|

[Back

to Chapter 5]

CHAPTER SIX

SPIRITUALISM AND THE NEW WORLD

[1870 - 1874] |

|

To act according to conscience and speak according

to knowledge, never ceasing to consider what we can do for the service of others, is the one duty which

a future life, if it comes, will not contradict.

(George Jacob Holyoake) |

|

|

Since Massey's remarriage in 1868, three

daughters had been born. Hesper Carmina Emilia on 9 May 1869,

Maybyrn Adelaide on 30 March 1870, and Evelyn on 2 February 1871.

Financially more solvent at that time, he was able to employ a nursemaid

as well as a housekeeper to ensure satisfactory provision for the family

while he was away on his lecture tours. These were now extended to

the summer, as well as continuing through the winter months. On

Friday, 28 July 1871, a conversazione was held at St. George's Hall,

Langham Place, to mark a farewell meeting and presentation in honour of

a valiant crusader and Spiritualist speaker, Mrs Emma Hardinge Britten,

who was leaving for a lecture tour in America. The hall, seating

some 900, was nearly filled, with Gerald Massey known as an experienced

lecturer and now an avowed Spiritualist, taking the chair.

Representing the Spiritualists of England, Massey gave a general

appreciative address on their behalf.[1] In his

own address, Massey referred to Spiritualistic phenomena in general,

comparing the effects of orthodox belief with those of the

Spiritualistic philosophy:

I find the mass of so-called religious people don't want to believe

in the spirit-world save in the abstract or otherwise than as an article

of their creed. They accept a sort of belief in it, on authority—a

grim necessity; it's best to believe, in case it does exist after all;

but they give the lie to that belief, in their lives, and in presence of

such facts as we place before them. Our orthodox spiritual

teachers have arrested and made permanent the passing figure, and

permitted the eternal essence of the meaning to escape. They have

deified the symbol on earth instead of the God in heaven. They have

taken hold of Christ by the dead hand and lost sight of the living Lord

… [2]

The address was enthusiastically received, and in a letter

sent the following day from Marie Sinclair, the Countess de Pomar who

was shortly to become Countess of Caithness, she hoped that the address

would receive eventual publication. The following year Massey did

expand the address into a small book Concerning Spiritualism,

published by James Burns. Burns was a well known Spiritualist

lecturer and publisher, based at 1 Wellington Road, Camberwell before he

moved to his Spiritual Institution at 15 Southampton Row, in 1869.

He advertised phrenological classes, held receptions every Monday

evening, and published the weekly Medium and Daybreak and monthly

Human Nature. A large ‘Progressive Library’ was available

on the premises for the loan of books by subscription to members.

Massey became a frequent visitor to the establishment, where his 'breezy

personality' diffused an atmosphere of energy whenever he called.

Concerning Spiritualism is stated in some biographical references

as having been withdrawn by the author. Although not withdrawn as

a publication, many of the opinions to which Massey then subscribed were

to change radically during the following ten to twelve years and he did

not have it reprinted. (See fn 8.) In the book he admitted having

read very little Spiritualistic literature, save in the first instance

William White's Swedenborg: His Life and Writings. His

conclusions were based purely on personal experience and were, so far as

he knew, original. Some Swedenborgian metaphysical ideas are

inherent in the book, particularly the idea that all force, including

life, is of spiritual origin. But Massey was attempting to

separate orthodox doctrinal theology from what he regarded as a reality

that, he said, resulted deductively from observable Spiritualistic

phenomena. While accepting Darwin's theory of man's origin and

believing that we have ascended physically from lower forms of creation,

he considered the cause to be spiritual, and endeavoured to make this

more easily understood by what he termed ‘plain speaking’. The

'here and now' of eternity, which he stressed so often in his lectures,

indicated his belief in the individual continuity of spiritual life:

The other world is something to be believed in so long as it is afar

off, but to be doubted and rejected if it chance to draw near. It is

distance that lends enchantment to their view. Many good people appear

to think that we must wait until death before we can get at the

spirit-world; as though we could only touch bottom by grave-digging! We

are in spirit-world from birth, not merely after death; we are immortal

now if ever, and must be dwellers in eternity, which is Here and Now,

however we close our eyes to it, and be self-shut out of it … Our lost

darlings have not gone off from us like an escape of gas, as so many

seem to imagine … Here are our clergy asserting Sunday after Sunday, in

the name of God, any number of things which any number of listeners do

not believe, only they have heard them repeated till past all power of

impinging - things which they themselves do not believe if they ever

come to question their own souls. . . Spiritualism will also destroy

that belief in the eternity of punishment …

There had been considerable appreciation for Massey's address

given at the conversazione the previous year. Consequently he was

invited to present a series of four lectures on Spiritualism at St.

George's Hall, Langham Place, commencing in May, 1872 (each being

reported in Medium & Daybreak).

The committee of invitation included Sir William Dunbar, Sir Charles

Isham, Cromwell Varley FRS, William Crookes FRS, H. D. Jencken,

Barrister, George Harris, Vice-President of the Anthropological

Institute, Thomas Shorter, and William White the Swedenborg biographer.

Tennyson was sent details, but was unable to attend, writing to Massey

on the 7 May:

My dear Mr Massey

If I were in or near London I would come & hear you myself; for I have

read your little book more than once & got others to read it, and should

like doubtless to hear your viva vox on the same topic … [3]

Massey's first lecture on 12 May was on the facts of his own

experiences together with various theories of the alleged phenomena.[4]

The two hour lecture was well received by a full hall, among whom was

Professor Blackie, who briefly mentioned the lecture in a letter:

In the (Sunday) afternoon we heard Gerald Massey give the first of a

series of lectures on Spiritualism, to a crowded audience, full of the

most strange, odd, and inexplicable stories about the spirits that made

revelations to that Fairy called his wife … [5]

Following on his personal experiences of which he gave

accounts during the lecture, Massey compared the theories of Serjeant

Cox's ‘psychic force’ with Dr William Carpenter's ‘unconscious

cerebration’, or unconscious muscular movement. This latter had

been promulgated in Carpenter's article on electrobiology and mesmerism,

and Massey could accept neither of those theories.[6]

It had not been discovered at that time that some apparently paranormal

physical phenomena unconnected with muscular action could be produced

solely by the individual, or groups of individuals. The daily

press kept silent on the lecture, apart from the Globe which

considered it facetiously amusing, and ended by saying:

Trashy ghost stories might have been all very well when Mr Massey

wielded the pitchfork; but to hear them soberly delivered in terse,

vigorous English, and with the racy, humorous good sense which is

characteristic of his style, suggests the idea of a man of real

intellectual power degenerated into a hopeless craze.[7]

Massey's second lecture on 19 May was lengthily titled

‘Concerning a Spirit World revealed to the Natural World by means of

Objective Manifestations; with a New Theory of the Tree of Knowledge of

Good and Evil’. He commenced by mentioning the two theories of

man's origin; one assumed that he was struck off perfect from the mint

of creation, stamped with the image of God, the other that he was

developed from the animal kingdom, and is gradually approximating the

divine image. Early man first became aware of a spiritual world

and of man's fate after death by visible phenomenal demonstration in the

form of spiritual apparitions. He then went on to examine forms of

worship showing that they were the result of objective experiences, not

of metaphysical deductions.

