|

FOLLOWING the

collapse of Harney's Friend of the People, the demise of which

was foreshadowed some time earlier, Massey had to concentrate his

activities on lecturing. Despite his advertised large prospectus

it is not certain just how successful he was in obtaining bookings for

the spring of 1853, and he may have been limited to provincial

mechanics' institutes and working men's associations. Harney again

made two attempts at a weekly paper. The Vanguard which he

commenced in January of that year survived for only three months, and

Massey made no signed contributions to it, although an article ‘The

Political Refugees’ may have been written by him. The Beacon,

from October 1853 to January 1854 proved equally unsuccessful, and again

there are no signed contributions by Massey.

In the spring or summer of 1853 the family moved probably to

cheaper but much smaller rooms in 12, New North Street, Red Lion Square

where Massey's second child, Cecilia Geraldine was born on the 4

October. Due to her pregnancy and following the birth of Cecilia,

Rosina had been unable to continue with her clairvoyant consultations,

and their finances became once more a cause for concern.

Fortunately Massey was able to obtain a post later that year as

book-keeper to the publisher John Chapman, probably taking over the

vacancy from a Mr Hogg, who had been employed at a salary of £120 per

annum.[1] Chapman rented out some of the rooms

in his large Strand house, of which one occupant from 1851 to October

1853 was George Eliot, and held Friday evening literary discussions with

persons notable in the scientific and literary fields. Improved

financial prospects induced the family to move again, this time to

better accommodation at 28, Henrietta Street, Brunswick Square.

After the limited success of Voices of

Freedom, Massey was encouraged to prepare a further volume of

verse, incorporating into it his earlier poems. By January 1854

Massey had completed his best known poem, the birth to early death

tragedy of ‘The Ballad of Babe

Christabel’; while an unconscious premonition of ensuing events, the

Ballad was not, however, inspired by the death of his daughter,

Christabel, who lived to a ripe old age (d. 1934):

|

...

It fell upon a merry May morn,

I' the perfect prime of that sweet time

When daisies whiten, woodbines climb,

The dear Babe Christabel was born...

O happy Husband! happy wife!

The rarest blessing Heaven drops down,

The sweetest blossom in Spring's crown,

Starts in the furrows of your life! ...

And thus they built their Castles brave

In fairy lands of gorgeous cloud;

They never saw a little white shroud,

Nor guess'd how flowers may mask the grave...

And still her cheek was pale as pearl,

It took no tint of Summer's wealth

Of colour, warmth, and wine of Health:

Ah! Death's hand whitely pressed the Girl!

... |

The Ballad of Babe Christabel: together with other Lyrical

Poems which included a portion of the 1851 biographical sketch by

Samuel Smiles, was paid for by Massey and published by David Bogue in

February 1854 after being submitted unsuccessfully to other publishers,

including John Chapman. The reviews followed quickly.

Hepworth Dixon, chief editor of the Athenæum journal casually

picked it out from a number of other items marked for review on his

desk, and noticed one particular poem that seemed to be familiar.

He remembered that two years earlier he had been browsing in a bookshop

in the Gray's Inn Road while sheltering from a rain shower, and had

looked through a bound edition of Harney's Red Republican.

Inside the dust-wrap cover, under the index, had been a poem 'The Song

of the Red Republican' by G. M. that had been published originally in

Cooper's Journal. Yes, this was certainly the author.

Dixon was going to spend the Sunday in Brighton with Douglas Jerrold,

former editor of the Shilling Magazine and contributor to

Punch, so he took the book to show him. Both men were

impressed with Massey's natural poetic ability. Dixon reviewed the

book in the Athenæum, in which he introduced Massey as a young

poet — and as something more:

A man whose ear - though not yet tuned to the complete and glorious

harmonies of our English tongue - is sensitive to rhythm . . . whose

imagination throws out images in sonorous words . . . so that sound and

image seem identical . . . He is a true poet, - but he has grievous

defects . . . he lacks culture. He requires taste. His ear is defective.

(Yet), our workman-poet has become a teacher to his class. He speaks to

them in passion - counsels, exhorts, inspires them with his own vehement

and vigorous spirit . . . many a line suggests - and many an image

vivifies - the idea of a vast social revolution as that which appears to

him the natural and inevitable path of issue into a better state.[2]

