|

CONTENTS

THE EVOLUTION OF MEDICAL CARE

IN THE 19th

CENTURY

QUACKS, SURGEONS AND DOCTORS:

Bartholomew Rolls

John Lloyd

William Firth

Arthur Ballie

Robert Jeninges Moody

Peter Richard Dewsbury

Edward Pope

Charles Percy Green Townsend

Richard Nicholson Lipscomb

Edwin Joseph Le Quesne

James Brown

William Ward Anderson

Charles Edward O’Keeffe

Henry Norman Knox

Edward Middleton-Brown

MEDICAL OFFICERS OF HEALTH:

Charles Edward Saunders

William Gruggen

Malcolm Gross

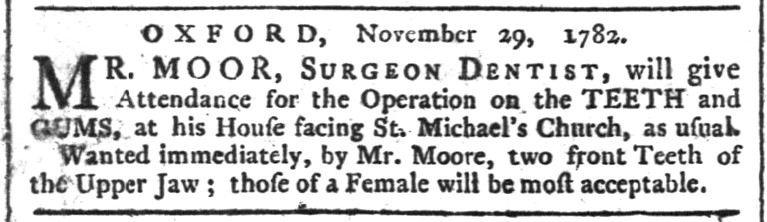

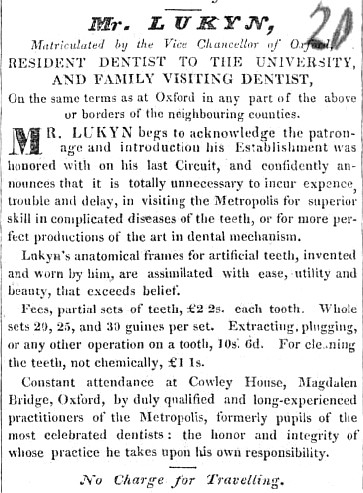

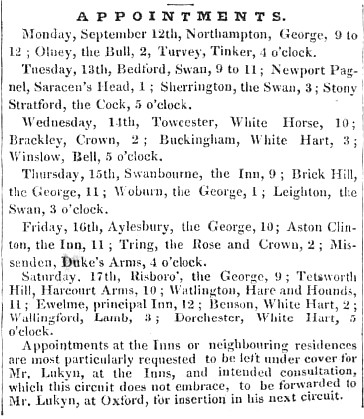

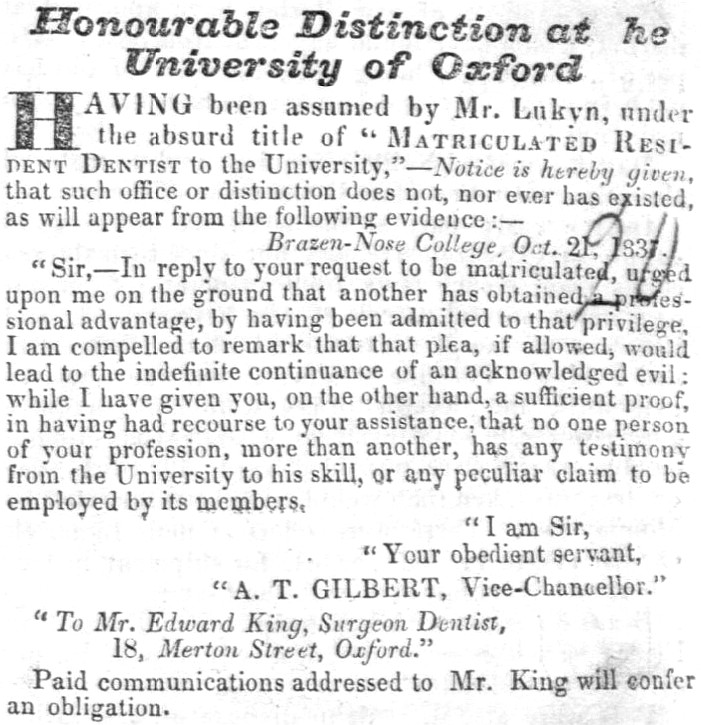

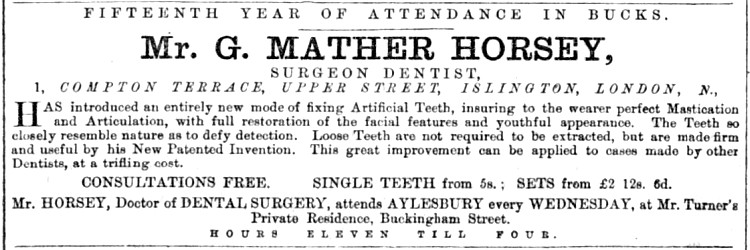

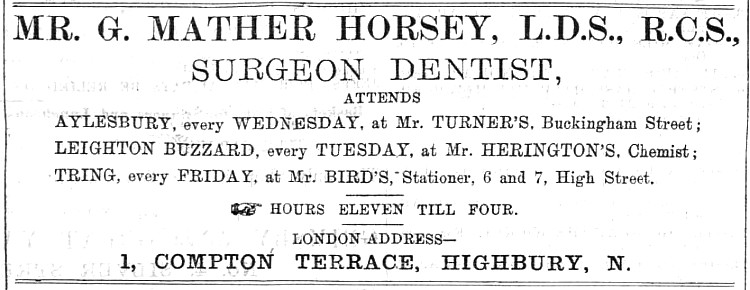

DENTISTRY

――――♦――――

THE EVOLUTION OF MEDICAL CARE IN THE 19th CENTURY

|

|

|

Bleeding a

patient |

By the end of the 18th Century (and for many years thereafter)

smallpox, typhus and tuberculosis were endemic, and cholera

alarmingly epidemic.

Medical care was a combination of chance and quackery. Treatments were

mainly botanical, although preparations that contained phosphorous

and heavy metals such as mercury, arsenic and iron were also

popular. Local doctors - in this era generally referred to

as ‘surgeons’ - might recommend a ‘change of air’ together with

vomiting and laxatives and/or the old favourites of bleeding or

leeches. Yet a century later medicine administered by

professionally competent practitioners would be available in a form

recognisable to anyone today - hospitals, stethoscopes, antiseptics,

x-rays, etc.

Broadly speaking, three main branches of medicine had evolved with

some overlap between them. ‘Physicians’ (who were rather thin on

the ground, especially in the provinces) advised and prescribed

medications, ‘apothecaries’ compounded and dispensed those remedies,

and ‘surgeons’ performed all physical intervention from bloodletting

to amputation. Of the three, physicians were held in the highest

esteem because they were university trained and held a degree in

medicine. The possession of this degree entitled them to the title

of ‘Doctor of Medicine’ or simply ‘Doctor’.

At this time there was no university training for the physicians’

less eminent brethren, the surgeons, who acquired their knowledge

through serving apprenticeships to experienced surgeons.

Nevertheless surgeons organized themselves into trade guilds, and

although earlier guilds existed, the roots of today’s practice stem

from the formation in 1745 of the Company of Surgeons. In 1800

this company was granted a Royal Charter to become the Royal College

of Surgeons in London, and it became customary for surgeons to

take the examination for Membership of the Royal College of Surgeons

and put MRCS after their name. However, because

qualification did not result in the award of a university degree,

licentiates could not style themselves ‘Doctor’ and so continued to

be addressed as ‘Mr.’, a tradition that continues to the present day

with female surgeons styling themselves ‘Mrs.’, ‘Miss’ or ‘Ms.’ as

appropriate.

Regulation of the medical profession in the U.K. - leading to what

in modern terms we would recognise as ‘general practitioners’ (GPs)

- followed the passing of the Apothecaries Act (1815) described as “An

Act for better regulating the Practice of Apothecaries throughout

England and Wales.”

The Act made it compulsory

for all new entrants to general practice to acquire the Licence of

the Society of Apothecaries (LSA).

It not only introduced compulsory

apprenticeship, but required apprentices to receive instruction in

anatomy, botany, chemistry, materia medica [1] and “physic”

in addition to gaining 6 months’ practical hospital experience.

The process could begin at age 14, but the minimum age for sitting

the LSA examination was 21. [2] Training typically took 7 years to

complete, with those completing the process successfully gaining the

qualification ‘Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries’ (LSA).

A large majority of general

practitioners, however, having acquired the LSA qualification also

acquired the MRCS, so that the dual qualification MRCS LSA gradually

became that of the general practitioner.