The third lecture on 26 May indicated the direction his views

were taking him. In ‘The Birth, Life, Miracles, and Character of Jesus

Christ Re-viewed from a Fresh Standpoint’, he said that the only

position theologians were able to maintain was in trying to keep the

rest of the world as ignorant as themselves. They still threatened

us with everlasting punishment if we did not believe. Had they

been present when Jesus performed his miracles, they would not have

believed in them any more than they believe in spiritual manifestations

today. Christ's Messiahship, miracles, resurrection and divinity

were mentioned in the lecture as being necessary to awaken humanity to

the sense of immortal welfare, not to create immortal life in man, since

it was already there.

His concluding lecture the following Sunday to a moderately

large audience, was ‘Christianity as hitherto interpreted; a Second

Advent in Spiritualism’, in which he compared Spiritualistic beliefs

with those of orthodox Christianity. He considered that the

Christian world had cultivated the greatest fear of death, which to it

was like taking a step in the dark. But with the assurance of

immortality being a fact, the Spiritualist could walk through the valley

of the shadow of death, and find that death was but a shadow of life's

presence. He could ask ‘Is this the bugbear that has frightened so

many?’ For that series of lectures Massey received £25. 4s. (Medium

& Daybreak, 7 June, 1872).

Now almost completely dependent on lecturing for his living,

he again issued a prospectus for the forthcoming winter season.

These nineteen lectures were the same as for the previous winter of

1871-72, including Pre-Raphaelitism, Tennyson, Burns, Shakespeare,

Swedenborg, Lamb and Thomas Hood. But he now included a special

course of four, the lectures he had delivered recently, concerned more

specifically with Spiritualism. Prior to the London lectures he

had many connections with Young Men's Christian Associations. They

considered his poetry particularly pious, and had been booking him on a

regular basis for some seventy to eighty lectures during the winter

months. Following his avowal of Spiritualism he had offers of only

seven. Some fifteen years after publication of Concerning

Spiritualism, his researches into Christian origins led him to admit

that apart from his Spiritualistic concepts, the position which he had

held at that time based partly on orthodox theological doctrine, had

been incorrect.[8] That statement, had it been

made earlier, would certainly have severed completely all his links with

the YMCA's.

The amount of interest engendered in Spiritualism in

the 1860s led to the whole subject being investigated by the secular

London Dialectical Society, based then at 1, Adam Street, Adelphi, in

the Strand. This society was very prestigious and included Charles

Bradlaugh among its founder members. Its prospectus, issued around

1867, asserted that:

Freedom of speech and thought are, not less than personal freedom,

the natural birthright of all mankind. To refrain from uttering

opinions because they are unpopular, betokens a certain amount of mental

cowardice … In the London Dialectical Society, however, not only will no

person suffer obloquy on account of any opinion he may entertain or

express, but he will be encouraged to lay before his fellow-members the

fullest exposition of his views …

It carried on the tradition of the London Debating Society,

commenced in 1834 by John Stuart Mill, the lectures being notable for

cross examination of the speakers, allowed from the floor. Such

subjects as ‘Cremation’, ‘Chastity’, and ‘Marriage’ were debated, many

of the lecturers, like Annie Besant and George Bernard Shaw, gaining

fame over the years.[9] In January 1869 the

society resolved to appoint a committee under the presidency of Sir John

Lubbock MP, to investigate the phenomena alleged to be Spiritual

manifestations, and to report thereon. They did not make it their

brief to report on Spiritualism as a creed or philosophy. The

opinions of the press prior to the investigation were highly negative:

that no such phenomena as alleged occurred at all; that the alleged

phenomena were the result of imposture or delusion or both; that the

phenomena that occurred were explicable by natural causes, and that

Spiritualists as a body shrank from any investigation.[10]

The thirty-six member committee commenced by inviting oral

and written evidence, then divided themselves into six sub-committees,

meeting at 4, Fitzroy Square, to investigate experimentally.

Numerous séances were held, with and without well-known mediums, many at

private residences of committee members to preclude the possibility of

pre-arranged mechanisms or contrivances. Some were held with D. D.

Home in the presence of Lord Lindsay and Lord Adare, together with

society committee members. Oral evidence was given by thirty-three

people, including Lord Northwick, Cromwell Varley, Thomas Shorter, Lord

Lindsay and D. D. Home, with written evidence supplied by some thirty

persons, including Lord Lytton, Professor Tyndall, Alfred Russel Wallace

and Camille Flammarion. A letter from Dr William Carpenter dated

December 24 1869 included a long extract from his theory of ‘Unconscious

Cerebration.’ Gerald Massey's affidavit for the Lyon v. Home suit

was cited, together with a testimony of Professor De Morgan.

Professor Huxley was invited to serve, but declined, saying that he had

no time, and no interest in the subject. Phenomena experienced by

the subcommittees included varied sounds apparently proceeding from

furniture, floors and walls, movement of heavy bodies without mechanical

contrivance or adequate exertion of muscular force, and answers and

communications regarding questions asked at the time. Other

phenomena given in evidence recorded levitation, the appearance of hands

and human figures, red hot coals applied to hands and head without pain

or scorching, and trance-speaking.

After two years, the society produced its report in July,

1870. They commented that they were almost wholly unsuccessful in

obtaining evidence from those who attributed the phenomena to fraud or

delusion. Summarising the reports of the sub-committees, they

concluded that the testimony of witnesses was supported by reports of

the sub-committees, and there was absence of proof of imposture or

delusion as regards a large portion of the phenomena. The

exceptional character of the phenomena was noted, as was the world-wide

influence of a belief in supernatural origin, for which no philosophical

explanation had been determined. They considered it necessary

therefore, to state their conviction that the subject was worthy of more

serious attention and careful investigation than it had hitherto

received.[11]

Following publication of the report, the press were varied in

their opinion. Some made misquotations and misrepresentation,

while others had a more courteous and tempered response than before the

report was issued. Even the American Catholic World went so

far as to agree with the three hypotheses existing to account for the

phenomena: unconscious cerebration expressing itself in unconscious

muscular action, psychic force, and spirits. But concerning the

latter, it said, account had to be taken into the church notion of magic

and direct diabolical interference.

Distribution of the report, which contained press opinions,

ensured that the inclusion of the subject in Massey's lecture tours

would at least receive a more enquiring response. Since 1858 he

had been considering the possibility of an American tour, mentioning

this at the time to James Fields, the senior partner of Ticknor and

Fields of Boston who had published his poetical works, but this had been

negated by his wife's illness. Now, he began again to make more

definite plans in this direction while continuing his tours throughout

England and Scotland. That winter he visited Durham, Barnard

Castle, Bishop Auckland, Darlington and Halifax. Returning to

Barnard Castle for a further two lectures on his Spiritualistic theme,

an attempt was made to get him out of town before completing his

engagement. However, due to an enthusiastic circle of friends, the

pastor of the Free Christian Church, Joseph Lee, let him deliver his

lecture from the pulpit:

“On the 6th and 7th instant Mr. Gerald Massey delivered two lectures,

on Spiritualism to large and intelligent audiences at Barnard Castle;

the subject was handled in a masterly style, orthodox theology was

fought on its own ground, several ministers were there to hear it, and

such was the artillery brought against the old creeds that the most

independent thinkers declare that its foundations are terribly shaken;

raving priests and foaming bigots raised such an uproar with the old

cry, "the church is in danger;" and an attempt was made to get Mr.