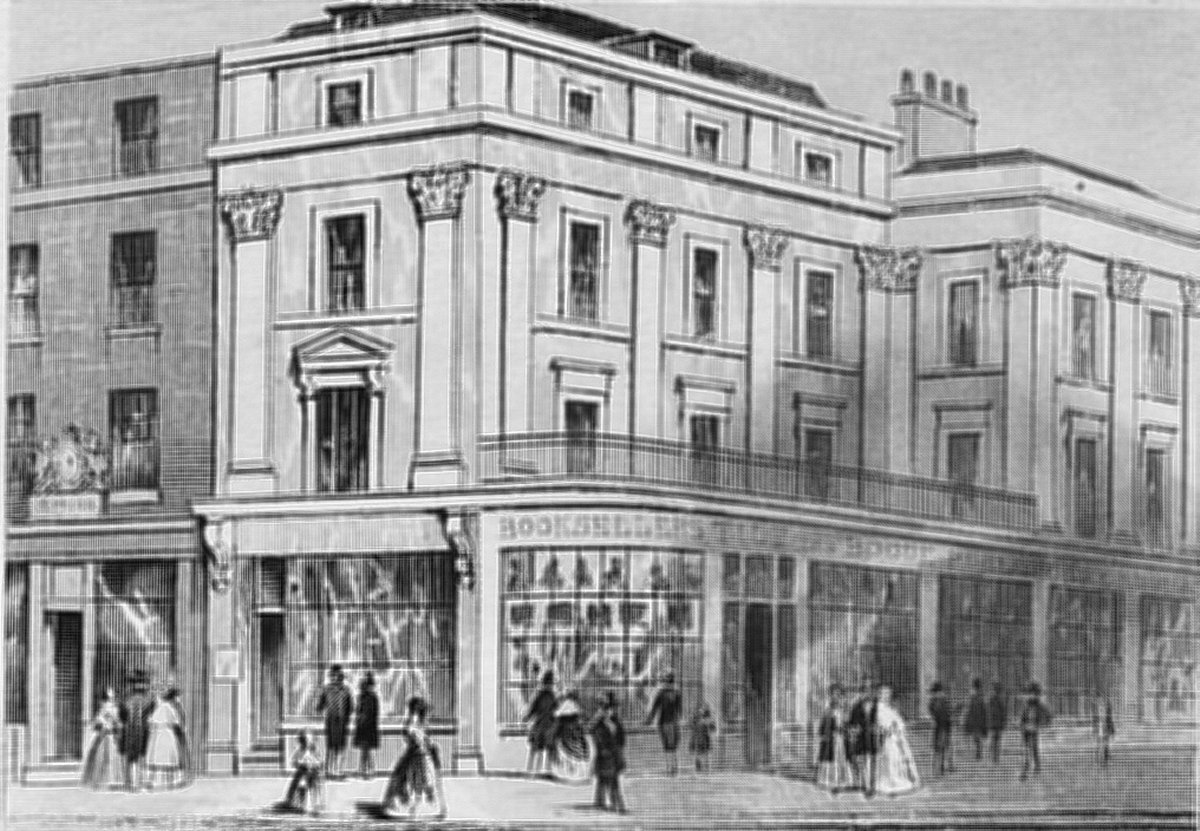

Charles Tilt's bookshop at the corner of 86 Fleet Street

and St. Bride's Lane

(Payne's Illustrated London, 1846-1847)

Became

Tilt & Bogue from 1841-3, then David Bogue to 1856. Massey had his

Ballad of Babe

Christabel, War Waits, and

Craigcrook Castle published

there.

Douglas Jerrold's review appeared the following day in

Lloyd's Weekly, referring to 'Babe Christabel' as wholly a thing of

beauty.[3] Walter Savage Landor's comments in a

review letter to the Morning Advertiser mentioned some faulty

metre and the use of substantives as verbs (e.g. 'rainbowed'), but

considered, together with other praise, that 'Massey has given us

thoughts and expressions which remind us of Shakespeare in the best of

his sonnets.' [4] Favourable reviews in most of

the main newspapers and journals and especially by these three

influential literary personages gave a major impetus to sales. A

second edition was produced in March, following which the third was

brought out in June (published in America as

Poems and Ballads), the

fourth in November and the fifth the following February, 1855.

Although selling five thousand copies, the author's final proceeds

amounted to only fifty pounds, the book having to be re-set for each

edition.

But amid the praise, there was one non-committal review and

one that was distinctly adverse. The Westminster Review

wished that Massey would subject himself to a rigorous course of study

and self-culture, before venturing into print again.[5]

However, G. H. Lewes, in the Leader, went further by referring to

‘Admiration pushed to absurdity by the Athenæum’, declaring that:

Gerald Massey has a prodigal command of words, a faculty of poetic

expression, and a certain spontaneity of song, which may hereafter

develop into poetry worthy to be called by the name. He wants some

of the characteristic qualities of a poet — taste and good sense, for

example …[6]

The following week a more caustic extension was added:

Our readers must have been somewhat amazed — as we ourselves were —

last week by the chaotic article on Modern Poets, wherein, among

other incongruities, we were made to praise, with all the emphasis of

italics, some of Gerald Massey's lines emphasised for special

disapprobation … By an accident at the printer's … we had our proof

‘shorn of its fair proportions’ … after quoting liberally and

approvingly specimens of the really good writing in Gerald Massey's

volume, we had, in all fairness, to point out some of the defects; the

passage in which this was done was dropped out by accident, and we now

restore it from a copy of our proof … [7]

Lewes complained and gave examples of ‘fantastic tricks

played with the English Language’, and of ‘the tawdry splendour of fine

phrases’. He quoted one passage which contained ‘vices and

affectations’, which was marked by Massey's liking for contracted words

at that time. ‘Heaven'd’, ‘region'd’, ‘jewell'd’ and ‘swirl'd’,

may have been influenced by Landor's enthusiasm for the fidelity of

spoken sound.[8] Lewes concluded his censure

with:

The passage thus restored may explain the verdict which on summing up

we had to pronounce upon the writer, but which must have seemed to the

reader unjustified by the specimens given, the more so as we appeared to

praise the affectations no less than the beauties. (N.B. Since the

foregoing was in type we have received a letter from Mr. Massey, which

proves — if proof were needed — that the want of good sense and taste we

noticed in his poems extends to his letters.)

The letter Lewes referred to was mentioned in a communication

from George Eliot to Sara Hennell, written on the 9th March:

Mr. Lewes has just come in and put into my hands the enclosed letter

from Gerald Massey, which shew Mr. Bray.[9] Be

it noted, that the 'letter' G. Massey refers to contained the question

when was Mr. L. going to review G.M.'s book, as he (G.M.) meant to

advertise in the Leader. Also, that Mr. Lewes has been very

kind to Gerald Massey as an author …[10]

One may speculate that if Massey had not written so

impetuously, the review might have continued in moderately critical

vein, without the more caustic comments presented the following week.

A few days later, on 15 March, George Eliot wrote in a letter to Charles

Bray, ‘… I thought it right to let you know the worst side of Gerald

Massey,[11] for his sake as well as yours, for

Athenæums and Savage Landors can only lead to perdition.

Otherwise I should be sorry to expose a ‘fellow sinner.’[12]

Charles Bray had met previously with the Masseys at his home in St.

James', in January 1853. In his autobiography he mentions:

We had Mr & Mrs Gerald Massey staying with us. She exhibited in

public professing to be able to read without her eyes. Her eyes

were carefully tied over, or you were allowed to put your hands over her

face, but I noticed that she could not read until the bandage was

considerably displaced, and she was obliged to go to the light, and if

when you held her eyes, you did it effectually, she always complained

that you hurt her till you gave her more space. My opinion in this

case was that there was no more than an exaltation of the natural sense

of sight, which enabled her to see under conditions which she could not

do in her ordinary natural state.[13]

W. E. Adams also mentions a

case of mesmerism and blindfold reading which he saw probably in the

early 1850s. A girl of about his age had her eyes held by Adams

while he produced a book from his pocket which she had never seen.

At a random page she was able to read well, though Adams was quite sure

that she could not possibly see at all.[14]

It has been attributed by various sources that Gerald Massey

was the 'natural' for George Eliot's Felix Holt, the Radical.

This was presented in J. Churton Collins' Studies in Poetry and

Criticism, 1905, in Sir Sidney Lee's portrait of Massey in the

Dictionary of National Biography, 1912, and in later publications.

