|

[Back

to Chapter 5]

CHAPTER FIVE

SHAKESPEARE AND SPIRITUALISM

[1863-1870] |

|

Men counted him a dreamer: - dreams

Are but the light of clearer skies,

Too dazzling for our naked eyes;

And when we catch their flashing beams,

We turn aside, and call them dreams!

(Ernest Jones) |

|

|

THE year of 1863 was

slightly less traumatic for Massey. Although remaining financially

constrained and tied considerably by his wife's illness, he continued

reviewing for the Athenæum—thirty-two books that year—and

contributed fifteen poems for Good Words. Those together

with two major articles showed some improvement in his literary output.

His opinions, despite being openly partisan at times, were generally

fair in criticism of both new and established authors, and a number of

his longer reviews are very well constructed. But one is left

querying with Walter Bagehot the difference between 'The review-like

essay, and the essay-like review', which was so evident in the major

mid-Victorian periodicals.[1]

Professor Aytoun, who had pseudonymously authored ‘Fermilion’

in the Spasmodic style, was cast aside in Massey's review of Nuptial

Ode. He had probably not forgotten Aytoun's scathing remarks

which he thought had referred to ‘Babe Christabel’. With that in

mind, Massey was blunt but surprisingly polite in return:

The writer cannot write poetry. He lacks the natural touch of

its quickening spirit; the possession of its genuine fire. Here is

no striving life; no lofty music; no airy elegance; no dainty grace.

Instead we find a treatment unspeakably commonplace …[2]

A number of years later when lecturing in Australia, Massey

was introduced as the person who had presented

Jean Ingelow to the Northern

Hemisphere. His carefully constructed appraisal of her

Poems ensured their continual

popularity and provided her with a successful literary career. ‘…

We are guarded, and desire not to exaggerate what we have found in the

little book … this new volume will make the eyes of all lovers of poetry

dance with a gladder light than if they had come upon a treasure-trove

of gold …’[3]

It was a year or two before this that Massey became more

interested in and involved with Shakespeare in general and the Sonnets

in particular.[4] This is noticed first in a

review by Massey of Charles Cowden Clarke's

Shakespeare Characters; chiefly

those Subordinate. His critique was of greater length than

usual, and would qualify for Bagehot's 'Essay-like review' remark.[5]

Ideas were then being formed gradually that would result in some

developed theories regarding Shakespeare's Sonnets. At the same

time, articles on Thomas de Quincey,

and the life and times of Thomas

Hood, showed that he was now fully developed as an essay writer with

an easy, yet critically discerning eye for objectively phrased

sensitivity—a feature that was sometimes lacking in his own poetical

compositions.[6] During 1864 he continued to

submit some of his lectures to journals, although he had hoped, for

financial reasons, to have had them published earlier as a series.

In the article ‘New

Englanders and the Old Home’ he noted that the emigrants' new

conditions had developed a change in their character, which was being

determined to a great extent by the material size of that country.

When Dickens wrote the sketches of Yankee character in Martin

Chuzzlewit, they were attacked in America as gross caricatures, but

enjoyed in England as pleasant to laugh at, if not entirely to be

believed. Since then, it was found that Americans do produce such

characters and perform such things as cannot be caricatured.

Massey regarded Emerson as one of the few who protested against some of

the worst American characteristics—big and blatant to usurp

attention—being accepted as representational. On the other hand,

he considered that it was Nathaniel Hawthorne's rather shallow judgement

of his visit to England which prompted him to regard British power as

having culminated and was in solstice, or was already declining.

Hawthorne had wished that the thirty million inhabitants of England

could be transferred to some convenient wilderness in the great American

West, whilst a half or a quarter of that amount of Americans could be

transferred to England. The change would be beneficial to both

parties. Praising the English weather and verdant gardens,

Hawthorne was surprised at the amount of wasted labour expended in

producing ‘an English fruit, raised in the open air, that could not

compare in flavour with a Yankee turnip’.[7] In

summary, Hawthorne probably found that England was far too good for the

English!

Robert Browning had always been one of Massey's favourite

poets; hence he was pleased to review Browning's

Dramatis Personæ, when the

Athenæum sent him a copy. In this review he referred to the

anomaly noticed by readers of verse at that time, in the apparent

inconsistency to attain consistency; novel poetry which is dramatic in

principle and lyrical in expression. In Browning's poetry,

referred to as ‘Browning's Fireworks’, he admits to some ‘obscurity’ due

to suggestions which, in subjective poetry can effectively be left to

the imagination, but when objective, require more visible forms of

expression.[8]

A few months following this review, his attention had been

drawn to an article in the

Edinburgh Review which, he was told, had ‘come down a smasher on

Robert Browning’. Assured by the writer that his poetry could not

survive except as a curiosity and a puzzle, Browning was accused of

being a mine of examples to illustrate some ‘Theory of the Obscure’

disfigured by grotesque and extravagant conceits, and clumsiness of

diction. Massey was quick to spring to Browning's defence in

The Reader, saying that:

I turned with some eagerness to the article; because, when any one

gives a verdict so sweeping, he ought, at least, to show some

unmistakable warrant for the authority. I have now read the article, and

been so excessively tickled that I should be greatly obliged if you

would permit me to laugh aloud over it: it will do me a world of good

…

He then proceeded selectively to criticise the writer for

obscurity and lack of accuracy in English, much in the same way that the

writer criticised Browning. But he did not mention directly his

own opinions of instances of Browning's ‘obscurity’.[9]

The article that first introduced his ideas regarding

Shakespeare and his Sonnets was published in April, to which he was

indebted for helpful suggestions from James Halliwell—later

Halliwell-Phillipps—Hon. Secretary of the Shakespeare Society:

Rickmansworth,

Herts.

Feby. 11th 1864.

… My article is on the personality of Shakespeare, which depends less on

dates than any other kind of treatment … My opinion is that the

fact of the dedication being run into one is fatal to Mr. Chasles'

interpretation. Would not Thorpe have corrected that, supposing the

Printers to have bungled it? … The first begetter I make to be

Southampton … having got thus far makes it possible that Marlowe was the

rival poet … My chief points with the Sonnets are to attack Brown's

theory and show that Southampton was not one of the two friends in

person but wrote sonnets for both … If you have any external

illustration of this internal evidence I shall be glad indeed … [10]

He continued in a letter dated 19 April:

My Article is at Length advertised. It had to be cut down, but

I consider myself lucky to have got it in the Q.R. at all. I shall

be glad to hear what you think of my theory … The argument is only in

skeleton; I hope to clothe it in a book, when I have heard what is to be

said against it … I am anxious to see how it is proposed to replace

Shakespeare where I have seated Southampton … P.S. Of course the Article

must not be publicly written of as mine, at present.