Massey out of the town before completing his engagement. This his

friends would not submit to, but the Free Christian Church was placed at

his service, and a large audience listened to him with great interest

for one hour and forty minutes. The subject was, "The Birth, Life,

and Death of Jesus," and again old orthodoxy fell in for a most fearful

lashing; he set forth Jesus as an ever-living and spiritual presence

which has given encouragement to free and independent thinkers. A

few séances have been held, and striking manifestations realised.

I would recommend all who wish to study this important subject to listen

to Mr. Massey's lecture on the person of Jesus from a new standpoint.”

(Medium and Daybreak

22 Nov. 1872.)

The Reverend H. Kendall of Darlington commented despairingly

that the churches seemed to be in low water at present, referring to

Massey as a certain individual who had been lecturing last week in

Darlington and other places on Spiritualism, and he was amused at that

gentleman's curious statements and beliefs.[12]

Due to inclement weather and the proximity to Christmas, his Halifax

lecture was poorly attended. Additionally, the Spiritualists in

that town were divided in opinion, and even got up a Sunday opposition

meeting.[13]

In Middlesbrough his lecture for the Philosophical Society

was by contrast well attended, and received with repeated salvos of

applause. The local Gazette gave a favourable report,

together with a leader giving fair comment on Spiritualism.

Strangely, as Massey was at that time a supporter of a number of

Swedenborg's ideas that were presented in his Arcana Coelestia,

it was reported that the Swedenborgians were arranging for a lecturer to

visit Middlesbrough to offset Mr Massey's teachings.[14]

But Spiritualism was the sole reason for their refusal to accept

Massey's ideas. They considered that the spiritual experiences of

Swedenborg between 1845-1849 might seem to countenance the séances of

mediums. A Swedenborgian later confirmed this view, stating that

Swedenborg's ‘admission into the spiritual world, however, is no

justification of admission by self-seeking, and the dangers of so doing

Swedenborg points out. Therefore the New Church is opposed to

Modern Spiritualism.’[15]

The fairly sedate internal progress of Spiritualism received

rather unwelcome news in January 1872 which, fortunately for them,

remained mostly confined within its own ranks. Mrs Victoria

Woodhull, a slim fiery American Spiritualist with firm religious

visionary beliefs, had stated her open support for free love and the

abolition of the marriage system. Resolute in her opinions of

female social reform, she had also strong political aspirations which

gained her support from, among others, the National Women's Suffrage

Association. A correspondent to the Medium and Daybreak

suggested that free love had a Biblical origin, when the Lord appointed

Gabriel to infringe upon the marital rights of Joseph, and render the

first-born of Mary an adulterous progeny. Predictably, this

assertion produced a lively response from readers of the paper.

Massey, who had not completely severed his roots of orthodoxy at that

time, wrote:

That letter in your last number called the ‘Parentage of Jesus, and

Freelove,’ must have given some of your readers a ‘scunner’. To me

it was like a cast-up gobbit of the gross nastiness that used to be

dished by the Atheists … What had it to do with Spiritualism? …

The spirit of it was sensual; the intent was obscene; the language

loathsome … a leering, tongue-lolling gust of carrion enjoyment …

The editor tried to steer a middle course in defending his

decision to publish. Admitting that the act as narrated by the

correspondent was unwarrantable, although an absurd myth, he considered

that it was best to face and deal with the issues rather than behave

like an ostrich. To Massey's remark about the Atheists, he wrote,

‘Thank God for them! Had it not been for their self-denying

labours, where would have been the position of liberty of speech

to-day?’[16]

In the same period of 1872 Massey had obtained almost 100

subscribers that would be necessary to make his book on Shakespeare a

viable proposition for reprinting in a limited edition. One

supplemental chapter was added, being essentially a refutation of

criticism received from Mr Chasles, since his original publication.

In a letter he wondered how best to get his new edition before the

public, saying, 'I sent one Copy only for review and that to the

Athenæum and had it returned with the regret that they did not

review 2nd Edns … ’[17] However, James Burns

arranged for a review in his journal Human Nature that, perhaps

expectedly, gave favourable mention to Massey's vigour of mind, while at

the same time he was ‘breathing a poet's warmth of feeling’ and

‘throwing a vivid light on the court-life in the days of Queen

Elizabeth’.[18]

Soon after publication, Massey's American agents wrote to

inform him that tour plans had been finalised. He completed his

spring lecture tour and prepared to leave England in the autumn.

The disunity between religion and science had become

increasingly obvious since the publication of Darwin's Origin of

Species in 1858, and his Descent of Man in 1871.

Attempts to reconcile the two apparent opposites were of particular

interest to Americans following a tour made the previous year by

Professor John Tyndall, scientist, natural philosopher and

Superintendent of the Royal Institution. It was anticipated that

Massey, coming also from England, would develop the subject. Prior

to leaving, Massey suffered considerable apprehension, having risked his

future finances on the tour being successful. In addition, his

wife was in the last stages of pregnancy, giving birth to Elsie on 13

November. Departing from Liverpool on the s.s. Calabria on

23 September 1873, he arrived in New York anticipating that his first

lectures would be in Boston. However, due to a misunderstanding

with his agent he found that he had been replaced for that course.

This compelled him to wait six weeks before proceeding to Boston, while

the agent made hasty plans for some interim lectures in New York.

Anxious to continue with and enlarge upon Tyndall's theme,

most of the New York papers and journals prepared articles giving an

account of Massey's life and earlier literary works. But in spite

of the publicity, he received no formal meeting of welcome as he had

hoped. In addition, he considered that the lecture bureau had

failed him due to their interest in him being limited to ten per cent.

Consequently, he decided to make his own lecture arrangements for the

rest of the tour, with the assistance of James Fields, the publisher,

who would provide names to whom he could send circulars.[19]

In reply to the Golden Age, which had mentioned him as being a

representative of the English Spiritualists, Massey stated that he no

more represented that body here in America than he would represent when

he returned home the latest uterine manifestation of Spiritualism—or

phalliculture—which were the peculiar products of America. He

preferred to remain an outsider, representing only his own experience as

a literary man who includes the subject in his lectures. He

referred to an article in the Galaxy Magazine for October 1866

which dismissed his book on Shakespeare's Sonnets by saying, ‘He

declares, and even perhaps believes that every section in this ponderous

and wearisome volume was directly revealed to him by the spirit of

Shakspeare!’ ‘Unfortunately,’ Massey commented, ‘we are not going

to get our work so easily done for us as that would imply!’[20]

On 4 October Whitelaw Reid, the proprietor and editor-in-chief of the

New York Tribune, invited Massey to attend the first seasonal Saturday

meeting of the literary Lotos Club, of which he was president. Charles

Bradlaugh was also invited as a speaker, prior to his journey to Boston.

Bradlaugh had left England for a lecturing tour on 6 September, two

weeks earlier than Massey, also with some apprehension. In his case,

this was due to an insulting notice by the London correspondent to the

Boston Pilot, who had referred to him as:

A creature six feet high, twenty inches broad, and about twelve

thousand feet of impudence. He keeps a den in a hole-in-the-wall here,

dignified by the title of the ‘Hall of Science’, in which he holds forth

Sunday after Sunday to a mob of ruffians whose sole hope after death is

immediate annihilation … The Pilot, if it can do nothing else, can

warn our people from laying hands upon this uneducated ruffian.

