Tunnel Cement Works.

A smaller brick culvert goes under the fields surrounding Whiting

Hill finally to discharge into the canal on the offside above Lock

40 in the Marsworth Flight of Seven Locks. This culvert became

very silted up and in the late 1920s we had to trace the line of the

culvert and break down into it at intervals in order to extract the

accumulation of silt by means of a metal tube scoop pulled along the

culvert by wire rope connected to a hand-operated winch.

At about this time the artesian well-heading at Wendover was

becoming seriously choked with tree roots which had pierced the

brickwork in search of water. The roots had formed into what

looked like fibre-matting and after breaking through at intervals

during the period when there was a minimum of water flowing along the

heading, workmen armed with shortened scythe blades crawled along to

cut the matted roots which were passed back to be hauled to the

surface at the various openings. Talking of trees, it was

found necessary at times to cut down the shrubs and thin out the

heavy timber on the high Summit banks to reduce the weight, because

after a winter of severe frost slips might otherwise occur.

Rainfall was gauged at each end of the Tring Summit and from the

records kept between 1866 and my retirement in 1967 the minimum

rainfall to have been recorded was 16 inches (40 cm) in one year and

the maximum 42 inches (106 cm); the average being 27 inches (68.5

cm) per annum, and I can recollect exceptionally dry times in 1921,

1934, the middle 40s and 1959. During the first three of these

dry times lockage water was used over and over again, by pumping at

a series of small stations north of the Tring reservoirs from Lock

33 Marsworth to Lock 22 Fenny Stratford. Thinking of these

exceptionally dry periods reminds me that an iron lightener was kept

at Lock 45 Tring Summit when I first joined the Canal Company in

order to take off some of the load from boats which otherwise would

be unable to navigate across the Summit when the water level was

low.

Red Tape

During the first few years of my service the Summit was kept open

day and night, but later it became too expensive to retain the

number of lock-keepers and toll office staff for round-the-clock

duty. Just before 1918 the workmen had changed from 60 hours

to 48 hours per week and one of the men who lived at Marsworth told

me that if they were working at the Aylesbury end of the branch

canal he would have to get up early enough to walk along the towing

path to be on the job at 6 am, and then walk home again after 6

p.m., for 18s per week. An additional war bonus was, however,

being paid and so I had to write out the weekly sheets using black

ink for the usual wage and red ink in a separate column for the war

bonus. There was no telephone in the office nor a typewriter

and I remember seeing an old-fashioned letterpress among the office

equipment.

Game for Sport

The Rothschild Estate held the sporting rights to the reservoirs and

ducks were still bred to provide the targets for occasional shoots

at the appropriate season of the year. The ducks were reared

on Marsworth reservoir and the small reservoir at Wilstone.

Later when the reservoirs became a Nature Reserve and a permanent

warden was in charge, I was interested to learn from him that at

differing water levels certain types of birds would come to the

reservoirs and he often asked if we could keep the reservoir at a

special level to encourage a rare type of bird. For example,

when the reservoirs were full, diver birds came and at low levels

those birds which revelled in the muddy reservoir bed would be more

in evidence. Our waterways emblem was the Kingfisher and I

often saw one flying around the Marsworth depot and one day as I

looked out of my office window, I got a glimpse of a Kingfisher with

a fish in its mouth, perched on the deck of a maintenance boat.

Inspections were a pleasure

During my early years on the canal I rode many miles along the

towing paths on my bicycle carrying out inspections or taking orders

to the various gangs and on special occasions would take the train

from Tring to Bletchley, then walk from Lock 22 Fenny Stratford to

Leighton Buzzard or even back to Marsworth, the latter being a

distance of some 16 miles (26 km). Another very interesting

inspection walk was along the Wendover Arm, then by train to

Aylesbury and a walk back to Marsworth along the Aylesbury Arm.

Certain lengths of canal were let to various angling clubs and I

well remember as I was cycling along the Aylesbury Arm one very hot

summer day seeing two fishing rods lying across the towing path but

no sign of any fishermen. As I got closer to the rods I

noticed that both floats were under water and then I discovered the

fishermen fast asleep in the shade of the towing path hedge quite

unaware of their success. I stepped carefully over the rods

without disturbing their owners and I often wonder what they said to

each other on awakening.