‘Shakspeare and his

Sonnets’ commenced with an introduction by way of a brief synopsis

of Shakespeare's life, up to the first edition of the Sonnets in 1609.

Massey then contrasted the divisions of opinion on the identity of the

initialled ‘Mr. W. H.’ being ‘the onlie begetter’ in Thorpe's

dedication. Dr. Nathan Drake thought it was Henry Wriothesley,

Earl of Southampton; Charles Brown and Benjamin Wright gave it to

William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke, while Philarète Chasles considered

that it was William Herbert, who dedicated the Sonnets to the Earl of

Southampton. Taking ‘begetter’ in the sense of ‘obtaining’, Massey

held that it was William Herbert who had collected the Sonnets via the

Earl of Southampton, the original ‘obtainer’. Later investigators

into the Sonnets considered that the word 'begetter' in the dedication

could be used either biologically or metaphorically, but principally in

the sense of creating. Massey was to deal with this again, some

years hence. In sectioning the Sonnets as a series of events,

Massey determined the earliest as being devoted to Southampton.

Nos. 44-52 are connected with Southampton's courtship with Elizabeth

Vernon, cousin to the Earl of Essex, as told through Southampton (not

Shakespeare) prior to their marriage in 1598. Nos. 109-125 concern the

defence of Shakespeare on behalf of the Earl, on the Queen's opposition

to their marriage.

Following the publication of his article, Massey wrote again

to Halliwell on the 6 May:

You may depend on it that I shall not leave the Sonnets until I have

fully unfolded my new Theory and done that for it which shall ultimately

establish it as the true and only rendering. I am quite confident of

being able to prove that Southampton was the real begetter; that he was

the Man of whom Shakspeare says ‘sing to the ear that doth thy lays

esteem’, and calls himself one of his two poets; that a large number of

the Sonnets are written dramatically for Southampton at his request—see

Sonnet 39 … I am able to shake the personal theory into tinder. I

was of course very limited and confined in my Article; in fact had to

struggle. But, I shall have scope in my book. Meanwhile I am willing to

offer £100 to any one who will furnish me with such a refutation of the

hints given in my article as I shall be unable to refute. I shall

be glad if you or any of your friends will take it on … The Note on Dyce

was the Editor's. They are personal friends.

On November 30 he outlined his current progress to Halliwell,

pressing for more information:

I want to get a week in London this Winter for the purpose of

replying to Books on my Shakspeare subject. Can you help me at

all? By pointing out the Writers on the Sonnets—Is Mr. Correy's

List complete?—and by telling me where I can trace Southampton and Wm.

Herbert. I shall want to make a sketch of these two—also of Lady

Rich, and, if anything be recorded besides what I found in Rowland

White—of Mr. Vernon. I have got on nicely with my Theory. I

now believe that the ‘Will’ of the latter Sonnets was Herbert.

There is proof in Sonnet 152 that it was not Shakspeare—not a married

man. And, I take it that Sonnets 57 and 58 belong to this series …

I am now satisfied that Thorpe dedicated to the only ‘obtainer’ of these

Sonnets. Can you help me to prove it. He was rather a quaint

man, I think, and it sounds to me rather Chapman-like to use ‘begetter’

in that sense … [11]

It was fortunate for Massey that no serious attempt at a

refutation of his developing theories was made in order to claim his

£100, which he certainly did not possess. In November he had again

to make an application for a grant from the Royal Literary Fund.

In his letter he told them that the autobiography which he had been

preparing had been destroyed:

My special cause of appeal on the present occasion is a sad

misfortune which occurred to me some time ago. For these three

Winters past, I have been totally unable to leave home for the purpose

of Lecturing and so have been deprived of some £200 a year. This

last year I thought to publish my lectures with some other literary

matter, when, in one of her mental aberrations, my Wife destroyed a mass

of my papers, including the flowers of my Lectures, plots, articles &

the Notes of an Autobiography. This was a sad blow, and unless you

should be able to extend your kindness to me I am afraid that my

Household goods must be sold this Christmas …

Following recommendations from Lady Alford and the Reverend

George St. Clair, Massey received £50.[12]

Lady Alford and Lord Brownlow were very sympathetic to

Massey's predicament, his wife's ill health and the unfortunate

circumstances which the family had endured for the past ten years.

About the spring of 1865 they offered them a rent-free cottage in Little

Gaddesden, in an area known now as Witchcraft Bottom. At the same

time they settled some outstanding debts, caused to some extent by

Rosina's alcoholic addiction. That move was followed a few months

later by the gift of a rent free large farmhouse, Wards Hurst at

Ringshall, part of the Ashridge estate.

The arrival of the Massey family in Little Gaddesden caused

considerable excitement in that small community, particularly on account

of the rather awesome Rosina, who was still suffering from occasional

mental imbalance. While the Masseys were at Witchcraft Bottom, a

small boy happened one evening to be passing the cottage where, to his

horror, he saw Rosina with her hands outstretched, some cups and saucers

on the table apparently moving without human contact. Whilst we

know today that Rosina was practising a form of ‘ouija board’ reading,

stories spread around that must have been 'devilish' in nature.

Another incident occurred when a servant girl asked leave to visit her

sick mother in Aldbury, a village some two miles away, and was told by

Rosina that there was no need for her to make the journey, as she could

bring her mother to her. The girl then ‘saw’ her mother on her

death bed. On arriving at Aldbury, she found that her mother had

indeed died that day. With a few more embroidered supernormal

incidents, poor Rosina was branded a witch, and accepted as such by the

community, the stories later woven into local folk history.[13]

The family received additional attention when Rosina's brother, Joseph,

made the occasional visit to the village. Joseph was ten years

younger than Rosina, and had been born with a severe club-foot

deformity. This made him an invalid, requiring the use of crutches

to get around. As an additional focus of attention, he had to wear

a large white strap around his neck to support the afflicted foot.

Prior to Rosina's mental and alcoholic afflictions, she was

highly regarded in London during the late 1840s and early 1850s on

account of her clairvoyant faculties. Even during her years of

affliction she had periods of apparent normality. Massey told of

one instance while he and Rosina were washing up after supper one

evening, when Rosina suddenly stopped, saying that her mother had died.