Oddly, just as it became compulsory for generalist medics to gain

the LSA qualification it seems they largely stopped calling

themselves ‘apothecaries’, preferring instead to use the term

‘surgeon,’ while the ‘apothecary’ gradually assumed the

modern term ‘chemist’ or ‘pharmacist.’ But despite the requirements of the 1815 Act, medical training remained

disparate. Thomas Bonner noted that “The training of a

practitioner in Britain in 1830 could vary all the way from

classical university study at Oxford and Cambridge, to a series of

courses in a provincial hospital, to ‘broom-and-apron apprenticeship

in an apothecary’s shop.’” [15]

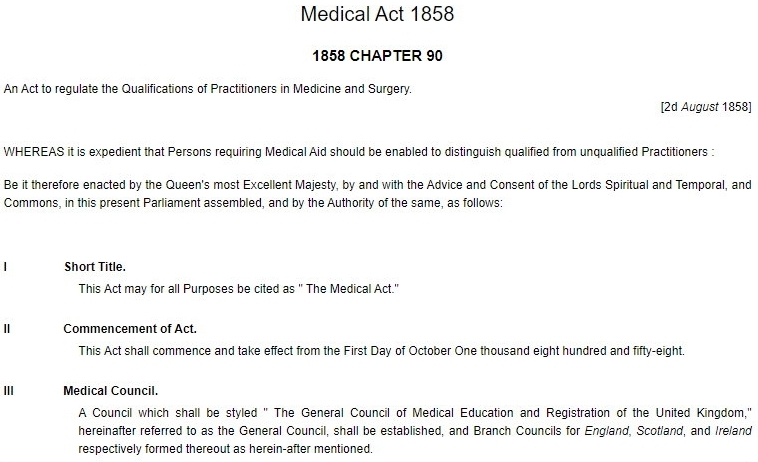

No significant advances were then made until 1858, when the

Medical Act established a recognisable form of healthcare

regulation. The Act’s overall aim was “to regulate the

Qualifications of Practitioners in Medicine and Surgery.” It

established the ‘General Council of Medical Education and

Registration of the United Kingdom’ (‘General Medical Council’

or GMC) as a statutory body and required it to create and publish an annual register of those with specified qualifications who

were entitled to practise medicine or surgery (those in practice

since before 1815 qualified automatically).

[9]

The first official

annual Medical Register showing place of education and qualification

was printed in July 1859. Any person not on the Register (including

anyone struck off) who was practising as a physician, surgeon,

doctor or apothecary was liable to a heavy penalty.

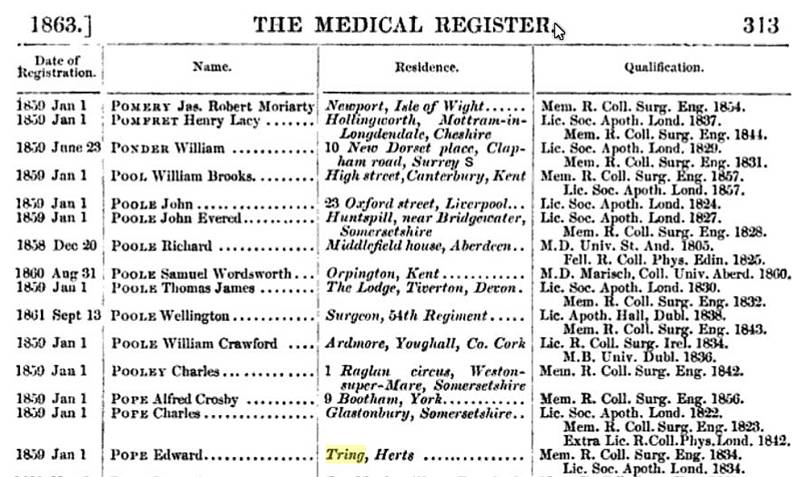

The

Medical Register entry for Edward Pope of Tring listing his

qualifications;

Member of the Royal College of Surgeons England (1834) and

Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, London, 1834.

In today’s terms Pope would be considered a general practitioner.

Thereafter medical training became more formal with the

establishment of medical schools, while the number of doctors

increased considerably, from 14,415 physicians and surgeons in

England and Wales in 1861 to 35,650 in 1900. Because the LSA did

not cover surgery, it became the norm at the end of an

apprenticeship for surgeon-apothecaries to take the Royal College of

Surgeon’s membership examination (MRCS) at the same time as the LSA.

So the main qualifications that dominated the profession in the 19th

century became, typically, LSA and MRCS for a generalist (the

precursor of our present day family doctor); and typically MD (a

university graduate in medicine) and FRCS (Fellow of the Royal

College of Surgeons) for the increasing number of hospital based

specialists in medicine or surgery respectively.

――――♦――――

QUACKS, SURGEONS AND DOCTORS

|

|

|

The Quack. |

Newspapers of the Georgian and Victorian era often contained a

smattering of advertisements for bizarre medications. The quacks

selling these products sometimes colluded with newspaper publishers,

who not only ran the vendors’ advertisements in their pages, but

often - for a cut of the profits - sold the remedies on the

printers’ premises. An example of quackery occurred in December,

1790, when an advertisement appeared in the Northampton Mercury

that commenced as follows:

HYDROPHOBIA:

or, a cure for the bite of a mad dog.

PAUL

NEWENS,

of Wing, in the County of Bucks, is the sole preparer of a medicine

that has never, in any instance, failed to eradicate the dreadful

Malady occasioned by the bite of a mad dog, and which has been

prepared with universal success for these last forty years and

upwards, by the said Paul Newens . . . .

The rabies advertisement - for rabies was the disease in

question - goes on to claim that . . . .

ELIZABETH

KEMPSTER,

servant to Mr. William Stevens, of Marsworth, farmer, had every

appearance of hydrophobia, but on Paul Newen’s medicine being

administered, was in the course of four hours entirely released and

cured.

The advertisement concludes with the names of three individuals able

to testify to the efficacy of this miracle remedy, one of whom was “J.

R. Fawcett, surgeon of Tring.” Fawcett was probably as bogus as

the remedy, for I can find no further mention of him; but bogus or

not, Fawcett is the earliest name connected with medicine in the town

to appear in the press. Today, the promotion and advertising of

medicinal products in the U.K. is governed by advertising laws and

the Human Medicines Regulation 2012, which is enforced by an agency

of the Department of Health and Social Care, the ‘Medicines and

Healthcare products Regulatory Agency’.

――――♦――――

BARTHOLOMEW ROLLS

It is very likely that there were earlier medical practitioners in

Tring - for instance Tring’s burial register records that “Mary the wife of

Jno. Lacy Dr. in Physicke buried March 16th” (1710 or 11) - but

John Lloyd is the first I can trace about whom anything at all is

known. On the 17th April, 1797, it was recorded in the Tring Vestry

Minutes that “The Vestry have agreed to give Mr. Rolls Surgeon

thirty pounds for the year for all cases of Physic and surgery for

the poor.” Some years later a notice appeared in the

London Gazette,

the official public record, to the effect that . . . .

“The partnership lately carried on between Bartholomew Rolls

and John Lloyd

[below], of Tring, in the Country of

Hertford, Surgeons, Apothecaries, and Man-Midwives, is this day

dissolved by mutual consent, as from the 10th April last; and all

accounts relating thereto will be settled by the said John Lloyd,

who will in future carry on the above Professions in Tring

aforesaid, on his own account. Witness our hands this 5th day of May

1815.”

Other than a brief mention in Tring’s Vestry Minutes, no record of

Rolls’ work in Tring appears to have survived. However, an

impression of one aspect of his work – also shared by others

referred to in this paper – comes from his appearance as an

expert witness at a coroner’s hearing where cause of death needed to

be established. This case concerned Sidney Sadler, a printer, who died following a

pugilistic contest in the Islington area of

London. Sadler, reputed to be a quarrelsome individual,

had challenged one John Watts to fight, a challenge that Watts accepted.

Having fought a dozen rounds, Sadler received two blows, one being

to the throat, after which he fell to the ground. Having by then lasted half an

hour, the contest finished. Later that evening

Bartholomew Rolls was called to attend to Sadler, whom he found

sitting in a chair in a public house “quite dead”. Rolls then . . .

.

“. . . . opened a vein in each arm, and then the temporal artery.

On opening the body, he found the marks of a blow (not severe) on

the left side; on opening the head, he found that one of the

arteries of the brain was ruptured, and a great effusion of blood,

which he considered produced apoplexy.

Coroner. ― Did that rupture proceed from a blow?

Witness

[Rolls]. ― It is impossible to say ― it might have proceeded from a blow; or

passion would have produced the same effect.

Juror. ― Would the blows on the jaw have produced the same effect?

Witness

[Rolls]. ― No, certainly not; the body was in a very healthy state, and

they having fought on grass I am inclined to think his death was

caused by apoplexy . . . .

. . . . The Jury then retired to view the body, and, after some

discussion, returned the following verdict: ― ‘The deceased died of

apoplexy, caused by irritation of mind in fighting.’”

Morning Advertiser

23rd October, 1823

On the 8th July, 1826, it was announced in the deaths column of the

Northampton Mercury . . . .

“Lately, in the 58th years of his age (at the house of his son in

law, Mr. Cheney, Aylesbury), Bartholomew Rolls, Esq. of

Pentonville, Middlesex, formerly surgeon of Tring Herts. ― He was

greatly respected in life, and his death is much lamented by his

family and friends.”

――――♦――――

JOHN LLOYD

The grave of John Lloyd,

surgeon, Tring Parish Church.

At the front of Tring Parish Church on its western side stands a

weathered gravestone that bears the barely legible inscription . . .