The earliest reference I can trace is in the American Banner of Light

of 1 December 1883. It states, ‘Friends of Marian Evans (George

Eliot) have heard her say that she had the character and career of

Massey in mind when she portrayed her Felix Holt, the Radical.’

Alfred Miles' Poets and Poetry of the Century, 1897, then repeats

the statement. Unfortunately no source is given for any of this

information, and it is difficult to attribute to Massey either the

physical characteristics of Felix Holt, with his mild radicalism, and

with only slight interest in political causes.

Holyoake defined Felix Holt as a positivist,

and one who fulfilled George Eliot's idea as to the radical which ought

to be.[15] It is known that Eliot studied

various works preparatory to writing Felix Holt, which probably included

Samuel Bamford's

Passages in the life of a

Radical, 1844, as well as using for her portrayals

characteristics of persons she met while staying at Chapman's house.

Although she probably met Massey casually at that time, it is unlikely

that they had any form of acquaintanceship, despite Eliot in 1868 asking

her publisher to send Massey a copy of her Spanish Gypsy.

Gordon Haight is unable to explain her reason for this, and there are

none of Massey's books listed in the Eliot-Lewes library catalogue.[16]

At that time Massey was secretary to the Society of the

Friends of Italy. Formed to promote more popular sympathy in England and

to influence foreign policy by propaganda towards its democratic cause

as promoted by Mazzini, the society had many persons of literary

influence on its committee. Douglas Jerrold, Walter Savage Landor, W. J.

Linton, George Jacob Holyoake and G. H. Lewes were active supporters,

which helped to make Massey's name more widely known.[17]

Massey sent copies of his book to friends and literary

persons, including Louis Kossuth, Thomas Carlyle, John Ruskin and Alfred

Tennyson. This was a common practice among new authors, who were

able to edit any favourable response for inclusion in later editions or

future works. Kossuth commented, ‘Thanks, many thanks for your

gift, which I value very much indeed. It will do good to my

chilled heart, to warm at the fire of your genius …’[18]

The cynical Thomas Carlyle wrote to thank him, and added:

I wish I could do anything to help towards maturity and real

usefulness such a talent as yours … it is to your own truthfulness …

piety and loyalty of mind, that we must look for a solution of that

problem; help is not elsewhere,—else—in various forms, is hindrance

mainly!

I have not anything to say on these sorrowful times through which we are

now passing. To my mind the greatest fountain of them all is

(little as we yet suspect it) precisely excess of ‘saying’ and talking

and palavering,—which the English Nation, for a great while past, has

grown to consider as the chief function of man, and the substitute for

silent hard work in all kinds. I believe the cure of

Balaclava,—and of the universal ‘Balaclava’, which that small Crimean

one is but a symbol of,—lies far beyond the dominion of speech: at any

rate my sad ominous thoughts upon it are better to be kept silent than

spoken, if they were even speakable …19

Ruskin respected Massey's genius, but thought he was ‘too hot

a socialist’.[20] Tennyson referred to Massey's

‘captivating volume’, and although ‘you make our good old English tongue

crack & sweat for it occasionally . . . Time will chasten all that.’[21]

The author and journalist Eliza Linton received a copy, and

wrote an enthusiastic acknowledgement referring also to Landor's

continued interest in Massey following his earlier review in the

Morning Advertiser:

I was with dear Mr. Landor not long ago, and you have quite a warm

niche in that brave noble heart of his. He seems to have a

fatherly love for you, and to be proud of your success … I wasted

not one but many tears over the sweet Babe Christabel … I could

scarcely have believed that a man could have written it … If you

have been praised by the Athenæum, you have muzzled the great Cerberus

of all, have you not? … Why has the Leader flown at your throat?

I thought you were a great pet of theirs—for I have heard you spoken of

by me of them at least very affectionately and I was surprised at the

onslaught, and pained too. I hope Mrs. Massey is better, and that

all will be bright and golden with you …[22]

The following letter was written by Massey to Samuel Smiles,

former editor of the Leeds Times, whose article in Eliza

Cooke's Journal encouraged Massey to continue as a ‘people's poet’

following the publication of Voices of

Freedom. Smiles at that time was contemplating commencing

a newspaper in London, but later decided against the idea.

28, Henrietta St.,

Brunswick Square.

My dear Sir,

I have just sent off the small parcel of my books including one in Cloth

which I hope you will accept from me. The Review in the

Athenæum has given a strong impetus to the sale, but I shall not be

able to take advantage of the tide of success for want of means to

advertise. I was somewhat surprised to hear what you had in

contemplation. The establishment of a Cheap Newspaper is a

formidable affair. I had a taste of that some time ago. A

friend of mine bought O'Connor's Star and started the Star of

Freedom of which I was one of the Editors. He spent 700 or 800£

and it failed.[23] To be sure, there

were many reasons for the failure. It was damned already in public

opinion, and the old partisans had dwindled down to a thousand

subscribers. At the same time Ernest Jones started his Paper and

we were beaten, as we considered it better to give up than to exist on

such terms as he did. And then again, Harney is used up and worn

out; he never was anything more than one of the barnacles that stuck to

O'Connor.[24] I wrote the reviews and

most of the leading articles in addition to compiling a portion of the

news. I still think there is room for a paper if it could be made

well known, and I should like to have a hand in the undertaking. I

suppose I shall drift into Journalism like others, by force of

circumstances; very few persons I think would do it from choice.

Just now I am doing nothing saving a weekly letter to the New York

Tribune, and am greatly in want of something. I hope if you

should come to London to start a paper, you will not complete your

arrangements without remembering me. I have not been at Chapman's

for some time past. I found my engagement there only a mere stop

gap. I must either get something soon or emigrate, for we have

spent the last 2 years in miserable plight.

I am dear Sir,

Yours truly,

Gerald Massey.[25]

Chapman had moved from the Strand to Blandford Square in May,

and this was probably when Massey left the firm.

The third edition of Babe Christabel published in April

contained a preface in which Massey explained why he had included his

political pieces, for which he had been considerably censured.

