NOTES AND

EXTRACTS

ON THE HISTORY OF THE

LONDON & BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY

CHAPTER 6

THE PROJECT

INTRODUCTION.

|

|

“In the flattering endeavour of his several

biographers to make out Robert Stephenson an infallible pattern

of universal excellence and genius, positive injury has been

done to his genuine merits, and controversies necessitated that,

had sober truth alone been told, would never have been referred

to. Stephenson’s great superiority was as a leader of men. We

see the same genuine mastery . . . . in his command of the

multitudinous details of the London and Birmingham office at the

Eyre Arms, and the creation of the system of plans,

specifications, contracts, and so forth, now become common

property for the railway engineer; and in the general career and

success of his life, in council, before committees, in the

management of boards, in the homage and zealous support of his

pupils and staff, and in the honest freedom of his life from a

single slur or stain.”

The Practical Mechanic’s Journal,

edition April 1866 – March 1867.

[1]

|

|

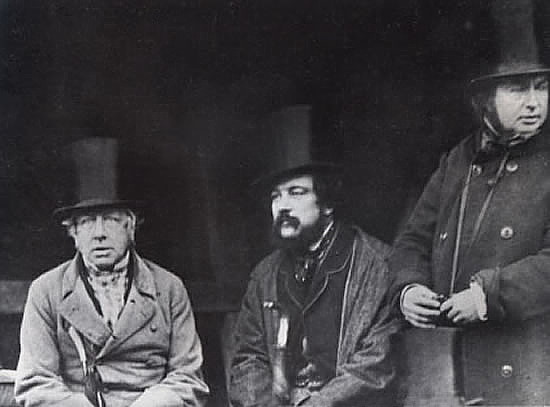

Robert Stephenson

F.R.S., Civil Engineer. |

|

A civil engineering project is a

temporary collaborative enterprise, set up to achieve a

particular aim within the built environment [2]

subject to the

usual constraints of time, cost and quality.

Broadly speaking, a transport infrastructure project,

such as the London and Birmingham Railway,

moves through a number of phases towards completion, usually

with some degree of overlap and iteration between each:

-

Initiation: Project Manager and Client agree on the

project’s

deliverables.

-

Outline plan: initial surveying and

the identification of the most suitable route.

-

Legislation: obtaining the necessary legal powers in

the form of a private Act of Parliament.

-

Definition: defining in greater detail what the

project is to

achieve, out of which comes a schedule of requirements.

-

Preliminaries: preparing detailed

designs and specifications.

-

Preparation: addressing the many and varied legal

issues.

-

Implementation: staking out, building and commissioning the line.

-

Handover: after some form of acceptance testing the Client takes possession

and the project is closed.

In its day, the construction of the London and

Birmingham Railway was the largest civil engineering project yet

undertaken. Its aim was to create a public railway along a

route sanctioned by Parliament, to be

achieved within a budget £2,500,000 (Appendix I.) for delivery

late in 1837. [3] The project would require a team of

suitably experienced people

to manage it; the preparation of a great number of plans, drawings,

specifications and contracts; the resolution of legal issues (involving,

for example, land

purchase, conveyancing, contractual matters, compensation for

damage and the diversion of roads and rivers); the supervision of

contractors; and, throughout, accurate accounting and strict financial control. Over the five years that the work took to complete,

maintaining steady progress was to be a continual problem for

the Board and their Chief Engineer, and some deviation

from the project’s original goals was inevitable.

Large-scale civil engineering projects

have always had a tendency to depart from their designers’

estimates of cost and delivery date, sometimes seriously, particularly when they are

of a type that hasn’t previously been attempted. In an earlier age, the

Manchester Ship Canal, at £15,000,000, was almost three times

over budget and two years late in opening. The

London and Birmingham Railway’s near

neighbour for many miles, the Grand Junction Canal, was delayed by almost five years through serious

flooding in the workings of the Blisworth Tunnel, the Canal’s eventual cost being three times the

original estimate. In our own age the Humber Bridge, the

Jubilee Line extension, the Channel Tunnel and the Channel

Tunnel Rail Link (HS1) are just some examples of civil

engineering projects that failed to meet their forecasts for one

reason or another, and the Edinburgh Tramway project ― currently

some £200m over the original £375m budget, and five years late ― looks set to join them. Transport infrastructure

projects such as these attracted much

concern among their investors, which in our own age is usually the taxpayer.

If the out-turn for large-scale civil engineering projects

can still depart seriously from forecast, it is unsurprising

that the London and Birmingham Railway, a trailblazer in its

day, was no exception:

“The way in which these things are usually got up for

Parliament is so vague and undetermined, as to merit no other

name than a guess, and not a good one either; hence has arisen

the common saying with all great undertakings of this kind,

‘halve the receipts and double the expenditure if you wish to

know anything about it’.”

[4]

The History of the Railway

connecting London and Birmingham, Lieut. Peter Lecount R.N.

(1839).

――――♦――――

THE MANAGEMENT STRUCTURE.

Although the London and Birmingham Railway Act

passed into law on 6th May 1833, a year was to elapse before the

first construction contracts were let and building commenced. That does not mean that little was done in the intervening

period ― on the contrary, a great deal was done.