.

“Sacred to the Memory of John Lloyd Surgeon of this Town who

died November 12th 1825 aged 39 years leaving a Widow and six

Children to lament his irreparable loss.

This stone was erected by a few friends to whom his professional

Talent and private Virtues had justly endeared him.”

Lloyd’s headstone, having been erected “by a few friends”,

gives a hint that he might have been living in straightened

circumstances at the time of his death, a suspicion strengthened by

an entry in the London Gazette (22nd February, 1817)

requiring Lloyd - “Surgeon, Apothecary, Dealer and Chapman” -

to appear at the Guildhall, London, there to make a full disclosure

of his estate and effects. The notice also invited Lloyd’s

creditors to come prepared to prove their debts, for he had been

declared a bankrupt - that said, the Gazette announced his

discharge a few weeks later. What little is known about Lloyd was

that he had been in partnership with Bartholomew Rolls at Tring,

a partnership that was dissolved in 1815, while his death notice

refers to him being “a very eminent surgeon, formerly a partner in the firm

of Messrs. Williams and Lloyd at Brecon.”

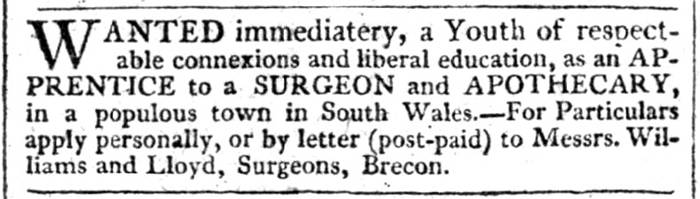

In the case of Lloyd, Williams and Bartholomew Rolls it’s difficult

to know exactly what training and skill their use of the description

“surgeon” implies. One can be sure that surgery, both then

and now, involved cutting into the body, but there the comparison

with today’s practitioners ends. What knowledge surgeons of the

time had of surgical procedures will have been acquired through

apprenticeship to a surgeon, who in their turn had also acquired

their knowledge through on-the-job-training. In this context it is

interesting to note that Lloyd and his erstwhile partner Williams

had themselves advertised for such an apprentice . . . .

Hereford Journal,

25th January 1809.

The 1823 edition of Pigot’s directory for Tring lists two surgeons,

William Firth and John Lloyd under the heading ‘Professional’, while

the 1825 edition introduces the heading ‘Surgeons’ under which are

listed two partnerships, Firth & Ballie, and Lloyd & Dewsbury.

Although not shown as being in partnership it appears that on at

least one occasion Firth and Lloyd worked together:

“The last week has added two cases to the many incidents which have

occurred on the Grand Junction Canal

[later renamed the Grand Union Canal]. A woman and her daughter, on

their way to Uxbridge in a boat, were, in consequence of the boat

striking violently against the sill of a lock, thrown down with

violence, and a quantity of nails in bags falling upon them, they

were severely bruised, and the woman’s wrist so dreadfully

dislocated, that amputation seemed indispensable. Mr Firth,

surgeon of Tring, however, with a laudable desire to preserve the

limb, called in the assistance of Mr. Lloyd, and the

dislocation was reduced, and hopes are entertained of the poor woman

doing well. The girl, beside suffering very severe bruises, was

very near losing the sight of one of her eyes, a nail having

penetrated just under it.”

Evening Mail,

1st November 1824

――――♦――――

WILLIAM FIRTH

I have been unable to discover anything about William Firth, other than his

entries as a surgeon in the 1823 and 1825 editions of Pigot’s

Directory for Tring.

The Morning Herald

contains a report of Firth attending the victim of a road traffic

accident . . . .

“On Saturday evening last, about nine o’clock, a son of Mr. Walter,

of Wilstone, accompanied by a labouring man of the name of Archer,

were proceeding from Tring towards Wilstone in a taxed cart. The

horse took fright and ran away to the top of the bridge, crossing

the Grand Junction Canal at Little Tring, when the back tree of the

harness gave way, and they were both precipitated out of the cart

with great violence down a steep hill. Young Walter was thrown

against some railings, and fortunately escaped with only a bruise in

the side, from the effect of which he is recovering; but Archer

pitched on his head upon the ground, and the wheel of the vehicle

went over his leg; his scalp was cut open in a dreadful manner, and

he was taken up senseless, and apparently dead, the wound bleeding

profusely; however, he revived, and by the prompt assistance of

Mr. Firth, a surgeon of Tring, was sufficiently restored to be

conveyed home, where he now lies, suffering dreadfully from the

accident, but great hopes are entertained of his recovery.”

Morning Herald, 25th August, 1825

I was unable to locate anything further about this accident. As for

Firth and his partner Ballie, neither appear

in the 1839 edition of Pigot, the next edition available to

me.

――――♦――――

ROBERT JENINGES MOODY

In Pigot’s directory for 1839,

under SURGEONS

appears one

“Moody Robt. Jeninges” whose practice was at Frogmore House (once located

in Frogmore Street, Tring, long-since demolished). Moody appears to have been

born in Great Missenden on the 26th August 1807, married Charlotte

née Cutler, and died at Tring in January 1842. The National

Archives holds the will of one Robert Jeninges Moody,

“Druggist of Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire,” but dated 1st June 1842.

Whether these references relate to the same person I cannot say,

but I can find no other information relating to a surgeon of that

name practicing in Tring.

――――♦――――

ARTHUR BALLIE M.R.C.S.

In June, 1830, Tring surgeon Arthur Ballie attended Samuel Budd, the

victim of a road accident possibly caused by his carthorse shying.

Budd later died of his injuries. In the absence of any

method for assessing the extent of

the victim’s internal injuries, the press

report of the inquest illustrates both the surgeon’s speculative

diagnosis and the lack of any effective

treatment in his repertoire:

“An inquest on the body

of Samuel Budd, was held on Wednesday, 23rd June

[1830], before F.

J. Osbaldeston Esq., at the Rose and Crown Inn, Tring . . . . Job

Nutkins said he works for Mr. Stevens, Tring Grove. Knew deceased;

saw him alive on Monday morning, about seven o’clock, sitting up on

the road. Saw a cart lying on the road; the cart had been turned

over on the near wheel; the horse was about six yards from the cart;

the shafts of the cart were broken . . . . deceased was about five

yards behind the cart . . . . spoke to deceased, but he did not

answer; there was blood on his temples, though not much . . . .

“Mr.

Arthur Baillie, surgeon, examined

[by the coroner], said he was sent for about seven on Monday morning to see

deceased who was at his own cottage in bed. Deceased

complained of pain in his chest, and stomach; his breathing was very

laborious. Witness

[Baillie] found a great depression in the lower part of the sternum; and a

fracture of the large rib on the left side. There were also

slight marks on the left side of the head; but not sufficient to

produce death. Witness was of the opinion that the concussion

of the chest produced death. Deceased’s extremities were cold.

Witness gave him some brandy to stimulate him and subsequently bled

him, but he gradually got worse, and died about nine yesterday

morning. Verdict accidental death.”

Bucks Gazette,

26th June 1830

Ballie appears again in the coroner’s court in September 1831 in a

case reported in the Bucks Gazette that illustrates how

helpless the surgeons of the time were at treating serious injury.

The circumstances of the death of Thomas Lovett are summed up in the

verdict of the coroner’s jury:

“The jury returned a verdict in substance as follows: ‘That the said

Thomas Lovett, on the 1st Sept., 1831, received a mortal wound of

the depth of four inches, and of the breadth of one inch, in his

left thigh, by a loaded gun, which he had been carrying when in the

act of sporting, having gone off accidentally, and the contents

thereof having penetrated his thigh, of which wound the said Thomas

Lovett on the said 1st Sept. died.’ The verdict was accompanied by

this observation - ‘But the jury are of the opinion that too large

quantities of opium were injudiciously administered to the said

Thomas Lovett.’”

Bucks Gazette 10th September, 1831

Following the gunshot injury, Lovett was taken to his house and

Ballie was sent for. Two other surgeons, Ayckburn of Wendover and

Rumsey of Chesham, arrived later. Lovett, who

complained of great pain, had received a large lacerated wound on

the back of the thigh. Ballie stated to the coroner that:

“On

introducing my fingers into the wound, I found it plugged up with

coagulated blood, and the thigh bone was shattered, the upper

portion of which protruded through the wound . . . . the patient

complained of extreme pain; and as soon as I could procure pillows,

I placed the limb in a more comfortable position. . . . The deceased

repeated his wish to have something administered to him to ease his

pain: I sent home for a draught, directing thirty drops of tincture

of opium to be used in syrup and camphor mixture; also for a small

phial of tincture of opium and compound spirits of ammonia.”

Before the opium arrived, Ballie treated the patient’s thirst by

administering “to the patient some tea from the spout of a teapot.”

