|

. . . . AND THOSE AROUND TRING

CHAPTER VI.

PITSTONE

POST

MILL

BUCKINGHAMSHIRE

Fig. 6.1: Pitstone post mill

Despite its inanimate nature, Pitstone post mill always appears to

be lonely, particularly so when viewed from a distance in

silhouette, its upper sweeps outstretched like two skeletal arms

pointing accusingly at the sky. And well they might, for a sudden

gale caught the miller unawares, and before he could wind the mill

almost destroyed it. Thanks to its donor, Leonard Hawkins and to the

band of brothers who toiled for many years over its resurrection, Pitstone windmill continues to stand, a lonely sentinel over the

bare expanse of Windmill Field.

The village of Pitstone derives its name from the Anglo Saxon for

‘Picel's thorn tree’; it appears in the Domesday Book (1086) as ‘Pincelestorne’,

a holding of William the Conqueror's half-brother, the Count of

Mortain, who also held land in nearby Tring. Although not listed in Domesday, a watermill probably existed in Pitstone as a necessity to

village life, but it was not until 1231 that the first watermill is

recorded. Further references appear in 14th, 16th and l7th century

documents, the mill referred to latterly probably being that which

still exists at Ford End and which is opened to the public.

The Domesday Survey predates the coming of the windmill to Britain

by a century or more. If a windmill did exist at Pitstone during the

medieval period, there is no record of it. The first mention of a

windmill arises in records held in the Bucks Record Office for the

years 1624 to 1628. These refer to the tenants of the ‘Windmill at

Ivinghoe’ and to payments made to carpenters working on its

structure. They further suggest it to be an old mill at the time. Archaeological evidence of its age exists in the date ‘1627’ carved

into one of its internal timbers, while dendrochronology suggests a

date of 1590. Neither can be relied upon, for the timbers could well

have been recycled from an earlier building. Whatever the mill’s

exact date-of-birth, there is sufficient evidence to place it at

least in the early 17th century, making it one of the oldest

remaining windmills in Britain, possibly the oldest.

Fig. 6.2: hand reaping in

Windmill Field, Pitstone

In his historical note on nearby Brook End watermill, Keith Russell,

the present owner, has this to say about the close relationship of

Pitstone’s three mills . . . .

“Pitstone Windmill (dated 1627) has always been linked with Pitstone

Mill. The two were connected by a ‘good road’ then known as the Mill

Way, and it followed the line of what is Orchard Way. The Whistle

Brook, also known as the Missel Brook because of the propensity of

fresh water mussels therein, was the source of power. Often in the

past the Windmill, Pitstone Watermill and Ford End Watermill have

been worked simultaneously by the same individual, which is not

surprising when you realize that as the crow flies they are all just

a short walk away from each other.”

The earliest person known to be connected with Pitstone mill was

John Burt, who in 1770 occupied The Mill House (Brook End) and owned

both wind and watermills. These he bequeathed to his son James in

1786. Two years later James insured both mills and other premises

with The Sun Fire Insurance Company for the sum of £400; in 1801 he

switched to the Royal Exchange Fire Insurance Company, the cover for

the windmill stating . . . .

“On his Corn Windmill house, timber built, situate at a distance

from the above [i.e. Brook End mill house] £50. On the standing and

going gears, millstones, machines, etc. therein £50. Warranted no

steam engine in either mill.”

The caveat is interesting, not so much because steam engines were

regarded as an increased fire risk, but the suggestion is that at

this early date they were already being used in mills to supplement

wind and water power.

James sold both mills at auction at the Rose and Crown Inn at Tring

in 1810, the windmill being advertised as . . . .

“. . . . a capital and substantially built Wind Corn Mill, standing in the

open field of Pitstone about two furlongs from the house, on an

excellent site, and a good road; the whole admirably calculated for

a mealman, being situate in a good corn country where mills are

scarce. Land tax £1-3-4d. per annum.”

The buyer was probably the Grand Junction Canal Company (the company

was to sell both mills in 1842) who might have wished to gain

control of the ground water in the area.

Pitstone windmill’s next recorded miller was Benjamin Anstee, who is

listed in Pigot’s Directory for 1823 and whose surname was also

carved on the old mill door. The windmill again changed hands in

1842, when Francis Beesley bought it from the Grand Junction Canal

Company, [7] retaining the mill until 1874 when it was bought by the 3rd

Earl Brownlow, owner of the Ashridge Estate. The windmill was later

let to the Hawkins family, tenants of the surrounding Pitstone Green

Farm. John Hawkins employed a miller named Jim Horn, who is believed

to have worked the mill until around 1894, to be followed by Charles

Simmons, the last recorded miller. Following the death of the 3rd

Earl and the break-up of the Ashridge Estate, the Hawkins family

bought the farm and windmill in 1924.