Railway engineering has grown into a

multi-faceted discipline that includes, among other things, civil

engineering, mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, and information and communications technology. When the London and

Birmingham Railway was built, its construction was entirely a matter of civil

engineering, a discipline that then covered not only the design,

construction and maintenance of cuttings, embankments, bridges,

tunnels and a range of buildings, but track, signalling and

rolling stock. [5]

The delivery of these components

− locomotives being an exception − fell to Stephenson’s team. Each needed

to be planned and designed, and their construction managed to ensure

that they were

available when required, to specification and at the agreed price. But before any detailed planning could take

place it was first necessary to set up a structure for managing

what for its time was a huge project, and to recruit the engineers

and draughtsmen who were to produce the designs and specifications

and oversee their realisation. The management structure that

Stephenson put in place was much the same as would apply to a

similar project today.

|

.jpg) |

|

George Parker Bidder

(1806–1878),

assistant to

Robert Stephenson. |

From an early date in its history, the Board had divided the line into

two equal sections, each under the direction of a committee, one

based in London and

the other in Birmingham. Under the Board came their Chief

Engineer, a role to which Robert Stephenson was appointed on the basis that “his time and

services should be devoted exclusively to the Company”; this

requirement departed from the usual arrangement whereby a

Resident Engineer took charge of day-to-day operations, the Chief

Engineer providing consultancy and occasional oversight, and

charging his fee on a per diem basis. [6] Instead, Stephenson

was paid a salary, set initially at £1,500 p.a. plus £200 p.a. expenses, but later increased to £2,000 p.a. to keep abreast of that which

Brunel was to receive following his appointment as Chief

Engineer of the Great Western Railway.

Beneath the Chief Engineer, the management

arrangements were broadly those that John Smeaton had put in place during the construction of the Forth and Clyde canal over half a

century earlier. [7] The course of the Railway was divided into

a number of sections, each being placed under the direction of an

Assistant Engineer. Each section was then further divided into

shorter sections under the supervision of Sub-assistant

Engineers. (Appendix II.)

Some of those that Stephenson recommended

to the Board to fill these positions were men known to him, such

as his former pupil, John Birkinshaw (whose father appears in

Chapter 3); Thomas Gooch, who (together with Stephenson) had

done much of the early surveying, and George Bidder, who

Stephenson met while attending Edinburgh University. A

junior member of

the project team left his recollections of two of the professional

recruits who appeared at this time:

“Flying parties of surveyors were now succeeded by the

regular staff.

A tall, very tall young man,

upwards of six feet high, though losing somewhat from a slight

stoop and a low crowned hat, was found to have actually rented

one of the few available houses in the town. He was a man whom

no one set eyes on without wishing to see more of him. A grave

face, with a sweet and yet dignified expression, very dark eyes,

lineaments such as those to be found in the drawings of Westall,

a forehead not high, but broader than any often met with in

portraiture, in sculpture, or in life; the dress of a decent

mechanic, the air of an educated and well-bred man, and no

gloves: these were some of the outward marks of a man who has

since made his mark in the country. He was one of a family, in a

northern English county, distinguished for the talent of its

members. He was educated as a surgeon, but on coming of age

declined to follow his paternal profession, and, after an

engagement under Ericson, the inventor of the Monitors, during

which he had a share in conducting those experiments on the

Liverpool and Manchester Railway in which the speed attained by

the locomotives so much exceeded the expectations of their

constructors, became one of the earliest subalterns of Robert

Stephenson. The colleague and senior officer of this engineer

was a man considerably older, and rather of the stamp of the old

country surveyor, or the engineers of the school of Telford,

than of a mechanical turn. His shrewd grey eye, half

inquisitive, half defiant, twinkled with apparent love of fun. He soon devolved the out-door work on his assistant, although

the office-work at the station was light, the drawings being

prepared and the principal accounts kept at the

engineer-in-chief’s office in St John’s Wood.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

F. R. Conder (1868).

|

|

|

Sir Charles Fox

(1810-74).

Sub-Assistant,

later Assistant Engineer. |

The memories are of Francis Conder, whose

pupil-master was Charles Fox (1810-74), “the very tall young

man” referred to ― and less than six years older than Conder

[8] ― to whom Stephenson allocated work on the Watford Tunnel

and on the Camden Incline down to Euston Station, on which Fox constructed his fine

iron bowstring bridge over

the Regent’s Canal:

“My father became a

pupil of, and afterwards assistant to, Mr. Robert Stephenson,

who was then the engineer of the London and Birmingham Railway,

now the London and North-Western . . . .

In 1837, Herbert Spencer entered the office at Camden

Town as an assistant engineer to my father, and it was during

this time that my father designed the roof over Euston Station,

the first of the kind ever made. He afterwards designed or built

the large iron roofs of New Street Station in Birmingham, of the

Great Western Railway at Paddington, and others at Waterloo

Station, York, and elsewhere.”

River,

Road, and Rail ― some engineering reminiscences, Francis

Fox MInstCE (1904).

Fox might

already have been known to Stephenson through the connection

that Conder mentions with the Liverpool and Manchester Railway. He was later knighted for his contribution

to the construction of the Crystal Palace for the Great

Exhibition of 1851.

The “colleague and senior officer of

this engineer” to whom Conder refers, was G. W. Buck (1789–1854). It is possible that Stephenson first met Buck

during the latter’s visit to the Stockton and Darlington Railway

in 1828, or to the Rainhill locomotive trials in the following

year. Buck later described his duties as a member of the London

and Birmingham Railway project team:

“I have been engaged in the execution of various

Engineering Works for the last 20 years, but they were not of a

very extensive character; I had not superintended any Railway

until I was appointed one of the four Assistant Engineers, under

Mr. Stephenson, upon the London and Birmingham Railway; my

district is between London and Tring, and embraces a distance of

30 miles, and the work upon it is heavy compared with the rest

of the Line, i.e. there is more Tunnelling, and the Embankments

are higher and the Excavations deeper. My office is to see that

the Works are properly executed, and the amount of work done is

measured monthly by my Assistants, and tested by myself, as I am

responsible for its correctness.”

G.W.

Buck, from Railway Practice, S. C. Brees (1839).

Buck later worked on the Manchester and

Birmingham Railway, where among other work he designed the great

Stockport Railway Viaduct, which when completed in 1840 was the

largest in the world.