This was added to by the Boston Advertiser, which said:

In England … practical politicians among the advanced liberal party

avoid him as honest men avoid a felon, as virtuous women avoid a

prostitute.[21]

Massey, although not heralded by adverse comments, said he

expected that he would, on account of his connection with Spiritualism,

be the object within a few months of much obloquy at the hands of the

American press, but he only asked for fair play.[22]

He did not suspect that a comment by Bradlaugh on an incident that

occurred many years previously would also be remembered in some detail

by a newspaper reporter in New York.

Following his first lecture at the Steinway Hall on 3

October, Bradlaugh gave an interview which included ‘A Reminiscence of

Gerald Massey’. The reporter, who signed herself ‘Theo’ asked

Bradlaugh if he and Massey had ever met. Apart from the Lotos Club

reception, Bradlaugh said he had not met with Massey since ‘That

memorable night when you and I went to hear a lecture on Co-operation by

a gentleman named Cooper. Since then Gerald Massey rather fights

shy of me.’ The reporter confirmed that she did remember the

incident. This ‘incident’ was then given with, apparently, some

bias:

A gentleman named Walter Cooper, who was Manager of the Co-operative

Tailors' Association introduced into the Society, in the capacity of

clerk, a young man who was not a tailor, and therefore, not a member, at

a stated salary. This was a direct and flagrant violation of the

rules and by-laws of the Association, which declared that no one but a

member could fill any office in the concern. The main body of

tailors rebelled, and demanded the instant dismissal of Gerald Massey.

A war ensued, which ended in the discharge of one or two of the most

efficient and active members of the Society by Walter Cooper, who, in

some hocus-pocus way, got the sceptre of power into his own hands, and

kept his favourite in office … It was while this furore was at its

height, that Cooper advertised a lecture on ‘Co-operation’ at the Hall

of Science, City Road, London; and Charles Bradlaugh, then a young man,

almost unknown, who was intimate with the discharged tailors, was

appointed to attend the lecture, and, at the close, put a few questions

to the lecturer, while the others should be stationed in different parts

of the hall, to rise, banquo-like, and confront him, to his dismay and

final confusion, when his replies should warrant them in doing so.

Cooper was completely misled by Bradlaugh's youth and innocent

appearance, though he showed considerable surprise and some

embarrassment at the tendency of the questions put, and soon found that

he was indeed stepping among hornets. Gerald Massey, who was on

the platform, with his new-made wife, came to the rescue of his

superior, but only added fuel to the flames. The excitement ran

high, and noise predominated, and at one time there were fears of a

general melee, in the midst of which Mrs Massey rushed to her husband,

encircling him with her arms, and was finally borne from the hall in a

swooning condition. Cooper confounded! Massey annihilated!

Bradlaugh triumphant! and the discharged avenged! Oh! what a merry

time we had going home from the Hall … [23] [Appendix

B gives Massey's account of the Working Tailor's Association.]

Massey's first lecture in New York was held in the Unity

Chapel, 128th Street, Harlem, on 26 October. 'Why does not God

kill the Devil?', although heavily laden with myth lore, was basically

practical. Still suffering from the effects of two colds, which he

thought were due to the peculiar mode of ventilating his room at

Delmonico's Hotel, Massey spoke with a slightly husky voice, with great

rapidity and nervous energy.[24] Making no

attempt at oratory, he spoke directly and sincerely in presenting his

convictions. Why, he asked, if God is the superior being, does he

permit the Evil One to upset his divine arrangements? He had

searched through the ancient mythologies to ferret out the authorship of

this same Devil which theology insists on keeping alive as a main part

of its machinery. He demonstrated that much of what is accepted by

mankind in general as ‘revelation’, is nothing more than inverted

mythology.

Following his second lecture in Association Hall the

following day on ‘A Spirit World Revealed to the Natural World’, he was

referred to as being earnest and sincere, with an enthusiastic

temperament and original thought. He proclaimed that Spiritualism

as he understood it, not its vagaries or follies but its philosophy and

facts, was a New World's gift that amply repaid all that America had

ever received from the Old World. Mentioning the opposition's cry

of hallucination, ‘Blessings,’ he said, ‘upon that word; it constituted

the sceptics whole book of revelation.’ He had no fear for

Darwin's theory, comparing that with man's evolution of his spiritual

nature.[25] At Princeton, his intended visit

was opposed by the faculty, who had heard of his opinions on the new

theology. In spite of this restraint the students arranged for him

to lecture in the Methodist chapel on 20 November. During his

lecture on Charles Lamb, he deliberately made reference to the

persecuting influence of the old theology and, on leaving, inscribed

some verse to the professors on the subject, in a college album:

|

You had the power, and you and yours

Upon me slammed some outer doors;

But if you look you'll see, and start

To find me in the student's heart … [26] |

From New York he went on to Philadelphia, giving a lecture on

‘Hood’, on 25 November at the Horticultural Hall. As with his

portrait of Lamb, he noted the lights and shadows of Hood's mental

moods. He contrasted his wit and pathos with his poetry and puns,

even while living within the sight of death for years.[27]

Continuing via Buffalo, he delivered his lecture on the ‘Devil’ at the

Mercantile Library Hall, St. Louis. This was not appreciated by

the editor of the St. Louis Central Baptist, who wrote with

passion, ‘… the devil never would insult an intelligent audience with

the stuff that passed for literature in Mercantile Library Hall last

week. He is too much of a gentleman.’[28]

Massey's next venue was in Chicago. As part of the

‘Star’ lecture course, he was booked at the Kingsbury Music Hall for 9

December. Despite a considerable amount of advertising by his

agents, his lecture on ‘Charles Lamb’ was attended by two-thirds of

empty chairs—the equivalent amount of applause being given to an

introduction by the Star orchestra. After that preamble, Massey

came in by a side entrance appearing unusually nervous, and immediately

commenced his lecture. The reporter did not consider Massey either

handsome or to have an intellectual appearance, observing his thin

moustache and side-whiskers, with hair parted in the middle. The

lecture itself was well appreciated, the critical reporter referring to

Massey's considerable imitative ability and versatility of expression.

But he noted also the occasional omission of an aspirate, and

pronunciation of ‘unctious’ for ‘unctuous’, twice. He had a very

rapid delivery which tended to puzzle the audience until they became

attuned to it. Also in the audience were ‘Theo’ and some of her

friends, of whose presence Massey was probably aware and fearful they

would make another disruption. ‘Theo’ was Richard Carlile's

youngest daughter, Theophilia. Charles Bradlaugh had been friendly

with Carlile's widow, her son and two daughters, whom he first met in

1848. After the lecture when Massey was met in the lobby, he still

appeared very nervous and indifferent. ‘Theo’ referred to one

person being present whom he barely acknowledged, as 'One who had

assisted him in his early days' and ‘from whose house his first poems

were published,—who had waited with the most delightful anticipations

for his visit to Chicago … ’[29]

The comments on Massey's elocution were reinforced in a

lecture report on ‘Jesus’ which he gave at the West Side Opera House on

14 December. He was again accused of being extremely rapid in

speech and, in addition, making some comments which were too flippant.[30]

For his next lecture arranged by the Free Religious Society, General

Israel Stiles, lawyer and anti-slavery orator, presided. In his

opening address, he referred to Massey as an enemy of opposition and

wrong, and one of the distinguished visiting English lecturers among his

countrymen Thackeray, Dickens and Tyndall. During his lecture

‘Christ, a Medium’, Massey announced Christ as the greatest Spiritualist

of all time, but pronounced his disbelief in the doctrine of the

Trinity. Even this comment was well received by the audience.