In consultation with the other surgeons it was agreed that

amputation would be necessary if the patient rallied. One of their

number, Mr. Ayckburn of Wendover, administered pain relief in the

form of opium to a total dose of 8 grains, [16] but

Lovett grew increasingly weak and died. Ballie informed the coroner

that:

“I am of the opinion that an excess of opium was given

according to the circumstances of the case, and that the sudden

termination of the case by the death of the patient was attributable

to the opium acting upon the nervous system of the patient, who had

not rallied from the first shock . . . death was accelerated by the

treatment. The patient did not rally sufficiently during the day to

warrant amputation.”

Considering the primitive surgical techniques

of the time, I think it highly doubtful that amputation would have

produced a beneficial outcome.

During the hearing Ayckburn informed the coroner that he was

qualified by experience rather than examination - “I am not a

member of the College of Surgeons, nor a Licentiate from the

Apothecary’s Company; I have been in practice 25 years.” Ballie,

on the other hand, was at least partly qualified, being a member of

the Royal College of Surgeons.

――――♦――――

PETER RICHARD DEWSBURY Sh, L.S.A.

Little is known about Dewsbury the man. Born at Chester, the

1851 Census locates him and his family (wife, daughter, medical

assistant, cook, groom and housemaid) living on Tring High Street.

He was then 48 years of age so his death

in 1857

(cause unknown)

came at the comparatively early age of 54. In the Census Dewsbury

uses the then fairly novel term ‘General Practitioner’ to describe

his occupation, and gives his qualifications as Sh (unknown) and LSA

(Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries).

Dewsbury appears in the press periodically, generally as an expert

witness in the cases that required a medical opinion on cause of death. Such was the case in a pugilistic

contest that took place at Wigginton in December 1827. The

rules of such contests allowed for a broad range of fighting

including holds and throws of the opponent. A round ended with

one contestant being downed by a punch or

throw, whereupon he was given 30 seconds to rest and eight

additional seconds to return to the centre of the ring to continue. Consequently,

a fight did not end after a limited number of rounds, but when one participant

was unable to continue.

Such a contest between James Kindell and John Olliffe resulted in

the death of Olliffe.

Kindell eventually stood trial at the Hertford Assizes accused of

“feloniously killing and slaying John Olliffe, on the 11th of

September, at Wigginton.”:

“Harding Dell

[a labourer]

stated, that, on the day in question,

there was a feast on Wigginton-green, at which he, the prisoner, the

deceased, and about 100 other persons were present. In the course

of the day, the prisoner and the deceased talked about fighting.

The deceased stripped first and on being advised not to fight, said,

‘he must, for he was put upon,’ and then called out to the prisoner,

‘Come, Jemmy, I’m ready for you.’ They then fought: it was a fair

stand-up fight, and the prisoner had the worst of it for several

rounds. At length he struck the deceased a severe blow on the left

side, which threw him: but they fought three or four rounds

afterwards, when the deceased gave in, and died in half an hour.

The body was taken to the house of the sister of the deceased, and a

surgeon sent for . . . .

. . . . Mr. Dewsbury a surgeon at Tring saw the body about eight

o’clock on the evening of Tuesday; found him dead; had the clothes

stripped off the body; on the left side of the chest, in the

abdomen, discovered a considerable bruise, and some slight bruises

on the left side of the neck, a fracture, or incised wound; did not

attempt to bleed him; attended on the morning of the inquest, and

opened the body; on opening the body found a considerable quantity

of coagulated blood in the cavities of the abdomen; on removing that

fluid discovered a rupture of the spleen, which was quite sufficient

to account for the man’s death; believes that violent contraction of

the muscles of the spleen might have produced the rupture, but

believes this was caused by a violent blow, which in his opinion was

the case.”

And then took place a curious turn of

events.

Dewsbury was proceeding to state that he had examined the

body of “a man” on the day in question

. . . .

“. . . . when,

on being asked whether he knew the name and person of the deceased,

he replied in the negative; and no witness being forthcoming to

prove that the body examined by Mr. Dewsbury was the body of the

deceased, John Olliffe, the Learned Judge interposed, and said that

a verdict of acquittal must be taken, as there was no evidence of

the identity of the body, or, consequently, of the cause of the

death of the deceased.

The prisoner was accordingly acquitted.”

Derby Mercury, 12th December, 1827

When the London & Birmingham Railway opened in September 1838,

several publishers saw an opportunity to cash in on this novel form

of transport by publishing guide books to the line. As passengers

progressed along it, with the help of their travel guide they could compare the view from the

carriage window

with the writer’s description of the countryside and

the towns through which the line passed (or, in the case of Tring,

passed at some considerable distance).

Osborne’s Guide (1838) gives a good potted account of Tring

at the time including a reference to its Silk Mill, most of which

remains in Brook Street. The “fish pool”, which at the

time was much larger than today, was originally used as a pond from

which water was drawn to power the mill’s machinery, but by the time

of

Osborne water power had been replaced by a steam engine. It

is interesting to note the writer’s observations on the health risk

posed by the pond:

“By the side of the mill is the temporary residence of the

proprietor, with a conservatory, and an extensive fish pool, the

rather stagnant nature of which must give rise to much of pernicious

effluvia

[an unpleasant or

harmful odour or discharge]; and considering that Tring is seldom or never without ague

[fever],

and as the malaria

[3] is generally found to result from pools of this character,

several of which are in the vicinity, it is to be hoped that, ere

long, the proprietors of these sources of pestilence will evince

sufficient morality and intelligence to compel the removal of a

nuisance so highly dangerous to all the neighbourhood; actually

fatal to some, and deeply injurious to the lives and happiness of

many innocent people.”

Osborne goes on to describe the effects of the “pernicious

effluvia” on the mill workers:

“In the mill there are almost always persons whose haggard looks

evince their having lately been afflicted with this terrible

disease, evidently consequential to placing employed in a building

through which there must, despite all precaution, be continually

circulating a portion of the vapour from the pool beneath; the adult

patients look bad enough; but the sight of the little children who

have lately suffered, with their wretched countenances, death-like

colour, and tottering frames, cannot but make the heart of any

humane person burn with the keenest anguish.”

And it is here, at the Silk Mill, that we again encounter Mr.

Dewsbury, surgeon of Tring:

“The proprietors of the mill pay Mr. Dewsbury, Surgeon, of

Tring, £20 a year for inspecting the persons employed in the mill,

to insure cleanliness and freedom from disease: after this evidence,

we must not attribute the presence of the injurious marsh to a want

of feeling in the proprietors, but rather to a want of information

on the subject.”

Whether Mr. Dewsbury delivered any real value for his fee is

doubtful. From what Osborne says, those suffering the “ague”

exhibited symptoms that were plainly evident, while it is

unlikely that Dewsbury had any effective remedy at his

disposal to combat the condition. The affliction, whatever it was, was not airborne as was

thought at the time, but was more likely to have been contracted

from well water polluted by waterborne bacteria

stemming from inadequate (or non-existent) sanitation. Tring had to

wait until the 1870s to receive a mains supply of clean drinking

water, and even then many would not pay the water company’s fee for connection

to it.

Another case that involved the newly opened London and Birmingham

Railway occurred in October 1838 and caused something of a scandal. The

President of the

Royal College of Physicians, Sir Henry

Halford, had invited a friend, George Lockley, to spend some time

with him at his home in the country. Shortly before arriving at

Tring Station on their journey north, Lockley suffered an “apoplectic fit” (a

stoke). The report in the Morning Chronicle continues:

“The train having arrived, the officers were beckoned to one of the

carriages, and thus accosted by a venerable-looking personage

within: ― ‘Officer, here is a very respectable gentleman,

extremely ill. Do take great care of him, and send off immediately

for medical advice’ . . . . Did this friend even get out of

the carriage? He did not, but, frightful to relate, actually flew

off with the train, leaving his senseless and speechless friend in

the open road, and supported in a chair, placed on the cold wet

clay, by the hands of the official strangers! Mr. Lockley was

treated with marked humanity and attention by the officers of the

railway who conduct the business of that station . . . .”

What then transpired varies

between newspaper reports, but according the The Atlas:

“In about an hour Mr. Dewsbury arrived, and bled Mr. Lockley,

who was removed to the town that evening and expired on the 20th

ult. This is Sir Henry’s own statement, called for by the indignant

feelings of the profession at his having abandoned his friend and

companion, and not attended to him, and applied himself the

resources of his art.”

In response to this charge of neglect, Sir Henry claimed that the

rules of the College of Physicians prohibited from bleeding

(bloodletting), a job that called for a surgeon; as a physician,

Halford could only prescribe. Would bloodletting have helped

Mr. Lockley? Bloodletting was the withdrawal of blood from a

patient to prevent or cure illness and disease, or so it was

believed based on ancient theory. But in the days when doctors

had little in the way of effective treatment there was a need to be

seen to be doing something to treat the patient. Even if there was

no proven medical benefit to be derived from the procedure, its

placebo effect should not be overlooked. Since the modern era of

‘evidence-based’ medicine, the practice of bloodletting has been

consigned to the dustbin of discarded treatments. As for Sir Henry,

the scandal surrounding Lockley’s death did him no lasting damage

professionally, for he continued to serve as President of the Royal

College of Physicians until his death in 1844.