At that time she was 200 miles away. The following morning a

letter arrived informing them of the fact. On another occasion she

was visited by an army officer dressed in civilian clothes, accompanied

by a friend. This officer had lost a carpet-bag, and wanted to

know if she could find the bag by means of clairvoyance. Rosina

described the bag and its contents, which included a pair of

silver-mounted pistols of Indian origin. There was also another

object which she could not clearly identify, until she suddenly noticed

that the officer was wearing an artificial arm. His own arm had

been severed in action, and was in the missing bag. Although

Massey and the officer travelled to Liverpool where the bag had been

presumed lost, the police considered that there was insufficient

confirmation for them to proceed with an inquiry. From all the

accounts cited, the clairvoyant episodes were mainly of a non-predictive

nature, events either happening in the present, or had occurred in the

recent past. However, in one exception, Rosina 'saw' the servant

breaking the centre pane of a window a few hours before she had actually

broken it.[14]

Literary output was very small during 1865, most of Massey's

activities being directed toward the preparation of his work on

Shakespeare's Sonnets. Rosina was strongly opposed to the time

being taken in writing the book, on the grounds that her husband might

have been employing himself more profitably. In stating that

opinion, she was probably correct at that particular time! He

wrote only one review for the

Athenæum that year,

Duchess Agnes, &c. by Isa Craig,

winner of the Burns Centenary

Competition six years earlier. Massey thought that the verse

presented in that volume would certainly give her a place among the

sisterhood of living singers, the book containing much better poetry

than the Burns ode, which was

considerably strained and flamboyant.[15] An

article ‘Browning's Poems’ which

he submitted to the Quarterly Review, was an enlarged and recast

version of the review he had written the previous year. Still

admitting to the difficulty of understanding his poem ‘Sordello’, Massey

believed that Browning was not one of the ‘serene creators of immortal

things’ when he composed it, as it represented confusion of the ‘mental

workshop’. Although Browning may have known his own meaning, it

had not been conveyed to us. He noted that most of the nineteenth

century poetry had been so far mainly subjective, having lost the secret

of the old dramatists. The objective poetry of simple description,

broad handling and portraiture had passed away with Scott. Browning was

dramatic, down to his smallest lyric, and it was necessary to understand

the principles of his art before being able to interpret his poems

correctly. The subject and character were treated in a manner

totally new to objective poetry. Closeness of observation,

directness of description made for fidelity of detail which, at first

sight, is somewhat bewildering. His ‘obscurity’ was due less to

poetic incompleteness, than arising from the dramatic conditions.

But, he said, it breathed into modern verse a breath of new life.[16]

Wards Hurst farmhouse is a large fairly isolated building,

bordered on one side by Ashridge Forest and with views to Dunstable

Downs on the other. The arrival of the Masseys from Witchcraft

Bottom was instrumental in producing some previously unrecorded

phenomena of a poltergeist nature; they had not been at Wards Hurst long

before peculiar noises were heard in the night. Sounds resembling

the ring of the kitchen range continually being thrown down, and a metal

object falling on the floor disturbed them. On some nights the

noises were sufficiently loud as to keep their Scottish housekeeper

awake, but nothing was found to be disturbed when they went to

investigate. This gave Massey considerable concern, as he had no

wish to be driven out of a rent free house by ghostly phenomena.

Rosina, who in spite of her mental episodes still possessed her psychic

faculties, supplied the information that the phenomena were connected

with the spirit of a man who had murdered his illegitimate child, and

buried it in the garden. But on his way to bury the body, in the

dark he had dropped the door key in the cellar. Subsequently

Massey did find some human child's bones under a tree in the garden, and

a rusty key in the cellar. On promising to pray for the departed

spirit of the murderer, the noises ceased and were not heard again.

Massey claimed later, that he had received valuable information via

Rosina which assisted him in his Shakespeare research; she had provided

references to books about which they both knew nothing, but that were

relevant to the development of his theories. However, it was not

suggested that the spirit of Shakespeare was responsible for this

information!

Wards Hurst Farm.

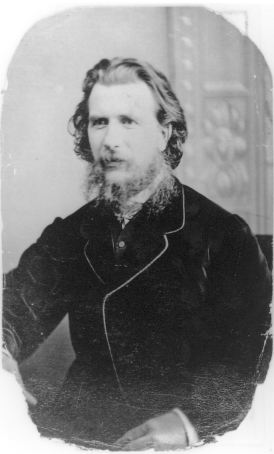

Gerald Massey, early 1870's.

(The Hulton Picture Company)

By October, Massey had completed his book and even prior to

publication was attempting to interest Ticknor & Fields, and Osgood in

Boston, for an American issue:

Octr./65.

My dear Fields,

You will remember that in my dedicatory notes to you I disclaimed being

a Man of Works. Now however, I do think I have done a work, the

best I am likely to do and one that will live. I do not hesitate

to say the Sonnets are settled once and for ever and the Book will read

like a sunrise … The work will run to 400 or 500 pp and is wrought

elaborately. To sell them at a guinea I expect Longmans will take

it; I am now negotiating with them. Will you take it over the

water? If so, I'll send sheets as printed. You may have

faith in it I assure you. It has the elements of a great

sensational success … [17]

Decr. 1st.

I have received your Note per favor of Messrs. Longman. Ticknor &

Fields have republished my poetry and I was looking to them to reprint

my new work on Shakspeare. It may be however that it will not be

so much in their line … I shall ask £100 for the republishing … Whoever

takes it will make a good thing of it … I anticipate a great success in

England, a greater still in America. It cannot fail to create a

sensation …

Wm. J. Niles Esq[18]

The following year, 1866, marked the beginning of a personal

change in Massey's life following the death of Rosina aged 33, on 13

March. According to one account, Rosina prepared her coffin, which

had been in the house for some time. She took a candle, a penny

and a hammer … the candle to light her way through the darkness,

the penny to pay her toll, and the hammer to knock upon the doors of

heaven.[19] This unlikely story, knowing the

Masseys' beliefs, was probably attributed to Rosina as it was apparently

a local custom at that time. Massey's account of Rosina's death

was given later. She had turned on her left side in bed and they

were both talking to each other. It was when Massey received no

reply, that he realised she was dead. On his first séance with the

medium D. D. Home, a spirit purporting to be his wife said, ‘Oh, Gerald,

when I turned on my left side to pass that night, and had got through, I

could not believe it. I kept talking, and thought you had gone

suddenly deaf, as I could not hear you answer me.’ Massey

considered that this episode represented the continuity of consciousness

in death. There is no death. There is no break—no cessation

of motion: it is like the top when we say it sleeps—that seems to stand

still when it spins perfectly.[20]

According to the death certificate, Rosina died from ‘Morbus

Cordis’— heart disease, but there is no indication of the underlying

cause, or of tuberculosis, which had been considered earlier. She

is buried in the churchyard of the beautiful and secluded Saint Peter

and Saint Paul in Little Gaddesden, near Tring.

|

Little Gaddesden churchyard.