His second lecture the following day on ‘Why does not God kill the

Devil?’ was advertised as free, and additional to an already prepared

schedule. The arrangements for this were made by the chairman of

the Chicago Philosophical Society, the Reverend Hiram Washington Thomas.

Due to the unorthodoxy of the Chicago lectures, the Trustees of the

Chicago Methodist Church who had let their building to the Society for

that lecture, made a protest. The executive committee of the

Philosophical Society replied, saying that they recognised the Church's

right and duty to protest against the improper use of the church

property; but ‘In the case of Gerald Massey's lecture, we did not use

our usual caution in ascertaining the character of it; and are equally

free to say that, had we been aware of its character, we should have

declined it.’[31] Hiram Thomas was later tried

for heresy in 1881, and accused then of bringing the liberal-minded

Massey to Chicago.[32] Despite the strong

reservations of the Philosophical Society, the editor of the Religio-Philosophical

Journal was pleased with a personal meeting with Massey, in which

Massey aroused his interest in spirit communion, and took uncompromising

grounds concerning the status of the religious systems of the time.

On arriving in Boston for his own organized series of

lectures, he was greeted by his friends James and Annie Fields.

Feeling more at ease with the New Englanders, he was able to relax and

make further friendly contacts. The poet John Greenleaf Whittier

appreciated Massey's humane idealism, the two of them meeting at

Whittier's home at Amesbury, where Massey's poems remain in Whittier's

study. It is possible also, but not recorded, that he met Harney,

who had moved to America in 1863 and was living then in Boston.

Massey opened his series of four weekly lectures to the Music

Hall Spiritualist Society, Boston on 4 January 1874. Having had to

alter his plans on his arrival in New York, he said in a letter to James

Fields, ‘I have to begin as in New York with the despised Spiritualism

in default of anything else.’[33] Music Hall

had a large capacity, and was the theatre where Queen Victoria's Prince

Edward (Bertie) was welcomed with a music festival by some 1,200 school

children during a tour in 1860.[34]

Improved health and greater confidence showed in his first

lecture ‘Why am I a Spiritualist?’ which was heartily appreciated, the

Boston Post noting his clear, full voice, his fluently expressed

ideas and eloquent delivery. The Banner of Light of 10

January reported the lecture very adequately. Henry Wilson, USA.

Vice-President, the scientist Professor J. Buchanan and William Claflin,

ex-Governor of Massachusetts were present for his second lecture, ‘An

Inquiry Concerning a Spirit World … ’[35] The

third lecture on Jesus Christ was equally well received. The

fourth and last lecture, (with singing by a choice choir) on ‘Why Does

not God Kill the Devil?’ had been commended previously by the Chicago

Religio-Philosophical Journal as ‘replete with evidence of the

mythological origin of the basis of all religions … ’ and ‘was one of

the most masterly and exhaustive lectures ever delivered before a

Chicago audience.’

|

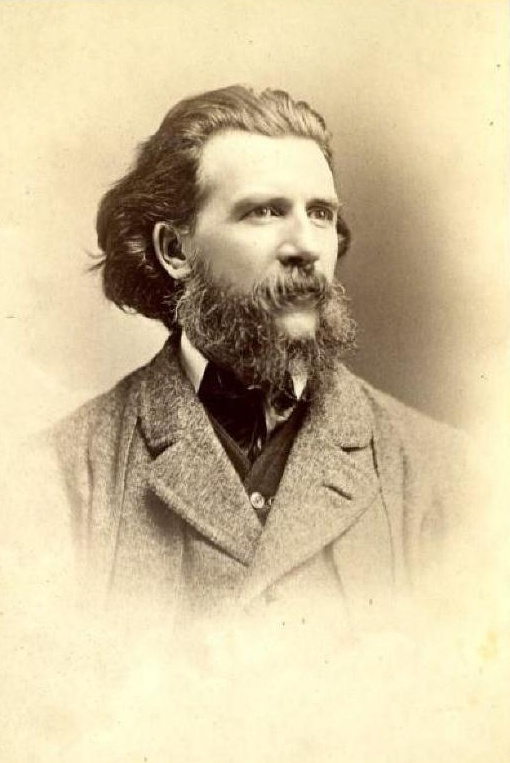

Gerald Massey. A Cabinet photo.

|

On 17 January the Franklin Typographical Society held its

semi-centennial anniversary incorporating the one hundred and

sixty-eighth anniversary of the birth of Benjamin Franklin, at the

Odd Fellows' Building, 515 Tremont Street. Having a membership

of over one hundred and fifty, the society accepted all types of

employment connected with the printing trade. Charitable to

its members, it also served their literary interests with a library

of two thousand books. At the meeting musical entertainment

was provided, and speeches following regular toasts were given by a

number of invited guests of honour. These included Governor

Washburn, E. B. Haskell, editor of the Boston Herald, Charles

Slack, editor of the Commonwealth, W. H. Cundy, president of

the society, and others, with of course, Gerald Massey. The

Society claimed Massey as one of their craft, said the president,

because at the age of twenty-one he was the editor of a newspaper.

Responding to great applause, Massey said he had been allowed twenty

minutes, but feared that once on his feet he would speak for the

whole evening. He continued, adding elements of his social

gospel in his speech which he thought the audience would appreciate:

I am pleased that the first public social reception given to me

in Boston should have come from the working-men. I was born

among the workers, and to them I belong. At the present time I

am associated with a subject that is tabooed and unfashionable—so

much so that only a single preliminary word of welcome was given to

me by the Boston press. It has always been my fate to stand on

the weaker and unpopular side, and it is so still. But,

gentlemen, I can assure you it was the side that came uppermost and

was the stronger in the end, and I do not doubt it will be so with

this much despised subject of Spiritualism … None but the despised

Spiritualists invited me to speak in Boston … But I do not wish to

increase the consciousness of those who have such a dislike to

Spiritualism by making them feel it is a case of ‘like me, like my

dog’ … I have been toasted again and again as a poet of the people

and the poet of the poor. The effect on my mind is very

curious. It appears as though I had come to America to

discover myself … I was here for weeks without being conscious of my

nationality. The man I see reflected in the mirror is the boy

of twenty-five years ago who sang the songs of love, and labour's

chivalry. But all I care for now is to get something done—help

on the living deed rather than set words to music … I maintain that

the first practical attempt at practical Christianity is the

co-operation of capital and labour and the unification of these

interests in one. No rise in the rate of wages will ever solve

the problem. It is merely out of one pocket as soon as it is

in the other, so long as prices rise all round the income of the

worker … I am not here to empty the butter-boat down your backs, in

return for the dinner you have given me, but Hawthorne once said,

‘all Englishmen were detestable in the lump, but individually he

liked every one of them.’ Perhaps if you didn't lump us so

much, you may come to like us more … If I should serve only as the

smallest thread in knitting the universal tie … I shall be prouder

of that than of all my poetry.