Although many people still held those views which he had so forcibly

expressed, his opinions had changed to a less radical though still

strongly socialistic direction. At the time those rebellious

feelings were quite natural, and were his deliverance from what he

termed ‘a fatal slough’:

For the slave, degradation and moral death are certain; but for the

rebel there is always a chance of becoming conqueror; and the force to

resist is far better than the faculty to succumb … My experience tells

me that Poverty is inimical to the development of Humanity's noblest

attributes. Poverty is a never ceasing struggle for the means of

living, and it makes one hard and selfish. To be sure, noble lives

have been wrought out in the sternest poverty. But they were so in

spite of their poverty, not because of it …

The fourth edition of Babe Christabel (1855) had one

long and quite perceptive review, which noted Massey's originality of

imagery and description resolving themselves into epithets of

colour—unusual in a lyrical poet. Certain lines suggestive of

plagiarism were mentioned, but the good-hearted reviewer thought they

might be unconscious reminiscences of other poets or, used openly as

common property, due to their intrinsic excellence. But

disintegration of metre was condemned, and it was hoped that the author

would never again attempt blank verse, the reviewer preferring to

‘listen to Mother Hubbard's dog playing on the fiddle’.[26]

Because of Massey's immediate popularity and his biographical

sketch, John Blackwood of Blackwood's Magazine had approached him

regarding the possibility of writing about his personal experiences

within a socio-political framework. Massey replied, asking for

further suggestions. Unfortunately for period history, this

autobiography was later commenced but never completed:

28 Henrietta St.,

Brunswick Sq.,

London.

Dear Sir,

I pray you accept my best thanks for your very kind note to me, and for

the friendly suggestion it contained. I have long had thoughts of

attempting such a work as you mention but have distrusted my limited

experience and my powers of transmuting that experience into a Book.

Again, I have been somewhat deterred by ‘Alton Locke’ which contained a

great deal of my experience, admirably rendered. So much so that I

should fear the charge of plagiarism were I to claim my own. I

should certainly have an advantage over Mr. Kingsley in having lived my

life, whereas he only sympathised with it. I have had a little

experience in writing prose, but, only in the shape of Newspaper

Articles. As regards my present opinions on Society, Religion, and

Politics—it would just take a Book to work them out in, therefore, I

cannot pretend to give you them in a letter. Suffice it to say

that I have passed thro' various phases and vast changes during the last

few years and I am still striving upwards and caring less for mysteries

as I get nearer to the heart of things.

When I have been thinking of writing a Book I have generally concluded

that it should be an Autobiography—can you give me any advice on this

point? My chief points or heads for my subject would consist of

Childhood among the Poor—life in a Factory—Character among the people

and the effect of Circumstances on its development—Village heroes—the

Calvinists among whom I was brought up—coming to London—Life as Errand

Boy,—as Draper—as Secretary of a Co-operative Association—Lecturer and

Litterateur—Courtship—Marriage—Children—these with my internal

revolutions—passions—mental developments—and especial ‘goes on’ at the

Mill and Manchester Men—and that Beast Reynolds[27]

whose ‘mysteries’ have such a pernicious effect on the ignorant poor and

a dash of ‘Clairvoyance’ of the existence of which I have greater proofs

than most men as my Wife possesses the faculty prominently.

This would be my main material. Think you it would do? I shall be

glad to hear your opinion. I have thought of killing my 'hero' at the

commencement and editing his MSS which would permit me to maintain my

present standpoint in surveying my past. I cannot possibly tell what

should constitute a specimen by which you could judge? And how do

you mean to help me toward publishing it were it to suit you? Will

you be good enough to present the Author of ‘Fermilion’ with a Copy of

my Book which I will send per post? Excuse my troubling you at

this Length and believe me Dear Sir

Yours Respectfully

Gerald Massey.

P.S. I forgot to mention that I should give a version of the Chartist

affair of '48 with some sketches of ‘Patriots’ whom I have met.[28]

The reference to ‘Fermilion’ was a satirical review article

written by William Edmondstoune Aytoun, Professor of Literature at

Edinburgh University, in which he criticised Fermilian: or the

Student of Badajoz. A Spasmodic Tragedy by T. Percy Jones.[29]

This 'T. Percy Jones' was himself, and he had not yet written the book

he was criticising![30] His censure was against

what he termed the ‘Spasmodic School’, poets of which were noted for

extravagant expressions of sentiment and mysticism emphasised in varying

quality of style. This was directed particularly against Sydney

Dobell, whose epic poem Balder. Part the First was the subject of

a favourable review article by Massey.[31]

Aytoun had stated also: ‘When one of our young poetical aspirants, on

the strength of a trashy duodecimo filled with unintelligible ravings,

asserts his claim to be considered as a prophet and teacher, it is

beyond the power of humanity to check the intolerable tickling of the

midriff.’ Massey and some of his friends questioned if this

sentence referred to his first edition of Babe Christabel, as

this was published in duodecimo size. His letter to Aytoun, sent

via Blackwood in 1854 for forwarding read:

Sir,

As one of the Readers of your glorious article—‘Fermilion a Tragedy’—and

as one that enjoyed it with immense gusto, permit me to thank you for

it; and at the same time to mention that some very kind and attentive

friends have construed some of your words into a notice of my Book.

You speak of a ‘trashy duodecimo’ & my own guilty conscience tells me I

have said many foolish things and thereby lends countenance to the

statement of the aforementioned friends. In case it was intended for me,

I beg to ask you to read the preface of my 3rd. Edition, a Copy of

which has been sent to you, and you will see that I do not claim the

title of ‘Prophet & Teacher’. I never said such a thing, never thought

of such a thing. If such words have been spoken of me, I am not to

be responsible for all the foolish things said whether uttered by the

Revd. Gorgeous Gilfillan or the Athenæum.[32]

Excuse me for troubling you, and I trust you will not attribute to me

the object attributed to Apollodorus[33] in

writing to the ‘Great ones in the land’.

