Road coaches.

|

|

|

|

A coach of the Elizabethan

era. Note the absence of brakes and suspension on the

chassis. |

The Tudor period saw the development of the road coach, the wheels of which

imposed far greater wear on the unmade road surfaces of the time. These

coaches had solid wheel rims and primitive leather strap suspension,

which, in conjunction with the deep ruts and potholes of the road

surfaces over which they travelled, must have made any journey for their

occupants uncomfortable.

Although they first appeared during the 16th century, it was not

until the 18th century that coaches came into more common use, the main

drawback to coach travel being the poor condition of the roads. Following the General Highway Act of 1555, road surfaces improved, but

to a very limited extent. Parish surveyors were pressed men, often

illiterate and with no training in road engineering, while those

performing their six days unpaid statute labour were hardly likely to be

enthusiastic about the task. Stories abound of roads being

impassable in wet weather, thus journeys were best made during the summer

months.

By the late 18th century, many main roads had come under the control of

turnpike trusts and road conditions had begun to improve. This

period of road transport history ― from the first royal mail coaches in the

1780s to the 1840s and the coming of the railways ― is now known as

the ‘Golden Age of Coaching’, familiar to us today through sentimental

Christmas card scenes of snow-covered stagecoaches arriving to a hearty

welcome at a coaching inn.

Stagecoaches

The stagecoach developed to convey fare-paying passengers, rather

than act as the personal conveyance of the gentry and nobility.

The first stagecoach route, from Edinburgh to Leith, commenced in 1610.

An early stagecoach advertisement, from the Birmingham Mail

The name ‘stagecoach’ is derived from the term ‘stage’, which referred

to the distance between stops along a stagecoach route. During the

first decades of the 19th century, when more emphasis was placed on speed, stages were usually

between 8 and 10 miles apart and the coach travelled the entire route in

stages, changing horses (which took a few minutes) at each.

Coaching inns sprang up along the coaching routes to provide teams of

fresh horses and sustenance for coach passengers, including overnight

stops on long journeys.

During this period significant

developments

in road construction were made by Thomas Telford and, to a

more widespread

extent, by the Scottish road engineer John Loudon McAdam. Road surfaces

improved, and turnpike roads were often straightened, widened, and

given gentler curves and gradients. Stagecoach construction also

evolved with the fitting of better brakes and the introduction of steel leaf

spring suspension. These improvements resulted in coach speeds increasing from around 6 to 8

miles per hour, inclusive of stops, which greatly increased the level of

mobility of travellers and the speed of mail delivery. The

number of passengers increased, as did the volume of wheeled road

traffic.

Stagecoaches were not the only wheeled transport to make good use of the

turnpike road through Tring. By the time of the Sparrows Herne Turnpike

Act 1823, which extended the trustees’ powers for a further 21 years and

authorised repairs and improvements to the road, it was noted in the

press that “a

great variety of vehicles now use the road – coach, berlin, landau,

chariot, calosh, chaise, hearse, wagon, cart, wain or other carriage”.

“This was the hottest

day of the Summer. Several coach horses dropped dead on the roads from

the excessive heat.”

Tring Vestry Minutes, 1st September 1824

Coach travel was by no means straightforward and various hazards had to

be contended with. The earliest coaches had no brakes, careful handling

of the horses being the only way to keep the coach at a steady pace and

control progress over inclines. On very steep hills passengers were

required to step down and walk. Other obstacles such as deep ruts,

potholes and flooding of the road, together with loose animals, could

also cause accidents. Overall, early coach travel was a most

uncomfortable experience and one that did not improve greatly over the

years:

“What advantage is it to

men’s health to be called out of their beds into these coaches an hour

before day in the morning, to be hurried in them from place to place

till one hour, two, or three within night, in so much that, after

sitting all day in the summertime stifled with heat and choked with the

dust, or the wintertime starving and freezing with cold or choked with

filthy fogs, they are often brought into their inns by torchlight, when

it is too late to sit up to get a supper; and next morning they are

forced into the coach so early that they can get no breakfast?