――――♦――――

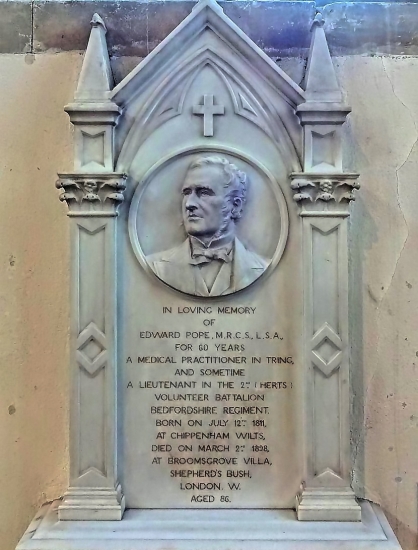

EDWARD POPE M.R.C.S., L.S.A.

In the graveyard extension to the north of the parish church is the

grave of Edward Pope M.R.C.S., L.S.A., “SURGEON IN THE TOWN

FOR SIXTY YEARS”. He must have been held in considerable esteem by the community, for

inside the church is a memorial plaque.

|

|

|

|

The Pope

family grave, Tring Parish Church. |

Memorial

plaque to Edward Pope, Tring Parish Church. |

Edward Pope (1811-1898) was born at Frome, Somerset. On leaving

school he was apprenticed to his uncle, Dr. Roberts, of Burnham,

Bucks. He studied at Guy’s, St. Thomas’s, and Webb-street,

qualifying as M.R.C.S. and L.S.A. in 1834. Pope settled in medical

practice in Tring in 1837 in succession to the late Mr. Firth, and

married in the following year. Sadly, death was a frequent visitor

to the Pope household, claiming his wife Catherine in 1875, two

daughters and two sons, all in their childhood or infancy. His son,

Dr. Harry Campbell Pope survived him (d. 2nd January, 1906).

During his career, Edward Pope’s name frequently appears in the

local press, generally in connection with hearings before the

coroner when cause of death needed to be established, but

occasionally a report crops up that is out of the ordinary.

The first took place in Aylesbury in February 1847, when an

event took place that was to have an extraordinary impact on surgical

procedures

carried out in the locality. [4] This from the Bucks Herald:

“On Tuesday last the marvellous effects of the inhalation of the

etheric vapour were developed in three extraordinary cases: — the

amputation a leg, — the removal of a tumour from the shoulder,— and

the extraction of a finger nail, and subsequent application of

strong nitric acid as a caustic. The operations were in each case

most successfully performed, and without the slightest sense of

pain, in the presence of a large number of gentlemen, both of the

profession

[including Edward Pope] and of those

interested in witnessing the wonderful effects of ether, in the

amelioration of human suffering in surgical operations.”

In an age when the serious fracture of a limb usually resulted in

amputation, and with no pain-relief available, lightning-quick

surgery shortened the almost unimaginably horrific trauma of the

amputation. The screaming patient was typically held down on a

wooden bench by “dressers”, who would also assist with ligatures,

knives and dressings. Although not realised at the time,

lightning-quick operations also minimised the exposure of tissue to

infection.

In the case witnessed by Pope, the patient had sustained injury by slipping on a

frosty surface, in consequence of which he . . . .

“. . . . sustained a compound fracture of both bones of the leg. He

was conveyed to the Bucks Infirmary and for some time his life was

in danger from severe erysipelas taking place, and abscesses forming

throughout the upper part of the leg and thigh, precluded any

immediate operation. A further delay was subsequently permitted

with the view of saving as much of the limb as possible, but at

length it was found necessary that amputation should take place . .

. .Shortly after twelve o’clock the patient was brought into the

operating roam, and being placed on the operating table, the

administration of the ethereal vapour was then conducted by Mr.

Robert Ceely . . . . As it was intended to prolong the influence,

the ether was administered gradually, and so as to cause not the

slightest inconvenience to the patient. The full effect was visible

in five minutes, when the patient, being in a perfect state of

insensibility and muscular relaxation, the operation of removing the

limb was commenced by Mr. James H. Ceely, and in one minute and a

half the limb was separated, during which time not the slightest

sensibility or motion was apparent. The securing of more more

vessels than usual, and the final dressing of the stump, farther

occupied nine minutes and a half, the whole operation thus being

performed in 11 minutes.”

Bucks Herald 27th February, 1847

There is no further mention of George Kean in the following weeks’

papers, perhaps an indication that he did not succumb to

infection that in the days before antiseptic surgery claimed the lives of

many who had undergone surgical procedures.

Another unusual event attended by Pope occurred in January 1853. It

concerned clairvoyance, or the ability to gain information about an

object, person, location, or physical event through information

sensed with the mind. And here we meet another Tring

personality,

Gerald Massey, a self taught poet whose writing

attracted considerable attention during the mid-19th century.

Money was for ever short in the Massey household and to help balance

the books the poet would hold public exhibitions to exploit his wife’s talents as a noted clairvoyant. At one such exhibition

held at

the Commercial Hall in Tring, Rosina Massey commenced by reading from any

and every book or paper passed to her from the audience, but with her

eyes effectively covered. In order to prevent collusion or

deception, the audience had been asked to provide their own papers

for Rosina to read. She was then placed by Massey into a “mesmeric

sleep” (i.e. placed under hypnosis) and although papers in some

very small type were handed to her, according to the Bucks

Advertiser (21st January 1853) in almost all instances she read

with her eyes covered to the perfect satisfaction and astonishment

of those present.

Edward Pope, who was in the audience, subsequently wrote to

the Editor of the Bucks Advertiser proclaiming Mrs Massey to

be a fraud and concluding with the pertinent question “Why

accept a shilling or eighteen pence for exhibiting manifestations of

a power which, skilfully applied, would make them [the Masseys]

rich beyond the dream of avarice?”, to which one of paper’s

readers replied [to Pope] “Why, Sir, you mesmerise upon a large

scale, and then find fault with a poor soul that only trades now and

then for a crust.” There was probably truth on both sides of

that argument.

Hydrophobia – or rabies, to use its common name –

was a real threat to

life at a time before this dread disease was brought under control. Pope must have known

the inevitable outcome of rabies, for there was no vaccine at the

time with which to fight it [5]:

“DEATH

FROM

HYDROPHOBIA

AT

WIGGINTON.—

It will be remembered that about two months ago a dog supposed to he

rabid was running about in the neighbourhood of Tring for some

considerable time, and creating much alarm, until it was at last

shot by Mr. E. C. Knight of Tring. Unfortunately, however, the dog

was not killed until several other dogs had been bitten, and two or

three persons also. One of the latter was a boy named Richard

Turney, aged ten, living at Wigginton, who took the dog up in his

arm and fondled it, when it bit him under his chin. Hearing

afterwards that the dog was supposed to be rabid the day after he

was bitten he went to Mr. Pope, surgeon of Tring, who

cauterised the wound.

On Friday week the lad‘s father applied to Mr. Pope with respect to

his son, who was unwell. Mr. Pope went at once and visited the boy,

who, in his opinion, showed symptoms of hydrophobia. He sent him

some medicine, saw him again the next morning, and advised his

removal at once to the West Herts. Infirmary. This advice was acted

upon, but the poor led gradually got worse, and died there on Sunday

night.”

Bucks Herald

27th October, 1877

In addition to his role as a general practitioner, Pope also held

public appointments as ‘Certifying Surgeon of Factories’, [6]

‘Medical Officer for the Tring District of the Berkhamsted Union’,

and ‘Medical Officer for the Aston Clinton District of the Aylesbury

Union.’ [7]

Sanitation at the time was poor due principally to

the lack of safe sewage disposal. Thus, in the absence

of a mains supply of clean drinking water, water drawn from wells and from

brooks was often polluted with faecal matter, which gave rise to the

spread of waterborne diseases such as dysentery, typhoid and cholera. Two reports from 1875

illustrate Pope’s role in combating the problem.

In the first, the tenants of a row of cottages at Aston Clinton were

summoned under the Sanitary Act (1866) to show cause why a well, the

water in which was so polluted as to be injurious to health, should

not be stopped up. The Inspector for the Rural Sanitary Authority

produced for the magistrates a sketch of the premises and pointed out the

different drains, cesspools, &c., all of which were unsealed. As a result

they drained into the well, thus polluting the

water. At the hearing . . . .

“. . . . Dr. Pope of Tring, medical officer, said — I know this

property at Aston Clinton. I have examined the water of the well,

which contains a large amount of organic matter and chloride, which

can only come into it from sewage. The water would be injurious to

health, if drunk, and at some seasons, when low, it is not even fit

for other domestic purposes.

. . . . In reply to the Bench, the Inspector for the Rural Sanitary

Authority said complaints had been made also of the pollution of the

brook water by ducks and cattle . . . .