And so the professional ranks of the

project team were gradually filled:

“These gentlemen had arrived to superintend the works

of the great line of Railway, for which contracts had been

taken. Before long each of them had added a pupil to Mr

Stephenson’s staff. The younger of these gentlemen lived to

succeed that famous engineer as engineer-in-chief of the London

and North Western Railway . . . .”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

F. R. Conder (1868).

. . . . the

“younger of these gentlemen” was Buck’s pupil,

William Baker (1817-1878), who following Stephenson’s death in

1859 was appointed Chief Engineer of the London and North

Western Railway Company. One of the project’s sub-assistant

engineers, R. B. Dockray (1811-71), was also to achieve a

position of importance on the line, becoming its Resident

Engineer in 1840, then Resident Engineer for the Southern

Division of the London and North Western Railway upon its

formation in 1846. When Dockray retired through ill health in

1852, he was succeeded by William Baker.

|

|

|

Sir Robert

Rawlinson (1810-98).

(Assistant engineer and contractor). |

At the bottom of the management tree ― if

they could be considered a part of it ― were the ‘pupils’, in

effect civil engineering apprentices taken on by professional

engineers (in exchange for a ‘premium’) for a term under

articles of seven years. These young men . . . .

|

“. . . . unable to front a public meeting or a board

of directors, were in demand everywhere for field work.

Engineers who had pupils to spare, lent them to one another, or

let them out on terms of hire agreeable to all parties. Thus the

scene of personal recollection

[for the pupil, in this case Conder] may readily change from

the busy hive of workmen, that filled the great open ditch of

the Euston Extension, to the Derbyshire moors, the Essex corn

lands, or the Norfolk fens.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

F. R. Conder (1868). |

Stephenson’s biographer, John Cordy

Jeaffreson, leaves an interesting cameo of the Engineer’s regard

for his pupils:

“One of the pleasant features of Robert Stephenson’s

career was the strong personal attachment he formed for his

pupils when they were young men of capacity and character. He

never forgot or lost sight of them. A pupil of the ‘right sort’

was sure to win his approval and notice, and the pupil who had

so earned his good opinion was sure to reap advantage from it. On the other hand Robert Stephenson never considered himself

either bound, or at liberty, to recommend for advancement an old

apprentice, when he could not do so honestly. ‘I can do nothing

for you, unless you like to stop here as an ordinary workman,’

he said to more than one pupil when his time was out: but then

the young men to whom he so spoke merited no other treatment.”

The Life of Robert Stephenson, F. R. S.,

J. C. Jeaffreson (1864).

|

|

|

Herbert

Spencer

(1820-1903). |

The most illustrious member of this particular strata of

Stephenson’s

team ― indeed, with the exception of Stephenson himself, of

the entire project team

― was Herbert Spencer, later to become a notable philosopher,

biologist, anthropologist, sociologist and prominent classical

liberal political theorist.

The

17-year old Spencer joined Charles Fox’s team at Camden Town in

November 1837, and was assigned to the sorts of duties that

apprentices in most fields of endeavour might expect ― the lowly

and mundane:

“Many not unpleasant days were passed together

during the winter and early spring in surveying at various parts

of the line. It was, indeed, disagreeable in muddy weather to

make measurements of ‘spoil-banks,’ as are technically called

the vast heaps of earth which have, here and there, been in

excess of the needs for making embankments, and have been run

out into adjacent fields; and it was especially annoying when,

in pelting rain, the blackened water from one’s hat dripped on

to the note-book. The office-work, too, as may be inferred from

the tastes implied by the account of my education, came not

amiss. There was scope for accuracy and neatness, to which I was

naturally inclined; and there was opportunity for inventiveness. So fully, indeed, did the kind of work interest me, that I

shortly began to occupy the evenings in making a line-drawing of

a pumping engine for my own satisfaction, and as a sample of

skill as a draughtsman.”

“You will see by the date of this letter that I

am not at present staying in London. I have now been down in the

country rather more than three weeks, where I am staying as the

Company’s Agent to superintend the completion of the approach

roads to the Harrow Road bridge. My duties consist in seeing

that the contractor fulfils the terms of the contract, and also

to take care that when he draws money on account he does not get

more than an equivalent for the work done.”

An Autobiography,

Herbert Spencer (1904).

Spencer is generous in his praise of Charles Fox, assigning to him credit for work sometimes given to Stephenson ―

but such is generally the fate of any subordinate:

“. . . . in 1834, I had, in company with my father and

mother, paid a visit to him

[Fox]

at Watford, where he filled the post of sub-engineer. From this

post he had some time after been transferred by Mr. Robert

Stephenson, the engineer-in-chief, to superintend under him the

construction of what was in those days known as ‘The Extension.’ For the London and Birmingham Railway was originally intended to

stop at Chalk Farm [Camden Town];

and only in pursuance of an afterthought was it lengthened to

Euston Square. Mr. Charles Fox’s faculty had, probably, soon

made itself manifest to Mr. Stephenson. He had no special

discipline fitting him for engineering — very little

mathematical training or allied preparation; but in place of it

he had a mechanical genius. Much of the work on ‘The Extension’

for which Stephenson got credit, was originated by him: among

other things, the iron roof at Euston Station, which was the

first of the kind ever made. After the Extension was finished he

was appointed resident engineer of the London division of the

line: his limit being Wolverton.”

An Autobiography,

Herbert Spencer (1904).

Towards the end of the project, the number

employed in Stephenson’s team in various capacities had grown to

fifty-five. In looking into the backgrounds of those

for whom there is a record, it is surprising how many failed to

reach their sixtieth birthdays, perhaps a reflection on the

rigours of civil engineering in that age:

“.

. . . the havoc that death has made in the ranks of a

profession, which might expect to be distinguished by unusual

longevity has been most remarkable. Brunel, in the judgment of

those who remember the iron energy of his youth, should now be a

man in the prime of intellectual vigour. Robert Stephenson might

naturally have looked forward to many more years of quiet

authority. Locke, Rendel, Moorsom, ― how many are the names

which a greater reticence of labour and more attention to the

requirements of health, might have kept for many years from the

obituary!