What addition is this to men’s health or business, to ride all day with

strangers, oftentimes sick, ancient, diseased persons, or young children

crying . . . . and many times . . . . crippled by the crowd of the boxes

and bundles? Is it for a man’s health to travel with tired jades,

to be laid fast in the foul ways and forced to wade up to the knees in

mire; afterwards sit in the cold till teams of horses can be sent to

pull the coach out? Is it for their health to travel in rotten

coaches and to have their tackle or perch or axletree broken, and then

to wait three or four hours, (sometimes half a day) to have them mended

again, and then to travel all night to make good their stage? Is

it for a man’s pleasure . . . . to be affronted by the rudeness of a

surly, doggčd, cursing, ill-natured coachman; necessitated to lodge or

bait at the worst inns on the road, where there is no accommodation fit

for gentlemen, and this merely because the owners of the inns and the

coachmen are agreed together to cheat the guests?”

From a contemporary letter quoted in Travel in England in the Seventeenth Century, Joan Parkes (London, 1925)

In the earliest days of coach travel, it was too precarious for

passengers to sit on top, but later designs included two seats behind

the driver and two over the luggage box at the rear; outside travellers

needed to be aware that it was prudent to stay awake to prevent toppling

over the side. Inside, and at double the cost of outside seating,

were two seats facing each other, taking from four to six passengers at

a squeeze, with knees touching. Neither was coach travel

comfortable; straw was laid on the floor to absorb the wet and mud;

windows had no glass, and in bad weather a leather curtain was rolled

down. Early suspension was by leather straps, which caused an unpleasant

swaying motion, but straps were later superseded by steel

springs, which enabled the coach body to be lowered; a lower centre of

gravity meant the coach was less likely to overturn.

|

Strap suspension. Suspension of the state coach built for the Duke of Cleveland by Rigby & Robinson of Park Lane, London. Dating to around 1810-1820, the thick leather straps shown were employed to support the coach body and serve as shock absorbing springs. |

Coach driving was recognised as a skilled profession, with drivers

earning the respect of both colleagues and passengers alike. Coachmen

drove on average some 50 miles a day for a weekly wage of approximately

a guinea, but the driver also expected a

generous tip from each passenger and harassed those who did not pay the

expected amount ― some coaching advertisements listed the number of drivers for

a given journey, which gave passengers some idea of the tips they would

have to pay in addition to the fare. Other perks for the driver were

the delivery of parcels and pocketing the fares collected from

passengers picked up between stages. Most

coaches carried a guard, and he too expected a tip. The guard usually

stayed with the coach for the entire distance, thus, on long routes, he may

not have been that alert at journey’s end.

The working life of a coach horse was some three to four years. They

needed to be fit and strong to haul a coach at around 10 miles an hour between stages. Horses for coaching use were generally supplied by local

land-owners and farmers, quite often sold due to unsuitability for any

other sort of work, but they usually settled down in harness. Some were

bred specially for coaching [1] and were used for the fast mail

services; these animals fetched a very high price, as much as Ł25 each

in 1834.

The Royal Mail service was first made available to the public in the

reign of Charles II at a time when most of the country’s mail was

carried by mounted post boys, whose solitary progress left them

a vulnerable prey to highway robbers. In 1784 when the Post Office

adopted the use of Stage Coaches, which became the most important

vehicles on the road. By the 1830s and 1840s, the nightly departure of

the mail coaches from the General Post Office in St Martins-le-Grand was

one of the sights of London, but by 1846 it was over, replaced by the

new, faster railway services.

Royal Mail coach ― Science Museum, London.

This vehicle employs steel leaf spring

suspension.

