|

One early product of the Industrial Revolution was our canal network, which improved

quite dramatically the

means of transporting goods, particularly those in bulk such as coal,

grain and manure (for in that horse-powered age, large quantities were shipped

from the cities to fertilise the land). Many local businessmen and farmers soon became aware of the

potential benefit that this new form of transport could have on

their profits, and factories, mills and wharfs of different types

soon sprang up along the banks of the new waterways.

The Grand Junction Canal (since 1929, the Grand Union Canal) reached

north-west Hertfordshire at the end of the 18th century.

Fortunately for Tring, which would otherwise have been bypassed, the need to provide the

Canal with a

reliable

water supply as it crossed the ridge of the Chilterns led to

the a plan to construct a feeder ‘ditch’, which led westwards along the

contour between Bulbourne and Wendover, passing the northern

outskirts of Tring on its journey. However, pressure from local farmers and land owners

led the Grand Junction Canal Company (GJCC) to apply to

Parliament for an Act to make the ditch navigable.

In due course the following

statutory notice appeared in the newspapers published along the

route

of the GJCC, giving notice of the Company’s intention to apply to

Parliament for an Act which, among other things, would authorise

them:

“. . . . to make navigable, the cut or

feeder now making, and intended to be made, by the company of

Proprietors of the Grand Junction Canal, from the town of WENDOVER,

in the said county of Buckinghamshire, to the summit-level of the

Grand Junction Canal, at Bulbourne, in the parish of Tring, which is

to pass in, to, or through the several parishes of Wendover, Halton,

Weston-Turville, Aston-Clinton, Buckland, and Drayton-Beauchamp, in

the said county of Buckingham; and the parish of Tring; till it

joins the said summit-level at Bulbourne aforesaid. Dated this 5th

day of September, 1793.”

E. O. Gray, Aston Chaplin, Clerks

to the Company

Exactly when the Wendover Arm was completed is unknown, but it was

probably shortly after 1794, for in his progress report of May of that year

Chief Engineer William Jessop states that “About seven-eights of

the Wendover Canal is cut”, and in a GJCC circular of November,

1797, reference is made to “The Wendover collateral line, now

finished for the sake of the water.” Thus, the Arm was widened and made navigable, and

wharfs were built at, among other places, Gamnel (Tring), Buckland and Wendover

[11] to

cater for the trade that commenced when the main line of the canal reached Bulbourne

Junction in

1799.

The earliest reference to milling in the

Gamnel locality is in the same year. The site now occupied by Tring Flour Mill (Heygates Ltd.)

was in the vicinity of a water mill –

possibly in New Road, near the Baptist Chapel – that had been bought

by the GJCC and then dismantled, its water supply

having been diverted into the canal summit. The loss of the mill pond affected the local Baptist community, whose

traditional baptism ceremonies were thus curtailed:

“The Water Mill at New Mill is now sold to

the Canal Company, and the pond cannot therefore be used in future

for baptism. A baptistery is being made in front of the pulpit in

the Chapel [where it remains].

The Mill had previously been in the ownership of friends of the

Chapel, and after a baptismal service the women used to change their

clothes there, and the men walked up to the Chapel to change. The

open-air baptisms were a good thing [to be] done away with,

although they were greatly preferred by the Minister and some

members of the Chapel. The services were always scenes of much

hostility and abuse from certain people in Tring, the participants

in the service oftentimes being pelted with filthy missiles.”

From the Tring

Vestry Minutes for 1799.

The GJCC Minutes for the 14th October 1800 record that a wharf at Tring

– presumably

that at Gamnel, now generally known as

“Tring Wharf”

– was sold by auction for three years from 29th September. It

was taken by James Tate, a coal merchant and barge owner, for £15

per annum. Then, on 5th July 1810, the first reference to “Gamnel”

appears in the GJCC Minutes, which record that

the

freehold of what appears to be the same site was sold . . . .

“. . . . by Deed Poll under Common Seal in Consideration of Four hundred

pounds paid to them by the said William Grover grant and release to

the said William Grover his Heirs and Assigns All that wharf Land

and Buildings thereon containing one acre and three roods more or

less situate next Gamnel [canal] Bridge in the Parish of Tring . . . . ”

THE GROVER FAMILY

William

Grover must have seen a business opportunity in developing the site.