Letters from supporters were read out, including one from

John Greenleaf Whittier, the poet and champion of emancipation, who

wrote that illness kept him from the dinner. But he would be

glad to see his place filled by a gentleman well and honourably

known on both sides of the Atlantic, Gerald Massey, of England.[36]

During his speech Massey had told how he had met dainty

ladies, who looked as though they had just come through a shower of

jewels, congratulate him on his poem 'Little Willie'. They

were so innocent of the fact that ‘poor little Willie’ was one of

his brother's children who had died a cruel death in a workhouse,

and was buried in its grave.

|

In the day we wandered foodless,

Little Willie cried for bread;

In the night we wandered homeless,

Little Willie cried for bed.

Parted at the Workhouse door,

Not a word we said:

Ah, so tired was poor Willie,

And so sweetly sleep the dead.

'T was in the dead of winter

We laid him in the earth;

The world brought in the New Year,

On a tide of mirth.

But, for lost little Willie,

Not a tear we crave;

Cold and Hunger cannot wake him,

In his Workhouse Grave. . . |

On completion of his first Boston lecture series, Massey sent

a triumphant telegram to Whitelaw Reid at the New York Tribune

office saying, ‘I concluded my course yesterday in Boston with an

audience of two thousand people.’[37]

Massey was always ready to champion a cause or person that

was generally unpopular or that he thought deserved social

recognition at the time. He had written ‘To a Worker and

Sufferer for Humanity’ in 1850 in praise of the Rev. Maurice, when

Maurice was being persecuted at King's College, from which he was

expelled in 1853 on account of his opinions.[38]

It was revised later as ‘Maurice

and the Bigots’.[39] Florence

Nightingale's valiant work in the Crimea was saluted sentimentally

in a section of ‘Glimpses of

the War’ in Craigcrook Castle, and reprinted later as ‘Our

English Nightingale’.[40] In a

twenty-four stanza poem he had made an appreciation of W. M.

Thackeray (‘William

Makepeace Thackeray’) on the occasion of his death in 1863.

Thackeray had attended a number of D. D. Home's seances and, while

editing the Cornhill Magazine, had endorsed an article ‘Stranger

than Fiction’ in the edition of August 1860. Robert Bell was

the anonymous author, and gave an account of Home's levitational

powers. Thackeray was attacked for publishing the article, and

the magazine suffered a sharp decline in circulation.

One of the many people with whom Massey had come into contact

during his tour was Colonel John Hay. He was an editorial

writer on the New York Tribune, and had been assistant

secretary to President Lincoln. A composer of ballads, his

poems Little Breeches, and Other Pieces which he wrote in

1871, were better known by name than its poetical content. As

a mark of respect Massey composed a special poem to him for his

wedding day, 8 January 1874, and wrote asking Reid to publish it

verbatim in that particular issue of the Tribune.

Unfortunately, some pretentious over-effulgence at times made

Massey's personalised poems incredibly mediocre:

|

GERALD MASSEY TO JOHN HAY

GREETING ON HIS WEDDING DAY

I said, when I crossed the ocean

You had bridged in your own arch way,

'Twas worth while, I have a notion,

If only to meet John Hay!

Just long enough have you tarried,

And this is your wedding day!

God double your life, when married,

And treble your luck, John Hay!

May heart in heart together

Make honey-moon all the way

And bring you the heavenliest weather

Through the long voyage, John Hay!

I can't speak one of the speeches,

But I send you a greeting, and pray,

For lots of 'Little Breeches'

'Hell-to-split' round you, John Hay! |

The poem was not appreciated by Whitelaw Reid, who wrote on

the letter:

Dear Hu[——]d. This seems to me infernally bad. What do you say?

W. R.

Disgusting! J. H.[41]

The poem was not published.

From Boston, Massey went on to Poughkeepsie, where he

lectured at Vassar College on 8 January on ‘A plea for reality, or

the story of the English Pre-Raphaelites’. He had developed

this theme to become one of his favourite subjects, and it was by

then firmly established in his lecture series. The

Pre-Raphaelites, formed in 1848 as a ‘Brotherhood’ against the Royal

Academy's control over British art, included D. G. Rossetti, John

Millais and Holman Hunt. They considered that there should be

a reform in art and realism, with observation and feeling expressed

by aesthetic techniques. This idea was demonstrated also in

their poetry, where sincerity and descriptiveness of emotions earned

them the name given to them by Robert Buchanan, of ‘The Fleshly

School’. Buchanan had called their Journal the Germ ‘an

unwholesome periodical’ and in a reply to Rossetti's spirited

response referred to some of his ‘unsavoury’ poems as ‘flooded with

sensualism’.[42] In his lecture Massey

referred to their intent of reform as to do ‘anything to avoid

repeating the simpering imbecilities of the drawing-room ideal of

unmeaning prettiness’, and that they ‘made war on the critical

canons laid down by Sir Joshua Reynolds’. They were true to

nature, he said, and the only means of approaching the ideal is

through the real. He included also some remarks with a

Spiritualistic theme.[43] The president of

the college later wrote to Massey that:

Whatever differences of opinion there might be … [and differences

there were] in regard to the main doctrine of the lecture, or some

of the opinions incidentally indicated, all agreed that it was an

admirable exhibition of the fundamental idea of this interesting

movement in art, and a forcible presentation of the arguments in its

behalf … [44]

Massey returned to Chicago at the beginning of February,

where he repeated his lecture on the ‘Devil’ at Grow's Opera Hall on

15 February. This was the lecture that had so annoyed the

Methodist Church Block the previous December. But the press

were favourably disposed towards his nonconformism, one paper, the

Chicago Daily Times, comparing Massey's scholarly effort with

some previous Sunday speakers. Dr Cheney (Baptist) had been

abstruse, sonorous and somnolent. Dr Thomas had speculated on

an intermediate state between death and the resurrection, which was

just exactly as demonstrable, curious and instructive as would be a

speculation as to whether the inhabitants of Neptune break their

boiled eggs at the small or big end. The paper admitted that

Chicago had thousands of people who never enter a church; while they

wish for food, they are given a doctrinal stone; they wish to know

how to live, and are told only how to die. Unorthodoxy was ‘a

protest against a social condition in which oppression, poverty,

misrule, suffering, are rampant everywhere, and the only remedy

offered is such a misty one as is promised in some future state of

everlasting psalm singing and praise … ’[45]

From Rand's Hall, Troy, Massey went on to the Pacific coast

to a full house of three thousand at Platt's Hall, San Francisco, on

15 April. His second lecture the following evening on ‘The

Coming Religion’ contained ‘some of his strongest passages—for the

utterance of which a couple of centuries ago he would reverently

have been burned—and were warmly applauded, though not by many

persons.’[46] Via the Melodion Hall,

Cincinnati, at the end of April, he returned finally to Music Hall,

Boston, on Sunday, 3 May for a lecture on ‘The Serpent Symbol: its

Spiritual and Physical Significance’. There was a large

attendance, many people coming in by train on Saturday to listen to

‘the people's poet, whose soul goes out with wonderful power to the

hearts of the oppressed’.[47] For his

farewell lecture on 10 May, ‘The Coming Religion’ included the

necessity of having women as positive partners in family life.