In regarding such a mortality it is difficult not to search for

some cause peculiar to the profession. One sufficient cause may

perhaps be detected in the habitual loss of the usual repose of

the Sunday. For men to turn night into day is in itself a hard

strain. Twelve days’ work per week will try the strongest

constitution; but make the twelve into fourteen and the fatal

result arrives with startling rapidity. And working by day, and

travelling by night, make a constant and unrepaid demand on the

vital energy of the brain. The cost of the English railways

includes the lives of many eminent men.”

Personal Recollections of

English Engineers,

F. R. Conder (1868).

Although a number of

the team had successful civil

engineering careers, only Fox and Rawlinson achieved public recognition,

both being knighted. Bidder was also recognised, but within his

profession, being elected President of the Institution of Civil Engineers (1859-61), a position that was also held by Stephenson

(1855 & 56) and by Rawlinson (1894).

|

|

|

Brunel (right)

shortly before his death on 15th September 1859,

aged 53.

A barely recognisable Stephenson (left)

followed him on the 12th October,

aged 55. |

In concluding this section, I

feel it necessary to mention

a member of Stephenson’s

team whose name crops up repeatedly in these pages,

but of whom

very little is known. I refer to Lieutenant Peter Lecount RN,

FRAS.

Lecount wrote two books of particular interest to railway

historians and

collaborated with Thomas Roscoe on a third, a

travel guide to the

London to

Birmingham Railway. So far as I can establish, his

History of the Railway Connecting London and Birmingham

is the only reasonably comprehensive and contemporaneous record of the

Railway’s construction. [9] In it,

Lecount gives a chronological account (mainly from his

perspective) of how the project unfolded and

the main problems thrown up along the way, together with some

technical details of the first locomotives used on the line and

a brief geological description of the route.

At some point

towards the end of construction, Lecount was commissioned to write a section on

‘Railways’

for inclusion in the

Encyclopædia

Britannica,

but what emerged was far too detailed

for the Editor’s

purpose. Presumably Lecount then reached a publishing agreement with

his principal, for the entire piece appeared separately under

the title of

A Practical Treatise on Railways, Explaining

Their Construction and Management (1839). In it, Lecount joins Wishaw and Brees in examining the

civil and mechanical engineering aspects of the railways of the

time.

For more information on the life of Peter Lecount

see

Appendix III.

――――♦――――

PLANNING.

|

|

|

John Brunton

(1812-99) ― in 1880.

(Sub-Assistant

Engineer) |

Following his appointment as Engineer-in-Chief, Stephenson moved his home from Newcastle to the

Hampstead area of London, using the vacant Eyre Arms Hotel (which

stood opposite the location of the present-day St. John’s Wood tube station)

as the

headquarters for his project team. Its large

ballroom became the drawing office in which thousands of skilfully crafted drawings were prepared, each signed

off by Stephenson. The

draughtsmen worked in two shifts ― the day shift sleeping in

the rooms the night shift had vacated ― to produce the drawings quickly to meet the demands of the Company’s

directors, who had become impatient for work to commence

following the long delay in obtaining parliamentary approval for

their scheme. However, before plans could be produced, the exact

course of the line needed to be staked out and further detailed

surveying undertaken to establish exactly what land needed to be

bought, and from whom, and for conveyancing to take place:

“. . . . we got the survey and setting out of the line

done, from Kilsby Tunnel face, to Birmingham, and I was ordered

up to London to take charge of the designing of the necessary

Bridge Drawings and other contract plans for the letting of the

works to contractors. The Railway Company took the ‘Eyre Arms’

Tavern, at St John’s wood as an Engineers’ drawing office, the

Tavern at that time being unoccupied. The Ball room formed the

Drawing Office. Twenty draughtsmen by day & the same number at

night formed the corps I had to superintend, of course under the

occasional inspection of my chief District Engineer Mr T. Longridge Gooch.

All the contract drawings had to be ready by a certain

day — about a fortnight after the day we commenced the work upon

them. It was a tight pinch, for my draughtsmen then were not

much used to this class of work. But we struggled on — I, very

anxious that this, my first important charge should not be

behind time, kept at my post night and day with one night only

in bed for the fortnight. This was foolish, as I found out

afterwards, but I was full of energy and determination.

One by one my staff dropped off quite overcome with

the incessant work I called for, but at last work was

accomplished on the evening before the Contract Plans &

Specifications were due in Birmingham. I had looked them all

over — put them all into their special portfolios — and was

waiting for the arrival of Gooch with some one, who was to take

them in charge and convey them to Birmingham by the night Mail

Coach. (Recollect there were only 2 Railways in existence then,

The Liverpool & Manchester and the Stockton and Darlington.) Every thing being ready I went down to the Entrance and sent for

a cab to take me to Edmonton, where my dear Father and Mother

were then living.

Each completed plan was endorsed

by

Stephenson.

At that moment I met Mr. George Stephenson and Mr.

Gooch. The latter hailed me: “Halloo Brunton, I can find nobody

to take these plans down to Birmm tonight, so you must take

them.” I made some slight remonstrance on the head of the work I

had gone thro’ for a fortnight. But no one else could be found,

so the cab which I had hired, with anticipation that it would

convey me to a good bed & sleep that night, was loaded with the

packages of plans and directed to take me to the ‘Swan with Two

Necks’, Lad Lane, whence the Mail Coach for Birmingham started

at half-past eight. I found all full inside and only one of the

four outside places left for poor me. I booked for Birmm, saw my

packages safe in the boot of the coach, and got the middle seat

of the three behind the coach man. I drew my plaid round my head

leaned back against the luggage on the roof and was fast asleep

before the coach left the yard. Nor did I awake until, 11½ hours

afterwards, I was roughly shaken and told I was at the ‘Hen &

Chickens’ Hotel Birmingham! Very stupid I felt, but I deposited

the plans . . . .”