It comprised a triangular piece of land on which he (or possibly his

brother James) later erected a windmill and set up in business at

the wharf sending and receiving consignments of goods by canal.

Exactly when the windmill was built is unknown. Andrew

Bryant’s 1820-21 map of Hertfordshire includes a windmill symbol at Gamnel Wharf,

while Pigot’s Directory for 1823 lists the brothers William and

James Grover as ‘millers’ at Gamnel, but the earliest record of the

wharf and premises is in 1829, when they were held by William

Grover, while James Grover held the windmill and a house on the same

site at a rateable value of £13. 5s. 0d.

At some time after 1829, the partnership between the Grover brothers

ceased. Why, is unclear, but following their father’s death in

1820 it is known that there arose a prolonged dispute between the brothers concerning the terms of his will. In her

history of Aldbury, Jean Davis refers to a vestry dispute of 1828,

and states that . . . .

The fact was that, at some time before he died in 1820, John Grover

had given up his baker’s shop in Aldbury and moved to Tring Wharf. Having acquired some land in North Field, he proceeded to build a

house there adjacent to the road, which he left to his son James

with the crop and implements and household goods. According to John

Clement, watchmaker and Baptist preacher of Tring, James’s brother

William disputed the will, which finally went to arbitration. James

is reported to have said that he was wronged of ‘hundreds of

pounds’.”

For whatever reason, James set out to build and work nearby

Goldfield windmill (Chapter VIII) in competition with his

brother. The 1839 edition of Pigot’s Directory lists

James at

Goldfield, while Gamnel Wharf was run by William Grover &

Son in partnership. Moving on to 1841, the Census records William

Grover, then age 60, at Gamnel with his son Thomas, and the Hillsdons, father and son, who were later to set up business as

millwrights in Chapel Street, Tring (Chapter

V). All four are

described as millers.

The next public reference to the Grover family appears in January

1843, when a brief notice in the London Gazette announced the

dissolution of the partnership between William Grover and Son, wharfingers, of Tring Wharf and Paddington.

No reason is given, but

the inherited rumour is that William Grover became insolvent, which

might explain why, in the following month, he disposed of the

business to his sons-in-law. The following notice appeared in the

Bucks Advertiser:

“William Grover, in the town of Tring in the County of

Hertfordshire, having on the 28th day of January last disposed of

the business of wharfinger, coal and coke merchant and mealman, and

dealer in hay, straw, ashes, and other things, lately carried on by

him in partnership with Thomas Grover, at Tring Wharf, and at

Paddington in the County of Middlesex, under the firm of ‘WILLIAM

GROVER & SON’ to his sons-in-law, William Mead and Richard Bailey.

Messrs. Mead and Bailey beg to announce that they will continue to

carry on the same business, upon the said premises, in partnership

under the name of ‘MEAD & BAILEY’. All debts due to and owing from

the said William Grover, will be received and paid by Mead &

Bailey.”

It is interesting that the Grovers describe themselves not as

millers, but as “wharfingers”, which suggests

that their principal business activities were the shipment of

produce by canal and the resale of imported bulk commodities, such

as coal and coke. In an age before the development of road transport,

and with the nearest railway [12] goods yard almost two miles from Tring

town centre, the Wendover Arm was not only an important source of

water for the Grand Junction Canal, but of commercial importance to

the town and its surrounding area. Indeed, it is known that the Arm was

used to convey grain not only to the windmill at Gamnel, but to that

at Wendover (Chapter X), it too being located

strategically close to the town’s canal wharf.

THE MEAD FAMILY

After 1843, the Grovers disappear from the story of Gamnel Wharf,

while Mead and Bailey continued to offer a diverse range of

services, advertising themselves as millers, coal merchants,

wharfingers and water carriers; and a few years later, the partners

added to their interests by dealing in horse manure, which they

shipped out of London. It is likely that Bailey managed the wharf at

this time, for in the 1851 Census he describes himself as “Miller

and Wharfinger”, while Mead appears as “Farmer and Miller” (the Mead

family continue to farm in the area).