Rosina's grave is first on right on entering.

Rosina's gravestone. Its badly weathered inscription reads …

TO

THE MEMORY OF

ROSINA JANE

WIFE OF

GERALD MASSEY

BORN MARCH 30 1832

DIED MARCH 13 1866

|

Up to that time Massey had received no definite indication of

any intent to publish his Shakespeare book in America, and was

beginning to have doubts concerning this. Hence he wrote again

to enquire:

March 14

My dear

Fields,

There has been a misunderstanding between me and the Agent of

Roberts Brothers and I have sent the first parcel of sheets to

you by Book-post. Getting on for 2/3rds of the Book.

You will read the sheets please and if you do not care to

print—I cannot but think you will take to it—you will oblige me

by seeing if you can save something for me from the Pirates.

The Book is announced for the 28th Inst. in England. Do

the best you can for me. I am in sad trouble. My

poor Wife—after long, long, suffering and trials insurmountable,

is lying dead at last … [21]

The publication of his Shakspeare's Sonnets Never before

Interpreted: his Private Friends identified: together with a

Recovered Likeness of Himself was dedicated to Lord Brownlow

‘In poor acknowledgement of princely kindness’, and received

with some courtesy by the press. Commencing with a summary

of the theories to date, particularly the Personal Theory of

Charles Brown, he continued by sectioning the Sonnets into

Personal and Dramatic. His deductions, following his

previous Quarterly

Review article (Shakspeare and his Sonnets) are worked

in greater detail, and his source references are extensive.

Robert Bell while disagreeing with Massey's conclusions,

commented that ‘Whatever may be the ultimate reception of Mr

Massey's interpretation of the Sonnets, nobody can deny that it

is the most elaborate and circumstantial that has yet been

attempted.’ He referred to ‘the bolder outlines, the

richer colouring and the more daring flights’ than Armitage

Brown had given in his own essay on the subject.[22]

David Main spoke of ‘Mr Massey's masterly and luminous

exposition’, while in Hepworth Dixon's view, expressed in the

Athenæum, Massey had

‘entered into the personal and political history of Shakspeare's

time with a good deal of pains’ and had thrown out ‘some

excellent suggestions.’[23] One

Shakespeare researcher, Philarète Chasles, also writing in the

Athenæum,

complimented Massey on his eloquent and erudite pages, but noted

some very hard words that Massey had written against sceptical

critics who failed to chime in with the author's settled

opinions. Chasles, after further research, suggested that

the ‘Begetter’ of the Sonnets, ‘Mr. W. H.’, was William

Hathaway. Massey responded and, defending his argument

that ‘only begetter’ means ‘only obtainer’, asked what

historical facts and dates ran counter to his theory. He

was exceedingly perplexed as to the unwillingness of critics to

follow his reading of what he termed the Dramatic Sonnets.[24]

Although very pleased with his work, Massey must have been

disappointed that the book did not reach a second edition, and

that no publisher accepted it in America. There was one

compensation however, which Massey noted in later

advertisements, in that Professor Fritz Krauss in Germany

accepted much of his theory, and used it in his

Shakespeare—Southampton Sonnets, 1872.[25]

There is of course, continuing interest in Shakespeare's

Sonnets, albeit within more specialised frameworks of

Shakespeare societies and university English literature courses.

The research side of the subject received much attention when

computer programs were developed that were able to detect word

text blocks, pattern and rhythm of words and sentences etc.

within the Sonnets. These were able to indicate authorship

characteristics and early and late works by the same poet.

Peter Farey used a statistical approach to determine whether the

original order as printed by Thomas Thorpe (assumed almost as

Shakespeare wrote them) or if some of the other authors and

editors who considered a better sequence were more correct.

Statistical analysis showed considerable support to Thorpe's

original sequence as being nearer to the order in which they

were written, and also showing what the most probable sequence,

written over a number of years, actually is. Comparisons

were made from Thorpe's 1609 edition, with those of 19 different

authors and editors dating from 1841 to 1995. Massey's

1888 edition of his revised book on Shakespeare's Sonnets

received a high ranking. William Boyle in the Shakespeare

Fellowship's Shakespeare Matters, summarises a literary

analysis and determines that out of 1,800 books on the sonnets,

Gerald Massey's 1866/1872 Shakespeare's Sonnets … is the only

one that gets close to the true historical context. He was

also the first to identify persuasively the Earl of Southampton

as the poet's "true love" of Sonnet 107. Massey may also

have been correct in suggesting that Southampton requested that

the drama of Richard II was altered by Shakespeare on purpose to

be played seditiously, with the deposition scene (not published

until 1608) newly added. He argued that if Shakespeare was

not hand-in-glove with the Essex faction, he fought on their

side pen-in-hand. In the new scene King Richard gives up

the throne with Bolingbroke in his presence, which is what Essex

and Southampton hoped to persuade Queen Elizabeth to do.[25]

Two articles and four reviews that year completed his writing

on literary subjects and concluded his association with the

Athenæum. ‘Yankee

Humour’ was a revised version of his previous ‘American

Humour’ of 1860, in which he acknowledged a greater number

of representative authors, but again strongly favoured Lowell's

Biglow Papers as being the most characteristic and

complete expression of American humour.[26] ‘Charles

Lamb’, a lecture that he delivered many times during his

tours to universal praise, was more an appreciative biographical

sketch than a critical appraisal of Lamb's works.[27]

Although well constructed containing colourful poetical phrases,

it remained a lecture, rather than being developed as a literary

study. Not impressed by Lamb's poetry, he concluded that:

‘The most minute poring of personal affection cannot discover

anything very precious … When he wrote his verses he had not got

into that vein of incomparable humour which afterwards yielded

such riches to his essays and letters …’ Swinburne wrote

to him on 22 May disagreeing with those comments:

Of your work on Shakespeare's sonnets I read something when

it appeared, but had no time to follow it out … Hitherto

I am myself unconvinced that any of the series were written in

the character of another real person; they all seem to me either

fanciful or personal—autobiographic or dramatic. But I

hope before long to study the question started by you more

fully. I have been reading this evening your essay on Lamb

in the Fraser of this month. Will you excuse the

protest of a younger workman in the same field as yourself

against the deprecatory mention of Lamb's poetry? I

remember Tennyson speak of it in the same tone; but against both

my seniors I maintain that there are two or three poems and many

passages of serious and noble beauty besides the verses you

quote on his Mother's death. I have always thought that

but for his incomparable prose the world would have set twice as

much store by his verse … [28]

The sudden death of Lord Brownlow whose health had been

fragile for many years occurred in February 1867. To his

memory, Massey composed one of his finest poems,

In Memoriam,

‘In affectionate remembrance of John William Spencer, Earl

Brownlow’.[29]

Thomas Cooper in a letter to

Thomas Chambers, asked ‘… Have you seen Gerald Massey's lines on

Earl Brownlow in Good Words? They are very

beautiful. The best thing he ever did, in my conception

…‘[30] Following that publication

Massey reprinted the poem in a private, full leather bound

edition, dedicated to Lady Marian Alford ‘As his offering of

sympathy in the common sorrow’.

|

Why should we weep, when 'tis so well with him,

Our loss even cannot measure his great gain?

Why should we weep, when death is but a mask

Through which we know the face of life beyond? …

Why do we shrink so from ‘Eternity’?

We are in Eternity from Birth, not Death!

Eternity is not beyond the stars—

Some far Hereafter—it is Here, and Now! … |

|

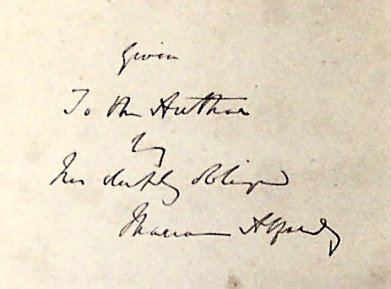

Massey's In Memoriam rebound in vellum and presented to

Massey by Lady Marian Alford.

|

It is not known if Lady Alford agreed entirely with the

Spiritualistic sentiments expressed in the poem, but she was

‘deeply obliged’ and held it in sufficient regard for her to

present the author with a vellum bound inscribed copy emblazoned

in colour with her Coat of Arms.[31]

While calling on Lady Alford at Ashridge, W. E. Gladstone was

shown the poem, who then requested that the copy be sent to

Queen Victoria. The Queen wrote in reply, ‘The Queen

returns the volume, having read and greatly admired the poem.

She would indeed be most pleased to possess a copy of it.’[32]

On 2 August Thomas Cooper wrote again to Thomas Chambers, making

a probable reference to his privately printed volume, which had

not been reviewed. ‘… Is Gerald Massey's new poem really

out? I never see any review of it, or any extract from it.

They will break his heart if they do not quote him & praise him.

He cannot live without praise, poor fellow …’[33]

|

|

|

Lady Marion Alford, c. 1870 -

cdv signed Flli. D' Alessandri, Roma. |

Massey was now left with two children to bring up.

Although Christabel, the elder, was fourteen, and he employed a

housekeeper, his lecture tours became a necessity for financial

reasons, and these would require long periods away from home in

the winter months. In her autobiography

Recollections of

Fifty Years, the poetess and author

Isabella Fyvie Mayo

recounts that Massey offered his hand to the poetess

Jean Ingelow. But, as

events transpired, on 2 January 1868 in St. Mary's Church,

Paddington, he married Eva Byrn, who was one year younger than

the late Rosina. Eva, who had received a French education,

was the daughter of Charles Byrn, an artist and ‘Professor of

Dancing,’ in Cambridge Street, Paddington. She appears to

have made no notable impact on Massey's life, apart from

providing a secure stable family environment, so sadly lacking

during his marriage to Rosina.

Since 1854 when he had tried to sustain Samuel Smiles' brief

interest in commencing a London newspaper, Massey had hoped,

despite his experiences in Edinburgh, that some similar venture

would appear in which he could participate. From literary

acquaintances he heard that the poet and novelist George

MacDonald might be favourably disposed to such a suggestion.

Writing to MacDonald, he mentioned his Shakespeare book, and

then asked quite directly, '… Have you any thoughts of a

Magazine of your own? I have long had, tho' I have never

sought to realise them. Do you think there would be a

chance of our working together with one? …'[34]

But this was another of Massey's optimistic hopes that never

materialised. A few years later from 1872-3, MacDonald

became editor of Good Words for the Young, while Massey's

plans had again changed direction.

In June 1868, in honour of the marriage of John William

Spencer's successor and brother, the Rt. Hon. Adelbert-Wellington

Cust to Lady Adelaide Talbot, 3rd daughter of the 18th Earl of

Shrewsbury, Massey composed a cycle of poems,

Carmina Nuptialia,

which he dedicated to Lady Marian Alford and the married couple,

the new Earl and Countess Brownlow. Again privately

printed, the poems were mainly sentimental love lyrics,

philosophically idealistic, with some religious and

Spiritualistic overtones:

|

Now pray we.

Lord of Life, look smiling down

Upon this pair; with choicest blessings crown

Their love; the beauty of the Flower bring

Back to the bud again in some new spring!

We would not pray that sorrow ne'er may shed

Her dews along the pathway they must tread:

The sweetest flowers would never bloom at all

If no least rain of tears did ever fall.

In joy the soul is bearing human fruit;

In grief it may be taking divine root.

Come joy or grief, nestle them near to Thee

In happy love twin for eternity! |

The same year was noted in the extramundane realm for the

case of Lyon v. Home. Daniel Dunglas Home was the famed

Victorian physical medium immortalised unfavourably in Robert

Browning's 'Mr Sludge, the Medium' in 1864. Browning,

interested in the phenomena, previously had a séance with Home

but disapproved of the discourses given in trance.[35]

Home was on no occasion detected in fraud, and was fully

investigated some years later by Sir William Crookes, the

accuracy of his scientific experiments never receiving serious

challenge.[36] Mrs Lyon, a wealthy

widow, was attracted to Home, and was prepared to settle

£24,000, and later a further £30,000, on him if he were to add

her name to his, as an adopted son, and make it Home-Lyon.