He summarised his hopes of the future for a purer, more practical

Christianity based, as he continually advocated, on Spiritualistic

and socialistic ideals without orthodox theology:

Men have believed there must be a physical resurrection,

otherwise the damned could not gnash their poor teeth in eternal

torment. Men believe they ought not to bow down before any

graven image, who all the week go down and grovel in the dust on all

fours in front of one that twinkles golden and winks … having on it

the image of the queen or president stamped on the current coin of

the realm. If you were one of the elect, having been saved

through believing in Adam's sin then, according to Mr Spurgeon, you

can expect the entertainment of seeing those other poor, damned

souls whose veins are roads for the feet of pain to travel in, and

every nerve is a string on which the devil shall for ever play his

diabolical tune of hell's unutterable torment. And as the song

of the ransomed was singing, word would come that your father was

among the damned, and you would sing all the louder; or that several

of your little ones were in hell, and your hallelujahs would be

redoubled … The only final reality is a communicating consciousness

… The highest form of visitation from the living God is not found by

the bended knees of contemplative piety, but by the weary feet of

active charity.[48]

During the lecture Massey mentioned that while he was in

America he had sat with a medium who produced on a photograph the

likeness of his dead daughter, Marian. This was probably the

psychic photographer William H. Mumler of Boston who, in 1861 when

an amateur, had developed a self-portrait photo which showed

standing next to him, the likeness of a cousin who had died twelve

years earlier. Mumler was investigated, and caused great

interest and controversy, fraud being undetected.[49]

Nevertheless, he was accused on one occasion of deception, but

acquitted following a trial in 1869.[50]

While he was on tour Massey had been told of another

instance, similar to John Plummer, where he had inspired self-help.

A poor emigrant Scotsman's son in Wisconsin who, twenty years

earlier while farming two hundred acres single handed, had received

his lunch of buckwheat cakes wrapped in a page of the New York

Tribune. The review of Massey's

Poems and Ballads

together with the biographical sketch was printed on that page.

Reading that account of Massey's early life influenced the man to

educate himself, following which he obtained a literary post

involved with the promotion of education.[51]

Massey was very pleased that his own example of Samuel Smiles'

Self Help had produced at least two known positive results.

His tour completed, and having made $3,000 from his American

venture, Massey left New York on the 16th May on the s.s. Java.

During his absence his mother, aged 77 years, had died of heart

disease and bronchitis on 8th January at Clement's Yard, Akeman

Street, Tring. Her husband would survive her by six years, in

a state of continual poverty.

Throughout his more recent lecture courses when dealing with

a greater number of Spiritualistic and universal religious themes,

Massey was compelled to make increasing reference to source material

with their apparent analogies and divisions. In common with

most youthful radicals he had read the works of Paine, Voltaire,

Volney, and the critical exegesis of gospel history serialised by Thomas Cooper in his Journal.

Under the general term ‘Freethought’, which included Spiritualism,

the more recent lectures and writings of the Reverend Charles Voysey

of the Independent Theistic Church, Swallow Street, Piccadilly,

together with the atheist Charles Bradlaugh and secularist George Jacob Holyoake, had

brought to many a greater awareness of historical and theological

division.[52] To Massey, acceptance of the

syncretisation of science and deism without the tenets of orthodox

theology appeared as no problem, and his lectures in that aspect,

apart from his strong individual presentation, were not new.

The possibility of a personal relationship with God, as defined

theistically, was supplanted by Massey in the form of the

Spiritualistic belief of survival and communication of post-mortem

personality. However, his assertion of Spiritualism as being

fundamental to both science and deism was original, and unacceptable

to his otherwise more numerous secular supporters.

The atheists gave no credence to supernatural theories, hence

could not accept Spiritualism. They were unable to believe in

the reality of any God manufactured by the world's religionists,

which must be something outside, distinct from, and superior to

everything. No human being could therefore have any rational

idea of it, or could even comprehend it.

The secularists, not necessarily denying the doctrine of a

life beyond the grave, provable theologically only after death,

based their beliefs upon the observance of life, of which the

practical problems could be solved here and now for the happiness of

humanity. They considered that this itself provided a moral

code, ‘the good of others’. The existence of a personal God

was not in general acceptance, although they would not have the

arrogance of divine knowledge to deny it.[53]

Following his return to England in 1874, Massey issued in

July a list of twelve lectures he was prepared to deliver during the

coming winter season. These contained nothing new, as he was then

commencing more extensive research into mythological and religious

origins that he hoped eventually to publish in book form. He planned

that the summer months would be occupied with this, and he requested

a rapid renewal of his British Museum library ticket.[54]

Also during that month, large newspaper headlines announced

the ‘North London Railway Murder’. On the evening of 9 July,

Thomas Briggs, a banking-house clerk was found on the railway line

between Bow and Hackney Wick stations, dying shortly after without

regaining consciousness. He had sustained bodily injuries that

were due to his fall, as well as head wounds that were consistent

with blows from a blunt instrument. Although robbed of his

watch and chain, sovereigns and other valuable items had not been

taken. Suspicion fell on Franz Muller, an out of work German

tailor, who had been planning after two years in England, to travel

on to America. Shortly after the incident it was confirmed

that Muller had taken a boat to America, where he was arrested and

brought back to England. In his possession he had Briggs'

watch which, he stated later, he had purchased from a man at the

docks, and a hat, also thought to have belonged to Briggs. His

own hat was found in the train compartment. The trial

commenced at the Old Bailey on 27 October on complex evidence that

was largely circumstantial and often conflicting in

cross-examination.[55] One witness who knew

Briggs, stated that he saw two men in the open-seated compartment

with Briggs at Bow station, where he entered the train in another

carriage, though could not recognise Muller as one of the men.

He had spoken to Briggs, who had replied. On the final day of

the trial on the 29 October, and after fifteen minutes deliberation

by the jury, Muller was found guilty of murder.

At the time of the trial, Massey and his wife who were

experimenting with a form of planchette writing, obtained a message

purporting to be from the deceased Briggs, which stated ‘Muller not

guilty; robbery, not murder’. This surprised Massey, and

induced him to look carefully into the evidence. Not finding

the case conclusive, he wrote a long letter to eight daily papers

which, he considered, was the best piece of logical reasoning he had

achieved up to that time.[56] The letter

was published only by the Daily News, Massey taking the

position that robbery was the motive for the attack. He

thought also, mentioning other evidence, that Briggs had tried to

escape after exchanging blows with Muller, by leaving the carriage

by the footboard and attempting to get into the next compartment.

During this manœuvre he fell and his head was struck by the buffer

of the next carriage. Under these circumstances, a conviction

of manslaughter would have been more appropriate.[57]

Muller was hanged by public execution on 14 November in front of

Newgate gaol. Intense pressure by clergy had been put on him to

confess to the murder, although he admitted only to committing

robbery. At the last minute on the scaffold, following a

conversation, the German minister in attendance announced

triumphantly that Muller had confessed by saying, ‘I have done it,

and no one else.’ The whole scene was viewed with enjoyment and

regarded as entertainment by an unruly crowd who were jesting,

making obscene jokes and mocking the clergyman's prayers. Appeals

for clemency, and doubts over some of the evidence that Massey had

brought to public attention following the trial, were disregarded.

[Chapter 7]

NOTES

|

|

1. |

In

Human Nature, Vol. 5,

Aug. 1871, 420. |

|

2. |

Medium and Daybreak, 4 Aug.