From

The Dairy of John Brunton, Sub-Assistant Engineer.

Following land purchase, detailed plans,

specifications and schedules of quantities could be drawn up,

which together with samples of the strata, could be made

available to prospective contractors to assist them is preparing

tenders for the work. Thus, the first twelve months of the

London and Birmingham Railway project were absorbed with this

essential preliminary work, of which there was very little

evidence on the ground.

London & Birmingham Railway

‘Notice to Enter’.

Following their appointment, the engineers

set about staking out the exact course of the line, of which

Conder leaves an account:

“The next step in the invasion

[the first being surveying] proved a yet further aggravation

to the farmers, although it was one which, for the first time in

the course of the contest, afforded them the pleasure of

retaliation. Loads of oak pegs, accurately squared, planed, and

pointed, were driven to the fields, and the course of the

intended railway was marked out by driving two of these pegs,

one left standing about four inches above the surface to

indicate position, and a smaller one driven lower to the ground

a few inches off on which to take the level, at every interval

of twenty-two yards. It is obvious that the operations of

farming afforded many an opportunity for an unfriendly blow at

these pegs. Ploughs and harrows had a remarkable tendency to

become entangled in them; cart wheels ran foul of them;

sometimes they disappeared altogether. A mute and irregular

warfare on the subject of the pegs was generally protracted

until the last outrage was perpetrated by the agents of the

company; the land was purchased for the railway.”

Personal Recollections of English Engineers,

F. R. Conder (1868).

By the end of November, 1833, the

newspapers were beginning to report progress:

“We understand that about thirty miles of the line of

London and Birmingham Railway in parts where the greater

quantity of labour will be required, have been staked out. About

£96,000 (out of £125,000) of the second call have been already

paid up; and it is not expected that any material deviation from

the line for which the Act was obtained will be necessary. The

important undertaking is now proceeding with great spirit.”

The Northampton Mercury,

30th November 1833.

Following completion of land purchase,

plans and drawings could be prepared:

“It

[the London and Birmingham Railway] was the first of our

great metropolitan railroads, and its works are memorable

examples of engineering capacity. They became a guide to

succeeding engineers; as also did the plans and drawings with

which the details of the undertaking were ‘plotted’ in the Eyre

Arms Hotel. When Brunel entered upon the construction of the

Great Western line he borrowed Robert Stephenson’s plans, and

used them as the best possible system of draughting. From that

time they became recognised models for railway practice. To have

originated such plans and forms, thereby settling an important

division of engineering literature, would have made a position

for an ordinary man. In the list of Robert Stephenson’s

achievements such a service appears so insignificant as scarcely

to be worthy of note.”

The Life of Robert Stephenson, F.R.S.,

J. C. Jeaffreson (1864).

Specifications and contract documents were

also drawn up, and the work then advertised for tender. Some

difficult work was let by single tender ― the Tring Cutting,

for example ― but most was let through competitive

tendering, Robert

Stephenson being present at the opening of the sealed bids . . .

.

“The works are let by Public Contract, and the

Directors usually accept the lowest Tender, if the parties are

respectable and are able to give security; I am present at the

opening of the Tenders, but I have no opportunity of knowing

their several amounts until then: in allotting the several

Contracts, I have subdivided them pretty equally, and arranged

them so that one Contract shall not interfere with another; the

Work is measured at the time the Contractor delivers his Tender,

which is accompanied by a ‘Schedule of Prices’, upon which his

Estimate is founded, and at the expiration of every month the

work is measured and priced according to such List, and the

amount is paid him, with the exception of 20 per cent, which is

withheld until half the contract is finished, the amount

retained is then 10 per cent only, and the Contractor afterwards

receives the full amount of his work.”

Railway Practice, S. C. Brees

(1839).

――――♦――――

CONTRACTORS.

At the commencement of the project, the

Board had directed that:

|

•

those parts of the line which require

the longest time for execution, shall be

commenced first, and the rest in succession; so

that the whole may be completed at the same

time;

•

the purchase of land shall be made with

reference to this arrangement;

•

the payment of the calls

[on

part-paid shares in the Company] shall be

regulated, so that no part of the capital shall

be demanded before it is actually required;

•

the works shall be executed by contract,

by open competition, upon plans and

specifications previously prepared; security

being taken for the due performance of the

engagements. The only deviation from this plan

which the Directors propose, is in reference to

the portion of the line at the London end. This

portion they would recommend to be executed with

all the expedition which may be found consistent

with the stability of the work, and other

considerations, from a conviction that the

novelty and convenience of a railway contiguous

to the Metropolis cannot fail to excite a

general interest, and consequently to prove an

early and productive source of revenue to the

Company.

Chairman’s Report, London, 19th September, 1833.

|

Using contractors to build the Railway offered the Company three potential

advantages. By advertising their requirements in the

marketplace, the Company could more readily acquire the

appropriate manpower and equipment ― both being supplied by the

contractor ― than to assemble and manage it for themselves. [10] The

Company was also relived of the task of disposing of surplus equipment (mainly wagons, barrows, planks; also

ropes, chains, horses, possibly steam engines of various types,

etc.) on completion of the work, the contractor removing

it for his use elsewhere, or selling it by auction. Finally, the acquisition of services

through a process of competitive tendering offered the

promise that the work would be carried out in the most

economical manner.

However, even at this early stage in the

development of large-scale civil engineering, competitive

tendering was not considered to be a practice always to

be adhered to. The principle followed by the great civil

engineer Thomas Telford, was better the devil you know than

the one you don’t, advice that was reflected in early books

on civil engineering:

“As there is no difficulty in making an accurate

estimate of the sum which a new road ought to cost, if a

contractor of established reputation for skill and integrity,

and possessing sufficient capital, is willing to undertake the

work for the estimated sum, it will always be decidedly better

to make an agreement with him than to advertise for tenders.