When I joined the Grand Junction Canal Company years ago I was told

that I would not be considered a real canal man until I had fallen

into the waterway, and this I successfully accomplished during April

1922 by taking a header over the handlebars of a borrowed bicycle

into Marsworth near my office, and I am glad to record that it was

the only time I suffered such a fate. I may add that I

remember the postman doing something similar at Lock 45 Marsworth

and seeing the many letters from his saturated postbag being

carefully dried in the Toll Office at that lock.

Routine Changes and Promotion in World War 2

Soon after World War 2 broke out it was considered advisable, in

case of possible invasion, to patrol the Marsworth Seven Locks at

night and so when my turn came I would cycle from my home in Tring

to our Bulbourne Workshop during the late evening to get what sleep

I could on a mattress in the sitting-room of the storekeeper’s

house. He would wake me if necessary in time to start our

spell of duty at 2 am until 4 am and we would walk together to Lock

39 Startops End and rest there a while on the form outside the White

Lion before returning to Bulbourne. One early morning I

thoughtlessly leaned my rifle against the wall of the pub, and when

it fell to the ground I was amazed how quickly the landlord opened

the window of the bedroom to find out what made the noise.

Fortunately, we were hidden by the small penthouse roofing over the

taproom window so were not discovered. On many nights we were

horrified by being able to see from Bulbourne Canal Bridge the glow

in the sky from the bombing on London, but the only scare we

ourselves had was the dark shape of an enemy bomber as it passed in

front of the moon after a raid in the Midlands. A very large

bomb fell on the offside bank in Tring Summit just north of Bridge

135 making a deep hole about 70 feet (21 metres) in diameter and

deposited three large trees roots downwards into the canal.

Fortunately a steam dredger was working not far away and with

assistance from the Royal Engineers the waterway was soon cleared so

that traffic could proceed normally.

This bomb damage reminds me that I was too young to be called-up

during the First World War of 1914-18. As part of the vital

transport organisation of the country we were a reserved occupation

during the 1939-45 War. For purposes of economy, staff changes

took place and for a number of years I dealt with office

administration for which my outside experience stood me in good

stead.

When we were nationalised at the beginning of 1948, it became

apparent that there was a real need for standardisation in all

phases of canal maintenance. Methods of reporting progress of

work, fluctuations of water supply, damage to canal property, etc.,

as sent in by the many different canal companies comprising the

nationalised waterways varied so much that it was decided to set up

a training centre at our Bulbourne Office to ensure a standard

procedure for the whole country. I was thus able to be a

useful member of the training staff and found the work of tremendous

interest, especially meeting canal personnel from all over England,

Scotland and Wales: four of whom at a time came to spend a month at

our training centre. Wisely it was considered that outdoor

workers of this type would resent being cooped up in an ofiice every

day and I was therefore privileged to drive them around to inspect

any important work being carried out during their stay at Bulbourne.

This naturally increased my own knowledge and value to the

organisation, and promotion quickly followed. I became an Assistant

District Inspector and very soon afterwards was given charge of the

Watford District as it was then called (a sixty-mile length of main

line waterway from Lock 21 Cosgrove to Lock 101 Brentford, including

the branch canals, Northampton, Buckingham Arm (no longer

navigable), the Aylesbury and Wendover Arms at Tring and the Slough

and Paddington Arms (in the London Area).

When the waterways were nationalised the canal system was based on

the four great rivers - the Mersey in the north-west, Humber in the

north-east, Severn in the south-west and the Thames in the

south-east. The country was divided into four divisions

operated respectively from Liverpool, Leeds, Gloucester and London.

Each division was sub-divided into districts, hence my title of

District Inspector, and my particular area was split up into

sections so that I had five Section Inspectors to assist me.

During my outings with the men who attended the Training Centre I

was asked to take colour pictures of the various works we inspected,

and about which students wrote their individual reports to the

approved standardised pattern, so that Headquarters would be better

able to understand what they tried to convey on paper. The

colour pictures proved very useful indeed at the Training Centre,

and as it was so much easier to distinguish the different materials

being used, such as iron, wood, concrete, etc., by their respective

colour, had a great advantage over the previously used black and

white slides. I little thought that my photographic efforts

during the last ten years of my canal service would result in my

further promotion to becoming an Inspector of the London area and

the supervisor of some 160 miles of waterway, including the various

branches.