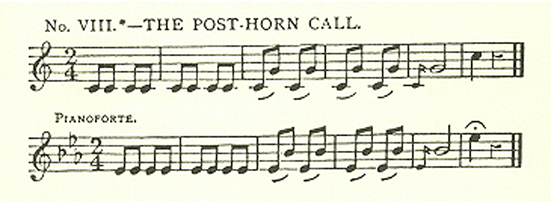

Mail coaches were not owned by the Post Office but by contractors, the

only Post Office employee being the Guard, who was armed with a horse

pistol and a blunderbuss; he also carried a clock, kept in a leather

pouch, and was equipped with a post horn to give advance warning of the

coach’s arrival. Many guards prided themselves on their post-horn

blowing skills. The three-foot long instrument, made of tin, produced

four deep and bell-like notes to sound the instantly recognisable

message of ‘Clear the Road’. This was a warning to inn landlords of the

imminent arrival of the coach in order that ostlers could have ready

the change of horses. It also alerted toll-gate keepers to open their

gates, for the law demanded that vehicles carrying the Royal Mail should

encounter no obstructions to impede their

progress.

This from the Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire & Hertfordshire Chronicle,

9th June 1821:

|

NEW ROYAL MAIL COACH to Birmingham, Warwick and Leamington Spa. The Nobility, Gentry and the Public are most respectfully informed the above Royal Mail coach leaves the Kings Arms Inn, Snow-Hill, London, every evening through Watford, Berkhamsted, Tring, Aylesbury, Winslow, Brackley, Banbury, Southam, Leamington and Warwick to Birmingham. Messrs. Hearn, Griffin, Mash, Vyse & Co.

Performed by T. Dale, T Landon, C Wyatt, Abraham Godfrey & Co. |

|

|

|

A letter sent before the advent of the penny post |

Writing in the 1890s, Tring historian Arthur MacDonald had this to say about the local mail coaches:

“There were two Royal Mail coaches passing through Tring, the

down mail about midnight, and the up coach about three in the

morning, rousing the town by a lively tootling from Parsonage

Bottom [3] to the corner of Frogmore

Street, where the little Post Office stood [4]

apprising the indefatigable Post Mistress, Miss Betsy Montague,

of its approach. . . . . these coaches changed horses at the Cow

Roast, halfway between Tring and Berkhamsted, then a wayside inn

of importance, its stables being filled with the numerous horses

then used on the canal, as well as the changing teams for

coaches.”

An intricate postal charging scale was based on distances from London, the

distances shown being the same as those on milestones by the side of the

road. When a letter was despatched on a cross country route, it was

usually carried by a Post Boy on horseback to a Post Office at a mid

point, where it was franked with a Mileage Mark showing its distance from

London, there to be collected by the mail coach if necessary. The example

shown is a letter sent in 1807 from Bledlow to

Buckingham (the addressee of the missive, Thomas Stanhope Badcock, was

the father of Vice-Admiral Stanhope who lived for a while at Drayton

Manor, south-west of Tring). The postal charge on this letter, 1s. 2d., is written on

the front and is payable at the receiving end. The mileage mark, ‘41’,

is Tring’s distance from London. [5]

|

“Stamps have been invented for sticking on letters. This will save going into the Post Office and paying the fee for a letter.” Tring Vestry Minutes, 25th April 1840 |

Tring’s Post Office once stood on the corner of the High Street and

Frogmore Street. Following the introduction of the Uniform Penny Post in

1840, letters could be sent throughout the U.K. for a penny, payment being made with

the first prepaid postage stamp, the ‘Penny Black’. The volume of mail

increased and it became apparent that the small cramped office with its

inconvenient street corner position was unsuitable. Tring needed

something better-suited to the modern age; the poem in the

Appendix explains what happened then, and since.