I am dear Sir

Respectfully

Yours Gerald Massey[34]

Although there is no record of Massey sending a copy of his

book to Walt Whitman, a note written by him showed that he had received

a copy and made comments:

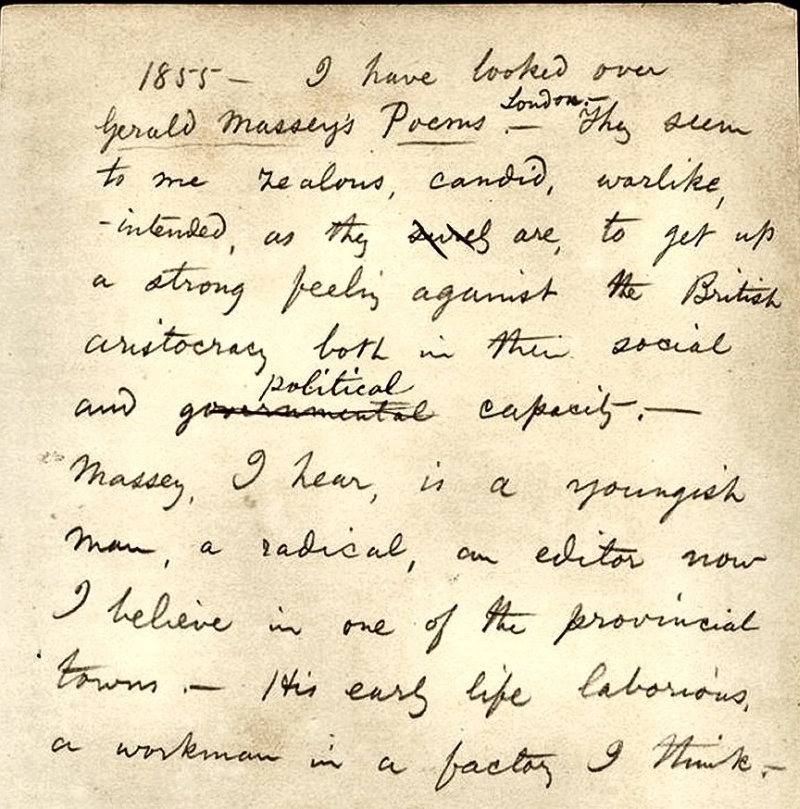

|

"1855

– I have looked over Gerald Massey’s Poems - London.

- They seem to me zealous, candid, warlike, - intended, as

they surely are, to get up a strong feeling against

the British aristocracy both in their social and

governmental political capacity.

―

Massey, I hear, is a youngish man, a radical, an editor now

I believe in one of the provincial towns.

―

His early life laborious, a workman in a factory I think."

Walt Whitman, Note on Gerald Massey, 1855,Trent Collection

of Whitmaniana, David. M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript

Library, Duke University. |

|

|

|

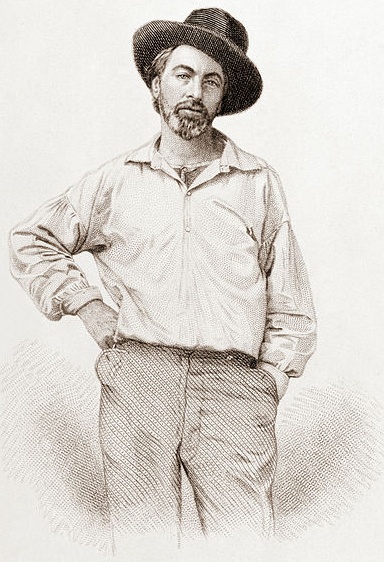

Walt Whitman in 1854.

A steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer

from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. |

The

"provincial town" to which Whitman refers, is Edinburgh.

During Massey’s later

tours of America he had not made contact with Whitman. However, in an

article 'New Englanders and the Old

Home' he made a brief reference to Whitman and to Charles Dickens'

Hon. Elijah Pogram. (Quarterly Review, vol. 115, Jan. 1864,

42-68.) Dickens’ Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit

written in 1843-44 following his visit to America in 1842, had referred

to the Americans as brash, vulgar and boastful. Epithets that caused

considerable irritation in that country.

Following the publication of Babe Christabel, Massey

concentrated on making literary contacts and had little time for

writing, apart from a poem and an article ‘Mazzini

and Italy’ for the Northern Tribune. His wife, Rosina,

was in poor health while expecting their third child, and they made yet

another move, from Brunswick Square to 14, Oak Villas, Oak Village,

Kentish Town. Since his review of Sydney Dobell's Balder he

had continued with friendly communications with this author, who wrote

to him from Edinburgh on 17 August:

|

My dear Massey,

My Wife is I believe about to write a word of sympathy on the subject of

yr Invalide & her expected trouble & I will only say therefore—what,

after all, sums up the whole that can be said—God help her—& you …

[35]

|

Exactly what trouble Rosina was having at that time is not

recorded, but it was probably a depressive precursor of greater health

problems to which the family would be subjected during the following

years. Marian Mertia was born one week later on 24 August 1854.

The fifth revised and enlarged edition of Babe Christabel,

published in February 1855, was dedicated to Lady Marian Alford ‘as a

small memento of respect and gratitude’. Hepworth Dixon, chief

editor of the Athenæum was friendly with Lady Marian Alford,

widowed daughter of the second Marquess of Northampton.[36]

Her son, John William Spencer, was the second Earl Brownlow. Dixon

had mentioned Babe Christabel to them and given them details of

Massey's background together with a summary of the family's present

circumstances. Lady Alford was considerably impressed, also by the

fact that Massey's birthplace was near to Ashridge. This prompted

her patronage, in which she either paid for publication of that edition,

or gave Massey financial assistance. In addition to the

dedication, Massey named his third daughter Marian after her.

Lady Marian Alford, from an oil-painting

(Trustees of the British Museum).

John William Spencer, Earl Brownlow

In Massey's 'In Memoriam'. (British Library copy only).

Not having been able to obtain permanent employment since he

left Chapman, his financial state was becoming quite critical. He

had managed to remain solvent that year, 1855, by contracting some

unsigned biographical sketches for Bogue's Men of the Time, for

which he wrote for personal information to Sydney Dobell (for Alexander

Smith the poet), Louis Blanc, and Ferdinand Freiligrath the German poet

and Communist. Also that same year Bogue published his Crimean war

poems, War Waits, dedicated to

John Bright, the anti-Corn Law campaigner and noted orator against the

Crimean war. Despite Massey referring to these poems as ‘rough and

ready war-rhymes’, the reviews were quite approving. The

Edinburgh News mentioned their 'beauty of expression and imagery',

and wrote in general terms of the author's 'nervous, vivid and

impassioned' style. The Athenæum again praised his

descriptive power: 'After verses so vigorous that it seems to echo the

tramp of horses and the roar of cannon, most of our minor minstrels

would be tame . . .'[37] It then added a shrewd

comment, ‘The charge, the contest, the retreat are vividly drawn by the

writer, who has never seen a squadron in the field.’ Sydney

Dobell, attracted to Massey since the Balder review, wrote to the

Rev. R. Glover:

I enclose you Gerald Massey's ‘War Waits’, and know how heartily you

will respond to their fine flushing enthusiasm. . . If you don't know

his other works yet, by all means lose no time in seeing them, and in

reading his Preface, which contains sentences of prose which Milton

might have written …[38]

Those literary works were financially unrewarding.