At this time the workforce numbered around 30 men and the Census

returns list all the families living near to each other in the

immediate vicinity of the mill. In those days William Mead lived on

site, in a handsome house next to the yard, but only owned half the

area taken up by the mill of today. But it is open to question

whether this was a close-knit and caring community, for a

contemporary account relating to one of the mill’s employees rather

belies this view.

William Massey, who worked as a labourer at the mill, lived with his

family on the wharf where he rented a hovel from the miller for a

shilling a week. In his

biography of Gerald Massey,

William’s eldest son, David Shaw wrote:

“For this money they [the Massey

family] were given a damp flint stone hut

with a roof so low that it was impossible for an average adult to

stand upright. Having paid the rent, nine shillings remained from

William’s weekly wage to provide a minimum subsistence.”

Gerald Massey was to become a Chartist agitator, later acquiring

renown in literary circles as a poet and author. Some years after

William’s death, Gerald Massey had this to say about his late

father’s employment at Gamnel Wharf . . . .

“I know a poor old man who, for 40 years, worked for one firm and

its three generations of proprietors. He began at a wage of 16s. per

week, and worked his way, as he grew older and older, and many

necessaries of life grew dearer and dearer, down to six shillings a

week, and still he kept working, and would not give up. At six

shillings a week he broke a limb, and left work at last, being

pensioned off by the firm with a four-penny piece! I know whereof I

speak, for that man was my father.”

Regardless of whether the Meads treated their employees in such a

Dickensian manner, their business prospered. It centred on the

windmill, which old photographs show to be a brick-built 6-storey

tower mill with four double-shuttered patent sails, a fantail, with

a gallery on the second floor. The cap was in the ‘Kentish style’,

with an extension at the rear to support the fantail and its stage.

It was considered to be a relatively large mill having power

sufficient to drive at least three pairs of millstones. While no

record exists of the mill’s machinery, it was probably comparable to

that in the later tower mill at Quainton (Chapter

XI) and, judging from photographs of Gamnel Mill, was of similar

external size and appearance.

The partnership between Mead & Bailey ended in 1856 on Bailey’s death, and for the next 88 years the Mead

family became

inextricably linked to milling and to other business activities at Gamnel Wharf.

In the year following Richard Bailey’s death, his widow, Sarah,

bound their son Thomas in apprenticeship for five years as miller

to Edward Mead. On the 15th April 1857, a Tring solicitor drew up the Indenture in wording typical of the time . . . .

“. . . . the said apprentice his Master shall faithfully serve, his

secrets keep, his lawful commands everywhere gladly do . . . . he

shall not waste the goods of his Master, nor lend them unlawfully to

any. He shall not commit fornication nor contract matrimony within

the said term; shall not play Cards or Dice Tables or any other

unlawful games; . . . . he shall not haunt Taverns or Playhouses nor

absent himself from his Master’s service day or night unlawfully . .

. .”

How a normal red-blooded young man coped with five years of such

conditions is hard to imagine today. Thomas Bailey’s mother also had

to agree to wash and mend her son’s clothes and to supply any

medicines that he might require. Although weighted greatly in favour

of the master, terms on the Indenture were not wholly one-sided, as

for his part the master agreed to . . . .

“. . . . Useth by the best means that he can to teach and instruct,

or cause to be taught; finding unto the apprentice sufficient Meat,

Drink, Lodging and all other necessaries during the said term . . .

.”

THE FIRST USE OF STEAM

By the 1840s it appears that a steam engine had been installed at

Gamnel to supplement wind power – which by then was fairly common

practice – for Mead family papers refer to one of the occupants of

the mill cottages as

“Thomas Rowe, a stoker at the

mill”

(the 1861 Census also lists

19-year old Samuel Bull as an “engine stoker”). Nothing

is known about the steam engine, but evidence suggests it was separate from

the windmill . . . .