After this had been done, Mrs Lyon changed her mind, and sued

for recovery of the money. She based her action on a

statement that she had been influenced by spirit communications

from her late husband, coming through Home, despite telling

people, including Massey, that she had not been thus influenced.

Home found out, too late, that Mrs Lyon was flighty, obstinate,

fond of her own way, apt to change her mind, and tyrannical.

Massey declared that he would not have stood for it for £30,000

a year! She had informed various people how she had to

urge Home to take the money, and also told Massey in January

1867 how delighted she was at seeing Home's astonishment when

she made her proposals, her gifts being so unsought and

unexpected.[37] In consequence of this

action, in common with a number of other notable persons such as

Cromwell Varley FRS.,[38] Massey made

an affidavit in Home's favour:

I, Gerald Massey, of Ward's Hurst, Ringshall, Hemel

Hempstead, in the County of Herts, author, make oath, and say as

follows:

On the 28th of December, 1864 I met Mr Home and Mrs. Lyon for

the first time. It was at the house of Mr. & Mrs. Samuel

Carter Hall. Since then I have seen a great deal of Mr

Home, and have never had the slightest reason to look upon him

other than as a man of the most honourable character and

kindliest disposition—in fact, a gentleman whom I should judge

to be quite incapable of any such baseness as has been laid to

his charge.

Gerald Massey.

Following a lengthy trial, Home was found guilty, despite

undisputed evidence that Home did not exercise undue influence

over Mrs Lyon. The judge's final comment showed extreme

bias, ‘Nevertheless, I decide against him; for as I hold

Spiritualism to be a delusion, I must necessarily hold the

plaintiff to be the victim of a delusion, and no amount of

evidence will convince me to the contrary.’ Mrs Lyon, on

‘adopting’ Home, had taken possession of jewellery that had

belonged to Home's wife, much of which was never recovered.

'The Great Spiritual Case', Lyon v. Home, (Illustrated Police

News office, London, 1868, 24-25) adds more detail.

Massey was involved in a further unusual discussion during

the summer of 1868. On this occasion the authenticity of a

poem was in question, "An Epitaph", discovered penned on the

reverse of the final page of a volume of Milton's Poems both

English and Latin held in the British Museum. Its finder

attributed this previously unknown poem to John Milton, an event

that caused widespread interest in the press. Between 16

July and 11 August, correspondence on the subject appeared in

The Times, Telegraph, and other national newspapers.

After much debate—not all of it friendly—involving some

well-known literary personages, matters appear to have been

drawn to a close with a letter from Massey to the Editor of the

Pall Mall Gazette. Massey's finely argued verdict

was that the poem owed more to the style of Crashawe than of

Milton, but was by neither and might have been intended as a

forgery. (Appendix C.)

During the period 1868-69, recommencing his winter

lectures—he was at Stranraer in December 1868 giving his talk on

Thomas Hood—Massey was more firmly and openly aligning himself

on the side of the Spiritualists. This received public

attention with his next volume of poetry, A Tale of Eternity

and other Poems. Published in January 1870, it gave a

dramatic account of his experience and investigation into the

poltergeist type phenomena at Wards Hurst, some six years

earlier. Charles Kent, editor of the Sun, referred

to it [A Tale of

Eternity] as the most remarkable of all his productions,

and ‘beyond what we had regarded as the range of Mr Massey's

capacity … Weird, grisly, eerie, eldritch horror runs through

the whole current of the narrative … Despite blemishes of

thought and expression … and the tone of the poem verging at

intervals towards the blasphemous … Gerald Massey has evidenced

a wealth of vocabulary and a force of imagination far beyond the

reach of any mere versifier … Seldom has a young poet of the

large promise of Gerald Massey more fully justified than he

himself has done in the present instance …’[39]

Kent, for religious reasons, judged the work to be ‘clouded and

misted over with the hazy influence of what is called

spiritualism’, but did not denounce the poem on that account, as

others might have done.

The Athenæum was very slow in publishing its review,

and Massey, always impatient, could not resist writing to the

proposed reviewer, Thomas Purnell:

Ward's Hurst,

Ringshall,

Hemel Hempstead.

Saty.

Dear Mr.

Purnell,

I have sent, per Evans, a batch of my very best pickings which

will afford you ample choice for quotation without your tearing

up your Copy. I have forgotten your number or should have

sent direct. Curiously enough I had corresponded with the ‘Athm.’

people about resuming my old seat on their Critical bench.

But, after one meeting and your communication, I shall drop the

subject and not ask for any Books. The whole affair is

infinitely funny. I say old fellow, if you let that Book

of mine lie there another week, and I die first I'll haunt you.

Remember me to your Sister.

Yours faithfully,

Gerald Massey.[40]

After some further delay, the published review was politely

appreciative and more formal in tone than the Sun.

Purnell admitted he had been initially puzzled by the whole

poem, believing that readers would approve more of the

succeeding verse, which included ‘In Memoriam’ and ‘Carmen

Nuptiale.’

The plot is of the slightest texture; its

theme is remote from ordinary human interests; the whole story

occasionally drags; and more than once we fancied ourselves on

the border-land of the grotesque … [But] it is higher in aim,

broader in scope, and contains passages of sustained power … The

theories of Swedenborg, Böhmen and others of the illuminati have

apparently been utilized by him, and he shows an extensive

acquaintance with the results of modern science … there will be

no disagreement about the value of the poetry … [41]

|

It was an awful hour of storm and rain

And starless gloom in which the Child was slain.

Wild, windily the Night went roaring by,

As if loud seas broke in the woodlands nigh …

He had dug his grave amid this war of storm;

He bore the murdered Babe upon his arm

For burial, where no eye should ever mark!

Just then Heaven opened at him with a bark

Of all the Hell-hounds loosed. And in the dark

Out went the light, and down he dropped the key …

He was alone with Death, and paces three

Beyond the door an open grave gaped, free

For all the daylight world to come and see …

He ventured: bravely dashed the weapon down,

And turned to triumph, when, by the student-gown

He was held fast, as if the living Tomb

Had closed upon him; clutched him in the gloom.

He had pinned his long robe to the coffin!