Some looked forward to travel on the new public railways with fear and

apprehension, but these feelings were quickly dispelled when its

comparative speed, safety and comfort became apparent:

|

I left the realm of silence by the

Rail. THOMAS COOPER |

Mail was first carried by train on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway

in 1830, and in 1838 (the year in which the London & Birmingham Railway opened

throughout) legislation was introduced to regulate the conveyance of the mail by

railways. As the railway system spread, the horse-drawn mail coaches

disappeared from our roads. But despite the speed of mail in

transit increasing dramatically, this was not reflected in the time it

took to distribute it to its recipients. Mail bags still had to be conveyed between railway

stations and sorting offices by conventional means, not always a smooth operation

as one disgruntled commentator pointed out:

|

“THE RAILWAYS, THE PUBLIC, AND OURSELVES. The following time-table of the ‘Trains, as they were and as they ought to be’ will give our friends some idea of the annoyance to which the present disarrangements on the Great North Western line subject the public. The arrival of the trains in London is far worse ― seldom less than an hour behind the proper time. The absurd system pursued by the Post Office, in ordering the mail cart to wait at Tring the arrival of the northern as well as southern mails, was fully shown on Thursday morning, when the London letters might have been sent on five hours earlier than those from the north, which were detained by an accident.” Bucks Herald, 19th August 1848 |

There was fierce competition between rival coach proprietors, which increased

following the opening of the London & Birmingham Railway to Tring in

October 1837. Of the many coaches passing through Tring the best known

were:

|

The Expedition ― An advertisement of 1789 stated “the Original London, Banbury, Buckingham, Winslow and Aylesbury elegant Post Coach. To Tring, Berkhamsted and Watford and setting out every morning from the Red Lion, Banbury, at 5 a.m. The coach carries four inside passengers.” Performed by Pratt, Stamp & Son, Graves |

A passenger luggage and parcel carrying service was also offered, with

no responsibility for anything above the value of Ł5.

The King William from Kidderminster and Leamington passed through

the Town on alternate days, changing horses at the Rose & Crown. The guard,

probably for the sake of distinction, performed on the key bugle:

|

“Tring. The new guard on the King William coach from Kidderminister, is an excellent performer on the key bugle. It is a very pleasing sound, as the coach enters the town in the early morning.” Tring Vestry Minutes, 1830 |

The Dispatch was better known as ‘Wyatt’s Coach’ after its

regular driver, James Wyatt. The Dispatch was the favourite of the

road and its punctuality was such that people were said to have set

their clocks by it ― but not all agreed that Wyatt was a good

timekeeper. According to the recollections of William Toovey, writing in

the King’s Langley Parish Magazine in 1895, “. . . . the driver, Wyatt by

name, used to stop very frequently for refreshment, and was known

occasionally to stop at the Windmill Inn, Bushey, and join in a rubber

of whist, whilst the coach and its passengers waited outside . . . .” Other than that, his affability to his passengers made it quite the

thing to go up by Wyatt’s Coach, and his habit of blowing kisses to a

lady fare was too delicately polite to give offence:

|

Tring Vestry Minutes |

Wyatt drove The Dispatch for 40 years. On his retirement, he was

presented with a handsome testimonial by some of his many friends and

passengers and it was said that he was only absent from his seat on one

day, when he went to give evidence at the murder trial of the keeper of

the Aylesbury toll-gate [Chapter

7]. By 1838,

The Despatch was operated by warehouseman John Honor Parker, and

ran daily from The George at Aylesbury to the Kings Arms, Snow Hill,

London.

The Old Union, another Parker coach ran from Buckingham, through Tring

and Berkhamsted to Snow Hill, London. After 1839, Parker began advertising his

vehicle as ‘The Union Dispatch’, presumably because he had either

rationalised or expanded his business. His later advertisements show

that he was making use of new technology in offering a carrying service

by rail in addition to his existing road transport.

|

|

|

Aylesbury News coach advert, 1839 |

The Good Intent ran from The Bell or The Plough at Tring to

The George,

Holborn, starting early at 7 a.m. Jack Hale, one of the guards on The

Good Intent, took over as driver of Tring’s first bus service, which

ran between

the town and the railway station.