Toll Offices and Gauges

Toll Offices were situated at strategic points to gauge the loaded

craft and this was done with a calibrated rod floating inside a

copper tube which had a side-bracket enabling the gauging tube to be

held on the gunwale of the boat at four different points to obtain

an average of the number of dry inches of the craft above water

level. Each commercial craft was weighed and registered before

coming into service and a record sheet kept at the Toll Office

giving the dry inches for every 5 cwt (254 kg) of cargo on a

particular craft. A normal load for a pair of narrow boats

being 27½ tons on the motor boat and 30 tons on the butty boat.

I often assisted the Toll clerk by gauging loaded boats, coming

south from the Midland collieries or the Leighton Buzzard sand-pits,

which travelled down the Arm to unload at Aylesbury, and for this

purpose a spare gauging rod was kept in my office at Marsworth.

It is no longer necessary to gauge boats in this way as cargoes are

accurately measured when loading and the tonnage calculated accepted

by the receiver at the unloading point.

Ladies to the Rescue

During World War II many young society ladies helped by forming

crews to run commercial craft from London to the Midlands and back

again on weekdays. They would often come into my office on a

Friday afternoon after mooring their craft safely at Bulbourne for

the weekend and telephone friends to make appointments for two days’

relaxation before continuing their very arduous spell of war work,

especially during the winter months. I know from experience

what it means to handle wet ropes in icy cold weather using the

strapping stumps to check boats which are entering the lock at too

fast a speed. One of these young ladies wrote a very

interesting book about her experiences and I remember seeing

another, whose loaded craft sank as it drew alongside Bulbourne

works because the cargo had slipped, diving down into the flooded

cabin to rescue as many of her belongings as possible before they

were seriously damaged by canal water.

Working boats to pleasure boats

Reverting to my early years with the canal company I am reminded of

the time when Messrs Bushell Bros had their boat building yard

alongside the Wendover Arm of the canal near Gamnel Bridge and how

fascinating it was to watch the construction of a wooden narrow boat

from the forming of the timber framework to its covering with long

lengths of thick oak planking bent to shape, by steaming, for the

bow and stern of the craft, and finally to see the skilled craftsman

painting from memory the colourful and attractive roses’ and

castles’ design on the insides of the cabin doors etc. I

couldn’t help feeling sorry when steel-hulled boats of deeper

draught superseded these wonderful examples of the boat-builders’

art. Nowadays as I pay occasional visits to the waterway at

Bulbourne in my capacity as the Chairman of the Tring Branch of the

British Waterways Old Comrades Association to make arrangements for

our quarterly meetings or the annual coach outing, I am astonished

at the variety of pleasure craft which come over the Tring Summit

Level, and regret that the commercial narrow boats I knew so well

are rarely to be seen. It is possible that I do not recognise

some boats which have been converted into pleasure craft by the

addition of cabin space along the whole length of the boat, and

which now ply up and down the waterway as holiday cruisers.

Others have been cut in half and turned into four-berth cabin

cruisers ideally suited to survive the turbulence of water as locks

are being rapidly filled.

Where does the water go?

Thinking again of the vital water supply provided by the Chiltern

Hills, one may wonder what happens to it after it has served its

purpose for canal traffic. South of Tring Summit and via the

Aylesbury Arm the water finds its way by overflow weirs and streams

down to the River Thames and the same applies just north of the

Marsworth Seven Locks. From Lock 34 Seabrook to the 11

mile-long Fenny Pound until one reaches the next high level, surplus

water finds its way by the rivers Ouzel, Great Ouse, Nene, etc., to

discharge into the sea at the Wash on the east coast.