If a contractor cannot be got, possessing the

qualifications which he ought to have to justify a private

arrangement, then an advertisement must be had recourse to. But

when tenders are delivered in, it is very important to take care

to act upon right principles in making a selection from them.

The preference should invariably be decided on by taking into

consideration the skill, integrity, and capital of the persons

who make the tenders, as well as the prices which they offer:

for if a contractor be selected without skill, or integrity, or

capital, merely because his tender is for the smallest sum, the

consequence will inevitably be imperfect work, every kind of

trouble and disappointment, and frequently expensive

litigation.”

A Treatise on Roads, Sir Henry Parnell (1833).

“We strongly advise every company not to look at the

lowest tender, but at the respectability, competency, and

character of the parties who come forward to offer for the work. There are well-known persons who go about to offer for works of

this kind, without the slightest intention of ever finishing

them, who are in effect mere men of straw, borrowing perhaps a

hundred pounds to make a beginning, and trusting to the chance

of doing all the light and easy work, which will pay them well,

and then standing stock-still till the company are glad to buy

them out, after which they have to do all the heavy work

themselves, at a proportionate cost, which is still farther

increased by having to press the work in all directions, in

order to make up as much as possible the time wasted by the

contractor.

There is no way of preventing this but awarding the

work to persons of established character, who will give in a

fair estimate, and be content with a reasonable profit, and

finish their work in such a way that they can look for future

employment from the same parties; whereas there are many who in

fact never make an estimate at all, but put in a round sum,

taking no care but to be low enough so that they may get the

job. Many tenders of this kind have been put in at prices by

which it was absolutely certain the parties must have lost

several thousand pounds if they had completed their contracts.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Peter LeCount (1839).

That was the theory, but Stephenson was to

have first-hand experience of the legal maxim caveat emptor,

‘let the buyer beware’. Had everything gone according to plan,

the London and Birmingham Railway would have been built by

contractors to plans and specifications drawn up by the Company’s engineers, under whose general direction the work

took place and who measured up and certified for

payment each month the quantity of work completed on each contract. But as

events turned out, the contractors for eight of the thirty

contracts (Appendix IV.) failed to fulfil their

obligations, leaving the Company’s engineers to procure the

necessary plant and manpower, and undertake the work themselves. These failures included the most difficult sections of the line, the Tring and Blisworth cuttings and the Primrose Hill and Kilsby tunnels.

The first railway Act having being passed,

at the following half-yearly shareholder’s

meeting the Chairman was able to report significant progress

in much of the preliminary work. This involved setting up the project and

the preparation that was necessary before tenders could be

advertised to

undertake the work:

“Since the General Meeting of the Proprietors in

September last, the attention of the Directors has been

principally occupied by preparatory measures for the

construction of the Railway, and the arrangements for obtaining

possession of the Land.

In their former report, the Directors announced the

appointment of Mr. Robert Stephenson, as Engineer in chief. They

have since succeeded, to their complete satisfaction, in

obtaining the services of a sufficient number of skilful and

scientific persons as Assistant Engineers, for conducting the

Works on every part of the Line, which has been arranged in

sub-divisions for this purpose.

Notwithstanding the obstacles which an unfavourable

season has presented to the field operations of the Engineers,

the whole of the line from London to Birmingham has been staked

out and levelled, with the exception of a few points, to which

Mr. Stephenson is desirous of devoting his particular attention. He has reported that the Plans and Specifications of the Works

for the first twenty miles from London will be completed by the

1st of March.

The directors will then immediately advertise for

Tenders for the execution of the Work on that portion of the

Railway, and the Plans and Specifications for other parts of the

Line will follow in such succession as shall bring the remainder

into completion, in conformity with the intention announced in

the former Report.”

Chairman’s Report, Birmingham, 21st February 1834.

James Copeland, who obtained the contract

for building the Watford to Kings Langley section, including the

long Watford Tunnel, left a record of the financial aspects of

contracting for civil engineering work:

“I am now executing a Contract upon the London and

Birmingham Railway, which I obtained by open tender; my Contract

amounts to £117,000, and extends from Watford to Kings Langley,

and is about 5¼ miles in length . . . . I found two Sureties . . . . to the amount £11,700 (or

10 percent upon the amount), each in half that amount . . . . There is about 700,000 cubic yards of Cutting and 600,000 cubic

yards of Embankment, also a Tunnel of 1,716 yards in length (the

Cuttings and Embankments are nearly equal). Ten or twelve Tenders were submitted for the Contract,

and I believe my Tender was about the lowest; it consisted of a

gross sum, and a ‘Schedule of Prices’ attached, in which the

prices for open Cutting was 1s 2d per cubic yard (the price for

the Cutting also includes the Embankment), the average Lead of

which is about a mile, the Tunnelling was £28 per lineal yard,

and the Fencing about 2s 6d or 2s 9d per yard for each side of

the railway . . . . I find Waggons, Barrows, Planks, Sleepers, Chains, Keys

and Pins, which amounts to about 2d per yard more; i.e. for

the actual cost of Materials, exclusive of the Wear and Tear; as

I have expended £15,000 for materials, there is the interest of

that sum, and the Wear and Tear to be allowed for extra, there

is a continual expense in the repairing of Waggons, &c. The expence value of the materials, after the conclusion of the

Contract, may be about ¼d per yard, which deducted from the

original outlay, would make the price of the materials 1½d per

cubic yard, the cutting therefore costs 10½d per cubic yard; and

we take the risk of Slips and Contingencies; and prepare proper

Drains; which in Clay cuttings are very considerable; also the Sodding of the Banks, as some of the soil is removed twice,

which I have allowed for in the average of 2d per yard. I

therefore consider that a Contractor must pay great attention,

to his business, and practice considerable economy, to make a

profit out of the 1s 2d, as it is barely sufficient.”