Dr. Pope suggested the making of a tank for the brook water, at a

point a little higher up than the cottages. He accounted for the

contamination of the well by the overflowing of the cesspools from

heavy rains, and possibly also to the inhabitants themselves

throwing slops into it. He had a sample of the water analysed some

time ago by Dr. Saunders of London, one of the analysts of the

Metropolitan Sanitary Authorities, and he told him it was worse than

that of the Thames at London Bridge.”

Bucks Herald 8th May 1875

Some further remarks were made by the magistrates as to the advisability

of having a fresh well sunk, in reply to which one of defendant said

that their wives were too lazy to draw the water if a well was sunk,

preferring instead to go to the brook which is nearer (referring to

a brook running in front of the houses). In conclusion the Bench

ordered the well to be stopped up for six months, but made no order

regarding the brook. How public health benefitted from this ruling

in the longer term isn’t clear.

The second case also involves cottages at Aston Clinton, this time

with unhealthy arrangements for drainage and the removal of human

waste:

“SANITARY

SUMMONS.—George

Keene was summoned by the Sanitary Authority of the Aylesbury Union

[7] for not complying with a notice given him to repair the drains

of some houses at Aston Clinton, of which he is the owner. Mr.

Newman said he was the inspector of nuisances for Aston Clinton, and

produced authority to take proceedings by minute of the Sanitary

Authority of the Union. He further produced plans of the property,

showing the state of the drains, and also a copy of the notice

served upon the defendant. He said the defendant refused to make

the alterations required, saying that they would do very well. He

was the owner of ten cottages, in one of which he lived. The drains

were in a very bad state.

Mr. Edward Pope, surgeon of Tring, deposed that he had

inspected the drains referred to on Tuesday last. The surface drain

behind the cottages was broken. The drain was made of common

unglazed pipes. The cesspool was open and uncovered, and it ought

to be covered and cemented. The drains were likely to render the

air of the cottages foul, and in his opinion they were in a state

injurious to health.

The defendant did not appear, and the Bench made an order for the

repair of the drains to he carried out within fourteen days.”

Bucks Herald 17th July 1875

In 1899, in the Akeman Street area of Tring, sewage leeching into

unsealed wells from which drinking water was drawn resulted in a

typhoid outbreak that infected 105 people, taking the lives of nine

of them.

――――♦――――

CHARLES

PERCY GREEN TOWNSEND

Under “Surgeons”, the Tring entry in the Hertfordshire Almanac

for 1884 lists “Messrs Pope and Townsend.” Reports of

coroners’ hearings identify Pope’s partner as Charles Townsend, who

qualified at Birmingham in 1875 and appears to have practiced

at Tring between 1881

and 1885, when his partnership with Pope was dissolved. Nothing else is known about him.

Townsend’s name appears in the press in connection with the suicide of Thomas Fowler, a labourer

aged 60 years, who lived at Buckland. His wife awoke during

the night to find that he had cut his throat. The newspaper report went on to

say that . . . .

“Mr. Charles Townsend, surgeon, Tring, said he had attended the deceased for

about six months. He was suffering from a very painful disease.

Witness was sent for early on the morning of the 3rd May, to see the

deceased, and found him with his throat cut. The wound was

deep, but no large artery was severed. The windpipe was

severed entirely. Witness sewed up the wound and dressed it,

and the deceased became convalescent so far as the actual wound was

concerned . . . . The jury returned a verdict to the effect that

‘The deceased died from exhaustion and shock to the system, caused

by the wound which he inflicted upon himself on the 3rd May, he

being at the time of unsound mind.’”

Bucks Herald 4th June, 1881

――――♦――――

RICHARD NICHOLSON LIPSCOMB M.R.C.S. Eng (1855) L.S.A. London (1856)

Most of the personal information available on Richard Lipscomb comes

from an obituary:

“Richard Nicholson Lipscomb was a son of Dr. Lipscomb of St. Albans,

and a grandson of the Rev. Dr. Nicholson, rector of its Abbey

Church. In 1857 he purchased the medical practice of Mr. Dewsbury.

He occupied as his house and surgery premises in the High-street,

since pulled down and now forming part of the Tring Park Estate

office, and here his three children were born. Mr. Lipscomb was

never very strong and usually drove in summer in a victoria and in

winter in his brougham,

[8] while his

professional rival, Mr. Pope, who, although older was much hardier,

either rode or drove in an open gig, and their courteous but

somewhat distant salutations as they met on their daily rounds had

an old-world flavour somewhat reminiscent of Anthony Trollop’s

Barsetshire. In the year 1883, being then not much over 50 years

old, Mr. Lipscomb retired from practice, and went to live at Hove,

where he has resided ever since. For the last few years he was more

or less of an invalid, and a fall down a steep flight of stairs was

the immediate cause of his death. Mrs. Lipcomb predeceased her

husband by some years, as did also his eldest son, but he leaves one

son and one daughter to mourn their loss.”

Bucks Herald, 3rd January, 1914

Lipscomb trained at Guys and the Middlesex Hospital, later becoming

House Surgeon, Acting Resident Medical Officer, and Medical and

Surgical Registrar before coming to Tring (c.1860).

In common with the town’s other medical practitioners,

Lipscomb was occasionally called upon to give evidence at coroner’s

inquests, such as in the case of

William Allen, a farm labourer, who died while gathering in the hay on a farm

at Drayton Beauchamp.

The hay was being loaded onto a cart to be

carried to the rickyard and Allen was standing on top of the pile.

Another labourer who was picking up the rakings heard the sound of

someone falling, and on going to investigate found Allen lying face

downwards

on the far side of the cart

with his arms under him . . .

.

“He was insensible and did not speak, nor did he call out as he

fell, or give any warning that he was likely to do so. He was quite

sober. He had complained once or twice during the day of feeling

unwell. It was very hot working in the fields. Witness did not

think he

[Allen]

lived two minutes after he found him on the ground. The horse was

standing perfectly still at the time. . . .

Mr. Lipscomb, surgeon of Tring, said he had frequently attended the

deceased for asthma, but not lately. He saw him yesterday; he was

then quite dead. There was a contusion on the fore-part of the

head, probably caused by a blow or fall. His skull was not

fractured. His impression was that there was a rupture of the

spinal chord at the back of the neck, which would most likely cause

immediate death. He could not detect any other injuries about the

body. He thought it very likely that the deceased might have taken

giddy, which caused him to fall off the load of hay. Asthma was

frequently connected with disease of the heart.

The jury returned a verdict of ‘Accidental death.’”

Bucks

Herald of 12th July, 1873

Smallpox was one of the biggest viral killers of the 19th century and

Lipscomb played his part in combating the disease with the vaccine

at his disposal.

In 1796, physician Edward Jenner discovered that people who had been

casually infected with cowpox appeared to become immune to smallpox.

However, cowpox was rare and before the commercial manufacture of

vaccine many years later the supply of vaccine depended on its

propagation from human to human – if the vaccine “took” on a child’s

arm, then nine or ten days later a pustule would form that was then

pricked to provide fresh vaccine. Children of the poor were

immunised at no charge and, on returning to clinics for “inspection”,

were put “arm-to-arm” with the next batch of children. But

at a time when the risk of transmitting infection such as syphilis was

little understood, arm-to-arm vaccination was dangerous.

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, anti-vaxxers – people

wholly opposed to vaccinations

– were again in the news, this time with regard to COVID-19

vaccination. But the anti-vaccination movement is not new; it is as

old as vaccines themselves. Widespread vaccination of children

began in the 1830s with the passing of the first Vaccination Act,

but the voluntary nature of the Act meant that take-up was poor. A

further Act in 1867 strengthened the legislation. Within seven days

of the birth of a child being registered, the registrar was to

deliver a notice of vaccination; if the child was not presented to

be vaccinated within three months, or brought for inspection

afterwards, the parents or guardians were liable to a summary

conviction and fine of 20 shillings.

Lipscomb’s role in the smallpox vaccination process resulted in the

anti-vaxxers of the day being brought before the magistrates:

James Putnam was next summoned, to show why in several cases he

refused to have his children vaccinated, and said he had a

remarkably fine healthy child vaccinated, and in eleven days she was

a corpse solely in consequence, the doctor certifying that she died

from ‘blood poisoning;’ and when he spoke to Mr. Lipscomb

about the vaccination of the others, he was told by that gentleman

that he would not be answerable that they would not be like the

child which died. He said he could not therefore submit to have his

children vaccinated. He had had twenty summonses in five years, and

had appeared there before them and stated his reasons. He had also

done what he could to get the law altered . . . The Chairman made

the order. Mr. Putnam said ‘it is of no use, I shall not have them

vaccinated.’”

Bucks Herald 20th

June, 1874

The public vaccinator

. . . . and this from the Bucks Herald 18th May, 1878:

“Hannah Baldwin and Elizabeth Norwood, of Tring, were charged by

Mr. Cook, vaccination-officer, at the instance of the Guardians,

with preventing a doctor taking lymph from a child that had been

vaccinated on the 17th ult. Each of them held an infant in her arms,

and were with difficulty made to assent to their having done any

wrong.—Mr. R. N. Lipscomb, surgeon, appeared in support of

the charge, and one of the mothers said he did eight children from

the arm of her infant, and she thought that was enough.—Dr. Lipscomb

said he was the best judge of that.—They were informed that they

were compelled by law to allow of lymph being taken from their

children, and the charge was dismissed.”