Changes in Gates

I am probably one of the few canal supervisors who has witnessed the

replacement of lock gates, because normally the life of these gates

is forty years or more. At Leighton Buzzard I was privileged

to see a semi-solid pair of gates replaced by the more modem type of

framed gate and I learnt that the canal was constructed originally

with gates which were completely solid. As a maintenance

inspector I was not directly concerned with the making of lock-gates

but with their installation when necessary. However, during my

early years of service seeing carpenters at Bulbourne Workshop using

the various hand tools to form the mortise and tenon joints in the

oak timber, but now this work is done by electrical machinery.

Looking back

During my long service on the waterway so many interesting

experiences came my way, some of them both worrying and alarming,

such as further burst culverts, occasional sunken boats holding up

other canal traffic, but I could not have wished for a more

interesting and varied occupation during which so many changes took

place in the waterway transport system.

――――♦――――

Memoirs of a Tring Canal Boat Builder

by Harry Fennimore

When I was about 15 years old I worked in an office which I hated

it, so I left. Then I had no job at all. One day I was

walking down the towpath kicking at the stones, when one of these

flew up and hit a man on the shin! This man turned out to be

old Mr. Bushell - he was very cross with me and started to tell me

off. He asked me where I worked and when I told him that I had

no job, he suggested that I should go and work for him, so that is

how I became involved in canals and boat building.

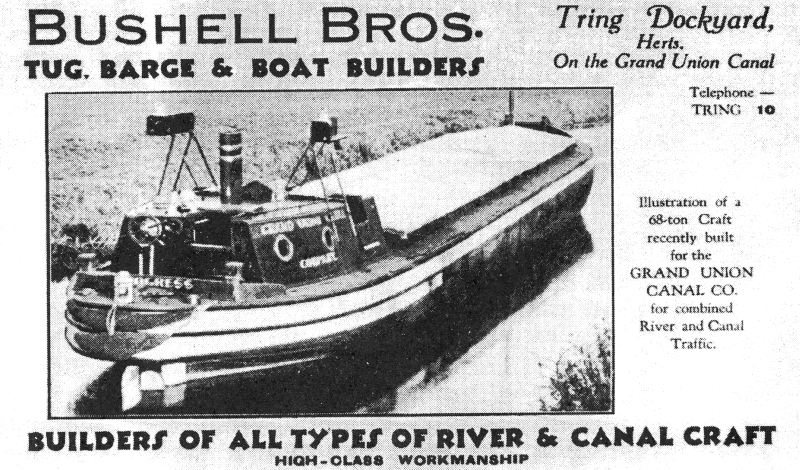

Advertisement for

Bushells Boat Builders showing 'Progress' on the canal.

I worked for Charlie and Joe Bushell, the brothers, whom we called

by their first names, but the old man we had to call the Boss

because he liked that. He had been the boss, and so we had to

fuss round him a bit and keep him happy. On the whole they

were pretty good to us. There was no such thing as strikes or

trouble of that sort, we just did our work which we were paid to do,

and didn’t expect anything else. But they were good to us in

many ways - they gave us blocks of wood for the fire and things like

that.

All In a Day’s Work

A typical day at Bushell’s Boatyard would start at 6 am, and in the

winter it was very dark then. We would go home to breakfast at

8 am, to a blazing fire, bacon and eggs, etc., and then we were

reluctant to go back to work again, as we had to work in the snow

and the ice with no protection whatever. We liked to get into

the blacksmith’s shop, it was hard work but we were warm in there

because of the blacksmith’s fire. Mostly though we were out in

the open and it might be snowing or hailing and all we could do was

work very hard to keep warm! Essentially building boats was an

outdoor job, and the comfort of the workers was not a consideration

in those days.

When the building of a boat was started it was built on a platform

(the stocks), and we would have to move these big elm bottoms about,

3 inches (7.6 cm) thick and over 7 feet (2 metres) long. They

were laid so that the ends hung over longer than necessary and they

were cut to shape afterwards. Carrying this wood around kept

us warm, but it still was not very nice with rain and snow dripping

down one’s neck, and it was impossible to do the work in gloves.

Dinner time was 12 until 1.00 pm. Although we had so much

timber to move about, there was very little machinery to help us.

We did have a bob-truck which was just two big cartwheels and an

axle and a long beam of wood with a chain on the end of it. We

hooked the chain around a piece of timber, pulled down on the long

shaft to lift it clear of the ground, and then ran with it!