“Prior to my return home Gamnel [a.k.a. Tring]

Flour Mill was run by my brothers Edward and Thomas, but the former

took the mill at Hunton Bridge, near Watford, and said I might have

his share of Gamnel for £1500. This I accepted, giving notes

of hand [i.e. promissory notes],

which I paid off when I had earned the money. I worked hard,

sometimes up to 10 o’clock, and if windmill and steam-mill

were both working I would stay until 1.00 o’clock in the

morning.

In these cases I slept at my brother William’s house . . . .”

John Mead, autobiographical

sketch, c.1930s.

. . . . unlike the practice adopted at Quainton windmill, where a small

steam engine was installed on the meal floor, its steam being piped

from an external boiler house and the engine coupled to the

windmill’s spur wheel (and hence millstones, etc) via an iron shaft

and cog. This type of arrangement is shown in

plate 21.

By this time the business at Gamnel Wharf was run by William Mead’s

third son, Edward, who also rented the windmill at Wendover (Chapter

X). Edward Mead had become a busy man, having acquired

milling

interests at Watford, Hunton Bridge and at Chelsea, where

he is believed to have installed the UK’s first roller mill.

BUSHELL BROTHERS’ BOATYARD

From about 1850, local man John Bushell was employed by the Meads to

build and repair their fleet of barges. These were used to

bring grain to the mill,

mainly from London’s docks, with return cargoes of flour and

other commodities (probably including hay and straw). At that

time canal boats were often built in small boatyards run by a few

men and this applied to the Gamnel Wharf boatyard, where the craftsmen worked in the open air in

the most extreme weather.

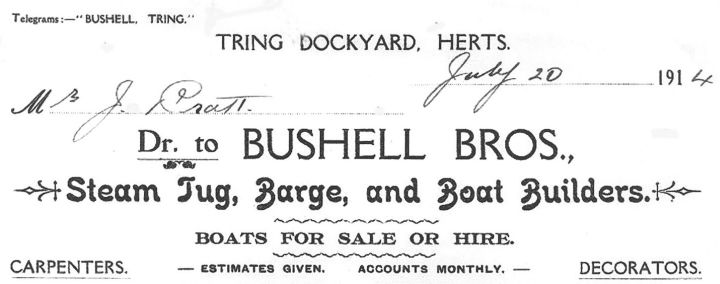

Fig. 7.2: Bushell Brothers’

boatyard photographed in January, 1914.

A large boat-building shed was later constructed to protect the men

from the elements.

Modernisation at the mill in 1875 resulted in John Bushell’s son

Joseph leasing the boatyard and developing it into a separate

business, while continuing to meet the Meads’ requirements for

building and maintaining their canal craft.

MODERNISATION

Fig. 7.3: the new steam mill

A particular

milestone was reached in 1875, when Thomas Mead took the bold step

of erecting an imposing brick-built grain mill adjacent to the

windmill, its 5-storeys allowing sufficient headroom for a large

beam engine capable of driving five pairs of

millstones.

The installation of this new machinery did not go without incident,

as a local newspaper reports . . . .

“Accident — There was a shifting of the old boiler out of the old

engine house at Mr Thomas Mead’s flour mill into the new one on

Tuesday; and in order to do this, the boiler had to be raised four

feet. A small space had been left at the end for the jack, and the

block underneath slipped when the boiler was raised about two feet,

and caused the boiler to run ahead, striking against Lot Denchfield,

fracturing his right thigh and left fore arm. Denchfield was at once

taken to the County Infirmary at Aylesbury.”

As the century progressed, advances in technology swept away

old systems, and milling was not exempt. In 1894 a further step was taken when Thomas Mead

installed the recently-developed roller system (Chapter 3,

Appendix), for a time running it in conjunction with the windmill. Then in 1905, the old Bolton & Watt-type beam engine was replaced by

a Woodhouse & Mitchell tandem compound condensing engine, rated at

120 hp, which drove the mill until it converted to electric power in

1946.

Fig. 7.4: Gamnel Wharf tower

mill about to be pulled down, 4th May 1911

The early 20th century saw the rapid demise

of windmills throughout the land. After some ninety years of faithful service,

on the 4th May 1911 the tower mill at Gamnel Wharf was pulled down. A local

newspaper gave the following account . . . .