The murderer did not madden thus, but he

Was stamped as if for all Eternity … |

Prior to the published edition, Massey had sent a

subscription copy to Matthew Arnold who, in a private letter

dated 19 December 1869, commented that:

Strahan brings you out at rather a formidable moment in

conjunction with Tennyson, whose new volume calls to so many

readers and buyers. I do not myself think, however, that

in this new volume of his he proves—except for the first moment

of publication—a dangerous competitor.

Ever sincerely yours, Matthew Arnold.[42]

Following the review in the Sun, he wrote in reply to

a note from Samuel Wilberforce to whom he had sent a copy of his

book:

I am afraid my long poem will prove a stumbling block to many

of the Critics. It is founded on a fact and is the result of an

experience remote from the Common. Nearly 20 years ago

your Lordship saw my Wife that then was show something of

psychical phenomena. This poem of mine is the latest

result of my living for many years face to face with a life

mystery.

A Writer in the Sun—a Mr. Kent, who is a R. Catholic

seems to think the poem not very orthodox but I claim for it

that it is on the side of Belief and Positivism and was written

with that fully in view. Also, it ought to tell against

Child-Murder, I think. Anyhow I hope it may not be made to

stand in the light of a poem like my ‘In Memoriam’ written on

the death of the late Earl Brownlow. For love of him and

his Mother I would do much to get that poem largely

recognised—especially after the decision with regard to

Berkhamsted Common.

I am

Your Lordship's Grateful

Gerald Massey.

P.S. The Notice enclosed—from the ‘Sun’—does an injustice to

Wm. Strahan thro' a mistake—the Copy sent to him was the same as

your Lordship's—in Quarto—but the one issued for the public is a

smaller size—in Crown.[43]

There is no record of Wilberforce's private or public

experience of Rosina's clairvoyance, which would have been

between 1851-4. Wilberforce was not completely alien to

this type of phenomenon, having had an experience in 1847,

concerning one of his sons. While in his library at

Cuddesdon with three or four of his clergy writing with him at

his table, he suddenly raised his hand to his head, and

exclaimed, ‘I am certain that something has happened to one of

my sons.’ He found out later that his eldest son, Herbert,

who was a naval midshipman at sea, had at that same time

received a severe crushing accident to his foot. In a

letter to Miss Noel, dated 4 March 1847, Wilberforce wrote, ‘It

is curious that at the time of his accident I was so possessed

with the depressing consciousness of some evil having befallen

my son Herbert, that at last on the third day after, the 13th, I

wrote down that I was quite unable to shake off the impression

that something had happened to him, and noted this down for

remembrance.’[44] Previous to this, he

had experimented with mesmerism, with some success, writing that

‘I am very deep in mesmerism … I sent two into a deep sleep, one

instantly, and one soon.’[45] Later,

about 1852, Lord Carlisle, commenting on one of the private

literary breakfasts that Wilberforce held quite often, wrote in

his diary, ‘The Bishop and I fought a mesmeric and

electrobiological battle against the scornful opposition of all

the rest.’ The ‘others’ being Macaulay, Lord Overstone and

Sir G. C. Lewis.[46] In 1859 due to

reports of his continuing interest in psychic phenomena,

Wilberforce had to write a disclaimer in a letter concerning his

activities in that direction:

You have been misinformed as to the fact that I practise

Table Turning. When the existence of such a power was

first announced as an electrical phenomenon, I in concert with

many others, tried whether the fact was so. But no table

turning followed my manipulation …

In order to emphasise his official orthodox position, he

added, ‘I should say that it [table turning] was the work of the

Evil Spirit …’[47]

[Chapter 6]

|

|

NOTES |

|

1. |

This

theme is dealt with in Politics and Reviewers: The Edinburgh and

the Quarterly in the early Victorian age, by Joanne Shattock.

(Leicester U.P., 1989). |

|

2. |

Athenæum, 7 Mar. 1863, 328. |

|

3. |

Ibid.

25 Jul. 1863, 106–108. Massey had suggested in a letter to

Jean Ingelow—20 July 1863—before

the Athenæum review was published, that she send her

Poems to his American

publisher, Ticknor and Fields of Boston for their consideration, in

order to prevent piracy. (Roberts Brothers Collection, Massey to

Jean Ingelow, The Watkinson Library, Trinity College, Hartford).

The fact that Ingelow's Poems was published by Roberts

Brothers rather than Ticknor & Fields led some to suppose that her

book had been 'pirated' by Roberts as Massey had feared.

However, recent research by Maura Ives ('Her life was in her books.

Jean Ingelow in the literary marketplace.' Victorian Newsletter,

22 March 2007) strongly suggests otherwise. Ingelow had

contacted Ticknor & Fields, sending them a copy of her book, and it

appears likely that they—or less likely Massey or Ingelow herself,

had then contacted Thomas Niles, [previously from Whittemore, Niles

and Hall] an editor for Roberts Brothers. Due to Massey's

popularity in America, some there believed him to be an American

(anecdote in Lucifer, Sept. 1888), a mistake that might

equally have come to apply to Jean Ingelow! |

|

4. |

He had,

possibly as early as 1862, obtained a Reader's Ticket for the

British Museum Reading Room—now the British Library. In December

1864 he recommended an application for a ticket for a friend.

British Library Add. Mss. 48340.f.300. |

|

5. |

Athenæum, 3 Oct.

1863, 425-27. |

|

6. |

‘Thomas

de Quincey—Grave and Gay’ North British Review, 39, (Aug.

1863), 62-86. ‘The Life and

Writings of Thomas Hood’ Quarterly Review, 114, (Oct.

1863), 332-68. |

|

7. |

Ibid.

115, (Jan. 1864), 42-68. |

|

8. |

Athenæum, 4 Jun. 1864,

765-67. |

|

9. |

Critical article—‘Robert

Browning's Poems’—published in the Edinburgh Review, Oct.