1871, 247-51. |

|

3. |

Ms. University of Texas. Although

Tennyson had extended an invitation for Massey to visit him at his

home on the Isle of Wight, he had never managed to get there. The

two did eventually meet in London while Tennyson was on a visit to

his doctor. |

|

4. |

Spiritualist, 15 May 1872,

36. Human Nature,

May 1872. Medium and

Daybreak, for 1872 (the editions for 29 March, 112-113; 17

May 1872, 177-79, 182-3; 24 May, 189-191; 31 May, 201-202; 7 June,

213-215; 218.) |

|

5. |

Walker, A. (ed.), Letters of

John Stuart Blackie (London, Blackwood, 1909), 211. Blackie

retained an interest in the subject, attending a séance with a

number of other notable persons at the home of Professor Gregory's

widow, in 1877. Cited in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's History of

Spiritualism 2 vols (London, Doran, 1926), 2, 47-48. |

|

6. |

Quarterly Review, Oct. 1853. |

|

7. |

Globe, 13 May

1872, 3. |

|

8. |

Medium and Daybreak, 26 Nov.

1886, 756. |

|

9. |

In Davies, Charles, Heterodox

London 2 vols. (London, Tinsley Bros., 1874), 1, 137-267. |

|

10. |

As cited in Medium and Daybreak,

10 Jan. 1873, 17. |

|

11. |

Report on Spiritualism of the

Committee of the London Dialectical Society, together with the

evidence, oral and written (London, Longmans, 1871. Abridged ed.

Burns, 1873). |

|

12. |

Medium and Daybreak,

1 Nov. 1872,

430. 15 Nov. 1872,

452. 22 Nov. 1872,

460. |

|

13. |

Ibid. 3 Jan.

1873, 5. |

|

14. |

Ibid. Cited

31 Jan. 1873, 57. |

|

15. |

From a lecture given under the

auspices of the Swedenborg Lecture Bureau, New Jerusalem Church, 16

Dec. 1883. Cited in Banner of Light, 22 Dec. 1883, 4. |

|

16. |

A biographic sketch of Mrs Woodhull

reprinted in Human Nature, 6, (Jan. 1872), 22-42. Relevant

correspondence in the Medium and Daybreak is in the issues of

1872, 2 Feb. 40-41. 16 Feb. 58. 23 Feb. 66. 1 Mar. 78-79 (Massey's

letter). 8 Mar. 91. 22 Mar. 103. |

|

17. |

Trinity College, Cambridge.

209.c.85.158. Add. Mss. 75/67. Addressee unnamed. |

|

18. |

Human Nature, 6, (April

1872), 209-14). |

|

19. |

Ms. The Huntington Library, San

Marino, California. |

|

20. |

Cited in Banner of Light, 8

Nov. 1873. |

|

21. |

Bonner, Hypatia Bradlaugh,

Charles Bradlaugh. A Record of his Life and Work (London, Unwin,

1908), 380-1 |

|

22. |

Cited in Medium and Daybreak,

31 Nov. 1873, 497. |

|

23. |

Chicago Daily Tribune, 28

Dec. 1873, 11. See also Charles Bradlaugh, op. cit., vol. 1,

9-19 and 388 for Bradlaugh's relationship with Carlile's family. The

incident is unrecorded in this or Headingley's biography, and

untraced in the Northern Star or Reynolds's Weekly

Newspaper of that time. Bradlaugh's interview with ‘Theo’ is not

mentioned in his letters to the National Reformer.

|

|

24. |

Medium and Daybreak,

19 December, 1873, 602. Ms. The Library of Congress. |

|

25. |

New York Times, 28 Oct.

1873. |

|

26. |

New York Daily Graphic, 22

Nov. 1873. |

|

27. |

Ibid. 28 Nov. 1873. |

|

28. |

Cited in Banner of Light, 3

Jan. 1874. |

|

29. |

Chicago Daily

Tribune, 10 Dec. 1873. This was probably

W. J. Linton, who moved to America

in 1867. Whilst Massey was at Brantwood, in 1860, W.J. Linton was

his landlord. |

|

30. |

Ibid. 15 Dec. 1873. |

|

31. |

Spiritualist, 13 Feb. 1874,

84. |

|

32. |

Hawley, Charles, ‘Gerald Massey and

America’ in Church History, 8, 4, 362-3. |

|

33. |

Ms. The Huntington Library, San

Marino, California. |

|

34. |

Roby, Kinley, The King, the

Press and the People (London, Barrie & Jenkins, 1975), 81-82. |

|

35. |

Banner of Light, 17 Jan.

1874. Lecture report pp. 1-2. |

|

36. |

Boston Daily Advertiser, 19

Jan. 1874. Also the Banner of Light, 24 Jan. 1874. |

|

37. |

In the Library of Congress. |

|

38. |

Christian Socialist, 1, 16. |

|

39. |

My Lyrical Life,

2, 78-79. |

|

40. |

Ibid. 365-67. |

|

41. |

Library of Congress. |

|

42. |

The Fleshly School of Poetry

(London, Strahan, 1872), 58. |

|

43. |

New York Daily Tribune, 9

Jan. 1874, 2. |

|

44. |

Cited in Banner of Light, 14

Feb. 1874. |

|

45. |

Editorial article in the Chicago

Daily Times, 17 Feb. 1874, and reprinted in Human Nature,

8, (May 1874), 238-9. |

|

46. |

Daily Evening Bulletin, 16

Apr. 1874 and Daily Morning Call, 18 Apr. 1874. Cited in

Banner of Light, 2 May 1874 and Medium and Daybreak, 15

May 1874, 314. |

|

47. |

A nearly complete report of the

lecture was given in the Banner of Light, 9 May 1874 and

reprinted in Human Nature, 8, (July 1874), 301-12. |

|

48. |

Banner of Light, 16 May

1874, 7-8. Also Cincinnati Commercial, 1 May 1874. |

|

49. |

Permutt, Cyril. Photographing

the Spirit World. Images from Beyond the Spectrum (London,

Aquarian Press, 1988), 12-14. |

|

50. |

Spiritual Magazine, Jun.

1869, 245-66. |

|

51. |

Banner of Light, 14 Jan.

1874. |

|

52. |

Reverend Charles Voysey

(1828-1912), a founder of the Cremation Society, was convicted of

heresy in 1869. An account is given in M.D. Conway's The Voysey

Case (London, Scott, 1871). |

|

53. |

‘Secularism and Secularism,’ in

Heterodox London. Op. cit. |

|

54. |

Medium and Daybreak, 31 July

1874, 484. British Library Add. Ms. 45748.f.12. |

|

55. |

Daily News, 28 Oct. 1874,

2-3. 29 Oct., 2-3. Verdict, 31 Oct., 2-3. |

|

56. |

Medium and Daybreak, 17 May

1872, 178. |

|

57. |

Daily News, 10 Nov. 1874, 3.

See letters in 11 Nov., 2. Execution, 15 Nov., 5-6. A detailed

background and account of this alleged murder is given in 'Mr

Briggs' Hat. A sensational account of Britain's first railway murder'

by Kate Colquhoun (Little, Brown, London 2011). See p. 275-6

for a theory similar to Massey's, but no direct citation is given. |

|