After many years of protest compulsory

vaccination was abolished in 1948.

Continuing the theme of smallpox, as part of the fight against this

and other serious infectious disease two hospitals were built near

Tring where patients could be treated in isolation from the rest of

the community, thereby greatly reducing the risk of contagion.

The Aldbury Infectious Diseases Hospital was opened in December

1879. Built by the Berkhamsted Sanitary Authority on an

isolated site in New Ground Road, the hospital was intended for

patients living within the area administered by the Berkhamsted Poor

Law Union, which included Tring. The hospital was managed by

the Sanitary Authority until 1898, when the Aldbury Hospital Joint

Committee ― made up from members of the Berkhamsted and Tring

councils ― took over. However, in 1900 the Tring Urban

District Council decided to build their own isolation hospital.

Lord Rothschild (Lord of the Manor of Tring) offered to donate

a 2½ acre site on Little Tring Road on which to build the hospital, while his wife Emma contributed

towards building and furnishing costs. Designed

by local architect William Huckvale, the Tring Isolation Hospital was opened by Lord Rothschild

on the 19th December 1901. Following the opening the management committees agreed in

principle that scarlet fever and diphtheria patients would be

treated at Tring, and small-pox patients at Aldbury.

――――♦――――

EDWIN JOSEPH LE QUESNE L.R.C.P.L., M.R.C.S.E.

Information on Edwin Le Quesne is sparse. He appears to have

been born at Jersey, Channel Islands,

on the 15th

November, 1851. On the 16th April, 1877, he was admitted

Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of London – it appears

that he was residing at the Metropolitan Free Hospital at the time.

On the 13th June, 1881, Le Quesne married Mary Ann Alice. A

notice appears in the Lancet, 9th December 1881, to the effect that

Le Quesne, “Edwin Joseph, L.R.C.P.Lond., M.R.C.S., L.S.A.Lond.,

has been appointed Medical Officer and Public Vaccinator for the

Tring District of the Great Berkhampstead Union, vice Lipscombe,

resigned.”

The Rothschild family acquired Tring Park in 1872, and from then

until his death in 1915, Nathaniel Rothschild, Lord of the Manor of

Tring, was a considerable benefactor to the town. Among other

municipal projects to which he contributed generously were the

construction of the Tring Isolation Hospital and the Tring municipal

cemetery. Lord Rothschild’s wife, Emma, was also a benefactor,

in particular financing the construction of

“Nightingale

House”, the

nursing home that once stood near the end of Station Road on a site

since sold by the N.H.S. for private development. Lady Emma

also contributed generously towards the nursing home’s running costs.

What facilities and services the Nursing Home provided are unclear.

In addition to a district nurse, there are odd clues in press

reports that it also provided services approaching those of a

cottage hospital. Writing in 1940, local historian Arthur

Macdonald Brown states in his book Some

Tring Air

that the nursing home was equipped “with a ward for accidents and

operations”.

Today road traffic accidents are not that uncommon, but even before the age of the motor vehicle

reports of accidents involving ridden horses and horse-drawn

vehicles appear in the press from time-to-time. Usually they

stemmed from panic-prone horses being startled and then bolting out of

control, such as in the following report.

Joseph

Hannell, a tailor from Hemel Hempstead, was one of a party that set

out to visit the Tring Museum riding in

a horse-drawn wagonette. On arrival the horse, a mare, was

stabled at the Castle in Park Road and her headgear taken off.

When the party left for home at 6-30, it appears the mare’s headgear

was not correctly fitted . . . .

“. . . .

They had only proceeded a few yards when a man in the road shouted

that the bit was out of the horse’s mouth. The man approached

the horse, and placing his hand on the straps running over the head,

behind the ears, pulled the bridle over the horse’s head . . . When

the bridle was off the mare started off at once, galloping.

Witness was powerless to stop her, and at the top of the street she

rushed up against the kerb, which caused the wagonette to be

overturned. He recollected nothing further until he found

himself in the Castle, where they were bathing his face. All

the party except Mr. Hannell sen. returned to Hemel Hempstead the

same night. . . . It was not more than twenty yards that the horse

galloped from the gates to the corner where the wagonette overturned

. . . .

. . . .

Mr. Joseph Hannell succumbed on Saturday morning to the injuries he

received in the accident in Park-road the previous Wednesday

evening. By Dr. Le Quesne’s advice he was removed to

the accident ward of the Tring Nursing Home, which, thanks in

a great measure to Lady Rothschild’s wise generosity, is held in

readiness for the reception of such cases. Upon examination it

was found that Mr. Hannell’s spine was broken, with the result that

he was paralysed from the waist downwards. All that medical

science and skilful nursing could accomplish was done to alleviate

the unfortunate man’s sufferings, but from the first it was known

that it was impossible to avert or even delay his death. The

doctor’s efforts were loyally supplemented by

Miss Girardet, the

indefatigable district nurse.”

Bucks Herald 29th September, 1900

An emergency ambulance service, skilled paramedics, accident &

emergency units staffed by specialist in that field, and

ultrasound/X-ray equipment for detecting and examining internal

injuries can now be brought to bear on serious accidents, but none of these facilities were available to Dr. Le Quesne.

The next fatality, which occurred in April 1900, was again caused by

a horse bolting. It happened while a field was being harrowed,

the harrow being drawn by a team of three horses that were being

led by a farm labourer, Shadrach Charles Payne aged 14. At the

inquest into his death it was established that:

“The leader was a young horse. The harrow was attached to the

two hind horses by a chain, which went between them, and the leader

was attached to that chain by two chains and hooks. They had

been at work about an hour and were turning at the end of the field

when one of the rear horses stepped on the leader’s chain.

This horse jumped forward, broke the middle chain, and ran away.

The deceased had hold of a chafe rein and held onto it with his

hand, being dragged ten yards and then falling to the ground.

The chafe rein is a short one, and the deceased was close to the

horse’s head. Deceased fell in front of the horse, which went

right over him.”

The lad being badly hurt was sent home and Dr. Le Quesne was called:

“Mr. Edwin Joseph Le Quesne said he was

a registered medical practitioner, of Tring. On April 12,

about 11a.m., witness visited the deceased, who was up.

Witness assisted to undress him and put him to bed. He

examined him, and found that he was recovering from a state of

collapse. His breathing was laboured and he complained of pain

on the right side. Witness examined his side, but could not

find any mark or bruise, or see that a rib was broken.

Deceased commenced coughing up blood, which suggested injury to the

lung. For a day or two deceased improved, but then he became

worse and his temperature increased. In witness’s opinion he

was suffering from a ruptured lung. Witness last saw him alive

on Thursday evening, but death took place on the following day.

Deceased told him that the horse kicked him, and he considered that

a kick from a horse would produce a rupture of the lung.—The jury

returned a verdict of ‘Accidental death’.”

Bucks Herald 28th April, 1900

Despite the apparent seriousness of the injury there appears to

have been no medical intervention other than observation. The

same applies to the next accident that also involved a bolting horse,

again with fatal consequences. The deceased was a man aged twenty-three.

At the hearing before the coroner the first witness stated that . . .

.

“. . . . on Thursday evening, about 7.15, I

was in the Western-road. I saw the deceased riding a mare in

the direction of Aylesbury. There was a trap coming from the

same direction. I could see that the mare was running away,

and the rider seemed to have lost all control over her. At the

time I saw the deceased he was falling from the mare, and was within

a few yards of me. He fell, his side coming in contact with a

lamp post, and his head striking the ground with great force.

His nose was badly cut by the fall. I went and picked him up,

but he was unable to stand. With assistance I took him to Dr.

Le Quesne‘s surgery. He was conscious, but did not say

anything as to why the mare bolted . . . .

“. . . . Dr. Le Quesne stated — On Thursday evening the

deceased was brought to my surgery, and I saw him on my return about

7.30. I examined him and found his nose broken, and there was

evidence of his having a tremendous blow on the right side, his ribs

being smashed, and there was a fearful contused wound on the right

hip, also internal haemorrhage. He brought up the contents of

his stomach, and from this it was evident that he had not been

drinking. I helped remove him and attended him until his death

at three o’clock on Friday. The cause of death was internal

haemorrhage, the result of injuries occasioned by the fall from the

horse. A verdict was returned accordingly.”

Bucks Herald

15th August, 1891

One forms the impression from this report that an internal

haemorrhage, while evident from the patient’s symptoms, was at the

time untreatable.

Not all Dr. Le Quesne’s appearances in the press involved fatalities.

This report is from the Bucks Herald, 26th November 1895.

“Dr. E. J. Le Quesne, of Tring, is delivering a course of ambulance

lessons to males in the Cheddington School-room on Thursday

evenings. Judging by the number of workmen who attend, at

least this form of technical instruction, promoted by Bucks. County

Council, is appreciated.”