1864, 537-65. Massey's retort,

published in The Reader, 26 Nov. 1864, 674-5. |

|

10. |

Quarterly Review,

115, (Apr. 1864), 430-81. Massey's spelling of Shakespeare as 'Shakspeare'

followed that of Ben Johnson's 1623 'To the memory of my beloved

Master William Shakspeare.' The spelling was also used by Walter

Savage Landor in his 'Citation and Examination of William Shakspeare',

1834. Several variants of the name have been used, and although all

are valid, the usual 'Shakespeare' is most favoured. |

|

11. |

Halliwell Mss in Edinburgh University Library. |

|

12. |

Royal

Literary Fund, File No. 1581. |

|

13. |

Bell,

V., Little Gaddesden (London, Faber, 1949), 131-34. The

servant's name is not given. In the census return for 1871, Wards

Hurst, he was employing Maggie Ogilvy, then aged 30 years from

Chesham as a General Servant, and Sarah Staple, 15 years, from

Scotland, as a Nursemaid. By that date his family had increased. |

|

14. |

These,

and a number of other incidents, are recorded in the Spiritualist,

15 May 1972, 36, and more fully in the Medium and Daybreak,

17 May 1872, 177-79. |

|

15. |

Athenæum, 14 Jan. 1865,

49-50. |

|

16. |

Quarterly Review, 118,

(Jul. 1865), 77-105. |

|

17. |

The

Huntington Library, San Marino. Mss. HM. FL3293-99. |

|

18. |

Ms. The

Library of Congress. William J. Niles was a brother of Thomas Niles,

of Roberts Brothers Publishers. |

|

19. |

Bell,

V., Little Gaddesden, op. cit. Bell states, p. 134,

incorrectly, that ‘On the 3 May 1866 she prepared her coffin … ’ |

|

20. |

Banner of Light, 10 Jan. 1874, 1. |

|

21. |

The

Huntington Library, San Marino. Mss. HM FL3293-99. |

|

22. |

Fortnightly Review, 5, (Aug. 1866), 734-41. |

|

23. |

A

Treasury of English Sonnets (London, Blackwood, 1880), 279-80;

Athenæum, 28 April 1866. |

|

24. |

Athenæum, 16 Feb. 1867,

223-4., 16 Mar. 1867, 355-6. |

|

25. |

Krauss,

Fritz, Shakespeare's Southampton-Sonnette (Leipzig, Englemann,

1872), 5-13.

Shakespeare's Sonnet Sequence: A statistical approach

to determining the order in which they were written. Peter Farey,

1998. See: (www2.prestel.co.uk/rey/sonnets.htm).

'With the Sonnets now solved ...' in William Boyle,

Shakespeare Matters, (The Shakespeare Fellowship). vol. 3, no 4,

Summer 2004 pages 11, 17, 18, 21.

'A Critique of

Massey's Shakespeare Sonnets' an essay by E. Wingeatt mentions Massey's often lack of adequate referencing and

sometimes using subjective inferences rather than objective facts.

Many of his conclusions, as with most recent authors on the subject,

tend to be essentially more subjective and less strictly

evidentially based. See also p. 230 fn. 3. |

|

26. |

Quarterly Review, 122, (Jan.

1867), 212-37. |

|

27. |

Fraser's Magazine, 75, (May

1867), 657-72. |

|

28. |

Ms.

University of Texas. Goss, E., Wise, T., The Letters of Algernon

Charles Swinburne 2 Vols. (London, Heinemann, 1918), I, 63-4,

letter 33. |

|

29. |

In

Good Words, 1 Jun.

1867, 273-4. |

|

30. |

Ms.

Bishopsgate Institute, dated 20 Jun. 1867. |

|

31. |

Deposited at the Local History Unit, Upper Norwood Library. |

|

32. |

Medium and Daybreak, 10 Oct. 1873, 451. A copy exists of

In Memoriam that

was inscribed by Lady Marian Alford and sent by her to Lady Gertrude

Talbot (1840-1906), the 3rd daughter of the Earl of Shrewsbury, and

dated 1869. |

|

33. |

Ms.

Bishopsgate Institute. Massey was always sensitive to criticism, and

adverse comments produced self-doubt and depression, particularly

when he had to rely on popularity for his living and family support.

He usually countered criticism by a strong literary response,

sometimes to the point of discourtesy. |

|

34. |

Aberdeen University Library, Ms. 2167/1/18. Undated. |

|

35. |

Through a Glass Darkly. Spiritualism in the Browning Circle.

Katherine H. Porter, (Univ. Kansas Press, 1958. New York, Octagon,

1972), 47. |

|

36. |

‘Experimental Investigation of a New Force,’ in Quarterly Journal

of Science, 8, (Jul. 1871), 9-43. ‘Notes of an Enquiry into the

Phenomena called Spiritual’, 11, (Jan. 1874), 81-102. Prior to this,

his authority was unquestioned. After his affirmation that the

phenomena were genuine, he was doubted, questioned and criticised. |

|

37. |

Home,

Mme. D., D. D. Home. His life and Mission (London, Trubner,

1888), 252-74. Also Home, D. D., Incidents in my life

(London, Tinsley, 1872, 2nd series), 193-374 for an account of the

court case. The Great Spiritual Case, Lyon v. Home at

Cambridge University Library, Pam.5.86.29. See also Elizabeth

Jenkins' The Shadow and the Light. A defence of Daniel Dunglas

Home, the Medium (London, Hamish Hamilton 1982). |

|

38. |

Spiritualist, 1 Sep. 1873, 307. |

|

39. |

Sun,

28 Jan. 1870, 2. |

|

40. |

Source

personal. Ms. deposited at the Local History Unit, Upper Norwood

Library. Massey had not reviewed for the Athenæum since 1867.

His friend and chief editor, Hepworth Dixon, had left in 1869 when

Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke obtained the Athenæum following

the death of his father, the previous owner. Dixon was succeeded in

1870 by Norman MacColl. Both were responsible for changes in policy,

but the reason why Massey was not reappointed is not known. See The

Athenæum. A Mirror of Victorian Culture, by Leslie A.

Marchand. (New York, Octagon, 1971). |

|

41. |

Athenæum, 9 Apr. 1870, 476. |

|

42. |

Cited

in My Lyrical Life,

l, ii. Tennyson's poem was his Holy Grail. |

|

43. |

Bodleian Library, Ms. Wilberforce c.16. fols.190-93. Dated 3

February. Purnell in his review commented on the unusual size of the

book, which had been issued as a subscription edition. He should

have been sent the smaller, published edition. Earl Brownlow, prior

to his death, had clashed with the Berkhamsted Commoners over

encroachments of common land. |

|

44. |

Report

of the Literary Committee of the Society for Psychical Research,

Proceedings, 1882, I, part 2, 133. |

|

45. |

Wilberforce, Reginald, The Life of the Right Reverend Samuel

Wilberforce D.D. 3 vols. (London, Murray, 1881) 1, 259-61. |

|

46. |

Ibid.

2, 7-8. |

|

47. |

Ibid.

2, 425. |

|