James

Copeland, from Railway Practice, S. C. Brees (1839).

――――♦――――

WORK COMMENCES.

It seems evident from the tone of the

Chairman’s reports that the Board intended to exercise control

over the project rather than leave everything to Stephenson. They had good reason,

for there were business risks to manage over and above than the

line’s engineering. Investor confidence needed to be maintained in what for the time was large-scale innovation, for even at an early stage of

the work the Board probably realised that they would need to

raise significantly more capital than first estimated to complete the line. [11]

Thus, a quick win was needed, which was best

achieved by bringing the southernmost section of the line ― its

biggest revenue-earner ― into operation soonest. Achieving this would also help raise the project’s profile in

the eye of its investors and of the general public, hence the

Board’s

directive that:

“The only deviation from this plan

[the sequence for

undertaking other stages of the project] which the Directors

propose, is in reference to the portion of the line at the

London end. This portion they would recommend to be executed

with all the expedition which may be found consistent with the

stability of the work, and other considerations, from a

conviction that the novelty and convenience of a railway

contiguous to the Metropolis cannot fail to excite a general

interest, and consequently to prove an early and productive

source of revenue to the Company.”

Chairman’s Report, London, 19th September, 1833.

It was also recognised that the long Tring

Cutting represented significantly more work that elsewhere, and

here excavations commenced early on to ensure that its

completion did not delay the eventual opening of the line. [12]

At the half-yearly shareholders’ meeting

held in February 1834, the Company Secretary [13] informed the

meeting that, with a few exceptions, the entire

length of the line had been staked out, that plans and

specifications for the first 70 miles were nearing completion,

and that the first construction contracts were let:

“The London and Birmingham Railway, which attracted so

much of the public attention in the progress of the bill through

parliament, may now be said to be fairly launched. Tenders have

been accepted for executing the first twenty-one miles from

London in the period of two years, on terms which are considered

very favourable, this being in many respects the most expensive

part of the line. The specifications and plans of the works are

spoken of as being full, clear, and precise, shewing that the

time elapsed since the passing of the act has been profitably

employed. The next contracts, which will be advertised in a

short time, will comprise the district between Coventry and

Birmingham.”

Birmingham Gazette, 5th May 1834.

By June, 1834, work had commenced on the

Watford Viaduct and the section southwards to Willesden .

. . .

“The London and Birmingham railway has been commenced

by Messrs. Nowell and Son, the contractors for that part of the

line commencing from the River Brent to the Colne. They have a

number of excavators

[navvies] digging the foundations for the bridge over the

turnpike road at the lower end of Watford. It will be about

forty feet above the road, and there will be five arches, which,

with the abutments, &c. will be near four hundred feet in

length. Messrs. Copeland and Harding, the contractors for the

third part ― viz. from the Colne to King’s Langley, are likewise

at Watford, with several other gentlemen connected with this

work.”

The Northampton Mercury,

21st June 1834.

The Birmingham to Coventry

contracts were let in August:

“The directors, in conformity with the intentions

announced in their last report, contracted on the 21st April for

the first 21 miles of the railway from London, by three separate

contracts, binding the contractors, under a penalty, to complete

their respective portions in two years from 1st June last. They

further contracted, on 12th August for the first 21 miles of the

railway from Birmingham, by five separate contracts, to be

completed, under similar penalties, in 2½ years.”

Chairman’s Report, London, 21st August, 1834.

And so work on the Railway commenced:

“During the years 1834, 5, 6, and 7, the most

strenuous exertions were made in prosecuting the works: and

although many harassing and unforeseen difficulties were

encountered on some parts of the line, the continued energies

and acknowledged skill of the engineer-in-chief and his able

assistants were successfully employed to surmount them.”

Introduction to Drawings of the London & Birmingham Railway,

John Britton (1839).

――――♦――――

ESCALATING

COSTS.

Several factors conspired to drive up the

Railway’s cost and introduce delay. Other railway projects that

commenced during the 1830s added to the competition for

increasingly scarce resources, the effect being to increase wage and material costs

well beyond estimates: [14]

“Retardation of Railways by the High Price of

Labour. ― Owing to the great demand for labour the wages

have risen considerably, and increased obstacles are thrown in

the way of completing the lines which are in progress. The

Birmingham, Southampton, and other lines, we are informed, are

not proceeding with little more than half the rapidity they

were. Of course this, with the great rise in iron and other

things, must tell materially in the estimates, and tend much to

retard that early benefit the country would otherwise derive

from these undertakings. Common labourers are offered on the

London and Birmingham Railway, from fifteen to eighteen

shillings per week, and masons four shillings and sixpence per

day, but even at these wages the application for hands in many

places has been unsuccessful.”

The Railway Magazine

, Vol. 1, 1836

“Iron, one of the principal sources of expense, one of

its indispensable requisites, rose from nine to fourteen pounds

per ton, entailing an expense of about £300,000 above the

parliamentary estimate, although a rise of two pounds per ton

had been allowed for therein.”

The Railway Companion, from London to Birmingham,

Arthur Freeling (1838)

“From the great increase in prices, which took place

almost immediately after the letting of the works, no less than

seven contracts were thrown on the Company’s hands, and of

course these were the most difficult and expensive parts of the

works, and in each case, the directors had to purchase all kinds

of implements and materials at a vast expense, including five

locomotive engines, while, from the times at which these seven

contracts took to complete them, there was very little

possibility of transferring these implements (technically called

the Plant) from one contract to another. This, although a very

expensive process, was the only one to be followed, or the line

could not be opened under at least a year beyond the time

contemplated.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe and Peter Lecount (1839).