The darker side of being a boat builder

The worst time was in the winter when it got dark at about 4 pm

(there was no British Summer Time then). Then we used to have

some nasty jobs to do - we had to straighten bent nails for use

again (they were very expensive then). The problem was that we

had to work two hours in darkness. One thing we did was to

make pointed pegs to fill the holes left in the boats where the

plates had been removed. We did this work inside by

candlelight and by the light of flare-lamps. These were made of

a round container, with a point running down from it and a burner on

the end. We used to heat the end of the burner in the

blacksmith’s forge and then turn the oil on and it used to flare up

because it was coming down to a hot burner. We used to stick

candles between three nails driven through a piece of wood about the

size of a book.

Another job we had to do on these dark evenings was to clean out the

gas engine which drove the circular saw and the bandsaw. We

just used to creep about with the candles doing all the boring jobs

and it was very miserable. Sometimes we would go and do work

in the boss’s house, anything just to kill the time. We had to

work until 12 noon on Saturdays, and we weren’t paid for any

holidays at all, not even Christmas day. I earned two pence

(old money) more an hour than the other chaps because I painted

castles and flowers on the boats. When I left I was earning 1s

9d (8½p) per hour (our rises came in ha’pennies, never more, and

sometimes I have even known of a farthing rise). So when I was

married and left there I was earning about £3 a week, and that was

for about 65 hours.

Buffers

Metal plates were put on the fore (front) ends of the boats to

protect them from knocks and, in the winter, ice. These plates

were about as thick as a piece of cardboard, about 2 feet (60 cm)

long and about 15 inches (38 cm) wide, and they were put on starting

at the end nearest the stern (back), and then overlapping so that

when they rubbed along they were not torn off. This meant

nailing one edge, and then nailing through two where they

overlapped. Underneath, to make it watertight we used to put ‘chalico’.

This was a mixture of horse manure and tar boiled for hours in a

large cauldron like a witch’s cauldron. We spread it all over

the part of the boat that was going to be covered with plates and

then on top of that we put a sheet of felt. When we nailed the

plates on, as we hit the nails with the hammer this chalico would

squirt out all over our faces and then we had to wash in paraffin.

On top of the plates were guards, average 12 feet (3.5 metres) long,

and they came round on the top edge of the boat and then the next

one not quite so far, and the next one not so far as that, and they

were nailed with huge spikes and they were ‘rubbing guards’.

At the stem (front) of the boat, there was a huge piece of wood for

the planks to go into, and also a ‘stem bar’ which was a big length

of iron that was ‘splayed out’ at the end. This was done by

heating it until it was white hot and then splayed with a big sledge

hammer until it looked like a pancake. This was nailed on to

the top of the deck over and down the stem post and under the boat

where it was splayed out again. This bar graduated from about

½ inch (12 mm) thickness to about 3 inches (7.5 cm) where it took

all the blows.

Not All Work and No Play

The men I worked with were all big strong men, and to relieve the

boredom, or to compensate for the bad weather conditions, we amused

ourselves by having contests to see who could pick up the heaviest

piece of wood or something like that. I was not very big, but

like my father also, I had very strong arms, and could lift two 56

lb (25.4 kg) weights that we used to weigh the corn, right over my

head. During the summertime, seldom a day passed without

someone going into the canal - pushed in I mean, not falling!

To get from the dockyard to the mill there was an obstruction (a

chimney), and to get round there was a narrow ledge, one brick wide,

but there was an iron rail to hold on to and swing round the

chimney. We would catch hold of this iron bar and swing round onto

the other side with no trouble at all. However, one day one

old chap slipped and he was hanging down on the bar with his feet

just above the water. Of course, we did not help him (you did not do

things like that), so we went and rapped his fingers until he fell

into the canal! He swam across the canal to the towpath and went

home; we didn’t see him again all day!

At the yard we kept an old punt which we used to go round the boats

when we were working on them. Well, there was this old

hunchback chap at the yard (who taught me an awful lot about boats

as he was a lovely workman) and he had to write the name on the end

of a boat, so he had to go out on this punt to do it. He

didn’t like going in the punt. He untied the punt to go round

to the other side of the boat he was painting and it started to

drift away. He was hanging onto the boat with his hands and

his feet were in the punt, which was getting further and further

away. He was shouting for help and although he was very old

and a bit crippled, we still waited a little to see a bit of fiun.