The Young Pilot, rival to The Good Intent, ran from either Aylesbury or

Tring (also at 7 a.m.) to London. The fares were kept very low by the

keen competition, which created some excitement along the road, the

partisans of the one cheering their favourite as it drove up with “Good

Intent forever” and being answered the opposition “Throw him in the

river”.

After the London & Birmingham Railway opened, a particularly dashing coach was

driven from Watlington and Thame to Tring Station by a Major Fane, with

a team of thoroughbred horses which were changed at The Bell on Tring

High Street. Major Fane’s gallantry on the road left Wyatt in the shade,

and the bravura performance of his horses resulted, not infrequently, in

his coming in with a missing horseshoe, or even short of one of his team

through some mishap.

Among the wealthy sections of society, all of whom would own private

coaches, was one illustrious user of the road. It was not an unusual

sight in Tring to see the exiled King of France and his retinue rumbling

their way from Hartwell House in Aylesbury and on to London. Bored by

country life, King Louis VIII often sought pleasures in the capital, stopping

at various coaching inns along the way, particularly The King’s Arms in

Berkhamsted where he was said to have a ‘close friend’.

Stage Wagons were a prominent feature on the road, conveying the heavy

goods and the poorer travellers. They were huge cumbrous affairs with

eight or nine horses, and would carry as much as 10 tons. Joseph Hearn

of Aylesbury, referred to above, ran wagons as well as passenger coaches.

A stage wagon

From every town and village in the locality, smaller

conveyances, sometimes owned and driven by one individual, provided

carrying services to London and to all towns and villages within a wide

radius of Tring. For example, Kelly’s Post Office Directory of

1848 listed 69 such services operating from Aylesbury, with three of

these specifically mentioned as serving Tring. From Tring itself, wagon

operators included William Stevens from his house in Dunsley hamlet;

Joseph Hedges from The Plough; Thomas Rodwell from The Green Man; Crook

and Slade from The Bell; and Elliott, Horwood, and Parker & Co. from

the Rose & Crown.

Coachbuilders

Many skilled trades served the needs of the era of horse-drawn

transport, including those of the blacksmith, the wheelwright and, of

course, the coach builder. Such was the volume of traffic that even in

small market towns, crafts and businesses of this type could be found. An 1839 trade directory for Tring lists William Griffin as ‘a

wheelwright and gig maker’. Thirty years later, coachbuilder George

Parrott set up premises in Western Road. At the end of the century he

took A S Wright, his apprentice, into partnership and in 1910 the firm

became known as Wright & Wright when a cousin joined the business. Robert Wright,

who had served his apprenticeship at coachbuilders E. King &

Sons of Berkhamsted, remembered:

|

“I was apprenticed to this firm in the body-building department in June 1895. In those days we built not only trade carts and dog carts, but ‘Ralli’ carts, [6] governess carts, phaetons, broughams, landaus, and even a bus for Mr Williams of Pendley”. |

Tring High Street looking south.

The old Rose & Crown Inn, demolished in 1905,

is on the immediate right

The

Rose & Crown, located on Tring High Street, was the town’s largest coaching

inn. It was first recorded in Tudor times, but is probably older. Three

storeys high and with a central archway, a Georgian frontage was added

later thatstood flush with the line of shops facing the public

footway. Built to the general pattern of the times, the rear area

enclosed a large yard with stabling facilities and tack rooms. The Inn

was so busy during the heyday of the coaching era that extra stabling

was provided at The Plough opposite (now Anusia’s Café); above

the stables was a billiards room for recreational use by ostlers and

coachmen. One coach, The Good Intent, owned by The Rose

& Crown ran either from The Plough or The Bell.

The advent of the railways adversely affected the coaching trade, and in

1852 the landlord opened a booking office for the London and

North-Western Railway Company, and a horse-drawn omnibus provided a

service between the inn and Tring Station.