However, by March, Massey had obtained the promise of a post as an

editor on the Edinburgh News, due probably to some assistance

from Dobell who may have been the reviewer of War Waits.

Rosina was now expecting their fourth child. Massey wrote to

Harney on the 21 March, whom he had been expecting to meet during the

family's journey to Edinburgh:

It's all up about our coming to Newcastle. I find that we go

straight on to Edinburgh in one night and in less time than it will take

to go to Newcastle. Mrs. Massey is already knocked up and very

poorly and thinks we had better go direct … We shall be in a precious

fix in moving and this plan will obviate the necessity of our all

sleeping in London after the goods are moved and packed up in a ten feet

room …[39]

Just before moving he had time to write to

James Macfarlan, the Glasgow

‘Pedlar-poet’ who had sent him a copy of one of his volumes of poems:

Dear Sir,

I have received your pleasant little Vol and your kind letter.

Many thanks for both. There is one thing in your lines I protest

against; it is, calling Fame ‘'fickle’. Notoriety maybe; but true

Fame is fame for ever. But, Fame—grand lady as she is—can

never be a true Poet's Mistress, he cannot worship her, she is only

hand-maiden to his Beloved.

If you are a Poet, be sure Fame will find it out. There is no need

for haste, the Spring will come, the rose will blow, the Poet will be

recognised for what he is.

I am in expectation of seeing auld Scotland in a few days—I go to

Edinburgh —how far is that from Glasgow?

Macfarlan's friend J. P. Crawford had scribbled on the

letter: ‘Sold to me by Macfarlan for a 6d to Buy drink no doubt’.[40]

The family arrived in Edinburgh at the end of March 1855,

where they stayed in temporary accommodation at 14 Trinity Crescent,

which had been found for them by Dobell:

And first of the [Massey]s, who arrived in Edinburgh eight days ago,

and on Monday entered upon the lodgings we had found for them at

Trinity—where they now seem comfortably settled.

I have seen them every day, and am pleased to the heart to find in him

more even than I allowed myself to expect of beautiful and good ... The

upper part of his face reminds me of Raphael's angels, and I catch

myself dwelling upon him with a kind of optical fondness, as one looks

upon a beautiful picture or a rare colour. And this in spite of a blue

satin waistcoat! and a gold-coloured tie! The second morning I came upon

him early, sans neckerchief or collar, nursing his sickly baby, the grey

wrapper in which he sat, being like the mist to the morning as regards

his wonderful complexion, and it would be difficult to imagine more

marvellous (masculine) beauty …[41]

Massey was not due to take up his post with the Edinburgh

News for another two months, so he busied himself then and later by

writing some

articles for Hogg's Instructor, which also formed the basis for

two of his future lecture subjects. In ‘Thomas

Hood, Poet and Punster’, Hood's ‘Song

of the Shirt’ received honourable mention, continuing Massey's

commitment to the opposition of social injustice at that time. He

referred to it as a ‘piercing cry’ that:

woke up the wealthy and the great from their luxurious beds … that

showed them the human lives they were wearing out - the blood of little

children wrung out to dye their costly crimson … their sisters who

stitched their lives into their work for 4½d. per day … some,

indeed, cursed the voice of the poet that had so rudely broken their

voluptuous dream and they slunk back to their silken pillows. But the

rest stared on, and could not turn away... None but the poor know what

the poor endure. But this song led England to see that there were, in

London alone, 33,500 poor women, working for from 2½d. to 5d. per day

… [42]

|

…O! Men, with Sisters dear!

O! Men with Mothers and Wives!

It is not linen you're wearing out,

But human creatures' lives!

Stitch - stitch - stitch,

In poverty, hunger and dirt,

Sewing at once with a double thread,

A Shroud as well as a Shirt …[43] |

‘The Poetry of Alfred

Tennyson’, an appreciation of Tennyson's Poems, The Princess,

and In Memoriam, was probably the best article he had written on

a living poet up to that time, and was one of the first articles to show

his development of prose style when divorced from political commentary:

It is his colossal calmness, the absence of blind hurry, that is

often mistaken for a want of passionate earnestness … The poetry of

Alfred Tennyson constitutes a world of exceeding loveliness, a world of

peculiar beauty, unique in all literature … When his verse 'trembles and

sparkles as with ecstasy', it is intellectual, and not a dance of the

blood ... After that grand debauch with the fire-waters of Byron, which

we look back upon, how pure, how fresh, and sparkling with health is the

poetry of Tennyson! … We find that the subjectivity of our poetry is

representative of the time and the circumstances that produced it, as

the objective drama of the times of Shakspeare. In Tennyson this

subjectivity has its culmination …

He was pleased with it sufficiently to send a copy to the

Tennysons with a covering letter to Mrs Tennyson, rather imperiously

requesting some personal details of her husband that he could include in

a sketch for Bogue:

Dear Madam,

In my last note I quite forgot to say that Mr. Woolner told me that Mr.

Tennyson had said that if I still persisted in writing the sketch for

the ‘Men of the Time’, he supposed he must give me the Data—or something

to that effect. Pray say that I do persist, and shall be glad to get it

at once. I enclose a Review which I wrote in a paper here. I had no Copy

of Mr. Tennyson's Poems at hand or I might have convicted the young

Gentleman on other counts …

Yours dear Madam

very Respectfully,

Gerald Massey.[44]

Emily replied and, in more gentle tone, commented on the

article:

My dear Sir,

Thank you very much for having sent us your Review. Our Mother and

Aunt were so charmed with it I ordered a copy for each, and may I add I

too also like it extremely. I only remember one thing with which I

cannot quite agree, for I cannot help looking upon my husband as among

the universal poets. He is too human to be merely a subjective

poet and I cannot help thinking if you read his poems now as I hope you

will one day read them in the light of himself, if I may so speak, you

would agree with me. Is not his genius both Idyllic and Lyrical?

the first quite as much as the last; and is not an Idyll a kind of

concrete drama at least in its highest form is it not so—& does not this

imply universality? … I hope Mrs Massey is improving as rapidly as

possible …

Truly yours

Emily Tennyson[45]

Following this letter Tennyson wrote to Massey:

Farringford

Freshwater I.W.