Dr. Le Quesne lived

for at least part of his time in Tring at Elm House, the large property that stands in its own grounds at

the junction of Tring High Street and Langdon Street.

An auction advertisement for the sale of his furniture suggests that

Dr. Le Quesne left the town around 1910 and retired to Jersey. He died at “Melbury,” Havre des Pas, Jersey in his 68th year

on the 24th January 1919.

――――♦――――

JAMES BROWN M.B., C.M.Edin.

Judging by his qualifications – Bachelor of Medicine, Master of

Surgery (Chirurgiae Magistrum)

– James Brown was the first university educated medical

practitioner in Tring, his predecessors having progressed through

the earlier apprenticeship route. Brown came to Tring c.1884, first

as assistant to Mr. Pope, then as his partner. On Pope’s

retirement, Brown took over the practice. In addition to his

medical duties he was also a long-serving member of the Urban

District Council where his opinions and advice, especially upon

questions affecting the health and sanitation in the district, were

highly valued. Dr. Brown married Miss Fulton, a sister of the wife

of Richardson Carr, agent to Lord Rothschild, and they lived at the

large house called

“Harvieston” on Aylesbury Road.

Harvieston,

Dr. Brown’s residence.

In the age proceeding the motor car, local G.P.s travelled among

their rural patients on horseback or in a horse-drawn vehicle.

This meant that besides having to maintain a horse, a

groom-cum-coachman was also needed to ensure that the doctor’s

transport was available when he required it. In his memoir

Medicine in Tring, Dr. Thalon recalled that for many years a speaking tube ran from the

doctor’s house at No. 23 High Street to the groom’s room on the

other side of the road. This was used when the doctor was

called out at night and the groom had to get the horse and carriage

ready; and horses, being creatures prone to panic, sometimes bolted

causing a spill:

“ACCIDENT TO DR. BROWN.―We are sorry to record that Dr. Brown had an unfortunate spill

near Aldbury on Sunday morning when out on professional business.

The horse, frightened, it is thought, by some sheep, reared and

threw both Dr. Brown and his coachman out. The doctor was

severely shaken and bruised, but Bruce

[his coachman] unfortunately dislocated his collar-bone. We are pleased

to say the doctor is about again and Bruce is making satisfactory

progress.”

Bucks Herald 6th October, 1900

Returning to serious infectious disease, following an outbreak of

smallpox in 1902, accommodation at the Aldbury Isolation Hospital

came under pressure:

“HOSPITAL

ACCOMMODATION.―

In view of the fact that five smallpox patients were already in

Aldbury Hospital, which only contained eight beds, the Council

considered the question of providing additional accommodation if

necessary. A representative from Messrs. Humphries, Knightsbridge,

attended the meeting, and gave particulars as to the cost etc., of

erecting temporary iron buildings on the grounds of the Aldbury

Hospital, permission for which had been given by the Aldbury Joint

Committee. Two perfectly plain blocks, 40 feet by 20 feet,

would cost about £170, and a wood foundation would be about £10 extra.

These in the opinion of Dr. Brown would be quite suitable.

It was resolved ‘That the Hospital Committee be empowered to act in

dealing with the erection of temporary buildings and in other ways

with the smallpox outbreak.’”

Bucks Herald 29th March, 1902

Following the opening of the Tring Isolation Hospital in 1901,

permission for friends/families to visit patients

in isolation, especially children, became a bone of contention

with those administering the hospital – visiting

appears to have been an existing problem at the older Aldbury

hospital:

“THE

ISOLATION

HOSPITAL.–

On Saturday the scarlet fever patients in the Aldbury Hospital were

removed to the new isolation hospital belonging to the Tring Urban

District Council, and the Aldbury building was prepared for the

reception of some cases which were suspected to be smallpox.

On Sunday afternoon several persons who had been accustomed to go to

the Aldbury Hospital to see their children or friends through the

window presented themselves at the new hospital gate, but were

informed by the porter that the doctor had given orders that no one

was to be admitted without an order from him. Two or three of

the men started for Tring to get the necessary permit, but were told

by Dr. Brown that the Hospital Committee had decided that no

visitors were to be permitted within the hospital grounds.

Great dissatisfaction was expressed at this departure from the rule

which had so long obtained at Aldbury.”

Bucks Herald 18th January, 1902

“Dr.

Brown: To allow visiting does away with the whole idea of an

isolation hospital. At Aldbury we have a lot of trouble with

visitors, for if we do not watch the whole of the time they had the

windows open or were popping through the doors . . . . It was

eventually decided that words to the effect that parents would be

allowed to visit their children who were seriously ill should be

added to the rules.”

Bucks Herald 15th February, 1902

Besides his administrative work on hospital committees, Dr. Brown also

encountered serious disease in his everyday role as a medical

practitioner:

“A CASE

OF

SMALLPOX.–

On Tuesday a case of smallpox was notified in Tring. A young

man named George Norwood, living at 26, Albert Street, but working

with a gang on the railway cutting near Haddenham in the adjoining

county of Bucks, returned to his home on Monday ill. On

Tuesday morning he was seen by Dr. Brown, who thought his

symptoms pointed to smallpox. The doctor at once communicated

with the Medical Officer for the district, Dr. W. Gruggen

[of

whom more later], by whose

direction Norwood was the same evening conveyed to the Isolation

Hospital at Aldbury. The two other occupants of the house in

Albert Street were put in quarantine, and everything was done to

prevent the spread of the disease. As the patient had not been

in contact with anyone outside his home, there was every reason to

hope that, thanks to the prompt action of Dr. Brown and the

Medical Officer, the infection will not spread.”

Bucks Herald 21st March,

1903

In the

next case the coroner for the district held an inquiry into the

death of Tom Briant, a Tring postman aged 56 who was hard of

hearing. This is an early road traffic accident in the town involving a

motor vehicle, and one that would probably be viewed more critically

by today’s traffic police than by the town’s police force of 1912.

When interviewed by the police the car’s driver, an Aylesbury

dentist, said he saw Briant in the road gathering manure into a

bucket. When asked why he did not stop the driver replied that

having sounded his horn he thought the man was going to move out of

the way, but not having heard the horn Briant stepped into the path

of the car. He was then struck by the car’s nearside wing and,

despite one witness claiming the car was travelling at no more than

10 m.p.h., the vehicle pushed Briant along the road for 12 yards

before stopping:

“. . . . P.C.

Endersby, stationed at Tring said he received information of the

accident about 11.40 on the morning of March 7th. He went at

once, and found deceased lying in the road, and the car on the

right-hand side of the road about 8 inches from the path. The

road was about 16 feet wide at this point. Witness assisted

the doctor to move deceased, who seemed dazed. He said he

never saw or heard the car till he was knocked down, when he

clutched the front of the car. Deceased was apparently pushed

along about 12 yards by the car.

By Mr.

Wilkins

[witness]

― He could see where the dust had been pushed up by the deceased

being shoved along . . . .

. . . . Dr. Brown said he received a telegram about 12.25 at

Aldbury, and got to Mr. Briant’s house about one o’clock. He

found deceased had a fracture of the left thigh, about the middle of

the lower third; and also slight bruises on the right hip and

thigh. It was rather a troublesome fracture to set, and

chloroform had to be administered. Dr. O’Keeffe

assisted to set the leg. There was very little trouble with

the leg after it was set. Witness had attended deceased for 27

years. He had weak heart muscles. Between the 7th and

the 20th there were no drawbacks, except the discomfort of changing

the splints. On the morning of the 20th deceased was very

well. He said he had not been better for years. About 10

the some night witness was fetched, but found deceased dead when he

got there. From the description of the symptoms he got from

the daughter, he should say death was caused by a clot of blood in

the pulmonary artery. This was not an uncommon thing to happen

after an injury or an accident.”

Bucks Herald 30th March, 1912

The jury

returned a verdict that death was due to a blood clot in the

pulmonary artery, the result of being laid up with injuries

sustained in the occurrence which was purely accidental.

James Brown died on the 15th December 1914 at his home “Harvieston”

on the Aylesbury Road.

He had lived Tring

for some twenty-five years, during which time “his assiduous attention to his

professional duties, and his courteous bearing to all, made him

popular with all classes. His work as a doctor naturally

brought him much into contact with his poorer neighbours, and his

kindness and sympathetic consideration for the humblest of them won

for him their lasting esteem.” He left a widow and three

children, two daughters and a son,

Andrew,

who

was killed in action on the 2nd July 1916 while serving as a second

lieutenant in the South Staffordshire Regiment.

――――♦――――

WILLIAM WARD ANDERSON M.B., B.Ch. Edin.

Dr. Anderson qualified at Edinburgh University

in July 1904

with the degrees of Batchelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery

(Ch = Chirurgie, Latin for surgery). The 1908 edition of

Kelly’s Directory for Tring lists him in partnership with Dr. Le

Quesne, their practice being in Western Road (possibly Le Quesne’s

residence at Elm House).