The advent of the railways badly affected the coaching trade, but in

1852 the landlord of the Rose & Crown opened a booking office for the London

and North-Western Railway Company and provided a horse-drawn omnibus service between the Inn and Tring Station.

The later Rose & Crown Hotel, with the station horse omnibus in the foreground.

In 1904, the townsfolk of Tring suggested to the then owner, Lord

Rothschild, that he might enhance the town with a

first-class hotel. This he agreed to build, his action being reminiscent of

a landed medieval lord who erected additional accommodation to house the

influx of travellers whom, by custom, were his guests.

|

|

|

An Act of Parliament Clock |

The new inn was

set back from the High Street and built in lavish style, with sports

facilities at the rear. When complete, the new inn was leased by Lord

Rothschild to the Hertfordshire Public House Trust, forerunner of Trust

House Forte. The hotel finally closed for business on 29th February

2012, and is now converted to private apartments.

The Bell ― the earliest written reference to this ancient inn is

1611, when Henry Geary was brought before the Justices for keeping The

Bell without a licence, and a few years later for being drunk.

Over the years the inn has been heavily restored, including the loss of

its fine carved hood over the entrance door, and during demolition of

some outbuildings in 1937 timbers were discovered dating to the 13th

century. One theory is that the inn acquired its name from a bell

foundry sited at the rear, but there is no evidence to support this.

According to local historian, Arthur Macdonald, during the time of the

construction of the London & Birmingham Railway, when hundreds of

navvies were employed on digging the Tring cutting, the Parish

Constables sometimes had to be called to the premises to sort out

various affrays.

Some of the through coaches changed horses at The Bell, and the archway

leading to the stable yard still can be seen. Folklore has it that flitches of bacon and cooked game were hung

from the beams under the arch. But if true, and considering this used to be a Right

of Way, in those times of serious hunger one wonders how safe

a storage space it might have been. Over the gateway extended a long room

that

was used for a variety of entertainments ― it was expected that coaching

inns could provide an assembly room, such as this, for a various

entertainments and meetings.

In 1797 an Act of Parliament was introduced which imposed a five

shilling tax on every clock. The Act was most unpopular and was soon

repealed, but during it was in force the response was to hang clocks on

the walls of public places, especially in taverns as landlords of larger

establishments welcomed the additional trade this could generate. Ever

after, these clocks become known as ‘Act of Parliament’ clocks. They had

weight-driven movements and plain dials of two to five feet in diameter,

and

one such is known to have hung in The Bell and another is still

in place in The King’s Head in Aylesbury.

The King’s Arms ― it is not known exactly when this public

house opened, but circumstantial evidence suggests some time during the

mid 1830s. It was built with adjoining stabling to house six or

more horses, with a hayloft above. The pub was named after the

‘Sailor King’ William IV who reigned from 1830 to 1837. Erected by

Tring brewer John Brown, his pub presented a more imposing appearance

than the cottage-style beer houses prevalent in the area, and has not

changed structurally in any significant way in the intervening years.

Brown chose the sites of the 11 pubs that he built or acquired in the

locality with care; his eye to maximising profits of The King’s Arms

gained from passing equestrian trade; both The King’s Arms and

The Britannia (another of John Brown’s pubs), faced west to welcome

travellers approaching the town from the Aylesbury direction.

Also, it is likely that he was aware that the western side of the town

would see considerable development, as proved the case in the

mid-Victorian period when new side streets, workshops and businesses

sprang up within the

Tring Triangle.

The Britannia stood at the junction

of Western Road and Park Road (a.k.a.

“Bottle

Cross”).

It is now a private house.

As time went by, the stable block became a corn merchant’s

warehouse, the hayloft was converted for use as a meeting room, and the

garden was sold for development. After near-terminal neglect in the 1970s,

the Grade II-listed Kings Arms again flourishes, with a reputation for

good ale and home cooking, while its

distinctive dark pink-colour scheme is a local landmark.