We caught him just before he fell in. He never went in the

punt again!

They seemed to rely on me to do some things which other people

wouldn’t do. When we launched a boat - sideways down into the

canal - it was held in the first place with chains round some big posts and

it was on two big baulks of timber with a railway line down the top

of each one so that it could slide down into the water when the

chains were released. If the chains were released and the boat went

‘chains and all’ into the water, the chains had to be recovered - so

they said “Harry, go round the other side and lift those chains ofl”. Well, the boat was there, waiting ready to go with nothing holding

it. Of course, I went round the other side, unhooked both chains and

just as I was about to walk away the boat started to move. I was on

the canal side so I just grabbed the top of the boat and went down

in the water with it. It creates a terrific splash when 72

feet (22 metres) of boat hits the water sideways - in fact it had

dug the towpath away where we launched these boats, as the water

washed over the towpath and into the field behind. My mates never expected to see

me again, but I clung to the boat - it was just fun!

Overhaul Time

Although there was usually one boat on the stocks, we did have boats

which came to be recaulked and repaired. We used to make sure the

boats were waterproofed by caulking the gaps between the planks and

where they were joined lengthwise. To do this we used ‘oakum’. The

oakum was like a girl’s plait as it came off the ball and we could

hammer it in the gaps and then coat the whole thing with pitch

which we would make by boiling tar, We had an ordinary mop and a

bucketful of pitch, and

we would give the boat a couple of coats and it would dry all hard

and glossy.

The boat people stayed in a ‘change boat’ (one kept at the yard

specially for this purpose). When the boat arrived at the yard for

recaulking with the family aboard, the cabin would be absolutely

alive with bed bugs which were nasty things - they looked like

ladybirds. When the boat family moved into the change boat we closed

all the apertures up in the cabin with wet sacks, then we put a tin

full of

brimstone in the stove, this sent off choking yellow poisonous fumes

when it was burning. We used to set it alight by heating a lump of

iron in the blacksmith’s fire and then lifting the wet sack on the

hatch and dropped the hot iron into the tin of brimstone and then

quickly dropping the wet sack back over the hatch. After a day and a

night the cabin was swept out and a shovelful of dead bugs, mice and

other

creatures was disposed of. The boat people were really very, very

clean, although people did not think so, but when they picked up a

cargo there were more bugs in the cargo, so they did not stay free

of them for long after stoving.

A Horse’s Life

The yard that I worked for was taken over from a yard that had all

wide boats and they used to take all the hay and corn up to

Paddington because at Paddington there was a big fleet of horses in

stables and then they used to bring the manure from the stables back

again - and that was all they did. Anybody who took a boat up could

leave their horse up there, have another one to bring the boat back

and then pick their horse up the next time they went there,

refreshed and well fed and looked after. Unfortunately barge horses

did get injured sometimes. At each lock the towpath goes down at a

sharp angle because the level of the canal drops, and when the horse

was pulling the boat with a boatline, straining to get it out of the

lock (once a barge was moving it was easy), the line very often

snapped, and because the horse was pulling with all its might it

ended up in the canal. If you look at the side

of the main canal, every so often you will see some shallow steps,

about a yard wide, going down the side of the towpath into the water

and these were put there specifically to get the horses out of the

canal when they fell in. These steps were built against each lock,

as it was accepted that the horses fell in and however good the line

was, it gradually got chafed in use and eventually broke.

The barge-horses used to have a food tin, like a nosebag, with a

strap, and this tin would be painted like the barges with roses and

other typical barge patterns, and the horse would feed as it was

pulling the barge. Along the traces on the horse’s harness,

they would thread small knobs, like cotton reels, and each one was

painted a different colour - everything they owned had to be painted

in some way. In the summer the horses had what looked like

mittens put over their ears to keep the flies off.