The purchase of land also proved far more

expensive than anticipated, for landowners soon developed

tactics to inflate its value. Lecount described one manoeuvre that landowners

adopted to place more cash in their pockets:

“In one portion of the line, on the Birmingham

division, some land was passed through in such a way that it was

evident the proprietor required, in reality, no accommodation in

the way of bridges at all. At the first outset, however, he

demanded five bridges; but, in the course of the discussion,

came down to four, with an equivalent in the price of the land.

It was absolutely necessary to obtain the land, or the

contractors would have been stopped in their operations, so

that, after a great deal of argument, the Company was forced to

submit to this enormity, and the agreement was signed, sealed,

and delivered, guaranteeing to the proprietor a bridge at A,

another at B, another at C, and another at D.

Soon after the money had been received the proprietor wrote to

say, he thought he could dispense with a bridge at A, and

if the company would give him about half its value he would do

without it; of course as this would save expense it was agreed

to, and bridge A done away with, the proprietor receiving

about half what it would have cost in building.”

The London and Birmingham Railway,

Thomas Roscoe and Peter Lecount (1839).

The reader might guess what happened next;

bridges B, C and D were, in sequence, declared unnecessary by

the landowner, in each case leaving him to pocket half the

bridge’s construction cost as compensation for relinquishing it. Sometimes the price demanded by a landowner was so

exorbitant that the Company declined to buy. An example was the

high price asked for the land on which to build Tring

Station, which caused the Company to consider relocating the station

on cheaper land further down the

line at Ivinghoe. But in this case the townsfolk raised a collection

to make good the difference between the asking price and what

the Company was prepared to pay, and Tring got its

station, albeit almost 2 miles from the town.

The Company was also under pressure over

land purchase from another direction, their contractors:

“It will be much better if no contract is let till the

company are in possession of all the land belonging to

that part of the line. Attention to this will most probably save

the company many thousands; and if it be not done, exorbitant

claims, which are sure to be advanced, will often have to be

complied with, because the contractor is demanding the land, and

very properly saying, that he cannot be bound to time, unless he

be put in possession of his ground.”

A Practical Treatise on Railways,

Peter Lecount (1839).

There were also engineering difficulties. Although the canal builders had shown the way,

the more direct route taken by a railway generally

needed more substantial earthworks than a contour-following

canal in order to create an acceptable

gradient, [15] a need that could prove expensive to satisfy. For

instance, on closer investigation it was found prudent to build

some of the

London and Birmingham Railway’s cuttings and embankments with shallower slopes than had

been intended in order to reduce the risk of slip. This meant

that more land had to be purchased, while the increased volume of

earthworks that resulted required more man-hours of labour to construct. Both factors acted to

increase cost over estimate. Engineering problems such as these [16] stemmed from a lack of

experience, and of the equipment and data that today permit civil engineers to explore the strata and model the

land more readily.

Adverse weather conditions also slowed or

halted work on cuttings and embankments, for when ground is wet

or sodden ― particularly if it has a high clay content ― it

becomes difficult or impossible to work. The same applies to the

effects of frost and snow. On average, over a year, the weather

permitted contractors to work on five days out of

seven.

Time lost to problems can be estimated for on

the basis of past experience ― where it exists ― and contingencies included in the

projected cost. But the question the designers need to address is how

much contingency to build in without making the project appear

financially unattractive to potential investors:

“Mr. Moss, chairman of the Grand Junction Railway

Company, on his recent examination before a committee of the

House of Commons, made some strong remarks on the

misrepresentations of engineers, in omitting important items of

expense from the parliamentary estimates. He stated, that the

whole case of a railway is never fairly brought before

Parliament on application for a bill; and added that engineers

were aware, if they apprised the shareholders of the whole cost

attending such undertakings, the latter would never embark on

any of them.”

Introduction to Drawings of the London & Birmingham Railway,

John Britton (1839).

CHAPTER

7

――――♦――――

APPENDIX I.

THE ESTIMATED COST OF THE LINE

Cap. xxxvi. An Act for making a Railway from London to

Birmingham.

6th May 1833.

. . . . III. And be it further enacted,

That it shall be lawful for the said Company to raise amongst

themselves any Sum of Money for making and maintaining the said

Railway and other Works by this Act authorized, not exceeding in

the whole the Sum of Two million five hundred thousand Pounds,

the whole to be divided into Twenty five thousand Shares of One

hundred Pounds each, and such Twenty five thousand Shares shall

be numbered, beginning with Number One, in arithmetical

Progression . . . .

|

|

Estimates proved in the House of Commons

£ |

£ |

|

Excavations and Embankments |

170,000 |

|

|

Tunnelling |

250,286 |

|

|

Masonry ― This Item is increased in

consequence of an Agreement with the Commissioners of

the Metropolitan Roads to add to some of our Bridges in

Width and Height, and also an Agreement with the

Trustees of the Radcliffe Library Estates to increase

the Number of Arches in the Wolverton Viaduct, and also

an Addition of Two Bridges over the Avon near Brandon,

to avoid the Diversion of the River. |

350,574 |

|

|

Rails Chairs Keys and Pins |

212,940 |

|

|

Blocks and Sleepers |

102,960 |

|

|

Ballasting and laying Rails |

102,960 |

|

|

Fencing at £740 per Mile |

76,032 |

|

|

Sub-total |

|

1,874,752 |

|

|

|

|

|

Land |

250,000 |

|

|

Six Water Stations at £500 |

3,000 |

|

|

Six intermediate Pumps |

600 |

|

|

Offices, &c. requisite at each End of

the Line, for Convenience of Passengers, &c. and Walling

for enclosing the Space for Depot |

16,000 |

|

|

Forty Locomotive Engines £1,000 |

40,000 |

|

|

300 Waggons at £30 |

9,000 |

|

|

Sixty Coaches at £200 |

12,000 |

|

|

Sub-total |

|

2,205,352 |

|

Contingencies |

|

294,698 |

|

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

2,500,000 |