The former Royal Hotel, Tring Station

The Royal Hotel (formerly The Harcourt Arms), Tring

Station ― Although built in 1838 to serve the needs of passengers using

the new railway station, the hotel was also a Posting House, that is an

establishment where horses, a carriage, and a coachman could be hired,

as were The Rose & Crown and The Plough in the centre of

Tring. A large yard at the side of the premises surrounded by

ample stabling for horses, kennelling for hounds, and provision for

animals at livery, resulted in the hotel rapidly acquiring an excellent

name as a centre for local hunting activity. Fierce was the

competition between coach proprietors to provide transport to the new

railway stations, and local papers of the time carried many

advertisements proclaiming what excellent services they could offer.

A spacious ballroom at the rear supplied a suitable venue for gatherings

of the well-to-do of the district. The hotel and outbuildings

remain, but now all are converted to houses and apartments.

The Cow Roast Inn ― the present Cow Roast, a Grade

II-listed 17th century inn, was probably built on the site of a more ancient

establishment that stood by the roadside between Berkhamsted and Tring.

The name supposedly is a corruption of the original ‘Cow Rest’ or ‘Cow

Roost’, an area where cattle drovers and their beasts could break their

journey and rest overnight on their way to Smithfield Market in London. [7] The travel

writer John Hassell observed that the spot was . . . .

|

“. . . most erroneously named [Cowroast] . . . Here we saw herds of cows grazing, and observed a fresh drove of sucklers with their calves coming up to remain for the night, and we found, upon enquiry, that this inn was one of the regular stations for the drovers halting their cattle for refreshment; hence I should suppose, the proper name is the Cow Rest, or resting place of those animals, for along the road, and all the way through the breeding and grazing parts of Bucks, Bedfordshire, and Northamptonshire, there is a perpetual supply of cows passing to the capital . . . .” A Tour of the Grand Junction Canal in 1819, John Hassell |

Driving cattle long distances continued even into the age of the

railway, and drovers were required to have a licence and pay road tolls

― where they could not be avoided. Bones of a variety of animals

have been excavated around The Cow Roast, mostly of the cows

penned for the night in the surrounding fields. In 1806 these

fields were owned by Thomas Landon, the owner of The Cow Roast

and the wharf on the nearby Grand Junction Canal, and the stables of the

inn sheltered not only the horses used on Royal Mail coaches, but also

the heavier type that hauled narrow boats along the towpath.

――――♦――――

――――♦――――

FOOTNOTES

1. During the 19th century, some Cleveland Bays were bred with thoroughbreds to produce the

‘Yorkshire Coach Horse’, a now extinct breed

once native to England. It was a large, strong, bay or brown horse with

dark legs, mane and tail. It was said to be “a longer-legged carriage

horse with unmatched ability for a combination of speed, style, and

power” and “a tall, elegant carriage horse”.

2. The King’s Messengers are generally accepted to be the origin of the

postal service. The first recorded King’s Messenger was John Norman, who

was appointed in 1485 by King Richard III to hand-deliver the monarch’s

secret documents. Today, the Corps of Queen’s Messengers are couriers

employed by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to carry secret and

important documents to British embassies and consulates around the

world.

3. Sited in the dip in Christchurch Road.

4. Now ‘The Motorists’ Centre’.

5. Before the invention of the envelope, letters were folded and sealed

with sealing wax.

6. Small, two-wheeled vehicle similar to a gig.

7. There are numerous paths and lanes in the Chilterns that are enclosed

with ancient hedgebanks and steep sided ditches. These sunken tracks are

known as ‘hollow-ways’, and the depth of many that run down the Chiltern

escarpment reflect their origins as drove roads, in use over hundreds of

years to move livestock from local villages to their common lands. This

activity, called ‘droving’, also took place along main roads, with

livestock being driven to market.

――――♦――――

[Next Page]

|

|