July 11/55.

Dear Mr. Massey,

Will you accept a little volume from me of my own poems? I have

ordered Moxon to forward one to you. My mother now between 70 &

80, one who takes far more interest in the next world than in this, &

not generally given to the reading of literature, was quite delighted

with your paper in Hogg's Instructor.

Believe me

dear Mr Massey

yours very truly

A. Tennyson[46]

The Masseys had now found more permanent accommodation at 12,

Henderson Row, near the Royal Botanic Garden and Edinburgh Academy, but

the first of several tragedies was being enacted. Marian, the

Masseys' ten months old youngest daughter who had been sickly from birth

as mentioned by Dobell, developed enteritis, and died on 19 July.

Massey wrote to Emily Tennyson:

Dear Madam,

Our little darling's gone. At one o'Clock this morning while the

world slept the death-angel dived and snatched, we think blindly, from

this troubled sea of life one of the purest preciousest pearls that were

ever set in the crown of God.

Yours, very heartbrokenly

Gerald Massey.[47]

Dobell mentioned this also in a letter to Dr Samuel Brown: ‘…

You will be glad to know that [Massey] has got a good appointment in

Edinburgh. He is in great grief just now, poor fellow, for the

death of his youngest child…’[48]

This was a severe blow, especially to Rosina for whom it was

the beginning of a decade of depressive ill health. It is not

certain when Rosina had commenced taking alcohol, but she certainly

became addicted to it during this time. Psychologically the shock

must have caused traumatic hysteria with depressive conversion.

She suffered exaggerated physical and mental symptoms which showed

themselves as hyper-expression of feelings that gave episodes of

dramatisation, changeable moods, irritation and fits of temper.

Early in her illness she was queried as having tuberculosis, and later

as being hyperthyroid, but no firm physical diagnosis was recorded.

Although there were to be occasional remissions over the following ten

years, she remained virtually an invalid, with pathological jealousy

causing Massey great problems both in his working and writing life.

An anonymous writer in the New York Mercury gave a generally

inaccurate account of the Masseys, with whom he had stayed on one

occasion. But he did mention Rosina's jealous reactions in the mid

1850's when she thought her husband was receiving approving glances from

attractive young women during his lectures (St

Louis Globe Democrat, 21 October, 1875). To his credit,

when Massey could have sent her on a number of occasions to a mental

hospital, he looked after her with affection and always gave her

support.

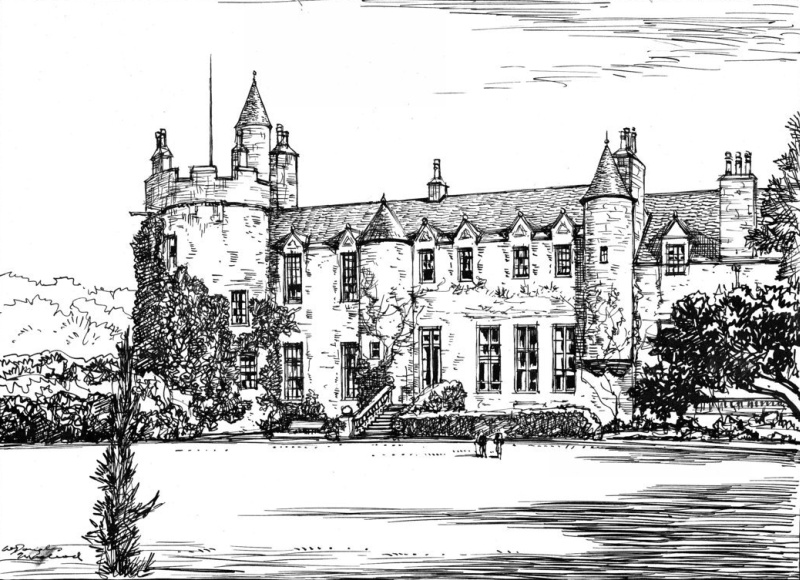

Craigcrook Castle.

During his first year in Edinburgh he came in contact with a

number of literary figures, including the poet Alexander Smith who was

secretary to the University, Professor John Blackie of the University,

John Buckle, historian, and Professor James Simpson, the discoverer of

the anaesthetic properties of chloroform. Simpson also advised

treatment for Massey's wife, without charge. But it was William

Stirling, MP for Perth, referred to as ‘That princely Stirling of Keir’

who befriended Massey with a generosity that was typical of his

practical and sympathetic personality. Stirling owned Craigcrook

Castle, at Keir, some three miles from Edinburgh. Dating from the

14th century and enlarged in the early 1800s, it was originally a large

manor house with a round tower and extensive grounds.[49]

Stirling willingly placed the castle grounds at the family's disposal.

But now Massey was feeling trapped by his job which he found to be

mentally exhausting as well as taking up more of his time than he had

anticipated. Hopes of financial security ended when he was forced

to employ a resident housekeeper to look after Rosina and the children

when he was at work, and he found himself getting poorer by the month.

To give Rosina a change of surroundings he arranged for a short holiday

at the Bridge of Allan, but even this had to be curtailed due to the

illness of one of his children. To add to his problems Rosina was

well into another pregnancy, complaining that she found Edinburgh too

cold and wanted to return south. All those factors so restricted

his time that he could undertake only a small amount of extra writing.

His next book of poems, Craigcrook

Castle, for which he over-optimistically expected to receive £200 if

it sold well, was consequently delayed. That extended venture into

blank verse included ‘The

Mother's Idol Broken’, an elegy on the death of Marian with a theme

similar to ‘Babe

Christabel’. However, Massey's depressing personal experience

increased his fault of excessive sentiment almost to the point of

morbidity which, by today's standards, makes the poem uncomfortable

reading:

|

…

She only caught three words of human speech:

One for her Mother, one for me, and one

She crowed with, for the fields, and open heaven.

That last she sighed with a sweet farewell pathos

A minute ere she left the house of life,

To come for kisses never any more …

Ere the soul loosed from its last ledge of life,

Her little face peered round with anxious eyes,

Then, seeing all the old faces, dropt content...