“Removal of a Landmark — On May 4th a familiar landmark was

demolished. For many years the old windmill where Mr. Mead and his

ancestors have long carried on their business, has stood at Gamnel. The leisurely business methods of bygone days have had to give place

to more up-to-date arrangements and so the ground on which the old

mill stood was wanted for an extension of the steam-powered mills. Under the personal direction of Mr W. N. Mead the structure was first

undermined, wooden struts taking the place of the brickwork and when

it was ready a steel cable and winch hauled it over.”

Fig. 7.5: the deed is done

As the years passed, other changes came to Mead’s flour mill. In

1916, horse transport was supplemented with a Foden steam lorry,

this being joined by a Napier lorry in 1918, the bodywork of which —

and of all further lorries up to WWII — was constructed

by Bushell Brothers. The coal business, which advertisements suggest had

been important since the earliest days of Gamnel Wharf, ceased at

the outbreak of World War II. Much imported wheat was now

being used, which

was shipped by barge from Brentford to Bulbourne near Tring, where

it was transferred to a horse-drawn narrowboat for

its passage up the Wendover Arm. Barge traffic continued on

the Arm until after the WWII, when road haulage took over.

THE CLOSURE OF BUSHELL’S BOATYARD

Fig. 7.6: Bushell Brothers

were versatile, supplementing their boat-building with carpentry

(they carried out repairs on

Pitstone Mill), decorating and

building vehicle bodywork

Joseph Bushell’s two sons, Joseph junior and Charles, had taken over

the boatyard in 1912, renaming the business Bushell Brothers. But as

canal traffic and the market for new barges and repairs declined,

more varied work had to be sought.

Besides their work on narrowboats, the firm is known to have built

and repaired pleasure boats, maintenance flats, wide boats, tugs and

even a fire float, while their letterhead advertised boats for hire,

carpentry and decorating services.

Fig. 7.7: and example of

Bushells Brothers’ bodywork building skills

Shortly before its closure in 1952, Bushells were constructing and

painting coachwork for commercial vehicles. But in local minds the

boatyard will always be remembered for its fine wooden narrowboats, a few

of which have been preserved by enthusiasts.

Fig. 7.8: calendar cover for

1941

HEYGATES FLOUR MILL

|

|

|

Fig. 7.9: William

Mead judging wheat |

Thomas Mead’s son, William, died in April, 1941. There being no sons

to take over the business, it passed into the control of his

executors and trustees. The Mead name finally disappeared from the Gamnel scene in 1944, when the business was taken over by Heygates

of Bugbrooke Mills, Northampton, who for some time had assisted with the running of Gamnel

Mill.

Following the end of WWII, the mill’s storage silos and warehouses

were enlarged and, with the removal of the old south boundary wall

(latterly part of the carpenter’s shop) to create space for

expansion, the last tangible memory of Gamnel Wharf windmill

disappeared.

Today, flour milling continues at Gamnel Wharf but in a manner

greatly transformed from its wind and steam milling days. The

mechanical shafts, cogs, belts and sets of grindstones have long

been replaced by banks of cabinets that house sophisticated filters

and grinding rollers serviced by a network of pneumatic feeder

pipes. The finished product is no longer packed in the

two-and-a-half hundredweight (280 lbs.) sacks that carters like

William Massey had to deliver into baker’s lofts, sometimes carrying

each sack up slippery external wooden steps or ladders. Today, Gamnel’s modern automated packing plant fills 32 kilos (70 lbs.)

sacks, which are then neatly palleted, swathed in polythene sheet,

and loaded onto lorries by forklift truck. Some flour also leaves

the mill in bulk transporters.

As in the days of the windmill, only two men are needed to operate

the plant. But whereas in former times the two millers could process

half a ton of grain per hour, today’s electrically-driven equipment

operating under computer control, can mill 12 tons per hour; or put

another way, 100,000 tons of wheat is milled in a year resulting in

76,000 tons of flour, the bulk of the waste going into animal feed. The mill employs a workforce of 80, and 16 trucks deliver its

products to outlets throughout the south of England.

Fig. 7.10: a Sentinel steamer |