One day I went down to fetch a boat with a horse that belonged to

the miller

next door (William Mead) and he sent one of his men with me. This

man was not

familiar with horses or boats. The boat was at the bottom of a very

steep bank, about

5 or 6 feet (2 metres) deep, and I hooked the boatline on the boat

and then on the

horse. I told this man to stand on the canalside of the horse and

keep its head over

towards the hedge. I then got in the boat ready to steer it. Well,

this horse wasn’t

used to boats and it pulled the slack line up that laid on the path

and then, of course,

it suddenly went tight. The man was on the hedge side of the horse

because he was

frightened and when the horse felt the sudden tug of the line it

threw its back feet

round and went ‘wallop’ down the steep bank into the water on its

back. It was a

beautiful, very big horse, and I had to get in the canal, unharness

it and walk it up

the canal until I got to a place where it was low enough at the bank

to get it out.

They put it in a stable lined with straw and made specially warm

(called the

hospital) because it was shivering with cold. They gave it brandy

and bran mash,

but it caught pneumonia, and it died the next day. In those days a

horse like that

was worth about £400.

Boat building is not all plain sailing

We used to turn out narrowboats like sausages from a sausage

machine! There was a

frame made of posts set in the ground, standing up about 20 inches

(50 cm) from the

ground and then there were big, hefty pieces of timber round it so

that it was

roughly the shape of the boat. We laid elm planks, 3 inches (7 cm)

thick and 15

inches (38 cm) wide, and more than the full width of the boat. These

elm bottoms

were already cut and we got them from Easts at Berkhamsted but the

planks that

followed up came in the raw state with the bark round the edges,

14 inches (4.5 cm)

thick, 14 inches (35.5 cm) wide and 30 feet (9 metres) long. The

details for making

a boat are very complicated, but that was how we started off.

The narrow boat (or monkey boat) was the one that was mostly built

and used,

but we did build one boat which was twice the width of the normal

boat, and it was

called the Progress. The designers said that it was the

boat to beat all boats and they were going to have big fleets of them. It was 14 feet

(4.2 metres)

wide instead of 7 feet (2.1 metres) and it had special decking over

it with hatches

and a big beam right down the centre of the boat, above the height

of the boat, and

tarpaulins laid over, so that it was like a ship really. After we

had built it, it was taken to a place called Hatton to open a new flight of locks. The

Duke of Kent was

at Hatton and we had to go there and put seats out with the names of

all the

important people who were going down in the boat and lay a red

carpet and make

all the preparations. We had a rehearsal and one of my bosses took

the part of the

Duke of Kent. The next day was the real thing with champagne and

everything, but

we weren’t there that day so we did not have any champagne. Unfortunately, the

people who designed Progress did not take into account the fact that

two boats of

her size could not pass anywhere on the canal, so more like her were

never built,

and she ended her days as a mud boat on the River Thames.

At the yard we also built other boats. We built a big tug during the

war, which

could pull as many as ten 100-ton barges behind it. It was called

Bess and it was so

huge that we did not build it on a frame, but on the ground. It was

72 feet (22 metres) long and 14 feet (4.2 metres) wide. We had

to build a half-section of it first,

from fore to aft (lengthways), full size! We built it with what we

called ‘harpings’

which were much like outsize plaster laths (thin strips of wood),

exactly as the finished boat would be, and this was then used to take measurements

from as guides

in building the actual boat. This was because although narrow boats

could be

produced with ease as so many were made, something as unusual and

large as this

posed more of a problem. When it was launched all the schoolchildren

had half a

day’s holiday to watch the launch and it just wallowed down in the

mud at the

bottom of the canal and all the schoolchildren hung on to a rope and

helped to pull

it out of the mud again. As there were no engines or boilers in it

at this stage the

nose of the tug stuck up in the air, so sand was put in the nose to

weight it down,

and it was such a big boat that it took 20 tons of sand. They had to

bring the nose

down to get the tug under the bridge to get it down onto the main

canal. It was

towed along by horses and when they got to Winkwell they had to take

the strips of

wood ofi the sides and take the Swing Bridge off as well, to get the

thing through.

Later, though, the engine and boiler were taken out and it was

converted to diesel.

We also made Rothchild’s fishing punts - dozens of them. They were

just a flat boat and across the middle was a tank, and they