Within a mile of Edinburgh Town

We laid our little darling down;

Our first seed in God's acre sown! …

Today, when winds of winter blow,

And Nature sits in dream of snow,

With Ugolino-look of woe:

Wife from the window came to me,

Now leaves were fallen she could see

The little wee grave thro' shred elm-tree …

Think of our babe that will never wake,

And hold your own till fond hearts ache,

Sweet souls, for little Marian's sake … |

At that time the family was very fortunate in having made the

acquaintance of William Stirling, who generously loaned them money on

account to pay for the services of their housekeeper, and gave them

gifts of game from his estate.

Their next child, Sidney William Dobell, named after the

poet, was born on 7 May 1856 with a fate similar to Marian's, and some

four months later Dobell had again to write of bad news: ‘… Death

is again going up poor Massey's long stair, I fear; my little namesake

was nearly dying when I saw him last.’[50]

Little Sidney died of peritonitis on 10 September, placing another grave

in Warriston Cemetery and causing Rosina more mental trauma, especially

as the cemetery could be seen from the family's rooms.

Warriston Cemetery (Ref. No 147, Section N, Sub-Section

N2, Inner Row 04).

Photos: Chris Halliday.

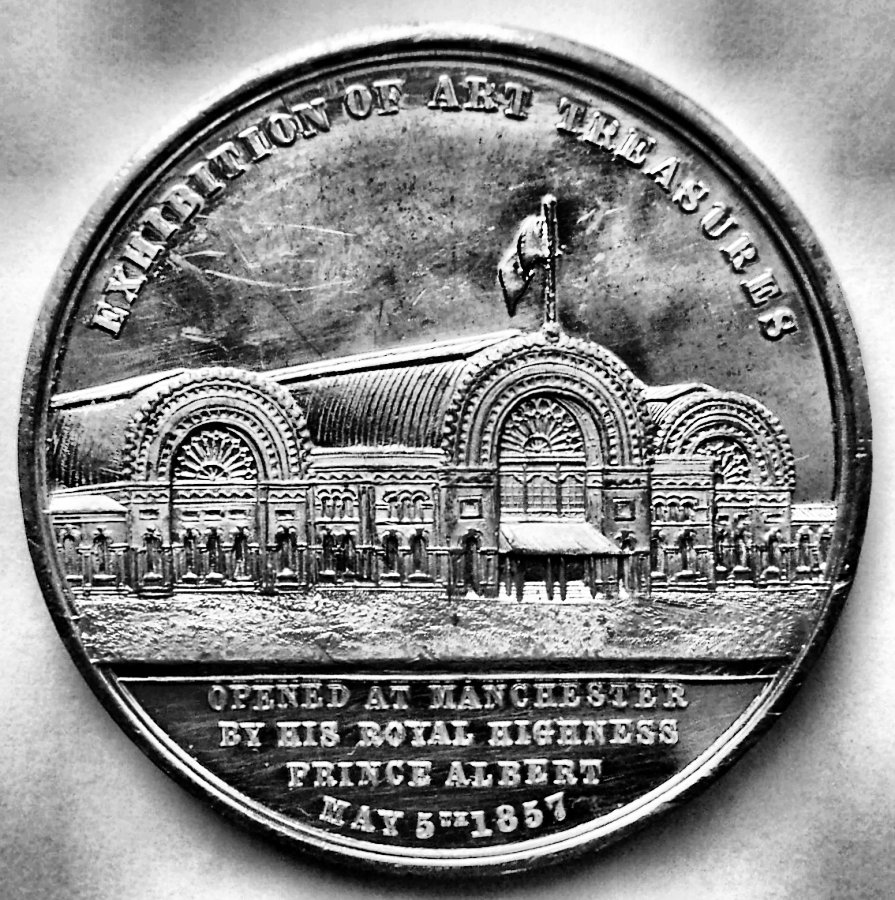

Some

additional unsigned writing was contracted for Hugh Miller's newspaper

the Witness, for which there is positive identification of a

series of eleven articles from May to September 1857, covering the

Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition.[51] Breaks

in the series were made in order to give more coverage to the Crimean

war. As an example of Massey's descriptive prose writing it is

among his best works, apart from his common fault of over extended

sentences. Yet even that has a subjective illustrative power in

its own right, reminiscent of, but antithetical to, Dickens' colourful

objective sketches. During the train journey to Manchester he

noted:

One whiff of Spring fragrance and we are whirled into Preston.

O, town of the multitude of tall chimneys, that reek continually in the

face of heaven! it is pleasant to behold thee receiving the nightly

baptism of God's cleansing air;—to see the arms of old grey space flung

around those lofty soot-fountains, and choking them, as it were, for a

short time, that have daily choked the air for so long;—to feel the hand

of silence laid on the perturbed spirit of machinery, while it lies like

a tired thing at rest. Gladly also do we again shoot out into the

country, away from those towering stacks and clanging mills that will be

all alive two hours hence, and clamouring at heaven, like so many

frustrated Babels, that all end in smoke; for we get the prettiest of

peeps of little nooks, where the lilac is all one mass of starry purple

bloom, and the fruit trees look like a winged shower of white. We

take in a good long breath of the sweet country air, as a diver does

before he makes his plunge, and, lo! we are in Manchester … [52]

Medal

showing the front of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition Building.

The Nave of the Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition

Building

(Illustrated Times, 11 June 1857).

The large exhibition provided a sampling of all aspects of

art, with paintings particularly well represented, hanging in long

galleries. Most of Massey's articles were descriptions of these

works, and he wrote colourful vignettes of the painters, and stories of

the subjects that would have supplemented the published brochures to

advantage:

Shapes of grace have started from their marble immurement at the

sculptor's wakening touch, and taken their stand on pedestals by the way

… rich tapestries and fairy traceries … fruit dishes, starred and bossed

with jewels of price … common wood, carved with such art, you might

fancy it budded into life in that shape, and put forth those tendrils

and leaves that are only waiting for the juices of spring to flow …[53]

In spite of his dislike of newspaper work, it had developed

his prose writing away from the reflected, often excessively emotional,

subjectivism that remained a feature in his verse. There was

greater control and refinement of composition, with increasing critical

discernment. Without that experience, favourable literary

appreciation for his main prose works soon to follow would have been

considerably weakened.

|