The body of the mill was renovated in 1894, which included

re-boarding. The author Stanley Freese, writing in the 1930s, states

that the job was carried out by a workman named John Payne, “said to

have been exceptionally clever with his tools, being able to do

inlaid work amongst other things”. The work being completed at

Christmas, Payne then “got on to the top ridge of the body and

walked along it in his bare feet to fix a sprig of holly on the

tail”. The mill’s post and trestle were open to the weather until

the roundhouse was built shortly after the renovation work was

completed, for it bears the date 1895 upon a cement slab low down on

the outer wall. Freese records that it was of yellow brick (it is

now whitewashed) and had four doorways, but the doors and frames

were never fitted.

In 1902 the mill’s working life came to an abrupt end:

“. . . . a great gale rose and caught the mill tail-winded, thrusting the

sails forward, lifting the tail of the windshaft out of its seating,

and finally blowing two sails off altogether.”

Fig. 6.3: Pitstone Mill

derelict c.1930

The damage was such as to place it beyond economic repair and over

the following decades Pitstone mill fell into progressive decay. In

English Windmills Vol. II (1932) the mill’s plight is described thus

. . . .

“This is a post mill standing alone in the

middle of a very large field, on the road from Ivinghoe to Pitstone.

It is derelict. The roundhouse of yellow brick was a

comparatively recent addition and is now covered with corrugated

iron. The trestle timbers have some good moulding, but had

apparently weathered a good deal before the addition of the

roundhouse. . . . It has now no ladder, tail pole or sails.

There are remnants of machinery still in position and two large

millstones on the floor. It should be emphasised that such a

building is not safe in any way, and that visitors can see all that

need be seen from without.”

|

|

|

Fig. 6.4: Leonard

Hawkins |

At some time during the 1930s, Stanley Freese wrote an interesting

account of Pitstone mill based on his observations and on interviews

with people he does not name, but probably members of the Hawkins

family. In Freese’s view, the mill had sufficient similarity to that

at Brill to suggest that Pitstone was the product of the same

millwright. [8] He goes on to describe the mill in considerable detail,

giving some idea of the miller’s everyday activities . . . .

|

“Two pairs of stones, 3ft 10in and 4ft, are placed side by side upon

the upper floor. . . . in a good east wind both pairs of stones

could be worked, but this entailed a lot of rushing about the mill;

one pair could often be worked with two sails half-clothed and the

other two furled. . . . When worked ceased, the sweeps were always

placed on the cross, so that the tips were out of reach of mischief

makers who might otherwise climb up the bottom sail and get into the

trap door in the breast of the mill over the windshaft neck. This

extremely unusual door . . . was provided for the purpose of

greasing the neck bearing . . . . and in milling days this neck was

greased every morning before starting work.” |

|

|

|

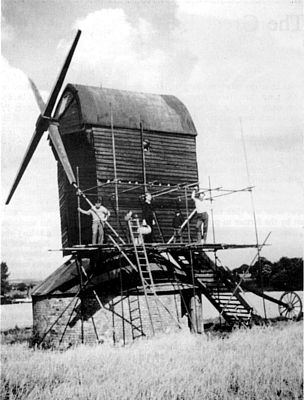

Fig. 6.5: restoration |

It was not until 1937 that the resurrection of Pitstone mill began. Its then owner, Leonard Hawkins (fig.

6.4), dismayed by its sad

condition and his inability to restore it, gave the derelict hulk to

the National Trust together with access rights across his land. Shortage of funds meant that little could be done other than to make

cosmetic repairs [9] and stabilise the mill’s structure to prevent

further deterioration, although work on the roundhouse that had

begun in 1895, was completed, two of its four doorways being bricked

up. In 1938, Freese records that the fourth was “provided with a

beautiful iron-studded oak door the like of which has probably

seldom been seen on a windmill.”

Other than necessary remedial work to stem the ravages of time, no

further restoration took place until 1963 when the Pitstone Windmill

Restoration Committee was formed and a plan drawn up to restore the

windmill to full working order by voluntary effort. A survey of the

structure showed that, although much needed to be done, it was in

better condition than had been feared. Donations from various

sources raised £1,000 towards the restoration, materials were given

free or at a discount, equipment was lent, and the carpentry

students at Aylesbury College made the mill’s sails. After much

voluntary effort, Pitstone mill again ground grain in 1970.

Pitstone mill is now maintained as a non-working exhibit by the

National Trust. |